Abstract

Mothers encounter several challenges to sustain breastfeeding until the recommended 6 months of age. There is limited evidence on the impact of women’s labor pain experiences upon cessation of breastfeeding. We aimed to investigate the association between women’s labor pain experiences, intrapartum interventions, and pre-birth psychological vulnerabilities and cessation of breastfeeding. This was a secondary analysis of a clinical trial conducted in a tertiary hospital in Singapore between June 2017 and July 2021. Data were obtained from participants, electronic records and surveys administered before delivery, and postpartum 6–10 weeks. A total of 624 (76.8%) women were still breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks as compared to 189 (23.2%) that had discontinued breastfeeding. Multivariable regression analysis identified lower education level (aOR 3.88, 95% CI 2.57–5.85, p < 0.0001), having diabetes (aOR, 95% CI 1.21–5.44, p = 0.0141), presence of obstetric complications (aOR 1.57, 95% CI 1.00–2.46, p = 0.0494), artificial rupture of membrane (ARM) and oxytocin induction (aOR 2.07, 95% CI 1.22–3.50, p = 0.0068), lower age (aOR 0.92, 95% CI 0.88–0.97, p = 0.0010) and higher A-LPQ birth pain score (aOR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.04, p = 0.0064) as independent associations with cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks, with AUC of the model being 0.72 (95% CI 0.68–0.77). Higher pain experienced during labor is associated with cessation of breastfeeding among several other intrapartum interventions and psychological vulnerabilities. Using risk stratification strategy, breastfeeding support services could be provided to women to optimize successful breastfeeding in the postpartum period.

Trial registration: This study was registered on Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03167905 on 30/05/2017.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for infants in the first 6 months of life, and continued breastfeeding for up to 2 years of age and beyond with introduction of complementary solid foods after 6 months1. Apart from providing the infant with the essential nutrition and supporting growth and development, breastfeeding has also been recognized as an effective measure to decrease infant mortality and morbidity including obesity and chronic diseases later in adulthood2,3. For the mother, breastfeeding may reduce the risk of breast and ovarian cancer and type 2 diabetes4.

The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) was subsequently introduced to Singapore in 2010 to promote exclusive breastfeeding by providing mothers with access to the peripartum resources and support5. Despite these efforts to support breastfeeding, mothers continue to encounter challenges to sustain breastfeeding until the recommended 6 months of age, likely impacted by numerous demographic, physical, social and psychological factors6,7. Likewise, women’s pain experiences after caesarean section have been reported by women to be associated with difficult breastfeeding which contributed to cessation of breastfeeding8. Studies have also investigated the association between the labor pain management and experience with breastfeeding, however, varying and contradictory findings have been reported9,10,11. A systematic review of 15 randomized controlled trials studying the effect of neuraxial labor analgesia and long-term breastfeeding outcomes showed mixed results11. Other factors including intrapartum interventions such as induction of labor or use of oxytocin infusion have been reported to result in more adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes12. However, the effect of such interventions upon long-term breastfeeding outcome were limited due to the lack of breastfeeding measures used beyond the early postpartum period13. There is still limited evidence in aspects of ante- and intra-partum factors as research has primarily focused on the postpartum barriers related to breastfeeding such as nipple soreness.

Other aspects which could potentially interfere with the ability to maintain breastfeeding include psychological factors such as anxiety and depression. Though studies have reported associations between antenatal depression and breastfeeding14,15,16, other psychological vulnerabilities such as prenatal anxiety on breastfeeding duration have shown mixed evidence. Limited studies such as Nagel et al. have investigated other possible psychological vulnerabilities specific to pain-related fear and anxiety, and pain vulnerability such as pain-catastrophizing and central sensitization, which could offer novel insights to the associations between pain experiences of laboring women and cessation of breastfeeding17. Hence, this study aimed to investigate the association between women’s labor pain experiences using the angle labor pain questionnaire (A-LPQ), a multi-dimensional questionnaire validated in the use of assessment of labor pain18, and cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. We also examined the effect of other intrapartum interventions and psychological vulnerabilities upon the breastfeeding outcomes at postpartum 6–10 weeks.

Methods

This study was a secondary analysis of a clinical trial that investigated the association between the use of labor epidural analgesia and postpartum depression at postpartum 6–10 weeks. The primary study and secondary analysis were approved by SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board (Reference number: 2017/2090) on 25 March 2017 and was registered on Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03167905) on 30 May 2017. The primary study was conducted between June 2017 and July 2021. This study design was developed according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

The study was conducted in KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, a tertiary hospital in Singapore that provides specialized obstetric, gynecological, and pediatric medical care. It has been accredited as a Baby-Friendly Hospital since 2014 and is the largest maternity facility in Singapore and one of the largest in Southeast Asia, with about 11,000 births yearly19. The study population included healthy (American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status 2) adult parturients at term with a singleton fetus of any parity. All parturients meeting the inclusion criteria were recruited into this study irrespective of their intention for postpartum breastfeeding. Any parturient who had multiple pregnancies, non-cephalic fetal presentation, obstetric complications (e.g., pre-eclampsia, premature rupture of amniotic membranes for more than 48 h, gestational diabetes mellitus on insulin), uncontrolled medical conditions or undergoing planned elective caesarean births were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the primary study, and this included the consenting to the online/phone survey at postpartum 6–10 weeks to assess the status of breastfeeding.

Patients admitted to the pre-delivery rooms/wards or delivery suite with a pain score of 3 or less (out of 10 using numerical rating scale) were screened and approached for the study. Upon recruitment, study surveys on pain and psychological vulnerabilities were administered before birth, including:

-

1.

Angle labor pain questionnaire (A-LPQ): Labor pain experience was evaluated via A-LPQ, a condition-specific, multidimensional psychometric questionnaire that has been validated in assessing women’s pain experience during childbirth18. The A-LPQ contains five subscales to measure the most important dimensions of women’s childbirth pain experiences, including the enormity of pain, fear/anxiety, uterine contraction pain, birthing pain and back pain/long haul. Each subscale includes descriptors to allow the patient to better describe the pain and intensity of experienced labor pain. The subscale on Enormity of Pain includes the following descriptors—sickening, miserable, killing, blinding, and punishing. The Fear/Anxiety subscale includes fearful, apprehensive, surprising, and fear of pain. The Uterine Contraction Pain subscale includes tightening, aching, squeezing, and pressing. The Birthing Pain subscale includes stinging, stretching, tearing, and ring of fire. Finally, the Back Pain/Long haul subscale includes the following descriptors—overwhelming, exhausting, intense, back pain during contractions, and back pain between contractions18. It has been shown to demonstrate good test–retest reliability, trivial to moderate sensitivity to change, along with a high responsiveness to minimal changes in pain. It is also moderately correlated with other pain scores scales17. In this study, A-LPQ was only filled in after the patient experienced labor pain;

-

2.

Pain catastrophizing scale (PCS): Pain catastrophizing refer to the negative thoughts processes one would have when she is exposed to pain or painful experiences. The PCS comprises 13 items of three components on a five-point scale—rumination, magnification, and helplessness. Rumination refers to how often a patient thinks about pain. Magnification refers to how much a patient worries about pain and helplessness refers to how much a patient feels that they cannot cope with the pain20. It is a widely used self-report tool to quantify an individual’s pain experience by asking how they feel and what they think about when they are in pain. A score of 30 and above indicates a clinically significant level of catastrophizing20;

-

3.

Central sensitization inventory (CSI): The CSI is a 25-item screening instrument designed to identify those with central sensitization measuring a full array of central sensitization syndrome related symptoms rated on a Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always)21. The total possible score is 100, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of self-reported symptomatology;

-

4.

Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS): The EPDS is a screening tool for postnatal depression, which was included as an outcome for psychological vulnerability. It is a 10-item self-report scale, with each response given a score of 0–3. In this study, an EPDS score of 10 or more indicates presence of distressing symptoms that may be discomforting22;

-

5.

Fear-avoidance components scale (FACS): The FACS is a self-reported scale to evaluate fear-avoidance in patients with painful conditions23. It consists of 20 important fear-avoidance related items on cognitive, behavioral, and affective elements. The items are scored on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree) with a total score of up to 100, of which higher scores imply greater degree of fear-avoidance;

-

6.

Spielberger state trait anxiety inventory (STAI): The STAI consisted of two subscales on state and trait anxiety, each containing 20 items on a four-point rating scale24. The total scores range from 20 to 80, with a total score of over 60 suggesting severe anxiety;

-

7.

Perceived stress scale (PSS): PSS is a 10-item questionnaire used to assess the individual’s perception of stress during the period of assessment. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (almost always)25. The total score ranges from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress;

Pre-birth baseline demographic and obstetric characteristics were obtained from the participants and electronic records. We also collected post-birth clinical maternal and neonatal outcomes such as duration of first stage of labor, duration of second stage of labor, umbilical cord pH (if clinically indicated), Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min and obstetric or neonatal complications. The analgesic options were detailed in an information sheet as per routine in the study setting. At postpartum 6–10 weeks, the patient would receive phone survey/online survey on a modified breastfeeding survey from Tan et al. that consisted of questions on the use of breastfeeding support services and the reasons for cessation of breastfeeding26.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome is from the question “Are you still breastfeeding your baby?” that was treated as binary data with categories of “ongoing breastfeeding” or “cessation of breastfeeding”. Demographic, clinical, self-reported questionnaires, obstetric, and anesthetic data were summarized as mean with standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, and frequency (proportion) for categorical variables. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression models were used to identify possible risk factors of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. Associations drawn from the logistic regression models were characterized using ORs with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Variables with p values < 0.15 in the univariate analysis and clinically important variables were selected for the multivariable logistic regression model. Final multivariable model was decided using stepwise variable selection were used to finalize the list of variables in the model with entry and stay criteria as 0.2 and 0.05 respectively. Likelihood ratio test followed by area under the curve (AUC) was then used to determine the final multivariate model. The variables identified in the multivariate analysis were further analyzed for the strength of their associations to the likelihood of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks through a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. AUC from ROC was also reported. The significance level was set at 0.05 and all tests were two-tailed. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC, USA).

Results

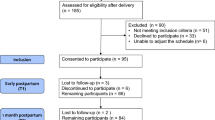

A total of 881 participants were enrolled into the study, of which one participant withdrew due to change of mind to study participation. Sixty-seven participants were lost to follow-up and the study workflow is shown in Fig. 1.

Among the 813 participants who responded to the online survey, 624 (76.8%) were still breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks, while the remaining 189 (23.2%) of the participants had discontinued breastfeeding. The participant baseline demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were statistically significant differences in the age (p = 0.0005), ethnicities (p = 0.0099), occupation (p = 0.0014), education level (p < 0.0001), number of biological children before this pregnancy (p = 0.0123), and mood changes during menstrual period (p = 0.0066) between participants who discontinued breastfeeding and those who were still breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks.

Results from the self-reported questionnaires on pain and psychological vulnerabilities are shown in Table 2. There were statistically significant differences in the PCS magnification scores (p = 0.0402), STAI state anxiety (p = 0.0219), STAI trait anxiety (p = 0.0099), STAI total score (p = 0.0083), PSS total score (p = 0.0063), A-LPQ subscales (back pain/long haul (p = 0.0113), birthing pain (p = 0.0018), the enormity of the pain (p = 0.0086), and A-LPQ total score (p = 0.0156) between participants who discontinued breastfeeding and participants who were still breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks.

The analgesic, obstetric, and neonatal characteristics are shown in Table 3. There was a statistically significant difference in the gravida between participants who have discontinued breastfeeding compared to those who were still breastfeeding (p = 0.0074). There was no statistically significant difference in the cessation of breastfeeding amongst the different analgesic modalities (epidural, Entonox, pethidine, and remifentanil), obstetric, and neonatal characteristics.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression model to identify the factors associated with cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks are shown in Table 4. Univariate logistic regression analyses showed that higher value of A-LPQ subscale on back pain/long haul, A-LPQ subscale on birth pain, A-LPQ subscale on the enormity of the pain and A-LPQ summary score were associated with cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. Results also showed that age and education level were associated with the cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. Having received remifentanil and pethidine as labor analgesia, having had spontaneous labor onset, artificial rupture of membrane (ARM) and oxytocic, prostin induction and other modes as labor onset were associated with cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. Having medical and surgical complications such as impaired glucose tolerance test (GTT) and diabetes, having obstetric and other complications such as fetal anomalies, and having neonatal complication were also associated with cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks.

Multivariable regression analysis identified that lower education level (aOR 3.88, 95% CI 2.57–5.85, p < 0.0001), having diabetes (aOR 2.57, 95% CI 1.21–5.44, p = 0.0141), having obstetric and other complications (aOR 1.57, 95% CI 1.00–2.46, p = 0.0494), had ARM and oxytocin induction (aOR 2.07, 95% CI 1.22–3.50, p = 0.0068), age (aOR 0.92, 95% CI 0.88–0.97, p = 0.0010) and A-LPQ birth pain score (aOR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.04, p = 0.0064) as independent associations with discontinuing breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks (Table 4). The AUC of these six independent association factors was 0.72 (95% CI 0.68–0.77).

Participants were surveyed on the use of support services on breastfeeding or giving breast milk to baby at postpartum 6–10 weeks and results are shown in Table 3. Participants who were still breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks were more likely to have received help from lactation consultants during hospital stay (p = 0.0017), contacted the lactation consultant (p = 0.0316), and used the Breastfeeding Mothers Support Group helpline (p = 0.0295) as compared to participants who discontinued breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. The most common reasons for introducing infant formula for participants who were still breastfeeding were insufficient milk supply (n = 276, 83.4%), feeding difficulty (latching problem) (n = 89, 26.9%) and fatigue/tiredness and sore nipples (n = 78, 23.6%). The most common reasons for stopping breastfeeding were insufficient milk supply (n = 138, 73.0%), fatigue/tiredness (n = 62, 32.8%) and choose to stop breastfeeding (n = 52, 27.5%) (Table 5).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the association between women’s labor pain experiences during childbirth and the effect of other intrapartum interventions and psychological vulnerabilities on cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. The study identified independent associations between lower age, lower education level, having diabetes, having obstetric complications, having ARM and oxytocin induction, and higher A-LPQ birth pain score, with the cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks.

Our study found that there was no significant difference in the likelihood of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks amongst the different types of analgesia modalities used during labor (epidural, pethidine, remifentanil). However, participants who experienced worse birthing pain as determined by the A-LPQ were more likely to discontinue breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. Labor pain can be immense and when inadequately controlled, is associated with increased maternal and fetal stress. Increased maternal stress results in an increase in maternal cortisol and catecholamines, which result in uterine vasoconstriction and thus impair placental flow27. Reduced placental flow coupled with increased maternal lipolysis that occurs in stress can result in fetal metabolic acidosis28. This may result in poorer fetal outcomes, which can then affect breastfeeding initiation. Our findings were consistent with findings from recent studies29,30, which showed a negative correlation between increased intrapartum maternal stress and lactation and the sucking behavior of the neonate. While the study was small, further research should be done to investigate the relationship between maternal stress and its effects on cessation of breastfeeding.

Past research has shown varied findings on the effect of oxytocic usage during labor on breastfeeding outcomes31,32. Our study found that having ARM and oxytocin induction was associated with the cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. Aside from mediation of uterine contractions, oxytocin is also important for breastfeeding as the activation of oxytocin receptors in the myoepithelial cells in the breast results in milk ejection. The administration of synthetic oxytocin intrapartum may result in a decrease in maternal endogenous oxytocin via negative feedback mechanisms. This can result in a decreased level of maternal endogenous oxytocin postpartum affecting the ability to breastfeed. Furthermore, it is postulated that high doses of oxytocin infusions intrapartum may result in a desensitization of maternal oxytocin receptors33, further decreasing the likelihood of postpartum breastfeeding. Studies done on newborn’s Primitive Neonatal Reflexes also found that the exposure of oxytocin intrapartum were associated with the inhibition of neonatal reflexes required for breastfeeding such as suck, jaw jerk and swallowing34,35. Problems with maternal milk ejection and reduced neonatal breastfeeding reflexes can result in difficulty with breastfeeding resulting in postpartum cessation.

Our study showed that a younger age and lower education level were associated with cessation of breastfeeding which is consistent with other previous studies36,37,38. We also found that having medical complication such as diabetes and obstetric complications were associated with cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. This finding was consistent with past research, which have shown that birth complications may increase the risk of difficulties with breastfeeding39. The presence of complications in childbirth may also result in increased need for medical care of the newborn, limiting the ability of skin-to-skin in the immediate postpartum period40. According to WHO’s Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding, breastfeeding ideally should be initiated within 1 h of birth. Interruption of skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding initiation within the first hour are associated with reduced likelihood of breastfeeding41. Similarly, newborns of mothers with medical complications such as diabetes requires closer monitoring due to the higher risk of developing hypoglycemia42. Separation of the newborn from the mother has been reported to be associated with reduced breastfeeding initiation and continuation43. Research has also found that mothers with diabetes have a shorter breastfeeding duration44. These could plausibly explain the association between having diabetes and obstetric complications with the cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks.

In Singapore, the National Breastfeeding Survey45 reported that comparing between 2001 and 2011, exclusive breastfeeding rates at discharge from hospital increased from 28 to 50%, and that 21 to 40% at 6 months post-birth. However, the exclusive breastfeeding rates at 6 months post-birth remains low at 1%. In a more recent study by De Roza et al., it was found that the exclusive breastfeeding rate was 38.2% at 6 months postpartum46. Being a BFHI accredited hospital since 2014, our institution has implemented several support initiatives to encourage mothers to breastfeed. In our study, when comparing the use of support services on breastfeeding or giving breast milk to baby at postpartum 6–10 weeks, we found that participants who have used the support services from Lactation Consultant and Breastfeeding Mothers Support Group helpline were more likely to be still breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. This is consistent with the previous studies47,48 that have shown that breastfeeding education and support can effectively increase breastfeeding rates. Lactation Consultants receive extensive education and training and are a source support for women who are preparing, commencing, or sustaining breastfeeding in the postpartum period. Similarly, breastfeeding support helplines managed by breastfeeding counsellors provide an alternative source of support for mothers. Besides providing informational support through workshops, talks and public events, research have also shown that support groups have provided emotional and social support for breastfeeding mothers, which contributed to the continuation of breastfeeding49.

There are several limitations in this study. Firstly, potential confounders that could have affected the cessation of breastfeeding, such as preconceived intentions to breastfeed, as well as socio-demographic factors, social support, lifestyle habits (e.g., alcohol intake and smoking) were not collected and analyzed. Also, rather than specifically analyzing participants who were exclusively breastfeeding, we also categorized those with partial breastfeeding (feeding on breast milk and infant formula at the point of survey administration) as “still breastfeeding” at postpartum 6–10 weeks. This could have resulted in an overrepresentation of the participants who were still breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. Furthermore, our study included only participants who have completed all study activities of this study till the postpartum 6–10 weeks, which could have limited the generalizability of the findings. Lastly, the use of several lengthy questionnaires (e.g., STAI, CSI) could have potentially resulted in questionnaire fatigue in the participants, hence increasing the risk of reporting biases. Finally, although we found that having ARM and oxytocin induction was associated with the cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks, we did not further explore if the effect of intrapartum oxytocin infusion on the breastfeeding cessation follows a dose-dependent relationship.

Conclusion

We found that higher pain experienced during labor, sociodemographic profile (age, education), medical history (diabetes, obstetric complications), and intrapartum intervention are associated with cessation of breastfeeding at postpartum 6–10 weeks. With the increased use of intrapartum interventions, the findings of this study may also suggest the need to identify and provide closer monitoring to women undergoing such interventions during labor to avoid risk of early cessation of breastfeeding. Further measures could include providing more support services on breastfeeding to the patients identified as high-risk for cessation of breastfeeding to optimize breastfeeding outcomes in the postpartum period.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to institutional policy on data confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- A-LPQ:

-

Angle labor pain questionnaire

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- ARM:

-

Artificial rupture of membrane

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BFHI:

-

Baby-friendly hospital initiative

- CSI:

-

Central sensitization inventory

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh postnatal depression scale

- FACS:

-

Fear-avoidance components scale

- GTT:

-

Glucose tolerance test

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- IUGR:

-

Intra-uterine growth restriction

- LSCS:

-

Lower segment cesarean section

- OA:

-

Occiput anterior

- OP:

-

Occiput posterior

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCS:

-

Pain catastrophizing scale

- PROM:

-

Premature rupture of membranes

- PSS:

-

Perceived stress scale

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SLE:

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- STAI:

-

Spielberger state trait anxiety inventory

- STD:

-

Sexually transmitted disease

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations International Children’s Fund

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. Infant and Young Child Feeding. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding#:~:text=WHO%20and%20UNICEF%20recommend%3A,years%20of%20age%20or%20beyond. Accessed 8 Aug 2024 (2023).

Horta, B. L., Loret de Mola, C. & Victora, C. G. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Acta Paediatr. 104, 30–37 (2015).

McNiel, M. E., Labbok, M. H. & Abrahams, S. W. What are the risks associated with formula feeding? A re‐analysis and review. Birth 37, 50–58 (2010).

Dieterich, C. M., Felice, J. P., O’Sullivan, E. & Rasmussen, K. M. Breastfeeding and health outcomes for the mother-infant dyad. Pediatr. Clin. 60, 31–48 (2013).

World Health Organization. Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative—Revised, Updated and Expanded for Integrated Care. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43593/9789241594967_eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 8 Aug 2024 (2009).

Di Mattei, V. E. et al. Identification of socio-demographic and psychological factors affecting women’s propensity to breastfeed: An Italian cohort. Front. Psychol. 7, 1872 (2016).

Ku, C. M. & Chow, S. K. Factors influencing the practice of exclusive breastfeeding among Hong Kong Chinese women: A questionnaire survey. J. Clin. Nurs. 19, 2434–2445 (2010).

Bourdillon, K., McCausland, T. & Jones, S. The impact of birth-related injury and pain on breastfeeding outcomes. Br. J. Midwifery 28, 52–61 (2020).

Lee, A. I. et al. Epidural labor analgesia—Fentanyl dose and breastfeeding success: A randomized clinical trial. Anesthesiology 127, 614–624 (2017).

Lind, J. N., Perrine, C. G. & Li, R. Relationship between use of labor pain medications and delayed onset of lactation. J. Hum. Lact. 30, 167–173 (2014).

Heesen, P. et al. Labor neuraxial analgesia and breastfeeding: An updated systematic review. J. Clin. Anesth. 68, 110105 (2021).

Dahlen, H. G. et al. Intrapartum interventions and outcomes for women and children following induction of labour at term in uncomplicated pregnancies: A 16-year population-based linked data study. BMJ Open 11, e047040 (2021).

Jordan, S. et al. Associations of drugs routinely given in labour with breastfeeding at 48 hours: Analysis of the Cardiff births survey. BJOG 116, 1622–1632 (2009).

Cato, K. et al. Antenatal depressive symptoms and early initiation of breastfeeding in association with exclusive breastfeeding six weeks postpartum: A longitudinal population-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 49 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. The impact of antenatal depressive symptoms on exclusive breastfeeding intention: A moderating effect analysis. Midwifery 116, 103551 (2023).

Figueirido, B., Canario, C. & Field, T. Breastfeeding is negatively affected by prenatal depression and reduces postpartum depression. Psychol. Med. 44(5), 927–936 (2014).

Nagel, E. M. et al. Maternal psychological distress and lactation and breastfeeding outcomes: A narrative review. Clin. Ther. 44(2), 215–227 (2022).

Angle, P. et al. The angle labor pain questionnaire: Reliability, validity, sensitivity to change, and responsiveness during early active labor without pain relief. Clin. J. Pain 33, 132–141 (2017).

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital. Obstetrics. Perinatal Mortality Rates. https://www.kkh.com.sg/about-kkh/corporate-profile/clinical-outcomes/Pages/obstetrics.aspx. Accessed 10 Aug 2024 (2018).

Sullivan, M. J., Bishop, S. R. & Pivik, J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol. Assess. 7, 524 (1995).

Mayer, T. G. et al. The development and psychometric validation of the central sensitization inventory. Pain Pract. 12, 276–285 (2012).

Khanlari, S., Eastwood, J., Barnett, B., Naz, S. & Ogbo, F. A. Psychosocial and obstetric determinants of women signalling distress during Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) screening in Sydney, Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 1–4 (2019).

Neblett, R., Mayer, T. G., Hartzell, M. M., Williams, M. J. & Gatchel, R. J. The fear-avoidance components scale (FACS): Development and psychometric evaluation of a new measure of pain-related fear avoidance. Pain Pract. 16, 435–450 (2016).

Spielberger, C. D., Gonzalez-Reigosa, F., Martinez-Urrutia, A., Natalicio, L. F. & Natalicio, D. S. The state-trait anxiety inventory. Interam. J. Psychol. 5, 3–4 (1971).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 24, 385–396 (1983).

Tan, D. J. et al. Investigating factors associated with success of breastfeeding in first-time mothers undergoing epidural analgesia: A prospective cohort study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 13, 1–9 (2018).

Mbiydzenyuy, N. E., Hemmings, S. M. & Qulu, L. Prenatal maternal stress and offspring aggressive behavior: Intergenerational and transgenerational inheritance. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 16, 977416 (2022).

Reynolds, F. The effects of maternal labor analgesia on the fetus. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 24, 289–302 (2010).

Asimaki, E., Dagla, M., Sarantaki, A. & Iliadou, M. Main biopsychosocial factors influencing breastfeeding: A systematic review. Mædica 17, 955 (2022).

Karakoyunlu, Ö., Ejder Apay, S. & Gürol, A. The effect of pain, stress, and cortisol during labor on breastfeeding success. Dev. Psychobiol. 61, 979–987 (2019).

Fernandez-Canadas Morillo, A. et al. The relationship of the administration of intrapartum synthetic oxytocin and breastfeeding initiation and duration rates. Breastfeed. Med. 12, 98–102 (2017).

Monks, D. T. & Palanisamy, A. Oxytocin: At birth and beyond. A systematic review of the long-term effects of peripartum oxytocin. Anaesthesia 76, 1526–1537 (2021).

Odent, M. R. Synthetic oxytocin and breastfeeding: Reasons for testing an hypothesis. Med. Hypotheses 81, 889–891 (2013).

Marin Gabriel, M. A. et al. Intrapartum synthetic oxytocin reduce the expression of primitive reflexes associated with breastfeeding. Breastfeed. Med. 10, 209–213 (2015).

Olza Fernandez, I. et al. Newborn feeding behaviour depressed by intrapartum oxytocin: A pilot study. Acta Paediatr. 101, 749–754 (2012).

Neves, P. A. R. et al. Maternal education and equity in breastfeeding: Trends and patterns in 81 low- and middle-income countries between 2000 and 2019. Int. J. Equity Health 20, 20 (2021).

Avery, M., Duckett, L., Dodgson, J., Savik, K. & Henly, S. J. Factors associated with very early weaning among primiparas intending to breastfeed. Matern. Child Health J. 2, 167–179 (1998).

Liu, P., Qiao, LXu. F., Zhang, M., Wang, Y. & Binns, C. W. Factors associated with breastfeeding duration. J. Hum. Lact. 29, 253–259 (2013).

Brown, A. & Jordan, S. Impact of birth complications on breastfeeding duration: An internet survey. J. Adv. Nurs. 69, 828–839 (2013).

Mohammed, S., Abukari, A. S. & Afaya, A. The impact of intrapartum and immediate post-partum complications and newborn care practices on breastfeeding initiation in Ethiopia: A prospective cohort study. Matern. Child. Nutr. 19, e13449 (2023).

DiFrisco, E. et al. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding 2 to 4 weeks following discharge from a large, urban, academic medical center striving for baby-friendly designation. J. Perinat. Educ. 20, 28 (2011).

Alemu, B. T., Olayinka, O., Baydoun, H. A., Hoch, M. & Akpinar-Elci, M. Neonatal hypoglycemia in diabetic mothers: A systematic review. Curr. Pediatr. Res. 21, 42–53 (2017).

Cohen, S. S. et al. Factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and continuation: A meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. 203, 190–196 (2018).

Nguyen, P. T., Pham, N. M., Chu, K. T., Van Duong, D. & Van Do, D. Gestational diabetes and breastfeeding outcomes: A systematic review. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 31, 183–198 (2019).

Chua, L. & Win, A. M. Prevalence of breastfeeding in Singapore. Stat. Singap. Newsl. 10, 15 (2013).

De Roza, J. G. et al. Exclusive breastfeeding, breastfeeding self-efficacy and perception of milk supply among mothers in Singapore: A longitudinal study. Midwifery 79, 102532 (2019).

Kim, S. K., Park, S., Oh, J., Kim, J. & Ahn, S. Interventions promoting exclusive breastfeeding up to six months after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 80, 94–105 (2018).

Rollins, N. C. et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices?. Lancet 387, 491–504 (2016).

Chambers, A., Emmott, E. H., Myers, S. & Page, A. E. Emotional and informational social support from health visitors and breastfeeding outcomes in the UK. Int. Breastfeed. J. 18, 14 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Miss Sili Tan (Clinical Research Coordinator) and Miss Agnes Teo (Senior Clinical Research Coordinator) for their administrative support in this work.

Funding

Chin Wen Tan is supported by KKH Academic Medicine Research Start-Up Grant (ref no. KKH-AM/2022/01). Ban Leong Sng is supported by the National Medical Research Council (NRMC) Clinician Scientist award (ref no. CSAINV16may004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A.A. and M.Q.A: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. R.S.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. C.W.T.: Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. B.L.S.: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board (Reference number: 2017/2090) on 25 March 2017 and was registered on Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03167905) on 30 May 2017. Written informed consent was obtained from every patient by the investigators, and that this work was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayuby, N.A., Ang, M.Q., Sultana, R. et al. Investigating the association between labor pain and cessation of breastfeeding. Sci Rep 14, 31361 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82850-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82850-5