Abstract

Research has shown various hydrolyzed proteins possessed beneficial physiological functions; however, the mechanism of how hydrolysates influence metabolism is unclear. Therefore, the current study aimed to examine the effects of different sources of protein hydrolysates, being the main dietary protein source in extruded diets, on metabolism in healthy adult dogs. Three complete and balanced extruded canine diets were formulated: control chicken meal diet (CONd), chicken liver and heart hydrolysate diet (CLHd), mechanically separated chicken hydrolysate diet (CHd). A replicated 3 × 5 Latin rectangle design was used with 10 adult beagles. Within each period, the assigned diets were fed to the beagles for 28 days after a 7-day wash out period. Plasma and fresh fecal samples were collected at day 28. Samples of diets, plasma, and feces were analyzed for global metabolomics with ultra-performance liquid chromatography and quadrupole-Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometer interfaced with a heated electrospray ionization source and mass analyzer. In general, there were lower fecal concentrations of dipeptides and protein degradation metabolites, indicating higher protein digestibility, in dogs fed protein hydrolysate diets in contrast with CONd (q < 0.05). Higher plasma pipecolate and glutamate, higher fecal spermidine and indole propionate, and lower phenol-derived products in both plasma and feces were found in CLHd group than CONd (q < 0.05), indicating lower oxidative stress and inflammation levels. The main difference in lipid metabolism between CHd and CONd was the bile acid metabolism, showing lower circulating bile acid, lower unconjugated bile acid excretion and higher taurine-conjugated bile acid excretion in the CHd group (q < 0.05). In conclusion, using chicken hydrolysates as the main protein source in extruded canine diets showed potential for physiological benefits in healthy adult dogs, especially protein hydrolysate from chicken heart and liver demonstrated effects on lowering inflammation and oxidation levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolomics has been previously described as “the study of metabolism at the global level”1. Researchers have been analyzing concentrations of various molecules in the blood, urine, and feces of dogs in the hopes of gaining more comprehensive views of potential mechanisms of different nutrients affecting the overall metabolic status of the animals. The ability to observe changes in multiple pathways allows researchers to obtain a clearer picture of the metabolic dynamics of the nutrients of interest. In addition, metabolites are the results of the changes in metabolism and, thus, could be studied to observe the true effects of the nutrients on the animals.

Functional ingredients or nutraceuticals have become popular additions to pet foods following the humanization and premiumization trends. Nowadays, pet owners have been more conscientious of the impact of the diets on their pets’ health and willing to spend more on foods which they deem healthy. Protein hydrolysates have been incorporated into canine diets to serve as protein sources or functional ingredients2. Some types of hydrolyzed proteins demonstrated beneficial functional effects on health, such as antioxidative, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, and immunomodulatory properties, while the sources of protein and application rate/method varied3,4,5,6. Several different types of antioxidative biopeptide were reported to be effective in preventing lipid peroxidation as free radical scavengers and metal chelators3,4,5. Antimicrobial peptides, from animal or bacteria origins, showed various modes of action and target microorganisms that are specific to the peptides3,5. Antihypertensive activity has been of interest especially in humans as cardiovascular diseases have become more prevalent and bioactive peptides could act as inhibitors of angiotensin I converting enzyme3,4,5. Some studies showed certain peptides had impact on specific immune responses and/or the innate immune system; however, the immunomodulatory effects were specific to the peptide and the mechanism is still unclear5. However, most studies only examined singular metabolites to test for those effects; important changes in other pathways could have been missed. Little is known about the process of how bioactive peptides lead to health benefits in the body and what overall changes in metabolism will occur. The present study aimed to examine the effect of different sources of protein hydrolysates, being the main dietary protein source in extruded diets, on protein and lipid metabolism in adult dogs. It was hypothesized that hydrolyzed proteins would lead to changes in protein and lipid metabolic pathways that would result in differences in protein and lipid metabolite concentrations in the plasma and feces, such as lower indispensable amino acids and proteolytic fermentative end products in the feces as well as lower oxidative metabolites in the plasma. The results could guide in establishing an understanding of the physiological process of protein hydrolysate contributing to health benefits for animals.

Results

Chemical composition of protein ingredients and diets

The macronutrient composition of treatment diets (CONd: chicken meal diet; CLHd: chicken liver and heart hydrolysate diet; CHd: chicken hydrolysate diet) is shown in Table 1. All diets had similar nutrient contents of 90.3 to 91.4% dry matter (DM), 94.2 to 95.2% organic matter (OM), 15.2 to 18.9% acid hydrolyzed fat (AHF), 25.2 to 29.4% crude protein (CP), and 13.4 to 14.7% total dietary fiber (TDF). Detailed analysis of the protein ingredients is available in a previous publication7.

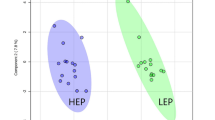

Principal component analysis and random forest plots

The overview of the metabolites in the diet, plasma, and fecal samples is shown in Table 2. A total of 1207 metabolites were detected in diet samples, 890 were detected in plasma samples, and 1101 for fecal samples. Both plasma and fecal principal component analysis (PCA) plots showed separation among treatment groups as the samples clustered by treatment (Figs. 1 and 2). Random forest analysis was performed to identify which metabolites contributed the most to the clustering of treatments observed. The top 30 ranking metabolites of importance in the plasma samples shown in Fig. 3 included 11 lipids, 10 amino acids derivatives, 5 xenobiotics, 4 cofactors and vitamins, and 1 peptide. The concentration of 3-methylhistidine was highest (P < 0.05; q < 0.05) in the plasma samples from CONd, followed by CHd, and then CLHd. The plasma content of 2-hydroxyphenylacetate was highest (P < 0.05; q < 0.05) in the CLHd group, followed by CHd, and then CONd. The concentrations of methionine sulfone and tryptophan betaine in plasma were the lowest in CLHd when compared with the others (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). On the other hand, the plasma concentration of leucylglycine was the highest in the CLHd group (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Plasma concentrations of homoarginine, N6-methyllysine, 3-amino-2-piperidone, and trans-4-hydroxyproline were higher in CONd than the others (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). The 1-methyl-5-imidazolelactate and 1-methyl-5-imidazoleacetate contents in the plasma samples were highest (P < 0.05; q < 0.05) in CHd, followed by CONd, and then CLHd. The top 30 ranking metabolites of importance in the fecal samples shown in Fig. 4 included 7 xenobiotics, 6 cofactors and vitamins, 5 amino acids derivatives, 5 peptides, and 5 lipids. Fecal concentrations of carboxymethylproline and prolylglycine were the highest (P < 0.05; q < 0.05) in the CLHd group when compared with the others. The concentrations of fecal N6-carboxyethyllysine and cyclo(his-phe) were the highest in the CONd group compared with the 2 other groups (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Fecal concentrations of cyclo(D-his-L-pro) and cyclo(pro-tyr) were the lowest in CONd when compared to the others (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Fecal carboxymethylarginine content was the highest (P < 0.05; q < 0.05) in CLHd, followed by CHd, and then CONd. The concentration of 1-methylhistidine in feces was highest in the CH group, followed by CONd, and the lowest in CLHd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Fecal homocitrulline content was highest in CONd, then CHd, and then CLHd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05).

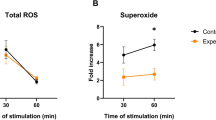

Protein metabolism

Several changes in metabolites of protein metabolism were observed in plasma samples of dogs fed different sources of protein, especially comparing between CLHd and CONd (Table 3). There were higher plasma levels of glutamate in the CLHd group in comparison with the CONd group (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Dogs fed CLHd had lower plasma concentrations of histidine and imidazole lactate, a downstream metabolite from histidine, but higher imidazole propionate and imidazole acetate, both can also be produced from histidine, when compared with dogs fed CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). There was lower plasma 5-aminovalerate but higher pipecolate, both being lysine downstream metabolites, in the CLHd group when compared with CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Dogs fed CLHd had a lower plasma level of phenylalanine and higher downstream metabolites of phenylalanine (2-hydroxyphenylacetate and 4-hydroxyphenylacetate) when compared with CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). In addition, in contrast with the CONd group, the CLHd group also had lower (P < 0.05; q < 0.05) plasma tyrosine, a dispensable amino acid made from phenylalanine, and phenol-derived products such as phenol sulfate, phenol glucuronide, and 4-methoxyphenol sulfate; on the contrary, other downstream metabolites from tyrosine (vanillactate, 3-methoxytyrosine, and dopamine 3-O-sulfate) were higher in CLHd group. Regarding metabolites from tryptophan, the CLHd group had higher plasma indole propionate and serotonin when compared with the CONd group (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Compared with dogs fed CONd, dogs fed CLHd had lower levels of plasma urea and metabolites from protein degradation, including trans-4-hydroxyproline, 3-methylhistidine, and 5-hydroxylysine (P < 0.05; q < 0.05).

There were similar changes in plasma protein metabolites between the CHd group and the CONd group as well, even though they were less prevalent than the differences between CLHd and CONd (Table 3). Dogs fed CHd had lower plasma concentrations of histidine, imidazole propionate, and imidazole acetate when compared with dogs fed CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). For downstream metabolites of phenylalanine, the CHd group had higher plasma 2-hydroxyphenylacetate and lower phenyl lactate in regards to the CONd group (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Dogs consuming CHd had lower levels of plasma trans-4-hydroxyproline and 5-hydroxylysine from protein degradation when compared with dogs consuming the control diet (P < 0.05; q < 0.05).

Fecal metabolites also indicated differences between CLHd and CONd groups (Table 4). Higher fecal concentrations of polyamines derived from arginine or ornithine (spermidine and spermine) were observed in dogs consuming CLHd than CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Higher fecal levels of molecules involved in the methionine cycle and transsulfuration pathway (betaine, cystathionine, and cysteine) were also seen in dogs consuming CLHd than in the CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). For histidine downstream metabolites, dogs fed CLHd had higher fecal histamine but lower 1-methylhistidine when compared with CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Regarding metabolites from lysine catabolism, there were lower fecal 5-aminovalerate, pipecolate, and 2-aminoadipate but higher cadaverine in the CLHd group in contrast with the CONd group (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). For fecal phenylalanine and formyl metabolites, dogs consuming CLHd had higher 2-hydroxyphenylacetate, 3-(4-hydroxyphenyl) lactate, and dopamine when compared with CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05); there were also lower phenol sulfate, phenylacetylglutamine, and 4-hydroxylphenylacetate concentrations in CLHd group than in CONd group (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Dogs fed CLHd demonstrated changes in fecal tryptophan metabolites with lower indole acetate as well as higher serotonin, indole propionate, indole acrylate, indole-3-carboxylate, kynurenine, and picolinate in comparison with CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Lower fecal metabolites from protein degradation (trans-4-hydroxyproline, 5-hydroxylysine, 1-methylhistidine, 3-methylhistidine, N6-acetyllysine, and dimethylarginines) were found in dogs fed CLHd than in dogs fed CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Lower fecal dipeptide and polypeptide concentrations were also seen in the CLHd group than in the CONd group (P < 0.05; q < 0.05), even though the peptide concentrations from the diet were higher in CLHd and lower in CONd.

Most amino acids were lower in concentration in fecal samples from dogs fed CHd when compared with CONd, including alanine, arginine, citrulline, proline, glutamate, glutamine, glycine, serine, threonine, leucine, isoleucine, valine, methionine, cysteine, taurine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan (Table 4; P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Some fecal metabolites from protein degradation (trans-4-hydroxyproline, 5-hydroxylysine, N6-acetyllysine, and dimethylarginines) were lower and some (1-methylhistidine and 3-methylhistidine) were higher in the CHd group in contrast with CONd group (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Similar to the finding from the CLHd group, fecal dipeptide and polypeptide concentrations were lower in dogs fed CHd when compared with CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05) while the dietary peptides were higher in CHd.

Supplementary Tables S1-2 include more protein related metabolites for additional information.

Lipid and bile acid metabolism

There were some differences in the fatty acid metabolites in the plasma between dogs consuming CLHd and CONd (Table 5). Dogs fed CLHd had higher plasma arachidonate (20:4n6), docosapentaenoic acid (osbond acid; 22:5n6), Docosahexaenoate (DHA; 22:6n3), and cholesterol concentrations when compared with CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). On the other hand, there were lower plasma levels of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5n3) and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA; 22:5n3) in dogs from CLHd group than CONd group (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). There were also higher concentrations of plasma sphingolipids (such as sphingosine, N-stearoyl-sphingosine, lactosyl-N-nervonoyl-sphingosine, stearoyl sphingomyelin, sphingosine-1-phosphate, ceramide, and sphinganine) in dogs fed CLHd in contrast with CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05).

Some fatty acid metabolites were different in plasma samples between dogs consuming CHd and CONd (Table 5). There were lower plasma levels of EPA (20:5n3) and DPA (22:5n3) concentrations in the CHd group than CONd group (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). However, most changes were seen in plasma primary and secondary bile acid concentrations. For metabolites related to bile acid metabolism, dogs fed CHd had higher plasma cholesterol but were lower in both primary bile acids (cholate, chenodeoxycholate, taurochenodeoxycholate, beta-muricholate, and tauro-alpha-muricholate) and secondary bile acids (ursocholate, ursodeoxycholate, tauroursodeoxycholate, ketodeoxycholate, and dehydrocholate) than dogs fed CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Similar to the changes of sphingolipids in the CLHd group, there were higher concentrations of plasma sphingosine and sphinganine in dogs fed CHd in contrast with CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05).

Fecal metabolites related to lipid metabolism are listed in Table 6. Higher fecal eicosatrienoic acid (Mead acid; 20:3n9), DHA (22:6n3), docosapentaenoic acid (osbond acid; 22:5n6), glycerophosphorylcholine, cholesterol, and glycerol-3-phosphate were noted in dogs fed CLHd when compared with CONd (P < 0.05; q < 0.05).

Dogs consuming CHd had lower fecal EPA and higher fecal cholesterol in regard to CONd (Table 6; P < 0.05; q < 0.05). Considering fecal bile acid concentrations, there were lower levels of unconjugated bile acids (cholate, chenodeoxycholate, hyocholate, ursodeoxycholate, isoursodeoxycholate, dehydrocholate, and ketodeoxycholate) but higher levels of taurine conjugated bile acids (taurodeoxycholate and taurocholate) in CHd group than in CONd group (P < 0.05; q < 0.05).

Supplementary Tables S3-4 include more lipid related metabolites for additional information.

Discussion

The PCA plots showed separation among treatment groups in both plasma and fecal samples. This was unsurprising since previous studies with the same diets showed differences in standardized amino acid digestibility and selected fecal fermentative metabolites7,8. The random forest plots showed that the most determining compounds that contributed to treatment clustering were mostly from protein and lipid metabolism as well as some xenobiotics. This was not surprising as the main difference in the protein ingredients was the amino acid and lipid compositions. A previous study also demonstrated the modulatory effect of CLH on gut microbiota in dogs8; therefore, differences in xenobiotics, specifically metabolites from the microbial activity, in the present study also were expected.

Some changes in protein metabolites in the plasma were in accordance with the diet composition. For example, there were higher glutamate and its metabolites in the CLHd plasma as well as in the diet composition. This could indicate that the amino acids were absorbed into the body for utilization. Glutamate is the fuel source of various cells, an excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, and a precursor of antioxidant glutathione; low glutamate level was also linked to stress and higher susceptibility to infections9. Therefore, the high plasma glutamate concentration could provide more energy and antioxidative capacity for the cells. Similarly, phenol sulfate, a downstream metabolite from tyrosine that is linked to renal disease and could lead to oxidative stress, was lower in concentration in CLHd diet, plasma, and feces than in CONd10,11. There were also higher pipecolate concentrations in both the diet and plasma from CLHd than CONd. It was reported by previous research that pipecolate exhibited antioxidative effects12. On the other hand, the CLHd diet was high in histidine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine but the plasma from CLHd was low in histidine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine when compared with CONd. This could indicate lower protein digestibility of the CLHd; however, this is unlikely since it was previously reported that the amino acid digestibility was comparable between CLHd and CONd7. Another explanation would be that the metabolism of these amino acids was higher in the CLHd group than in the CONd. The higher plasma imidazole propionate, a downstream metabolite from histidine, in the CLHd group could further support this hypothesis. Since the standardized amino acid digestibility of CLHd was comparable to CONd and higher than 80% for phenylalanine and tyrosine7, it could be suggested that phenylalanine and tyrosine were absorbed into the body and used for the production of needed catecholamines, resulting in a greater plasma concentration of dopamine 3-O-sulfate in the CLHd group. Some microbial fermentative product derivatives were also different between CLHd and CONd. Indole propionate, produced from the microbial metabolism of tryptophan, was low in the CLHd diet but higher in the CLHd plasma and feces. The higher tryptophan concentration from the CLHd diet could lead to this difference with the higher substrate supply to the microbes. Since indole propionate showed antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties in previous studies, the higher concentration in the plasma and feces could indicate CLH supported its production and, thus, providing a higher capability against oxidative stress and inflammation in healthy animals13.

Differences in the fecal protein metabolite concentrations in the current study were expected as a previous study showed higher fecal butyrate with lower isovalerate and total phenol/indole in dogs fed the CLHd than CONd, which also corresponded with the microbiota differences8. The lower fecal 5-aminovalerate, pipecolate, and 2-aminoadipate from lysine degradation in the CLHd group when compared with the CONd could be due to the less substrate entering the hindgut for fermentation14,15. This would support the finding that the plasma 5-aminovalerate level was lower in the CLHd group as well. The higher fecal spermidine and spermine from ornithine in the CLHd group could mean more protection from oxidation as they previously demonstrated antioxidative properties16,17. Previous studies have shown spermidine extended lifespan and health span in different species; therefore, the finding in the present study could indicate that hydrolyzed protein would support health in animals under oxidative stress18,19,20. Higher fecal betaine, cystathionine, and cysteine from methionine metabolism could indicate a sufficient supply of dietary methionine from the CLHd since excessive methionine not incorporated in protein converts to S-adenosylmethionine in the first step of catabolism and then to other products21. In addition, cysteine is known to be the precursor of antioxidant glutathione22. Therefore, the higher concentrations of downstream metabolites from methionine could be an indication of higher antioxidative capability from consuming the CLHd. In concert, lower fecal succinate concentration was found in the CLHd when compared with CONd. It has been reported that reducing the accumulation of succinate by altering the gut microbiota could reduce inflammation in animals23,24,25.

Even though there were higher concentrations of peptides and indispensable amino acids in the CLHd and CHd diets than in the CONd, the fecal concentrations of peptides and indispensable amino acids were lower. This indicated the higher digestibility of amino acids in the hydrolyzed proteins. The finding corresponded with the higher standardized amino acid digestibility of the test hydrolyzed proteins than CM from a previous study using a precision-fed rooster assay7. In addition, fecal metabolites from amino acid fermentation were also low in the CHd group. This could further support the hypothesis that fewer amino acids were available to enter the large intestine for microbial degradation from hydrolyzed proteins. The gut microbiota could also favor incorporating the available amino acids into microbial proteins over fermenting the substrates for energy and, thus, resulting in fewer degradation products. In addition, it was previously reported that amino acid composition could affect the rate of protein degradation26; therefore, the different compositions among the protein ingredients could also be a cause of this observation. Urea, one of the markers for protein degradation, could be found higher in concentration with high-protein diets and is toxic at high levels27,28. Therefore, a lower urea level from the CLHd could be beneficial to the dogs, especially those consuming higher levels of dietary protein.

The finding of differences in concentrations of arachidonate, cholesterol, osbond acid, mead acid, sphingolipids, and glycerol-3-phosphate in plasma and/or fecal samples could be the direct result of the amount of nutrients that were ingested. Both arachidonate and osbond acid are omega-6 fatty acids which are important fatty acids that support skin and coat health; however, the ratio between omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acid intake should be monitored as excessive omega-6 fatty acids could cause a rise in inflammatory responses29,30. Mead acid, an omega-9 polyunsaturated fatty acid, is usually a minor fatty acid in healthy individuals but could increase in concentration when essential fatty acids are deficient31. Nonetheless, excessive or deficient essential fatty acids should not be a problem in the current study since all diets were formulated to be complete and balanced. It was also reported that dietary supplementation of mead acid could decrease inflammation since it is an arachidonic acid analog32. Glycerol-3-phosphate is at the crossroads of different macronutrient metabolism pathways and serves as the backbone of most glycerolipids33,34. The higher glycerol-3-phosphate concentration could indicate more abundant substrates for lipogenesis in dogs fed CLHd than CONd. Sphingolipids have been studied for their roles in the immune, cardiovascular, and nervous systems; though the mechanisms of sphingolipid regulation have yet to be deciphered, sphingolipids were reported to be crucial for normal inflammatory responses in cell and in vivo studies35.

The most notable difference in lipid metabolites between CHd and CONd groups was the bile acid metabolism. The main function of bile acids is to help with lipid digestion and absorption in the intestine36. Animals can produce primary bile acids in the liver and microbes can use the primary bile acids to produce secondary bile acids. Dogs consuming CHd had lower plasma primary and secondary bile acids than the CONd. This was interesting because plasma cholesterol, the precursor of bile acids, was higher in CHd than in CONd. Therefore, it was not the lack of substrates that resulted in lower bile acid levels. Even though high or low circulating bile acid concentrations that are out of the normal range are indications for diseases37,38, the dogs in the present study were all healthy and, thus, diseases should not be a concern. The lower plasma bile acid concentrations could mean a more efficient hepatic uptake in the CHd group, resulting in fewer bile acids entering systemic circulation. In the fecal samples, CHd showed higher concentrations of conjugated bile acids and lower unconjugated bile acids than CONd. In the body, most bile acids are conjugated to increase water solubility and become impermeable to cell membranes, allowing their high concentrations in the bile and small intestine36. However, when bile acids enter the large intestine, they undergo bacterial deconjugation and the unconjugated bile acids will be readily reabsorbed into the enterocytes and then the liver39. The lower unconjugated bile acids in CHd fecal samples could be an indication of more efficient reabsorption of bile acids in the hindgut. On the other hand, the higher conjugated bile acids could mean a less efficient deconjugation from the bacteria and a potential for more amino acid loss. However, since the plasma levels of taurine were not different between CHd and CONd, there should not be a concern for excessive taurine loss. The difference in conjugated and unconjugated bile acids excretion from the current study could be a result of modified gut microbiota from consuming the hydrolyzed protein. Another factor to acknowledge is the difference in fat content between the two diets, CHd and CONd, which could also contribute to the dissimilarity of lipid metabolism.

The plasma and fecal metabolites jointly showed the anti-inflammatory and antioxidative potentials of the test protein hydrolysate in healthy adult dogs. Previous in vitro and rodent studies also showed protein hydrolysates from chicken origin exhibited anti-inflammatory properties40,41,42and antioxidative effects43,44. Several canine studies also used metabolomics to observe anti-inflammatory and antioxidative functions from dietary treatments through indicators in blood and feces, such as methionine, glycine, polyamines, succinate, chenodeoxycholic acid, adenosine, linolenic acid23,45,46,47,48. A study by Lyu et al. (2022) aimed to determine the metabolomic profiles of healthy dogs fed a high-starch or high-fat diet45. Ambrosini et al. (2020) included dogs with inflammatory bowel disease and observed some serum biomarkers for the disease improved after administering a hydrolyzed diet47. Their findings in the correlation of metabolites and inflammation/oxidation showed corresponding results with the present study.

Conclusions

Protein hydrolysates made from mechanically separated chicken and chicken liver and heart influenced protein and lipid metabolism in healthy adult dogs. Both test proteins showed lower fecal peptides and amino acid metabolites than traditional CM, which could be an indication of higher digestibility. In addition, CLHd showed potential for anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties with changes in glutamate, cysteine, indole propionate, spermidine, pipecolate, phenol sulfate, and succinate. On the other hand, CHd demonstrated the potential to affect bile acid metabolism with lower circulating primary and secondary bile acid concentrations, higher fecal conjugated bile acids, and lower unconjugated bile acids excretion.

Materials and methods

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All methods were performed following the United States Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and ARRIVE guidelines.

Experimental diets

Three treatment diets were formulated to have similar ingredient compositions except for the main protein source (Table 1). The control diet was formulated with low ash chicken meal (CM) as the primary protein source and rice as the primary carbohydrate source. Chicken meal was chosen as the control because it has a good protein quality and is widely used in pet foods as a protein source. Test hydrolyzed proteins made from enzymatic hydrolysis, PROSURANCE® CHX Liver.HD (CLH) and PROSURANCE® CHX.HD (CH; Kemin Industries, Des Moines, IA), were used to substitute CM for the manufacturing of extruded diets for adult dogs. The ingredient CLH was hydrolyzed from chicken liver and heart; CH was hydrolyzed from mechanically separated chicken. The diets were as follows, (1) CONd: chicken meal diet; (2) CLHd: chicken liver and heart hydrolysate diet; (3) CHd: chicken hydrolysate diet. All diets were formulated to meet or exceed the AAFCO (2022)49recommendation for adult dog maintenance and were extruded at Wenger Pilot Plant in Sabetha, KS. The same diets were analyzed for amino acid profiles and protein quality in a previous study7.

Chemical analysis

All treatment diets were ground with a Wiley mini-mill (Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ) through a 2 mm screen. Dry matter, OM, AHF, CP, TDF, soluble and insoluble fiber, and gross energy were determined. Dry matter and ash content of the diets and ingredients were determined in duplicates according to AOAC (2007; methods 934.01 and 942.05)50. Total nitrogen values were determined according to AOAC (2007; method 992.15)50with CP calculated from Leco (TruMac N, Leco Corporation, St. Joseph, MI). Acid hydrolyzed fat was analyzed according to AACC (1983) and Budde (1952)51,52. Gross energy was determined through bomb calorimetry (Model 6200, Parr Instruments Co., Moline, IL). Total dietary fiber was analyzed according to Prosky et al. (1992)53. The complete amino acid profile was determined according to AOAC (2007)50.

Canine study and experimental design

Ten neutered adult beagles (females, mean age 4 ± 0.82 year, mean body weight 9 ± 0.64 kg, mean body condition score 5 ± 0.57) were included in the study with a replicated 3 × 5 Latin rectangle design. Only healthy adult dogs with ideal body condition score were included. Dogs were randomly assigned to 1 of the 3 treatment diets for each period so that all dogs received all diets once during the trial. At the beginning of each period, there was a 7 d wash-out in which all the dogs consumed the control diet. After the washout, there was a 28 d treatment period in which dogs were fed the assigned treatment diet. Fresh fecal collection was conducted at the end of the washout period (d 0) and the end of the treatment period (d 28). Fresh fecal samples were collected and processed to be stored within 15 min of defecation. Fasted blood samples were also collected at d 0 and 28. During collections, 2 mL of blood was placed in EDTA vacutainer tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and centrifuged to separate plasma. Both fecal and plasma samples were preserved at −80oC for metabolomics analysis.

The dogs were housed individually in kennels at Edward R. Madigan Laboratory (Urbana, IL) in a temperature-controlled room with a 14:10 (L: D) cycle, allowing nose-to-nose interaction with adjacent dogs and visual contact with all dogs. Feeding occurred twice a day at 08:00–10:00 and 15:00–17:00. Diets were weighed and recorded for each feeding. Dogs had free access to water at all times and were fed to maintain body weight. Both body weight and body condition scores were monitored weekly.

Metabolomics analysis

Preparation procedures were done with Microlab STAR Liquid Handling System (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV). Samples were prepared by adding 450 µL of methanol to 100 µL of sample. The mixture was shaken vigorously for 2 min and centrifuged for 10 min at 680 g. The supernatant was removed and divided into aliquots. The extracts were then placed briefly onto a TurboVap LV Evaporator (Zymark Corporation, Hopkinton, MA) to remove the organic solution. The dried sample extracts were reconstituted for testing using 4 different methods with compatible solvents54. One aliquot was analyzed using acidic positive ion conditions for more hydrophilic compounds from ACQUITY BEH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) with gradient elution using water, methanol, 0.05% perfluoropentanoic acid, and 0.1% formic acid. Another aliquot also used acidic positive ion conditions for more hydrophobic compounds with the same C18 column using methanol, acetonitrile, water, 0.05% perfluoropentanoic acid, and 0.1% formic acid. The third aliquot was analyzed using basic negative ion optimized conditions with a dedicated C18 column, using methanol, water, and 6.5 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The fourth aliquot was analyzed via negative ionization for polar compounds following gradient elution from ACQUITY BEH Amide column (2.1 × 150 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) using water and acetonitrile with 10mM ammonium formate. All samples were analyzed with ACQUITY ultra-performance liquid chromatography (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) and Q Exactive Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) interfaced with a heated electrospray ionization (HESI-II) probe (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) and Orbitrap mass analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) operated at 35,000 mass resolution.

Different types of controls or standards were used for quality control. A pooled matrix made from small volumes of each experimental sample served as a technical replicate and was injected periodically throughout the run. Purified water served as process blanks. Solvent blanks of extraction solvents were used to segregate contamination sources in the extraction. Recovery standards were used to assess variability and verify extraction and instrument performance. A mixture of standards were used to spike into every sample as internal standards for instrument performance monitoring. Compounds from samples were identified from the previously built library using commercially available standard compounds and quantified by area under the curve from peaks (Metabolon Inc., Durham, NC). The identifications were based on retention index, mass match, and the comparison of ions present in the experimental spectrum with the library spectrum. Statistical analysis was performed with Array Studio in Jupyter Notebook on log-transformed data. Paired t-test was used to compare treatment groups with statistical significance set at P-value less than 0.05 and false positive rate (q-value) less than 0.0555. Random forest plots were used as a supervised classification technique for classification and to determine which compounds had the largest contribution to the grouping of plasma and fecal samples56. Mean decrease accuracy was used to measure variable importance. Principal component analysis was also used to reduce the dimensions of the data in an unsupervised process and plots were generated to visualize possible separation among treatments.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kaddurah-Daouk, R., Kristal, B. S., Weinshilboum, R. M. & Metabolomics A global biochemical approach to drug response and disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 48, 653–683. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094715 (2008).

Cave, N. J. Hydrolyzed protein diets for dogs and cats. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 36, 1251–1268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.08.008 (2006).

Chai, T. T., Ee, K. Y., Kumar, D. T., Manan, F. A. & Wong, F. C. Plant bioactive peptides: current status and prospects towards use on human health. Protein Pept. Lett. 28, 623–642. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929866527999201211195936 (2021).

Jo, C., Khan, F. F., Khan, M. I. & Iqbal, J. Marine bioactive peptides: types, structures, and physiological functions. Food Rev. Int. 33, 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2015.1137311 (2017).

Bhat, Z. F., Kumar, S. & Bhat, H. F. Bioactive peptides of animal origin: a review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 52, 5377–5392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-015-1731-5 (2015).

Haque, E., Chand, R. & Kapila, S. Biofunctional properties of bioactive peptides of milk origin. Food Rev. Int. 25, 28–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/87559120802458198 (2009).

Hsu, C. et al. Standardized amino acid digestibility and protein quality in extruded canine diets containing hydrolyzed protein using a precision fed rooster assay. J. Anim. Sci. 101, skad289. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skad289 (2023).

Hsu, C., Marx, F., Guldenpfennig, R. & de Godoy, M. R. C. The effects of hydrolyzed protein on macronutrient digestibility, fecal metabolites and microbiota, oxidative stress and inflammatory biomarkers, and skin and coat quality in adult dogs. J. Anim. Sci. 102, skae057. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skae057 (2024).

Matés, J. M., Pérez-Gómez, C., De Castro, I. N., Asenjo, M. & Márquez, J. Glutamine and its relationship with intracellular redox status, oxidative stress and cell proliferation/death. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 34, 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00143-1 (2002).

Kikuchi, K. et al. Metabolomic search for uremic toxins as indicators of the effect of an oral sorbent AST-120 by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 878, 2997–3002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.09.006 (2010).

Kikuchi, K. et al. Gut microbiome-derived phenyl sulfate contributes to albuminuria in diabetic kidney disease. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09735-4 (2019).

Pietzner, M. et al. Comprehensive metabolic profiling of chronic low-grade inflammation among generally healthy individuals. BMC Med. 15, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0974-6 (2017).

Negatu, D. A., Gengenbacher, M., Dartois, V. & Dick, T. Indole propionic acid, an unusual antibiotic produced by the gut microbiota, with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.575586 (2020).

Barker, H. A., D’Ari, L. & Kahn, J. Enzymatic reactions in the degradation of 5-aminovalerate by Clostridium aminovalericum. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 8994–9003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)48036-2 (1987).

Barker, H. A. Amino acid degradation by anaerobic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 50, 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.000323 (1981).

Madeo, F., Bauer, M. A., Carmona-Gutierrez, D. & Kroemer, G. Spermidine: a physiological autophagy inducer acting as an anti-aging vitamin in humans? Autophagy 15, 165–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2018.1530929 (2019).

Pegg, A. E. Mammalian polyamine metabolism and function. IUBMB Life. 61, 880–894. https://doi.org/10.1002/iub.230 (2009).

Eisenberg, T. et al. Cardioprotection and lifespan extension by the natural polyamine spermidine. Nat. Med. 22, 1428–1438. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4222 (2016).

Gupta, V. K. et al. Restoring polyamines protects from age-induced memory impairment in an autophagy-dependent manner. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1453–1460. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3512 (2013).

Matsumoto, M., Kurihara, S., Kibe, R., Ashida, H. & Benno, Y. Longevity in mice is promoted by probiotic-induced suppression of colonic senescence dependent on upregulation of gut bacterial polyamine production. PLoS One. 6, e23652. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023652 (2011).

Tessari, P. et al. Effects of insulin on methionine and homocysteine kinetics in type 2 diabetes with nephropathy. Diabetes 54, 2968–2976. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2968 (2005).

Lu, S. C. Glutathione synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1830, 3143–3153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.008 (2013).

Yang, K. et al. Fecal microbiota and metabolomics revealed the effect of long-term consumption of gallic acid on canine lipid metabolism and gut health. Food Chem. X. 15, 100377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100377 (2022).

Geng, T. et al. Probiotics Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG ATCC53103 and Lactobacillus plantarum JL01 induce cytokine alterations by the production of TCDA, DHA, and succinic and palmitic acids, and enhance immunity of weaned piglets. Res. Vet. Sci. 137, 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2021.04.011 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Green tea polyphenols decrease weight gain, ameliorate alteration of gut microbiota, and mitigate intestinal inflammation in canines with high-fat-diet-induced obesity. J. Nutr. Biochem. 78, 108324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.108324 (2020).

Chang, R. L. et al. Protein structure, amino acid composition and sequence determine proteome vulnerability to oxidation-induced damage. EMBO J. 39, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2020104523 (2020).

Ephraim, E., Cochrane, C. Y. & Jewell, D. E. Varying protein levels influence metabolomics and the gut microbiome in healthy adult dogs. Toxins (Basel). 12, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12080517 (2020).

Weiner, I. D., Mitch, W. E. & Sands, J. M. Urea and ammonia metabolism and the control of renal nitrogen excretion. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 1444–1458. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.10311013 (2015).

Calder, P. C. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammation. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids. 75, 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2006.05.012 (2006).

Vaughn, D. M. et al. Evaluation of effects of dietary n-6 to n-3 fatty acid ratios on leukotriene B synthesis in dog skin and neutrophils. Vet. Dermatol. 5, 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3164.1994.tb00028.x (1994).

Cleland, L. G. et al. Effect of dietary n-9 eicosatrienoic acid on the fatty acid composition of plasma lipid fractions and tissue phospholipids. Lipids 31, 829–837 (1996).

James, M. J., Gibson, R. A., Neumann, M. A. & Cleland, L. G. Effect of dietary supplementation with n-9 eicosatrienoic acid on leukotriene B4 synthesis in rats: a novel approach to inhibition of eicosanoid synthesis. J. Exp. Med. 178, 2261–2265. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.178.6.2261 (1993).

Jensen, M. D., Ekberg, K. & Landau, B. R. Lipid metabolism during fasting. Am. J. Physiol. – Endocrinol. Metab. 281, E789–E793. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.4.E789 (2001).

Lin, E. C. C. Glycerol utilization and its regulation in mammals. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 46, 765–795. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.004001 (1977).

Hannun, Y. A. & Obeid, L. M. Sphingolipids and their metabolism in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm.2017.107 (2018).

Hofmann, A. F., Hagey, L. R. & Krasowski, M. D. Bile salts of vertebrates: structural variation and possible evolutionary significance. J. Lipid Res. 51, 226–246. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R000042 (2010).

Nguyen, C. C. et al. Circulating bile acids concentration is predictive of coronary artery disease in human. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02144-y (2021).

Pena-Ramos, J. et al. Resting and postprandial serum bile acid concentrations in dogs with liver disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 35, 1333–1341. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.16134 (2021).

Dawson, P. A. & Karpen, S. J. Intestinal transport and metabolism of bile acids. J. Lipid Res. 56, 1085–1099. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R054114 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Chicken collagen hydrolysate reduces proinflammatory cytokine production in C57BL/6.KOR-ApoE mice. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 56, 208–210. https://doi.org/10.3177/jnsv.56.208 (2010).

Fan, H., Liao, W., Spaans, F., Davidge, S. T. & Wu, J. Chicken muscle hydrolysate reduces blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats, upregulates ACE2, and ameliorates vascular inflammation, fibrosis, and oxidative stress. J. Food Sci. 87, 1292–1305. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.16077 (2022).

Chen, P. J. et al. Protective effects of functional chicken liver hydrolysates against liver fibrogenesis: antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and antifibrosis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65, 4961–4969. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01403 (2017).

Fukada, Y. et al. Antioxidant activities of a peptide derived from chicken dark meat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 53, 2476–2481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-016-2233-9 (2016).

Chou, C. H., Wang, S. Y., Lin, Y. T. & Chen, Y. C. Antioxidant activities of chicken liver hydrolysates by pepsin treatment. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 49, 1654–1662. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.12471 (2014).

Lyu, Y. et al. Differences in metabolic profiles of healthy dogs fed a high-fat vs. a high-starch diet. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2022.801863 (2022).

Xin, G. et al. Dietary supplementation of hemp oil in teddy dogs: Effect on apparent nutrient digestibility, blood biochemistry and metabolomics. Bioengineered 13, 6173–6187. https://doi.org/10.1080/21655979.2022.2043018 (2022).

Ambrosini, Y. M. et al. Treatment with hydrolyzed diet supplemented with prebiotics and glycosaminoglycans alters lipid metabolism in canine inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00451 (2020).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Serum metabolic profiling reveals potential anti-inflammatory effects of the intake of black ginseng extracts in beagle dogs. Molecules 25, 3759. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25163759 (2020).

Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO). Official Publication (AAFCO, 2022).

Association of Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Official Methods of Analysis 17th edn (AOAC, 2007).

American Association of Cereals Chemists (AACC). Approved Methods of the AACC (AACC, 1983).

Budde, E. F. The determination of fat in baked biscuit type of dog foods. J. AOAC. 35, 799–805 (1952).

Prosky, L., Asp, N. G., Schweizer, T. F., Devries, J. W. & Furda, I. Determination of insoluble and soluble dietary fiber in foods and food products: collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 75, 360–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaoac/75.2.360 (1992).

Evans, A. M. et al. High resolution mass spectrometry improves data quantity and quality as compared to unit mass resolution mass spectrometry in high-throughput profiling metabolomics. Metabolomics 4, 132. https://doi.org/10.4172/2153-0769.1000132 (2014).

Storey, J. D. & Tibshirani, R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 100, 9440–9445. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1530509100 (2003).

Breiman, L. & Random, F. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010950718922 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank Kemin Industries, Inc. for the financial support of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H. conducted the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. F. M., R. G., and M. R. C. G. designed the study. M. R. C. G. supervised the execution of the study. All authors revised and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hsu, C., Marx, F., Guldenpfennig, R. et al. The effects of chicken hydrolyzed proteins in extruded diets on plasma and fecal metabolic profiles in adult dogs. Sci Rep 14, 31620 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80176-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80176-w