Abstract

Autonomous microgrids (ATMG), with green power sources, like solar and wind, require an efficient control scheme to secure frequency stability. The weather and locationally dependent behavior of the green power sources impact the system frequency imperfectly. This paper develops an intelligent, i.e., fuzzy logic-based sliding mode control (F-SMC) utilizing a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) type sliding surface to regulate the frequency of a wind-diesel generator-based ATMG system. A dynamic structure of the wind generator is designed to participate in the frequency support of the considered plant. The mastery of the F-SMC is analyzed over the conventional SMC (C-SMC) under load perturbation. This study used the artificial gorilla troop optimization (GTO) technique to tune the F-SMC parameters. The effectiveness of the GTO-tuned F-SMC frequency regulation (FR) scheme is compared with well-established particle swarm optimization (PSO) and grey wolf optimization (GWO) approaches under various scenarios such as load perturbations, governor dead band (GDB), generation rate constraint (GRC), higher/lower dimensions of ATMG, and wind speed variations. Finally, the proposed GTO-based F-SMC approach has been validated upon a standard IEEE-14 bus system and compared with recent techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and motivation

A microgrid (MG), or autonomous microgrid (ATMG) essentially, is a low-power rating electrical network where the power sources and consumers are close together. The ATMG is formed with renewable sources such as solar, wind turbine generators (WTG), energy storage systems (ESSs), and reliable sources such as diesel engine generators (DEGs) and loads1. Nowadays, MG penetrations into the energy sector are more due to the high cost of fossil fuels, improved power converters efficiency due to advancements in power electronics, and environmental conservation. However, numerous technological difficulties are prevalent at significant levels of MG penetration; frequency regulation (FR) is one among them2. The primary reason is that such MG consists of fewer generators, providing reserve power for FR.

Furthermore, the power converters isolate the MG’s power sources and conventional power grid system, reducing MG’s overall inertia. In the modern MG, converter-fed devices such as an electric vehicle (EV), high voltage DC system, and power electronic loads are incorporated, which further reduce the inertia of the power system3. Wind power (WP) is the most promising renewable source to meet worldwide electricity demand. WP is one of the proliferate segments of the power sector. The global wind report says that the present global WP capacity is 837 gigawatts, assisting the globe in avoiding almost 1.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide radiation annually4. The implementation of the wind energy-based ATMG focused primarily on attaining energy sustainability in isolated regions worldwide. Recently, the power system frequency of South Australia and the United Kingdom has been reduced to 47 Hz and 48.8 Hz, respectively, due to higher penetrations of wind power into their power network5. These occurrences show how difficult it is to maintain a steady frequency within the ATMG. WP intensifies MG frequency fluctuations. Based on the variable speed of operation of the WTG system, its classification is a constant speed generator with a fixed magnet i.e., PMSG and induction generator i.e., DFIG. However, previous studies addressed the numerous control approaches for the WTG to facilitate system frequency participation6. The sources of DFIG to participate in frequency control are DC-link capacitor, de-loading operation, and droop control. Based on these sources, inertial frequency control and primary FR7 are designed for wind systems. This study developed a detailed dynamic model of WTG to participate in a second frequency control scheme or load frequency control (LFC). To extract the maximum power from the WTG system, the tip speed ratio-based maximum power point tracking (MPPT) technique is employed.

Literature review

Frequency is an essential indicator of the power network’s balance of real power and load. The reason for frequency droop is loss of active power or inadequate active power in the MG and integration of intermittent renewables to the system. Large-frequency droop may lead to system failure and blackouts8. Frequency decline must be stopped to protect power systems from serious repercussions. In previous studies, many authors designed various control techniques to solve the LFC issue9. A classical LFC scheme is suggested based on the small signal stability approach of the ESS-incorporated hybrid ATMG. The classical LFC schemes cannot handle large perturbations caused by the higher penetrations of solar wind systems into the modern energy sector or the standalone operation of the ATMG10. Hence, soft computing-based, modern control theory-based, intelligent control or advanced LFC schemes were developed in the previous studies. Numerous soft computing techniques such as genetic algorithm11, particle swarm optimization (PSO)12, gorilla troop optimization (GTO)13,14, black widow algorithm15, imperialist competition technique16, grey wolf optimization (GWO)17, coyote optimization18, grasshopper algorithm19, opposition-based volleyball-premier league method20 were employed. The role-cited optimization techniques are used to tune the secondary or traditional controllers, such as integral (I), proportional-integral (PI), and PID. In the literature, modern control theory or robust LFC schemes such as H∞ controller21 and linear quadratic regulator14 are explored to solve the LFC issue. However, these control techniques required a system state matrix essential to design an effective control law.

The number of state variables required to implement the robust control law is more for the large-dimension power system, which is difficult for real-time system design. Therefore, fractional order control techniques have been investigated in past studies to address these issues. In22, a water cycle algorithm tuned fractional order control methodology is developed to overcome the LFC issue in the two-area renewable energy-based MG system. The recently published work proposes a robust and fast response control technique, i.e., SMC, to handle various uncertainties23. An adaptive event-triggered FR method with SMC is proposed for the multi-area energy sector24. In25, an advanced event triggered the SMC-based FR technique, which addressed the power system’s network-induced delay and sensor faults. In26,27, a self-tuned fuzzy logic-based FR is proposed to eliminate the system frequency fluctuations, and fuzzy logic-based wind power generation participated in the LFC scheme. In28, two SMC techniques are designed for isolated MG systems, one for smoothing the wind power fluctuations and another for secondary frequency control for the DEG system. In29, neural network-based SMC for FR was proposed to control the renewable energy sector frequency. The fundamentals of SMC30, selection sliding surface, and adaptive SMC have been briefed in31,32. In33, a PSO-based secondary controller, speed regulator, and PI-based pitch angle controllers are designed. The complete dynamic structure of the WTG system to participate in the LFC scheme is also described. In34, the recent application of SMC is designed for autonomous underwater vehicles based on atlantic salmon fish. In this work, a comparative study among the various types, such as PI, PD, and PID sliding surfaces, is conducted to design the control law of the SMC. In this study, a fuzzy logic-based SMC utilized PID sliding surface LFC approach is suggested to adjust the frequency of the ATMG under various practical cases. In recent studies, the performance and effectiveness of designed LFC schemes are validated upon the standard test systems like IEEE-14 bus and IEEE-39 bus systems35,36,37,38,39,40,41. An optimal control theory-based full-state feedback control scheme is designed and implemented to solve the LFC42 issue in diverse sources, including wind, hydro, thermal, and gas plants based on a multi-area power network43. A Recently developed barnacle mating optimizer is used to tune the filter-associated cascaded fractional order controller to solve the frequency stability and power fluctuation problems in multi-area MG systems44. The multi-area MG system consists of different power units such as solar, wind, diesel, fuel-cell, battery, and EVs. In45, the recently developed Jaya optimization technique tunes the fractional order controller with an integral tilt derivative LFC approach for the multi-MG systems. In the ATMG46 system, solving the LFC issue is challenging due to renewable sources, bi-directional loads, and distributed generators. The wild horse optimizer (WHO)47 emphasizes social behavior and adaptive mechanisms, promoting moderate exploration but sometimes getting trapped in local optima48. It incorporates the Lévy flights algorithm to improve the balance between exploration and exploitation, outperforming standard PSO49. However, WHO is less effective than GTO50 in avoiding local optima and achieving better global solutions. WHO’s adaptability makes it suitable for various optimization problems, but it may require fine-tuning for complex scenarios51. Its ability to balance exploration and exploitation is key to its moderate success52,53.

In previous studies, the conventional control approaches were employed to control the area control error of frequency and tie-line power of muti-area power networks54. These controllers fail to respond, and their ability degrades if the highly penetrated renewables are integrated into the system55. As a result, various robust control schemes and tuning the traditional controllers with meta-heuristic approaches are significant in the ATMG operation. Therefore, how to cope with the above issues motivates the present study. In this study, a fuzzy logic-based SMC utilized PID sliding surface LFC approach is suggested to adjust the frequency of the ATMG under various practical cases. The performance of the designed, i.e., GTO-tuned F-SMC with PID-type sliding surface FR scheme, is validated on the standard IEEE-14 bus system by taking various uncertainties.

Novelty and contributions

In comparison with previous studies, the important contributions of this work are as follows:

-

To develop the dynamic model of the LFC scheme with WTG, a sliding mode approach is proposed for the secondary LFC in the autonomous MG. Since the performance of the proposed controller depends on its sliding surface and its gains, an artificial gorilla troop optimization (GTO) is proposed for tuning the SMC controller coefficients.

-

The proposed control technique performance is further improved by designing both the SMC control laws, i.e., equivalent control law and switching control law, using the fuzzy logic technique.

-

The superiority of the GTO-tuned F-SMC frequency regulation scheme is compared with the PSO and GWO approaches under various practical conditions such as load perturbations, parametric variations, and impact of wind speed variations projected to the designed ATMG system.

-

The effectiveness of the suggested FR scheme is also validated upon the standard IEEE-14 bus system by taking various uncertainties.

The rest of the sections of this work are arranged as beneath: Section “System description” is system modeling and description, Section “Control strategy” is control strategy, extensive simulation and result discussion is discussed in Sect. “Results and discussion”; and the conclusion of this work is revealed in Sect. “Conclusion”.

System description

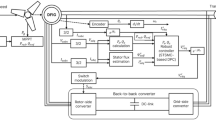

The proposed dynamic ATMG model shown in Fig. 1 incorporated a DEG system as a reliable energy source with DEG’s nonlinearities, such as governor dead band (GDB) and generation rate constraint (GRC). The DEG system is called a reliable system due to many advantages, such as quick start-up time, low maintenance requirements, long lifespan, and great efficiency. The main power source of ATMG is the renewable power WTG system. The modern power system operates based on four control loops: current/voltage loops of distributed power sources responsible for initial or local control. The global and emergency control strategies ensure the economic optimum, protection, and security, respectively. The main work of the LFC technique of the ATMG system is to handle power fluctuations (power mismatch) and enhance frequency stability. Hence, the dynamic model of the proposed ATMG is represented as follows24:

where, \(\:\varDelta\:f\) is the frequency deviations and M, and D is the inertia and damping coefficients of ATMG, respectively. The governor input and time constants of the DEG system are \(\:\varDelta\:{P}_{G}\), and \(\:{T}_{g}\), respectively. The turbine input and time constant of the DEG system are \(\:\varDelta\:{P}_{T}\), and \(\:{T}_{t}\) respectively. The output power of the DEG system is represented as \(\:{\varDelta\:P}_{DEG}\). The control signal \(\:u\) is generated from the suggested LFC method. \(\:{R}_{d}\) is the droop gain of the ATMG model. The load of the ATMG system is represented as \(\:{\varDelta\:P}_{L}\). The \(\:\:\varDelta\:{P}_{WTG}\) is wind power injected into the ATMG.

Structure and modeling of WTG system

The wind turbine aerodynamics, pitch angle control mechanism, and MPPT justification are important concerns in the model of WTG system participation in the LFC scheme. Figure 2 (a) represents the physical structure of the WTG system. The turbine, gearbox, and generator are the major physical components of the WTG system. The power output of the WTG depends upon the power coefficient or breadth coefficient (\(\:{C}_{P}\)) and other physical components. The mechanical output power \(\:\left({P}_{t}\right)\) from the wind turbine is described as follows:

The other components are \(\:\rho\:\) is the air density, \(\:{A}_{r}\) are blades swept the area in m2, \(\:{V}_{w}\) is the wind speed m/s. The wind turbine power is described as follows:

As shown in (5), \(\:{C}_{P}\) is the component of pitch angle (\(\:\beta\:\)), and tip-speed ratio \(\:\left(\lambda\:\right)\). The mathematical modeling of \(\:{C}_{P}\) in terms of aerodynamics, factors are defined as24:

where \(\:\frac{1}{{\lambda\:}_{i}}=\frac{1}{\lambda\:+{z}_{8}\beta\:}-\frac{0.035}{{\beta\:}^{3}+1}\), and the \(\:\lambda\:\) is defined as follows:

The \(\:{C}_{P}\) maximum is approximated as 0.593 due to \(\:{V}_{w}\) as well as physical and aerodynamic losses. The wind turbine’s normal speed is 6–20 rpm, which is much slower than the wind generator. The speed of the wind generator is 1500 and 1800 rpm for 50 Hz and 60 Hz, respectively. In this context, a gearbox is necessary to adapt the low-speed wind turbine to the high-speed wind generator. The gearbox conversion ratio (G) is the generator speed in rpm to wind turbine speed in rpm.

where \(\:f\) is supply frequency, \(\:p\) is number of poles. The \(\:G\) will be high at lower lower-rated turbine speed. The efficiency of the gearbox is approximately 96–98%. The maintenance and initial investment of the gearbox lead to a share significant cost contribution to the total cost of the WTG system (Tables 1 and 2).

It generates huge noise due to the meshing of the individual teeth. Figure 2 (b) reveals the WTG system’s mathematical model. The terms \(\:{J}_{t}\) and \(\:{J}_{g}\) are the movement of inertia of the WTG turbine and generator, respectively. \(\:{C}_{t}\) and \(\:{C}_{g}\) are turbine and generator torque, respectively.

The closed loop structure of the \(\:{C}_{g}\) and measured torque (\(\:{C}_{em}\)) is shown in Fig. 2 (c).

The WTG system’s detailed mathematical model and control method are explained in Fig. 3 of13,42. The specifications of the WTG system are shown in Table 3. Generally, the WTG system is associated with the Yaw control, β control, and \(\:{\uplambda\:}\) control. The orientation of the wind speed and change in the wind turbine head are the factors for the Yaw control system. In35, a wind-contributed LFC scheme is modeled. PSO tuned an additional PID controller, a PSO-tuned secondary controller, and a servomechanism-based PI-β control is presented. This work uses the same PI control technique for the β control. The main operating factor of β control is \(\:{V}_{w}\). Figure 3 represents the ideal characteristics of the β, output power of WTG, \(\:{\omega\:}_{t}\) at various \(\:{V}_{w}\). The β control is based on the three wind speed regions i.e., regions I to II and after IV represent the parking mode, regions II to III represent MPPT mode, and regions III to IV represent the operating mode (β control mode) of the WTG. The β is 90° in the region I to II and after region IV. In the region II to III (MPPT region) β is minimum or 00, and in the region III to IV β is 300-450 as shown in Fig. 3(a). In this region, the power output of the WTG system is constant as presented in Fig. 3(b). The corresponding \(\:{\omega\:}_{t}\) is depicted in Fig. 3(c).

MPPT justification

Two conditions need to be satisfied when WTG is working under peak power extraction. One condition is \(\:{\uplambda\:}\) maintained constant, irrespective of the \(\:{V}_{w}\). Here, the \(\:{V}_{w}\) variation up to the rated \(\:{V}_{w}\) as presented in Fig. 4(a) is applied to the system to demonstrate the maximum power extraction and its justification. The \(\:{\uplambda\:}\) is fixed irrespective of the \(\:{V}_{w}\) applied, and the pitch angle is maintained to be zero. Hence, the corresponding \(\:{\uplambda\:}\) and \(\:{C}_{P}\) is shown in Fig. 4(b) and (c) respectively.

The second condition is that the toque obtained with and without the MPPT loop must be equal, as revealed in Fig. 4(d). This condition strengthens the MPPT condition for obtaining peak power from the available wind speed. The β is zero in this case, as depicted in Fig. 4 (e). The \(\:{P}_{t}\left(max\right)\) can be represented as follows:

From Fig. 1, the \(\:{\varDelta\:P}_{WTG}\) can be represented as follows:

The \(\:{C}_{P\left(max\right)}\) is calculated at \(\:\lambda\:\) optimum (\(\:{\lambda\:}_{opt}\)).

Control strategy

The analytical controllers and stability analysis approaches like PI, PID, bode, root locus, etc., need a model to design the control law. There is a discrepancy between the model and the actual plant. In the case of a synthetic controller, theoretical stability is not guaranteed. Hence, robust control schemes like SMC are most popular in time domain analysis. The study of SMC has gained popularity in recent years as an effective technique to solve LFC issues in multi-area power systems25. The motion of the system trajectories along a chosen line/surface of the state space is called sliding mode. The control law is designed to achieve sliding mode. SMC has seen widespread application in the quest to enhance the efficiency, robustness, and stability of modern power system applications26,27. This section proposes a revolutionary fuzzy-based SMC using a PID sliding surface LFC control approach to support frequency and prevent power fluctuations. SMC methods have received significant research curiosity in RES-based MG systems due to their benefits of quick response speed and robust operation29.

Design of SMC

The building of the sliding surface \(\:\left(S\right)\), which is intended to respond to specified control parameters and performance, is known to be the most critical and vital step of SMC design. The trajectories are constrained to follow the paths of the sliding surfaces. The SMC is designed to achieve sliding mode. The SMC forces the error to reach a sliding surface and travel along the sliding surface in a fourth quadrant of a two-dimensional plane. The process for defining the sliding surface is flexible. There is no fixed law to select a sliding surface of a SMC. The SMC designer needs to follow some set of guidelines. The first guideline is that the sliding surface \(\:S\left(t\right)\) is equal to zero to make error zero as t reaches an infinite value. The second guideline is that the first derivative of sliding surface \(\:S\left(t\right)\) must contain the control signal \(\:u\). To design SMC, the small-signal dynamical model (1)-(3) of ATMG is considered and neglected the load and wind disturbances. The system dynamics are modeled based on the small signal model of DEG and the signal model of MG. Hence, the relationship between \(\:\varDelta\:f\) and \(\:u\) is as follows:

The simplified form of (14) can be written as:

where, \({a}_{2}=\left(\frac{M{T}_{g}+M{T}_{t}+D{T}_{g}{T}_{t}}{M{T}_{g}{T}_{t}}\right),\) \({a}_{1}=\left(\frac{M+D{T}_{g}+D{T}_{t}}{M{T}_{g}{T}_{t}}\right),\) \({a}_{0}=\left(\frac{D+1/{R}_{d}\:}{M{T}_{g}{T}_{t}}\right)\:\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\) \(K=\left(\frac{1\:}{M{T}_{g}{T}_{t}}\right)\).

To design an SMC technique, an error coordinate is defined as

The error is defined as the difference between the actual output state and desired state, \(\:t\) represents the time variable that will be omitted in the remainder of this section to keep things simple. Here, a PID-type sliding surface is selected as follows:

The error signal is considered as \(\:\varDelta\:f\). Where \(\:{k}_{p}\), \(\:{k}_{i}\), and \(\:{k}_{d}\) are the designer parameters. The lower and upper boundaries of these parameters are chosen based on the conventional control scheme called Ziegler–Nichols.

Theorem

For the system model (1) with the sliding surface (17), the error e(t) calculated by (16) delight if the control law is given by

Here, \(\:u\) is further simplified as follows:

the control law is defined as the sum of the equivalent control law \(\:\left({u}_{eq}\right)\) and switching control law \(\:\left({u}_{sw}\right)\)23,24,30. where \(\:sgn\left(.\right)\) indicates the signum function, and \(\:\eta\:\) is a positive

switching factor.

Proof

To design the, Lyapunov closed-loop stability analysis is utilized in this study. A positive definite Lyapunov function candidate is considered as follows:

Its first derivative can be expressed as:

Taking the time derivative of the sliding variable in (17), results in

where the time variable is omitted for the clarity of presentation. Lyapunov’s theory of stability states that the \(\:\dot{V}\) must be negative definite30. If \(\:\dot{V}\) is negative definite, then \(\:\dot{S}\) will be asymptotically stable as ∆f tends to zero and ‘t’ tends to infinite. So, the \(\:\dot{S}\) must be equal to zero. The term \(\:S\) is the sliding surface. The \(\:{u}_{sw}\) defined as the product of the switching factor (\(\:{\upeta\:}\)) and signum function, i.e., \(\:\text{s}\text{g}\text{n}\left(\cdot\:\right)\), which is as follows:

where \(\:sgn\left(S\right)=\left\{\begin{array}{c}-1,\:\:\:S<0\\\:0,\:\:\:S=0\\\:1,\:\:S>0\:\end{array}\right\}\). Therefore, the proposed PID sliding surface-based SMC method ensures a zero steady-state tracking error. Similarly, the control law for PI and PD sliding surfaces is designed. The \(\:\varDelta\:f\) considered an index to justify the selected sliding surface. Here, PI and PD sliding surfaces are compared with PID sliding surfaces in terms of \(\:\varDelta\:f\). A comparative analysis is conducted in terms of Δf with the help of the designed control laws. Figure 5 indicates that the maximum frequency deviation occurs, i.e., -0.32 Hz for the PI sliding surface, -0.27 Hz for the PD sliding surface, and − 0.18 Hz for the PID sliding surface. Hence, the PID sliding surface is selected for further analysis in this study. The GTO-based F-SMC utilizing a PID-type sliding surface is designed for secondary FR in the following sub-sections.

The control law designed for PI sliding surface is as follows:

The control law designed for PD sliding surface is as follows:

The reason for chattering in the control input is the discontinuity of the signum function \(\:sgn\left(S\right)\). The chattering effect is reduced with the boundary layer technique adopted by replacing the signum function in (18) with the saturation function with the representation as:

where \(\:\delta\:\) is the positive constant, which is the representative of the boundary layer thickness. \(\:\delta\:\) is considered based on chattering and tracking errors. In general, \(\:\eta\:\) the gain value or switching factor is typically optimized by the trial-and-error method since no universal technique is available yet.

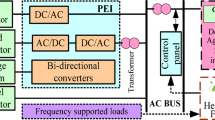

Proposed F-SMC using PID-type sliding surface

The traditional SMC design involves complex mathematical calculations, which can be computationally intensive. A lot of mathematical computations are required to design the equivalent control law \(\:\left({u}_{eq}\right)\) of the SMC, and the complexity will be greater in the SMC control law. Hence, the fuzzy logic-based SMC technique is proposed in this study. Traditional Boolean logic accepts only precise inputs (either 0 or 1), making it less flexible for handling real-world situations with uncertainty or noise. Fuzzy logic, on the other hand, can process imprecise, noisy, and distorted input signals. It assigns degrees of membership between 0 and 1 to input variables, allowing the system to manage uncertainty and operate smoothly even with imperfect information. The fuzzy logic reasoning is straightforward to design the fuzzy rules for the controller. The formation of the fuzzy rules is easy to construct, understand, and flexible. Fuzzy logic is used here to avoid these burdens, as it provides a simpler, more intuitive way to handle control rules. The control law structure comprises two essential components. The first component is the equivalent control law, which ensures that the system reaches and remains on the sliding surface. The second component is the switching control law, which is designed to minimize the chattering effect on undesirable high-frequency oscillation that can occur in the control system. The combination of the equivalent control law and the switching control law creates a robust control framework. The equivalent control law ensures that the system behaves as desired by driving it toward the sliding surface, while the switching control law enhances stability by smoothing control actions and minimizing undesirable oscillations. This dual approach enhances the overall performance and reliability of sliding mode control systems, making them suitable for a wide range of applications where robustness and precision are essential. In this section, both control laws \(\:{u}_{eq}\) and \(\:{u}_{sw}\) are designed with fuzzy rules. The fuzzy system I (FS-I) is used to design the equivalent control law \(\:{u}_{eq}\) to avoid the mathematical calculations and computational burdens. The FS-II is used to design the \(\:{u}_{sw}\) to minimize the chattering effect on the control action. Both fuzzy systems comprise four essential components that work together to process information and make decisions. The first component, fuzzification, is responsible for transforming crisp values—specific numerical inputs—into fuzzy values, which represent degrees of membership in various categories or sets. Following this, the second component, fuzzy reasoning, applies a set of fuzzy logic rules to the fuzzified inputs, enabling the system to draw inferences and conclusions based on the imprecise information. The third component, the knowledge-based system, contains the fuzzy rules and membership functions that define the system’s understanding and interpretation of the problem domain, serving as the foundation for the reasoning process. Finally, the fourth component, defuzzification, converts the resulting fuzzy output back into a crisp value or control signal, making it usable for practical applications. Together, these components enable fuzzy systems to handle uncertainty and make decisions in complex environments26. The detailed control structure of F-SMC is shown in Fig. 6. Here, \(\:{k}_{1}\), \(\:{k}_{2}\), \(\:{k}_{3}\) gain parameters of FS-I\(\:,\:{k}_{4}\) is the gain of the FS-II. The components of fuzzy systems are fuzzification, fuzzy reasoning, knowledge base, and defuzzification, which are described as follows. The input variables for FS-I are\(\:S\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\)\(\:dS/dt\) and the output variable is\(\:{u}_{eq},\) Similarly, the input variable for FS-II is \(\:S\) and the output variable is\(\:{u}_{sw}\) as shown in Fig. 6. The final control signal \(\:u\) obtained by summing \(\:{u}_{eq}\) and \(\:{u}_{sw}\).

The universe of discourse, inputs, and output membership functions (MFs) for FS-I and FS-II is shown in Fig. 7. The membership functions (MFs) used in both FS-I and FS-II map the input and output variables into fuzzy sets, where each fuzzy set represents a linguistic variable.

The linguistic variables for MF of the FS-I are described as Negative Large (NL), Negative Medium (NM), Negative Small (NS), Zero (ZE), Positive Small (PS), and Positive Medium (PM), Positive Large (PL).

A triangular type MF is used for the fuzzy sets of NM, NS, ZE, PS, and PM, and mathematically represented as:

where \(\:{\mu\:}_{.}\)\(\epsilon \left\{ {NM,NS,ZE,PS,PM} \right\}\). For the fuzzy sets of NL and PL, trapezoidal type MF are used and given as:

Here, the fuzzified crisp element is \(\:z\), and \(\:{a}_{i}\),\(\:\:{b}_{i}\) and \(\:{c}_{i}\) are the breakpoints of the ith trapezoidal or triangular MF. The rules for FS-1 and FS-II are constructed with the help of literature26, and all 49 rules for FS-I are depicted in Table 1. The complete fuzzy rules of FS-I are designed to obtain the control characteristic (\(\:{u}_{eq})\) of SMC based on the heuristic knowledge.

The second row and the last column depict a rule such as, “if\(\:S\)is NM and\(\:dS/dt\)is PL then\(\:{u}_{eq}\)is PM.”. The three rules of FS-II are as follows:

-

If\(\:S\)is N then\(\:{u}_{sw}\)is N.

-

If\(\:S\)is Z then\(\:{u}_{sw}\)is Z.

-

If\(\:S\)is P then\(\:{u}_{sw}\)is P.

Once the fuzzy reasoning process generates fuzzy outputs, the defuzzification step is needed to convert these fuzzy values back into a crisp control signal. In this study, the Center of Gravity (CoG) method is used for defuzzification. The CoG method calculates the weighted average of the output fuzzy sets to produce a single crisp value that serves as the final control signal. The discrete form of the CoG formula is given by: \(\:u=\frac{{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{n}{\mu\:}_{i}{u}_{i}}{{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{n}{\mu\:}_{i}}\),

where \(\:{\mu\:}_{i}\) is obtained by implementing the product rule to the subsequent fuzzy rule and the center value of fuzzy output set for \(\:{i}^{th}\) rule is \(\:{u}_{i}.\)

A comparison is made between the control laws \(\:{u}_{eq}\) and \(\:{u}_{sw}\) designed with C-SMC and F-SMC. In controller design theory, several performance indices are commonly used to evaluate system performance. These are Integral of Squared Error (ISE), Integral of Time-weighted Squared Error (ITSE), Integral of Absolute Error (IAE), Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error (ITAE). These performance indices help in designing and tuning controllers to achieve a balance between accuracy, speed, and stability. ISE reduces large errors more effectively than small ones. It has a slower response time because the error is squared and accumulated over time, placing greater emphasis on large errors. The ITSE minimizes long-term errors and enhances the settling time. However, it tends to have a large overshoot in the initial stages. IAE minimizes both small and large errors by integrating the absolute values of the errors over time, leading to smoother overall system performance. However, because it treats all errors equally, it may not prioritize reducing large magnitude errors as effectively, potentially resulting in slower correction of significant deviations. Despite this, IAE is valuable for eliminating steady-state errors and improving long-term accuracy. ITAE, like ITSE, may tolerate large initial errors but gradually reduces them as the system evolves. ITAE improves the smoothness of the system’s response, enhances settling time, and reduces long-term oscillations, resulting in a more stable and efficient control process. IAE and ISE are useful for tracking errors but do not influence the system’s speed. ITAE and ITSE are beneficial for achieving a fast system response and reducing long-term errors. In the comparison, ∆f, and cost functions such as ISE, ITSE, IAE, and ITAE are considered as comparative features of both the techniques, as shown in Fig. 8 and presented in Table 2.

GTO implementation

To compute the optimal parameters of PID-type sliding surface \(\:({k}_{p}\), \(\:{k}_{i}\), \(\:{k}_{d})\), FS-I \(\:({k}_{1}\), \(\:{k}_{2}\), \(\:{k}_{3})\), and FS-II \(\:({k}_{4})\), GTO is proposed. GTO is a newly invented metaheuristic approach whose fundamental is associated with the behavior of gorilla troops in nature. The proneness of gorillas to be in mass forbids them from living alone. Hence, they search for food as a mass and live under the supervision of a silverback gorilla, who leads the group. In GTO, the best solution corresponds to the silverback. The candidature of the gorilla is liable to proceed towards silverback and leave the worst solution (weakest member of the group).

The flowchart of GTO is revealed in Fig. 9. The Exploration and Exploitation phases are responsible for GTO operation, which are described as follows:

Exploration phase

Under this, each gorilla is regarded as the best solution in each iteration. Moreover, three mechanisms are present in this phase that can be mathematically formulated14,38:

where, \(\:GX\left(t+1\right)\) is the ith gorilla position vector, \(\:{r}_{1},{r}_{2},{r}_{3}\) and \(\:rand\) are the random numbers in the range [0,1], gorilla position vector in is \(\:X\left(t\right)\), \(\:{X}_{r}\) is one gorilla selected randomly in the entire population, LB and UB are the lower and upper bounds of variables and values of C and L are formulated as14:

The maximum iterations for optimization performance are \(\:MaxIt\), \(\:l\) is a random value in the range − 1, 1, and \(\:{r}_{4}\) is the random number [0,1]

Exploitation phase

The two mechanisms, “follow silverback gorilla” and “competition for the adult female,” are associated with this phase. Under first mechanism, each gorilla follows the silverback’s instructions to search the food in various locations and can be represented as14,38:

where the optimal solution is \(\:{X}_{silverback}\), at iteration \(\:t\) the gorilla’s vector position is \(\:G{X}_{i}\left(t\right)\). Moreover, when baby gorillas reach puberty, they search for adult females and compete with other gorillas and are represented as14:

where \(\:Q\) is considered to simulate the impact force.

Conventional optimization techniques like GA, PSO, GWO, and CTO often struggle with premature convergence. In PSO, an improper setting of inertia weight can exacerbate this issue. However, GTO mitigates premature convergence through population diversity and the continuous introduction of new solutions into the search process. Unlike conventional methods, which are sensitive to parameter variations, GTO is less sensitive due to its real-time feedback system. This adaptive nature of GTO allows for faster convergence compared to traditional techniques. PSO’s key parameters, such as inertia weight and acceleration coefficients, are fixed during the optimization process. This results in an imbalance between exploration and exploitation, often causing PSO to converge to local optima, especially in complex environments. In contrast, GWO manages exploration through a hierarchical structure, where the alpha wolf leads the search. However, the effectiveness of this leadership can be limited, particularly in diverse search spaces, potentially constraining exploration. On the other hand, GTO offers a dynamic balance between exploration and exploitation. This adaptability is achieved through troop migration and the refinement of troop positions around promising areas based on their interactions with the environment. This dynamic behavior enhances both search diversity and solution refinement. The enhanced exploration capability and ability to avoid local optima in optimization are inspired by the natural behavior of gorilla troops. Their migration to unfamiliar areas allows for broader exploration while following the dominant silverback guides them toward promising opportunities. The competition for resources within the group improves their ability to exploit these opportunities and refine solutions. This dynamic between exploration and exploitation helps optimize problem-solving processes, leading to more efficient and effective outcomes.

Flowchart of GTO14.

Results and discussion

The specifications and elements of ATMG are presented in Table 3. The simulation work was conducted in MATLAB. The asses the superiority of the designed controller, various practical cases, such as the impact of the wind speed, load uncertainties, and ATMG parametric uncertainties, are considered in this work. The general ATMG shown in Fig. 1 is used to assess the proposed LFC technique.

Various practical cases

This section studies the impact of wind speed variations, load perturbations, and higher/lower dimensions of MG. All the parameters in the simulation graphs are per unit (p.u.) values except the wind speed \(\:{V}_{w}\) in m/s. The \(\:{V}_{w}\) is assumed to be 12.5 m/s. The demand of the ATMG is 1.0 p.u. under normal case. The ATMG is simulated for 35 s with a time duration of 5 s in the MATLAB software. The GTO tunes the gains of the PID sliding surface F-SMC. To demonstrate the supremacy of the GTO-tuned PID sliding surface F-SMC technique, its outcomes are evaluated with PSO-tuned PID sliding surface F-SMC and GWO-tuned PID sliding surface F-SMC technique. The optimized parameters of the F-SMC with PSO, GWO, and GTO are revealed in Table 4. The gains of the PID sliding surface controller play an important role in achieving the desired performance, such as stable operation, speed of response, and robustness. The proportional gain is responsible for reducing the error, while the integral gain improves the dynamic response by eliminating steady-state error. The derivative gain is used to predict future errors and reduce overshoot and noise in the system.

-

Case-1 In this case, the operating conditions of the ATMG are the total load demand is 1.0 p.u. the share of the WTG is 0.75 p.u. and DEG is 0.25 p.u. without including the source side disturbances, i.e., the impact of wind speed variation on the controller performance. The comparison data of the transient characteristics such as peak overshoot (Os), peak undershoot (Us), and settling time (Ts) of frequency deviation of the ATMG and ISE, ITSE, IAE, and ITAE are also reported in Table 5. The given statistics show that the ISE/ ITSE/IAE/ITAE in the case of GTO-tuned F-SMC are found to be less as compared to other controllers such as PSO-tuned F-SMC and GWO-tuned F-SMC.

The convergence characteristics PSO, GWO and GTO is depicted in Fig. 10(a) and dynamic response of the GTO-tuned F-SMC in contrast to other controllers is shown in Fig. 10(b). The Us [Hz] of PSO, GWO, and GTO are − 0.2003, -0.1896, and 0.20, respectively. Figure 10(a) shows the proposed GTO surpasses the PSO and GWO in terms of minimization of objective function and speed of convergence.

-

Case-2 A variable demanded load is injected into the ATMG as depicted in Fig. 11(a). The renewable energy sources disturbance is not considered in the operation of ATMG. Figure 11(a) reveals that a base load of 0.8 p.u. is present before the demand disturbance. An emergency demand increment of 0.1 p.u occurs at 15s and is present up to 25s. Again, an emergency demand increment of 0.1 p.u appears at 25s and presents up to 35 s. The comparative performance of the F-SMC technique in terms of Δf with PSO, GWO, and GTO is presented in Fig. 11(b). In this scenario, the WTG contribution is 0.75 p.u. in contrast, the contribution of DEG is depicted in Fig. 11(c).

-

Case-3 Here, a rated wind speed, i.e., 12.5 m/s and WTG-rated power, 0.75 p.u. is applied to ATMG without any wind speed fluctuations. Here, load-side perturbation is studied as presented in Fig. 12(a). Both sudden load increment and decrement are studied in this case. The comparable plot of Δf under the proposed LFC technique with PSO/GWO/GTO is displayed in Fig. 12(b). Figure 12(b) reveals that the minimum Δf occurred in the GTO-based F-SMC rather than the GWO and PSO-designed LFC techniques. The contribution of DEG is shown in Fig. 12(c). Table 5 reveals the transient parameters and performance indices of all LFC control techniques.

-

Case-4 In this case, a sinusoidal varying load perturbation is injected into the ATMG system, as depicted in Fig. 13(a). The combination of three sinusoidal signals generates the sinusoidal varying load. The sinusoidal signals used in this case study are time-based sinusoidal signals. The amplitude and angular frequency of the first signal are 0.004 and 4 rad/sec, respectively. The amplitude and angular frequency of the second signal are 0.05 and 5.3 rad/sec, respectively. The amplitude and angular frequency of the third signal are 0.01 and 6 rad/sec, respectively. The comparative response of Δf of designed LFC techniques, including PSO, GWO, and GTO, are represented in Fig. 13(b). As observed in Fig. 13(b), the Us (in Hz) are − 0.221, -0.115, and − 0.023 of PSO, GWO, and GTO, respectively. Similarly, Os (Hz) is 0.053, 0.028, and 0.0018 of PSO, GWO, and GTO, respectively. The contribution of the WTG system is 0.75 pu, and the rest of the excess load is contributed by the DEG system, as depicted in Fig. 13(c).

-

Case-5 In this scenario, an above-rated and random wind speed pattern is studied to see the impact of on the design of the LFC technique of the ATMG system, as shown in Fig. 14(a). The sudden changes in wind speed occurred at three different instants, i.e., a sudden increase of 1 m/s of wind speed at near about 7s and 14s, then a sudden decrement of 2 m/s wind speed at 21s occurred as shown in Fig. 14(a). The corresponding controller action in terms of Δf is demonstrated in Fig. 14(c). Here, the proposed controller performed more effectively than the PSO fuzzy SMC and GWO fuzzy SMC. According to this wind speed, the β (beta) is adjusted by the pitch angle controller. This controller aims to maintain a beta minimum to get maximum output from the WTG system. The β variation is presented in Fig. 14(b).

The GTO-optimized F-SMC gives better LFC action on Us, Os, and Ts compared to PSO and GWO optimization techniques. The impact of random wind speed on Δf is depicted in Fig. 14(c). The detailed numerical values of Us, Os, and Ts are listed in case 5 of Table 5.

-

Case-6 Inserting white noise in the MATLAB circuit generates a highly fluctuated wind speed. The profile of this is shown in Fig. 15(a). The impact of the on the Δf and pitch angle are presented in Fig. 15(b) and Fig. 15(c), respectively. The detailed numerical values of Us, Os, and Ts are listed in case 6 of Table 5.

Robustness against parametric uncertainties

In this study, controller design focused on maintaining acceptable performance of the controller when the load uncertainties and wind fluctuations are perturbed. However, assessing whether the designed controller can also handle perturbations in the ATMG parameters is essential. However, assessing whether the designed controller can also handle perturbations in the ATMG parameters is essential. The robustness analysis of the GTO-tuned F-SMC technique is studied against changes in a different variable of the ATMG from its general value under Case 1. The ATMG parameters such as M, D, \(\:{R}_{d}\), and DEG’s time constants \(\:{T}_{g}\), \(\:{T}_{t}\) are considered for this study. For robustness analysis, one of the considered parameters is exposed to amend at once while the remaining parameters are at their general (nominal) values and observing their objective function, i.e., ITAE. The results recorded in Table 6 reveal that the GTO-tuned F-SMC technique is sturdy against wide parametric uncertainties. In Fig. 16(a), (b), and (c), the MG frequency fluctuations have been shown for a \(\:50\%\) increase and \(\:50\%\) decrease in the ATMG parameters M, D, and Rd, respectively. In Fig. 16(d), and 16(e), the MG frequency deviations have been shown for a \(\:50\%\) increase and \(\:50\%\) decrease in the DEG parameters \(\:{T}_{g}\), and \(\:{T}_{t}\) respectively. The performance of the controller in terms of change in performance index (ITAE) has also been reported in Table 6 using the notation of percentage (%) change in ITAE with respect to nominal ITAE. Here, the % change in ITAE is lesser for ± 50% (higher) change in system parameters, which shows the robustness of the proposed controller against system parametric uncertainties.

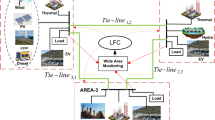

Controller validation on standard IEEE 14 bus system

The designed LFC scheme, i.e., GTO-tuned F-SMC, has also been validated upon a standard IEEE 14-bus system, as shown in Fig. 17(a)35. This test system consists of five synchronous generators, three transformers (100 MVA) each, and diverse static loads. The 1–5 buses are connected at 69 KV, and 6–14 buses are connected at 13.8 KV except 8-bus which is connected at 18 KV. Almost all buses are associated with load except 1-bus, 7-bus, and 8-bus. One aggregated WTG system is modeled and connected at 14-bus. All governors of the synchronous generators or reheated thermal units are modeled as a single governor reheated thermal unit, such as IEEEG1 in the IEEE-14 bus system35,36. The generalized model of the IEEEG1 system is depicted in Fig. 17(b). This model is employed for frequency control. Similarly, the IEEEX1 system is employed for the voltage control in the power system. The parameters of the tandem-compound or single-reheat steam turbine IEEEG1 are reported in Table 7. Figure 18 represents the validation results of GTO-tuned F-SMC in terms of Δf with various case studies. Figure 18 reveals that the Δf of all six cases (as discussed in subsection 4.1) is within the acceptable limits while validating on the IEEE-14 bus system.

Conclusion

An ATMG in the presence of DEG and the WTG system is investigated successfully. The dynamic model of the wind-participated ATMG system in the LFC method is suggested to avoid power fluctuations. In this work, GTO is utilized to obtain the proposed approach’s optimal parameters, i.e., F-SMC with PID-type sliding surface. The ATMG system has been exposed to wind speed variations, higher/lower dimensions of the ATMG, and load perturbations. To show the practicality of the suggested GTO-tuned F-SMC technique, the transient behavior of the investigated ATMG is contrasted with the outcomes given by GWO-tuned F-SMC and PSO-tuned F-SMC techniques. The suggested technique also reveals better performances with wind speed fluctuations. On the other hand, the studied GTO-tuned F-SMC also offers excellent robustness under system parametric perturbations. Real power system validation of the suggested control technique via the IEEE 14 bus system has been successfully performed. Furthermore, comparisons with the existing techniques, such as GWO-PIDF, GWO-PI(1 + DF), GTO-ISMC, and STF-PID, have been made to determine the superiority of the proposed technique. Future research directions may include investigating the design of multi-stage control structures with state-of-the-art optimization techniques, effectively coordinating diverse energy resources in multi-area MGs, and implementing incentives-based demand response schemes in solar-based ATMG systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hirsch, A., Parag, Y. & Guerrero, J. Microgrids: A review of technologies, key drivers, and outstanding issues. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 90, 402–411 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Phase step control in PLL of DFIG-based wind turbines for ultra-fast frequency support. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2024.3448454

Pathak, P. K. & Yadav, A. K. Fuzzy assisted optimal tilt control approach for LFC of renewable dominated micro-grid: A step towards grid decarbonization. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 60, 103551 (2023).

Ye, Y., Qiao, Y. & Lu, Z. Revolution of frequency regulation in the converter-dominated power system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 111, 145–156 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Parametric study of the effects of clump weights on the performance of a novel wind-wave hybrid system. Renew. Energy 219, 119464 (2023).

Li, H., Qiao, Y., Lu, Z., Zhang, B. & Teng, F. Frequency-constrained stochastic planning towards a high renewable target considering frequency response support from wind power. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 36(5), 4632–4644 (2021).

Wu, B., Lang, Y., Zargari, N. & Kouro, S. Power Conversion and Control of Wind Energy Systems (Wiely-IEEE Press, 2011).

Vidyanandan, K. V. & Senroy, N. Primary frequency regulation by deloaded wind turbines using variable droop. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 28(2), 837–846 (2012).

Liu, Y., Fan, R. & Terzija, V. Power system restoration: A literature review from 2006 to 2016. J. Modern Power Syst. Clean Energy 4(3), 332–341 (2016).

Ramesh, M., Yadav, A. K. & Pathak, P. K. An extensive review on load frequency control of solar-wind based hybrid renewable energy systems. Energy Sources, Part A Recov. Util. Environ. Effects 1–25 (2021).

Lee, D. J. & Wang, L. Small-signal stability analysis of an autonomous hybrid renewable energy power generation/energy storage system part I: Time-domain simulations. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 23(1), 311–320 (2008).

Das, D. C., Roy, A. K. & Sinha, N. GA based frequency controller for solar thermal–diesel–wind hybrid energy generation/energy storage system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 43(1), 262–279 (2012).

Bevrani, H., Habibi, F., Babahajyani, P., Watanabe, M. & Mitani, Y. Intelligent frequency control in an AC microgrid: Online PSO-based fuzzy tuning approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 3(4), 1935–1944 (2012).

Duan, Y., Zhao, Y. & Jiangping, Hu. An initialization-free distributed algorithm for dynamic economic dispatch problems in microgrid: Modeling, optimization and analysis. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 34, 101004 (2023).

Ramesh, M., Yadav, A. K. & Pathak, P. K. Artificial gorilla troops optimizer for frequency regulation of wind contributed microgrid system. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 18, 011005–011011 (2023).

Abdollahzadeh, B., Soleimanian, F. & Mirjalili, S. Artificial gorilla troops optimizer: A new nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 36(10), 5887–5958 (2021).

Pathak, P. K., Yadav, A. K., Shastri, A. & Alvi, P. A. BWOA assisted PIDF-(1+ I) controller for intelligent load frequency management of standalone micro-grid. ISA Trans. 132, 387–401 (2023).

Arya, Y. Effect of energy storage systems on automatic generation control of interconnected traditional and restructured energy systems. Int. J. Energy Res. 43(12), 6475–6493 (2019).

Li, Q., et al. Geospatial analysis of scour development in offshore wind farms. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 1–20 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1080/1064119X.2024.2369945

Yammani, C. & Maheswarapu, S. Load frequency control of multi-microgrid system considering renewable energy sources using grey wolf optimization. Smart Sci 7(3), 198–217 (2019).

Dhundhara, S. & Verma, Y. P. Application of micro pump hydro energy storage for reliable operation of microgrid system. IET Renew. Power Gener. 14(8), 1368–1378 (2020).

Sariki, M. & Shankar, R. Optimal CC-2DOF (PI)-PDF controller for LFC of restructured multi-area power system with IES-based modified HVDC tie-line and electric vehicles. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 32, 101058 (2021).

Mohanty, S. R., Kishor, N. & Ray, P. K. Robust H-infinite loop shaping controller based on hybrid PSO and harmonic search for frequency regulation in hybrid distributed generation system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 60, 302–316 (2014).

Khalghani, M. R., Khooban, M. H., Mahboubi-Moghaddam, E., Vafamand, N. & Goodarzi, M. A self-tuning load frequency control strategy for microgrids: Human brain emotional learning. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 75, 311–319 (2016).

Latif, A., Das, D. C., Ranjan, S. & Barik, A. K. Comparative performance evaluation of WCA-optimised non-integer controller employed with WPG–DSPG–PHEV based isolated two-area interconnected microgrid system. IET Renew. Power Gener. 13(5), 725–736 (2019).

Lu, Y. et al. Adaptive disturbance observer-based improved super-twisting sliding mode control for electromagnetic direct-drive pump. Smart Mater. Struct. 32(1), 017001 (2022).

Khamies, M., Magdy, G., Hussein, M. E., Banakhr, F. & Kamel,. An efficient control strategy for enhancing frequency stability of multi-area power system considering high wind energy penetration. IEEE Access 8, 140062–140078 (2020).

Chen, P., Yu, L. & Zhang, D. Event-triggered sliding mode control of power systems with communication delay and sensor faults. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 68(2), 797–807 (2020).

Song, X. et al. Predefined-time sliding mode attitude control for liquid-filled spacecraft with large amplitude sloshing. Eur. J. Control 77, 100970 (2024).

Ramesh, M., Yadav, A. K. & Pathak, P. K. Intelligent adaptive LFC via power flow management of integrated standalone micro-grid system. ISA Trans. 112, 234–250 (2021).

Abazari, A., Monsef, H. & Wu, B. Coordination strategies of distributed energy resources including FESS, DEG, FC and WTG in load frequency control (LFC) scheme of hybrid isolated micro-grid. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 109, 535–547 (2019).

Wang, C., Mi, Y., Fu, Y. & Wang, P. Frequency control of an isolated micro-grid using double sliding mode controllers and disturbance observer. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 9(2), 923–930 (2018).

Qian, D. & Fan, G. Neural-network-based terminal sliding mode control for frequency stabilization of renewable power systems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sinica 5(3), 706–717 (2018).

Govinda Chowdary, Vankayalapati, et al. "Hybrid fuzzy logic-based MPPT for wind energy conversion system." Soft Computing for Problem Solving: SocProS 2018, Volume 2. Springer Singapore, 2020.

Li, Y. & Xu, Q. Adaptive sliding mode control with perturbation estimation and PID sliding surface for motion tracking of a piezo-driven micromanipulator. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 18(4), 798–810 (2010).

Ma, Y. et al. Optimized design of demagnetization control for dfig-based wind turbines to enhance transient stability during weak grid faults. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2024.3457528

Yadav, A. K., Pathak, P. K., Sah, S. V. & Gaur, P. Sliding mode based fuzzy model reference adaptive control technique for an unstable system. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. B 100(2), 169–177 (2019).

Gholamrezaie, V., Dozein, M. G., Monsef, H. & Wu, B. An optimal frequency control method through a dynamic load frequency control (LFC) model incorporating wind farm. IEEE Syst. J. 12(1), 392–401 (2018).

Singh, S. et al. Modeling and control design for an autonomous underwater vehicle based on Atlantic Salmon fish. IEEE Access 10, 97586–97599 (2022).

Byerly, R. T., Aanstad, O. & Berry, D. H. Dynamic models for steam and hydro turbines in power system studies. IEEE Trans. Power App. Syst. 92(6), 1904–15 (1973).

Yang, D., Jin, Z., Zheng, T. & Jin, E. An adaptive droop control strategy with smooth rotor speed recovery capability for type III wind turbine generators. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 135, 107532 (2022).

Pathak, N. & Zechun, H. Hybrid-peak-area-based performance index criteria for AGC of multi-area power systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 15(11), 5792–5802 (2019).

Sah, S. V., Prakash, V., Pathak, P. K. & Yadav, A. K. Virtual inertia and intelligent control assisted frequency regulation of time-delayed power system under DoS attacks. Chaos Solitons Fractals 188, 115578 (2024).

Singh, K. & Arya, Y. Jaya-ITDF control strategy-based frequency regulation of multi-microgrid utilizing energy stored in high-voltage direct current-link capacitors. Soft Comput. 27(9), 5951–5970 (2023).

Hu, G., Zhang, X., Zhou, Y. & Liu, Y. A novel load frequency control strategy based on the wild horse optimizer. Energies, 16(3), 1–15 (2023).

Guo, X. et al. Inertial PLL of grid-connected converter for fast frequency support. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 9(4), 1594–1599 (2022).

Gupta, K., Kumar, D. & Ghosh, S. S. Load frequency control of interconnected power systems using Lévy flight-enhanced particle swarm optimization. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 60, 104337 (2023).

Zhao, D., Shao, D. & Cui, L. CTNet: A data-driven time-frequency technique for wind turbines fault diagnosis under time-varying speeds. ISA Trans. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2024.08.029

Pathak, P. K., Yadav, A. K. & Kamwa, I. Resilient ratio control assisted virtual inertia for frequency regulation of hybrid power system under DoS attack and communication delay. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1–9 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2024.3482274.

Peng, T.-S. et al. General and less conservative criteria on stability and stabilization of T-S fuzzy systems with time-varying delay. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 31(5), 1531–1541 (2022).

Shirkhani, M. et al. A review on microgrid decentralized energy/voltage control structures and methods. Energy Rep. 10, 368–380 (2023).

Kong, Y., Wang, T. & Chu, F. Meshing frequency modulation assisted empirical wavelet transform for fault diagnosis of wind turbine planetary ring gear. Renew. Energy 132, 1373–1388 (2019).

Ma, K., Yang, J. & Liu, P. Relaying-assisted communications for demand response in smart grid: Cost modeling, game strategies, and algorithms. IEEE J. Select. Areas Commun. 38(1), 48–60 (2019).

Tan, J. et al. Event-triggered sliding mode control for spacecraft reorientation with multiple attitude constraints. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 59(5), 6031–6043 (2023).

Miaofen, L. et al. Adaptive synchronous demodulation transform with application to analyzing multicomponent signals for machinery fault diagnostics. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 191, 110208 (2023).

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study, conception, and design. all authors commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This paper does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramesh, M., Yadav, A.K., Pathak, P.K. et al. A novel fuzzy assisted sliding mode control approach for frequency regulation of wind-supported autonomous microgrid. Sci Rep 14, 31526 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83202-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83202-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Optimal robust PI-type load frequency control of renewable penetrated power system with delayed electric vehicles aggregators

International Journal of Information Technology (2026)

-

State and disturbance estimation with supertwisting sliding mode control for frequency regulation in hydrogen based microgrids

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Adaptive vector oriented control of doubly fed induction generator wind turbines using M5P model tree for robust dynamic performance

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Fuzzy-2 deployment in indirect vector control and hybrid space vector modulation for a two-level inverter fed induction motor drive

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Optimization of automatic generation controllers in renewable multi-area power systems using the Fata Morgana algorithm

Scientific Reports (2025)