Abstract

The virus known to cause COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, exhibits severe and complex neurological symptoms. These effects may be attributed to a virus-induced neuroinflammatory environment, warranting exploration of the respiratory centers of the brain, namely the pons and medulla, specifically in relation to neuroinflammation, demyelination, and neuronal death in response to COVID-19. Interestingly, older adults with neurological dysfunction maintained on N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antagonists, such as memantine, had reduced incidence and severity of COVID-19. Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate (1) the neuroinflammatory response to COVID-19 in the respiratory centers of the brain, and (2) to assess the extent to which NMDAR antagonists offer neuroprotective measures in the context of COVID-19. In a susceptible mouse model, animals inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 were pre-treated with either memantine or an alternative NMDAR antagonist, ifenprodil. Inoculated animals had poor survival and showed signs of neuroinflammation, evidenced by a reduction in morphological structure, demyelination, and changes in astrocyte and microglial expression in the pons and medulla. Mice pre-treated with memantine showed improved survival when challenged with COVID-19 and a reduction in virus-induced neuroinflammatory impairments. Our findings support the further investigation of memantine for the prevention of COVID-19 induced neuroinflammation and resultant neurological symptoms and shed light on the possible protective mechanism of memantine in the elderly maintained on NMDAR antagonists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised numerous questions regarding the neurological complications of the disease. The virus known to cause COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, exhibits neurological symptoms similar to other coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-1/SARS, MERS, or HCoV-OC431,2. These symptoms range from common issues such as headache, dizziness, brain fog, and loss of taste and smell3,4,5 to more complex conditions such as encephalitis, encephalopathy, and cerebrovascular diseases5,6,7. To exert these effects, SARS-CoV-2 invades the central nervous system (CNS) using various methods8,9,10. The virus is known to enter cells using receptors such as ACE2 or NRP111,12,13,14,15. ACE2 is expressed in the olfactory epithelium and on the nervus terminalis, which innervates the nasal cavity, providing a direct route for the virus to reach the brain16,17. These receptors are also highly expressed in the lungs and upper respiratory tract18,19, which are innervated by the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve originates in the brainstem, allowing SARS-CoV-2 access to the respiratory centers of the brain12,20,21. The brainstem, consisting mostly of the medulla oblongata and pons, coordinates communication between the brain and the rest of the body, controlling automatic functions including respiration22. Viral invasion and subsequent disruptions in these brain regions may result in an inability to regulate essential life functions and attentiveness22,23. For example, the neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19 such as dizziness, brain fog, and encephalitis are signs of damage to the brain stem23. Further, it is known that direct intracranial inoculation of SARS-CoV in rodents produces fulminant pneumonia symptoms and similar disease incidence as intranasal inoculation24,25, highlighting the vital role that the brain plays in disease progression of COVID-19.

Once SARS-CoV-2 infiltrates the brain, the virus triggers a hyperactive immune response and induces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the CNS, known as a cytokine storm26,27. This dysregulated and excessive immune response is thought to be directly correlated to poor COVID-19 outcomes27,28,29, further indicating the necessity to quell the inflammatory response induced by COVID-19. Increased cytokine production can serve as a proxy for the activation of microglia30,31, which among other homeostatic functions, are resident immune cells that engulf and eliminate foreign substances invading the CNS32,33. Astrocytes are also resident CNS cells important for blood brain barrier integrity and physiologic functions34,35. Microglia are known to induce astrocyte reactivity36,37, which precipitates demyelination of axons17 and additional cytokine release38. Glial cells exhibit morphological differences when activated, making them reliable markers for neuroinflammation32,35. SARS-CoV-2 is hypothesized to invade the respiratory centers of the brain, leading to neuronal damage characterized by visible demyelination, morphological alterations, increased neuronal death, and heightened neuroinflammatory markers such as the appearance of astrocytes and microglia.

Interestingly, there are reports of reduced COVID-19 incidence and severity in older individuals maintained on N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antagonists39,40,41,42. NMDAR antagonists are a class of medication known to have neuroprotective effects in excitotoxic environments (i.e., where the overactivation of NMDARs causes cell death) and may also prevent the full blown neuroinflammatory processes43,44,45. Examples of NMDAR antagonists include memantine, an FDA-approved antagonist that exhibits some off-target effects46, and ifenprodil, a selective antagonist which targets the receptor subunit thought to be most closely associated with excitotoxicity47,48,49. Previous work shows that NMDAR antagonists ameliorate symptoms in a murine coronavirus model45, and memantine has been shown in vitro to have efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 to directly limit viral replication50. A few clinical trials and case reports have shown that treatment with NMDAR antagonists improves COVID-19 symptomology and disease manifestation39,40,41,42,51,52, including a clinical trial from Algernon using ifenprodil, though not a pre-treatment53. This evidence suggests that excessive neuroinflammation in the CNS respiratory centers in the pons and medulla due to COVID-19 exposure may respond to NMDAR antagonism when subjects are pretreated with memantine or ifenprodil, resulting in a less severe pathology. Proof of concept studies in animal models are essential to support clinical trial evaluation of NMDAR antagonists in the treatment and prevention of COVID-19’s severe symptomology.

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate (1) the neuroinflammatory environment in the respiratory centers of the brain induced by COVID-19 exposure over time and (2) to assess the extent to which NMDAR antagonism may offer neuroprotective effects in the context of COVID-19. Murine subjects pre-treated with NMDAR antagonists to model potential protective effects and inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 were examined over the time course of disease progression (Fig. 1). Several markers of neuropathology in the respiratory centers of the brain, namely the pons and medulla oblongata, were evaluated, including demyelination and neurodegeneration, the presence of microglia and astrocytes, as well as general neuronal morphology.

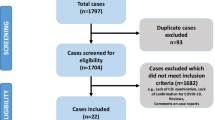

Experimental Design. In a mouse model susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 (K18-hACE2), animals were divided into 12 experimental groups. Animals either inoculated or not inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 were pre-treated twice daily (BID) with either saline, memantine (10 mg/kg), or ifenprodil (10 mg/kg), and sacrificed at either 3, 6, or 10 days post-inoculation.

Results

Pre-treatment with an NMDAR antagonist improves survival and health outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 inoculated animals

Older individuals with neurological disorders (ie, Alzheimer’s Disease) taking NMDAR antagonists (eg, memantine) have reduced incidence and severity of COVID-19 infection39,40,41,42. Generally, this population is regarded as “high risk”, making this observation quite quizzical. We proposed in the present study that this effect was due to the actions of their concurrent clinically prescribed NMDAR therapeutics. To model this scenario, we first treated subjects chronically with NMDAR antagonists twice a day (10 mg/kg) for 1 week to achieve steady state concentrations of the compounds. Following inoculation with SARS-CoV-2, animals were monitored throughout the experiment for observable effects on health and received 2xdaily injections of either saline or the NMDAR antagonist. Survival and body weight (as a measure of disease incidence) are reported for groups 1, 4, 8, and 12 (i.e., the (−) control and the 10-day post-inoculation groups treated with saline, memantine, and ifenprodil) (Fig. 2). No animals died in the COVID-19 negative group, but in the saline-treated, COVID-19 positive group, all animals were either found dead or euthanized for humane reasons, with tissue collected. Euthanization was required for animals meeting the humane endpoint criteria defined by the NIH54. Briefly, predetermined signs of severe distress, pain, or illness such as significant weight loss, labored breathing, lethargy, or inability to eat or drink indicate the need for euthanasia to prevent unnecessary suffering. The groups treated with NMDAR antagonists had fewer deaths, and the remaining animals were sacrificed at the 10 day timepoint for analyses. Analysis using a two-way ANOVA of the number of surviving animals per treatment group over time shows that both time and treatment increase survival outcomes (Fig. 2A, Main effect of drug treatment F[3, 28] = 5.288, p = 0.0053; main effect of time F[9, 27] = 4.161, p = 0.0019). Survival outcomes are significantly worsened in COVID-19 positive animals compared to negative animals ((−) Control vs. Saline, p = 0.0086, post-hoc analyses). Pre-treatment with memantine resulted in a significantly improved survival outcome (Saline vs. memantine, p = 0.0447, post-hoc analyses).

Pre-treatment with an NMDAR Antagonist Improves Survival and Health Outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 Inoculated Animals. (a) Survival outcomes of Groups 1, 4, 8, and 12 ((−) Control, Saline, Memantine, and Ifenprodil at 10 Days, respectively). **p < 0.01 (compared to (−) Control) and #p < 0.05 (compared to Saline). (b) Health outcomes of Groups 1, 4, 8, and 12. Body weight, as a measure of disease incidence, is graphed as % baseline weight over time. Non-linear regression analyses for (−) Control compared to (c) Saline, (d) Memantine, and (e) Ifenprodil treated groups are also shown as separate graphs. Dotted lines represent 95% CI.

As COVID-19 progresses, decreased body weight is indicative of worsened disease state. Body weight is reported as percent of baseline weight, measured prior to inoculation (Fig. 2B–E). Nonlinear regression analyses of each group are shown separately for saline (Fig. 2C), memantine (Fig. 2D), and ifenprodil (Fig. 2E) compared to the negative control. Animals negative for COVID-19 had little to no fluctuation in body weight (Fig. 2B–E, Best fit: Horizontal Line), while saline treated animals positive for COVID-19 had a significant reduction in body weight starting after day 5 post-inoculation (Fig. 2C, Best fit: Segmental Line; X0 = 5, Slope1 = 0, Slope2 = − 3.96). COVID-19 positive animals treated with memantine, similar to the negative control, had little to no fluctuation in body weight (Fig. 2D, Best fit: Horizontal Line). Interestingly, COVID-19 positive animals treated with ifenprodil showed a reduction in body weight starting around day 5, similar to the saline treated group, however, body weight returned to normal levels by day 10 post-inoculation (Fig. 2E, Best fit: Segmental Line; X0 = 6, Slope1 = − 0.8076, Slope2 = 0.8604). We posit that this return to baseline weight is due to the death of animals more heavily impacted by COVID-19, occurring at day 8, which is when the last death in this group was recorded. This is evidenced by the observation that the body weight of the surviving animals remains consistent, with no signs of disease progression (data not shown, best fit: horizontal line). The differences between the mice that survived and died could be attributed to several factors, including the effects of genetic variability on drug metabolism and immune response. Overall, these results show the health impacts of SARS-CoV2 and how pre-treatment with an NMDAR antagonist may reduce the severity of these untoward outcomes.

NMDAR antagonists mitigate morphological and myelination deficits induced by COVID-19 infection

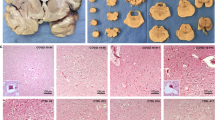

To visualize morphological changes to neuronal structure, samples of pons and medulla from each group underwent processing with cresyl violet, which stains blue/purple the Nissl substance in the neurons of the brain. Upon visual inspection, lighter staining, indicating loss of anatomical organization, is seen overall in the sections infected with the virus for 10 days versus sections not exposed (Fig. 3). To further examine the images semi-quantitatively, individuals blinded to the treatment groups were asked to rank every image in a counter-balanced order, giving each image a score from 1 to 3, with 1 indicating an increased amount of white zones in the stain and 3 indicating a more typical blue/purple staining as seen for control tissue (Fig. 3B). The mode ranks for each image were analyzed for each treatment group (Fig. 3D), with higher ranks suggesting a more complete morphological anatomy and lower ranks suggesting morphological alterations due to disease. To identify the spread of ranks across groups, we compared the total frequency of ranks 1, 2 or 3 from all images and blinded observers for each group using a Chi-square test. A statistically significant difference in ranking spread was observed between groups due to the treatment and time course of COVID-19 progression (χ2 = 269.3, df = 22, p < 0.0001). Representative images for each treatment group, as well as the percentage of each rank given per group, can be found in the Supplementary Information (Supp Figs. S1, S3A). To further understand the impacts of treatment and time on morphology, we calculated the mode ranking for each image and compared across all groups using the Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons. We observed a statistically significant difference between groups (H = 47.32, p < 0.0001), indicating that treatment and time post-inoculation impact morphology. In COVID-19 positive subjects pre-treated with saline vehicle, the rank given for morphology is significantly lower at 10 days post-inoculation compared to the negative control (Saline: 10 Days vs. (−) control, p = 0.0374, post-hoc analyses). In subjects not inoculated with the virus, no differences were observed with drug treatment. Interestingly, no differences were observed in morphology with memantine pre-treatment at 3 or 6 days post-inoculation compared to saline (3 Days: Saline vs. Memantine, p > 0.9999; 6 Days: Saline vs. Memantine, p > 0.9999, post-hoc analyses); however, the morphology rank of memantine treated subjects returned to negative control levels by day 10 post-inoculation (Memantine: 6 Days vs. 10 Days, p = 0.0373; 10 Days vs. (−) control, p > 0.9999; 10 Days: Saline vs. Memantine, p = 0.0580, post-hoc analyses). In COVID-19 positive subjects pre-treated with ifenprodil, no differences in morphological rank were observed at 3 days post-inoculation compared to negative control, however an increase in rankings was observed at 6 and 10 days post-inoculation to a level consistent with the negative control (Ifenprodil: 3 days vs. (−) control, p > 0.9999; 3 days vs. 6 days, p = 0.0106; 3 days vs. 10 days, p = 0.0001; 6 days vs. (−) control, p > 0.9999; 6 Days: Saline vs. Ifenprodil, p = 0.0169; Memantine vs. Ifenprodil, p = 0.0001; 10 Days: Saline vs. Ifenprodil, p = 0.0149, post-hoc analyses). Overall, these results suggest that infection with COVID-19 causes morphological deficits in the pons and medulla over time post-inoculation, while pre-treatment with ifenprodil and memantine ameliorate this deficit by day 6 or 10 days post-inoculation, respectively.

NMDAR Antagonists Mitigate Morphological Deficits Induced by COVID-19 Infection. (a) Visualization of morphological differences in medulla samples among key groups using cresyl violet staining. Key groups include those sacrificed 10 days after COVID-19 inoculation, with representative images of samples either positive or negative for COVID-19 and treated with saline (control), memantine, or ifenprodil. Representative images for all other groups can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1. Each image is shown in the 4 × and 10 × magnification with anatomical markers labeled. (b) Examples of images representative of each semi-qualitative rank for Cresyl Violet stain. (c) Representative Nissl (left) and anatomical annotations (right) from the Allen Brain Reference Atlases—Adult Mouse Brain [ref] showing i) pons and ii) medulla for reference119,120,121,122,123,124. (d) Cresyl violet (CV) semi-qualitative rankings according to time sacrificed post-virus inoculation and treatment group. Individual data points are representative of mode ranking values from sections in pons and medulla. Error bars represent mode qualitative ranking + /− S.E.M. Significant differences between groups are denoted with *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.005. N = 3–20 sections per group.

Similar to the cresyl violet stain, Black-Gold II staining was used to visualize any changes in the myelin of the pons and medulla due to exposure to COVID-19 and treatment with an NMDAR antagonist. This process directly stained the myelin a maroon color, allowing for clear visualization of differences. A light-blue counter Nissl stain can also be observed in these images (Fig. 4).To further examine the images semi-quantitatively, individuals blinded to the treatment groups ranked the images 1–3, with 1 representing lessened myelination (lighter maroon staining) and 3 representing typical or greater myelination (darker maroon staining) (Fig. 4B). The ranking spread and mode for each image were analyzed as before (Fig. 4D). Chi-square testing showed that drug treatment and time post-inoculation influenced the spread of myelination rankings (χ2 = 169.3, df = 22, p < 0.0001). Representative images for each treatment group, as well as the percentage of each rank given per group, can be found in the supplementary information (Supp Figs. S2, S3B). A statistically significant difference was found between groups in the Kruskal–Wallis test (H = 38.29, p < 0.0001), further suggesting that treatment and time post-inoculation decrease myelination. In COVID-19 positive animals pre-treated with saline, subjects show signs of demyelination as the myelination ranking is decreased at 6 days post-inoculation compared to both the negative control and 3 days post-inoculation; yet, the myelination ranking returns to negative control levels by day 10 post-inoculation (Saline: 3 Days vs. 6 Days, p = 0.0020; 3 Days vs. (−) control, p > 0.9999; 6 Days vs. (−) control, p = 0.1018; 10 Days vs. (−) control, p > 0.9999, post-hoc analyses). Ifenprodil pre-treatment resulted in an increased myelination ranking equivalent to negative control levels at 6 days post-inoculation compared to saline pre-treated animals (6 days: saline vs. ifenprodil, p = 0.0005; Ifenprodil: 6 Days vs. (−) control, p > 0.9999, post-hoc analyses), suggesting that ifenprodil prevents the COVID-19 induced demyelination at this timepoint. Further, no significant difference between myelination rankings of either memantine or ifenprodil pre-treated mice across any time point post-inoculation were observed, regardless of COVID-19 status. The lack of significant changes due to memantine pre-treatment suggests either no change or a possible reduction in demyelination compared to the negative control. By day 10 post-inoculation, no differences were observed between drug treatment groups. These findings suggest that ifenprodil, and possibly memantine, may prevent COVID-19 related changes in myelination in the respiratory centers of the brain.

NMDAR Antagonists Mitigate Myelination Deficits Induced by COVID-19 Infection. (a) Visualization of myelination in samples of medulla among key groups using black-gold II staining. Key groups include those sacrificed 10 days after COVID-19 inoculation, with representative images of samples either positive or negative for COVID-19 and treated with saline (control), memantine, or ifenprodil. Representative images for all other groups can be found in Supplementary Fig. 2. Each image is shown in the 4 × and 10 × magnification with anatomical markers labeled. (b) Examples of images representative of each semi-qualitative rank for Black-Gold II stain. (c) Representative Nissl (left) and anatomical annotations (right) from the Allen Brain Reference Atlases—Adult Mouse Brain showing i) pons and ii) medulla for reference119,120,121,122,123,124. (d) Black-Gold II Myelin semi-qualitative rankings according to time sacrificed post-virus inoculation and treatment group. Individual data points are representative of mode ranking values from sections in pons and medulla. Error bars represent mode qualitative ranking + /− S.E.M. Significant differences between groups are denoted with **p < 0.01. N = 5–18 sections per group.

No neuronal death is observed in COVID-19 infected pons and medulla

Along with the semi-quantitative data assessing morphology and myelination, COVID-19 induced cell death was evaluated, as well as the amelioration by NMDAR antagonism. Fluoro-jade C (FJC) was utilized to visualize neuronal death in the pons and medulla. Each section within the areas of interest were analyzed for fluorescent (FL) intensity. No significant differences between mean FL intensity were observed among groups, nor were there any clear patterns suggesting exposure to COVID-19, treatment with an NMDAR antagonist, or disease progression resulted in neuronal death (Supp Fig. S3C).

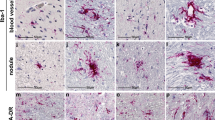

Both COVID-19 and NMDAR antagonist pre-treatment modulate astrocytic response

Immunofluorescent (IF) staining of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a structural protein specific to reactive astrocytes, was used to visualize and characterize astrocytes within the treatment groups (Fig. 5). In each group, pons and medulla tissue sections were assessed for mean GFAP FL Intensity. Representative images of GFAP staining at 10 days post-inoculation are shown in Fig. 5A. The GFAP data was first organized based on COVID-19 status and drug treatment, comparing only groups sacrificed on day 10 post-virus inoculation. Mean GFAP FL intensity was significantly increased in the COVID-19 positive saline group when compared to the negative saline control group (Saline: positive vs. negative, p = 0.0046, post-hoc analyses). Interestingly, mean GFAP FL intensity also was increased in comparison to the COVID-19 negative group pre-treated with NMDAR antagonists (Negative: saline vs. memantine, p = 0.0030; saline vs. ifenprodil, p = 0.0125, post-hoc analyses). Memantine and ifenprodil increased mean GFAP FL intensity (main effect of drug treatment F[2, 54] = 3.921, p = 0.0257; two-way ANOVA), dependent upon a group’s COVID-19 status (interaction F[2, 54] = 4.258, p = 0.0192). Our results indicate that pre-treatment with neither of the NMDAR antagonists blocked the effect of COVID-19 on GFAP expression at 10 days post-inoculation, however it is likely due to the fact that both COVID-19 infection and NMDAR antagonist pre-treatment increased GFAP signal.

Both COVID-19 and NMDAR Antagonist Pre-treatment Modulate Astrocytic Response. GFAP fluorescent (FL) Intensity. Data points are representative of sections in pons and medulla. (a) Images of sections representing immunofluorescent staining for GFAP from the medulla of a COVID-19 negative brain and COVID-19 positive brain from each key treatment group. Key groups include those sacrificed 10 days post-inoculation. (b) GFAP FL intensity of subjects negative for COVID-19 according to drug treatment. All animals were sacrificed 10 days post-virus inoculation. N = 5–18 sections per group. (c) GFAP FL intensity of COVID-19 Positive Saline treated subjects over time. N = 12–15 sections per group. (d) GFAP FL intensity of COVID-19 Positive Memantine treated subjects over time. N = 2–11 sections per group. (e) GFAP FL intensity of COVID-19 Positive Ifenprodil treated subjects over time. N = 10–14 sections per group. All results reported as mean FL intensity + /− S.E.M. with *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 as shown, and ## < 0.01 respective to Covid-19 Positive Saline Day 10.

Mean GFAP FL intensity was further analyzed based on time sacrificed post-virus inoculation and drug treatment in groups positive for COVID-19. Using a two-way ANOVA, we analyzed the differences in GFAP FL intensity between 3, 6, and 10 days post-inoculation across treatment groups. Time post-inoculation does in fact impact progression of GFAP FL intensity (main effect of time F(2,84) = 8.245, p = 0.0005; two-way ANOVA). While the two-way ANOVA does not show a treatment × time interaction (no interaction F(4,84) = 1.146, p = 0.3405), effect size analysis resulted in a partial eta-squared of 0.052, corresponding to a medium sized effect55, for treatment*time interaction. Effect size is often used as a measure of substantive significance56, thus, we followed up with post-hoc analyses, which suggest that disease progression did not have the same effect in subjects pre-treated with memantine as seen in groups pre-treated with saline and ifenprodil (Saline: 3 Days vs. 6 Days, p = 0.1328, 3 Days vs. 10 Days, p = 0.0064, 6 Days vs. 10 Days, p = 0.4678; Memantine: 3 Days vs. 6 Days, p = 0.9542, 3 Days vs. 10 Days, p = 0.7653, 6 Days vs. 10 Days, p = 0.8664; Ifenprodil: 3 Days vs. 6 Days, p = 0.8780, 3 Days vs. 10 Days, p< 0.0001, 6 Days vs. 10 Days, p = 0.0012, post-hoc analyses).

Both COVID-19 and NMDAR antagonist pre-treatment modulate microglial response

Similar to above, IF staining of ionized calcium-binding adapter molecules (IBA1), specific to microglia in the CNS, was used to visualize and characterize microglia within the treatment groups (Fig. 6). In each group, pons and medulla tissue sections were assessed for mean IBA1 FL intensity. Representative images of IBA1 staining at 10 days post-inoculation are shown in Fig. 6A. Again, IBA1 data was first separated by COVID-19 status and drug treatment, only using groups sacrificed on day 10 post-virus inoculation. Two-way ANOVA showed that positive or negative COVID-19 status influenced mean IBA1 FL intensity regardless of drug treatment (main effect of COVID status F[1, 58] = 19.02, p < 0.0001, no interaction F[2, 58] = 0.7979, p = 0.4552, two-way ANOVA). Mean IBA1 FL intensity was significantly decreased in the COVID-19 positive control group given saline when compared to the negative control group (Saline: positive vs. negative, p = 0.0018, post-hoc analyses). Mean IBA1 FL intensity was also significantly decreased in the positive memantine group when compared to the negative memantine group (Memantine: negative vs. positive, p = 0.0401, post-hoc analyses). At 10 days post-inoculation, no differences were observed between drug treatments in subjects either negative or positive for COVID-19.

Both COVID-19 and NMDAR Antagonist Pre-treatment Modulate Microglial Response. IBA1 fluorescent (FL) Intensity. Data points are representative of sections in pons and medulla. (a) Images of sections representing immunofluorescent staining for IBA1 from the medulla of a COVID-19 negative brain and COVID-19 positive brain from each key treatment group. Key groups include those sacrificed 10 days post-inoculation. (b) IBA1 FL intensity of subjects negative for COVID-19 according to drug treatment. All animals were sacrificed 10 days post-virus inoculation. N = 9–16 sections per group. (c) IBA1 FL intensity of COVID-19 Positive Saline treated subjects over time. N = 12–17 sections per group. (d) IBA1 FL intensity of COVID-19 Positive Memantine treated subjects over time. N = 7–10 sections per group. (e) IBA1 FL intensity of COVID-19 Positive Ifenprodil treated subjects over time. N = 9–17 sections per group. All results reported as mean FL intensity + /− S.E.M. with *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 as shown, ## < 0.01 respective to COVID-19 Positive Saline Day 10, and & < 0.05 respective to COVID-19 Positive Memantine Day 10.

Mean IBA1 FL intensity was also further analyzed based on time sacrificed post-virus inoculation and drug treatment in groups positive for COVID-19 using a two-way ANOVA of 3, 6, and 10 days. Again, time post-inoculation does alter progression of IBA1 FL intensity (main effect of time F(2,99) = 4.448, p = 0.0141; two-way ANOVA). While the two-way ANOVA does not show a treatment × time interaction (no interaction F(4,99) = 1.800, p = 0.1349), effect size analysis resulted in a partial eta-squared of 0.068, corresponding again to a medium sized effect, for treatment*time interaction. As mentioned, effect size can be used as a measure of substantive significance56, thus, we followed up with post-hoc analyses, which suggest that, similar to with GFAP, disease progression did not have the same effect in subjects pre-treated with memantine as seen in groups pre-treated with saline and ifenprodil (Saline: 3 Days vs. 6 Days, p = 0.1092, 3 Days vs. 10 Days, p = 0.0067, 6 Days vs. 10 Days, p = 0.6738; Memantine: 3 Days vs. 6 Days, p = 0.9864, 3 Days vs. 10 Days, p = 0.9939, 6 Days vs. 10 Days, p = 0.9259; Ifenprodil: 3 Days vs. 6 Days, p = 0.9557, 3 Days vs. 10 Days, p < 0.0096, 6 Days vs. 10 Days, p = 0.0317, post-hoc analyses).

Importantly, microglia have different functional phenotypes, allowing them to change morphologically based on their activation status and environment31. IF staining for IBA1 informs on microglial presence but cannot distinguish between activated or non-activated phenotypes57. Therefore, heightened IBA1 FL intensity would suggest morphological growth in cell size or increase in microglial numbers, not activation. Upon visual inspection of the IBA1 staining, COVID-19 negative groups appeared to exhibit a more ramified microglial morphological phenotype, while the COVID-19 positive groups display a more activated phenotypical appearance evidenced by the shortened ramifications and increased size of cell soma57. Together, these results suggest that both microglial depletion and activation may be occurring in the pons and medulla induced by COVID-19, and that NMDAR antagonism results in damped microglial expression throughout disease progression.

Discussion

NMDAR antagonists, including memantine, are used currently to treat Alzheimer’s Disease and vascular dementia, and are well-tolerated and safe in mice and humans43,58,59,60. Interestingly, clinical studies of patients with Alzheimer’s, dementia, or Parkinson’s who are currently medicated with NMDAR antagonists seemingly show reduced incidence and severity of COVID-19 infection39,40,41,42. Given this population is generally regarded as “high risk”, the present study examined whether this protective effect in older patients with neurological dysfunction was due to the actions of their concurrent clinically prescribed NMDAR therapeutics. Indeed, we found that memantine treatment significantly improved survival in mice positive for COVID-19. Furthermore, both memantine and ifenprodil treatment appear to reduce observable signs of disease (i.e., decreased body weight). The current observations support the further investigation of NMDAR antagonists in the prevention of COVID-19 related death and disease, specifically pre-treatment with memantine. The current results also warrant further exploration of the neurological biochemistry of COVID-19 and the effects of both memantine and ifenprodil on COVID-19 related neurological alterations.

Excitotoxicity is the overactivation of NMDARs which causes cell damage and contributes to pro-inflammatory environments20. It is induced by excessive glutamate, which binds to NMDARs to produce excitatory events49. Glutamate-related excitotoxic insult creates a positive feedback loop of glutamate release that can persist and cause further damage even after glutamate is cleared, causing even more delayed excitotoxicity61,62. This lasting NMDAR related damage may contribute to the variability in recovery rates from COVID-19, possibly due to repeated interference with glial cells as excitotoxicity has been associated with microglia and astrocyte activation63,64. For example, under normal physiologic conditions, astrocytes play a vital role in maintaining extracellular glutamate levels65. In neuroinflammatory environments, astrocytes are unable to maintain homeostatic levels of glutamate, causing excitotoxicity66,67. Memantine induced NMDAR antagonism is expected to have neuroprotective effects in excitotoxic and proinflammatory environments43,44,45, yet it remains unclear whether and how the chosen NMDAR antagonists impact COVID-19 induced changes to microglial/astrocytic-related excitotoxicity.

Astrocytes are infected by SARS-CoV-2 preferentially over neurons and microglia68,69. Thus, an increase in GFAP is expected upon inoculation. Interestingly, memantine is anti-inflammatory and increases astrocyte functionality promoting neuronal growth, while also inhibiting activation of microglia in the midbrain44. The proposed increase in astrocyte functionality would explain the increase in GFAP FL intensity associated with NMDAR antagonist pre-treatment in COVID-19 negative subjects, as well as the lack of alterations to astrocyte expression in COVID-19 positive subjects treated with an NMDAR antagonist. There are commonalities among astrocyte reactivity, such as up-regulation of GFAP and increase in cell size34,35,70, but importantly, GFAP staining only indicates the presence of reactive astrocytes, not the underlying function of reactivity. While infection with COVID-19 induces astrocyte reactivity, that is also induced by NMDAR antagonism, the functionality of the astrocytes is not clear, and may differ between groups.

Reactive astrocytes are not the only cells implicated in COVID-19. Neuroinflammation and COVID-19 infection has been linked to proliferation of microglia71,72. Interestingly, our results establish an opposing pattern with GFAP FL intensity increasing and IBA1 FL intensity decreasing with progression of COVID-19 infection (Figs. 5 and 6), which is in contrast with other reports of both increased astrocyte and microglial signal after infection with COVID-1968,72. This phenomenon could be due to the crosstalk between astrocytes and microglia, activating a compensatory mechanism in response to impaired microglial activity73. Previous studies have shown that infections, such as herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) or human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1), can cause microglial pryoptosis, a type of inflammatory programmed cell death74, contributing to the neuropathology observed in these illnesses75,76. Astrocytes have been shown to be activated due to the depletion of microglia and will phagocytose microglial fragments77,78. If microglia are impaired due to COVID-19 infection, astrocytes would become activated and compensate for microglial damage. This process is unique to astrocytes and provides one explanation for an increasing reactive astrocyte signal in combination with a decreasing microglia signal.

As noted, microglia are known to display different morphologies based on their functional phenotype31. In the current study, staining of IBA1 revealed that while FL intensity of IBA1 may be decreased in the COVID-19 positive groups, a difference in the morphological phenotypes was observed between groups (Fig. 6A). Microglia of subjects not inoculated with COVID-19 appeared to be in a resting state with smaller cell soma and more longer branched processes, while microglia of subjects positive for COVID-19 had an increased cell soma and lessened ramifications, appearing to be activated57. While IBA1 expression is generally positively correlated with activation of microglia79, current literature suggests that the activation of microglia may not always be accompanied by increased IBA1 expression80,81,82, and that levels of expression of certain markers such as IBA1 can change depending on the functional state of microglia80. Thus, with the corresponding increase in reactive astrocyte expression in the COVID-19 positive groups, it is plausible that activated astrocytes may be clearing damaged microglial fragments in the COVID-19 positive groups, contributing to the observed decreased expression of IBA1.

An increase in activation of microglia indicates increased expression of cytokines and chemokines30,31, i.e. a cytokine storm, characteristic of COVID-19 and other infections26,27,28,29, as expected of the COVID-19 positive groups. Increased proinflammatory cytokines downregulate mechanisms important for glutamate recycling83,84,85,86,87, such as glial glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1) or glutamine synthetase (GS), both mainly expressed in astrocytes45,88,89,90,91. Thus, this increased microglial activation in COVID-19 positive groups may lead to excitotoxicity via cytokine-induced downregulation of glutamate recycling. However, blocking NMDARs with therapeutic levels of memantine has neuroprotective effects by reducing microglia-associated inflammation43,44. In the current study, the least expression of IBA1 over the time course of disease progression occurred in the animals pre-treated with memantine (Fig. 6). In a prior study from Brison and colleagues where memantine also attenuated mortality rates and body weight loss in a similar murine coronavirus model, memantine was shown to restore GLT-1 and GS expression45. This indicates that memantine may mitigate the subsequent cytokine storm characteristic of microglial activation. In concert, the current results indicate that there are differences in the compensatory mechanisms between astrocytes and microglia that may result in the same outcome of expression but different functionality after COVID-19 infection and pre-treatment with an NMDAR antagonist. Follow-up studies, such as identifying markers for M1/M2 polarization, need to be performed to confirm the activation and functionality of astrocytes and microglia in the context of COVID-19 and NMDAR antagonism.

As COVID-19 related neuronal injury is hypothesized to be due to immune-mediated mechanisms, it is possible that the observed changes in astrocyte and microglial expression may be impacting morphology and myelination outcomes as well. SARS-CoV-2 preferentially infects cortical astrocytes over cortical neurons and microglia; however, there is no increase in astrocytic cell death as a result68. Therefore, astrocyte infection with COVID-19 has been hypothesized to indirectly causes neuronal death68,69. Interestingly, the current results show that exposure to COVID-19 or pre-treatment with NMDAR antagonists did not impact neuronal death in the pons or medulla (SuppFig. S3C). Neuronal injury may occur without cell death92, and morphological changes such as dendritic injury or loss without neuronal cell body loss (i.e. dendritic pruning) may alternatively indicate reversible neuronal damage93. Further, dendritic spine loss and alterations may be related to microglial activation94, which is observed and expected due to COVID-19 infection71,72. In the presence of COVID-19 infection, brain morphology changes have been reported in the cerebral cortex of humans69,95. Similarly, the current results show that over time, COVID-19 infection may result in dampened morphology in respiratory regions of the brain; however, NMDAR antagonism rescues these morphological changes (Fig. 3). Reversible cell damage is characterized by the injured cell’s ability to regain homeostasis and return to a morphologically and functionally normal state96. Thus, the observed morphological changes may be considered a marker of potentially reversible cell injury, rather than a sign of cell death. The current findings suggest that pre-treatment with an NMDAR antagonist reduces the severity of the observed COVID-19 induced morphological changes and leads to the reversal of neuronal injury that may be occurring.

Neuronal damage may also be evidenced by demyelination, a process heavily influenced by inflammatory responses involving astrocytes21,34. As astrocytes are invaded by SARS-CoV-2 inducing a proinflammatory response, disruptions in myelination can occur and have been reported34,38,97. Our results are consistent with the literature, as loss of myelinated axons in mice following COVID-19 infection has been reported in subcortical white matter in murine subjects as early as 7 days post-infection and persisted for at least 7 weeks30. Human studies have shown neurological presentation of demyelination at a range of times post-infection, from a few days to a few weeks98. Surprisingly, by day 10 post-inoculation, myelin levels seem to return to baseline in COVID-19 positive subjects. Accelerated remyelination may occur after inflammatory demyelination to prevent axonal loss and support neuronal function99,100,101. Interestingly, pre-treatment with ifenprodil showed no differences with COVID-19 inoculation or time course. Memantine treated groups showed similar promise, as neither group showed the same significant demyelination compared to controls as the saline treated subjects (Fig. 4). Evidence from the literature supports that both memantine102,103,104 and ifenprodil105,106 may attenuate inflammatory induced demyelination. It should also be noted that anti-NMDAR antibodies have been associated with acute demyelinating encephalitis (ADEM), a neurological complication observed in some COVID-19 patients107,108,109. In such cases, high dose NMDAR antagonists may exacerbate signs of neuronal injury. Nonetheless, the current findings suggest that NMDAR antagonism may improve myelination deficits related to COVID-19.

While both memantine and ifenprodil are NMDAR antagonists, their neuroprotective effects may differ due to variations in receptor selectivity and downstream signaling47. Notably, while both compounds improved survival and reduced disease severity, memantine appeared to have a more pronounced effect on mitigating morphological deficits and neuroimmune responses (Figs. 3, 5 and 6), suggesting that its broader NMDAR blockade may provide more extensive neuroprotection in the context of COVID-19. Despite these valuable insights gained from this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. While this study has a relatively small sample size (n = 5 per group), which can limit the statistical power of the findings, the early stage of these investigations give rationale for further future study. Another caveat relates to the COVID-19 exposure model, because tissue from animals euthanized for endpoint criteria was not collected at specified time points, thus presenting a challenge in assessing temporal changes in disease progression. Beyond these methodological considerations, this study also has caveats common to most studies translationally modeling clinical disease. This includes differences in the time course of COVID-19 response and myelination processes between species, potentially impacting the relevance of these results to human disease. Additionally, caution is needed when extrapolating drug exposure and therapeutic efficacy from mouse models to human populations, as differences in pharmacokinetics and disease pathology may alter treatment outcomes. These factors highlight the complexity of translating preclinical results into clinical applications and emphasize the need for further studies in larger animal models and clinical trials to validate the therapeutic potential of NMDAR antagonists in COVID-19-related neurological injury. Finally, the current findings raise important questions regarding the timing of NMDAR antagonist administration. Pre-treatment with memantine or ifenprodil appeared to provide neuroprotection and reduce COVID-19-related mortality, but it remains unclear whether similar benefits would be observed with post-infection treatment. While the focus of the current study looked to assess the protective effects of NMDAR antagonists on disease progression, we acknowledge that the predominant acute application of these compounds would likely be for treatment in individuals already COVID-19-positive, but further study is necessary for that application. Given that NMDAR-mediated excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation play a significant role in disease progression, early intervention may be critical in preventing long-term damage. Literature suggests that delayed treatment with NMDAR antagonists may be less effective once excitotoxic and inflammatory cascades are established, since prolonged excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation may become irreversible or induce further damage46,58,59,62,63,64,65. Future studies should investigate whether post-infection administration of these compounds can still provide neuroprotection and to what extent treatment timing influences disease outcomes.

In conclusion, the current study shows an increased inflammatory response to COVID-19 exposure in the pons and medulla, as evidenced by altered morphology, demyelination, and astrocytic/microglial expression and activation. Our findings suggest that the neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19 could be a result of the neuroinflammation within the pons and medulla. Therefore, pre-treatment (either prophylactically in high-risk patients, or early after exposure) with an NMDAR antagonist such as memantine or ifenprodil may be useful for the prevention of neuronal damage due to COVID-19, as well as progression to more severe clinical manifestations of COVID-19.

Methods

Animal subjects

Adult (8-week-old), female, K18-hACE2 transgenic mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories ((B6.Cg-Tg(K18-ACE2)2Prlmn/J), Jax strain no. 034860) and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. Animals were randomly housed in groups of 5 upon arrival. All experimental procedures were followed in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC), and all methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. Cages were randomly assigned into the 12 treatment groups, with n = 5 in each group. Groups 1–4 were pretreated with saline, with groups 2–4 receiving intranasal inoculation of SARS-CoV-2, Beta variant, 1-week post-treatment initiation. Groups 5–8 were pretreated with memantine (10 mg/kg I.P. twice daily), and groups 6–8 were inoculated with the same virus 1 week later. Groups 9–12 were pretreated with ifenprodil (10 mg/kg I.P. twice daily), and groups 10–12 were inoculated with the same virus 1 week later. Therefore, groups 1, 5, and 9 were not inoculated with COVID-19 allowing for controlled comparisons within each treatment. To understand how disease progression affects the neuropathology examined in this study, groups were sacrificed at different time points. Groups 2, 6, and 10 were sacrificed 3 days after virus inoculation. Groups 3, 7, and 11 were sacrificed on day 6 post-inoculation and the remaining were sacrificed on day 10. Experimental design, including COVID-19 inoculation status, treatment, time course for each group is shown in Fig. 1.

Drugs and administration

COVID-19 infection

All experiments with SARS-CoV-2 were performed in enhanced biosafety level 3 (BSL3) containment laboratories at the University of Louisville, which are approved for such use by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and by the US Department of Agriculture. Mice were exposed to 2 × 104 pfu of SARS-CoV-2, Beta variant (B.1.351 South African/KRISP-EC-K005321/2020, BEI: NR-54008) via intranasal inoculation, as previously described110. Briefly, the inoculum was administered by placing it dropwise on the tip of the nose over both nares allowing it to be inhaled during inspiration. The virus was obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: SARS-Related Coronavirus 2, Isolate HCoV-19/South Africa/KRISP-EC-K005321/2020, NR-54008, contributed by Alex Sigal and Tulio de Oliveira. Following inoculation with SARS-CoV-2, animals were monitored throughout the experiment for observable health effects, including change in body weight and survival outcomes.

NMDAR antagonists

Mice were injected twice daily (intraperitoneal (I.P.)) with either saline, memantine (10 mg/kg), or ifenprodil (10 mg/kg) for 1 week prior to inoculation. Doses were chosen based on available published preclinical data relating to neuropharmacology, as well as available PK data for allometric scaling111,112,113,114,115,116,117. Injections began 1 week prior to COVID-19 exposure to reach steady-state plasma concentrations of the compounds and continued twice daily (BID) until the assigned tissue collection day (Fig. 1).

Tissue collection, fixation, and slicing

Mice were deeply anesthetized with an isoflurane/oxygen vapor mixture (5%) and euthanized via exsanguination. After exsanguination, they were perfused with 40 ml of 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF; ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The brains were removed and placed in the same fixative for 48–72 h at room temperature, followed by cryoprotection in 30% sucrose for 3 days at 4 °C before storage at − 80 °C. In vivo exposure to CoV-2 and tissue collection were conducted at the University of Louisville BSL-3 facility. Following validation of viral load eradication, tissues were shipped to the University of Kentucky for biochemical analyses.

The right hemisphere of each fixed brain was sectioned coronally through the entire structure using a cryostat with a fine section set to 45 nm. Slices corresponding to the pons (AP − 4.15 to − 5.33) and medulla (AP − 5.41 to − 8.00), were collected in a 12-well plate filled with 0.1% sodium azide (1 g sodium azide mixed into 100 mL 10 × PBS and 900 mL of distilled water in laboratory fume hood; ThermoFisher Scientific, CAS 26628-22-8) and stored in 4 °C fridge. Slices were mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides (ThermoFisher Scientific) in a distilled water bath prior to staining. Slides were air dried overnight to allow for tissue adhesion. During transfer of tissues between institutions, some samples were rendered nonviable and unsuitable for extended sectioning in the required regions. This limited the number of slices available for analysis, and, consequently, the number of slices differs between groups.

Staining techniques

Cresyl violet

To assess gross morphology, cresyl violet staining was utilized for each group. The staining procedure was completed in a laboratory fume hood to limit exposure to hazardous reagents. 1.25 g of cresyl violet acetate (Acrōs Organics, Geel, Belgium) was dissolved in 250 mL of warm distilled water. Glacial acetic acid (30 nM; ThermoFisher Scientific, CAS 64-19-7) was added to the mixture, which was then cooled and filtered. Slides were immersed in a descending alcohol series to allow for rehydration prior to staining: 100% ethanol, followed by 95%, 70%, then distilled water to rinse. Sections were stained in cresyl violet solution for 3 min. Slides were rinsed with distilled water and dehydrated in an ascending alcohol series (i.e. reverse order of ethanol dehydration). Finally, slides were cleared in CitriSolv (Decon Labs, King of Prussia, PA, USA. CAS 5989-27-5) for 5 min, coverslipped with Vectamount mounting medium (Vector, Cat. H-500, Newark, CA, USA), and imaged using bright field microscopy.

Black-gold II myelin

To visualize potential demyelination, a set of adjacent sections from each group were stained with Black-Gold II Myelin Stain Reagent with Toluidine Blue O Counter Stain kit (Biosensis, Thebarton, SA, Australia; Cat. TR-100-BG) according to manufacturer instructions. Slides were imaged using bright field microscopy to estimate myelination in each group.

Fluoro-Jade C

To visualize cell death, a set of adjacent sections from each group were stained with Fluoro-Jade C Stain kit (Biosensis, Thebarton, SA, Australia; Cat. TR-100-FJT) according to manufacturer instructions. The staining procedure was completed in a laboratory fume hood to limit exposure to hazardous reagents. The slides were imaged using the appropriate fluorescent microscopy settings on the Zeiss Slide Scanner Axioscan Z7.

Immunofluorescence

Another set of adjacent sections from each group were processed for GFAP and IBA-1 immunofluorescence (IF) to visualize astrocytes and microglia, respectively. Sections undergoing GFAP IF were incubated in Rabbit anti-GFAP primary antibody, DAKO#Z033401-2 (1:1000, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) overnight, followed by a 2-h incubation in Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Flour™ 488, #A11008 (1:500, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Similarly, sections undergoing IBA-1 IF were incubated overnight in goat anti-IBA-1, Wako #019-19741 primary antibody (1:2500, FUIJFILM, Minato City, Tokyo, Japan) then for 1 h in Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Flour™ Plus 647, #A32733 (1:500, Invitrogen). Imaging was completed for each IF stain using the appropriate fluorescent microscopy settings on the Zeiss Slide Scanner Axioscan Z7.

Analysis

General morphological stains, such as cresyl violet and Black-Gold II Myelin, were utilized as a semi-quantitative measure of neuropathology visualized in the respiratory centers of the brain. A ranking system assessing the visibility of the stain was developed to analyze these images. Nine individuals blinded to the treatment groups ranked stains with a value corresponding to visual assessment of morphology and myelination, respectively. Consistency was ensured by having the blinded individuals rank the images on a single screen, allowing them to view all images simultaneously. The mode of ranks across all nine blinded observers were used to determine visual differences between treatment groups for both stains. In the case of the Fluoro-Jade C and IF stains, the images underwent processing through Zeiss software (ZEN Desk 2.5) which included deconvolution and background subtraction. Then, using National Institutes of Health ImageJ software, regions of interests (ROIs) were drawn around either pons or medulla on respective images and mean intensity was taken from ImageJ for collective mean across groups. All statistical analyses were done in GraphPad Prism 10.2.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Each experimental procedure was analyzed using two-way ANOVAs unless otherwise stated. All ANOVAs were followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison tests, even in the absence of significant interactions. Extensive prior statistical literature demonstrates that post-hoc multiple comparison tests, while typically performed at the same time as ANOVA calculations, are in fact not dependent upon ANOVA significant interaction effects118. Nonlinear regression analyses were completed for Body Weight results to identify differences in weight between treatments over time.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Hung, E. C. et al. Detection of SARS coronavirus RNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin. Chem. 49, 2108–2109. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2003.025437 (2003).

Yeh, E. A., Collins, A., Cohen, M. E., Duffner, P. K. & Faden, H. Detection of coronavirus in the central nervous system of a child with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Pediatrics 113, e73–e76. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.1.e73 (2004).

Umakanthan, S. et al. Origin, transmission, diagnosis and management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Postgrad. Med. J. 96, 753–758. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138234 (2020).

Chen, N. et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet 395, 507–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 (2020).

Harapan, B. N. & Yoo, H. J. Neurological symptoms, manifestations, and complications associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19). J. Neurol. 268, 3059–3071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10406-y (2021).

Shehata, G. A. et al. Neurological complications of COVID-19: Underlying mechanisms and management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(8), 4081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22084081 (2021).

Mao, L. et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan China. JAMA Neurol. 77, 683–690. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127 (2020).

Meinhardt, J. et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5 (2021).

Li, Y. C., Bai, W. Z. & Hashikawa, T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J. Med. Virol. 92, 552–555. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25728 (2020).

Song, W. J. et al. Confronting COVID-19-associated cough and the post-COVID syndrome: Role of viral neurotropism, neuroinflammation, and neuroimmune responses. Lancet Respir. Med. 9, 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00125-9 (2021).

Hoffmann, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 (2020).

Cantuti-Castelvetri, L. et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science 370, 856–860. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd2985 (2020).

Daly, J. L. et al. Neuropilin-1 is a host factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science 370, 861–865. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd3072 (2020).

Avdonin, P. P., Rybakova, E. Y., Trufanov, S. K. & Avdonin, P. V. SARS-CoV-2 receptors and their involvement in cell infection. Biochem. (Mosc) Suppl. Ser. A Membr. Cell Biol. 17, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1990747822060034 (2023).

Jackson, C. B., Farzan, M., Chen, B. & Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-021-00418-x (2022).

Butowt, R. & von Bartheld, C. S. The route of SARS-CoV-2 to brain infection: Have we been barking up the wrong tree? Mol. Neurodegener. 17, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-022-00529-9 (2022).

Bilinska, K., von Bartheld, C. S. & Butowt, R. Expression of the ACE2 virus entry protein in the nervus terminalis reveals the potential for an alternative route to brain infection in COVID-19. Front. Cell Neurosci. 15, 674123. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2021.674123 (2021).

Ortiz, M. E. et al. Heterogeneous expression of the SARS-coronavirus-2 receptor ACE2 in the human respiratory tract. EBioMedicine 60, 102976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102976 (2020).

Gao, C. C. et al. Differential transcriptomic landscapes of multiple organs from SARS-CoV-2 early infected rhesus macaques. Protein Cell 13, 920–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-022-00915-5 (2022).

Wan, D. et al. Neurological complications and infection mechanism of SARS-COV-2. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 6, 406. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00818-7 (2021).

Vitale-Cross, L., Szalayova, I., Scoggins, A., Palkovits, M. & Mezey, E. SARS-CoV-2 entry sites are present in all structural elements of the human glossopharyngeal and vagal nerves: Clinical implications. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.30.474580 (2022).

Ellenberger, H. H. & Feldman, J. L. Brainstem connections of the rostral ventral respiratory group of the rat. Brain Res. 513, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(90)91086-v (1990).

Basinger, H. & Hogg, J. P. in StatPearls (2024).

Netland, J., Meyerholz, D. K., Moore, S., Cassell, M. & Perlman, S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J. Virol. 82, 7264–7275. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00737-08 (2008).

Class, J. et al. Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in the murine central nervous system drives viral diversification. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 2383–2394. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01786-8 (2024).

Riyaz Tramboo, S. et al. The critical impacts of cytokine storms in respiratory disorders. Heliyon 10, e29769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29769 (2024).

Ragab, D., Salah Eldin, H., Taeimah, M., Khattab, R. & Salem, R. The COVID-19 cytokine storm; What we know so far. Front. Immunol. 11, 1446. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01446 (2020).

Chen, G. et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 2620–2629. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI137244 (2020).

Huang, C. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan China. Lancet 395, 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 (2020).

Fernandez-Castaneda, A. et al. Mild respiratory COVID can cause multi-lineage neural cell and myelin dysregulation. Cell 185, 2452–2468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.008 (2022).

Woodburn, S. C., Bollinger, J. L. & Wohleb, E. S. The semantics of microglia activation: Neuroinflammation, homeostasis, and stress. J. Neuroinflam. 18, 258. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-021-02309-6 (2021).

Skaper, S. D., Facci, L., Zusso, M. & Giusti, P. An inflammation-centric view of neurological disease: Beyond the neuron. Front. Cell Neurosci. 12, 72. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2018.00072 (2018).

Paolicelli, R. C. et al. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science 333, 1456–1458. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1202529 (2011).

Lee, H. G., Lee, J. H., Flausino, L. E. & Quintana, F. J. Neuroinflammation: An astrocyte perspective. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eadi7828. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.adi7828 (2023).

Lawrence, J. M., Schardien, K., Wigdahl, B. & Nonnemacher, M. R. Roles of neuropathology-associated reactive astrocytes: A systematic review. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 11, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-023-01526-9 (2023).

Joshi, A. U. et al. Fragmented mitochondria released from microglia trigger A1 astrocytic response and propagate inflammatory neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 1635–1648. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-019-0486-0 (2019).

Liddelow, S. A. et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 541, 481–487. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21029 (2017).

Monje, M. & Iwasaki, A. The neurobiology of long COVID. Neuron 110, 3484–3496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2022.10.006 (2022).

Rejdak, K. & Grieb, P. Adamantanes might be protective from COVID-19 in patients with neurological diseases: Multiple sclerosis, Parkinsonism and cognitive impairment. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 42, 102163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2020.102163 (2020).

Artusi, C. A. et al. COVID-19 and Parkinson’s disease: What do we know so far? J. Parkinsons Dis. 11, 445–454. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-202463 (2021).

Cortes-Borra, A. & Aranda-Abreu, G. E. Amantadine in the prevention of clinical symptoms caused by SARS-CoV-2. Pharmacol. Rep. 73, 962–965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43440-021-00231-5 (2021).

Muller, T., Riederer, P. & Kuhn, W. Aminoadamantanes: From treatment of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease to symptom amelioration of long COVID-19 syndrome? Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 16, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512433.2023.2176301 (2023).

Volbracht, C., van Beek, J., Zhu, C., Blomgren, K. & Leist, M. Neuroprotective properties of memantine in different in vitro and in vivo models of excitotoxicity. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 2611–2622. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04787.x (2006).

Wu, H. M. et al. Novel neuroprotective mechanisms of memantine: increase in neurotrophic factor release from astroglia and anti-inflammation by preventing microglial activation. Neuropsychopharmacology 34, 2344–2357. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.64 (2009).

Brison, E., Jacomy, H., Desforges, M. & Talbot, P. J. Novel treatment with neuroprotective and antiviral properties against a neuroinvasive human respiratory virus. J. Virol. 88, 1548–1563. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02972-13 (2014).

Rogawski, M. A. & Wenk, G. L. The neuropharmacological basis for the use of memantine in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drug Rev. 9, 275–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-3458.2003.tb00254.x (2003).

Mony, L., Kew, J. N., Gunthorpe, M. J. & Paoletti, P. Allosteric modulators of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Br. J. Pharmacol. 157, 1301–1317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00304.x (2009).

Fischler, P. V., Soyka, M., Seifritz, E. & Mutschler, J. Off-label and investigational drugs in the treatment of alcohol use disorder: A critical review. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 927703. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.927703 (2022).

Paoletti, P. & Neyton, J. NMDA receptor subunits: Function and pharmacology. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 7, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2006.08.011 (2007).

Zhou, Y. et al. Efficacy of ion-channel inhibitors amantadine, memantine and rimantadine for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Viruses 13(10), 2082. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13102082 (2021).

Harandi, A. A. et al. A randomized open-label clinical trial on the effect of Amantadine on post Covid 19 fatigue. Sci. Rep. 14, 1343. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51904-z (2024).

Aranda-Abreu, G. E., Aranda-Martinez, J. D. & Araujo, R. Use of amantadine in a patient with SARS-CoV-2. J. Med. Virol. 93, 110–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26179 (2021).

Pharmaceuticals, A. (ed Novotech) (2020).

NIH. Guidelines for Endpoints in Animal Studies. (National Institute of Health, nih.gov, 2022).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences 2nd edn. (Routledge, 1988).

Sullivan, G. M. & Feinn, R. Using effect size-or why the P value is not enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 4, 279–282. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-12-00156.1 (2012).

Lier, J., Streit, W. J. & Bechmann, I. Beyond activation: Characterizing microglial functional phenotypes. Cells 10(9), 2236. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10092236 (2021).

Parsons, C. G., Danysz, W. & Quack, G. Memantine is a clinically well tolerated N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist–a review of preclinical data. Neuropharmacology 38, 735–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00019-2 (1999).

Lipton, S. A. Paradigm shift in neuroprotection by NMDA receptor blockade: Memantine and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1958 (2006).

Reisberg, B. et al. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1333–1341. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa013128 (2003).

Dvoriantchikova, G., Fleishaker, M. & Ivanov, D. Molecular mechanisms of NMDA excitotoxicity in the retina. Sci. Rep. 13, 18471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45855-0 (2023).

Norris, C. M. et al. Electrophysiological mechanisms of delayed excitotoxicity: Positive feedback loop between NMDA receptor current and depolarization-mediated glutamate release. J. Neurophysiol. 96, 2488–2500. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00593.2005 (2006).

Haroon, E., Miller, A. H. & Sanacora, G. Inflammation, glutamate, and glia: A trio of trouble in mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.199 (2017).

Iovino, L., Tremblay, M. E. & Civiero, L. Glutamate-induced excitotoxicity in Parkinson’s disease: The role of glial cells. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 144, 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphs.2020.07.011 (2020).

Rothstein, J. D. et al. Knockout of glutamate transporters reveals a major role for astroglial transport in excitotoxicity and clearance of glutamate. Neuron 16, 675–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80086-0 (1996).

Hardin-Pouzet, H. et al. Glutamate metabolism is down-regulated in astrocytes during experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Glia 20, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199705)20:1%3c79::aid-glia8%3e3.0.co;2-0 (1997).

Werner, P., Pitt, D. & Raine, C. S. Multiple sclerosis: Altered glutamate homeostasis in lesions correlates with oligodendrocyte and axonal damage. Ann. Neurol. 50, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.1077 (2001).

Andrews, M. G. et al. Tropism of SARS-CoV-2 for human cortical astrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119, e2122236119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2122236119 (2022).

Crunfli, F. et al. Morphological, cellular, and molecular basis of brain infection in COVID-19 patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119, e2200960119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2200960119 (2022).

Sofroniew, M. V. Astrogliosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7, a020420. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a020420 (2014).

Jordao, M. J. C. et al. Single-cell profiling identifies myeloid cell subsets with distinct fates during neuroinflammation. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat7554 (2019).

Boroujeni, M. E. et al. Inflammatory response leads to neuronal death in human post-mortem cerebral cortex in patients with COVID-19. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 12, 2143–2150. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00111 (2021).

Sun, M. et al. Microglia-astrocyte interaction in neural development and neural pathogenesis. Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12151942 (2023).

Matsudaira, T. & Prinz, M. Life and death of microglia: Mechanisms governing microglial states and fates. Immunol. Lett. 245, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imlet.2022.04.001 (2022).

He, X. et al. NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis is required for HIV-1 gp120-induced neuropathology. Cell Mol. Immunol. 17, 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-019-0260-y (2020).

Hu, X. et al. Herpes simplex virus 1 induces microglia gasdermin D-dependent pyroptosis through activating the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome. Front. Microbiol. 13, 838808. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.838808 (2022).

Zhou, T. et al. Microglial debris is cleared by astrocytes via C4b-facilitated phagocytosis and degraded via RUBICON-dependent noncanonical autophagy in mice. Nat. Commun. 13, 6233. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33932-3 (2022).

Konishi, H. et al. Astrocytic phagocytosis is a compensatory mechanism for microglial dysfunction. EMBO J. 39, e104464. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2020104464 (2020).

Ito, D. et al. Microglia-specific localisation of a novel calcium binding protein, Iba1. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 57, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00040-0 (1998).

Walker, D. G. & Lue, L. F. Immune phenotypes of microglia in human neurodegenerative disease: Challenges to detecting microglial polarization in human brains. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 7, 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-015-0139-9 (2015).

Shi, F. J. et al. Is Iba-1 protein expression a sensitive marker for microglia activation in experimental diabetic retinopathy. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 14, 200–208. https://doi.org/10.18240/ijo.2021.02.04 (2021).

Hopperton, K. E., Mohammad, D., Trepanier, M. O., Giuliano, V. & Bazinet, R. P. Markers of microglia in post-mortem brain samples from patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 177–198. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.246 (2018).

Carmen, J., Rothstein, J. D. & Kerr, D. A. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha modulates glutamate transport in the CNS and is a critical determinant of outcome from viral encephalomyelitis. Brain Res. 1263, 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2009.01.040 (2009).

Okada, K., Yamashita, U. & Tsuji, S. Modulation of Na(+)-dependent glutamate transporter of murine astrocytes by inflammatory mediators. J. UOEH 27, 161–170. https://doi.org/10.7888/juoeh.27.161 (2005).

Prow, N. A. & Irani, D. N. The inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1 beta, mediates loss of astroglial glutamate transport and drives excitotoxic motor neuron injury in the spinal cord during acute viral encephalomyelitis. J. Neurochem. 105, 1276–1286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05230.x (2008).

Huang, T. L. & O’Banion, M. K. Interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha suppress dexamethasone induction of glutamine synthetase in primary mouse astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 71, 1436–1442. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71041436.x (1998).

Zou, J. et al. Glutamine synthetase down-regulation reduces astrocyte protection against glutamate excitotoxicity to neurons. Neurochem. Int. 56, 577–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2009.12.021 (2010).

Anderson, C. M. & Swanson, R. A. Astrocyte glutamate transport: Review of properties, regulation, and physiological functions. Glia 32, 1–14 (2000).

Albrecht, J., Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz, M., Zielinska, M. & Aschner, M. Roles of glutamine in neurotransmission. Neuron Glia Biol. 6, 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740925X11000093 (2010).

Norenberg, M. D. Distribution of glutamine synthetase in the rat central nervous system. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 27, 756–762. https://doi.org/10.1177/27.3.39099 (1979).

Norenberg, M. D. & Martinez-Hernandez, A. Fine structural localization of glutamine synthetase in astrocytes of rat brain. Brain Res. 161, 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(79)90071-4 (1979).

Chi, H., Chang, H.-Y. & Sang, T.-K. Neuronal cell death mechanisms in major neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19(10), 3082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19103082 (2018).

J.A. Rumbaugh, A. N. in Encyclopedia of Neuroscience (ed M.D. Binder, Hirokawa, N., Windhorst, U.) (Springer, 2009).

Dorostkar, M. M., Zou, C., Blazquez-Llorca, L. & Herms, J. Analyzing dendritic spine pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: Problems and opportunities. Acta Neuropathol. 130, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1449-5 (2015).

Politi, L. S., Salsano, E. & Grimaldi, M. Magnetic resonance imaging alteration of the brain in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and anosmia. JAMA Neurol. 77, 1028–1029. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2125 (2020).

Zachary, M. A. M. a. J. F. in Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease (ed James F. Zachary) Ch. 1, (2017).

Reichard, R. R. et al. Neuropathology of COVID-19: A spectrum of vascular and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)-like pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 140, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-020-02166-2 (2020).

Ismail, I. I. & Salama, S. Association of CNS demyelination and COVID-19 infection: An updated systematic review. J. Neurol. 269, 541–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10752-x (2022).

Neumann, B., Segel, M., Chalut, K. J. & Franklin, R. J. Remyelination and ageing: Reversing the ravages of time. Mult. Scler. 25, 1835–1841. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458519884006 (2019).

Mei, F. et al. Accelerated remyelination during inflammatory demyelination prevents axonal loss and improves functional recovery. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18246 (2016).

Irvine, K. A. & Blakemore, W. F. Remyelination protects axons from demyelination-associated axon degeneration. Brain 131, 1464–1477. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awn080 (2008).

Yick, L. W., Tang, C. H., Ma, O. K., Kwan, J. S. & Chan, K. H. Memantine ameliorates motor impairments and pathologies in a mouse model of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. J. Neuroinflam. 17, 236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-020-01913-2 (2020).

Alomar, S. Y. et al. Novel mechanism for memantine in attenuating diabetic neuropathic pain in mice via downregulating the spinal HMGB1/TRL4/NF-kB inflammatory axis. Pharmaceuticals 14(4), 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14040307 (2021).

Dong, H., Yuede, C. M., Coughlan, C., Lewis, B. & Csernansky, J. G. Effects of memantine on neuronal structure and conditioned fear in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 3226–3236. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2008.53 (2008).

Fontaine, R. H. et al. Vulnerability of white matter towards antenatal hypoxia is linked to a species-dependent regulation of glutamate receptor subunits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 16779–16784. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0803004105 (2008).

Manousi, A. et al. Identification of novel myelin repair drugs by modulation of oligodendroglial differentiation competence. EBioMedicine 65, 103276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103276 (2021).

Nabizadeh, F. et al. Autoimmune encephalitis associated with COVID-19: A systematic review. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 62, 103795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2022.103795 (2022).

Naidu, K. & Tayler, R. Anti N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor antibody associated acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis in a patient with COVID-19: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 17, 247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-03979-x (2023).

Lee, H. et al. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis after coronavirus disease 2019: A case report and literature review. Medicine 101(35), e30464. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000030464 (2022).

Oladunni, F. S. et al. Lethality of SARS-CoV-2 infection in K18 human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 transgenic mice. Nat. Commun. 11, 6122. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19891-7 (2020).

Malinowska, B., Napiorkowska-Pawlak, D., Pawlak, R., Buczko, W. & Gothert, M. Ifenprodil influences changes in mouse behaviour related to acute and chronic ethanol administration. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 377, 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00393-3 (1999).

Poleszak, E. et al. Effects of ifenprodil on the antidepressant-like activity of NMDA ligands in the forced swim test in mice. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 46, 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.06.001 (2013).

Schidlitzki, A. et al. A combination of NMDA and AMPA receptor antagonists retards granule cell dispersion and epileptogenesis in a model of acquired epilepsy. Sci. Rep. 7, 12191. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12368-6 (2017).

Stazi, M. & Wirths, O. Chronic memantine treatment ameliorates behavioral deficits, neuron loss, and impaired neurogenesis in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 58, 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-020-02120-z (2021).

Martinez-Coria, H. et al. Memantine improves cognition and reduces Alzheimer’s-like neuropathology in transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 870–880. https://doi.org/10.2353/ajpath.2010.090452 (2010).

Li, P. et al. Memantine ameliorates cognitive deficit in AD mice via enhancement of entorhinal-CA1 projection. BMC Neurosci. 22, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12868-021-00647-y (2021).

Minkeviciene, R., Banerjee, P. & Tanila, H. Cognition-enhancing and anxiolytic effects of memantine. Neuropharmacology 54, 1079–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.02.014 (2008).

Hsu, J. Multiple Comparisons: Theory and Methods (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 1996). https://doi.org/10.1201/b15074.