Abstract

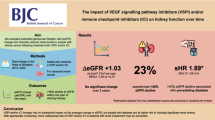

Objectives We investigate the renal safety of long-term non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) exposure in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS). Methods We analyzed electronic medical records from Asan Medical Center (AMC) and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (SNUBH), including 1,618 and 995 AS patients, respectively, with over one year of follow-up and no pre-existing kidney disease (baseline eGFR ≥ 60). NSAID exposure was quantified using the medication possession rate (MPR), and its impact on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) changes was assessed using linear mixed-effects models. Two approaches were employed: a 1-year interval analysis assuming a stable effect over time without time interaction, and a 3-year interval analysis incorporating time interaction to evaluate cumulative NSAID effects and changes in the relationship with eGFR decline over time. Results In the analysis without time interaction, NSAID use was associated with a decline in annual eGFR, with patients having 100% NSAID use experiencing a decrease in eGFR (β, -0.7; 95% CI: -1.1 to -0.3) compared to those with no NSAID use. A meta-analysis showed that every 1% increase in NSAID MPR associate with eGFR decline (β, -0.007; 95% CI: -0.011 to -0.004). However, the time-interaction analysis found no significant cumulative eGFR decline across most time points, except at the 9-year follow-up in SNUBH (β, -5.1; 95% CI, -9.2 to -1.1) and 18-year follow-up in AMC (β, -8.9; 95% CI, -15.9 to -1.9). Conclusion This study demonstrates that while NSAID use may affect renal function in the short term, its long-term cumulative effects on renal impairment appear non-significant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS), which occurs in relatively young men, is a chronic inflammatory disease primarily affecting the spine and sacroiliac joints, leading to progressive stiffness and pain1. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are crucial in the management of AS and are widely recognized for their ability to significantly alleviate symptoms and enhance the quality of life of patients2,3,4. Continuous NSAID therapy is often recommended for patients with active, symptomatic disease, as it not only relieves pain, but may also slow the progression of spinal bony changes associated with AS5,6,7.

However, prolonged NSAID use raises critical concerns about renal safety8,9,10. It has been reported that approximately 1–5% of NSAID users develop acute renal complications and chronic renal diseases driven by mechanisms such as vasoconstriction, tubular necrosis, and acute interstitial nephritis11,12,13,14. Although the association between NSAID use and renal disease is well-documented, the progression of renal function deterioration under long-term NSAID therapy remains controversial. Several studies have associated long-term NSAID use to kidney function deterioration, with a systematic review showing that higher NSAID doses increase the risk of accelerated chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression compared to lower doses15,16. Conversely, a recent study involving 1,280 patients with AS using long-term NSAIDs found no significant association between NSAID use and kidney function17, similar to findings from a prospective cohort study in rheumatoid arthritis patients over 3.2 years, showing no adverse impact on renal function18.

Given the potential for renal deterioration over an extended period, long-term studies that carefully account for potential bias are needed. To address these gaps, our study aims to investigate the renal safety of long-term NSAID exposure in patients with AS, utilizing an Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership common data model (OMOP CDM) with extended follow-up at two tertiary centers.

Materials and methods

Study population

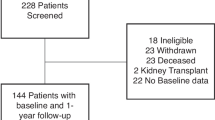

We used observational health data transformed into CDMs from Asan Medical Center (AMC) and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (SNUBH). The CDM of each hospital consists of de-identified patient-level electronic health record data that are routinely collected during medical services. We used CDM data for patients with AS with an observation period of more than one year who were treated at AMC and SNUBH from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2020. We excluded patients with CKD, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) lower than 60 at baseline, known kidney disease, and malignancy. The need for informed consent was waived by the institutional review boards (Asan Medical Center: No. 2021 − 1147; Seoul National University Bundang Hospital: X-2208-776-901) as the study used retrospective, de-identified data. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data collection

The baseline measurements collected for analysis included C-reactive protein (CRP), serum creatinine, and eGFR, which were estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) and Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formulas. Patients were stratified into two stages according to the initial eGFR: Stage 1 (eGFR ≥ 90) and Stage 2 (60 ≤ eGFR < 90). We collected clinical information on age, sex, and body mass index (BMI). The presence of comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, vascular diseases, chronic lung diseases, and inflammatory bowel disease, was also recorded. Based on the diagnostic codes, this study defined AS, kidney disease, malignancy, and other comorbidities (Supplemental Table 1).

We evaluated the use of medications, particularly focusing on NSAIDs (Supplemental Table 2). NSAIDs were categorized into selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors (celecoxib, etoricoxib, and rofecoxib) and non-selective (aceclofenac, diclofenac, ibuprofen, indomethacin, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, nimesulide, and piroxicam). The daily dose of NSAIDs was standardized using the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS)-NSAID equivalent, wherein diclofenac 150 mg is equivalent to indomethacin 150 mg, resulting in a reference dose ratio of 119. We used the medication possession ratio (MPR), defined as the total number of days of supply for all filled prescriptions during the assessment period divided by the number of days in that period, and then multiplied by 100% to assess medication adherence20. An MPR of 100% or 1:1 ratio indicates ideal adherence, in which the patient consistently refills their medication on time. However, this ratio can be skewed if patients refill their prescriptions earlier than necessary, resulting in an MPR exceeding 100%. We capped the MPR at 100% to prevent artificially inflated adherence rates. Patients were categorized into three groups based on their NSAID MPR: low (0–33%), intermediate (34–66%), and high (67–100%).

Other medications considered in the study included TNF inhibitors (etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab, infliximab, and biosimilars), glucocorticoids (prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and deflazacort), conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide, torsemide, furosemide, spironolactone, and amiloride).

Statistical analysis

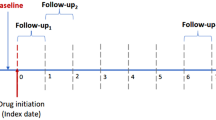

In this study, we evaluated the impact of NSAID exposure on eGFR changes over time using two distinct methods, each with different mixed-effect models for measuring exposure and outcome variables.

The eGFR values for each 1-year interval were imputed using the linear interpolation method, utilizing the measured values before and after each point. NSAID use in each interval was estimated as the MPR. Linear mixed-effects models were employed and adjusted for key covariates, including age, sex, baseline eGFR, comorbidities, and comedications, to evaluate the association between NSAID use and annual changes in eGFR.

The first analysis, using 1-year interval data, focused on the annual change in eGFR as the main outcome variable, with the annual NSAID MPR as the primary exposure variable. This analysis reflects the relationship between NSAID use and GFR change across the entire observation period, assuming the effect is consistent at any given follow-up point. We analyzed the annual change in eGFR by NSAID exposure using a mixed effects model with a random intercept for each 1-year interval. In the multivariable model, continuous variables, such as baseline eGFR, age, MPR, and average CRP level, were centered by subtracting their mean values. Centering these variables allows the intercept to represent the natural change in eGFR over one year for a patient with average values of these continuous variables and zero for binary variables. This approach enables a more precise interpretation of the baseline change in eGFR for a patient with average characteristics within the study population, providing a clearer understanding of the impact of NSAID exposure on eGFR changes. Each multivariable model included covariates such as centered baseline age, sex, centered average CRP level, comorbidities, and comedications. Additionally, model 1 included centered NSAID MPR; model 2 included centered COX-2 inhibitor MPR and centered non-selective COX-2 inhibitor MPR; and model 3 included the MPR group.

The second analysis, using 3-year interval data, examined the relative change (%) in eGFR from baseline at various time points, calculated as the change in eGFR divided by the baseline eGFR. Cumulative NSAID exposure from baseline was considered the main exposure variable. Unlike the short-term analysis, which evaluates interval-specific effects, the time-interaction analysis focuses on cumulative effects observed at long-term follow-up points. This approach examines whether the relationship between NSAID use and eGFR decline changes over time. Model 1 included cumulative NSAID MPR; model 2 included cumulative NSAID MPR group and covariates, such as baseline CKD stage, age, sex, average CRP, comorbidities, and comedications.

Finally, a meta-analysis was performed to synthesize the effects of NSAID exposure on eGFR changes across the two institutions involved in the study. We employed a random-effects model for the meta-analysis to account for the potential heterogeneity between study populations at different institutions. We estimated that the effects being estimated in the studies are not identical but follow a distribution, which is particularly relevant in multicenter studies where patient populations and treatment protocols may vary slightly.

Continuous values are presented as means with standard deviations (SDs) or as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). Missing values were imputed using single imputation via the mice package in R, employing predictive mean matching with 10 iterations. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

A total of 1,618 and 995 patients with AS were collected from the AMC and SNUBH, respectively, as shown in Table 1. The mean age of patients was 37.5 years (SD, 13.4) at AMC and 41.4 years (SD, 14.5) at SNUBH, with a similar male predominance in both cohorts (73% at AMC and 71% at SNUBH). The median follow-up duration was 72 months (IQR, 36.0–120.0) in the AMC cohort, compared to 48 months (IQR, 24.0–72.0) at SNUBH.

The extent of missing data on BMI and CRP levels among clinical measurements varied between the two institutions. At AMC, 10.6% of BMI data and 5.2% of CRP data were missing, whereas at SNUBH, the proportion of missing data was higher at 44.7% for BMI and 14% for CRP. The mean CRP levels were 1.7 (SD, 2.5) mg/dL at AMC and 1.9 (SD, 2.9) mg/dL at SNUBH, while the median BMI value was 24.0 (SD, 3.6) at both institutions. The imputed values for CRP levels and BMI are presented in Table 1. Among comorbidities, hypertension was most prevalent at AMC (5.0%), and dyslipidemia was most prevalent at SNUBH (4.1%).

The baseline renal function, as assessed by the CKD-EPI equation, showed that the median eGFR was comparable between the two cohorts, with values of 113.7 mL/min/1.73 m² (IQR, 103.7–122.7) at AMC and 110.7 mL/min/1.73 m² (IQR, 100.7–120.0) at SNUBH. Similarly, when using the MDRD equation, the median eGFR values were 102.4 mL/min/1.73 m² (IQR, 90.3–116.4) at AMC and 101.6 mL/min/1.73 m² (IQR, 88.6–118.0) at SNUBH. Most patients were classified as Stage 1 (eGFR ≥ 90) according to the CKD-EPI equation, with 1,501 patients (92.8%) at AMC and 900 patients (90.5%) at SNUBH.

Regarding medications other than NSAIDs at baseline, the use of DMARDs and glucocorticoids varied between institutions, with sulfasalazine being more commonly used at AMC (15.0%) than at SNUBH (8.5%). The mean NSAID dose ratio (DR) was 0.9 (SD, 0.2) at both institutions. Most patients were classified within the low MPR group (0–33%), with 90.5% at AMC and 93.9% at SNUBH at baseline. Regarding COX-2 selectivity, the MPR for COX-2 inhibitors was 0.0 (IQR, 0.0–0.0) at both institutions.

Annual eGFR change by NSAID exposure

The mean annual change in eGFR, based on the CKD-EPI and MDRD equations, is presented in Table 2 for the multivariable analysis and Supplemental Table 3 for the univariate analysis. In the short-term analysis assumed a consistent effect of NSAID use on GFR change across all follow-up periods, NSAID use was significantly associated with an additional decrease in GFR (model 1, 100% vs. 0% of centered MPR, β= −0.7, 95% CI: −1.1 to −0.3; model 3, MPR high group [67–100%] vs. low group [0–33%], β= −0.507, 95% CI: −0.884 to −0.130). However, this decrease was smaller than the natural change indicated by the intercept (model 1: β = −0.974, 95% CI: −1.195 to −0.753; model 3: β = −0.793, 95% CI: −1.029 to −0.557). Regarding COX-2 selectivity, both selective and non-selective COX-2 inhibitors were significantly associated with eGFR decline (model 2: selective COX-2 inhibitor centered MPR, β= −0.009, 95% CI: −0.016 to −0.002; non-selective COX-2 inhibitor centered MPR, β= −0.006, 95% CI: −0.011 to −0.002).

This tendency was also observed in SNUBH, with similar trends noted in the relationship between NSAID exposure and eGFR decline, consistently replicated across both the CKD-EPI and MDRD equations (model 1, 100% vs. 0% of centered MPR, β= −0.8, 95% CI: −1.3 to −0.2; model 3, MPR high group [67–100%] vs. low group [0–33%], β= −0.625, 95% CI: −1.110 to −0.140). However, in contrast to AMC, these changes were larger than the natural change indicated by the intercept (model 1, β= −0.723, 95% CI: −1.064 to −0.381; model 3, β= −0.433, 95% CI: −0.814 to −0.053).

The meta-analysis evaluated the annual change in eGFR and its association with NSAID exposure across two institutions, AMC and SNUBH (Fig. 1). The findings demonstrated a significant association between NSAID use and a reduction in eGFR (100% vs. 0% of MPR, β= −0.7, 95% CI: −1.1 to −0.4), although this reduction was smaller than the intercept (β = −0.883, 95% CI: −1.119 to −0.648). This effect was consistently observed across both institutions, with minimal heterogeneity. In particular, both selective and non-selective COX-2 inhibitors were found to have a significant association with the decline in eGFR, with selective COX-2 inhibitors showing a particularly strong impact (100% vs. 0% of selective COX-2 inhibitor centered MPR, β= −0.7, 95% CI: −1.2 to −0.2, 100% vs. 0% of non-selective COX-2 inhibitor centered MPR, β= −0.8, 95% CI: −1.1 to −0.4). Additionally, when analyzed by the MPR group, the high-exposure group showed a more pronounced decline in eGFR compared to the intermediate and low groups (MPR high group [67–100%] vs. low group [0–33%], β= −0.551, 95% CI: −0.849 to −0.254).

Estimated GFR change from baseline by cumulative NSAIDs exposure

Next, we performed the time-interaction analysis examines how the relationship between cumulative NSAID use and cumulative eGFR change evolves over time at specific follow-up points (Table 3).

Across different time points and cumulative exposure levels, the results showed variability in the association between NSAID exposure and eGFR changes. However, a significant overall relationship was found between cumulative NSAID exposure and the eGFR change when considering the entire study period. Notably, significant associations were observed only at the 9-year follow-up in the SNUBH and the 18-year follow-up in the AMC cohort, where higher NSAID exposure was associated with a significant decline in eGFR (9-year in the SNUBH, 100% vs. 0% of MPR, β= −5.1, 95% CI: −9.2 to −1.1; 18-year in the AMC, 100% vs. 0% of MPR, β= −8.9, 95% CI: −15.9 to −1.9).

When conducting an analysis by NSAID MPR groups, significant associations were observed at the 18-year follow-up in the high MPR group in the AMC cohort (MPR high group [67–100%] vs. low group [0–33%], β= −9.618, 95% CI: −15.298 to −3.938). In contrast, no significant association was found for the intermediate MPR group during the 18-year follow-up (MPR intermediate group [34–66%] vs. low group [0–33%], β= −0.738, 95% CI: −4.223 to 2.747) (Table 4).

The second meta-analysis focused on the longitudinal effects of cumulative NSAID exposure on eGFR changes from baseline over various follow-up intervals (Fig. 2). This analysis revealed that the relationship between cumulative NSAID exposure and eGFR changes was not uniform over time. Instead, the impact of NSAID exposure on kidney function varied across different time points, with some intervals showing significant declines in eGFR, while others did not.

Discussion

This study offers important insights into the long-term effects of NSAID use on renal function in patients with AS. Our analysis, which utilized two distinct methodological approaches, revealed significant associations between NSAID exposure and changes in eGFR over time, particularly highlighting the potential renal risks associated with prolonged NSAID therapy.

The first approach, which assessed annual eGFR changes relative to yearly NSAID exposure, demonstrated a clear correlation between high NSAID usage and a reduction in eGFR within a 1-year interval. The findings from this assessment suggest that even short periods during which patients fall into the higher NSAID exposure group can significantly impact kidney function compared to its natural progression. This finding underscores the importance of careful monitoring when initiating or continuing NSAID therapy in patients with AS. However, when evaluating the impact of cumulative NSAID exposure over time, the relationship with a sustained decline in renal function was less consistent. Although some intervals showed significant declines in eGFR, these were not uniformly observed across the entire cohort. The inconsistent association between cumulative NSAID exposure and long-term renal function decline can be interpreted in several ways. Notably, our findings are consistent with those of a prospective cohort study involving patients with rheumatoid arthritis, which reported no significant long-term decline in renal function despite chronic NSAID use18. It is plausible that patients who begin to experience renal function decline may reduce or discontinue NSAID use, thereby limiting their cumulative exposure and preventing further damage. Conversely, patients with stable renal function may continue using NSAIDs over longer periods, potentially skewing the results toward a less pronounced long-term impact. Additionally, the reduced number of patients available for long-term follow-up may have underpowered the study, making it difficult to detect significant long-term associations. However, as reported in several studies, this result may indicate the potential long-term safety of NSAIDs17,18. Our study may offer insights into the inconsistencies observed in previous research, as earlier studies often employed heterogeneous designs in terms of outcomes, exclusion criteria, populations, follow-up durations, and racial differences. These factors suggest that the results and interpretations can vary depending on the analytical approach and study design. Our study provides unique insights by analyzing data from two institutions over an extended follow-up period, considering annual and cumulative NSAID exposure. This dual approach, combined with the comprehensive nature of our study, offers valuable context for understanding the conflicting findings in previous research. While a short-term decline in eGFR was evident in our cohort, the cumulative effects observed across the longer observation period were less consistent. Several factors may account for this discrepancy. First, patients exhibiting early signs of renal impairment may have had their NSAID therapy adjusted, discontinued, or transitioned to alternative treatments such as biologics, potentially underestimating the long-term impact. Second, variability in adherence, dose adjustments, and intermittent use could have affected long-term outcomes, although NSAID exposure was quantified using the MPR. Finally, attrition bias and selective follow-up may have influenced cumulative data interpretation, as patients with worsening renal function might have been lost to follow-up or managed outside the participating centers. These potential explanations highlight the complexity of evaluating the long-term renal safety of NSAIDs and warrant further investigation.

Our study also considered the role of COX-2 selectivity in NSAID-induced renal impairment. NSAIDs exert their effects primarily through the inhibition of COX enzymes, specifically COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 is responsible for maintaining baseline physiological functions, including protecting the gastric mucosa and regulating renal blood flow21. In contrast, COX-2 is more prominently expressed during inflammation and plays a key role in the production of prostaglandins that mediate pain and inflammatory responses. Nephrotoxicity can occur due to the inhibition of COX-2, especially in situations where renal perfusion is compromised. This nephrotoxicity occurs because COX-2 is upregulated in the kidneys in response to volume contraction or other states requiring increased renal blood flow22. By blocking COX-2, NSAIDs can disrupt this compensatory mechanism, potentially leading to adverse renal outcomes, including reduced GFR and, in more severe cases, acute kidney injury. However, their impact on renal function has been controversial23,24,25,26. In our analysis, both COX-2 selective and non-selective NSAIDs were associated with changes in eGFR. However, the patterns of these changes varied depending on the duration of NSAID exposure and the specific NSAID used. Notably, a significant decline in renal function was observed in patients with a higher cumulative exposure to both COX-2 selective and non-selective NSAIDs, suggesting that COX-2 selectivity does not entirely mitigate the potential for renal harm.

These findings have important clinical implications for the management of AS. Although NSAIDs remain a cornerstone of symptom control in AS, our results suggest that clinicians should exercise caution when prescribing these medications, especially for long-term use. Regular monitoring of renal function is crucial, and alternative therapeutic strategies should be considered for patients at a higher risk of renal impairment while using NSAIDs. Indeed, a recent study reported a decrease in NSAID use from 60.9 to 54.8% between 2006 and 2016, accompanied by an increase in the use of TNF inhibitors27. This trend may reflect a growing awareness of alternative treatments, such as TNF inhibitors, and the potential risks associated with prolonged NSAID use.

One of the key strengths of our study is the extensive follow-up period, which allowed us to capture long-term trends in renal function among patients with AS. The large, well-characterized cohort from multiple healthcare settings enhances the generalizability of our findings and provides a robust basis for assessing the impact of NSAIDs on renal health. However, the observational design of this study inherently limits our ability to establish causal inferences. Despite adjusting for various potential confounders, residual confounding remains a possibility. The reliance on electronic health records may introduce potential bias owing to incomplete or inaccurate data reporting. Additionally, the exclusion of patients with pre-existing renal disease or significant risk factors for kidney impairment means that our findings may not be generalizable to populations with higher baseline risks for kidney disease.

In conclusion, while NSAID exposure was associated with a statistically significant decline in eGFR in short-term analyses, there was no significant association between long-term NSAID use and renal function decline in patients with AS when accounting for cumulative exposure and time interaction.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NSAIDs:

-

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

- CKD-EPI:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration

- MDRD:

-

Modification of Diet in Renal Disease

- MPR:

-

Medication Possession Ratio

References

Dougados, M., Baeten, D. & Spondyloarthritis Lancet 377, 2127–2137. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60071-8 (2011).

van der Heijde, D. et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 978–991. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770 (2017).

Seo, M. R. et al. Korean treatment recommendations for patients with axial spondyloarthritis. J. Rheumatic Dis. 30, 151–169. https://doi.org/10.4078/jrd.2023.0025 (2023).

Park, J. S. et al. National Pharmacological treatment trends for ankylosing spondylitis in South korea: A National health insurance database study. PLoS One. 15, e0240155. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240155 (2020).

Braun, J. et al. 2010 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 896–904. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2011.151027 (2011).

Poddubnyy, D. et al. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on radiographic spinal progression in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from the German spondyloarthritis inception cohort. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71, 1616–1622. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201252 (2012).

Kwon, S. R., Kim, T. H., Kim, T. J., Park, W. & Shim, S. C. The epidemiology and treatment of ankylosing spondylitis in Korea. J. Rheumatic Dis. 29, 193–199. https://doi.org/10.4078/jrd.22.0023 (2022).

Wanders, A. et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs reduce radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 52, 1756–1765. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21054 (2005).

Baker, M. & Perazella, M. A. NSAIDs in CKD: are they safe?? Am. J. Kidney Dis. 76, 546–557. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.03.023 (2020).

Ingrasciotta, Y. et al. Association of individual Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory drugs and chronic kidney disease: A Population-Based case control study. PLOS ONE. 10, e0122899. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122899 (2015).

Harirforoosh, S. & Jamali, F. Renal adverse effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 8, 669–681. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740330903311023 (2009).

Sandler, D. P., Burr, F. R. & Weinberg, C. R. Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk for chronic renal disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 115, 165–165. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-115-3-165 (1991).

Perneger, T. V., Whelton, P. K. & Klag, M. J. Risk of kidney failure associated with the use of acetaminophen, aspirin, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl. J. Med. 331, 1675–1679. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199412223312502 (1994).

Kunitsu, Y. et al. Time until onset of acute kidney injury by combination therapy with triple whammy drugs obtained from Japanese adverse drug event report database. PLOS ONE. 17, e0263682. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263682 (2022).

Nelson, D. A., Marks, E. S., Deuster, P. A., O’Connor, F. G. & Kurina, L. M. Association of nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory drug prescriptions with kidney disease among active young and Middle-aged adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 2, e187896–e187896. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7896 (2019).

Gooch, K. et al. NSAID use and progression of chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Med. 120, 280e281–280e287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.015 (2007).

Koo, B. S., Hwang, S., Park, S. Y., Shin, J. H. & Kim, T. H. The relationship between long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and kidney function in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J. Rheumatic Dis. 30, 126–132. https://doi.org/10.4078/jrd.2023.0006 (2023).

Möller, B. et al. Chronic NSAID use and long-term decline of renal function in a prospective rheumatoid arthritis cohort study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 718. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204078 (2015).

Dougados, M. et al. ASAS recommendations for collecting, analysing and reporting NSAID intake in clinical trials/epidemiological studies in axial spondyloarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 249–251. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2010.133488 (2011).

Sikka, R., Xia, F. & Aubert, R. E. Estimating medication persistency using administrative claims data. Am. J. Manag Care. 11, 449–457 (2005).

Green, G. A. Understanding nsaids: from aspirin to COX-2. Clin. Cornerstone. 3, 50–59 (2001).

Weir, M. R. Renal effects of nonselective NSAIDs and Coxibs. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 69, 53–58 (2002).

Rossat, J., Maillard, M., Nussberger, J., Brunner, H. R. & Burnier, M. Renal effects of selective cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibition in normotensive salt‐depleted subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 66, 76–84 (1999).

Catella-Lawson, F. et al. Effects of specific Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 on sodium balance, hemodynamics, and vasoactive eicosanoids. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 289, 735–741 (1999).

Whelton, A. et al. Effects of celecoxib and Naproxen on renal function in the elderly. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 1465–1470. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.10.1465 (2000).

Silverstein, F. E. et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: a randomized controlled trial. Jama 284, 1247–1255 (2000).

Walsh, J., Hunter, T., Schroeder, K., Sandoval, D. & Bolce, R. Trends in diagnostic prevalence and treatment patterns of male and female ankylosing spondylitis patients in the united states, 2006–2016. BMC Rheumatol. 3, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-019-0086-3 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HR21C0198) and grant (2024IP0065) from the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.J.S. and Y.-G.K. conceptualized and initiated the project. S.Y.P., S.Y., S.K., and J.S.L. conducted the statistical analysis.Y.-E.K. drafted the main manuscript text, while Y.-J.H., S.M.A., S.H., C.-K.L., B.Y., O.J.S. and Y.-G.K. reviewed and revised it critically.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The protocols for this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB No. 2021 − 1147) and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No. X-2208-776-901).

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or planning for dissemination of our research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, YE., Park, S.Y., Lee, J.S. et al. Renal safety of Long-Term Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory drugs use in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Sci Rep 15, 21066 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07146-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07146-8