Abstract

Addressing abdominal obesity requires multifaceted strategies, with physical activity and diet playing a pivotal role. The objective of this study was to assess alterations in body composition, adipokine concentrations, insulin resistance parameters, and lipid metabolism in males with abdominal obesity following two distinct interventions: exercise alone and exercise combined with a specific diet. The study involved 44 males with abdominal obesity (average age 34.7 ± 5.5 years, waist circumference [WC] 110.3 ± 8.5), randomly assigned to three groups: an experimental group with aerobic-resistance exercise (EG, n = 16), an experimental group with aerobic-resistance exercise combined with a high-protein, low-glycemic index carbohydrate diet (EDG, n = 16), both interventions lasting 6 weeks, and a control group without interventions (CG, n = 12). Body composition (body mass [BM], body fat percentage [BF%], fat-free mass [FFM], android body fat percentage [ANDR]), as well as biochemical blood analyses (asprosin [ASP], leptin [LEP], quantitative insulin sensitivity check index [QUICKI], and total cholesterol [TC]), were conducted at baseline and after 6 weeks of intervention. The impact of interventions on the analyzed variables among groups was assessed using mixed ANOVA tests with post-hoc comparisons. Effect size (ES) was also evaluated using 𝜂p2. Significant reductions in ASP concentration after intervention were observed in both EG (p = 0.04) and EDG (p = 0.01). However, post-hoc tests revealed a decrease in LEP only in the EDG group (p < 0.01). In EDG substantial decreases after 6 weeks of intervention were noted in BM (p < 0.01), BF% (p < 0.01), ANDR (p < 0.01) and TC (p < 0.01). The most notable increase in FFM was observed in the EDG group (p < 0.01). More favourable metabolic outcomes were confirmed in the group combining diet with exercise, where there was a notable reduction in ASP levels by 16% and LEP by 48% after 6 weeks of intervention, compared to the group undergoing exercise alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity often results from an excess of energy intake relative to energy expenditure. A primary factor in the development of obesity is overeating, which is often a consequence of disturbances in neurohormonal communication within the body1,2. With the accumulation of adipose tissue, there is an increase in the production of pro-inflammatory adipokines and a decrease in anti-inflammatory ones3. Adipokines responsible, among other functions, for the regulation of satiety include leptin (LEP) and asprosin (ASP)4. With the progression of obesity, LEP resistance is enhanced and levels of LEP and ASP in the bloodstream are elevated5.

LEP, primarily synthesized by adipose tissue but also by other tissues, including the stomach, is a hormone responsible for long-term energy homeostasis in the body6. It crosses the blood-brain barrier, binding to its receptor in the hypothalamus, signaling a feeling of satiety, and reducing hunger and food intake7,8,9. LEP synthesized by gastric cells is associated with short-term satiety, interacting, among others, with cholecystokinin, thereby increasing its production and limiting food intake10. When the adipose tissue level in the human body is low or food availability is restricted, LEP levels decrease, thereby increasing food intake to maintain a normal body weight7.

With the development of adipose tissue, disruptions in LEP signaling occur. Despite its high levels in the blood, the information conveyed by LEP, indicating the cessation of excessive food consumption, is not properly interpreted in the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus becomes increasingly insensitive to LEP with the progression of obesity, leading to hyperleptinemia, which is termed LEP resistance11.

ASP is a novel adipokine responsible for the regulation of appetite, among other functions. ASP has been observed to cross the blood-brain barrier, activating the Agouti-related protein (AgRP+)12. Among obese individuals, the concentration of ASP is higher than in individuals with normal body weight13,14,15 and its level is proportional to the degree of obesity, increasing even fourfold in individuals with a BMI above 40 kg/m216,17. Elevated concentrations of ASP may induce increased feelings of hunger, leading to greater food intake and, consequently, the development of obesity14. One of the primary goals of interventions to improve the health status of individuals with obesity and metabolic syndrome (MetS) is to reduce LEP resistance18and normalize the levels of LEP and ASP in the blood5,19.

The current direction of pharmacological treatment for obesity involves selecting medications based on the phenotypes associated with obesity: hungry brain (abnormal satiation), emotional hunger (hedonic eating), hungry gut (abnormal satiety), and slow burn (decreased metabolic rate)20. Current trends highlight the need to balance the effects of individual dietary components and the impact of health training to address the deficits resulting from obesity.

Resistance training is associated with a significant decrease in both ASP21and LEP22in the blood, primarily through a reduction in adipose tissue levels in the group of obese men leading a sedentary lifestyle. Additionally, the application of high-intensity training leads to a decrease in hunger and an increase in satiety levels by influencing an increase in glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)23and a decrease in ghrelin levels24.

Protein, through high dietary thermogenesis, can increase energy expenditure associated with slow burn and, by influencing the satiety process, appease the hungry brain area25. Moreover, the consumption of a high-protein meal mobilizes the chief cells of the stomach to increase the production of pepsin, which along with leptin, inhibits food intake and stomach emptying6. The use of low-glycemic index carbohydrates26, characterized by high fiber content27, influences prolonged feelings of satiety28limiting the consequences of hungry gut in obesity. Qualitative changes in the diet lead to increased feelings of satiety and reduced hunger, ultimately resulting in an unconscious attainment of a negative energy balance. Maintaining a negative energy balance, resulting from the applied diet and exercise, leads to a reduction in adipose tissue levels and LEP, offering perspectives for reducing LEP resistance7. The implementation of a diet combined with exercise also leads to a decrease in ASP levels29. Through interventions aimed at improving the levels of these described adipokines, the likelihood of achieving lasting results in weight reduction, improving health status, and preventing obesity relapses increases7.

Given the favourable impact of strength training and the described diet on LEP and ASP levels, as well as the hunger and satiety processes, the present study compares the benefits of combining a diet with health training versus the use of health training alone on changes in selected adipokines, body composition, cholesterol levels, and the insulin resistance index. It was hypothesized that an intervention combining the influence of exercise and diet will have a more marked effect on metabolic parameters in men with abdominal obesity compared to a exercise-only intervention.

Results

According to the project assumptions, both intervention groups: the aerobic-resistance group (EG) and the aerobic-resistance combined with a high-protein, low-glycemic index carbohydrate diet group (EDG) showed an increase in training loads measured as the sum of 1RM (one-repetition maximum) from three exercises: squat, bench press, and bar pull-down after six weeks of intervention (p = 0.01) (Table 1). In addition, estimated total energy expenditure (TEE) increased significantly in both intervention groups (p < 0.01). Before the intervention, no significant differences were found between the groups in the analyzed parameters.

The two-way mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated a significant time (p < 0.01) and interaction (p < 0.01) effect for body mass (BM). A significant reduction in BM occurred in the EDG group (p < 0.01), a mean decline of 3.92 kg over the course of 6 weeks (Table 2).

Significant changes in percentage of body fat (p < 0.01) and visceral fat (ANDR, p < 0.01) were confirmed in relation to intervention time and the interaction of time and intervention (BF%, p < 0.01; ANDR, p < 0.01), indicating a medium effect size (𝜂p2 = 0.06). Significant decrease in BF% were confirmed in the EDG group (p < 0.01) between observations, amounting to 4%. Differences were observed between CG and EDG (p = 0.01) in visceral fat (ANDR) with a decrease of 6% in the EDG group over 6 weeks (p < 0.01). An increase in %FFM was also noted in the intervention groups, with the largest increase of 2.9% in the EDG group (p < 0.01). Before the intervention, no significant differences were found between the groups in the analyzed parameters.

The two-way mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated a significant time effect on asprosin (ASP) concentration (p = 0.01). The change in ASP concentration after 6 weeks was confirmed in both EG (p = 0.04) and EDG (p = 0.01) (Table 3; Fig. 1).

Significant differences were confirmed in leptin (LEP) in both intervention time (p = 0.01) and the interaction of time and intervention type (p < 0.01). Post-hoc tests confirmed a 48% decrease in LEP in the EDG group (p < 0.01) (Table 3; Fig. 2).

The QUICKI level increased over time (p = 0.02) in both intervention groups, EG (p = 0.01) and EDG (p = 0.03) (Table 3). Total cholesterol (TC) decreased over the six weeks (p = 0.01) in the intervention groups, achieving statistical significance in the EDG group (p < 0.01). The interaction between time and intervention type was also significant (p < 0.01) (Table 3). Before the intervention, no significant differences were found between the groups in the analysed parameters.

The energy value of the diet also changed over time (p = 0.03), and the interaction between intervention type and time was significant (p < 0.01) and associated with a high effect size (𝜂p2 = 0.15). Participants in the EDG group consumed significantly less energy in the diet after 6 weeks (p < 0.01) (Table 4).

The change in protein levels over time (p = 0.03) and the interaction of time and intervention (p < 0.01) were confirmed, supported by a medium effect size (𝜂p2 = 0.12). The EDG group increased in protein intake during the intervention (p < 0.01) (Table 4).

Carbohydrate consumption changed over time (p = 0.04), depending on the group, and the interaction of time and intervention type was significant (p < 0.01) with a medium effect size (𝜂p2 = 0.13). The EDG group significantly reduced carbohydrate consumption (p < 0.01).

The change in fiber consumption was opposite to that of carbohydrates. Similarly, time (p < 0.01) and interaction between time and intervention (p < 0.01) were significant, with a 46% increase in fiber consumption in the EDG group (p < 0.01).

The level of fats in the diet also changed considering the interaction of time and group (p < 0.01) with a high effect size (𝜂p2 = 0.19). Participants in the EDG group reduced fat consumption by 29% (p < 0.01) (Table 4). Before the intervention, no significant differences were found between the groups in the analysed parameters.

Correlations between components of body composition and adipokines, total cholesterol and QUICKI are summarized in Table 5. Overall, correlations were generally in the moderate range and overlapped for the CG, ED and EDG groups.

Correlations between components of diet and adipokines, total cholesterol and QUICKI are summarized in Table 6. Overall, correlations were generally in the moderate range and overlapped for the CG, ED and EDG groups.

Discussion

The introduction of a combination of exercise and diet (EDG) yielded favorable changes in body composition after 6 weeks of intervention, specifically decreases in BM (−3.9 kg), BF (−4.0%) and ANDR (−6.0%), and an increase in FFM (2.9%). Similarly, participation in exercise alone (EG) resulted in similar changes in body composition, although the changes were not statistically significant and the changes were 4–6 times smaller than those in the EDG group. All changes in body composition in the CG group were also not significant.

The application of exercise alone (EG) resulted in a 14% reduction in ASP and a 10% reduction in LEP concentrations (although not statistically significant), while more favourable outcomes were observed in the EDG group which experienced a 16% reduction in ASP and a 48% reduction in LEP concentrations after the 6 week intervention. Both intervention groups also showed an increase in the QUICKI index, suggesting an improvement in insulin sensitivity. On the other hand, a mean reduction of 11% in TC level in the EDG group was also confirmed after the 6 week intervention. Increased dietary fiber content was negatively correlated with both TC and ASP levels.

The attainment of favorable results in the EDG group, which increased differences relative to the EG and CG groups, resulted from qualitative changes in the diet of the participants. Introducing products with low glycemic index carbohydrates and increasing the consumption of high-protein products led to an average daily protein intake increase of 24% (29.6 g) and a 46% increase in fiber content. The consequence of these qualitative changes was a reduction in energy sources in the diet, with a decrease in carbohydrates by an average of 87.1 g/day and fats by 34.1 g/day, resulting in a reduction in daily dietary energy from the initial value by 536.6 kcal/day. The dietary intervention yielded the expected effects, leading to an unconscious attainment of a negative energy balance among EDG participants, resulting in a reduction in BM. In the EDG group, a negative correlation was confirmed between protein (r = −0.33) and fiber (r = −0.37) intake and the energy value of the diet (data not included). The unconscious restriction of energy in the diet by the EDG group participants, confirmed by the occurrence of significant correlations, was probably the result of an increased feeling of satiety after consuming foods with a low glycemic index and an increase in protein supply. According to our recommendations, the subjects were to eat meals until satiated and choose quality food products, according to the dietitian’s instructions. Despite the increased supply of protein in the diet of the subjects, the energy value of the diet decreased due to the unconscious restriction of fat (p < 0.01) and carbohydrate (p < 0.01) consumption. The other groups taking part in the study did not make any significant changes to their diet, in accordance with the recommendations.

Similar dietary interventions were applied in the European-wide Diogenes study conducted on 891 families predisposed to overweight/obesity. In this study, the implementation of a high-protein diet with low glycemic index carbohydrates prevented the recurrence of BM30. In this study, the implementation of a high-protein diet with low glycemic index carbohydrates prevented the recurrence of body mass. Engaging in exercise alone in the EG group in the present study was associated with a decrease in BF by 0.3% and visceral fat by 1.0% (although the observed changes were not significant).

Among various components of lifestyle, in addition to biological predispositions, physical activity plays a primary role in the distribution and levels of body fat31,32. Maintaining a high level of physical activity provides an opportunity to achieve favorable changes in body composition; however, the present study was limited to a relatively short duration of 6 weeks. As confirmed by other studies, extending the intervention period allows for a greater reduction in visceral fat and total body fat, reaching significant levels after a 12-week period22.

The appetite-regulating effect of asprosin (ASP) involves promoting the activity of the orexigenic receptor protein, receptor tyrosine phosphatase δ (Ptprd) in AgRP + neurons in a cAMP-dependent manner; while simultaneously inhibiting anorectic POMC + neurons in a GABA-dependent pathway, thereby stimulating appetite and promoting body weight accumulation similarly to ghrelin12. ASP, identified as gluconeogenic hormone induced during fasting, employs a signaling pathway involving a G protein and cyclic AMP (cAMP) to activate protein kinase A (PKA) in the liver, thereby enhancing the release of glucose from hepatocytes4. Elevated insulin levels counteract the effects of ASP by suppressing its ability to stimulate PKA activity and glucose release33. The aerobic exercise has been shown to diminish hepatic ASP levels via the PKA/TGF-β pathway, concurrently enhancing the AMPK-related signaling pathway. This exercise-induced modulation alleviates impaired glucose metabolism and proves beneficial in the treatment of diabetes mellitus (DM) in rats34. Exercise exerts positive effects on insulin sensitivity and glycogen storage in skeletal muscle by upregulating the expression of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4)35. A recent investigation into skeletal muscle glucose uptake reveals that ASP, enhances glucose transport by elevating GLUT4 levels in myotubes. Notably, the promotion of glucose uptake is facilitated by AMPK phosphorylation in skeletal muscle following exogenous administration of ASP36. As emphasized by Liu et al37., these findings introduce a degree of contradiction to prior studies that suggest diverse effects of ASP on various pathways; by inference, further research is warranted.

In the present study, the implementation of an exercise intervention and a combination of exercise and diet was associated with a decrease in ASP and LEP concentrations after 6 weeks. The influence of exercise alone was associated with a reduction of 14% in ASP and 10% in LEP concentrations, although the changes did not reach significant levels. On the other hand, more favorable outcomes were observed in the exercise plus diet group, significant reductions of 16% in ASP and 48% in LEP concentrations after the 6 week intervention. Even a modest weight reduction of 4% associated with a low-energy diet lead to a decrease in LEP, in the case of other adipokines, significant changes often do not necessarily occur despite weight reduction reaching 14%38. A meta-analysis comparing the application of exercise alone to exercise in conjunction with diet al.so confirms the occurrence of a greater reduction in LEP levels in the group implementing the combined intervention39. After 14 weeks of aerobic exercise combined with an intervention diet, with an assumed daily energy deficit of 500 kcal, there was a reduction in ASP levels (−32%) and BM (−10%)29.

In the present study, the group implementing a combination of diet and exercise experienced a 5% reduction in BM within 6 weeks, which was apparently sufficient to induce significant changes in levels of the described adipokines. It is worth emphasizing that, with the application of the weight reduction methods in the present study, it would be advisable to extend the duration of the intervention, while avoiding an increase in the energy deficit due to the likelihood of regaining weight over time40.

The specific type of exercise undertaken also plays a crucial role in regulating the described adipokines. The reduction in LEP levels in obese men with metabolic syndrome occurs gradually under the influence of a combination of aerobic and resistance training, reaching a reduction of 26% after an intervention of 12 weeks22. A meta-analysis of studies also confirmed that engaging in aerobic physical activity, resistance exercise, and the combination of both forms of physical activity leads to a significant reduction in LEP concentrations during the implementation of long-term interventions41. In the case of ASP, research results are inconclusive. In obese men, a significant decrease in ASP levels was observed after 12 weeks of resistance training21, while in another study, a combination of aerobic and resistance training was not associated with significant reductions in ASP concentrations in individuals with metabolic syndrome42.

The implementation of physical exercises alone, in the form of a combination of aerobic and resistance training, already leads to a significant reduction in insulin resistance, specifically after three sessions per week over 16 weeks43. In our current study, the QUICKI level increased in both intervention groups after 6 weeks (Table 3). A meta-analysis of studies demonstrated that the combination of diet and physical exercises results in a greater reduction in visceral fat tissue, along with a decrease in insulin resistance levels, compared to engaging in exercise alone44.

Also in the present study, ASP concentrations were significantly correlated with total cholesterol (TC) levels in the intervention groups, an observation not corroborated in a study of patients with metabolic syndrome45. On the other hand, a study of mice noted a decrease in cholesterol levels after four administrations of ASP at a dose of 10 µg/kg, suggesting a potential mechanism for preventing metabolic complications of diabetes46. Of course, changes occurring with insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes may be both a result and a cause of developing obesity47.

The exercise and diet intervention was associated with an average 11% decrease in TC levels after 6 weeks of intervention. Such results are comparable to the chronic use of certain statin-class hypocholesterolemic medications48. A 10% reduction in cholesterol lowers the risk of death from coronary heart disease (CHD) by 15% and the overall risk of death by 11%49. However, in a study comparing the use of aerobic exercise with a combination of aerobic and resistance training, no significant changes in non-HDL cholesterol levels were achieved as a result of the exercise interventions22.

A significant correlation was confirmed between cholesterol levels and ASP in the EG (r = 0.38) and EDG (r= 0.48) intervention groups. The presented relationship between the indicators may result indirectly from the relationship between insulin resistance and hypercholesterolemia. ASP affects glucose metabolism, among others, by acting on its receptor in the liver50. ASP levels are closely related to the level of insulin resistance in patients with obesity51. Insulin resistance may excessively stimulate the synthesis of the liver enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMG-CoA reductase), which plays an important role in cholesterol synthesis52. High concentrations of ASP may also lead to fatty liver disease associated with metabolic dysfunction (MAFLD), and consequently to increased levels of TC, LDL, TG and decreased HDL in obese individuals or those with type 2 diabetes53,54. Complications resulting from the effect of ASP on insulin resistance and hypercholesterolemia are observed, among others, in the development of coronary artery disease55.

In addition to the introduction of physical activity, the increase in dietary fiber may have contributed to the reduction in TC levels. A moderate correlation was confirmed between fiber levels in the EG group and the EDG group. Increased intake of dietary fiber is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases. It has been demonstrated that fiber lowers blood cholesterol through several different mechanisms56. Recommended fiber intake varies across countries, ranging from 18 to 38 g/day for adults57,58. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for total fiber intake for healthy individuals aged 19–50 is 38 g/day for men and 25 g/day for women59. Despite the numerous health benefits of dietary fiber, the average daily intake for most Americans is 15 g/day, significantly below the recommended levels59. According to WHO/FAO recommendations, a daily intake of 25 g of fiber allows for proper body functioning58. In the present study, the average fiber intake of participants was 23.4 g/day, which was below the WHO recommended intake, and there were no significant differences in fiber intake between the study groups at baseline or in the CG and EG groups after 6 weeks. On the other hand, a significant increase in fiber consumption was observed in the EDG group, reaching 33.1 g/day of fiber after the 6 week intervention, an increase in daily intake by 10.4 g. Higher fiber intake was also negatively correlated with ASP concentration in the EG (r = −0.39) and EDG (r= −0.33) groups. Results of a meta-analysis also indicate that 7 g/day increase in fiber consumption was associated with a lower risk of both cardiovascular diseases and coronary heart disease60. Increasing dietary fiber is one of the main dietary recommendations in current trends for weight reduction and obesity treatment61.

The present study is not without limitations. Numbers of subjects were limited and the duration of the intervention was only six week. Undoubtedly, the lack of a group in which the influence of the diet itself on the analyzed parameters was tested is a limitation of the project. During the project, the VO2 max test was not performed, which would allow monitoring of training adaptation in the intervention groups. The study also falls short of elucidating the intricate mechanisms which underlie changes in adipokine concentrations following exercise and dietary interventions. It is recommended that future investigations involve a broader cohort of volunteers afflicted with abdominal obesity, include both males and females, and different age groups. Subsequent research, potentially linked to the expression of microRNAs also warrants exploration to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the processes.

Conclusions

A combination of resistance-aerobic training with a diet based on low glycemic index products and higher protein content resulted in significant changes in body composition, including a reduction in BM, BF and ANDR, and an increase in FFM. The group implementing both diet and exercise also experienced a 16% reduction in asprosin (ASP) and a 48% reduction in leptin (LEP) concentrations, indicating a favourable impact of the intervention on adipokine regulation, and yielding more beneficial changes than exercise alone. A mean reduction of 11% in total cholesterol (TC) levels was also confirmed after 6 weeks of intervention in this group. Increasing dietary fiber content was also negatively correlated with both TC and ASP levels. Both intervention groups showed an increase in the QUICKI index, suggesting an improvement in insulin sensitivity. In summary, the combination of exercise with an appropriate diet is crucial for achieving beneficial changes in body composition, adipokine regulation, improvement in insulin resistance and lipid profile.

Methods

Study design

The research protocol used a prospective, randomized and controlled study design. The aim of the study was to compare the effect of 6-weeks of aerobic-resistance exercises (group EG) and of aerobic-resistance exercises combined with a high-protein, low-glycemic index carbohydrate diet (group EDG) on the concentrations of asprosin (ASP) and leptin (LEP), indicators of carbohydrate metabolism, and cholesterol levels in men with abdominal obesity, compared to men with abdominal obesity not subjected to intervention (control group CG). The variables examined in this manuscript are part of a broader research project that explored the impact of exercise and dietary interventions on body composition, as well as selected biochemical parameters in men with abdominal obesity62.

A random allocation process was used to assign obese men to each of the three groups. Participants were assigned to three groups based on the selection of an opaque envelope containing a number for each of the three groups. During the statistical analysis of results and biochemical determinations, personnel were unaware of the group allocations. Due to the nature of the intervention or its lack, a blind procedure was not applied.

The study included 44 Caucasian men 30 to 40 years (mean age 34.7 ± 5.5 years) who met the main selection criterion for abdominal obesity: an increased waist circumference (WC) above 94 cm. Participants were randomly assigned to three groups:

-

Experimental group EG (n = 16, 34.8 ± 6.0 years) who performed aerobic-resistance exercises (WC: 110.8 ± 11.3 cm; BMI: 32.2 ± 4.3 kg/m2);

-

Experimental group EDG (n = 16, 34.9 ± 5.6 years) who engaged in aerobic-resistance exercises combined with a high-protein, low-glycemic index carbohydrate diet (WC: 108.9 ± 7.6 cm; BMI: 32.1 ± 3.7 kg/m2);

-

Control group CG (n = 12, 34.1 ± 5.5 years) without any intervention during the project duration (WC: 111.2 ± 6.8 cm; BMI: 31.7 ± 3.7 kg/m2).

The basic characteristics of the research participants in the control (CG), exercise (EG) and exercise-diet (EDG) groups are presented in Table 7. There were no differences between CG, EG, and EDG with respect to age and basic anthropometric parameters before the interventions.

The assignment to the intervention was parallel, conducted by a trainer. The recruitment and intervention period spanned from February 2022 to July 2022, ensuring the study groups reached the minimum required sample size. No harm or adverse events were reported during the trial.

In addition to male gender and confirmation of abdominal obesity, the study considered the following criteria: age 30–40 years, a medical certificate confirming no contraindications for aerobic-resistance exercises, written consent for voluntary participation in the research project, and no health contraindications such as ischemia, decompensated heart failure, heart rhythm disorder, severe pulmonary hypertension, symptomatic aortic stenosis, acute myocarditis, endocarditis or pericarditis, uncontrolled blood pressure, aortic dissection, Marfan syndrome, uncontrolled diabetes, mental disorders, health problems preventing movement, participation in another form of physical activity during the project, and lack of written consent to take part in the examination.

Exclusion criteria from the research project included: lack of a medical certificate confirming the ability to engage in resistance and aerobic training, excessively low attendance at training sessions in intervention groups (minimum attendance above 90%).

Volunteers underwent training, received a written description of the goals, procedures, and planned course of the research project. Each participant could withdraw from the study at any time without facing consequences.

Participants were trained by the same personal trainer and were asked not to engage in additional physical activity outside the protocol. They were also instructed to adhere to the medication and dietary supplement schedule during the observation period.

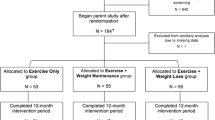

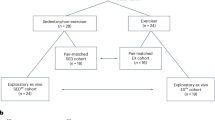

All participants in the study provided written consent for the processing of personal data, voluntary participation in the study, and the use of obtained results for scientific purposes. There were cases of patients resigning from the training and of exclusion of participants due to: more than 10% of missed training (2 cases), failure to follow dietary recommendations (3), uncontrolled alcohol intake (1), absence at control sessions (3). The research project obtained approval from the Ethics Committee of the Regional Chamber of Physicians in Krakow (15/KBL/OIL/2022), and all methods adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and the study was registered in the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry under the registration number ACTRN12624000184572 (26/02/2024), following CONSORT guidelines. The flowchart of the study is presented in Fig. 3.

Methods

The following assessments were performed all participants on two occasions, before and after 6 weeks of the intervention:

Anthropometry

For the purpose of this study, body height (BH) [cm], body mass (BM) [kg], and waist circumference (WC) [cm] were used. BH was measured to the nearest 1 mm, in a standing position without shoes, with the head in the Frankfurt plane, using a stadiometer (Seca 231 stadiometer, Hamburg, Germany). BM was obtained in the standing position using a standardized medical scale (Beurer PS 240, Budapest, Hungary), with an accuracy of 50 g. WC was measured to the nearest 1 mm using an anthropometric tape between the lower edge of the costal arch and the upper edge of the iliac crest, with the participant in standing position, and recorded at the end of a gentle expiration. The body mass index (BMI) [kg/m2] was calculated.

Body composition

Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) was applied to assess body composition: percentage of body fat (BF) [%], android fat (ANDR) [%], fat free mass (FFM) [%], and body mass index (BMI) [kg/m2]. A Lunar Prodigy Primo PR + 352,163 (Chicago, IL, USA) was used.

Hormones

Fasting blood samples were collected in the morning after a 24-h break from training, from the basilic, cephalic, or median cubital vein into test tubes (Vacumed® system, F.L. Medical, Torreglia, Italy) by the experienced nursing team. The collected blood was centrifuged (RCF 1000× g) immediately after collection for 15 min at 4 °C (MPW-351R, MPW Med. Instruments, Warsaw, Poland), and the serum was collected and stored at − 80 °C until further study (BIO Memory 690 L, Froilabo, Paris, France).

The concentrations of asprosin (ASP) and leptin (LEP) were measured using commercially available ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The detection kits for ASP (ELISA Kit catalog number 201-12-7691) were purchased from Shanghai Sunred Biological Technology Co. (Shanghai, China). The human LEP Sandwich ELISA Kit (catalogue number EIA-2395) was provided by DRG Instruments GmbH (Marburg, Germany). An ELx 808 spectrophotometric microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) was used to determine the optical density at 450 nm. Marking was performed at the Laboratory of Genetics and Molecular Biology, Department of Physiology, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Cracow, Poland.

Biochemical blood indices

The concentration of glucose (GL) [mmol/L] in the blood plasma was performed via the enzymatic method using the Cobas c701/702 biochemical analyzer (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd., Mannheim, Germany). The serum insulin (INS) [µIU/mL] concentration was determined by electrochemiluminescence (ECLIA) using the Cobas e801 apparatus (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd., Mannheim, Germany). The determinations were performed according to manufacturer’s guidelines with the use of reagents dedicated to the GLUC3 and Elecsys Insulin analyzers, respectively.

Sensitivity to insulin was determined with the quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) as follows63:

The plasma levels of total cholesterol (TC) was specified with the spectrophotometric method relying on guidelines of the clinical chemistry analyser Architect ci-4100 (Abbott Laboratories). Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) for the assays were 0.9–1.2 and 1.2–1.8%, respectively.

Estimation of total energy expenditure and energy value of diet

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used to assess daily energy expenditures64. The total energy expenditure (TEE) [kcal/week] was estimated based on the sum of the basal metabolic rate, calculated individually using the Mifflin-St Jeor formula65, energy expenditure self-reported using the IPAQ questionnaire and energy expenditure associated with the respective intervention groups, EG and EDG. In the intervention groups, energy expenditure during training was measured using the Polar M200 GPS Running Watch with Wrist-Based Heart Monitor (Kempele, Finland).

To estimate energy intake based on the diets of the participants, a clinical dietician conducted a 24 h nutrition interview using the nutrition record method. The data were analyzed using the DietaPro program (version 4.0, Institute of Food and Nutrition, Warsaw, Poland) to quantitatively assess nutritional intake and monitor any changes in the diet during the intervention (EG and EDG) and observation (CG). Based on the obtained results, a report of dietary nutrients was generated: proteins [g], carbohydrates [g], fiber [g] and fats [g].

In the group subjected solely to aerobic-resistance exercises (EG) and in the control group (CG), participants were advised not to change their dietary habits. In the group exposed to specific exercises along with dietary intervention, qualitative changes to the diet were implemented by increasing protein intake and introducing low glycemic index products. In addition to a 24-hour dietary recall conducted by a dietitian, participants entered consumed products daily into the Fitatu dietary program (version 3.41, Fitatu Ltd. Poznan, Poland) which provided a more reliable means of monitoring dietary compliance. For each training session, a clinical dietitian, verified the accuracy of the data entered into the program and provided consultations related to diet monitoring.

Exercise and dietary interventions

Aerobic–resistance exercises

Exercise interventions for the EG and EDG groups took place in a fitness club under the supervision of a personal trainer for a period of six weeks, three times a week, with the duration of a single session: one hour. Training sessions were consistently scheduled in the evening, from 6 to 9 pm, and conducted by the same personal coach. The exercise sessions took place in a controlled environment with a constant temperature of 22 degrees Celsius and maintained humidity 45%. Adherence to the intervention protocol was tracked through a session attendance checklist. Participants failing to attend more than 10% of the prescribed training sessions over the six-week period were excluded from the subsequent analysis.

Prior to beginning the intervention, participants underwent a one-week training program during which they were instructed by a personal trainer on the aerobic-resistance exercises; this protocol facilitated the initial adaptation of individuals to the training regimen. The training adaptation consisted of learning basic strength exercises, gradually increasing the intensity and training volume, so that during the intervention the subjects could use the full training procedure. Participants performed a one-repetition maximum (1RM) test, considered the gold standard for assessing muscle strength in non-laboratory situations66,67.

Aerobic-resistance training (see Supplement, Table S1) took place three times a week in groups of no more than five individuals. The program began with a five-minute aerobic warm-up on a treadmill at an intensity of 50% HR max. “A push-pull” training approach was applied, alternating engagement of antagonistic muscle groups. On „pull” days, gluteal muscles, hamstrings, back muscles, rear deltoids, and biceps were trained. On „push” days, quadriceps, chest muscles, arm muscles (front and lateral deltoids), and triceps were trained. Each resistance training session included 6 exercises, 4 sets per exercise, with 12 repetitions and 60-second breaks between sets. Loads were set at 70% of one-repetition maximum (1RM).

An aerobic training component ensued following the resistance exercises. Participants trained at 70% of maximum heart rate (HR max) on a treadmill (Technogym New Excite Run Now 500, Cesena, Italy), stationary bike (Technogym Artis, Cesena, Italy), or elliptical trainer (Precor EFX556i Elliptical, Woodinville, WA, USA). To prevent lower limb overloading, participants alternated between these three devices. The duration of the resistance training session varied 40 min, followed by aerobic training sessions of 10 min, respectively. Each training session concluded with a 5-minute cool down, breathing exercises, stretching phase.

High-protein, low-glycemic index carbohydrate diet

The dietary regimen of the EDG experimental group focused on high protein intake and included carbohydrates with a low glycemic index. As noted by other authors, sustaining all aspects of the diet, particularly the correct energy value over an extended period, is highly unlikely68,69 therefore, the primary nutritional education objective for the participants was to specify certain groups of food products. The main sources of energy were carbohydrates with a low glycemic index, including low-energy vegetables and fruits, and whole grain products. The second predominant nutritional component in the diet of participants was protein, specifically animal sources, such as lean dairy, meat and fish. The objective of the qualitative changes in the diet was to achieve an unconscious energy balance of approximately 500 kcal per day, resulting in a weekly weight loss of approximately 0.5 kg and a total of 3 kg over the 6 weeks of the experiment. The qualitative objective was to attain high protein intake that approximated 25% of the dietary energy, with carbohydrates at 50% and fats at 25%. Low glycemic index carbohydrates are characterized by high fiber content; hence, it was assumed that their consumption in the EDG group amounted to > 30 g per day.

In addition to regular direct dietary consultations, study participants received individually prepared materials with recipes, a shopping list, essential information, and dietary recommendations.

The “shopping center” approach was implemented30,68 as it resembled an “ad libitum” form of nutritional intervention, allowing individuals the freedom to choose food products within specified parameters. Achieving a negative energy balance was determined by calorie restriction, resulting in a greater feeling of satiety after consuming specific types of foods. The detailed course of nutritional intervention was presented as follows:

-

Participants shopped in designated chain stores where the type and quality of products were highly similar (supplied from the same warehouse).

-

Participant education was based on the graphic representation of products from which the subjects prepared meals. To present high-protein products and carbohydrates with a low glycemic index, a photo album of food products and dishes was used (Institute of Food and Nutrition, Warsaw, Poland, 2000).

-

A personal photo report of nutritional products from a popular shopping center was also used to facilitate the subjects’ shopping and to maintain the diet’s principles.

-

Participants utilized electronic scales, with an accurate to 1 g, to weigh products before consumption or culinary processing.

-

After each meal, participants entered the consumed products into a dietary program Fitatu (vesion 3.41, Fitatu Ltd. Poznan, Poland), installed on a mobile application, and received a report on consumed calories and specific nutrients.

-

Once per week, a qualified dietitian monitored the program report and provided individual feedback to the participants regarding the adherence to the prescribed diet parameters.

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was initially used to check whether the sample follows a normal distribution. As the majority of variables had a normal distribution, differences between the intervention groups and the control group were estimated using the two-way mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) for independent groups. The comparison of the intervention influence on changes in the variables between the experimental groups and control group was performed using a two-way mixed-design ANOVA test for dependent groups with post-hoc comparisons EMMs (Estimated Marginal Means). The effect size (ES) was calculated using the 𝜂p2 coefficient, the ratio of the sum of squares for the effect to the sum of squares for the error:

The interpretation of the ES was as follows: 0.01 ≤ 0.05 (low effect), 0.06 ≤ 0.13 (moderate effect) and ≥ 0.14 (high effect).

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were used to evaluate relationships among ASP, LEP and other measured parameters. Interpretation of correlations were as follows: 0 ≤ r < 0.3, no or very weak; 0.3 ≤ r < 0.5, moderate; 0.5 ≤ r < 0.7, strong; and 0.7 ≤ r≤ 1, very strong70.

The minimum sample size was determined using the solve_power function from the statsmodels library in Python for ANOVA analysis: repeated measures, within–between interaction (2 measures, 3 groups). The sample size was calculated for test power 1-β = 0.80, p = 0.05 and effect size d = 0.8. Under these assumptions, the total sample size required was estimated to be 46, which, after rounding, equates to 7 individuals per each of the three groups. The analysis was carried out according to the originally assigned groups.

In all the analyses, effects were considered significant if their probability value p was less than the assumed significance level α = 0.05 (p < 0.05). The R programming language and tidyverse, psych, corrr, emmeans, and ggplot2 packages in the RStudio IDE were applied to perform all calculations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bray, G. A. & Bouchard, C. The biology of human overfeeding: a systematic review. Obes. Rev. 21, 13040. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13040 (2020).

Hinney, A., Körner, A. & Fischer-Posovszky, P. The promise of new anti-obesity therapies arising from knowledge of genetic obesity traits. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 18, 623–637. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-022-00716-0 (2022).

Choe, S. S., Huh, J. Y., Hwang, I. J., Kim, J. I. & Kim, J. B. Adipose tissue remodeling: its role in energy metabolism and metabolic disorders. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 7, 30. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2016.00030 (2016).

Romere, C. et al. Asprosin, a fasting-induced glucogenic protein hormone. Cell. 165, 566–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.063 (2016).

Hoffmann, J. G., Xie, W. & Chopra, A. R. Energy regulation mechanism and therapeutic potential of asprosin. Diabetes. 69, 559–566. https://doi.org/10.2337/dbi19-0009 (2020).

Cammisotto, P. & Bendayan, M. A review on gastric leptin: the exocrine secretion of a gastric hormone. Anat. Cell. Biol. 45, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5115/acb.2012.45.1.1 (2012).

Andreoli, M. F., Donato, J., Cakir, I. & Perello, M. Leptin resensitisation: a reversion of leptin-resistant states. J. Endocrinol. 241, 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-18-0606 (2019).

Elmquist, J. K., Bjørbæk, C., Ahima, R. S., Flier, J. S. & Saper, C. B. Distributions of leptin receptor mRNA isoforms in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 395, 535–547. (1998).

Hileman, S. M. et al. Characterization of short isoforms of the leptin receptor in rat cerebral microvessels and of brain uptake of leptin in mouse models of obesity. Endocrinology. 143, 775–778. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.143.3.8669 (2002).

Goyal, R. K., Guo, Y. & Mashimo, H. Advances in the physiology of gastric emptying. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 31. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13546 (2019).

Zhao, S. et al. Partial leptin reduction as an insulin sensitization and weight loss strategy. Cell. Metab. 30, 706–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.005 (2019).

Duerrschmid, C. et al. Asprosin is a centrally acting orexigenic hormone. Nat. Med. 23, 1444–1453. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4432 (2017).

Alan, M. et al. A novel peptide hormone related to insulin resistance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 35, 220–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2018.1512967 (2019). E. Asprosin.

Ceylan, H. İ. & Saygın, Ö. An investigation of the relationship between new fasting hormone asprosin, obesity and acute–chronic exercise: current systematic review. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 127, 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/13813455.2020.1767652 (2021).

Wang, C. Y. et al. Serum asprosin levels and bariatric surgery outcomes in obese adults. Int. J. Obes. 43, 1019–1025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0248-1 (2019).

Sünnetçi Silistre, E. & Hatipoğl, H. U. Increased serum circulating asprosin levels in children with obesity. Pediatr. Int. 62, 467–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.14176 (2020).

Ugur, K. & Aydin, S. Saliva and blood asprosin hormone concentration associated with obesity. Int. J. Endocrinol. 1–8. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2521096 (2019).

Chhabra, K. H. et al. Reprogramming the body weight set point by a reciprocal interaction of hypothalamic leptin sensitivity and pomc gene expression reverts extreme obesity. Mol. Metab. 5, 869–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2016.07.012 (2016).

Zhao, S., Kusminski, C. M., Elmquist, J. K. & Scherer, P. E. Leptin: less is more. Diabetes. 69, 823–829. https://doi.org/10.2337/dbi19-0018 (2020).

Acosta, A. et al. Selection of antiobesity medications based on phenotypes enhances weight loss: a pragmatic trial in an obesity clinic. Obesity. 29, 662–671. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23120 (2021).

Jahangiri, M., Shahrbanian, S. & Hackney, A. C. Changes in the level of asprosin as a novel adipocytokine after different types of resistance training. J. Chem. Health Risks. 11, 179–188 (2021).

Makiel, K. et al. Impact of two types of exercise interventions on leptin and omentin concentrations and indicators of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in males with metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 12, 2822. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082822 (2023).

Matos, V. A. F. et al. Acute effects of high-intensity interval and moderate-intensity continuous exercise on glp-1, appetite and energy intake in obese men: a crossover trial. Nutrients. 10, 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10070889 (2018).

Martins, C. et al. Effect of moderate- and high-intensity acute exercise on appetite in obese individuals. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 47, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000372 (2015).

Halton, T. L. & Hu, F. B. The effects of high protein diets on thermogenesis, satiety and weight loss: a critical review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 23, 373–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2004.10719381 (2004).

Thomas, D. E., Elliott, E. J. & Baur, L. Low glycaemic index or low glycaemic load diets for overweight and obesity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007(3), CD005105. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005105.pub2 (2007).

Miketinas, D. C. et al. Fiber intake predicts weight loss and dietary adherence in adults consuming calorie-restricted diets: the POUNDS lost (preventing overweight using Novel Dietary Strategies) Study. J. Nutr. 149, 1742–1748. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxz117 (2019).

Roberts, S. Glycemic index and satiety. Nutr. Clin. Care. 6, 20–26 (2003).

Yao, T. et al. Diet and exercise interventions reduce serum asprosin and the corresponding hypothalamic-pituitary-gonad-axis dysfunction in obese men. Front. Physiol. 13, 896735. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.896735 (2022).

Larsen, T. M. et al. The Diet, obesity and genes (Diogenes) Dietary Study in eight European countries – a comprehensive design for long-term intervention. Obes. Rev. 11, 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00603.x (2010).

Suder, A. Socioeconomic and lifestyle determinants of body fat distribution in young working males from Cracow, Poland. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 20, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20687 (2008).

Suder, A., Płonka, M., Jagielski, P., Piórecka, B. & Głodzik, J. Physiological and environmental factors associated with central fat distribution in pubertal girls. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 66, 463–470 (2015).

Mazur-Bialy, A. I. Asprosin—a fasting-induced, glucogenic, and orexigenic adipokine as a new promising player. Will it be a new factor in the treatment of obesity, diabetes, or infertility? A review of the literature. Nutrients. 13, 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020620 (2021).

Ko, J. R. et al. Aerobic exercise training decreases hepatic asprosin in diabetic rats. J. Clin. Med. 8, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8050666 (2019).

Shulman, G. I. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 106, 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI10583 (2000).

Zhang, Y. et al. Expression and purification of asprosin in pichia pastoris and investigation of its increase glucose uptake activity in skeletal muscle through activation of AMPK. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 144, 109737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enzmictec.2020.109737 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. The effects of asprosin on exercise-intervention in metabolic diseases. Front. Physiol. 13, 907358. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.907358 (2022).

Klempel, M. C. & &Varady, K. A. Reliability of leptin, but not adiponectin, as a biomarker for diet-induced weight loss in humans. Nutr. Rev. 69, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00373.x (2011).

Khalafi, M., Hossein Sakhaei, S., Kheradmand, S., Symonds, M. & Rosenkranz, S. K. The impact of exercise and dietary interventions on circulating leptin and adiponectin in individuals who are overweight and those with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 14, 128–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advnut.2022.10.001 (2023).

Marinilli Pinto, A. et al. Successful weight-loss maintenance in relation to method of weight loss. Obesity. 16, 2456–2461. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.364 (2008).

Del Rosso, S. et al. Long-term effects of different exercise training modes on cytokines and adipokines in individuals with overweight/obesity and cardiometabolic diseases: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 24, 13564. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13564 (2023).

Suder, A., Makiel, K., Targosz, A., Maciejczyk, M. & Haim, A. Exercise-induced effects on asprosin and indices of atherogenicity and insulin resistance in males with metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 14, 985. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51473-1 (2024).

Makiel, K., Suder, A., Targosz, A., Maciejczyk, M. & Haim, A. Exercise-induced alternations of adiponectin, interleukin-8 and indicators of carbohydrate metabolism in males with metabolic syndrome. Biomolecules. 13, 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13060852 (2023).

Hens, W. et al. The effect of lifestyle interventions on excess ectopic fat deposition measured by noninvasive techniques in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Phys. Act. Health. 13, 671–694. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2015-0560 (2016).

Hong, T. et al. High serum asprosin levels are associated with presence of metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2021 (6622129). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6622129 (2021).

Hekim, M. G. et al. Asprosin, a novel glucogenic adipokine: a potential therapeutic implication in diabetes mellitus. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 129, 1038–1044. https://doi.org/10.1080/13813455.2021.1894178 (2023).

Malone, J. I. & Hansen, B. C. Does obesity cause type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)? Or is it the opposite? Pediatr. Diabetes. 20, 5–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12787 (2019).

Law, M. R., Wald, N. J. & Rudnicka, A. R. Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 326, 1423. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1423 (2003).

Gould, A. L., Rossouw, J. E., Santanello, N. C., Heyse, J. F. & Furberg, C. D. Cholesterol reduction yields clinical benefit: impact of statin trials. Circulation. 97, 946–952. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.97.10.946 (1998).

Li, E. et al. OLFR734 mediates glucose metabolism as a receptor of Asprosin. Cell Metabol. 30, 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.022 (2019).

Bhadel, P., Shrestha, S., Sapkota, B., Li, J. Y. & Tao, H. Asprosin and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a novel potential therapeutic implication. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents. 34 https://doi.org/10.23812/19-244-E (2020).

Sarsenbayeva, A. et al. Impaired HMG-CoA reductase activity caused by genetic variants or statin exposure: impact on human adipose tissue, β-Cells and metabolome. Metabolites. 11, 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11090574 (2021).

Lv, D., Wang, Z., Meng, C., Li, Y. & Ji, S. A study of the relationship between serum asprosin levels and MAFLD in a population undergoing physical examination. Sci. Rep. 14, 11170. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62124-w (2024).

Cui, J. et al. Association of serum asprosin with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in older adult type 2 diabetic patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 24, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-024-01560-1 (2024).

Moradi, N. et al. Serum levels of Asprosin in patients diagnosed with coronary artery disease (CAD): a case-control study. Lipids Health Dis. 20, 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-021-01514-9 (2021).

Soliman, G. A. Dietary fiber, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease. Nutrients. 11, 1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11051155 (2019).

Stephen, A. M. et al. Dietary fibre in Europe: current state of knowledge on definitions, sources, recommendations, intakes and relationships to health. Nutr. Res. Rev. 30, 2, 149–190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095442241700004X (2017).

Nishida, C., Uauy, R., Kumanyika, S. & Shetty, P. The joint WHO/FAO expert consultation on diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: process, product and policy implications. Public. Health Nutr. 7, 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2003592 (2004).

Trumbo, P., Schlicker, S., Yates, A. A. & Poos, M. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrates, fiber, protein, and amino acids. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 102, 1621–1630. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90346-9 (2002).

Threapleton, D. E. et al. Dietary fibre intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 347, f6879. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f6879 (2013).

Aaseth, J., Ellefsen, S., Alehagen, U., Sundfør, T. M., Alexander, J. & Diets and drugs for weight loss and health in obesity - an update. Biomed. Pharmacother. 140, 111789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111789 (2021).

Suder, A., Makiel, K., Targosz, A., Kosowski, P. & Malina, R. M. Positive effects of aerobic-resistance exercise and an ad libitum high-protein, low-glycemic index diet on irisin, omentin, and dyslipidemia in men with abdominal obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 16, 3480. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16203480 (2024).

Katz, A. et al. Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: a simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85, 2402–2410. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.85.7.6661 (2000).

Craig, C. L. et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35, 1381–1395. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB (2003).

Mifflin, M. D. et al. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 51, 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/51.2.241 (1990).

Levinger, I. et al. The reliability of the 1RM strength test for untrained middle-aged individuals. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 12, 310–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2007.10.007 (2009).

Grgic, J., Lazinica, B., Schoenfeld, B. J. & Pedisic, Z. Test-retest reliability of the one-repetition maximum (1RM) strength assessment: a systematic review. Sports Med. Open. 6, 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-020-00260-z (2020).

Skov, A. R., Toubro, S., Raben, A., Astrup, A. & A method to achieve control of dietary macronutrient composition in ad libitum diets consumed by free-living subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 51, 667–672. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600459 (1997).

Astrup, A. & Geiker, N. R. W. Efficacy of higher protein diets for long-term weight control. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 24, 224–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2014.02.003 (2014).

Pripp, A. H. Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Tidsskr nor. Laegeforen. https://doi.org/10.4045/tidsskr.18.0042 (2018).

Funding

The research project has been financed within the program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland, realized within statutory activities No. 270/BS/INP/2021 and No. 150/MN/INP/2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. and K.M. conceptualization; A.S., K.M., and A.T. methodology; A.S. and K.M. formal analysis; A.S., K.M., A.T. investigation; A.S., K.M. and P.K. data analysis; P.K. figure preparation; A.S. and K.M. writing—original draft preparation, A.S., K.M., A.T., P.K. and R.M.M. writing—review and editing; A.S. supervision; A.S. and K.M. project administration; A.S. and K.M. funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suder, A., Makiel, K., Targosz, A. et al. Effects of exercise and dietary interventions on asprosin, leptin, and lipid metabolism in males with abdominal obesity, a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 14, 28109 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79853-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79853-7

This article is cited by

-

Chemerin and Asprosin as Promising Biomarkers of Metabolic Syndrome: A Scoping Review

Current Obesity Reports (2025)

-

Pathophysiological insights into asprosin: an emerging adipokine in reproductive health

Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (2025)