Abstract

One of the most common causes of peritoneal dialysis withdrawal is ultrafiltration failure which is characterized by peritoneal membrane thickening and fibrosis. Although previous studies have demonstrated the inhibitory effect of p38 MAPK inhibitors on peritoneal fibrosis in mice, it was unclear which specific cells contribute to peritoneal fibrosis. To investigate the role of p38 MAPK in peritoneal fibrosis more precisely, we examined the expression of p38 MAPK in human peritoneum and generated systemic inducible p38 MAPK knockout mice and macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice. Furthermore, the response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was assessed in p38 MAPK-knocked down RAW 264.7 cells to further explore the role of p38 MAPK in macrophages. We found that phosphorylated p38 MAPK levels were increased in the thickened peritoneum of both human and mice. Both chlorhexidine gluconate (CG)-treated systemic inducible and macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice ameliorated peritoneal thickening, mRNA expression related to inflammation and fibrosis, and the number of αSMA- and MAC-2-positive cells in the peritoneum compared to CG control mice. Reduction of p38 MAPK in RAW 264.7 cells suppressed inflammatory mRNA expression induced by LPS. These findings suggest that p38 MAPK in macrophages plays a critical role in peritoneal inflammation and thickening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a renal replacement therapy characterized by the preservation of residual renal function, the minimal impact on the cardiovascular system, and the improvement of quality of life1. Despite its advantages over hemodialysis, long-term PD can cause peritoneal membrane dysfunction, a major cause of PD withdrawal2. During PD, peritoneal tissues are constantly exposed to non-biocompatible PD fluid, causing various histopathological changes such as loss of peritoneal mesothelial cells, thickening of the submesothelial layer, peritoneal fibrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, and angiogenesis, ultimately resulting in peritoneal dysfunction3,4. The effects of inflammatory cytokines5, exposure to high concentrations of PD fluid6, and advanced glycation end products (AGE) production7 have been suggested as causes of peritoneal thickening, but the specific molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

One type of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) that responds to stress stimuli such as cytokines, ultraviolet irradiation, hypoxia, and osmotic change is p38 MAPK8,9. Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK triggers its translocation to the nucleus10 and the activation of transcription factors involved in production of proinflammatory mediators and extracellular matrix proteins11. The p38 MAPK has four isoforms; α, β, γ, and δ, of which p38α is ubiquitously expressed12. In various mouse experimental disease models, including rheumatoid arthritis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)13, phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (p38α) at the site of injury was enhanced, and p38 MAPK inhibitors alleviated disease-induced damage14. Inhibition of p38 MAPK has also been reported to be effective in ameliorating renal fibrosis or ischemic heart injury.

Our group previously reported that chlorhexidine gluconate (CG) administration in mice causes peritoneal fibrosis and CG administration enhances phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in damaged peritoneum15. It has been also reported that administration of FR167653, a MAPK inhibitor, suppressed phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in murine peritoneal mesothelial cells and fibrocyte leading to amelioration of peritoneal fibrosis and mRNA change16.Although phosphorylation of p38 MAPK can occur in various cell types17, it remains unclear which cells' p38 MAPK contributes to peritoneal fibrosis. Human peritoneal mesothelial cells (HPMC) are known to produce extracellular matrix (ECM) components, like collagen fibers and fibronectin, and contribute to peritoneal thickening18. Previous studies have demonstrated that angiotensin II or high concentrations of glucose enhance p38 MAPK phosphorylation in HPMC, leading to increased expression of fibronectin and related mRNAs, effects that were suppressed by the administration of MAPK inhibitors19,20. These findings suggested the importance of p38 MAPK in peritoneal fibrosis and its potential as a therapeutic target. However, it has not been demonstrated which cells are important for peritoneal fibrosis.

Various cells including mesothelial cells and fibroblasts are involved in peritoneal fibrosis, the involvement of immune cells has attracted attention recently. Cytokines such as TGF-β or IL-6 from macrophages had crucial role in progression of peritoneal deterioration21, and macrophage depletion attenuated peritoneal thickening and suppressed TGF-β1 expression in CG-treated rat peritoneum22. However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying macrophage-induced peritoneal fibrosis remain unclear. We therefore focused on p38 MAPK in macrophages and generated drug-inducible systemic p38 MAPK (p38α) knockout mice and congenital macrophage-specific p38α knockout mice to examine its effect on peritoneal fibrosis.

Results

Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was enhanced in impaired human and mouse peritoneum and peritoneal thickening and inflammation induced by CG administration was suppressed in systemic conditional p38 MAPK knockout mice

First, we investigated phosphorylated p38 MAPK in human peritoneal biopsy samples. Phosphorylated p38 MAPK was primarily detected in mesothelium of the peritoneum obtained at the time of catheter insertion in a 63-year-old male nephrosclerosis patient and a 64-year-old male chronic glomerulonephritis patient. In contrast, phosphorylated p38 MAPK was increased in cells within the mesothelium and submesothelial area of the peritoneum at the time of catheter removal due to peritoneal dysfunction after 11 years of PD in a 76-year-old female IgA nephropathy patient and a 69-year-old female IgA nephropathy patient (Fig. 1a). None of the patients had active infectious diseases at the time of surgery, nor history of recurrent peritonitis.

Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in human and mouse peritoneum and generation of systemic p38 MAPK knockout mice. (a) Immunohistochemistry of phosphorylated p38 MAPK in the human peritoneum at the time of catheter insertion (beginning) in a 63-year-old male nephrosclerosis patient (left panel) and a 64-year-old male chronic glomerulonephritis patient (right panel), and at the time of catheter removal (withdrawal) after 11 years of peritoneal dialysis in a 76-year-old female IgA nephropathy patient (left panel) and a 69-year-old female IgA nephropathy patient (right panel). (b) Schema of the experimental protocol. Male ROSA26-CreERT2; p38αfl/fl mice or control [p38αfl/fl, Cre (−)] mice were treated with 0.2 mg/gBW (body weight) tamoxifen orally for 5 days at 8–9 weeks of age. Systemic p38 KO or control mice at 13–15 weeks of age were treated with intraperitoneal injection of 0.1% chlorhexidine gluconate (CG) at 0.01ml/gBW dissolved in 15% ethanol and 85% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), or PBS alone, three times a week for 3 weeks. (c) Expression of peritoneal Mapk14 mRNA in control or systemic p38 MAPK knockout mice with PBS or CG. Ctrl PBS; n = 9, systemic p38 KO PBS; n = 9, Ctrl CG; n = 11, systemic p38 KO CG; n = 11. (d) Double immunofluorescence staining for phosphorylated p38 MAPK (p-p38) and F4/80 in control and systemic p38 MAPK knockout mice in PBS- or CG-treated mouse peritoneum. Triangles indicate double positive cells. High magnification images of immunofluorescence staining for p-p38, F4/80, and DAPI in control and systemic p38 MAPK knockout mice in CG-treated mouse peritoneum. Ctrl; control mice, Systemic p38 KO; systemic p38 MAPK knockout mice. LPF; Low power field, HPF; High power field, Scale bars represent 100 µm. Values are expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

We examined whether deletion of p38α MAPK can ameliorate peritoneal fibrosis using tamoxifen-inducible systemic conditional p38 knockout (systemic p38 KO) mice, as systemic conventional p38 MAPK knockout mice result in embryonic death23. To evaluate the efficacy of p38 MAPK deletion in systemic p38 KO mice, we examined p38 MAPK in the peritoneum by real-time PCR analysis and immunofluorescence (Fig. 1b–d). Peritoneal mRNA expression of Mapk14 was reduced by 80% in PBS-treated systemic p38 KO mice compared to PBS-treated control mice and decreased by 75% in CG-treated systemic p38 KO mice compared with CG-treated control mice (Fig. 1c). A double immunofluorescent staining of phosphorylated p38 MAPK (p-p38) and F4/80, a macrophage marker, was performed to identify the specific cells in which p38 MAPK was phosphorylated. F4/80-positive cells were abundant in CG-treated peritoneum, and phosphorylated p38 MAPK was significantly upregulated in F4/80-positive cells (Fig. 1d). These partial reductions are primarily due to drug-inducible conditional knockout system. Systemic p38 KO mice treated with CG had fewer phosphorylated p38 MAPK positive cells and F4/80-positive cells compared to CG-treated control mice (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. S1).

There were no histological changes in the peritoneum between PBS-treated control and systemic p38 KO mice (Fig. 2a). Control mice treated with CG showed marked thickening of the peritoneum (Fig. 2a). In contrast, peritoneal thickening was significantly suppressed in CG-treated systemic p38 KO mice compared to CG-treated control mice (Fig. 2a). Quantitative analysis of peritoneal thickness revealed 52% reduction in peritoneal fibrosis in systemic p38 KO mice (374.2 µm in control mice vs. 178.9 µm in systemic p38 KO mice; Fig. 2b). Additionally, immunohistochemical staining of type I collagen and Sirius red staining (Supplementary Figs. S6, S7) confirmed that collagen fibers induced by CG administration were suppressed in systemic p38 MAPK conditional knockout mice.

Systemic deletion of p38 MAPK ameliorated peritoneal thickening and fibrosis. (a) Representative images of Masson’s trichrome staining of the peritoneum after 3 weeks of PBS or CG injection in control and systemic p38 MAPK KO mice. Double-headed arrows indicate the submesothelial zone. (b) Mean peritoneal membrane thickness of the submesothelial zone. (c) Peritoneal mRNA expression levels of Il1b, Il6, Emr1, Tlr4, Col1a1, Acta2, Fn1, and Ctgf in control and systemic p38 MAPK KO mice treated with PBS or CG three times for 3 weeks. Ctrl; control mice, Systemic p38 KO; systemic p38 MAPK knockout mice. Scale bars represent 100 µm. Values are expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

We further examined peritoneal mRNA expression using real-time PCR. The mRNA expression of Il1b, Emr1, Tlr4, Col1a1, Acta2, Fn1, and Ctgf was upregulated in CG-treated control mice and significantly suppressed in CG-treated systemic p38 KO mice, whereas the expression of Il6, Ccl2, and Il10 showed no significant difference with systemic p38 MAPK deletion (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. S2). Immunohistochemical staining of α smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and macrophage antigen-2 (MAC-2) was performed to assess the effects of systemic p38 MAPK deletion. The number of αSMA- and MAC-2-positive cells was significantly increased in the peritoneum of CG-treated control mice and was reduced in systemic p38 KO mice (Fig. 3a–d). These results suggest that systemic deletion of p38 MAPK reduces peritoneal fibrosis and inflammation.

Immunohistochemical staining of αSMA and MAC-2 in control and systemic p38 MAPK KO mice. (a) Immunohistochemical staining of αSMA in the peritoneum of control and systemic p38 KO mice treated with PBS or CG, shown in photomicrographs at low and high magnification. (b) The number of αSMA-positive cells in the peritoneum. (c) Immunohistochemical staining of MAC-2 in the peritoneum, shown in photomicrographs at low and high magnification. (d) The number of MAC-2-positive cells in the peritoneum. LPF; Low power field, HPF; High power field, Scale bars represent 100 µm. Ctrl; control mice, Systemic p38 KO; systemic p38 MAPK knockout mice. Ctrl PBS; n = 9, systemic p38 KO PBS; n = 9, Ctrl CG; n = 11, systemic p38 KO CG; n = 11. Values are expressed as means ± SD. **P < 0.01.

Peritoneal thickening and inflammation induced by CG administration were suppressed in macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice as well as in systemic p38 MAPK conditional knockout mice

In this study, systemic p38 KO mice demonstrated attenuation of peritoneal thickening and inflammation induced by CG. These results are consistent with previous reports on the effects of p38 MAPK inhibitors against peritoneal damage16. However, since p38 MAPK is ubiquitously expressed, it is still unclear which cells are major contributors to peritoneal thickening and inflammation. Our results suggested that macrophage would be the cause of p38 MAPK-related peritoneal thickening. Therefore, we focused on macrophages and conducted studies using macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice to more precisely examine the role of cell-specific p38 MAPK.

To evaluate the efficacy of p38 MAPK deletion in macrophage-specific p38 knockout (p38ΔMΦ KO) mice, we analyzed p38 MAPK expression in the peritoneum using real-time PCR and immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 4a and b). There was no change in peritoneal mRNA expression of Mapk14 between PBS-treated p38ΔMΦ KO and control mice, whereas peritoneal Mapk14 mRNA expression was reduced by 35% in CG-treated p38ΔMΦ KO mice compared to CG-treated control mice (Fig. 4b). Immunofluorescent analysis of phosphorylated p38 MAPK revealed a reduction in the number of phosphorylated p38 MAPK positive cells in CG-treated peritoneum was reduced in p38ΔMΦ KO mouse peritoneum compared to control mice (Fig. 4c). Additionally, F4/80-positive cells were reduced in p38ΔMΦ KO mice, and phosphorylated p38 MAPK positive macrophages were scarcely observed (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. S1).

Generation of macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice. (a) Macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice or control mice at 13–15 weeks of age were treated by intraperitoneal injection of CG or PBS three times a week for 3 weeks. (b) Expression of peritoneal Mapk14 mRNA in control or macrophage-specific p38 knockout mice with PBS or CG. Ctrl PBS; n = 6, p38ΔMΦ KO PBS; n = 6, Ctrl CG; n = 11, p38ΔMΦKO CG; n = 11. (c) Double immunofluorescence staining for p-p38 and F4/80 in control and macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice in PBS- or CG-treated mouse peritoneum. Triangles indicate double positive cells. High magnification of immunofluorescence staining for p-p38, F4/80 and DAPI in control and macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice in CG-treated mouse peritoneum. Ctrl; control mice, p38ΔMΦ KO; macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice. Scale bars represent 100 µm. Values are expressed as means ± SD. n.s.; not significant, **P < 0.01.

CG-induced peritoneal thickening was significantly suppressed in p38ΔMΦ KO mice compared to control mice (Fig. 5a), consistent with findings in systemic p38 KO mice. Quantitative study of peritoneal thickness revealed 43% reduction in peritoneal fibrosis in CG-treated p38ΔMΦ KO mice (280.6 µm in CG control mice vs. 160.7 µm in CG p38ΔMΦ KO mice; Fig. 5b). Immunohistochemical staining of type I collagen and Sirius red staining of the peritoneum (Supplementary Figs. S6, S7) confirmed that peritoneal collagen fibers induced by CG administration in the peritoneum were suppressed in macrophage-specific p38 MAPK conditional knockout mice, as well as systemic p38 MAPK knockout mice. Furthermore, peritoneal mRNA expression of Il1b, Il6, Emr1, Tlr4, Col1a1, Acta2, Fn1, and Ctgf was upregulated in CG-treated control mice, and this expression was significantly suppressed in CG-treated p38ΔMΦ KO mice (Fig. 5c). The mRNA expression in Ccl2 and Il10 did not show significant changes, consistent with findings in systemic p38 KO mice (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Macrophage-specific deletion of p38 MAPK also ameliorated peritoneal thickening and fibrosis. (a) Representative images of Masson’s trichrome staining of the peritoneum after 3 weeks of PBS or CG injection in control and macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice. Double-headed arrows indicate the submesothelial zone. (b) Mean peritoneal membrane thickness of the submesothelial zone. (c) Peritoneal mRNA expression levels of Il1b, Il6, Emr1, Tlr4, Col1a1, Acta2, Fn1, and Ctgf in control and macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice treated with PBS or CG three times per week for 3 weeks. Ctrl; control mice, p38ΔMΦ KO; macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice. Scale bars represent 100 µm. Values are expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Immunohistochemical staining of αSMA and MAC-2 was performed to quantify the number of myofibroblasts and macrophages. The number of αSMA-positive cells was significantly increased in the peritoneum of CG-treated control mice and was reduced in CG-treated p38ΔMΦ KO mice (Fig. 6a and b), as was the number of MAC-2-positive cells (Fig. 6c and d). These findings suggested that macrophage-specific deletion of p38 MAPK also mitigated peritoneal fibrosis and inflammation, highlighting the crucial role of p38 MAPK in macrophage-mediated peritoneal fibrosis and inflammation.

Immunohistochemical staining of αSMA and MAC-2 in control and macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice. (a) Immunohistochemical staining of αSMA in the peritoneum of control and macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice treated with PBS or CG, shown in photomicrographs at low and high magnification. (b) The number of αSMA-positive cells in the peritoneum. (c) Immunohistochemical staining of MAC-2 in the peritoneum, shown in photomicrographs at low and high magnification. (d) The number of MAC-2-positive cells in the peritoneum. LPF; Low power field, HPF; High power field, Scale bars represent 100 µm. Ctrl; control mice, p38ΔMΦ KO; macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice. Ctrl PBS; n = 6, p38ΔMΦ KO PBS; n = 6, Ctrl CG; n = 11, p38ΔMΦKO CG; n = 11. Values are expressed as means ± SD. **P < 0.01.

p38 MAPK knockdown in mouse macrophages suppressed the expression of proinflammatory cytokines induced by LPS

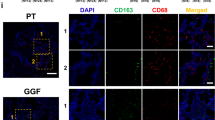

To further evaluate the findings from in vivo experiments, we conducted the experiment of p38 MAPK reduction using RAW 264.7 cells, mouse macrophage cell line. RAW 264.7 cells were transfected with siRNA for Mapk14 (si-Mapk14) or negative control (si-NC). After 24 h, cells were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 100 ng/ml) for 2 h (Fig. 7a). The knockdown of p38 MAPK led to a suppression of total p38 MAPK protein levels and LPS stimulation enhanced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (Fig. 7b and c). Double immunofluorescence staining also confirmed that LPS stimulation significantly increased p38 MAPK phosphorylation, while this change was inhibited in p38 MAPK knockdown cells. (Fig. 7d). Although siMapk14 transfection reduced total p38 MAPK protein levels, the phosphorylation ratio remained similar between the knockdown and control groups (Fig. 7b and c). Knockdown of p38 MAPK also suppressed LPS-induced mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory mRNA expression such as Il1b, Il6, and Ccl2 (Fig. 7e). In contrast, LPS-stimulated mRNA expression of Il10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, was enhanced by p38 MAPK knockdown (Fig. 7e). These results suggest that p38 MAPK knockdown in macrophages suppresses pro-inflammatory responses, consistent with in vivo findings.

Knockdown of p38 MAPK suppressed mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines induced by lipopolysaccharide in RAW 264.7 cells. (a) The cell culture protocol for transfection siRNA targeting Mapk14 (si-Mapk14) or negative control (si-NC) into RAW 264.7 cells. (b,c) Western blot analyses of phosphorylated p38 MAPK, total p38 MAPK, and β-actin in RAW 264.7 cells with or without p38 MAPK knockdown. Original blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Fig. S5. (d) Double immunofluorescence staining for phosphorylated p38 MAPK (p-p38) and F4/80 in RAW 264.7 cells. Scale bars represent 400 μm. (e) Expression of Il1b, Il6, Ccl2, and Il10 mRNA in RAW 264.7 cells with or without p38 MAPK knockdown. Values are expressed as means ± SD. **P < 0.01.

In addition, we investigated the effect of p38 MAPK overexpression in RAW264.7 cells with using p38 MAPK expressing plasmid. We found that Mapk14 expression was significantly increased approximately fourfold in the PBS group and sixfold in the LPS group. However, overexpression of p38 MAPK did not result in any changes in Il1b and Il6 mRNA expression (Supplementary Fig. S8).

Discussion

Peritoneal fibrosis is a well-known complication in PD patients, the mechanism is diverse and not fully understood. In this study, we investigated systemic and macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice and found that both models showed amelioration of peritoneal fibrosis and inflammation. Although previous studies have highlighted the importance of p38 MAPK in peritoneal deterioration, this is the first report to demonstrate the significance of macrophages in p38 MAPK-mediated peritoneal fibrosis. p38 MAPK is a common and well-known regulator of inflammation and fibrosis, and many previous studies have reported the effectiveness of p38 MAPK inhibitor in vivo and in vitro. p38 MAPK inhibition has also been shown to be effective for renal fibrosis24 or ischemic heart injury11, leading to high expectations for the clinical use of p38 MAPK inhibitor. However, despite the ameliorative effects of p38 MAPK inhibitors in various animal disease models, clinical trials of p38 MAPK inhibitors in humans have yielded insufficient results for practical use25. Zhang et al. have reported that macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice showed improved liver fibrosis in a fatty liver model mice, whereas hepatocyte-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice exhibited worsened histological scores and increased expression of inflammatory cytokines in the liver cDNA expression array compared to control mice26. The lack of clinical application of p38 MAPK inhibitors may be due to the varying contributions of p38 MAPK depending on pathological conditions and cell types.

In our study, we showed that p38 MAPK phosphorylation was enhanced in the human peritoneum at the time of PD withdrawal and in the mouse peritoneum with CG administration. This finding is consistent with a previous report16 showing enhanced p38 phosphorylation in the peritoneal mesothelium and interstitium of CG-treated mice. It also indicates that p38 MAPK pathway is upregulated in human peritoneum after long-term PD, similar to what is observed in mice. Inducible systemic p38 MAPK knockout mice showed less peritoneal thickening, reduced pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic mRNA expression, and decreased accumulations of myofibroblasts and macrophages induced by CG administration. These results indicate that both pharmacological and genetic inhibition of p38 MAPK effectively ameliorate peritoneal fibrosis. As shown in the immunohistochemical staining of MAC-2, macrophage infiltration is a common phenotype in the progression of peritoneal fibrosis. Macrophage depletion studies have demonstrated reduction in peritoneal thickening in murine models22, there is no doubt that macrophages have a crucial role in the development of peritoneal fibrosis. However, the precise role of p38 MAPK in peritoneal macrophages remains unclear.

The examination of systemic p38 MAPK KO mice alone was considered insufficient to elucidate the role of cell-specific p38 MAPK in peritoneal fibrosis. We focused on p38 MAPK in macrophages, given the abundance of macrophages with phosphorylated p38 MAPK in the damaged peritoneum. In macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice, the number of phosphorylated p38 MAPK- and F4/80-positive cells in immunofluorescent staining was reduced compared to control mice. Macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice also showed inhibition of CG-induced peritoneal thickening and suppression of mRNA expression associated with inflammation and fibrosis. These results suggest that macrophages are the main regulators of peritoneal fibrosis via p38 MAPK pathway, and that p38 MAPK deletion in macrophages ameliorates peritoneal fibrosis and inflammation. In a previous study, Kim et al. reported that the induction of acute skin inflammation exacerbated skin thickening in macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice, whereas skin thickening and the expression of Cxcl1 and Cxcl2 were suppressed in a chronic skin inflammation model27. The CG-induced peritoneal inflammation in this study was repeated over 3 weeks, and our results are consistent with these dermatological changes to some extent. To further investigate the inflammatory changes in macrophages, we conducted in vitro studies using RAW 264.7 cells and showed that suppression of p38 MAPK reduced LPS-stimulated inflammatory mRNA changes. Although it is already known that LPS induces phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, this result suggests the effectiveness of reducing inflammation through p38 MAPK knockdown. Our in vivo study demonstrated that Tlr4 mRNA expression in the peritoneum was enhanced by CG administration and suppressed in systemic and macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice. However, p38 MAPK-knockdown RAW 264.7 cells showed no significant mRNA change of Tlr4 mRNA expression (Supplementary Fig. S4), suggesting that Tlr4 changes in vivo may be due to reduced inflammatory cell infiltration or altered expression in other cells, as indicated by the reduction of MAC-2 positive cells. The TLR-p38 MAPK pathway is known to be activated by bacterial infection or LPS stimulation28, but it may also play a critical role in peritoneal non-infectious inflammation.

This study has some limitations. Although we examined systemic and macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice, the role of p38 MAPK in other cells, such as fibroblasts and mesothelial cells, was not explored. However, since macrophage-specific p38 MAPK knockout mice showed a reduction in peritoneal thickening comparable to that seen in systemic p38 MAPK KO mice, macrophages appear to be the main actors in peritoneal fibrosis via the p38 MAPK pathway. Another limitation is that CG was used as a model of peritoneal fibrosis, but it does not perfectly mimic peritoneal fibrosis in humans, as CG causes severe inflammation.

In conclusion, this study highlights the crucial role of p38 MAPK in macrophage in peritoneal fibrosis. Further elucidation of the role of cell-specific p38 MAPK may lead to new therapeutic options to preserve peritoneal function in PD patients.

Methods

Reagents and antibodies

The primary antibodies used for immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence studies were as follows: anti-phospho-p38 MAPK antibody (#9211, Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA), anti-F4/80 antibody (MCA497GA, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), anti-MAC-2 antibody (CL8942F, Cedarlane, Ontario, Canada), and anti-α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) antibody (ab5694, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and anti-type I collagen antibody (1310-01, Southern Biotechnology Associates, Alabama, UK). The type I collagen antibodies were diluted at 1:50, while the other antibodies were used at a 1:100 dilution. pCDNA3 Flag p38 alpha was a gift from Roger Davis (Addgene plasmid # 20351; http://n2t.net/addgene:20351; RRID:Addgene_20351)29.

Human peritoneal biopsy sample

Patients admitted to Kyoto University Hospital for the diagnosis and treatment of renal disease were enrolled after obtaining informed consent. Parietal peritoneal samples were collected as biopsies approximately 1 cm from the insertion site of the PD catheter placed in the lumbar region at the beginning and the end of PD treatment, and were subsequently embedded in paraffin or OCT.

Animal experiment

C57BL/6-Gt (ROSA) 26Sortm9(Cre/ESR1)Art (ROSA26-CreERT2) mice were purchased from ARTEMIS Pharmaceuticals. Tamoxifen-inducible systemic p38α MAPK conditional knockout (Systemic p38 KO) mice were generated by crossing Mapk14 (p38α) floxed/floxed (fl/fl) mice30 with ROSA26-CreERT2 mice. Male ROSA26-CreERT2; p38αfl/fl mice or control [p38αfl/fl, Cre (-)] mice were treated with 0.2 mg/gBW (body weight) tamoxifen (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) orally for 5 days at 8–9 weeks of age. Macrophage-specific p38α KO (p38αΔMΦ) mice were generated by crossing p38αfl/fl mice with lysozyme M-Cre (LysM-Cre) mice31, obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Peritoneal fibrosis was induced in mice aged 13–15 weeks by intraperitoneal injection of 0.1% chlorhexidine gluconate (872619, Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd, Osaka, Japan) at 0.01ml/gBW, dissolved in 15% ethanol and 85% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), three times a week for 3 weeks15,32. For vehicle treatment, knockout mice or control mice were treated with intraperitoneal injection of PBS. The day after the last injection, mice were anesthetized using intraperitoneal administration of medetomidine (0.75 mg/kg), butorphanol (5 mg/kg), and midazolam (4 mg/kg), and were sacrificed under deep sedation. The peritoneum was then collected for mRNA analysis and histological examination.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Peritoneal sections (4 μm thick) were obtained from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks and stained with Masson’s trichrome and Sirius red, following protocols described in previous studies15,32. Immunohistochemical analyses for phospho-p38 MAPK, MAC-2, and αSMA were performed as follows; sections were deparaffinized, microwaved for antigen retrieval, and then incubated with each primary antibody. The number of positive cells per 0.01 mm2 was quantified for MAC-2 and αSMA. For Type I collagen immunohistochemistry, the protocol was adapted from a previous study33 with modification. Briefly, 10 μm cryostat sections fixed in paraformaldehyde were incubated in 1.5% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 15 min to block endogenous peroxide. Subsequently, sections were incubated with 10% normal donkey serum for 1 h, and then reacted with goat anti-type I collagen antibody for 1 h, followed by incubation with peroxidase donkey anti-goat IgG (AB_2313587, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 1 h.

Immunofluorescence staining

For double immunofluorescence staining of mouse phospho-p38 MAPK and F4/80, 10 μm cryostat sections fixed in paraformaldehyde were treated with 10% donkey serum for 1 hour34. The sections were subsequently incubated overnight with rabbit anti-phospho-p38 MAPK antibody and rat anti-F4/80 antibody, followed by incubation with TRITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (AB_2340588, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rat IgG (AB_2340652, Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h. The slides were then mounted using VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium with DAPI (4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Vector Laboratories, Inc. Newark, CA), and analyzed using a fluorescence microscope. (IX-81; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from the anterior abdominal wall using the FastGene RNA Basic Kit (Nippon Genetics, Tokyo, Japan), and on-column DNase digestion was performed during the protocol32. Synthesis of first strand complementary DNA from total RNA was performed using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). Gene-specific TaqMan gene expression assay probes were applied to measure the expression levels ofIl1b, Il6, Emr1, Tlr4, Col1a1, Acta2, Fn1, Ctgf, Ccl2, Il10 and Mapk14. The sequences for the primers and probes are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. Real-time quantitative PCR was conducted using the QuantStudio 3 Realtime PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA) with THUNDERBIRD qPCR Mix (TOYOBO). The expression levels of each target mRNA was expressed relative to the Gapdh mRNA level.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis using RAW264.7 cells was performed as described with some modifications35. The total cell lysates were prepared by lysing the cells in RIPA buffer supplemented Protease Inhibitor Cocktail for General Use (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). The protein extracts were then electrophoresed and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated with rabbit phosphorylated p38 MAPK and total p38 MAPK antibodies and immunoblots were then developed using horseradish peroxidase-linked donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin and a chemiluminescence kit. The obtained images were processed and analyzed using ImageJ software ver. 1.53 (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). β-actin was used as the internal control.

Cell culture and transfection

RAW 264.7 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). RAW 264.7 cells were cultured with DMEM (08457-55, Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin G (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (250 ng/ml). For p38 MAPK knockdown, cells were transfected with Mapk14 siRNA (s77113, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) by a pulse of electroporation using Nucleofector II (Lonza Group AG, Basel, Switzerland) and Ingenio® Electroporation Kit (Mirus Bio, Madison, WI). Mouse p38 MAPK expressing plasmid (Addgene plasmid #20351) was transfected using Effectene® Transfection Reagent (301425, QIAGEN, VC, USA). Transfected cells were incubated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or PBS for 2 h before being harvested for RNA analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Variables were evaluated using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance with the Tukey-Karmer post hoc test for comparison of multiple means using JMP® Pro statistical software version 14.3.0 (https://www.jmp.com). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Teixeira, J. P., Combs, S. A. & Teitelbaum, I. Peritoneal dialysis: Update on patient survival. Clin. Nephrol. 83, 1–10 (2015).

Mizuno, M. et al. Peritonitis is still an important factor for withdrawal from peritoneal dialysis therapy in the Tokai area of Japan. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 15, 727–737 (2011).

Davies, S. J., Bryan, J., Phillips, L. & Russell, G. I. Longitudinal changes in peritoneal kinetics: The effects of peritoneal dialysis and peritonitis. Nephrol. Dial Transplant. 11, 498–506 (1996).

Williams, J. D. et al. Morphologic changes in the peritoneal membrane of patients with renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 470–479 (2002).

Farhat, K., Stavenuiter, A. W., Beelen, R. H. & Ter Wee, P. M. Pharmacologic targets and peritoneal membrane remodeling. Perit. Dial Int. 34, 114–123 (2014).

Ha, H., Yu, M. R. & Lee, H. B. High glucose-induced PKC activation mediates TGF-β1 and fibronectin synthesis by peritoneal mesothelial cells. Kidney Int. 59, 463–470 (2001).

Honda, K. et al. Accumulation of advanced glycation end products in the peritoneal vasculature of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients with low ultra-filtration. Nephrol. Dial Transplant. 14, 1541–1549 (1999).

Canovas, B. & Nebreda, A. R. Diversity and versatility of p38 kinase signalling in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 346–366 (2021).

Roux, P. P. & Blenis, J. ERK and p38 MAPK-activated protein kinases: A family of protein kinases with diverse biological functions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 320–344 (2004).

Cuadrado, A. & Nebreda, A. R. Mechanisms and functions of p38 MAPK signalling. Biochem. J. 429, 403–417 (2010).

Li, M. et al. p38 MAP kinase mediates inflammatory cytokine induction in cardiomyocytes and extracellular matrix remodeling in heart. Circulation. 111, 2494–2502 (2005).

Korb, A. et al. Differential tissue expression and activation of p38 MAPK α, β, γ, and δ isoforms in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 54, 2745–2756 (2006).

Amano, H. et al. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase accelerates emphysema in mouse model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Recept. Signal. Transduct. Res. 34, 299–306 (2014).

Gupta, J. & Nebreda, A. R. Roles of p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase in mouse models of inflammatory diseases and cancer. FEBS J. 282, 1841–1857 (2015).

Ishimura, T. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-10 deficiency has protective effects against peritoneal inflammation and fibrosis via transcription factor NFkappaBeta pathway inhibition. Kidney Int. 104, 929–942 (2023).

Kokubo, S. et al. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase promotes peritoneal fibrosis by regulating fibrocytes. Perit. Dial Int. 32, 10–19 (2012).

Zarubin, T. & Han, J. Activation and signaling of the p38 MAP kinase pathway. Cell Res. 15, 11–18 (2005).

Yung, S. & Davies, M. Response of the human peritoneal mesothelial cell to injury: An in vitro model of peritoneal wound healing. Kidney Int. 54, 2160–2169 (1998).

Kiribayashi, K. et al. Angiotensin II induces fibronectin expression in human peritoneal mesothelial cells via ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK. Kidney Int. 67, 1126–1135 (2005).

Xu, Z. G. et al. High glucose activates the p38 MAPK pathway in cultured human peritoneal mesothelial cells. Kidney Int. 63, 958–968 (2003).

Ueno, T. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental peritoneal fibrosis by suppressing inflammation and inhibiting TGF-β1 signaling. Kidney Int. 84, 297–307 (2013).

Kushiyama, T. et al. Effects of liposome-encapsulated clodronate on chlorhexidine gluconate-induced peritoneal fibrosis in rats. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 26, 3143–3154 (2011).

Allen, M. et al. Deficiency of the stress kinase p38α results in embryonic lethality: Characterization of the kinase dependence of stress responses of enzyme-deficient embryonic stem cells. J. Exp. Med. 191(5), 859–870. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.191.5.859 (2000).

Koshikawa, M. et al. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in podocyte injury and proteinuria in experimental nephrotic syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 2690–2701 (2005).

Han, J., Wu, J. & Silke, J. An overview of mammalian p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases, central regulators of cell stress and receptor signaling. F1000Res. 9, 653 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Macrophage p38α promotes nutritional steatohepatitis through M1 polarization. J. Hepatol. 71, 163–174 (2019).

Kim, C. et al. p38α MAP kinase serves cell type-specific inflammatory functions in skin injury and coordinates pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1019–1027 (2008).

Horwood, N. J. et al. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is required for TLR2 and TLR4-induced TNF, but not IL-6, production. J. Immunol. 176, 3635–3641 (2006).

Enslen, H., Raingeaud, J. & Davis, R. J. Selective activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase isoforms by the MAP kinase kinases MKK3 and MKK6. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 1741–1748 (1998).

Ventura, J. J. et al. p38α MAP kinase is essential in lung stem and progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Nat. Genet. 39, 750–758 (2007).

Clausen, B. E., Burkhardt, C., Reith, W., Renkawitz, R. & Forster, I. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res. 8, 265–277 (1999).

Yokoi, H. et al. Pleiotrophin triggers inflammation and increased peritoneal permeability leading to peritoneal fibrosis. Kidney Int. 81, 160–169 (2012).

Kunoki, S. et al. Inhibition of transglutaminase 2 reduces peritoneal injury in a chlorhexidine-induced peritoneal fibrosis model. Lab. Investig. 103, 100050 (2023).

Sugioka, S. et al. Dual deletion of guanylyl cyclase-A and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in podocytes with aldosterone administration causes glomerular intra-capillary thrombi. Kidney Int. 104, 508–525 (2023).

Yokoi, H. et al. Overexpression of connective tissue growth factor in podocytes worsens diabetic nephropathy in mice. Kidney Int. 73, 446–455 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Manolis Pasparakis (University of Cologne) and Dr. Angel R. Nebreda (The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology) for providing Mapk14 floxed mice, and Dr. Kazuwa Nakao for ROSA26-CreERT2 mice. We also acknowledge K. Kawasaki, and H. Suzuki in Department of Nephrology, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University and other lab members for technical assistance, and Y. Mizukami for secretarial assistance.

Funding

This work was supported in part by research grants from JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers 23K07717 to H. Yokoi, 24K19129 to S. Sugioka, 23K15227 to H. Yamada, 22K08310 to A. Ishii, 21K16189 to S. Ohno, 23K15226 to Y. Kato), Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED Grant Numbers JP19gm1210009) to M. Yanagita, Smoking Research Foundation to H. Yokoi and A. Ishii, Japanese Association of Dialysis Physicians and Foundation, Tsuchiya Memorial Medical Foundation, and Kyoto Health Care Society to H. Yokoi, and Japanese Society of Peritoneal Dialysis to A. Ikushima.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Ikushima, T. Ishimura, K. P. Mori and H. Yokoi conceived and designed the study. A. Ikushima conducted experiments. T. Ishimura, K.P. Mori, H. Yamada, S. Sugioka, A. Ishii, N. Toda, S. Ohno, Y. Kato, and T. Handa interpreted the results and contributed to discussion. A. Ikushima, T. Ishimura and H. Yokoi wrote the manuscript. T. Ishimura drew all illustrations. H. Yokoi and M. Yanagita supervised this study. A. Ikushima and H. Yokoi are the guarantors of this work and had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

H. Yokoi has received Speakers Bureau from AstraZeneca. M. Yanagita has received research grants from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharmaceutical Corporation and Boehringer Ingelheim. All remaining authors declared no competing interests.

Ethics

The human sample study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Research of the Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University (Approval No. R3781). All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Fundamental Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiment and Related Activities in Academic Research Institutions and were approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (Approval number; MedKyo23154). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations including ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ikushima, A., Ishimura, T., Mori, K.P. et al. Deletion of p38 MAPK in macrophages ameliorates peritoneal fibrosis and inflammation in peritoneal dialysis. Sci Rep 14, 21220 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71859-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71859-5