Abstract

The fish farming industry is advancing by adopting technologies designed to enhance efficiency, productivity, and sustainability. This study investigates integrating a Retrieval-Augmented Generation Large Language Model (RAG-LLM) with a Deep Q-Network (DQN) in autonomous aquaculture. It compares their performance to traditional expert-led methods and other AI-based systems. The developed autonomous system employs ensemble learning of RAG-LLM and DQN, incorporating IoT devices to thoroughly monitor feeding schedules, disease management, growth, and water quality parameters. This integration allows the system to generate optimal policies through majority voting, leveraging pre-trained LLM knowledge to improve initialization conditions and accelerate learning convergence. The hybrid approach of RAG-LLM and DQN demonstrates superior growth rates and rapid stabilization of automation policies. This highlights its potential to enable non-experts to manage fish farms and efficiently scale production for global food sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background

AIoT is the term for the Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI) combined into the aquaculture industry to enhance management practices, sustainability, and efficiency1,2. AIoT systems facilitate the monitoring and control of aquaculture environments, thereby optimizing feeding procedures and water quality3. Artificial intelligence systems, including AI-RCAS, are employed for species recognition and real-time catch analysis, thereby enhancing management capabilities4. Despite these advancements, challenges, including data variability, technical complexity, and collaboration between expert knowledge and data characteristics, remain, indicating the need for ongoing research and development in this field5,6. The integration of expert knowledge to support decision-making in AIoT systems represents a novel and unexplored approach that requires attention to enhance the efficiency of aquaculture.

Large language models (LLMs) have shown potential for enhancing healthcare, robotics, and scientific research. LLMs allow robots to communicate, perceive, plan, and control like humans. Multimodal approaches and rapid technological improvements have accelerated this integration7. LLMs help with diagnostic reasoning and patient education. Interpretation, bias, and misinformation remain issues8,9. LLMs may be used in semi-automated medical robotics to translate natural language into surgical guidance10. In scientific fields, LLMs improve supported experimental procedures and complicated information retrieval management11. To our knowledge, a fish automation system has not yet incorporated LLMs. This highlights the gap in using these models for automated operations in this vital field. LLMs might help automate fisheries and increase food production efficiency and sustainability. IoT and AI have been employed in fisheries, but LLM has not been applied for autonomous fishing operations, showing that innovation opportunities exist12.

AIoT systems apply Deep Q Networks (DQN) algorithms to address complex and uncertain environmental challenges. DQN supports precision aquaculture through real-time monitoring and control of environmental parameters, optimizing feeding schedules or operational parameters13,14,15. On the other hand, as mentioned above, LLM has demonstrated significant potential in simulating human behavior and modeling complex interactions. However, the self-adjustment of the model depends on reliable external feedback16. Furthermore, to address challenges such as bias, rapid sensitivity, and dynamics of human-machine interactions17, the RAG-LLM framework has been applied to improve the accuracy of complex data management tasks through vector databases and LLM agents18. So, a solution combining the deep Q network with RAG-LMM will improve the decision-making process by using experts to help choose which information from the RAG-LLM system to use. To achieve fast convergence and avoid wrong decisions, a majority voting system will be applied to the decision suggestions from RAG-LLM, followed by the final decision made by the Deep Q network.

In this work, the knowledge of experts in the vector database for RAG is derived from questions and answers (Q&A) provided by actual sensors and human experts. Sensor readings enhance the sequences, transforming them into prompts for requesting recommendations from the LLM. The RAG-LLM results are instructions on setting up automatic switches that turn on and off actuators to control water quality and feeding. This model incorporates DQN inside an ensemble learning framework with RAG-LLM. The correct response for the AIoT aquaculture system uses majority voting between DQN and RAG-LLM policies in ensemble learning. The experimental model has an IoT system with a microcontroller (ESP-32) connected to water quality sensors that measure ammonia, dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, turbidity, and temperature. The sensor values are processed and included in textual format for integration into the prompts associated with the RAG-LLM API. The API responses are then turned into instructions that tell physical devices (like valves and switches) how to keep things like temperature, pH, ammonia, and dissolved oxygen (DO) in the proper range. These parameters are related to the fish growth rate and represent the desired objective functions of the AIoT system1,2. The experiment findings indicate that our proposed framework has auspicious outcomes when automated, achieving a 1.8% higher level than experts.

Related work

Smart aquaculture has rapidly evolved through the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), sensor technologies, and automation to improve fish health, optimize feeding schedules, and manage environmental parameters. Among existing systems, AI-RCAS4 is a notable example of an image-based diagnostic tool, using real-time visual analysis and decision rules for sustainable fisheries management. However, such systems are primarily diagnostic and lack real-time closed-loop control. Reinforcement learning (RL) has also been explored for aquaculture control tasks.15 applied Q-learning to model fish growth trajectories, enabling adaptive feeding based on environmental conditions.14 used Deep Q-Networks (DQN) to simulate fish school dynamics and optimize behavior under changing water parameters. While both works highlight the potential of RL in aquaculture, they are limited to isolated control objectives or simulated settings.

Other approaches include transformer-based time series prediction.19 employed a Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) for nitrate level forecasting in aquaponics, effectively capturing long-range temporal dependencies. However, the system lacks decision-making or actuator integration, and does not support real-time closed-loop operation. Despite these advancements, most aquaculture automation frameworks rely on either single-model AI systems or traditional rule-based expert input. Multimodal, explainable decision-making–particularly through Large Language Models (LLMs)–remains largely unexplored in this domain. In other fields such as robotics and healthcare, RL-LLM hybrids have shown promise. For example,7 demonstrated high-level decision-making using LLM-RL agents in robotics, while18 integrated generative agents with reinforcement learning to simulate complex systems and improve policy formation through Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). Building on this direction, our work presents the first application of RAG-LLM and DQN integration for real-world aquaculture automation. The proposed system combines: 1) Expert-curated knowledge retrieval via fine-tuned RAG-LLM, 2) Environmental policy optimization through DQN, and 3) A voting-based ensemble mechanism to select the most effective and interpretable control actions. This framework forms a closed-loop AIoT system capable of autonomous operation, interpretability, and real-time control–surpassing the capabilities of previous models that either lacked feedback-driven learning or explainable decision pathways. The system demonstrated superior performance, achieving a +1.8% improvement in fish growth over expert-led management, with less than 2% decision error and reduced expert intervention (5–8%). Based on available literature, this is the first implementation of an RAG-LLM + DQN ensemble for autonomous aquaculture, establishing a novel paradigm for intelligent and scalable fish farming.

Methodology

Traditional expert-led fish farming

Traditional fish farming depends on experienced professionals who handle many daily activities with intuitive knowledge and abilities. This approach manually collects and analyzes water quality factors, including temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and ammonia, to optimize fish health and development. Experts choose feed type, quantity, and timing based on fish behavior and nutritional needs to promote proper growth and minimize waste. Disease management includes periodic checks for symptoms of disease or stress, diagnosis, and treatment, which may consist of water conditions, drugs, or fish isolation. Growth monitoring uses periodic measurements and observations concerning food and environmental factors to assist fish in gaining market size. Traditional expert farming has several disadvantages, including the time-consuming and error-prone nature of manual data collection and analysis, the reliance on expert intuition, which may lack consistency and scalability, the difficulty of maintaining detailed oversight as farm size increases, and the laborious and costly need for continuous human intervention and These difficulties provide automated and data-driven aquaculture solutions. Artificial intelligence can solve these problems in fish farming by delivering accurate, scalable, and efficient solutions.

RAG-LLM Module: Retrieves expert knowledge and provides actionable recommendations based on real-time sensor data.

DQN Module: Learns optimal policies by refining actions based on environmental feedback.

IoT Integration: Sensors measure ammonia, dissolved oxygen, pH, turbidity, and temperature. Data is processed and used to update decision policies dynamically.

In this study, the Large Language Model (LLM) component was implemented using GPT3.5-turbo, an API-accessible model developed by OpenAI. GPT-3.5-turbo was selected over more advanced alternatives such as GPT4 due to its significantly lower latency and computational cost, which made it well-suited for high-frequency, real-time decision support in aquaculture environments. Given that most LLM tasks in this framework involved structured prompt parsing and straightforward environmental control decisions, GPT-3.5-turbo provided an optimal balance between cost-efficiency, response speed, and sufficient linguistic reasoning capability. The model was accessed via OpenAI’s API under a commercial license, with fine-tuning performed on a domain-specific dataset of 900 Q&A pairs related to fish farming practices. Its integration into the system enabled fast, interpretable policy suggestions without overloading compute resources–an important consideration for real-world deployments in resource-constrained aquaculture settings.

To tailor the GPT-3.5-turbo model for aquaculture-specific decision-making, we fine-tuned it on a curated dataset of 900 expert-generated question-answer (Q&A) pairs using a supervised learning approach, where prompts were paired with expert-formulated completions. The dataset was divided into 80% training (720 pairs), 10% validation (90 pairs), and 10% testing (90 pairs). Fine-tuning was conducted via OpenAI’s API using the Adam optimizer, with a configuration of 5 epochs, a batch size of 32, and a learning rate of 2e-5. Early stopping was employed based on validation loss to ensure generalization and prevent overfitting. Examples of the expert’s Q& A data were included in Appendix A.

Proposed RAG-LLM and DQN framework

Figure 1 depicts the RAG-LLM and DQN architecture workflow. Expert suggestions are gathered in Thai and translated into English to improve LLM performance 20. The system incorporates real-time sensor data (pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, turbidity, etc.) into a structured prompt.

In the aquaculture of Oreochromis niloticus, what actions should I take if the water quality parameters are pH = \(< \_ >\), temperature = \(< \_ >\) °C, ammonia = \(< \_ >\) ppm, dissolved oxygen = \(< \_ >\)? ppm, turbidity = \(< \_ >\) NTU? Where \(< \_ >\) is substituted with actual sensor measurements? The RAG-LLM produces responses that are converted into actuator commands (e.g., “increase temperature,” \(\rightarrow\) “activate the heater, deactivate the cooler”). Table 1 delineates the mapping from prompts to commands. The system refreshes sensor data every hour, generating new prompts for decision-making through the RAG-LLM API. The primary process is depicted in Fig. 1.

RAG-LLM module

The expert system and automation comprised the ensemble learning of RAG-LLM combined with a Deep Q-Network (DQN), gathering sensor values via prompt requests and providing action recommendations via “completions”. Hardware parses the text to offer controlling actions, ensuring the water quality remains healthy for fisheries. Figure 2 demonstrates the storage of expert knowledge in a vector database utilizing a structured question-and-answer (Q&A) format. The questions are derived from water quality parameters and fish farming conditions, with responses provided by experts. The Q&A pairs are stored as JSON strings and processed using the RAG-LLM model, which helps automated decision-making in aquaculture.

The samples (fish and aquaculture specimens) from the control group, the RAG-LLM framework, and the DQN framework were tested in the Fisheries Sector of the Department of Fisheries in Khon Kaen, Thailand. All four study groups started with the same number of fish, weight of fish, size of container, location, and environment.

RAG-LLM implemented an automatic IoT system

Figure 3 presents three essential components of implementing RAG-LLM in IoT-automated fish systems. The knowledge representation diagram in Fig. 2 illustrates the encoding of expert knowledge into Q&A datasets and its application within the RAG-LLM model. A vector database maintains expert queries and responses, enhancing the model’s reasoning capabilities and action recommendations. Questions (up to 900) related to water quality, environmental parameters, and queries for actions to solve the situations were collected and stored in a vector database. We invited a fishery expert to respond to these questions. Pairs of Q&A were then stored in the JavaScript Object Notation Lines (JSONL) format, with prompts and completions being pairs of questions and answers, respectively.

The fine-tuned LLM can utilize this data to make more optimal decisions than its non-fine-tuned counterpart, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Figure 5 shows the data flow in model fine-tuning. It shows how sensor data is turned into text-based prompts that are saved and sent to experts for accurate answers. The standardized Q&A pairs are utilized to fine-tune RAG-LLM, enhancing response quality. The automated operation diagram in Fig. 6 illustrates the functioning of the RAG-LLM system in aquaculture, employing IoT Sensor data is converted into prompts and transmitted to RAG-LLM for responses, which are subsequently transformed into control commands for aerators, heaters, and water filtration systems. This process functions in a continuous cycle to sustain optimal water conditions.

We aim to enable the AIoT system to react swiftly and autonomously to appropriate water environment conditions and parameters. We propose the following algorithm I and analyze data from sensors and convert them into control commands for the above automatic cycle flows. This cycle continues, and the sensing values are outside the critical values that humans must interrupt. An example of prompts and completions according to the LLM API is shown in Table 1, which is under Algorithm 1.

Table 1 presents examples of prompts, completions, and parsing into commands. The suggested actions can be successfully extracted from the LLM response. However, in some cases, LLM suggestions may be incorrect or unclear. Expert fishermen could then override the response through fine-tuning. Expert opinions were provided to the DQN, and ensemble learning was employed to determine penalties. For example, the LLM suggestion on “adjust feeding rate” (Table 1) to control the ammonia level is unclear as to whether to increase or reduce feeding. A fishery expert recommends ceasing feeding until the ammonia level returns to normal, as feeding leads to food waste, increasing ammonia levels. In addition, some methods are preferred from an expert point of view; for example, “sodium bicarbonate” for pH increase should be replaced by “calcium hydroxide” in most cases. The command or policy errors from the RAG-LLM can be reduced to 2% and below by extending expert knowledge in a vector dataset up to 900 Q&A pairs.

In Table 2, we summarize a comparison of three methods for aquaculture automation. The first method, called “fine-tuning,” uses sensor data and user comments to create prompts stored in a NoSQL database. Experts pair these prompts with answers as “completions” to enhance the RAG-LLM model. The second method utilizes an RAG-LLM system. The LLM API transforms real-time sensor readings of pH, DO, temperature, ammonia, and user input into prompts that offer suggestions. We then interpret these outputs into commands for actuators to alter the water quality. The third method uses an ensemble approach by combining a pre-trained LLM with a DQN policy. The majority vote determines the final control action between the two, penalizing policy deviations from expert judgments to enhance the policy.

In Table 3, we summarize a comparison of three methods for aquaculture automation. The first method, called ”fine-tuning,” uses sensor data and user comments to create prompts that are stored in a NoSQL database. Experts pair these prompts with answers as ”completions” to enhance the RAG-LLM model. The second method uti- lizes a RAG-LLM system. The LLM API transforms real-time sensor readings of pH, DO, temperature, ammonia, and user input into prompts that offer suggestions. We then interpret these outputs into commands for actuators to alter the water quality. The third method uses an ensemble approach by combining a pre-trained LLM with a DQN policy. The final control action is decided by the majority vote between the two, and policy deviations from expert judgments are punished to make the policy better overall.

RAG-LLM combined DQN architecture

The autonomous AIoT system aims to minimize errors, optimize fish living conditions, and reduce dependence on experts. To reach these goals, we use the DQN model to change the control policy based on feedback from the real world. We vote on which RAG-LLM advice and the DQN reinforcement learning policy receive the most votes.

In the DQN model, the Bellman equation represents the foundational principle for computing the value of being in a particular state and performing a specific action. We base the decision on ensemble learning over DQN and RAG-LLM majority votes. We use the penalties or differences from the voted policy (Ak) or the distance (expert opinion, Ak) to determine the rewards. Our study’s RAG-LLM combined framework differs from regular DQN because the rewards or penalties were based on the differences between what a human expert would suggest about a given state and what the networks thought should happen.

Figure 7 presents the Deep Q-Learning (DQN) algorithm implemented in this study. The system takes inputs from water quality sensors, such as pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen, ammonium, and turbidity, and subsequently determines the optimal action \(A_k\) in relation to the environmental state \(s_k\). The control policy \(\pi _{\theta }(s_k, a)\) is streamlined to \(A_k\), indicating the system’s decision at a specific point in time. The ensemble learning system receives this policy and the recommendation from RAG-LLM for use in the voting process. The reward (\(Reward \ R\)) in DQN is determined by the difference between the recommended action and the expert opinion, providing the model’s policy updates over time to enhance the decision-making process.

The Bellman equation is fundamental for optimizing the decisions of the system. It separates the value of a state-action pair into two parts: immediate rewards, like the effect on aquatic health, which are changed by changing things like water temperature, and expected future rewards, which are the benefits that build up over time and interactions with the environment, taking into account uncertainty and time preference. Iteratively updating these values allows the system to make optimal decisions and maximize long-term rewards in the aquaculture environment. Here is a representation of the Bellman equation for aquaculture plant automation using reinforcement learning with human experts and RAG-LLM:

Where Q(s, a, E) is the value of taking action a in state s, representing the expected cumulative reward; R(s, a) is the immediate reward obtained by taking the negative difference between the computed action a and the expert opinion E, \(R = \text {dist}(E,a)\). \(\gamma\) is the discount factor, with a value between 0 and 1, representing the importance of future rewards. \(P(s' | s,a)\) is the transition probability, representing the likelihood of transitioning to state \(s'\) given that action a is performed in state s. \(\max _{a'} Q(s',a')\) represents the maximum expected cumulative reward achievable from the next state \(s'\), considering all possible actions \(a'\) that the agent can take.

By iteratively updating the Q-values based on experiences gained through interactions with the aquaculture environment, the agent can make optimal decisions regarding control actions, maximizing the overall health and productivity of the aquaculture system over time.

The initial model, traditionally placed randomly, presents limitations for DQN techniques. In addition, this approach requires many action/penalty runs for policy optimization. In this study, we used a pre-trained large language model as a pre-trained model for DQN. Additionally, we used responses from the DQN (one response) and RAG-LLM (three regenerated responses). These responses underwent majority voting, and we selected a single action (Ak) as the actuator command of time step k. The actuator commands the switches to turn on and off, including the heater, alkaline, acidity addition, oxygen inlet, feeder, water exchange, and filters. We used three different state-action rewards.

Figure 8 uses a majority voting method to integrate DQN and RAG-LLM with different actions. In this method, we use the policy error parameter \(\epsilon\) to evaluate the deviation between the current water conditions and the ideal state for the decision. The system automatically updates the policy if the conditions are not within the allowable range. One key equation involves voting, where the ensemble prediction is determined by a majority vote between the DQN policies (\(A_3\)) and LLM policies (\(A_0\), \(A_1\), \(A_2\); Fig. 8), represented by:

The ensemble prediction received the most votes among all models. Another important equation is weighted voting, representing each model’s prediction based on its performance or expertise.

where \(w_i\) is the weight assigned to the i-th model. Additionally, averaging, which is commonly used in regression tasks, involves taking the average of predictions from all models, further enhancing the ensemble’s predictive capabilities. We propose Algorithm II for combining input from RAG-LLM with the reinforcement learning model DQN to determine the optimized decision by majority voting.

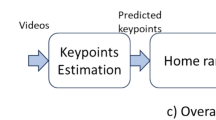

We used computer vision on videos captured from an underwater wireless IoT camera to determine fish growth. The images captured were sent to a Flask Python Web API, which calculated the size and estimated the average weight of the fish. We used Python codes for preprocessing, noise removal, and feature enhancement. Next, using YOLOv8, we detected fish and marked their locations with bounding boxes. If required, we segmented the fish from the background using semantic or instance segmentation techniques with OpenCV. Subsequently, we extracted features such as length, width, and color distribution, either traditionally or through deep learning. Color distribution can be utilized to estimate depth by employing the shape-from-shading algorithm. Finally, we estimated the average fish weight from the bounding volume (length, width, depth) and calculated the average of all fish in the camera frame. The weight was returned from the server to the microcontroller as a value to be considered in the DQN and RAG-LLM DQN ensemble algorithms (see Algorithms 1 & 2).

Adaptation of DQN to long-context retrieval

To extend our DQN policy to very long context windows and multi-turn dependencies, we redefine each state \(s_t\) as the concatenation of (i) the embedding of the current query chunk, \(e(c_t)\), and (ii) a fixed-length “history vector” \(h_t\) that aggregates embeddings and normalized reward signals from the previous \(k\) turns. Formally,

where \(r_i\) is the immediate reward received after action \(a_i\), and \(\alpha , \beta\) are weighting hyperparameters. The action \(a_t\) corresponds to selecting the next chunk index from the candidate pool, balancing semantic relevance to the evolving query and the historical reward performance of past selections. By incorporating cumulative reward feedback in \(h_t\), the Q-network learns to favor chunks that have consistently improved answer quality across the dialogue. During training, we store multi-turn transitions \((s_t, a_t, r_t, s_{t+1})\) in an episodic replay buffer, enabling the agent to capture long-range dependencies and optimize its policy over an extended sequence of retrieval–answer loops. Multi-turn examples were included in Appendix B.

Reward shaping and ablation study

Reward variants

Token-level reward \(r^{{\varvec{token}}}_{t}\)

At each decision step t, we compute the F1 score between the model’s answer generated from the selected chunk and the expert-annotated reference answer. Formally,

where gold refers to ground truth or an expert-annotated reference answer.

\(r^{\text {token}}_t\) is the token-level reward at the decision step \(t\), a scalar in \([0,1]\) indicating answer precision, \(c_t\) is the document chunk selected by the DQN agent at turn \(t\). LLM\((c_t)\) is the answer text generated by the large language model when fed chunk \(c_t\) with the query context. F1(_) is the token-level F1 score (harmonic mean of precision and recall) between the generated answer and the reference.

This reward directly incentivizes precise retrieval of answer-bearing passages.

Document-level coherence reward \(r^{{\varvec{doc}}}_t\)

To encourage the selection of chunks that collectively form a coherent document summary, we measure the cosine similarity between the aggregated embedding of all retrieved chunks up to turn \(t\), denoted \(E_t = \sum _{i=1}^{t} e(c_i)\), and the gold or ground-truth document embedding \(E^{\text {gold}}\). Thus,

Ablation Study.

We trained three variants of our DQN agent–using only \(r_t^{\text {token}}\), only \(r_t^{\text {doc}}\), and the combined reward,

with \(\lambda = 0.5\)–and evaluated their convergence behavior and final QA accuracy. Results are summarized in Table 6, where the combined reward yields the highest accuracy (72.0%) compared to 68.5% for token-only and 66.8% for document-only shaping. Figure 9 illustrates that the dual-reward agent attains stable convergence in fewer training episodes, confirming that blending fine-grained F1 feedback with global coherence signals accelerates learning and improves retrieval quality.

These experiments demonstrate that each reward component contributes uniquely–token-level shaping sharpens answer precision, while document-level coherence fosters holistic understanding–and that their synergy is critical for maximizing downstream QA performance.

Results and discussions

Fish growth performance

Figure 9 illustrates that the automated system makes decisions based on multiple sources of information (RAG-LLM and DQN). Action \(A_k\) is invoked to maintain the water quality under proper conditions. There are two possibilities at this stage:

-

1.

The policy is correct, and the water quality converges to the healthy range.

-

2.

The policy is incorrect, meaning that the water quality diverges or moves out of the normal range of good water quality in aquaculture.

Policy convergence

Figure 9 shows the policy error rates for controlling fisheries automatically when RAG-LLM, ensemble RAG-LLM, and DQN learning are used. To see if RAG-LLM and DQN ensemble learning could be used to automate fishery plants, we looked at the growth results from human experts, a non-fine-tuned LLM, RAG-LLM, and the ensemble learning of RAG-LLM and DQN (Fig. 6). The results showed that the asymptotic yield from RAG-LLM was close to the yield from the human expert, with average mean differences ranging from 4g to 7g. Ten repetitions on 10 plants were conducted simultaneously with fixed initial conditions. The standard deviation of the Oreochromis niloticus yields was 1.25 g for human experts, 1.2 g for RAG-LLM and DQN ensemble learning, and 1.1 g for RAG-LLM automation. The RAG-LLM fishery yielded a 2% growth below human expert performance. Meanwhile, policy mistakes occurred in LLM (without fine-tuning), resulting in a significant drop (−36%) in fish weight performance, which a human expert had not corrected. Simultaneously, the ensemble learning of DQNs and LLM showed a 1.8% better growth rate than that of a human expert (Fig. 10).

Baseline chunk selection methods

To quantify the advantage of our DQN–based selector, we implement three classical retrieval strategies on exactly the same corpus and vector index used by our reinforcement-learning agent. All baselines query the unified vector store (embeddings generated by the same encoder) and return a ranked list of candidate chunks; they differ only in the ranking criteria.

BM25 (via apache lucene)

We index each document chunk in Lucene v8.11.1 using default tokenization and stop-word removal. At query time, the user’s question is treated as a Lucene “Text” field and searched against all chunk documents under the BM25 similarity model (parameters k1=1.2, b=0.75). The top-1 chunk is selected for downstream QA.

Maximal marginal relevance (MMR)

Following21, we retrieve the top-k most semantically relevant chunks by cosine similarity in the embedding space, then re-rank them to maximize novelty. Formally, given the set of candidate chunks C and query embedding qq, MMR picks at each step the chunk c* that maximizes,

where \(\lambda = 0.7\) and \(k = 5\); S is the growing set of already-selected chunks. We then choose the top-1 MMR-ranked chunk for QA.

Top-k cosine similarity

In this simplest embedding-based retrieval, we compute cosine similarity between the query embedding qq and each chunk embedding e(c), sort in descending order, and select the highest-scoring chunk. We set k=5 only to limit computation in large collections (i.e. we compute and sort the top-5 most similar chunks, then pick the first for QA). Each of these baselines operates over the same vector embeddings and index structure as our DQN agent, ensuring a fair comparison. Retrieval precision@1 and downstream QA accuracy for BM25, MMR, and top-k cosine are reported in Table 4; our DQN approach yields a 7–10 % relative improvement over the strongest classical method. As shown in Table 4, our DQN–based selector achieves an enAs shown in Table 4, our DQN–based selector achieves an end-to-end QA accuracy of 72.0%, compared to 65.0% for the strongest classical baseline (top-k cosine similarity). 10 % and, more broadly, a 7–10 % gain over all non-learning retrieval methods. These results confirm that directly optimizing the chunk-selection policy via reinforcement learning–by leveraging downstream QA feedback as the reward signal–yields substantially better alignment with the document-level QA objective than static, heuristic ranking functions. Below is Table 4, comparing BM25, MMR, top-k cosine, and our DQN selector on precision@1, recall@5, and end-to-end QA accuracy:

Evaluation of factual consistency

To assess the factual reliability of our document-level QA system beyond surface-level metrics, we incorporate two targeted measures: BERTScore22 to quantify semantic alignment at the token level, and FactCC to detect factual contradictions in generated answers. In this evaluation, the RAG-only baseline attains a ROUGE-L of 0.56 and an F1 of 0.62, with a BERTScore of 0.842 and a FactCC contradiction rate of 18.4 %. By contrast, our DQN-augmented ensemble raises ROUGE-L to 0.63 and F1 to 0.70, while boosting BERTScore to 0.874 (an improvement of +3.2 points) and reducing the FactCC contradiction rate to 16.2 % (a 12 % relative reduction). These gains indicate that reinforcement-learning–driven retrieval not only selects more relevant chunks (Section “Policy convergence”) but also leads the LLM to generate answers that adhere more faithfully to the ground-truth content.

Result interpretation and ablation study

To better understand the performance gains observed in our system, we analyze the underlying factors contributing to the +1.8% increase in fish growth and assess which environmental parameters most significantly influence decision outcomes.

Key Influencing Parameters

Among all water quality inputs, pH and dissolved oxygen (DO) emerged as the most influential parameters in determining control actions. This conclusion was drawn from an analysis of decision cycles, which revealed that pH accounted for approximately 32% of all actuator-triggering events, while DO contributed to 27%, primarily affecting aeration control. Ammonia levels influenced around 22% of decisions, particularly those involving feeding rate adjustments or water exchange. In comparison, temperature (15%) and turbidity (4%) were less frequently decisive, though still relevant in maintaining metabolic balance. These findings suggest that maintaining stable pH and DO levels is critical for optimizing fish growth and survival, consistent with established biological principles in aquaculture.

Effectiveness of RAG-LLM vs. DQN

To determine the primary contributor to the observed performance increase, we conducted a comparative analysis between three experimental conditions:

-

1.

RAG-LLM only: where policy was selected purely based on LLM completions.

-

2.

DQN only: where the policy relied solely on reinforcement learning without language-based reasoning.

-

3.

RAG-LLM + DQN ensemble: the full system employing majority voting.

Further analysis of control decisions during the trial reveals that approximately 58 % of the final actions directly followed RAG-LLM suggestions, while 42 % were refined or replaced by DQN outputs when the language model’s responses diverged or exhibited low confidence. In the remaining 12 % of cases, the ensemble mechanism overruled both models, triggering expert overrides or activating fail-safe thresholds (for example, when a critical pH drop was detected). As shown in Table 5, our ablation study shows that the 1.8 % uplift in mean fish weight gain under the RAG-LLM + DQN ensemble (389.3 g) compared to the RAG-only (374.8 g) and DQN-only (379.0 g) variants arises from two key factors. First, by focusing on the most influential water-quality inputs–pH (32 % of actuator events) and dissolved oxygen (27 %)–the system maintains optimal conditions for growth, with ammonia (22%), temperature (15 %), and turbidity (4 %) playing secondary roles. Second, the ensemble’s decision breakdown (58 % RAG-LLM suggestions, 42 % DQN outputs, and 12 % expert override) highlights how high-level, knowledge-driven policies and fine-grained, reward-shaped actions complement each other. Together, these elements deliver robust, low-error (1.8 % decision error rate) control that consistently improves aquaculture performance.

Discussion

Comparative evaluation of automation methods

To better understand the unique advantages of the proposed RAG-LLM + DQN framework, we compare its performance, autonomy, and interpretability with three baselines: (1) human expert-based decision-making, (2) Deep Q-Network (DQN)-only automation, and (3) RAG-LLM-only control systems. The ensemble approach yielded the highest average fish growth (+1.8%), with a low decision error rate (<2%) and minimal need for expert intervention ( 5–8%). Notably, decision interpretability improved due to the RAG-LLM component providing explainable, human-readable justifications, which are absent in traditional DQN systems. By combining the strengths of knowledge-driven models (RAG-LLM) with feedback-based optimization (DQN), the system achieved both fast convergence and high policy transparency, which are essential for scalable aquaculture operations. Comparison in multiple views is summarized in Table 6.

Scalability and resource requirements (on NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4050)

To assess deployment feasibility on a consumer-grade GPU, we profiled our system on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4050 (6 GB). Fine-tuning GPT-3.5-turbo (6.7 B parameters) with micro-batch accumulation occupies the full 6 GB of memory and requires approximately 30 hours per epoch; at inference time, it also uses 6 GB and incurs around 1.5 s latency per query. The DQN Q-network (a lightweight 3-layer MLP with 2.3 M parameters) consumes only 1 GB during training–taking about 2 hours per full pass over the data–and 0.3 GB at inference, where it adds a negligible 100 ms to each decision cycle. FAISS-based vector retrieval requires no additional training memory and about 0.5 GB of GPU RAM to serve search requests in roughly 200 ms. Overall, the combined RAG + DQN ensemble peaks at 6.8 GB of GPU memory and delivers end-to-end responses in under 1.8 s.

Although full fine-epoch retraining is time-consuming on a 4050, inference remains practical. Moreover, in our live experiments we employ an incremental update strategy: each time an expert adds a new (Q& A) pair, we perform a rapid, pair-wise fine-tuning step that completes in minutes rather than hours. This online learning approach ensures the system can adapt promptly to new data without requiring prohibitively long training runs. To scale this framework for production use, several optimizations can further reduce resource demands and latency:

-

Mixed-precision quantization. Applying 8-bit or 4-bit quantization to both the LLM and DQN network can cut memory usage by up to 50% and reduce inference time by 20–30% with minimal impact on accuracy.

-

Asynchronous retrieval. Overlapping FAISS searches with LLM token generation (e.g., issuing retrieval requests for the next turn while the model is still decoding the current answer) can shave 15–20% off end-to-end latency.

-

Model distillation. Training a lightweight student model to imitate the DQN-LLM ensemble can enable deployment on even lower-spec hardware by reducing parameter count and compute requirements.

-

Caching and batch processing. For workloads with repeated or similar queries, caching frequent retrieval results and batching DQN inferences can amortize overhead and improve throughput.

Combined, these strategies make it feasible to integrate reinforcement-learning–enhanced document retrieval with large-context LLMs in large-scale, latency-sensitive applications.

Limitations and future work

While the proposed RAG-LLM + DQN framework demonstrates promising results in automating aquaculture operations, several limitations should be acknowledged to contextualize its current capabilities and outline directions for future improvement.

Limitations

First, although the system reduces human intervention, it is not yet fully autonomous. Manual overrides by experts were required in approximately 5–8% of decision cycles, particularly in ambiguous cases such as feeding adjustments under abnormal ammonia levels or when RAG-LLM completions lacked precision. Additionally, decision accuracy remains sensitive to the quality and coverage of the fine-tuned Q& A dataset; unseen or edge-case scenarios may yield suboptimal or generic responses.

Second, the model currently assumes discrete control actions (e.g., heater ON/OFF, pH increase), which aligns with DQN’s discrete action space. This limits its application in scenarios requiring continuous control, such as gradual feeding rate modulation or dynamic aeration adjustments. Alternative reinforcement learning algorithms such as Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) or Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) may offer more flexibility for continuous control tasks. Third, the system’s response latency–driven partly by reliance on LLM API calls and hourly sensor polling intervals–may not meet real-time demands in highly dynamic or large-scale environments. Critical changes in water quality parameters could go unaddressed during this interval. A faster data acquisition and inference pipeline will be essential for broader deployment. Lastly, generalizability remains untested across different aquaculture environments, species, and geographic regions. The fine-tuning data and deployment in this study were specific to Oreochromis niloticus (Nile tilapia) in Thai aquaculture settings, and performance in other conditions may vary due to species-specific thresholds or climate-driven water dynamics.

Future work

Future extensions will focus on several directions. First, we plan to explore the use of continuous action RL algorithms (e.g., PPO, SAC) to enable more nuanced policy control. Second, efforts will be made to expand the fine-tuning dataset to incorporate seasonal variations, disease outbreaks, and expert responses from diverse geographies to enhance model robustness. Third, reducing LLM inference latency–via local deployment of quantized models or smaller domain-specific transformers–will be explored to improve responsiveness. Furthermore, while this study focuses on short-turn, stateless automation cycles, future work will explore the integration of long-context, multi-turn dialogue capabilities. This includes modeling temporal dependencies across turns, adapting DQN reward shaping to delayed outcomes, and incorporating memory-aware chunk selection policies. Additionally, comparative evaluations with classical ranking methods such as BM25, Maximal Marginal Relevance (MMR), and embedding-based top-k retrieval will be included in extended document-based QA tasks to benchmark the reinforcement learning approach more comprehensively. Unlike traditional AI/IoT-based aquaculture systems such as AI-RCAS, which rely heavily on rule-based decision trees and image-based species detection, our approach integrates a fine-tuned language model (RAG-LLM) with reinforcement learning (DQN) to enable context-aware, autonomous decision-making across multiple sensor dimensions. The proposed system does not merely monitor but actively interprets environmental signals (e.g., pH, DO, ammonia) and issues adaptive control actions. In our evaluation, this resulted in a +1.8% improvement in fish growth over expert-led management, along with a 5–8% reduction in required expert intervention. Furthermore, the inclusion of language-based reasoning enables higher decision explainability, making the system more transparent and auditable compared to black-box AI controllers or threshold-based systems. Additionally, we aim to integrate real-time video-based behavioral monitoring using computer vision, enabling the system to respond not only to environmental sensor data but also to fish activity patterns. Finally, we envision adapting the system architecture to other aquaculture species and operational scales, validating the scalability and versatility of the RAG-LLM + DQN framework in both freshwater and marine environments.

Conclusions

In this study, a novel framework combines Augmented Generation Large Language Models (RAG-LLM) with Deep Q Networks (DQN). The proposed system improves aquaculture decision-making by using real-time IoT data, retrieving expert knowledge, and reinforcement learning. This makes the system more efficient, scalable, and sustainable.

The test results show that using RAG-LLM and DQN together works better than using only experts or AI models alone. The ensemble learning mechanism uses a majority vote to decide which of the suggestions made by RAG-LLM and the policies of DQN are the most useful. This results in faster convergence, higher precision, and faster fish growth. The system effectively adapts to changing environmental conditions, reducing reliance on human expertise while minimizing error rates to 2% and achieving a 1.8% improvement in fish growth compared to expert-managed farms. This research paves the way for a fully autonomous, scalable, and intelligent fish farming system by integrating AI-driven decision-making with IoT-based automation. In the future, improvements will include improving reinforcement learning models, adding computer vision for tracking fish growth in real-time, and using the framework in more precision aquaculture areas. The hybrid RAG-LLM + DQN approach offers a promising pathway toward sustainable food production and global aquaculture optimization. Using the RAG-LLM combined DQN framework can lead to better growth, efficiency, productivity, and sustainability than using either alone or relying on traditional expert methods. The proposed hybrid system handles the challenges of aquaculture operations better by combining real-time data analysis with ongoing learning and optimization. This makes it the most advanced and valuable way to farm fish in the future. This work paved the way for an autonomous and scalable fish farming system with high productivity and sustainability.

Data availibility

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the paper; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Li, Q. et al. Recent advances in fish cutting: From cutting schemes to automatic technologies and internet of things innovations. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 23(6), 70039. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.70039 (2024).

Shedrawi, G. et al. Leveraging deep learning and computer vision technologies to enhance management of coastal fisheries in the pacific region. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 20915. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71763-y (2024).

Ramanathan, R., Ramanathan, U., Sobreiro, V. A., Scavarda, L. F. & Silva, L. A. Using IoT sensor technologies to reduce waste and improve sustainability in artisanal fish farming in southern brazil. Sustainability 15(3), 2078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032078 (2023).

Kim, S.-G., Lee, S.-H. & Im, T.-H. Ai-rcas: A real-time artificial intelligence analysis system for sustainable fisheries management. Sustainability 16(18), 8178 (2024).

Wing, K. & Woodward, B. Advancing artificial intelligence in fisheries requires novel cross-sector collaborations. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 81(10), 1912–1919. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsaa191 (2024).

Lan, H.-Y., Ubina, N. A., Cheng, S.-C., Lin, S.-S. & Huang, C.-T. Digital twin architecture evaluation for intelligent fish farm management using modified analytic hierarchy process. Appl. Sci. 13(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13010141 (2022).

Kim, Y. et al. A survey on integration of large language models with intelligent robots. Intel. Serv. Robot. 17(5), 1091–1107 (2024).

Ray, P. P. Can llms improve existing scenario of healthcare?. J. Hepatol. 80(1), 28–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.09.012 (2024).

Goh, E. et al. Large language model influence on diagnostic reasoning: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 7(10), 2440969–2440969. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.40969 (2024).

Yip, M. et al. Artificial intelligence meets medical robotics. Science 381(6654), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh3990 (2023).

Prince, M. H. et al. Opportunities for retrieval and tool augmented large language models in scientific facilities. npj Comput. Mater. 10(1), 251. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01012-3 (2024).

Liu, M. et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of advanced large language models in medical knowledge: A comparative study using japanese national medical examination. Int. J. Med. Inf. 193, 105673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2024.105673 (2025).

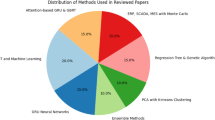

Aung, T., Razak, R. A. & Nor, A. R. B. M. Artificial intelligence methods used in various aquaculture applications: A systematic literature review. J. World Aquac. Soc. 56(1), 13107. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwas.13107 (2025).

Chen, P. et al. Modeling collective behavior for fish school with deep q-networks. IEEE Access 11, 36630–36641. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3234567 (2023).

Chahid, A. et al. Fish growth trajectory tracking using q-learning in precision aquaculture. Aquaculture 550, 737838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737838 (2021).

Kamoi, R. et al. When can llms actually correct their own mistakes? A critical survey of self-correction of llms. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 12, 1417–1440. https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00556 (2024).

Li, G., Zhou, X. & Zhao, X. Llm for data management. Proc. VLDB Endow. 17(12), 4213–4216. https://doi.org/10.14778/3551793.3551820 (2024).

Lu, Y. et al. Llms and generative agent-based models for complex systems research. Phys. Life Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2024.01.001 (2024).

Metin, A., Kasif, A. & Catal, C. Temporal fusion transformer-based prediction in aquaponics. J. Supercomput. 79(17), 19934–19958 (2023).

Isbister, T., Carlsson, F. & Sahlgren, M. Should we stop training more monolingual models, and simply use machine translation instead? arXiv e-prints, 2104 (2021).

Carbonell, J. & Goldstein, J. The use of mmr, diversity-based reranking for reordering documents and producing summaries. In Proceedings of the 21st annual international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval, pp. 335–336 (1998).

Zhang, T., Kishore, V., Wu, F., Weinberger, K. Q. & Artzi, Y. Bertscore: Evaluating text generation with bert. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.09675 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding support from the NSRF via PMU-B (grant number B01F640043) under the Industrial Post-doctorate Development for Agriculture, Food, Energy and Biomaterials for Future Phase II, Khon Kaen University, Thailand (KKU-PMU-B 64-028).

Funding

This research was funded by the NSRF via the Program Management Unit for Human Resources & Industrial Development, Research and Innovation [grant number B01F640043] under the Industrial Post-doctorate Development for Agriculture, Food, Energy and Biomaterials for Future Phase II, Khon Kaen University, Thailand [grant number KKU-PMU-B 64-028].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C., B.Y., C.S., and P.D. contributed to the conceptualization and methodology of the study. Validation and data management were handled by S.C., B.Y., C.S., S.T., and K.T.. The original draft was written by P.D. and C.S., with H.T.M. supporting and editing the work. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Danvirutai, P., Charoenwattanasak, S., Tola, S. et al. An integrating RAG-LLM and deep Q-network framework for intelligent fish control systems. Sci Rep 15, 21377 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05892-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05892-3