Abstract

Sleep deprivation rapidly disrupts cognitive function and in the long term contributes to neurological disease. Why sleep deprivation has such profound effects on cognition is not well understood. Here we use simultaneous fast fMRI–EEG to test how sleep deprivation modulates cognitive, neural and fluid dynamics in the human brain. We demonstrate that attentional failures during wakefulness after sleep deprivation are tightly orchestrated in a series of brain–body changes, including neuronal shifts, pupil constriction and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow pulsations, pointing to a coupled system of fluid dynamics and neuromodulatory state. CSF flow and hemodynamics are coupled to attentional function within the awake state, with CSF pulsations following attentional impairment. The timing of these dynamics is consistent with a vascular mechanism regulated by neuromodulatory state. The attentional costs of sleep deprivation may thus reflect an irrepressible need for rest periods driven by a central neuromodulatory system that regulates both neuronal and fluid physiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Sleep plays a fundamental role in maintaining brain health and preserving cognitive performance. Despite the intense biological need for sleep, sleep deprivation is a major facet of modern life. A single night of lost sleep can cause noticeable cognitive impairment, including attentional failures, in which individuals fail to properly react to an easily detected external stimulus1,2,3. The behavioral deficits caused by sleep deprivation carry a major cost for organismal survival; for example, a momentary lapse in attention while driving a car can have life-threatening outcomes4. Sleep deprivation reliably induces attentional failures despite this cost, suggesting that these deficits reflect an unavoidable need of the brain for sleep. However, the neural basis of sleep deprivation-induced attentional failures is not yet well understood.

Acute sleep deprivation has widespread effects on both local and global aspects of neurophysiology. Large fluctuations in blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) signals appear across various networks following sleep deprivation5,6, and large-scale fMRI signals are linked to altered electrophysiology, eyelid closures7,8,9 and arousal state, suggesting global changes in brain activity and vigilance. Attentional lapses after sleep deprivation are linked to reduced activity within the thalamus and cognitive control areas, suggesting a failure to engage large-scale network activity10,11. At the scale of local cortical areas, attentional failures are linked to sleep-like low-frequency waves in isolated cortical patches in rats12. Intriguingly, transient occurrences of sleep-like slow wave activity also predict attentional lapses in humans13,14. Together, these findings have shown that attentional deficits following sleep deprivation are linked to brain-wide hemodynamic changes and low-frequency neural oscillations. The neural basis of these attentional failures is not well understood. One possibility is that attentional lapses correspond to a brief state in which the brain transiently carries out a sleep-dependent function that is incompatible with waking behavior.

Sleep serves many functional purposes, and sleep neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that sleep is linked to not only neuronal but also vascular and fluid changes in the brain. Global low-frequency (0.01–0.1 Hz) hemodynamic waves appear in non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, and these vascular fluctuations in turn drive pulsatile waves of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow15,16. Sleep deprivation increases the amplitude of the global BOLD signal6, and sleep deprivation modulates CSF pulsatility17, suggesting that the effects of sleep deprivation could be accompanied by altered CSF dynamics. However, precisely how attentional deficits are linked to hemodynamics and CSF flow is not yet clear.

We conducted a within-subject total sleep deprivation study in healthy human participants to investigate whether sleep deprivation and its associated attentional deficits are linked to altered brain fluid dynamics. We used multimodal fast fMRI, electroencephalography (EEG), behavioral assessments and pupillometry to track multiple aspects of neurophysiological dynamics simultaneously. We discovered that CSF flow is coupled to behavioral deficits during wakefulness after sleep deprivation. Notably, we found that attentional failures during wakefulness are marked by a brain- and body-wide state change that underlies both behavioral deficits and pulsatile fluid flow. Specifically, the moments where attention fails occur just before the initiation of a global hemodynamic event and a large-scale outward pulse of CSF flow, followed by subsequent reversal of these dynamics.

Results

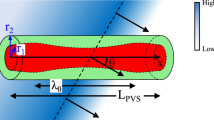

To investigate how sleep deprivation modulates neural activity and vascular and CSF dynamics, we performed a simultaneous EEG and fast fMRI experiment in 26 human participants. To enable within-subject comparisons, each participant was scanned twice: once after a night of regular sleep (well-rested) and once after one night of total sleep deprivation, which was continuously supervised in the laboratory (Fig. 1a). We performed simultaneous EEG–fMRI scans with pupillometry in the morning. During the scans, participants performed up to four runs of a sustained attention task, the psychomotor vigilance test (PVT; Fig. 1b), followed by an eyes-closed resting-state run. CSF flow is bidirectional and includes pulsations of both inflow (inward/dorsal) and outflow (outward/ventral). This fast fMRI protocol enabled us to simultaneously measure cortical hemodynamic BOLD signals and CSF inflow in the fourth ventricle (Fig. 1c).

a, For the sleep-deprived visit, participants arrived at the laboratory at 7:00 p.m. before the sleep-deprived night and were monitored continuously during the night. For the well-rested visit, participants arrived between 8:30 and 9:00 a.m. the day of the scan. For both visits, scans were performed around 10:00 a.m. in the morning. Scans included up to four PVT runs followed by a 25-min resting-state run. b, For the PVT attention task, each run used either the auditory PVT (aPVT; detecting a beep) or the visual PVT (vPVT; detecting a luminance-matched visual stimulus) with 5 to 10 s interstimulus interval (ISI). c, Left, example fMRI acquisition volume position (green box) for simultaneous measurement of BOLD and CSF flow. The volume intersects the fourth ventricle to enable inward CSF flow detection. Yellow marks the cortical segmentation, and purple indicates the flow measurement region of interest (ROI). The image was masked to delete identifiers. Right, example placement of a CSF ROI (magenta) in the fourth ventricle in one representative participant. d, CSF time series from the same participant during wakefulness showing that sleep deprivation causes large CSF waves during wakefulness, whereas the well-rested condition shows smaller CSF flow. e, Sleep deprivation increased low-frequency (0.01–0.1 Hz) CSF power during wakefulness (wake segments: n = 486 in well-rested, n = 205 in sleep-deprived; N1 segments: n = 179 in well-rested, n = 59 in sleep-deprived; N2 segments: n = 57 in well-rested, n = 40 in sleep-deprived; the black bar indicates P = 0.0004; two-tailed segment-level permutation test with a Bonferroni correction) to a magnitude similar to N1 and N2 sleep. Sleep segments are from the same participants in the final resting-state scan. Power spectral density (PSD) was calculated on CSF signal in resting-state runs. Data are presented as mean values ± s.e. (standard error across segments). f, Paired analysis of EEG low-frequency power (slow wave activity: 0.5–4 Hz) in resting-state wakefulness showing increased power after sleep deprivation (n = 18 participants with artifact-free wakefulness at both sessions; two-tailed paired t-test: t17 = –2.37, P = 0.029). g, Paired analysis of gray matter BOLD low-frequency power in resting-state wakefulness showing increased power after sleep deprivation (n = 18 participants with artifact-free wakefulness at both sessions; two-tailed paired t-test: t17 = –3.23, P = 0.048). h, Paired analysis of CSF low-frequency power in resting-state wakefulness showing increased power after sleep deprivation (n = 18 participants with artifact-free wakefulness at both sessions; two-tailed paired t-test: t17 = –3.25, P = 0.005).

Sleep deprivation causes sleep-like hemodynamics and pulsatile CSF flow to intrude into wakefulness

We first investigated whether sleep deprivation altered the dynamics of CSF flow in resting-state scans that included awake and sleeping periods (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Consistent with previous studies, the CSF inflow signal during well-rested wakefulness exhibited a small-amplitude rhythm synchronized to respiration18,19, in contrast to NREM sleep where CSF exhibits large ~0.05 Hz waves16. However, visual inspection clearly showed that the CSF signal during wakefulness after sleep deprivation also exhibited large-amplitude low-frequency waves, resembling NREM sleep (Fig. 1d). We analyzed this CSF signal across sleep stages in participants who had at least 60 s of continuous wakefulness during the resting-state run (N = 22, excluding segments with high motion; framewise displacement > 0.55 mm) and found a 4.7 dB increase in the CSF signal peaking at 0.04 Hz in sleep-deprived wakefulness (Fig. 1e,h). Remarkably, the CSF power in sleep-deprived wakefulness reached levels similar to the CSF power during typical N2 sleep (0.01–0.1 Hz power in sleep-deprived wake: 24.50 dB, 95% confidence interval = [24.46, 24.55]; rested N2: 24.80 dB, 95% confidence interval = [23.95, 25.59]). These session-dependent increases in CSF flow were not driven by motion artifacts (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

Prior work has shown that total overnight sleep deprivation increases BOLD fluctuations6 and low-frequency EEG signals20,21, both of which could modulate CSF flow, so we next examined these two factors in this cohort. To assess the effect of sleep deprivation on neural signals, we compared the levels of EEG slow wave activity (0.5–4 Hz), a well-recognized indicator of sleep pressure22,23,24, and found that sleep deprivation induced an increase in EEG slow wave activity (P = 0.029, paired t-test; Fig. 1f), as expected. Hemodynamics are the primary driver of CSF flow, as changes in blood vessels can mechanically drive CSF flow16,25,26,27, and we found that sleep deprivation also induced a significant increase in low-frequency (0.01–0.1 Hz) cortical gray matter BOLD power (P = 0.0048, paired t-test; Fig. 1g), and these effects were not driven by motion artifacts (Extended Data Fig. 1b). These results demonstrate that sleep deprivation causes low-frequency CSF flow pulsations, increased EEG slow wave activity and hemodynamic waves that appear during wakefulness, with changes in the same direction as the dynamics typically seen during N1 or N2 sleep.

Hemodynamic waves and pulsatile CSF flow occur during epochs with worse attentional task performance

Because large-scale CSF waves typically occur during NREM sleep, a state in which attention is suppressed, we investigated whether the CSF waves during well-rested and sleep-deprived wakefulness were associated with any attentional deficits. As expected2,10,28,29,30, sleep deprivation caused an increase in the mean reaction time (Fig. 2a) and the omission (missed response) rate (Fig. 2b) in the PVT task. Despite participants being awake with eyes open, we observed that attentional lapses (reaction time > 500 ms) and omissions tended to coincide with high-amplitude CSF flow (Fig. 2c). To quantify this behavior–CSF relationship, we tested whether lapses (reaction time > 500 ms) and omissions were linked to CSF power, analyzing data in 60-s segments during confirmed wakefulness (EEG and no eyelid closures >1 s). We found that worse attentional performance was linked to increased low-frequency (0.01–0.1 Hz) CSF power: segments with attentional lapses and segments with omissions exhibited significantly higher CSF flow power than segments without lapses (Fig. 2d). This effect remained significant when controlling for motion (repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA): F2,50 = 2.46, P > 0.05 for motion). These results demonstrated that larger low-frequency CSF flow pulsations are associated with attentional failures during wakefulness. We hypothesized that this CSF dynamic would be associated with BOLD signal amplitude and indeed found that worse attentional performance was also linked to increased low-frequency (0.01–0.1 Hz) gray matter BOLD power (Fig. 2e).

a, Reaction times after sleep deprivation showed a higher mean and a longer tail, indicating more behavioral lapses (N = 26 participants; shading represents standard error across participants; z = –25.08, P < 0.0001; data were analyzed by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test). b, Omission rate increased after sleep deprivation (N = 26 participants, t25 = –7.00, P = 2.43 × 10−6; data were analyzed by paired two-tailed t-test). c, CSF flow and reaction time fluctuations during one example run, showing higher flow when reaction time slows down. d, Low-frequency (0.01–0.1 Hz) CSF power within nonoverlapping 60 s segments, categorized into three different states: high attention (all reaction times below 500 ms), low attention (at least one reaction time > 500 ms) and omissions (at least one omission). Higher CSF power appears in lower attentional states (two-tailed repeated measures ANOVA and a Tukey post hoc test; F2,50 = 62.04, P = 5.49 × 10−5 for main effect, N = 26 participants). e, Low-frequency (0.01–0.1 Hz) gray matter BOLD power within nonoverlapping 60-s segments, following the same analysis as in d. Higher gray matter BOLD power appears in lower attentional states (two-tailed repeated measures ANOVA and a Tukey post hoc test; F2,50 = 24.82, P < 0.0001 for main effect, N = 26 participants). Box plots show the mean (center), the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers indicate minimum to maximum.

What process could result in joint changes in CSF flow, hemodynamics and attentional function? Ascending neuromodulation, such as noradrenergic input from the locus coeruleus, modulates attentional function31,32 and also acts directly on the vasculature33, making this a candidate mechanism for modulating both attention and CSF flow. Neuromodulatory tone and locus coeruleus firing is correlated with pupil diameter34, and sleep deprivation is well known to modulate pupil diameter, with smaller diameter indicating a low arousal state and decreased attentional function31,35,36. We investigated whether pupil diameter was linked to hemodynamics and CSF flow on faster timescales. We found that pupil diameter was significantly correlated with CSF flow: pupil constriction was linked to outward CSF signals, and pupil dilation was linked to subsequent inward CSF signals, with CSF flow following the pupil by 4.75 s (Fig. 3a,b,f). This correlation was also significant when we tested drowsy segments from rested wakefulness, demonstrating that this pupil–CSF coupling is present across states (Extended Data Fig. 2). However, the pupil–CSF correlation was significantly higher after sleep deprivation (Extended Data Fig. 2), suggesting that sleep deprivation drives a pupil-locked fluctuation in CSF flow. Consistent with this, we also observed that CSF flow peaks were locked to drops in attentional performance: both reaction time and the rate of omissions increased before CSF peaks (Fig. 3c,d). These patterns were also evident at the individual participant level (Extended Data Fig. 3a–h).

a, Spontaneous pupil constriction and dilation is time locked to peaks of CSF flow. Black bars indicate significant changes in z-scored pupil diameter compared to baseline (P < 0.05; two-tailed t-test, baseline = [–30, –28] s, Bonferroni corrected). Data are presented as mean values ± s.e.; AU, arbitrary units. b, Cross-correlation between pupil diameter and CSF showing a strong correlation (maximal r = 0.25 at lag –4.75 s; n = 400 segments, 23 participants). c, During periods with pupil constriction, reaction times also showed significant increases compared to baseline (stars mark segments with P < 0.05; data were analyzed by two-tailed t-test, Bonferroni corrected). d, Omission rate during task showing a significant increase during pupil constriction and significant decrease during pupil dilation (stars mark segments with P < 0.05; two-tailed t-test relative to baseline, Bonferroni corrected). e, Significant biphasic changes in cortical BOLD activity are locked to CSF peaks (P < 0.05; two-tailed t-test relative to baseline, Bonferroni corrected). f, Mean CSF signal. g, To estimate the impulse response function (IRF) linking pupil size changes to BOLD and CSF activity, we convolved pupil diameter traces from each segment with a series of IRFs. Estimated IRF of the cortical BOLD signal to the pupil diameter shows a time to peak at 8 s. Cross-correlation between pupil diameter and BOLD showed a strong correlation (maximal r = 0.34 at lag –1.25 s; n = 400 segments, 23 participants). h, Predicting CSF flow with no additional parameter fitting, assuming that the derivative of the pupil-locked BOLD fluctuations drives CSF flow, shows significant prediction of the true CSF signals (zero lag r = 0.26; n = 400 segments). Data are presented as mean values ± s.e. (standard error across segments). Participant-level means are provided in Extended Data Fig. 3. The exact P values are in Supplementary Table 1.

In each case, although CSF flow was locked to behavior and the pupil, it lagged these measures in time, which could reflect a vascular mechanism that introduces a time delay. Furthermore, although pupil diameter is consistently correlated with noradrenergic tone, it is also correlated with several other modulators37,38. To test whether pupil–CSF coupling reflected a pupil-locked modulation of cerebrovascular fluctuations, which could be expected from noradrenergic-driven vasoconstriction and would drive a delayed CSF response39, we examined the global cortical BOLD signal and found an anticorrelation with the pupil (Fig. 3e). We calculated the best-fit impulse response linking the pupil to the global BOLD signal and found a negative impulse response with a peak delay of 8 s (Fig. 3g), consistent with pupil-linked vasoconstriction. To test whether this mechanism in turn predicted CSF flow, we convolved the pupil signal with its impulse response and calculated the expected CSF flow driven by this vascular effect, with no additional parameter fitting16. We found that the convolved pupil signal yielded a significant prediction of CSF activity (Fig. 3h; zero lag R = 0.26, maximal R = 0.3 at lag –1.25 s), indicating that the timing of the pupil–CSF coupling could be explained by a vascular intermediary.

Attentional failures are time locked to neural, hemodynamic, systemic and CSF flow events

Having found that hemodynamic waves and CSF flow pulsations were highest in epochs with omissions, we next examined the precise dynamics occurring at the moment of omissions. Because CSF flow pulsations increase during NREM sleep, we carefully excluded omissions due to NREM sleep to confirm whether these flow changes appeared during wakefulness (EEG verified and excluding segments with eye closures >1 s). We found a strong coupling between behavior and CSF flow during sleep-deprived wakefulness: omissions were locked to an outward wave and then an inward wave of CSF flow in the fourth ventricle (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Figs. 4a and 5a,g). Although few omissions occurred in the well-rested state, when they did appear, they showed similar CSF flow coupling, demonstrating that a complete attentional failure even when rested can engage a similar mechanism (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). The cortical gray matter BOLD signal exhibited a matched biphasic pattern, consistent with vascular drive of outward and then inward CSF flow (Extended Data Figs. 4b and 5c,i). However, our imaging protocol was only able to directly measure CSF inflow (inward to the brain) due to the placement of the acquisition volume (Fig. 1c), whereas drops in CSF signal could in theory represent either outflow or simply no flow. We therefore conducted a second study in an additional ten sleep-restricted participants with a new imaging protocol that measured bidirectional flow (Extended Data Fig. 6a) to test whether this pattern specifically signaled CSF outflow before inflow. This acquisition method allowed simultaneous measurement of inflow and outflow but did not allow measurement of gray matter BOLD signals. We confirmed that omissions were locked to a pulse of CSF flowing outward out of the brain, beginning at the time of the missed stimulus, followed by a pulse flowing inward into the brain (Extended Data Fig. 6b). These results replicated the finding of coupled attentional function and CSF flow pulsations in an independent cohort, with a biphasic profile of outward flow at omissions, followed by inward flow.

a, Awake omission trials are locked to a biphasic change in CSF flow, with an outward trough followed by an inward peak. Time zero marks stimulus onset; omission occurs within the following seconds. Data are presented as mean values ± s.e. b, Omission trials are locked to a broadband drop in EEG power, including decreased alpha–beta (10–25 Hz) EEG power, and then an increase in slow wave activity (SWA; 0.5–4 Hz) and alpha–beta power. The biphasic alpha–beta power change is widespread with centro-occipital predominance, whereas the slow wave activity increase has occipital and frontal predominance. The spectrogram is normalized within frequency; black bars indicate a significant change in broadband power (0.5–30 Hz) compared to baseline. c, The aperiodic component of the EEG was subtracted to display oscillation-specific changes. The alpha–beta and slow wave activity effects were still present (statistics are provided in Extended Data Fig. 8). d, Pupil diameter showed a biphasic change at omissions, with a significant constriction during the omission trial followed by dilation after trial onset (9–12 s). e, Heart rate dropped during omissions and subsequently increased. f, Respiratory rate drop at omissions and subsequent increase. Black bars with stars indicate significant changes from baseline (n = 364 trials, 26 participants). Data are presented as mean values ± s.e. (standard error across segments). Stars indicate P < 0.05; two-tailed t-test with a Bonferroni correction over time, baseline = [–20, –10] s. Exact P values are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

During NREM sleep, CSF flow is coupled to neural slow wave activity16,40, and local slow waves can also increase after sleep deprivation12. We therefore analyzed the EEG spectrogram to investigate which neural dynamics might be linked to these omission-locked CSF waves (example spectrogram in Extended Data Fig. 7a). We found that omissions (n = 364 trials, 26 participants) were accompanied by EEG alterations across multiple frequency bands and across different electrodes, with a drop in broadband EEG power, particularly pronounced in the alpha–beta (10–25 Hz) range, followed shortly by a subsequent increase in power (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Figs. 5b,h and 8). In addition to this broadband change, the oscillation-only component of the spectrogram (calculated by subtracting the aperiodic component41,42,43,44) also demonstrated significant clusters at slow and alpha–beta frequencies, with a broad spatial distribution (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 8b). The global distribution of the EEG power change suggested an altered global arousal state. Overall, this broadband power reduction and steepening spectral slope pointed to a spatially distributed change in electrophysiological dynamics.

What type of neuronal event might these EEG spectral shifts reflect? The relatively broadband and spatially global (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Figs. 5b and 8) nature of these EEG changes suggested that they might reflect a transient change in cortical excitability45, perhaps mediated by central neuromodulatory state, as suggested by the pupil coupling (Fig. 3g,h). In addition, autonomic state changes and systemic oscillations can drive CSF flow46,47,48, consistent with the idea that large-scale neuromodulatory changes could contribute to both the attentional failures and CSF dynamics. We therefore tested whether a sequence of events could be locked to the CSF flow: a drop in attentional state followed by recovery of attention. Consistent with this, pupil dilation was biphasically coupled to CSF flow: the pupil was constricted during the omission, corresponding to a low arousal state and outward CSF flow, and then subsequently dilated (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 3c,d), with CSF subsequently flowing inward (Fig. 4a). Because neuromodulatory state also has systemic effects49, we further examined systemic physiological recordings, including changes in respiratory rate and volume, heart rate and peripheral vascular volume, reflecting activity of the autonomic nervous system. We found that all systemic measures were significantly locked to the omission (Fig. 4d–f and Extended Data Figs. 3d–f, 4c,d and 5e,f,k,l). These results demonstrate that attentional failures during wakefulness were coupled to a brain- and body-wide integrated state shift, manifesting as a transient behavioral deficit, electrophysiological markers of distinct neuronal state, pupil constriction and hemodynamic and CSF flow waves.

Neurovascular and CSF pulsation events are differentially modulated by loss and recovery of attention

These results clearly identified widespread behavioral, neuronal and arousal dynamics that were locked to CSF pulsatile flow during sleep-deprived wakefulness. However, attentional failures are typically brief during wakefulness, with a spike in arousal rapidly following an omission. Furthermore, the neurovascular, pupil and CSF dynamics showed biphasic patterns, with both signal drops and increases around attentional failures. Due to this biphasic pattern, each physiological change could potentially be explained by two different possibilities: either it was specifically linked to drops in arousal (at the onset of attentional failures) or it was locked to increases in arousal (at the recovery of behavior). We therefore designed an analysis of behavioral responses to separate the neurophysiological dynamics linked to the drop, versus recovery, of attention. We categorized behavioral omissions into three types: ‘Type A’, where the omission trial was preceded and followed by a valid response, ‘Type B’, the first of at least three consecutive omissions, and ‘Type C’, the last omission of a consecutive series (Fig. 5a). As described above, wakefulness during all omissions was verified both through EEG scoring and eye tracking.

a, Omissions during wakefulness were categorized as isolated (Type A), onset of sustained low attention (Type B) and end of sustained low attention (Type C). Schematic made with BioRender.com. b, Type A, isolated omission trials (n = 127 trials, 26 participants), were locked to a decrease in broadband EEG power and then increased power at attention recovery in the next trial. CSF showed a significant decrease followed by a significant increase. Respiratory rate and heart rate both showed significant changes from baseline after trial onset. c, Type B, first omission of the series, signifies the onset of a sustained low attentional state (n = 61 trials, 20 participants). CSF signal, respiratory rate and heart rate all decrease significantly (P < 0.05, paired t-test across segments and time bins, Bonferroni corrected). The black arrow marks the onset time of CSF signal drop, at 0.5 s. d, Type C, last omission of the series, followed by increased attentional state (n = 57 trials, 20 participants). The EEG shows heightened slow wave activity during the omission and subsequent increase in alpha–beta power at the recovery of attention. CSF signal, respiratory rate and heart rate all increase significantly (P < 0.05; paired t-test relative to baseline, Bonferroni corrected). The black arrow marks the onset time of the CSF signal increase, at 9.5 s (that is, on average 1 s after behavior recovery). For data in b–d, black bars indicate significant (P < 0.05, paired two-tailed t-test, Bonferroni corrected) changes from baseline ([–10, –5] s). Gray regions indicate the average timing of trials where no behavioral responses were recorded for each omission type. Blue circles indicate average timing of valid responses before or after each omission type. Red crosses indicate average timing of the omission trial onset. Data are presented as mean values ± s.e. (standard error across segments). Participant-level averages are provided in Extended Data Fig. 9. The exact P values are in Supplementary Table 1.

To determine whether CSF pulsations were linked to attention drops or attention recovery, we compared Type B (attention drop) and Type C (attention recovery) trials. This analysis identified two separable patterns: neural, CSF and systemic signals showed opposing changes locked to Type B and C omissions (Fig. 5b–d and Extended Data Fig. 9a). The loss of attentional focus in Type B omissions was linked to a decrease in EEG alpha–beta power and expulsion of CSF, whereas regaining of attentional focus in Type C omissions co-occurred with an increase in EEG broadband power and inward flow of CSF, and the systemic arousal indicators followed the same pattern (Fig. 5c,d). The behavioral changes occurred before the initiation of the CSF flow changes (that is, the temporal derivative; Extended Data Fig. 9b), indicating that the behavioral events were associated with a subsequent reversal of flow direction. These results demonstrated that CSF flow occurs in a specific sequence of events: during an attentional failure, EEG power drops in concert with body-wide signatures of low arousal and subsequently a outward pulse of CSF flow. This pattern inverts at recovery of arousal, with CSF returning inward after attention improves, again with a time delay consistent with vascular-mediated CSF flow.

To calculate the relative timing of these effects, we estimated the onset times for the changes in behavior, EEG, BOLD and CSF flow. We identified the onset time of CSF decrease for Type A and B omissions and the onset time of CSF increase for Type C omissions (the time when CSF signal reached 10% of the minimum or maximum amplitude compared to pretrial baseline ([–3, 0] s)). This analysis showed that CSF signals began to decrease 0.5–2.5 s after trial onset that would subsequently result in attentional failure (Type A and Type B), peaking at 6.7–8.2 s. When attention recovered (after Type C), the CSF signal increase began at 1 s after behavioral recovery onset, peaking at 6.2 s. This timing pattern was consistent with the pupil-locked function in Fig. 3, aligning with an attention-locked modulation of the cerebrovasculature unfolding over several seconds. The long delay of the CSF peak may thus reflect the effect of vascular changes that followed attention failures. The timing of these relationships was therefore consistent with an integrated neuromodulatory mechanism that regulates attentional state, vascular physiology and CSF dynamics.

Discussion

Here, we found that attentional failures after sleep deprivation are locked to a brain- and body-wide state change, including a characteristic neurovascular event and pulsatile waves of CSF flow. During sleep-deprived wakefulness, hemodynamic and CSF flow pulsations increased within the awake state, causing a flow pattern that resembled N2 NREM sleep. CSF waves were strongly coupled to behavioral failures, a shift in neuronal spectra and pupil constriction (during awake, eyes-open state). Specifically, attention dropped ~2 s before CSF flowed outward (Fig. 5b), and attention recovered ~1 s before CSF flow reversed and was drawn back inward (Fig. 5d). The attentional failures that occur after sleep deprivation thus are locked to the initiation of a process in which the pupil constricts, brain-wide hemodynamics increase and the CSF is transiently flushed outward.

Our data showed a consistent pattern of broadband EEG shifts linked to attentional failures. What type of neural event might these represent? The process of falling asleep is linked to suppression of EEG alpha power and drops in respiratory rate50, which could suggest that the events we observe here represent an accelerated transition toward sleep onset. In addition, elegant prior work has shown that autonomic and arousal state fluctuations are characterized by a sequential modulation of beta power and slow wave activity46,51,52. The EEG pattern we observe here shares similar broadband features, and we find that it represents a behaviorally relevant modulation of neural vigilance state during wakefulness, with attentional consequences. This pattern may thus reflect that sleep deprivation causes sleep-initiating cortical events to occur during wakefulness, but with an interruption of the initiation process before sleep is attained. Given that we found a shift in spectral slope, this pattern could also be consistent with increasing cortical inhibition53. Although we could not directly identify local sleep slow waves here due to the macroscopic nature of these measurements, this effect appeared to be relatively spatially widespread, as it was detected across many EEG electrodes. Our results suggest that sleep deprivation destabilizes global brain state regulation and leads to large-scale, biphasic dynamics. Smaller CSF events could also be infrequently detected in attention failures in the well-rested state with a weaker coupling to pupil diameter, suggesting that typical drowsiness may engage a similar circuit but with reduced switching and instability in the well-rested context.

The neural and attentional drops were also linked to pupil constriction, a classic signature of arousal state that is actively controlled by noradrenergic neuromodulatory projections54,55. Pupil diameter is correlated with attention, heart rate and galvanic skin reflex, reflecting a tight coupling between the state of the central and peripheral arousal systems38,56,57,58. Furthermore, the autonomic system can strongly modulate CSF flow, with particularly strong effects during light sleep47, and autonomic measures were correlated with the attentional dynamics observed here. Although we cannot determine the causal relationship between the pupil and CSF, the high correlation between pupil diameter and CSF pulsatile flow suggests the involvement of the ascending neuromodulatory system in regulating CSF flow during wakefulness59,60. A possible mechanistic explanation for the joint changes in EEG, CSF and autonomic indicators is the well-established parallel projections from key neuromodulatory nuclei such as the noradrenergic locus coeruleus, which projects throughout the cortex and thalamus to modulate neural state, while also directly acting on the sympathetic nervous system61,62,63. Intriguingly, locus coeruleus activity oscillates during NREM sleep and drives infraslow neuronal spectral changes64,65,66, and pupil diameter also covaries with these neural signatures67. Our results suggest that a similar dynamic of temporally structured noradrenergic fluctuations could appear during sleep-deprived wakefulness. In addition, these events could also occur infrequently during rested wakefulness, when attention fails. Other neuromodulators are also correlated with pupil diameter and could contribute37,68, although our hemodynamic data suggest a substantial role for the vasoconstrictive effects of the noradrenergic system69. The dynamics we report were observed during eyes-open wakefulness, demonstrating that brief shifts in attentional state are sufficient to elicit these coordinated changes. Our results could thus be consistent with sleep deprivation causing a destabilization of the ascending arousal system, with brief failures of its wakefulness-promoting actions leading to attentional dysfunction, neuronal arousal suppression and CSF flow.

Our finding that attentional shifts and pupil diameter are linked to large-scale CSF flow, detectable even in the ventricle, suggests a neuromodulatory mechanism that could potentially explain these dual effects. A primary driver of CSF flow is changes in the vasculature, as dilation and constriction of blood vessels in turn propels CSF flow16,25,26,70,71,72,73. Because noradrenaline is a vasoconstrictor33, drops in locus coeruleus activity could decrease neuronal arousal state while dilating cortical blood vessels and constricting the pupil. This would result in an outward flow in the fourth ventricle detected several seconds later, which then would invert as attention recovers and noradrenergic activity increases, reflected in the subsequent pupil dilation. An exciting implication of these dynamics is that pupil diameter could potentially provide a noninvasive, accessible readout of signals related to CSF flow.

Another major driver of CSF flow in awake humans is the cardiac and respiratory cycles, which were tightly associated with the dynamics reported here and could reflect several parallel pathways. Cardiac and respiratory cycles are directly locked to CSF pulsations, as arterial pulsations across the cardiac cycle and reductions in thoracic pressure during inspiration can mechanically propel CSF flow18,74,75. In addition, the locus coeruleus is interconnected with the pre-Bötzinger complex, the brainstem’s primary respiratory rhythm generator76. Thus, the coupled respiration–CSF–pupil activity we observed may reflect the joint modulation of breathing and arousal77,78. The locus coeruleus has not only ascending but also descending projections, synapsing onto preganglionic sympathetic neurons in the spinal cord, which can contribute to coupled dynamics in neural and systemic physiology79. Finally, respiratory fluctuations also influence blood oxygenation and hemodynamics, potentially modulating vasoconstriction that further contributes to CSF dynamics.

An important question for future work is to investigate whether and how these dynamics are linked to solute transport in the brain. Prolonged wakefulness leads to a buildup of toxic metabolic waste products80,81,82, suggesting that more fluid flow would be needed after sleep deprivation. However, the specific consequences of large pulsatile CSF waves for solute transport are not yet established. The CSF waves measured here are relatively high velocity (>1 cm s−1), lasting ~10 s for both the inward and outward phases, indicating that CSF travels many centimeters during each wave, which may be expected to drive solute transport and mixing. In addition, the global hemodynamic waves suggest that this process is coupled to vascular oscillations throughout the brain tissue, which could alter solute transport in the perivascular space. However, the noninvasive methods used in this study could not measure waste clearance, so these possibilities need to be tested in future studies. The observed CSF waves are bidirectional, with sleep deprivation increasing waves in both inward and outward directions, rather than net flow. Intriguingly, a recent study measuring clearance in animal models found that noradrenergic oscillations are linked to waste clearance within NREM sleep83. Our results suggest that an analogous circuit may modulate large-scale CSF flow in humans and furthermore that it can operate within the awake state during attentional failures. Finally, although several studies have shown that sleep clears the neurotoxic waste products that accumulate during wakefulness40,80,81,84,85, a recent study reported the opposite pattern, with reduced clearance during sleep86. In addition to other methodological differences, the conflicting studies used different sleep protocols for the awake measurements (rested wakefulness versus sleep deprived), suggesting that sleep deprivation protocols might be one factor to explore across experiments.

An open question is why both attentional state and CSF flow would be controlled by the same system. One possibility is that the large-scale changes in blood volume that emerge during sleep may be nonoptimal for the waking state, because prolonged drops could reduce oxygen availability. Alternatively, a speculative possibility is that prolonged CSF flow might be incompatible with stable attentional states, for example, because high flow rates alter the concentration of signaling molecules or ionic concentrations that are required for typical waking function. However, we found that although CSF flow was tightly coupled to behavior, it did not exclusively occur during omissions (CSF flow pulses continuously with lower amplitude during wakefulness18,48,87, and flow increased to a lesser degree during successful performance with slow reaction times; Figs. 2 and 3), meaning that individual large events of CSF flow do not prevent behavior. Alternatively, it could be possible that sustained high-amplitude flow over longer timescales interferes with behavioral performance, in which case it would be beneficial to have a circuit that can provide a structured alternation between high-attention and high-CSF pulsation states. Future studies would be needed to test this theory.

Overall, our results demonstrate that the attentional failures caused by sleep deprivation are coupled to a global neurovascular event and large-scale brain fluid transport. When the brain lacks the opportunity to sleep, it enters a suboptimal attentional state that manifests with both sleep-like fluid dynamics and behavioral errors. This coupling points to a central neuromodulatory circuit that controls both attentional state and brain fluid dynamics and shows that the moments of attentional dysfunction we experience after sleep loss are followed by the initiation of widespread fluid flow in the brain.

Methods

Participants

The main experiment enrolled 32 healthy participants, of whom 26 successfully completed both study visits (7 men and 19 women; mean age = 25.6 years ± 4.41 years, range = 19 to 40 years). No statistical methods were used to predetermine the sample size, but our samples are similar to those reported in previous publications12,13,56,88. The study included more women than men due to the space limitations and restriction on head circumference when wearing an EEG cap inside the MRI head coil. All 26 participants completed two experimental sessions spaced 8 to 10 days apart: a well-rested session and a sleep-deprived session. The order of the two sessions was counterbalanced across participants. Half of the participants completed the rested wakefulness session first, whereas the other half completed the sleep-deprived session first. For the well-rested condition, participants completed a full night of sleep at home, and they arrived at the lab no later than 9:00 a.m. for a 10:00 a.m. scan start time. In the sleep deprivation condition, participants arrived at the lab at approximately 7:00 p.m. and stayed overnight until completing the scan the following day. Participants were screened to ensure they had no history of sleep, medical or psychiatric disorders and good typical sleep quality (sleep schedule of 6.5–9 h per night), as assessed by self-rating questionnaires. Exclusion criteria included shift workers, participants that had traveled across time zones in the 3 months before the study and any magnetic resonance contraindication. All participants were required to maintain a regular sleep schedule for 1 week before the visit, with sleep before scans monitored by wrist actigraphy, to consume less than 100 mg of caffeine daily before the study and to refrain from alcohol, caffeine and sleep-aid medications for 24 h before the day of the scan. All participants provided written informed consent, and study procedures were completed as approved by the Boston University Charles River Campus Institutional Review Board (IRB 5059E). All participants received monetary compensation as specified in the IRB protocol.

Overnight experimental design

During the sleep-deprived visit, participants were sleep deprived overnight under constant monitoring by two staff members. At least two researchers remained in the adjacent control room to verify continuous wakefulness during the sleep deprivation period. After arrival, participants were fitted with an EEG cap for overnight monitoring. Participants wore eye-tracking glasses (Tobii Pro 3 Glasses) throughout the night except when performing testing sessions, for continuous eye monitoring while the staff members logged any spontaneous long eyelid closures throughout the night. Research staff continuously monitored the live video of participants’ eyes from the control room during the sleep-deprived night. If the participant closed their eyes for more than 2 s, a staff member requested that they open their eyes and then engaged them in conversation to ensure wakefulness. If the eye closure repeated frequently, staff members took participants on a gentle walk. Between 6:00 a.m. and the morning scan, participants took a shower, during which verbal confirmation of wakefulness was obtained, and they were then provided with breakfast.

An EEG was recorded during four task testing blocks (TBs) during the night of sleep deprivation (TB1: around 9:00 p.m., TB2: around 11:00 p.m., TB3: around 2:00 a.m., TB4: around 5:00 a.m.). Each block consisted of three eyes-open resting-state runs (2 min) and two vigilance task runs (12 min each). The vigilance task consisted of 12-min runs of a computerized aPVT and vPVT (details are provided in the next section). Auditory and visual runs were counterbalanced in order. When not involved in testing sessions, participants were allowed to carry out their own preferred activities, such as reading, writing, listening to music, watching TV or playing games. Lying down, sleeping and vigorous physical activity were not permitted. Nonscheduled light snacks were permitted, whereas caffeinated beverages, alcohol and medications that can influence sleepiness were not allowed during the deprivation protocol.

vPVT and aPVT

Analyses of PVT included the data from both the aPVT and vPVT. During the aPVT (adapted from refs. 87,89), participants were instructed to respond as fast as possible (by pressing a button) to a 0.5 s, 375 Hz tone. Tones were presented binaurally at a comfortable volume through magnetic resonance-compatible earbuds (Etymotic Research, ER3 transducers). Cushions were placed beside the ears to restrict movement and to further reduce scanner noise. During the vPVT, participants were instructed to respond as fast as possible (by pressing a button) when the fixation crosshair changed into a square. The two visual stimuli were designed to have identical luminance to avoid light-induced pupillary responses. For both task modalities, each stimulus lasted 0.5 s, and intertrial intervals ranged from 5 to 10 s. A fixation crosshair was presented throughout. The total duration of each task run was 12 min. Visual stimuli inside the scanner were presented on a VPixx Technologies PROPixx Lite Projector (VPixx Technologies) with a refresh rate of 120 Hz.

MRI experimental design

Participants underwent five fMRI runs: two runs of aPVT (12 min each), two runs of vPVT (12 min each) and one run of eyes-closed resting state (25 min). Auditory and visual run order were counterbalanced. Sixteen participants successfully completed all four task runs for both visits; ten participants completed a subset of these runs (for example, due to an inability to stay awake in the later runs). If participants did not successfully complete all task runs, the successfully completed runs were still included in the analysis. Runs were excluded if participants failed to respond to more than 20 trials, indicating that they could not stay awake. This resulted in 198 runs from 26 participants (6 runs were excluded). During the eyes-closed resting-state session, participants were instructed to press a button on every breath in and breath out as long as they were awake and were told that it was permitted to fall asleep during the scan.

Sleep behavior analysis

Sleep–wake behavior data in the week before the sleep-deprived visit were collected by actigraphy and stored as the sum (activity) of 30-s intervals. These data were analyzed with Actilife (v.6.7, Actigraph), using a sleep–wake detection-validated algorithm. Participants were also instructed to keep notes of bed and rise times to help frame the time in bed during which actigraphy data were analyzed.

EEG and fMRI data acquisition

Participants were scanned on a 3 Tesla Siemens Prisma MRI scanner with a 64-channel head/neck coil. MRI sessions began with a 1-mm isotropic multiecho MPRAGE anatomical scan. Functional scans consisted of single-shot gradient echo multiband EPI sequences with 40 interleaved slices (2.5-mm isotropic resolution, TR = 378 ms, MultiBand factor = 8, TE = 31 ms, flip angle = 37°, field of view (FOV) = 230 × 230, blipped CAIPI shift = FOV / 4 and no in-plane acceleration).

Additional sensors were used to record systemic physiology during the MRI scan. Respiration was measured simultaneously using an MRI-safe pneumatic respiration transducer belt around the abdomen, and pulse was measured with a photoplethysmogram (PPG) transducer (BIOPAC Systems). Physiological signals were acquired at 2,000 Hz using Acqknowledge software and were aligned with MRI data using triggers sent by the MRI scanner.

EEG data were collected using a 64-channel magnetic resonance-compatible EEG cap and BrainAmp magnetic resonance amplifiers (Brain Products). Two reusable reference layers were custom made to record ballistocardiogram (BCG) artifacts, as in Levitt et al.90. As described in Levitt et al.90, with the use of a reference layer, a subset of EEG electrodes can directly record the BCG noise, enabling effective modeling and removal of this noise. This artifact signal can then be used to regress out the BCG artifact from the EEG signals. The first reference layer, used for participants 1–6, was made from an ethylene vinyl acetate shower cap (the inner, insulating layer) and a layer of modal-lycra fabric (the outer layer), which were fastened together by round, plastic grommets to create openings large enough to accommodate the EEG electrodes, as in Luo et al.91. These grommets were placed over electrodes Fpz, Fz, AFz, FCz, Cz, Pz, POz, Oz, F3, F4, F7, F8, T7, T8, C3, C4, P3, P4, PO3 and PO4 and held in place with cyanoacrylate glue. Holes were cut in the reference layer to site each grommet, and larger holes were also made to allow the participants’ ears to pass through. The outer layer of the reference layer was moistened with a solution of baby shampoo, water and potassium chloride to make it conductive before each recording. Finally, the inner face of the EEG cap was lined with Nexcare surgical tape (3M) to avoid wetting the EEG cap. The second reference layer, used for participants 7–26, was designed as reported in Levitt et al.90. It was made from a layer of stretch vinyl (Spandex World) coated in PEDOT ESD500 and P1900 ink (PEDOTinks.com), with grommets placed over Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, C3, C4, P3, P4, O1, O2, F7, F8, T7, T8, P7, P8, Fpz, AFz, Fz, FCz, Cz, Pz, POz and Oz and large holes for the participants’ ears. For this reference layer, no conductive solution or tape was needed. Before each recording, electrode impedances were measured. To ensure safety, participants were not allowed to proceed to EEG–fMRI recordings unless the impedance of all channels was below 100 KΩ; however, a lower impedance of less than 50 KΩ was targeted for signal quality. EEG data were collected at a sampling rate of 5,000 Hz, synchronized to the scanner clock and referenced to channel FCz.

EEG preprocessing

Gradient artifacts were removed through average artifact subtraction92 using a moving average of the previous 30 TRs. All electrodes were then rereferenced to the common average, separately for electrodes contacting the head and the electrodes placed on the reference layer. Electromyogram and electrocardiogram channels placed on the chin and at the back were excluded from the common average. BCG artifacts were removed using regression of reference electrode signals91. Because the position of electrodes and physiological noise dynamics can vary over the recording sessions, we implemented a dynamic time-varying regression of the reference signals in sliding windows93,94. Denoised EEG spectrograms enabled clear visual detection of arousal-locked EEG dynamics (Extended Data Fig. 7a).

EEG spectral analysis

We used EEGLAB95 and MATLAB (R2022a, MathWorks) to analyze EEG data. Continuous EEG data were downsampled to 500 Hz and then bandpass filtered with an EEGLAB antialiasing filter to 0.2–40 Hz. Independent component analysis was used to remove components reflecting eye movements and muscle activity. EEG PSD was calculated using multitaper spectral estimation (Chronux93), using 5-s windows and five tapers. Further analysis was performed on EEG channel POz because this channel consistently had good quality data across participants. The EEG POz channel was used to calculate PSD with 5 s windows and five tapers. For normalized EEG power spectrogram analysis, power values for each trial and each frequency were z scored.

Analyses of the spectral slope of the EEG signal collected over the night of sleep deprivation (outside of the fMRI scanner) used channel POz. The PSD from 0.5 to 35 Hz was estimated using the multitaper method in 10-s epochs with 0.1 s overlap, which were subsequently used to extract the slope of a fitted model using the FOOOF algorithm in the 1- to 35-Hz range32. To separate the aperiodic and oscillatory component of the PSD, we used FOOOF to calculate an initial linear fit of the spectrum in log–log space and subtracted the results from the spectrum. A Gaussian function was then fitted to the largest peak of the flattened PSD exceeding two times the standard deviation. This procedure was iterated for the next largest peak after subtracting the previous peak until no peaks were exceeding the minimum peak threshold. FOOOF settings were kept default with the exception of minimum peak height limits set to be over 0.3 dB. The oscillatory components were finally obtained by fitting a multivariate Gaussian to all extracted peaks simultaneously. After the iterations, the initial fit was added back to the flattened peak-free PSD, resulting in the aperiodic component of the PSD. Afterward, this aperiodic component was fitted again, leading to the final fit with aperiodic intercept and exponent as parameters. The fitted Gaussian functions were referred to as an oscillation-only spectrogram. The aperiodic features were estimated using a sliding window approach with 5-s window length and stepping every 0.3 s.

Sleep scoring

One participant in the well-rested session and one participant in the sleep-deprived session did not have valid EEG recordings during the resting-state scan and were thus excluded from the sleep analysis. The remaining 24 participants’ sleep EEG data were used in sleep scoring and segmenting the BOLD fMRI data into sleep stages (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 1a). Sleep scoring was performed on preprocessed EEG data using the Visbrain toolbox by two scorers following the standard AASM scoring guidelines94,95. Consistent with standard sleep scoring, we observed increased low-frequency power during sleep both after normal sleep and after sleep deprivation and increased alpha frequency power during the awake state (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Disagreements in sleep scores were further discussed and resolved with a third experienced scorer.

Eye tracking and pupillometry

Eye tracking over the sleep-deprived night (8:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. the next day) was performed with eyeglasses (Tobii Pro Glasses 3) with rear-facing infrared cameras. Pupil size was recorded in the morning during EEG–fMRI scans using a magnetic resonance-compatible eye tracker (EyeLink 1000, SR Research) at a sampling rate of 1,000 Hz. The eye tracker was placed at the end of the scanner bore, such that the participant’s left eye could be tracked via the head coil mirror. Before each task run, we began with a calibration of the eye tracker using the standard five-point EyeLink calibration procedure. Moments when the eye tracker received no pupil signal (that is, during eye blinks) were marked automatically during acquisition by the manufacturer’s blink detection algorithm. Pupil data were preprocessed offline. Missing and invalid data due to blinks were replaced using linear interpolation for the period from 100 ms before blink onset to 400 ms after blink offset. Missing data due to long eyelid closures (>1 s) were marked but not interpolated because these segments were later used to detect microsleeps. Following the automated interpolation procedure, the data were manually checked and corrected if any artifacts had not been successfully removed. Twenty-one runs were excluded from the pupil diameter analysis due to technical issues with the eye tracker, and 6 were excluded due to failed video recording, yielding 171 valid runs from 26 participants. Figure 3 analyses used data from these 171 runs. We normalized the pupil diameter time series to z scores. For analyses of pupil responses aligned to either CSF peaks or omission trial onsets, we epoched the pupil time series around each event of interest relative to event onset. We rejected pupil epochs if they contained >1-s consecutive long eyelid closures within the raw data.

MRI preprocessing

The cortical surface was reconstructed from the MPRAGE volume using recon-all from Freesurfer version 6 (refs. 96,97). All functional runs were slice-time corrected using FSL version 6 (slicetimer; https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki) and motion corrected to the middle frame using AFNI (3dvolreg; https://afni.nimh.nih.gov/). Each motion-corrected run was then registered to the anatomical data using boundary-based registration (bbregister).

We defined the left and right hemisphere cortical gray matter ROIs using the automatically generated Freesurfer-derived segmentations of cortical gray matter. Cortical time series were converted to percent signal change by dividing by the mean value of the time series after discarding the first 20 volumes to allow the signal to reach steady state.

CSF inflow analysis

CSF inflow analysis used the raw acquired fMRI data with slice-timing correction but without motion correction, as motion correction corrupts the voxel slice position information needed for inflow analysis, and motion correction cannot be accurately performed on edge slices where tissue moves in and out of the imaging volume. All analyses therefore were performed on segments with framewise displacement of <0.5 mm, and segments with high motion were marked and rejected from any further analysis. To identify the CSF ROI, we registered the single-band anatomical reference scan (SBRef), acquired right before each functional scan, to the participant’s anatomical T1 image. The SBRef scan matched the functional scan in sequence parameters but was acquired without multiband, allowing us to obtain an anatomically defined ROI on an image that was distortion matched to the functional scans. The CSF ROI was manually traced on the anatomical SBRef image and was defined as the CSF voxels in the bottom four slices of the fourth ventricle for each scan for each participant. The ROI did not include edge voxels to minimize partial volume effects, resulting in an ROI that was smaller than the full ventricle width. The researcher was blinded to condition (rested versus sleep deprived) while selecting the CSF ROIs. We extracted the mean signal in this region as the CSF inflow signal. All CSF inflow time series were highpass filtered above 0.01 Hz and converted to percent signal change by dividing the value of the time series by the 15th percentile value (because the CSF signal has a floor due to only measuring inward flow with the acquisition scheme used in the main experiment). CSF time series were upsampled to a new sampling frequency of 4 Hz using spline interpolation before stimulus-locked averages were calculated. Average CSF inflow signals (for example, Fig. 3f) typically show positive baseline values because CSF pulses continuously.

CSF peak-locked analysis

Peaks in the bandpass-filtered CSF signal (0.01–0.1 Hz) during tasks were identified by identifying local maxima that surpassed an amplitude threshold of 30%. These peaks (n = 400) were then used to extract a peak-locked signal (–30 to 30 s relative to the CSF peaks) in pupil diameter (bandpass filtered at 0.01–0.1 Hz). To test for statistical significance of the peak in the pupil signal, we used a time-binned, two-sided t-test, averaging the signal in 2-s bins, testing whether the signal was significantly different from baseline ([–30, –28] s in Fig. 3). The P value was Bonferroni corrected for the number of time bins (number of bins = 30), and time bins with corrected P values less than α = 0.05 were considered significant.

IRF model estimation

We generated 1,000 candidate IRFs using the gamma distribution with varying shape and rate parameter. We selected the IRF that yielded the highest correlation between the IRF-convolved pupil and the cortical gray matter BOLD signal.

Spectral power analysis

Spectral power of BOLD and CSF signals was calculated using Chronux multitaper spectral estimation (five tapers). Power was estimated in the 60-s segments classified as awake, N1, N2 and N3, and the mean power in each participant was calculated from all low-motion (framewise displacement of <0.5) segments. N3 was not analyzed because only five participants entered N3. Statistical testing across spectra was performed with a permutation test that shuffled segments and then compared in frequency bins corresponding to the bandwidth (0.05 Hz), with Bonferroni correction for the number of frequency bins. Pairwise comparisons of mean low-frequency power (0.01–0.1 Hz) in Fig. 1f–h were computed within the participants who had awake data in both well-rested and sleep-deprived visits (n = 18) using a paired t-test. The distributions of spectral power of BOLD and CSF were assumed to be normal when performing t-tests, but this assumption was not formally tested.

Behavioral analysis

Behavioral analyses (Fig. 3) included data from both the aPVT and vPVT. Because mean performance varies across visual and auditory tasks, the omission rate comparison was performed separately for vPVT and aPVT (Fig. 3b; P < 0.001 for each task).

Omission-locked analysis

For Fig. 4, awake omissions (n = 364) were identified in 26 participants, after excluding any omissions with simultaneous eyelid closures longer than 1 s, excluding any segments scored as sleep based on the EEG and excluding high-motion segments. All omissions during confirmed wakefulness periods were marked and their stimulus onset times were used to extract omission-locked signals in the EEG, pupil diameter, heart rate, respiratory flow rate, respiratory volume per time, peripheral vascular tone and CSF signal. Analyses of the spectrogram of the EEG signal collected inside the fMRI scanner used channel POz, calculated in the 0.5- to 30-Hz range using the multitaper method in 10-s epochs with a 0.1-s overlap. They were subsequently used to extract the oscillation-only spectrogram using the FOOOF algorithm in the 1- to 25-Hz range. To test for statistical significance of clusters in the EEG spectrogram and EEG oscillation-only spectrogram, the spectrograms were averaged and compared to a baseline window spectral power (–20 to –10 s relative to omission onset) using a paired two-tailed t-test. The P values corresponding to each pixel of the spectrogram were corrected with a false discovery rate of less than 0.05. To test for statistical significance of the peak in CSF, EEG broadband power, pupil and systemic physiology signals, we considered the window [–20, –10] s before the omission trial onset as baseline. Statistical significance was then calculated for the remaining window in 1-s bins: the signal in each bin was averaged and then compared to baseline using a paired (within-trial) two-sided t-test (P < 0.05). The P value was Bonferroni corrected for the number of time bins tested.

Additionally, three types of omissions (A, B and C) were separately analyzed by finding omissions that were preceded and followed by valid responses (Type A), the first of three or more consecutive omissions (Type B) and the last of three or more consecutive omissions (Type C). Eye-tracking videos were used to identify and exclude trials with long eyelid closures (>1 s). In total, 62 series of continuous omissions without long eyelid closures were identified. One Type B event and five Type C events were rejected due to high motion. The remaining omissions (Type A n = 127, Type B n = 61, Type C n = 57) were marked, and their stimulus onset times were used to extract omission-locked signals. Because this analysis focused on post-trial effects at recovery versus drops of attention, the analysis window was set to [–10, 30] s and the baseline was set to [–10, –5] s.

Systemic physiology

The transducer recording the PPG signal was placed on the left index finger, making sure heartbeats were visible in its signal. MRI scanner triggers were co-recorded with the physiological signals to allow data synchronization. We first removed artifactual spikes from the data by replacing time points exceeding 4 s.d. above the mean with the mean signal level. Low-pass filtering was then performed on the PPG and respiration belt signals at 30- and 10-Hz cutoffs, respectively. From the PPG signal, an indicator for peripheral vascular volume was derived by calculating the standard deviation of the PPG signal in 3-s segments, which is a measure of the excursion amplitude caused by the cardiac beat and is proportional to the volume of blood detected by the PPG sensor98. The variation in heart rate was computed by averaging the differences between pairs of adjacent heartbeats contained in the 6-s window around each trigger and dividing the result by 60 (beats per minute). The filtered chest belt signal was used to derive a measure of respiratory flow rate, which previously was found to strongly affect the fMRI signal throughout the brain99,100. This was done by taking the derivative of the low-pass-filtered belt signal, rectifying it and applying a secondary low-pass filter at a cutoff of 0.13 Hz. The respiratory volume per time was calculated using the standard deviation of the respiratory waveform on a sliding window of 6 s centered at each trigger.

Bidirectional flow experiment

The bidirectional flow measurement in Extended Data Fig. 6 used an independent cohort and new acquisition protocol designed to simultaneously measure inward and outward CSF flow. Ten healthy adults (four women and six men; age range 22 to 29 years, mean 24.1) were included. The same health and MRI exclusion criteria as for Experiment 1 were used. All individuals participated in a single scan session scheduled for 10:00 a.m. To induce attentional failures, participants underwent self-monitored sleep restriction in their homes, sleeping only 4 h the night before the scan. Scans were performed on a 3T Siemens Prisma scanner with a 64-channel head and neck coil. Anatomical scans used a 1-mm isotropic multiecho MPRAGE. Functional runs were acquired using TR = 593 ms, 2.5-mm isotropic resolution, eight slices, FOV = 230 × 230, TE = 31 ms, no multiband, flip angle = 51° and no in-plane acceleration. The acquisition volume was positioned with the top slice intersecting the narrow opening of the fourth ventricle and the bottom slice at the base of the ventricle, allowing us to image both inward and outward CSF simultaneously (but not allowing acquisition of global BOLD signals). Analyses were performed locked to all isolated omissions, with an omission immediately preceded and followed by a hit. For analysis of outflow dynamics, the CSF ROI was manually traced with the top three slices of the imaging volume; for the inflow dynamics, the CSF ROI was traced with the bottom two slices of the imaging volume. All CSF outflow and inflow time series were converted to percent signal change by dividing the value of the time series by the 15th percentile value. The percent signal change in CSF outflow signal was inverted for display (Extended Data Fig. 6b) so that down represented outward flow in both time series.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Jung, C. M., Ronda, J. M., Czeisler, C. A. & Wright, K. P. Comparison of sustained attention assessed by auditory and visual psychomotor vigilance tasks (PVT) prior to and during sleep deprivation. J. Sleep. Res. 20, 348–355 (2011).

Lim, J. & Dinges, D. F. Sleep deprivation and vigilant attention. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1129, 305–322 (2008).

Hudson, A. N., Van Dongen, H. P. A. & Honn, K. A. Sleep deprivation, vigilant attention, and brain function: a review. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 21–30 (2020).

de Mello, M. T. et al. Sleep disorders as a cause of motor vehicle collisions. Int. J. Prev. Med. 4, 246–257 (2013).

Nilsonne, G. et al. Intrinsic brain connectivity after partial sleep deprivation in young and older adults: results from the Stockholm Sleepy Brain study. Sci. Rep. 7, 9422 (2017).

Yeo, B. T. T., Tandi, J. & Chee, M. W. L. Functional connectivity during rested wakefulness predicts vulnerability to sleep deprivation. Neuroimage 111, 147–158 (2015).

Ong, J. L. et al. Co-activated yet disconnected—neural correlates of eye closures when trying to stay awake. Neuroimage 118, 553–562 (2015).

Schneider, M. et al. Spontaneous pupil dilations during the resting state are associated with activation of the salience network. Neuroimage 139, 189–201 (2016).

Chang, C. et al. Tracking brain arousal fluctuations with fMRI. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 4518–4523 (2016).

Chee, M. W. L. et al. Lapsing during sleep deprivation is associated with distributed changes in brain activation. J. Neurosci. 28, 5519–5528 (2008).

Weissman, D. H., Roberts, K. C., Visscher, K. M. & Woldorff, M. G. The neural bases of momentary lapses in attention. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 971–978 (2006).

Vyazovskiy, V. V. et al. Local sleep in awake rats. Nature 472, 443–447 (2011).

Andrillon, T., Burns, A., Mackay, T., Windt, J. & Tsuchiya, N. Predicting lapses of attention with sleep-like slow waves. Nat. Commun. 12, 3657 (2021).

Nir, Y. et al. Selective neuronal lapses precede human cognitive lapses following sleep deprivation. Nat. Med. 23, 1474–1480 (2017).

Horovitz, S. G. et al. Low frequency BOLD fluctuations during resting wakefulness and light sleep: a simultaneous EEG–fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 29, 671–682 (2008).

Fultz, N. E. et al. Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. Science 366, 628–631 (2019).

Helakari, H. et al. Effect of sleep deprivation and NREM sleep stage on physiological brain pulsations. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1275184 (2023).

Dreha-Kulaczewski, S. et al. Inspiration is the major regulator of human CSF flow. J. Neurosci. 35, 2485–2491 (2015).

Chen, L., Beckett, A., Verma, A. & Feinberg, D. A. Dynamics of respiratory and cardiac CSF motion revealed with real-time simultaneous multi-slice EPI velocity phase contrast imaging. Neuroimage 122, 281–287 (2015).

Corsi-Cabrera, M. et al. Changes in the waking EEG as a consequence of sleep and sleep deprivation. Sleep 15, 550–555 (1992).

Bernardi, G. et al. Neural and behavioral correlates of extended training during sleep deprivation in humans: evidence for local, task-specific effects. J. Neurosci. 35, 4487–4500 (2015).

Shoaib, Z. et al. Utilizing EEG and fNIRS for the detection of sleep-deprivation-induced fatigue and its inhibition using colored light stimulation. Sci. Rep. 13, 6465 (2023).

Knoblauch, V., Kräuchi, K., Renz, C., Wirz-Justice, A. & Cajochen, C. Homeostatic control of slow-wave and spindle frequency activity during human sleep: effect of differential sleep pressure and brain topography. Cereb. Cortex 12, 1092–1100 (2002).

Cajochen, C., Knoblauch, V., Kräuchi, K., Renz, C. & Wirz-Justice, A. Dynamics of frontal EEG activity, sleepiness and body temperature under high and low sleep pressure. Neuroreport 12, 2277–2281 (2001).

van Veluw, S. J. et al. Vasomotion as a driving force for paravascular clearance in the awake mouse brain. Neuron 105, 549–561 (2020).

Williams, S. D. et al. Neural activity induced by sensory stimulation can drive large-scale cerebrospinal fluid flow during wakefulness in humans. PLoS Biol. 21, e3002035 (2023).

Holstein-Rønsbo, S. et al. Glymphatic influx and clearance are accelerated by neurovascular coupling. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 1042–1053 (2023).

Van Dongen, H. P. A., Maislin, G., Mullington, J. M. & Dinges, D. F. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose–response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep 26, 117–126 (2003).

Chua, E. C.-P. et al. Sustained attention performance during sleep deprivation associates with instability in behavior and physiologic measures at baseline. Sleep 37, 27–39 (2014).

Lo, J. C. et al. Effects of partial and acute total sleep deprivation on performance across cognitive domains, individuals and circadian phase. PLoS ONE 7, e45987 (2012).

Massar, S. A. A., Lim, J., Sasmita, K. & Chee, M. W. L. Sleep deprivation increases the costs of attentional effort: performance, preference and pupil size. Neuropsychologia 123, 169–177 (2019).

Wilhelm, B. et al. Daytime variations in central nervous system activation measured by a pupillographic sleepiness test. J. Sleep. Res. 10, 1–7 (2001).

Raichle, M. E., Hartman, B. K., Eichling, J. O. & Sharpe, L. G. Central noradrenergic regulation of cerebral blood flow and vascular permeability. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 72, 3726–3730 (1975).

Joshi, S., Li, Y., Kalwani, R. & Gold, J. I. Relationships between pupil diameter and neuronal activity in the locus coeruleus, colliculi, and cingulate cortex. Neuron 89, 221–234 (2015).

Unsworth, N. & Robison, M. K. Pupillary correlates of lapses of sustained attention. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 16, 601–615 (2016).

Konishi, M., Brown, K., Battaglini, L. & Smallwood, J. When attention wanders: pupillometric signatures of fluctuations in external attention. Cognition 168, 16–26 (2017).

Reimer, J. et al. Pupil fluctuations track rapid changes in adrenergic and cholinergic activity in cortex. Nat. Commun. 7, 13289 (2016).

McGinley, M. J. et al. Waking state: rapid variations modulate neural and behavioral responses. Neuron 87, 1143–1161 (2015).

Rauscher, B. C. et al. Neurovascular impulse response function (IRF) during spontaneous activity differentially reflects intrinsic neuromodulation across cortical regions. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.14.612514 (2024).

Jiang-Xie, L.-F. et al. Neuronal dynamics direct cerebrospinal fluid perfusion and brain clearance. Nature 627, 157–164 (2024).

Donoghue, T. et al. Parameterizing neural power spectra into periodic and aperiodic components. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 1655–1665 (2020).

Gao, R., Peterson, E. J. & Voytek, B. Inferring synaptic excitation/inhibition balance from field potentials. Neuroimage 158, 70–78 (2017).

Waschke, L. et al. Modality-specific tracking of attention and sensory statistics in the human electrophysiological spectral exponent. Elife 10, e70068 (2021).

He, B. J., Zempel, J. M., Snyder, A. Z. & Raichle, M. E. The temporal structures and functional significance of scale-free brain activity. Neuron 66, 353–369 (2010).

Chia, C.-H. et al. Cortical excitability signatures for the degree of sleepiness in human. Elife 10, e65099 (2021).

Gu, Y. et al. An orderly sequence of autonomic and neural events at transient arousal changes. Neuroimage 264, 119720 (2022).

Picchioni, D. et al. Autonomic arousals contribute to brain fluid pulsations during sleep. Neuroimage 249, 118888 (2022).

Yang, H.-C. S. et al. Coupling between cerebrovascular oscillations and CSF flow fluctuations during wakefulness: an fMRI study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 42, 1091–1103 (2022).

de Zambotti, M. et al. K-Complexes: interaction between the central and autonomic nervous systems during sleep. Sleep 39, 1129–1137 (2016).

Ogilvie, R. D. The process of falling asleep. Sleep. Med. Rev. 5, 247–270 (2001).

Liu, X. et al. Arousal transitions in sleep, wakefulness, and anesthesia are characterized by an orderly sequence of cortical events. Neuroimage 116, 222–231 (2015).

Liu, X. et al. Subcortical evidence for a contribution of arousal to fMRI studies of brain activity. Nat. Commun. 9, 395 (2018).

Colombo, M. A. et al. The spectral exponent of the resting EEG indexes the presence of consciousness during unresponsiveness induced by propofol, xenon, and ketamine. Neuroimage 189, 631–644 (2019).

Larsen, R. S. & Waters, J. Neuromodulatory correlates of pupil dilation. Front. Neural Circuits 12, 21 (2018).

Phillips, M. A., Szabadi, E. & Bradshaw, C. M. Comparison of the effects of clonidine and yohimbine on pupillary diameter at different illumination levels. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 50, 65–68 (2000).

Soon, C. S. et al. Respiratory, cardiac, EEG, BOLD signals and functional connectivity over multiple microsleep episodes. Neuroimage 237, 118129 (2021).

Chee, M. W. L. & Zhou, J. Functional connectivity and the sleep-deprived brain. Prog. Brain Res. 246, 159–176 (2019).

McGinley, M. J., David, S. V. & McCormick, D. A. Cortical membrane potential signature of optimal states for sensory signal detection. Neuron 87, 179–192 (2015).

Lee, S.-H. & Dan, Y. Neuromodulation of brain states. Neuron 76, 209–222 (2012).

Lloyd, B., de Voogd, L. D., Mäki-Marttunen, V. & Nieuwenhuis, S. Pupil size reflects activation of subcortical ascending arousal system nuclei during rest. Elife 12, e84822 (2023).

Samuels, E. R. & Szabadi, E. Functional neuroanatomy of the noradrenergic locus coeruleus: its roles in the regulation of arousal and autonomic function part I: principles of functional organisation. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 6, 235–253 (2008).

Rodenkirch, C., Liu, Y., Schriver, B. J. & Wang, Q. Locus coeruleus activation enhances thalamic feature selectivity via norepinephrine regulation of intrathalamic circuit dynamics. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 120–133 (2019).