Abstract

Aiming at the situation where photovoltaic power stations in remote areas suffer from poor communication networks, which makes reliable acquisition of satellite precise orbit data and clock offset data unattainable, this paper employs PPP-B2b combined with broadcast ephemeris to obtain precise orbit and clock offset data. To address the impact of multipath errors during inspection missions, this study focuses on analyzing the influence of pseudorange multipath errors on observation values at different frequency points, as well as the relationship between observation data quality and multipath errors. The linear combination method utilizing multi-frequency carrier phase and pseudorange observations is applied to mitigate pseudorange multipath errors. Experimental results demonstrate that after correction, static positioning accuracy improved by 6.58%, 10.28%, and 11.96% in the E, N, and U directions respectively, while dynamic positioning accuracy showed enhancements of 9.82%, 10.06%, and 10.41% in the corresponding directions. Validation through hardware testing platform experiments confirms the method’s applicability in the specified environmental conditions. Compared with traditional precise point positioning methods, this approach enables high-precision single-station positioning without reliance on communication networks. Subsequent pseudorange multipath error correction further enhances positioning accuracy for inspection UAVs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the field of power inspection, inspection drones are increasingly widely applied. Compared to traditional manual inspection, this approach enables more precise detection and lower costs. Current satellite positioning algorithms for inspection drones can generally be categorized into Standard Point Positioning, Real-Time Kinematic positioning, and Precise Point Positioning. Li et al. integrated sensors such as GPS positioning modules and infrared thermal imagers to achieve defect detection and condition monitoring tasks in large-scale photovoltaic power plants1. Addabbo et al. employed a GNSS receiver with a standard positioning algorithm to localize the position of drones2. Mesas et al. conducted single-point positioning for drones using a ublox receiver and developed an open airborne hardware-software system for monitoring solar power plants3, However, the positioning accuracy of this system can only reach 2.5 m. Zhou et al. adopted GPS positioning under conditions of strong GPS signal availability4, In areas with poor GPS signals during drone flight, Bluetooth positioning was adopted to assist localization, thereby enhancing the reliability of the inspection drone’s positioning. The aforementioned positioning methods fall under the category of Standard Point Positioning (SPP). Due to inherent theoretical limitations and the inability to precisely model various errors, SPP-based approaches cannot achieve sub-meter level accuracy.

Zhai et al. employed the RTK positioning method to obtain the coordinate information of the UAV5. Lee et al. employed the RTK-VRS (Virtual Reference Station) method for UAV positioning6, This approach generates precise orthophotos and 3D terrain modeling data through images captured. Zhou et al. address the problem that the occlusion and multipath effect of satellite signals make GNSS positioning unable to always obtain the location of UAVs. A real-time positioning method combining GNSS and total station is proposed. High positioning accuracy can also be achieved in monitoring scenarios with complex structures7. While RTK positioning achieves centimeter-level accuracy, its performance is constrained by the baseline length between reference and rover stations, lacks flexibility, and relies on frequent data communication between stations, which compromises the continuity and reliability of positioning outputs.

The precise point positioning method was proposed by Zumberge in 1997, which utilizes dual-frequency observations to calculate the receiver’s coordinates and achieves centimeter-level positioning accuracy8. Wang et al. adopted an uncombined model to uniformly process single-frequency and dual-frequency data from observed satellites9, independently parameterizing clock terms to address the inconsistency between code and carrier phase measurements. Aggrey et al. performed PPP using raw GNSS measurements from smartphones10, with data screening based on C/N0 thresholds. Nie et al. employed low-cost receivers to track civil signals such as GPS L2C and L5, and utilized the ionosphere-free combination model for precise point positioning solutions11. Liu evaluated BDS-3 standalone PPP performance12, demonstrating convergence to 0.3-meter accuracy within 14 min. Carlin et al. evaluated the performance of GPS and Galileo broadcast ephemeris in achieving precise point positioning13, demonstrating that positioning accuracy was improved to some extent through SISRE compensation. Ren et al. evaluated the PPP-B2b service of BeiDou and found that within China14, the PPP-B2b service achieves clock offset errors of 0.05–0.18 ns for BDS-3 satellites. Geng et al. discussed the application of PPP-B2b services for maritime positioning in environments with poor communication networks15. Xu et al. evaluated the PPP-B2b precision single point positioning service of BDS-316. Lai et al. evaluated the performance of PPPP -B2b in the urban environment17. Zhou et al. achieved real-time single-frequency precise single-point positioning by using the PPPP-B2b method18. This method addresses the issue of inapplicability of the Precise Point Positioning (PPP) approach in maritime environments due to poor communication networks. However, it overlooks the impact of significant fluctuations in environmental noise caused by the dynamic nature of marine conditions on positioning accuracy.

In summary, the positioning of inspection UAVs in distributed, remote small and medium-sized photovoltaic power stations faces the following issues: 1, The poor communication networks in these remote photovoltaic stations make traditional Precise Point Positioning (PPP) unreliable for acquiring precise orbit and clock offset products, thereby compromising positioning reliability. 2, Significant positioning accuracy degradation caused by multipath errors from photovoltaic module panels.

Therefore, this paper employs PPP-B2b messages to address satellite orbit corrections and utilizes a multipath combination method to mitigate multipath errors, thereby enhancing the positioning accuracy of inspection UAVs. Additionally, multipath errors in pseudorange observations containing measurement noise on B1, B2b, and B3 frequencies are extracted and analyzed. A comprehensive evaluation of each frequency’s multipath resistance capability is conducted by integrating signal strength, pseudorange multipath error magnitude, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) across different frequencies. Finally, pseudorange multipath errors are processed through data manipulation techniques.

Correction of satellite orbit and satellite clock difference

The PPP-B2b navigation message correction information includes orbit corrections, clock offset corrections, and code bias corrections. These corrections are applied to the satellite positions and clock offsets derived from the broadcast ephemeris by matching the broadcast ephemeris, thereby obtaining precise satellite orbits and clock offsets.

The matching of correction information is achieved through version numbers within the messages. In PPP-B2b, different message types are matched using the IOD SSR (Issue of Data State Space Representation). When different message types share the same IOD SSR, their data can be matched and used together. The orbit and clock bias corrections for each satellite also include an IOD Corr (Issue of Data Correction). Corrections with the same IOD Corr are considered to belong to the same satellite’s orbit and clock bias adjustments. The version matching between corrections and the broadcast ephemeris is accomplished by aligning the IODN (Issue of Data Navigation) with the IODC (Issue of Data Clock) in the BDS CNAV1 message. When the IODN matches the IODC, the PPP-B2b correction values can be applied. The specific correction methods for orbit and clock bias are as follows:

In the equation, \(X_{orbit}\) represents the satellite position after correction, \(X_{brosdcast}\) denotes the broadcast ephemeris position, \(e_{radial},e_{along},e_{cross}\) are the unit vectors in the radial, along-track, and cross-track directions, respectively. \(\delta O\) are the correction values parsed from the PPP-B2b message. \(t_{satellite}\) represents the corrected satellite clock bias, \(t_{broadcast}\) is the satellite clock bias calculated from the broadcast ephemeris, \(C_{0}\) denotes the clock bias correction parsed from the PPP-B2b message, c is the speed of light.

To verify the accuracy after correction, this study collected broadcast ephemeris, PPP-B2b messages received by the receiver, and precise satellite orbits and clock errors downloaded from the IGS analysis center over a 2-hour period. The orbits and clock errors derived from the broadcast ephemeris of the C19 satellite, as well as those corrected using PPP-B2b update information, were compared with the precise satellite orbits and clock errors published by IGS. The accuracy of the corrected products in the X, Y, Z directions and clock errors was analyzed. Figure 1 illustrates deviations between corrected/uncorrected data and IGS reference data. In Fig. 1a, the deviations in the X-direction between the orbit data before and after correction and the IGS precise orbit data are shown; Fig. 1b shows the deviations in the Y-direction; Fig. 1c illustrates the deviations in the Z-direction; and Fig. 1d presents the deviations between the satellite clock bias data before and after correction and the IGS precise clock bias data.

As shown in Fig. 1, the deviations between the corrected orbit data and the uncorrected orbit data in the X, Y, and Z directions, as well as the deviations in clock bias data, all show a reduction. By statistically analyzing the root mean square (RMS) of orbit and clock bias deviations before and after correction over the two-hour period, the results are summarized in Table 1, which includes the RMS values of orbit and clock bias deviations for both pre-correction and post-correction scenarios. Table 1 and Fig. 1 collectively demonstrate that the PPP-B2b-corrected satellite orbit and clock bias data achieve higher accuracy compared to their uncorrected counterparts.

Multipath effect and observation quality evaluation

In the positioning of inspection drones in photovoltaic power plants, the multipath error in code pseudorange is often the primary source of positioning errors. By extracting the time series of pseudorange multipath errors through data processing methods combining code pseudorange and carrier phase observations, the temporal correlation characteristics of pseudorange multipath errors can be analyzed. The undifferenced observation equation formed by the receiver’s measurements is expressed as follows:

In the equation, \(dm_{pi}\) represents the multipath error term of the carrier signal with a center frequency of \(f_{i}\) ,\(B_{i}\) denotes its ambiguity parameter.

The difference between carrier phase observations at different frequencies can be expressed as follows:

Since the ionospheric delay terms corresponding to the carrier phase at center frequency \(f_{i}\) and center frequency \(f_{j}\) have the following relationship:

In summary, combining Eqs. (3)–(7), the extraction equation for the pseudorange multipath error corresponding to \(f_{i}\) can be derived as:

In the equation,P represents the code pseudorange observation, L denotes the carrier phase observation, the subscript i indicates different carrier frequencies, and \(\gamma =f_i^2/f_j^2\) represents the square ratio of the center frequencies corresponding to different carriers. Since multipath errors in the carrier phase can be neglected, the ambiguity-related term \(M_{b_i}\) , in the equation can be considered a constant in the absence of cycle slips. It can be approximated using a moving average approach. When cycle slips occur, the term needs to be re-estimated.

To obtain the pseudorange multipath error time series from long-term observation data, this study utilized observation data, precise ephemeris, and navigation message data from the JNFG station over seven days (Day of Year (DOY) 93 to 99) in 2024. Pseudorange multipath errors were extracted using a combination data processing method of code observations and carrier phase observations. Figure 2 presents the pseudorange multipath error time series extracted from the observation data of three selected BDS-3 satellites. Each subplot includes the corresponding pseudorange multipath error time series for the B1, B2b, and B3 frequency points.

Among them, Fig. 2 contains the time series of pseudorange multipath errors for three IGSO satellites over the 7-day period from day of year (DOY) 93 to 99. It is worth noting that C38, C39 and C40 respectively represent satellite numbers. In each subplot, the time series of pseudorange multipath errors corresponding to the B1, B3, and B2b frequency points are denoted by MP1, MP2, and MP3, respectively. In Fig. 2, the vertical axis represents the magnitude of pseudorange multipath error derived from observations between the satellite and receiver, while the horizontal axis indicates the day of year.

As shown in Fig. 2, the pseudorange multipath errors containing observation noise in the 7-day observation data collected by the JNFG station under the BDS system fluctuate within 2 meters and are predominantly concentrated around 20 cm. Analysis of the distribution of multipath error curves reveals that the pseudorange multipath error sequences exhibit a certain degree of periodicity.

To analyze the impact of pseudorange multipath errors on different frequency points, the average values of MP1, MP2, and MP3 pseudorange multipath errors during the 7-day period from day of year 93 to 99 were statistically calculated. As shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3 displays the daily average multipath errors extracted from observations of three satellites (PRN C38, C39, and C40) across different frequency bands during the observation period. As can be seen from Fig. 3, the influence of multipath errors varies among frequency bands. The multipath error sequences containing observation noise for MP1 are the smallest, while those for MP3 are the largest.

During the operation of the receiver, the quality of observations for the same satellite varies at different times, and in some cases observations may even be unavailable. Additionally, the receiver’s reception capability for different carrier signals of the same satellite also differs. To analyze the observation signal integrity across different frequency points within day of year (DOY), statistics were collected during the 7-day period from DOY 93 to 99 showing the ratio of the actual observed epoch counts to the expected observation epoch counts for each frequency point per DOY.

Figure 4 presents the statistics of observation signal integrity for different frequencies across each day of year (DOY). The figure reveals variations in data completeness among frequencies within the same DOY. Specifically, the B1 and B3 frequencies demonstrate relatively complete observational data, maintaining stable reception over extended periods. Analysis of pseudorange multipath errors and data quality from the JNFG station during DOY 93-99 shows that observation data from B1 and B3 frequencies exhibit superior quality with higher integrity. Experimental findings revealed a negative correlation between the carrier-to-noise ratio of observation signals and the pseudorange multipath errors in the data.

The quality of observation data is closely related to positioning accuracy. In addition to the influence of multipath errors, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the observed signals and the integrity of the received signals are particularly critical. The precision of observations is intricately linked to the SNR of the received signals the higher the SNR, the smaller the relative impact of noise. In numerous studies, the SNR parameter has also been adopted as a reference variable for quality control of observation data. Therefore, the SNR of the aforementioned observation data was extracted and analyzed. Figure 5 illustrates the SNR of carrier signals corresponding to the B1, B3, and B2b frequencies across different satellites during the observation epochs. Each subplot represents the SNR of different carrier signals for the same satellite.

Figure 5 shows the signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) of observation signals at different frequencies (B1, B3, B2b) for the same satellite during day of year (DOY) 93 to 99 in 2024, where SNR1, SNR2, and SNR3 correspond to the SNRs of B1, B3, and B2b signals, respectively. By comparing with Fig. 2, it can be observed that higher SNRs are associated with smaller pseudorange multipath errors containing observational noise, and vice versa. Therefore, the SNR of observation signals can serve as a criterion for data quality control. The above analysis demonstrates the relationship between the carrier-to-noise ratio (CNR) of observation signals and multipath errors. To further analyze the magnitude of CNRs for different frequencies of the same satellite, statistics were calculated for the average CNRs of observation signals on each day during the 7-day period from DOY 93 to 99, as shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6 illustrates the average carrier-to-noise ratio (CNR) of observation signals for different frequency points of the same satellite. In the legend, the MSNR1, MSNR2, and MSNR3 curves correspond to the average CNR values of the B1, B3, and B2b frequency points, respectively. It can be observed that the receiver’s signal acquisition capability varies across different frequency points during the observation period. The B1 and B3 frequency points exhibit higher CNR values, indicating relatively better observation quality.

Through the analysis of the measured data obtained from the JNFG station, this study evaluates the comprehensive multipath resistance performance of the B1, B3, and B2b frequency bands derived via data processing methods. The evaluation is based on the extracted pseudorange multipath error magnitudes, carrier signal-to-noise ratios (SNR), and data integrity metrics.

In summary, through the analysis of JNFG station’s measured data, it can be observed that among the three frequency points B1, B3, and B2b, the B2b frequency point is subject to the greatest influence from pseudorange multipath errors, followed by B3, with B1 experiencing the least impact. An analysis of the visibility of different frequency points within a single day revealed that the B1 and B3 frequency points exhibit better data integrity in their observation values, while the B2b frequency point demonstrates relatively poorer observability.

Additionally, Figs. 5 and 6 indicate that the SNR of B2b signals is slightly lower than that of B1 and B3. Overall, B1 and B3 signals demonstrate superior performance during the observation period. For UAV-based positioning in photovoltaic power station inspections, mitigating multipath errors and ensuring continuous, reliable positioning data are critical.

To validate the above findings and provide a basis for receiver selection, raw data from an OEM729 receiver were analyzed. A dataset collected on May 6, 2024, at 15:58 local time from the rooftop of Building A6 at Xihua University was used. Figure 7 shows the pseudorange multipath error sequences for different frequencies during this observation period.

Figure 7 shows the pseudorange multipath error sequences of the OEM729 receiver during the observation period, where MP1, MP2, and MP3 correspond to the multipath error sequences of the B1, B3, and B2b frequency points, respectively. The average values of MP1, MP2, and MP3 during the collection period were 0.171 m, 0.257 m, and 0.349 m, respectively. From the figure, it can be observed that the OEM729 receiver exhibits varying observation quality for different frequency points, which is generally consistent with the results obtained from the aforementioned experiments. This receiver demonstrates relatively better quality for observation data on B1 and B3 frequency points. Additionally, a comparative analysis of the carrier-to-noise ratios of observation signals across different frequency points during the collection period is shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8 displays the carrier-to-noise ratios (CNR) of signals at different frequency points observed by the OEM729 receiver during the collection period, where SNR1, SNR2, and SNR3 correspond to the CNR of the B1, B3, and B2b frequency points, respectively. The average CNR values for SNR1, SNR2, and SNR3 during the collection period were 51.42 dB, 49.83 dB, and 49.23 dB, respectively. The data integrity for B1, B3, and B2b signals during this period was 0.984, 0.984, and 0.968, respectively. These results confirm that the observation quality of the B1 and B3 frequency points is superior to that of B2b. Therefore, in the ionosphere-free dual-frequency precise point positioning (PPP) solution process, the observations from the B1 and B3 signals are selected for computation.

Precise point positioning

In summary, this paper selects the observation values of B1 and B3 signals to participate in the precise point positioning (PPP) solution for inspection drones. Among these, the precise satellite orbit and clock offset data are obtained by combining PPP-B2b messages with broadcast ephemeris corrections. A data processing method utilizing the combination of pseudorange observations and carrier phase observations is employed to handle pseudorange multipath errors.

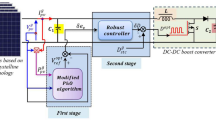

The PPP-B2b messages, broadcast ephemeris, pseudorange, and carrier-phase observations were acquired using an OEM729 receiver. A GPS1000 high-precision antenna was used for signal reception, which supports full-frequency GNSS signals across four systems (GPS, BDS, Galileo, GLONASS) and provides high measurement accuracy. Figure 9 shows the deployment environment of the external measurement antenna.

The collected data was imported into MATLAB for analysis to evaluate the precision of Precise Point Positioning (PPP) before and after pseudorange multipath error processing.

Under static conditions, error analysis was performed on the acquired static data points, yielding the static errors of the receiver in the East (E), North (N), and Up (U) directions, as shown in Fig. 10. Notably, this study adopts the positional information from the PPP mode of the OEM729 receiver as the reference position.

Figure 10 compares static PPP accuracy in E, N, and U directions before and after multipath correction. Subplots (a), (b), and (c) correspond to E, N, and U deviations, respectively. Following BeiDou’s official accuracy assessment method, RMS values for static positioning errors were computed. Before correction, RMS values were 0.319 m (E), 0.321 m (N), and 0.535 m (U); after correction, they improved to 0.298 m (E), 0.288 m (N), and 0.471 m (U).

Under dynamic conditions, this study collects dynamic data by moving the receiving antenna of a mobile receiver. Through error analysis of the collected dynamic data points, the dynamic errors of the receiver in the East (E), North (N), and Up (U) directions are obtained, as illustrated in Fig. 11.

Subfigures a, b, and c in Fig. 11 represent the dynamic deviations of the receiver in the E, N, and U directions, respectively. This study statistically analyzed the Root Mean Square (RMS) values of dynamic deviations during kinematic positioning in these three directions. The results show that before pseudorange multipath error correction, the RMS values of dynamic deviations for precise point positioning (PPP) were 0.550 m, 0.537 m, and 0.653 m in the E, N, and U directions, respectively. After implementing pseudorange multipath error correction, the corresponding RMS values improved to 0.496 m, 0.483 m, and 0.585 m in the E, N, and U directions.

According to the positioning accuracy evaluation methodology officially released by BDS (BeiDou Navigation Satellite System), this paper statistically analyzes the Root Mean Square (RMS) of positioning deviations for both static and dynamic positioning to evaluate the positioning accuracy before and after correction. The statistical results are presented in Table 3.

As illustrated in Figs. 10 and 11 and Table 3, the data processing method utilizing linear combinations of multi-frequency pseudorange and carrier phase observations effectively mitigates pseudorange multipath errors. For static positioning, the precise point positioning accuracy after multipath error correction shows improvements of 6.58%, 10.28%, and 11.96% in the E, N, and U directions respectively. In dynamic positioning scenarios, the corresponding improvements reach 9.82%, 10.06%, and 10.41% in the three orthogonal directions. To validate the algorithm’s applicability in the specified operational scenario, we implemented the algorithm on a hardware test platform integrated with an inspection drone. During routine inspection missions, the platform calculates receiver position information and transmits it back to the control room via LoRa modules. The drone’s trajectory is monitored through a host computer interface, with historical data stored for positioning accuracy analysis. The hardware platform configuration and testing environment are depicted in Figure 12.

Figure 13 shows the operating trajectory of the inspection unmanned aerial vehicle. To meet the data interface of Baidu Open Maps (https://lbsyun.baidu.com), the parsed location information is converted to latitude and longitude coordinates.

During the single-station positioning test of the inspection UAV, historical data samples were selected for positioning accuracy analysis. The average standard deviations of precise point positioning were measured at 0.545 m, 0.504 m, and 0.672 m in longitude, latitude, and elevation directions, respectively. Field tests conducted in photovoltaic array environments demonstrated that the method utilizing PPP-B2b correction messages to acquire satellite position and clock offset information exhibits reliable performance with good continuity. Experimental results confirm that both the improved parameter estimation methodology and multipath error suppression techniques have effectively enhanced the positioning accuracy of receivers in both static and kinematic scenarios to a significant extent.

Conclusion

Post-correction with PPP-B2b significantly improved satellite orbit and clock offset accuracy compared to pre-correction. This method achieves high-precision standalone positioning without relying on communication networks, making it suitable for remote areas with poor connectivity. In photovoltaic power plant environments, the multipath error of carrier signals significantly affects positioning accuracy. This paper evaluates the performance of different carrier frequencies. Finally, a comparative analysis of pseudorange multipath mitigation methods was performed using field measurement data. The results validate the effectiveness of this approach in photovoltaic power plant settings, demonstrating enhanced positioning accuracy for inspection UAVs.

Data availability

All data generated or presented in this study are available upon request from corresponding author. The dataset and code cannot be shared due to specific reasons.

References

Li, X. et al. Visible defects detection based on UAV-based inspection in large-scale photovoltaic systems. IET Renew. Power Gener. 11, 1234–1244. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-rpg.2017.0001 (2017).

Addabbo, P., Angrisano, A., Bernardi, L., M. et al. A UAV infrared measurement approach for defect detection in photovoltaic plants. In IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace (MetroAeroSpace) 345–350. https://doi.org/10.1109/MetroAeroSpace.2017.7999594 (2017).

Mesas-Carrascosa, F. J. et al. The development of an open hardware and software system onboard unmanned aerial vehicles to monitor concentrated solar power plants. Sensors 17, 1329. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17061329 (2017).

Zhou, M., Lin, J., Liang, S. et al. A UAV patrol system based on bluetooth localization. In 2017 2nd Asia-Pacific Conference on Intelligent Robot Systems (ACIRS) 205–209. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACIRS.2017.7986094 (2017).

Zhai, Y. et al. Design of electric patrol UAVs based on a dual antenna system. Energies 11, 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11040866 (2018).

Lee, D. & Park, J. Developing inspection methodology of solar energy plants by thermal infrared sensor on board unmanned aerial vehicles. Energies 12, 2928. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12152928 (2019).

Zhou, J., He, L. & Luo, H. Real-time positioning method for UAVs in complex structural health monitoring scenarios. Drones 7, 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones7030212 (2023).

Zumberge, J. et al. Precise point positioning for the efficient and robust analysis of GPS data from large networks. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 102, 5005–5017. https://doi.org/10.1029/96JB03860 (1997).

Wang, L. et al. Real-time GNSS precise point positioning for low-cost smart devices. GPS Solut. 25, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-021-01106-1 (2021).

Aggrey, J. et al. Multi-GNSS precise point positioning with next-generation smartphone measurements. J. Spat. Sci. 56, 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/14498596.2019.1664944 (2020).

Nie, Z. et al. Real-time precise point positioning with a low-cost dual-frequency GNSS device. GPS Solut. 24, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-019-0922-3 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Design and implementation of a BDS precise point positioning service. Navigation 67, 875–891. https://doi.org/10.1002/navi.392 (2020).

Carlin, L. & Hauschild, A. Precise point positioning with GPS and Galileo broadcast ephemerides. GPS Solut. 20, 77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-021-01111-4 (2021).

Ren, Z. et al. Performance assessment of real-time precise point positioning using BDS PPP-B2b service signal. Adv. Space Res. 68, 3242–3254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2021.06.006 (2021).

Geng, T. et al. Real-time ocean precise point positioning with BDS-3 service signal PPP-B2b. Measurement 203, 111911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111911 (2022).

Xu, Y., Yang, Y. & Li, J. Performance evaluation of BDS-3 PPP-B2b precise point positioning service. GPS Solut. 25, 142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-021-01175-2 (2021).

Lai, L. et al. PPP/INS tight integration with BDS-3 PPP-B2b service in the urban environment. Sensors 23, 2652. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23052652 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Real-time single-frequency precise point positioning using BDS-3 PPP-B2b corrections. Measurement 205, 112178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111911 (2022).

Funding

This research was supported by the Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Achievement Transfer and Transformation Project (2022ZHCG0099) and the Science and Technology Project (ZZ20250023) of Bazhong City, Sichuan Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L. was responsible for the simulation analysis of the algorithm and the deployment of the hardware platform, H.L. participated in the writing of part of the manuscript, Z.S. participated in the experimental testing, and X.W. participated in the guidance and topic planning of the whole project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., Xie, W., Hu, L. et al. Single-base station positioning for photovoltaic power plant inspection UAVs based on PPP-B2b signal. Sci Rep 15, 37373 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08834-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08834-1