Abstract

The endocannabinoid (eCB) system is involved in many processes in brain function. eCBs depress synaptic transmission by directly activating presynaptic CB1 receptors (CB1Rs), and they indirectly potentiate adjacent synapses by activating astrocytic CB1Rs. In contrast to other neurotransmitter systems, the brain eCB system involves two endogenous ligands, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and anandamide (AEA), and the receptor CB1R. The meaning of this particularity remains unknown. Here we show that 2-AG selectively signals to neurons, eliciting the depression, which is mediated exclusively by neuronal mechanisms. By contrast, AEA signals to astrocytes, inducing lateral synaptic potentiation. Moreover, AEA, but not 2-AG, and astrocyte-mediated signaling are required for hippocampal spike-timing-dependent long-term potentiation. Hence, while 2-AG selectively signals to neurons, AEA specifically signals to astrocytes, evoking contrasting regulatory phenomena of synaptic transmission and plasticity. These results reveal distinct cell-type-specific signaling pathways that involve unique eCBs selectively signaling to either neurons or astrocytes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data used to generate the figures are publicly available at OSF at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SQGZH. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code used to generate the figures are publicly available at OSF at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SQGZH.

References

Araque, A., Castillo, P. E., Manzoni, O. J. & Tonini, R. Synaptic functions of endocannabinoid signaling in health and disease. Neuropharmacology 124, 13–24 (2017).

Castillo, P. E., Younts, T. J., Chávez, A. E. & Hashimotodani, Y. Endocannabinoid signaling and synaptic function. Neuron 76, 70–81 (2012).

Ohno-Shosaku, T. & Kano, M. Endocannabinoid-mediated retrograde modulation of synaptic transmission. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 29, 1–8 (2014).

Han, J. et al. Acute cannabinoids impair working memory through astroglial CB1 receptor modulation of hippocampal LTD. Cell 148, 1039–1050 (2012).

Martin-Fernandez, M. et al. Synapse-specific astrocyte gating of amygdala-related behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1540–1548 (2017).

Noriega-Prieto, J. A., Kofuji, P. & Araque, A. Endocannabinoid signaling in synaptic function. Glia 71, 36–43 (2023).

de Ceglia, R. et al. Specialized astrocytes mediate glutamatergic gliotransmission in the CNS. Nature 622, 120–129 (2023).

Doron, A. et al. Hippocampal astrocytes encode reward location. Nature 609, 772–778 (2022).

Kofuji, P. & Araque, A. Astrocytes and behavior. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 44, 49–67 (2021).

Henneberger, C., Papouin, T., Oliet, S. H. R. & Rusakov, D. A. Long-term potentiation depends on release of d-serine from astrocytes. Nature 463, 232–236 (2010).

Khakh, B. S. & McCarthy, K. D. Astrocyte calcium signaling: from observations to functions and the challenges therein. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7, a020404 (2015).

Covelo, A. & Araque, A. Neuronal activity determines distinct gliotransmitter release from a single astrocyte. eLife 7, e32237 (2018).

Navarrete, M. & Araque, A. Endocannabinoids mediate neuron–astrocyte communication. Neuron 57, 883–893 (2008).

Navarrete, M. & Araque, A. Endocannabinoids potentiate synaptic transmission through stimulation of astrocytes. Neuron 68, 113–126 (2010).

Robin, L. M. et al. Astroglial CB1 receptors determine synaptic D-serine availability to enable recognition memory. Neuron 98, 935–944 (2018).

Dobrunz, L. E. & Stevens, C. F. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation, and depletion at central synapses. Neuron 18, 995–1008 (1997).

Perea, G. & Araque, A. Astrocytes potentiate transmitter release at single hippocampal synapses. Science 317, 1083–1086 (2007).

Raastad, M. Extracellular activation of unitary excitatory synapses between hippocampal CA3 and CA1 pyramidal cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 7, 1882–1888 (1995).

Murataeva, N., Straiker, A. & Mackie, K. Parsing the players: 2-arachidonoylglycerol synthesis and degradation in the CNS. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 1379–1391 (2014).

Gómez-Gonzalo, M. et al. Endocannabinoids induce lateral long-term potentiation of transmitter release by stimulation of gliotransmission. Cereb. Cortex 25, 3699–3712 (2015).

Baraibar, A. M. et al. Spatial organization of neuron–astrocyte interactions in the somatosensory cortex. Cereb. Cortex 33, 4498–4511 (2023).

Martín, R., Bajo-Grañeras, R., Moratalla, R., Perea, G. & Araque, A. Circuit-specific signaling in astrocyte–neuron networks in basal ganglia pathways. Science 349, 730–734 (2015).

Chevaleyre, V., Takahashi, K. A. & Castillo, P. E. Endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity in the CNS. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 29, 37–76 (2006).

Kreitzer, A. C. & Regehr, W. G. Retrograde inhibition of presynaptic calcium influx by endogenous cannabinoids at excitatory synapses onto Purkinje cells. Neuron 29, 717–727 (2001).

Ohno-Shosaku, T. et al. Presynaptic cannabinoid sensitivity is a major determinant of depolarization-induced retrograde suppression at hippocampal synapses. J. Neurosci. 22, 3864–3872 (2002).

Wilson, R. I. & Nicoll, R. A. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature 410, 588–592 (2001).

Heinbockel, T. et al. Endocannabinoid signaling dynamics probed with optical tools. J. Neurosci. 25, 9449–9459 (2005).

Covelo, A., Eraso-Pichot, A., Fernández-Moncada, I., Serrat, R. & Marsicano, G. CB1R-dependent regulation of astrocyte physiology and astrocyte–neuron interactions. Neuropharmacology 195, 108678 (2021).

Klapoetke, N. C. et al. Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. Nat. Methods 11, 338–346 (2014).

Ade, K. K. & Lovinger, D. M. Anandamide regulates postnatal development of long-term synaptic plasticity in the rat dorsolateral striatum. J. Neurosci. 27, 2403–2409 (2007).

Feldman, D. E. The spike-timing dependence of plasticity. Neuron 75, 556–571 (2012).

Andrade-Talavera, Y., Pérez-Rodríguez, M., Prius-Mengual, J. & Rodríguez-Moreno, A. Neuronal and astrocyte determinants of critical periods of plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 46, 566–580 (2023).

Florian, C., Vecsey, C. G., Halassa, M. M., Haydon, P. G. & Abel, T. Astrocyte-derived adenosine and A1 receptor activity contribute to sleep loss-induced deficits in hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory in mice. J. Neurosci. 31, 6956–6962 (2011).

Navarrete, M. et al. Astrocytes mediate in vivo cholinergic-induced synaptic plasticity. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001259 (2012).

Olofsson, L. et al. Fine tuning of sub-millisecond conformational dynamics controls metabotropic glutamate receptors agonist efficacy. Nat. Commun. 5, 5206 (2014).

Kofuji, P. & Araque, A. G-protein-coupled receptors in astrocyte–neuron communication. Neuroscience 456, 71–84 (2021).

Rusakov, D. A. Disentangling calcium-driven astrocyte physiology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 226–233 (2015).

Srinivasan, R. et al. New transgenic mouse lines for selectively targeting astrocytes and studying calcium signals in astrocyte processes in situ and in vivo. Neuron 92, 1181–1195 (2016).

Volterra, A., Liaudet, N. & Savtchouk, I. Astrocyte Ca2+ signalling: an unexpected complexity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 327–335 (2014).

Bindocci, E. et al. Three-dimensional Ca2+ imaging advances understanding of astrocyte biology. Science 356, eaai8185 (2017).

Heller, J. P. & Rusakov, D. A. Morphological plasticity of astroglia: understanding synaptic microenvironment. Glia 63, 2133–2151 (2015).

Patrushev, I., Gavrilov, N., Turlapov, V. & Semyanov, A. Subcellular location of astrocytic calcium stores favors extrasynaptic neuron–astrocyte communication. Cell Calcium 54, 343–349 (2013).

Popov, A. et al. Astrocyte dystrophy in ageing brain parallels impaired synaptic plasticity. Aging Cell 20, e13334 (2021).

Santello, M., Toni, N. & Volterra, A. Astrocyte function from information processing to cognition and cognitive impairment. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 154–166 (2019).

Heifets, B. D. & Castillo, P. E. Endocannabinoid signaling and long-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71, 283–306 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank W. P. F. Driever for synthesizing LEI-401 and B. F. Cravatt (The Scripps Reseach Insitute) for generously donating Napepld−/− and Dagla−/− mice. We thank C. Nanclares (Autonomous University of Madrid) for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH-MH R01MH119355 and NIH-NIDA R01DA048822) and Department of Defense (W911NF2110328) to A.A., NIH-MH R01MH119355 to P.K. and The Dutch Research Council (VICI, 724.017.002) to M.v.d.S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A.N.-P. and R.F.-M. performed and analyzed the electrophysiological experiments. J.A.N.-P., P.G. and L.B. performed and analyzed the calcium experiments. R.F.-M. and J.A.N. performed the sensor experiments. R.C., S.C. and Y.L. developed the 2-AG sensors. A.A., P.K. and J.A.N.-P. conceived the study and wrote the paper. J.A.N.-P., R.F.-M., A.E.-P., U.B.F., A.R.-M., M.v.d.S., J.F.C., G.M., P.K. and A.A. participated in the drafting of the paper, the final version of which they approved for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Neuroscience thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 2-AG and AEA are released at the same synapses and Paired-pulse ratio of EPSC from CA1 pyramidal neurons in different experimental conditions.

(a)Bargraph showing the percentage of DSE observed in the homoneuron (38%), e-SP observed in heteroneuron (45%) and both phenomena (19%) of the individual synapses. Notably, these results suggest that 2-AG and AEA can be released at the same synapses. Chi-square goodness of fit test (n = 26/26 vs. 25/23, p = 0.9). (b) Paired-pulse ratio of the EPSCs before and after homoneuron ND in control conditions (n = 26/26, p < 0.0001), AM-251 (n = 7/5, p = 0.9), Gfap-Cnr1 + /+ (n = 5/3, p = 0.007), Gfap-Cnr1−/− (n = 5/3, p = 0.04), THL (n = 5/4, p = 0.4), DAGLα−/− (n = 9/3, p = 0.1), LEI-401 (n = 6/5, p = 0.01), NAPE-PLD−/− (n = 5/3, p = 0.04). (c) Paired-pulse ratio of the EPSCs before and after heteroneuron ND in control conditions (n = 25/23, p < 0.0001), AM-251 (n = 5/5, p = 0.6), Gfap-Cnr1 + /+ (n = 7/3, p = 0.03), Gfap-Cnr1−/− (n = 6/3, p = 0.9), THL (n = 5/4, p = 0.003), DAGLα−/− (n = 10/3, p = 0.002), LEI-401 (n = 6/4, p = 0.9), NAPE-PLD−/− (n = 7/3, p = 0.4). Two-tiled Student’s paired t-test. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Data are mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Intracellular calcium mobilization is necessary for the endocannabinoid-Induced Synaptic regulation.

(a) Pseudocolor images showing postsynaptic calcium elevation before (left image) during (middle image) and after (right image) ND in control condition and with intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA (bottom images). (b). Traces showing calcium responses to ND in control condition (upper traces) and with postsynaptic BAPTA (bottom traces). Scale bar 10 s. (c) Time course of homoneuron EPSC amplitude before and after ND (red arrow) in control condition. (d) Relative changes from control basal values of homoneuron EPSC amplitude before and after ND in control conditions (n = 26/26, p < 0.0001) and intracellular BAPTA (n = 10/3, p = 0.06). (e) Time course of the heteroneuron EPSC amplitude before and after ND (green arrow) in control condition. (f) Relative changes from control basal values of heteroneuron EPSC amplitude before and after ND in control conditions (n = 25/23, p < 0.0001) and intracellular BAPTA (n = 6/3, p = 0.8). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Two-tiled Student’s paired t-test. Data are mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Inhibition of FAAH, but not MGL, increases the e-SP magnitude. Exogenous AEA occludes e-SP but not DSE.

(a) Relative changes from control basal values of synaptic efficacy before and after ND of the heteroneuron in control condition (n = 25/23, p < 0.0001), in the presence of URB-597 (2 µM; n = 5/3, p < 0.0001) and JZL-184 (1 µM; n = 5/2, p = 0.01). (b) Relative changes from control basal values of synaptic efficacy versus number of APs elicited by stimulation of pyramidal neurons with depolarizing pulses of variable durations that evoked trains of APs in current clamp conditions. Synapses were identified as showing e-SP in control conditions(150 ms: n = 6/3; p = 0.4; 600 ms: n = 5/3, p = 0.3; 1200 ms: n = 6/3, p = 0.01; 3000 ms: n = 5/3, p = 0.01) (black circles) and in the presence of LEI-401 (150 ms: n = 5/2; p = 0.8; 600 ms: n = 5/2, p = 0.3; 1200 ms: n = 5/2, p = 0.3; 3000 ms: n = 5/3, p = 0.1) (white circles). (Scale bars, 20 mV/50 ms; 20 mV/100 ms; 20 mV/100 ms). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Two-tiled Student’s paired t-test. #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunn’s; n.s., nonsignificant (p > 0.05). Data are mean ± s.e.m. (c) left Relative changes of synaptic efficacy, before and after homoneuron ND (purple arrow), of the heteroneuron from control (left; n = 8/5, p < 0.001) and bath applied AEA (3 µM; right) condition (n = 7/4, p = 0.2). (d) Relative changes from control basal values of heteroneuron synaptic efficacy before and after homoneuron ND in control conditions, and in the presence of bath applied AEA. An increase in the basal synaptic transmission was observed in the presence of AEA (n = 7, p < 0.01). Student’s unpaired t-test. (e) Relative changes of synaptic efficacy before and after ND (red arrow), of the homoneuron in control (left; n = 6/5, p < 0.01) and bath applied AEA (3 µM; right) condition (n = 5/3, p < 0.01). (f) Relative changes from control basal values of homoneuron synaptic efficacy before and after homoneuron ND in control conditions, and in the presence of AEA. An increase in the basal synaptic transmission was observed in the presence of AEA from control conditions (n = 5, p < 0.05). Adult animals ( ≥ 6 weeks; males and females) were used; Student’s unpaired t-test. Student’s unpaired t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, **p < 0.001; Student’s t-test. Data are mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 4 2-AG signals to neurons and induces DSE and AEA signals to astrocytes and induces lateral regulation in the somatosensory cortex and dorsal striatum.

(a) left. Drawing showing the somatosensory cortex location in slices (S1). Right, simplified schematic representation of the experimental design showing the homoneuron from dual recording, the recording (rec.) and synaptic stimulator (stim.) electrodes (ND, Neuronal depolarization during 5 s). (b) Top. EPSCs traces showing homoneuron EPSC amplitudes before (basal) and after (ND) and the recovery (recovery) homoneuron ND. (Scale bars: 10 pA, 25 ms). Bottom. Time course of EPSC amplitude before and after ND (green arrow) in control condition of the homoneuron. (c) Relative changes from control basal values of EPSC amplitude before and after ND of the homoneuron in control conditions (n = 15/9, p < 0.001), THL (n = 5/3, p = 0.7) and LEI-401 (n = 6/5, p < 0.01); The decrease in the synaptic transmission was abolished in the presence of THL (n = 5, p < 0.001) but still preserved in LEI-401 (n = 6/5, p = 0.3). One-way ANOVA, post hoc Holm–Sidak. (d) Schematic representation of the experimental design of neuronal dual recording showing both homoneuron and heteroneuron, the recording (rec.) and synaptic stimulator (stim.) electrodes (ND, Neuronal depolarization during 5 s). (e) Top. EPSCs traces showing heteroneuron EPSC amplitudes before (basal) and after (ND) and the recovery (recovery) homoneuron ND. (Scale bars: 10 pA, 25 ms). Bottom. Time course of the heteroneuron EPSC amplitude before and after ND (pink arrow) in control condition. (f) Relative changes from control basal values of heteroneuron EPSC amplitude before and after ND in control conditions (n = 14/10, p < 0.001), THL (n = 5/3, p < 0.05) and LEI-401 (n = 7/5, p = 0.3). The decrease in the synaptic transmission was preserved in the presence of THL (n = 5, p = 0.9) but abolished in LEI- 401 (n = 7, p < 0.001). One-way ANOVA, post hoc Holm–Sidak. (g) left. Drawing showing the dorsal striatum location in slices (Str). Right, simplified schematic representation of the experimental design showing the homoneuron from dual recording, the recording (rec.) and synaptic stimulator (stim.) electrodes (ND, Neuronal depolarization during 5 s). (h) Top. EPSCs traces showing homoneuron EPSC amplitudes before (basal) and after (ND) and the recovery (recovery) homoneuron ND. (Scale bars: 20 pA, 25 ms). Bottom. Time course of EPSC amplitude before and after ND (blue arrow) in control condition of the homoneuron. (i) Relative changes from control basal values of EPSC amplitude before and after ND of the homoneuron in control conditions (n = 15/10, p < 0.001), THL (n = 5/4, p = 0.2) and LEI-401 (n = 7/5, p < 0.01); The decrease in the synaptic transmission was abolished in the presence of THL (n = 5, p < 0.05) but still preserved in LEI-401 (n = 7/5, p = 0.5). One-way ANOVA, post hoc Dunn. (j) Schematic representation of the experimental design of neuronal dual recording showing both homoneuron and heteroneuron, the recording (rec.) and synaptic stimulator (stim.) electrodes (ND, Neuronal depolarization during 5 s). (k) Top. EPSCs traces showing heteroneuron EPSC amplitudes before (basal) and after (ND) and the recovery (recovery) homoneuron ND. (Scale bars: 20 pA, 25 ms). Bottom. Time course of the heteroneuron EPSC amplitude before and after ND (red arrow) in control condition. (l) Relative changes from control basal values of heteroneuron EPSC amplitude before and after ND in control conditions (n = 19/12, p < 0.001), THL (n = 6/5, p < 0.01) and LEI-401 (n = 7/6, p = 0.5). The increase in the synaptic transmission was preserved in the presence of THL (n = 6, p = 0.8) but abolished in LEI-401 (n = 7, p < 0.001). Adult animals ( ≥ 6 weeks; males and females) were used; One-way ANOVA, post hoc Dunn. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, **p < 0.001; Student’s paired t-test. #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunn’s; n.s., nonsignificant (p > 0.05). Data are mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 5 2-AG, but not AEA, modulates inhibitory synaptic transmission.

(a) Drawing showing the hippocampus location in slices. (b) Top. IPSCs traces recorded in the presence of CNQX 20 µM + D-AP5 50 µM, showing IPSC amplitudes in basal (black trace), and after ND in control (red trace), in the presence of LEI-401 (blue trace) and in THL (blue trace). (Scale bars: 10 pA, 10 ms). Bottom. Time course of IPSC amplitude before and after ND (pink arrows) in control condition, in the presence of LEI-401 and THL. (c) Relative changes of IPSC amplitude before and after ND in control conditions (n = 9/5, p < 0.01), LEI-401 (n = 8/4, p < 0.01) and THL (n = 6/2, p = 0.9). The decrease in the synaptic efficacy was preserved in LEI-401 (n = 8, p < 0.05) but abolished in THL (n = 6, p = 0.9); one-way ANOVA, post hoc Holm–Sidak. (d) Traces showing IPSC amplitudes in basal (1; black trace), and after AEA puff (2; red trace). (Scale bars: 20 pA, 10 ms). (e) Time course of the IPSC amplitude before and after bath applied AEA (3 µM; green bar). (f) Relative changes of IPSC amplitude before (1) and after (2) bath applied AEA (3 µM; n = 6/2, p < 0.01). Adult animals ( ≥ 6 weeks; males and females) were used; Student’s paired t-test. #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, nonsignificant (p > 0.05). Data are mean ± s.e.m.

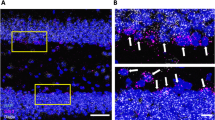

Extended Data Fig. 6 Enhanced synaptic efficacy by optogenetic stimulation of CA1 pyramidal neurons and Anandamide regulates long-term depression (LTD) in the dorsolateral striatum.

(a) Drawing showing viral vectors (GFAP-GCaPM6f and Syn-CrimsonR-Tdtom) injected into the CA1 of the hippocampus. (b) Fluorescence image showing ChrimsonR expression in neurons (left upper image), GCaMP6f in astrocytes (left bottom image) and merge (right image) in the CA1 of the hippocampus. (c) Neuronal response to optogenetic stimulation of CA1 pyramidal neuron expressing the opsin crimsonR (red upper trace) and empty virus (black middle trace) during an opto-stimulation pulse (square red bottom trace; (λ = 580 nM, 5 s). Scale bars 10 mV, 100 ms. (d) Left. schematic representation of the experimental design in which a patched neuron is activated during an opto-stimulation pulse (λex = 580 nM, 5 s). Right top. EPSCs evoked by minimal stimulation (0.1–10 mA) showing EPSC amplitudes and failures of synaptic transmission (20 consecutive stimuli) before (basal) and after opto-stimulation (opto-stim). (Scale bars: 10 pA, 20 ms). Bottom. Synaptic efficacy of EPSC during baseline (black bar) and after opto-stimulation (red bar; n = 6/3, p < 0.01). (e) Schematic representation of the experimental design showing AEA puff. (f) Left. Pseudocolor images showing fluorescence intensities in CA1 astrocyte in basal condition and during AEA puff. Right. Representative traces showing astrocytes responding to AEA puff. Scale bars 0.4 ΔF/F, 20 s. (g) Relative astrocyte calcium event probability before and after AEA puff in astrocytes expressing GCaMP6f in control condition (n = 7/2, p < 0.05), in the presence of AM-251 (n = 7/2, p = 0.2) and in Gfap-Cnr1−/− (n = 7/2, p = 0.8). The increase in the calcium probability was abolished in the presence of AM-251 (n = 7, p < 0.05) and in Gfap-Cnr1−/− mice (n = 7, p < 0.05). Adult animals ( ≥ 6 weeks; males and females) were used; One-way ANOVA, post hoc Holm–Sidak. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, **p < 0.001; Student’s paired t-test. #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Holm–Sidak, nonsignificant (p > 0.05). Data are mean ± s.e.m. (h) Time course of the LTD induced by HFS in control condition (green circles), under DAGL inhibitor, THL (10 µM; orange circles) and in the presence of NAPE-PLD inhibitor, LE I-401 (10 µM; purple circles) (i) Relative changes from control basal values of EPSC amplitude before and after HFS in control conditions (n = 7/5, p < 0.001; green circles), under DAGL inhibitor, THL (10 µM; n = 5/3, p < 0.001; orange circles), and in the presence of NAPE-PLD inhibitor, LE I-401 (10 µM; n = 5/3, p < 0.01; purple circles). The LTD was preserved in the presence of THL (n = 5, p = 0.6) and it turned in LTP in the presence of LEI-401 (n = 5, p < 0.001); Adult animals ( ≥ 6 weeks; males and females) were used; one-way ANOVA, post hoc Holm–Sidak. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, **p < 0.001; Student’s paired t-test. #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Holm– Sidak, nonsignificant (p > 0.05). Data are mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 7 e-SP-mediated AEA is independent of PTX-insensitive G protein coupled receptor.

(a)Time course of the synaptic efficacy before and after AEA puff (red arrow) in PTX treated slices. (b) Relative changes from control basal values of the synaptic efficacy before (grey bar) and after (red bar) AEA puff (n = 6/2, p < 0.01). (c)Time course of the heteroneuron EPSC amplitude before and after ND (red arrow) in control condition of PTX treated slices. (d) Relative changes from control basal values of heteroneuron EPSC amplitude before (grey bars) and after ND (red bars) in control conditions (n = 5/3, p < 0.05) and in the presence of LEI-401 (n = 5/3, p = 0.2). (e) Schematic representation of the experimental design of ATP puff to astrocytes expressing GCaMP6f in PTX treated slices. (f) Left. Pseudocolor images showing astrocytes calcium elevation in basal condition and in response to ATP puff. Right. Representative traces showing astrocytes calcium elevation to ATP puff. Scale bars 2 ΔF/F, 10 s. (g) Heat map of Calcium-based fluorescence levels showing astrocyte Calcium events to ATP puff (red arrow, time 0), in control condition (18 ROIs). (h) Relative astrocyte calcium event probability before (grey bar; basal) and after ATP puff (red bar; ATP puff) in astrocytes expressing GCaMP6f and PTX treated slices (n = 8/2, p < 0.01) and in the absence of Gq-DREADDs (n = 8, **p < 0.01;). Adult animals ( ≥ 6 weeks; males and females) were used; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Student’s paired and unpaired t-test. Data are mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 8 STD LTP requires presynaptic activity and depends on NMDA, Group I mGluR and astrocyte calcium mobilization.

(a) Top. Representative traces before (1) and after (2) repetitive postsynaptic AP without presynaptic spike. Bottom. Time course of the EPSC before and after repetitive postsynaptic AP without presynaptic spike. Scale bars 50 pA, 20 ms. (b) Bargraph of the EPSC before (basal) and after (post-AP) repetitive postsynaptic AP (n = 6/3, p = 0.9). Scale bars 10 mV, 50 ms. (c) Representative EPSCs 30 minutes after STDP protocol in control condition (black trace), in the presence of D-AP5 (light gray trace) and in the presence of MPEP + LY (dark gray trace). Scale bars 40 pA, 20 ms. (d) Time course of the LTP induced by STDP in control condition (n = 8 cells, p < 0.001; black circles; control), under NMDAR antagonist, D-AP5 (50 µM; n = 6, p = 0.94; light grey circles; D-AP5), and in the presence of group I mGluR antagonists, MPEP and LY (50 µM + 100 µM; n = 5, p = 0.48; dark grey circles; MPEP + LY). (e) Bargraph of the LTP induced by STDP in control condition (black graph; control), under NMDAR antagonist, D-AP5 (light grey graph; D- AP5) and in the presence of group I mGluR antagonists, MPEP and LY (dark grey graph; MPEP + LY). Note that LTP is abolished in the presence of D-AP5 (p < 0.05) and MPEP + LY (p < 0.05), demonstrating that LTP depends on NMDAR and Group I mGluRs. (f) Representative EPSCs 30 minutes after STDP protocol in control condition (black trace), in the presence of D-AP5 (light gray trace) and in the presence of MPEP + LY (dark gray trace). Scale bars 40 pA, 20 ms. (g) Time course of the LTP induced by STDP in control condition (black circles; control), in calcium chelator BAPTA loading astrocytes (20 mM; n = 6, p = 0.95; white circles; aBAPTA), and in IP3R2−/− (n = 6, p = 0.40; red circles; IP3R2−/−). (h) Bargraph of the LTP induced by STDP in control condition (black circles; control), in calcium chelator BAPTA loading astrocytes (white circles; aBAPTA), and in IP3R2−/− (red circles; IP3R2−/−). Note that LTP is prevented in BAPTA (p < 0.01) loading astrocyte network and in IP3R2−/− (p < 0.05), demonstrating the necessary role of astrocytes activation LTP induction. Adult animals ( ≥ 6 weeks; males and females) were used; One-way ANOVA, post hoc Dunn. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, **p < 0.001; Student’s paired t-test. #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunn’s; n.s., nonsignificant (p > 0.05). Data are mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 9 AEA facilitates the LTP induced by STDP protocol.

(a) Time course of the EPSC amplitude before and after LTP induced by STDP protocol (Δt = 20 ms) in control condition (n = 5, p < 0.001; black circles, control), and in the presence of AEA (3 µM, n = 5, p < 0.05; red circles, AEA + t-LTP). Scale bars 10 mV, 50 ms. (b) Relative EPSC amplitude in control condition (n = 5; black bar, control) and in the presence of AEA (3 µM, n = 5; red circles, AEA + t-LTP) after STDP protocol (STDP Control vs. STDP AEA, n = 5, p < 0.05). (c) Time course of the EPSC amplitude before and after STDP protocol (Δt = 50 ms) in control condition (n = 5, p = 0.9; black circles, control), and in the presence of URB-597 (1 µM, n = 5, p < 0.05; red circles, URB-597). Scale bars 10 mV, 50 ms. Adult animals ( ≥ 6 weeks; males and females) were used; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Student’s unpaired t-test. Data are mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Model showing that AEA signals to astrocytes and induces e-SP and 2-AG signals to neurons and induces DSE.

(a) Neuronal depolarization (ND; homoneuron) produces the release of 2-AG that acting through presynaptic CB1R induces DSE. Simultaneously, the release of AEA produced by homoneuronal depolarization induces astrocyte calcium mobilization through CB1R activation that, in turn, generates lateral potentiation (e-SP) in the heteroneuron.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Figs. 1-4 and Extended Data Figs. 1-9

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 1

Analysis of electrophysiological recordings using patch-clamp techniques, including pharmacological manipulations and the use of transgenic animal models.

Source Data Fig. 2

Calcium dynamics recordings in astrocytes using GCaMP6 and cannabinoid sensors, including pharmacological manipulations and the use of transgenic animal models.

Source Data Fig. 3

Calcium dynamics recordings in astrocytes using GCaMP6, including pharmacological manipulations and the use of transgenic animal models.

Source Data Fig. 4

Analysis of electrophysiological recordings using patch-clamp techniques and application of synaptic plasticity protocols, including pharmacological manipulations and the use of transgenic animal models.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Analysis of electrophysiological recordings using patch-clamp techniques, including pharmacological manipulations and the use of transgenic animal models.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Analysis of electrophysiological recordings using patch-clamp techniques, including pharmacological manipulations (BAPTA).

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Analysis of electrophysiological recordings using patch-clamp techniques, including pharmacological manipulations and the use of transgenic animal models.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Analysis of electrophysiological recordings using patch-clamp techniques, including pharmacological manipulations.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Analysis of electrophysiological recordings using patch-clamp techniques, including pharmacological manipulations.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Analysis of electrophysiological recordings using patch-clamp techniques and optostimulation and application of synaptic plasticity protocols, including pharmacological manipulations, the use of transgenic animal models and viral approaches.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Analysis of electrophysiological recordings using patch-clamp techniques and calcium dynamics recordings in astrocytes using GCaMP6, including pharmacological manipulations.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Analysis of electrophysiological recordings using patch-clamp techniques and application of synaptic plasticity protocols, including pharmacological manipulations and the use of transgenic animal models.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Analysis of electrophysiological recordings using patch-clamp techniques and application of synaptic plasticity protocols.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Noriega-Prieto, J.A., Falcón-Moya, R., Noeker, J.A. et al. Distinct endocannabinoids specifically signal to astrocytes or neurons in the adult mouse hippocampus. Nat Neurosci 29, 445–454 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02148-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02148-1