Abstract

In recent years, the energy generated by the salinity gradient has become a subject of growing interest as a source of renewable energy. One of the most widely used processes is reverse electrodialysis (RED), based on the use of ion exchange membranes and Faradaic electrodes. However, the use of real salt solutions containing mixtures of divalent and monovalent ions in the RED process results in a significant loss of recovered power, compared with salt solutions containing only monovalent ions. From an original point of view, in this work we study and explain the influence of divalent ions and complex solutions in reverse electrodialysis devices equipped with capacitive electrodes with a single membrane (CREDSM). We show that CREDSM mitigates the impact of divalent ions. From a quantitative point of view, the power recovered in a Faradaic cell drops by more than 75\(\%\) when the solutions contain 50 \(\%\) molar fraction of divalent ions and by 33 \(\%\) when the solutions contain 10 \(\%\) molar fraction of divalent ions. For similar low-cost membranes with fairly low selectivity, recovered power drops by only 34 \(\%\) when solutions contain 60\(\%\) moles of divalent ions in CREDSM. We show that only the membrane potential, which makes up half of the cell’s open circuit potential, is affected. The potential of capacitive electrodes which counts for half of the potential cell does not decrease in the presence of divalents. For the same membrane under the same conditions, we estimate a loss of 62\(\%\) in a RED device Furthermore, the membrane is not poisoned by divalent ions because we periodically change the electrical current direction, by means of switching the feed waters. CREDSM devices do not show any variation in membrane resistance or membrane selectivity. The techno-economic analysis suggests further valorization of salinity gradients in industrial operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the face of global environmental challenges and the looming threat of persistent climate change1,2, there is a growing demand for a decisive shift towards alternative and sustainable energy sources to mitigate these issues3,4,5. Despite the impressive progress of solar and wind energy, the diversification of renewable energy resources remains a complex objective. In this context, the exploitation of blue energy generated by the mixing of solutions with varying salinities presents a promising avenue for exploration6,7,8. Considering factors such as viability, sustainability, and reliability, the potential of blue energy is estimated to generate more than 600 TWh per year9, which is equivalent to approximately 2.5\(\%\) of the global electricity consumption in 2021. These promises have led European Commission to recognize blue energy as a renewable energy source for the past 2 years. However, it’s worth pointing out that this technology is still confined to research, even if a few industrial pilots have existed, exist or are under construction10.

Introduced by Pattle in the early 1950s11 and developed as an energy production method by Loeb12, Reverse Electrodialysis (RED) stands out as one of the most promising methods for harnessing blue energy13,14. RED devices capitalize on the Donnan potential difference across ion exchange membranes positioned between solutions of differing salinities15,16. This osmotic phenomenon propels ions to migrate from concentrated to diluted solutions8,17. By leveraging selective membranes, an ionic flux is established18. In a standard RED setup, the conversion of this ionic flux into electronic flux is achieved through Faradaic electrodes that undergo redox reactions19.

Post et al. reported in 2009 the impact of multivalent ion mixing on energy performance of RED system20. They observed a significant stack voltage drop, due to the presence of multivalent ions. The cell potential drops by \(20\%\) (from 0.85 V to 0.6 V) when the dilute solution changes from 3 mmol/L sodium chloride to 3 mmol/L sodium chloride and 4 mmol/L magnesium sulphate while the concentrate consisted of 0.45 mol/L sodium chloride and 0.05 mol/L magnesium sulphate is kept constant.

Similarly, Vermaas et al.1 reported that the introduction of MgSO\(_4\) in feed solutions in RED systems led to a reduction in stack voltage, leading to a detrimental power density decrease of more than 50 \(\%\) in the situation when a molar percentage of 25\(\%\) or more was accounted for by MgSO\(_4\) for both feed water streams. The total salt concentration of the concentrated solution was 0.508 M in all cases,whereas the total salt concentration of the dilute solution was always 0.017 M. The remaining amount of dissolved salt was NaCl. The negative effect due to the presence of multivalent ions is confirmed in various research works21,22.

To go beyond lab-scale experiments, pilot scale experiments were carried out with real-world solutions. All the works report a significant power performance drop of over 50\(\%\) due to the presence of multivalent ions23,24,25. Veerman et al.2 studied a RED module for salinity gradient energy extraction made of 20 membranes pairs of FKS-75 and FAS-75. When only sodium chloride was included in the feed stream of typical composition of 0.5 M for the artificial sea water and 0.02 M for the artificial river water , the harvested power density was equal to 0.743 W m\(^{-2}\) of membranes. It decreases to 0.5 W m\(^{-2}\) when 0.06 M is added to the more concentrated brine and 0.0024 M to the more dilute one. This corresponds to a power decrease of 33 \(\%\) when a 10\(\%\) molar fraction of MgCl\(_2\) is added. Using such an approach, Tedesco et al. built a pilot plant with 400 m\({^2}\) of low cost membranes (selectivity 0.6) which reaches almost 350 W of gross power capacity using real brine and brackish water26. This corresponds to a power density of 0.875 W per m\({^2}\) of membranes. Tedesco et al. pointed out a significant power diminution due to the divalent ions presence in seawater. In fact, the produced power is doubled when divalent-free artificial solutions are used26. Following the techno-economic analysis of Giacalone et al.27 with a power density of 0.875 W/m\({^2}\) of membranes, we estimate a cost of 1200 € per MWh if the brackish water is filtered. This cost remains high compared to the solar energy (40€ per MWh) and wind energy (120€ per MWh). In fact, one of the major cause of the RED system’s high cost relies in the low power density production, which is significantly reduced in real-life feed solution due to the presence of divalent ions, particularly Mg\(^{2+}\) and Ca\(^{2+}\). Divalent ions have a negative effect on RED. The second reason why the open circuit potential is lower is that the ratio of the activity coefficients of divalent ions is lower than that of divalent ions. The activity of monovalent ions is generally higher than that of multivalent ions, and this effect is more pronounced in seawater due to the higher ionic strength of the solution.

Four major process are at the origin of this decrease28: decrease of the open circuit potential, uphill transportation, increase of the resistance of the membrane, and loss of the selectivity of the membrane. From a thermodynamic point of view, the membrane potential decreases when divalent ions are introduced. Firstly, the membrane potential scales as the valence of the ion at the power minus one. Secondly, the ratio of the activity coefficients of divalent ions is lower than that of divalent ions. Because of the valence of the ion, the electromotive force of the monovalent ions is larger than that of the divalent ions. This causes a reversed transportation of multivalent ions against the concentration gradient called uphill transport. The salinity difference is decreased and the harvested power is lower. Uphill transport of divalent ions Mg\(^{2+}\) was evidenced experimentally by Avci et al. using Ion Chromatography analysis conducted on inlet and outlet streams of the RED system29,30.

Additionally, multivalent ions have larger radii, charges and dehydration energies. Their transport across membranes is slowed down, leading to the trapping of multivalent ions in the membrane due to electrostatic bridging of ionic charges with fixed membrane charges. As a result, the electrical resistance of the membrane increases and selectivity decreases. The decrease in selectivity is aided by another phenomenon. Multivalent ions drag along co ions with the same charge as the membrane, reducing the membrane’s selectivity31. Fontananova et al. conducted systematic studies to evaluate the common ions as Mg\(^{2+}\), Ca\(^{2+}\) and SO\(_4^{2-}\)32. They identified a strong negative effect of divalent ions on both ionic resistance and permselectivity of ion exchange membranes. Oh et al. confirmed that as divalent ions of small hydrated radius presents higher electrical resistance in CEMs33. Gomez-Coma et al. studied experimentally the effect of multivalent ion species on membrane resistance34. Other possibilities for reducing membrane fouling and avoiding loss of selectivity are to frequently change the direction of the electric current, for example by applying short electric pulses as reported by Cifuentes-Araya et al.35 or by changing the feed water as reported by Allison36.

To diminish the power density drop, the use of monovalent ion selective membranes is proposed and suggested in numerous works37,38,39. However, considering the complexity and the high cost of these membranes, an efficient and cost-effective method is required to mitigate the multi-valent ion impact on RED system performance. The second method is to apply a coating with an opposite fixed charge to that of the membrane but once again the cost is not commensurate with the results obtained40.

In this article, we study the role of divalent ions in a single-membrane capacitive reverse electrodialysis cell (CREDSM). To the best of our knowledge, this study has never been carried out in such conditions. The originality of our work is to show and explain that the presence of divalent ions in brines affects the performance of CRED-type devices less than RED-type devices. From a quantitative point of view, the power recovered in a Faradaic cell drops by more than 75\(\%\) when the solutions contain 50\(\%\) molar fraction of divalent ions (see Figure 7 in Vermaas’ work1) and by 33\(\%\) when the solutions contain 10\(\%\) molar fraction of divalent ions (see the results of Veerman2).

For similar low-cost membranes with fairly low selectivity, recovered power drops by only 34\(\%\) when solutions contain 60\(\%\) moles of divalent ions in CREDSM-type devices. We propose an explanation for this better performance. According to theoretical and experimental results, we identify uphill effect as the only impact factor for the power loss of CREDSM system in presence of divalent ions. Furthermore, CREDSM cells used with a single membrane have little effect on their cell potential because the cell potential is the sum of the cell potential and the electrode potential. The latter, purely capacitive, is not affected by ions. This point has less impact for a RED cell, which contains several membranes for only two faradic electrodes. The membrane poisoning related issues, including additional membrane voltage drop and cell resistance increase, are suppressed by the reversal of water chambers in CREDSM system. Before concluding, we present a life cycle assessment and techno-economic analysis to gauge the extent of progress needed to transition blue energy into viable renewable energy. Additionally, we examine specific scenarios where RED devices demonstrate effectiveness and commercial viability.

Results

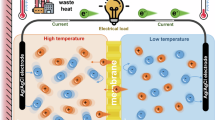

Working principle of a capacitive cell with a single membrane

To enhance cost-effectiveness of RED devices, Vermaas et al. suggested the integration of capacitive electrodes within reverse electrodialysis systems (CRED)41. They showed that the power density of CRED is roughly the same when compared to stacks with conventional Ti/Pt electrodes and the Fe(CN)\(_6^{3-/4-}\) electrode rinse system.41.Equipping a RED cell which contains several membranes with capacitive electrodes does not produce more energy. This substitution obviates oxidation-reduction reactions at the electrodes, yielding a more ecologically friendly and economical approach42,43,44,45.

Following this approach, Zhu et al.46 pioneered the development of capacitive concentration cells employing a single selective membrane CREDSM. Remarkably, they achieved an average power density of 0.95 W m\(^{-2}\) for salinity levels of 0.017 M and 0.513 M in fresh water and salt water, respectively. These results stand in stark contrast to the performance of Capmixing devices (producing less than 400 mW m\(^{-2}\))43,47, and they are comparable to outcomes from RED experiments with faradaic electrodes involving the same salinity gradients48.

In a similar vein, we have pursued an analogous approach, devising a novel cell configuration comprised of a single selective membrane and two cost-effective capacitive electrodes49. This design yielded a net power density output of 2 W m\(^{-2}\), achieved with a salinity ratio of 300 (0.017 M and 5.13 M) and of 5.26 W m\(^{-2}\) without boosting strategy50. All these results have been obtained in absence of divalent ions.

Let us go deeper in the working principle of these devices. The general principle of the CREDSM is illustrated in Figure 7 (Cell preparation, see Methods). A cationic ion-exchange membrane (CEM) is placed in middle of the cell between two compartments of different salinity. This membrane allows the passage of cations and blocks the anions and water molecules51,52. Thanks to this selectivity, an electrical potential difference appears between these two solutions of different salinity. In open-circuit cases, the cell voltage \(E_{OCV}\) is the sum of the Donnan potential \(E_{mem}\) and of electrode potentials \(E_{elec}\). The Donnan potential is given by the Nernst equation, corrected for the activity of the feed waters and the apparent permselectivity of the non-perfect membrane. It is given by :

where \(E_{m}\) represents the electromotive force across the membrane (in volts, V),R stands for the universal gas constant (8.314 J mol\(^{-1}\) K\(^{-1}\)), T is the temeperature, \(z_i\) represents the valence of the ionic species i (dimensionless), F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C mol\(^{-1}\)), and \(a_i\) signifies the activity of ionic species i in the feed water (in molarity, M).\(\alpha \) is the selectivity of the membrane, \(\alpha =1\) corresponds to a perfect selective membrane. In the situation of a cation exchange membrane, \(\alpha =1\) corresponds to a membrane that allows the free passage of cations but blocks all the anions. The subscripts 1 and 2 indicate the side of the membrane. Equation 1 illustrates that a salinity ratio of monovalent ions (such as Na\(^{+}\), Cl\(^{-}\)) results in twice the voltage generated by an equivalent salinity ratio of divalent ions (such as Mg\(^{2+}\), SO\(_{4}\) \(^{2-}\)), assuming constant activities and apparent membrane permselectivity.

\(E_{elec}\) results from the ion adsorption on the electrodes and depends upon the debye lenght and thus upon the value of the local salt concentration. When the circuit is closed, the potential drop between the two electrodes includes the ohmic ionic dissipation both in the membrane and in the electrolyte, as well as the non-ohmic dissipation in the polarization layers built up around the membrane and the electrode. The closing of the circuit also involves the ohmic potential difference in the load resistance and the capacitive potential jump at the electrodes. The presence of capacitance causes the electric current to decay over time. When the capacitor is fully charged, the potential difference across its terminals balances the membrane potential \(E_{mem}\) and the potential created by the adsorbed layers \(E_{elec}\). As a result, the produced electric current stops. It is then necessary to switch the fresh water and salt water supplies in order to reverse the membrane and electrode potential to unblock the electricity production. This generates an electric current in the opposite direction.

Divalent ion mixture influence on cell voltages

We will study a highly selective membrane, Nafion (Nafion\(^{TM}\) HP, Chemours). We will then display some data on two others less expensive and less selective commercial membranes, Fumasep (FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) FS720, Fumatech) and sPEEK (FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) E-620 (K), Fumatech).

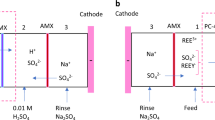

In order to perform insight studies of the impact of divalent ion mixing on electrical voltages, we conducted measurements to study separately the membrane voltage \(E_{m}\) and capacitive electrode related voltage \(E_{OCV-c}\). This is realized by open-circuit voltage (OCV) measurements both in capacitive and faradaic cells. In the capacitive situation, \(E_{OCV-c}\) is twice the sum of the membrane potential \(E_{m}\) and of the electrode potentials \(E_{elec-c}\). In the faradaic situation, \(E_{OCV-f}\) is the sum of the membrane potential \(E_{m}\) and of the Ag/AgCl electrode potentials \(E_{elec-f}\). \(E_{elec-f}\) is measured separately in a simple set-up containing two electrodes immersed in two beakers containing solutions of different concentration and linked by a salt bridge. As \(E_{m}\) does not depend upon the nature of the electrode, it is then possible to deduce \(E_{elec-c}=E_{OCV-c}-E_{m}\) from the measurement of the open circuit potential performed on a cell equipped with the membrane and capacitive electrodes. A detailed explanation for the voltage measurement and calculation method is available at Methods section.

We carried out a series of 16 experiments with NaCl solutions mixed with MgCl\(_2\) and CaCl\(_2\) solutions. The compositions of the different solutions used are given in the Table 7. Compared to solutions with only NaCl, part of the NaCl was replaced by MgCl\(_2\) or CaCl\(_2\), in order to maintain the molarity of the inflowing feed (and hence the conductivity, to a certain degree) constant. The results obtained concerning different electrical voltages under the influence of divalent ion mixing are displayed in the Table 1, 2 and Figure 1.

Electrical voltage over membrane \(E_{m}\) and over capacitive electrodes \(E_{elec-c}\) as a function of NaCl molar fraction. (a), (b) and (c) represents the variation of voltage of mixing between NaCl and CaCl\(_2\) for salinity ratio of 100, 30 and 10, respectively. (d) represents the mixing case of NaCl and MgCl\(_{2}\) for a salinity ratio of 30. As molar fraction of divalent ions gets higher, \(E_{m}\) drops significantly while \(E_{elec-c}\) remains constant.

Data obtained in the absence of divalent ions are comparable to measurements obtained previously in the literature49. In these situations, \(E_m\) corrected by measured Ag/AgCl electrode potential are 0.107, 0.074 and 0.05 V for Ra value of 100, 30 and 10 respectively. The membrane potential is given by \(E_{mem}=\alpha \frac{RT}{F}ln(\frac{\gamma _H c_H\gamma _H}{\gamma _L c_L\gamma _L})\).\(\alpha \) is the selectivity of the membrane, \(\alpha =1\) corresponds to a perfect selective membrane, that allows the free passage of cations but blocks anions. Activity coefficients \(\gamma _H\), \(\gamma _L\) are obtained with the extended Debye-Hückel equation .

where I is the ionic strength \(I=0.5\Sigma z_i^2C_i\) and A stands for the diameter of the hydrated ion (in pm). Some values for A are: Na\(^{+}\): 450 pm, Mg\(^{2+}\): 800 pm, Ca\(^{2+}\): 600 pm. Based on previous values, the selectivities \(\alpha \) are calculated to be 0.99, 0.99 and 0.99 for Ra value of 100, 30 and 10 respectively.

In presence of divalent ions, the membrane voltage decreases compared with solutions composed of pure mono-valent ions, as illustrated in Figure 1. As the molar fraction of divalent ions increases, the membrane voltage shows significant further decrease. For a fixed salinity ratio of 100 (30 or 10, respectively) , the membrane potential decreases from 107 mV to 86 mV (75 mV to 63 mV in the case of ratio 30, and 50 mV to 23 mV in the case of ratio 10, respectively) for a molar fraction of 0.4 of CaCl\(_{2}\) and a total salt concentration of 1.71 mol L\(^{-1}\) (0.51 mol L\(^{-1}\), 0.17 mol L\(^{-1}\), respectively). The nature of divalent ions does not change \(E_m\) and \(E_{elec}\). There are no major difference between the case of MgCl\(_2\) and CaCl\(_2\). In presence of MgCl\(_2\), the drop of potential is comparable to that in presence of CaCl\(_2\). For a NaCl salt fraction of 0.4, Ra=30, the membrane potential is equal to 54 mV in presence of MgCl\(_2\) and to 57 mV in presence of CaCl\(_2\). We have supplemented this series of measurements with membrane potential measurements when divalents are only present in the dilute solution (see Table 2).

The potential of the electrodes behaves differently (see last column of Table 1). It seems less affected than membrane potential by the presence of divalent ions. It depends little of the amount of divalent added and on the nature of the ions. These results have important implications for cell potential. The cell potential consists the sum of the electrode and membrane contribution. While the molar fraction of NaCl drops from 1 to 0.4, the voltage contribution of membranes \(E_m\) shows a significant drop of 19.6%, 27.0% and 54.0% for salinity ratio Ra of 100, 30 and 10, respectively. In the same situations, the voltage contribution of electrodes \(E_{elec-c}\) shows a drop of 3%, 16% and 12.4% for salinity ratio Ra of 100, 30 and 10, respectively. While the molar fraction of NaCl drops from 1 to 0.4, this induces for a capacitive cell a decrease of the total cell voltage \(E_{OCV-c}\) of 12.8%, 23.4%, and 33.6% for salinity ratio Ra of 100, 30 and 10, respectively. This decrease is thus much less important than the one occurring for the membrane potential.

We complete this study with some measurements established on less selective membranes. The measured features are displayed on Table 4. The FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) FS720 and FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) E-620 (K) membrane have a lower initial selectivity than the Nafion membrane respectively 0.87 and 0.74 . When divalents are added, the OCV potential measured in a CREDSM falls by a similar amount to that of the Nafion membrane respectively 26.5 \(\%\) and 26.4 \(\%\) compared to 30 \(\%\).

To conclude this paragraph, it should be noted that these figures are achieved in a cell where fluxes are permanently exchanged, which is not the case in faradaic cells. We’ll come back to this point later.

Divalent ion mixture influence on electrochemical properties

In order to characterize changes in cell resistance \(R_{cell}\) and cell capacitance C as a function of the nature of the salt solutions, we carried out impedance spectroscopy measurements (see Methods section). As an equivalent R-C circuit can be established for the capacitive cell, for each solution mixture, it is possible to measure the corresponding inner cell resistance and its capacitance by using the Nyquist plot plotted by the PEIS method. Here, by using the impedance result measured at 10 mHz, we characterized R and C for different divalent mixing scenarios. The electrochemical measurement results are illustrated in the Table 3 for two different mixing scenarios: NaCl-CaCl\(_2\) and NaCl–MgCl\(_2\) with a fixed salinity ratio of 30. It is clear that while the quantity of divalent salts in the mixing is increased, the cell resistance decreases slightly. We believe that this is related to the increase of molar concentration of chloride ions inside the solution. This behavior is also verified by Fumasep-type membranes. We note no increase of the cell resistance in all the cases which suggests that the membrane resistance does not increase much.

Divalent ion mixture influence on energy performance

Power density measurement curves. (a) Instantaneous voltage measurement as a function of time for a mixing solution of NaCl and CaCl\(_2\) of different fractions. A load resistor of 10 \(\Omega \) is connected to the capacitive cell. The voltage drop on the load resistor \(E_{load}\) is measured by a potentiostat. As the solution reversal is realized for a fixed period \(T_s\) = 45 s, an alternating electrical signal is measured. (b) The instantaneous power density P dissipated on the load resistor corresponding to the measurement in (a) for a series of mixing fractions. (c) The temporal averaged power density \(P_{gross}\) as a function of load resistance for divalent ion mixing of NaCl and CaCl\(_2\) for a salinity ratio of 30. The solid lines represent the theoretical prediction based on the R-C equivalent circuit. The dots represent the experimental data obtained for a capacitive salinity gradient cell. (d) The temporal averaged power density \(P_{gross}\) as a function of load resistance for divalent ion mixing of NaCl and MgCl\(_2\) for a salinity ratio of 30. The number presented in the legend corresponds to the molar fraction of NaCl.

Power density performance characterization. (a) The temporal averaged power density \(P_{gross}\) as a function of load resistance for artificial NaCl (blue dots) or NaCl (40\(\%\)) - CaCl\(_2\) (60\(\%\)) mixed solution (red dots) of 30 g L \(^{-1}\) vs 1 g L \(^{-1}\). The solid lines represent the theoretical model, the dots represent the experimental results. The result is measured for a CRED system with a FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) FS720 membrane with a effective surface of 2.24 cm\(^2\). The figure in the legend refers to the NaCl molar fraction in the mixing. The power density presents a drop of around 30 \(\%\) in artificial NaCl (40\(\%\)) - CaCl\(_2\) (60\(\%\)) mixed solution of 30 g L \(^{-1}\) vs 1 g L \(^{-1}\). (b) Mean gross Power density measurement \(P_{gross}(t)\) (see definition Equation 3) of a capacitive salinity gradient cell during an operation duration of 500 min for three different cases. Note that while instantaneous power is a periodic signal due to the capacitive process, power averaged over a period is not. Case 1: the use of artificial NaCl (80\(\%\)) - CaCl\(_2\) (20\(\%\)) mixed solution with a salinity ratio of 30 g L \(^{-1}\) vs 1 g L \(^{-1}\)). The membrane used here is Nafion 117 with a load resistor of 10 \(\Omega \). Case 2: the use of production water (equivalent NaCl concentration 107 g L \(^{-1}\)) with a salinity ratio of 30. The membrane used here is Nafion 117 with a load resistor of 10 \(\Omega \). Case 3: the use of artificial NaCl (40\(\%\)) - CaCl\(_2\) (60\(\%\)) mixed solution with a salinity ratio of 30 g L \(^{-1}\) vs 1 g L \(^{-1}\)). The membrane used here is FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) FS720 with a load resistor of 30 \(\Omega \). In all cases, we fix the switching period as \(T_s\) = 45s. The power density variation after 10h of operation is within 6\(\%\).

It is important to characterize the energy performance of the capacitive cell. We will firstly explain the power density characterization method for a simple capacitive cell using pure mono-valent ion based solutions. In general, we connect a load resistor directly to the CREDSM system. We measure the voltage drop on the load resistor \(E_{load} (t)\) as a function of time by using the OCV mode in a pontetiostat, as illustrated in Figure 2a. Based on these measurements, it is possible to determine the instantaneous power density output on the load resistor \(P (t) = \frac{E_{load}(t)^2}{R_{load}}\), as illustrated in Figure 2b.

The mean gross power density \(P_{gross}(t)\), which is the power density without compensating for pumping losses, is a function of time. It is assessed by averaging the signal recorded across the resistance over a time interval of \(T_s\). S denotes the area of the membrane. The expression is as follows:

A priori, \(P_{gross}(t)\) depends on time t. In fact, in all our experiments, this power does not depend on time, as shown in the Figure 3b for a few experiments. Figures 2c ,d show the value of stationary power, which is measured from the first cycle.

It’s noteworthy that these measurements constitute direct assessments that mirror real-world scenarios. To assess the influence of divalent ion mixing in the capacitive cell, we measure the harvesting power in various salinity gradients with different divalent ion mixing fraction. For each mixing case, the experimental results are presented by dots in Figure 2. The measured power densities show classic variations according to the load resistance. Maximum power recovery decreases from 1.15 W m\(^{-2}\) to 0.8 W m\(^{-2}\) (respectively 0.75 W m\(^{-2}\)) when the CaCl\(_2\) (respectively MgCl\(_2\)) proportion in the brine increases from 0 to 60\(\%\). The modeling of the data will be discussed in the following sections.

The same experiments were carried out on the Fumasep (FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) FS720, Fumatech) and sPEEK (FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) E-620 (K), Fumatech) membranes. The results are shown in Figure 3a, some features are given in Table 4. The addition of divalent causes the maximum power to drop. Note that the power values were measured over 8 hours and no variation was measured over time. The power remains constant, as shown in the figure (see Figure 3b). The modeling of the data will be discussed in the following sections.

Membrane poisoning in Faradaic RED cell

In order to be able to compare the CREDSM and RED devices, it is necessary to carry out new experiments on the membranes we use. The effects of divalents are highly membrane-dependent, and it is not possible to be satisfied with the information available in the literature. To do this, it would be possible to compare the power generated. We have not chosen this approach, however, as it would be complex to construct capacitive cells and Faradaic cells with the same efficiency coefficients, i.e. to recover the same share of the maximum accessible potential. To understand the mechanisms involved, we preferred to focus on how divalent ions modify the intrinsic properties of the membrane.

To probe this more precisely, we close the circuit with the Ag/AgCl electrodes on a resistor which value is closed to \(R_{cell}\). An ionic current passes through the membrane during the experiment. This phase lasts 20 minutes. The current remains constant in the case of the Nafion membrane, drops in the case of the FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) FS720 and FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) E-620 (K) membranes . We then measure the membrane potential in the Ag/AgCl cell using the OCV measurement. This measurement slightly disturbs the state of the membrane because it requires a reversal of flow. Two flow reversals are used to limit the impact of the measurement on the results. This allows us to calculate membrane selectivity before and after measurement. \(E_m\) in presence of divalent varies from 57.9 mV to 56.4 mV in the case of Nafion over 20 minutes, from 50 mV to 42 mV in the situation of FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) FS720 and from 42.6 mV to 35 mV in the situation of FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) E-620 (K) . We find that the selectivity of the Nafion membrane is unaffected. The selectivity of the FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) FS720 membrane decreases by 16\(\%\) and the one of FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) E-620 (K) by 17.8\(\%\).

Experiments dealing with real solutions

To complete our study, we designed a series of experiments to test the feasibility of CRED in applications, where complex solution mixtures are used. These imaginary scenarios serve as proxies for some real-life applications, as detailed below, or allow to test some bottlenecks expected in these applications.

In the first scenario (Figure 4a) we consider produced water from an oil well mixing with seawater. Here we used synthetic production water and synthetic seawater prepared in a laboratory from data provided from a field (see composition in53). The obtained power density 0.35 W m\(^{-2}\) was similar to what what was obtained with NaCl solutions at similarly low salinity ratio of around 4. The amount of osmotic energy is low due to the small difference in salinity. We could conclude that although our results show the feasibility of energy harvesting from production water, unaffected by the presence of divalent ions, advantage of further development of this application is site dependent.

In the second scenario we used real water from the evaporation ponds at the Dead Sea, mixed with the same solution diluted by 30 times (Figure 4b). The extreme salinity conditions of this test could be relevant to projects like the Red sea-Dead sea conveyance, or similar. Remarkably, the high power density of over 2 W m\(^{-2}\) indicate the unprecedented feasibility of such application. According to our experimental analysis, the total dissolved salts content in the dead sea solution is on the average 324.9 g L\(^{-1}\). The dominant cation is Mg (62.3 g L\(^{-1}\)), followed by Na (32.2 g L\(^{-1}\)), Ca (27.5 g L\(^{-1}\)) and K (9.3 g L\(^{-1}\)). We demonstrated that even in the case where divalent ions (Mg and Ca presenting around 55\(\%\)) dominate, the measured power density obtained in a capacitive cell is comparable to the value 2.2 W m\(^{-2}\) obtained in a pure solution composed of NaCl salts with similar concentration gradients (300 g L\(^{-1}\) vs. 10 g L\(^{-1}\)) as reported by Wu et al.50.

In the third scenario (Figure 4c) we imagine creation of salt caverns, either for salt mining or for subsequent hydrogen storage. The caverns are created by dissolution in water, of salinity available on site, injected into the salt deposit. The concentrated solution is therefore saturated brine, mostly composed of NaCl 300 g L\(^{-1}\), and the diluted solution is fresh (used) water or river water, replaced here for simplicity by a 1 g L\(^{-1}\) artificial mixture solution of composed of NaCl (40\(\%\)) and CaCl\(_2\) (60\(\%\)). In this case, a maximum power density of 3.2 W m\(^{-2}\) is obtained. The power density shows limited decrease compared with NaCl pure solutions of 300 g L\(^{-1}\) and 1 g L\(^{-1}\), which shows a maximum power density of 4 W m\(^{-2}\) in the capacitive cell. This scenario also resembles that of a facility constructed between the Great Salt Lake, utilizing water from the lake along with treated wastewater, or a facility situated within the Ettore e Infersa saltworks in Marsala (Trapani, Italy). The Italian location provides freshwater from a coastal well and nearly saturated brine26,5427.

In our study, the experiments performed with water production and sea water are close to the result obtained with equivalent monovalent ion based solutions as the divalent ions are of low molar fraction (6.7 \(\%\) in the case of production water and 0.4 \(\%\) in the case of sea water53). For most real sea water solutions, divalent ions are of low molar fraction, as in the example of Mediterranean sea water which contains 3.7\(\%\) of Mg\(^{2+}\) and 1.2\(\%\) of Ca\(^{2+}\) and 33\(\%\) of Na\(^{+}\)27). When it comes to Dead Sea water, it is actually dominated by the presence of divalent ions. However, according to our experimental studies, capacitive system presents minor performance decay in this case. We believe that the same results will be obtained when river water containing high levels of divalent ions is taken into account (see Figure 1d). For example, the Amazon river water contains 2.4\(\%\) of Mg\(^{2+}\) and 15\(\%\) of Ca\(^{2+}\) and 3.1\(\%\) of Na\(^{+}\)27.

We conclude that, within a capacitive cell system, the composition of the brine has a limited impact on performance. We highlight that these performances might be enhanced using an external voltage source50.

Power density curves for real solutions. (a) Power density measurement for the case of synthetic seawater and production water with a salinity ratio of 4. (ESPCI Paris) Power density measurement for the case of Dead sea water with a salinity ratio of 30. (c) The case of salt cavern with highly concentrated sea water corresponding to a pure NaCl salt solution of 300 g L\(^{-1}\) coupled with an artificial river water. The salinity ratio is 300. All the detailed solution composition is available in the method section. In all cases, the switching period is fixed as \(T_s\) = 45 s.

Discussion

To fully understand the mechanisms involved, it is necessary to present a model of the results. The first subsection deals with open-circuit potential measurements. The second subsection of this paragraph deals with power measurements. The last subsection takes advantage of these modelings to explain the measured performances.

Cell open voltage modeling

Theoretical interpretation of the membrane voltage \(E_{m}\) decreases as a function of divalent ion molar fraction. (a) Theoretical prediction (solid lines) and experimental data (dots) of \(E_{m}\) of different salinity ratio Ra of 100, 30 and 10, respectively, for a mixing between NaCl and CaCl\(_2\). (b) Membrane voltage \(E_{m}\) decrease in two different cases: mixture in both concentrated and diluted solutions, and mixture only in the diluted solution. The feed solution used here is a mixture of NaCl and MgCl\(_2\) or NaCl and CaCl\(_2\) with a fixed salinity ratio Ra of 30. Green squares refer to the case where the MgCl\(_2\) is present only in the river water. Black dots refer to the case where NaCl and MgCl\(_2\) are present in both feeding solutions. Red dots refer to the case where NaCl and CaCl\(_2\) are present in both feeding solutions.

The preceding measurements show us that divalent ions affect mainly the value of the cell performance of our device and more precisely the open circuit voltage. At this stage, it’s important to understand which phenomena induce the drop in potential: is it simply due to the uphill effect where divalent ions migrate into the concentrated compartment as a result of their charge, or is it a phenomenon linked to the variation in membrane selectivity and membrane poisoning? Vermaas et al.1has developed a model to quantify the first point, and comparing our data with this model will enable us to answer the question. In their analysis, they propose that the open-circuit equilibrium membrane potential is equal to a potential that cancels out the displacement of divalent ions. This is only possible if a local transfer of matter takes place, inducing a different concentration in the layer of matter near the membrane. More precisely, ion transport across a membrane is a complex phenomenon when monovalent and multivalent ions exist on both sides of an ion exchange membrane. In such situations, ions are exchanged across the membrane to achieve chemical potential equilibrium on both sides. When solutions of NaCl and MgCl are present on either side of a cation exchange membrane (CEM) at varying concentrations but with the same ratio, the electromotive force \(E_{OCV}\) resulting from the difference in concentration of Na\(^{+}\) is greater than that of Mg\(^{2+}\) due to the valence of the ions. We recall that \(E_{OCV}=\frac{\alpha RT}{zF} log \frac{a_{i,1}}{a_{i,2}}\). As a result, Mg\(^{2+}\) ions are transported from the dilute to the concentrated solution, while twice as many Na\(^{+}\) ions move in the opposite direction. This exchange ensures electroneutrality on both sides of the membrane and is described in the literature as uphill transport, corresponding to the movement of Mg\(^{2+}\) against the concentration gradient. Using Equation 1 and assuming that the apparent permselectivity is equal for both ionic species, this stationary situation is reached when the ion activities at either side of the membrane obey:

This leads us to :

J is the molar transport (mol) of Mg\(^{2+}\) towards the seawater compartment, and \(V_1\) and \(V_2\) are the volume of the compartments. Activity coefficients in the lower concentration range are obtained with the extended Debye-Hückel equation.

Figure 5 shows a comparison between the model and membrane potential measurements. An excellent agreement is found between measurements and simulation. This agreement shows that the selectivity of the Nafion membrane is not affected when it is used in a capacitive device where the ionic current changes of direction on each half period. In the case of Nafion, no loss of selectivity was neither measured when the ionic current flowed in the same direction for 20 minutes i.e . In all likelihood, Nafion’s loss of power is limited to the uphill effect.

In the case of membrane with a poisoning effect as FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) FS720, the selectivity is equal to 0.87 in presence of NaCl. The membrane potential drops from 68 to 50 mV in presence of 0.6 Mol MgCl\(_2\). This corresponds to a ratio equal to 0.73. The potential of the Nafion membrane drops from 75 mV to 55 mV. This corresponds also to a ratio equal to 0.73. The fact that the two figures are the same shows that the selectivity of the FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) FS720 membrane is not affected by the divalent ions in the CREDSM. We recall that no variation of the open potential is measured for more than 8 hours in the CREDSM. It’s not the same thing when a direct ionic current flows through the membrane for 20 minutes as in the Faradaic cell. The membrane potential falls to 42 mV, which corresponds to a loss of selectivity of 16\(\%\). Same results are obtained with the FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) E-620 (K). In the CREDSM the membrane potential is equal to 43 mV in presence of divalent ions and to 58 mV in absence of divalent. This corresponds to a ratio 0.74, same figure than previously , suggesting that the permselectivity is not affected by the divalent ions in the CREDSM. In the Faradaic situation the membrane potential falls to 35 mV, which corresponds to a loss of selectivity of 17.8 \(\%\).

To conclude this section, the voltage drop in CREDSM is fully explained by the uphill effect model. However, in faradaic RED system, we observe additional contribution of voltage drop related to the selectivity loss in membrane.

Harvested Power Modeling

Another important point is to verify if the measured cell characteristics, including \(E_{m}\) and \(R_{cell}\), are sufficient to explain the recovered power losses. To check this, we will compare the results with a R-C model that we have validated in previous studies when the cell filling time is small compared to the period. Details can be find in the work of Brahmi et al.49 and in the method section. This modeling predicts that the power is given by:

The theoretical prediction is presented by solid lines in Figure 2c and d, it does not involve any fitting parameters. It is demonstrated that experimental power density performances are perfectly described by the classical modeling. For each brine solutions, we have used the measured resistance and capacitance values.

Based on the R-C model derived from the equivalent circuit, it is possible to describe the power density performance of CRED based on the electrochemical characteristics obtained, in the situation of both Nafion and FUMASEP\(^{TM}\) FS720.

Analysis of our results

Schematic illustration of the divalent impact mitigation mechanism of CRED system. The diagram summarizes the mechanisms that induce power loss in the presence of divalent ions. In the CREDSM context, only the uphill mechanism affects membrane potential. Electrode potential remains unaffected. This reduces the impact of divalents on the cell potential, which is the sum of the membrane potential and the electrode potential. Flow reversal prevents membrane poisoning. For a molar fraction of 0.6 of MgCl\(_{2}\), this results in a 34\(\%\) reduction in power. Under the same conditions and for a poorly selective Fumasep-type membrane, membrane poisoning and the cell potential, which is affected twice by the uphill phenomenon, lead to a 62\(\%\) power density reduction.

The reduction of the harvested power density due to divalent ions is being mitigated when a CRED cell is used. Divalent ions affect the properties of RED devices for two main reasons. The first is the uphill phenomenon, which modifies the membrane potential. This phenomenon is of course common to RED cells with capacitive electrodes and CRED cells. This phenomenon only applies to the membrane potential, not to the electrodes. The CREDSM cells consist only a single membrane and two electrodes. They can be placed in series by repeating this electrode-membrane-electrode unit. In this way, the basic capacitive cell potential is the membrane potential plus the electrode potential. As the latter is not affected by the presence of divalent ions, the potential of a series of single-membrane capacitive cells is less affected than that of a RED cell. The reduction in open-circuit potential is half that of a RED cell. The fact that the impact of divalents is limited in capacitive devices therefore stems primarily not from the capacitances themselves, but from the fact that it is possible to sum the electrode potentials by creating single-membrane cells. It should be remembered that, because of the overpotential on faradaic electrodes, it is not possible to use a single-membrane faradaic cell efficiently. Furthermore, putting faradaic cells in series would raise the problem of high electrode costs and the use of large quantities of toxic electrolytes.

Under these conditions it is possible to calculate the power loss in the presence of divalent ions in the CREDSM and compare it to the RED if there is no loss of membrane selectivity. It should be remembered that the loss of selectivity only occurs on membranes with low selectivity and during a direct ionic current. Assuming that the anionic membrane follows the same trends as the cationic membrane, the open-circuit voltage in a RED device of n membranes equals to \(n.E_{m}\). To simply the calculation, we take the case of a single membrane. The open circuit voltage in a RED device will drop from 107 mV to 86 mV for a salinity ratio of 100, from 77 mV to 54 mV for salinity ratios of 30 and from 50 mV to 23 mV for salinity ratios of 10 when the molar fraction of Na decreases to 0.4. In a CREDSM for salinity ratio Ra of 100, the open circuit voltage will drop from 178 mV to 155 mV for a salinity ratio of 100, from 132 mV to 105 mV for salinity ratios of 30, from 98 mV to 66 mV or salinity ratios of 10 when the molar fraction of Na decreases to 0.4. These figures lead to a decrease of power of 35.4 \(\%\) for a salinity ratio of 100, of 50.8 \(\%\) for a salinity ratio of 30, of 78.8 \(\%\) for salinity ratio of 10 when the molar fraction of Na decreases to 0.4 in a RED device. In comparison, the drop in power in a CREDSM is equal to 24.2 \(\%\) for a salinity ratio of 100, of 36.7 \(\%\) for a salinity ratio of 30, of 54.6 \(\%\) for salinity ratio of 10 when the molar fraction of Na decreases to 0.4. These figures are obtained with the measurement realized by Nafion HP membrane. The results are summarized in Table 5.

The second reason relates to membrane poisoning. Membrane poisoning is influenced by the chemical composition of the membranes. It is relatively rare in Nafion-type membranes but quite common in FUMASEP membranes. This is probably due to the very high surface charge of Nafion membranes, which enables them to avoid poisoning by divalent ions55. It leads to a reduction in membrane selectivity, a reduction in electrical potential membrane . The fact that the capacitive process is an alternative process prevents divalent ions from adsorbing permanently to the membrane, which is not the case with continuous processes. The improved properties of CREDSM compared with RED are once again an indirect effect of the alternating flow of the two solutions. It should be noted that this strategy could be applied to RED, as proposed by Vermaas. From a numerical point of view, assuming that the anionic membrane follows the same trends as the cationic membrane, the open circuit voltage in a RED device will drop from 68 mV to 42 mV for a salinity ratio of 30 when the molar fraction of Na decreases to 0.4 along with the selectivity decrease. In a CREDSM for salinity ratio of 30, the open circuit voltage will drop from 125 mV to 101 mV for salinity ratios of 30 when the molar fraction of Na decreases to 0.4. Under these conditions, the power generated by a RED device will fall by 34 \(\%\) and the power generated by a CREDSM device by 62 \(\%\).

The overall underlying mechanism is illustrated in Figure 6.

Life cycle analysis and Techno-economic analysis

Our study shows that capacitive cells can achieve significant power levels compared with the literature when real solutions are used. At this point, it becomes important to ask where blue energy technology stands from an economic and ecological point of view. The current literature can be confusing. Some articles mention the enormous power measured on a single nanotube and extrapolate the enormous power that can be recovered56, while others write that these techniques will never be marketable and is even not suited for the ecological transition57,58. We believe that the situation is halfway between these statements.

Let us first comment on the ecological footprint of the blue energy. A study of the life cycle analysis of our process is outside the scope of this article. However, before making an economic analysis of our process, we would like to remind a few points. Mueller et al.59 display in 2021 the the first comprehensive life cycle assessment (LCA) of reverse electrodialysis (RED). They conduct a LCA of 1MWh RED plant using natural waters or concentrated brines and compare the results to existing renewable energy technologies, including wind and solar photovoltaics. They studied 9 impact categories: acidification, ecotoxicity eutrophication, global warming, ozone depletion, photochemical oxidation, carcinogenics, non carcinogenics, and respiratory effects. In all the cases, the environmental impacts from RED are found to be comparable to, and sometimes lower than, established renewable energy technologies. The single drawback deals with eutrophication, ecotoxicity, and carcinogenic impacts which are slightly larger for RED than other technologies under the natural water scenario and not the brine one. Processes associated with membrane manufacture are primary contributors to these impact categories. We anticipate that these impacts may be thus decreased by using biosourced membranes such as cellulose membranes in the natural water situation. The authors conclude by saying that RED performs as well as or better than other renewable energy technologies in terms of ecological impact. The footprint is not analyzed in this article, but it is comparable to or better than that of photovoltaic plants. Indeed, despite a power density 30-50 times lower than that of photovoltaic energy, it is possible to produce the same power as a photovoltaic plant on smaller surfaces, because RED cells can be stacked on top of each other. Taking into account a thickness of 0.4 mm for two membranes and two liquid compartments (i.e. for the cell repeat pattern) and a density power of 1 W m\(^{-2}\), it is possible to estimate the power of a 1 m \(\times \) 1 m\(^{2}\) cell at 5 kW. The basic RED modules will therefore take up 20 times less space than the basic photovoltaic modules, whose density power is estimated at 100 W m\(^{-2}\). Discharges of saltwater solutions are not analyzed in this article, and at this stage there are no studies to show how the fragile ecosystem that makes up an estuary can be affected by withdrawals and discharges of saltwater mixtures. Without getting too far ahead of ourselves in this not-so-simple debate, it is nevertheless important to note that osmotic energy devices mix seawater and river water. It may therefore be possible for the estuary, which does the same, to discharge this water at a point where the salinity is close to that of the mixture. Finally, this impact is less significant when the brine systems studied are industrial brines. In this case, the problem of discharge is already part of the process. All these points are very positive and lead us to ask why RED technology is failing to emerge. One crucial point is the cost. High-performance membranes are expensive membranes. It is important to analyze this point in greater detail and to compare our work with existing results. To do this, we will draw on a techno-economic analyses carried out on RED systems27,60,61.

Post estimated the cost of a RED device in 2010 for a system producing 200 kW. The calculation includes the costs of construction and membrane (200 000 € ), filtration (320 000 € ), liquid pumping and maintenance (370 000 € ). The fluids pass through the system only once, at a speed 1 \( cm.s^{-1}\) comparable to our experiments. The calculation takes into account a membrane price of 2 euros per m\(^{2}\) and a power of 2 W per m\(^{2}\). Membrane lifetime is 7 years, with production running 8000 hours a year. 9\(\%\) of the construction and functioning cost are considered to be the exploitation cost over 7 years. Taking inflation into account, this corresponds to a current cost of 1 232 027 euros . This results in a production cost equal to 0.111 € per kWh, i.e. 111 euros per MWh. This figure is in line with current electricity production costs (solar energy 40 € per MWh, wind off shore 120 € per MWh62). In this calculation, the price of the membrane is certainly underestimated while the production power is overestimated. More realistically, on the basis of our experimental results, we can envisage several different cases and display two other scenarios in the table. We have measured a power of 3.2 W m\(^{-2}\) for a ratio of 300 between a high salinity solution and a fresh water solution in presence of magnesium and calcium. This case mimics that of a plant built between the Great Salt Lake and using water from the lake plus treated wastewater or a plant located in the Ettore e Infersa saltworks in Marsala (Trapani, Italy). The Italian site supplies fresh water from a well on the coast) and almost saturated brine26,27,54. These cases are very interesting because all these brines do not require filtration. Algae and microorganisms do not grow in such high salinities and the desalination effluents, treated water effluents or water from a shoreline well are rather clean54. We propose an analysis based upon a power density of 3.2 W m\(^{-2}\) (equal to our previous measurement) and two cost of membranes.The cost of membrane is difficult to estimate. Post’s calculation takes into account a membrane price of 2 euros per m\(^{2}\) . It’s important to note that no membrane currently achieves this cost price. It ’s also important to note that the price we pay for a lab scale membrane differs from the commercial price in case of industrialization of the RED process. Because we are interested in real-world greenhouse applications, we will use the commercial price in our cost analysis. Taking into account a lab-scale to commercial cost ratio of Fujifilm membrane equal to 2.8 (based on the lab-scale to commercial cost ratio of the Neosepta membranes), Ahdab et al.63 propose to use a cost equal to 58 € per m\(^{2}\) for a Fujifilm membrane. We assume the commercial cost will be same for FUMASEP®FS720 membrane. Note that the lab scale price for a FUMASEP®E-620 (K) membranes is 57 € per m\(^{2}\)64. We therefore propose a scenario A based on a construction cost of 60 € per m\(^{2}\) for the membranes in the cell. This cost takes into account the cost of the membrane and the carbon felt.

In another realistic techno-economic analysis, Giacalone et al.27 consider that the price of highly selected membrane is 15 € per m\(^2\). This price is in line with the recent development of sulfonated poly-ether-ether-ketone, sPEEK membrane. Owing to the low cost of raw material (61.5 € /kg for PEEK polymer), Zhu65 and Yuan66 estimate the cost of sPEEK membrane to be as low as 12€ per m\(^{2}\), which is at least 20 or 30 times lower than that of commercially available Nafion membranes. We will thus propose a B Scenario based over a cost of 15 €per m\(^{2}\)for the membrane and the carbon felt. The results are summarized in Table 6.

The viscous loss is estimated at 0.2 W per m\(^{2}\) of membranes. We have previously measured similar viscous losses in our devices (0.1 W m\(^{-2}\)). We thus take into account the same cost of viscous loss and filtration when required. To this figure we need to add the power required to reverse the flows. To estimate the cost of valves additionally used in the capacitive system, we estimate the cost at around 35\(\%\) of the cost related to piping, fittings and pumps.

This analysis shows that the very salty solutions is economically viable and comparable to other renewable energies 111 € per MWh, if we consider a membrane plus felt price of 15 € per m\(^{2}\). It remains however high, 399 € per MWh, in the situation where the price of the membrane plus felt equals 60 € per m\(^{2}\). Note that the obtained values are better than the one predicted following the results of Tedesco54 and the analysis of Giacalone27 because the power density is higher (3.2 W m\(^{-2}\)), we have considered no filtration and the plant is different as it encompasses 100 000 m\(^2\) of membranes. The main contribution of our work is the fact that we are able to limit the role of the divalent ions. Considering the Dead sea water scenario (a plant built between the Dead sea and a desalination plant27) and following the same analysis, the cost will be reaching 200 € per MWh. This was the scenario 2 of our study. Lastly, considering sea water mixed with river water, the harvested power remains slightly higher than 1 W per m\(^{2}\) and leads to a cost of 400 € per MWh which is too high even in the situation of sPEEK membranes. It will correspond to a cost of 1276 € per MWh for a membrane cost of 60 € per m\(^{2}\).

Conclusion

In this work, we evaluate the electrochemical characteristics and energy performance of CRED system under the impact of divalent ions. Different from RED systems where significant power density drop is reported, CRED system present limited power density drop . It is demonstrated in different mixing ratios and even real-world solutions that CRED systems are efficient in mitigating the impact of divalent ions. We reveal the underlying mechanism of the minor power density loss of CRED system related to divalent ions. The model-experiment comparison suggests the fact that the open-circuit voltage drop in CRED system can be thoroughly explained by the uphill effect and by the variation of the membrane potential due to thermodynamic considerations (activity of the divalent ions, factor 2 on the Nernst equation). The membrane poisoning issues extensively reported in RED systems, which have a huge impact on membrane selectivity and cell resistance, are not in presence in CRED system. While membrane poisoning occurs within less than in a hour in RED systems, CRED system mitigates the membrane poisoning issues simply by the intrinsic water chamber reversal process in its working regime. This enables a stable power density output over 500 cycles (8 hours), as demonstrated in our research results. Comparing with the expensive and complex design of monovalent selective membranes, the water chamber switch process is cost effective and easy to implement in RED systems. It is surely an efficient method to be generalized in faradaic RED systems.

In addition, as demonstrated in the experimental results, divalent ions have significant impact on membrane related potentials but limited impact on capacitive electrode related potentials. In the scale up process of RED systems, only cationic and anionic membranes are stacked to increase the overall cell voltage. As the majority of the cell voltage contribution is related to the membrane stack, the overall voltage is severely influenced by the divalent ion mixing. However for the scale up of CRED system, the repeating unit comprises a selective membrane and a pair of capacitive electrodes. The electrode related voltage contribution is comparable to that of membrane stack. This indicates a limited open-circuit voltage drop in CRED stacks compared with RED systems.

From an economical point of view, we come to the same conclusion as Giacalone et al.27. We demonstrate the potential for brine and freshwater RED plants to become financially sustainable when using highly concentrated brine from a natural lake or sea and treated freshwater. The novelty of our work lies in having obtained these results from experiments where divalent ions are present and not from simulation. We recall that the presence of divalent ions is a key question in the conclusion of Giacalone et al. and that of Tedesco et al.26. We have also shown that the process is not cost-effective for freshwater and river estuaries. However, costs using sPEEK membranes are 4 times higher than the cost of renewable energy sources. The difference is substantial enough to hinder the direct application of the results, yet minor enough to encourage continued investigation into the process.

Methods

Capacitive cell: description

The experiments are performed in a capacitive cell. A configuration akin to that detailed in the prior study by Brahmi et al.49 is employed here (Figure 7a). The cell exhibits symmetrical geometry, featuring an ion-exchange membrane (Nafion\(^{TM}\)117, Chemours) sandwiched between two water compartments containing varying salt concentrations. The membrane, with a dry thickness of 183 \(\mu \)m, ensures an average conductivity exceeding 0.1 S.cm\(^{-1}\) and a total acid capacity ranging between 0.95 and 1.01 meq.g\(^{-1}\). The effective surface area of the ion-exchange membrane used in our experimentation measures 5.5 cm\(^2\) unless precised. Carbon felt capacitive porous electrodes (Kynol Activated Carbon Felt) are separately positioned within gaskets on either side of the membrane. The graphite current collectors are situated at a distance of 1.4 mm from the membrane and are directly linked to the carbon felt capacitive porous electrodes. The entire assembly is securely sealed by stainless steel endplates and held together using eight bolts torqued to 2 N.m. Note that after the cell has been clamped, there is no space between the electrodes and the capacitive tissue. Saline solutions flow into the pores of the capacitive tissue. Two ports facilitate water inlet and outlet, driven by a peristaltic pump (Longer Multichannel Peristaltic pump) operating at a consistent flow rate of 10 mL.min\(^{-1}\).

Schematic illustration of the capacitive cell. (a) The capacitive system assembly illustration. (b) The working principle of the CRED system. The periodic water solution reversal is necessary to ensure the continuous electricity production. The eventual electrical signal delivered by the CRED system will be periodic and alternating.

While concentrated solution and diluted solution are injected continuously into the capacitive system, a cationic flow is generated from the concentrated part towards the diluted part under the osmotic effect. The cation exchange membrane blocks the anions and water molecules from free passing. In order to generated electricity, it is necessary to convert this cationic flux into a flux of electrons. In a capacitive system, ions are adsorbed onto the capacitive electrode, inducing the movement of electrons in the outer circuit. Due to charge accumulation inside the capacitive electrodes, the system reaches eventually a saturation regime where the fully charged capacitor blocks the creation of cationic flux (Figure 7b). To deblock the saturated regime of capacitive charging, an automated 4-port valve switches water compartments at fixed intervals of \(T_s\). By doing the solution reversal in the chamber, one can reverse the direction of both ionic and electronic flux, thus discharging the accumulated charges in capacitive electrodes and restart the charging process in a reversed direction. This repeated transition within a fixed period \(T_s\) unblocks the saturation state, enabling the cell to deliver periodic alternating current. A detailed model can be found in the work of Wu et al.50.

Preparation and composition of the salted solutions

NaCl, MgCl\(_2\), CaCl\(_2\) and KCl were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. In this study, we prepared solution mixtures of different concentrations. The compositions of these solutions are described in Tables 7 and 8.

Measurement of the open circuit voltage

To evaluate the inherent potential of the circuit, we initially link the two cell electrodes. One compartment is filled with a high salt concentration while the other contains a low salt concentration. We then wait for equilibrium to be established.

Modeling the temporal progression of the potential necessitates understanding the behavior of both the electrodes and the membrane. Across the entirety of the circuit, there is no voltage drop. This can be expressed as follows:

Here, \(E_m(t)\) represents the voltage drop across the membrane, \(E_{elec-c}(t)\) signifies the voltage drop across the capacitive layer, I denotes the current intensity, and \(R_{cell}\) is the ohmic resistance of the cell, which encompasses the resistance of the solvent, carbon felt, and current collector.

Changes in the concentrations of ions over time cause the temporal evolution of \(E_{elec-c}(t)\) and \(E_m(t)\). These variations stem from cell filling and the creation of a diffuse ion layer near the electrodes when altering the salt concentration.

At \(t=0\), the system is in a stable state with \(I(0)=0\) and \(q(0)=q_0=C(E_m(\infty )+E_{elec-c}(\infty )\). For t less than 0, the sum of membrane and capacitive layer potentials is given by \(E_m(\infty )+E_{elec-c}(\infty )\); at \(t=0\), the flow in both compartments reverses and the signs of membrane and capacitive layer potentials change. Upon reaching steady state after reversal, membrane and capacitive layer potentials are determined by \(-E_m(\infty )-E_{elec-c}(\infty )\).

The solution to Equation 10 is straightforward. We arrive at:

\(q_0 = C(E_m(\infty )+E_{elec-c}(\infty ))\).

This leads to \(RI(\infty )=E_{OCV-c}=-2(E_m(\infty )+E_{elec-c}(\infty ))\). To conclude, as noted in the main text, the open-circuit measurement for a capacitive cell corresponds to twice the steady-state membrane potential and capacitive layer values.

Experimentally, to measure OCV, we continuously feed the compartments with solutions of different salinities for 300 s, then reverse the flows for 300 s. This process is repeated 5 times. We record the evolution of the open-circuit voltage signal. The cell delivers no electrical current, and only ionic flows are responsible for the measured signal. The signal stabilizes in less than 100 seconds after the flow reversals. The signal is averaged over the 50 seconds preceding the change in concentration. OCV is measured by taking the quater of the difference in signals when saltier water flows into the right-hand compartment and when saltier water flows into the left-hand compartment. The absolute values of the two measurements may differ slightly (by plus or minus 5\(\%\)) if the two electrodes are not the same. In this situation, we measure the electrode potential plus the electrode membrane. It should be noted that these values are flow-dependent, due to the non-perfect selectivity of membranes.

Measurement of the membrane potential voltage

To gain insight into the individual impact of the membrane and the electrodes on the potential, we conducted separate measurements of the open-circuit potential of the membrane, denoted as \(E_{m}\). These measurements were performed while subjecting the membrane to salt gradients, utilizing custom-made Faradaic Ag/AgCl electrodes. The experimental procedure is the same for Faradaic and capacitive electrodes. In an open circuit, Faradaic electrodes are not subject to polarization phenomena (no current-induced polarization, no resistive or capacitive effects of Debye layers67,68,69, as no current flows through them.

For a Faradaic cell, the OCV voltage corresponds to the sum of the membrane voltage and the Faradaic electrode voltage.

Thus in order to obtain the membrane voltage \(E_m\), it is necessary to measure the Faradaic electrode related voltage \(E_{elec-f}\). In our experiment, we immersed the two home-made Ag/AgCl electrodes into concentrated solution and diluted solution in two beakers separately. The solutions used in experiments follows the same experimental conditions as mentioned above for \(E_{OCV-c}\) and \(E_{OCV-f}\) measurements (solutions of different saliniy ratios with different divalent molar mixing fractions). The whole circuit is closed by the use of a home-made salt bridge (KCl saturated). Then the electrode potential difference \(E_{elec-f}\) is measured by using a potentiostat.

The capacitive cell assembly is described above and we measure the open-circuit voltage \(E_{OCV-c}\) for solutions of different salinity ratio with different mixing molar fraction. As explained above, the OCV voltage of a capacitive cell corresponds to twice the sum of the membrane voltage and capacitive electrode voltage.

Following the above two equations (Equation 14 and Equation 15), we can easily calculate the membrane voltage \(E_m\) and capacitive electrode voltage \(E_{elec-c}\).

Measurements of the impedance of the cell

Each compartment of the cell is supplied with a different saline solution under a constant flow rate. The circuit is open, and we wait for steady-state. We then apply 10 mV oscillatory perturbations over the open-circuit voltage. We use a logarithmically spaced frequency range from 200 kHz to 10 mHz for a fixed salinity ratio of 30 g L\(^{-1}\) vs. 1 g L\(^{-1}\) situation with different divalent ion mixing fraction. A Nyquist plot can be plotted corresponding all to a sweep over a frequency range from 200 kHz to 10 mHz. Note that the exact value of the impedance depends on the tightening. Here, we used the impedance data measured at 10 mHz to characterize the cell inner resistance and capacitance. Variations of 0.5 (\(\Omega \) cm\(^{2}\)) in real part are measured on consecutive experiments despite the care taken to make the clamping procedure repeatable.

Measurement and modeling of the harvested power

The system under consideration embodies a capacitive configuration. To restore current, a cyclic process reminiscent of cap mixing procedures is employed, where distinct brine flows with varying concentrations are directed into the two compartments. The experimental apparatus incorporates a rotary valve that permits the passage of highly concentrated saltwater into the first compartment for a duration of \(T_s\), succeeded by the circulation of fresh water for an equivalent \(T_s\) duration. This procedure is reversed in the second compartment. Here, \(T_s\) represents the half period of the salt gradient. The direction of the current shifts with each cycle, which is a distinctive trait of capacitive currents. The use of capacitive electrodes prompts a reevaluation of the methodology employed for measuring the recovered power. The mean gross power density \(P_{gross}\) (that is, power density without compensating for pumping losses) is assessed by averaging the signal recorded across the resistance over a time interval of \(2T_s\). The parameter A denotes the area of the membrane. The expression is as follows:

It’s noteworthy that these measurements constitute direct assessments that mirror real-world scenarios. These experiments are conducted across various salinity gradients, oscillation periods, and flow rates.

In a previous work49, we developed a theoretical model that can account for the measured power and that describes the experimental values well when the cell filling time is small compared to the period. Details about the modeling can be find in the work of Brahmi et al.49. We recall here only the main point of the theoretical approach. According to an analysis of the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, a R-C model is proposed as a simplified fitting model for the cell-booster system49. The system inner resistance \(R_{cell}\) and capacitance C can be quantitatively characterized by Potentiostatic electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (PEIS) measurement using a potentiostat. \(E_{mem}(t)\) is the potential drop over the membrane, \(E_{elec}(t)\) the electrical potential due to the salt adsorption on the electrodes, \(R_{cell}(t)\) the resistance of the cell (including the ohmic and non ohmic resistance of the solvent, the membrane, the carbon felt and the current collector). The temporal variation of \(R_{cell}(t)\), \(C_{cell}(t)\) \(E_{mem}(t)\) and \(E_{elec}(t)\) are due to the temporal variation of the ion concentration profile including osmotic potential, diffuse layer establishment, cell filling process after water compartment switching and etc. In the following we will assume that these characteristic times and the filling time of the cell are negligible compared with the switch half period \(T_s\). Thus, these functions will be modeled simply by window functions:for \(0<t<T_s\), \(E_{mem}(t)+E_{elec}(t)=E_{OCV}\) and for \(T_s<t<2T_s\), \(E_{mem}(t)+E_{elec}(t)=-E_{OCV}\). In this framework, \(R_{cell}(t)\) and C do not depend upon t.We recall that \(T_s\) is the switch half period.

Following these conditions, we establish the theoretical model for a pure cell-resistor circuit in absence of boosting by the equations below:For \(0<t<T_s\):

For \(T_s<t<2T_s\):

We solve analytically these equations and calculate the electrical power recovered by the load resistor.We find:

Conductivity measurement of effluents

To verify the extent of salt mixing inside the CREDSM system, we conducted conductivity measurements during the experiment. Solutions samples are taken in 3 different scenarios to conduct further tests of conductivity. We take solution samples of concentrated part and diluted part before their injection into the CREDSM system. These results are considered as a comparison baselines. Then solution samples of concentrated part and diluted part are taken after their mixing inside the CREDSM system under Open-circuit mode and closed-circuit mode, respectively. The conductivity measurements are realized by a conductivity meter (SevenDirect SD30, Mettler Toledo). On our device CREDSM, the variation of the conductivity depends upon the nature of the membrane.

In the Nafion HP situation, for feed solutions composed of 80\(\%\)NaCl - 20\(\%\) CaCl\(_2\) of 30g/L and 1g/L, we observe a major conductivity increase of 0.54\(\%\) in diluted solution and no significant conductivity variation in concentrated solution in Open circuit mode. While the CREDSM is connected to a load resistor to form a closed electrical circuit, a larger conductivity increase of 5.14\(\%\) is observed in diluted solution. Still we do not observe any conductivity variation in the concentrated solution.

In the Fumasep FS720 situation, for feed solutions composed of 80\(\%\) NaCl - 20\(\%\) CaCl\(_2\) of 30g/L and 1g/L, we observe a larger conductivity increase of 4.86\(\%\) in diluted solution and no significant conductivity variation in concentrated solution in Open circuit mode. While the CREDSM is connected to a load resistor to form a closed electrical circuit, a larger conductivity increase of 11.66\(\%\) is observed in diluted solution. Still we do not observe any conductivity variation in the concentrated solution.

In OCV mode, the conductivity variation is purely due to the imperfection of the membrane selectivity. The mixing observed is thus uncontrolled loss. However, in closed circuit mode, the mixing originates both from the uncontrolled loss and the useful mixing which results in the electricity production. From the above results, it can be deduced that Nafion HP membrane presents higher selectivity than Fumasep FS720. The extent of mixing in the CREDSM system is rather small, with a conductivity variation of 5\(\%\) for Nafion HP and 10\(\%\) for Fumasep FS720.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Vermaas, D. A., Veerman, J., Saakes, M. & Nijmeijer, K. Influence of multivalent ions on renewable energy generation in reverse electrodialysis. Energy & Environmental Science 7, 1434–1445. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3EE43501F (2014).

Veerman, J., Gómez-Coma, L., Ortiz, A. & Ortiz, I. Resistance of ion exchange membranes in aqueous mixtures of monovalent and divalent ions and the effect on reverse electrodialysis. Membranes 13, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes13030322 (2023).

Chu, S. & Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 488, 294–303. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11475 (2012).

Hoffert, M. I. et al. Advanced technology paths to global climate stability: Energy for a greenhouse planet. Science 298, 981–987. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1072357 (2002).

Norman, R. S. Water Salination: A Source of Energy. Science 186, 350–352. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.186.4161.350 (1974).

Yip, N. Y., Brogioli, D., Hamelers, H. V. M. & Nijmeijer, K. Salinity gradients for sustainable energy: Primer, progress, and prospects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 12072–12094. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b03448 (2016).

Logan, B. E. & Elimelech, M. Membrane-based processes for sustainable power generation using water. Nature 488, 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11477 (2012).

Wu, N., Brahmi, Y. & Colin, A. Fluidics for energy harvesting: From nano to milli scales. Lab Chip 23, 1034–1065. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2LC00946C (2023).

Alvarez-Silva, O. A., Osorio, A. F. & Winter, C. Practical global salinity gradient energy potential. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 60, 1387–1395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.03.021 (2016).

https://redstack.nl; https://www.sweetch.energy. REDSTACK (2024).

Pattle, R. E. Production of electric power by mixing fresh and salt water in the hydroelectric pile. Nature 174, 660–660. https://doi.org/10.1038/174660a0 (1954).

Loeb, S. Method and apparatus for generating power utilizing reverse electrodialysis (1979).

Yip, N. Y., Vermaas, D. A., Nijmeijer, K. & Elimelech, M. Thermodynamic, energy efficiency, and power density analysis of reverse electrodialysis power generation with natural salinity gradients. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 4925–4936. https://doi.org/10.1021/es5005413 (2014).

Mei, Y. & Tang, C. Y. Recent developments and future perspectives of reverse electrodialysis technology: A review. Desalination 425, 156–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2017.10.021 (2018).

Donnan, F. G. & Harris, A. B. CLXXVII.–The osmotic pressure and conductivity of aqueous solutions of congo-red, and reversible membrane equilibria. J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 99, 1554–1577. https://doi.org/10.1039/CT9119901554 (1911).