Abstract

The house fly, Musca domestica, is a major mechanical vector of several pathogens, posing significant public health risks. Due to the hazards associated with indoor use of synthetic insecticides, biopesticides offer an eco-friendly alternative. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) flower bud extract contains bioactive insecticidal compounds; however, a comprehensive study of its sublethal effects on M. domestica, along with the associated molecular responses, was lacking. Ethanol-based clove extracts were characterized using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS). This study assessed the lethal and transgenerational effects of clove extract on two generations using age-stage, two-sex life table analysis. Gene expression analysis was conducted on three key stress-responsive genes (CYP12A2, CYP6D2, CYP6A24) and one fecundity-related gene, vitellogenin-I (Vg-I). GC-MS analysis identified eugenol (68.80%), caryophyllene (13.24%), and acetyl eugenol (13.56%) as the major constituents. The lethal concentrations were determined as LC5 = 0.405%, LC5 = 1.574%, and LC50 = 4.046%. The LC50 treatment significantly reduced longevity, fecundity, and survival. Mean generation time (T) was significantly shorter in the LC50 group (16.43 days) than in the control (19.89 days). Similarly, key population parameters—intrinsic rate of increase (r), finite rate of increase (λ), and net reproductive rate (R0)—were reduced. Gene expression studies revealed elevated stress responses and reproductive suppression. The detoxification genes (CYP12A2, CYP6D2, CYP6A24) were upregulated, while the fecundity-related gene Vg-I was downregulated. Molecular docking suggested strong binding affinity of caryophyllene to survival-related proteins. These findings suggest that clove extract significantly affects M. domestica, highlighting the potential of caryophyllene as an insecticidal compound.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The house fly, Musca domestica L. (Diptera: Muscidae), presents a significant challenge to both animals and public health, with a global distribution1. Adult flies are a nuisance and act as mechanical vectors for various pathogens, including bacteria such as Salmonella typhi, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli, as well as fungi, viruses, and other parasites that can cause human diseases2,3. House fly larvae can induce myiasis in humans, manifesting in cutaneous4, intestinal5, pelvic6, oral7, scalp8, and umbilical forms9.

House fly management strategies include cultural practices, chemical interventions, and biological approaches using microorganisms, predators, and parasitoids, or a combination of these methods10,11,12. However, reliance on chemical control is common, leading to insecticide resistance13,14. In Pakistan, agricultural practitioners often use residual insecticides from their farming activities to manage insect pests15. A wide variety of insecticides, both traditional and novel chemical compounds, have been employed to control house flies. Nevertheless, indiscriminate and injudicious use of insecticides has significantly contributed to resistance development in Pakistan16,17 and other countries18. The use of synthetic chemical insecticides is linked to global challenges, including environmental pollution, bioaccumulation of toxic residues, and public health concerns13. Consequently, researchers are exploring alternative methods, such as bioinsecticides. Various plant species have been used globally to control dipteran insects19.

Various plant extracts contain primary and secondary metabolites, which are essential for plant survival, particularly defence against environmental stress20. Clove, a common spice, is added to food for its strong aroma and antimicrobial properties21. Clove oil and clove powder, or their constituents, have repellent, toxic, and anesthetic properties against many urban pests, such as ants and cockroaches. However, integrating any biopesticide or its derivatives for targeting a specific insect pest requires a comprehensive study of its chemical composition, life table metrics, and potential effects on gene expression in the target species. There is a research gap concerning the sublethal effects of dried clove flower bud extracts on key biological parameters, including longevity, survival, reproduction, sex ratio, and developmental duration, as well as their influence on gene expression in domestic house flies22.

Preliminary molecular docking studies were conducted to identify potential interactions between clove constituents and insect molecular targets, which provided the basis for the selection of genes for expression analysis. Understanding changes in gene expression is crucial for elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying insect responses to botanical insecticides. Gene expression profiling can help reveal physiological stress, detoxification processes, and reproductive modulation, providing in-depth knowledge on sublethal and long-term effects. In this study, genes related to detoxification (CYP12A2, CYP6D2, CYP6A24) and reproduction (vitellogenin-I, Vg-I) were selected based on their known involvement in insecticide resistance and fecundity regulation23.

Considering the importance of house flies and clove, this study was designed to assess the sublethal effects of clove flower bud extract on house fly populations by examining various life table parameters using the age-stage, two-sex life table. The research also included chemical characterization of the clove flower bud using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), along with an analysis of the expression of various resistance- and fecundity-related genes.

Materials and methods

Insect rearing

Adult house flies were collected from poultry and meat shops using the methods described by Sinthusiri and Soonwera24. The collected specimens were reared in transparent cotton cages (30 × 30 × 30 cm) in the Insect Ecology Laboratory at MNS-University of Agriculture, Multan. The cages were maintained at a temperature of 30–35 °C and relative humidity of 70–80%. The flies were provided with a 10% sugar syrup solution absorbed in cotton wool, 30 g of powdered milk, and 300 g of mackerel fish placed on a sterile plastic tray (18 × 25 × 9 cm) filled with rice husks to support feeding and oviposition. House flies were reared for more than 10 generations before experiments were initiated.

Preparation of samples for gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)

Dried Syzygium aromaticum (clove) flower buds (250 g), purchased from a local market, were finely ground into a powder. Two grams of the powdered sample were subjected to ethanol extraction at room temperature for 24 h. The extracts were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 10 °C. The supernatants were filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and the solvents were concentrated using a rotary evaporator. The resulting organic residues were dissolved in 1 mL of methanol. The filtered solutions were transferred into dark amber vials using syringe filters for subsequent analysis25,26.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis

The GC-MS analysis was performed at the Analytical Lab, MNS-University of Agriculture, Multan, Pakistan, using an Agilent 8890 GC system integrated with a 5977B mass spectrometer. Chemical characterization was conducted using a DB5MS capillary column (30 × 0.25 mm ID × 1 μm film thickness). Helium (99.99%) was used as the carrier gas, maintained at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min. The injection volume was set to 0.5 µL, with an injector temperature of 250 °C. The oven temperature was programmed to increase from 100 °C to 200 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, followed by an increase to 280 °C at 5 °C/min, where it remained isothermal for 9 min. Mass spectra were collected at 70 eV with a scan interval of 0.5 s, spanning a mass-to-charge (m/z) range of 40–550. Compound were identified using the RTLPEST3 and NIST20 databases26,27.

Screening test

The acute toxicity of clove flower bud extracts against house flies was evaluated using the food-incorporated bioassay method described by Kristensen et al.28. The bioassay was conducted in 30 × 30 cm boxes with mesh-covered sides to ensure adequate airflow. Clove extracts were tested at concentrations ranging from 0 to 10%. A cotton plug soaked in a sugar solution containing the extract was provided as a feeding source. Each treatment consisted of 60 house flies, divided into three replicates of 10 individuals each, with equal numbers of males and females. Mortality was recorded 72 h post-treatment to determine LC5, LC25, and LC50 values29.

Transgenerational studies

Following the determination of LC5, LC25, and LC50 values, a cohort of 30 adult house flies was exposed to each respective concentration, along with an untreated control group according to the modified methodology of Iqbal et al.30. Forty-eight hours post-treatment, exposed adults were provided with larval medium to facilitate oviposition. Eggs laid by treated adults were randomly selected to assess transgenerational effects on population dynamics and demographic parameters. Daily observations were carried out on the F₁ generation to evaluate adult longevity and fecundity. Newly laid eggs were systematically counted until the death of the last adult in each treated group. Developmental progression, survival rates, and growth metrics from egg hatching to adult emergence were recorded. Observations continued daily until all individuals had died. The experiment was conducted under controlled environmental conditions (27 °C, 65–75% relative humidity, and a 12:12 h light: dark photoperiod). The resulting data were used to construct an age-stage, two-sex life table following the methodology of Shafi et al.23.

Gene expression analysis

For gene expression analysis, total RNA was extracted from exposed adult house flies and progeny of treated groups using TRIzol reagent. RNA integrity was assessed using a spectrophotometer (ACTGene) by measuring the A260/A280 ratio. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript® RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed on an ABI 7500 system (Applied Biosystems, USA) using gene-specific primers (0.5 µM), 10 µL of SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad, USA), and nuclease-free water, in a total reaction volume of 20 µL. The elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1α) gene was used as an internal reference for normalization. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Each RT-qPCR assay was conducted with three biological replicates and three technical replicates31.

Molecular docking of phytochemicals

Molecular docking studies were performed using PyRx, PyMOL, and Discovery Studio Visualiser to examine ligand-target protein interactions. Protein and ligand structures were prepared first. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) or AlphaFold (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk) provided three-dimensional structures of Cytochrome P450, Ecdysone 20-monooxygenase isoform X1, Muscle calcium channel subunit alpha-1, Odorant-binding protein 2, Gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit beta, Vitellogenin domain-containing protein, and Gustatory receptor. Ligand structures from chemical databases or ChemDraw were translated into docking forms. Structural optimisation required protein and ligand energy minimisation. PyRx used AutoDock Vina for virtual screening32,33,34,35. The active sites of each protein were used to generate grid box dimensions for appropriate ligand placement. Lower binding energy levels indicate stronger interactions. Post-docking analysis of ligand–protein complexes was done with PyMOL and Discovery Studio Visualiser. These methods identified stabilising interactions such hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, and electrostatic forces using 3D and 2D visualisations. We compared docking data across all targets and analysed complexes with the highest binding affinities to find the best ligand–protein interactions. This integrative strategy illuminated insecticidal possibilities and directed experimental validation36.

Statistical analysis

Life table parameters like developmental duration of immature stages, survival rates, pre-oviposition, oviposition, post-oviposition periods, adult longevity, intrinsic rate of increase (r), finite rate of increase (λ), and the mean generation time (T) etc. were analyzed using age-stage, two-sex life table methodologies36,37,38,39,40,41. Population parameters such as total pre-oviposition period (TPOP), adult pre-oviposition period (APOP), fecundity, and longevity were calculated using TWO-SEX-MSChart software. Variance and standard errors of life table parameters were estimated using the bootstrap method, with 100,000 bootstrap replicates for accuracy40. Gene expression levels were quantified using the 2-∆∆Ct method42, and statistical analysis was performed using a completely randomized design in Statistix 8.1.

Results

GC-MS results

The phytochemicals identified in the ethanolic extract of Syzygium aromaticum (clove) flower buds, along with their molecular weights, chemical formulas, percentage compositions, retention times, peak areas, and mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios, are presented in Table 2. The major compounds detected include: Eugenol (68.80%), 3-Allyl-6-methoxyphenol (Chavibetol) (68.80%), Caryophyllene (13.24%), Phenol, 2-methoxy-4-(2-propenyl)-, acetate (Acetyleugenol) (13.56%), 3-Allyl-6-methoxyphenyl acetate (13.56%), and Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (3.10%). The dominant functional groups identified among these compounds were allylbenzenes, bicyclic hydrocarbons, benzoate esters, acetates, and phthalates. The observed m/z values ranged from 41.10 to 279.10.

Toxicity

The LC10, LC30, and LC50 values were calculated after 72 h of exposure to clove extracts against housefly. Lethal concentrations, i.e., LC5, LC25, and LC50, were determined as 0.405% (0.217–0.599%), 1.574% (1.204–1.984%), and 4.046% (3.128–5.781%), respectively (Table 3). Additionally, the slope of the dose-response curve was 1.64 ± 0.22 (Chi-square = 5.416, DF = 13).

Survival and fecundity of parental generation

The higher survival rate in males was found in control population as compared to the rest of treatments. While, survival rate of female adults was similar in treated and as well as in control group. Overall male survival was higher as compared to female. Daily fecundity was lower in LC50 treated population. Contrarily, more numbers of eggs were found in the control parents as compared to other treatments (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Life table parameters

The life table parameters of the progeny of house fly adults exposed to clove flower bud extract exhibited significant differences among treatments (Table 4). The shortest pre-adult duration was observed in the LC50 group (11.65 ± 0.23 days), whereas the control group showed a significantly longer developmental period (21.08 ± 0.15 days). Female longevity was significantly reduced in the LC50 group (20.29 ± 0.57 days) compared to the control (26.36 ± 0.56 days). Similarly, male longevity decreased in LC50 (18.85 ± 0.35 days) relative to the control (28.90 ± 0.45 days).

The adult pre-oviposition period (APOP) did not differ significantly across treatments, ranging from 0.91 to 1.23 days. However, the total pre-oviposition period (TPOP) was significantly shorter in LC50 (13.35 ± 0.38 days) than in the control group (15.93 ± 0.36 days). Oviposition duration was also significantly reduced in all treatment groups, with the shortest period recorded in LC50 (6.23 ± 0.45 days) and the longest in the control (8.13 ± 0.47 days). Fecundity was significantly affected by clove extract exposure; females in the LC50 group laid less number of eggs (34.05 ± 2.36), while the highest fecundity was observed in the control group (62.14 ± 3.48 eggs per female).

Significant differences were also observed in population parameters (Table 4). The intrinsic rate of increase (r) was significantly lower in LC50 progeny (0.13 ± 0.01 per day) compared to the control (0.16 ± 0.01 per day). Likewise, the net reproductive rate (R0) was reduced in LC50 (10.52 ± 2.24) versus the control (24.85 ± 4.32). The mean generation time (T) was shortest in LC50 (16.43 ± 0.39 days), while it was significantly longer in the control (19.89 ± 0.42 days). The finite rate of increase (λ) was also significantly lower in LC50 (1.14 ± 0.01 per day) compared to the control (1.17 ± 0.01 per day).

Age-specific maternity (l x m x)

Age-specific maternity (lxmx) was derived from age-specific survival rate (lx) and age-specific fecundity (mx) as shown in Fig. 1. Relatively lower peaks for all the three values were observed in the LC30 treatment. The age-stage specific survival (lx) reached 0 in the control on day 33. Similarly, the peak value of age-stage specific fecundity (fx) in the LC50 treatment was found on day 20 and 21, with 6.77 offsprings per day. Similarly, the value of peak age-specific fecundity (mx) was 2.71 in control on day 20. The peak age-specific maternity (lxmx= 2.07) in control was found on day 20. In comparison, lower values for age-specific survival rate, age-stage specific fecundity, and age-specific maternity were observed in LC50.

Effect on gene expression and molecular docking

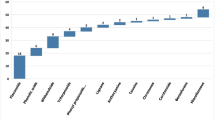

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis revealed significant alterations in the expression of detoxification and reproductive genes in M. domestica exposed to clove flower bud extract (Fig. 2). In the treated parental generation (F0), the relative expression of CYP12A2 increased significantly to 3.06-fold compared to the control (set at 1). Similarly, CYP6D2 and CYP6A24 were upregulated to 1.10-fold and 2.20-fold, respectively. In contrast, vitellogenin expression was markedly downregulated to 0.54-fold. In the F₁ progeny, CYP12A2 expression further increased to 3.37-fold, while CYP6D2 and CYP6A24 were upregulated to 1.36-fold and 2.38-fold, respectively. Vitellogenin-I expression remained suppressed at 0.68-fold.

Relative expression levels of 3 P450 genes (CYP12A2, CYP6D2, and CYP6A24) and one vitellogenin-I gene in F0 and F1 generation Musca domestica descending from the parent (F0) after 72 h exposure to LC50 of clove flower buds extracts. The relative expression level is expressed as the mean ± SE with the control as the calibrator. Different letters above the error bars indicate significant differences at P < 0.05 level (one-way ANOVA followed by LSD post hoc tests).

Molecular docking analysis demonstrated that caryophyllene exhibited the strongest binding affinity with several key insect proteins. Caryophyllene interacted with the hydrophobic transmembrane domains of the GABA receptor, involving residues such as valine, leucine, and isoleucine, and potentially formed hydrogen bonds with polar residues like serine or threonine. It showed the strongest binding with the gustatory receptor (-9.0 kcal/mol), followed by 3-allyl-6-methoxyphenol (-6.3 kcal/mol) and eugenol (-5.7 kcal/mol) (Table 5). Against the muscle calcium channel subunit alpha-1, caryophyllene also demonstrated the highest affinity (-7.4 kcal/mol), followed by 3-allyl-6-methoxyphenol (-6.1 kcal/mol) and eugenol (-5.6 kcal/mol), suggesting possible disruption of calcium signaling and neuromuscular function.

Caryophyllene also had the strongest affinity for the GABA receptor subunit beta (− 5.8 kcal/mol), as well as for the ecdysone 20-monooxygenase (− 7.1 kcal/mol), with both interactions involving hydrophobic contacts with non-polar residues (e.g., phenylalanine, leucine, valine) and hydrogen bonds with polar amino acids (e.g., serine, threonine, asparagine). Additionally, caryophyllene displayed a high binding affinity for cytochrome P450 enzymes (− 6.8 kcal/mol), with key van der Waals interactions involving aromatic residues like phenylalanine and tyrosine.

Among all ligands tested, caryophyllene consistently demonstrated the highest binding affinity to the vitellogenin domain-containing protein (− 7.4 kcal/mol), followed by 3-allyl-6-methoxyphenol (− 5.5 kcal/mol) and eugenol (− 5.6 kcal/mol). Binding was mediated through interactions with the lipid-binding domain, primarily involving non-polar residues (e.g., leucine, valine, isoleucine), as well as possible hydrogen bonding with polar residues like lysine or arginine (Tables 6 and 7). These findings suggest that caryophyllene may interfere with key physiological pathways, supporting its potential as a bio-insecticide.

Discussion

The ethanolic extract of clove flower buds was found to contain a diverse array of bioactive compounds, with eugenol being the most abundant constituent (68.80%), followed by acetyleugenol (13.56%) and caryophyllene (13.24%). The potent insecticidal effects observed against Musca domestica are likely attributable to this phytochemical diversity, consistent with previous reports highlighting the toxicity of plant-based compounds such as eugenol and caryophyllene toward insects43,44,45.

Houseflies exposed to LC50 concentrations of the extract exhibited significantly reduced survival and fecundity. These results align with earlier studies demonstrating that phytochemicals can interfere with oviposition and reproductive behavior in insects46,47. The strong molecular interactions of caryophyllene, particularly with vitellogenin-I and gustatory receptors, may impair reproductive physiology and disrupt feeding behavior, ultimately reducing fecundity and survival. This is supported by Darrag et al.48, who reported that interactions between caryophyllene and key survival- and reproduction-related proteins could lead to physiological disruptions and increased mortality.

The shortened pre-adult developmental duration (11.65 days in LC50-treated flies vs. 21.08 days in controls) suggests stress-induced change in developmental time, a phenomenon commonly associated with decreased longevity and fitness. Likewise, reductions in the total pre-oviposition period (TPOP) were observed in treated groups. These developmental disruptions may be attributed to the interference of clove phytochemicals with ecdysteroid biosynthesis, especially given caryophyllene’s strong binding affinity with ecdysone 20-monooxygenase. Similar developmental disturbances have been reported in other insect species treated with clove-derived compounds49.

Population parameters such as the intrinsic rate of increase (r = 0.13 per day), net reproductive rate (R₀ = 10.52 offspring per female), and mean generation time (T = 16.43 days) were significantly reduced in LC50-treated groups compared to the control. These results correspond with those of Shang et al.50, who reported eugenol-induced disruption of physiological processes in insect pests. Similarly, Leelaja et al.51 observed negative impacts on fecundity and survival following exposure to allyl acetate, another important component of clove extract. The observed reductions in reproductive output and survival may reflect an adaptive stress response to the toxic phytochemicals52,53.

Molecular analyses revealed that clove extract exposure significantly upregulated detoxification-related genes (CYP12A2, CYP6D2, CYP6A24) and downregulated vitellogenin, suggesting the activation of detoxification pathways and suppression of reproductive gene expression. The overexpression of cytochrome P450 genes reflects an enhanced metabolic response to chemical stress, consistent with known mechanisms of insecticide detoxification and resistance41,46. These molecular responses were supported by docking simulations, where caryophyllene demonstrated strong binding affinities to cytochrome P450 enzymes and the vitellogenin domain-containing protein. The interaction with vitellogenin’s lipid-binding domain may impair its function, resulting in suppressed expression and diminished reproductive capacity.

The physiological, molecular, and computational findings underscore the potential of clove flower bud extract as a promising biopesticide with eugenol and caryophyllene are major contributors towards its lethal and sublethal toxicity. Clove flower bud extracts are capable of inducing both lethal and sublethal effects in M. domestica through multiple mechanisms of action of its phytochemicals.

Conclusion

This study strongly suggests using clove flower bud extracts as a natural biopesticide against house flies. The extract exhibited both lethal and sublethal effects with eugenol being the major contributor. Exposure to LC50 concentrations significantly reduced survival, fecundity, longevity, and population growth indices in house flies, demonstrating a significant physiological influence on reproductive and developmental biology. In addition, qPCR analysis showed that cytochrome P450 genes were upregulated and vitellogenin was downregulated, indicating detoxification and reproductive suppression. Molecular docking showed significant binding affinities between caryophyllene and various important insect proteins, including vitellogenin, cytochrome P450 enzymes, and neurotransmitter-related receptors, suggesting plausible modes of action. These findings show that clove extract targets many biological processes in house flies, making it a sustainable, eco-friendly insecticide alternative. This research supports clove-based formulations in integrated pest control (IPM) programs due to synthetic pesticide resistance and environmental concerns. To maximise their use in pest management techniques, future studies should extract and test phytoconstituents, assess long-term field efficacy, and examine their compatibility with other biological control agents.

Data availability

The raw data of this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Nayduch, D., Neupane, S., Pickens, V., Purvis, T. & Olds, C. House flies are underappreciated yet important reservoirs and vectors of microbial threats to animal and human health. Microorganisms 11, 583 (2023).

Shahanaz, E. et al. Flies as vectors of foodborne pathogens through food animal production: factors affecting pathogen and antimicrobial resistance transmission. J. Food Prot. 100537 (2025).

Buyukyavuz, A. Filth Flies as a Vector for Some Pathogenic Bacteria Transfer. PhD dissertation (Clemson University,2023).

Alsaedi, O. K., Alqahtani, M. M. & Al-Mubarak, L. A. Wound myiasis by housefly in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 44, 940 (2023).

Kandi, V. et al. Persistent pediatric gastro-intestinal myiasis: a case report of fly larval infestation with Musca domestica with review of literature. J. Glob Infect. Dis. 5, 114–117 (2013).

Shaunik, A. Pelvic organ myiasis. Obstet. Gynecol. 107, 501–503 (2006).

Dogra, S. S. & Mahajan, V. K. Oral myiasis caused by Musca domestica larvae in a child. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 5, 105–107 (2010).

Rahman, A., Ishfaq, A., Arshad Azmi, M. & Khatoon, N. Cutaneous myiasis of scalp in a young girl related to Musca domestica. Dermatol. Online J. 21, 1–3 (2015).

Barolia, D. K., Singh, A. P., Tanger, R. & Gupta, A. K. Umbilical myiasis in a human neonate—treated with turpentine oil. J. Dr NTR Univ. Health Sci. 9, 143–145 (2020).

Senthoorraja, R., Senthamarai Selvan, P. & Basavarajappa, S. Eco-smart biorational approaches in housefly Musca domestica L. 1758 management. In New Future Dev. Biopesticide Research: Biotechnol. Exploration 281–303 (2022).

Ma, C. et al. Preparation and application of biocontrol formulation of housefly—Entomopathogenic fungus—Metarhizium brunneum. Vet. Sci. 12, 308 (2025).

Mohammed, A. A., Ahmed, F. A., Kadhim, J. H. & Salman, A. M. Susceptibility of adult and larval stages of housefly, Musca domestica to entomopathogenic fungal biopesticides. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 31, 1016–1026 (2021).

Naqqash, M. N., Gökçe, A., Bakhsh, A. & Salim, M. Insecticide resistance and its molecular basis in urban insect pests. Parasitol. Res. 115, 1363–1373 (2016).

Scott, J. G. Evolution of resistance to pyrethroid insecticides in Musca domestica. Pest Manag Sci. 73, 716–722 (2017).

Khan, H. A. A. et al. Comparative toxicity and resistance to insecticides in Musca domestica from some livestock farms of Punjab, Pakistan. Pak J. Zool. 54, 2315–2324 (2022).

Amjad, N. et al. Comparative toxicity and resistance to insecticides in Musca domestica from some livestock farms of Punjab, Pakistan. Pak J. Zool. 54, 2315–2324 (2022).

Khan, H. A. A. Monitoring resistance to methomyl and synergism in the non-target Musca domestica from cotton fields of Punjab and Sindh provinces, Pakistan. Sci. Rep. 13, 7074 (2023).

Hafez, A. M. Risk assessment of resistance to diflubenzuron in Musca domestica: realized heritability and cross-resistance to fourteen insecticides from different classes. PLoS ONE. 17, e0268261 (2022).

Pavela, R. Insecticidal properties of several essential oils on the house fly (Musca domestica L). Phytother Res. 22, 274–278 (2008).

Kafle, L. & Chinkangsadarn, S. Clove and its constituents against urban pests: examples from ants and cockroaches. In Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) 335–345 (Academic, 2022).

Ugbogu, O. C. et al. A review on the traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological activities of clove basil (Ocimum gratissimum L). Heliyon 7, e08327 (2021).

Yang, K. et al. Preparation and characterization of cinnamon essential oil nanocapsules and comparison of volatile components and antibacterial ability of cinnamon essential oil before and after encapsulation. Food Control. 123, 107783 (2021).

Shafi, M. S. et al. Cinnamon bark extracts alter the biological and molecular parameters of Bemisia tabaci gennadius. Microchem J. 209, 112748 (2025).

Sinthusiri, J. & Soonwera, M. Efficacy of herbal essential oils as insecticides against the house fly, Musca domestica L. Southeast. Asian J. Trop. Med. Public. Health. 44, 188–196 (2013).

Batool, N. et al. Toxicity and sublethal effect of chlorantraniliprole on multiple generations of Aedes aegypti L. (Diptera: Culicidae). Insects 15, 851 (2024).

Gökçe, A. et al. Contact and residual toxicities of 30 plant extracts to Colorado potato beetle larvae. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant. Prot. 40, 441–450 (2007).

Shilaluke, K. C. & Moteetee, A. N. Insecticidal activities and GC-MS analysis of the selected family members of Meliaceae used traditionally as insecticides. Plants 11, 3046 (2022).

Ukwubile, C. A. et al. GC-MS analysis of bioactive compounds from Melastomastrum capitatum (Vahl) fern. Leaf methanol extract: an anticancer plant. Sci. Afr. 3, e00059 (2019).

Kristensen, M., Jespersen, J. B. & Knorr, M. Cross-resistance potential of fipronil in Musca domestica. Pest Manag Sci. 60, 894–900 (2004).

Iqbal, N. et al. Transgenerational effects of pyriproxyfen in a field strain of Musca domestica L. (Diptera: Muscidae). PLoS ONE. 19, e0300922 (2024).

Zhong, M. et al. Selection of reference genes for quantitative gene expression studies in the house fly (Musca domestica L.) using reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 45, 1069–1073 (2013).

Wolf, L. K. Digital briefs: New software and websites for the chemical enterprise. C&EN 87, 32 (2009).

Shehata, A. Z. et al. Molecular docking and insecticidal activity of Pyrus communis L. extracts against disease vector, Musca domestica L. (Diptera: muscidae). Egypt. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 10, 800–811 (2023).

Ren, J. et al. Opal web services for biomedical applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W724–W731 (2010).

Suvannang, N., Nantasenamat, C., Isarankura-Na-Ayudhya, C. & Prachayasittikul, V. Molecular docking of aromatase inhibitors. Molecules 16, 3597–3617 (2011).

Chi, H. & Liu, H. Two new methods for the study of insect population ecology. Bull. Inst. Zool. Acad. Sin. 24, 225–240 (1985).

Chi, H. Life-table analysis incorporating both sexes and variable development rates among individuals. Environ. Entomol. 17, 26–34 (1988).

Chi, H. & Su, H. Y. Age-stage, two-sex life tables of Aphidius gifuensis (Ashmead) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) and its host Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae) with mathematical proof of the relationship between female fecundity and the net reproductive rate. Environ. Entomol. 35, 10–21 (2006).

Chi, H. TWOSEX-MSChart: a Computer Program for the age-stage, two-sex Life Table Analysis (National Chung Hsing University, 2020).

Tibshirani, R. J. & Efron, B. An Introduction To the Bootstrap (Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability, 1993).

Chi, H. et al. Age-stage, two-sex life table: an introduction to theory, data analysis, and application. Entomol. Gen. 40, 103–124 (2020).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Pereira, R. et al. Amino alcohols from Eugenol as potential semisynthetic insecticides: chemical, biological, and computational insights. Molecules 26, 6616 (2021).

Fernandes, M. et al. New Eugenol derivatives with enhanced insecticidal activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 9257 (2020).

Park, J. et al. Developmental toxicity of 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) and endosulfan sulfate derived from insecticidal active ingredients: abnormal heart formation by 3-PBA in zebrafish embryos. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 224, 112689 (2021).

Da Silva, R. et al. E)-Caryophyllene and α-Humulene: Aedes aegypti oviposition deterrents elucidated by gas chromatography-electrophysiological assay of Commiphora Leptophloeos leaf oil. PLoS ONE. 10, e0144586 (2015).

Nararak, J. et al. Excito-repellency and biological safety of β-caryophyllene oxide against Aedes albopictus and Anopheles Dirus (Diptera: Culicidae). Acta Trop. 210, 105556 (2020).

Darrag, H. M. et al. Molecular docking and insecticidal activity of caryophyllene oxide against Spodoptera littoralis (Boisduval). J. Pest Sci. 95, 789–800 (2022).

Rajendran, S. & Muralidharan, N. Effectiveness of allyl acetate as a fumigant against five stored grain beetle pests. Pest Manag Sci. 61, 97–101 (2005).

Shang, X. et al. A value-added application of Eugenol as acaricidal agent: the mechanism of action and the safety evaluation. J. Adv. Res. 34, 149–158 (2020).

Leelaja, B. C. et al. Enhanced fumigant toxicity of allyl acetate to stored-product beetles in the presence of carbon dioxide. J. Stored Prod. Res. 43, 45–48 (2007).

Kiran, S. & Prakash, B. Toxicity and biochemical efficacy of chemically characterized Rosmarinus officinalis essential oil against Sitophilus oryzae and Oryzaephilus surinamensis. Ind. Crops Prod. 74, 817–823 (2015).

Fernandes, M. et al. Liposomal formulations loaded with a eugenol derivative for application as insecticides: encapsulation studies and in Silico identification of protein targets. Nanomaterials 12, 3583 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciations to the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, grant number KFU252538 and the Research Development and Innovation Authority (RDIA) through grant number (12877-KFU-R-2-1-SE-).

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, grant number KFU252538 and the Research Development and Innovation Authority (RDIA) through grant number (12877-KFU-R-2-1-SE-).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, MAF and MNN; methodology, MNS, MF, and NB; software, MNN, MU and KMAR; validation, SAAH and MNS; formal analysis, MAF and MNN; investigation, MNN and AAA; funding acquisition, AAA and MNS; resources, MNS and MNN; data curation, NB and KMAR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MNN and MNS. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

All the authors have read the manuscript and approved its publication.

Declaration of of generative AI use

Generative AI-assisted tools were used in the writing process to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. However, authors carefully reviewed and edited the result after taking help from AI.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sattar, M.N., Naqqash, M.N., Batool, N. et al. Physiological and molecular responses of house fly (Musca domestica L.) to clove flower bud extracts. Sci Rep 15, 30856 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10857-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10857-7