Abstract

Epidemiological evidence on the association between Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) and lung cancer risk is limited. Meanwhile, whether inflammation can modify the association of GGT-lung cancer remains unknown. We assessed the relationship of GGT-lung cancer and modification effects of inflammation biomarkers in 412,634 participants from UK Biobank using Cox models and interactive analysis. This study founds participants in the top quartile of GGT level had an increased risk of lung cancer by 45.1% (HR, 1.451; 95% CI, 1.299–1.621; p < 0.001) compared to those in the bottom quartile. Positive associations were also observed between inflammation biomarkers (lymphocyte, neutrophil, platelet, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, systemic immune-inflammation index, white blood cell [WBC], C-reactive protein [CRP]) and lung cancer risk. Meanwhile, we observed the WBC and CRP served varying modification effects on the GGT-lung cancer associations (pinteraction <0.01). As WBC level increased, the HR of GGT for lung cancer tended to increase and then decrease. However, with an increase in CRP, the HR for GGT-lung cancer significantly declined. Circulating GGT is positively associated with lung cancer. Inflammation biomarkers have mixed modification effects on the association between GGT and lung cancer. Attention should be paid to the prediction of lung cancer by WBC and CRP combined with GGT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) is an ectoenzyme widely distributed on cell membranes in human tissues1. Elevated serum GGT is known as a reliable marker of not only liver damage caused by alcohol2 but also various chronic diseases including hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, renal failure and metabolic syndrome3,4,5. Previous studies evaluated elevated serum GGT can result from oxidative stress6 which could be as a useful risk indicator of cancer7. Several epidemiological studies have found the association between elevated serum GGT and cancer incidence of respiratory system, digestive organs, genital and urinary organs, etc8,9,10. To our knowledge, only a few studies have evaluated the relationship of serum GGT and lung cancer incident, and those study results are discordant8,11,12,13. Date of data from the Korean Cancer Prevention Study showed that there was no significant relationship between serum GGT and lung cancer risk in women8; however, in an Austrian cohort study, elevated serum GGT level was positively associated with respiratory organ cancer11,12. Thus, it is necessary to further explore the association of serum GGT level with lung cancer risk using large cohort study data to provide more valuable information for predicting lung cancer.

Inflammation may play important roles in the incident, tumour stage, and progression of cancer14,15,16. For instance, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes act as important indicators for cancer patient stage and grade17; elevated systemic inflammation responses serve as important biomarkers of cancer progression and prognosis18; elevated low-grade chronic inflammation prior to cancer diagnosis may be promote cancer incident19. Most previous studies play systemic inflammation biomarkers as prognostic indicators, and then less so as predictors indicators of cancer20,21. Several systemic inflammation biomarkers have been validated as predictors of lung cancer incident including lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), systemic immune-inflammation index(SII), white blood cell count (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP)22,23 but whether other inflammation biomarkers are effective is unknown, such as platelet count.

GGT as a marker of oxidative stress and systemic inflammation biomarkers may be risk factors for lung cancer incident. Previous experimental studies have identified that oxidative stress, inflammation, and lung cancer are closely related24. Inflammation could damage directly DNA causing oxidative stress, meanwhile, oxidative stress could stimulate a variety of inflammatory factor such as nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), tumor-suppressor gene p53, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma(PPAR-γ), etc. in the initiation and promotion of lung cancer25,26. Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that systemic inflammation biomarkers might modulate the association between GGT and lung cancer incident; however, data from large epidemiological cohort studies have not been collected until now.

In this study, we first evaluated the relationships between GGT, systemic inflammation biomarkers and lung cancer incident in the UK Biobank. We then determine how different systemic inflammation biomarkers impact the association between GGT and incident lung cancer to better predict lung cancer.

Results

Characteristics of participants

In the present study, a total of 412,634 participants with the mean age of 56.30(standard deviation [SD]8.09) years were included. During a median follow-up of 12.45 years, 3,574 lung cancer events were observed in the study. Table 1 listed the baseline characteristics of the study participants according to category of serum GGT level. Compared with those in the bottom GGT quartile, participants in the top GGT quartile were elder, predominantly male, less likely to have a university degree, more likely to have a family history of lung cancer, had greater exposure to current smoking, had a higher BMI and Townsend Deprivation index. In addition, participants in the top GGT quartile had higher circulating concentrations of lymphocyte, neutrophil, NLR, SII, WBC, CRP, and were more likely to develop lung cancer, nevertheless had lower circulating concentrations of platelet, PLR.

Association between GGT and incident lung cancer

We estimated the associations between GGT and incident lung cancer in a crude model and two adjusted models using Cox proportional hazards models, GGT as continuous variable, dichotomous variable and quartile variable, those results are portrayed Table 2. When considering GGT level as a continuous variable, each 10 U/L increase in GGT level was associated with a 1.8% (HR, 1.018; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.013–1.023; p < 0.001) increase in incident lung cancer in the fully adjusted Model 2. When considering GGT level as a dichotomous variable, those with GGT>26.30 U/L had a higher HR for incident lung cancer (HR, 1.206; 95% CI, 1.121–1.297; p < 0.001) compared to participants with GGT ≤ 26.30 U/L in Model 2. When considering GGT level as a quartile variable, participants in the top quartile of GGT level had an increased risk of lung cancer by 45.1% (HR, 1.451; 95% CI, 1.299–1.621; p < 0.001) compared to those in the bottom quartile in Model 2.

Figure 1 displays restricted cubic spline regression analyses results. The association between GGT and incident lung cancer was demonstrated as an approximately nonlinear tendency (pnon−linearity <0.05). Above 26.30 U/L, the hazard ratios of incident lung cancer steadily increased with the increasing GGT level versus the reference group (GGT = 26.30 U/L) in Model 2.

We conducted subgroup analyses to explore the association between GGT and incident lung cancer. The results of the subgroup analysis showed heterogeneity in BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake frequency and liver disease status at the baseline, and the positive association between GGT and incident lung cancer was found only in BMI < 30 kg/m2, previous or current smoking groups, those with alcohol frequencies of daily, 3–4 times a week, occasional, or never, and those without any liver diseases at the baseline (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Restricted cubic spline regression for the association between serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, inflammation biomarkers and lung cancer. The solid line represents the estimated Hazard Ratio for lung cancer risk and the shaded areas represent 95%CI. Figure A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I respectively represent the associations between gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, platelet count, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, systemic immune-inflammation index, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein and lung cancer using the model 2 cubic spline regression analyses. Model 2: adjusted for age at recruitment, sex, education level, Townsend deprivation index, body mass index, smoking status, family history of lung cancer, alcohol intake frequency, liver disease status at the baseline. GGT gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, LC lymphocyte count, NC neutrophil count, PC platelet count, NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, PLR plate-let-to-lymphocyte ratio, SII systemic immune-inflammation index, WBC White blood cell count, CRP C-reactive protein.

Association between inflammation biomarkers and incident lung cancer

Table 3 displays the positive relationships between inflammation biomarkers and incident lung cancer, including lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, platelet count, NLR, SII, WBC, CRP, regardless of those inflammation biomarkers as continuous variable, dichotomous variable and quartile variable. When considering inflammation biomarkers as continuous variable, the higher inflammation biomarkers level were significantly associated with increased risk of lung cancer in Model 2 (lymphocyte count, HR, 1.065; 95% CI, 1.050–1.082, per 10^9/L; neutrophil count, HR, 1.169; 95% CI, 1.148–1.190, per 10^9/L; platelet count, HR, 1.002; 95% CI, 1.001–1.002, per 10^9/L; NLR, HR, 1.039; 95% CI, 1.030–1.047, per 1 unit; SII, HR, 1.017; 95% CI, 1.014–1.020, per 100 × 10^9/L; WBC, HR, 1.077; 95% CI, 1.070–1.084; CRP, HR, 1.331; 95% CI, 1.272–1.393, per 10 mg/L). When considering inflammation biomarkers as dichotomous variable, compared to lower group, the higher group had a higher risk of lung cancer in Model 2 (lymphocyte count, HR, 1.200; 95% CI, 1.119–1.287; neutrophil count, HR, 1.524; 95% CI, 1.416–1.639; platelet count, HR, 1.258; 95% CI, 1.176–1.346; NLR, HR, 1.203; 95% CI, 1.125–1.285; SII, HR, 1.259; 95% CI, 1.178–1.345; WBC, HR, 1.589; 95% CI, 1.475–1.713; CRP, HR, 1.623; 95% CI, 1.507–1.748). When considering inflammation biomarkers as quartile variable, participants in the top quartile of inflammation biomarkers level had an increased risk of lung cancer (lymphocyte count, HR, 1.364; 95% CI, 1.236–1.506; neutrophil count, HR, 1.854; 95% CI, 1.670–2.058; platelet count, HR, 1.373; 95% CI, 1.250–1.507; NLR, HR, 1.285; 95% CI, 1.168–1.413; SII, HR, 1.451; 95% CI, 1.323–1.592; WBC, HR, 1.953; 95% CI, 1.752–2.177; CRP, HR, 2.131; 95% CI, 1.909–2.379) compared to those in the bottom quartile in Model 2.

Restricted cubic spline regression analyses showed that the associations between inflammation biomarkers and incident lung cancer were presented as approximately nonlinear tendency (pnon−linearity <0.05). The hazard ratios of incident lung cancer steadily increased with the increasing inflammation biomarkers in certain levels, including lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, platelet count, NLR, PLR, SII, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein level (Fig. 1).

The modification effects of inflammation biomarkers for GGT-lung cancer associations

Figure 2 displays the GGT-lung cancer associations by quintiles of inflammation biomarkers. There were no significant modification effects of inflammation biomarkers for lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, platelet count, NLR, PLR and SII, but we observed the WBC and CRP could modify the GGT-lung cancer associations (pinteraction <0.01). For WBC, Levels 2 and 3 of white blood cell count amplified the positive associations between GGT and incident lung cancer, but Level 4 of WBC attenuated the association. The positive association between GGT and incident lung cancer in lymphocyte count and NLR were similar with those associations in WBC, even though the modification effects of lymphocyte count and NLR were non-significant. For CRP, high CRP levels seemed to significantly decrease the hazard ratios of lung cancer for GGT.

Associations between serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and lung cancer for stratified participants with different levels of inflammation biomarkers. Pinteraction indicates the P values of the modifier effects of inflammation biomarkers. At the horizontal coordinate, the values Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4 denote the quartile of inflammation biomarkers. Analyses were adjusted for adjusted for age at recruitment, sex, education level, Townsend deprivation index, body mass index, smoking status, family history of lung cancer, alcohol intake frequency, liver disease status at the baseline. LC lymphocyte count, NC neutrophil count, PC platelet count, NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, PLR platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, SII systemic immune-inflammation index, WBC White blood cell count, CRP C-reactive protein.

Sensitivity analysis

With sensitivity analysis, when removing participants who developed lung cancer within 2 years after entering the cohort, adjusting pack year of smoking to replace smoking status, and using a Fine and Gray competing-risks regression model, we found the consistent positive associations between GGT, inflammation biomarkers (lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, platelet count, NLR, SII, WBC, CRP) and lung cancer(Supplementary Table S1), and those modification effects of white blood cell count and CRP for GGT-lung cancer remained essentially unchanged (Supplementary Figure S2).

Discussion

Our study has examined comprehensively the association between serum GGT and lung cancer incident, and assessed systematically the modification impact of specific inflammation biomarkers on such associations. In this study, higher serum GGT level led to a greater risk of lung cancer. Further, we identified varying modification effects of specific inflammation biomarkers on the association between serum GGT and lung cancer incident, and found that increased moderate levels of WBC can intensify the positive association between GGT and lung cancer incident, while increased CRP can attenuate the adverse influence of GGT.

Previous researches results with association between serum GGT level and lung cancer incident based on other population have failed to reach consistent conclusions. In particular, whether there are gender disparities in the relationship between serum GGT and lung cancer incident is ambiguous. In Korean population, the multivariate HR was 1.05 (95%CI: 1.04–1.06 per GGT 1SD) in men and 0.92 (95%CI: 0.81–1.03, per GGT 1SD) in women8. In Austrian population, the multivariate HR was 2.2 (95%CI: 1.80–2.69, per GGT log-unit increase) in men11 and 1.004 (95%CI: 1.001–1.006, per GGT unit increase) in women12 supporting the concept that the relationship between serum GGT and lung cancer incident are not sex-dependent. In this study with 412, 944 European populations, our finding also supported that serum GGT was correlated with lung cancer incident in a sex-unaligned fashion according to subgroup analysis. The observed multivariate HR was 1.018(95%CI: 1.012–1.024, per GGT 10unit increase) in men and 1.019(95%CI: 1.010–1.029, per GGT 10unit increase) in women (Supplementary Fig. S1). To the best of our knowledge, few studies have conducted subgroup analysis to observe disparities in serum GGT levels on the risk of lung cancer across groups, such as age, BMI, education level, smoking status. Our subgroup analysis found that the prominent effect of GGT on lung cancer incident was observed in people with obesity, a higher or lower frequency of alcohol intake, previous or current smokers, and those without any liver diseases at the baseline (Supplementary Fig. S1). In other words, BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake frequency and liver diseases status at the baseline may impact the relationship between serum GGT level and lung cancer incident, requiring future in-depth epidemiological research.

Potential biological mechanisms could be explained for serum GGT’s detrimental effect on lung cancer. GGT is a biomarker of the ability to respond to oxidative stress and could be commonly used to evaluate individuals’ oxidative stress level27. Elevated GGT levels lead to damage to red blood cells, the release of harmful transition metals, and the activation of a chain pro-oxidation reaction2. In the presence of elevated oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced, which could lead to gene instability and further causes precancerous lesions28,29. To some extent the oxidative stress can support the adverse health effect of serum GGT to cancer of any kind, including lung cancer. Simultaneously, given that GGT is a marker of oxidative stress and is closely linked to systemic inflammation, and considering that inflammation plays a key role in lung cancer development, it may be biologically plausible that inflammatory biomarkers mediate the relationship between GGT and lung cancer. We had conducted mediation analyses, and the results showed that CRP, WBC, Platelet count, Neutrophill count, and Lymphocyte count had the mediating effect in the association between serum GGT and lung cancer (Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Figure S3). The proportions of the mediating effect were 15.70%, 6.92%, 2.10%, 8.57%, and 1.63%, respectively. The serum GGT may also increase the risk of lung cancer through inflammation. Nevertheless, no study has explored the mechanism of how levels of GGT increase are related to lung cancer. Whether there is any particularity in lung cancer caused by GGT is still unknown and ambiguous, it is necessary to implement experimental study to explore the mechanism of GGT and lung cancer.

We found that moderate level of WBC can intensify GGT’s negative impact on lung cancer, but high level of WBC can attenuate the adverse influence of GGT. It is well known that WBC plays an important role in immune defense. Previous evidence has demonstrated that WBC may cause oxidative stress during the immune response process though generating a large amount of ROS, such as superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals, and secreting cytokines, such as Interleukin (IL), Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α)24. Oxidative stress may be the principal cause of GGT-induced lung cancer, and the synergistic pro-oxidant effects of WBC and GGT might explain our observation that moderate level of WBC reinforced the pro-carcinogenic effects of GGT on lung cancer. Oxidative stress serves as a double-edged sword in the occurrence and development of tumors30. On the one hand, under a certain degree of oxidative stress, increased ROS may play pro-carcinogenic effects through various biological pathways such as promoting genomic instability and facilitating the metastasis of tumor cells31,32. In contrast, when ROS continuously accumulate in large amounts and exceed a certain threshold, they will play an anti-carcinogenic role through promoting the apoptosis of tumor cells, facilitating ferroptosis of tumor cells, and enhancing anti-carcinogenic immunity33,34. The anti-carcinogenic effect of high level of ROS levels may be explained to some extent that high level of WBC can attenuate the adverse influence of GGT. CRP is primarily an acute phase protein, which plays a role in inflammation and oxidative stress35. However, our observation surprising found that increased CRP attenuates GGT’s impact on lung cancer. Although the underlying mechanism is still unclear, it may be related to the anti-carcinogenic effect of high level of ROS levels caused from CRP.

This study had several strengths. First, this study was based on a dataset with a large sample size and a wide range of covariates, which guarantees the validity of the study results. Second, our study is the largest prospective study on this topic to date to explore the relationship between GGT, systemic inflammation biomarkers and lung cancer risk. Third, considering the influence of GGT and inflammation biomarkers together on lung cancer, we innovatively conducted interactive analysis and found that mixed modifying effects of different intensities and categories of inflammation biomarkers on the association between GGT and lung cancer. However, this study had some limitations. First, the confounding factors may not have been fully included, such as genetic information. Considering this problem, we also included an index of family history of lung cancer in the analysis, which may have served as a proxy for genetic information. Second, the GGT and inflammation biomarkers in the study were based on a single measurement, which may not reflect the actual individual change exposure; thus, repeated exposure measured data can be used for further evaluation in the future study.

This study suggests that circulating GGT is positively associated with lung cancer in the studied population. Inflammation biomarkers have mixed modification effects on the association between GGT and lung cancer. A moderate level of WBC can intensify GGT’s adverse impact on lung cancer, while increased CRP can attenuate the adverse influence of GGT. As WBC and CRP have different modification effects on GGT related lung cancer incidence, attention should be paid to the prediction of lung cancer by WBC and CRP combined with GGT. These results can provide important evidence to better predict lung cancer.

Materials and methods

Study participants

This study was based on the UK Biobank, which is a prospective cohort study enrolled more than 500,000 participants between 2006 and 2010. Previous studies have detailed the data collection methods of UK Biobank36. In brief, participants were enrolled from 22 assessment centers in UK England, Wales, and Scotland. At the baseline assessment center, participants completed a touchscreen questionnaire on enriched information, performed anthropometric measurements and provided biological samples for laboratory tests37. After the baseline survey, Cancer incidence and death were tracked through linking to national death and cancer registries in England, Wales, and Scotland. All participants provided informed consent, and the UK Biobank study was approved by the North West Multicenter Research Ethics Committee. All methods are carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

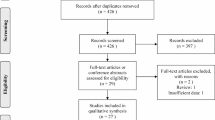

This study dataset included 502,411 participants. We excluded participants with prevalent cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) at baseline (n = 38,066), missing GGT and inflammation biomarkers (n = 37,470), and incomplete information covariate (n = 14,241),including Townsend deprivation (n = 581), education (n = 9,352), BMI (n = 2,385), smoking status (n = 1,581), alcohol intake frequency (n = 342). The final analysis included 412,634 individuals in the evaluation of the association between GGT, inflammation biomarkers and risk of lung cancer (Fig. 3).

Exposure assessment

Fasting blood samples were collected at baseline and immediately transported in dry ice and stored at −80℃. Cell counts were obtained by Beckman Coulter LH750 haematology analysers including lymphocyte, neutrophil, platelet, WBC. NLR and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) were calculated by dividing neutrophil and platelet counts by the lymphocyte counts, respectively. SII was calculated as the platelet counts multiplied by the NLR38. CRP and GGT level was examined using immune turbidimetric assay and enzymatic rate approach respectively on Beckman Coulter AU5800 analyzer. More information about assay performance is available online https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/ukb/refer.cgi?id=1227.

Outcome assessment

Cancer cases were identified by linking to national death and cancer registries in England, Wales, and Scotland. The outcome of this study was incident lung cancer (ICD-10 C33–C34). The endpoint was the first lung cancer diagnosis or primary underlying cause of death from lung cancer recorded on death certificates, whichever occurred first. All participants were followed up from the date of enrollment until the date of cancer diagnosis (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, ICD-10 C44), death, withdrawal from the UK Biobank cohort, or the last date of follow-up (September 30, 2021, for England and Wales, and October 31, 2021, for Scotland), whichever came first.

Statistical analysis

Cox proportional hazards models were applied to assess the effect of GGT on incident lung cancer in the three models. GGT was modeled on a continuous scale, two circulating levels (categorize by median) and also four circulating levels (categorize by quartile). Crude model was not adjusted for any covariates. Model 1 was adjusted for age at recruitment (< 60 and ≥ 60 years) and sex (male and female). Model 2 was additionally adjusted for education level (college degree, secondary education, some professional qualification and primary education or below), Townsend deprivation index (≤−2.17 and >−2.17, categorize by median), body mass index (BMI, < 25, 25-29.9, and ≥ 30 kg/m2), smoking status (never smoking, previous smoking, currently smoking), family history of lung cancer (yes and no), alcohol intake frequency(daily or almost daily, three or four times a week, once or twice a week, one to three times a month, special occasions only, never), liver disease status at the baseline(yes, no). Cox proportional hazard models also were applied to evaluate the effects of inflammation biomarkers (lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, platelet count, NLR, PLR, SII, white blood cell count, CRP) on incident lung cancer in this model 2. Subsequently, restricted cubic spline regression was carried out to evaluate the continuous change in hazard ratios for GGT and inflammation biomarkers on incident lung cancer in Model 2.

Furthermore, each potential effect modification of inflammation biomarkers on the association between GGT and incident lung cancer was evaluated using multiplicative interaction terms between GGT and inflammation biomarkers. We conducted the likelihood ratio statistic to test the statistical significance of each interaction terms. Then, we divided inflammation biomarkers into 4 levels based on the quartile range of inflammation biomarkers and assessed the associations between GGT and incident lung cancer by each inflammation biomarkers level.

We performed three sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of the study results. First, we additionally excluded participants who were diagnosed lung cancer cases within 2 years after entering the cohort to assess reverse causality. Second, we used pack year of smoking to replace smoking status (never smoking, previous smoking, currently smoking) to examine the stability of the models. Finally, a Fine and Gray competing-risks regression model was used with all-cause death treated as a competing risk.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.2.0) and SPSS 25.0, and a two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in UK Biobank, at https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 81434. The datasets analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Whitfield, J. B. Gamma Glutamyl transferase. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 38, 263–355 (2001).

Koenig, G., Seneff, S. & Gamma-Glutamyltransferase A Predictive Biomarker of Cellular Antioxidant Inadequacy and Disease Risk. Dis Markers 818570 (2015). (2015).

Lee, D. H. et al. Gamma-glutamyltransferase is a predictor of incident diabetes and hypertension: the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Clin. Chem. 49, 1358–1366 (2003).

Lee, D. S. et al. Gamma Glutamyl transferase and metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and mortality risk: the Framingham heart study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 27, 127–133 (2007).

Kasapoglu, B., Turkay, C., Bayram, Y. & Koca, C. Role of GGT in diagnosis of metabolic syndrome: a clinic-based cross-sectional survey. Indian J. Med. Res. 132, 56–61 (2010).

Marrocco, I., Altieri, F. & Peluso, I. Measurement and Clinical Significance of Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Humans. Oxid Med Cell Longev 6501046 (2017). (2017).

Reuter, S., Gupta, S. C., Chaturvedi, M. M. & Aggarwal, B. B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol. Med. 49, 1603–1616 (2010).

Mok, Y., Son, D. K., Yun, Y. D., Jee, S. H. & Samet, J. M. γ-Glutamyltransferase and cancer risk: the Korean cancer prevention study. Int. J. Cancer. 138, 311–319 (2016).

Kunutsor, S. K., Apekey, T. A., Van Hemelrijck, M., Calori, G. & Perseghin, G. Gamma glutamyltransferase, Alanine aminotransferase and risk of cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer. 136, 1162–1170 (2015).

Liao, W. et al. Circulating gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and risk of pancreatic cancer: A prospective cohort study in the UK biobank. Cancer Med. 12, 7877–7887 (2023).

Strasak, A. M. et al. Association of gamma-glutamyltransferase and risk of cancer incidence in men: a prospective study. Cancer Res. 68, 3970–3977 (2008).

Strasak, A. M. et al. Prospective study of the association of gamma-glutamyltransferase with cancer incidence in women. Int. J. Cancer. 123, 1902–1906 (2008).

Lee, Y. J., Han, K. D., Kim, D. H. & Lee, C. H. Determining the association between repeatedly elevated serum gamma-glutamyltransferase levels and risk of respiratory cancer: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Cancer Med. 10, 1366–1376 (2021).

Mantovani, A., Allavena, P., Sica, A. & Balkwill, F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 454, 436–444 (2008).

Diakos, C. I., Charles, K. A., McMillan, D. C. & Clarke, S. J. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 15, e493–503 (2014).

Grivennikov, S. I., Greten, F. R. & Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140, 883–899 (2010).

Zhang, D. et al. Scoring system for Tumor-Infiltrating lymphocytes and its prognostic value for gastric Cancer. Front. Immunol. 10, 71 (2019).

Dolan, R. D., McSorley, S. T., Horgan, P. G., Laird, B. & McMillan, D. C. The role of the systemic inflammatory response in predicting outcomes in patients with advanced inoperable cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 116, 134–146 (2017).

Colotta, F., Allavena, P., Sica, A., Garlanda, C. & Mantovani, A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis 30, 1073–1081 (2009).

Yang, R., Chang, Q., Meng, X., Gao, N. & Wang, W. Prognostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index in cancer: A meta-analysis. J. Cancer. 9, 3295–3302 (2018).

Abravan, A., Salem, A., Price, G., Faivre-Finn, C. & van Herk, M. Effect of systemic inflammation biomarkers on overall survival after lung cancer radiotherapy: a single-center large-cohort study. Acta Oncol. 61, 163–171 (2022).

Ji, M. et al. Circulating C-reactive protein increases lung cancer risk: results from a prospective cohort of UK biobank. Int. J. Cancer. 150, 47–55 (2022).

Nøst, T. H. et al. Systemic inflammation markers and cancer incidence in the UK biobank. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 36, 841–848 (2021).

Dharshini, L. C. P. et al. Regulatory components of oxidative stress and inflammation and their complex interplay in carcinogenesis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 195, 2893–2916 (2023).

Rahman, I. Oxidative stress, transcription factors and chromatin remodelling in lung inflammation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 64, 935–942 (2002).

Rahman, I. & MacNee, W. Role of transcription factors in inflammatory lung diseases. Thorax 53, 601–612 (1998).

Lee, D. H., Blomhoff, R. & Jacobs, D. R. Is serum gamma glutamyltransferase a marker of oxidative stress? Free Radic Res. 38, 535–539 (2004).

Hayes, J. D., Dinkova-Kostova, A. T. & Tew, K. D. Oxidative stress in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 38, 167–197 (2020).

Moloney, J. N. & Cotter, T. G. ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Semin Cell. Dev. Biol. 80, 50–64 (2018).

Kohan, R., Collin, A., Guizzardi, S., Tolosa de Talamoni, N. & Picotto, G. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: a paradox between pro- and anti-tumour activities. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 86, 1–13 (2020).

Srinivas, U. S., Tan, B. W. Q., Vellayappan, B. A. & Jeyasekharan, A. D. ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer. Redox Biol. 25, 101084 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. The double-edged roles of ROS in cancer prevention and therapy. Theranostics 11, 4839–4857 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Compound K induces apoptosis of bladder cancer T24 cells via reactive oxygen species-mediated p38 MAPK pathway. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 28, 607–614 (2013).

D, T. G, K. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 31, 107–125 (2021).

Cherny, S. S. et al. Characterizing CRP dynamics during acute infections. Infection (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-024-02422-7

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

Collins, R. What makes UK biobank special? Lancet 379, 1173–1174 (2012).

Xu, M. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index and incident cardiovascular diseases among middle-aged and elderly Chinese adults: the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort study. Atherosclerosis 323, 20–29 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted using the UK Biobank resource. The authors thank the investigators and participants involved in the UK Biobank for their contributions to this study.

Funding

This work was funded by Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (Chongqing Science and Technology Development Foundation) (No. CSTB2024NSCQ-KJFZMSX0027), Chongqing Medical Scientific Research Project (No. 2023MSXM064).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.JM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology. QZ: Data curation, Methodology, Software. LP: Software, Validation.LS: Validation. XZ: Visualization. YB: Visualization. XL: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. All author contributed to the study conception and design and approved its final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, T., Ma, J., Zhou, Q. et al. Circulating gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, systemic inflammation biomarkers and risk of lung cancer in the UK biobank prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 21935 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09196-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09196-4