Abstract

The inflammatory reflex, in which vagus nerve signaling modulates cytokine production, is dysregulated in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). RESET-RA, a pivotal, double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial, evaluated a vagus nerve-targeted neuromodulation system for RA in 242 patients with inadequate response/intolerance to biological/targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Patients were randomized to active or sham stimulation for 3 months, and then all received open-label stimulation with results reported to 12 months. The primary end point was 3-month American College of Rheumatology 20% (ACR20) response. ACR20 rates were higher with active simulation than with sham at 3 months (35.2% versus 24.2%, P = 0.0209), which further improved in open-label to 50.0% at 6 months and 52.8% at 12 months (all-completers). Adverse events occurred in a similar proportion of patients in both arms. Related serious adverse events (rate = 1.6%) were all perioperative, and resolved. Vagus nerve-mediated neuroimmune modulation for RA achieved its primary efficacy end point and produced durable clinical benefits with a favorable safety profile. ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04539964.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Patients with uncontrolled rheumatoid arthritis (RA) suffer from painful chronic joint inflammation, systemic inflammation and progressive disability due to ongoing structural joint damage. Despite the availability of numerous conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs; for example, methotrexate) and biological or targeted synthetic DMARDs (b/tsDMARDs) with distinct mechanisms of action, treatment failure remains a challenge for many patients due to lack of initial response, loss of response over time or intolerance to b/tsDMARDs1,2.

The central nervous system governs homeostatic control of immune responses and bone turnover through innate neuroimmune and osteo-targeted reflexes, including the vagus nerve-mediated ‘inflammatory reflex’. This reflex is dysregulated in RA; tonic vagus nerve activity is diminished, and reduction in vagal tone precedes the onset of clinical disease3,4,5. Actively stimulating the vagus nerve can engage the inflammatory reflex, resulting in acetylcholine release and specific agonism of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on immune cells6,7. Subsequent modulation of intracellular pathways acting through NFkB, JAK/STAT and the inflammasome leads to reduced production of an array of proinflammatory cytokines (for example, TNF, IL-6, IL-1β)8. This broad-spectrum immunomodulation retains cytokine network bioavailability, thereby allowing reduction and resolution of inflammation while maintaining competent immunosurveillance against foreign pathogens and precancerous cells9,10,11.

Prior clinical studies of implanted devices support this mechanism of action as a treatment approach for RA12,13,14. In these studies, a total of 27 patients with RA were stimulated with implanted neurostimulators targeting the vagus nerve and although not designed to determine efficacy, demonstrated clinical improvements with reductions in proinflammatory cytokines12,13. Accordingly, we studied the safety and efficacy of an integrated neuromodulation system to treat patients with moderately-to-severely active RA following an inadequate response or intolerance to one or more b/tsDMARDs, in the pivotal (similar to a phase III drug trial) RESET-RA trial.

We observed in this randomized, controlled trial of 242 patients that the primary end point of a difference between stimulation and sham in American College of Rheumatology 20% (ACR20) responses at 3 months was achieved, with further clinical improvements documented at 12 months.

Results

Patient disposition

Following approval by the institutional review board (Advarra centrally and three local boards), a total of 405 patients diagnosed with RA were screened for study participation, 243 were consented and enrolled, and 242 completed standard b/tsDMARD washout per protocol requirements before device implantation (intent-to-treat (ITT) population). Figure 1 provides patient disposition from screening through 12 months. Patients were randomized to either arm 1 (stimulation treatment for 3 months, then continued to open-label stimulation; 122 patients) or arm 2 (sham treatment for 3 months, then crossover to open-label stimulation; 120 patients) following postsurgical recovery. One consented patient was discontinued from the study before device implantation for logistical reasons; the patient was not randomized but was followed for safety per protocol. A single patient randomized to arm 1 did not continue in the study after the 3-month primary end point. The demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients at baseline are presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 1–3. Overall, mean duration of RA was 12.4 years, and the mean (s.d.) and median (range) number of prior b/tsDMARDs was 2.6 (1.9) and 2.0 (1–12), respectively. The total number of patients (% overall population) who had prior exposure to 1 b/tsDMARD was 94 (38.8%), those exposed to >1 b/tsDMARDs was 148 (61.2%), those exposed to ≥3 b/tsDMARDs were 95 (39.3%) and to a tsDMARD were 49 (20.2%). At the time of consent, 78.5% of patients were taking stable doses of a single csDMARD, of which 51.1% were receiving methotrexate. The remainder received at least two csDMARDs. Open-label data are reported through 12 months; 233 patients from the ITT population completed the 12-month visit.

Treatment

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-conditional pulse generator, the ‘implant’, was implanted and fitted within a contoured silicone pod that was secured directly to the left cervical vagus nerve15 (Fig. 2). Once implanted, targeted electrical pulses were delivered to the vagus nerve to engage the inflammatory reflex and modulate immune activity. The stimulation parameters were controlled by site-specific programmers using a tablet-based software application that transmitted information through a charger worn by the patient (Fig. 2). Those patients randomized to sham stimulation always received 0 mA, regardless of the stimulation strength set by the programmers, who were blinded to treatment arm assignment.

The integrated neuromodulation system consists of an implant and pod. The implant is placed in the pod to position and hold it in place on the left cervical vagus nerve to ensure direct contact for precise stimulation. The implant is approximately 2.5 cm in length and weighs 2.6 g. To charge the implant, patients wear a wireless device (charger) around the neck for a few minutes, once a week. The implant is programmed by healthcare providers (HCPs) using a proprietary application (programmer). Adapted from ref. 16, by permission of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

The active stimulation intensity was set to an upper comfort level (maximum = 2.5 mA) and delivered a 1-min train of pulses to the vagus nerve once daily at 10 Hz16 (arm 1 = 1.8 mA average; arm 2 = 0 mA). The 3-month assessments were completed for 99.2% of patients, with two missed visits (one in each arm). Supplementary medications that were prohibited per protocol before the 3-month assessment (‘rescue’) occurred in four patients in arm 1, and five patients in arm 2. All patients, healthcare providers, investigators, joint evaluators and the sponsor were blinded to group assignment until all patients completed assessments at 3 months and the database was locked for primary efficacy analysis.

Following the primary end point assessment at 3 months, all patients were eligible to continue in the study for open-label active stimulation treatment. Adjunctive pharmacological treatments (‘augmented therapy’) were permitted throughout the open-label stimulation period at the discretion of the rheumatologist in consultation with the patient, with 17.8%, 24.8% and 32.2% of patients receiving protocol-defined augmented therapy at 6, 9 and 12 months, respectively. At these timepoints, 88.0%, 80.6% and 75.2% of patients remained free from adjunctive b/tsDMARD therapy. During the open-label stimulation period, 96.3% of patients in the ITT population completed 12-month assessments.

Primary outcome

The primary end point was a difference in proportion of patients in the ITT population receiving stimulation versus sham who achieved an ACR20 response at the 3-month visit from baseline (day of consent). ACR20 response, as defined by the American College of Rheumatology, is a dichotomous composite end point representing the proportion of patients who achieve at least a 20% improvement in both the tender and swollen joint counts (out of a maximum of 28 joints) and in ≥3 of the following 5 additional measures—Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) score, patient global assessment of disease, patient pain, evaluator’s global assessment of disease and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein concentration17. The primary end point was met at 3 months; ACR20 response was achieved by 35.2% of arm 1 (stimulation) and by 24.2% of arm 2 (sham; Fig. 3a). The stratification-adjusted difference in ACR20 response between arms was 11.8% (P = 0.0209, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.6, 23.1). At 3 months, Bang’s blinding index scores were <0.3 for patients, joint assessors and co-investigators, which indicated satisfactory blinding at the time of primary end point assessment (Supplementary Table 4).

a, The percentage of patients who had an ACR20 response at 3 months, the primary efficacy end point of this study. Patients with missing data or who received rescue treatment were imputed as nonresponders. Stimulation, n = 122; sham, n = 120. b, The percentage of patients who had an ACR20 response through 12 months. Within double-blind period; stimulation, n = 122; sham, n = 120. At 6, 9 and 12 months, n = 97, 89, 77 in arm 1, respectively, and n = 98, 87, 81 in arm 2, respectively. c, The percentage of patients who had a DAS28-CRP good or moderate response according to the EULAR criteria. At 3, 6, 9 and 12 months, n = 118, 95, 85, 75 in arm 1, respectively, and n = 117, 98, 82, 79 in arm 2, respectively. d, The percentage of patients who had achieved LDA or remission by DAS28-CRP criteria (score < 3.2). At 3, 6, 9 and 12 months, n = 118, 95, 85, 75 in arm 1, respectively, and n = 117, 98, 82, 79 in arm 2, respectively. All data are presented as the percentage of each group with s.e. Formal statistical analyses were only performed at the 3-month study visit (double-blind) with the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel (CMH) test using stratification factors based on prespecified criteria (prior inadequate or lost response to a tsDMARD, prior inadequate or lost response to ≥4 biological DMARDs with ≥2 mechanisms of action and RA disease severity defined as either <4 TJC28 or <4 SJC28 at day 0), at a one-sided significance level of 0.025. P = 0.0209, 95% CI = 0.6–23.1 (a,b). P = 0.0048, 95% CI = 7.3–31.7 (c). P = 0.0154, 95% CI = 1.2–21.6 (d). After 3 months (open-label stimulation), patients were permitted to augment therapy with adjunctive drugs without restriction. Data presented at 6, 9 and 12 months in b–d include all patients completing the visit who had not used augmented therapy. Percent of patients with augmented therapy—6 months = 17.8%, 9 months = 24.8%, 12 months = 32.2%. BL, baseline. *P < 0.025, **P < 0.01.

Secondary outcomes

Four key secondary end points were evaluated, each representing the difference in the proportion of patients in the ITT population receiving stimulation versus sham who achieved the end point at 3 months. End points included a DAS28-CRP good/moderate response according to the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria; a DAS28-CRP minimal clinically important difference (MCID; −1.2); a HAQ-DI MCID (−0.22); and an ACR20 response from day 0 (randomization). Among the key secondary end points, multiplicity adjustment was performed using Hochberg’s step-up procedure. All secondary end points showed a higher response rate for stimulation compared to sham, although significance was achieved for only EULAR good/moderate response (Supplementary Table 5). EULAR good/moderate response was achieved by 60.7% of arm 1 (stimulation) and by 41.7% of arm 2 (sham) (multiplicity-adjusted P = 0.0048, 95% CI = 7.3, 31.7). DAS28-CRP MCID was achieved by 45.1% of arm 1 and by 32.5% of arm 2 (multiplicity-adjusted P = 0.0528, 95% CI = 1.1, 25.3). HAQ-DI MCID was achieved by 45.9% of arm 1 and by 36.7% of arm 2 (multiplicity-adjusted P = 0.0797, 95% CI = −3.3, 21.4). ACR20 from day 0 was achieved by 31.1% of arm 1 and by 22.5% of arm 2 (multiplicity-adjusted P = 0.0797, 95% CI = 1.1, 25.3).

Exploratory outcomes

All other efficacy end points at 3 months and within the open-label stimulation period were exploratory. Open-label stimulation was initiated in both arms after the 3-month controlled-blind period. Response rates for primary and all secondary end points increased further in arm 1, while patients in arm 2 demonstrated clinical improvements following initiation of stimulation. Clinical end point responses were sustained in both arms through 12 months (Supplementary Table 5).

Clinically relevant composite measures

Prespecified clinically relevant composite outcome measures included EULAR good/moderate response, low disease activity (LDA) or remission by DAS28-CRP, and LDA or remission by the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) evaluated at 3 months (sham-controlled-blinded period) and also during the open-label stimulation period at 6 months, 9 months and 12 months (Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Table 6). Arm 1 (stimulated) had significantly higher rates than arm 2 (sham) at 3 months for EULAR good/moderate response (% responders ± s.e.m.—arm 1 = 60.7% ± 4, arm 2 = 41.7% ± 5; P = 0.0048, 95% CI = 7.3, 31.7) and DAS28-CRP LDA/remission (% rate ± s.e.m.—arm 1 = 26.1% ± 4, arm 2 = 15.4% ± 3; P = 0.0154, 95% CI = 1.2, 21.6). Difference in rates for CDAI LDA/remission at 3 months did not reach significance (% rate ± s.e.m.—arm 1 = 23.3% ± 4, arm 2 = 16.0% ± 3; P = 0.0648, 95% CI = −2.1, 17.7), although favored stimulation.

All composite outcome measures improved further in both arms during the open-label period, when all patients received stimulation, with responses maintained at 12 months. Across both arms, the percentage of patients who achieved an ACR20 response at 12 months was 57.6%, EULAR good/moderate response was 77.3%, DAS28-CRP LDA/remission was 44.8%, and CDAI LDA/remission was 43.9% by a nonaugmented analysis (Fig. 3b–d and Supplementary Table 6). Comparable results were observed by an all-completers analysis, which additionally included those patients who received augmented therapy (Supplementary Table 6). Patient satisfaction rate using a five-point Likert rating scale revealed that 78.1% of patients were somewhat to very satisfied with the therapy at 6 months (satisfaction %—arm 1 = 75.6%, arm 2 = 80.7%; Supplementary Table 10).

Outcome Measures in Rheumatology RA MRI score

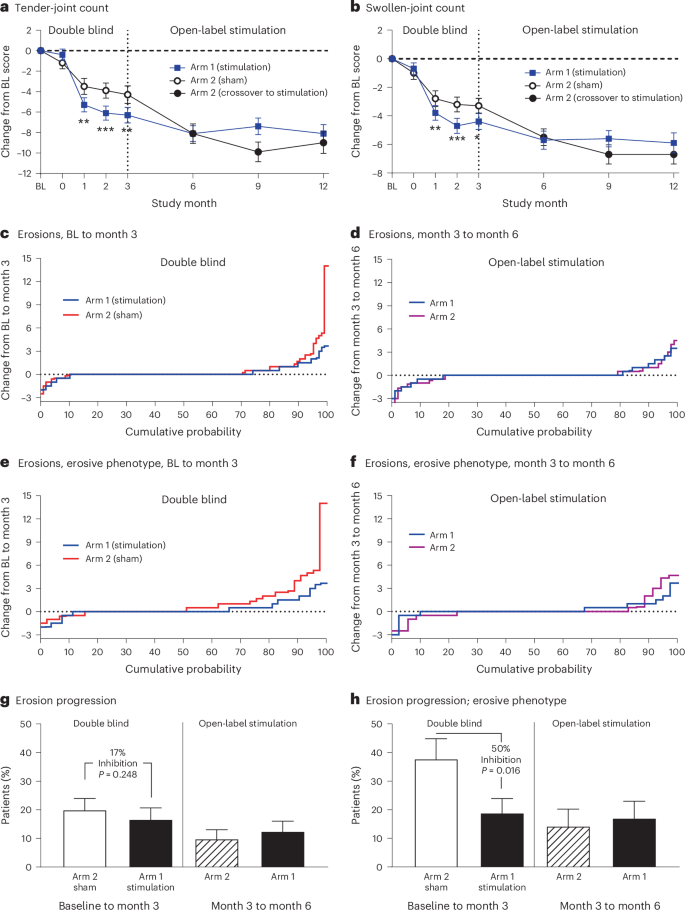

Treatment effects on joint inflammation and erosions were assessed using gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the hand and wrist at baseline (pre-implant), 3 months and 6 months. Images were analyzed with the validated Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) RA MRI score (RAMRIS) to objectively quantify bone erosion progression18. In the ITT population, a total of 216 patients had RAMRIS scores measured at both baseline and 3 months (arm 1, n = 109; arm 2, n = 107). At baseline, bone erosion scores were comparable between arm 1 and arm 2, with a mean (s.d.) erosion score of 10.4 (11.7) and 9.5 (12.1), respectively. From baseline to 3 months, a smaller proportion of patients in arm 1 (stimulation) exhibited progression of bone erosions (>0.5 increase in score) in the evaluated hand and wrist compared with arm 2, although the difference was not significant (P = 0.248; Fig. 4c,g). In the prespecified subgroup analysis of patients with a phenotype enriched for erosive damage risk (defined as synovitis score of 2 or more on any individual joint, at least four joints with a score of 1 or any joint with osteitis at baseline), a total of 105 patients met the erosive phenotype criteria (arm 1, n = 57; arm 2, n = 48). In this subgroup, the rate of progression of bone erosion from baseline to 3 months was significantly decreased in arm 1 (stimulation = 18.9%) as compared with arm 2 (sham = 37.8%, P = 0.016; Fig. 4e,h). During the open-label stimulation period from 3 months to 6 months, the rate of progression of bone erosion declined in arm 2 (Fig. 4g,h).

a,b, The mean change and s.e. in the number of tender and swollen joints and as compared to baseline are shown in a (tender-joint count) and in b (swollen-joint count). The vertical line at 3 months indicates the end of the double-blind period of the study and the beginning of open-label stimulation. For a and b, within double-blind period: stimulation, n = 116; sham, n = 114. At 6, 9 and 12 months, n = 96, 88 and 77 in arm 1, respectively, and n = 98, 87 and 80 in arm 2, respectively. c–f, The cumulative probability of a change in erosion score, as assessed via the OMERACT RAMRIS. The right part of the curve (positive values on the y axis) represents erosion progression (worsening), the left part of the curve represents erosion regression (improvement) and the flat line at y = 0 represents no change in erosion score. c,e, Plot change from baseline to 3 months during the controlled-blind period. d,f, Plot change from 3 months to 6 months during open-label stimulation. Patients who completed the 3-month and 6-month visits without augmented therapy are included in c and d. Patients at risk for erosion progression are included in e and f. g,h, The percentage of patients who had erosion progression, defined as >0.5 increase in RAMRIS erosion score by MRI. The vertical line at 3 months demarcates the double-blind period between baseline and 3 months and the open-label stimulation period between 3 months and 6 months. Data are presented as the mean (a,b) or the percentage of each group (g,h) with s.e. Statistical analyses were only performed at points through 3 months; a and b with mixed-effect model repeated measures and g and h with the CMH test. All tests use one-sided significance level of 0.025. In a, P = 0.0021, 0.0004 and 0.0014 at month 1, 2 and 3, respectively. In b, P = 0.0097, 0.0009 and 0.0131 at month 1, 2 and 3, respectively. *P < 0.025, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Sensitivity analyses

Primary and secondary end point response measures during the open-label period were consistent with analyses using nonresponder imputation to account for missed visits or study dropouts (Supplementary Table 5). At 12 months from baseline, ACR20 response by nonresponder imputation were 50.4% (61/121) and 51.7% (62/120) for arm 1 and arm 2, respectively; EULAR good/moderate response was 70.2% (85/121) and 70.8% (85/120) for arm 1 and arm 2, respectively; DAS28-CRP MCID was 60.3% (73/121) and 55.8% (67/120) for arm 1 and arm 2, respectively; and HAQ-DI MCID was 54.5% (66/121) and 55.8% (67/120) for arm 1 and arm 2, respectively.

Safety

The safety evaluation was based on all available data at the time of reporting, with a mean implant duration of >700 days. No deaths or unanticipated adverse device effects occurred at any point during the trial. Overall, adverse events occurred in a similar proportion of patients in both arms during the controlled period (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 11). Nonserious related adverse events were predominantly associated with the implantation procedure (Supplementary Table 13), reported in 38 patients (15.6%; 52 events). These were consistent with those seen in other devices implanted near the cervical vagus nerve. The most frequent events were mild to moderate hoarseness, classified as either vocal cord paresis (4.5%, n = 11) or dysphonia (2.9%, n = 7). These adverse events resolved over the course of up to one year; three patients received bulk injection fillers into the left vocal cord and some underwent voice therapy. No cases required surgical intervention. Additional implantation-related adverse events of mild to moderate severity occurred in 5.4% of patients related to the surgical site (n = 13), including swelling/inflammation (n = 6), hypoesthesia (n = 2), stitch abscess/infection (n = 2), pain (n = 1), erythema (n = 1) and a suture-related complication (n = 1). Active stimulation (1 min daily) was generally well tolerated. Mild to moderate stimulation-related events, most commonly pain, occurred in 4.2% of patients (n = 10) during the controlled period and 4.6% (n = 11) during long-term follow-up. These typically resolved after reducing stimulation strength or adjusting the time of delivery, without interruption of therapy.

Overall, during the controlled period and long-term follow-up, 4 of 242 ITT patients (1.7%) experienced a serious adverse event related to surgical procedure, all having an onset during the perioperative period (1.6% of the 243 enrolled patients in the safety population). All these events resolved without clinically significant sequelae. There was one event of postoperative incision-site swelling, one event of transient vocal cord paresis (presented as hoarseness) with dysphagia, one intraoperative pharyngeal perforation (that occurred during an explantation procedure and was immediately repaired) and one event of postoperative dysphonia (that presented as hoarseness) possibly associated with postoperative progression of age-related vocal cord bowing (presbylarynges; Table 2). There were no serious adverse events related to the active stimulation.

A total of six patients underwent device removal (explantation) before 12 months. All explantations were performed as outpatient, elective procedures. The reasons for explantation included a nonfunctioning device (n = 1), chronic pain at the incision site (n = 1), gastrointestinal symptoms attributed to stimulation therapy (n = 1) and patients who requested removal due to perceived lack of benefit (n = 3). During the explantation procedure, the vagus nerve appeared to be normal on visual inspection.

Details of the safety results during the open-label stimulation period are provided in Table 2 and Supplementary Tables 17–21. No safety concerns have been identified through other protocolized safety monitoring assessments (for example, vital signs, hematology, ECG, blood pressure, heart rate). All adverse events of infection, major adverse cardiac events and malignancies were reviewed and determined to be unrelated, and the rates were within the expected range for the target RA patient population.

Discussion

RESET-RA is the first randomized, sham-controlled trial to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of a neuroimmune modulation device to treat any autoimmune disease, specifically RA. Compliance with therapy and preservation of treatment blinding were achieved through automated nighttime delivery of active stimulation. Efficacy was observed in the 3-month blinded-control period and further supported by improvement during the open-label stimulation period through 12 months, with low usage of adjunctive b/tsDMARDs. In patients with high baseline risk for structural damage, active stimulation substantially reduced progression of bone erosions, as assessed by quantitative MRI joint imaging.

The enrolled study population reflected a spectrum of treatment experiences, including 43% classified with ‘difficult-to-treat’ (D2T) RA, that is, those who had previously failed multiple b/tsDMARDs, with at least 2 different mechanisms of action19, and 39% who had failed a single b/tsDMARD. The patient’s choice to undergo surgical implantation of an experimental device rather than switch to another b/tsDMARD indicated strong patient preference for nonpharmacologic treatment options. Unlike most trials for new therapies in this population, RESET-RA did not impose a requirement for elevated CRP at baseline, allowing inclusion of patients with moderate-to-severe RA regardless of CRP status who would normally be excluded from studies of new RA therapies. This inclusive design reflects the broader United States (US) RA population, where CRP is not uniformly elevated despite active disease20.

Efficacy measures were consistent with those used in phase 3 RA drug trials. Rates of ACR20 response, EULAR moderate/good response and LDA/remission by DAS28-CRP criteria were all higher with stimulation compared with sham at 3 months (LDA/remission by CDAI was numerically higher). Blinding across all assessed parties was satisfactory at the primary clinical end point, and the sham response rate was consistent with placebo response rates reported in phase 3 trials of pharmacologic therapies in bDMARD-refractory patients21,22,23,24. During the open-label period, therapeutic responses in arm 1 continued to improve over time, while patients in arm 2 demonstrated clinical benefits following crossover to active stimulation. The observed clinical improvement past 3 months was consistent with the pilot study of this neuromodulation system in patients with RA12,14. In both arms, the ACR20, clinical LDA/remission and EULAR good/moderate response rates were comparable to those achieved with effective pharmacologic therapies in similar bDMARD-refractory patients by 6 months, and were sustained through 12 months21,22,23,24.

Protection from progressive structural damage was documented by MRI. Although most patients who have had an inadequate response to b/tsDMARD therapy were unlikely to have had MRI-observable erosive progression over a 3-month period (as was observed in the ITT population), the subgroup with elevated synovitis and/or osteitis at baseline was at higher risk for progression25. In this higher erosive-risk phenotype, active stimulation attenuated the rate of erosion progression, a clinically relevant effect, given that progressive MRI-detectable erosions at 3 months predict radiographic progression at 12 months and subsequent functional decline26,27.

The observed protection from bone erosions is consistent with several known mechanisms of vagus nerve-targeted neuroimmune modulation. For example, vagotomized mice become osteoporotic, while stimulating the vagus nerve leads to increased bone formation12,28,29,30. Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve induces release of specialized pro-resolving mediators and neurotransmitters that signal through specific receptors including the ChemR23 lipid receptors, acetylcholine receptors and adrenergic receptors on osteoblasts, osteoclasts and osteocytes resulting in reduction of osteoclastogenesis and osteoclastic activity28,30,31,32,33,34,35. The protective effect of this therapy on bone may therefore be mediated by the canonical RANKL/osteoprotegerin pathway (neuroimmune modulation decreases RANKL and increases osteoprotegerin, the decoy ligand for RANKL) as well as direct effects on osteoblasts, osteoclasts and osteocytes28,30,31,32,33,34,35. While these pathways are biologically plausible, confirmation in RA patients will require future targeted mechanistic studies.

In evaluating the safety of drugs used to treat RA, there has been a critical focus on increased rates of serious infections, major cardiovascular, venous and/or arterial thrombotic events and malignancies, reflecting the immunosuppressive mechanisms of action of b/tsDMARDs36. The safety data from the RESET-RA trial through 12 months showed no increase in these adverse events, consistent with the well-established safety data of vagus nerve stimulation accumulated over decades of use in nonautoimmune disease populations37. No hemodynamic changes, including hypotension or bradycardia, were detected during the study. The rate of related serious adverse events was low, associated with the surgery, all of which were successfully managed to clinical resolution, and with no events observed in the open-label period. Nonserious adverse events were predominantly associated with the implantation procedure, were mild or moderate in severity and consistent with the inherent risks of any surgical procedure performed near the cervical vagus nerve37. Discomfort related to stimulation was typically managed by reducing the stimulation without discontinuing therapy. Clinical application of electrical stimulation to the vagus nerve with a variety of devices has been used in the U.S. since 1997, initially as an adjunctive treatment for patients with drug-refractory epilepsy, later for difficult-to-treat depression, and most recently for use in stroke patients to improve motor function when paired with physical rehabilitation37. Relative to this extensive prior clinical experience, no new risks or safety signals were observed in the RESET-RA trial.

The new integrated neuromodulation system used in the RESET-RA trial represents an important advancement in device design, as it uses a rechargeable battery and integrated electrodes, obviating the need to tunnel a lead wire from an implantable pulse generator, typically placed in the chest, to the cervical vagus nerve. This design eliminates the risk of lead breakage and chest-pocket infections seen with other systems. Nonimplanted devices could also mitigate these risks; however, to date, randomized controlled trials of transcutaneous stimulation targeting neuroimmune pathways have not demonstrated efficacy in RA38.

A limitation of this trial was the 3-month controlled phase, which was restricted in duration by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines to protect patients randomized to placebo from an extended period without treatment. In drug trials, peak ACR20 responses are typically observed by 3 months, that is, continued group-level improvement after 3 months is minimal21,22,23,24. In contrast, stimulation in arm 1 appears to take longer to reach peak therapeutic response. The response is consistent with clinical experience with vagus nerve stimulation for other indications, where some patients took longer to achieve threshold benefit37. The extended time to peak therapeutic response is likely influenced by modulation of innate neuroimmune pathways rather than by acute inhibition of discrete inflammatory pathways, the mechanism of most pharmaceutical interventions. This may explain why, despite a statistically significant difference in ACR20 response rates between arms at 3 months (meeting the primary efficacy end point), the effect size of 11.8% was smaller than the projected effect size of 25% and smaller than that typically reported in drug trials at 3 months21,22,23,24. During open-label, the therapeutic response to active stimulation increased between 3 and 6 months, as was first observed in the pilot study of this neuromodulation system12,14. In addition, the consistency of clinical outcomes across multiple visits through 12 months in the open-label period, together with a low rate of drug augmentation, supports the durability of the treatment effect. Demonstrating longer-term sustained reductions in disease activity (beyond short-term efficacy measured at 3 months) is clinically meaningful, as RA is a chronic disease that requires prolonged therapy. Caution should be exercised in interpreting the low rate of augmentation therapy, as observed disease activity after 3 months to 12 months was not paired against protocol-mandated decision-making to either advance or not advance therapy.

In conclusion, evidence from this large, pivotal, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial of an integrated neuromodulation system using an implantable device demonstrated significant sustained clinical benefits and high patient satisfaction with low rates of adverse events through 12 months of follow-up in a largely D2T, moderately-to-severely active RA population. Patients benefited from automatic delivery of 1 min of active treatment daily to achieve substantial improvement in their disease activity, resulting in a significant decrease in swollen and tender joints, and reduction in MRI-observed erosions without the use of b/tsDMARDs. Vagus nerve-mediated neuroimmune modulation offers a first-in-class nonpharmacologic therapeutic option for RA.

Methods

Trial design

The RESET-RA trial (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04539964, registered on 31 August 2020) was a pivotal, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial conducted at 41 sites across the U.S. based on study design considerations from the FDA previously used to approve therapeutic trials for RA39,40. Within 30 days of completing the baseline assessments performed at time of informed consent, all eligible patients who provided informed consent underwent an outpatient surgical procedure to implant the integrated vagus nerve stimulation device, followed by randomization (day 0) in a 1:1 ratio to either an active stimulation (arm 1) or a sham stimulation (arm 2) group. Randomization incorporated stratification for prior inadequate or lost response to a tsDMARD, exposure to ≥4 biological DMARDs with ≥2 mechanisms of action and RA disease severity at day 0. The randomization scheme was generated by the study biostatisticians and implemented centrally through Interactive Response Technology (IRT). End points were assessed at 3 months after randomization as change from baseline. Blinding was formally assessed using Bang’s blinding index41,42. Data collection used the Veeva System of Electronic Data Capture, with clinical sites directly entering data through a password-protected portal, with source documentation verification completed by clinical monitors. Data collection by Electronic Data Capture was compliant for data integrity, security and traceability through adherence to regulations like FDA 21 CFR Part 11 and ICH GCP, and global standards.

After the primary end point assessment at 3 months, all patients were eligible for open-label treatment with stimulation, and use of adjunctive pharmacological treatments were permitted at the discretion of the rheumatologist in consultation with the patient (‘augmented therapy’). Augmented therapy was defined as initiation of a b/tsDMARD, use of additional csDMARD(s), high-dose steroids or steroid injections in combination with continued active stimulation during open-label follow-up. Results are reported through 12 months. A detailed schematic of trial design and visits is provided in Extended Data Fig. 1. All data and results associated with the dataset are available in the ‘Results’ section and Supplementary Note.

Patients

All patients provided written informed consent using an institutional review board (IRB)-approved document. Patients were compensated with a nominal payment, approved by the IRB, for each completed visit. The study only reported sex as self-reported by the study participant.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible patients were adults (age = 22–75 years, inclusive) with moderately-to-severely active RA defined at baseline (day of informed consent) by the presence of >4 tender joints and >4 swollen joints of 28 joints, as assessed by a designated joint evaluator. Prior treatment with at least one csDMARD (for example, methotrexate) for a minimum of 12 weeks was required at a continuous and nonchanging dose for at least 4 weeks before consent. Patients were required to maintain this csDMARD dose throughout the double-blind, sham-controlled period. Patients were also required to have experienced an inadequate response or intolerance to at least one or more b/tsDMARDs before consent, with standard b/tsDMARD washout completed before the surgical procedure for device implantation. An elevated level of an acute phase reactant, such as serum C-reactive protein, was not required for eligibility. Exclusion criteria included history of vagotomy, partial or complete splenectomy, clinically significant cardiovascular disease or regular use of or dependency on nicotine products within the two years preceding study participation. Complete eligibility criteria are provided in the Supplementary Note—Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Enrollment and implantation procedure

Participants meeting final eligibility criteria and in whom the implantation procedure was attempted were considered enrolled (safety cohort). The implantation procedure occurred within 30 days of informed consent and took place in an operating room under general anesthesia. The Implant and Pod were placed on the left cervical vagus nerve by surgeons trained and experienced in procedures involving the implantation of vagus nerve stimulation devices. All surgeons performing the implant procedure had documented training before performing the first case. All enrolled and randomized patients were included in the ITT analysis.

Trial procedures

Stimulation therapy was delivered by a neuromodulation device comprised of an implant with an integrated, rechargeable battery approximately 2.5 cm in length. The implant was placed in a silicon positioning pod on the left cervical vagus nerve during an outpatient surgical procedure under general anesthesia (Fig. 2). The surgical procedure to implant the device has been previously described15. The entire system also included external devices for recharging and programming the implant. Stimulation parameters chosen for this study have been designed, translated and validated in 3 prior clinical studies12,13,16,43.

All patients, regardless of treatment assignment, completed the same stimulation titration protocol that occurred weekly over a period of 4 weeks. The device was titrated to an upper comfort level that did not exceed 2.5 mA. For treatment, a pulse train was delivered to the vagus nerve for 1 min once daily at 10 Hz (stimulation group), while patients randomized to sham stimulation always received 0 mA, regardless of the stimulation strength set by the blinded programmer. Stimulation was programmed to be delivered in the early morning hours, when patients would typically be asleep. Patients were instructed that feeling stimulation was not necessary to be receiving active treatment, and if stimulation was felt, the stimulation setting may not be at a therapeutic dose during the double-blind, sham-controlled period. Blinding to group assignment was maintained for patients, healthcare providers, investigators, joint evaluators and the sponsor until all patients completed assessments at 3 months and the database was locked for primary efficacy analysis. Because all patients crossed over to open-label follow-up before the study was unblinded, they repeated the initial titration protocol, as it was unknown whether they had been receiving stimulation or sham during the 3-month double-blind period.

End points

The primary end point was the difference in proportion of patients receiving stimulation versus sham who achieved an ACR20 response at the 3-month visit from baseline (day of consent). ACR20 response is a dichotomous composite end point indicating the proportion of patients that achieve at least 20% improvement in the number of both tender and swollen joints of a maximum of 28 joints and ≥3 of 5 additional measures—HAQ-DI score (scale 0 = mild disability to 3 = severe disability), patient global assessment of disease (0 = inactive to 10 = very active, patient pain (0 = no pain to 10 = worst), evaluator’s global assessment of disease (0 = inactive to 10 = very active) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein concentration (mg ml−1)17. Additional prespecified end points included DAS28-CRP good/moderate response according to the EULAR criteria, achievement of low disease activity (LDA) or remission by DAS28-CRP criteria (DAS28-CRP, score < 3.2 for LDA or remission) and LDA or remission by the CDAI (score <10 for LDA or remission). Additional outcomes were collected that were not the focus of this study and may be the topic of subsequent publications. Detailed descriptions of end points can be found in the Supplementary Note—Description of efficacy end points.

To objectively evaluate treatment effect on joint inflammation and erosions, a standardized, validated imaging method, using gadolinium contrast-enhanced MRI of the hand and wrist, was used. Images were obtained at the following timepoints: before the implant procedure, 3 months, and 6 months. The OMERACT RAMRIS was used to evaluate progression of bone erosions18. All images were assessed centrally by two independent radiologists blinded to treatment allocation, clinical information and the order in which the images were acquired to ensure objective and unbiased scoring. Prespecified analyses included the percentage of patients exhibiting progression in bone erosions (increase in score > 0.5 at 3 months compared to first MRI) among patients with a highly erosive phenotype (defined as synovitis score of 2 or more on any individual joint, at least four joints with a score of 1 or any joint with osteitis at baseline)25,44.

To evaluate reported satisfaction with the therapy, a participant satisfaction questionnaire, administered at 6 months, was comprised of five-point Likert rating scale and question on whether the participant would recommend the SetPoint System. An optional section was available for the participant to provide comments. This was an exploratory end point and there were no prespecified analyses.

Safety assessments

Adverse events and serious adverse events were tabulated and coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (version 23.1) and the incidence of events was tabulated based on system organ class and preferred term. All enrolled patients were analyzed for safety. Adverse events were evaluated by investigators for relatedness to the implant device, implantation procedure, charger, stimulation therapy or explantation procedure (if completed). Safety was also monitored by clinical laboratory tests, including complete blood count, measurement of vital signs, electrocardiogram and other safety assessments performed at baseline and scheduled visits.

Trial oversight

An investigational device exemption was approved by the FDA, and the trial was conducted in accordance with national and local regulations, the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocol was approved by an institutional review board at each participating site. All patients provided written informed consent before undergoing study-related activities. An independent data safety and monitoring committee oversaw the study conduct. The sponsor (SetPoint Medical) and a subset of authors designed the study. The data were collected by the investigators and their study teams. Data was analyzed by the sponsor’s biostatistician and interpreted by the sponsor and authors. All the authors reviewed and approved the paper and had access to the data. The authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol. Advarra served as the central IRB, with three sites using local IRBs.

Statistical analysis

Power calculations were performed solely for the primary end point. A sample size of 120 per study group would provide 91.6% power to detect a 25% difference in ACR20 response at 3 months, with one-sided α of 0.025, assuming response rates of 45% and 20% in the stimulation and sham groups, respectively. Patients who were enrolled and randomized were analyzed as ITT for the primary outcome.

Data analyses were performed as open-label populations at 6 months, 9 months and 12 months, with all patients receiving stimulation. These analyses were performed as an all-completers analysis (all patients who completed the specified follow-up visit) and a nonaugmented analysis (all patients who completed the visit without use of augmented therapy).

Binary responses, including the ACR20 response at 3 months, were analyzed with the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test using stratification factors based on prespecified criteria (prior inadequate or lost response to a tsDMARD, prior inadequate or lost response to ≥4 biological DMARDs with ≥2 mechanisms of action and RA disease severity defined as either <4 TJC28 or <4 SJC28 at day 0). The secondary efficacy end points that were continuous variables (change from baseline) were analyzed using mixed-effect model repeated measure statistics. Among the key secondary end points, multiplicity adjustment using Hochberg’s step-up procedure was performed to control the familywise type 1 error rate at a one-sided significance level of 0.025 (ref. 45).

Assessment of LDA or remission were evaluated by DAS28-CRP (score < 3.2) and CDAI (score < 10) as prespecified exploratory end points. The Bang’s blinding index and its associated 95% CIs were calculated for patients, investigators and joint evaluators (scale range = −1 to 1 with │scores│ < 0.3 considered as satisfactory blinding)41. All analyses were conducted with SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute).

Missing data

Given that the primary efficacy end point of ACR20 response was composed of seven components, missing data were handled as follows: if either tender-joint count or swollen-joint count were missing, or if ≥3 of 5 remaining ACR measures were missing, the participant was considered as a nonresponder. For binary secondary end points, participants with missing efficacy data, early withdrawals (before 3 months) or participants who received rescue treatment before 3 months were imputed as nonresponders. Rescue treatment was defined as any change in RA treatment made before 3 months for the reason of addressing worsening of RA symptoms by adding a b/tsDMARD, increasing the dose or adding a csDMARD, increasing the dose or adding a corticosteroid or a corticosteroid injection within 30 days of a study visit. For continuous end points, the change from baseline was set to missing at visits with missing postbaseline values, where data were imputed to missing, or for patients who received rescue treatment before 3 months.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Access to the clinical trial data in this paper can be requested from the corresponding author after one year from publication by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research. Data will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA).

Code availability

The use of custom code was not applicable in this paper.

References

Di Matteo, A., Bathon, J. M. & Emery, P. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 402, 2019–2033 (2023).

Fraenkel, L. et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 73, 924–939 (2021).

Evrengul, H. et al. Heart rate variability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 24, 198–202 (2004).

Baker, M. C., Nagy, D., Tamang, S., Horvath-Puho, E. & Sorensen, H. T. Vagotomy and the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: a Danish register-based study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 27, 106 (2025).

Koopman, F. A. et al. Autonomic dysfunction precedes development of rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective cohort study. eBioMedicine 6, 231–237 (2016).

Tracey, K. J. The inflammatory reflex. Nature 420, 853–859 (2002).

Tracey, K. J. Reflex control of immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 418–428 (2009).

Chavan, S. S., Pavlov, V. A. & Tracey, K. J. Mechanisms and therapeutic relevance of neuro-immune communication. Immunity 46, 927–942 (2017).

Olofsson, P. S., Rosas-Ballina, M., Levine, Y. A. & Tracey, K. J. Rethinking inflammation: neural circuits in the regulation of immunity. Immunol. Rev. 248, 188–204 (2012).

Pavlov, V. A. & Tracey, K. J. Bioelectronic medicine: preclinical insights and clinical advances. Neuron 110, 3627–3644 (2022).

Dalli, J., Colas, R. A., Arnardottir, H. & Serhan, C. N. Vagal regulation of group 3 innate lymphoid cells and the immunoresolvent PCTR1 controls infection resolution. Immunity 46, 92–105 (2017).

Genovese, M. C. et al. Safety and efficacy of neurostimulation with a miniaturised vagus nerve stimulation device in patients with multidrug-refractory rheumatoid arthritis: a two-stage multicentre, randomised pilot study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2, e527–e538 (2020).

Koopman, F. A. et al. Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 8284–8289 (2016).

Gaylis, N. B. et al. Neuroimmune modulation for drug-refractory rheumatoid arthritis: long-term safety and efficacy in patients enrolled in a pilot vagus nerve stimulation study. Rheumatol. Ther. 12, 1125–1136 (2025).

Peterson, D. et al. Clinical safety and feasibility of a novel implantable neuroimmune modulation device for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: initial results from the randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled RESET-RA study. Bioelectron. Med. 10, 8 (2024).

Levine, Y. A., Faltys, M. & Chernoff, D. Harnessing the inflammatory reflex for the treatment of inflammation-mediated diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 10, a034330 (2020).

Felson, D. T. et al. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 38, 727–735 (1995).

Ostergaard, M. et al. The OMERACT rheumatoid arthritis magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scoring system: updated recommendations by the OMERACT MRI in arthritis working group. J. Rheumatol. 44, 1706–1712 (2017).

Hofman, Z. L. M. et al. Difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis: what have we learned and what do we still need to learn?. Rheumatology (Oxford) 64, 65–73 (2025).

Kay, J. et al. Clinical disease activity and acute phase reactant levels are discordant among patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: acute phase reactant levels contribute separately to predicting outcome at one year. Arthritis Res. Ther. 16, R40 (2014).

Genovese, M. C. et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis refractory to biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-BEYOND): a double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 391, 2513–2524 (2018).

Burmester, G. R. et al. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 381, 451–460 (2013).

Genovese, M. C. et al. Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor α inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1114–1123 (2005).

Genovese, M. C. et al. Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 1243–1252 (2016).

Gandjbakhch, F. et al. Determining a magnetic resonance imaging inflammatory activity acceptable state without subsequent radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis: results from a followup MRI study of 254 patients in clinical remission or low disease activity. J. Rheumatol. 41, 398–406 (2014).

Conaghan, P. G. et al. Very early MRI responses to therapy as a predictor of later radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 21, 214 (2019).

Schett, G. & Gravallese, E. Bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis: mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 8, 656–664 (2012).

Bajayo, A. et al. Skeletal parasympathetic innervation communicates central IL-1 signals regulating bone mass accrual. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 15455–15460 (2012).

Tamimi, A. et al. Could vagus nerve stimulation influence bone remodeling?. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 21, 255–262 (2021).

Levine, Y. A. et al. Neurostimulation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway ameliorates disease in rat collagen-induced arthritis. PLoS ONE 9, e104530 (2014).

Elefteriou, F. Impact of the autonomic nervous system on the skeleton. Physiol. Rev. 98, 1083–1112 (2018).

Serhan, C. N., de la Rosa, X. & Jouvene, C. Novel mediators and mechanisms in the resolution of infectious inflammation: evidence for vagus regulation. J. Intern. Med. 286, 240–258 (2019).

Ali, M., Yang, F., Plachokova, A. S., Jansen, J. A. & Walboomers, X. F. Application of specialized pro-resolving mediators in periodontitis and peri-implantitis: a review. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 129, e12759 (2021).

Bassi, G. S. et al. Modulation of experimental arthritis by vagal sensory and central brain stimulation. Brain Behav. Immun. 64, 330–343 (2017).

Rosch, G., Zaucke, F. & Jenei-Lanzl, Z. Autonomic nervous regulation of cellular processes during subchondral bone remodeling in osteoarthritis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 325, C365–C384 (2023).

Frisell, T. et al. Safety of biological and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis as used in clinical practice: results from the ARTIS programme. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 82, 601–610 (2023).

Toffa, D. H., Touma, L., El Meskine, T., Bouthillier, A. & Nguyen, D. K. Learnings from 30 years of reported efficacy and safety of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for epilepsy treatment: a critical review. Seizure 83, 104–123 (2020).

Baker, M. C. et al. A randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled, clinical trial of auricular vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 75, 2107–2115 (2023).

Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Center for Devices and Radiological Health & Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Clinical Development Programs for Drugs, Devices, and Biological Products for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/clinical-development-programs-drugs-devices-and-biological-products-treatment-rheumatoid-arthritis (1999).

Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Center for Devices and Radiological Health & Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Developing Drug Products for Treatment. Docket Number FDA-2013-D-0571. www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/rheumatoid-arthritis-developing-drug-products-treatment (2013).

Munoz Laguna, J., Lee, H., Poltavskiy, E., Kim, J. & Bang, H. Participant’s treatment guesses and adverse events in back pain trials: Nocebo in action?. Clin. Trials 21, 759–762 (2024).

Bang, H., Flaherty, S. P., Kolahi, J. & Park, J. Blinding assessment in clinical trials: a review of statistical methods and a proposal of blinding assessment protocol. Clin. Res. Regul. Aff. 27, 42–51 (2010).

D'Haens, G. et al. Neuroimmune modulation through vagus nerve stimulation reduces inflammatory activity in Crohn’s disease patients: a prospective open-label study. J. Crohns Colitis 17, 1897–1909 (2023).

Baker, J. F., Conaghan, P. G., Emery, P., Baker, D. G. & Ostergaard, M. Validity of early MRI structural damage end points and potential impact on clinical trial design in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 1114–1119 (2016).

Hochberg, Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 75, 800–802 (1988).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients and their families who were willing to participate in this trial. We thank the medical and research staff at the study centers for their support in conducting the trial. We thank Spire Sciences for performing the MRI image analyses. We acknowledge the support and collaboration of the broader clinical teams, coordinators and technical personnel, whose efforts ensured the integrity and quality of the study. The RESET-RA trial was sponsored by SetPoint Medical.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L.E., A.A.D., Y.A.L., J.R.C. and D.C. conceptualized the study, designed the methodology, conducted the formal analysis and wrote the original draft of the paper. J.R.P.T., A.R.C., E.J.B., J.P.J., P.B.W., G.J.V., N.B.G., G.K.W.L., L.A.P., D.J.R., G.P.P.-P., S.N.N., M.A.C., M.K., E.C.L., J.A.P., G.R.P., J.R.P., T.S., A.K.S., V.V. and R.M.R. performed the investigation. All authors interpreted the data and contributed to reviewing and editing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.R.P.T. reports consulting, grant/research support and/or honoraria (including speakers bureau, symposia and expert witness) from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, IGM Biosciences, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and UCB; and consulting from SetPoint Medical. E.J.B. reports grant/research support from SetPoint Medical. J.P.J. reports consultancy and grant/research support from Janssen and SetPoint Medical. P.B.W. reports consulting, advisory roles, speaker honoraria and/or grant/research support from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis and UCB. G.J.V. reports advisory, consultancy, grant/research support and/or speaker honoraria from AbbVie, Alexion, Amgen, Artiva Biotherapeutics, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Centocor, Eli Lilly, Esaote, Exagen, Genentech, Gilead, Global Healthy Living Foundation, Horizon, Image Analysis Group, Janssen, Mallinckrodt, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Pharmacia, Radius, Regeneron, Sandoz, Sanofi, Takeda, Theramex, UCB and Vividion Therapeutics. N.B.G. reports research funding from AbbVie, Acelyrn, Alumis, Amgen, Aqtual, Artiva, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Horizon, IGM Biosciences, Moonlake, Novartis, Sanofi, SetPoint Medical, Takeda and UCB; is an officer/board member of AB Solutions; and an advisor/review panel member for Inmedix. G.K.W.L. reports advisory roles, consultancy, speaker honoraria and/or research support from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, SetPoint Medical and UCB. L.A.P. reports research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Horizon, Janssen, SetPoint Medical and UCB. D.J.R. reports research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson and UCB. M.K. reports research funding from Janssen, Novartis and SetPoint Medical; membership on advisory boards for Janssen and Novartis; and royalties from Springer Publications. J.R.P. reports consulting, advisory roles, research funding, intellectual property/patents and/or speaker honoraria from Amgen, Arthrosi, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, SOBI and UCB. T.S. reports consulting, research funding and/or stock options from AbbVie, Amgen, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Takeda and UCB. V.V. reports research funding from AstraZeneca, Scipher Medicine and SetPoint Medical. Y.A.L. and D.C. are employees of and hold equity/stock options and intellectual property/patents in SetPoint Medical. M.L.E. and A.A.D. are employees of and hold equity/stock options in SetPoint Medical. J.R.C. reports consulting and/or research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Bendcare, Bristol Myers Squibb, Corrona, Crescendo, Eli Lilly, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Moderna, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi and UCB; and is an officer/board member of FASTER. R.M.R. reports consulting and/or research funding from Neuropace, Medtronic, Inbrain and SetPoint Medical. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Rushna Ali, Sejong Bae and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jerome Staal, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Schematic of study design.

Adapted from ref. 15, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Note and Supplementary Tables 1–24.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tesser, J.R.P., Crowley, A.R., Box, E.J. et al. Vagus nerve-mediated neuroimmune modulation for rheumatoid arthritis: a pivotal randomized controlled trial. Nat Med 32, 369–378 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04114-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04114-7