Abstract

Hepatocytes-like cells (HLC) derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells show great promise for cell-based liver therapies and disease modelling. However, their application is currently hindered by the low production yields of existing protocols. We aim to develop a bioprocess able to generate high numbers of HLC. We used stirred-tank bioreactors with a rational control of dissolved oxygen concentration (DO) for the optimization of HLC production as 3D aggregates. We evaluated the impact of controlling DO at physiological levels (4%O2) during hepatic progenitors’ stage on cell proliferation and differentiation efficiency. Whole transcriptome analysis and biochemical assays were performed to provide a detailed characterization of HLC quality attributes. When DO was controlled at 4%O2 during the hepatic progenitors’ stage, cells presented an upregulation of genes associated with hypoxia-inducible factor pathway and a downregulation of oxidative stress genes. This condition promoted higher HLC production (maximum cell concentration: 2 × 106 cell/mL) and improved differentiation efficiencies (80% Albumin-positive cells) when compared to the bioreactor operated under atmospheric oxygen levels (21%O2, 0.6 × 106 cell/mL, 43% Albumin positive cells). These HLC exhibited functional characteristics of hepatocytes: capacity to metabolize drugs, ability to synthesize hepatic metabolites, and inducible cytochrome P450 activity. Bioprocess robustness was confirmed with HLC derived from different donors, including a primary hyperoxaluria type 1 (PH1) patient. The generated PH1.HLC showed metabolic features of PH1 disease with higher secretion of oxalate compared with HLC generated from healthy individuals. This work reports a reproducible bioprocess, that shows the importance of controlling DO at physiological levels to increase HLC production, and the HLC capability to display PH1 disease features.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liver diseases namely, decompensated cirrhosis, viral hepatitis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, cause over 2 million deaths each year worldwide and are linked to high morbidity, deteriorating health, and substantial economic expenditures1. Although liver transplantation is one of the few options for these patients, the shortage of organ donors and the requirement for lifelong immunosuppression have limited its use2. As a result, hepatocyte transplantation and bioartificial liver (BAL) devices containing active hepatocytes that sustain hepatic function have been used to bridge patients to native regeneration or organ transplantation3,4. These therapeutic modalities, however, are limited by the lack of human livers as a source of primary human hepatocytes (PHH) and by the limitations of xenogeneic sources. Additionally, practical limitations of PHH-based therapies include the significant donor-to-donor variability and difficulty in retaining their viability and phenotype in culture and upon recovery from cryopreservation5.

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC) hold great promise in regenerative medicine due to their pluripotent potential, high proliferative and self-renewal capacity, and do not raise ethical controversy. hiPSC can be generated by reprogramming somatic cells back into a pluripotent state and have demonstrated three-germ layer differentiation potential, i.e. the ability to differentiate into a wide variety of cell types, including hepatocyte-like cells (HLC)6. Therefore, these HLC represent a promising and potentially inexhaustible alternative source of hepatocytes that can be used not only in cell therapy and bioengineered livers for the treatment of hepatic diseases7,8, but also in the development of advanced in vitro cell models (e.g. organoids) for pharmaceutical testing and for disease modelling applications9,10. Some examples of disease models developed with HLC include familial hypercholesterolemia11, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease12, and also rare diseases such as Primary Hyperoxaluria Type 1 (PH1)13.

PH1 is a rare metabolic disorder of the liver, resulting from a deficiency or absence of the liver-specific enzyme alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGT) involved in glyoxylate metabolism. This deficiency leads to an increased conversion of glyoxylate to oxalate, causing excessive oxalate synthesis by the liver14. The subsequent accumulation of calcium oxalate crystals in the kidney can lead to severe kidney complications, including end-stage renal disease. In recent years, advancements in hiPSC technology have augmented the potential of HLC as a cell-model. These models are instrumental in elucidating the pathophysiology of diseases and accelerating drug development efforts15. Moreover, it serves as a foundation for the conceptualization of innovative cell and gene-based therapies13. However, the rarity of the disease, limits the available patient population for study, constraining the development of patient-specific disease models.

Indeed, the translational potential of HLC has not yet been fully demonstrated due to the large cell numbers of high quality HLC required, and the lack of efficient bioprocesses for their manufacturing. Current protocols for hiPSC hepatic differentiation intend to recapitulate the in vivo liver organogenesis to generate populations successively enriched for definitive endoderm, early hepatic progenitors, hepatoblasts, and, finally, HLC16,17. Although typical differentiation protocols were optimized for classical small-scale culture systems (multi-well plates, T-flasks) and, more recently, transferred to different types of bioreactor systems, namely rotary cell culture system18, stirred-tank bioreactor (STB)19 and 3D perfused bioreactors20. these are still limited by low cell numbers and cellular heterogeneity. Considering that the cell numbers required for clinical applications exceed 1 × 109 cells21, this implies that significant process development and intensification is required.

This work aimed to develop a bioprocess to improve the generation of HLC in stirred-tank bioreactors through modulation of DO level during the differentiation process. Although it is well established in the literature that during liver development, physiological oxygen concentration in the tissue ranges from 30 to 65 mmHg (corresponding to 4–9%O2)22, the impact of these low-O2 levels during in vitro hepatogenesis is still unclear and the results obtained are still inconclusive. Indeed, it has been shown that DO regulation at 6%O2 (corresponding to 45 mmHg) during differentiation improved gene expression of liver specific markers and key liver metabolic functions, with higher inducible cytochrome P450 activity22,23, while other studies reported that a prolonged low oxygen concentration (5%O2), impaired hepatic maturation24.

In this study, we show the importance of controlling the DO at physiologic levels during specific stages of the hepatic differentiation process to maximize cell numbers, improve homogeneity of cell culture and the quality of generated HLC. The optimized bioprocess was validated with hiPSC derived from a healthy donor as well as from a PH1 patient where generated HLC successfully mimics the PH1 disease phenotype, offering hope for better understanding, treating, and potentially curing rare liver diseases.

Results

4%O2 during hepatic specification improves HLC production and hepatic differentiation efficiency

hiPSC were expanded as 3D cell aggregates in STB for 4 days (from day − 4 to day 0), and then, differentiated into HLC over additional 21 days of culture (Fig. 1a). To evaluate the impact of dissolved oxygen concentration on HLC production, hepatocyte differentiation efficiency (i.e. % of cells obtained at the end positive for hepatocyte markers) and quality attributes, we cultured the cells under physiological levels of dissolved oxygen (4% O2) during hepatocyte progenitor stage, i.e. from day 4 to day 14 of differentiation (STB_4%O2, Fig. 1a) and compared the outcome with cells that were differentiated in bioreactors operated under atmospheric levels of oxygen. Online monitoring of DO confirm a constant DO level at 4% in STB_4%O2 between day 4 and day 14 (Fig. 1b) whereas in the STB_21%O2, DO levels were up to 4-times higher, showing a decrease from 16%O2 at day 4 to 11%O2 at day 14 (Fig. 1c).

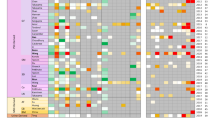

The differences in the concentration of DO from day 4 to day 14 in both STB conditions impacted the transcriptome profile of HLC at day 14. We observed a higher (3.3-fold) expression of the carbonic anhydrase 9 (CA9) (Fig. S1), a known marker to be induced in a low oxygen environment25, and an upregulation of genes associated with hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) pathway (e.g. PDK1, PFKBF3, HK2, SLC2A1, HK1, EPO, LDHA)26 in STB_4%O2 when compared to STB_21%O2, (Fig. 1d), confirming that cells were experiencing hypoxic conditions when DO was controlled at 4%O2.

Hepatic differentiation of hiPSC in stirred-tank bioreactors operated under 4%O2 (STB_4%O2) or atmospheric levels of oxygen (STB_21%O2). (a) Schematic diagram of the integrated bioprocess for hiPSC expansion and hepatic differentiation as 3D cell aggregates. (b, c) Online monitoring trend lines of DO (%O2) for STB_4%O2 (b) and STB_21%O2 (c) conditions. The peaks in the trend lines observed in both profiles are a consequence of the aeration promoted by the complete medium exchange procedures performed during the process at specific timepoints (day 0, day 1, day 2, day 3, day 4, day 9, and day 14). (d, e) Heatmaps representing the z-score of vst-normalized counts for expressed genes at day 14 of oxidative stress response (WP408) (d) and Hypoxia-inducible factor pathway (hsa:04066) (e). Data shown represents three pooled independent biological experiments (two independent experiments for PH1 cell line: Run1 STB_4%O2, Run1 STB_21%O2 and Run2 STB_4%O2, Run2 STB_21%O2 and one independent experiment for ChiPSC18 cell line: Run3 STB_4%O2, Run3 STB_21%O2).

In STB_4%O2, we also observed a downregulation of genes associated with oxidative stress response (e.g. NFKB1, NFE2L2, JUNB, SOD, GPX3)27 when compared to STB_21%O2 (Fig. 1e). Oxidative stress refers to elevated intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) concentration in culture and is shown to impair cell proliferation and increase cell apoptosis and necrosis28. In agreement with that, our data demonstrated that negligible cell proliferation was attained when the bioreactor was operated under standard atmospheric levels of oxygen, contrasting with STB_4%O2 where a 5-fold increase in cell concentration was achieved between day 4 and 14 (Fig. 2a), generating at the end of the differentiation period 2 × 106 cell/mL (corresponding to total of 400 million cells per STB run). The improved cell proliferation attained in STB_4%O2 when compared to STB_21%O2 did not impact on the profile of aggregate concentration (Fig. 2b) but rather on the size of the cell aggregates (Fig. 2c); i.e. higher average aggregate size was observed in STB_4%O2 from day 4 onwards when compared to cells cultured in STB_21%O2(Fig. 2c). Despite of the increased mean aggregate size observed (177 μm vs. 134 μm, 246 μm vs. 172 μm, 280 μm vs. 198 μm at days 9, 14 and 21, respectively for STB_4%O2 vs. STB_21%O2, Fig. 2c), cells in both conditions remained highly viable, as shown by FDA/ TO-PROTM-3 Iodide staining (Fig. 2d).

Hypoxia stimulus in hepatic differentiation improves cell proliferation in bioreactors. (a-b) Profiles of cell (a) and aggregate (b) concentration in bioreactors operated under physiological (STB_4%O2, blue lines) and atmospheric (STB_21%O2, grey lines) levels of oxygen. (c) Average aggregate diameter estimated at days 9, 14, 21 (more than 200 aggregates per condition were analysed). (d) Fluorescence images of cell aggregates at days 4, 9, 14, 21, stained with fluorescein diacetate (FDA, live cells, green) and TO-PROTM-3 Iodide (dead cells, red); Scale bar: 200 μm. The data shown represents three pooled independent biological experiments (two independent experiments for PH1.hiPSC cell line and one independent experiment for ChiPSC18 cell line).

Controlling the dissolved oxygen concentration at 4%O2 between day 4 and 14 of the differentiation improved not only cell proliferation but also cell commitment towards HLC. While no differences were observed in the RNA-seq whole transcriptomic data between both groups (Fig. S2), quantitative gene expression of key hepatic specific markers HNF4a, AFP, ALB, A1AT, CYP3A4 analysed by RT-qPCR on day 21 showed a significant higher expression in STB_4%O2 than in STB_21%O2 (Fig. 3a). The expression of immature and mature hepatic specific markers (AFP and ALB, respectively) in HLC aggregates of both bioreactor conditions was detected at the protein level by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3b). Importantly, flow cytometry analysis revealed a higher hepatocyte differentiation efficiency in STB_4%O2 with more than 80% of cells positive for the mature hepatic marker (ALB) and a small population positive for the immature hepatic marker (AFP, 28%), whereas in the STB_21%O2, the opposite was observed (43% of ALB+ cells and 65% of AFP+ cells) (Fig. 3c).

Functional analysis reveals hepatic features across different hiPSC lines

We then validated the optimized hepatocyte differentiation bioprocess, i.e. STB_4%O2, using hiPSC lines with different genetic backgrounds. In particular, we performed three independent bioreactor runs with hiPSC derived from a PH1 patient (PH1.hiPSC line) and two independent bioreactor runs with a hiPSC line derived from a healthy individual (ChiPSC18). Similar hepatic gene expression levels between both hiPSC lines along differentiation were obtained (Fig. S3). The specific metabolic rates of glucose (GLC) and glutamine (GLN) consumption and lactate (LAC) and ammonia (NH3) production estimated show no differences between both hiPSC lines (Fig. S4). No depletion of glucose and glutamine nor accumulation of lactate or ammonia at toxic concentrations were detected (data not shown).

STB_4%O2 condition shows superior hepatic differentiation. (a) Relative gene expression of hepatic specific markers (HNF4a, AFP, ALB, A1AT, CYP3A4) in bioreactors operated under physiological (STB_4%O2, blue) and atmospheric (STB_21%O2, grey) levels of oxygen. (b) Immunofluorescence staining of HLC whole aggregates for ALB (red) and AFP (green) hepatic markers in both culture conditions. Scale bar: 100 μm. (c) Flow cytometry analysis of hepatocyte markers ALB and AFP, performed at the last day of differentiation (day 21) in STB_4%O2 (blue) and in STB_21%O2 (grey), PHH, primary human hepatocytes; ALB, Albumin; AFP, Alpha-fetoprotein. Data mean ± SEM. p ≤ 0.05(*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.0001 (****). nSTB_4%O2 =3, nSTB_21%O2 =3.

Both PH1.HLC and ChiPSC18.HLC showed drug metabolization capacity, as they were able to uptake indocyanine green (ICG) compound after 1 h incubation and release it (Fig. 4a).

HLC after 21 days of differentiation using the optimized process (STB_4%O2) show functional characteristics of hepatocytes across PH1.HLC and a ChiPSC18.HLC lines. (a) Representative images of HLC across both cell lines after uptake (1 h) of indocyanine green (ICG). (b) Profile of ICG release of PH1.HLC (blue) and ChiPSC18.HLC (green) cell lines. (c, d, e, f, g) Albumin, A1AT, AFP, Urea and Total Bile acids, production by PH1.HLC (blue), ChiPSC18.HLC (green), and Primary human hepatocytes (PHH, grey) were analysed in a culture medium. (h) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of PH1/ChiPSC18.HLC sections, HLC glycogen storage by periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining, and collagen deposition by Masson Trichome (MT) staining. Scale bars: 250 μm (left panel) and 50 μm (right panel). (i) CYP3A4 enzyme activity response to rifampicin and to DMSO. Data shown represents mean ± SEM. p ≤ 0.0001 (****). nPH1.HLC=3, nChiPSC18.HLC=2.

The pattern of ICG release in HLC showed a rapid release, reaching a plateau level in 2 h after the incubation period (Fig. 4b). PH1.HLC and ChiPSC18.HLC had similar production of specific hepatic proteins, such as albumin (Fig. 4c), A1AT (Fig. 4d), and AFP (Fig. 4e), together with urea (Fig. 4f) and total bile acids secretion (Fig. 4g) at day 21, and exhibited polygonal shape, glycogen, and collagen storage (Fig. 4h). We also analysed the human-hepatocyte-specific cytochrome P450 activity (CYP3A4), after induction with rifampicin for 48 h. The results showed an approximately 2-fold induction relative to the DMSO control group for HLC derived from both hiPSC lines (Fig. 4i).

HLC derived from disease (PH1) cell line show PH1 disease phenotype

The hiPSC.PH1 cell line used for this study is derived from a PH1 patient with a common p.I244T (c.731T > C) mutation in the AGXT gene29 and to characterize PH1.HLC disease features, we analysed the key glyoxylate metabolic pathway enzymatic deficits and affected metabolites reported in PH1 disease (Fig. 5a). Briefly, the PH1 disease is characterized by the absence/deficiency of AGT enzyme activity that results in higher glyoxylate production and higher conversion of glyoxylate to oxalate (Fig. 5a)14. PH1.HLC generated by the optimized bioprocess showed a significantly higher glyoxylate synthesis (6.3 µM.10−6 cell.day−1 compared with 2.4 µM.10−6 cell.day−1), increased oxalate production (3.3 µM.10−6 cell. compared with 2.2 µM.10−6 cell.) and increase secretion rate (179.5 µM.10−6 cell.day−1 compared with 65.6 µM.10−6 cell.day−1) when compared with ChiPSC18.HLC (Fig. 5b-d). This 2-fold increase in the production of this metabolites and similar gene expression of AGXT gene at day 21(Fig. 5e), suggests a defective AGT activity which is in agreement with the typical 50% decrease of the normal AGT activity in patients with p.I244T mutation29.

Characterization of the glyoxylate metabolism in hiPSC.HLC using the optimized process (STB_4%O2). (a) Simplified glyoxylate metabolism in PH1 disease at the cellular level. AGXT, alanine glyoxylate aminotransferase. (b-c) Specific secretion rates of glyoxylate (b) and oxalate by PH1.HLC (blue bars), ChiPSC18.HLC (green bars) (d) Intracellular Oxalate levels in PH1-HLC (blue), ChiPSC18.HLC (green). (e) AGXT gene expression in PH1.HLC (blue) and ChiPSC18.HLC (green) by qRT-PCR quantified using the 2−ΔΔCT method relatively to day 0 of differentiation and normalized for GAPDH and 36B4 housekeeping genes. Data shown represents mean ± SEM. p ≤ 0.05(*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***). nPH1.HLC=3, nChiPSC18.HLC=2.

Discussion

Scalable and efficient bioprocesses to produce functional HLC are essential for the rapid translation of these products in cell-based therapies (including liver transplantation), drug screening, toxicology and disease modelling. Although remarkable progress has been made by our group and others towards the use of stirred tank bioreactor technology for the production of HLC as 3D aggregates18,30 or microcarriers31, the range of values reported for maximum cell concentrations are between (0.5 × 106-1.5 × 106 cell/mL), differentiation efficiencies (90%) and the functionality of HLC are still low taking into account the cell numbers of functional HLC required for therapeutic applications (more than 109 of hepatocytes are generally required)32.

In this study, we take advantage of the use of environmentally controlled stirred tank bioreactors for bioprocess intensification of HLC production. For the first time, we demonstrate the importance of controlling the DO concentration at low levels (4%O2) during hepatic specification stage to improve cell proliferation as 3D aggregates, their commitment towards HLC and the HLC’s quality attributes. When dissolved oxygen was controlled at low levels, higher hiPSC.HLC production (approx. 2 × 106 cell/mL) and differentiation efficiencies (approx. 80% Albumin+ cells) were obtained when compared to stirred-tank bioreactors operated under atmospheric levels of oxygen (approx. 0.6 × 106 cell/mL and 43% Albumin+ cells). The hiPSC.HLC generated with the optimized bioprocess showed synthesis of key hepatic proteins (albumin, alpha 1 antitrypsin), urea and bile acids secretion as well as drug metabolization capacity, CYP450 activity and glycogen storage. We also validated bioprocess reproducibility with hiPSC derived from a PH1 patient, showing that the produced HLC can recapitulate the key fundamental mechanisms of the PH1 disease, representing a useful tool to evaluate new drugs in a patient specific scenario.

Physiological oxygen concentrations reported for human tissues/organs in embryonic development vary from 1 to 5% depending on the tissue/organ33. Low oxygen concentration in vitro culture has been continuously reported to be beneficial for pluripotent stem cell culture, but little is known about the role of low oxygen concentration in hepatocyte differentiation34. Some studies have shown that atmospheric hypoxia can stimulate and promote hepatic progenitor differentiation6 while other reports show that can deteriorate hepatic maturation35,36. Here, we observed that hypoxic stimulus (4%O2) between day 4 and day 14 of hepatic differentiation (hepatic progenitors’ stage) significantly improved (by 3-fold) the proliferation of hepatic progenitors. Additionally, a pattern of increased expression of HIF-related genes and reduced expression of ROS-associated genes was observed in our work. In fact, hypoxic culture conditions were shown already to activate HIF and regulate the signalling pathways that promote stem cell differentiation37. During liver development, HIF expression can be critical, especially in the early stages of organogenesis, before blood circulation, with the indication that early hepatic progenitors’ expansion requires transient exposure to hypoxic conditions37. Previous studies also demonstrated that higher ROS concentration in cell culture, induced by higher oxidative stress environment, is associated with DNA damage and cell apoptosis in hepatic cultures38, thus compromising cell proliferation. In agreement with these studies, the lower oxidative stress environment attained in our optimized bioprocess, i.e. STB_4%O2, promoted higher cell proliferation during the hepatic progenitors’ stage when compared to the STB_21%O2.

At the end of the differentiation (day 21), a significant increase in the expression of hepatic specific markers and in the percentage of albumin-positive cells show the positive effect of physiological levels of oxygen on differentiation efficiency, improving cell culture homogeneity in HLC (approx. 80% Albumin+ cells) without compromising cells quality attributes. Importantly, the optimized bioprocess was validated with hiPSC derived from different donors (healthy donor and PH1 patient) confirming the robustness of our protocol.

HLC generated from hiPSC.PH1 successfully recapitulate metabolic features of the PH1 disease, showing a significant increase in the production of oxalate and glyoxylate compared to HLC differentiated from hiPSC of a healthy donor. Although previous studies have already demonstrated the use of hiPSC cells derived from PH1 patients as a proof of principle for PH1 disease modelling13,39 these studies relied on the use of static monolayer systems for the hepatic differentiation process, that present several limitations in what concerns scalability and reproducibility. Our work was the first study that shows the successful generation of hiPSC.HLC from a PH1 patient in stirred-tank bioreactors in a scalable and consistent manner, accelerating the generation of new knowledge on PH1 disease and potentiating the development of more efficient therapies. For example, further studies can be pursued to evaluate the capacity of PH1.HLC to respond to molecules that are known to reduce oxalate secretion in vivo (e.g., Vitamin B6, pyridoxamine, pyridoxal) and to evaluate future therapeutic agents40. Moreover, novel gene-editing tools like CRISPR/Cas9, can be tested to correct the AGXT mutation, repairing the PH1 disease phenotype, serving as a crucial step towards eventual clinical application40. The clinical utilization of CRISPR/Cas9 technology demonstrates significant promise in addressing rare genetic disorders. Notably, the recently FDA-approved cell-based gene therapy, Casgevy, has made substantial strides in effectively combating sickle cell disease[,41,42. Although further validation with other hiPSC lines and sources would be needed, it is expected that the bioprocess optimized in our work can be further applied towards the development of iPSC-based models of other liver genetic diseases. To date, several studies have shown liver disease models with different pathologies using hiPSC derived from patients namely, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency43, alpers-huttenlocher syndrome44 and Wilson disease45. In most of these in vitro modelling, the authors were able to show the effects of the disease mutation and to show the molecular signatures of the disease phenotype.

This work reports a scalable and reproducible bioprocess for the generation of HLC in stirred-tank bioreactors, showing the importance of controlling DO at physiological levels during hepatic progenitors’ stage to increase cell proliferation and differentiation efficiency. A total of 400 × 106 cells in a 200mL bioreactor run were achieved. To our knowledge this is the highest number of HLC generated per mL in stirred-tank bioreactors, thus providing important insights towards up-scaling the production of the cells. This will strengthen the application of HLC not only in cell therapy but also in drug discovery, toxicity testing and disease modelling. If we consider the cell numbers required for therapeutic applications (109-1010)31, we could reach this cell number scaling up our optimized bioprocess to 0.5–5 L. Moreover, because HLC cannot fully express the function of mature hepatocytes, future experiments should focus on improving the maturation of the generated HLC to meet the needs of in vivo transplantation and in vitro model development. To date, several methods to promote HLC maturation have already been reported. Adding oncostatin M as well as the hepatocyte growth factor to the culture media was shown to increase hepatocyte maturation46. Additionally, the overexpression of activating transcription factor 5 (ATF5), CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (c/EBPα), and prospero homeobox protein 1 (PROX1) was also found to improve HLC maturation and function47. These maturations strategies could then be integrated in the bioprocess that was developed in this work.

Methods

hiPSC culture

Two hiPSC lines were used in this work: hiPSC.PH1, that was derived from peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) obtained from a patient diagnosed with primary hyperoxaluria type 1 (PH1) with a p.I244T (c.731T > C) mutation in the AGXT gene39, and ChiPSC18 derived from Human skin fibroblasts from a healthy individual48. The hiPSC.PH1 line is registered at the Spanish National Cell Bank, and the ChiPSC18 is from Takara BioEurope AB, Göteborg, Sweden (Cat. No.Y00305).

Both hiPSC lines were routinely propagated in static culture conditions (T-flasks) in Cellartis® DEF-CS Xeno-Free 500 Culture System (Cat. No. Y30045, Takara BioEurope AB, Göteborg, Sweden) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% (v/v) CO2, as described previously30, and according to manufacturing instructions. Briefly, hiPSC were split typically every 3–4 days at 80–90% confluency and seeded at 3–4 × 104 cell/cm2, the culture medium was changed every day. Cells were dislodged by rinsing with Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, EUA) and incubation with Versene (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, EUA) for 20 min at 37 °C, sedimented by centrifugation and the pellet resuspended in Cellartis® DEF-CS Xeno-Free 500 culture media. Cell concentration and viability were determined using the Trypan Blue exclusion method in a Fuchs-Rosenthal hemocytometer, as described elsewhere49.

hiPSC expansion and hepatocyte differentiation in bioreactors

Hepatocyte differentiation was performed in stirred tank bioreactors (DasGip CellFerm-Pro bioreactor system, Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) operated in perfusion. Bioreactor cultures were performed in a working volume of 200 mL using flat bottom bioreactor vessels equipped with trapezoid shaped paddle impellers with long arms as previously reported30,49,50. hiPSC were inoculated at a density of 2.5 × 105 cell/mL as single cells and cultured in Cellartis® DEF-CS Xeno-Free 3D Spheroid Culture Medium (Cat. No. Y30047, Takara BioEuropeAB, Göteborg, Sweden) as described elsewhere49. During the expansion step (from day − 4 to day 0, Fig. 1a) cells were cultured at 37 °C with a surface aeration rate of 0.1 vvm with of 5% (v/v) CO2 and DO of 4%O2 (18% of air with 21% of oxygen). The stirring rate was set to 80 rpm. A metallic microsparger (of 10–30 μm pore size) was connected in the outlet perfusion line as cell retention device to prevent aggregate loss. Perfusion was initiated 24 h post-inoculation and was operated by automated gravimetric control, as described before51 at a constant dilution rate (1.3 day−1) for 4 days.

After expansion, the hepatic differentiation step was initiated (additional 21 days of culture time), during which cells were cultured under defined and controlled conditions as previously reported by our group30. Briefly, perfusion was interrupted, and the medium was replaced by Definitive Endoderm Day 1 Medium (Basal Medium for Definitive Endoderm Differentiation Cat. No. Y11135, concentrate Day 1 Cat. No. Y11132, Takara BioEurope AB, Göteborg, Sweden). Complete medium exchanges (all from Takara BioEurope AB, Göteborg, Sweden) were then performed at specific time-points of the differentiation step: day 1 (Basal Medium for Definitive Endoderm Differentiation Cat. No. Y11135, concentrate Day 1 Cat. No. Y11133), day 2 (Basal Medium for Definitive Endoderm Differentiation Cat. No. Y11135, concentrate Day 3&4 Cat. No. Y11134), day 4 (Basal Medium for Progenitor Differentiation Cat. No. Y11136, Hepatocyte Progenitor Medium Concentrate Cat. No. Y11111), day 9 (Basal Medium for Hepatocyte Differentiation Cat. No. Y11137, Hepatocyte Differentiation Medium Concentrate Cat. No. Y11112) and day 14 (Cellartis Hepatocyte Maintenance medium Cat. No. Y30051). For the complete medium exchanges, impeller agitation was paused, allowing the cell aggregates to settle by gravity for 10–15 min. After settling, the medium was carefully removed using a sampling tube. Fresh medium was then added to the culture vessel to continue hepatic differentiation. Perfusion was operated at defined dilution rates according to our previous work30. During the progenitor’s stage from day 4 to day 14 of differentiation, cells were cultured under two different conditions, in STB_21%O2 with atmospheric DO (21%O2) and in STB_4%O2 under physiological levels of DO (4%O2) both at 37 °C with a surface aeration rate of 0.1 vvm and 5% CO2. From day 1 to day 4 and from day 14 to day 21 of hepatic differentiation cells in both STB_21%O2 and STB_4%O2 conditions were cultured with atmospheric DO (21%O2) at 37 °C; surface aeration rate: 0.1 vvm; CO2: 5% (v/v). Stirring rate was set to 80 rpm. The methodologies used to estimate cell viability, concentration and aggregate diameter are detailed in the Supplemental data.

Whole mount immunofluorescence microscopy of hiPSC.HLC aggregates

Cell aggregates harvested from the bioreactor were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA) + 4% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min at room temperature (RT, approx. 18–20 °C). Fixed cells were washed three times with DPBS and permeabilized/blocked in DPBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 and 0.2% (v/v) gelatine from cold water fish skin for 20 min at RT. Subsequently, cells were washed three times with DPBS, and cells were incubated with Albumin (1:200, Abcam) and AFP (1:200, Sigma) primary antibodies for 2 h at RT. Cell aggregates were then washed three times with DPBS and incubated in the dark for 1 h at RT with secondary antibodies Alexa Flour 594 (Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) (diluted 1:1000 in 0.125%FSG + 0.1% Triton X-100), diluted in 0.125%FSG + 0.1% Triton X-100. Cell aggregates were mounted in ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen), containing 40,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), in ibidi® chambers. Immunofluorescence images were recorded with a confocal microscope (SP5, Leica). The obtained images were processed using FIJI software.

Flow cytometry

Analysis of hiPSC (day 0) and HLC (day 21) phenotype was assessed by flow cytometry. Briefly, cell aggregates were collected from bioreactor cultures and single-cell suspensions were prepared by incubating the cells with TrypLE Select (5–10 min) or 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (15–45 min) respectively for hiPSC and HLC. Cells were centrifuged, washed with DPBS and filtered through a 200 μm cell strainer (BD Pharmingen). For intracellular epitopes, 1 × 106 cells were fixed and permeabilized using Inside Stain Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to manufacturer’s instructions. After two washing steps cells were incubated with ALB (1:50, Abcam, ab8940), AFP (1:50, Sigma, A8452) or isotype controls for 30 min at RT. Cells were washed three times and incubated with Alexa 488 anti-mouse IgG1 (1:200, Invitrogen, A-11001) or Alexa 488 anti-mouse IgM (1:200, Invitrogen, A-21042) during 30 min, at RT, in the dark. Data was acquired on a BD FACSCelesta™ Cell Analyzer (BD biosciences) and analysed in FlowJo software (FlowJo LLC, http://www.flowjo.com/). A minimum of ten thousand events were registered for each sample.

Gene expression analysis

Cells from static culture, dissociated with TrypLE Select (Gibco Life Technologies) for 5 min at 37 °C, and aggregates collected from the bioreactor were centrifuged at 300 x g for 5 min. These pellets were washed with DPBS, snap-freezed with liquid nitrogen and kept at -80 °C. mRNA was extracted using the High Pure RNA Isolation kit (Roche) according to manufacturer’s instructions. mRNA was quantified using a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and cDNA synthesized with 200 ng RNA per sample, using the Transcriptor High Fidelity cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). RT-qPCR reactions of 10 µL included 2 µL of cDNA (diluted 1:2 in RNase free water), 0.5 µL of forward and reverse primers (5 µM) (Table S1), 5 µL of LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master Kit (Roche) and 2 µL of RNase free water and were analysed in the LightCycler 480 Instrument II-384 well block (Roche). The thermal cycle had an initial pre-incubation step for 10 min at 95 °C; 45 cycles of amplification with denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s and annealing at 62 °C for 10 s; extension at 72 °C for 15 s. Each sample was run in triplicate and data analysed in LightCycler 480 Software v1.5.0 (Roche). Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method52, normalized to housekeeping gene GAPDH1 (carbohydrate metabolism protein) expression and represented relative to the control sample (set at 1). The methodologies used for Bulk RNA-seq analysis and metabolic profiling are detailed in the Supplemental information.

Alpha 1 antitrypsin, albumin, alpha fetoprotein, urea, and total bile acids production

Supernatant media was collected on day 21, centrifuged (300 x g, 5 min) and kept at -20 °C prior to analysis. The concentration of secreted albumin in the supernatant was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Bethyl, Montgomery, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Human alpha 1 Antitrypsin and Alpha fetoprotein was analysed by ELISA Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Urea and total bile acids content were measured using commercially available kits (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Synthesis rate of hiPSC.HLC aggregates was calculated according to the general mass balance equation: q = (ΔC/Δt – D × (Cin – Cout))/XV average, where q is the specific synthesis rate, ΔC/Δt is change rate in the supernatant, D is the dilution rate, Cin and Cout are the inlet and outlet concentrations, and XV average is the average of viable cell concentrations during the time period Δt.

Oxalate and glyoxylate production

Supernatant media was collected on day 21, centrifuged (300 x g, 5 min) and kept at -20 °C prior to analysis. The concentration of secreted oxalate and glyoxylate content were measured using commercially available kits (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Synthesis rate of hiPSC.HLC aggregates was calculated according to the general mass balance equation: q = (ΔC/Δt – D × (Cin – Cout))/XV average, where q is the specific synthesis rate, ΔC/Δt is change rate in the supernatant, D is the dilution rate, Cin and Cout are the inlet and outlet concentrations, and XV average is the average of viable cell concentrations during the time period Δt.

Cytochrome P450 activity and inducibility

We measured CYP3A4 activity using P450-Glo CYP3A4 Assay (Luciferin-IPA) (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) The luciferase-based system was performed according to the supplier’s instructions and luminescence was determined in a microplate reader (Tecan Infinite 200 PRO NanoQuant). Cells were exposed to 25 µM of Rifampicin (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri) for 48 h to induce CYP3A4 or DMSO (0.1%) as the control group. Relative activity was measured by taking into consideration the amount of activity in the inducer group relative to DMSO. The data were normalized to viable cell numbers using luminescent cell viability assay (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA).

Indocyanine green uptake and clearance

A stock solution (5 mg/mL) of indocyanine green (Cardiogreen, Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared in ddH20. Then, the working solution (1 mg/mL) was done in hepatocyte maintenance medium at 37 °C to dissolve the powder completely. For analysis of indocyanine green uptake and clearance, hiPSC.HLC 3D aggregates harvested at day 21 were seeded at a density of 2 × 106 cell/well in 24-well plates (Falcon™), coated with growth factor reduced (GFR) Matrigel®, Phenol Red Free (BD Biosciences). Aggregates were incubated in hepatocyte maintenance medium supplemented with 1 mg/mL indocyanine green for 1 h, at 37 ºC in a humidified atmosphere with 5% (v/v) CO2. Cells were washed tree times with DPBS and then cultured in hepatocyte maintenance medium for additional 23 h. To determine Indocyanine green uptake and release profiles, supernatants from both cultures were collected at specific time points (0 min, 30 min, 1 h, 1 h 30, 2 h, 5 h) and analysed by spectrophotometry in Tecan Infinite 200 PRO NanoQuant, microplate reader, at optical density 820 nm (OD820). Cells were visualized using inverted phase contrast microscopy (Leica DMIRB, Leica Microsystems GmbH). Representative pictures were obtained using Leica DFC 295 digital camera.

Histochemistry

hiPSC.HLC aggregates were fixed, overnight, in 10% (v/v) buffered formalin at RT and added to 1.5% (w/v) agarose (Lonza) in DPBS. Spheroids were subsequently processed and included in paraffin-blocks. Transversal sections, with 3 μm of thickness, were stained for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E, Sigma-Aldrich), Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS, Sigma-Aldrich) and Masson’s trichrome (MT, Sigma-Aldrich) according to the protocol established at the Histopathology Facility at the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (Oeiras, Portugal). Images were analyzed using NDP.view2 software.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Unless otherwise noted, statistical significance was calculated one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the post hoc turkey’s test. To take account of multiplicity in group comparisons, one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-test were conducted. Statistical significance is denoted by *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Data availability

The RNA sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the GEO database under accession code GSE267210. Datasets generated and/or analysed during this study as well as the code used are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. This study did not generate new unique reagents.

References

Asrani, S. K., Devarbhavi, H., Eaton, J. & Kamath, P. S. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J. Hepatol.70, 151–171 (2019).

Stepanova, M. et al. Direct and indirect economic burden of chronic liver disease in the United States. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.15, 759-766e5 (2017).

Heydari, Z. et al. Tissue engineering in liver regenerative medicine: Insights into novel translational technologies. Cells9, 304 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Reversal of liver failure using a bioartificial liver device implanted with clinical-grade human-induced hepatocytes. Cell. Stem Cell.30, 617–631e8 (2023).

Lee, J. H. et al. Establishment of a serum-free hepatocyte cryopreservation process for the development of an off-the-shelf bioartificial liver system. Bioengineering9, 738 (2022).

Yu, Y. et al. Hepatocyte-like cells differentiated from human induced pluripotent stem cells: Relevance to cellular therapies. Stem Cell. Res.9, 196–207 (2012).

Gao, X. & Liu, Y. A transcriptomic study suggesting human iPSC-derived hepatocytes potentially offer a better in vitro model of hepatotoxicity than most hepatoma cell lines. Cell. Biol. Toxicol.33, 407–421 (2017).

Takayama, K. & Mizuguchi, H. Generation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells for drug toxicity screening. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet.32, 12–20 (2017).

Blaszkiewicz, J. & Duncan, S. A. Advancements in disease modeling and drug discovery using iPSC-derived hepatocyte-like cells. Genes (Basel)13, 573 (2022).

Corbett, J. L. & Duncan, S. A. iPSC-derived hepatocytes as a platform for disease modeling and drug discovery. Front. Med. (Lausanne)6, 265 (2019).

Cayo, M. A. et al. JD induced pluripotent stem cell–derived hepatocytes faithfully recapitulate the pathophysiology of familial hypercholesterolemia. Hepatology. 56, 2163–2171 (2012).

Gurevich, I. et al. iPSC-derived hepatocytes generated from NASH donors provide a valuable platform for disease modeling and drug discovery. Biol. Open.9, bio055087 (2020).

Estève, J. et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells-derived hepatocyte-like cells for ex vivo gene therapy of primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Stem Cell. Res.38, 101467 (2019).

Hoppe, B. An update on primary hyperoxaluria. Nat. Rev. Nephrol.8, 467–475 (2012).

Martinez-Turrillas, R. et al. Generation of an induced pluripotent stem cell line (CIMAi001-A) from a compound heterozygous primary hyperoxaluria type I (PH1) patient carrying p.G170R and p.R122* mutations in the AGXT gene. Stem Cell. Res.41, 101626 (2019).

Mallanna, S. K. & Duncan, S. A. Differentiation of hepatocytes from pluripotent stem cells. Curr. Protoc. Stem Cell. Biol.26, 1G41–1G413 (2013).

Si-tayeb, K. et al. Highly efficient generation of human hepatocyte–like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Hepatology51, 297–305 (2010).

Yamashita, T., Takayama, K., Sakurai, F. & Mizuguchi, H. Billion-scale production of hepatocyte-like cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.496, 1269–1275 (2018).

Heidariyan, Z. et al. Efficient and cost-effective generation of hepatocyte-like cells through microparticle-mediated delivery of growth factors in a 3D culture of human pluripotent stem cells. Biomaterials159, 174–188 (2018).

Sivertsson, L., Synnergren, J. & Jensen, J. Hepatic differentiation and maturation of human embryonic stem cells cultured in a perfused three-dimensional bioreactor. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 581-594 (2013).

Willemse, J., Lieshout, R., van der Laan, L. J. W. & Verstegen, M. M. A. from organoids to organs: Bioengineering liver grafts from hepatic stem cells and matrix. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol.31, 151–159 (2017).

Kietzmann, T. Metabolic zonation of the liver: The oxygen gradient revisited. Redox Biol.11, 622–630 (2017).

Farzaneh, Z. et al. Dissolved oxygen concentration regulates human hepatic organoid formation from pluripotent stem cells in a fully controlled bioreactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng.117, 3739–3756 (2020).

Lillegard, J. B. et al. Normal atmospheric oxygen tension and the use of antioxidants improve hepatocyte spheroid viability and function. J. Cell. Physiol.226, 2987–2996 (2011).

Turner, K. J. et al. The hypoxia-inducible genes VEGF and CA9 are differentially regulated in superficial vs invasive bladder cancer. Br J Cancer. 9, 1276–1282 (2002).

Lee, J. W., Bae, S. H., Jeong, J. W., Kim, S. H. & Kim, K. W. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1)α: Its protein stability and biological functions. Exp. Mol. Med.36, 1–12 (2004).

Morel, Y. & Barouki, R. Repression of Gene expression by oxidative stress. Biochem. J.342, 481–496 (1999).

Ozaki, M. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of liver regeneration: Proliferation, growth, death and protection of hepatocytes. Semin Cell. Dev. Biol.100, 62–73 (2020).

Rumsby, G., Williams, E. & Coulter-Mackie, M. Evaluation of mutation screening as a first line test for the diagnosis of the primary hyperoxalurias. Kidney Int.66, 959–963 (2004).

Isidro, I. A. et al. Online monitoring of hiPSC expansion and hepatic differentiation in 3D culture by dielectric spectroscopy. Biotechnol. Bioeng.118, 3610–3617 (2021).

Park, Y., Chen, Y., Ordovas, L. & Verfaillie, C. M. Hepatic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells on microcarriers. J. Biotechnol.174, 39–48 (2014).

Fisher, R. A. & Strom, S. C. Human hepatocyte transplantation: Worldwide results. Transplantation82, 441-9 (2006).

Fathollahipour, S., Patil, P. S. & Leipzig, N. D. Oxygen regulation in development: Lessons from embryogenesis towards tissue engineering. Cells Tissues Organs.205, 350–371 (2018).

Shimada, H., Hashimoto, Y., Nakada, A., Shigeno, K. & Nakamura, T. Accelerated generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells with retroviral transduction and chemical inhibitors under physiological hypoxia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.417, 659–664 (2012).

Katsuda, T., Teratani, T., Chowdhury, M. M., Ochiya, T. & Sakai, Y. Hypoxia efficiently induces differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into endodermal and hepatic progenitor cells. Biochem. Eng. J.74, 95–101 (2013).

van Wenum, M. et al. Oxygen drives hepatocyte differentiation and phenotype stability in liver cell lines. J. Cell. Commun. Signal.12, 575–588 (2018).

Ayabe, H. et al. Optimal hypoxia regulates human iPSC-derived liver bud differentiation through intercellular TGFB signaling. Stem Cell. Rep.11, 306–316 (2018).

Guo, R., Xu, X., Lu, Y. & Xie, X. Physiological oxygen tension reduces hepatocyte dedifferentiation in in vitro culture. Sci. Rep.7, 5923 (2017).

Zapata-Linares, N. et al. Generation and characterization of human iPSC lines derived from a primary hyperoxaluria type I patient with p.I244T mutation. Stem Cell. Res.16, 116–119 (2016).

Weigert, A., Martin-Higueras, C. & Hoppe, B. Novel therapeutic approaches in primary hyperoxaluria. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs23, 349–357 (2018).

Frangoul, H. et al. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and β-Thalassemia. N. Engl. J. Med.384, 252–260 (2021).

Sheridan, C. The world’s first CRISPR therapy is approved: Who will receive it?. Nat. Biotechnol.42, 3–4 (2023).

Wilson, A. A. et al. Emergence of a stage-dependent Human Liver Disease signature with Directed differentiation of Alpha-1 antitrypsin-deficient iPS cells. Stem Cell. Rep.4, 873–885 (2015).

Li, S. et al. Valproic acid-induced hepatotoxicity in alpers syndrome is associated with mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening-dependent apoptotic sensitivity in an induced pluripotent stem cell model. Hepatology61, 1730–1739 (2015).

Overeem, A. W. et al. Pluripotent stem cell-derived bile canaliculi-forming hepatocytes to study genetic liver diseases involving hepatocyte polarity. J. Hepatol.71, 344–356 (2019).

Gordillo, M., Evans, T. & Gouon-Evans, V. Orchestrating liver development. Development142, 2094–2108 (2015).

Nakamori, D. et al. Hepatic maturation of human iPS cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells by ATF5, c/EBPα, and PROX1 transduction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.469, 424–429 (2016).

Asplund, A. et al. One standardized differentiation Procedure robustly generates homogenous hepatocyte cultures displaying metabolic diversity from a large panel of human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell. Rev. Rep.12, 90–104 (2016).

Abecasis, B. et al. Expansion of 3D human induced pluripotent stem cell aggregates in bioreactors: Bioprocess intensification and scaling-up approaches. J. Biotechnol.246, 81–93 (2017).

Correia, C. et al. Combining hypoxia and bioreactor hydrodynamics boosts induced pluripotent stem cell differentiation towards cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell. Rev. Rep.10, 786–801 (2014).

Tostões, R. M. et al. Perfusion of 3D encapsulated hepatocytes—A synergistic effect enhancing long-term functionality in bioreactors. Biotechnol. Bioeng.108, 41–49 (2011).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real- time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods25, 402–408 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Anders Aspegren and Takara Bio Europe AB for the technical and scientific support related with hepatic differentiation and characterization. The authors also thank IGC’s histopathology unit for the aggregate cryosections processing and imaging of H&E, PAS, and MT staining. This study was funded by a grant from ERA‐NET E‐Rare 3 research program, JTC ERAdicatPH (E‐Rare3/0002/2015) and Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia project MetaCardio (PTDC/BTM‐SAL/32566/2017). This work was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia/Ministêrio da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior (FCT/MCTES, Portugal) through national funds to iNOVA4Health (UIDB/04462/2020 and UIDP/04462/2020) and the Associate Laboratory LS4FUTURE (LA/P/0087/2020). P. V., and J. I. A. were supported by FCT fellowships SFRH/BD/145767/2019, SFRH/BD/116780/2016 respectively. NV has received funding from the H2020 Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 813453.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: PV, JIA, MS. Experiments and Procedures: PV, JIA, IEC, NV, MC. Writing: PV and MS. Review and editing: all authors. Project administration, development and funding, PA, MS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vicente, P., Almeida, J.I., Crespo, I.E. et al. Oxygen control in bioreactor drives high yield production of functional hiPSC-like hepatocytes for advanced liver disease modelling. Sci Rep 14, 24599 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75582-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75582-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

From gut to liver: organoids as platforms for next-generation toxicology assessment vehicles for xenobiotics

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2025)

-

Ex vivo organ engineering using decellularized tissue scaffolds

Nature Reviews Bioengineering (2025)

-

Advancing hepatotoxicity assessment: current advances and future directions

Toxicological Research (2025)