Abstract

This study aims to verify the performance of an electric tractor equipped with a four-wheel independent driving (4WID) electric axle (E-axle) system through simulation analysis using a MATLAB/Simulink model. The simulation model was validated through bench testing to ensure accuracy and reliability. Simulations were conducted while considering both travel speed and soil conditions to evaluate the slip and tractive efficiency of the electric tractor with the 4WID E-axle system. The results indicate that reducing travel speed decreases slip, which in turn improves tractive efficiency and enhances energy efficiency. The highest tractive efficiency was observed when slip was within the 10–20% range, indicating that this slip range corresponds to the optimal operating condition. The primary findings of this study identify the appropriate slip range and provide fundamental data for developing slip control algorithms for the 4WID E-axle system. Future research will focus on experimental validation and development of control algorithms based on the main results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global policies aimed at reducing petroleum dependence and emissions have garnered increasing attention in response to ongoing environmental challenges1,2,3. In the agricultural and construction off-road vehicle fields, substantial research has focused on replacing diesel engines with electric drive systems4,5,6,7. While electrification of auxiliary components such as pumps, fans, and cooling systems in agricultural machinery has progressed8, the electrification of powertrains remains in its early stages, with only a few commercial implementations available9. Current research on electric tractor drive systems primarily falls into two categories: 1) single-motor systems composed of a “single motor + multi-speed transmission” structure based on existing drive forms and structures, where the diesel engine is replaced by an electric motor10,11,12,13, and 2) dual-drive systems, such as hybrid tractors, which utilize two power sources13,14,15,16,17,18. Single-motor systems encounter difficulties in achieving full electrification due to the need for transmissions capable of handling varying loads and speeds. Additionally, high-power agricultural machinery further demands electric systems capable of handling heavy loads, which presents significant engineering challenges. Dual-drive (hybrid) systems are classified as either series or parallel. Series hybrids require high-torque motor driving technology, while parallel hybrids struggle to handle the sustained heavy loads typical of agricultural operations effectively19. In particular, dual-drive systems require an additional power coupling transmission to integrate two power sources, and their implementation poses significant technical challenges due to the need for advanced control strategies and algorithmic coordination20,21. Furthermore, the high costs associated with technology development and production, along with the lack of efficient energy storage systems, limit the adoption of hybrid electric tractors22. To overcome these limitations, recent research has explored axle-based systems23,24, which integrate motors, gear reducers, and wheel sets into each axle. Axle-based systems can utilize commercially available electric motors with relatively small torque capacities for each axle and eliminate the need for separate transmission systems. These systems enable high-efficiency operation through independent control of each axle and can achieve high traction force by simultaneously driving multiple motors. Additionally, axle-based systems allow for user-friendly automatic transmission configurations when driving axles through electric motors25. The overall efficiency of conventional diesel tractors and single-motor electric tractors has been reported to range from 0.27 to 0.38 and 0.47–0.7026, respectively, whereas E-axle systems demonstrate relatively higher efficiency, ranging from 0.54 to 0.7227. Consequently, there has been increasing interest in applying axle-based systems in agricultural machinery, including independent electric motor-driven systems for each wheel. Zhou and Zhou (2021) developed a compact transport platform capable of performing various agricultural tasks, utilizing the structural and operational advantages of electric agricultural vehicles to create a drive coordination control system28. Xu et al. (2021) proposed a four-wheel independent omnidirectional steering agricultural platform designed to reduce tracking errors and enhance vehicle lateral stability29. Bak and Jakobsen (2004) introduced a robotic platform with four identical wheel modules for weed mapping in fields, achieving four-wheel steering and driving capabilities30. However, most systems employ in-wheel motor (IWM) designs, which are typically applied to small agricultural machines performing tasks such as transportation, pest control, and weed removal. The spatial constraints of housing motors and reducers within wheels limit IWM systems’ capacity to handle heavy loads31. This makes them unsuitable for high-power agricultural machinery such as tractors, necessitating axle-based systems capable of handling heavy loads. Table 1 summarizes the major electric drive system types applied in agricultural machinery, outlining their main characteristics, limitations, and representative studies.

This study proposes an E-axle system that integrates a motor, reducer, and wheel into a single axle and investigates a four-wheel independent driving (4WID) electric axle (E-axle) tractor comprising four identical systems. Since no commercial applications of such 4WID E-axle tractors currently exist, performance evaluation is critical. Performance evaluations of electric tractors are typically conducted in simulation environments32,33, and the performance of key components (e.g., electric motors, inverters) is also suitably analyzed through simulations. Simulations provide the advantage of analyzing system characteristics and limitations under various conditions34, while minimizing time and cost associated with configuring and conducting physical tests35. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the performance of an E-axle system and tractor under various conditions using simulations. Specifically, the objectives are to: 1) develop a simulation model of an electric tractor equipped with an E-axle system in the MATLAB/Simulink environment, 2) conduct simulation analyses of the E-axle system under different soil and load conditions, and 3) evaluate both component-level and overall vehicle performance based on the simulation results.

Methods

E-axle system

The power transmission system of the electric tractor with a 4WID E-axle consisted of electric motors, two types of gear reducers (a helical gear reducer and a planetary gear reducer), and wheels, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The primary components of the E-axle included an AC induction motor (HPEVS AC-34, Hi Performance Electric Vehicle Systems, Ontario, CA, USA) and an inverter (Curtis 1238 series, Curtis Instruments, Inc., Mount Kisco, NY, USA). Four identical E-axles were installed, with one mounted on each axle of the vehicle. The motor was able to produce a maximum torque of 119.7 Nm (@550 A) and 143.9 Nm (@650 A), depending on the supplied current. Each motor had a rated power of 25 kW, resulting in a total system power output of 100 kW when using four identical E-axles, which was comparable to that of a mid-sized utility tractor. A helical gear reducer (gear ratio: 4.3) and a planetary gear reducer (gear ratio: 12.05) were connected to the output shaft of each motor to achieve the required driving torque at the wheels. The selection of these gear ratios was based on the requirements for the driving torque and the motor output torque under field conditions. The planetary gear reducer leveraged the knuckle arm from a conventional tractor’s front wheel assembly, which both simplified tire installation and functioned as the final reduction stage. The 380/85R24 R-1W agricultural tires (AGRIMAX RT 855, BKT, Mumbai, India) were installed. The use of four identical tires ensured even load distribution and uniform driving performance across all motors. Each motor of the 4WID E-axle was powered by a lithium iron phosphate (\(LiFePO_4\)) battery pack with a capacity of 14.6 kWh, giving the entire system a total energy capacity of 58.4 kWh with four battery packs. The batteries operated at a nominal voltage of 70.4 V and had a discharge rate (C-rate) of 2 C (30 minute discharge). Given that agricultural applications often require high instantaneous current under heavy load conditions, the selected C-rate ensured sufficient torque delivery while preventing battery degradation. A DC-DC converter (70.4 V to 12 V) was installed on one of the batteries to supply power to the controller. The controller’s current demand was approximately 0.4 A, negligible in terms of overall energy consumption. The inverter converted the input DC voltage into three-phase AC voltage to drive the AC induction motor. The batteries were charged using a charger compatible with a 220 V outlet, with the maximum output current of the charger set to 50 A to ensure safe charging. The detailed specifications of the electrical system are presented in Table 2.

Schematic of the electric tractor with 4WID E-axle system (reproduced from Baek et al. (2024)36).

Simulation analysis

Motor model

The induction motor model was developed in the MATLAB/Simulink environment based on the direct-quadrature (d-q) synchronous reference frame, as shown in Fig. 2. The model receives three-phase voltage and the rotor’s electrical angular velocity as inputs, and outputs motor currents, torque, and electrical angle. The upper section of the model implements the stator voltage equations, where the input three-phase voltage is transformed into d-q components to calculate the stator current. The lower section represents the rotor voltage equations, which incorporate the rotor’s electrical angular velocity to compute the motor torque. The electrical angle of the motor is determined by integrating variables derived from both the stator and rotor models.

The induction motor model was developed based on the voltage equations of the rotor and stator in the d-q synchronous reference frame37. The rotor voltage equations, presented in Equations (1) and (2), form the foundation of the model.

where \(R_r\) is the rotor resistance (\(\Omega\)), \(i_{dr}^e\) and \(i_{qr}^e\) are the d- and q-axis rotor current (A), respectively, \(\lambda _{dr}^e\) and \(\lambda _{qr}^e\) are the d- and q-axis rotor flux (Wb), respectively, and \(\omega _{sl}\) is the angular velocity difference between the stator’s rotating magnetic field and the rotor (rad/s).

Although the rotor voltage of an induction motor is theoretically zero, the induced voltage component in the rotor coils during operation must be considered. The voltage equations of the stator in the d-q synchronous reference frame are expressed in Equations (3) and (4).

where \(V_{ds}^e\) and \(V_{qs}^e\) are the d- and q-axis stator voltage (V), respectively, \(R_s\) is the stator resistance (\(\Omega\)), \(L_m\), \(L_r\), and \(L_s\) are the magnetizing, rotor, and stator inductances (H), respectively. \(i_{ds}^e\) and \(i_{qs}^e\) are the d- and q-axis stator current (A), respectively. \(\omega _e\) and \(\omega _r\) are the stator and rotor angular velocity (rad/s), respectively. \(\sigma\) is the leakage factor of the induction motor.

In this study, rotor flux-oriented vector control was applied to the induction motor, allowing the q-axis rotor flux component, \(\lambda _{qr}\), to be considered zero. Accordingly, the final d–q axis stator voltage equations in the synchronous reference frame are expressed in Equations (5) and (6)37.

Inverter model

As shown in Fig. 3, the inverter model includes a speed controller, flux controller, current controller, flux estimator, and coordinate transformation blocks. The speed and flux controllers generate the q-axis and d-axis stator current references, respectively, which are sent to the current controller. The current controller outputs d–q voltage commands, which are converted into three-phase voltages and applied to the AC induction motor. The flux estimator computes the electrical angular velocity using stator currents obtained by transforming the measured three-phase currents into the d–q reference frame. The estimated velocity is supplied to the abc–dq transformation block to enable accurate transformation of the measured currents into d–q components, which are subsequently used as feedback for the current controller.

The speed controller generates the q-axis stator current reference (\(i^e_{qs}\)) based on the angular velocity error. The corresponding transfer function, presented in Equation (7), consists of a proportional-integral (PI) controller, a low-pass filter with cut-off frequency \(\omega _{cc}\), and a gain term that reflects the system dynamics, characterized by the torque constant (\(K_T\)) and the total moment of inertia (\(J_s\))37.

where \(K_{psc}\) and \(K_{isc}\) are the proportional and integral gains of the speed controller, respectively, \(\omega _{cc}\) is the cut-off frequency (rad/s), \(K_T\) is the torque constant (Nm/A), and \(J_s\) is the moment of inertia (kg\(\cdot\)m\(\phantom{0}^2\)).

The flux controller regulates the d-axis rotor flux of the induction motor in the synchronous reference frame. The steady-state relationship between the rotor flux and the d-axis stator current is defined by Equation (8). The controller is implemented using a proportional-integral (PI) regulator, where the d-axis stator current serves as the control output. The rotor flux is calculated based on the magnetizing inductance and the measured stator current and is used in the feedback loop to achieve flux regulation. The closed-loop transfer function describing the dynamic response of the d-axis rotor flux to its reference input is presented in Equation (9)37.

where \(\lambda _{dr}^e\) is the d-axis rotor flux (Wb), \(L_m\) is the magnetizing inductance (H), and \(i_{ds}^e\) is the d-axis stator current (A).

where \(K_{pfc}\) and \(K_{ifc}\) are the proportional and integral gains of the flux controller, respectively.

The current controller is modeled based on the d-axis and q-axis stator voltage equations, as presented in Equations (10) and (11)37. The controller was designed to compute the reference voltages (\(V_{ds}^{e*}\), \(V_{qs}^{e*}\)) required to achieve the desired stator current response. The reference voltages are transformed into a voltage vector in the synchronous reference frame (\(V_{dqs}^{e*}\)) using the rotation matrix (\(e^{j\theta _e}\)). The voltage vector was modulated by the pulse-width modulation (PWM) controller to produce the actual applied voltage (\(V_{dqs}^{e}\)). The applied voltage is subsequently transformed back into the d- and q-axis components using the inverse rotation (\(e^{-j\theta _e}\)), which are used as feedback signals for current regulation.

where \(R\) is the winding resistance (\(\Omega\)), \(L\) is the stator inductance (H), and \(e_{ds}^e\), \(e_{qs}^e\) are the electromotive-induced force of the stator (V).

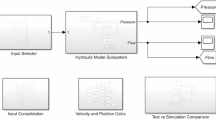

Vehicle model

Figure 4 illustrates the vehicle model developed in the MATLAB/Simulink environment to simulate the operational load and soil conditions of the 4WID E-axle tractor. The vehicle model provides feedback on wheel speed and angular displacement based on the motor output torque from the E-axle, and generates key simulation results, including wheel torque, slip, tractive force, tractive efficiency, and displacement. Slip and tractive efficiency are calculated using Equations (12) and (13), respectively. A tire model based on the Magic formula (Pacejka and Bakker, 1992) is incorporated to accurately represent tire behavior under varying soil and load conditions38. The model architecture consists of both custom-developed subsystems and predefined blocks from Simscape toolboxes. Tire dynamics were modeled using the tire (Magic formula) block, which calculates longitudinal tire force based on slip and vertical load. The vehicle body block simulates longitudinal motion, accounting for vehicle mass and resistance forces. To measure key mechanical variables, torque sensor blocks, force sensor blocks, and rotational motion sensor blocks from the Simscape were employed. These sensors provide wheel torque, longitudinal force, and angular velocity, respectively. The torque source block was used to apply motor torque from E-axle model to each wheel. Custom subsystems were developed to compute wheel slip, wheel speed, angular displacement, and tractive efficiency. Tractive efficiency was calculated as the ratio of traction power to wheel driving power, based on real-time simulation data. The computed wheel speed and angular displacement were used as feedback inputs to the E-axle model to reflect the dynamic interaction between the wheel and the ground. These outputs enabled performance evaluation under varying soil and load conditions. The integration of physics-based modeling and control logic allowed for realistic simulation of the 4WID E-axle tractor’s traction behavior and efficiency.

where \(s\) is the slip (%), \(V_{th}\) is the theoretical travel speed (km/h), and \(V_a\) is the actual travel speed (km/h).

where \(TE\) is the tractive efficiency (%), \(P_t\) is the traction power (kW), and \(P_w\) is the wheel driving power (kW).

The vehicle model is designed to apply a rearward traction load and incorporates a tire model based on the Magic formula38. This formula estimastes the longitudinal force of the tire by analyzing the interaction between the tire and the road surface using the coefficients B, C, D, and E, as described in Equation (14). However, predefined coefficients for calculating the longitudinal force of a tractor tire on soil were not available. Therefore, traction force was instead computed using the Brixius model39, as expressed in Equations (15) and (16). The coefficients for the Brixius model were subsequently estimated by comparing the results with those obtained from the Magic formula.

where \(F\) is the force exerted by the tire (N), \(B\) is the stiffness factor, \(C\) is the shape factor, \(D\) is the peak factor (N), and \(E\) is the curvature factor.

where \(GTR\) is the gross traction ratio, \(B_n\) is the mobility number, and \(s\) is the slip ratio.

where \(CI\) is the cone index (kPa), \(W\) is the total weight (N), and \(b_t\), \(d_t\), \(\delta _t\), and \(h_t\) are the width, overall diameter, deflection, and section height of the tire (m), respectively.

Figures 5 (a) and (b) illustrate the Brixius model and the Magic formula under soft and hard soil conditions, respectively. To ensure consistency between the models, the coefficients of the Magic formula were tuned to closely match the gross traction ratio (GTR) as a function of slip. The coefficients were determined using a trial-and-error method to fit the GTR with respect to slip. The final values were set to B = 4.3, C = 1.6, D = 0.62, and E = 1 for soft soil conditions, and B = 5.5, C = 1.4, D = 0.94, and E = 1 for hard soil conditions.

Simulation conditions

Figure 6 illustrates the overall research process of this study. The E-axle model and the vehicle model were independently developed and subsequently integrated within the MATLAB/Simulink environment. The E-axle model was calibrated and validated using data obtained from the E-axle test bench. In the integrated simulation, the E-axle model receives the vehicle speed command (\(V_{x}\)) and produces the corresponding motor torque (\(T_{m}\)), which is applied as input to the vehicle model. The vehicle model, in turn, provides feedback to the E-axle model in the form of motor speed (\(N_{m}\)) and angular displacement (\(\theta _{d}\)) to the E-axle model. The final outputs of the simulation were the slip characteristics of the E-axle and the tractive efficiency of the tractor, which were used to evaluate the performance of the 4WID E-axle tractor. Simulations were conducted by varying the rearward load applied to the vehicle model and the coefficients representing soil properties, which were derived based on the Magic formula and the Brixius model. The rearward force was calculated based on the longitudinal force generated by implement–soil interaction, which was determined according to the traction force corresponding to the load factor of the motors mounted on the E-axle tractor. The load factor was set to 30–50% for low-load operations (e.g., trailer towing) and 50–70% for high-load operations (e.g., plow tillage). The longitudinal force was continuously applied to the rear of the vehicle throughout the simulation. The target travel speed of the E-axle tractor was set to 7 km/h for both high-load and low-load operations using a control command. Additional simulations were conducted at 5 km/h to evaluate the impact of reduced speed on soft soil under high-load conditions. The load factors and travel speeds were established based on data measured in previous studies and typical field operation conditions, and were adopted to perform simulations under conditions representative of actual agricultural operations40,41. All key parameters used in each model are summarized in Table 3.

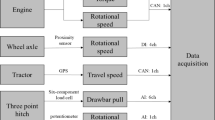

Model validation

The performance evaluation of the E-axle system was conducted to validate the simulation model. The configuration of the test bench of the E-axle is illustrated in Fig. 7. The inverter was supplied with DC power, and a three-phase voltage was applied to the induction motor. The rotational speed of the induction motor was controlled using a dynamometer to achieve the desired target speed. Torque control of the inverter was performed based on a throttle voltage input generated by a voltage signal generator (PXIe-8840, National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). To minimize mechanical shocks to the dynamometer, a sinusoidal throttle voltage with a frequency of 0.05 Hz was applied. Real-time measurements of the motor’s output torque and rotational speed were obtained using a torque meter (HBM T40B, HBM, Darmstadt, Germany) and an encoder (HMC16, Baumer, Frauenfeld, Switzerland), respectively. The motor’s rotational speed ranged from 500 to 5000 rpm. Data including the inverter’s input current and voltage as well as the motor’s output torque and current, were collected for different rotational speeds.

To evaluate the agreement between the simulated and experimental results, correlation analysis and an independent samples t-test were performed using data analysis software (OriginPro 2018 SR1 v9.5.1.195, OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). The t-test, based on Equation (17), was used to determine whether a statistically significant difference existed between the two datasets.

where \(t_s\) is the calculated T statistic, \(\bar{X}_1\) and \(\bar{X}_2\) are the sample means of the groups, \(s_p\) is the pooled standard deviation of the groups, and \(n_1\) and \(n_2\) are the sample sizes of the groups.

Results

Validation results

Figure 8 presents the measured and simulated data used to validate the motor-inverter model of the E-axle system. The motor’s maximum torque under full-load conditions was compared across a range of rotational speeds from 0 to 5000 rpm. The average efficiency of the motor-inverter system was 70.0% over the entire speed range, with a peak efficiency of 79.1% observed at 3000 rpm. Correlation analysis yielded a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.99, indicating a very strong linear relationship between the measured and simulated values. The correlation was statistically significant, with a p-value less than 0.001. Furthermore, the independent samples t-test produced a t-statistic of 0.1 and a p-value of 0.92, indicating no statistically significant difference between the two datasets. These findings support the conclusion that the simulation model provides results that are statistically consistent with the measured data from the test bench.

Simulation results

Slip

Figure 9 presents the simulation results for slip of the 4WID E-axle under varying load and soil conditions, derived from motor rotational speed and vehicle speed data. As shown in Fig. 9a, for the front E-axle, the maximum slip occurs under high-load soft soil conditions at 55.8%, followed by 48.6% (high-load hard soil), 23.0% (low-load hard soil), and 21.8% (low-load soft soil). Under high-load conditions, the maximum slip is approximately 14.7% higher in soft soil than in hard soil, while the difference is negligible under low-load conditions. The average slip values are 36.8% (high-load hard soil), 34.5% (high-load soft soil), 17.0% (low-load soft soil), and 16.9% (low-load hard soil). In contrast, Fig. 9b shows that for the rear E-axle, the maximum slip reaches 60.8%, followed by 51.3% (high-load hard soil), 24.2% (low-load soft soil), and 24.2% (low-load hard soil). On average, the rear E-axle exhibits 7.2% higher slip than the front E-axle under high-load conditions and 8.4% higher under low-load conditions. The average slip values for the rear E-axle are 39.9% (high-load soft soil), 38.0% (high-load hard soil), 17.6% (low-load soft soil), and 17.5% (low-load hard soil). These results indicate that slip increases with higher loads and softer soil conditions, particularly at the rear E-axle. The rear E-axle exhibits greater slip due to the rear-applied resistive force implemented in the simulation model. The drawbar load is applied through the rear axle, which increases tractive demand and vertical loading on the rear wheels. The elevated traction load enhances soil deformation and reduces tractive efficiency, resulting in a higher slip ratio at the rear E-axle compared to the front wheels. A summary of the simulation results is provided in Table 4.

Tractive efficiency

The performance of the E-axle was evaluated in terms of tractive efficiency under simulated conditions. Tractive efficiency is defined as the proportion of wheel drive force converted into traction power during agricultural operations, and serves as a key parameter for assessing traction performance. Figure 10 presents the tractive efficiency of the E-axle tractor under varying load and soil conditions. The average tractive efficiency was 90.1% for low-load hard soil, 89.1% for high-load hard soil, 85.8% for low-load soft soil, and 72.9% for high-load soft soil. Tractive efficiency was 18% higher under high-load hard soil conditions compared to high-load soft soil conditions and 5% higher in hard soil conditions under low-load conditions. Notably, the average tractive efficiency under high-load soft soil conditions decreased by approximately 19.1% compared to low-load hard soil conditions. The maximum tractive efficiency, as summarized in Table 5, is 90.9% for low-load hard soil, 89.4% for high-load hard soil, 86.8% for low-load soft soil, and 80.3% for high-load soft soil. These results indicate that tractive efficiency decreases as soil hardness decreases, likely due to increased energy losses caused by slip.

Performance by different travel speeds

Figure 11a presents the simulation results for E-axle slip under different travel speed conditions. Since plow tillage operations are typically performed at speeds between 5 and 7 km/h, the simulation was conducted at a reduced travel speed of 5 km/h to assess its impact on performance. At 5 km/h, the front E-axle exhibited maximum and average slip values of 36.0% and 18.9%, respectively, while the rear E-axle recorded 9.3% and 8.9%, respectively. In comparison, at 7 km/h, the corresponding values increased to 55.8% and 34.5% for the front E-axle, and 60.8% and 39.9% for the rear E-axle, as summarized in Table 6. These results suggest that reducing travel speed under high-load and soft soil conditions effectively minimizes slip and improves E-axle performance. Figure 11b illustrates the effect of travel speed on tractive efficiency. The average tractive efficiency of the E-axle tractor is 85.1% at 5 km/h and 72.9% at 7 km/h, as shown in Table 7.

Discussion

Figure 12 illustrates the average slip values of the front and rear E-axles and the tractive efficiency of the 4WID E-axle tractor under different travel speeds. The simulation was conducted under high-load and soft soil conditions, representative of plow tillage operations. When the travel speed was reduced, the average slip decreased by 45% for the front E-axle and 78% for the rear E-axle. In contrast, the tractive efficiency increased by approximately 12.2%p as the travel speed was reduced, due to the minimized losses resulting from the reduction of slip. The observed improvement in tractive efficiency is estimated to result in a battery energy saving of approximately 14.3%, assuming an equivalent field task and workload. With a total battery capacity of 58.4 kWh (consisting of four 14.6 kWh battery packs), this corresponds to a reduction of approximately 8.35 kWh in energy consumption. The resulting energy savings can contribute to extended operating duration or increased field coverage under the same energy constraints. These findings suggest that appropriate reductions in travel speed can enhance tractive efficiency and contribute to more effective energy management in agricultural operations.

Figure 13a illustrates the relationship between tractive efficiency and slip for the E-axle tractor. Under high-load conditions at 7 km/h, excessive slip made it difficult to establish a clear correlation between tractive efficiency and slip. Therefore, data collected under low-load conditions at 7 km/h and high-load conditions at 5 km/h were analyzed to clarify this relationship. Tractive efficiency increases as slip increases within an effective operating range, but begins to decrease once slip becomes excessive. Additionally, slip values exceeding 30% were considered unreliable due to the rapid transition of the wheels into an idling state42. The average tractive efficiency across all slip ranges was 90.1% for low-load hard soil, 85.8% for low-load soft soil at 7 km/h, and 85.1% for high-load soft soil at 5 km/h. Within the 10–20% slip range, the average tractive efficiency was 90.6% in low-load hard soil at 7 km/h, 86.3% in low-load soft soil at 7 km/h, and 85.7% in high-load soft soil at 5 km/h. These results indicate that tractive efficiency was highest under low-load hard soil conditions and was lowest under high-load soft soil conditions. However, regardless of load or soil conditions, the E-axle tractor achieved peak tractive efficiency within the 10–20% slip range. Previous studies on agricultural tractors reported that slip varied depending on operating conditions and environments. However, the slip range in which tractive efficiency reached its maximum remained relatively consistent. A review of these studies identified an optimal slip range of 8–16%, which closely aligns with the findings of this study43,44,45,46. Outside the optimal slip range, the average tractive efficiency dropped to 87.2% (low-load hard soil, 7 km/h), 82.6% (low-load soft soil, 7 km/h), and 80.6% (high-load soft soil, 5 km/h), indicating a 4–6% improvement when operating within the optimal slip range.

A slip-target control approach is proposed to maintain optimal tractive efficiency by dynamically adjusting wheel speed based on real-time slip estimation, as illustrated in Fig. 13b. The optimal slip range, identified from simulation results, is defined as 10–20% and serves as the threshold for control. Slip is estimated using GPS-derived travel speed and motor rotational speed. When the estimated slip exceeds 20%, the control logic reduces the wheel speed to suppress excessive slip. Once the slip returns to the target range, the original speed command is restored. This adaptive slip-based control scheme can be independently applied to each wheel via four inverters.

Conclusion

This study aimed to develop a simulation model of the 4WID E-axle electric tractor and to evaluate its slip and tractive efficiency under various operating conditions. The simulation model was developed in the MATLAB/Simulink environment and validated through bench testing and system analysis. The simulation results provided quantitative insights into the slip and tractive efficiency of the 4WID tractor across different soil types, load levels, and travel speeds. The key findings of this study are summarized as follows:

-

Soil-specific Magic formula coefficients were derived using the Brixius model, enabling realistic slip analysis under both soft and hard soil conditions.

-

Consistent with conventional tractor dynamics, the rear wheels exhibited greater slip than the front wheels. Slip increased significantly under soft soil and high-load conditions, resulting in reduced tractive efficiency. In particular, tractive efficiency under high-load soft soil conditions decreased by approximately 19.1% compared to low-load hard soil conditions.

-

Reducing travel speed within an appropriate range improved tire–soil contact, which led to a reduction in slip and an increase in tractive efficiency. Specifically, under high-load soft soil conditions, tractive efficiency increased by approximately 12.2%p when the travel speed was reduced from 7 km/h to 5 km/h.

-

The relationship between slip and tractive efficiency of the 4WID E-axle tractor was analyzed. The results confirmed that optimal tractive efficiency was achieved when slip was maintained within the 10–20% range.

These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the simulation model and provide valuable insights for the development of traction control strategies for electric tractors. The practical implications and potential applications are outlined below:

-

The soil-dependent Magic formula coefficients derived in this study can be utilized in future simulation-based vehicle dynamics analyses that incorporate varying soil conditions.

-

The observed improvements in tractive performance at lower travel speeds support the development of speed-based traction control strategies for agricultural machinery.

-

Identification of the optimal slip range (10–20%) lays a foundation for developing slip control algorithms for 4WID agricultural machines, ultimately contributing to the design of electric tractors with enhanced energy efficiency and traction performance.

However, the primary limitation of this study is that the evaluation was conducted solely in a simulation environment. While the E-axle model itself was validated, full-vehicle testing was not performed. Therefore, future work will involve real-world field testing to validate the complete vehicle model, as well as the development of adaptive slip control algorithms based on the results presented in this study. These efforts will further advance the technological foundation for the electrification of agricultural machinery.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wu, Z. et al. Modelling and verification of driving torque management for electric tractor: Dual-mode driving intention interpretation with torque demand restriction. Biosyst. Engi. 182, 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2019.04.002 (2019).

Kim, W.-S. et al. Evaluation of exhaust emissions of agricultural tractors using portable emissions measurement system in Korean paddy field. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53995-0 (2024).

Ushakov, S., Valland, H. & Æsoy, V. Combustion and emissions characteristics of fish oil fuel in a heavy-duty diesel engine. Energy Convers. Manag. 65, 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENCONMAN.2012.08.009 (2013).

Yang, H., Sun, Y., Xia, C. & Zhang, H. Research on energy management strategy of fuel cell electric tractor based on multi-algorithm fusion and optimization. Energies https://doi.org/10.3390/en15176389 (2022).

Li, X., Xu, L., Liu, M., Yan, X. & Zhang, M. Research on torque cooperative control of distributed drive system for fuel cell electric tractor. Comput. Electron. Agric. 219, 108811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.108811 (2024).

Hao Luo, Z. et al. Learning-based double layer control method of yaw stability simulation research for rear wheel independent drive electric tractor plowing operation. Comput. Electron. Agricul. 221, 108985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.108985 (2024).

Lin, T. et al. A double variable control load sensing system for electric hydraulic excavator. Energy 223, 119999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.119999 (2021).

Barthel, J., Görges, D., Bell, M., & Münch, P. Energy management for hybrid electric tractors combining load point shifting, regeneration and boost.,. In: IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference. VPPC, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1109/VPPC.2014.7007061 (2014).

Brenna, M., Foiadelli, F., Leone, C., Longo, M. & Zaninelli, D. Feasibility Proposal for Heavy Duty Farm Tractor. In: 2018 International Conference of Electrical and Electronic Technologies for Automotive, AUTOMOTIVE 2018 1–6, https://doi.org/10.23919/EETA.2018.8493236 (2018).

Baek, S.-Y. et al. Design verification of an E-driving system of a 44 kW-class electric tractor using agricultural workload data. J. Drive Control 19, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.7839/ksfc.2022.19.4.036 (2022).

Wang, Q., Wang, X., Wang, W., Song, Y. & Cui, Y. Joint control method based on speed and slip rate switching in plowing operation of wheeled electric tractor equipped with sliding battery pack. Computer. Electron. Agric. 215, 108426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2023.108426 (2023).

Yang, C. W. et al. Analysis of driving axle and PTO power transmission efficiency of an 18 kW-class single motor electric tractor. Korean J. Agric. Sci. 51, 921–933. https://doi.org/10.7744/kjoas.510439 (2024).

Mocera, F., Somà, A., Martelli, S. & Martini, V. Trends and future perspective of electrification in agricultural tractor-implement applications. Energies 16, 6601–6636. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16186601 (2023).

Wen, C. K. et al. Design and verification innovative approach of dual-motor power coupling drive systems for electric tractors. Energy 247, 123538–123559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.123538 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Research on global optimal energy management strategy of agricultural hybrid tractor equipped with CVT. World Electr. Veh. J. 14, 127–144. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj14050127 (2023).

Mocera, F. & Somà, A. Analysis of a parallel hybrid electric tractor for agricultural applications. Energies 13, 3055–3071. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13123055 (2020).

Mocera, F., Martini, V. & Somà, A. Comparative analysis of hybrid electric architectures for specialized agricultural tractors. Energies 15, 1944–1965. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15051944 (2022).

Troncon, D. & Alberti, L. Case of study of the electrification of a tractor: Electric motor performance requirements and design. Energies 13, 2197–2211. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13092197 (2020).

Pascuzzi, S., Łyp-Wrońska, K., Gdowska, K. & Paciolla, F. Sustainability evaluation of hybrid agriculture-tractor powertrains. Sustainability (Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031184 (2024).

Rossi, C., Pontara, D., Falcomer, C., Bertoldi, M. & Mandrioli, R. A hybrid-electric driveline for agricultural tractors based on an e-cvt power-split transmission. Energies 14, 21–43. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14216912 (2021).

Dou, H., Wei, H., Zhang, Y. & Ai, Q. Configuration design and optimal energy management for coupled-split powertrain tractor. Machines 10, 1175–1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines10121175 (2022).

Scolaro, E. et al. Electrification of agricultural machinery: A review. IEEE Access 9, 164520–164541. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3135037 (2021).

Fahlgren, E. & Söderberg, D. Torque vectoring using e-axle configuration for 4WD battery electric truck. Master’s thesis, Chalmers University of Technology (2022).

Deng, X. et al. Research on dynamic analysis and experimental study of the distributed drive electric tractor. Agriculture (Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13010040 (2023).

Baek, S.-Y. et al. Traction performance evaluation of the electric all-wheel-drive tractor. Sensors 22, 785–801. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22030785 (2022).

Han, T.-H. Development of Methods for Evaluating Effective Power and Battery SOC for Electric Tractors. Ph.D. thesis, Chungnam National University (2025).

Baek, S.-Y. Development of 4-Wheel Independent Driving E-axle System and Traction Control Model for a 100-kW Electric Tractor. Ph.D. thesis, Chungnam National University (2024).

Zhou, X. & Zhou, J. Optimization of autonomous driving state control of low energy consumption pure electric agricultural vehicles based on environmental friendliness. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 48767–48784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14125-9 (2021).

Xu, Q., Li, H., Wang, Q. & Wang, C. Wheel deflection control of agricultural vehicles with four-wheel independent omnidirectional steering. Actuators 10, 334–352. https://doi.org/10.3390/act10120334 (2021).

Bak, T. & Jakobsen, H. Agricultural robotic platform with four wheel steering for weed detection. Biosyst. Eng. 87, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2003.10.009 (2004).

Ali, M. et al. Evaluation of gear reduction ratio for a 1.6 kW multi-purpose agricultural electric vehicle platform based on the workload data. Korean J. Agric. Sci. 51, 133–146. https://doi.org/10.7744/kjoas.510204 (2024).

Zhang, W., Liu, M., Xu, L., Zhao, X. & Fu, X. Simulation of Hydraulic Suspension System of Electric Tractor Based on Matlab-AMESim. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1903, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1903/1/012003 (2021).

Chen, Y., Xie, B., Du, Y. & Mao, E. Powertrain parameter matching and optimal design of dual-motor driven electric tractor. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 12, 33–41 (2019).

Park, M.-J. et al. Development of threshing cylinder simulation model of combine harvester for high-speed harvesting operation. Korean J. Agric. Sci. 50, 499–510. https://doi.org/10.7744/kjoas.500315 (2023).

Son, M.-A. et al. Development and performance evaluation of lateral control simulation-based multi-body dynamics model for autonomous agricultural tractor. Korean J. Agric. Sci. 50, 773–784. https://doi.org/10.7744/kjoas.500415 (2023).

Baek, S.-Y. et al. Data analysis and traction performance evaluation of an electric all-wheel drive tractor during agricultural operation. J. ASABE 67, 1217–1229 (2024).

Sul, S.-K. Control of Electric Machine Drive Systems (Hongreung Science Publishing Co., China, 2016).

Pacejka, H. B. & Bakker, E. The magic formula tyre model. Vehic. Syst. Dyn. 21, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423119208969994 (1992).

Al-Hamed, S. A., Grisso, R. D., Zoz, F. M. & Von Bargen, K. Tractor performance spreadsheet for radial tires. Comput. Electron. Agric. 10, 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1699(94)90035-3 (1994).

Baek, S.-M. et al. Analysis of engine load factor for a 78 kW class agricultural tractor according to agricultural operations. J. Drive Control 19, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.7839/ksfc.2022.19.1.016 (2022).

Kim, W.-S. et al. Development of a prediction model for tractor axle torque during tillage operation. Appl. Sci. 10, 4195–4213. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10124195 (2020).

Kim, K. D. et al. Drawbar pull estimation in agricultural tractor tires on asphalt road surface using magic formula. J. Korean Soc. Manuf. Process Eng. 20, 92–99 (2021).

Soylu, S. & Çarman, K. Fuzzy logic based automatic slip control system for agricultural tractors. J. Terramechanics 95, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jterra.2021.03.001 (2021).

de Melo, R. R., Tofoli, F. L., Daher, S. & Antunes, F. L. M. Wheel slip control applied to an electric tractor for improving tractive efficiency and reducing energy consumption. Sensors 22, 4527–4548. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22124527 (2022).

Kumar, A. A., Tewari, V. & Nare, B. Embedded digital draft force and wheel slip indicator for tillage research. Comput. Electron. Agric. 127, 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2016.05.010 (2016).

Zoz, F. & Grisso, R. Traction and tractor performance. ASAE Distinguish. Ser. 27 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program (20018359, Development of agricultural machinery and smart operation system for field farming solutions) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MI, Korea).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y.B and C.G.P conceived the experiments, S.Y.B and H.H.J conducted the experiments, C.G.P developed the analysis software, S.Y.B and Y.J.K analysed the results, S.Y.B wrote the original draft of the manuscript. H.H.J and Y.J.K contributed to manuscript revision and editing, Y.J.K supervised the project, Y.J.K secured funding for the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baek, S., Jeon, H., Park, C. et al. Slip and tractive efficiency of an electric tractor with a 4WID E-axle system. Sci Rep 15, 28424 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08572-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08572-4