Abstract

Glioblastoma is an aggressive brain cancer with a poor prognosis. The O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) gene methylation status is crucial for treatment stratification, yet economic constraints often limit access. This study aims to develop an artificial intelligence (AI) framework for predicting MGMT methylation. Diagnostic magnetic resonance (MR) images in public repositories were used for training. The algorithm created was validated in data from a single institution. All images were segmented according to widely used guidelines for radiotherapy planning and combined with clinical evaluations from neuroradiology experts. Radiomic features and clinical impressions were extracted, tabulated, and used for modeling. Feature selection methods were used to identify relevant phenotypes. A total of 100 patients were used for training and 46 for validation. A total of 343 features were extracted. Eight feature selection methods produced seven independent predictive frameworks. The top-performing ML model was a model post-Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) feature selection reaching accuracy (ACC) of 0.82, an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.81, a recall of 0.75, and a precision of 0.75. This study demonstrates that integrating clinical and radiotherapy-derived AI-driven phenotypes can predict MGMT methylation. The framework addresses constraints that limit molecular diagnosis access.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glioblastoma is the most common malignant primary brain cancer in adulthood1. Despite treatment advances, prognosis remains poor with a median overall survival (OS) varying between 9 to 15 months2,3. Patients with methylation of the MGMT have been shown to have improved survival rates due to a better response to alkylating agents such as temozolomide3,4. Age is another important prognostic factor, and median survival in patients over 65 years can be as low as 4 to 5 months5. Recent studies have investigated tailoring strategies for the elderly, such as chemotherapy alone or hypofractionation6. However, evaluating MGMT methylation status is a key factor for guiding treatment allocation6,7,8. The integration of MGMT methylation into treatment planning offers the potential for personalized therapy, especially given the well-established relationship between MGMT methylation and response to temozolomide4,8.

In low and middle-income regions, the stratification of glioblastoma treatment through MGMT methylation identification is frequently thwarted by economic limitations that permeate the entire spectrum of cancer care. A stark illustration of this challenge is the accessibility of RT in Brazil, where 15.9% of patients initiate RT within the recommended 30 days post-diagnosis9. In this limited resources setting, ensuring access is imperative. Interestingly, studies have shown that elderly patients with MGMT methylated glioblastoma may achieve comparable outcomes with temozolomide alone7. Unfortunately, economic barriers preclude access to molecular medicine.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications are being progressively employed to anticipate MGMT methylation status10, symbolizing a pivotal advancement in bridging the divide in healthcare accessibility. The latest compilations of data unveil a notable enhancement in the prognostic accuracy (ACC) of these AI algorithms, with performance metrics exhibiting an expansion in the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) from 0.67 to an impressive 0.87. Such advances herald a promising horizon for the precision-oriented management of glioblastoma in resource-constrained settings11,12.

Nonetheless, most AI studies are based on costly complex imaging acquisition protocols to predict diagnostic tests such as MGMT. Also, they’re using mostly non-standardized volume of interest definitions13,14, which may hinder practical application and increase variability in results.

Hence, the study objective was to create an AI model that utilizes readily available diagnostic images, such as T1 weighted image gadolinium-enhanced (T1GD) and T2-Flair MRIs to predict MGMT test results. The imaging data was extracted from predefined regions of interest following standardized tumor definition protocols, and combined with clinical and neuroradiological assessments.

Methods

Data collection

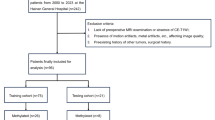

This study utilized two data sources. The training cohort’s data was retrieved from The Cancer Imaging Archive’s, the UPENN-GBM database15, a National Institute of Health (NIH) sponsored repository. The validation cohort comprised GBM patients from a single Brazilian institution with inclusion criteria of cranial MRI and MGMT data. To select cases from the UPENN-GBM database, 100 cases were randomly chosen based on the following eligibility criteria: availability of MGMT status and IDH mutation information, high-quality T1GD, and T2-Flair images. Additionally, these cases had to meet radiation oncology standards, including volumetric slices with a maximum thickness of 1 mm for T1WI and the absence of artifacts.

The diagnostic T1GD and T2-Flair MR images were evaluated by radiation oncologists (tumor delineation) and neuroradiologists (standardized radiological interpretation). The patient’s clinical features acquired from medical records were age, sex, MGMT status (defined as TARGET, for supervised learning purposes), and IDH status.

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was submitted and approved by the Brazilian National Health Council through the Brazil platform (identifier 63591922.6.0000.5461). As the study involved a retrospective analysis of hospital database records, a waiver for obtaining Informed Consent was requested and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Sírio-Libanês Hospital (ref. 5461), which also granted approval for both the research and the waiver of the informed consent form.

RadF extraction

For radiomic feature extraction (RadF), Volumes of Interest (VOI) were created by contouring following a modified version of ESTRO-ACROP 2016 guideline for target delineation in radiation therapy treatment16. The contour was made with Eclipse Treatment Planning System (Varian—Siemens Healthineers, Palo Alto, USA) and a 256 × 256 matrix size was used.

We defined three distinct VOI using two MR sequences. On the T1GD sequence, we initially outlined the gross tumor volume (GTV), identified by the contrast-enhancing lesion, referred to as T1VOL. Subsequently, we constructed a secondary VOI, extending symmetrically 2 cm from the boundaries of the T1VOL. This expansion was adjusted to respect anatomical barriers and to encompass all pathological changes evident in the T2-Flair sequence, thus defining the T1_FLAIR VOI. The third VOI, termed FLAIR, was crafted to mirror the dimensions and configuration of the T1_FLAIR, yet delineated exclusively on the T2-Flair sequence.

The DICOM images, and VOI’s as RT STRUCTURESET were exported to 3D Slicer for RadF extraction17. We used the Pyradiomic18 extension to extract 150 radiomic phenotypes from each VOI. The RadF included shape (26 features), first-order statistics (19 features), and textural features (75 features). Shape features are related to the geometric properties of the tumor. The first-order features describe the distribution of the tumor intensity. Texture features represent the heterogeneity of the tumor and were extracted from the gray level co-occurrence (GLCM)19, gray level run length matrix (GLRLM)20, gray level size zone matrix (GLSZM)21, neighboring gray-tone difference matrix19, and gray level dependence matrix (GLDM)22 matrices. The detailed calculation of these RadF is available on the Pyradiomics website18 (https://pyradiomics.readthedocs.io/en/latest/features.html). A bin width = 25 was used for gray-level discretization before texture calculation. Preprocessing filters including Laplacian-of-Gaussian and wavelet were also applied.

Categorical neuroradiology evaluation

Four expert neuroradiologists evaluated the same images following a guideline for categorical impressions of the images (Table S1 in Supplementary Appendix). The final classification was determined by consensus; if consensus could not be reached, the classification was marked as not applicable (NA).

Data frame structuring

The clinical data, RadF, and categorical assessments were unified into a spreadsheet, forming a comprehensive data frame. This data frame underwent preprocessing using Python 3.6 on the Google Colab platform. Continuous variables were normalized using the MinMax scaling technique23, while categorical variables were transformed via OneHotEncoding24, both from Scikit Learn Library. Subsequently, this data frame was divided into two separate entities: UPENN-GBM database and Private data frames corresponding to training and validation databases respectively.

To address the issue of data imbalance, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE)25 was employed to upsample the UPENN-GBM database.

Features selection

The structured data frame underwent various filtering techniques to identify the most pertinent features for predicting MGMT methylation. In univariate filters, the ANOVA F-test was applied to continuous variables and the Chi-Squared test to categorical variables, with the p-value as a varying hyperparameter set at 0.1, 0.05, and 0.0114. Also in the univariate filters, Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons were applied26. For wrapper methods, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)27 was utilized. In embedded methods, we employed the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) with an L1 penalty, alongside a LightBoost regressor28,29. Additionally, for dimensionality reduction, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to generate principal components, encompassing 95% of the variance30.

These processes resulted in new data frames, each corresponding to the different supervised machine-learning experiments to be conducted.

Machine learning experiments

The ML and DL techniques were compared. For ML, each experiment was associated with a distinct filtering method, as depicted in Fig. 1. All experiments were executed within the PyCaret31 environment, enabling a concurrent assessment of various classifiers. A total number of eighteen binary classifiers were tested; linear and quadratic discriminant analysis, trees-based classifiers (extra trees, decision trees, random forests), ridge classifier, MLP classifier, boosting algorithm (gradient boosting, ada boost, extreme gradient boosting, light gradient boosting machine, cat boost), linear and radial support vector machine, logistic regression, k-nearest neighbors classifier, Naive-Bayes, and gaussian process classifier. A standard setup was maintained across all experiments in terms of pre-processing parameters. The UPENN-GBM, with 100 patients, database was utilized for training and testing the models, while the Private dataset, with 46 patients, was reserved as a validation set, and consequently not involved in the modeling process (unseen data).

Workflow summary demonstrating the VOI’s delineation by experts from the radiation oncology field using T1GD and T2-Flair weighted sequences, the neuro-radiology assessment was carried together in this phase. Subsequently, these images together with the created VOI’s underwent RadF extraction. The data was then generated. Different ML experiments were carried out and compared with DL experiments.

For the model construction, the UPENN-GBM database was divided into a 70:30 ratio, resulting in x_train, y_train, x_test, and y_test subsets. Here, ‘x’ represents the input variables used by the algorithm for predicting ‘y’, the TARGET variable. The efficacy of the models was assessed using a tenfold Stratified K-Fold cross-validation approach. To address multicollinearity the threshold was set for 80%, this was made by Minimum absolute Pearson correlation, thus, if any column was correlated with each other equal to or higher than this threshold, it would be removed.

The top five algorithms, based on their initial performance comparison, underwent hyperparameter tuning using the Optuna Library32 where applicable.

These models were refined using ensemble bagging and either blending or stacking techniques and evaluated with tenfold cross-validation. The predictions of the base models are provided as features for the meta-model. The selection of the best-performing model was based on ACC and AUC metrics, and then applied to the private dataset, which remained unseen so far, to assess its robustness and effectiveness in handling new datasets.

Implementation of deep learning workflow

Data frame structuring

For DL methodologies, the training dataset includes MR studies of T1GD and T2-Flair for GBM patients from a public dataset UPENN-GBM. Only slices containing structure sets were used to train the models. To increase the size of the training set and make the model more robust to variations in the data, data augmentation was applied to the original training images by performing random rotations of ± 7 degrees and translations of ± 2 mm. The model’s output is a probability that ranges from 0 to 1, for unmethylated and methylated, respectively. After the training, the models are tested using a different set of 46 images of GBM patients issued from private data.

DL experiments

For DL experiments, three models have been used to predict the output. The first model, as demonstrated in Fig. 2, consists of three convolutional layers with adjustable filter sizes, three max-pooling layers for downsampling, a flattening layer, and two dense layers with adjustable units.

Architecture of Model 1 (top) and Model 2 (bottom) for predicting MGMT methylation status from T1GD and T2-Flair. Both models take separate T1 and FLAIR images as input, with Model 1 consisting of three convolutional layers and three pooling layers, and Model 2 adding two extra convolutional and pooling layers. Both models end with a flattening layer and two dense layers to output the methylation prediction. The dimensions for each layer can be found in Table S5 in the supplementary appendix.

In the second model, we have added two additional convolutional layers and an additional pooling layer after each convolutional layer. This increases the depth of the model, allowing it to capture more complex features and patterns in the images.

In the third model, a dual-branch CNN architecture was employed. Each branch consists of multiple convolutional and pooling layers to extract distinct image features. The first branch uses 3 × 3 filters followed by batch normalization and max pooling. The second utilizes 5 × 5 filters to capture different spatial patterns followed by the same normalization and pooling steps. Feature maps from both branches are concatenated before being fed into a fully connected layer for classification.

We used data augmentation, L2 regularization, a dropout layer with a 20% rate, batch normalization, learning rate scheduling, and early stopping to reduce overfitting.

The loss function adopted for training is “binary Cross-entropy” and the optimizer used is ADAM (Adaptive Moment Estimation).

For all the models, a thorough hyperparameter tuning process was conducted using the Keras Tuner library. The best hyperparameters including, the number of filters, the number of units in the densely connected layer, the learning rate, the batch size, and the number of training epochs were determined through a random search with 10 trials.

Statistical analyses

For the primary endpoint assessment and validation of model metrics, each model’s performance was evaluated based on its ACC, AUC as the quality of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, recall (sensitivity), precision, F1 score, Kappa, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC). Exploratory analysis was made, for continuous variables T-test and Mann–Whitney U test were performed when applicable. For categorical variables, the Fisher Exact Test and Chi-squared were performed. Statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS version 20, and Python 3.6, a two-sided p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

In total, 146 patients were selected for further analysis. One hundred from the UPENN-GBM database (training set) and 46 from the private institution (validation set). The median age was 63.7 for the training set and 57.5 years for the validation set. Table 1 presents baseline characteristics.

Feature extraction

Using Pyradiomics, 450 RadF’s were extracted and narrowed down to 330 after eliminating location-specific and redundant features. These were merged with 13 categorical and clinical characteristics. To balance the dataset, SMOTE generated 22 synthetic cases, equalizing the proportions of MGMT-methylated patients. The illustration of the 8 filtering methods can be accessed in Figure S1 in the Supplement Appendix, it yields diverse results: PCA identified 24 principal components, ANOVA F test and Chi-square tests at varied p-values isolated 1, 8, 15, and 44 features, while LASSO Regression and LightBoost pinpointed 21 and 74 features, respectively. RFE selected 17 features.

Algorithms

Across eight experiments, 105 algorithms were developed, and the best from each was selected, yielding seven top performers detailed in Table S4 of the Supplementary Appendix. Access to the datasets and codes was also provided. The multivariable filter with Bonferroni correction for p-value threshold resulted in only 1 feature deemed as significant, therefore precluded algorithm development.

Best performance in training and validation set

The best performance on the UPENN-GBM database was achieved using RFE with a stacked estimator with Linear Discriminant Analyses and Extreme Gradient Boosting with Logistic Regression as the final estimator. As seen in Fig. 3, this estimator reached an ACC of 75.68%, an AUC of 0.78, a recall of 0.83, a precision of 0.71, an F1 score of 0.77, a Kappa value of 0.52, and an MCC of 0.52. However, when applied to the validation set, the ACC of 0.71, an AUC of 0.63, a recall of 0.5, a precision of 0.61, an F1 score of 0.55, a Kappa value of 0.35, and an MCC of 0.35.

Conversely, the best performance on the unseen dataset was obtained using a blended model with Ridge classifier post-LASSO feature selection. On unseen data, the model reached an ACC of 0.82, an AUC of 0.81, a recall of 0.75, a precision of 0.75, an F1 score of 0.75, a Kappa value of 0.62, and an MCC of 0.62. However, on the test set, the blended model had a lower performance with an ACC of 0.69, an AUC of 0.69, a recall of 0.74, a precision of 0.63, an F1 score of 0.68, a Kappa value of 0.38, and an MCC of 0.38. The summary of all performances is presented in Table 2.

Secondary analyses

We investigated correlations between clinical factors like tumor specifics and patient age with MGMT methylation, detailed in Table 3. Neuro-radiology expert opinions were consistent across categorical analyses, with no significant variance (Fisher’s exact p > 0.05). Their impressions according to MGMT status can be accessed in Table S2 in the supplementary appendix.

Regarding continuous variables, 42 variables showed a significant association with MGMT status. The interrelationships among these variables were thoroughly assessed and are illustrated in the subsequent heatmap. The Spearman-test showed out of approximately 1,500 interactions, only 25 were significant (p-value < 0.05) with correlations from 0.96 to 1.0. Four of these were negative correlations (−0.93 to −0.94), indicating mostly weak to moderate phenotype relationships. These findings can be visualized in Fig. 4.

To access the description of each variable, refer to Table S3 in the Supplement Appendix.

DL models

After training the models on the UPENN-GBM database, the best hyperparameters obtained for the first custom-developed CNN model were: 48 filters, 112 filters, and 256 filters for the first, second, and third convolution layers respectively. 80 units for the densely connected layer, 0.0001 for the learning rate, 16 for the batch size, and 10 training epochs. The best ACC achieved was 69%, and the precision was 70%. Figure 5 graphs A and B illustrate the ACC and loss graphs created during the training and testing phases, while C and D for the second CNN model.

For the last model, the best hyperparameters were 16 and 64 for the first two convolution layers and 128 units for the densely connected layer. For the second path, the best hyperparameters were 32 and 128 for the first two convolution layers and 128 units for the densely connected layer. The training epochs was 15. The best ACC achieved was 63% and a precision equal to 61%.

When evaluated on unseen data, the accuracy achieved was 51, 52, and 54% for the first second, and the third model respectively. For cross-validation, the models demonstrated mean accuracies of 0.45, 0.52, and 0.53, with standard deviations of 0.08, 0.09, and 0.11 for the first, second, and third models, respectively.

Discussion

The present study provides a framework for predicting MGMT methylation by the application of AI techniques on diagnostics MRIs together with clinical information. The final best algorithm reached 0.82 ACC, 0.81 AUC with 0.75 recall when applied to unseen data. Notable variations in performance were observed, as shown in Table 2, and there are a few possible explanations for this like the differences between cohorts and possible overfitting.

Overfitting is a phenomenon that occurs when a model is overly trained on the features of the training set, leading to poor generalization when applied to new, unseen data33. It is more likely to occur when numerous variables are used to create the model. To address this, several methods for feature selection were applied, with L1 penalization in LASSO being the most significant. L1 regularization is known to be more effective than L2 regularization in situations where many irrelevant features are present. It promotes sparsity by reducing the weights of irrelevant features to zero, allowing the model to focus on the most important variables34.

The results align with previous theories, as the algorithm utilizing LASSO regression demonstrated the best performance on unseen data, reflecting its ability to generalize effectively. However, its performance on the test set was not as strong, which could be attributed to significant differences in patient characteristics between the two cohorts (100 patients from the UPENN-GBM database versus 46 from private data). These population differences may have impacted the algorithm’s effectiveness. However, even with this unbalance, to validate the results with an independent cohort brought a strong characteristic for this study.

Besides LASSO regression, the implementation of multiple filters in the pre-processing phase is another strong point of this research. Typically these models utilize only a small subset of these features after applying filtering techniques13,14,35,36. Regrettably, most studies used only one or a few methods for feature filtering, potentially overlooking the value of other filter methods14. The number of features considered significant by every filtering method can be assessed in Figure S1, supplement appendix.

Several previous studies have attempted to demonstrate the viability of using AI to predict MGMT methylation, with some achieving better performance than our results. However, specific steps were taken in this study to add unique value and contribute to the existing literature37.

To our knowledge, no published articles have yet explored the use of radiomic features extracted from radiotherapy-derived volumes to predict MGMT methylation. However, radiotherapy remains a critical component of the gold-standard treatment for glioblastoma. The ESTRO-ACROP guideline was adapted to create the VOI from which the RadF would be extracted16 representing an effort to allow reproducibility for this framework (Fig. 1). This is in contrast with previous research that was mostly based on experts’ qualitative perspectives, i.e. defining disease areas10,35 or used AI-based tools to auto-contour these tumors10.

This study intentionally utilized only two MRI sequences that are generally already performed for radiation therapy treatment planning to align with constraints in low-resource settings.

Many studies employed the use of different modalities of MRI’s. Some authors identified the predictive value of Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) values, these findings proved to be significant predictors of MGMT methylation38,39. These advances can also be extended to the analysis of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET), which has also been shown to be significant40. Other authors have also successfully evaluated PET 18F-DOPA (3,4-dihydroxy-6-[18F]fluoro-L-phenylalanine) with the same goal, achieving reasonable results with approximately 80% accuracy. Interestingly, they found that certain radiomic features were significantly associated with MGMT methylation41.

However, such an approach may not be feasible in resource-limited settings due to limited access to these technologies. OECD data shows that Brazil has only 6.7 MRI devices per 1 million citizens, compared to around 30 in countries like Germany and the United States42.

To create an algorithm with broad social generalizability, we limited ourselves to using only two weighted MRI sequences, the most relevant for delivering radiotherapy. Previous findings support this strategy, as algorithms based on single-modality MRI have achieved AUCs up to 0.82, similar to our results10,11. Conversely, other studies using similar approaches reported poorer performances43, highlighting the equipoise in continuing research in this area.

The neuroradiologist interpretation, together with other clinical features, was intentionally combined with AI-derived, i.e. RadF, once previous studies demonstrated an increased predictive performance of AI algorithms11,44. We hypothesized that the clinical perspective is relevant to algorithm engineering.

Mann–Whitney U test found 42 RadFs significantly linked to MGMT methylation. However, experiments with this number of features led to poor performance. Common statistical tests like ANOVA and Chi-Squared couldn’t manage type I errors well, resulting in many false positives and poor performance. Using the Bonferroni correction, only one variable was selected, highlighting its conservative nature and the high risk of type II errors, excluding significant variables, a finding already present in previous genome-wide analyses45. In other words, these results indicate that common statistical methods do not provide the optimal balance between the odds of type I and II errors, leading to inaccurate outcomes.

Additionally, the majority of the correlation between features was determined as weak to moderate by Spearman’s test. This adds a layer of complexity, especially once high correlations ultimately lead to multicollinearity in AI algorithm development46. This condition can make it difficult to predict the impact of these variables and potentially cause overfitting47, reducing the algorithm’s ability to generalize to new data. To address this, we applied a collinearity filter at each step using Pearson’s correlation coefficient with a threshold of 0.8.

It’s important to note that in 2021, the World Health Organization introduced a new classification system for Central Nervous System tumors. Under this new framework, four patients in our cohort would no longer be classified as having glioblastoma. This represents a limitation of our study. However, these patients were treated as glioblastoma cases because their diagnoses were made prior to the new classification, and they underwent MGMT methylation testing. Since the primary goal of our research was to predict MGMT methylation status, these patients were included in the analysis.

Another point to explore is the difference in DL and ML performances. There was a considerable difference in ACC performance, 0.54 vs 0.82 for DL and ML, respectively. Our results showed that while the second and third CNN models showed similar average performance, the third model had the highest variability (standard deviation of 0.11). These results also suggest that the performance of the CNN models may be more sensitive to the specific data used in training, indicating potential overfitting or instability. These findings underscore the challenges in achieving a balance between model complexity and generalization.

Recently, DL has become an important approach in ML techniques, and due to its ability to better deal with massive amounts of data, it has been reaching outstanding performances while dealing with complex tasks48. In the present study, a CNN strategy was used for predicting MGMT status, this approach is known to deal with large amounts of images properly and is thus useful for this specific task49.

In addition to expanding the dataset, refining model architecture could potentially enhance DL’s predictive power.

Despite existing challenges, the algorithm showed a relevant performance, utilizing minimal resources like the number of MRI sequences used and clinical data efficiently, and finally reaching similar results to those previously published. It is important to note that this algorithm is not intended to replace molecular testing for MGMT methylation but rather to function as a pre-test tool, helping to identify patients at higher risk of presenting this mutation. Enhancing this framework while maintaining simplicity could be crucial for enabling reproducibility in low- to middle-income countries, suggesting that strategic improvements could broaden its applicability without sacrificing accessibility.

Conclusion

This research highlights the potential of an affordable AI tool to enhance clinical decision-making in oncology, where molecular characteristics of tumors are crucial. It shows AI’s ability to improve clinical outcomes through precision medicine, even in resource-constrained settings, advancing equitable healthcare in oncology.

Data availability

This project will share most of the data generated to formulate the presented results. Additionally, the code used for algorithm development will be available online for public access. For requesting access to data, Dr Felipe Cicci Farinha Restini should be contacted.

References

Ostrom, Q. T. et al. CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2016–2020. Neuro Oncol. 25, iv1–iv99 (2023).

Brown, N. F. et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in glioblastoma. Cancers 14(13), 3161 (2022).

Stupp, R. et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 352(10), 987–996. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa043330 (2005).

Hegi, M. E. et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 352(10), 997–1003. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa043331 (2005).

Marta GN, Moraes FY, Feher O, et al. Social determinants of health and survival on Brazilian patients with glioblastoma: a retrospective analysis of a large populational database. The Lancet Regional Health – Americas 4. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(21)00062-4/fulltext. [Accessed on: 20 Jan 2024]. (2021).

Perry, J. R. et al. Short-course radiation plus temozolomide in elderly patients with glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 376(11), 1027–1037 (2017).

Wick, W. et al. Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 13(7), 707–715 (2012).

Rivera, A. L. et al. MGMT promoter methylation is predictive of response to radiotherapy and prognostic in the absence of adjuvant alkylating chemotherapy for glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 12(2), 116–121 (2009).

RT2030 - Home [Internet]. Sociedade Brasileira de Radioterapia. Available from: https://sbradioterapia.com.br/rt2030/. [Accessed on: 21 May 2023]. (2023).

Chen, S. et al. Predicting MGMT promoter methylation in diffuse gliomas using deep learning with radiomics. J. Clin. Med. 11(12), 3445 (2022).

He, J. et al. Multiparametric MR radiomics in brain glioma: models comparation to predict biomarker status. BMC Med. Imaging 22(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-022-00865-8 (2022).

Sasaki, T. et al. Radiomics and MGMT promoter methylation for prognostication of newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 14435 (2019).

Gómez, O. V. et al. Analysis of cross-combinations of feature selection and machine-learning classification methods based on [18F]F-FDG PET/CT radiomic features for metabolic response prediction of metastatic breast cancer lesions. Cancers 14(12), 2922 (2022).

Pudjihartono, N., Fadason, T., Kempa-Liehr, A. W. & O’Sullivan, J. M. A Review of Feature Selection Methods for Machine Learning-Based Disease Risk Prediction. Front. Bioinform. 2, 927312 (2022).

The University of Pennsylvania glioblastoma (UPenn-GBM) cohort: advanced MRI, clinical, genomics, & radiomics | Scientific Data. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-022-01560-7. [Accessed on: 20 Jan 2024]. (2024).

Niyazi, M. et al. ESTRO-ACROP guideline “target delineation of glioblastomas”. Radiother. Oncol. 118(1), 35–42 (2016).

Fedorov, A. et al. 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn. Reson. Imaging 30(9), 1323–1341 (2012).

van Griethuysen, J. J. M. et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 77(21), e104–e107 (2017).

Haralick, R. M., Shanmugam, K. & Dinstein, I. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. SMC3(6), 610–621 (1973).

Galloway, M. M. Texture analysis using gray level run lengths. Comput. Graph. Image Process. 4(2), 172–179 (1975).

Texture indexes and gray level size zone matrix. Application to cell nuclei classification – ScienceOpen. Available from: https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=2c91747d-b5c9-4a39-8751-9e17e9776f22. [Accessed on: 2 Mar 2024]. (2024).

Sun, C. & Wee, W. G. Neighboring gray level dependence matrix for texture classification. Comput. Graph. Image Process. 20(3), 297 (1982).

Deepa, B. & Ramesh, K. Epileptic seizure detection using deep learning through min max scaler normalization. Int. J. Health Sci. https://doi.org/10.53730/ijhs.v6nS1.7801 (2022).

Applied Sciences | Free Full-Text | Enhanced Reinforcement Learning Method Combining One-Hot Encoding-Based Vectors for CNN-Based Alternative High-Level Decisions Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/11/3/1291. [Accessed on: 2 Mar 2024]. (2024).

Raghuwanshi, B. S. & Shukla, S. SMOTE based class-specific extreme learning machine for imbalanced learning. Knowl. Based Syst. 187, 104814 (2020).

Genetic Epidemiology | Human Genetics Journal | Wiley Online Library. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.20297. [Accessed on: 2 Mar 2024]. (2024).

Chen X, Jeong JC. Enhanced recursive feature elimination [Internet]. In: Sixth International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA 2007). 429–35.Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4457268. [Accessed on: 5 Apr 2024]. (2007).

Feature Extraction: Foundations and Applications | SpringerLink. Available from: https://link.springer.com/book/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-35488-8. [Accessed on: 2 Mar 2024]. (2024).

A systematic comparison of statistical methods to detect interactions in exposome-health associations | Environmental Health | Full Text. Available from: https://ehjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0277-6. [Accessed on: 2 Mar 2024]. (2024).

Wold, S., Esbensen, K. & Geladi, P. Principal component analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2(1), 37–52 (1987).

PyCaret — pycaret 3.0.4 documentation. Available from: https://pycaret.readthedocs.io/en/latest/. [Accessed on: 21 Jan 2024]. (2024).

Akiba T, Sano S, Yanase T, Ohta T, Koyama M. Optuna: A Next-generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. In: Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. 2623–31. https://doi.org/10.1145/3292500.3330701. (2019).

Santos CFGD, Papa JP. Avoiding Overfitting: A Survey on Regularization Methods for Convolutional Neural Networks. ACM Comput Surv. 54(10s):213:1–213:25. Available from: https://dl.acm.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.1145/3510413. [Accessed on: 18 Aug 2024]. (2022).

Ng AY. Feature selection, L1 vs. L2 regularization, and rotational invariance [Internet]. In: Proceedings of the twenty-first international conference on Machine learning. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. 78.Available from: https://doi.org/10.1145/1015330.1015435. [Accessed on: 18 Aug 2024]. (2004).

Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. J. Royal Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 58(1), 267–288 (1996).

Urbanowicz, R. J., Olson, R. S., Schmitt, P., Meeker, M. & Moore, J. H. Benchmarking relief-based feature selection methods for bioinformatics data mining. J. Biomed Inform 85, 168–188 (2018).

Suh, C. H., Kim, H. S., Jung, S. C., Choi, C. G. & Kim, S. J. Clinically relevant imaging features for MGMT promoter methylation in multiple glioblastoma studies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 39(8), 1439–1445 (2018).

Han, Y. et al. Structural and advanced imaging in predicting MGMT promoter methylation of primary glioblastoma: a region of interest based analysis. BMC Cancer 18(1), 215 (2018).

Rundle-Thiele, D. et al. Using the apparent diffusion coefficient to identifying MGMT promoter methylation status early in glioblastoma: importance of analytical method. J. Med. Radiat. Sci. 62(2), 92–98 (2015).

Kong, Z. et al. 18F-FDG-PET-based Radiomics signature predicts MGMT promoter methylation status in primary diffuse glioma. Cancer Imaging 19(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-019-0246-0 (2019).

Qian, J. et al. Prediction of MGMT status for glioblastoma patients using radiomics feature extraction from 18F-DOPA-PET imaging. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 108(5), 1339–1346 (2020).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Machines per Million Population. [Accessed on: 18 Aug 2024]. (2024).

Xi, Y. et al. Radiomics signature: A potential biomarker for the prediction of MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 47(5), 1380–1387 (2018).

Ren, J. et al. MRI-based radiomics analysis improves preoperative diagnostic performance for the depth of stromal invasion in patients with early stage cervical cancer. Insights Imaging 13(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-022-01156-0 (2022).

Panagiotou, O. A., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Genome-Wide Significance Project. What should the genome-wide significance threshold be? Empirical replication of borderline genetic associations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 41(1), 273–286 (2012).

Sundus, K. I., Hammo, B. H., Al-Zoubi, M. B. & Al-Omari, A. Solving the multicollinearity problem to improve the stability of machine learning algorithms applied to a fully annotated breast cancer dataset. Inform. Med. Unlocked 33, 101088 (2022).

Cook, J. A. & Ranstam, J. Overfitting. Br. J. Surg. 103(13), 1814. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10244 (2016).

Alzubaidi, L. et al. 2021 Review of deep learning: concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 8(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-021-00444-8 (2021).

Manakitsa, N., Maraslidis, G. S., Moysis, L. & Fragulis, G. F. A review of machine learning and deep learning for object detection, semantic segmentation, and human action recognition in machine and robotic vision. Technologies 12(2), 15 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Felipe Cicci Farinha Restini: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Tarraf Torfeh: Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft. Souha Aouadi: Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft. Rabih Hammoud: Supervision. Noora Al-Hammadi: Supervision. Maria Thereza Mansur Starling: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Cecília Felix Penido Mendes Souza: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Anselmo Mancini: Software. Leticia Hernandes Brito: Methodology. Fernanda Hayashida Yoshimoto: Methodology. Nildevande Firmino Lima-Júnior: Methodology. Marcello Moro Queiroz: Methodology. Ula Lindoso Passos: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources. Camila Trolez Amancio: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources. Jorge Tomio Takahashi: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources. Daniel De Souza Delgado: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources. Samir Abdallah Hanna: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—original draft. Gustavo Nader Marta: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—original draft. Wellington Furtado Pimenta Neves-Junior: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board (IRB) approval number

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was submitted and approved by the Brazilian National Health Council through the Brazil platform (identifier 63591922.6.0000.5461). As the study involved a retrospective analysis of hospital database records, a waiver for obtaining Informed Consent was requested and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Sírio-Libanês Hospital (ref. 5461), which also granted approval for both the research and the waiver of the informed consent form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Restini, F.C.F., Torfeh, T., Aouadi, S. et al. AI tool for predicting MGMT methylation in glioblastoma for clinical decision support in resource limited settings. Sci Rep 14, 27995 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78189-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78189-6