Abstract

Ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) is a major cause of acute kidney injury (AKI) and ultimately leads to renal fibrosis, primarily via the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathway. Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein 1 (LRG1), a novel modulator of the TGF-β pathway, has been implicated in the modulation of renal fibrosis by affecting the TGF-β/Smad3 signaling axis. However, the role of LRG1 in the transition from AKI to chronic kidney disease (CKD) remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate the functional role of LRG1 during the remodeling phase post-IRI. Unilateral IRI was induced in C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice and systemic LRG1 knockout (KO) mice. In C57BL/6J WT mice, renal LRG1 mRNA expression was significantly elevated on the ischemia/reperfusion side compared to the sham side over a 28-day period. In contrast, LRG1 KO mice demonstrated significantly reduced renal fibrosis compared to WT mice on postoperative day 28. Additionally, renal mRNA expression of TGF-β and associated pro-fibrotic genes was diminished in LRG1 KO mice compared to WT mice. Consequently, LRG1 KO mice exhibited attenuated IRI-induced chronic fibrosis. These findings indicate that LRG1 is involved in the pathogenesis of the transition from AKI to CKD and may be a potential therapeutic target.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) poses a substantial clinical challenge, affecting up to 10% of hospitalized patients and significantly increasing mortality across a broad spectrum of conditions1,2,3. AKI is also recognized for its potential progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD), a transition known as AKI-to-CKD, which remains a persistent clinical issue4,5. Coca et al. reported that the risk of developing CKD and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) in patients with AKI was 8.8 times (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.1–25.5) and 3.1 times (95% CI 1.9–5.0) higher, respectively, compared to those without AKI6. Ischemic and nephrotoxic injuries are considered as the primary causes of clinical AKI cases7,8, in which nearly two-thirds of intrinsic AKI are caused by ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI) due to postoperative renal hypoperfusion, bleeding, cardiogenic shock, or sepsis9,10,11. Consequently, renal IRI is a major cause of intrinsic AKI, and animal models of renal IRI are extensively utilized to investigate the pathogenesis of AKI and the AKI-to-CKD transition12,13.

A critical pathological feature of IRI is the inflammatory-fibrotic transition in the proximal tubule. Severe IRI induces proximal tubular damage, leading to maladaptive repair and subsequent renal fibrosis14,15,16,17. Renal fibrosis, the final common pathway in the AKI-to-CKD transition, is predominantly mediated by the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-Smad pathway18,19,20. Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein 1 (LRG1), a modulator of TGF-β signaling, is a glycoprotein with a unique leucine-rich repeat structure, primarily synthesized by hepatocytes and neutrophils, and expressed in the lungs, kidneys, heart, skin, brain, and testes21. Elevated LRG1 levels have been detected in the plasma and urine of patients with various malignancies and inflammatory diseases22. In renal pathology, LRG1 reportedly promotes the progression of diabetic kidney disease by enhancing TGF-β-induced angiogenesis in murine models, and is associated with renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes23,24. Furthermore, significant roles of LRG1 have been documented in rodent models of renal fibrosis, including unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) and aristolochic acid nephropathy (AAN)25. However, foundational evidence regarding the role of LRG1 in IRI-induced AKI is limited, with only one study showing that LRG1 silencing mitigates AKI following IRI by regulating autophagy and apoptosis via the TGF-β1-Smad1/5 signaling pathway26. Moreover, the role of LRG1 in the IRI-induced AKI-to-CKD transition remains unexplored.

This study aimed to investigate the functional roles of LRG1 in the AKI-to-CKD transition using systemic LRG1 knockout (KO) mice subjected to renal IRI, focusing on the remodeling phase of IRI. We hypothesized that understanding the pathogenesis of the remodeling phase of renal IRI is clinically significant, as it could lead to the identification of preventive strategies for the AKI-to-CKD transition27.

Results

IRI-induced renal atrophy and fibrosis association with increased renal LRG1 mRNA expression in wild-type (WT) mice

Unilateral IRI (uIRI) was induced in the left kidneys of WT mice (WT-I/R), while the right kidneys underwent a sham operation (WT-sham) (Fig. 1a). Two days post-IRI, the kidney weight-to-body weight ratio was significantly higher on the I/R side compared to the sham side, indicating renal hypertrophy during the acute phase of AKI (Fig. 1b). This difference resolved on postoperative day 7, and by days 14 and 28, the kidney weight-to-body weight ratio on the I/R side was significantly lower compared to the sham side (Fig. 1b). Fibrosis areas, assessed by Masson’s trichrome (MTC) staining and Picrosirius Red staining (PRS; Fig. 1c–e), remained unchanged in both the sham and I/R sides until postoperative day 7. However, fibrosis areas on the I/R side increased from postoperative day 14 and became significant by postoperative day 28 (Fig. 1c–e). In contrast, LRG1 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in the kidneys was significantly elevated on the I/R side compared to the sham side from day 7 to day 28, peaking on day 7 (Fig. 1f). These findings suggest that LRG1 is involved in the pathogenesis of the transition from IRI-induced AKI to CKD.

IRI-induced renal atrophy, renal fibrosis, and LRG1 expression in wild-type mice. (a) Experimental workflow for the unilateral ischemia–reperfusion injury (uIRI) models. Left kidneys from WT C57BL/6J mice were subjected to 30 min of ischemia. Unoperated right kidneys were used as controls (Sham). (b) The kidney weight-to-body weight ratio after IRI was quantified (n = 4). (c) Representative images of kidneys stained with MTC, PSR, and LRG1 (original magnification, × 200; scale bar, 100 μm) (n = 4). (d,e) Computerized quantification of the MTC and PSR stained areas (n = 4). (f) Relative renal mRNA expression of LRG1 (n = 4). Values are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 when compared between indicated groups by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. WT wildtype, I/R ischemia–reperfusion, uIRI unilateral IRI, MTC masson’s trichrome, PSR picrosirius-red, ●, WT-I/R; ○, WT-sham.

Systemic LRG1 KO suppressed IRI-induced renal fibrosis

Compared to WT mice, systemic LRG1-KO mice showed no significant differences in body weight, food and water intake, blood pressure, renal function, heart weight-to-body weight ratio, and kidney weight-to-body weight ratio at baseline (Supplementary Fig. S1). As shown in Fig. 2a, uIRI was induced in the left kidneys of littermate control WT and KO mice (WT-I/R and KO-I/R, respectively), while the right kidneys underwent sham operations (WT-sham and KO-sham, respectively). The expression of renal LRG1 was not upregulated in KO mice following IRI (Supplementary Fig. S2). Additionally, the tubular injury score was exacerbated on the I/R side compared to the sham side on postoperative day 2, but there was no significant difference between WT and KO mice (Supplementary Fig. S3). The kidney weight-to-body weight ratio in WT mice decreased from day 7 to day 28 post-IRI, while this ratio was preserved in KO mice during the same period (Fig. 2b–d). KO mice exhibited significantly reduced renal fibrosis areas compared to WT mice on day 28 (Fig. 2e–h). Consistent with these findings, renal mRNA expression of collagen type I (Col1) was significantly lower in KO mice compared to WT mice on postoperative day 28 (Fig. 2i). In contrast, no difference was observed in renal mRNA expression of collagen type III (Col3) between WT and KO mice on postoperative day 28 (Fig. 2j). These results indicate that LRG1 deficiency attenuates renal atrophy and fibrosis during the remodeling phase following renal IRI.

Effect of LRG1 on renal atrophy and renal fibrosis. (a) Experimental workflow for the uIRI models in WT and KO mice. Left kidneys from WT C57BL/6J mice were subjected to 30 min of ischemia. Unoperated right kidneys were used as controls (Sham). (b–d) Relative weight of post-IRI kidneys (I/R) compared to unoperated kidneys (Sham) in WT and KO mice was quantified (n = 6). (e) Representative images of kidneys stained with MTC (original magnification, × 200; scale bar, 100 μm) (n = 6). (f) Representative images of kidneys stained with PSR (original magnification, × 200, bar; scale 100 μm) (n = 6). (g,h) Computerized quantification of the MTC and PSR stained areas (n = 6). (i,j) Relative renal mRNA expression of Col1 and Col3 (n = 6). Values are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 when compared between indicated groups by 1-way ANOVA (c,d) and 2-way ANOVA (b,g,h,i and j) with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. WT wildtype, KO LRG1 knockout, I/R ischemia–reperfusion, uIRI unilateral IRI, MTC Masson’s trichrome, PSR picrosirius-red, Col collagen; ●, WT; ○, KO.

LRG1 deficiency effect on the expression of inflammatory markers in the kidney with IRI

Damaged renal tubular epithelial cells trigger an inflammatory response and cell infiltration into the renal interstitium, which are important pathological features in the progression of renal fibrosis following renal IRI28,29. Renal mRNA expression of IL-6, TNF-α, F4/80, and CCL2 was significantly elevated in both WT and KO mice in the I/R side compared to the sham side (Fig. 3a–d). IL-6 expression increased by day 2 after IRI in KO mice and by day 7 after IRI in WT mice and persisted until day 28 after IRI (Fig. 3a). TNF-α and F4/80 levels were significantly higher from days 2 to 7 after IRI; however, the difference between the KO-sham and KO-I/R groups disappeared by day 28 after IRI (Fig. 3b,c). CCL2 expression remained elevated on the I/R side from day 2 to day 28 after IRI in WT and KO mice (Fig. 3d). No significant differences were observed between WT and KO mice for any of these markers throughout the study period (Fig. 3a–d).

Effect of LRG1 on IRI-induced kidney inflammation. (a–d) Relative renal mRNA expression of IL-6, TNFα, F4/80 and CCL2 (n = 6). Values are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 when compared between indicated groups by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. WT wildtype, KO knockout, I/R ischemia–reperfusion, IL-6 interleukin-6, TNFα tumor necrosis factor α, CCL2 chemotactic-C–C-motif-chemokine-ligand-2; ●, WT; ○, KO.

LRG1 deficiency effect on the infiltration of immune cell into the kidney and markers of tubular damage with IRI

Next, we evaluated macrophage infiltration into the kidneys after IRI. Given that a previous study reported that LRG1 is normally produced by hepatocytes and neutrophils30, we also evaluated neutrophil infiltration into the kidneys after IRI. The results of immunohistochemical staining for F4/80 and Ly6G on postoperative day 28 showed that IRI significantly increased the infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils into the kidneys in both WT and KO mice. However, there was no significant difference in macrophage and neutrophil infiltration into the kidneys between WT-I/R and KO-I/R (Fig. 4a–d). Similarly, the expression of tubular injury biomarkers, such as kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1), was significantly increased on day 28 after IRI, but LRG1 deficiency did not affect the expression of KIM-1 (Fig. 4e,f and Supplementary Fig. S4).

Effect of LRG1 on the IRI-induced infiltration of immune cell into the kidney. (a) Representative images of kidneys stained with F4/80 on postoperative day 28 (original magnification, × 400; scale bar, 100 μm). ▲ indicates F4/80 positive cells. (b) The number of F4/80-positive cells in kidney tissue from WT and LRG1 KO mice on postoperative day 28. Five fields were evaluated per mouse (n = 6). (c) Representative images of kidneys stained with Ly6G on postoperative day 28 (original magnification, × 400; scale bar, 100 μm). ▲ indicates Ly6G positive cells. (d) The number of Ly6G-positive cells in kidney tissue from WT and LRG1 KO mice on postoperative day 28. Five fields were evaluated per mouse (n = 6). (e) Representative images of kidneys stained with KIM-1 on postoperative day 28 (original magnification, × 200, bar; scale 100 μm). (f) Computerized quantification of the KIM-1-stained areas (n = 6). Values are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 when compared between indicated groups by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. WT wildtype, KO knockout, I/R ischemia–reperfusion, KIM-1 kidney injury molecule 1; ●, WT; ○, KO.

LRG1 deficiency suppressed renal TGF-β expression and fibrosis-promoting genes after IRI

TGF-β is an important regulator of renal fibrosis, and various extracellular matrix components (e.g., collagens and fibronectin [FN]), which activate the TGF-β signaling pathway, can be transcriptionally regulated by TGF-β itself, creating multiple positive feedback loops31. Therefore, we investigated the renal expression of TGF-β and related fibrosis-promoting factors. Renal mRNA expression of TGF-β was significantly lower in KO mice compared to WT mice on postoperative day 28 (Fig. 5a). The mRNA expression of FN and the protein level of α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), a TGF-β-related fibrosis-promoting factor, were also suppressed in KO mice compared to WT mice at 28 days (Fig. 5b–d). As a result, we speculate that LRG1 deficiency may have attenuated renal fibrosis by disrupting the positive feedback loop of TGF-β, thereby suppressing the expression of TGF-β and its related pro-fibrotic genes.

Effect of LRG1 on renal TGF-β and pro-fibrotic genes expression after IRI. (a,b) Relative renal mRNA expression of TGF-β and FN (n = 6). (c,d) Representative western blots and quantitative analysis of αSMA in the kidney on postoperative day 28 (n = 6). Values are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 when compared between indicated groups by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. WT wild-type, KO LRG1 knock out, I/R ischemia–reperfusion, TGF transforming growth factor, FN fibronectin, αSMA α-smooth muscle actin; ●, WT; ○, KO.

Discussion

Although it has been documented that LRG1 expression is upregulated in the early phase of IRI26, this study extends these findings by demonstrating that renal LRG1 expression remains persistently elevated throughout the remodeling phase of IRI. Specifically, our results revealed that systemic LRG1 deficiency significantly ameliorated IRI-induced renal atrophy and chronic fibrosis, concomitant with reduced renal expression of TGF-β and associated pro-fibrotic factors. These findings suggest that LRG1 may contribute to renal fibrosis by modulating the expression of TGF-β and its downstream pro-fibrotic genes during the progression from the AKI-to-CKD transition induced by IRI.

TGF-β is an important regulator of fibrosis in multiple organ systems, and its increased expression is correlated with renal fibrosis32. TGF-β exerts its biological and pathological effects by binding to its receptor and activating the TGFβ-Smad3 signaling pathway, thereby promoting fibroblast proliferation, migration, activation, and extracellular matrix deposition in the renal interstitium33,34. Although pharmacological inhibition of TGF-β has been reported to attenuate IRI-induced renal fibrosis35, previous studies have shown that mice deficient in TGF-β suffer from lethal inflammation and early mortality, indicating that complete suppression of TGF-β expression can be deleterious36. Therefore, to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the transition from AKI to CKD and to develop effective therapeutic strategies, it is important to target modulators of TGF-β that play significant roles in disease pathogenesis.

Given that LRG1 modulates TGF-β signaling, inhibiting LRG1 does not entirely suppress the TGF-β pathway, potentially preserving the basal TGF-β signaling necessary for physiological homeostasis. Thus, LRG1 inhibitors may represent a novel therapeutic approach for preventing the progression from AKI to CKD due to IRI, a clinical scenario currently lacking effective treatments. Fan et al. reported that the administration of a drug that degrades LRG1 diminished the secretion of fibrosis-associated proteins, consequently attenuating the progression of renal fibrosis37. Drugs that inhibit LRG1 expression may be an effective treatment for the transition from AKI to CKD caused by renal ischemia, which occurs in various clinical situations, including major vascular and cardiac surgery, postoperative hypoperfusion, shock, and renal transplantation.

Many proteins involved in TGF-β activation, such as integrins, proteases (MMP-2/9), and some extracellular matrix components (collagen and FN), are transcriptionally induced by TGF-β, suggesting the existence of a positive feedback loop for TGF-β signaling31. LRG1 KO may mitigate renal fibrosis by weakening this positive feedback mechanism, thereby suppressing the expression of TGF-β and its associated pro-fibrotic genes. Furthermore, LRG1 may influence multiple pathways implicated in renal fibrosis, as it has been reported to play roles in the Wnt1/β-catenin pathway, which is crucial for renal fibrosis, and the MAPK/p38 pathway, a key mediator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)38,39,40.

Interestingly, we observed no significant differences in the expression of renal inflammation-related genes between the WT-I/R and KO-I/R groups, or in markers of tubular damage. Studies have demonstrated that while the initial inflammatory response is essential for tissue repair, uncontrolled and persistent inflammation due to severe IRI leads to organ fibrosis41,42,43. Although inflammation is a critical factor in aberrant renal repair post-IRI, the absence of significant differences in inflammatory gene expression, whether with or without LRG1, suggests that LRG1 may have a minimal association with inflammation in its antifibrotic effects during the AKI-to-CKD transition. Conversely, inflammation has been reported to be a significant driver of LRG1 expression, with various cytokines activating LRG1 in multiple cell types and disease contexts44. The IRI-induced upregulation of renal LRG1 expression may be a reactive change in response to IRI-induced inflammation. However, it is worth noting that the causal relationship between renal LRG1 and inflammation remains unclear and warrants further investigation.

KIM-1 is a transmembrane glycoprotein present in the apical membrane of the proximal tubular epithelium and is highly expressed in injured epithelial cells, and KIM-1 levels are associated with the severity of tubular injury45. In this study, renal mRNA expression of KIM-1 was significantly elevated from day 2 to day 28 after IRI, but there were no significant differences between WT and KO mice. Furthermore, chronic KIM-1 expression in renal epithelial cells has been reported to directly cause interstitial inflammation, leading to progressive fibrotic kidney disease. The stable expression of KIM-1 in proximal tubular cells in vitro has also been reported to induce CCL2 release and macrophage chemotaxis46. In our results, macrophage infiltration into the renal interstitium and renal CCL-2 expression on postoperative day 28 were significantly elevated on the I/R side compared to the sham side, but there was no significant difference between WT and KO mice. Thus, LRG1 may not be associated with KIM-1-mediated pathways in its antifibrotic effects during the transition from AKI to CKD. However, the causal relationship between renal LRG1 and KIM-1 remains unclear and requires further investigation.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the analysis of the downstream signaling pathways of TGF-β was insufficient, necessitating further investigation. Secondly, the experiments were conducted over a limited period of 28 days, highlighting the need for longer-term studies. Thirdly, the renal function could not be measured because uIRI was performed13,47. Lastly, the specific functions of LRG1 in renal tubules, glomeruli, and endothelial cells, as well as the changes in these sites due to LRG1 deficiency, remain to be elucidated.

In conclusion, LRG1 deficiency ameliorates IRI-induced renal atrophy and chronic fibrosis, accompanied by reduced TGF-β expression. These findings suggest that LRG1 plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of the transition from AKI to CKD and represents a potential therapeutic target for preventing or mitigating this progression.

Methods

Animals

This study was conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of experimental animals and was reviewed and approved by the Animal Studies Committee of Yokohama City University. All experiments were performed following the ARRIVE guidelines. Male C57BL/6J WT mice were purchased from Oriental Yeast Co., Ltd. Systemic LRG1-KO mice on a C57BL/6 background were generated using a targeted gene disruption strategy. The mice were housed in a controlled environment with a 12-h light/dark cycle at 25 °C and provided with ad libitum access to food and water.

Experimental protocol

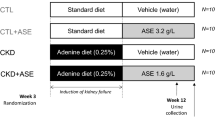

In the first experiment (Fig. 1a), uIRI was induced in 6- to 8-week-old male C57BL/6 WT mice. Renal ischemia was performed via a retroperitoneal approach to the left kidney using an atraumatic vascular clip for 30 min13,48. Mice were anesthetized with a combination of domitor, midazolam, and butorphanol, and anesthesia was reversed with antisedan. Body temperatures were monitored and maintained between 36.5 and 37.0 °C using a heat-controlled surgical pad. The mice received intraperitoneal injections of 500 μL normal saline at the end of surgery. The operated left kidney was designated as I/R, and the unoperated right kidney was designated as Sham. Mice were sacrificed at 2, 7, 14 and 28 days post-surgery (n = 4 per group). In the second experiment (Fig. 2a), uIRI was performed on littermate control WT and LRG1 KO mice using a similar method, and the mice were sacrificed at 2, 7, and 28 days postoperatively. The experimental subgroups included WT and LRG1 KO mice (n = 6 per group).

Histological and immunohistochemical analysis

Histological analyses were performed as previously described49,50. Briefly, mouse kidneys were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, incubated overnight at 4°C, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μm thick) were stained with PSR, MTC and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). Fibrotic areas were digitally measured using a fluorescence microscope (BZ-X800; Keyence, Osaka, Japan) in the cortical fields of MTC and PSR-stained specimens. Medullary tissue, blood vessels and glomeruli were excluded when images of PSR-stained specimens were acquired. Tubular injury score was based on the following scoring system with 10 random locations selected from PAS-stained sections from the cortex at × 200 magnification. The percentage of tubules at the corticomedullary junction showing tubular dilatation, tubular atrophy, tubular cast formation, vacuolation, degeneration, loss of tubular epithelial cells or loss of brush border, and tubular basement membrane thickening: (0) none; (1) ≤ 10%; (2) 11–25%; (3) 26–45%; (4) 46–75%; and (5) > 76%51. Kidney sections were evaluated by a nephrologist in an unblinded fashion. Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described52. Sections were incubated with anti-LRG1 antibodies (polyclonal rabbit, 1:50; 13224-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Proteintech, IL, USA), anti-F4/80 antibodies (monoclonal mouse, 1:25; sc-377009; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-KIM-1 antibodies (polyclonal goat, 1:100, AF1817, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and anti-Ly6G antibodies (monoclonal rabbit, 1:50; #87048; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Interstitial F4/80-positive cells and Ly6G-positive cells were counted in five randomly selected cortical fields (magnification: × 400). KIM-1 positive areas were digitally measured using a fluorescence microscope (BZ-X800; Keyence, Osaka, Japan). All measurements were conducted in a blinded manner.

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis

Total kidney RNA was extracted using an ISOGEN reagent (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), as previously described51. Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR analysis was conducted using the ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System, with reverse transcription products with PCR Master Mix and TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The TaqMan probes used for PCR were leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein 1 (LRG1), Mm01278767_m1; collagen type I (Col1a1), Mm00801666_g1; collagen type III (Col3a1), Mm01254476_m1; TNF-α, Mm00443258_m1; IL-6, Mm00446190_m1; F4/80, Mm00802529_m1; CCL2, Mm00441242_m1; TGF-β, Mm01178820_m1; and FN, Mm01256744_m1; KIM-1, Mm00506686_m1; NGAL, Mm01324470_m1. mRNA levels were normalized to 18S rRNA levels.

Immunoblot analysis

Kidney tissues, including both cortex and medulla, were homogenized in radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 4 °C. Protein expression was analyzed using western blotting of tissue homogenates, as previously described53. Briefly, equal amounts of protein extract were separated by 5–20% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using the iBlot Dry Blotting System (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). The membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: (1) anti-GAPDH antibody (1:2000, #2118, Cell Signaling Technoloogy, Danvers, MA, USA) and (2) anti-αSMA antibody (monoclonal rabbit, 1:1000, #19245, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) for 60 min at 25 °C. Images were captured with auto-exposure and automatically optimized using the ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Band density was quantified by densitometry using Image Lab software (version 6.1) and expressed relative to the density of GAPDH.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism software version 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± standard error. Comparisons among three groups (Fig. 2c,d) were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Two-way ANOVA was used for other multiple comparisons. Post hoc analyses were conducted using Bonferroni’s test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Levy, E. M., Viscoli, C. M. & Horwitz, R. I. The effect of acute renal failure on mortality. A cohort analysis. JAMA 275, 1489–1494 (1996).

Chertow, G. M., Burdick, E., Honour, M., Bonventre, J. V. & Bates, D. W. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 3365–3370 (2005).

Al-Jaghbeer, M., Dealmeida, D., Bilderback, A., Ambrosino, R. & Kellum, J. A. Clinical decision support for in-hospital AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 29, 654–660 (2018).

Chen, J. et al. VNN1 contributes to the acute kidney injury-chronic kidney disease transition by promoting cellular senescence via affecting RB1 expression. FASEB J. 36, e22472 (2022).

Charlton, J. R. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging accurately tracks kidney pathology and heterogeneity in the transition from acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 99, 173–185 (2021).

Coca, S. G., Singanamala, S. & Parikh, C. R. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 81, 442–448 (2012).

Hou, S. H., Bushinsky, D. A., Wish, J. B., Cohen, J. J. & Harrington, J. T. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency: A prospective study. Am. J. Med. 74, 243–248 (1983).

Basile, D. P., Anderson, M. D. & Sutton, T. A. Pathophysiology of acute kidney injury. Compr. Physiol. 2, 1303–1353 (2012).

Lameire, N. H. et al. Acute kidney injury: An increasing global concern. Lancet 382, 170–179 (2013).

Agarwal, A. et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 1288–1299 (2016).

Reid, S. & Scholey, J. W. Recent approaches to targeting canonical NFκB signaling in the early inflammatory response to renal IRI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32, 2117–2124 (2021).

Bonventre, J. V. & Yang, L. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Investig. 121, 4210–4221 (2011).

Fu, Y. et al. Rodent models of AKI and AKI-CKD transition: An update in 2024. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 326, F563–F583 (2024).

Pefanis, A., Ierino, F. L., Murphy, J. M. & Cowan, P. J. Regulated necrosis in kidney ischemia–reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 96, 291–301 (2019).

Dragun, D. et al. Prolonged cold preservation augments vascular injury independent of renal transplant immunogenicity and function. Kidney Int. 60, 1173–1181 (2001).

Quiroga, I. et al. Major effects of delayed graft function and cold ischaemia time on renal allograft survival. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 21, 1689–1696 (2006).

Danobeitia, J. S., Djamali, A. & Fernandez, L. A. The role of complement in the pathogenesis of renal ischemia–reperfusion injury and fibrosis. Fibrogenes. Tissue Repair 7, 16 (2014).

Boor, P., Ostendorf, T. & Floege, J. Renal fibrosis: Novel insights into mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 6, 643–656 (2010).

Loboda, A., Sobczak, M., Jozkowicz, A. & Dulak, J. TGF-β1/Smads and miR-21 in renal fibrosis and inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 8319283 (2016).

He, L. et al. AKI on CKD: Heightened injury, suppressed repair, and the underlying mechanisms. Kidney Int. 92, 1071–1083 (2017).

Camilli, C., Hoeh, A. E., De Rossi, G., Moss, S. E. & Greenwood, J. LRG1: An emerging player in disease pathogenesis. J. Biomed. Sci. 29, 6 (2022).

De Rossi, G., Da Vitoria Lobo, M. E., Greenwood, J. & Moss, S. E. LRG1 as a novel therapeutic target in eye disease. Eye (London) 36, 328–340 (2022).

Hong, Q. et al. LRG1 promotes diabetic kidney disease progression by enhancing TGF-beta-induced angiogenesis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 30, 546–562 (2019).

Liu, J. J. et al. Plasma leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein 1 predicts rapid eGFR decline and albuminuria progression in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 102, 3683–3691 (2017).

Hong, Q. et al. Modulation of transforming growth factor-β-induced kidney fibrosis by leucine-rich α-2 glycoprotein-1. Kidney Int. 101, 299–314 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Lrg1 silencing attenuates ischemia–reperfusion renal injury by regulating autophagy and apoptosis through the TGFβ1-Smad1/5 signaling pathway. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 753, 109892 (2024).

Nieuwenhuijs-Moeke, G. J. et al. Ischemia and reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation: Relevant mechanisms in injury and repair. J. Clin. Med. 9, 253 (2020).

Liu, B. C., Tang, T. T., Lv, L. L. & Lan, H. Y. Renal tubule injury: A driving force toward chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 93, 568–579 (2018).

Ide, S. et al. Ferroptotic stress promotes the accumulation of pro-inflammatory proximal tubular cells in maladaptive renal repair. eLife 10, e68603 (2021).

O’Donnell, L. C., Druhan, L. J. & Avalos, B. R. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of leucine-rich alpha2-glycoprotein, a novel marker of granulocytic differentiation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 72, 478–485 (2002).

Yan, X., Xiong, X. & Chen, Y. G. Feedback regulation of TGF-β signaling. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 50, 37–50 (2018).

Gu, Y. Y., Liu, X. S., Huang, X. R., Yu, X. Q. & Lan, H. Y. Diverse role of TGF-β in kidney disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 123 (2020).

Broekema, M. et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the renal interstitial myofibroblast population and produce procollagen I after ischemia/reperfusion in rats. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 165–175 (2007).

Meng, X. M., Nikolic-Paterson, D. J. & Lan, H. Y. TGF-β: The master regulator of fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 12, 325–338 (2016).

Li, D. et al. TGF-β1 peptide-based inhibitor P144 ameliorates renal fibrosis after ischemia-reperfusion injury by modulating alternatively activated macrophages. Cell Prolif. 55, e13299 (2022).

Kulkarni, A. B. et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 770–774 (1993).

Fan, L. et al. Targeted degradation of LRG1 to attenuate renal fibrosis. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 19, 100941 (2024).

Yang, P., Li, S., Zhang, H., Ding, X. & Tan, Q. LRG1 accelerates wound healing in diabetic rats by promoting angiogenesis via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Int. J. Low Extrem. Wounds https://doi.org/10.1177/15347346221081610 (2022).

Xie, Z. B., Zhang, Y. F., Jin, C., Mao, Y. S. & Fu, D. L. LRG-1 promotes pancreatic cancer growth and metastasis via modulation of the EGFR/p38 signaling. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38, 75 (2019).

Huang, R., Fu, P. & Ma, L. Kidney fibrosis: From mechanisms to therapeutic medicines. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 129 (2023).

Ferenbach, D. A. & Bonventre, J. V. Mechanisms of maladaptive repair after AKI leading to accelerated kidney ageing and CKD. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 11, 264–276 (2015).

Humphreys, B. D. Mechanisms of renal fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 80, 309–326 (2018).

Gewin, L. S. Renal fibrosis: Primacy of the proximal tubule. Matrix Biol. 68–69, 248–262 (2018).

Dritsoula, A., Camilli, C., Moss, S. E. & Greenwood, J. The disruptive role of LRG1 on the vasculature and perivascular microenvironment. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1386177 (2024).

Dase, J. et al. Analysis of mRNA and protein kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) expression in a kidney model during the initiation phase of ischemia reperfusion injury. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond.) 75, 103373 (2022).

Humphreys, B. D. et al. Chronic epithelial kidney injury molecule-1 expression causes murine kidney fibrosis. J. Clin .Investig. 123, 4023–4035 (2013).

Le, C. N. et al. Unilateral renal ischemia–reperfusion as a robust model for acute to chronic kidney injury in mice. PLoS ONE 23, e0152153 (2016).

Zager, R. A., Johnson, A. C. & Becker, K. Acute unilateral ischemic renal injury induces progressive renal inflammation, lipid accumulation, histone modification, and “end-stage” kidney disease. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 301, F1334–F1345 (2011).

Ohsawa, M. et al. Deletion of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor-associated protein enhances renal sodium reabsorption and exacerbates angiotensin II-mediated hypertension. Kidney Int. 86, 570–581 (2014).

Tsurumi, Y. et al. Interacting molecule of AT1 receptor, ATRAP, is colocalized with AT1 receptor in the mouse renal tubules. Kidney Int. 69, 488–494 (2006).

Tanaka, S. et al. Effects of a high-protein diet on kidney injury under conditions of non-CKD or CKD in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 7778 (2023).

Maeda, A. et al. Angiotensin receptor-binding protein ATRAP/Agtrap inhibits metabolic dysfunction with visceral obesity. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2, e000312 (2013).

Tsukamoto, S. et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor-associated protein in immune cells: A possible key factor in the pathogenesis of visceral obesity. Metabolism 149, 155706 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Yokohama Foundation for Advancement of Medical Science; the Uehara Memorial Foundation; the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; the Japan Kidney Association-Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Joint Research Program; the Japanese Association of Dialysis Physicians; the Salt Science Research Foundation; the Strategic Research Project of Yokohama City University; the Moriya Scholarship Foundation; the Bayer Scholarship for Cardiovascular Research; the Japan Science and Technology Agency (Grant Number JPMJPF2303); Takeda Science Foundation; the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research: and Yokohama City University research grant “KAMOME Project”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.O., H.W., and K.A. designed and conducted the research. N.O, H.W., and K.A. wrote the manuscript. N.O., T.M., E.K., S.T., M.S., S.T., S.U., K.I., S.K., and T.K. performed the experiments. N.O. analyzed the data. K.T. supervised the research. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okami, N., Wakui, H., Azushima, K. et al. Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein 1 deficiency suppresses ischemia–reperfusion injury-induced renal fibrosis. Sci Rep 15, 1259 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84798-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84798-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Leucine-rich α-2 glycoprotein 1 is associated with increased mortality risk in patients with peripheral artery disease

Journal of Molecular Medicine (2025)