Abstract

The study used the AirQ + software developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to evaluate the health impacts associated with long-term exposure to PM2.5 in Mashhad, Iran. For this purpose, we analyzed the daily average concentrations of PM2.5 (with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less) registered by the air quality monitoring stations from 2016 to 2021. The levels of PM2.5 surpassed the Air Quality Guidelines (AQG) limit value of 5 µg/m3 (annual value) established by WHO. The findings revealed that the burden of mortality (from all-natural causes) at people above 30 years old associated with PM2.5 exposures was 2093 [95% confidence interval [CI]: 1627–2314] deaths in 2016 and 2750 [95% CI: 2139–3038] deaths in 2021. In general, the attributable mortality from specific causes of deaths (e.g., COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases), IHD (ischemic heart diseases) and stroke) in people above 25 years old increased between the years, but the mortality from lung cancer was stable at 46 [95% CI: 33–59] deaths in 2016 and 48 [95% CI: 34–61] deaths in 2021. The attributable mortality from ALRI (Acute Lower Respiratory Infection) in children below 5 years old increased between the years. We also found differences in mortality cases from IHD and stroke among the age groups and between the years 2016 and 2021. It was concluded that burden of disease methodologies are suitable tools for regional and national policymakers, who must take decisions to prevent and to control air pollution and to analyze the cost-effectiveness of interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution presents a significant environmental challenge that must be addressed at local, regional, and global levels. Despite substantial progress, it continues to pose threats to human health and the environment1,2. Air pollution is the presence of harmful substances in the atmosphere, such as gases, particles, and biological components, which can have serious health effects3. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), nearly seven million deaths globally each year are attributed to air pollution, with the majority of people breathing air that exceeds the WHO’s guideline limits for pollutants4. Industrial facilities, motor vehicles, and household combustion devices are common sources of air pollution, emitting pollutants such as particulate matter, carbon monoxide, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide1. Particulate matter (PM) is a combination of solid and liquid particles present in the air, including “inhalable coarse particles” (PM10) and “fine inhalable particles” (PM2.5). They are composed of a variety of chemicals and can have harmful effects on human health. PM2.5, in particular, with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less, is a significant component of ambient air pollution and poses the greatest risk to health as it can penetrate deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream, leading to serious health problems5. Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter, or PM2.5, is associated with a significant burden of disease including ischemic heart disease (IHD), lung cancer (LC), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), acute lower respiratory infection (ALRI), stroke and adverse birth outcomes. This long exposure has been linked to increased morbidity and mortality, particularly in people with chronic heart or lung diseases, and reduced lung function growth in children3,6,7. According to the Global Burden of Disease studies, PM2.5 exposure contributed to 7.6% of global deaths in 2015, making it the fifth greatest risk factor for death8. WHO has established annual exposure limits for airborne particles. The annual mean values of PM2.5 concentrations is 5 µg/m3 which was set by the 2021 WHO Air Quality Guidelines9. Exposure to ambient PM2.5 has been linked to an increased incidence and mortality of several diseases10,11.

Several studies have illustrated the elevated risks for PM2.5-related deaths from stroke, IHD, COPD, and LC12,13,14,15,16. For instance, a study conducted in northern China found that long-term exposure to PM2.5 was associated with stroke mortality among urban residents17. Another study conducted in Taiwan found that elevated ambient PM2.5 levels were associated with all stroke, ischemic stroke, and hemorrhagic stroke18. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 38 studies found that long-term exposure to PM2.5 was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality19. Although multiple health impact assessments of PM2.5 have been performed in Mashhad, these studies have only considered a specific disease such as lung cancer or a short period of one year5,20,21,22,23. For the first time, the present study has examined the health impacts associated with various diseases over an extended period, analyzing the data from all monitoring stations in Mashhad city and differentiating the results by age groups.

Reducing this pollutant has been demonstrated to enhance the health of the community24. Additionally, WHO emphasizes that by reducing air pollution levels, countries can decrease the burden of disease from stroke, heart disease, lung cancer, and both chronic and acute respiratory diseases25. To guide policymakers in making informed decisions regarding air pollution mitigation, it is crucial to quantify the effects of air pollution and the potential changes due to the implementation of mitigation policies. Various techniques and tools were employed to evaluate the impact of air pollutants on human health. The AIRQ + model, developed by WHO, is capable of assessing the effects of long-term and short-term exposure to various air pollutants, including PM2.5, PM10, NO2, O3, and black carbon. This model has been applied internationally in Europe and worldwide26,27,28,29. AirQ + assesses the impact of air pollution on mortality and morbidity. The tool measures the contribution of air pollution, particularly PM2.5, to the global burden of disease, including its impact on premature mortality and various health conditions. This information is crucial for understanding the health implications of air pollution and for developing effective policies and interventions to reduce its adverse effects. The aim of present study was to assess the burden of mortality associated with the exposure to PM2.5 based on the available PM2.5 data in Mashhad city and the annual number of deaths due to natural cause and cause-specific mortality using AirQ + modelling software for the years 2016–2021.

Materials and methods

Area of study

Mashhad, based on the latest census in 2015, with a population of 3,001,184 is the second over populated city in Iran and the 95th over populated city in the world. This city with an area of 351 square kilometers, is located in the northeast of Iran at a longitude of 59° 15′ to 60° 36′ and a latitude of 35° 43′ to 37° 8′.

The height of the city is about 1050 m above sea level (maximum 1150 m and minimum 950 m) and the prevailing wind direction is from the southeast to northwest. The city of Mashhad has a variable climate, but it is moderate and tends to be cold and dry and has hot and dry summers and cold and wet winters. The annual mean temperature is 15.7 °C, with a minimum and maximum temperature of − 22 °C and 43 °C, respectively, and annual average precipitation of 230 mm. This city faces a large volume of daily pollutant production due to daily traffic of more than 800,000 cars in the city, which is responsible for 70% of the air pollution, the existence of small and large industries, and some other sources.

Data collection and calculation

Hourly or daily PM2.5 measurements were obtained from 23 air quality monitoring stations of the Environmental Protection Organization and the Mashhad Pollution Monitoring Center for the period 2016 through 2021. The data were initially filtered by removing the default and abnormal values according to the EPA method. Then, the hourly concentrations of PM2.5 from all monitoring stations were averaged to obtain daily values. All stations with fewer than 75% valid daily data were eliminated30. This criterion led to the exclusion of a number of stations, leaving 17, 12, 10, 14, 14 and 7 stations, respectively, during 2016to 2021 for all further analyses on PM2.5. Then, the annual average values of the daily 24-hour average concentrations of PM2.5 were calculated and entered in AirQ+. The city population data were obtained from the Vice Health of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Health data

The burden of disease attributable to PM2.5 was estimated by obtaining the annual number of deaths from the Vince Health of Medical Sciences University. The data set includes the annual number of deaths and cause of death per age group and sex at a regional level. The annual number of deaths were tallied for the following causes of death: all-natural-cause mortality, IHD, COPD, stroke, lung cancer diseases and ALRI. Table 1 presents the health endpoints handled by the AIRQ + and used in this study, along with their corresponding ICD-10 classification codes.

Health risk assessment of air pollution

The AirQ + model (version 2.2) developed by WHO was used to quantify the burden and health effects of exposure to air pollution in the current study. The health outcomes included long-term mortality from all natural causes (for adults above 30-years old), COPD, LC, IHD, ALRI and stroke. The software allows users to estimate the health effects of exposure to air pollution, including estimates of the reduction in life expectancy, for the most important air pollutants. Using this model, health consequences, the amount attributed to population contact and the number attributed to contact can be extracted31.

The AirQ + model is based on the attributable proportion (AP), defined as the portion of a health effect caused by air pollution in a particular population and a specific time period (Eq. 1):

where RR is a relative health consequence risk for a given health endpoint in a determined exposure to an air pollutant, whereas the value of P is also defined as the fraction of population under exposure to the air pollutant.

For long-term exposure to PM2.5, the integrated exposure-response function (IER) was utilized to assess the health impact (as shown in Eq. (2)), a method employed in Global Burden of Disease studies. The IER considers four major health endpoints including stroke, IHD, COPD, LC in adults, and acute lower respiratory infection (ALRI) in children < 5 years of age32.

where x and x0 denotes the annual mean pollutant and the cut-off or counterfactual concentrations, respectively. α, γ and δ are the parameters that are estimated based on the data collected. The cut-off value was selected based on the WHO Air Quality Guidelines as 5 µg/m3 for PM2.5.

Knowing the baseline incidence of health effect in the population under study (I) and the size of the population (Np), the amount of health effect attributable to the exposure (IE) and the number of cases attributable to the exposure (NE) are calculated using Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively:

Baseline incidence (BI)

Baseline incidence (BI) values represent the initial rate of new occurrences of a particular condition within a specified population over a set period. The baseline incidence rate is calculated as the ratio of the number of observed events to the total time the population was at risk of experiencing the event. It is a crucial measure in various fields, including public health and epidemiology, as it provides a foundation for assessing changes in disease occurrence and evaluating the impact of interventions33,34. The baseline incidence (BI) values for all-cause, non-accidental deaths per 100,000 populations were calculated using data obtained from Vice Health of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Results and discussion

Temporal variations of PM2.5 concentrations

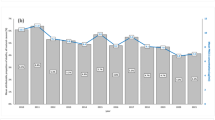

Figure 1 shows the annual average values of the daily 24 h average concentrations of PM2.5 over the study periods. The annual mean values of PM2.5 concentrations were above the recommended annual limit value of 5 µg/m3 which was set by the 2021 WHO Air Quality Guidelines9.

The study results showed that there are concentration fluctuations, so that in 2017 the concentration increased slightly, but in 2018 it suddenly decreased, in 2019 it increased again, in 2020 it decreased slightly and finally increased in 2021. Over the period 2016–2021, the highest and lowest annual average PM2.5 concentrations were recorded in 2021 and 2018 with the value 35.13 µg/m3 and 26.79 µg/m3, respectively. But in general, a sinusoidal trend for changes in the annual concentration of PM2.5 particles has been recorded during the study period. The results of our study are consistent with those of Hou et al. They showed that in a 5-year period, the concentration of PM2.5 particles have increased, and the lowest and highest concentration were in 2012 and 2017, respectively35. On the other hand, Rovira et al. reported the average annual concentration of PM2.5 particles in their study at 68.98 µg/m32, and Ezaz’s research found that the annual average concentration of PM2.5 in South Korea was 54.15 µg/m336.

Mortality attributed to the exposure to PM2.5

The burden of mortality due to the exposure to PM2.5 were estimated by the AirQ + software considering the default RR values for the all-cause natural mortality cases and the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2020 (integrated function 2019) for LC, ALRI, COPD, IHD and stroke. As for the GBD 2020 function, the cut-off value is defined at 2.4 µg/m3. In GBD study, a theoretical minimum risk exposure level, known as the counterfactual level, is defined as the distribution of risk that minimizes the risk for each individual in the population. For the exposure to PM2.5 concentrations, a uniform distribution between 2.4 and 5.9 µg/m3 was considered37. The total population and the population at risk in Mashhad was based on the demographic data for the estimated population for the years 2016–2021.

Tables 2, 3 and 4 displays the estimated health endpoints associated with the long-term exposure (annual exposure) to PM2.5 in Mashhad over the years 2016–2021. The annual-average concentration of PM2.5 for the Mashhad for each year was estimated by joining the annual mean PM2.5 concentrations recorded by the available air quality monitoring stations (Fig. 1). In particular, the annual-average concentrations of PM2.5 for 2016 was 33.88 µg/m3 and 35.13 µg/m3 for 2021.

As we can see in Table 2, the mortality burden from all natural causes for the population above 30 years old attributed to PM2.5 exposures is 2093 [1627–2314] deaths in 2016 and 2750 [2139–3038] deaths in 2021. The attributable cases per 100,000 populations at risk is 134.93 [104.86-149.17] deaths in 2016 and 143.19 [111.40-158.21] deaths in 2021. The attributable mortality burden increased in 2021 compared with 2016 as the mean annual PM2.5 concentrations in Mashhad increased from 33.88 to 35.13 µg/m3 in 2021. Goodarzi et al. reported that 39.18% of deaths in Ahvaz city were attributed to natural causes38. Hadei et al. also reported a total of 4,336 natural deaths across ten cities in Iran39. Moreover, Rovira et al. utilized the AirQ + software in Catalonia, Spain, over a 13-year period from 2005 to 2016. They found that the number of excess deaths from all natural causes due to exposure to PM2.5 ranged from 297 excess deaths in 2005 to 23 excess deaths in 20162.

As for the specific causes of death, the total COPD annual deaths increased over the years, ranging from 11 deaths in 2016 to 13 deaths in 2021. These trends are associated with various factors, including the economic crisis, socioeconomic status, smoking habits, and indoor and outdoor air pollution40. Since the annual mean PM2.5 concentrations increased over the study years, the estimated number of COPD attributable cases to PM2.5 exposures (at the total population) are 49 [36–61] deaths in 2016 and 68 [50–85] deaths in 2021. For the population at risk (people above 25 years old), the attributable cases are 2.47 [1.81–3.11] deaths in 2016 and 3.10 [2.27–3.88] in 2021. Kermani et al. were recorded 124 cases in Karaj during their study period (2012–2016) due to exposure to PM2.5 particles41. On the other hand, Ansari et al. reported 172 people in his study at 2017–201842. Huang et al. demonstrated that exposure to PM2.5 in Taiwan at levels exceeding 38.98 µg/m3 increases sensitivity to COPD43.

In addition, the total number of deaths from lung cancer decreased over the years, with a baseline incidence in mortality rates from lung cancer (for people above 25 years old) ranging from 11 deaths in 2016 to 10 deaths in 2021. The attributed cases of lung cancer to PM2.5 exposures (at the total population) are 4633,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59 deaths in 2016 and 48 [34–61] deaths in 2021, whereas at the population at risk the cases are 2.34 [1.68–2.97] deaths in 2016 and 2.18 [1.57–2.76] deaths in 2021. The link between air pollution and lung cancer is well-established, with studies conducted in Mashhad demonstrating strong associations among air pollution, smoking, and the incidence of lung cancer44. Hadei et al. (2016) found that during a period of three years, the total number of deaths caused by lung cancer due to exposure to PM2.5 in ten cities was estimated to be 864 cases20. Multiple studies, including those by Mohammadi, Zhang, Zhai, and Yang et al., have investigated the substantial link between air pollution and lung cancer45,46,47,48.

The estimated number of attributable cases for mortality due to ALRI in children aged 0–5 years was 21,2,3 deaths in 2016 and 74,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 deaths in 2021, whereas at the population at risk the cases are 0.49 [0.29–0.73] deaths in 2016 and 2.17 [1.28–3.18] deaths in 2021. Overall, research indicates that among the five causes of death attributed to PM2.5 particles, deaths from ALRI represent a small percentage. This is primarily due to the lower population at risk (children under 5 years). In our study, 20 deaths due to ALRI occurred during the period 2016–2021 in Mashhad. In their study, Ansari et al. reported this value to be 27 items for Tehran, Faridi et al., reported this value to be 13 cases and Kermani et al. reported this value to be 21 for Karaj41,42,49. Dang revealed that the risk of ALRI in children increased by approximately 3.51 times for every increase 10 µg/m3 in PM2.5 particle concentration50.

As we can see from Table 3, the IHD attributable cases to PM2.5 exposures are 244 [144–290] deaths in 2016 and 445 [295–592] deaths in 2021 in the total population. As for the IHD attributable cases at the population at risk, 592.39 [382.42-803.96] deaths are attributed to PM2.5 exposures in 2016 and 997.79 [654.59–1343.30] deaths are attributed to PM2.5 exposures in 2021. The attributable mortality burden at the total population increased almost two-fold in 2021 compared with 2016 as the mean annual PM2.5 concentrations in Mashhad increased from 33.88 to 35.13 µg/m3 in 2021. There is also substantial increase in death rates in people above 85 years’ old. In addition, the total number of deaths from IHD increased over the years, with a baseline incidence in mortality rates from IHD (for people above 25 years old) ranging from 3482 deaths in 2016 to 5514 deaths in 2021. Lelieveld et al., Warburton et al., and Soleimaniet al. have reported a positive and significant association between the occurrence of IHD and exposure to air pollution51,52,53. Liu et al. also reported that deaths from IHD in China increased from 800,000 in 2004 to nearly 1 million in 2012, indicating that despite advancements in science, unhealthy air continues to claim many lives54. According to the WHO’s 2018 report, 52% of the total deaths attributed to air pollution and fine particles in Iran are related to IHD55.

Regarding the mortality from stroke associated with the long-term exposure to PM2.5 (Table 4), the analysis revealed a considerable increment in deaths ranging from 150 [111–192] deaths in 2016 to 239 [179–299] deaths in 2021. For the population at risk, the mortality cases are 436.77 [327.27–553.74] deaths in 2016 and 531.31 [397.57–669.27] deaths in 2021 that are attributed to PM2.5 exposures. Specifically, the total mortality from stroke (in population above 25 years old) in Mashhad was 2195 deaths in 2016 and 2561 deaths in 2021. Amoatey et al. (2020) conducted a study to estimate the number of excess deaths caused by long-term exposure to PM2.5 in Rome, Italy during the year 2014. Their analysis revealed that the corresponding number of deaths for stroke was 13.9 (4.5–23.9) deaths per 100,000 inhabitants56. A study also conducted in Bengaluru, India, utilized the AirQ + software to assess the health impacts of long-term PM2.5 exposures. The study found that PM2.5 exposures was associated with 3393 deaths from IHD and 1016 deaths from stroke, indicating age differences in mortality rates. Additionally, long-term PM2.5 exposures was found to be responsible for 3413 deaths from COPD57.

Numerous global studies have utilized the AirQ + software to investigate the mortality and morbidity associated with exposure to air pollutants56. Various studies also have been carried out in Iran in order to predict health burden attributable to ambient air pollutants using AirQ+5,20,21,22,24,41,58,59. One of the limitations of the study was that it coincided with a nationwide novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown, during which reduced anthropogenic activities and, consequently, lowered pollution levels were observed. In contrast, this study utilized regional-level and age-specific baseline mortality data, which is a strength as it accounts for variations in mortality rates across regions within the same country, from year to year, and among different age groups.

Conclusion

In this study, an analysis of the impact of PM2.5 on specific causes of mortality in Mashhad metropolis was performed. The assessment of the burden of mortality from long-term exposure to PM2.5 was based on annual average concentrations. This analysis was conducted using the AIRQ + software, which is a tool known for its suitability in quantifying the deterministic effects of air pollution on human health. The statistical analysis shows that the annual average concentrations of PM2.5 levels for the period 2016–2021 constantly exceeded the AQG limit values established by the WHO in 2021 in order to protect human health. Therefore, the health impact assessment revealed a substantial burden of mortality cases attributed to long-term exposure to PM2.5. With respect to the results of this study, the burden of mortality (from all-natural causes) associated with PM2.5 exposures was 2093 [1627–2314] deaths in 2016 and 2750 [2139–3038] deaths in 2021. The findings of this study can be utilized by policymakers to enhance public health through environmental health management. It is widely recognized that effective air quality management plays a crucial role in shaping a country’s environmental policy, particularly in the current era of global environmental crisis. To enhance environmental policies and government structures for addressing air pollution, it is crucial to incorporate air pollution health impact assessment within these frameworks. This can prevent air pollution and decline or even minimize the burden of related diseases.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

EPA. Air Pollution: Current and Future Challenges (2016).

Rovira, J., Domingo, J. L. & Schuhmacher, M. Air quality, health impacts and burden of disease due to air pollution (PM10, PM2.5, NO2 and O3): Application of AirQ + model to the Camp De Tarragona County (Catalonia, Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 703, 135538 (2020).

Manisalidis, I., Stavropoulou, E., Stavropoulos, A. & Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and health impacts of air pollution: A review. Front. Public. Health 8, 14 (2020).

Abbas, T. & Abbas, R. (eds) Assessing health impact of air pollutants in five iraqi cities using AirQ + model. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (IOP Publishing, 2021).

Bonyadi, Z., Ehrampoush, M. & Ghaneian, M. T. Health impact assessment of the ambient PM2.5 concentration in Mashhad, Iran, in 2013. J. Rafsanjan Univ. Med. Sci. 15(5), 389–398 (2016).

Wang, F. et al. Policy-driven changes in the health risk of PM2.5 and O3 exposure in China during 2013–2018. Sci. Total Environ. 757, 143775 (2021).

Ghorani-Azam, A., Riahi-Zanjani, B. & Balali-Mood, M. Effects of air pollution on human health and practical measures for prevention in Iran. J. Res. Med. Sci. 21 (2016).

Jones, J. S. et al. Long-term exposure to low-concentration PM2.5 and heart disease in older men in Perth, Australia: The Health in men Study. Environ. Epidemiol. 7(4), e255 (2023).

Organization, W. H. WHO Global air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide (World Health Organization, 2021).

Neira, M., Prüss-Ustün, A. & Mudu, P. Reduce air pollution to beat NCDs: From recognition to action. Lancet 392(10154), 1178–1179 (2018).

Thangavel, P., Park, D. & Lee, Y-C. Recent insights into particulate matter (PM2.5)-mediated toxicity in humans: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(12), 7511 (2022).

Yin, P. et al. Long-term fine particulate matter exposure and nonaccidental and cause-specific mortality in a large national cohort of Chinese men. Environ. Health Perspect. 125(11), 117002 (2017).

Chen, J. & Hoek, G. Long-term exposure to PM and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 143, 105974 (2020).

Bowe, B., Xie, Y., Yan, Y. & Al-Aly, Z. Burden of cause-Specific Mortality Associated with PM 2.5 Air Pollution in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open. 2(11), e1915834 (2019).

Thurston, G. D. et al. Ischemic heart disease mortality and long-term exposure to source-related components of US fine particle air pollution. Environ. Health Perspect. 124(6), 785–794 (2016).

Hystad, P. et al. Associations of outdoor fine particulate air pollution and cardiovascular disease in 157 436 individuals from 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet Planet. Health 4(6), e235–e45 (2020).

Yang, X. et al. Long-term exposure to ambient PM2.5 and stroke mortality among urban residents in northern China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 213, 112063 (2021).

Chen, P-C. et al. A cohort study evaluating the risk of stroke associated with long-term exposure to ambient fine particulate matter in Taiwan. Environ. Health 21(1), 43 (2022).

Guo, J. et al. Long-term exposure to particulate matter on cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public. Health 11, 1134341 (2023).

Hadei, M. et al. Estimation of gender-specific lung cancer deaths due to exposure to PM2.5 in 10 cities of Iran during 2013–2016: A modeling approach. Int. J. Cancer Manag. 10(8) (2017).

Hopke, P. K. et al. Spatial and temporal trends of short-term health impacts of PM2.5 in Iranian cities; a modelling approach (2013–2016). Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 18(2), 497–504 (2018).

Miri, M. et al. Mortality and morbidity due to exposure to outdoor air pollution in Mashhad metropolis, Iran. The AirQ model approach. Environ. Res. 151, 451–457 (2016).

Nourbakhsh, S. & Pazira, M. Using AirQ + Software to Predict Mortality Attributed to PM2.5 in the Air of Mashhad in 2019 (2022).

Noferesti, A. R., Atabi, F., Nouri, J., MiriLavasani, M. R. & Jozi, S. A. Predicting the mortality rate due to particulate matters using AirQ software and health risk assessment in the city of Sanandaj. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21(2), 211–226 (2019).

WHO. Ambient (outdoor) air pollution 2022.

Li, Y., Henze, D., Jack, D. & Kinney, P. The influence of air quality model resolution on health impact assessment for fine particulate matter and its components. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 9, 51–68 (2016).

Hunt, S. W., Winner, D. A., Wesson, K. & Kelly, J. T. Furthering a partnership: Air quality modeling and improving public health. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 71(6), 682–688 (2021).

Arregocés, H. A., Rojano, R. & Restrepo, G. Health risk assessment for particulate matter: Application of AirQ + model in the northern Caribbean region of Colombia. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 1–16 (2023).

Europe WROf. AirQ+: Software Tool for Health Risk Assessment of Air Pollution (WHO Regional Office for Europe Bonn, Germany, 2019).

UNION, P. Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe. Offi. J. Eur. Union (2008).

Amini, H. et al. Two decades of Air Pollution Health Risk Assessment: Insights from the Use of WHO’s AirQ and AirQ + tools. Public Health Rev. 45, 1606969 (2024).

Chung, C. Y., Yang, J., Yang, X. & He, J. Mathematical modeling in the health risk assessment of air pollution-related disease burden in China: A review. Front. Public Health 10, 1060153 (2022).

Khreis, H., Alotaibi, R., Horney, J. & McConnell, R. The impact of baseline incidence rates on burden of disease assessment of air pollution and onset childhood asthma: Analysis of data from the contiguous United States. Ann. Epidemiol. 53, 76–88.e10 (2021).

Ostropolets, A. et al. Factors influencing background incidence rate calculation: Systematic empirical evaluation across an international network of observational databases. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 814198 (2022).

Hou, X., Fei, D., Kang, H., Zhang, Y. & Gao, J. Seasonal statistical analysis of the impact of meteorological factors on fine particle pollution in China in 2013–2017. Nat. Hazards 93(2), 677–698 (2018).

Ahmed, E., Kim, K-H., Shon, Z-H. & Song, S-K. Long-term trend of airborne particulate matter in Seoul, Korea from 2004 to 2013. Atmos. Environ. 101, 125–133 (2015).

Rentschler, J. & Leonova, N. Global air pollution exposure and poverty. Nat. Commun. 14(1), 4432 (2023).

Karimi, A. et al. Concentrations and health effects of short-and long-term exposure to PM2.5, NO2, and O3 in ambient air of Ahvaz city, Iran (2014–2017). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 180, 542–548 (2019).

Hadei, M. et al. Distribution and number of ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke deaths due to chronic exposure to PM2.5 in 10 cities of Iran (2013–2015); an AirQ + modelling. J. Air Pollut. Health 2(3), 129–136 (2017).

Begou, P. & Kassomenos, P. Burden of natural-cause and cause-specific mortality associated with long-term exposure to PM2.5: A case study in Attica Region, Greece. Atmosphere 13(12), 2026 (2022).

Kermani, M. et al. Health impacts and burden of disease attributed to long-term exposure to atmospheric PM10/PM2.5 in Karaj, Iran: Effect of meteorological factors. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 102(18), 6134–6150 (2022).

Ansari, M. & Ehrampoush, M. H. Meteorological correlates and AirQ + health risk assessment of ambient fine particulate matter in Tehran, Iran. Environ. Res. 170, 141–150 (2019).

Huang, H-C. et al. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and PM2.5 in Taiwanese nonsmokers. Int. J. Hyg. Environ Health 222(5), 884–888 (2019).

Salehi, M. et al. Epidemiology of lung cancer in northeast of Iran: A 25-year study of 939 patients. Med. J. Islamic Repub. Iran 34, 17 (2020).

Mohammadi, A., Faraji, M., Conti, G. O., Ferrante, M. & Miri, M. Mortality and morbidity due to exposure to particulate matter related to drying Urmia Lake in the NW Iran. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 60, e14–e5 (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. Association of breastfeeding and air pollution exposure with lung function in Chinese children. JAMA Netw. Open 2(5), e194186–e (2019).

Zhai, T., Li, S., Hu, W., Li, D. & Leng, S. Potential micronutrients and phytochemicals against the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer. Nutrients 10(7), 813 (2018).

Yang, B-Y. et al. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollution (including PM1) and metabolic syndrome: The 33 communities Chinese Health Study (33CCHS). Environ. Res. 164, 204–211 (2018).

Faridi, S. et al. Long-term trends and health impact of PM2.5 and O3 in Tehran, Iran, 2006–2015. Environ. Int. 114, 37–49 (2018).

Luong, L. T. M. et al. Particulate air pollution in Ho Chi Minh city and risk of hospital admission for acute lower respiratory infection (ALRI) among young children. Environ. Pollut. 257, 113424 (2020).

Lelieveld, J. et al. Cardiovascular disease burden from ambient air pollution in Europe reassessed using novel hazard ratio functions. Eur. Heart J. 40(20), 1590–1596 (2019).

Warburton, D. E. et al. A systematic review of the short-term health effects of air pollution in persons living with coronary heart disease. J. Clin. Med. 8(2), 274 (2019).

Soleimani, Z., Darvishi Boloorani, A., Khalifeh, R., Griffin, D. W. & Mesdaghinia, A. Short-term effects of ambient air pollution and cardiovascular events in Shiraz, Iran, 2009 to 2015. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 6359–6367 (2019).

Liu, T. et al. Attributions of meteorological and emission factors to the 2015 winter severe haze pollution episodes in China’s Jing-Jin-Ji area. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17(4), 2971–2980 (2017).

Maracy, M. R. et al. Burden of ischemic heart diseases in Iran, 1990–2010: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study 2010. J. Res. Med. Sci. 20(11), 1077–1083 (2015).

Amoatey, P., Sicard, P., De Marco, A. & Khaniabadi, Y. O. Long-term exposure to ambient PM2.5 and impacts on health in Rome, Italy. Clin. Epidemiol. Global Health 8(2), 531–535 (2020).

Prabhu, V., Singh, P., Kulkarni, P. & Sreekanth, V. Characteristics and health risk assessment of fine particulate matter and surface ozone: Results from Bengaluru, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 194(3), 211 (2022).

Amini, H. et al. Short-term associations between daily mortality and ambient particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and the air quality index in a Middle Eastern megacity. Environ. Pollut. 254, 113121 (2019).

Hadei, M. et al. Estimation of mortality and hospital admissions attributed to criteria air pollutants in Tehran Metropolis, Iran (2013–2016). Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 17(10), 2474–2481 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Grant No: 4002187 of the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences of Islamic Republic of Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. and A.N. wrote the main manuscript text, E.MF. analyzed the data and N.N. and BF.N. Acquired the data. BF.N. revised the manuscricpt. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naimi, N., Sarkhosh, M., Nabavi, B.F. et al. Estimating the burden of diseases attributed to PM2.5 using the AirQ + software in Mashhad during 2016–2021. Sci Rep 14, 24462 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74328-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74328-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Long-term trends, health impacts, and economic costs of PM₂.₅ in Khorramabad, Iran (2014–2023)

BMC Public Health (2026)

-

Modeling the effects of air pollution and meteorological variables on mortality from respiratory diseases: insights from the ARDL

Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics (2025)