Abstract

To achieve the desired superheat of molten steel during the continuous casting process, optimization of process parameters such as molten steel temperature in ladle furnace, casting speed, and baking temperature is necessary. Therefore, obtaining the superheat corresponding to these process parameters in advance is particularly important. To address this issue, a model for predicting the temperature of molten steel in the tundish during continuous casting is designed. The model adopts a combined modeling approach of mechanistic model and data model. To address the issue of the mechanism model’s inability to capture the variation of the lining’s thermal parameters, this article improves the traditional physics-informed neural network (PINN) algorithm. It combines the constraints from both the forward and inverse problems, allowing for obtaining solutions to the equations while capturing the variation of equation parameters. Actual data from multiple casting sequences at a steel plant are collected to validate the accuracy and interpretability of the model. The results show that the error of the model is about 2.1k which has better accuracy compared to pure mechanistic model and pure data model. Additionally, it can capture the variation patterns of tundish lining thermal parameters under different operating conditions. Therefore, the model designed in this article can provide both profound physical interpretation ability and more practical predictions of molten steel temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Continuous casting is a vital process in steel production, wherein molten steel is continuously cast into various shaped billets. The tundish, which serves as a crucial component in the continuous casting process, regulates the temperature and composition of molten steel as the final stage of metallurgy before solidification. Superheat stands as a core control parameter in the continuous casting process, exerting significant influence on the quality of castings and production processes. To stabilize the superheat of molten steel at predetermined values, optimization of continuous casting process parameters is imperative. Therefore, obtaining the superheat corresponding to each set of process parameters in advance becomes particularly crucial. The magnitude of superheat is equivalent to the difference between the tundish outlet temperature and the melting point temperature of the steel. Consequently, stabilizing superheat effectively entails stabilizing the temperature of the molten steel in the tundish, while predicting superheat essentially involves forecasting the temperature of the molten steel in the tundish.

The methods for establishing a prediction model of the molten steel temperature in the tundish generally fall into two categories: mechanistic models and data models, each with its own characteristics. Mechanistic models, such as the finite element method, are numerical methods based on physical formulas and mathematical models, which can be used to simulate the flow field and temperature field inside the tundish. L. SOWA utilized a mechanistic model to address issues of poor tundish structure1,2. By redesigning the shape and position of the casting pads, weirs, and baffles, they improved the flow field and temperature field within the tundish, thereby enhancing the quality of the castings. S. X. Liu, X. M. Yang and others used mechanistic models to optimize continuous casting process parameters3. By improving the clogging zone and reducing dead zones, they removed fine non-metallic inclusions from the molten steel, thus improving the quality of the castings. These examples demonstrate that constructing mechanistic models can accurately solve physical equations and simulate temperature fields inside the tundish4,5,6. Under certain circumstances, particularly in high-temperature conditions, the physical parameters within the equations may undergo temporal variations, and the precise patterns of these alterations remain unknown. Consequently, the resultant molten steel temperature values are unavoidably impacted. Therefore, accurately simulating the temperature field under such conditions solely through the establishment of mechanistic models is rendered unfeasible7,8.

Another modeling approach is the data model. The term “data model” refers to the process of constructing models using data to describe internal relationships within the data. Common modeling techniques include machine learning algorithms. S. Hore, S. K. Das, and others addressed process optimization issues by constructing data models9. They developed a predictive model for defect occurrence to guide the setting of important process parameters such as casting speed, crystallizer temperature, and crystallizer vibration frequency. S. A. Botnikov, O. S. Khlybov, and others tackled real-time process parameter control issues by constructing data models10. They employed a combination of machine learning and Bayesian networks to establish a predictive model for continuous casting slab cooling temperatures, improving the accuracy of temperature predictions. These examples demonstrate that data models can be applied in the continuous casting process to address issues related to predicting physical variables11,12,13. However, such models have two drawbacks. Firstly, the model structure is simple and lacks interpretability, as it lacks physical formulas as support14,15. Secondly, the accuracy of the model depends on having a sufficient amount of training data, and a limited dataset can negatively impact the model’s accuracy16,17.

To address the limitations of the aforementioned modeling approaches, this article proposes a novel modeling method that combines mechanistic and data models to construct a predictive model for molten steel temperature in the tundish. This model combines the advantages of both traditional modeling methods. Compared to pure mechanistic models, it accounts for changes in thermal property parameters over casting time, enhancing the accuracy of temperature predictions and aligning them more closely with actual values. In contrast to pure data-driven models, this approach offers greater interpretability, providing insight into how predictions are made based on the input variables. To address the issue of limited datasets affecting result accuracy, this article employs a Physics-Informed Neural Network algorithm in the process of building the data model. This algorithm incorporates prior physical knowledge, enabling the data model to generalize better even with limited datasets18,19. Overall, the integration of mechanistic and data models maximizes the compression of the “black box” space, overcomes the issue of limited datasets, and enhances the accuracy and generalization of the model20,21.

Method

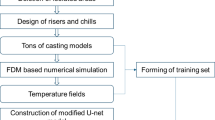

The prediction model of molten steel temperature in the tundish developed in this article is achieved through a combined approach of mechanistic and data modeling. The entire model is divided into two parts: the mechanistic model part and the data model part. The mechanistic model primarily focuses on the heat transfer process of molten steel in the tundish, considering both heat acquisition and loss to obtain the temperature of the molten steel. Meanwhile, the data model focuses on the variation patterns of the temperature field within the working layer, providing time-varying heat loss values to the mechanistic model.

Overall model design

The prediction model for molten steel temperature in the tundish, discussed in this article, is built by combining mechanistic and data-driven approaches, with its construction principle illustrated in Fig. 1. The inputs to the model are the temperature of the molten steel in the ladle furnace, the casting speed, and the tundish preheating temperature, while the output is the temperature of the molten steel in the tundish. The mechanistic model describes the heat absorption and dissipation states of the molten steel as it flows from the ladle furnace into the tundish, demonstrating the mathematical relationship between the temperature of the molten steel in the tundish and the heat dissipation of the lining. The data model describes the process of heat transfer within the working layer, showing the temporal variation patterns of temperature at different positions within the working layer. The two models are connected through heat transfer equations, describing the heat transfer process between the molten steel in the tundish and the working layer of the tundish lining. This demonstrates the mathematical relationship between the heat transfer and the interface between the “molten steel” and “working layer.” This part is the core of the research, not only obtaining the temperature field within the working layer but also capturing the variation patterns of thermal property parameters within the working layer over casting time.

Design of the mechanistic section

This section constitutes the core of the entire model, aiming to determine the main variations and range of the molten steel temperature in the tundish, thereby defining the generalization of the entire model. For the molten steel in the tundish, the main source of heat is from the molten steel in ladle furnace, while the main pathways of heat loss include heat storage in the lining, convective heat transfer at the lining surface, thermal radiation on the molten steel surface, and convective heat transfer through the covering agent22. Overall, heat storage in the lining and convective heat transfer at the lining surface can be combined as heat dissipation through the molten steel passing through the working layer, while thermal radiation on the molten steel surface and convective heat transfer through the covering agent can be combined as heat dissipation through the covering agent. Firstly, according to the law of heat conservation, the entire process can be represented by (1), where Td represents the temperature of the molten steel in ladle furnace, T represents the temperature of the molten steel in tundish, c represents for the specific heat of molten steel, Vd represents the flow rate of the molten steel in ladle furnace, which is the product of the casting speed and the number of flow channels, Mz represents the mass of the tundish molten steel, Q1 represents the heat dissipated through the lining, and Q2 represents the heat dissipated through the covering agent.

The rearrangement of (1) yields (2):

Discretizing (2) leads to (3), establishing the relationship between the temperature of the tundish molten steel and the heat dissipation Q.

First, considering the heat dissipation through the covering agent, the heat exchange process between the molten steel and the covering agent in the tundish was simplified by assuming that the heat dissipation of the covering agent is a constant value. This assumption is justified by the fact that the thickness of the covering agent remains relatively constant and can be manually adjusted. The basis for this assumption lies in the results of multiple numerical simulations, which revealed that the heat dissipation of the covering agent remains nearly unchanged under various operating conditions. Numerical simulations were conducted to test different scenarios, including varying molten steel temperatures, casting speeds, and preheating temperatures. As shown in Fig. 2, the calculated heat transfer indicates a similarity in heat dissipation across different experimental conditions. At the beginning of casting, the significant temperature difference between the covering agent and the molten steel, along with possible phase changes and some chemical reactions, leads to substantial heat loss from the molten steel, which then stabilizes. This finding allowed the heat dissipation of the covering agent to be effectively represented as a constant in the model, thereby simplifying the model’s complexity. This simplification not only improved computational efficiency but also ensured the accuracy and stability of the model in predicting the temperature field of the molten steel.

Next, considering the heat dissipation through the lining, both heat storage and heat transfer within the tundish lining occur simultaneously. The tundish lining is divided into four layers: the working layer, the permanent layer, the insulation layer, and the steel shell23. These four layers consist of different materials, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Since the molten steel comes into direct contact with the working layer, its heat dissipation is directly transferred to this layer, which subsequently transfers the heat to the following layers. Therefore, it is sufficient to consider the heat transfer between the “molten steel” and “working layer” interface, as shown in (4), where S represents the contact area between molten steel and the working layer, λw represents thermal conductivity of the working layer, x represents the position of the working layer, Tw represents the temperature of the working layer.

From (4), it is evident that the heat transfer through the working layer is related to the temperature field within the working layer. Therefore, the next step is to solve for the temperature field within the working layer.

Design of the data model section

This section constitutes the innovative part of the entire model, aiming to provide the heat dissipation through the working layer for the mechanistic model. Firstly, the temperature field within the working layer is obtained by utilizing the Physics-Informed Neural Network algorithm, which determines the accuracy of the entire model. Secondly, by exploring the internal relationships within the data, the variation patterns of thermal property parameters within the working layer are identified, which determines the interpretability of the entire model.

Discussion on thermal property parameters

For this study, the thermal property parameters of the tundish working layer material, namely thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity, undergo changes as the casting process progresses. Firstly, physical erosion occurs due to the continuous scouring of molten steel against the working layer. This results in fluid shear forces and mechanical stresses on the working layer, leading to wear, cracks, or material fatigue, thus affecting its integrity. Consequently, the thickness of the working layer decreases over time, reducing the length of the heat transfer path and increasing the thermal conductivity. Thinner materials facilitate faster heat transfer. As for specific heat capacity, changes in material thickness do not directly affect its magnitude. Decreasing thickness only affects the overall heat capacity, storing less energy. Secondly, high temperatures can lead to thermal expansion, thermal stress, and chemical reactions in the working layer material, affecting both thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity24.

The conditions at the continuous casting site are complex, and the production environment varies for each casting. In addition to the erosion caused by molten steel scouring, there may be other factors influencing the thermal property parameters25,26. However, regardless of the circumstances, the temperature field within the working layer still follows the heat transfer equation, and these influences are ultimately reflected in the thermal property parameters, i.e. thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity.

When considering the changes in thermal property parameters, the number of unknowns in the partial differential equation increases from one temperature (T) to three: temperature (T), thermal conductivity (λ) and specific heat capacity (c). In such cases, using deep learning methods can solve the partial differential equation and capture the trends in thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity changes, making the prediction results closer to actual production conditions.

Solving the partial differential equation for “parameters vary with time " using PINN

According to the continuous casting process, the tundish undergoes high-temperature baking before being put into operation. During this high-temperature baking process27, the four layers of the tundish lining reach a steady-state thermal conduction status. When casting begins and molten steel flows into the tundish, the temperature on the inner side of the lining rapidly increases. At this point, the heat transfer state transitions to non-steady-state conduction. The non-steady-state heat transfer equation describes the relationship between the temperature within the working layer and time and position, as shown in (5). To determine the relationship between temperature and time, this partial differential equation needs to be solved.

There are various methods for solving differential equations, such as Euler’s method and the Runge-Kutta method28. However, these methods perform well in solving simple ordinary differential equations. The temperature field within the working layer to be solved in this article is a partial differential equation (PDE). Many studies utilize finite element methods to solve PDE by establishing mechanistic models29. However, in the topic studied in this article, where the thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity change during the casting process and their patterns are unknown, numerical simulations cannot provide insights into the effects of changes in thermal property parameters on the temperature field.

The one-dimensional unsteady-state heat transfer equation describes the variation of temperature with time along a one-dimensional material. This equation is a PDE that relates the rate of change of temperature with time to the second derivative of temperature with respect to spatial distribution within the material. Among various data-driven techniques for partial differential equations, PINN have shown significant promise and generality30,31,32. Machine learning has been a revolutionary achievement in many scientific disciplines. However, it is often limited in complex physical, biological, or engineering fields due to the difficulty of collecting training data. Achieving high prediction accuracy with a limited training set is a research challenge. PINN is a new class of machine learning techniques where the loss function of the neural network is designed to satisfy both initial and boundary conditions33,34.

For the scenario applied in this article, heat transfer equation, initial conditions, and boundary conditions can be listed:

In these equations, T represents the temperature of the tundish working layer, which is a function of both time t and space x (referring to the position within the thickness of the working layer). λ is the thermal conductivity of the working layer material, and c is its specific heat capacity. Ttundish is the temperature of molten steel in the tundish, Tair is the temperature of the surrounding air (i.e., room temperature), and h is the convective heat transfer coefficient. Table 1 presents the physical property parameters of the materials used in this study.

The so-called PINN model integrates physics equations as constraints into neural networks to ensure that the training results comply with physical laws. It involves adding the difference between the iterations of physics equations to the neural network’s loss function, allowing the physics equations to “participate” in the training process. Traditional PINN can solve partial differential equations by using initial conditions, boundary conditions, and the equations themselves as loss functions. However, the PDE solved in this study differ from the traditional form as they evolve from a single unknown variable T to three unknown variables: T, λ, and c. Therefore, the previously “positive definite” PDE become “under-determined” PDE. Consequently, additional data terms are added to the loss function to ensure unique solutions for the equations.

Figure 4 illustrates the PINN framework consisting of two networks. The first part of the framework is the neural network NN (w, b), which takes position x and time t as inputs and outputs temperature T, thermal conductivity λ, and specific heat capacity c. Subsequently, the output of the NN is then sent to the next two networks, NN_PDE and NN_DATA, which essentially use the initial and boundary conditions of the PDE to evaluate the residual of the PDE, and the difference between the real data and the predicted data to evaluate the accuracy of the model35,36. During the training iterations, the neural network optimizes not only its own loss function but also the difference in each iteration of the physics equations, ensuring that the final trained results satisfy physical laws.

Construction of PINN loss function

PINN approximates the mapping between points in the space-time domain as solutions to PDEs. The parameters of the neural network are randomly initialized and updated iteratively by minimizing the loss function that enforces the PDE. The loss function of the PINN model in this study consists of four error components: (a) initial condition term, (b) boundary condition term, (c) PDE term, and (d) data term, used for neural network prediction. The three components of the PINN loss function are as follows:

(a) Mean square error of initial conditions:

Here, T, λ, and c represent the neural network outputs at a certain position x and t = 0. T0, λ0, and c0 represent the initial conditions at this space-time point.

(b) Mean square error of boundary conditions:

Here, Fl and Fu represent the boundary conditions at x = 0 and x = δ positions, respectively. Bl and Bu represent the residuals when the neural network outputs at x = 0 and x = δ are plugged into the boundary conditions.

(c) Mean square error of PDE equation:

Here, F represents the heat transfer equation at a certain position x and time t. R represents the residual when the neural network outputs at this space-time point are plugged into the heat transfer equation.

(d) Mean square error of data:

Here, F represents the temperature of the molten steel in the tundish at a certain time t, The calculation process of this temperature is to first calculate the temperature of the working layer at x = 0, then calculate the heat of the molten steel through the working layer, and finally calculate the temperature of the molten steel at this time. D represents the residual between the model-predicted molten steel temperature at this time and the actual molten steel temperature.

The overall loss function in this study is formulated as:

Table 2 shows the pseudocode of the PINN algorithm application in this study, focusing on the composition of the loss function and how the physical equations are incorporated into the loss.

Experiments and results

To validate the effectiveness of the model, as a comparative experiment, this study also established pure mechanistic models and pure data models. Based on the research content of this article, a mechanistic model can be established using Fluent software, and the schematic diagram of this model is shown in Fig. 5. Through steps such as physical modeling, mesh partitioning, equation selection, condition application, and solution analysis, the control equations for the flow field and temperature field in tundish are solved. The control equations include continuity equations, N-S equations, turbulence model equations, energy equations, and boundary condition equations. The molten steel temperature in ladle furnace, casting speed, and baking temperature in tundish are the input conditions for the model.

Additionally, a data model is established in this study, as depicted in Fig. 6. The model takes the molten steel temperature in ladle furnace, casting speed, and baking temperature in tundish as inputs and predicts the molten steel temperature in the tundish as output. Employing deep learning techniques, the traditional neural network (NN) model regresses the relationship between inputs and outputs. Numerical values reflecting the variation of the molten steel temperature in the tundish collected from the field are utilized as training data. As the information about the thermal properties of the working layer material changes with casting time, it is inherently included in these training data. Therefore, after training the model, the regression results also encompass this information. The model consists of 3 input neurons, 4 hidden layers with 64 neurons in each layer, and 1 output neuron. The hidden layers use the ReLU activation function, while the output layer employs a linear activation function. The loss function is the mean squared error, and the optimizer selected is Adam. With a learning rate of 0.1 and a batch size of 32, combined with early stopping and validation set monitoring, the model ensured convergence and prevention of overfitting. After hyperparameter tuning through cross-validation, the final model demonstrated good predictive performance on the test set.

Validating model accuracy

Experimental details

Four sets of experiments are conducted, as shown in Table 3. Using the input values from Experiment 1 as the baseline, experiments are designed using the method of controlling variables. In Experiment 2, the molten steel outflow velocity and baking temperature remain consistent with Experiment 1, but the overall temperature is approximately 10 K higher. Experiment 3 maintains the molten steel temperature in ladle furnace and baking temperature as Experiment 1, but doubles the steel outflow velocity. Experiment 4 maintains the molten steel temperature in ladle furnace and casting speed as Experiment 1, while increasing baking temperature by nearly 100 K.

The pure mechanistic model was developed using Fluent software. This experiment simulated a 15-ton T-type tundish from a steel plant. The dimensions of the tundish are approximately 6020 mm × 900 mm at the top and 5940 mm × 450 mm at the bottom, with a height of about 1100 mm and a nozzle height of approximately 500 mm. This study replicated the tundish on a 1:1 scale according to its original dimensions. Given the axial symmetry of the tundish’s geometric structure, the three-dimensional model was simplified into a two-dimensional model to streamline calculations and enhance simulation efficiency. The two-dimensional section selected for numerical simulation lies along the straight line formed by the centerlines of the nozzles, and the computational domain is defined by the intersection of this vertical section with the tundish structure. This section sufficiently represents the characteristics of the flow and temperature fields within the tundish, allowing for a significant reduction in computational load while maintaining the accuracy and reliability of the results. To ensure the accuracy of the numerical simulation, a high-quality mesh was used in the model. Specifically, an unstructured quadrilateral mesh was employed to better capture the details of the complex geometry and boundary layers. Mesh refinement was applied in critical areas such as near the nozzles and along the tundish walls. The final mesh consisted of 13,798 elements, with a minimum cell area of 5.13e-4 m² and a maximum cell area of 8.41e-4 m², achieving an optimal balance between computational efficiency and result precision.

In the transient simulation conducted in this study, an independence analysis was performed to ensure the accuracy of the results and the independence from selected parameters. The analysis primarily focused on the following parameters: time step, mesh resolution, and turbulence model. First, the independence of the time step was validated. By selecting different time steps and observing the variations in key variables such as molten steel temperature and velocity during the simulation, it was found that when the time step was reduced to 1 s, the changes in transient responses stabilized, and further reduction had a negligible effect on the results. Thus, a time step of 1 s was chosen to ensure the temporal accuracy of the simulation. Second, mesh resolution was tested by gradually refining the mesh. As the mesh density increased, we monitored the changes in the transient simulation results, and it was observed that when the mesh density reached 13,798 elements, the results no longer exhibited significant changes, indicating minimal dependence on mesh density. Additionally, independence analyses were conducted on the turbulence model and boundary conditions. By switching between different turbulence models, from k-ε to k-ω, it was observed that these secondary parameters had little impact on the simulation results. In summary, through the independence analyses of time step, mesh resolution, and turbulence model, we have verified the independence of the simulation results from these parameters, ensuring the accuracy and stability of the transient numerical simulation.

Table 4 shows the key parameters of the numerical simulation process. The inlet boundary conditions were defined, where the inlet velocity can be calculated using the casting speed, and the inlet temperature is one of the model inputs. The initial boundary conditions for the working layer were defined, where the initial temperature is the temperature before the tundish is put into operation. The Fluent software’s coupled method solver was selected for transient solution of the convection-temperature coupling field, with a time step of 1 s. The total calculation time for one casting was 21,000 s.

Under the input conditions of molten steel temperature in ladle furnace ranging from 1828 K to 1810 K, casting speed of 3 m/min, and tundish working layer baking temperature of 1255 K, the flow field and temperature field inside the tundish are being solved using the finite element method. Figure 7 shows the temperature contour maps of the steel and the tundish walls at different time points under these input conditions.

Temperature contour of the tundish at different time points within one casting. (a) At t = 1200s, the temperature contour plot of molten steel and lining in the tundish. (b) At t = 1200s, the temperature contour plot of molten steel in the tundish. (c) At t = 10500s, the temperature contour plot of molten steel and lining in the tundish. (d) At t = 10500s, the temperature contour plot of molten steel in the tundish. (e) At t = 21000s, the temperature contour plot of molten steel and lining in the tundish. (f) At t = 21000s, the temperature contour plot of the molten steel in the tundish.

As the casting process progresses and the amount of heat rises, the erosion and corrosion of the working lining in the tundish become increasingly severe, which significantly impacts the heat transfer between the molten steel and the working lining. Therefore, this study conducted predictive experiments for ten heats within a single casting sequence. Each ladle lasts approximately 35 min, with a calculation interval of 1 s, resulting in around 21,000 sets of predictive data per casting sequence. The input data for the model, as well as the actual measured data, were obtained using a blackbody cavity temperature measurement system developed by Professor Zhi Xie and his team. This system employs a contact measurement method, with the probe located between the two side outlet nozzles, approximately 0.5 m below the molten steel surface. If the coordinate system is established with the center of the middle outlet nozzle on the bottom surface of the tundish as the origin, then the coordinates of the measuring point are (1800, 0, 600). The system has a sampling interval of 1 s and can collect a total of 21,000 data sets. This system is capable of accurately measuring molten steel temperatures, providing high-quality experimental data. In addition to collecting the tundish molten steel temperature data for one casting sequence, the research also records the molten steel temperature in ladle furnace, casting speed, and baking temperature of the tundish at the same time. Given the wide range of values in the input data, normalization techniques were used to ensure the accuracy of the prediction results. The “Min-Max” normalization method was chosen for this purpose.

This experiment utilized an Apple MacBook Pro computer equipped for the training process. The computer features an M1 chip with an ARM architecture, consisting of an 8-core CPU and GPU, along with 16 GB of memory. This device effectively handles large-scale neural network training tasks, ensuring efficient model training. In this article, Xavier initialization was used for setting the model’s weights to ensure consistent variance between inputs and outputs, avoiding gradient issues. The ReLU activation function was chosen for its computational efficiency and ability to mitigate the vanishing gradient problem. The Adam optimizer was used, leveraging its advantages of momentum and adaptive learning rate, which accelerated model convergence and improved training stability. Table 5 shows the hyperparameters, training time and loss value of four experimental neural network models.

Experimental results

Figure 8 present the results of the three models predicting the continuous temperature of molten steel in the tundish under four experimental conditions. It is evident from the results that the proposed method yields values closer to the actual values. Through calculations, it is determined that the relative errors obtained by the pure mechanistic model for the four experiments are 0.144%, 0.143%, 0.079%, and 0.131%, respectively. The relative errors obtained by the pure data-driven model for the four experiments are 0.154%, 0.152%, 0.126%, and 0.160%, respectively. In contrast, the combined mechanistic and data-driven model proposed in this article yields relative errors of 0.139%, 0.142%, 0.061%, and 0.116% for the four experiments, respectively.

Table 6 shows the different accuracies under different modeling approaches. The average relative error of the mechanism model is 0.124%, the average relative error of the data model is 0.148%, and the average relative error of the combined mechanism and data model is 0.114%. Through comparison, it can be observed that the proposed model in this article has a higher accuracy, surpassing both the pure mechanism model and the pure data model in terms of accuracy.

Validating model generalization and interpretability

Experimental details

The experimental design approach is consistent with that used to validate model accuracy, with changes made to the model inputs, namely molten steel temperature in ladle furnace, casting speed, and baking temperature. The aim is to observe the variation of thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity over casting time. Due to variations in the effectiveness of repair work on the tundish working layer by workers, the numerical values of thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity cannot remain consistent for each casting, but their variation patterns should. This enables the determination of the model’s generalization based on the variation patterns observed in each experiment. Furthermore, the physical laws can be used to interpret the variation patterns of these thermal properties, thereby determining the model’s interpretability.

Experimental results

The following figures illustrate the variation patterns of the working layer’s thermal properties over time for the four aforementioned experiments. Figure 9a represents the variation pattern of thermal conductivity, while Fig. 9b depicts the variation pattern of specific heat capacity. It is evident from the figures that, despite continuous changes in input conditions, the variation patterns of thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity remain largely consistent. This allows us to conclude that the model proposed in this article exhibits good generalization.

From Fig. 9, it can be observed that the variation trend of thermal diffusivity and thermal conductivity remains consistent, while the specific heat capacity remains almost unchanged. Generally, with increasing temperature, the thermal diffusivity of a material tends to increase. This is because at higher temperatures, molecules and atoms in the material have higher kinetic energy, leading to more vigorous thermal motion and thus increasing thermal diffusion properties. As for specific heat capacity, it is an intrinsic property of a substance and does not vary with temperature due to the interactions between molecules and atoms, absorbing and releasing energy in a relatively constant manner even with temperature changes. Analyzing the results of thermal conductivity, within one casting cycle, the variation trend can be divided into three stages. First is the rising trend from 0 to 3000 s, attributed to the rapid increase in the temperature of the working layer due to its contact with the high-temperature steel flow, resulting in a rapid increase in thermal conductivity. Then, from 3000 to 6000 s, there is a declining trend as the temperature of the working layer stabilizes under the influence of the high-temperature steel flow, leading to a decrease in thermal conductivity. Finally, from 6000 s to the end of the casting cycle, there is a rising trend due to the continuous erosion of the working layer by the steel flow, which damages the physical structure, reducing the length of the heat transfer path and consequently increasing the thermal conductivity. This analysis confirms the interpretability of the model proposed in this article.

Investigating the impact of model input variables on results

Experimental details

Firstly, the effect of molten steel temperature in ladle furnace on the molten steel temperature the tundish will be explored. Using 1828 K ~ 1810 K as the baseline, the input temperature will be varied at intervals of 2 K, while casting speed and baking temperature remain constant. Six sets of experiments will be conducted. Secondly, the influence of casting speed on the molten steel temperature in tundish will be investigated. Using 3 m/min as the baseline, the casting speed will be varied at intervals of 0.6 m/min, while molten steel temperature in ladle furnace and baking temperature remains constant. Six sets of experiments will be conducted. Lastly, the impact of baking temperature on the molten steel temperature in tundish will be examined. Using 1175 K as the baseline, the baking temperature will be varied at intervals of 20 K, while molten steel temperature in ladle furnace and casting speed remains constant. Six sets of experiments will be conducted. The experimental procedure is outlined in Table 7.

Impact of molten steel temperature in ladle furnace on molten steel temperature in tundish

This study investigates the effect of molten steel temperature in ladle furnace on molten steel temperature in tundish through six sets of experiments. The molten steel temperature in ladle furnace is incrementally increased as input, and the resulting molten steel temperature in tundish is depicted in Fig. 10a. As observed from the curves, the molten steel temperature in tundish gradually rises with the increase in molten steel temperature in ladle furnace. Figure 10b quantifies the temperature increase of the molten steel in ladle furnace. The differences between adjacent curves are calculated to determine the change in temperature at the same time point under different experimental conditions. The average of these differences serves as a quantification indicator for the effect of molten steel temperature in ladle furnace on molten steel temperature in tundish. According to the experimental results, for every 2 K increase in the molten steel temperature in ladle furnace, the molten steel temperature in tundish rises by approximately 2 K.

The result of the model outputs under different molten steel temperature in ladle furnace conditions. (a) Continuous values of molten steel temperature in tundish under different molten steel temperature in ladle furnace conditions. (b) Temperature difference at the same time point among different experiments under different molten steel temperature in ladle furnace conditions.

Impact of casting speed on molten steel temperature in tundish

This study investigates the impact of casting speed on the tundish through six experiments. The casting speed is gradually increased as the input variable, while the output variable is the molten steel temperature in tundish, as shown in Fig. 11a. It can be observed from the curves that with the increase in casting speed, the tundish steel temperature also gradually rises. Figure 11b quantifies the temperature increase in the tundish due to casting speed. The temperature difference between adjacent curves is calculated to determine the effect of casting speed on the molten steel temperature in tundish at the same time point. The average of these differences serves as a quantitative indicator of the impact of casting speed on the molten steel temperature in tundish. According to the experimental results, the increase in casting speed by 0.6 m/min does not lead to a fixed increase in molten steel temperature in tundish but rather results in a range of 0.36 K to 1.76 K. This variation pattern is related to the casting speed and the duration of molten steel flow in ladle furnace.

Impact of Baking temperature on molten steel temperature in tundish

This study investigates the impact of baking temperature on the tundish through six sets of experiments. The baking temperature is incrementally increased as input, and the resulting molten steel temperature in tundish is observed. As shown in Fig. 12a, the molten steel temperature in tundish gradually rises with the increase in baking temperature. To quantify the increase in steel temperature, the differences between adjacent curves are calculated, as depicted in Fig. 12b. These differences at the same time points among different experimental conditions are averaged to quantify the influence of baking temperature on the molten steel temperature in tundish. According to the experimental results, for every 20 K increase in baking temperature before the tundish is put into operation, the molten steel temperature in tundish during the entire casting process will rise by approximately 1 K.

The result of the model outputs under different baking temperature conditions. (a) Continuous values of molten steel temperature in tundish under different baking temperature conditions. (b) Temperature difference at the same time point among different experiments under different baking temperature conditions.

Conclusion

This article proposes a model based on the combination of mechanism model and data model to predict the temperature of molten steel in tundish in continuous casting. There are two main innovations in this study. Firstly, the model is established by integrating mechanism and data models, ensuring both the accuracy of the data model and the interpretability of the mechanism model. Secondly, in solving the time-varying partial differential equations for parameter estimation, the loss function terms of the Physics-Informed Neural Network algorithm are improved to capture the influence of thermal parameter changes on the results, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the model. With the actual conditions of a steel plant as experimental conditions and field data as experimental data, the experimental results show that the proposed model improves the accuracy of prediction compared to traditional mechanism and data models. Additionally, by capturing the time-varying patterns of thermal parameters, the results demonstrate that the proposed model exhibits good generalization and interpretability even with limited training samples. In summary, the molten steel temperature prediction model constructed in this study provides accurate and reliable support for subsequent optimization of process parameters.

Data availability

Since the data in this article will be used in subsequent studies, the data are not publicly available. However, it may be obtained from the first author (dbw089019@163.com) at his reasonable request.

References

Sowa, L. Effect of steel flow control devices on flow and temperature field in the tundish of continuous casting machine. Arch. Metall. Mater. 60, 843–847 (2015).

Panghal, S. & Kumar, M. Optimization free neural network approach for solving ordinary and partial differential equations. Eng. Comput. 37, 2989–3002 (2021).

Liu, S. X., Yang, X. M., Du, L., Li, L. & Liu, C. Z. Hydrodynamic and mathematical simulations of flow field and temperature profile in an asymmetrical T-type single-strand continuous casting tundish. ISIJ Int. 48, 1712–1721 (2008).

Zhou, J. A. et al. Heat transfer of steel in a slab tundish with vacuum chamber. ISIJ Int. 57, 1037–1044 (2017).

Yu, S. et al. Effect of the strand corner structure on the corner stress during the bending and straightening processes in slab continuous casting. J. Manuf. Processes 48, 270–282 (2019).

He, F., Zhang, L. Y. & Xu, Q. Y. Optimization of flow control devices for a T-type five-strand billet caster tundish: water modeling and numerical simulation. China Foundry 13, 166–175 (2016).

Ramírez-López, A., Aguilar-López, R., Kunold-Bello, A., González-Trejo, J. & Palomar-Pardavé, M. Simulation factors of steel continuous casting. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 17, 267–275 (2010).

Zhang, Q. Y. & Wang, X. H. Numerical simulation of influence of casting speed variation on surface fluctuation of molten steel in mold. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 17, 15–19 (2010).

Hore, S., Das, S. K., Humane, M. M. & Peethala, A. K. Neural network modelling to characterize steel continuous casting process parameters and prediction of casting defects. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 72, 3015–3025 (2019).

Botnikov, S. A., Khlybov, O. S. & Kostychev, A. N. Development of the metal temperature prediction model for steel-pouring and tundish ladles used at the casting and rolling complex. Metallurgist 63, 792–803 (2019).

Laghi, L., Schiassi, E., De Florio, M., Furfaro, R. & Mostacci, D. Physics-informed neural networks for 1-D steady-state diffusion-advection-reaction equations. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 197, 2373–2403 (2023).

Gong, R. H. & Tang, Z. Q. Further investigation of convolutional neural networks applied in computational electromagnetism under physics-informed consideration. IET Electr. Power Appl. 16, 653–674 (2022).

He, F., He, D. F., Xu, A. J., Wang, H. B. & Tian, N. Y. Hybrid model of molten steel temperature prediction based on ladle heat status and artificial neural network. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 21, 181–190 (2014).

Gupta, V. K., Jha, P. K. & Jain, P. K. A novel approach to predict the inclusion removal in a billet caster mold with the use of electromagnetic stirrer. J. Manuf. Processes 83, 27–39 (2022).

Li, C. K., Wang, J. X., Dai, Y. & Shi, Y. Experimental validation of saliency maps for understanding deep neural networks for weld penetration prediction. J. Manuf. Processes 88, 22–33 (2023).

Yuan, L., Ni, Y. Q., Deng, X. Y. & Hao, S. A-PINN: auxiliary physics informed neural networks for forward and inverse problems of nonlinear integro-differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 462 (2022).

Wang, L., Liu, G. Y., Wang, G. L. & Zhang, K. M-PINN: a mesh-based physics-informed neural network for linear elastic problems in solid mechanics. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 125 (2024).

Babaei, M. R., Stone, R., Knotts, T. A. & Hedengren, J. Physics-informed neural networks with group contribution methods. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 4163–4171 (2023).

Xu, P. F., Han, C. B., Cheng, H. X., Cheng, C. & Ge, T. A physics-informed neural network for the prediction of unmanned surface vehicle dynamics. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10 (2022).

Leung, W. T., Lin, G. & Zhang, Z. C. NH-PINN: neural homogenization-based physics-informed neural network for multiscale problems. J. Comput. Phys. 470 (2022).

Yao, Y. Z., Guo, J. W. & Gu, T. X. A deep learning method for multi-material diffusion problems based on physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 417 (2023).

Roman, M. et al. Temperature monitoring in the refractory lining of a continuous casting tundish using dstributed optical fiber sensors. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72 (2023).

Ahmed, Y. M. Z., Ewais, E. M. & Zaki, Z. I. Production of porous silica by the combustion of rice husk ash for tundish lining. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing 15, 307–313 (2008).

Das, R. C., Fouzdar, S., Chatterjee, U. K. & Pal, A. R. Study on wear phenomena of tundish working lining by slags of billet caster. Trans. Indian Ceram. Soc. 66, 193–202 (2007).

Mantovani, M. C. et al. Interaction between molten steel and different kinds of MgO based tundish linings. Ironmak. Steelmak. 40, 319–325 (2013).

Pal, S., Behera, K. K., Padhee, P. R., Sarkar, S. & Halder, C. Optimization between Tundish temperature and slab exit temperature to eliminate strand Stuck-Up phenomenon in continuous casting process of steel by implementation of multi-objective evolutionary and genetic algorithm. Steel Res. Int. 90 (2019).

Arzani, A., Cassel, K. W. & D’Souza, R. M. Theory-guided physics-informed neural networks for boundary layer problems with singular perturbation. J. Comput. Phys. 473 (2023).

Zhang, W. B. & Gu, W. Parameter estimation for several types of linear partial differential equations based on gaussian processes. Fractal Fract. 6 (2022).

Yang, X. F., Liu, Y. X. & Bai, S. A numerical solution of second-order linear partial differential equations by differential transform. Appl. Math. Comput. 173, 792–802 (2006).

Zhang, Y. J., Wang, M., Zhang, F. W. & Chen, Z. R. A solution method for differential equations based on Taylor PINN. IEEE Access 11, 145020–145030 (2023).

Tang, S. P., Feng, X. L., Wu, W. & Xu, H. Physics-informed neural networks combined with polynomial interpolation to solve nonlinear partial differential equations. Comput. Math. Appl. 132, 48–62 (2023).

Guo, Y. A., Cao, X. Q., Liu, B. N. & Gao, M. Solving partial differential equations using deep learning and physical constraints. Appl. Sci. Basel 10 (2020).

Sun, K. & Feng, X. L. A second-order network structure based on gradient-enhanced physics-informed neural networks for solving parabolic partial differential equations. Entropy 25 (2023).

Zhang, C. & Shafieezadeh, A. Simulation-free reliability analysis with active learning and physics-informed neural network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 226 (2022).

Zhang, Z. Y., Zhang, H., Liu, Y., Li, J. Y. & Liu, C. B. Generalized conditional symmetry enhanced physics-informed neural network and application to the forward and inverse problems of nonlinear diffusion equations. Chaos Solitons Fractals 168 (2023).

Zhong, L. L., Wu, B. Y. & Wang, Y. F. Low-temperature plasma simulation based on physics-informed neural networks: frameworks and preliminary applications. Phys. Fluids 34 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bowen Dong: Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Writing –original draft. Wu Lv: Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Project administration, Writing - Review & Editing. Zhi Xie: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, B., Lv, W. & Xie, Z. Research on temperature prediction model of molten steel of tundish in continuous casting. Sci Rep 14, 27428 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78611-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78611-z