Abstract

Epigenetic therapy has gained interest in treating cardiovascular diseases, but preclinical studies often encounter challenges with cell-type-specific effects or batch-to-batch variation, which have limited identification of novel drug candidates targeting angiogenesis. To address these limitations and improve the reproducibility of epigenetic drug screening, we redesigned a 3D in vitro fibrin bead assay to utilize immortalized human aortic endothelial cells (TeloHAECs) and screened a focused compound library with 105 agents. Compared to the established model using primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells, TeloHAECs needed a higher-density fibrin gel for optimal sprouting, successfully forming sprouts under both normoxic and hypoxic cell culture conditions. We identified two epigenetic enzyme inhibitors as novel regulators of sprouting angiogenesis: A196, a selective SUV4-20H1/H2 inhibitor, demonstrated pro-angiogenic effects through increased H4K20me1 levels and upregulation of cell cycle associated genes, including MCM2 and CDK4. In contrast TMP-269, a selective class IIa HDAC inhibitor, exhibited anti-angiogenic effects by downregulating angiogenesis-related proteins and upregulating pro-inflammatory signaling. These findings highlight the suitability of the modified TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay for drug screening purposes and reveal both pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic drug candidates with therapeutic potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epigenetic mechanisms, i.e. modulation of gene expression via reversible chromatin modifications, have recently been associated with various cardiovascular diseases1. For example, several studies have revealed differential DNA methylation patterns in heart failure patients when compared to healthy patients2. Other studies have also associated atherosclerosis with epigenetic changes which regulate several proteins and transcription factors such as APOE and KLF43,4.

The dynamic and reversible nature of epigenetic processes makes them potential drug targets to regulate cardiomyocyte function, fibrosis and angiogenesis. Previously, studies have identified the positive effects of several histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors on reducing cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and triggering cardioprotective effects5,6. Also, a recent study suggested that histone lysine demethylase (KDM) inhibitors could be promising therapeutic agents for suppressing cardiac fibrosis7. Several epigenetic compounds regulating angiogenesis have also been previously studied8. This is highlighted by JQ1, a bromodomain inhibitor, recently shown to reduce tumor angiogenesis through modulating hypoxia response genes including vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) in triple negative breast cancer9. Furthermore, an EZH2 inhibitor GSK-343 in combination with a pan-HDAC inhibitor Panobinostat were shown to induce pro-angiogenic properties in vitro and to restore blood flow upon ischemic induction through decreasing H3K27me3 and increasing H3-acetylation10.

In angiogenesis assays, epigenetic compounds have been primarily studied in animal models and conventional 2D cell culture models, each with their unique set of challenges and drawbacks. In animal models, readouts are limited. There is also variability arising from different strains and species differences 11. On the other hand, 2D in vitro drug screening methods for cardiovascular research, such as viability assays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) using monolayers, lack the cellular complexity to mimic in vivo conditions. In these methods, cells differ significantly from their tissue environment in terms of their morphology, exposure to the surrounding factors and cell environment, differentiation, growth rate, gene expression patterns, and sensitivity to chemical compounds12. Emerging 3D human cell culture models and organoids address these challenges by generating data within a human cell context and establishing a three-dimensional cellular environment that facilitates interactions among various cell types within the 3D matrix and with their neighboring cells. 3D models are also easy to apply for high throughput screening, and compared to 2D models they mimic the tissue microenvironment better and thus provide an improved model to perform drug screening13.

The fibrin bead assay is an in vitro 3D co-culture model using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and fibroblasts , a system that has proven beneficial for angiogenesis studies14,15. It allows detection of longer time points, interactions between different cell types and growth in a 3D microenvironment. However, so far this model has not been used for screening epigenetic compounds, as there are limitations of using primary endothelial cells in screening assays, such as differences in quality and culturing conditions between laboratories, donor-to-donor variability and, short lifespan of the cells before losing their primary characteristics. 3D assays using immortalized endothelial cell lines, such as human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT)-immortalized human aortic endothelial cells, in short TeloHAECs, could offer an alternative for epigenetic screening of angiogenesis without these limitations.

In this study, we first optimized the fibrin bead assay with TeloHAECs to allow endothelial sprout formation in a 3D environment. To validate our assay, we analyzed the sprout growth under both normoxic and hypoxic cell culture conditions. An epigenetic screening of a compound library with 105 agents was performed in the TeloHAEC bead assay identifying two novel regulators of endothelial sprout formation. Our data demonstrates that modified TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay is suitable for drug screening applications.

Results

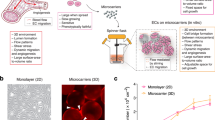

Extracellular matrix density regulates endothelial proliferation and sprouting in TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay

We previously used HUVECs in a fibrin bead assay and developed a new analysis tool, SproutAngio16, to detect and quantify the morphology and amount of endothelial cell (EC) sprouts. Here, we first tested the same gel composition (2.5 mg/ml fibrinogen) and VEGF-A treatment (10 ng/ml) with TeloHAECs following the same protocol used previously with HUVECs. In contrast to HUVEC sprouting, TeloHAECs showed a highly proliferative phenotype after 5 days in culture with (Fig. 1A) and without (Fig. 1B) VEGF-A stimulus. We hypothesized that altering the extracellular matrix composition could potentially modulate the observed phenotype of TeloHAECs. Increased concentrations of fibrinogen, 5 or 7 mg/ml, reduced the excessive EC proliferation (Fig. 1C); however, at higher concentration (7 mg/ml), inhibition of EC sprouting was observed despite VEGF-A stimulation (Fig. 1D). Quantitation of sprout length (Fig. 1E) and nuclei number (Fig. 1F) confirmed that 5 mg/ml fibrinogen concentration produced the optimal conditions for TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay.

TeloHAEC bead assay optimization. Representative confocal microscopy images of TeloHAECs with different densities of fibrin gel at day 5. TeloHAECs showing highly proliferative phenotype using 2.5 mg/ml fibrinogen A) with 10 ng/ml VEGF-A stimulation and B) without VEGF-A stimulus. C) 5 mg/ml and 7 mg/ml fibrinogen concentrations reduced the excessive EC proliferation and allowed sprout formation. D) 7 mg/ml fibrinogen concentration inhibited EC sprouting despite VEGF-A stimulus. In all images F-actin is stained using phalloidin-A635 (red), and nuclei with DAPI (cyan). Scale bars, 200 µm. Quantitative analysis of E) sprout length and F) nuclei number. n = 3–5 beads/group were analyzed using SproutAngio tool 16.

TeloHAECs form sprouts in normoxic and hypoxic conditions in a fibrin bead assay and secrete angiogenic factors

To further test the EC sprouting using TeloHAECs in the fibrin bead assay, we used both normoxic and hypoxic conditions to test the sprout formation (Fig. 2A, B). Quantitative image analysis by using the SproutAngio tool showed that both normoxic and hypoxic conditions stimulated EC sprouting (Fig. 2C-F). Hypoxia, however, stimulated thicker EC sprouts (Fig. 2E) containing more cells (Fig. 2F) compared to normoxia.

Endothelial sprouts are formed in TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay in both normoxia and hypoxia. Representative confocal microscopy images of TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay samples at day 5 under A) normoxic and B) hypoxic conditions showing EC sprouting. In all images, F-actin is stained using phalloidin-A635 (red), and nuclei with DAPI (cyan). Scale bar, 200 µm. C-F) Quantitative image analysis showed increased EC sprouting in hypoxic condition. Images were analyzed using SproutAngio tool. n = 12–15 beads/group, 2 independent experiments. G) Human angiogenesis protein array result showed the difference between normoxic and hypoxic conditions in TeloHAEC bead assay (n = 2, 2 independent experiments). VCBM: Vascular cell basal medium.

To quantify the secreted proteins in medium in TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay and to understand the difference in sprout morphology, a human angiogenesis protein array was used. As expected the hypoxic condition increased secretion of multiple angiogenic proteins compared to normoxia, including Serpin F1, TIMP-1 and VEGF-A (Fig. 2G). As VEGF-A is commonly used as an EC sprouting trigger in the HUVEC fibrin bead assay we also tested its effect on TeloHAEC fibrin assay and its secretome. The addition of VEGF-A affected the protein levels of EGF, IL-8 and MCP-1 under normoxia whereas Serpin F1, TIMP-1, IGFBP-3, Endothelin-1, and bFGF protein levels were not altered.

HIF stabilizer IOX-2 induces endothelial cell sprouting and secretion of angiogenic factors in TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay

As proof-of-concept for TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay usability for epigenetic compound screening, we tested the IOX-2 compound. IOX-2 is a potent HIF1α prolyl hydroxylase-2 inhibitor which elevates the HIF levels and can be used to induce a hypoxic response. After 5 days in culture, IOX-2 treatment was shown to induce EC sprouting with 5 µM and 10 µM concentrations (Fig. 3A). Quantitative analysis of confocal microscopy images by SproutAngio tool showed a significant increase of sprout nuclei number (Fig. 3B), length (Fig. 3C) and volume (Fig. 3D) in IOX-2 treated group compared to control, whereas for sprout number no significant difference was detected between control and IOX-2 treatment groups (Fig. 3E). Accordingly, the human angiogenesis protein array showed the differences in secreted proteins between the control and IOX-2 treatment groups (Fig. 3F). Compared to hypoxia results (Fig. 2G), IOX-2 (5 µM) treated groups showed a similar increase for the protein levels of IGFBP-1, VEGF-A and a decrease of uPA.

HIF stabilizer IOX-2 induces TeloHAEC sprouting. A) Representative confocal microscopy images of DMSO control, IOX-2 (5 µM) and IOX-2 (10 µM) treatment groups showing EC sprouting. In all images, F-actin is stained using phalloidin-A635 (red), and nuclei with DAPI (cyan). Scale bar, 200 µm. Quantitative image analysis of the confocal microscopy images showing significant differences between groups for B) nuclei number, C) sprout length and D) sprout volume whereas no significant difference observed for E) sprout number. Images were analyzed using SproutAngio tool. n = 18–20 beads/group. F) Human angiogenesis protein array result showing the difference between DMSO control and IOX-2 treatment groups (n = 2).

Epigenetic screening of a focused compound library reveals A-196 as pro-angiogenic and TMP-269 as anti-angiogenic factors

The validated TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay was used to screen the angiogenic effects of epigenetic compounds in a library of 105 epigenetic compounds. The compound library included molecules designed to interact with a diverse set of chromatin writers, erasers, and readers that were previously used to affect reprogramming of cells by targeting major chromatin-related pathways (Supplementary Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table 2)17. The compounds were first visually pre-screened in TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay to evaluate their overall effect on EC nuclei amount and sprout morphology, and 51 selected compounds having a visible effect were used for further quantitative screening by confocal microscopy. After 5 days in culture, distinct differences in endothelial sprout morphology were observed between the compounds (Fig. 4A) and SproutAngio tool was used to quantify sprout length (Fig. 4B) and other sprout morphology features (Supplementary Fig. 1B-D). As controls, wells without treatment or DMSO solvent control were used. Compared to untreated control, DMSO treatment caused a slight decrease in sprouting. A-196 and GSK-343 compounds were the top compounds promoting angiogenesis in the TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay, and they were further tested in a HUVEC fibrin bead assay (Supplementary Fig. 2). Only A-196 compound at the same dose promoted evident endothelium sprouting in HUVECs. Further quantitative analysis showed an increase in EC sprout formation in comparison to the control group, after 7 days in culture (Fig. 5A, 5C). Accordingly, by human angiogenesis protein array an increase in 12 angiogenesis-related proteins including SERPIN E1, TIMP-1, ANGPT2 and EDN1 compared to the control were detected (72 h, Fig. 5B). Further increase of sprout number was detected in A-196 treatment group with additional VEGF-A (20 ng/ml instead of 10 ng/ml; Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating that A-196 treatment enhanced VEGF-A impact.

Screening of an epigenetic compound library in TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay. A) Representative confocal microscopy images showing the differences between the compound treated groups. F-actin is stained using phalloidin-A635 (red), and nuclei with DAPI (cyan). Scale bar, 200 µm. B) After 5 days of compound treatment in culture media, sprout lengths were measured from confocal microscopy images by using SproutAngio tool. n = 3–5 beads/group.

Pro-angiogenic effects of SUV4-20H1/H2 inhibitor compound A-196. A) Representative confocal microscopy images of DMSO control and A-196 (1 µM) treatment groups in HUVEC fibrin bead assay showing the difference of the EC sprouting between these groups. F-actin is stained using phalloidin-A635 (red), and nuclei with DAPI (cyan). Scale bar, 200 µm. C) Quantitation of sprout number, length and width showing the pro-angiogenic effect of A-196 treatment. Images were analyzed using SproutAngio tool. n = 3–5 beads/group. B) Human angiogenesis protein array result showing the increased levels of angiogenesis related proteins in the A-196 treatment group compared to the control. D-E) The enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes showing the effects of the A-196 compound treatment at 72 h timepoint for fibroblast HPF-c cells (D) and HUVECs (E) detected by bulk RNA-sequencing. F) qPCR results of chromatin immunoprecipitation, calculated as percentage of input DNA, for H4K20me1, H4K20me2 and H4K20me3 antibodies at the target genes are indicated. n = 3 /group.

To investigate the effect of A-196 at the transcriptional level, bulk RNA-sequencing was conducted using A-196 treated HUVECs and fibroblasts. Gene set enrichment analysis showed that A-196 treatment upregulated pathways associated with cell proliferation and nutrient availability in HUVECs (Fig. 5D), in line with pro-angiogenic phenotypic effects of A-196 on ECs. The genes driving the enrichment signal included for example the metabolic regulator DDIT4, amino acid transporter or metabolic enzymes such as SLC1A5, SLC7A11, PSAT1 and ASNS, and cell cycle and proliferation genes such as MCM2, CDK4 and MYC (Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, in fibroblasts, A-196 tended to downregulate the same pathways that it stimulated in ECs (Fig. 5E).

A-196 compound was previously shown to inhibit SUV4-20H1/H2 causing a global decrease of H4K20me2/me3 and an increase of H4K20me118. To confirm that the pro-angiogenesis-related changes observed here were triggered via the same H4K20me1/me2/me3 change, HUVECs treated with A-196 were subjected to chromatin immunoprecipitation using H4K20me1, H4K20me2 and H4K20me3 antibodies. Then, primers of selected angiogenesis-related targets were used for the qPCR analysis (Fig. 5F). Results showed that A-196 treatment caused an increase in H4K20me1 bound angiogenic targets including ANGPT2, EDN1 and SERPIN E1 being in line with the changes detected in the protein array. Thus, A-196 likely induces angiogenic sprouting by inducing transcriptional activity of pro-angiogenic genes via inhibition of SUV4-20H1/H2. To confirm this, we performed a gene silencing experiment for SUV4-20H1/H2 in HUVEC bead assay. Silencing of SUV4-20H1 led to similar increase in endothelial sprouting as was seen with A-196 treatment (Supplementary 5). However, targeting both SUV-420H1/H2 did not increase sprouting (Supplementary 5).

Among the anti-angiogenic compounds examined, TMP-269 was chosen for detailed study due to its effective inhibition of EC sprouting (Fig. 3A). To validate the anti-angiogenic effects observed on TeloHAECs, TMP-269 was tested in HUVECs (Fig. 6A). Similarly, as in TeloHAEC fibrin assay, a decrease in endothelial sprout number and width was detected after 7 days in culture with TMP-269 treatment in comparison to control (Fig. 6C). Nevertheless, the suppression of sprouting was less pronounced compared to TeloHAECs, suggesting a differential response to this compound between aortic and venous endothelial cells. Human angiogenesis protein array results showed a decrease for several angiogenesis related proteins such as IGFBP-1, Angiopoietin-2, Endothelin-1 and IL-8 with increasing concentrations of TMP-269 (Fig. 6B). In addition, gene set enrichment analysis of bulk RNA-sequencing data demonstrated that TMP-269 upregulated pro-inflammatory signaling programs and cholesterol homeostasis in ECs (Fig. 6E). Genes driving enrichment results included PTGS2, CCL2 and INHBA (Supplementary Table 1). In fibroblasts, TMP-269 downregulated mesenchymal gene expression including several collagens and IGFBPs (Fig. 6D; Supplementary Table 1). Finally, in order to validate the effect of the compounds to cell cytotoxicity, two more endothelial cell lines were used, namely mouse C166 yolk sac and MS1 pancreatic islet endothelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 4). Neither A-196 nor TMP-269 exhibited cytotoxicity in these assays at 72 h timepoint.

Anti-angiogenic effects of HDAC class IIa inhibitor compound TMP-269. A) Representative confocal microscopy images of DMSO control and TMP-269 (10 µM) treatment groups in HUVEC fibrin bead assay with 10 ng/ml VEGF-A supplement. F-actin is stained using phalloidin-A635 (red), and nuclei with DAPI (cyan). Scale bar, 200 µm. B) Human angiogenesis protein array result showing the difference in the levels of angiogenesis related proteins. C) Quantitation of EC sprouting parameters sprout number, length and width showing the anti-angiogenic effect of TMP-269 treatment. Images were analyzed using SproutAngio tool. n = 3–5 beads/group. D-E) 3’mRNA sequencing enrichment analysis results for fibroblasts (C) and HUVECs (D) treated with TMP-269 compound at 72 h timepoint.

In summary, our data demonstrates that a modified TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay can be used for drug screening purposes. We demonstrate successful functional screening of an epigenetic enzyme inhibitor library and identify two novel angiogenesis modulators, a pro-angiogenic compound A-196 and an anti-angiogenic compound TMP-269 as novel drug candidates.

Discussion

Potentially reversible epigenetic changes are common for biological processes in health and disease. They provide a new perspective on therapeutic approaches and are becoming increasingly relevant for pre-clinical studies of cardiovascular diseases19,20,21. 3D human cell culture models hold great potential to study epigenetic modulators. These models better represent the complexity of the extracellular environment compared to 2D cell models. However, each method needs to be uniquely optimized to test the efficacy and safety of the epigenetic modulators. Here we optimized the 3D fibrin bead assay utilizing immortalized human aortic ECs under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. For the first time, to our knowledge, we used the fibrin bead assay with a selected set of epigenetic enzyme inhibitors, as a large-scale drug screening method for sprouting angiogenesis.

Endothelial sprouting was detected in our TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay under normoxia, hypoxia and IOX-2 (HIF1α prolyl hydroxylase-2 inhibitor) treatment. Thicker sprouts were formed in hypoxia in comparison to normoxia allowing the formation of endothelial tubes with a lumen space. Similarly observed in two other recent publications22,23, we noted differential EC behavior of TeloHAECs compared to HUVECs cultured on beads in fibrin gel. At longer time points with TeloHAECs cultured in same conditions and matrix than HUVECs, quantitative image analysis was difficult. In many cases, instead of tip cell guided EC sprouts we observed EC proliferation around the beads. TeloHAEC sprouts were thinner and consisted of single line nuclei instead of multinucleated sprouts. However, after the gel optimization, higher fibrin gel density allowed EC sprout formation and quantitation by image analysis tool.

While using the epigenetic compound screening, distinct differences of angiogenic sprouting between the compounds were detected. Among those, the top two compounds A-196 and GSK-343 were HMT inhibitors, seemed to be strongly pro-angiogenic in TeloHAECs. However, when tested with HUVECs, only A-196 was consistently pro-angiogenic and not GSK-343. There could be several reasons for this. First, different concentrations of the compound could give a different response for these two cell lines and therefore the dosage could be further optimized. Second, the pro-angiogenic effect of GSK-343 was previously shown in human endothelial colony-forming cells10. The variations in the composition of the cell culture media between the cell lines, or the differences between venous and arterial ECs could affect the results. A recent publication showed that GSK-343 treatment in monocytes upregulated VEGF-A24, suggesting a potential mechanism for angiogenesis. The effect of GSK-343 on TeloHAECs and HUVECs warrants for further studies using different media and VEGF-A stimulation.

A-196 compound is a selective inhibitor of SUV4-20H1/H2 (KMT5B, KMT5C) methyltransferase enzymes that together with PR-Set7 regulate the cell cycle18. SUV4-20H1/H2 enzymes function to methylate histone H4 at lysine 20 (H4K20me1) into di- or trimethylated forms (H4K20me2, H4K20me3)25,26. In previous studies, A-196 compound was used for treating several cell lines including human osteosarcoma, human prostate adenocarcinoma, mouse embryonic fibroblast, mouse embryonic stem cell18, human embryonic kidney 293, lymphoblastoid, primary fibroblast27, neutrophil28 and pre-adipocyte29 cells. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study A-196 was used on ECs. Our results supported the previously discovered involvement of H4K20 methylation in cell cycle and DNA repair30. In line with the previous observations in other cell lines, downregulation of SUV4-20H1/H2 using A-196 treatment did not cause toxicity in ECs in our study. Instead, A-196 promoted EC proliferation and angiogenesis. In addition, synergistic effect was observed with VEGF-A, which could be due to activation of both ANGPT2 and VEGF-A signaling pathways known to result in increased angiogenesis31. Further validation by siRNA knockdown experiments suggested that SUV4-20H1 enzyme could be the primary regulator of the observed pro-angiogenic effects. However, additional studies are needed to investigate these two enzymes independently.

The majority of the tested HDAC inhibitors in this study showed anti-angiogenic effects. Among those, TMP-269 had a strong anti-angiogenic effect while no cytotoxicity was detected in any of the tested EC lines. TMP-269 compound is a selective inhibitor of class IIa histone deacetylases (HDACs)32. Previously, its inhibitory effect on angiogenesis was shown in a matrigel plug assay using triple negative breast cancer cells focusing on the role of HDAC9 inhibition33. In other studies, its regulating effects of endothelial permeability was shown via H2A acetylation in brain ECs34 and Arg kinase binding protein 2 dependent mechanisms in lung ECs35. Here we report the effects of TMP-269 on EC sprout formation. TMP-269 treatment had an anti-angiogenic effect with a decrease in the secretion of several angiogenesis related proteins and reduction of EC sprouting in a fibrin bead assay. Our RNA-sequencing results suggested that TMP-269 could be causing an inflammatory stress in ECs and affect cholesterol metabolism, which could also potentially affect endothelial sprouting36. Further investigation is needed to determine the precise mechanism of TMP-269 to inhibit endothelial sprout formation.

In conclusion, our data demonstrates that TeloHAECs can be used in a fibrin bead assay as a suitable tool for screening epigenetic compounds and hypoxia-related effects for cardiovascular disease research. In contrast to previous screening methods which focused on single cellular/functional characteristics such as VEGF-A stimulation, EC proliferation or tube formation, our novel data is produced utilizing a fibrin bead assay with its 3D growth environment for EC interactions and co-culture with fibroblasts, mimicking several characteristics of EC sprouting in vivo. As a result, we identified a strong pro-angiogenic compound (A-196) and an anti-angiogenic compound (TMP-269) as regulators of endothelial sprouting which are potential drug candidates for the treatment of angiogenesis related diseases.

Materials and methods

Cells

Immortalized human aortic endothelial cells (TeloHAECs; CRL-4052; ATCC) were maintained in Vascular cell basal medium (VCBM; PCS-100–030; ATCC) with Cell Growth kit-VEGF (PCS-100–041; ATCC). PCS-100–041 contained (VEGF-A: 5 ng/mL, EGF: 5 ng/mL, FGF basic: 5 ng/mL, IGF-1: 15 ng/mL, L-glutamine: 10 mM, Heparin sulfate: 0.75 Units/mL, Hydrocortisone: 1 µg/mL, Ascorbic acid: 50 µg/mL, Fetal bovine serum: 2%). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were isolated from umbilical cords obtained from Kuopio University Hospital, approved from the Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Savo Hospital District, Kuopio, Finland (Decision No 341/2015), as previously described37, and cultured on fibronectin-gelatin coated surfaces (10 µg/ml, 0.05%; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in Endothelial Cell Growth medium with endothelial cell growth supplement without VEGF-A (Promocell, Heidelberg, Germany, passage < 3). Human pulmonary fibroblasts (HPF-c, passage < 11, Promocell) were cultured in Fibroblast Growth Medium 2 with SupplementMix (Promocell). To maintain optimal growth conditions the cells were seeded to 20–30% confluency and passaged at 80% confluency.

TeloHAEC fibrin bead assay

For HUVECs, standard fibrin bead assay was performed as previously described in detail (14,38). An optimized version of the fibrin bead assay was performed for the epigenetic compound screening using TeloHAECs. Preparation of cytodex beads, aprotinin and thrombin was prepared as described38. Briefly, a 50 ml glass bottle was siliconized using SL2 Sigmacote siliconizing reagent. Then, Cytodex 3 collagen coated microcarrier beads were hydrated for 3 h in DPBS (50 ml/g) at room temperature and autoclaved at 120 °C for 16 min. Prepared beads were stored at + 4 °C for experimentation. Lyophilized aprotinin from bovine lungs (Sigma-Aldrich A1153) was reconstituted in sterile water and sterile filtered to store at -20 °C. Thrombin (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was reconstituted in sterile water and stored at -20 °C.

200–400 µl bead suspension was taken into a 15 ml tube and washed twice using media with full supplements (VCBM). Supernatant was aspirated before each wash after 5 min of waiting for beads to settle down on the bottom of the tube. Beads were counted and mixed with TeloHAECs in 2 ml round-bottom Eppendorf tubes, 2500 beads per one million cells in 1.5 ml final volume. The mixed suspension was incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. To promote proper attachment of the cells onto the beads during the incubation, the tubes were gently mixed by inverting them upside down 5–6 times, every 20 min. During this inverting step, slow horizontal shaking of the tubes prevents the attachment of beads together. After the incubation period, the suspension was mixed one last time and waited 5 min for the beads to settle down. Then, the supernatant was aspirated to get rid of the unattached cells leaving approximately 0.5 ml of media in the tubes. The bead–cell suspensions were transferred to T25 flasks and fresh 5 ml VCBM media without VEGF supplement was added followed by incubation overnight at 37 °C.

Next day, 2.5, 5 or 7 mg/ml fibrinogen was reconstituted in warm DPBS. The fibrinogen solution was sterile filtered using a filter syringe and aprotinin was added (aprotinin final concentration 0.15 U/ml). TeloHAEC coated beads in T25 flasks were transferred to 15 ml tubes. After 5 min the beads settled on the bottom of the tubes and aspiration/washing steps using 1–2 ml VCBM media without VEGF supplement were repeated 2–3 times to get rid of the excess cells. Then, beads were counted using 10 µl volumes on a coverslip because some of the beads get lost during the transfer steps. After counting, the media was aspirated as much as possible without disturbing the beads and the coated beads were resuspended in fibrinogen solution (approximately 300 beads / 1 ml fibrinogen solution).

7.8 µl of 50 U/ml thrombin was added on the center of each well of a 48-well-plate, giving 1.56 U/ml final concentration. Then 250 µl fibrinogen-bead-aprotinin mixture was pipetted into the wells. Each well was pipetted up/down 5–6 times gently to homogenize the mixture before it starts forming the gel. This step was important to prevent the beads creating clusters and to promote the formation of homogenized gel structure to support the growth of the cells in 3D. After waiting 5 min at room temperature and 15 min at 37 °C incubator for the gel formation, HPF-c were seeded on top of the gels, 10,000 cells/well in a 48-well-plate (in 250 µl media/well).

Cell culture media without VEGF supplement was changed every second day except in the protein array experiments on day 3. On day 5, fibroblasts were removed using 0.25% trypsin and after a washing step using DPBS, cells were fixed in 4% PFA-PBS for 10 min. After another DPBS washing step, cells were treated with methanol (stored in − 20 °C) for 5 min at room temperature. After the fixation, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton in PBS for 5 min and stored in DPBS at + 4 °C.

Hypoxia experiments were carried out by culturing the cells in a hypoxia chamber at 1% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37 °C (Baker Ruskinn Invivo2 Ruskinn Technology Ltd.).

Gene silencing

HUVECs were seeded at 150.000 cells/well on 6-well plates in complete medium and transfected with siRNAs targeting SUV4-20H1 (hs.Ri.SUV420H1.13.1;#510,391,178, hs.Ri.SUV420H1.13.2;#510,391,181, hs.Ri.SUV420H1.13.3;#510,391,184) and SUV4-20H2 (hs.Ri.SUV420H2.13.1;#510,391,192) the following day using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Two siRNAs targeting SUV4-20H1 and one siRNA targeting SUV4-20H2, as well as a non-targeting control siRNA (10 nM, IDTDNA, Supplementary 5 for design ID and references) were transfected independently or in combination of SUV4-20H1 and -H2-targeting siRNAs. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were either collected for the fibrin bead assay or RNA was extracted with RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was done using the RevertAid RT Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a starting amount of 1 µg of total RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two µl of cDNA was used for qPCR in a total 10 µl reaction volume (1xTaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix [Applied Biosystems], 1 × PrimeTime qPCR Probe assay [IDTDNA], H2O) Table 1 run on QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

Immunostaining

Cells were treated with 3% Triton in PBS for 15 min. Phalloidin-A635 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:40) staining was performed in 3% Triton-PBS solution for 90 min to label F-actin. After three 15 min washing steps with 1X DPBS, nuclei were stained with DAPI (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 5 µg/ml in 3% Triton-PBS solution for 10 min and washed with DPBS. The cells were stored in DPBS at + 4 °C prior to imaging.

Image acquisition and analysis

Fibrin bead assay plates were imaged with a Zeiss LSM800 confocal laser scanning microscope using 10 × /0.3 PlanApo objective. DAPI was detected using 353/465 nm excitation/emission wavelengths, phalloidin was detected using 631/648 nm wavelengths. The frame size:1024 × 1024 pixels, z-dimension step size: 5 µm, and averaging of 2 were used. Images were analyzed using SproutAngio tool as previously described16. Shortly, Kruskal–Wallis test or one-way ANOVA were used to determine the statistical significance for the analysis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Epigenetic compounds

The collection of 105 compounds is listed in Supplementary Table 2 including a diverse set of chromatin writers, erasers, and readers targeting major chromatin-related pathways. DMSO control was used at 0.1% concentration.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

To investigate H4K20 methylation profile of A-196 treated ECs, we used Pierce Agarose ChIP kit (Thermo Scientific, 26,156) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 250.000 cells/well in 6-well-plate with 4 biological replicates were treated with DMSO (0.1%) or A-196 (1 µM) compound for 48 h. Formaldehyde fixed protein-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated using ChIP grade monoclonal antibodies against H4K20me1 (Thermo Fisher, MA5-18,067), H4K20me2 (Diagenode, C15200220), H4K20me3 (Thermo Fisher, MA5-36,090), positive (anti-RNA polymerase II antibody) and negative (Normal Rabbit IgG) control were used.

Quantitative PCR analysis

Quantitative PCR analysis was performed using target gene-specific Taqman assays in Table 2. Amplification of 1% total input sample from ChIP was used to calculate the percent input.

RNA-sequencing

For 3’ mRNA sequencing analysis, 72-h time point after epigenetic compound treatment with DMSO, A-196, TMP-269 was used. Total RNA from two biological replicates per treatment coming from the same donor was extracted using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Prior to RNA library preparation, the quality of the input RNA was assessed by using Fragment Analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California) RNA kit (DNF-471; Agilent Technologies). RNA library preparation was carried out using the Lexogen Quantseq 3’mRNA-seq Library Prep Kit-FWD for Illumina (Lexogen, Vienna, Austria) with additional unique dual indexing add-on kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The pool of libraries was sequenced using single-end sequencing with 50 bp reads on an Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer. The raw sequencing data has been deposited at NCBI GEO under accession GSE247693.

Sequencing reads were processed using the nf-core RNA-Seq pipeline (version 1.4.2;39) with the hg19 reference genome and Ensembl release 87 transcript definitions. Lowly expressed genes were filtered out using the filterByExpr function of the edgeR package (version 3.24.3;40), requiring a minimum of 10 counts in some sample and minimum 15 counts total. The number of genes remaining after filtering was 13,462. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed with the fgsea package (version 1.25.1;41) using default settings and the Hallmark gene sets obtained from MSigDB (release 2023.2.Hs;42). For GSEA, genes were ranked using moderated log2 fold changes calculated by the lfcShrink function of the DESeq2 package (version 1.22.2;43) accounting for experimental batch in the model and with other settings at their default values. Enrichment results were corrected for multiple testing using FDR, and adjusted p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Angiogenesis human protein array

To quantify the effects of epigenetic modulators, Proteome Profiler Human Angiogenesis Array Kit (55 proteins, R&D Systems, ARY007) was used according to the manufactorer’s instructions. From fibrin bead assay samples, media was taken at 72 h timepoint. Additionally, to see the effects of the VEGF-A stimulation 20 ng/ml VEGF-A was mixed with the fibrin gel in the beginning for the normoxia experiment as a separate group. Human angiogenesis protein array (R&D systems) was used based on the manufacturer’s instructions to detect changes in the secretome. Python’s Napari tool was used to measure the intensities of the blots44.

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis of the quantified images from the fibrin bead assay samples, we used Kruskal–Wallis test if Shapiro–Wilk test rejected the null-hypothesis of normality with the alpha-level 0.05. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 were used to show the statistical significance of the figures. Our statistical analysis and graph drawing algorithms are available at SproutAngio repository 16.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data has been deposited at NCBI GEO under accession GSE247693.

References

Gorica, E. et al. Epi-drugs in heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 923014 (2022).

Liu, C. F. & Tang, W. W. Epigenetics in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. JACC: Basic Transl. Sci. 4(8), 976–993 (2019).

Zhang, W., Song, M., Qu, J. & Liu, G. H. Epigenetic modifications in cardiovascular aging and diseases. Circ. Res. 123(7), 773–786 (2018).

Yang, C. et al. Role of Kruppel-like factor 4 in atherosclerosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 512, 135–141 (2021).

Duan, L. et al. Epigenetic mechanisms in coronary artery disease: The current state and prospects. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 28(5), 311–319 (2018).

Pickell, Z., Williams, A. M., Alam, H. B. & Hsu, C. H. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: a novel strategy for neuroprotection and cardioprotection following ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9(11), e016349 (2020).

Zhang, Q. J. et al. Histone lysine dimethyl-demethylase KDM3A controls pathological cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 5230 (2018).

Aspriţoiu, V. M., Stoica, I., Bleotu, C. & Diaconu, C. C. Epigenetic regulation of angiogenesis in development and tumors progression: Potential implications for cancer treatment. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 689962 (2021).

da Motta, L. L. et al. The BET inhibitor JQ1 selectively impairs tumour response to hypoxia and downregulates CA9 and angiogenesis in triple negative breast cancer. Oncogene 36(1), 122–132 (2017).

Fraineau, S. et al. Epigenetic activation of pro-angiogenic signaling pathways in human endothelial progenitors increases vasculogenesis. Stem Cell Rep. 9(5), 1573–1587 (2017).

Zuppinger, C. 3D cardiac cell culture: a critical review of current technologies and applications. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 6, 87 (2019).

Jensen, C. & Teng, Y. Is it time to start transitioning from 2D to 3D cell culture?. Front. Mol. Biosci. 7, 33 (2020).

Fontoura, J. C. et al. Comparison of 2D and 3D cell culture models for cell growth, gene expression and drug resistance. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 107, 110264 (2020).

Pulkkinen, H. H. et al. BMP6/TAZ-Hippo signaling modulates angiogenesis and endothelial cell response to VEGF. Angiogenesis 24(1), 129–144 (2021).

Mushimiyimana, I. et al. Characterization of a functional endothelial super-enhancer that regulates ADAMTS18 and angiogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 49(14), 8078–8096 (2021).

Beter, M. et al. Sproutangio: an open-source Bioimage Informatics tool for quantitative analysis of sprouting angiogenesis and lumen space. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 7279 (2023).

Ebrahimi, A. et al. Bromodomain inhibition of the coactivators CBP/EP300 facilitate cellular reprogramming. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15(5), 519–528 (2019).

Bromberg, K. D. et al. The SUV4-20 inhibitor A-196 verifies a role for epigenetics in genomic integrity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13(3), 317–324 (2017).

Cavalli, G. & Heard, E. Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature 571(7766), 489–499 (2019).

Berdasco, M. & Esteller, M. Clinical epigenetics: seizing opportunities for translation. Nat. Rev. Genetics 20(2), 109–127 (2019).

Soler-Botija, C., Gálvez-Montón, C. & Bayés-Genís, A. Epigenetic biomarkers in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Genetics 10, 950 (2019).

Patel, N. R. et al. Endothelial cell polarity and extracellular matrix composition require functional ATP6AP2 during developmental and pathological angiogenesis. JCI Insight https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.154379 (2022).

Zhu, Q. M. et al. Endothelial ARHGEF26 is an angiogenic factor promoting VEGF signalling. Cardiovasc. Res. 118(13), 2833–2846 (2022).

Rondeaux, J. et al. Ezh2 emerges as an epigenetic checkpoint regulator during monocyte differentiation limiting cardiac dysfunction post-MI. Nat. Commun. 14(1), 4461 (2023).

Schotta, G. et al. A chromatin-wide transition to H4K20 monomethylation impairs genome integrity and programmed DNA rearrangements in the mouse. Genes Dev. 22(15), 2048–2061 (2008).

Beck, D. B., Oda, H., Shen, S. S. & Reinberg, D. PR-Set7 and H4K20me1: at the crossroads of genome integrity, cell cycle, chromosome condensation, and transcription. Genes Dev. 26(4), 325–337 (2012).

Vilema-Enríquez, G. et al. Inhibition of the SUV4-20 H1 histone methyltransferase increases frataxin expression in Friedreich’s ataxia patient cells. J. Biol. Chem. 295(52), 17973–17985 (2020).

Calì, B. et al. Atypical CXCL12 signaling enhances neutrophil migration by modulating nuclear deformability. Sci. Signal. 15(761), eabk2552 (2022).

Pedrotti, S. et al. The Suv420h histone methyltransferases regulate PPAR-γ and energy expenditure in response to environmental stimuli. Sci. Adv. 5(4), eaav1472 (2019).

Hsiao, K. Y. & Mizzen, C. A. Histone H4 deacetylation facilitates 53BP1 DNA damage signaling and double-strand break repair. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 5(3), 157–165 (2013).

Joussen, A. M. et al. Angiopoietin/Tie2 signalling and its role in retinal and choroidal vascular diseases: a review of preclinical data. Eye 35(5), 1305–1316 (2021).

Lobera, M. et al. Selective class IIa histone deacetylase inhibition via a nonchelating zinc-binding group. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9(5), 319–325 (2013).

Salgado, E., Bian, X., Feng, A., Shim, H. & Liang, Z. HDAC9 overexpression confers invasive and angiogenic potential to triple negative breast cancer cells via modulating microRNA-206. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 503(2), 1087–1091 (2018).

Su, L. et al. Neuroprotective mechanism of TMP269, a selective class IIA histone deacetylase inhibitor, after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Neural Regen. Res. 15(2), 277 (2020).

Kovacs-Kasa, A. et al. Inhibition of Class IIa HDACs improves endothelial barrier function in endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. J. Cell. Physiol. 236(4), 2893–2905 (2021).

Lyu, J., Yang, E. J. & Shim, J. S. Cholesterol trafficking: An emerging therapeutic target for angiogenesis and cancer. Cells 8(5), 389 (2019).

Jaffe, E. A., Nachman, R. L., Becker, C. G. & Minick, C. R. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J. Clin. Investig. 52(11), 2745–2756 (1973).

Nakatsu, M. N., Davis, J. & Hughes, C. C. Optimized fibrin gel bead assay for the study of angiogenesis. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments) 3, e186 (2007).

Ewels, P. A. et al. The nf-core framework for community-curated bioinformatics pipelines. Nat. Biotechnol. 38(3), 276–278 (2020).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26(1), 139–140 (2010).

-Korotkevich, G., Sukhov, V., Budin, N., Shpak, B., Artyomov, M. N., & Sergushichev, A. Fast gene set enrichment analysis. BioRxiv, 060012, (2016).

Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 1(6), 417–425 (2015).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15(12), 1–21 (2014).

-napari contributors. napari: A multi-dimensional image viewer for python. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3555620 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The personnel of the Kuopio University Hospital maternity ward are acknowledged for providing umbilical cords. UEF Cell and Tissue Imaging Unit (Biocenter Kuopio, Biocenter Finland) is acknowledged for the use of the confocal microscope. Genome Center of University of Eastern Finland is acknowledged for the use of the sequencing instruments.

Funding

This work was supported by Horizon 2020 Framework Programme (Marie Sklodowska Curie grant agreement 740264; SYH), Academy of Finland (287478, 319324, 321535, 328835, 353376, 361994; JPL, MUK, SYH), GeneCellNano Flagship Program 337120 (SYH, JPL, NLK), ERC starting (802825; MUK) and advanced grants (GA670951; SYH). The study was supported by the Leducq Epigenetics of Atherosclerosis Network (LEAN) program grant from the Leducq Foundation (UO, SYH). This work was partly supported by the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research (JPL, MUK) and the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (MUK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B., J.P.L. and S.Y.H. designed and wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. M.B., H.H.P. and L.K. performed fibrin bead assay experiments, immunostaining and imaging. M.B. and H.H.P. performed the angiogenesis protein array. M.B. and E.A. performed the RNAseq library preparation and T.Ö. and M.U.K. performed the RNA-seq analysis. M.B. and N.L.K. performed the ChIP and qPCR analysis. A.S. performed the gene silencing experiments. J.E.D. and U.O. provided the epigenetic compound library. All authors edited the manuscript. U.O., J.P.L., and S.Y.H. provided materials and reagents for the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beter, M., Pulkkinen, H.H., Örd, T. et al. Epigenetic drug screening identifies enzyme inhibitors A-196 and TMP-269 as novel regulators of sprouting angiogenesis. Sci Rep 15, 1628 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84603-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84603-w