Abstract

Anoectochilus roxburghii, a highly valued medicinal plant in traditional Chinese medicine, exhibits unique pharmacological properties and broad application value. In this study, we de novo assembled and annotated haplotype-resolved chromosome-level genomes of A. roxburghii cultivar ‘Xiaoyuanye’ by integrating PacBio HiFi reads and Hi-C data. The final assembly sizes were 1.92 Gb and 1.93 Gb, with contig N50 values of 22.72 Mb and 22.17 Mb, respectively. A total of 26,239 and 26,324 protein-coding genes were annotated, establishing a high-quality genomic resource for further research. Moreover, comparative genomic analysis revealed that A. roxburghii possesses 1,060 unique gene families and has undergone significant expansion of 2,100 gene families during evolution, providing crucial theoretical insights into the adaptive evolution of Orchidaceae species. The availability of the high-quality genomic data providing a crucial genetic foundation for elucidating the biosynthetic mechanisms and regulatory networks of pharmacologically active compounds in A. roxburghii.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Anoectochilus roxburghii (Wall.) Lindl., a perennial herb of the Orchidaceae family and Anoectochilus genus, is highly valued for its dual medicinal and edible properties1. This species has been used as a natural, nutritional food ingredient and a traditional Chinese herb for thousands of years2. A. roxburghii has various biological activities, including anti-tumor, anti-oxidative, hypoglycemic, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory activities3,4,5. Research indicates that the primary active ingredients in A. roxburghii includes alkaloids, flavonoids, polysaccharides, steroids, and terpenes6,7. Among these, flavonoids are widely recognized as important indicator components for quality assessment of A. roxburghii1,8,9.

In this study, we report the first haplotype-resolved genome assembly of wild A. roxburghii widely distributed in Fujian Province, China. Through an integrated multi-omics approach, we combined PacBio high-fidelity (HiFi) sequencing, high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) sequencing, Illumina short-read sequencing, and RNA-Seq data to assemble and annotate the haplotype-resolved genomes of A. roxburghii. The haploid genomes exhibit sizes of 1.92 Gb and 1.93 Gb, with contig N50 values of 22.72 Mb and 22.17 Mb. The Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO)10 analysis demonstrates a completeness score of 93.5% and 92.9%, respectively. Furthermore, we annotated a total of 26,239 and 26,324 protein-coding genes in the two haplotypes. Phylogenetic analysis elucidated the evolutionary relationships among A. roxburghii and related Orchidaceae species. These high-quality haplotype-resolved genomes provide a fundamental genetic resource that will enable comprehensive elucidation of secondary metabolite (particularly flavonoid) biosynthetic pathways and will significantly advance both functional genomics studies and molecular breeding applications.

Methods

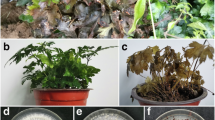

Sample collection, library construction, and sequencing

High-quality PacBio HiFi libraries were prepared following the manufacturer’s protocol and sequenced on a PacBio Sequel II platform, yielding a total of 162.58 Gb circular consensus sequencing (CCS) reads with N50 of 17,251 bp (~78 × coverage). Libraries prepared with Illumina TruSeq PCR-free kits were sequenced on a NovaSeq X platform, generating 150 bp paired-end reads that yielded 124.55 Gb of data. For Hi-C library construction, young leaves were cross-linked with formaldehyde. Genomic DNA was then isolated using the CTAB method and digested with DpnII. The Hi-C libraries were prepared following a standard protocol and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 3000 platform, generating a total of 188.98 Gb of paired-end reads (Table 1). RNA sequencing libraries were generated with the TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, with triplicate biological replicates sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform.

Estimation of genome size and heterozygosity

The genome size and heterozygosity of A. roxburghii were estimated through k-mer frequency analysis, the method that involves analyzing the distribution of k-mers within the genome based on Poisson’s distribution11. Prior to assembly, we used Jellyfish12 (v2.2.10) to generate the 39-mer frequency distribution of PacBio HiFi reads. Following this, we employed GenomeScope 2.013 to evaluate the genomic features. Consequently, we obtained the haploid genome size of A. roxburghii is 1.92 Gb, with a heterozygosity rate of 2.19% (Fig. 1).

Haplotype-resolved genome assembly

We assembled the A. roxburghii genome using multiple sequencing datasets, including 162.58 Gb (~78 × coverage) PacBio HiFi reads, 124.55 Gb (~60 × coverage) Illumina reads, and 188.98 Gb (~90 × coverage) Hi-C paired reads (Table 1). To address the assembly challenges caused by the high heterozygosity of A. roxburghii genome, we conducted genome assembly and phasing using HiFiasm14 (v0.23.0) with PacBio HiFi reads under Hi-C mode parameters (-s 0.55 for haplotype similarity threshold; -D 5 for kmer filter threshold), generating two phased haplotype contig assemblies. Redundant and low-quality sequences were removed using Purge_Dups15 (v1.2.6) with stringent parameters (-f 0.7 for sequence retention threshold). Subsequent error correction was conducted using Pilon16 (v1.24) with Illumina paired-end data, employing diploid-optimized parameters. To further elevate the assembly to the chromosomal level, Hi-C data were used to cluster, order, and orient the contigs with ALLHiC17 (v0.9.8) using the following parameters: -k 80 for cluster size cutoff and --nonunique 0.7 for mapping tolerance threshold. This process generated 20 pseudochromosomes for each haplotype (A and B) (Fig. 2), with mounting rates of 99.83% and 98.52%, and Scaffold N50 was 104.19 Mb and 105.51 Mb, respectively (Table 1).

Genome annotation

For repeat sequence annotation, we used RepeatMasker18 (v4.1.2) and RepeatModeler19 (v2.0.5) for homologous prediction and de novo prediction, respectively. Additionally, sequences predicted as “Unknown” repeat were further analyzed using DeepTE20 (v1.0). By integrating the predicted results and removing redundancy, we determined that repeat sequences accounted for 76.54% and 76.68% of the two haploid genomes (Table 2 and Table 3).

Gene structure prediction integrates de novo gene prediction, homologous gene prediction, and transcript retrieval-based gene prediction. Firstly, Augustus21 (v4.0.0) was used for de novo gene prediction, HISAT222 (v2.2.1) and StringTie23 (v3.0.0) were used for transcriptome-based prediction, and TransDecoder24 (v5.4.0) was applied to predict open reading frames. Furthermore, Exonerate25 (v2.2.0) was used to align homologous peptides from several nearby species, including Dcatenatum catenatum (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/all/GCF/001/605/985/GCF_001605985.2_ASM160598v2/), Phalaenopsis equestris (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/all/GCF/001/263/595/GCF_001263595.1_ASM126359v1/), Gastrodia elata (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/all/GCA/016/760/335/GCA_016760335.1_NIFOS_GasEla_1.0/), and Apostasia shenzhenica (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/all/GCA/002/786/265/GCA_002786265.1_ASM278626v1/), to the assembled genome and obtained homolog prediction results. Finally, the Geta pipeline (https://github.com/chenlianfu/geta) was used to intergrate the gene models, and quality checks were conducted using HMMScan26 (v3.3.2) and BLASTp27 (v1.0.0) to screen for highly credible genes. In total, we successfully annotated 26,239 and 26,324 coding genes in the two haplotypes (Table 1). Additionally, we employed standardized workflows for gene function annotation. DIAMOND BLASTp27 (v1.0.0) was used to compare the predicted protein sequences against public databases, including UniProt, NR, GO, and KEGG, with an E-value cutoff of 1e-528. This approach enabled us to obtain information regarding gene functions and the metabolic pathways in which these genes are involved.

Phylogenetic analysis

We conducted the phylogenetic tree and divergence time between A. roxburghii and 15 other plants, including 4 orchids (P. equestris29, D. catenatum30, G. elata31, and A. shenzhenica32), 1 species of Liliaceae (Asparagus officinalis33), 6 monocotyledon plants (Brachypodium distachyon34, Oryza sativa35, Sorghum bicolor36, Ananas comosus37, Musa acuminata38, and Spirodela polyrhiza39), 3 dicotyledon plants (Populus trichocarpa40, Arabidopsis thaliana41, and Vitis vinifera42), and one basal angiosperm (Amborella trichopoda43). Orthologous gene families were identified across all species using OrthoFinder44 (v3.0.1b1) with all-vs-all BLASTp alignment (e-value ≤ 1e-5). Comparative analysis of five orchid species revealed 8,111 conserved gene families shared among all members, while 1,060 gene families were uniquely retained in A. roxburghii (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, the 343 single-copy orthologous gene sequences were aligned using MUSCLE45 (v5.2). Conserved blocks were selected through Gblocks46 (v0.91b), with optimal amino acid substitution models determined by ProtTest47 (v3.4.2). A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed in RAxML48 (v8.2.12) with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Divergence times were subsequently estimated employing the MCMCTree module in PAML49 (v4.10.3) package under a relaxed molecular clock model. To calibrate the molecular clock, we applied fossil calibration constraints at four key nodes, with all calibration times obtained from the TimeTree50 database (http://timetree.org/), including the divergence time between A. officinalis and P. equestris (92.5–118.5 million years ago, Mya), O. sativa and B. distachyon (41.5–62.0 Mya), M. acuminata and O. sativa (103.2–117.1 Mya), and the basal angiosperm node represented by A. trichopoda and A. thaliana (179.9–205.0 Mya). Finally, evolutionary analyses of gene family expansion and contraction were performed using CAFÉ 551, identifying 2,100 expanded and 2,120 contracted gene families.

Phylogenetic and comparative genomics analyses of the A. roxburghii haplotype A genome. (a) The number of shared and unique gene families in A. roxburghii and four Orchidaceae species. (b) Phylogenetic tree showing the evolutionary relationship of A. roxburghii and 15 other plants. Expansion (green) and contraction (red) of gene family numbers are shown. Predicted divergence times (Mya, million years ago) are labelled in black at other intermediate nodes.

Data Record

The raw sequencing data52,53 generated in this study have been deposited in both the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) at the National Genomics Data Center (CNCB-NGDC) under accession CRA021929 and the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession SRP605955. The two haplotype genome assemblies have bee deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under the accession numbers GCA_976986765 for Haplotype A and GCA_976986775 for Haplotype B54,55. The genome assembly and annotation data56 had been submitted at the Figshare database at the following link: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Genome_of_Anoectochilus_roxburghii/28163756.

Technical Validation

To evaluate the quality of the genome assembly, we aligned Illumina short reads to the reference genome using BWA57 (v0.7.17), achieving a high mapping rate of 99.99%. Genome completeness was further assessed through BUSCO10 (v2.2) analysis against the embryophyta_odb10 database. The results demonstrated completeness, with 93.5% and 92.9% of core conserved plant genes identified in the two haplotype assemblies, respectively.

To validate the reliability of haplotype-resolved genome assembly, we aligned HiFi reads to the merged haplotype assemblies using minimap258 (v2.24) with mapping parameters (-N 0) to retain only primary alignments. Statistical analysis revealed that among the 10,149,730 reads successfully mapped to both haplotypic chromosome sets, 49.55% (5,028,978 reads) showed specific alignment to haplotype A chromosomes, while 49.21% (4,994,602 reads) specifically aligned to haplotype B chromosomes. Notably, only 1.24% (126,150 reads) exhibited cross-mapping between the two haplotypic chromosome sets, demonstrating high inter-haplotype sequence specificity. For anchoring quality assessment, we performed Hi-C data alignment to the reference genome. The contact matrix revealed significantly stronger intra-chromosomal interaction signals compared to inter-chromosomal interactions (Fig. 2b and Fig. 2c). Notably, the interaction patterns showed prominent diagonal distribution within chromosomes, providing additional validation for the accuracy of genome assembly and scaffolding.

Code avaliability

The Geta pipeline is publicly available under the MIT License at GitHub: https://github.com/chenlianfu/geta. All parameters used in this study are described in the Methods.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data52,53 generated in this study are available in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) at the National Genomics Data Center (CNCB-NGDC) under accession number CRA021929 and in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number SRP605955. The two haplotype genome assemblies have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under the accession numbers GCA_976986765 for Haplotype A and GCA_976986775 for Haplotype B54,55. And the genome assembly and annotation data56 are available in the Figshare repository at https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Genome_of_Anoectochilus_roxburghii/28163756.

References

Ye, S., Shao, Q. & Zhang, A. Anoectochilus roxburghii: A review of its phytochemistry, pharmacology, and clinical applications. J Ethnopharmacol 209, 184–202, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2017.07.032 (2017).

Fu, L. et al. Dietary Supplement of Anoectochilus roxburghii (Wall.) Lindl. Polysaccharides Ameliorates Cognitive Dysfunction Induced by High Fat Diet via “Gut-Brain” Axis. Drug Des Devel Ther 16, 1931–1945, https://doi.org/10.2147/dddt.S356934 (2022).

Cui, S. C. et al. Antihyperglycemic and antioxidant activity of water extract from Anoectochilus roxburghii in experimental diabetes. Exp Toxicol Pathol 65, 485–488, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etp.2012.02.003 (2013).

Liu, Y. T. et al. The purification, structural characterization and antidiabetic activity of a polysaccharide from Anoectochilus roxburghii. Food Funct 11, 3730–3740, https://doi.org/10.1039/c9fo00860h (2020).

Guo, Y. L. et al. Therapeutic effects of polysaccharides from Anoectochilus roxburghii on type II collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Int J Biol Macromol 122, 882–892, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.015 (2019).

Guo, Y. L. et al. Quantitative determination of multi-class bioactive constituents for quality assessment of ten Anoectochilus, four Goodyera and one Ludisia species in China. Chin Herb Med 12, 430–439, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chmed.2020.07.002 (2020).

Bin, Y. L. et al. Three new compounds from Anoectochilus roxburghii (Wall.) Lindl. Nat Prod Res 37, 3276–3282, https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2022.2070746 (2023).

Wang, H. Z. et al. Induction, Proliferation, Regeneration and Kinsenoside and Flavonoid Content Analysis of the Anoectochilus roxburghii (Wall.) Lindl Protocorm-like Body. Plants (Basel) 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11192465 (2022).

Wang, L. P. et al. Effect of Anoectochilus roxburghii flavonoids extract on H(2)O(2) - Induced oxidative stress in LO2 cells and D-gal induced aging mice model. J Ethnopharmacol 254, 112670, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2020.112670 (2020).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 (2015).

Hesse, U. K-Mer-Based Genome Size Estimation in Theory and Practice. Methods Mol Biol 2672, 79–113, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-3226-04 (2023).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 (2011).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun 11, 1432, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14998-3 (2020).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat Methods 18, 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021).

Guan, D. F. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 36, 2896–2898, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa025 (2020).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9, e112963, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 (2014).

Zhang, X., Zhang, S., Zhao, Q., Ming, R. & Tang, H. Assembly of allele-aware, chromosomal-scale autopolyploid genomes based on Hi-C data. Nat Plants 5, 833–845, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0487-8 (2019).

Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics Chapter 4, Unit 4.10, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s05 (2004).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117, 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Yan, H., Bombarely, A. & Li, S. DeepTE: a computational method for de novo classification of transposons with convolutional neural network. Bioinformatics 36, 4269–4275, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa519 (2020).

Stanke, M. & Morgenstern, B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Res 33, W465–467, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki458 (2005).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 12, 357–360, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3317 (2015).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol 33, 290–295, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3122 (2015).

Maurer-Alcalá, X. X. & Kim, E. TIdeS: A Comprehensive Framework for Accurate Open Reading Frame Identification and Classification in Eukaryotic Transcriptomes. Genome Biol Evol 16, https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evae252 (2024).

Slater, G. S. & Birney, E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 6, 31, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-6-31 (2005).

Wilde, J. T., Springs, S., Wolfrum, J. M. & Levi, R. Development and Application of a Data-Driven Signal Detection Method for Surveillance of Adverse Event Variability Across Manufacturing Lots of Biologics. Drug Saf 46, 1117–1131, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-023-01349-6 (2023).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 12, 59–60, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3176 (2015).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. Fast Genome-Wide Functional Annotation through Orthology Assignment by eggNOG-Mapper. Mol Biol Evol 34, 2115–2122, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx148 (2017).

Cai, J. et al. The genome sequence of the orchid Phalaenopsis equestris. Nat Genet 47, 65–72, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3149 (2015).

Zhang, G. Q. et al. The Dendrobium catenatum Lindl. genome sequence provides insights into polysaccharide synthase, floral development and adaptive evolution. Sci Rep 6, 19029, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19029 (2016).

Bae, E. K. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the fully mycoheterotrophic orchid Gastrodia elata. G3 (Bethesda) 12, https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkab433 (2022).

Zhang, G. Q. et al. The Apostasia genome and the evolution of orchids. Nature 549, 379–383, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23897 (2017).

Harkess, A. et al. The asparagus genome sheds light on the origin and evolution of a young Y chromosome. Nat Commun 8, 1279, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01064-8 (2017).

Initiative, I. B. Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature 463, 763–768, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08747 (2010).

Kawahara, Y. et al. Improvement of the Oryza sativa Nipponbare reference genome using next generation sequence and optical map data. Rice (N Y) 6, 4, https://doi.org/10.1186/1939-8433-6-4 (2013).

Cooper, E. A. et al. A new reference genome for Sorghum bicolor reveals high levels of sequence similarity between sweet and grain genotypes: implications for the genetics of sugar metabolism. BMC Genomics 20, 420, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-5734-x (2019).

Ming, R., Wai, C. M. & Guyot, R. Pineapple Genome: A Reference for Monocots and CAM Photosynthesis. Trends Genet 32, 690–696, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2016.08.008 (2016).

Liu, X. et al. The phased telomere-to-telomere reference genome of Musa acuminata, a main contributor to banana cultivars. Sci Data 10, 631, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02546-9 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. The Spirodela polyrhiza genome reveals insights into its neotenous reduction fast growth and aquatic lifestyle. Nat Commun 5, 3311, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4311 (2014).

Hofmeister, B. T. et al. A genome assembly and the somatic genetic and epigenetic mutation rate in a wild long-lived perennial Populus trichocarpa. Genome Biol 21, 259, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02162-5 (2020).

Wang, B. et al. High-quality Arabidopsis thaliana Genome Assembly with Nanopore and HiFi Long Reads. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 20, 4–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2021.08.003 (2022).

Liu, R. et al. Genome Assembly and Transcriptome Analysis of the Fungus Coniella diplodiella During Infection on Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. Front Microbiol 11, 599150, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.599150 (2020).

Albert, V. A. et al. The Amborella genome and the evolution of flowering plants. Science 342, 1241089, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1241089 (2013).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol 20, 238, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y (2019).

Edgar, R. C. Muscle5: High-accuracy alignment ensembles enable unbiased assessments of sequence homology and phylogeny. Nat Commun 13, 6968, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34630-w (2022).

Castresana, J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 17, 540–552, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334 (2000).

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R. & Posada, D. ProtTest 3: fast selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics 27, 1164–1165, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr088 (2011).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 (2014).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol 24, 1586–1591, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm088 (2007).

Kumar, S. et al. TimeTree 5: An Expanded Resource for Species Divergence Times. Mol Biol Evol 39, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msac174 (2022).

Mendes, F. K., Vanderpool, D., Fulton, B. & Hahn, M. W. CAFE 5 models variation in evolutionary rates among gene families. Bioinformatics 36, 5516–5518, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1022 (2021).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP605955 (2025).

Xu, W. et al. Genome assembly and annotation of Anoectochilus roxburghii. Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA021929 (2025).

European Nucleotide Archive https://identifiers.org/insdc.gca:GCA_976986765 (2025).

European Nucleotide Archive https://identifiers.org/insdc.gca:GCA_976986775 (2025).

Xu, W. et al. Genome of Anoectochilus roxburghii. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28163756.v2 (2025).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698 (2010).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Fuxiaquan National Independent Innovation Demonstration Zone collaborative innovation platform project of Key technology of production of Fujian characteristic authentic medicinal materials (Fuzhou science and technology plan project No.2023-P-005). Fujian Province Science and Technology Department project (2022Y0037, 2024L3013); Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2024J01121); Fujian Provincial Health Commission science and technology plan project (Fujian Provincial Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Program in major research projects for young and middle-aged people, 2023ZQNZD017); School management project of Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (XJC2023011); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32160142), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (No. 2023GXNSFDA026034), Sugarcane Research Foundation of Guangxi University (No. 2022GZA002), and State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-bioresources (SKLCUSA-b202302). We acknowledged the support from National-Local Joint Engineering Research Center for Molecular Biotechnology of Fujian & Taiwan TCM, and high-level key discipline of Clinical Traditional Chinese Pharmacy from National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Haifeng Wang, Xuequn Chen, Zehao Huang, and Wei Xu conceived and designed the project. Wen Xu and Min Gao performed data analyses. Min Gao wrote the manuscript. Haifeng Wang and Wen Xu revised the manuscript. Rong Wang and Xun Zhang collected the experimental materials. Zhipeng Hong and Yu Lin offered suggestions for the research. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, W., Gao, M., Wang, R. et al. A haplotype-resolved genome assembly of Anoectochilus roxburghii. Sci Data 12, 1894 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06181-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06181-4