Abstract

To investigate the respiratory and related health outcomes at 18 months for extremely preterm (EP) infants diagnosed with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). This retrospective cohort study aims to investigate the respiratory and related health outcomes at 18 months for extremely preterm (EP) infants diagnosed with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). Also, rephrase the second sentence to be: We reviewed post-hospital discharge outcomes for EP infants with BPD from Women’s Health and Research Centre, Doha, Qatar (January 2018 – December 2019). We compared 86 BPD infants with 102 preterm controls without BPD. EP infants with BPD were more often male (70% vs. 46%, p < 0.001), had lower birth weights (797 g vs. 920 g) and gestational ages (25.3 vs. 25.9 weeks, both p < 0.001). They required more surfactant, longer ventilation, and experienced higher rates of complications. Post-discharge, infants with BPD had significantly higher rates of oxygen dependence, steroid use (both systemic and inhaled), gastric tube feeding, and sleep study evaluations compared to those without BPD. Regression analysis revealed that moderate and severe BPD were significantly associated with increased risk of pediatric intensive care unit admissions, pulmonary hypertension, any patent ductus arteriosus closure procedure, and neurodevelopmental impairment. Specifically, severe BPD was strongly associated with home gastric tube feeding (OR 67.3; 95% CI: 6.48–699.67; p < 0.001), motor delays (OR 6.29; 95% CI: 1.61–24.54; p < 0.001), and expressive language delays (OR 4.39; 95% CI: 1.15–16.77; p = 0.031). BPD infants have significantly poorer respiratory and neurodevelopmental outcomes, highlighting the need for intensive monitoring and follow-up care. While this retrospective study provides valuable insights, further prospective research is warranted to validate these findings and explore targeted interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is the most common and severe chronic lung disease (CLD), primarily affecting extremely preterm (EP) infants (gestational age (GA) < 28 weeks)1. Definitions of BPD have shifted from histologic criteria to graded severity classifications aiming to standardise diagnosis and predict long-term outcomes (e.g., neurodevelopmental impairment, pulmonary hypertension)2,3,4,5,6,7. Emerging biomarkers (e.g., angiogenic factors, miRNA profiles) and computational models now seek to refine risk stratification8,9,10.

The aetiology of BPD is multifactorial, involving complex interactions between perinatal insults and postnatal exposures. Well-established risk factors and pathophysiological mechanisms include antenatal inflammation, postnatal ventilator-induced lung injury, and impaired alveolar-vascular development11,12,13,14. Emerging evidence highlights additional contributors such as necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) and sepsis, which may exacerbate BPD through systemic inflammatory cascades15,16. BPD imposes a substantial burden on parents and medical caregivers, as well as on healthcare systems, due to prolonged neonatal intensive care (NICU) stays, home oxygen dependence, and frequent rehospitalisations, demanding intensive medical follow-up and psychosocial support16,17,18,19.

BPD remains a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality in EP infants, with far-reaching consequences that include persistent respiratory compromise4,11,20,21,22,23. Due to its chronic nature and multifactorial pathogenesis, affected infants often experience both respiratory (e.g., recurrent infections, pulmonary hypertension) and extra-respiratory complications (e.g., growth failure, neurocognitive impairment) that necessitate coordinated multidisciplinary care extending well beyond infancy24,25,26. Respiratory morbidity is common in infants and young children born prematurely, especially those with BPD. Up to 50% of infants with BPD experience high readmission rates due to lower respiratory tract infections in the first year21,26. A recent study found nearly three-quarters of infants with severe BPD had multiple lung disease manifestations, pulmonary hypertension, and large airway disease14, including recurrent wheezing, hypoventilation, and hypoxemic episodes during sleep, which may be clinically silent22,23,27,28. Sleep hypoxemia is associated with poor growth in these infants, necessitating nighttime supplemental oxygen or pulse oximetry after discharge29,30. Oxygen supplementation helps decrease airway resistance and reverse pulmonary artery hypertension31,32. Home ventilation, often required in severe BPD cases, carries substantial mortality risks33. BPD is also linked to an elevated risk of neurodevelopmental disabilities, including cognitive impairments, cerebral palsy, and sensory deficits, compounding the health challenges faced by these infants. Given this substantial disease burden, the long-term respiratory and systemic health consequences of CLD in EP infants always require comprehensive evaluation, with consideration of healthcare system capacities and resource allocation, particularly as neonatal care practices continue to evolve7,18.

Despite improving neonatal care and survival of EP in Qatar, a comprehensive study exploring the post-discharge outcomes remains conspicuously absent. Therefore, this study aims to retrospectively investigate the health outcomes in a cohort of EP infants during the crucial post-discharge period till 18 months of age, addressing this knowledge gap.

Materials and methods

Study population and sampling strategy

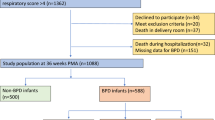

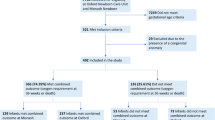

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Women’s Wellness and Research Centre (WWRC), Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) in Doha, Qatar. All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study included all preterm infants who were born less than 28 weeks’ gestation and admitted to the WWRC Hospital from January 2018 until December 2019, including the follow-up until 18 months of age. We identified a total of 230 infants. Of them, 188 were included in the analysis. We have excluded all infants who died before 36 weeks postmenstrual age (n = 40) and infants with congenital anomalies (n = 2). In our study, we consistently applied Jensen’s 2019 BPD classification for data analysis and infant grouping. We compared health outcome variables of infants with BPD to those without BPD from NICU discharge to 18 months of age shown in Fig. 1. BPD severity was classified according to the Jensen criteria, which stratify infants based on the mode of respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA into three grades: Mild (nasal cannula ≤ 2 L/min), Moderate (noninvasive support or nasal cannula > 2 L/min), and Severe (invasive mechanical ventilation)9.

Study variables

Data sets included basic demographic variables for all newborns (GA, BW, mode of delivery, and Apgar scores) and for mothers (age, parity, hypertension, and receipt of antenatal steroids). Health outcome variables encompassed types of respiratory support (invasive and non-invasive ventilation, continuous positive airway pressure, and high-flow oxygen therapy), respiratory infections, other chronic illnesses, short-term outcomes, discharge data, and long-term health outcomes including hospitalizations, emergency department visits, respiratory illnesses, hearing and visual complications, chronic medication use, growth assessments at 1 year and 18 months chronological age, specific disabilities, and death within the study period, degree of neurodevelopmental impairment. Neurodevelopmental assessments were conducted at 18–24 months of corrected age using the Bayley Infant Neurodevelopmental Screener (BINS III), a validated tool designed to identify infants at risk for developmental delays. BINS III evaluate cognitive, motor, and expressive/receptive language skills through structured tasks and caregiver-reported observations. Infants were categorised as follows based on standardised cutoff scores. Infants were categorised as low risk (scores within age expectations), moderate risk (1–2 SD below mean), or high risk (> 2 SD below mean/failed critical items) for neurodevelopmental delay, enabling identification of those needing early intervention.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to evaluate patient characteristics and clinical variables. Continuous variables were summarised as mean and standard deviation (SD) for parametric data, and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-parametric data. Comparisons of continuous variables were made using Student’s t-test for parametric distributions or the Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric distributions, as appropriate. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction was used to compare continuous outcomes among different BPD severity grades. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, and compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the association between BPD severity (mild, moderate and severe) and different post-discharge outcomes, using the “no BPD” group as the reference without assessing interaction effects. All p-values were two-tailed, and values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

The study encompassed a total of 188 infants who survived until 36 weeks PMA. Among the 188 infants, 86 had BPD, and 102 infants were categorised as the non-BPD group, as shown in Fig. 1.

The study examined the baseline neonatal and maternal clinical characteristics of infants with BPD compared to those without BPD. The results are summarised in Table 1. Infants with BPD had significantly lower BW (799.8 ± 143.2 g vs. 924.0 ± 193.2 g, p < 0.001) and lower GA at birth (25.6 ± 1.3 weeks vs. 27.1 ± 2.0 weeks, p < 0.001) compared to those without BPD. A higher proportion of males was observed in the BPD group compared to the non-BPD group (69.8% vs. 46.1%, p = 0.001). Additionally, infants with BPD were more likely to have an Apgar score of less than 7 at 1 min (80.2% vs. 63.7%, p = 0.013), require delivery room intubation (87.2% vs. 65.7%, p < 0.001), and received more surfactant (94.2% vs. 75.5%, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of multiple gestation, antenatal steroid administration, chorioamnionitis, preterm premature rupture of membranes, and vaginal delivery. In terms of outcomes, infants with BPD had a significantly higher body weight (3559.79 ± 1506.69 g vs. 2257.38 ± 453.20, p < 0.001) at discharge, and none were discharged before 36 weeks PMA compared to 41.2% of those without BPD (p < 0.001). Infants with BPD had significantly lower mean weight at 36 weeks’ PMA compared to those without BPD (1928.9 ± 345.8 g vs. 2174.8 ± 366.4 g, p < 0.001), and had a significantly higher rate of postnatal growth failure at 36 weeks PMA (81.4% vs. 57.8%, odds ratio 3.19, 95% CI 1.63–2.63, p < 0.001). The BPD group also had a higher proportion of NICU hospitalisation beyond 50 weeks (15.3% vs. 1.0%, p < 0.001) and a greater incidence of postnatal dexamethasone use (29.1% vs. 1.0%, p < 0.001). Additionally, infants with BPD required significantly more days of invasive ventilation (median 7.0 days [IQR 0.4–31.2]) compared to the no BPD group (median 0.4 days [IQR 0.0–3.0], p < 0.001).

The late respiratory outcomes of infants with BPD were assessed and compared between those with and without BPD, as detailed in Table 2. Notably, none of the infants without BPD required home oxygen, whereas 14.3% of infants with BPD did (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in the rates of respiratory illnesses requiring an emergency department visit between the BPD group (34.9%) and the non-BPD group (29.2%), p = 0.408. Similarly, hospitalisation due to respiratory illness occurred in 13.3% of BPD infants compared to 6.2% of non-BPD infants (p = 0.106). The incidence of respiratory viral illnesses occurring more than three times per year was higher among infants with BPD (10.8%) compared to non-BPD infants (1.1%), p = 0.021. Additionally, BPD infants were more likely to require pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission due to respiratory illness (12.7% vs. 1.1%, p = 0.002) and had a significantly higher incidence of pulmonary hypertension (14.0% vs. 1.0%, p < 0.001). The use of systemic steroids after discharge was significantly higher in the BPD group (32.5% vs. 8.2%, p < 0.001), as was the use of inhaled steroids (43.4% vs. 16.3%, p < 0.001). The need for bronchoscopy was observed only in the BPD group (4.7%, p = 0.042), and abnormal sleep studies were more common among BPD infants (12.8% vs. 0.0%, p < 0.001).

Late outcomes in infants with BPD were compared between those with and without BPD, as shown in Table 3. Late PDA device closure was more frequent in infants with BPD (4.7%) compared to those without BPD (1.0%), although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.180). The median day of life for closure was similar between groups (p = 1.000). Trends indicated a potential difference in the need for home care with nasogastric or gastrostomy tubes (1.1% in no BPD vs. 5.8% in BPD, p = 0.095), while rates of fundoplication were similar (1.1% in no BPD vs. 1.2% in BPD, p = 0.999). The analysis of neurodevelopmental outcomes reveals a significantly higher prevalence of any neurodevelopmental delay risk in BPD infants (57.0% vs. 29.4%, p < 0.001), with a higher risk of severe neurodevelopmental delay in BPD infants (p = 0.002). Motor delay was also significantly more prevalent in BPD infants (29.1% vs. 13.7%, p = 0.010). There were no statistically significant differences in cognitive delays (11.6% vs. 4.9%, p = 0.09), receptive language delays (20.9% vs. 12.7%, p = 0.132), or expressive language delays (36.0% vs. 25.5%, p = 0.117) between BPD and non-BPD infants. Notably, trends suggested potentially clinically meaningful differences, with the BPD group consistently showing higher rates of all measured delays despite lacking statistical significance. Furthermore, there were six cases of global developmental delay, defined as significant delay in two or more developmental domains: two cases occurred in infants with mild BPD, three in moderate BPD, and one in severe BPD. No cases of cerebral palsy were documented in the entire cohort. There were no statistically significant differences in mean body weight between Infants with BPD compared to those without BPD at both 1 year (8.33 ± 1.21 kg vs. 8.69 ± 1.37 kg, p = 0.075) and 18 months of age (10.06 ± 1.47 kg vs. 10.49 ± 1.48 kg, p = 0.059).

Univariate regression analyses were conducted to identify significant associations with outcomes related to different grades of BPD severity, as outlined in Table 4. The analysis focused on mild, moderate and severe BPD, using no BPD as the reference group. Inhaled corticosteroid use was significantly associated with all grades of BPD severity. Infants with moderate BPD had an OR of 3.316 (95% CI 1.554–7.077, p = 0.002) while those with severe BPD had an even higher OR of 7.687 (95% CI 1.946–30.371, p = 0.004). Systemic corticosteroid use was also notably higher in moderate BPD (OR 4.070, 95% CI 1.599–10.361, p = 0.003) and severe BPD (OR 16.687, 95% CI 3.886–71.668, p < 0.001). PICU admissions demonstrated significant associations in both moderate BPD (OR 13.404, 95% CI 1.601–112.207, p = 0.017) and severe BPD (OR 25.714, 95% CI 2.068–319.799, p = 0.012). Pulmonary hypertension was significantly associated with moderate BPD (OR 11.882, 95% CI 1.393–101.358, p = 0.024) and severe BPD (OR 151.500, 95% CI 14.580–1574.270, p < 0.001). Regarding neurodevelopmental outcomes, severe BPD was significantly associated with motor delay (OR 6.286, 95% CI 1.610–24.536, p = 0.008) and expressive delay (OR 4.385, 95% CI 1.147–16.766, p = 0.031). Additionally, the risk of any neurodevelopmental delay was significantly higher in severe BPD (OR 5.600, 95% CI 1.356–23.121, p = 0.0147). The need for home gastric tube feeding was significantly higher in severe BPD (OR 67.333, 95% CI 6.480–699.676, p < 0.001). Our findings indicate that motor delay was the primary contributor to this difference in the overall BPD vs. non-BPD comparison (Table 3). However, when analysing severe BPD cases separately (Table 4), expressive language delay also showed a significant association, suggesting it may further contribute to neurodevelopmental impairment in more severe BPD. Additionally, cognitive delay approached borderline significance (p ≈ 0.084), implying a potential role that might reach significance with a larger sample size. Based on this result, we believe motor and expressive contributed to the difference in BPD cases compared with no BPD. Our analysis assessed moderate-to-severe neurodevelopmental delay risk by including all qualifying cases across four domains: cognitive, motor, expressive language, and receptive language delays.

Table 5 presents the univariate analyses of other outcomes by BPD severity. Although not statistically significant, severe BPD was associated with higher odds of recurrent wheezing or cough (OR 3.62, p = 0.058) and bronchodilator use (OR 3.19, p = 0.088), suggesting a clinically meaningful trend that warrants further investigation. No significant associations between BPD severity and respiratory-related hospitalisations, emergency department visits for viral infections, vision or hearing impairments, or receptive language delays were observed.

The boxplots in Figs. 2 and 3, and 4 illustrate body weight measurements at different time points—36 weeks PMA, and 1- and 18-month chronological age—stratified by BPD severity. Figure 2 shows a significant difference in weight at 36 weeks PMA between infants with moderate BPD (1903 ± 347 g) and those with no BPD (2175 ± 366 g), with a mean difference of 275 g (95% CI: 113–249; p < 0.001). No other significant differences were observed among the remaining groups: mild BPD (1982 ± 301 g) and severe BPD (1979 ± 426 g). Figures 3 and 4 display body weights at 1 year and 18 months chronological age, respectively. Both show no significant differences in growth outcomes across BPD severity grades or when compared to non-BPD infants, suggesting that early growth impairments associated with BPD may be attenuated by 12 to 18 months of age.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study describes post-discharge respiratory and health-related outcomes in EP infants with BPD in Qatar, providing region-specific data and highlighting ongoing challenges faced by this vulnerable population up to 18 months corrected age. Our study encompassed 188 preterm infants, revealing that infants with BPD had significantly lower BW and GA compared to those without BPD. Additionally, these infants required more intensive respiratory support, including a higher incidence of delivery room intubation and surfactant administration. These early interventions reflect the severity of respiratory compromise in infants with BPD who required prolonged hospitalisation and postnatal steroid therapy. After discharge, infants with BPD exhibited significant respiratory and non-respiratory comorbidities, particularly among those with severe forms of BPD. This highlights the ongoing respiratory challenges faced by these infants, including the need for home oxygen therapy, a higher risk of experiencing more than three viral respiratory illnesses per year, and an increased likelihood of PICU admission among those with moderate to severe BPD.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes were also notably different between the groups. Infants with BPD had a significantly higher prevalence of motor delays and severe neurodevelopmental impairments. The neurodevelopmental delay (OR 5.6) observed in our cohort aligns with findings reported by Katz et al., for infants with severe BPD at two years of age34. Similarly, our observed association of BPD severity with expressive language delay closely reflects the previous association of expressive language deficits in infants with BPD between 8 and 18 months of age compared to controls of preterm and healthy term infants35. Additional risk factors such as male gender, low maternal education significantly affect the linguistic abilities of preterm infants with BPD36,37. These language deficits persist until preschool and even with correction of IQ scores, and were strongly associated with PDA present in infants with BPD37. In a recent study done by Lewis BA et al. evaluating speech and language outcomes of very low BW (VLBW) infants with and without BPD, children with BPD were found to have reduced articulation, receptive language skills, performance IQ, and overall gross and fine motor skills when compared to VLBW and term groups38. Motor delays were also described in earlier studies of preterm infants with BPD39,40. BPD severity is a robust and independent predictor of neurodevelopmental impairment, even after adjusting for GA and neonatal comorbidities9,34,41.

Preterm infants with BPD face increased neurodevelopmental risks due to combined inflammatory, metabolic, and hypoxic insults. Elevated cytokines and epigenetic changes sustain systemic inflammation that impairs brain development42,43,44, while loss of placental IGF-1 disrupts metabolic pathways crucial for microvascular growth45. MRI studies show BPD-associated reductions in white matter volume and impaired myelination46,47, exacerbated by hypoxia-induced oxidative damage to motor/language networks48. These processes, compounded by frequent feeding difficulties and growth restriction, explain BPD’s strong link to neurodevelopmental impairment regardless of overt brain injury49. These findings underscore the need for early neurodevelopmental screening for motor, cognitive, and language delays in infants with moderate to severe BPD, as recommended by recent guidelines34,41.

The univariate regression analyses further reinforced the association between BPD severity and adverse outcomes. Infants with moderate and severe BPD were more likely to require systemic and inhaled corticosteroids, have pulmonary hypertension, and face higher rates of PICU admissions. These findings are consistent with a body of research that indicates BPD manifests across a continuum of severity13,14,18,24,30,31,33,34,41,51. This gradation in disease severity is closely linked with an increased likelihood of significant negative outcomes, critical neonatal complications, more instances of mortality within the hospital, and a greater need for respiratory support upon discharge, particularly among infants with higher grades of BPD13,50,51,52. Our findings contribute to and reinforce the existing literature, highlighting the importance of adopting a severity-based approach to categorising BPD in the reporting of outcomes for EP infants.

Our results concur with other published evidence on the multifactorial nature of BPD, emphasising the long-term respiratory morbidities that persist beyond the neonatal period. Pulmonary hypertension complicates 17–24% of BPD cases53. According to a study from the Netherlands, the condition shows gradual resolution over time, with 47% of affected infants experiencing resolution by 1-year corrected age, nearly 80% by 2 years, and more than 90% resolving by 2.5 years54. Our results further complement the research by Htun et al., showing that the need for systemic and inhaled steroids post-discharge is significantly higher in this group, suggesting a more complex and prolonged recovery phase55.

The clinical implications of our findings are significant, indicating a need for heightened surveillance and potentially early intervention strategies for infants with moderate and severe BPD. Given the increased risk of developmental delays, routine neurodevelopmental screening might be warranted. Furthermore, the substantial use of home respiratory support raises questions about the adequacy of discharge planning and parental support systems. These results are particularly important for the Qatari population, as they highlight specific local healthcare needs and can inform targeted interventions.

Strengths and limitations

This study provides crucial insights into the postnatal outcomes of BPD in EP neonates—a particularly vulnerable population, especially among those who develop BPD. The findings shed light on post-discharge challenges that are relevant not only to neonatology but also to multiple other specialities involved in BPD management. This remains an important and evolving area of clinical and research interest. The study used regression analysis, which enabled us to explore various respiratory and health outcomes and their relation with BPD severity, thereby enhancing the study’s contribution to understanding this condition. These methodological considerations substantially augment the study’s integrity and the relevance of its findings within the field.

Despite its strength, this study contained limitations such as its retrospective design, which inherently restricts the ability to control for all potential confounding variables and limits causal inferences. The reliance on medical records may introduce information bias due to variability in documentation practices. Although Qatar has a unified medical record system, office visits to private paediatricians could be missed, potentially omitting relevant data. Our sample is also geographically confined to one medical centre, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings with different healthcare practices and resources. We also did not account for potential post-discharge environmental factors such as exposure to respiratory irritants or variability in care standards at home, which could significantly impact respiratory and developmental outcomes.

Our study focused on the association between BPD severity and post-discharge outcomes. We acknowledge that other perinatal factors, such as GA, BW, gender, duration of respiratory support, and postnatal steroid use, may also influence neurodevelopment. Future studies are needed to account for these factors and better define their independent contributions. There is also a need for research that explores the genetic and environmental contributors to BPD severity and the effectiveness of different post-discharge interventions. Investigations into the role of parental education and home care support may offer insights into strategies to improve outcomes for infants with moderate to severe BPD. Finally, given the association of BPD severity with developmental delays, interventional studies examining the timing and type of rehabilitative therapies could be beneficial in mitigating long-term impairments.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of this study reveal that infants with BPD experience more challenging health outcomes following their discharge from the hospital compared to those without BPD, with respiratory and developmental challenges being especially prevalent in moderate to severe cases. These findings stress the importance of diligent post-discharge care for these vulnerable infants. Enhanced follow-up care, including close monitoring and early intervention services, could be pivotal in improving the prognosis for infants with moderate to severe BPD.

Data availability

Original datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Data requests should be made to Dr Mohammad A. A. Bayoumi at moh.abdelwahab@hotmail.com and Dr Ashraf Gad at agad2@hamad.qa.

References

Mowitz, M. E. et al. Long-term burden of respiratory complications associated with extreme prematurity: an analysis of US medicaid claims. Pediatr. Neonatology. 63 (5), 503–511 (2022).

Jobe, A. H. & Bancalari, E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 163 (7), 1723–1729. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2003017 (2001).

Ryan, R. M., Ahmed, Q. & Lakshminrusimha, S. Inflammatory mediators in the immunobiology of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 34 (2), 174–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-007-8031-4 (2008).

Thébaud, B. et al. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 5 (1), 78. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0127-7 (2019).

Salimi, U., Dummula, K., Tucker, M. H., Dela Cruz, C. S. & Sampath, V. Postnatal sepsis and bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants: mechanistic insights into new BPD. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 66 (2), 137–145 (2022).

Yang, K., He, S. & Dong, W. Gut microbiota and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 56 (8), 2460–2470 (2021).

Stoll, B. J. et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993–2012. Jama 314 (10), 1039–1051 (2015).

Lagatta, J. et al. Identifying barriers and facilitators to care for infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia after NICU discharge: A prospective study of parents and clinical stakeholders. Res. Square. 9, rs–3 (2023).

Jensen, E. A. et al. The diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very preterm infants: an evidence-based approach. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 200 (6), 751–759. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201812-2348OC (2019).

Gad, A. et al. Perspectives and attitudes of pediatricians concerning post-discharge care practice of premature infants. J. neonatal-perinatal Med. 10 (1), 99–107 (2017).

Caskey, S. et al. Structural and functional lung impairment in adult survivors of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Annals Am. Thorac. Soc. 13 (8), 1262–1270 (2016).

Higgins, R. D. et al. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: executive summary of a workshop. J. Pediatr. 197, 300–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.043 (2018).

Jensen, E. A. et al. Severity of bronchopulmonary dysplasia among very preterm infants in the united States. Pediatrics 148 (1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-030007 (2021).

Wu, K. Y. et al. Characterization of disease phenotype in very preterm infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 201 (11), 1398–1405. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201911-2190OC (2020).

Keller, R. L. et al. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia and perinatal characteristics predict 1-year respiratory outcomes in newborns born at extremely low gestational age: a prospective cohort study. J. Pediatr. 187, 89–97 (2017).

Lal, C. V. et al. The airway Microbiome at birth. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 31023 (2016).

Lao, J. C. et al. Type 2 immune polarization is associated with cardiopulmonary disease in preterm infants. Sci. Transl. Med. 14 (639), eaaz8454 (2022).

Lagatta, J. M. et al. Prospective risk stratification identifies healthcare utilization associated with home oxygen therapy for infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J. Pediatr. 251, 105–112 (2022).

Laughon, M. M. et al. Prediction of bronchopulmonary dysplasia by postnatal age in extremely premature infants. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 183 (12), 1715–1722 (2011).

Walter, E. C. et al. Low birth weight and respiratory disease in adulthood: A population-based case-control study. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 180 (2), 176–180. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200811-1754OC (2009).

Bhandari, A. & Panitch, H. B. Pulmonary outcomes in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Perinatol. 30 (4), 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2006.05.004 (2006).

Doyle, L. W. et al. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very low birth weight subjects and lung function in late adolescence. Pediatrics 118 (1), 108. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-3111 (2006).

Palta, M. et al. Respiratory symptoms at age 8 years in a cohort of very low birth weight children. Am. J. Epidemiol. 154 (6), 521–529. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/154.6.521 (2001).

Sun, L. et al. Long-term outcomes of bronchopulmonary dysplasia under two different diagnostic criteria: A retrospective cohort study at a Chinese tertiary center. Front. Pediatr. 9, 648972. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.648972 (2021).

Bauer, S. E. et al. Factors associated with neurodevelopmental impairment in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J. Pediatr. 218, 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.01.008 (2020).

Doyle, L. W., Ford, G. W. & Davis, N. M. Health and hospitalisations after discharge in extremely low birth weight infants. Semin Neonatol. 8 (2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1084-2756(03)00006-7 (2003).

Sekar, K. C. & Duke, J. C. Sleep apnea and hypoxemia in recently weaned premature infants with and without bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 10 (2), 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.1950100208 (1991).

Zinman, R., Blanchard, P. W. & Vachon, F. Oxygen saturation during sleep in patients with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Biol. Neonate. 61 (2), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1159/000243853 (1992).

Balfour-Lynn, I. M. et al. BTS guidelines for home oxygen in children. Thorax 64 (2), https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.116020 (2009).

Tay-Uyboco, J. S. et al. Hypoxic airway constriction in infants of very low birth weight recovering from moderate to severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J. Pediatr. 115 (3), 456–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(89)80836-2 (1989).

Abman, S. H. et al. Pulmonary vascular response to oxygen in infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics 75 (1), 80–84. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.75.1.80 (1985).

Halliday, H. L., Dumpit, F. M. & Brady, J. P. Effects of inspired oxygen on echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary vascular resistance and myocardial contractility in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics 65 (3), 536–541. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.65.3.536 (1980).

Cristea, A. I. et al. Outcomes of children with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia who were ventilator dependent at home. Pediatrics 132 (4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0272 (2013).

Katz, T. A. et al. Severity of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 and 5 years corrected age. J. Pediatr. 243, 40 – 6.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.12.018 (2022).

Rvachew, S., Creighton, D., Feldman, N. & Sauve, R. Vocal development of infants with very low birth weight. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 19 (4), 275–294 (2005).

Sansavini, A. et al. Longitudinal trajectories of gestural and linguistic abilities in very preterm infants in the second year of life. Neuropsychologia 49 (13), 3677–3688 (2011).

Singer, L. T. et al. Preschool Language outcomes of children with history of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and very low birth weight. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 22 (1), 19–26 (2001).

Lewis, B. A. et al. Speech and Language outcomes of children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J. Commun. Disord. 35 (5), 393–406 (2002).

Shea, T. M. et al. Outcome at 4 to 5 years of age in children recovered from neonatal chronic lung disease. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 38 (9), 830–839 (1996).

Perlman, J. M. & Volpe, J. J. Movement disorder of premature infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a new syndrome. Pediatrics 84 (2), 215–218 (1989).

Schmidt, B. et al. Prediction of late death or disability at age 5 years using a count of 3 neonatal morbidities in very low birth weight infants. J. Pediatr. 167 (5), 982–6e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.07.067 (2015).

Ambalavanan, N. et al. Cytokines associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia or death in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 123 (4), 1132–1141 (2009).

Song, R. & Bhandari, V. Epigenetics and bronchopulmonary dysplasia: unraveling the complex interplay and potential therapeutic implications. Pediatr. Res. 96 (3), 567–568 (2024).

Balany, J. & Bhandari, V. Understanding the impact of infection, inflammation, and their persistence in the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Front. Med. 2, 90 (2015).

Kramer, B. W., Niklas, V. & Abman, S. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia and impaired neurodevelopment—What May be the missing link? Am. J. Perinatol. 39 (S 01), S14–S17 (2022).

Shimotsuma, T. et al. Severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia adversely affects brain growth in preterm infants. Neonatology 121 (6), 724–732 (2024).

Lee, J. M. et al. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia is associated with altered brain volumes and white matter microstructure in preterm infants. Neonatology 116 (2), 163–170 (2019).

Martin, R. J., Di Fiore, J. M. & Walsh, M. C. Hypoxic episodes in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Clin. Perinatol. 42 (4), 825 (2015).

Li, W. et al. Association between bronchopulmonary dysplasia and death or neurodevelopmental impairment at 3 years in preterm infants without severe brain injury. Front. Neurol. 14, 1292372 (2023).

Ehrenkranz, R. A. et al. National institutes of child health and human development neonatal research network. Validation of the National institutes of health consensus definition of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics 116 (6), 1353–1360. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0249 (2005).

Short, E. J. et al. Developmental sequelae in preterm infants having a diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: analysis using a severity-based classification system. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 161 (11), 1082–1087. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1082 (2007).

Brumbaugh, J. E. et al. Behavior profiles at 2 years for children born extremely preterm with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J. Pediatr. 219, 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.12.058 (2020).

Bui, C. B. et al. Pulmonary hypertension associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. J. Reprod. Immunol. 124, 21–29 (2017).

Arjaans, S. et al. Fate of pulmonary hypertension associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia beyond 36 weeks postmenstrual age. Archives Disease Childhood-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 106 (1), 45–50 (2021).

Htun, Z. T. et al. Postnatal steroid management in preterm infants with evolving bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J. Perinatol. 41 (8), 1783–1796. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01083-w (2021).

Funding

No sponsor or funder supported this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AG and RM contributed to manuscript writing and tabulations. AG additionally conceptualized the study and performed the statistical analysis. TM and MAAB drafted the protocol, obtained institutional approval and supervised the data collection process. TM, FA, NJ, MA, TA, MM, and MAA collected data. MAAB critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual clinical and methodological inputs and submitted the manuscript for publication. All authors, contributing to various capacities, critically reviewed the manuscript and collectively approved it for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statement of ethics

This study was approved and received ethical approval by the Medical Research Centre (MRC)/Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) under protocol number MRC-01-22-735. It was conducted following local legislation and institutional requirements. The study received no external funding, and informed consent was waived due to its retrospective nature. A waiver for the requirement of informed consent was granted by the Chair of the Medical Research Centre on the grounds of being a minimal risk study.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gad, A., Mesilhy, R., Maveli, T. et al. Outcomes of extremely preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 26651 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12066-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12066-8