Abstract

Patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors or antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitors may develop resistance driven by gut dysbiosis, which disrupts the MAdCAM-1–α4β7 axis and promotes the recruitment of immunosuppressive IL-17-producing T regulatory (Tr17) cells into tumors. We evaluated soluble MAdCAM-1 (sMAdCAM-1) as a prognostic biomarker in 1,051 patients from three cohorts: JAVELIN Renal 101 (avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib), SURF (sunitinib) and NIVOREN (nivolumab after tyrosine kinase inhibitors). In the JAVELIN cohort, baseline sMAdCAM-1 levels >180 ng ml−1 were associated with significantly improved progression-free survival (13.9 versus 8.4 months, P < 0.01) and overall survival (18 months: 84.2% versus 68.1%, P < 0.01), independent of IMDC risk groups. We validated the prognostic value of sMAdCAM-1 for overall survival in the SURF and NIVOREN cohorts. Notably, low sMAdCAM-1 levels were associated with an immunosuppressive gut microbiota profile dominated by Enterocloster species. Therefore, sMAdCAM-1 deserves further investigations as a biomarker-guided tool for microbiota-targeted interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

While cancer immunotherapy revolutionized the clinical management of patients with cancer, resistance remains a major challenge1. The study of biomarkers offers a pathway to decipher immunotherapy resistance, tailoring treatment to each patient’s unique profile and tumor biology2. Over the past decade, gut microbiota has emerged as a key modulator of the efficacy of immunotherapy3,4,5 and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)6,7 across cancer types. Studies heralded the deleterious effects of broad-spectrum antibiotics taken around the first administration of the immunostimulatory immune checkpoint inhibitors anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies on response rates and survival of patients across various cancer types and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) regimens (alone or combined with chemotherapy or TKI)4,8. Several factors, including certain comedications (such as antimicrobials), chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer itself, may cause a deviation of the microbial repertoire from healthy intestinal commensalism, a phenomenon known as gut dysbiosis9,10. Notably, prior exposure to TKIs before initiating nivolumab has also been shown to alter the gut microbiota composition, potentially affecting subsequent immunotherapy efficacy11. Gut dysbiosis has been linked to altered gut and blood metabolomes, systemic inflammation and circulating CD8+ T cell exhaustion12.

Causal links between gut dysbiosis and resistance to cancer immunotherapy have been demonstrated in preclinical models and proof-of-concept clinical trials. Interventions aimed at restoring a favorable microbiota, such as fecal microbial transplantation from patients who benefited from ICI or from healthy volunteers, in individuals with metastatic melanoma13,14,15,16, lung cancer17 and renal cell carcinoma (RCC)11,18,19, or oral administration of the probiotic Clostridium butyricum strain CBM 588 in patients with metastatic RCC (mRCC)7,20,21 have yielded encouraging results. These findings have spurred efforts to refine the diagnosis of gut dysbiosis, with the prospect of identifying participants who need to restore intestinal integrity to enhance responses to ICI.

The most comprehensive methodology to assess baseline gut dysbiosis relies on metagenomic shotgun sequencing (MGS) of fecal material11,22. Large MGS datasets have enabled the development of microbiota-based biomarkers based on machine learning23 or custom scoring based on quantitative polymerase chain reaction24. Unmasking mechanisms by which antibiotics mediate their immunosuppressive effects has led to the discovery of a circulating biomarker, sMAdCAM-1, linked to a specific compositional shift of the intestinal microbiota and clinical outcomes in patients with lung cancer and genitourinary cancers25. Indeed, the relative overdominance of the genus Enterocloster induces the downregulation of MAdCAM-1 in high endothelial venules of the ileal lamina propria and mesenteric lymph nodes, leading to migration and tumor homing of enterotropic interleukin-17 (IL-17)-producing immunosuppressive T cells, which express the α4β7 heterodimeric MAdCAM-1 receptor25. Notably, MAdCAM-1 is shed into the blood with sMAdCAM-1 levels reflecting the ileal expression of MAdCAM-1 (ref. 25). Remarkably, low sMAdCAM-1 levels were associated with poorer prognosis in three independent cohorts of patients with cancer treated with ICI-based regimens after first line of therapy25.

In the current work, we asked whether sMAdCAM-1 levels could serve as a biomarker of an immunosuppressive microbiota linked to resistance to ICI and/or TKI regimens, specifically in patients with mRCC. We investigated the distribution and biological significance of baseline and on-treatment sMAdCAM-1 levels in the following three independent cohorts of patients with mRCC: the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial (NCT02684006)26,27, the SURF trial (NCT02689167)28 and the GETUG-AFU26-NIVOREN trial (NCT03013335)29.

Results

Distribution of sMAdCAM-1 in individuals with mRCC compared with controls

We measured sMAdCAM-1 levels using a Luminex assay in two independent cohorts of healthy volunteers. The first was the Weill Cornell Medicine Employees (WELCOME) cohort, comprising 75 healthcare workers from Weill Cornell Medicine in the USA (median age = 42 years, range = 26–75; predominantly female (76%))30. The second was the Belgian Flemish study on Environment, Genes and Health Outcomes (FLEMENGHO) cohort, including 49 healthy individuals (median age = 63 years, range = 59–66; predominantly male (56%))31. The training cohort consisted of patients included in the phase 3 randomized JAVELIN Renal 101 trial (NCT02684006) with available plasma samples (68% of the intent-to-treat population). Overall, patients were mostly male (74%), with a median age of 61 (27–85) years and of intermediate International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) risk (62%; Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1a). All patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG 0–1) and clear-cell histology. The median follow-up was 18.9 months. The validation cohorts comprised the following two prospective phase 2 trials: SURF (NCT02689167), a prospective trial that evaluated two different sunitinib schedule modifications in patients with mRCC experiencing sunitinib-related toxicity; NIVOREN (NCT03013335), a prospective real-world setting study of nivolumab after antiangiogenic TKI. In the NIVOREN cohort, patients were mostly male (80%), with a median age of 65 years (range = 22–87) and ECOG 0–1 (86%). In the SURF cohort, patients were mostly male (80%), with a median age of 64 years (range = 29–84) and ECOG 0–1 (96%).

The median sMAdCAM-1 concentrations were 196 and 178 ng ml−1 in the WELCOME and FLEMENGHO cohorts, respectively, with no significant difference between the two (P = 0.3173; Fig. 1a). The median value of sMAdCAM-1 was 187 ng ml−1 for all healthy volunteers (both WELCOME and FLEMENGHO cohorts merged). In patients with mRCC enrolled in the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial (Extended Data Fig. 1a), the median values of sMAdCAM-1 at baseline were 234 and 238 ng ml−1 for the avelumab + axitinib and for the sunitinib arms, respectively (Fig. 1b). In patients with mRCC enrolled in the SURF and NIVOREN trials (Extended Data Fig. 1b,c), the median values of sMAdCAM-1 were 169 and 139 ng ml−1, respectively (Fig. 1c). Patients with refractory mRCC had lower sMAdCAM-1 levels at baseline compared with patients treated in the first-line setting and healthy volunteers (Fig. 1d). Additionally, we observed increased proportions of patients presenting low sMAdCAM-1 levels (<180 ng ml−1) in the poor IMDC risk factor group compared with patients in the favorable or intermediate IMDC risk groups (Fig. 1e; P = 0.0003 for avelumab + axitinib arm and P < 0.0001 for sunitinib arm). In line with this finding, sMAdCAM-1 levels also correlated with the main circulating inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and IL-8 (P < 0.001 and P = 0.010, respectively; Fig. 1f,g). A weak correlation between age and baseline sMAdCAM-1 levels was also observed (Spearman’s ρ = 0.15, P = 0.09) in the training cohort, while no correlation was observed in the NIVOREN (Spearman’s ρ = −0.06867 and P = 0.2538) or SURF (Spearman’s ρ = 0.00144, P = 0.9847) validation cohorts, using single-agent nivolumab and single-agent sunitinib, respectively. Moreover, sMAdCAM-1 and the estimated glomerular filtration rates were positively and very weakly correlated (Spearman’s ρ = 0.16, P = 0.03).

a–c, Violin plots with overlaid boxplots showing the distribution of sMAdCAM-1 concentrations across cohorts of healthy volunteers (HVs) from the USA (n = 75) and Belgium (n = 49; a), in the training cohort of patients treated with first-line sunitinib (n = 284) or first-line axitinib plus avelumab (n = 319; b) and in the validation cohorts of patients treated with first-line sunitinib (n = 170) or second-line or later-line nivolumab (n = 278; c). The box bounds are the Q1, median and Q3; the whiskers show Q1 − 1.5× the interquartile range (IQR) and Q3 + 1.5× the IQR. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test without adjustments for multiple comparisons; exact P values are shown. d, Violin plots with overlaid boxplots showing the distribution of sMAdCAM-1 concentrations across healthy volunteers (n = 124) and patients treated with first-line (1L) or second-line (2L) therapies (n = 1,051). The box bounds are the Q1, median, and Q3; the whiskers show Q1 − 1.5× the IQR and Q3 + 1.5× the IQR. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test without adjustments for multiple comparisons; exact P values are shown. e, Bar plots show the number and percentage (in parentheses) of individuals with low sMAdCAM-1 concentrations (≤180 ng ml−1) by IMDC risk group in the training cohort. f,g, Scatterplots showing the relationship between MAdCAM-1 concentrations and IL-6 (f) and IL-8 (g) in plasma samples. Each point represents an individual sample measurement. The solid line represents the linear regression fit, with the shaded area representing the 95% CI of the fitted regression line. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using a two-sided Spearman test without adjustments for multiple comparisons; exact P values are shown.

These findings suggest that lower sMAdCAM-1 levels may be associated with advanced mRCC and dismal prognosis.

Low levels of sMAdCAM-1 are associated with reduced survival in the training cohort

The optimal cut-off was 180 ng ml−1 (25% percentile) based on the overall survival (OS) outcome in the whole population. Restricted cubic spline and residual plots further confirmed a nonlinear relationship of sMAdCAM-1 levels with OS (Extended Data Fig. 2). Notably, the population included in the sMAdCAM-1 analysis was comparable to the intent-to-treat population in terms of survival outcomes (Extended Data Fig. 3a).

Overall, patients who had higher sMAdCAM-1 levels (>180 ng ml−1) experienced improved progression-free survival (PFS; median = 13.9 (11.3, 16.6) versus 8.4 (6.0, 9.9) months, P < 0.01) and OS (median = not reached (NR) (30.0, NR) versus 24.6 (22.2, NR) months; 18-month OS rates were 84.2% (80.2%, 87.4%) versus 68.1% (59.2%, 76.5%), P < 0.01; Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). These associations remained significant after adjusting for IMDC risk groups (Extended Data Table 1). The survival advantage of high sMAdCAM-1 levels was independent of study arm—median PFS was 18.0 (13.4, 21.0) versus 8.7 (6.0, 13.8) months and 18-month OS rates were 85.2% (79.6%, 89.3%) versus 75.6% (64.0%, 84.0%) for the avelumab + axitinib arm (Fig. 2a,b); median PFS was 11.1 (8.6, 13.9) versus 6.9 (5.6, 11.1) months and 18-month OS rates were 83.2% (77.1%, 87.8%) versus 58.6% (44.3%, 70.5%) for the sunitinib arm (Fig. 2c,d; Pinteraction = 0.798 and 0.370 for PFS and OS, respectively). The prognostic model incorporating IMDC + sMAdCAM-1 demonstrated a significant improvement in the area under the curve (AUC) at 18 months compared to the IMDC model alone (0.72 versus 0.68; P = 0.01; Extended Data Table 1).

a–d, Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of PFS (a,c) and OS (b,d) in patients treated with avelumab plus axitinib (a,b) or with sunitinib (c,d), stratified by sMAdCAM-1 concentrations in the training cohort. Patients were dichotomized using a threshold of 180 ng ml−1 into low (≤180 ng ml−1) and high (>180 ng ml−1) sMAdCAM-1 groups. Survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test; P values are shown. Risk tables indicate the number of patients at risk at each time point.

a,b, Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of OS stratified by sMAdCAM-1 concentrations in the SURF (a) and NIVOREN (b) validation cohorts. Patients were dichotomized using a threshold of 180 ng ml−1 into low (≤180 ng ml−1) and high (>180 ng ml−1) sMAdCAM-1 groups. Survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test; P values are shown. Risk tables indicate the number of patients at risk at each time point.

We conclude that sMAdCAM-1 <180 ng ml−1 is a negative prognostic biomarker in patients with mRCC treated with first-line therapy, irrespective of the systemic treatment.

Low levels of sMAdCAM-1 are associated with reduced OS in the validation cohorts

The percentage of patients with mRCC presenting with sMAdCAM-1 <180 ng ml−1 was 59% and 76% in the validation SURF and NIVOREN cohorts, respectively. The SURF cohort included two patients with nonclear cell histology, both of whom were in the low sMAdCAM-1 group. The low sMAdCAM-1 group had a higher proportion of patients with ECOG >2 (P = 0.04) and a poor-risk IMDC group (P < 0.01). In the NIVOREN cohort, these patients also had more bone metastatic sites at study inclusion (P = 0.002). The median follow-up was 34 (1.0, 70.0) and 21.8 (20.2, 22.7) months in the SURF and NIVOREN cohorts, respectively. Patients with higher sMAdCAM-1 levels had a numerical OS advantage—NR (1.0, 59.0) versus 50 (2.0, 70.0) months (P = 0.0565, log rank) in the SURF cohort and NR (23.7, NR) versus 18.8 (14.6, 24.1) months (P = 0.0004, log rank) in the NIVOREN cohort (Fig. 3a,b). However, sMAdCAM-1 levels did not significantly impact PFS in either cohort (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b).

The multivariable Cox regression analysis in the NIVOREN cohort (n = 263) revealed that low baseline sMAdCAM-1 levels (<180) were independently associated with worse OS in nivolumab-treated patients, demonstrating a significant hazard ratio (HR) of 2.11 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.27–3.49; Extended Data Table 2). Hence, patients with sMAdCAM-1 below this threshold doubled their risk of death compared to those with higher levels, even after adjusting for other relevant clinical variables such as antibiotic intake or IMDC. Interestingly, while prior antibiotic use showed a nonsignificant trend toward poorer outcomes (HR = 1.44; 95% CI = 0.90–2.31), it did not reach statistical significance in this model. Furthermore, the interaction analysis between sMAdCAM-1 and antibiotic use was nonsignificant (P = 0.1005), indicating that the prognostic value of sMAdCAM-1 was consistent regardless of patients’ antibiotic exposure history. The potential links between toxicity events and sMAdCAM-1 could not be studied, either due to data unavailability (JAVELIN Renal 101) or low frequencies (SURF, NIVOREN).

Hence, we validated the sMAdCAM-1 (using the 180 ng ml−1 cut-off value defined in the training cohort) as a prognostic biomarker for OS in patients with mRCC receiving first-line or subsequent therapy, across both ICI and TKI monotherapy regimens.

Immunotherapy increases sMAdCAM-1 levels

We next analyzed longitudinally the evolution of sMAdCAM-1 as a dynamic biomarker while on TKI alone (sunitinib arm) or TKI combined with ICI (avelumab plus axitinib arm) in the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial and during ICI alone (nivolumab) in the NIVOREN trial. After 12 weeks of therapy (C3 visit), the circulating levels of sMAdCAM-1 decreased from a median of 234 down to 213 ng ml−1 in the sunitinib arm (Fig. 4a, left; P = 0.0021), while they increased from 238 to 270 ng ml−1 in the avelumab plus axitinib arm (Fig. 4a, right; P < 0.0001). The latter finding was corroborated in the NIVOREN validation cohort after 24 weeks of therapy (C7 visit; Fig. 4b; P < 0.001). We also noted that sMAdCAM-1 levels decrease at progression (Fig. 4b; P = 0.035).

a, Paired dot plots showing plasma MAdCAM-1 concentrations at baseline (C1) and on therapy (C3) for individual patients in each treatment arm (sunitinib, n = 284; avelumab + axitinib, n = 319). Filled circles are colored by treatment arm. Data were analyzed using a two-sided paired t-test; P values are indicated. b, Boxplots showing the longitudinal distribution of sMAdCAM-1 concentrations in the NIVOREN at C1 (n = 278), C3 (n = 80), C7 (n = 27) and disease progression (PD; n = 23). The box bounds are the Q1, median and Q3; the whiskers show Q1 − 1.5× the IQR and Q3 + 1.5× the IQR. ‘X’ represents the mean, and the small ‘x’ denotes extreme values. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. P values are shown. c, Horizontal bar plot showing the distribution of patients across four longitudinal sMAdCAM-1 categories, defined by dichotomized values at baseline (C1) and on-treatment (C3) using a threshold of 180 ng ml−1: low–low, low–high, high–low and high–high. Categories reflect changes in sMAdCAM-1 status over time. Bars represent the proportion of patients in each category relative to the total patients in each arm. d,e, Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of PFS (d) and OS (e) across four longitudinal sMAdCAM-1 categories, defined by dichotomized values at baseline (C1) and on-treatment (C3) using a threshold of 180 ng ml−1—low–low, low–high, high–low and high–high. Categories reflect changes in sMAdCAM-1 status over time. Risk tables indicate the number of patients at risk at each time point.

Furthermore, we observed different sMAdCAM-1 dynamics in the two arms of the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial (P < 0.001; Fig. 4c). sMAdCAM-1 levels remained below our defined threshold after the first two cycles of treatment (C1 ≤ 180 and C3 ≤ 180) in 17.6% of patients in the sunitinib arm compared to 7.5% of those treated with the ICI-based combination (low–low; Fig. 4c). Indeed, up to 16.9% of patients with mRCC treated with avelumab + axitinib normalized their sMAdCAM-1 levels after initiation of therapy (C1 ≤ 180 and C3 > 180), versus 4.9% in the sunitinib arm (low–high; Fig. 4c). Moreover, 14.4% of the patients treated in the sunitinib arm experienced a decrease in their sMAdCAM-1 versus 5.3% in the avelumab + axitinib arm (high–low; Fig. 4c). The persistent low sMAdCAM-1 level translated into worse survival in the Javelin Renal 101 trial regardless of treatment arm, for both PFS and OS (Fig. 4d,e and Extended Data Table 3; Pinteraction = 0.88 and 0.16 for PFS and OS, respectively).

We conclude that low sMAdCAM-1 at baseline and after two cycles of therapy are negative prognostic biomarkers in patients with mRCC regardless of treatment regimen.

The gut microbiota composition is dynamically influenced by cancer therapies

To investigate potential links between low sMAdCAM-1 levels and gut dysbiosis, we performed MGS of stool samples from individuals living with RCC in the prospective ONCOBIOTICS study at baseline and following TKI or ICI therapies.

In 37 TKI-treated patients, we observed a trend toward reduced microbial diversity (richness and species abundances), reflected in decreased Shannon index values post-treatment (Fig. 5a; P = 0.08). TKI therapy induced relative overgrowth of immunosuppressive Enterocloster species (Enterocloster aldensis, Enterocloster citroniae and Enterocloster bolteae), prototypical of gut dysbiosis caused by antibiotics9,11, cancer progression24,32 or ileal MAdCAM-1 downregulation25. This shift coincided with depletion of immunogenic taxa, including Lachnospiraceae family members (Dorea longicatena), Candidatus Cibiobacter qucibialis24, Oscillospiraceae (Faecalibacterium prausnitzii33 and Ruminococcaceae unclass.) family members associated with favorable immunogenic properties24,32,34, Bifidobacterium longum and B. adolescentis associated with response to immunotherapy35 or Christensenellaceae bacterium NSJ64 associated with the abscopal effects of radiotherapy36 (Fig. 5a,b). Conversely, ICI-treated patients (n = 78) showed progressive loss of E. citroniae, Clostridium leptum and Ruminococcus torques in responders9,11 (Fig. 5c, top), whereas nonresponders lost immunogenic commensals (Lachnospiraceae bacterium and F. prausnitzii; Fig. 5c, bottom).

a, Alpha diversity as determined by the Shannon index assessed at baseline and after administration of TKIs alone in n = 37 patients with advanced RCC. Boxplots represent the within-category microbial richness distribution summarized by the first and third quartiles as hinges of the box, the median and whiskers extending for the largest or smallest value not exceeding 1.5× IQR from the two ends of the box, with data beyond these values plotted individually as outliers. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test without adjustments for multiple comparisons. b,c, Longitudinal analysis of microbial features in stool samples via MGS. b, Paired comparison of baseline versus post-TKI stool samples from the same patients (n = 37). c, Paired comparison of pre- and post-ICI samples in responders (top; n = 17) and nonresponders (bottom; n = 61). Response was defined as complete or partial response lasting >12 months with OS >24 months (responders) or progressive disease as best response (nonresponders). Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test (features required in ≥10 samples per group). Displayed features are filtered for >50% prevalence in both groups and a raw P < 0.05. No associations remained significant after Benjamini–Hochberg correction (false discovery rate (FDR )< 0.2). d, Alpha diversity as determined by the richness (left) and Shannon index (right) in patients with advanced NSCLC (n = 176) stratified by sMAdCAM-1 levels—low sMAdCAM-1 versus high sMAdCAM-1. Boxplots represent the within-category microbial richness distribution summarized by the first and third quartiles as hinges of the box, the median and whiskers extending for the largest or smallest value not exceeding 1.5× IQR from the two ends of the box, with data beyond these values plotted individually as outliers. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test without adjustments for multiple comparisons. e, LDA effect size graph was generated using paired sMAdCAM-1 and MGS data in patients with advanced NSCLC (n = 176) stratified by sMAdCAM-1 levels—low sMAdCAM-1 and high sMAdCAM-1. See Extended Data Table 4. f, Volcano-plot based on MGS showing differences (P < 0.05, two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test without adjustments for multiple comparisons) between ≥9 SIG1 counts and <9 SIG1 counts groups (n = 285 patients with NSCLC, RCC and bladder cancer). g, Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of OS stratified by SIG1 counts in patients with advanced RCC (top). Patients were dichotomized using a threshold ≥9 SIG1 counts (n = 69, solid line) and <9 SIG1 counts (n = 105, dotted line) groups. Survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test without adjustments for multiple comparisons; exact P values are shown. Scatterplots showing the relationship between sMAdCAM-1 concentrations in plasma samples and SIG1 counts in paired stool samples (n = 499; bottom). Each point represents an individual sample measurement. The solid line represents the linear regression fit, with the dotted lines representing the 95% CI of the fitted regression line. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using a two-sided Spearman test without adjustments for multiple comparisons; exact P values are shown.

Building upon prior findings in 72 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)25, we confirmed that low sMAdCAM-1 correlates with reduced microbial diversity (richness, P = 0.04; Shannon index, P = 0.05; Fig. 5d) in a larger cohort of 188 patients with NSCLC. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size analysis further highlighted tolerogenic Enterocloster spp.9,25 enrichment in patients with low sMAdCAM-1 (Fig. 5e; Enterocloster SGB14313, P = 0.005; Extended Data Table 4). To validate the Enterocloster genus as a cancer-associated dysbiosis marker, we analyzed the ONCOBIOME meta-cohort32,37 (n = 457 patients with NSCLC, RCC, bladder32, colorectal32,38 and hematological malignancies39) with MGS in stool samples paired with sMAdCAM-1 in the plasma samples. Using a previously defined ratio (S score) between species-interacting groups (‘SIG’; 37 SIG1 taxa linked to poor outcome (OS < 12 months); 45 SIG2 taxa associated with OS >12 months))24, we found that distinct Enterocloster species best discriminated ≥9 SIG1 counts from <9 SIG1 counts individuals (Fig. 5f). In the mRCC cohort (n = 174), patients with high SIG1 commensals counts (≥9, threshold defined as the median SIG1 count in the ONCOBIOME metacohort) showed worse OS than those with low SIG1 counts (n = 174; Fig. 5g, top; P = 0.030). In fact, we observed a weak but significant inverse correlation between sMAdCAM-1 and SIG1 abundance (Fig. 5g, bottom; P = 0.02). Consistently, sMAdCAM-1 inversely correlated with Enterocloster SGB14313 abundance across cohorts (n = 55 patients with mRCC, ρ = −0.28, P = 0.052; n = 61 patients with bladder cancer, ρ = −0.21, P = 0.099; n = 188 patients with NSCLC, ρ = −0.15, P = 0.049; Extended Data Fig. 5a–c).

In summary, these findings suggest that sMAdCAM-1 may serve as a surrogate marker for distinct gut microbial profiles relevant to ICI response, particularly reflecting the immunosuppressive Enterocloster genus dominance. Further investigation of its utility for guiding microbiota-modulating therapies is warranted.

Discussion

Functional biomarkers to guide meaningful changes in the clinical management of patients with mRCC are needed to predict and or circumvent resistance to current ICI-based therapeutic regimens. Here we show that a gut immune checkpoint, the MAdCAM-1, known to regulate the gut homing and exodus of immune cells to the tumor microenvironment, may inform an individualized approach to therapy. In the large multicenter randomized JAVELIN Renal 101 trial of 603 patients with mRCC and available biomarker data, as well as in two additional prospective phase 2 validation cohorts (NIVOREN, n = 278; and SURF, n = 170), baseline sMAdCAM-1 levels below 180 ng ml−1 were associated with reduced OS. Interestingly, the optimal cut-off defined in the training cohort was comparable to the median values in the two healthy volunteer cohorts. Moreover, persistence of sMAdCAM-1 levels below 180 ng ml−1 after two treatment cycles was associated with poor prognosis. In a multivariable analysis comprising antibiotic uptake, sMAdCAM-1 remained an independent prognostic biomarker for ICI treatment, beyond the IMDC risk score. This finding corroborates previous reports linking sMAdCAM-1 levels below each cohort’s median values with reduced OS in patients with lung, RCC and urothelial cancer treated after first-line therapy25.

MAdCAM-1 is constitutively expressed in high endothelial venules of the lamina propria, mesenteric lymph nodes and Peyer patches (as well as in the hepatic endothelium of inflamed livers)40, can be upregulated during inflammation and shed into the plasma in conditions that remain unclear. Loss of the MAdCAM-1 protein parallels the loss of FOXP3 regulatory T (Treg) cells and IL-17-producing RORγt CD4+ T cells in the lamina propria25. In experimental models, we showed a cause-and-effect relationship between high expression (and shedding) of MAdCAM-1 in the liver and the interception of the migration of enterotropic Treg cells to tumor lesions25. Other reports highlighted the relevance of the MAdCAM-1–α4β7 tropism during chronic inflammatory processes within or outside the intestines41,42,43. Ileal endothelial MAdCAM-1 is downregulated during gut dysbiosis following broad-spectrum antibiotics or tumor progression in mice and patients25. However, fecal microbial transplantation using a healthy microbiota or specific commensal strains can restore MAdCAM-1 expression on the surface of ileal endothelial cells. Indeed, Akkermansia species (in particular Akkermansia massiliensis SGB9228) markedly upregulated MAdCAM-1 expression levels after an oral gavage performed postantibiotic therapy25. Moreover, our group recently showed that the combination of low sMAdCAM-1 levels and the absence of fecal Akkermansia species identified a subgroup of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer resistant to immunochemotherapy32. Notably, here we show that TKI therapy was associated with an overgrowth in the population of immunosuppressive genus Enterocloster, a finding also seen in individuals who do not respond to ICI24,44,45 or are diagnosed with chronic inflammatory disorders10,46. These findings suggest that patients with mRCC and low sMAdCAM-1 levels may benefit from microbiota-centered interventions. In certain RCC cohorts, this can represent up to 76% of patients. Two pioneering randomized studies7,20,47 provided the proof-of-concept that a Japanese probiotic Clostridium butyricum MIYAIRI 588 (CBM588) can enhance the efficacy of ICIs or TKI + ICI combinations. The first clinical study randomizing TKI + ICI with or without FMT met its primary endpoint to improve PFS in patients with IMDC intermediate or poor when transferring an exogenous microbiota from a patient with mRCC and achieved durable benefit on ICI among treatment-naive patients18. A phase 1 clinical trial (NCT05865730) is currently underway, evaluating the impact of daily administration of Oncobax AK—a capsule containing live A. massiliensis (strain p2261, SGB9228), which shares overlapping health-related functions with Akkermansia muciniphila—in patients with mRCC who are Akkermansia-deficient at the initiation of the first-line therapy48.

This study has several limitations. First, conclusions are derived from clinical trials with strict eligibility criteria, potentially limiting generalizability to real-world populations. Second, we could not account for comorbidities that may influence microbiome composition, including inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), prior bowel resections or use of over-the-counter probiotics. Third, while adding sMAdCAM-1 to prognostic models significantly improved survival prediction (AUC = 0.72 versus 0.68), its absolute incremental value remains modest. Although mechanistically linked to IMDC and IL-6 pathways, the biomarker’s clinical utility may be greatest within microbiota-directed therapeutic strategies rather than as a standalone prognostic tool. Finally, the cohorts included therapies that have become less relevant to contemporary management of patients with mRCC (avelumab, nivolumab monotherapy), further limiting their current clinical applicability.

Altogether, these findings support a paradigm shift in the management of mRCC, highlighting the need for biomarker-guided clinical trials investigating microbiota-targeted interventions aimed at enhancing the efficacy of standard ICI-based therapies.

Methods

Study participant details

Participant data were obtained from the following four prospective clinical trials in RCC: JAVELIN Renal 101 (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT02684006), GETUG-AFU26 NIVOREN (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT03013335), SURF (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT02689167) and ONCOBIOTICS (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04567446).

Clinical trials

JAVELIN Renal 101 is a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 3 clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib monotherapy in patients with previously untreated advanced RCC with a clear-cell component. A total of 886 adults were enrolled and randomized 1:1 to receive either avelumab (10 mg kg−1 intravenously every 2 weeks) plus axitinib (5 mg orally twice daily) or sunitinib (50 mg orally once daily for 4 weeks in a 6-week cycle). For alignment within the study, a single cycle consisted of 6 weeks for both treatment arms. The trial design has been previously described, and results are reported per CONSORT guidelines26,49. The coprimary endpoints were PFS and OS in patients with PD-L1–positive tumors27,49. A key secondary endpoint was PFS in the overall population; other endpoints included objective response rate (ORR). Efficacy data reported here reflect the second interim analysis of the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial, with a data cut-off of January 2019. Blood samples were collected at screening and on multiple days within cycles 1, 2 and 3, before treatment. Available baseline and cycle 3 samples were used in this analysis. The collection included whole blood in dipotassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and silica-coated tubes for plasma and serum separation, respectively. Sample availability varied based on patient consent, local regulations, sample pairing, volume constraints and site-level data reporting. The protocol has been previously published49.

GETUG-AFU26 NIVOREN trial is a French, multicenter, prospective, phase 2 clinical trial evaluating the activity and safety of nivolumab in patients with metastatic ccRCC who had previously failed on or after an antiangiogenic regimen, as previously published29,50,51. Participants received nivolumab at 3 mg kg−1 every 2 weeks and underwent radiological assessment every 8–12 weeks. Treatment was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, withdrawal of consent or death. The primary endpoint was to assess the incidence of high-grade adverse events (grades 3–4 and 5, as per CTCAE v4.0)29. Secondary endpoints included ORR, PFS, OS and exploration of candidate blood biomarkers associated with response and/or prognosis to treatment. Blood samples were collected before and on different visits after Nivolumab start. Available baseline, cycle 3, cycle 7 and progression visit samples were used in this analysis.

SURF trial is a French prospective, randomized, open-label phase 2b study that included patients with metastatic ccRCC treated with sunitinib at a standard 50 mg daily for 4 weeks, followed by a 2-week rest period (4/2)28. Patients requiring a dose adjustment due to toxicity were randomized between the standard 4/2 schedule at a reduced dose of 37.5 mg daily and the experimental 2/1 schedule at 50 mg daily. The primary objective was to assess the median duration of sunitinib treatment in each group. Key secondary objectives included PFS, OS, time to randomization, ORR, safety, sunitinib dose intensity, health-related quality of life and the description of main drivers triggering randomization. An exploratory endpoint included the identification of blood biomarkers related to the activity and/or toxicity of sunitinib. Available baseline blood samples were used in this report. The protocol has been previously published52.

RCC ONCOBIOTICS is a multicentric study evaluating gut microbiota-related biomarkers associated with outcome in advanced RCC treated with ICI alone or in combination with TKI at Gustave Roussy, in France. The study followed standard care until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or completion of 2 years of ICI treatment. Eligibility criteria and baseline data, including recent medications, are in the trial protocol and recorded in electronic case report forms. Blood and stool samples were collected before and on different visits after treatment started.

The ONCOBIOME network dataset32,37 includes data from different cancer cohorts. Data from patients with lung cancer were obtained from the Lung ONCOBIOTICS study (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04567446), a multicenter trial conducted across 14 centers in France and Canada. This study assessed the effect of the microbiome on treatment outcomes in patients with advanced NSCLC receiving anti-PD-(L)1 therapies, either alone or with chemotherapy. Patients were followed under standard care until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or completion of 2 years of ICI therapy. Eligibility criteria and baseline data, including recent medications, were recorded in trial protocols and electronic case report forms. Baseline stool and paired blood samples for sMAdCAM-1 analysis were included in the pooled analysis. Data from patients with colorectal cancer were from the AtezoTRIBE study (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT03721653)53, a phase 2 trial enrolling 218 patients with unresectable stage IV colorectal cancer. Participants were randomized 2:1 to receive FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab with or without atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1). All patients were treatment-naive at the time of initial stool collection. Paired baseline stool and blood samples for sMAdCAM-1 analysis were included in the pooled analysis. Data from patients with bladder cancer were sourced from the French cohort of the STRONG phase 3b trial (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT03084471)54, in which patients who had progressed on chemotherapy received durvalumab (150 mg every 4 weeks until progression). Paired stool and blood samples for sMAdCAM-1 analysis were included in the pooled analysis.

The WELCOME (protocol IRB 20-04021831) trial was conducted at Weill Cornell Medicine and New York Presbyterian Hospital. The protocol is available at https://research.weill.cornell.edu/NYPWelcomeStudy (ref. 30).

FLEMENGHO received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of Leuven (S67011). The FLEMENGHO cohort represents a random population sample stratified by sex and age from a geographically defined area in northern Belgium31.

The reported clinical trials comply with all relevant ethical regulations on research involving human participants.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study design and conduct complied with all relevant regulations regarding the use of human study participants and were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All participants provided written informed consent. Data were reported disaggregated for sex and gender. Consent has been obtained for reporting and sharing individual-level data. Data and sample collection adhered to regulatory, ethical requirements and ICH E6(R2) Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Monitoring of circulating sMAdCAM-1 levels

sMAdCAM-1 was quantified in patients’ plasma samples with Bio-Plex 200 Systems (Bio-Rad) and sMAdCAM-1 kit from R&D Systems (Human Luminex Discovery Assay LXSAHM) at Gustave Roussy or Dana–Farber Cancer Institute laboratory units.

Monitoring of cytokine levels

Cytokine and chemokine concentrations in patient serum were determined using two multiplexed panels that assayed 32 total analytes (Rules-Based Medicine), including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), eotaxin-1, factor VII, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), interferon-γ (IFNγ), IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 p40, IL-12 p70, IL-15, IL-17, IL-18, IL-23, macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β, matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP3), MMP9, MCP-1, stem cell factor (SCF), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), lymphotoxin-α (LTα, formerly known as TNFβ) and VEGF, as previously described55.

Stool samples collection

Stool samples were self-collected by the participants at home according to the International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS)_SOP 004 (https://human-microbiome.org/index.php?id=Sop&num=004) within the ONCOBIOTICS, AtezoTRIBE and French cohort of the STRONG phase 3b trial study protocols. Immediately after the collection, samples were stored in a refrigerator (0–4 °C) until transportation. Upon arrival at the biobank of the recruitment center (within 24 h), samples were stored at −80 °C in plastic tubes. All samples were processed following the International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS) guidelines (SOP 03 V1).

Statistical methods

Quantitative data are described by the number of patients with available data, the number of missing values, the mean, s.d., median, minimum and maximum values and the first and third quartile values (Q1–Q3). sMAdCAM-1 values were compared between groups using the Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis test. Spearman rank correlation analyses between MAdCAM-1 and each of IL-6 and IL-8 were performed to evaluate the relationship between MAdCAM-1 and these inflammatory cytokines. Categorical groups (sMAdCAM-1 high versus low, or the dynamic groups from cycle 1 to cycle 3) were compared between treatments using the chi-squared test. The dynamic values from cycle 1 to cycle 3 (Fig. 4a) were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. OS was defined as the time, expressed in months, from treatment initiation to the date of death or the last known follow-up. Patients alive at the last follow-up date were censored. PFS was defined as the time, expressed in months, from treatment initiation to the date of the first event (progression or death). Patients were censored at the last disease/tumor assessment. The optimal cut-off value was determined by Contal and O’Quigley’s approach for the OS outcome based on sMAdCAM-1 values at cycle 1 in the training cohort56. The assumption of linearity was visually checked by the Martingale residual plots as well as the Restricted Cubic Spline plots (with five knots). The discrimination of the fitted model was assessed by time-dependent AUC at 18 months and integrated AUC index across all follow-up times (ranging 0–1, with higher numbers indicating better discrimination performance)57. The 18-month time point was chosen based on the median follow-up of 18.9 months in this cohort. Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox proportional hazards models were used to compare PFS and OS across the sMAdCAM groups (high versus low at cycle 1, or the dynamic groups from cycle 1 to cycle 3). The analysis at cycle 3 was based on a landmark approach calculated from cycle 3 (3 months) for OS and PFS. Analyses were performed using SAS (v9.4; SAS Institute), R packages (‘rms’ for restricted cubic spline plot; ‘timeROC’ for time-dependent ROC) and SAS Macro for determining the optimal cut-off (https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings/proceedings/sugi28/261-28.pdf).

Metagenomics analysis

DNA was extracted from aliquots of the same stool samples used for metaproteomic analysis using the IHMS SOP 07 V2 H and sequenced on an Ion Proton sequencer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The sequencing was performed at a single site (MetaGenoPolis). Reads were cleaned using Alien Trimmer (v.0.4.0) to (1) remove resilient sequencing adapters and (2) trim low-quality nucleotides at the 3′ side using a quality cut-off of 20 and a length cut-off of 45 bp. Cleaned reads were subsequently filtered from human and other possible food contaminant DNA using the human genome (GRCh38-p13), with an identity score threshold of 95%. For each metagenome, we profiled the taxonomic composition with MetaPhlAn-4 (ref. 58). For α diversity, we computed the per-sample Richness and Shannon indexes59 using the vegan R package60. Differences between groups were assessed using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test. For β-diversity, we computed between-samples Bray–Curtis dissimilarities using the vegan R package60. Differential abundance analysis on taxonomic profiles between groups was performed using the LDA effect size (LefSE) software. The longitudinal analysis was performed with a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (testing only features present in at least ten samples in one of the groups). None of the associations presented adjusted P values with Benjamini–Hochberg correction lower than 0.2. In Fig. 5, microbial features have been subset as the ones presenting 50% prevalence in both tested groups and a raw P value <0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

MetaPhlAn4 profiles and Luminex data for the cohorts included in this study are available via Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30336373). The remaining data will be available within the article, Supplementary Information or source data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Ribas, A. & Wolchok, J. D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 359, 1350–1355 (2018).

Li, H., Van Der Merwe, P. A. & Sivakumar, S. Biomarkers of response to PD-1 pathway blockade. Br. J. Cancer 126, 1663–1675 (2022).

Zitvogel, L., Ma, Y., Raoult, D., Kroemer, G. & Gajewski, T. F. The microbiome in cancer immunotherapy: diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies. Science 359, 1366–1370 (2018).

Derosa, L. et al. Microbiota-centered interventions: the next breakthrough in immuno-oncology?. Cancer Discov. 11, 2396–2412 (2021).

Routy, B. et al. Melanoma and microbiota: current understanding and future directions. Cancer Cell 42, 16–34 (2024).

Alves Costa Silva, C. et al. 1452MO longitudinal analysis reveals gut microbiota shift during standard therapies in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). Ann. Oncol. 33, S1208 (2022).

Dizman, N. et al. Randomized trial assessing impact of probiotic supplementation on gut microbiome and clinical outcome from targeted therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 10, 79–86 (2021).

Elkrief, A. et al. Antibiotics are associated with worse outcomes in lung cancer patients treated with chemotherapy and immunotherapy. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 8, 143 (2024).

Yonekura, S. et al. Cancer induces a stress ileopathy depending on β-adrenergic receptors and promoting dysbiosis that contributes to carcinogenesis. Cancer Discov. 12, 1128–1151 (2022).

Gacesa, R. et al. Environmental factors shaping the gut microbiome in a Dutch population. Nature 604, 732–739 (2022).

Derosa, L. et al. Gut bacteria composition drives primary resistance to cancer immunotherapy in renal cell carcinoma patients. Eur. Urol. 78, 195 (2020).

Kim, C. G. et al. Prior antibiotic administration disrupts anti-PD-1 responses in advanced gastric cancer by altering the gut microbiome and systemic immune response. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 101251 (2023).

Davar, D. et al. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science 371, 595–602 (2021).

Baruch, E. N. et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science 371, 602–609 (2021).

Alves Costa Silva, C., Almonte, A. A. & Zitvogel, L. Oncobiomics: leveraging microbiome translational research in immuno-oncology for clinical-practice changes. Biomolecules 15, 504 (2025).

Routy, B. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation plus anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in advanced melanoma: a phase I trial. Nat. Med. 29, 2121–2132 (2023).

Elkrief, A. et al. 1068P phase II trial of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) plus immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer and cutaneous melanoma (FMT-LUMINate). Ann. Oncol. 35, S707 (2024).

Ciccarese, C. et al. LBA77 fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) versus placebo in patients receiving pembrolizumab plus axitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: preliminary results of the randomized phase II TACITO trial. Ann. Oncol. 35, S1264 (2024).

Porcari, S. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation to improve efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma (TACITO trial). J. Clin. Oncol. 40, TPS407 (2022).

Dizman, N. et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab with or without live bacterial supplementation in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomized phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 28, 704–712 (2022).

Ebrahimi, H. et al. Cabozantinib and nivolumab with or without live bacterial supplementation in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomized phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 30, 2576–2585 (2024).

Routy, B. et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 359, 91–97 (2018).

Pasolli, E., Truong, D. T., Malik, F., Waldron, L. & Segata, N. Machine learning meta-analysis of large metagenomic datasets: tools and biological insights. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, e1004977 (2016).

Derosa, L. et al. Custom scoring based on ecological topology of gut microbiota associated with cancer immunotherapy outcome. Cell 187, 3373–3389 (2024).

Fidelle, M. et al. A microbiota-modulated checkpoint directs immunosuppressive intestinal T cells into cancers. Science 380, eabo2296 (2023).

Choueiri, T. K. et al. Avelumab + axitinib versus sunitinib as first-line treatment for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: final analysis of the phase III JAVELIN Renal 101 trial. Ann. Oncol. 36, 387–392 (2025).

Choueiri, T. K. et al. Updated efficacy results from the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial: first-line avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 31, 1030 (2020).

Thiery-Vuillemin, A. et al. Randomized phase II study to assess the efficacy and tolerability of sunitinib by dose administration regimen in anti-angiogenic naive patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): final analysis of SURF study. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 344 (2022).

Albiges, L. et al. Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): final analysis from the NIVOREN GETUG AFU 26 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 542 (2019).

Ketas, T. J. et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines are detectable in saliva. Pathog. Immun. 6, 116–134 (2021).

Stolarz-Skrzypek, K. Fatal and nonfatal outcomes, incidence of hypertension, and blood pressure changes in relation to urinary sodium excretion. JAMA 305, 1777 (2011).

Birebent, R. et al. Surrogate markers of intestinal dysfunction associated with survival in advanced cancers. Oncoimmunology 14, 2484880 (2025).

Bredon, M. et al. Faecalibaterium prausnitzii strain EXL01 boosts efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncoimmunology 13, 2374954 (2024).

Gopalakrishnan, V. et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 359, 97–103 (2018).

Matson, V. et al. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science 359, 104–108 (2018).

Chen, J. et al. Low-dose irradiation of the gut improves the efficacy of PD-L1 blockade in metastatic cancer patients. Cancer Cell 43, 361–379 (2025).

Zitvogel, L. et al. Impact of the ONCOBIOME network in cancer microbiome research. Nat. Med. 31, 1085–1098 (2025).

Piccinno, G. et al. Pooled analysis of 3,741 stool metagenomes from 18 cohorts for cross-stage and strain-level reproducible microbial biomarkers of colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 31, 2416–2429 (2025).

Marcos-Kovandzic, L. et al. Gut microbiota modulation through Akkermansia spp. supplementation increases CAR T-cell potency. Cancer Discov. 15, 1905–1926 (2025).

Grant, A. J., Lalor, P. F., Hübscher, S. G., Briskin, M. & Adams, D. H. MAdCAM-1 expressed in chronic inflammatory liver disease supports mucosal lymphocyte adhesion to hepatic endothelium (MAdCAM-1 in chronic inflammatory liver disease). Hepatology 33, 1065–1072 (2001).

Laurans, L. et al. An obesogenic diet increases atherosclerosis through promoting microbiota dysbiosis-induced gut lymphocyte trafficking into the periphery. Cell Rep. 42, 113350 (2023).

Feliu, V. et al. Distant antimetastatic effect of enterotropic colon cancer-derived α4β7+CD8+ T cells. Sci. Immunol. 8, eadg8841 (2023).

Zitvogel, L., Fidelle, M. & Kroemer, G. Long-distance microbial mechanisms impacting cancer immunosurveillance. Immunity 57, 2013–2029 (2024).

Derosa, L. et al. Intestinal Akkermansia muciniphila predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Med. 28, 315–324 (2022).

Belluomini, L. et al. 1172O Akkermansia muciniphila-based multi-omic profiling in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 35, S762 (2024).

Goel, A. et al. Toward a health-associated core keystone index for the human gut microbiome. Cell Rep. 44, 115378 (2025).

Ebrahimi, H. Effect of CBM588 in combination with cabozantinib plus nivolumab for patients (pts) with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, LBA104 (2023).

NIH. A phase 1/2 study of Oncobax®-AK administered in combination with immunotherapy to patients with advanced solid tumors. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05865730 (2023).

Motzer, R. J. et al. Avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1103–1115 (2019).

Flippot, R. et al. Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in brain metastases from renal cell carcinoma: results of the GETUG-AFU 26 NIVOREN multicenter phase II study. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 2008–2016 (2019).

Carril-Ajuria, L. et al. Baseline circulating unswitched memory B cells and B-cell related soluble factors are associated with overall survival in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab within the NIVOREN GETUG-AFU 26 study. J. Immunother. Cancer 10, e004885 (2022).

Mouillet, G. et al. Open-label, randomized multicentre phase II study to assess the efficacy and tolerability of sunitinib by dose administration regimen (dose modification or dose interruptions) in patients with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: study protocol of the SURF trial. Trials 19, 221 (2018).

Antoniotti, C. et al. Upfront FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab with or without atezolizumab in the treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (AtezoTRIBE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 23, 876–887 (2022).

Sonpavde, G. P. et al. Primary results of STRONG: an open-label, multicenter, phase 3b study of fixed-dose durvalumab monotherapy in previously treated patients with urinary tract carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer 163, 55–65 (2022).

Choueiri, T. K. et al. Integrative analyses of tumor and peripheral biomarkers in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 14, 406–423 (2024).

Contal, C. & O’Quigley, J. An application of changepoint methods in studying the effect of age on survival in breast cancer. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 30, 253–270 (1999).

Uno, H., Cai, T., Tian, L. & Wei, L. J. Evaluating prediction rules for t-year survivors with censored regression models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 102, 527–537 (2007).

Blanco-Míguez, A. et al. Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 1633–1644 (2023).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423 (1948).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.5-2, https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.vegan (2018).

Acknowledgements

Patients, investigators and study teams on the clinical trials are included. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Pfizer and EMD Serono for providing samples and datasets from the JAVELIN Renal 101 (NCT02684006) clinical trial, to the Wyss Institute for allowing us to use their instrument and to Shanda Lightbown and Nina LoGrande for their technical assistance. T.K.C. is supported in part by the Dana–Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Kidney SPORE (2P50CA101942-16) and Program 5P30CA006516-56, the Kohlberg Chair at Harvard Medical School and the Trust Family, Michael Brigham, Pan Mass Challenge, Hinda and Arthur Marcus Fund and Loker Pinard Funds for Kidney Cancer Research at DFCI. L.Z. and L.D. are supported by the SEERAVE Foundation; the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under grant agreement 101095604 (project acronym, PREVALUNG-EU; project title, Personalized Lung Cancer Risk Assessment Leading to Stratified Interception); the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement 825410 (ONCOBIOME project); Institut National du Cancer (INCa); Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) Ileobiome—19-CE15-0029-01; ANR RHU5 ‘ANR-21-5 RHUS-0017’ (‘IMMUNOLIFE’); MAdCAM INCA_16698; Ligue contre le Cancer; the LabEx Immuno-Oncology (ANR-18-IDEX-0001); la Direction Générale de l’Offre de Soins (DGOS); Université Paris-Saclay; PACRI network; Ligue contre le Cancer (équipes labellisées Program ‘Equipe labellisée LIGUE’ EL2016.LNCC (VT/PLP)); ANR—Projets blancs; ANR under the frame of E-Rare-2 the ERA-Net for Research on Rare Diseases; AMMICa US23/CNRS UMS3655; Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC); Association ‘Le Cancer du Sein Parlons-en!’; Cancéropôle Ile-de-France; Chancellerie des Universités de Paris (Legs Poix); Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM); a donation by Elior; European Research Area Network on Cardiovascular Diseases (ERA-CVD MINOTAUR); Gustave Roussy Odyssea; Fondation Carrefour; INCa; Inserm (HTE); Institut Universitaire de France; LeDucq Foundation; SIRIC Cancer Research and Personalized Medicine (CARPEM); and the ARC (projects MICROBIONT-PREDICT (2021) Made-IT (2023)). C.A.C.S., L.D. and L.Z. were supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement 964590 (project acronym, IHMCSA; project title, International Human Microbiome Coordination and Support Action). L.D. is supported by AACR 2025 Career Development Award in Lung Cancer Research and Association Robert Debré pour la Recherche Médicale. N.S. was supported by the European Research Council (ERC-CoG microTOUCH-101045015), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program (ONCOBIOME-825410 project), the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (1U01CA230551) and the Premio Internazionale Lombardia e Ricerca 2019. Patient plasma samples were provided by EMD Serono, the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany (CrossRef Funder ID 10.13039/100009945). The bladder cancer cohort from the IOPREDI ancillary study/STRONG study (NCT03084471) was funded by AstraZeneca. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.A.C.S., L.D., L.Z. and L.A. designed the study. C.A.C.S., M.M., R.M.S., M.F., G.M.L., R.B., E.S., C.S., R.F., J.B.M., N.S., A.T.V., S.F., T.K., B.E., L.D., L.Z., T.K.C. and L.A. contributed to data acquisition and investigation. C.A.C.S., M.M., R.M.S., C.Z., W.X., E.P., G.P., C.D., A.M., D.V. and L.D. performed formal analysis and validation. L.Z., T.K.C. and L.A. supervised the study. C.A.C.S., M.M., R.M.S., C.Z., W.X., E.P., L.D., L.Z., T.K.C. and L.A. wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

C.A.C.S. reports speaker honoraria fees from Ipsen, AstraZeneca and Bristol Myers-Squibb. L.A. received advisory, consulting or honoraria fees (all paid to their institution) from AMGEN, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers-Squibb, Daiichi, EISAI, Ipsen, Janssen, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Telix and Xencor. L.A. also received travel and accommodations expenses from Bristol-Myers Squibb, IPSEN, MSD and Pfizer. T.K.C. reports institutional and/or personal, paid and/or unpaid support for research, advisory boards, consultancy and/or honoraria in the past 5 years, ongoing or not, from Alkermes, Arcus Bio, AstraZeneca, Aravive, Aveo, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bicycle Therapeutics, Calithera, Caris, Circle Pharma, Deciphera Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, EMD Serono, Exelixis, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead, HiberCell, IQVA, Infinity, Institut Servier, Ipsen, Jansen, Kanaph, Lilly, Merck, Nikang, Neomorph, Nuscan/PrecedeBio, Novartis, Oncohost, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi/Aventis, Scholar Rock, Surface Oncology, Takeda, Tempest, Up-To-Date, CME and non-CME events (Mashup Media Peerview, OncLive, MJH, CCO and others), and Xencor, outside the submitted work. Institutional patents have been filed on molecular alterations and immunotherapy response/toxicity, rare genitourinary cancers and ctDNA/liquid biopsies. Equity holdings include Tempest, Pionyr, Osel, PrecedeBio, CureResponse, InnDura Therapeutics, Primium, Abalytics and Faron Pharma. Committee involvement includes NCCN, GU Steering Committee, ASCO (BOD 6/2024-), ESMO, ACCRU and KidneyCan. Medical writing and editorial assistance support may have been funded by communications companies in part. T.K.C. has no speaker’s bureau activities. T.K.C. has mentored several non-US citizens on research projects with potential funding (in part) from non-US sources/Foreign Components. The institution (Dana–Farber Cancer Institute) may have received additional independent funding from drug companies or/and royalties potentially involved in research around the subject matter. T.K.C. is supported in part by the Dana–Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Kidney SPORE (2P50CA101942-16) and Program 5P30CA006516-56, the Kohlberg Chair at Harvard Medical School and the Trust Family, Michael Brigham, Pan Mass Challenge, Hinda and Arthur Marcus Fund and Loker Pinard Funds for Kidney Cancer Research at DFCI. A.T.V. has received payment to their institution linked to the SURF clinical trial from Pfizer; has received a research grant for their institution from Pfizer, Bayer and Ipsen; has received consulting fees, payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events and support for attending meetings and/or travel from Roche, MSD, JNJ, BMS, Astellas, Ipsen, Astrazeneca and Novartis; has participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for DSMB (BIONIKK trial); has been a BMS employee since 2023 and has BMS stocks; and is a member of the steering committee of the French GETUG academic group. E.S. received research funding from Roche/Genentech and Oncohost. R.F. reports research funding from Bayer and honoraria fees from Astellas, Bayer, Johnson and Johnson, Ipsen, Eisai, Pfizer, MSD and Merck Serono. W.X. reports consulting or advisory roles with PCCTC. C.S. reports speaker honoraria and advisory board fees from Eisai. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Jong-Hyeon Jeong, Brandon Manley and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Ulrike Harjes, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

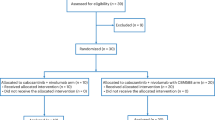

Extended Data Fig. 1 Study participant flowcharts.

Flowchart of study participants with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in the JAVELIN Renal 101 (a), SURF (b) and NIVOREN (c) trials. Patients with unavailable plasma samples, outlier values, or who were not treated were excluded. ITT, intention-to-treat.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Prognostic analysis of sMAdCAM-1.

a, Restricted cubic spline plot showing the predicted risk score (log relative hazard, solid line) and 95% confidence interval (shaded area) for overall survival (OS) based on the continuous sMAdCAM-1 values (ng/mL). Lower sMAdCAM-1 values were associated with a higher risk of death, and the curve tended to be flattened after values >180 ng/mL. b, Martingale residual plot.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Soluble MAdCAM-1 linear distribution.

a,b, Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of progression-free survival (PFS; a) and overall survival (OS; b) in patients from the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial showing both superposing curves for the intention-to-treat population and in the subset of patients analyzed in the biomarker ancillary study cohort from the trial, across both treatment arms. Risk tables indicate the number of patients at risk at each time point. c,d, Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of PFS (c) and OS (d) stratified by sMAdCAM-1 concentrations in the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial. Patients were dichotomized using a threshold of 180 ng/mL into low (≤180 ng/mL) and high (>180 nng/mL) sMAdCAM-1 groups. Survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test; P values are shown. Risk tables indicate the number of patients at risk at each time point.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Levels of sMAdCAM-1 do not impact progression-free survival (PFS) in the SURF and NIVOREN trials (validation cohorts).

a,b, Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of PFS stratified by sMAdCAM-1 concentrations in the SURF (a) and NIVOREN (b) trials. Patients were dichotomized using a threshold of 180 ng/mL into low (≤180 ng/mL) and high (>180 ng/mL) sMAdCAM-1 groups. Survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test; P values are shown. Risk tables indicate the number of patients at risk at each time point.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Levels of sMAdCAM-1 anticorrelate with Enterocloster SGB14313.

a–c, Scatterplots showing the relationship between mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) concentrations in plasma samples and Enterocloster SGB14313 relative abundance in paired stool samples of patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC, N = 55 paired samples; a), urothelial cancer (UC, N = 61 paired samples; b) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC, N = 188 paired samples; c). Each point represents an individual sample measurement. The dotted line represents the linear regression fit. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using a two-sided Spearman test without adjustments for multiple comparisons; exact P values are shown.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Luminex assay, cytokine and clinical data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Luminex assay and clinical data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Luminex assay and clinical data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Luminex assay and clinical data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Luminex assay and metagenomics data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Luminex assay and microbiota biomarker data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Luminex assay and clinical data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Luminex assay and clinical data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Luminex assay and clinical data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Luminex assay and metagenomics data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alves Costa Silva, C., Machaalani, M., Saliby, R.M. et al. Soluble MAdCAM-1 as a biomarker in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04067-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04067-x