Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a severe clinical respiratory condition characterized by high rates of mortality and morbidity, for which effective treatments are currently lacking. In this study, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was used to induce ALI mice, demonstrating the efficacy of tetramethylpyrazine (TMP) in ameliorating ALI. Subsequent we perfored high-throughput sequencing analysis and used Targetscan 8.0 and miRWalk 3.0 databases to predict the interaction between microRNAs and destrin (DSTN), ultimately identifying miR-369-3p as the focus of the investigation. The adenovirus carrying miR-369-3p was administered one week prior to LPS-induced in order to assess its potential efficacy in ameliorating ALI in mice. The findings indicated that the overexpression of miR-369-3p resulted in enhanced lung function, reduced pulmonary edema, inflammation, and permeability in LPS-induced ALI mice, while the suppression of miR-369-3p exacerbated the damage in these mice. Furthermore, the beneficial effects of TMP on LPS-induced ALI were negated by the downregulation of miR-369-3p. The results of our study demonstrate that TMP mitigates LPS-induced ALI through upregulation of miR-369-3p. Consequently, the findings of this study advocate for the clinical utilization of TMP in ALI treatment, with miR-369-3p emerging as a promising target for future ALI interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a significant clinical respiratory disorder characterized by damage to the alveolar epithelium and endothelium, increased permeability, extensive fluid leakage, release of inflammatory mediators, hypoxemia, and ultimately respiratory failure, with the potential for progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in cases that are severe1,2. It is distinguished by pulmonary damage and compromised microvascular permeability, resulting in a robust inflammatory reaction that can ultimately culminate in fatality3,4. While progress has been made in elucidating the pathophysiology of ALI, current therapeutic interventions primarily rely on protective mechanical ventilation strategies to enhance survival rates5. To optimize treatment outcomes, additional investigations and the exploration of novel pharmacological agents and therapeutic modalities are imperative.

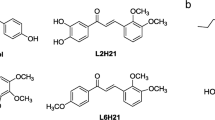

The pulmonary microvascular endothelium serves as a metabolically active organ, and its impairment can result in pulmonary parenchymal inflammation and non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Consequently, the pulmonary endothelium is essential for the maintenance of lung and systemic cardiovascular homeostasis, and is integral to the pathogenesis of ALI/ARDS6. Tetramethylpyrazine (TMP), a prominent constituent derived from ligusticum chuanxiong, has been employed in the treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular ailments over an extended period7. There is evidence to suggest that TMP may decrease the lung dry–wet ratio, inflammation, and the expression of TLR4 following LPS-induced lung injury in mice8. A prior investigation demonstrated that TMP suppressed endothelial cytoskeletal reorganization via the Rac1/LIMK pathway in LPS-induced ALI9. Current research indicates a growing body of evidence implicating actin cytoskeleton remodeling in endothelial cell functionality. Destrin (DSTN), a member of the actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF)/cofilin family, consists of DSTN, cofilin-1, and cofilin-210. DSTN is a crucial actin-binding protein that plays a fundamental role in the dynamic regulation of intracellular actin filaments, thereby maintaining cell morphology, polarity, and migration11. Actin dynamics are controlled by DSTN, which promotes monomerization of F-actin and filament severing, thereby directly contributing to cytoskeletal remodeling12. As a member of the ADF/cofilin protein family, DSTN's association with cancer has been extensively studied13,14, and several studies have indicated that increased expression of DSTN can result in dysfunction of the cerebral vascular endothelial cell barrier in mice15,16. Given the resemblance between the cerebral vascular endothelial barrier and the pulmonary vascular endothelial barrier, there is a scarcity of research on the impact of DSTN in pulmonary endothelial barrier dysfunction. Consequently, it is postulated that DSTN may have a noteworthy role in ameliorating ALI through TMP. To substantiate this hypothesis, it was observed that TMP enhances ALI by increasing the expression of DSTN.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short, single-stranded RNA molecules that do not code for proteins and typically consist of 17 to 25 nucleotides17. They are highly conserved across various organisms and primarily regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. It primarily destabilizes or inhibits translation18 by targeting the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of mRNA transcripts in the cytoplasm19,20. A number of recent studies indicate that miRNAs have also been implicated to positively-regulate gene transcription by targeting promoter elements21,22, a phenomenon known as RNA activation (RNAa)23,24,25,26. Therefore, microRNAs can both positively and negatively regulate the expression of target proteins27. The involvement of miRNAs in ARDS has garnered increasing interest in recent years28. Research has demonstrated that miR-27a mitigates apoptosis and inflammation in mice with LPS-induced ALI29, while the downregulation of miR-34b-5p in ALI mice reduces inflammation and apoptosis by targeting pregranuloprotein30. Consequently, high-throughput sequencing was employed to analyze the lung tissues of mice treated with ALI and TMP, resulting in the identification of 59 differentially expressed microRNAs. Among these, 29 microRNAs exhibited reduced expression following LPS induction but increased expression following TMP protection. Subsequently, Targetscan 8.0 and miRWalk 3.0 were utilized to predict the interaction between microRNA and DSTN, and the miR-369-3p was finally discovered as a potential target. Numerous studies have highlighted the significant role of miR-369-3p in inflammation31,32, and inflammatory response plays an important role in the pathogenesis of ALI. The specific function of miR-369-3p in ALI remains ambiguous. However, this study reveals that the administration of TMP effectively ameliorates ALI by upregulating miR-369-3p, thereby decreasing pulmonary vascular permeability and safeguarding against LPS-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction. Consequently, the primary objective of this research is to propose novel therapeutic strategies and theoretical insights for the management of ALI/ ARDS.

Results

TMP ameliorates LPS-induced ALI through the DSTN/ZO-1/occludin pathway

The ALI mice model was established as previously described. The SpO2 was measured 24 h later, and lung function was assessed. The SpO2 of mice in the LPS group exhibited a significant decrease, while the SpO2 of ALI mice recovered following TMP intervention (Fig. 1a). Histological examination using HE staining revealed alveolar collapse, inflammatory cell infiltration, and hyperemia in lung tissue sections. Notably, TMP treatment significantly ameliorated pulmonary disease and reduced lung injury scores (Fig. 1b,c). In Fig. 1d–h, comparing to the control group, it was observed that BALF protein levels, white blood cell counts, and pro-inflammatory factor expression levels were significantly increased in the lungs of mice in the LPS group. However, following TMP intervention, these parameters showed a notable decrease. Western blot analysis revealed changes in DSTN, ZO-1, and occludin levels (Fig. 1i), with reduced histone expression in response to LPS stimulation but elevated histone levels after TMP treatment compared to the control group. Collectively, these findings suggest that TMP exerts potential therapeutic effects on ALI through modulation of the DSTN/ZO-1/occludin pathway.

TMP ameliorates LPS-induced ALI through the DSTN/ZO-1/occludin pathway. The “two-hits” method builds the ALI model. (a) The mice SpO2 was measured using the PhysioSuite™ Small Animal Respiratory Detection System. (b,c) HE staining of mouse lung tissues was taken to observe the pathological changes of the lungs and to score the damage. (d) Mouse lung tissues were weighed and dried to calculate the wet-to-dry ratio to assess lung edema. (e) BALF was taken to detect the total leukocyte count. Total RNA was extracted from lung tissues, and the expression levels of inflammatory factors IL-1β (f), IL-6 (g), and TNF-α (h) were detected. (i) The expression levels of the proteins DSTN, ZO-1, and occludin were detected in lung tissues using Western blotting. Data are presented as means ± SD (n ≥ 3). One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey's test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

High-throughput analysis

The lung tissues of mice exposed to LPS or TMP were subjected to high-throughput sequencing technologies (Fig. 2a), revealing significant variations in the expression levels of 59 miRNAs. Specifically, the expression of 29 miRNAs decreased following LPS exposure but increased after TMP treatment. Subsequently, Targetscan 8.0 and miRWalk 3.0 were utilized to predict the binding interactions between microRNAs identified through high-throughput sequencing and DSTN. Notably, miR-369-3p was identified as capable of binding to DSTN, as depicted in Fig. 2b, illustrating the specific binding site on DSTN. These results suggest that miR-369-3p regulates the DSTN to contribute to the protective effect of TMP on ALI.

High-throughput analysis. (a) miRNA high-throughput sequencing cluster heat map. Red represents up-regulated expression and green represents down-regulated expression, P < 0.05. (b) miR-369-3p binding site to DSTN. (d) Effectiveness of adenovirus interventions. (c) The changes of target protein after up-regulation or down-regulation of miR-369-3p. Data are presented as means ± SD (n ≥ 3). One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey's test: *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001.

Consequently, in vivo intervention was conducted through tracheal infusion of HBAD-EGFP control, HBAD-Adeasy-has-miR-369-3p-Null-EGFP, and HBAD-Adeasy-has-miR-369-3p-sponge-EGFP. We assessed miR-369-3p expression levels in lung tissue to determine whether the intervention had any effect (Fig. 2c). The findings indicated no notable distinction between the HBAD-EGFP control group and the control group. The expression of miR-369-3p exhibited a significant increase of 6–7 times in the hbad-adease-has-miR-369-3p-null-egfp group. Following intervention with HBAD-Adeasy-has-mir-369-3P-sponge-EGFP, there was a notable reduction in miR-369-3p expression in mice. Western blot analysis was conducted to assess the expression of the targeted protein DSTN (Fig. 2d). Overexpression of miR-369-3p resulted in an enhancement of DSTN expression compared to the control group, while down-regulation of miR-369-3p reduced expression of DSTN.

Effects of modulating miR-369-3p on LPS-induced lung function in mice

The ALI model was established in mice after a week of adenovirus intervention. Lung tissue samples were subjected to HE staining (Fig. 3a,b), revealing alveolar collapse, congestion, thickening of alveolar septum, and inflammatory cell infiltration in the model group. Overexpression of miR-369-3p was found to mitigate lung injury and reduce lung injury score, whereas downregulation of miR-369-3p exacerbated lung injury and increased lung injury score. Lung function was evaluated through measurement of SpO2 and lung index (Fig. 3c,d), with no changes observed in the GFP group. It is worth noting that miR-369-3p overexpression increased SpO2 and decreased lung index, while downregulation of miR-369-3p further reduced SpO2 and increased lung index.

Effect of modulating miR-369-3p on pulmonary vascular permeability in ALI mice

Pulmonary endothelial barrier dysfunction is a hallmark of clinical pulmonary edema and contributes to the development of ALI. To assess pulmonary endothelial barrier dysfunction. We examined the lung tissue wet-to-dry ratio and leukocyte total count, protein concentration, and expression levels of pro-inflammatory factors in BALF (Fig. 4a-e). The results showed that, compared with ALI mice, overexpression of miR-369-3p resulted in significantly lower wet-to-dry ratio of lung tissue, total protein level, leukocyte count and expression of inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-1β. down-regulated miR-369-3p expression levels were significantly increased. As shown in Fig. 4f,g, after Evans Blue (EB)was injected into the tail vein, the pulmonary vascular permeability was evaluated by measuring dye extravasation, and the results showed that EB albumin leakage in the lung tissue of ALI group mice increased significantly. However, overexpression of miR-369-3p mitigated the increase in EB leakage. We also detect the expression of miR-369-3p's target protein (Fig. 4h), and the results showed that miR-369-3p up-regulation promoted DSTN expression compared with LPS group, while miR-369-3p down-regulation inhibited DSTN expression.

Effect of modulating miR-369-3p on pulmonary vascular permeability in ALI mice. (a) Ratio of lung wet weight to lung dry weight. The expression of total leukocyte counts (b), protein concentration (c) and inflammatory factors IL-1β (d), TNF-α (e), in BALF. (f,g) EB was injected into the tail vein, and the lungs were removed by cardiopulmonary lavage two hours later. (h) western bolt detects the expression of DSTN. Data are presented as means ± SD (n ≥ 3). One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

The effect of regulating miR-369-3p on tight connections in ALI mice

The interactions among endothelial cells are significant in modulating endothelial barrier permeability, with ZO-1 and occludin serving as key tight junction proteins. Western blot analysis revealed differential expression levels (Fig. 5a), indicating that miR-369-3p overexpression enhances tight junction protein expression, while its downregulation suppresses it. Immunofluorescence results (Fig. 5b) corroborated the Western blot findings. Collectively, these findings suggest that overexpression of miR-369-3p impedes the activation of the LPS-induced DSTN/ZO-1/occludin pathway.

The effect of regulating miR-369-3p on tight connections in ALI mice. (a,b) Western bolt and immunofluorescence detects the expression of tight junction protein ZO-1, and occludin protein in lung tissue. Data are presented as means ± SD (n ≥ 3). One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Knockdown of miR-369-3p partially counteracts the protection of TMP in LPS-induced ALI mice

HE staining (Fig. 6a,b) results demonstrated that both the LPS + TMP group and LPS + Dex group exhibited improvements compared to the LPS group, showing a reduction in irregular alveolar collapse, alveolar wall thickening, and inflammatory cell infiltration. However, it was found that the beneficial effects of TMP on LPS-induced ALI mice pathological lung injury were reversed in LPS + TMP + miR-369-3p-sponge group. As presenter in Fig. 6c,d, EB findings demonstrated a significant improvement in EB leakage in the lungs of ALI mice following treatment with TMP and Dex compared to the LPS group. Conversely, downregulation of miR-369-3p reversed TMP's beneficial effects on lung leakage. Wet/dry ratio analysis (Fig. 6e) further revealed that both TMP and Dex effectively mitigated lung edema compared to the LPS group. Nevertheless, when miR-369-3p was knocked down, lung wet/dry ratios increased, indicating increased edema compared to the TMP group. As shown in Fig. 6f,g, comparing to the LPS group, protein concentration and leukocyte total counts in BALF were reduced in the TMP and Dex-treated groups. In contrast, down-regulation of miR-369-3p increased protein concentration and leukocyte counts, partially restoring them compared to the TMP group. ELISA results (Fig. 6h–j) showed a notable rise in TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expression in the LPS group compared to the control group. However, both the LPS + TMP group and the LPS + Dex group reduced inflammatory factor expression. In the LPS + TMP + miR-369-3p-sponge group, TMP's ameliorative effects on LPS-induced inflammation were partially eliminated.

Knockdown of miR-369-3p partially counteracts the protection of TMP in LPS-induced ALI mice. (a,b) HE staining and lung injury score. (c,d) A tail intravenous injection of EB was administered, and lung tissue dye was extracted and quantified after 2 h. (e) Lung wet-to-dry ratio. (f) Total protein concentration in BALF. (g) Leukocyte count in BALF. The expression levels of IL-6 (h), TNF-α (i), and IL-1β (j) in BALF. Data are presented as means ± SD (n ≥ 3). One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey's test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

TMP reduces the severity of LPS-induced ALI through upregulation of miR-369-3p/DSTN/ZO-1/occludin

In order to elucidate the mechanism by which TMP alleviates ALI, we down-regulated miR-369-3p on the basis of TMP treatment and detected the expression of related proteins (Fig. 7a). The results showed that the expression of DSTN, ZO-1 and occludin in TMP and Dex groups increased compared with that in LPS group. After down-regulating miR-369-3p, the expression of DSTN, ZO-1 and occludin decreased compared with that in TMP group. Results of immunofluorescence of ZO-1 and occluding (Fig. 7b) were in agreement with the results of Western blot. In our studies, miR-369-3p was found to reverse TMP's inhibitory effects on the DSTN/ZO-1/occludin pathway when it was downregulated. These results indicate that TMP improves LPS-induced ALI by regulating the miR-369-3p/DSTN/ZO-1/occludin pathway.

TMP reduces the severity of LPS-induced acute lung injury through upregulation of miR-369-3p/DSTN/ZO-1/occludin. (a,b) Western bolt and immunofluorescence detects the expression of actin depolymerization factor-DSTN, tight junction protein ZO-1, and occludin protein in lung tissue. Data are presented as means ± SD (n ≥ 3). One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

Endothelial barrier dysfunction resulting in heightened pulmonary vascular permeability, protein-rich fluid extravasation, and pulmonary edema are characteristic features of ALI and ARDS33. The current investigation revealed that TMP significantly ameliorated lung function, pulmonary injury, pulmonary edema, and pulmonary inflammation in LPS-induced ALI mice.

The maintenance of endothelial barrier integrity is contingent upon the structural integrity of the cytoskeleton and cellular connections34. The main function of DSTN is to bind actin by cutting actin filaments, making it an essential factor for cell structure, growth, development, and differentiation10. Research has demonstrated that DSTN can enhance actin dynamics through various mechanisms, including accelerating the depolymerization of terminal monomers, cleaving actin filaments into shorter proproteins, and directly or indirectly stimulating the growth of actin filaments10,35. Among all family members, DSTN exhibits the most potent depolymerization activity, leading to actin depolymerization, decreased actin aggregation, cytoskeletal remodeling, and ultimately impacting endothelial cell function36.

Pulmonary vascular endothelial cells are arranged in a continuous monolayer to form a tight barrier6, which is composed of tight junctions (TJs), adhesion junctions (AJs) and gap junctions (GJs)37. Among them, TJs regulates the transpermeability of endothelial cells by regulating the diffusion of fluids, ions and some cytokines, which is very important for maintaining vascular homeostasis38, while AJs protein is mainly responsible for maintaining the adhesion and stability of endothelial cells to cells, forming strong mechanical connections between neighboring cells, and playing a role in the mechanical maintenance of TJs tissues, while GJs connects the matrix and is primarily responsible for intercellular communication39. Among them, TJs are crucial components of the endothelial barrier, and alterations in their structure can lead to the disruption of cell–cell adhesion, resulting in increased permeability and leakage of fluids containing macromolecules and cytokines. This disturbance in barrier function can have significant implications for vascular homeostasis, potentially leading to organ and tissue damage in severe cases. In TJs, occludin is the main transmembrane protein, while ZO-1 is the direct junction protein between actin cytoskeleton and transmembrane protein40. In this study, we found that there was a decrease expression of ZO-1 and occludin and cytoskeletal regulatory proteins DSTN in LPS group, while the expression of proteins significantly recovered after the intervention of TMP. These results show that TMP exerts a protective effect on ALI by regulating the DSTN/ZO-1/occludin pathway.

With miRNAs emerging as important regulators in various biological processes, many recent studies have highlighted their potential as biomarkers of ALI and their importance in biopharmaceutical applications41. In light of their role as regulators of gene expression in ALI, we conducted high-throughput sequencing analysis on lung tissue samples obtained from mice subjected to ALI and treated with TMP. Our findings, illustrated in Fig. 2a, revealed 59 differentially expressed microRNAs, with 29 showing decreased expression following LPS-inducted and increased expression post-TMP protection. Subsequently, Targetscan 8.0 and miRWalk 3.0 software were utilized to predict the binding interactions between the microRNAs identified through high-throughput sequencing and the gene DSTN, leading to the identification of miR-369-3p as a potential target of DSTN. We postulate that miR-369-3p may play a significant role in the mechanism of action of TMP. At present, it has been found that the miR-369-3p expression is decreased in the inflammatory region of inflammatory bowel patients, and the up-regulation of miR-369-3p can alleviate the LPS-induced inflammatory response42. It has also been found that downregulating long-chain noncoding RNA DLEU2 based on the miR-369-3p/TRIM2 axis can inhibit idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis43. Nevertheless, the role of miR-369-3p in ALI remains inadequately investigated. To substantiate our hypothesis, we modulated the expression of miR-369-3p in accordance with the ALI model to elucidate its significance in the pathogenesis of ALI. Our findings indicate that up-regulation of miR-369-3p can ameliorate LPS-induced ALI by enhancing lung function, reducing pulmonary edema, decreasing pulmonary vascular permeability, and alleviating pulmonary inflammation. On the contrary, the reduction of miR-369-3p exacerbated endothelial barrier dysfunction, leading to significant impairment of lung function, heightened pulmonary edema, and elevated levels of pro-inflammatory mediators. To investigate the effort of miR-369-3p, we conducted additional analysis on the expression of associated proteins, revealing that stimulation with LPS led to a decrease in the expression of DSTN, as well as tight junction proteins ZO-1 and occludin, in comparison to the control group. The up-regulation of DSTN, ZO-1, and occludin expression in response to over-expression of miR-369-3p contrasts with the down-regulation of these proteins in the presence of down-regulated miR-369-3p. These results suggest a significant role for miR-369-3p in ALI.

Nevertheless, there is a lack of evidence supporting the miR-369-3p's involvement in TMP's protective mechanism against ALI. To address this issue, we conducted experiments involving the down-regulation of miR-369-3p following TMP treatment for ALI. Our findings indicate that TMP and Dex effectively mitigate lung injury and pneumonia, as well as improve lung endothelial barrier function, in comparison to the LPS group. Furthermore, a comparison between the TMP group and the down-regulated miR-369-3p group revealed an increase in lung injury, lung water content, pneumonia, and lung endothelial barrier permeability in the latter. In order to further investigate the specific mechanism of action, Western blot and immunofluorescence techniques were utilized to detect the expressions of DSTN, ZO-1, and occludin. Comparison with the TMP group revealed that down-regulation of miR-369-3p impeded the recovery of pathway proteins. Therefore, as illustrated in Fig. 8, this study demonstrates that TMP can enhance ALI by up-regulating miR-369-3p, subsequently promoting the expression of DSTN, ZO-1, and occludin, reducing pulmonary vascular permeability, and safeguarding against LPS-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction.

The graphic illustration of the mechanism of TMP ameliorating LPS-induced pulmonary endothelial barrier dysfunction. LPS induced a decrease in miR-369-3p expression in ALI mice, which in turn led to a decrease in DSTN expression, depolymerization of F-actin into G-actin, impairment of cellular TJ proteins, increase in endothelial intercellular permeability, and dysfunction of the endothelial barrier, which was improved by TMP treatment.

Overall, this study provides valuable insights into miRNA-targeting ALI drugs' potential therapeutic effects and provides foundational research data for the clinical utilization of TMP in the treatment of ALI.

Materials and methods

Animal and animal grouping

All animal experiments in this work were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Six-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (20 ± 2 g) were procured from Henan Skibbes Biotechnology Co. Ltd [License No. SCXK (Yu) 2020-0005, Henan, China] and underwent quality testing at Shandong Laboratory Animal Center. Mice were housed under standard laboratory conditions with a temperature of 20 ± 2 °C and humidity at 60 ± 2%. Adequate water and feed were provided during a one-week acclimatization period. The male C57BL/6J mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups, (1) control, (2) LPS, (3) LPS + GFP, (4) LPS + miR-369-3p-Null, (5) LPS + miR-369-3p-sponge, (6) LPS + TMP, (7) LPS + TMP + miR-369-3p-sponge, (8) LPS + Dex.

Model building

In the "two-hit" model, C57BL/6J mice were intraperitoneally injected with LPS at a dose of 2 mg/kg, followed by a subsequent administration of LPS at a dosage of 4 mg/kg via tracheal drip after a 16-h interval. The negative control group received phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in equivalent volumes. The drug treatment groups, comprising TMP (80 mg/kg) or Dex (3 mg/kg), received intraperitoneal injections 30 min before the first LPS injection and 30 min after the second LPS injection. The adenovirus group underwent tracheal drip of 5 × 109 viral particles one week before ALI model.

Blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) and lung index

After modeling, mice were placed in a gas anesthesia machine induction chamber to induce anesthesia using isoflurane. After they are anesthetized, the SpO2 of mice was measured using the PhysioSuite™ Small Animal Respiratory Detection System, ensuring the mice were in a suitable state of anesthesia. Following completion of the modeling, the weight of mice was recorded. After mice were euthanized by inhalation of isoflurane, lung tissues were extracted after opening the thoracic cavities. Lung weight was measured after removing surface blood using filter paper. The lung index was calculated using the formula: Lung index = A/B × 100, where A is the lung weight, and B is the body weight.

Hematoxylin–eosin (HE)

After mice were euthanized by inhalation of isoflurane, the lungs were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde after being removed and cleaned, then the tissues in each group were dehydrated by alcohol gradient, embedding, sectioning staining (the sections were baked for 30 min before staining), sealing. Subsequently, the lung tissues were air-dried and examined under a light microscope to observe any pathological changes. Under low magnification, the presence of inflammatory cell infiltration, edema, and lung tissue damage were noted, and the distribution of lung damage was evaluated. Under high magnification, the alveolar structures were identifiable, allowing for the assessment and scoring of the extent of lung damage.

Scoring method: 6 fields of view were taken for hemorrhage and edema scoring.

-

Score 0: no damage

-

Score 1: < 25% of the damaged area

-

Score 2: 25–50% of the damaged area

-

Score 3: 50–75% of the damaged area

-

Score 4: > 75% of the damaged area

Evans Blue (EB)

Mice were injected with 50 mg/kg EB via the tail vein. After 2 h, the mice were euthanized by inhalation of isoflurane. Subsequently, the thoracic cavity was cut open to expose the lungs and heart, and the left auricle was cut open and rinsed from the right apex of the heart with saline in a 2.5 ml syringe until the effluent from the left atrium became colorless. Following this, lung tissues were collected and the optical density (OD) values were measured by extraction with formamide.

Lung wet/dry weight ratio (W/D)

The lung wet/dry weight ratio reflects lung tissue edema. Mice were euthanized by inhalation of isoflurane, and lung tissues were removed. After drying surface blood, the tissues were immediately weighed (as wet weight) and then placed in an oven at 60 °C until a constant weight was achieved (as dry weight). The ratio before and after drying was calculated.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) collection and analysis

Mice were euthanized by inhalation of isoflurane, exposing the trachea for endotracheal intubation. Lungs were gently irrigated with 2 × 0.8 ml of pre-cooled PBS, followed by slow back-extraction. After centrifugation at 1000 rpm/min for 10 min, the recovered liquid was collected and stored at − 80 °C. The supernatant was used for assessing the concentration of inflammatory factors by ELISA. The resulting precipitate, after centrifugation and addition to red blood cell lysate, was resuspended and counted using a hemocytometer.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from lung tissue using Trizol reagent. For inflammatory factors, RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the reverse transcription kit HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+ gDNA wiper), and then the reaction system was configured using the AceQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix kit. For microRNA, the All-in-One™ miRNA First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit 2.0 was used to convert RNA into cDNA. Subsequently, the All-in-One™ miRNA qRT-PCR Detection Kit 2.0 was used for qPCR reactions. Finally, Rcvhe-LightCycler480 was used for PCR amplification. Primers were synthesized by Sangon (Shanghai, China). The primers involved in the study are listed in Table 1. The 2−ΔΔCT method was employed for quantitative analysis of qPCR data.

Western blot

The total amount of proteins in lung tissue was extracted with RIPA lysate and their concentration calculated with a BCA protein kit. After SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and sealed with 5% skimmed milk. The membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies (anti-DSTN, 1:1000, Abcam; anti-ZO-1, 1:1000, Abcam; anti-occludin, 1:1000, Abcam; anti-GAPDH, 1:10,000, ABclonal). Following this, membranes were incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibody (HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibodies, biosharp, 1:8000) for 2 h at room temperature, and protein blots were visualized using the ECL kit. We quantified the density of the protein bands by using Image J.

Immunofluorescence

The paraffin sections and dewaxing solution 1 were subjected to a temperature of 55 °C for a duration of 30 min in a roaster. Subsequently, the sections were sequentially immersed in dewaxing solution 1, dewaxing solution 2, dewaxing solution 3, anhydrous ethanol 1, anhydrous ethanol 2, and anhydrous ethanol 3 for 5 min each. Following this, the sections were repaired, closed, incubated with the primary antibody overnight (anti-DSTN, 1:200, Abcam; anti-ZO-1, 1:200, Abcam; anti-occludin, 1:200, Abcam), incubated with the CY3-labeled fluorescent secondary antibody (Cy3-conjugated Goat anti-Rabbit IgG, 1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch) protected from light, stained for nuclei by DAPI, and sealed, and finally placed in a Zeiss Finally, the sections were placed under a Zeiss fluorescence inverted microscope to collect images.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis employed non-parametric methods. GraphPad Prism 9 was used to analyze results, expressed as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA assessed differences between multiple groups, and Tukey's multiple comparisons test calculated differences between two groups. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We are following the Animal Research: Reporting of in vivo Experiments [ARRIVE] guidelines. And euthanasia of mice in this study complied with the [ARRIVE] guidelines. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bengbu Medical College. All the methods used in this study were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data availability

The Targetscan 8.0 (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/) and miRWalk 3.0 (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/) is used to predict the correlation between DSTN and miR-369-3p. And all data are publicly accessible, open access, and support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, YL, upon reasonable request. Data relevant to this study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

References

Mokrá, D. Acute lung injury—From pathophysiology to treatment. Physiol. Res. 69, S353–S366. https://doi.org/10.33549/physiolres.934602 (2020).

Zhao, Y., Ridge, K. & Zhao, J. Acute Lung injury, repair, and remodeling: Pulmonary endothelial and epithelial biology. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 9081521. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9081521 (2017).

Kumar, V. Pulmonary innate immune response determines the outcome of inflammation during pneumonia and sepsis-associated acute lung injury. Front. Immunol. 11, 1722. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01722 (2020).

Luh, S. P. & Chiang, C. H. Acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ALI/ARDS): The mechanism, present strategies and future perspectives of therapies. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 8, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.2007.B0060 (2007).

Dushianthan, A., Grocott, M. P., Postle, A. D. & Cusack, R. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute lung injury. Postgrad. Med. J. 87, 612–622. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2011.118398 (2011).

Orfanos, S. E., Mavrommati, I., Korovesi, I. & Roussos, C. Pulmonary endothelium in acute lung injury: From basic science to the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 30, 1702–1714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-004-2370-x (2004).

Han, X. et al. Tetramethylpyrazine attenuates endotoxin-induced retinal inflammation by inhibiting microglial activation via the TLR4/NF-κB signalling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 128, 110273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110273 (2020).

Su, Y. et al. Construction of bionanoparticles based on Angelica polysaccharides for the treatment of stroke. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 44, 102570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2022.102570 (2022).

Min, S. et al. Tetramethylpyrazine ameliorates acute lung injury by regulating the Rac1/LIMK1 signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1005014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1005014 (2022).

Maciver, S. K. & Hussey, P. J. The ADF/cofilin family: Actin-remodeling proteins. Genome Biol. 3, reviews3007. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2002-3-5-reviews3007 (2002).

Bernstein, B. W. & Bamburg, J. R. ADF/cofilin: A functional node in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2010.01.001 (2010).

McGough, A., Pope, B., Chiu, W. & Weeds, A. Cofilin changes the twist of F-actin: Implications for actin filament dynamics and cellular function. J. Cell Biol. 138, 771–781. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.138.4.771 (1997).

Wen, R. et al. DSTN hypomethylation promotes radiotherapy resistance of rectal cancer by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 117, 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2023.03.067 (2023).

Zhang, H. J. et al. Destrin contributes to lung adenocarcinoma progression by activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR 18, 1789–1802. https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.Mcr-20-0187 (2020).

Liu, X., Zhang, R., Di, H., Zhao, D. & Wang, J. The role of actin depolymerizing factor in advanced glycation endproducts-induced impairment in mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 433, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-017-3019-8 (2017).

Wang, J., Sun, L., Si, Y. F. & Li, B. M. Overexpression of actin-depolymerizing factor blocks oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced mouse brain microvascular endothelial cell barrier dysfunction. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 371, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-012-1415-7 (2012).

O’Brien, J., Hayder, H., Zayed, Y. & Peng, C. Overview of microRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 9, 402. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00402 (2018).

Fabian, M. R., Sonenberg, N. & Filipowicz, W. Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 351–379. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103 (2010).

Bartel, D. P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5 (2004).

Pasquinelli, A. E. MicroRNAs and their targets: Recognition, regulation and an emerging reciprocal relationship. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3162 (2012).

Majid, S. et al. MicroRNA-205-directed transcriptional activation of tumor suppressor genes in prostate cancer. Cancer 116, 5637–5649. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25488 (2010).

Matsui, M. et al. Promoter RNA links transcriptional regulation of inflammatory pathway genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 10086–10109. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt777 (2013).

Guo, D., Barry, L., Lin, S. S., Huang, V. & Li, L. C. RNAa in action: From the exception to the norm. RNA Biol. 11, 1221–1225. https://doi.org/10.4161/15476286.2014.972853 (2014).

Huang, V. et al. Upregulation of Cyclin B1 by miRNA and its implications in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 1695–1707. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr934 (2012).

Place, R. F., Li, L. C., Pookot, D., Noonan, E. J. & Dahiya, R. MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1608–1613. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707594105 (2008).

Turner, M. J., Jiao, A. L. & Slack, F. J. Autoregulation of lin-4 microRNA transcription by RNA activation (RNAa) in C. elegans. Cell Cycle 13, 772–781. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.27679 (2014).

Xiao, M. et al. MicroRNAs activate gene transcription epigenetically as an enhancer trigger. RNA Biol. 14, 1326–1334. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2015.1112487 (2017).

Rajasekaran, S., Pattarayan, D., Rajaguru, P., Sudhakar Gandhi, P. S. & Thimmulappa, R. K. MicroRNA regulation of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Cell. Physiol. 231, 2097–2106. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.25316 (2016).

Ju, M. et al. MicroRNA-27a alleviates LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice via inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis through modulating TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway. Cell Cycle 17, 2001–2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384101.2018.1509635 (2018).

Xie, W. et al. miR-34b-5p inhibition attenuates lung inflammation and apoptosis in an LPS-induced acute lung injury mouse model by targeting progranulin. J. Cell. Physiol. 233, 6615–6631. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.26274 (2018).

Scalavino, V. et al. miR-369-3p modulates inducible nitric oxide synthase and is involved in regulation of chronic inflammatory response. Sci. Rep. 10, 15942. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72991-8 (2020).

Scalavino, V. et al. A novel mechanism of immunoproteasome regulation via miR-369-3p in intestinal inflammatory response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232213771 (2022).

Fan, E., Brodie, D. & Slutsky, A. S. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA 319, 698–710. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.21907 (2018).

Kása, A., Csortos, C. & Verin, A. D. Cytoskeletal mechanisms regulating vascular endothelial barrier function in response to acute lung injury. Tissue Barriers 3, e974448. https://doi.org/10.4161/21688370.2014.974448 (2015).

Andrianantoandro, E. & Pollard, T. D. Mechanism of actin filament turnover by severing and nucleation at different concentrations of ADF/cofilin. Mol. Cell 24, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.006 (2006).

Carbó, C. et al. Differential expression of proteins from cultured endothelial cells exposed to uremic versus normal serum. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 51, 603–612. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.029 (2008).

Tsukita, S., Furuse, M. & Itoh, M. Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1038/35067088 (2001).

Cerutti, C. & Ridley, A. J. Endothelial cell-cell adhesion and signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 358, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.06.003 (2017).

Dejana, E. & Giampietro, C. Vascular endothelial-cadherin and vascular stability. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 19, 218–223. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283523e1c (2012).

Chiba, H., Osanai, M., Murata, M., Kojima, T. & Sawada, N. Transmembrane proteins of tight junctions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778, 588–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.017 (2008).

Lu, Q. et al. MicroRNAs: Important regulatory molecules in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23105545 (2022).

Scalavino, V. et al. miR-369–3p modulates intestinal inflammatory response via BRCC3/NLRP3 inflammasome axis. Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12172184 (2023).

Yi, H., Luo, D., Xiao, Y. & Jiang, D. Knockdown of long non-coding RNA DLEU2 suppresses idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis by regulating the microRNA-369-3p/TRIM2 axis. Int. J. Mol. Med. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2021.4913 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81673791), Changzhou University Funds (ZMF22020010), Provincial Graduate Innovation Practice Program (2022cxcysj170), Postgraduate Research Innovation Project of Bengbu Medical College in 2022 (Byycxz22006), Science and Technology Program of Suzhou City (SZKJXM202319), Health Research Project of Anhui Province (AHWJ2023A30100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WT, SM and YL. conceived and designed the study, drafting manuscript. WT, SM, LL and JC. conducted experimental work. WT, SM, GC, YM, XH, LL and JC. analyzed the data, interpreted the results. WT, SM and YL. revision manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tao, W., Min, S., Chen, G. et al. Tetramethylpyrazine ameliorates LPS-induced acute lung injury via the miR-369-3p/DSTN axis. Sci Rep 14, 20006 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70131-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70131-0