Abstract

We propose a new drain-extended FinFET (DeFinFET) that can improve the intrinsic gain (gm/gds) and the electrical safe operating area (SOA). This structure features a novel utilization of the drain potential by using a floating poly (FP) and split high-k material (HK) on the drain and drift regions. This method effectively controls the potential drop profile within the drift region, which makes a uniform electric field distribution in the gate-on state. The evenly distributed electric field significantly increases the on-state breakdown voltage (7.33 V) compared to a conventional structure (5.89 V). In addition, it prevents the device from operating in an undesirable quasi-saturation mode, even after space charge modulation. This operation distinguishes our results from other studies, showing a notable improvement in gm/gds. Moreover, electron accumulation is induced in the drift region, leading to a significant decrease in the on-resistance. As a result, the proposed device demonstrates clear advantages in high-voltage applications with a 45% expanded electrical SOA over conventional DeFinFET.

Similar content being viewed by others

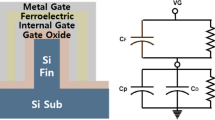

High-voltage transistors utilizing FinFET structures have been widely used in system-on-chip (SoC) technology1,2. To increase the off-state breakdown voltage (BVOFF), drain-extended FinFETs (DeFinFET) with a lightly doped drift region have been commonly employed3,4. However, the narrow fin-shaped drift region has the inherent problem of deteriorating on-resistance (RON)5. Several structures have been reported to alleviate this trade-off between BVOFF and RON, including high-k field plate6, fin/planar hybrid7, and additional longitudinal fins8.

Nonetheless, a notable limitation of these studies is that the electric field is concentrated at the drain edge (DE) when the gate is turned on5,9. This phenomenon occurs due to space charge modulation (SCM) in the drift region upon gate activation10. The intensified electric field at DE significantly decreases the on-state breakdown voltage (BVON) compared to BVOFF. Moreover, as the operation state of the device enters the quasi-saturation state, the transconductance (gm) decreases and output conductance (gds) increases10,11. As a result, the decrease in BVON and gm significantly narrows the electrical safe operating area (SOA)12. Additionally, the intrinsic gain (gm/gds) deteriorates due to the worsened gm and gds under the quasi-saturation state10. Various studies have attempted to solve this problem by using techniques including source underlap13 and deep drain diffusion14. However, it is important to note that these approaches mainly aim to delay SCM rather than redistribute the concentrated electric field at DE after SCM. This design strategy has the disadvantage of compromising gm and RON as the resistance of the device inevitably increases.

In this study, we propose a new high-voltage DeFinFET that utilizes a floating poly (FP) and split high-k material (HK) on the drain and drift region, hereinafter referred to as FPHK. FPHK aims to achieve a uniform distribution of the electric field even after SCM by utilizing the drain potential. The uniform electric field distribution is demonstrated by analyzing potential modulation mechanisms in the three regions of the drift facilitated by FP and HK. Specifically, the balance between each mechanism, which varies depending on the FP length, is analyzed to maximize the electric field distribution efficiency. Finally, the enhanced gm/gds and electrical SOA are demonstrated by achieving a uniform electric field distribution even after SCM.

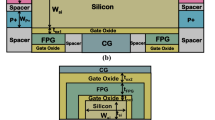

Proposed structure (FPHK) utilized in this study. (a) Bird’s eye view and (b) A-A’ cross-sectional view. Floating poly (FP) is partially introduced on the N-Well and drain junction, and high-k material (HK) is selectively deposited on the drift region adjacent to FP. The potential of FP is transmitted to the drift region through HK, leading to a potential modulation within the drift region. (c) Process flow for FPHK. The black text outlines the conventional Drain-extended FinFET. (i)-(iii) steps depict optimization factors for FPHK, and (iv) step describes an additional step specific to FPHK. Specific sections of the spacers and oxide are deliberately left out to improve the visual clarity of the structure.

Device structure and simulation Setup

Figure 1a and b show a bird’s eye view and the A-A’ cross-section of the proposed structure, respectively. N+ poly-Si was partially introduced above the N-Well and drain junction as FP, and HK was selectively deposited on the drift region adjacent to FP. As a result, the FP potential follows the drain bias, which is then transmitted to the drift region through HK. The structural parameters were designed based on Intel 10-nm node FinFET technology15. The key dimensions included a fin height (HFIN) of 54 nm and fin width (WFIN) of 7 nm. A 1.28 nm hafnium oxide (HfO2) layer (k = 25) was deposited on a 0.8 nm interfacial silicon oxide (SiO2) layer (k = 3.9), resulting in an effective oxide thickness (EOT) of 1 nm7,16,17. The total length of the gate and drift was set to 230 nm based on the reported high-voltage FinFET technology nodes7,18,19. Since a long gate overlap length (LOV) can decrease breakdown voltage and increase parasitic capacitance, LOV was minimized20. Additionally, to address hot carrier degradation effects, LOV was set to 20 nm. A trade-off was considered when setting the ratio of channel length (LCH) to drift length (LD)21. As the channel shortens, drain-induced barrier lowering (DIBL) increases even in FinFETs, and RON increases due to the long drift region. On the other hand, as the channel becomes longer, the electric field distribution area decreases, resulting in a lower breakdown voltage. Therefore, the dimensions were set to maximize BVOFF2/RON by carefully balancing the trade-off between breakdown characteristics and conductivity7. As a result of the optimization, LCH was set to 100 nm, LD to 110 nm, and gate length (LG) to 120 nm.

Notable locations including the K-point (K), gate edge (GE), high-k edge (HKE), floating poly edge (FPE), and DE are shown in Fig. 1b. These locations represent the points at which the key physical mechanisms change. Both the P-Well and N-Well were doped to a concentration of 1018 cm-3, and the source and drain were highly doped to 1020 cm-3. Titanium nitride (TiN) was used as the gate metal due to its high compatibility with the existing silicon-based bulk FinFET process22. The work function of TiN was adjusted to 4.45 eV to achieve an off-current of 0.1 nA/µm, which is a standard value for high-density logic FinFETs as defined by International Roadmap for Devices and Systems (IRDS)23. HK was constructed using HfO2 for compatibility with the current silicon FinFET process, and the dielectric constant (k) was set to 2516. The length of HK (LHK) was varied from 20 nm to 80 nm. The thickness of HK was set to 10 nm. If the high-k layer is too thin, the potential of FP may not be adequately transmitted to the drift region. It was observed that potential modulation in the drift region functions properly when the thickness of HK is at least 10 nm under our structural conditions. In this configuration, FP should be thicker than the high-k layer to effectively transmit the potential throughout the entire HK region, which led to setting the thickness of FP at 20 nm. However, since FP merely transmits the drain potential to the drift region and HK, variations in the thickness of FP do not significantly affect device performance, provided that N+ Poly-Si is used and is thicker than the high-k layer. Therefore, the thickness of FP can be flexibly adjusted based on process optimization. The conventional drain-extended FinFET (hereinafter referred to as Conv) without FP and HK elements was used as a comparison reference. This structure has been commonly used for comparison and is suitable for demonstrating the effects of HK and FP14,24.

Calibration results for measured data. (a) Transfer curve at VDS = 0.05 and 0.7 V. (b) Output curve at VGS = 0.5, 0.6, and 0.7 V. (c) Breakdown characteristic curve at VGS = 0.0 V. The simulation framework is fine-tuned to accurately capture the performance of nano-scale FinFET and breakdown mechanism in DeFinFET.

Figure 1c shows a brief overview of the fabrication process for the proposed structure. The black text describes the conventional DeFinFET process25, while (i)-(iii) and (iv) describe optimization factors and an additional step for the proposed structure, respectively. In step (i), N+ poly-Si is formed and extends into the drain region. In step (ii), gate removal is performed, leaving the drain edge region. In step (iii), HfO2 is deposited up to the poly-Si, and in step (iv), partial etching of the high-k material is carried out26. This proposed structure provides a straightforward alternative to conventional DeFinFET by utilizing poly-Si and HfO2, which are commonly used in silicon bulk FinFET processes. This approach significantly minimizes the need for extensive process development and ensures high compatibility with the existing silicon FinFET-based SoC technology, requiring only minor modifications.

FPHK was analyzed with 3-D Sentaurus TCAD simulation27. Figure 2a and b show the calibration results using experimental data from Intel 10-nm FinFET process15. This calibration included mobility and density gradient quantum corrections to ensure the reliability of nano-scale simulations. Additionally, a trap model was incorporated, considering trap concentration, distribution, and electron/hole capture cross sections to consider the interface trap. These parameters were adjusted based on established experimental data and theoretical models28,29. In this study, a series of related models were utilized to capture the electrical characteristics of FinFET. In particular, the Hydrodynamic model, tailored for transistors with a small active region such as FinFET, served as the carrier transport model27. The Philips unified model was incorporated to consider various factors affecting the carrier mobility30. Additionally, the Shockley-Read-Hall model was used to describe the recombination process31. Subsequently, the van Overstraeten model, which accounts for avalanche breakdown caused by impact ionization, was adopted and its coefficients were calibrated for measured data to reliably predict the breakdown phenomenon32. Additionally, a calibrated dynamic nonlocal model was used to represent band-to-band tunneling33,34. Figure 2c shows the calibration result for the breakdown characteristic curve of a fabricated bulk-Si DeFinFET35, demonstrating that the simulation framework accurately reflects the physical breakdown mechanism.

The current values, RON, gm, and gds were normalized to the layout area. RON was extracted at a gate-to-source voltage (VGS) of 0.7 V and a drain-to-source voltage (VDS) of 0.1 V. BVOFF was extracted at 1 nA/µm, corresponding to ten times off-current36. BVON was determined at a VDS where current snapback occurs with VGS of 0.7 V37. Off-state and on-state bias conditions were defined as VGS being 0.0 V and 0.7 V, respectively, with VDS of 3.3 V. The analysis of SOA was focused on electrical aspects without considering thermal effects12. The physical values inside the fin, including the electric field and potential, were extracted along the horizontal cut-line at HFIN/2 and WFIN/2.

Results and discussion

Enhancement of BV ON and R ON

Figure 3a shows the derivative of IDS as a function of VDS with VGS of 0.0 V and 0.7 V for Conv and FPHK. The voltage at which the current slope increases sharply indicates the breakdown point where current snapback occurs. While Conv and FPHK have comparable BVOFF, BVON decreases significantly in Conv. For Conv, the decrease from BVOFF to BVON is 2.12 V (from 8.01 to 5.89 V), while for FPHK, it is only 0.22 V (from 7.55 to 7.33 V).

(a) Derivative of IDS as a function of VDS with VGS of 0.0 V and 0.7 V for Conv and FPHK. The breakdown points representing BVON and BVOFF are indicated. (b)Elat under the gate-off and on state at VDS = 3.3 V for Conv. There is no significant difference between BVOFF and BVON for FPHK, while for Conv, the electric field is concentrated at the DE region upon gate-on, leading to a significant decrease in BVON.

Figure 3b shows the lateral electric field (Elat) for Conv when the gate is turned off and on to analyze the significantly lower BVON compared to BVOFF. At VGS = 0.0 V, the electric field has a peak near GE. However, a more pronounced electric field peak is observed near DE at VGS = 0.7 V. This phenomenon can be attributed to SCM induced by the increased VGS. When VGS = 0.0 V and VDS = 3.3 V, the N-type drift region is depleted due to the reverse bias. This depletion region is mainly composed of positive ions corresponding to the doping concentration of the N-drift region. When the gate is turned on, electrons from the channel flow into the drift region, neutralizing these positive ions. For very low VGS values (VGS < VT), where VT is the threshold voltage, the electron influx from the channel to the drift region is negligible, and this neutralization effect can be disregarded9. However, when VGS increases beyond VT, the electron flow increases significantly, resulting in a majority carrier concentration that exceeds the ionized impurity concentration. This neutralizes the depletion region near the channel14. As a result, to maintain charge balance, the entire depletion region moves toward the drain edge where a high concentration of positive ions remains10. This change results in a sudden drop in potential and a sharp increase in the electric field at DE. Therefore, it can be seen that the concentrated electric field at DE should be uniformly redistributed to improve BVON.

Figure 4a compares Elat for Conv and FPHK under the on-state bias condition to comprehend the BVON improvement in FPHK. FPHK shows an evenly distributed electric field due to the generation of peaks at several edges. This field distribution approaches the ideal distribution profile in contrast to Conv. The maximum Elat (Elat, max) for FPHK is 0.38 MV/cm, which is a 54% reduction value compared to Conv. This uniform electric field distribution is achieved through potential modulation mechanisms in the three regions of the drift region. These mechanisms can be easily confirmed through the potential drop profile.

Figure 4b shows the electrostatic potential in the drift region under the on-state bias condition for Conv and FPHK. First, in region (i), Conv shows a sharp potential drop of 0.66 V (from 3.37 to 2.71 V), while FPHK has a minimal potential drop, only 0.25 V (from 3.37 to 3.12 V). This discrepancy occurs because region (i) is located below FP. Since FP is located on top of the oxide layer, the potential of FP (VFP) can be expressed as follows: VFP = VD – VFB – VOX, where VD is the drain potential, VFB is the floating poly flat-band voltage, and VOX is the oxide potential drop. Considering the drain and FP share the same n-type doping concentration of 1020 cm− 3, VFB is approximately zero. Moreover, due to the very thin oxide layer (0.8 nm), VOX can be considered negligible. Therefore, VFP closely follows VD. This VFP is transmitted to the drift region, inducing a high potential in region (i) beneath FP. Consequently, the potential drop in region (i) is suppressed, thereby significantly reducing the electric field in region (i).

(a)Elat and (b) electrostatic potential in the drift region along the horizontal cut-line, and (c) electrostatic potential captured in the drift region under the on-state bias condition for Conv and FPHK. Conv shows a high electric peak at DE, whereas FPHK demonstrates an evenly distributed Elat with the suppression of sharp potential drop in the drift region. (d) Space charge for FPHK along the horizontal cut-line under the on-state bias condition at the regions (ii) and (iii).

Second, in region (ii) below HK, FPHK shows a relatively gradual potential drop compared to Conv. Conv shows a potential drop of 1.88 V (from 2.71 to 0.83 V), while FPHK shows a potential drop of 1.68 V (from 3.12 to 1.44 V). Figure 4c shows the cross-sectional electrostatic potential under the on-state bias condition for Conv and FPHK to provide a more visual representation of the potential profile. Since FP and HK are directly connected in the lateral direction to form an electrically connected structure, the increased potential of FP is laterally transmitted to the drift region through HK. This results in a uniform electric field distribution by gradually modulating the potential drop in region (ii).

Since the potential drop is suppressed in regions (i) and (ii), the potential of FPHK at HKE is higher than that of Conv. Therefore, FPHK shows a slightly steep potential drop in region (iii), resulting in an additional electric field peak. This electric field peak can contribute to a more uniform electric field distribution. The additional electric field peak can also be explained in terms of a space charge. Figure 4d shows the space charge distribution in drift region for FPHK under the on-state bias condition. The notable difference observed at the (ii)/(iii) interface is primarily due to the accumulation of electrons only in regions (i) and (ii), except in region (iii). FPHK may slightly increase the gate leakage due to formation of the additional field peak near GE after SCM. However, this additional peak is very close to the ideal field distribution and remains within the acceptable range for stable operation in the saturation region. Furthermore, this peak occurs approximately 40 nm away from the gate edge, reducing its effect on gate leakage. Additionally, since FPHK controls the lateral field, the vertical field to the gate, which is important for gate leakage, shows no significant difference between Conv and FPHK. Therefore, introducing the additional field in region (iii) helps achieve an ideal field distribution while minimizing the effect on gate leakage.

Figure 5a shows BVON and RON as a function of LHK to examine the optimal value of LHK. These analyses were performed with LCH, LD, and LG fixed at 100 nm, 110 nm, and 120 nm, respectively. First, FPHK shows higher BVON across the entire LHK range. In particular, it achieves the highest BVON of 7.33 V at LHK = 60 nm. Figure 5b shows how the Elat distribution varies with changes in LHK, providing a detailed analysis to understand the generation of the optimal point. Since the potential of FP, increased by the drain potential, is transmitted to HK, a gradual potential drop is formed in region (ii), as described in Fig. 4b. However, if region (ii) is too short, such as when LHK = 20 nm, this gradual potential drop cannot be fully established, resulting in a high potential at HKE and a high electric field peak in region (iii). On the other hand, if LHK is too long, such as 80 nm, most of the potential drops in region (ii), leading to a reduced electric field in region (iii) and a dominant field in region (ii). In other words, by controlling LHK, the electric field in regions (ii) and (iii) can be tuned, providing additional opportunities for the electric fields to be more evenly distributed. Figure 5c shows Elat, max and the region from which Elat, max is generated for FPHK with changes in LHK. The lowest Elat, max at LHK = 60 nm reflects the balance between electric field distribution in regions (ii) and (iii), and this result is consistent with the maximum BVON at the same LHK.

(a)BVON and RON for Conv and FPHK with different LHK. Throughout the entire LHK range, FPHK shows increased BVON and reduced RON compared to Conv. (b)Elat and (c)Elat, max for different LHK under the on-state bias condition for Conv and FPHK. At LHK = 60 nm, FPHK achieves the lowest Elat, max, showing a balance between electric field distribution within the region (ii) and (iii). (d) Electron density for Conv and FPHK under the RON extraction bias condition. The potential of FP, increased by drain bias, is transmitted to the drift region through HK, resulting in electron accumulation within the drift region.

FPHK also shows reduced RON across the entire LHK range, and RON decreases further as LHK becomes longer, as shown in Fig. 5a. In particular, FPHK shows a reduced RON of 16.2 Ω·µm2 at LHK = 80 nm, while Conv has a RON of 19.1 Ω·µm2. Figure 5d shows the cross-sectional electron density of the fin under the RON extraction bias condition for Conv and FPHK with LHK of 20 nm and 60 nm to confirm the effective reduction in RON for FPHK. FPHK shows a higher electron concentration below the HK region. As LHK increases, the area of enhanced electron density expands. This is due to the extended drain bias effect on the drift region, induced by FP and HK. As the drain voltage increases, the potential of FP rises and is transmitted to the drift region through HK. This phenomenon induces the electron accumulation in the drift region below HK. These additional electrons effectively alleviate the conductivity degradation caused by the fin-shaped lightly doped drift region5,6,7.

Quasi-saturation suppression

Figure 6a and b show transfer and output curves for Conv and FPHK with the optimum LHK of 60 nm. The transfer and output curves reveal that Conv shows a noticeable deterioration in the rate of current increase as VGS increases, and the output curve does not show stable saturation. In contrast, FPHK shows a continuous increase in current with increasing VGS and stable saturation characteristics in the output curve. Figure 6c and d show gm and gds, respectively, as a function of drain-to-source current (IDS) for Conv and FPHK. As clearly demonstrated by the transfer and output curves, FPHK maintains high gm with good flatness, and gds is suppressed even after SCM occurs. In contrast, Conv shows a sharp deterioration in both gm and gds characteristics after SCM.

Figure 6e shows the K-point potential (VK) as a function of IDS for Conv and FPHK to clearly analyze gm and gds in terms of quasi-saturation mode. Here, the K-point refers to the junction where the intrinsic MOS region and the drift region meet. Thus, this K-point can correspond to the junction of the channel and drain in a typical MOS transistor without drift region. Therefore, VK functions as the intrinsic drain voltage of the intrinsic MOS, and the operation mode of the intrinsic MOS is determined depending on VK11. If VK decreases, the operation mode of the intrinsic MOS is pushed towards a linear mode rather than a saturation mode. Therefore, a decrease in VK induces quasi-saturation where gm decreases and gds increases10.

(a) Transfer and (b) output curves for Conv and FPHK. (c)gm, (d)gds, and (e)VK for Conv and FPHK as a function of IDS. FPHK shows an improved gm flatness compared to Conv. As IDS increases, Conv shows a sharp increase in gds after SCM, while the increase in FPHK is suppressed. (f) Electron Density along the horizontal cut-line under the on-state bias condition for Conv and FPHK. FPHK shows a clearer pinch-off.

For both Conv and FPHK, VK increases before SCM occurs, but in Conv, it suddenly decreases after SCM, as shown in Fig. 6e. Since VK is affected by both the vertical gate and the horizontal drain potentials, interpreting VK behavior requires a combined analysis of both vertical and horizontal factors. In the voltage region where VGS < VT, VK increases linearly with VGS due to the vertical influence of the gate9. However, in Conv, when VGS exceeds VT and SCM occurs, a sharp voltage drop is observed in the drift region as described previously. From the horizontal perspective, VK is expressed as VKS = VDS – IDSRdrift, where Rdrift is the resistance in the drift region10. As the potential drop near drain edge (DE) increases due to SCM, IDSRdrift increases, which decreases VKS. This indicates that the operation mode of the intrinsic MOS has been pushed to the linear mode. On the other hand, FPHK has a range where VK increases even after SCM. This high VK can be explained by the combination of FP and HK, which suppresses the sharp potential drop in the drift region. Figure 6f shows the electron density under the on-state bias condition for Conv and FPHK to provide a visual representation of the pinch-off phenomenon associated with VK. FPHK shows a clearer pinch-off in the intrinsic MOS than Conv, indicating the stable saturation mode. Hence, FPHK effectively suppresses the quasi-saturation even after SCM, resulting in the improved gm and gds.

Evaluation of intrinsic gain and electrical SOA

Figure 7a shows the intrinsic gain, gm/gds, for Conv and FPHK. After SCM occurs, Conv experiences a sharp decrease in gm/gds due to the onset of quasi-saturation. In contrast, FPHK prevents a sudden decrease in gm/gds by suppressing a sharp potential drop in the drift region even after SCM. At a high-current condition with IDS = 0.16 mA/µm, gm/gds approaches nearly 0 in Conv, while it remains at 80 in FPHK. This demonstrates that FPHK can be utilized as an efficient amplifier that achieves high intrinsic gain even under high-current conditions after SCM.

Finally, Fig. 7b verifies the complete electrical SOA limits by sweeping VGS12. The VGS sweep is performed from 0.0 V to 0.7 V with 0.1 V steps. As VGS increases from 0.0 V, the breakdown value initially increases and then decreases. This occurs because a uniform electric field can be temporarily formed when the high electric field at GE shifts to DE due to SCM. The SOA boundary for FPHK expands to the right due to the increase in BVON and upward due to the reduced RON and increased gm, resulting in a 45% wider electrical SOA compared to Conv. This clearly confirms that FPHK can serve as a reliable device, enduring transitions between gate-on and off states under high-voltage and current conditions.

Conclusion

We have proposed a new DeFinFET with FP and HK (FPHK), which optimally controls the potential within the drift region by utilizing the drain potential. FPHK ensures a uniformly distributed electric field in the gate-on state. The uniform electric field reduces the on-state Elat, max by 54% compared to Conv, resulting in a high BVON of 7.33 V. Furthermore, VK continues to increase even after SCM unlike Conv. This significantly improves gm/gds by suppressing the undesired quasi-saturation. In particular, while gm/gds for Conv converges to 0 at the high-current condition, that of FPHK increases to 80 with good flatness. It proves that FPHK is a highly efficient amplifier. In addition, the electron accumulation in the drift region effectively reduces RON. These improvements in BVON, gm, and RON expand the electrical SOA by 45% compared to Conv, which means the enhanced device reliability under high-voltage and current conditions. The comprehensive analysis demonstrates that FPHK can be a promising solution for high-voltage FinFET applications in SoC technology.

Data availability

The data generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available for legal/ethical reasons but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Song, T. et al. A 14nm FinFET 128 Mb 6T SRAM with VMIN-enhancement techniques for low-power applications. In IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. Dig. Tech. Papers (ISSCC) 232–233 (2014).

Yeh, C. C. et al. A low operating power FinFET transistor module featuring scaled gate stack and strain engineering for 32/28nm SoC technology. In International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 34.1.1–34.1.4 (2010).

Kumar, B. S., Paul, M., Gossner, H. & Shrivastava, M. Physical insights into the ESD Behavior of Drain Extended FinFETs (DeFinFETs) and Unique Current Filament dynamics. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 67 (7), 2717–2724 (2020).

Paul, M. et al. Drain-extended FinFET with embedded SCR (DeFinFET-SCR) for high-voltage ESD Protection and Self-protected designs. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 66 (12), 5072–5079 (2019).

Kumar, B. S., Paul, M. & Shrivastava, M. On the design challenges of drain extended FinFETs for advance SoC integration. In Int. Conf. Simul. Semicond. Processes Devices (SISPAD) 189–192 (2017).

Kim, H. et al. High-voltage drain-extended FinFET with a High-k Dielectric Field plate. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 67 (3), 1077–1084 (2020).

Wu, Y. T. et al. Simulation-based study of Hybrid Fin/Planar LDMOS Design for FinFET-Based system-on-Chip Technology. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 64 (10), 4193–4199 (2017).

Shrivastava, M., Gossner, H. & Rao, V. R. A novel drain-extended FinFET device for high-voltage high-speed applications. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 33 (10), 1432–1434 (2012).

Kaushal, K. N. & Mohapatra, N. R. Unified theory of the Capacitance Behavior in LDMOS devices. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 69 (1), 39–44 (2022).

El-Kareh, B. & Hutter, L. N. Silicon Analog Components. Springer (2015).

Wang, L. et al. Physical description of Quasi-saturation and Impact-Ionization effects in high-voltage drain-extended MOSFETs. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 56 (3), 492–498 (2009).

Hower, P. Safe operating area - a new frontier in Ldmos design. In 14th Int. Symp. Power Semiconductor Devices ICs 1–8 (2002).

Bhoir, M. S. et al. Source Underlap—A novel technique to improve safe operating area and output-conductance in LDMOS transistors. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 66 (11), 4823–4828 (2019).

Kumar, B. S., Shrivastava, M. & Part, I. On the Unification of Physics of Quasi-saturation in LDMOS devices. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 65 (1), 191–198 (2018).

Auth, C. et al. A 10nm high performance and low-power CMOS technology featuring 3rd generation FinFET transistors, Self-Aligned Quad Patterning, contact over active gate and cobalt local interconnects. In International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 29.1.1–29.1.4 (2017).

Robertson, J. & Wallace, R. M. High-K materials and metal gates for CMOS applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 88, 1–41 (2015).

Balasubbareddy, M. & Sivasankaran, K. Impact of device-to-device thermal interference due to self-heating on the performance of stacked Nanosheet FETs. IEEE Access. 12, 26401–26409 (2024).

Lee, H. J. et al. Intel 22nm low-power FinFET (22FFL) process technology for 5G and Beyond. In IEEE Custom Integr. Circuits Conf. (CICC) 1–7 (2020).

Singh, J. et al. FinFET LDMOS technology challenges and opportunities for digital TV and 6GHz WiFi PA applications. In Symp. VLSI Technol. 1–2 (2021).

Kumar, B. S. & Shrivastava, M. Part II: RF, ESD, HCI, SOA, and self heating concerns in LDMOS devices Versus Quasi-saturation. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 65 (1), 199–206 (2018).

Oh, K. et al. A drain extended FinFET with enhanced DC/RF performance for high-voltage RF applications. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 37(11), (2022).

Ragnarsson, L-Å. et al. Ultrathin EOT high-κ/metal gate devices for future technologies: challenges, achievements and perspectives. Microelectron. Eng. 88 (7), 1317–1322 (2011).

IEEE International Roadmap for Devices and Systems 2020 More Moore. IEEE. (2020).

Pali, S. & Gupta, A. Design of drain-extended MOS devices using RESURF techniques for high switching performance and Avalanche Reliability. IEEE Access. 9, 155370–155379 (2021).

Three-Dimensional Simulation of 14/16 nm FinFETs With Round Fin Corners and Tapered Fin Shape. Synopsys (2013).

Lee, Y., DuMont, J. W. & George, S. M. Atomic layer etching of HfO2 using sequential, self-limiting thermal reactions with sn(acac)2 and HF. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 4 (6), N5013–N5022 (2015).

Sentaurus, T. C. A. D. Version P-2019.03. Synopsys (2019).

Esqueda, I. S., Barnaby, H. J. & King, M. P. Compact modeling of total ionizing dose and aging effects in MOS technologies. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 62, 1501–1515 (2015).

Esqueda, I. S. & Barnaby, H. J. Modeling the non-uniform distribution of radiation-induced interface traps. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 59, 723–727 (2012).

Klaassen, D. B. M. A unified mobility model for device simulation. In IEDM Tech. Dig. 357–360 (1990).

Schenk, A. A model for the field and temperature dependence of Shockley-Read-Hall lifetimes in silicon. Solid-State Electron. 35 (11), 1585–1596 (1992).

Rivera, E. C. & Moll, M. Study of impact ionization coefficients in silicon with low Gain Avalanche diodes. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 70 (6), 2919–2926 (2023).

Kao, K. H. et al. Direct and Indirect Band-to-Band Tunneling in Germanium-based TFETs. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 59 (2), 292–301 (2012).

Leung, G. & Chui, C. O. Stochastic variability in Silicon Double-gate lateral tunnel field-effect transistors. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 60 (1), 84–91 (2013).

Chen, B. Y. et al. RF power FinFET transistors with a wide drain-extended fin. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 56(4S), (2017).

Shrivastava, M., Baghini, M. S., Gossner, H. & Rao, V. R. Part I: Mixed-Signal performance of various high-voltage drain-extended MOS devices. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 57 (2), 448–457 (2010).

Hower, P. et al. Safe operating area considerations in LDMOS transistors. In 11th Int. Symp. Power Semiconductor Devices ICs 55–58 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the POSTECH-Samsung Electronics Industry-Academia Cooperative Research Center(IO201212-08129-01), in part by the MSIT(Ministry of Science and ICT), Korea, under the ICT Creative Consilience program(IITP-2020-2011-1-00783) supervised by the IITP(Institute for Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation), in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT)(RS-2024-00353588), and the EDA tool was supported by the IC Design Education Center (IDEC), South Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K. Oh and C.-K. Baek conceptualized the project and developed the methodology. K. Oh conducted the simulation, data analysis, and manuscript writing with assistance from H. Kim, Y. Kim, H. Yoo, and M. Choi. W. Maeng, S. Kim, and H.-J. Lee provided advice on the simulation work and fabrication process. C.-K. Baek provided overall guidance and supervision throughout the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oh, K., Kim, H., Kim, Y. et al. High-voltage FinFET with floating poly and high-k material for enhanced intrinsic gain and safe operating area. Sci Rep 14, 28448 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79881-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79881-3