Abstract

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has demonstrated efficacy in children and young adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). The purpose of our study was to investigate thymus size changes after CAR T-cell therapy, explore the associated clinical conditions, and assess survival differences of patients who underwent CAR T-cell therapy, we conducted a single-center retrospective study of children and young adult patients who underwent CAR T-cell therapy for ALL between April 2015 and October 2023.We measured the volume of the thymus on pre- and post-CAR T-cell chest CT scans of 20 patients (median [IQR] age, 18[11] years; 11 females). We divided patients into two groups, those who did (group 1) or did not (group 2) demonstrate increase in thymus size after therapy. Clinical and survival data were collected. We used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test or Fisher’s exact test for group comparisons and analyzed event-free survival data. Seven of 20 patients (35%, group 1) showed increase in thymus volume (pre- vs. post-CAR T-cell thymus volume; 5.01 [2.18] cm³ vs. 20.87 [19.86] cm³, p = 0.01), while 13 patients (65%, group 2) showed no increase in thymus volume (pre- vs. post-CAR T-cell thymus volume; 3.01 [13.42] cm³ vs. 2.09 [8.34] cm³, p = 0.01). Patients in group 1 were younger (12 [8] years vs. 19[10] years, p = 0.028) and showed a higher rate of event-free survival compared to those in group 2 (p = 0.003). In children and young adults with ALL, increased thymus size after CAR T-cell therapy was associated with younger age and improved clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common type of cancer among pediatric patients in the United States, representing approximately 25% of cancer diagnoses among children under 15 years old1,2. For children and young adults with refractory or relapsed B-cell ALL (r/r B-ALL), Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy demonstrated promising results with complete response rates of 65-90%3. However, despite early responses, only 50% achieve longitudinal event-free survival4. Additionally, CAR-mediated toxicities due to immune system activation have emerged, such as cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity, where respective rates of 77% and 40% were seen in the ELIANA registrational trial for tisagenlecleucel (FDA approved CD19-CAR for pediatric r/r B-ALL)5. Disparate response and toxicity outcomes can be explained by varying levels of host immune activation, ranging from insufficient6 to excessive immune responses.

The thymus is essential for a robust adaptive immune response through maturation of T-lymphocytes7. Mackall et al. reported that cyclophosphamide chemotherapy caused atrophy of the thymus and was associated with reduced quantities of naive T-cells in the peripheral blood in pediatric patients with ALL8. Williams et al. found that prolonged chemotherapy regimens led to decreased size and function of the thymus and persistently reduced numbers of T-cells and B-cells in the peripheral blood9. After completion of chemotherapy, the thymus and immune function in pediatric patients can regenerate10. These prior studies outlined a link between thymus volume and adaptive immune response in patients undergoing classical chemotherapy. However, the effect of CAR T-cell therapy in thymus size in children and young adults with ALL has not been investigated to date.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to investigate thymus size changes after CAR T-cell treatment protocol in children and young adults with ALL, explore the underlying reasons, and assess potential outcome of this phenomenon for patients following CAR T-cell therapy.

Materials and methods

Patients

This retrospective single-center study was conducted under the approval of the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (CCT5019). Although this was a retrospective study, all patients had previously provided written informed consent to participate in a prospective clinical trial of CD19 or CD19/22 CAR T-cell therapy and/or our institutional biorepository study, which included consent for the use of associated clinical and imaging data in future research. Therefore, no additional waiver of informed consent was required. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of ALL, receipt of CAR T-cell therapy, and availability of chest CT imaging both before and after CAR T-cell therapy. We excluded patients who had only one chest CT, either before or after therapy (Fig. 1).

The final patient population comprised 20 children and young adult patients, including 11 (55%) females and 9 (45%) males with an age of 4–25 years (median 17.5 years). Race and ethnicity are listed in Table 1.

In addition to the demographic information, we collected information about steroid therapy, methotrexate (MTX), history of HSCT and type of CAR T-cell therapy product (CD19/22, CD19, and CD22). We also recorded information about CRS grade, disease burden, CAR T-cell persistence, as well as absolute and relative counts of lymphocytes by flow cytometry, recent thymic emigrants (RTEs) by flow cytometry, blasts and lymphocytes by bone marrow biopsy (Appendix 1) and patient survival rate. Peripheral blood samples were collected at the same time as the chest CT scan. Lymphocyte percentage and absolute lymphocyte counts were determined from a complete blood count test. Absolute lymphocyte counts (cells/µL) were used as an indicator of early immune reconstitution. RTEs were identified as CD3⁺CD4⁺CD45RA⁺CD31⁺ T-cells using multicolor flow cytometry. RTEs were collected after CAR T-cell therapy at the first available timepoint. RTEs were reported as a percentage of total CD4⁺ T cells. Absolute RTE counts were calculated by multiplying RTE% by the absolute CD4⁺ T-cell count, derived from lymphocyte panel data.

All patients received CAR T-cell therapy as part of a multi-step treatment regimen that included lymphodepleting chemotherapy followed by CAR T-cell infusion. The lymphodepleting regimen consisted of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, administered 3–5 days before infusion, according to institutional protocols. CAR T-cells were infused on day 0. To assess the effect of this treatment protocol on thymus size, we recorded the dates of pre-CAR chest CTs relative to lymphodepleting chemotherapy and CAR T-cell infusion. Interval therapy (blinatumomab or inotuzumab), defined as additional treatment between CAR T-cell infusion and HSCT, was administered to 9 patients. The other 11 patients proceeded directly to CAR T-cell therapy without interval treatment. The timeline of the therapies and chest CTs are summarized in Fig. 2.

Imaging protocol

Helical CT scans were performed in end-inspiration from the lung apices through the lung bases using a GE Healthcare CT scanner (GE Healthcare) with a tube voltage of 100 kV for patients under 50 kg and 120 kV for those over 50 kg. The tube current ranged from 20 to 80 mA, adjusted to body weight with automatic exposure control. The CTDIvol values for the scans ranged from 0.64 to 14.04 mGy. Axial CT images were reconstructed in soft tissue and lung algorithms with a slice thickness of 2 mm. Coronal and Sagittal reformats were obtained with a slice thickness of 2 mm and maximum intensity projections were calculated with a slice thickness of 6 mm.

Thymus evaluation

All chest CTs were reviewed by a pediatric radiologist with 8 years of experience (I.V.), who divided the patients into two groups according to the thymus size: Group 1 demonstrated a visual increase in thymus size after CAR T-cell therapy (Figs. 3 and 4). Group 2 demonstrated no change in thymus size or decreased size (i.e., no increase in thymus size) (Fig. 5). Then CT images were imported into OsiriX (Pixmeo, Bernex, Switzerland) and the thymus was outlined using the free-hand drawing tool. Automated 3D volume rendering was used to derive the volume (cm3) of the thymus (Fig s1). In addition, the same radiologist recorded the presence of lung, pleural, and mediastinal abnormalities. To complement this analysis, fluoroscopy images from interventional radiology (IR) procedures for peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line placement were reviewed when available. These IR fluoroscopic images, acquired at clinically relevant time points between the available chest CT and CAR T-cell infusion, provided additional reference for mediastinal silhouette and thymus size assessment. Specifically, the transverse thymic diameter was measured on these fluoroscopic chest images, allowing for comparison of thymic width before and after CAR T-cell therapy.

Axial chest computed tomography (CT) images of a 9-year-old male patient with B-ALL pre- and post-CAR T-cell therapy. a) An axial chest CT image pre-CAR T-cell therapy shows the initial size and shape of the thymus. The thymus presents as triangular tissue in the anterior mediastinal region and does not cause any mass effect on adjacent vessels. b) An Axial chest CT image at 53 days post-CAR T-cell therapy shows an enlarged and more lobulated thymus. The thymus has increased in size (from 0.55cm3to 73.51cm3) and exhibits a lobulated shape with sharp, rounded margins and increased contrast enhancement.

Fluoroscopic chest images from interventional radiology (IR) procedures of a 12-year-old male patient with B-ALL before and after CAR T-cell therapy. a) Frontal fluoroscopic chest image acquired during PICC line placement demonstrates a normal mediastinal contour with no evidence of thymic enlargement. b) Frontal fluoroscopic image at 32 days post-CAR T-cell shows increased prominence of the anterior mediastinal silhouette, suggesting interval thymic enlargement.

Axial chest computed tomography (CT) images of an 18-year-old female patient with ALL before and after CAR T-cell therapy. a) An axial chest CT image pre-CAR T-cell therapy shows the initial size and shape of the thymus. b) An axial chest CT image 32 days post-CAR T-cell therapy shows no significant change in the size and shape of the thymus.

Survival analysis

We evaluated the relation between thymus size and overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS). OS was defined as the time from the date of CAR T-cell therapy injection to death from any cause. EFS was defined as the time from the date of CAR T-cell therapy injection to the occurrence of the first event, such as relapse, progression, or death. OS and EFS were compared between Group 1 and Group 2 to evaluate differences in survival outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Within each group, we compared the median size of the thymus before and after CAR T-cell therapy with a Wilcoxon Sign Rank test. For statistical comparison between two groups of patients we used the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for the continuous variables, while categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Survival outcomes were assessed using Kaplan-Meier analysis, and differences between survival curves were evaluated with the Log Rank test. All statistical analyses were conducted using Origin software (version 2024b) or R version 4.4.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patients and thymus volume

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. Out of 20 patients, 12 (60%) underwent CD19 CAR T-cell therapy, 7 (35%) underwent CD19/22 CAR T-cell therapy, and 1 (5%) underwent CD22 CAR T-cell therapy. Disease burden was undetectable in 16 (80%) patients, low (<5% bone marrow blasts)in 2 (10%) patients, and high (≥5% bone marrow blasts)in 2 (10%) patients.

Seven of 20 (35%) patients demonstrated a visible increase in thymus size and were assigned to Group (1) Thirteen of 20 (65%) patients demonstrated no visible increase in thymus size and were assigned to Group (2). Group 2 included seven patients who showed a decrease in thymus size and six patients who had no significant change in thymus size after CAR T-cell treatment protocol.

In Group 1, the thymus showed a significant increase in volume on chest CT from 5.01 ± 2.18 cm³ before CAR T-cell therapy to 20.87 ± 19.86 cm³ after CAR T-cell therapy (p = 0.01, Fig. 6a). In Group 2, the thymus demonstrated a wide range of volume on chest CTs before therapy. However, there was no increase in thymus size after therapy. Instead, there was a significant decrease in mean thymus volume on chest CT before and after CAR T-cell therapy (3.01 ± 13.42 cm³ vs. 2.09 ± 8.34 cm³, p = 0.01 Fig. 6b).

In Group 1, the thymus showed a significant increase in transverse size on fluoroscopic chest images from 6.96 [0.75] cm before CAR T-cell therapy to 7.14 [1.40] cm after CAR T-cell therapy (p = 0.012, Fig. 6c). In group 2, the transverse thymic size on fluoroscopic chest images did not significantly change after CAR T-cell therapy (p = 0.699 Fig. 6d).

Change in thymus size pre- and post- CAR T-cell therapy. a) In group 1, the thymus volume, as measured on chest CT, significantly increased following CAR T cell therapy, from a median of 5.01 cm³ [interquartile range, IQR: 2.64] pre-CAR T-cell therapy to a median of 20.87 cm³ [IQR: 7.83] post-CAR T-cell therapy (p=0.001). b) In group 2, the thymus volume decreased from a median of 3.1 cm³ [IQR: 8.2] pre-CAR T-cell therapy to a median of 2.9 cm³ [IQR: 5.01] post-CAR T-cell therapy (p=0.001). c) In group 1, the transverse thymic size, as measured on fluoroscopic chest images from interventional radiology procedures, increased significantly following CAR T-cell therapy, from a median of 6.96 cm [IQR: 0.75] to a median of 7.14 cm [IQR: 1.40] (p = 0.012). d) In contrast, group 2 showed no significant change in transverse thymic size on fluoroscopic chest images after CAR T-cell therapy (p = 0.699).

Clinical data of patients with and without increase in thymus volume

Chest CTs after CAR T-cell injection were performed as part of the HSCT preparation for 7 patients from Group 1 and 7 patients from Group 2. In addition, 6 scans were conducted to evaluate possible infections in Group 2.

Clinical data comparisons between the patients with (Group 1) and without (Group 2) thymus size increase are summarized in Table 2. All patients had pre-CAR CT scans performed before completing lymphodepleting chemotherapy. The median [IQR] interval between lymphodepleting chemotherapy and pre-CAR chest CT was 120 days [931]. The median interval between the pre–CAR T-cell chest CTs and CAR T-cell infusion was significantly longer in Group 1 compared to Group 2 (p = 0.014). Meanwhile, there was no significant difference between Group 1 and 2 regarding the median interval between pre- IR fluoroscopic images and CAR T-cell infusion (p = 0.391). The median interval for the post–CAR T-cell chest CTs for Group 1 was 92 days, with a range of 168 days. For Group 2, the median interval was 40 days, with a range of 87 days. There was no significant difference between Group 1 and 2 regarding the median interval between CAR T-cell therapy and post-CT scan (p = 0.091).

There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of sex, ethnicity, race, steroid treatment history, HSCT history, and CRS grade (ps > 0.05). All seven patients in Group 1 received HSCT long after the CAR T-cell therapy which did not affect the size of the thymus. When CAR T-cell persistence was compared, no significant difference was shown between the groups (p = 0.165).

The patients in Group 1 were significantly younger (median [IQR], 12 [8] years) compared to patients in Group 2 (19 [10], p = 0.028). Group 1 patients received bispecific CD19/22-targeted CAR T-cells (5/7, 72%) more frequently compared to Group 2 patients (2/15, 15%; p = 0.044). One patient received CD22 targeting CAR T-cells and did not show an increase in thymus volume. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of disease burden (p = 0.249). Absolute and relative lymphocyte counts using flow cytometry, and bone marrow aspiration (blasts and lymphocytes) after CAR T-cell therapy did not differ between the two groups (all p-values > 0.05). Group 1, characterized by post-treatment thymic enlargement, exhibited higher absolute lymphocyte counts compared to Group 2, which showed no thymic increase. While this trend may suggest enhanced immune reconstitution in Group 1, the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.081) (Fig. 7). The median interval for the post–CAR T-cell lymphocyte collection was 92 days for group 1 (range 168 days) and 40 days for group 2 (range 87 days). Due to the large range, there was no significant difference between Group 1 and 2 regarding the time interval between CAR T-cell therapy and post-lymphocyte collection (p = 0.091). Meanwhile, patients in Group 1 (with increased thymus size) demonstrated significantly higher percentages of CD4⁺ RTEs compared to Group 2 (p = 0.014; Fig. 8a). Similarly, absolute counts of CD4⁺ RTEs were significantly higher in Group 1 than in Group 2 (p = 0.032; Fig. 8b). The median interval for the post–CAR T-cell RTEs collection was 57 days for Group 1 (range 168 days) and 145 days for Group 2 (range 189 days). There was no significant difference between Group 1 and 2 regarding the time interval between CAR T-cell therapy and post-RTEs collection (p = 0.606).

Lymphocyte counts by flow cytometry after CAR T-cell therapy. Group 1 (patients with increased thymic size) showed higher absolute lymphocyte counts, indicating a trend toward greater immune recovery compared to Group 2 (patients without thymic size increase); however, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.081).

CD4 Recent Thymic Emigrants (RTEs) by flow cytometry after CAR T-cell therapy. a) Group 1 (patients with increased thymic size) showed a higher percentage of RTEs compared to Group 2 (patients without thymic size increase; p = 0.014). b) Patients in Group 1 demonstrated significantly elevated absolute counts of CD4⁺ RTEs compared to patients from Group 2 (p = 0.032), indicating a trend towards greater thymic regenerative activity and enhanced T-cell reconstitution following therapy.

Survival analysis

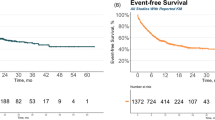

In Group 1, all patients (100%) survived. In Group 2, 7 of 13 patients (53.85%) died (p = 0.017). All deceased patients (35%) were in Group 2. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Group 1 and Group 2 were significantly different (Log Rank test, p = 0.017) (Fig. 9a). In Group 1, all patients (100%) survived event-free during the observation period. In Group 2, 10 of 13 patients (77%) experienced an event (relapse or death) during the follow-up time. All events (100%) occurred in Group 2. Event-free survival was significantly different between Group 1 and Group 2 (p = 0.003) (Fig. 9b). In Group 1, 3 patients received interval therapy and 4 did not. Out of the 13 patients in Group 2, 6 received interval therapy and 7 did not (Fig. 2).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with (blue line, group 1) and without (yellow dashed line, group 2) thymus enlargement after CAR T cell treatment protocol. a) Patients with thymus enlargement after CAR T-cell treatment showed prolonged survival compared to patients without thymus enlargement (p = 0.017). b) Patients with thymus enlargement after CAR T-cell treatment showed higher event-free survival compared to patients without thymus enlargement (p = 0.003).

Survival analysis based on CAR T-cell therapy type revealed significant differences in both overall survival (Log-rank test, p < 0.001) and event-free survival (Log-rank test, p = 0.01) (Fig. 10a and b). To evaluate whether the observed survival differences between patients with and without thymic increase were confounded by CAR T-cell product type, a stratified log-rank test using CAR T-cell type (CD19 vs. CD19/22) as a stratification factor was performed. After controlling for CAR T-cell type, patients in Group 1 continued to show significantly better outcomes compared to Group 2, with a p-value of 0.036 for overall survival and 0.006 for even-free survival.

Additional chest CT findings

Most cases in both groups showed normal chest CT findings (5 patients [72%] in Group 1 and 6 patients [46%] in Group 2). Ground-glass opacities were more frequent in Group 2 (5 patients [38%]) compared to Group 1 (none [0%]). However, overall chest CT findings did not show any significant differences between Group 1 and Group 2 (p > 0.99) (Table 3).

Discussion

Our data showed a heterogeneous response in thymus size among children and young adults with ALL treated with CAR T-cell treatment protocols. While some patients exhibited significant thymic enlargement, others showed no change or a decrease in size. Patients whose thymus increased after CAR T-cell treatment protocol tended to be younger and demonstrated improved outcomes compared to patients whose thymus did not increase.

CAR T-cells are genetically modified ex vivo, with the final product circumventing the natural education process typically occurring in the thymus. Consequently, CAR T-cell therapy manufactured from the peripheral blood contains mature T-cells11 that bypass the thymus, despite acquiring new specificity.

The thymus volume increase observed in younger patients can be explained by the natural evolution of the thymus. The thymus is relatively large at birth and reaches its maximum size in the first few years of life. During this time, it is highly active in education and maturation T cells, which is essential for developing a robust immune system. After reaching its peak size, the thymus remains relatively stable in size until around puberty, when it is most effective at education and maturation T cells12. Post-puberty, the thymus begins to undergo involution. Hormonal changes associated with puberty trigger this reduction in both size and functional capacity13. By early adulthood, the thymus is smaller, and much of its tissue is replaced by adipose (fat) tissue14. Although it retains some functionality, the output of naïve T cells is significantly decreased15. In older adults, the thymus continues to shrink, which is linked to a decline in immune function and increased vulnerability to infections and diseases16.

Chemotherapy and steroid therapy may lead to a reduction in thymus size in children17,18. After chemotherapy, the thymus can rebound, typically within 6 to 12 months, depending on the patient’s age19. Jerushalmi, J., et al. reported that an increase in thymus size after completion of steroid and chemotherapy in children with solid tumors is more commonly observed in patients with an age of 11–20 years compared to patients with an age of 21–30 year20. Patients under 40 years of age showed more robust thymic regeneration and faster recovery of thymic function compared to older adults21. Cytotoxic chemotherapy can lead to thymic atrophy or involution due to both direct effects on thymic epithelial cells22 and indirect effects caused by severe lymphopenia23. Due to the significant damage inflicted on the thymus and bone marrow, there is a delayed restoration of thymic activity, with rebound typically observed 12 months or more post therapy24.

Pre-CAR-T cell lymphodepleting chemotherapy is specifically designed to reduce the number of existing lymphocytes (including T and B cells) in the body directly before CAR-T cell infusion. This most commonly includes agents that selectively deplete lymphocytes, such as fludarabine and cyclophosphamide. Lymphodepleting regimens, while they reduce circulating lymphocyte levels, may not directly damage the thymic architecture as severely as alternative cytotoxic anti-cancer chemotherapy. Thus, the thymus may be left somewhat intact. Reduction of the number of existing lymphocytes creates a more favorable environment for CAR-T cells to proliferate upon infusion. This leads to a more robust expansion of the CAR-T cells, which can enhance overall therapeutic efficacy. With a less toxic impact on the thymus, there may be a greater potential for thymic recovery and increased thymopoiesis following lymphodepleting chemotherapy. There is also rationale that post-CAR thymopoiesis relates to the pro-inflammatory state triggered by antigen-driven CAR T cell expansion. While the CAR-T cells proliferate extensively, the combination of lymphodepleting chemotherapy and CAR-T cells may also create a favorable immune environment by potentially eliminating myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) or regulatory T cells (Tregs) that dampen thymic function25. This rapid CAR T cell proliferation may create a feedback loop that enhances thymic function and size quicker than what is seen after traditional chemotherapy. A direct effect of lymphodepleting chemotherapy on thymus size cannot be excluded, particularly given that these agents are known to impact thymic tissue. However, while all patients received the same lymphodepleting therapy, some patients demonstrated subsequent increased in thymus size while others did not. While quantifying lymphodepletion exposure could strengthen causal inference, the current findings should be interpreted within the context of the entire CAR T-cell treatment protocol. As such, it is more appropriate to refer to the observed changes in thymus size as occurring following the CAR T-cell treatment protocol, which includes lymphodepleting chemotherapy, rather than attributing these changes solely to the CAR T-cells themselves. Further mechanistic study is warranted to better establish and understand patterns of thymic evolution post-CAR T cell therapy.

Regardless of the specific underlying causes and mechanisms, the observed increase in thymus size following CAR-T cell therapy was closely associated with positive clinical outcomes, possibly due CAR-mediated thymic activity that has a permissive role in achieving CAR T cell immune memory, or due to enhanced reconstitution of immune cells that play a role in re-establishing cancer-specific immune surveillance and protection. A larger thymus size signifies increased thymopoiesis, indicating a vigorous immune reconstitution process. This enhanced immune function may enable better recognition and elimination of residual cancer cells, potentially leading to prolonged remission periods and improved overall survival rates. Therefore, the increase in thymus size may serve as a promising new biomarker of successful immune recovery and favorable therapeutic response.

Our patients demonstrated thymic enlargement between 30 days and up to 11 months (92 days) after CAR T-cell infusion, which was observed earlier than typical thymic rebound after the chemotherapy usually occurring within 1 year of treatment26. In addition, all our patients had a pre-CAR T-cell CT scan, confirming that the thymus had a smaller size before CAR T-cell infusion and a larger size at various intervals afterwards. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first observation of a thymus enlargement after CAR T-cell treatment protocol.

Interestingly, all patients with thymic enlargement survived while 13 of 20 patients who did not demonstrate thymic enlargement died. Kooshesh et al. reported that patients who underwent a thymectomy have significantly higher mortality, cancer, and autoimmune diseases compared to those who retain their thymus27. Loskog et al. reported that increased regulatory T-cells frequency following thymic atrophy creates a hostile tumor microenvironment for CAR T-cells who are already prone to exhaustion28. The same was observed with monoclonal antibodies, where Treg presence similarly inhibited their effectiveness29. Interestingly, animal studies showed that peripheral T cells can re-enter the thymus and interfere with central tolerance induction30. By depleting antigen-presenting cells (APCs) expressing tumor antigens in the thymus, CAR T-cell treatment protocol holds the potential to reduce negative selection and promote the development of a more robust endogenous antitumor T-cell repertoire. This could lead to improved long-term antitumor immunity and potentially contribute to more durable responses in patients.

We found patients with increasing thymus size who had elevated levels of RTEs following CAR T-cell treatment protocol, suggesting that preserved thymic volume may support de novo T-cell regeneration in this setting. This is consistent with prior reports highlighting the utility of CD31 + CD45RA + CD4 + T cells as reliable markers of thymic output during immune reconstitution, particularly in lymphopenic children post-HSCT31. While most existing studies on RTEs focus on allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation32,33,34,35, our findings suggest thymus integrity may also be an important determinant of immune recovery after CAR T-cell therapy.

We recognize several limitations of our study. Firstly, we investigated changes in thymus size retrospectively in a limited number of patients. A larger prospective clinical trial will be required to confirm our findings. Our patient population was too small to evaluate the effect of prior treatments, disease burden, and individual recovery timelines on thymus responses in our patients. Secondly, patients who showed an increase in thymic size had a longer interval between the pre–CAR T-cell chest CT and the CAR T-cell infusion compared to those without thymic enlargement. Therefore, we cannot fully rule out the potential impact of this interval on the observed thymic size increase. Future studies with regular imaging intervals before and after CAR T-cell infusion will help clarify the temporal dynamics of thymic changes.

Conclusion

We observed thymic enlargement on CT scans in a patient subset with B-ALL following CAR T-cell treatment protocol. These children and young adult patients demonstrated signs of thymic activation, immune recovery and improved outcomes compared to patients who did not show an increase in thymus size. Further research is warranted to elucidate mechanism, clinical significance and potential role in treatment outcome evaluation.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Institute NC. SEER cancer stat facts: Childhood leukemia (Ages 0–19). https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/childleuk.html. (2022).

Siegel, R. L. M. K., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA: A cancer J. Clin. 72, 7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21708 (2022).

Lee, D. W. K. et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: A phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet385, 517–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3 (2015).

John, S. P. M. et al. Real-world outcomes for pediatric and young adult patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) treated with tisagenlecleucel: Update from the center for international blood and marrow transplant research (CIBMTR) registry. Blood138(Supplement 1), 428. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2021-146393 (2021).

Maude, S. L. L. T. et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med.378, 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709866 (2018).

Turtle, C. J. H. L. et al. Immunotherapy of non-hodgkin’s lymphoma with a defined ratio of CD8 + and CD4 + CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor–modified T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 2123–2138. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI85309 (2016).

Xing, Y. H. K. T-cell tolerance: central and peripheral. Nat. Immunol. 17, 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3419 (2016).

Mackall, C. L. F. T. et al. Lymphocyte depletion during treatment with intensive chemotherapy for cancer. Blood84, 2221–2228 (1994).

Williams, A. P. Immune reconstitution in children following chemotherapy for acute leukemia. eJHaem 1, 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/jha2.27 (2020).

Fouda, A. How to detect rare pediatric endocrine neoplastic conditions linked. An. Pediatr.91, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anpedi.2018.10.021 (2019).

Noaks, E. K. E. & Bracewell, D. G. Enriching leukapheresis improves T cell activation and transduction efficiency, and downstream CAR T-cell processing. Mol. Therapy – Methods Clin. Dev. 20, 675–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtm.2021.02.002 (2021).

Kushida, Y. K. S. et al. T cells affect thymic involution during puberty by inducing regression of the adrenal reticularis. J. Physiological Sci. 62, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-012-0194-y (2012).

Hun, M. L. W. K., Gunawan, J. R., Alsharif, A., Quinn, K. & Chidgey, A. P. Gender Disparity Impacts on Thymus Aging and LHRH Receptor Antagonist-Induced Thymic Reconstitution Following Chemotherapeutic Damage. Front. Immunol. 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00302 (2020).

Araki, T. N. M. et al. Normal thymus in adults: Appearance on CT and associations with age, sex, BMI and smoking. Eur. Radiol.26, 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3796-y (2016).

Hale, J. S. B. T., Turk, G. L. & Fink, P. J. Thymic output in aged mice. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 103, 8447–8452. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0601040103 (2006).

Palmer, S. . A. L., Blackburn, C. C. & Newman, T. J. Thymic involution and rising disease incidence with age. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 1883–1888. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1714478115 (2018).

Choyke, P. L. Z. R., Gootenberg, J. E., Greenberg, J. N., Hoffer, F. & Frank, J. A. Thymic atrophy and regrowth in response to chemotherapy: CT evaluation. Am. J. Roentgenol.149, 269–272. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.149.2.269 (1987).

Min, H. M. R. E. & Dorshkind, K. Reassessing the role of growth hormone and sex steroids in thymic involution. Clin. Immunol. 118, 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2005.10.015 (2006).

Chen, C. H., Hsiao, C. C., Chang, T. H. & Shih, H. J. Rebound thymic hyperplasia after chemotherapy in children with lymphoma. Pediatr. Neonatol. 58, 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedneo.2016.02.007 (2017).

Jerushalmi, J. F. A., Bar-Shalom, R., Khoury, J. & Israel, O. Physiologic thymic uptake of 18F-FDG in children and young adults: A PET/CT evaluation of incidence, patterns, and relationship to treatment. J. Nucl. Med.50, 849–853. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.108.058586 (2009).

Hakim, F. T. M. S. et al. Age-dependent incidence, time course, and consequences of thymic renewal in adults. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 930–939. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI22492 (2005).

Fletcher, A. L. L. et al. Ablation and regeneration of tolerance-inducing medullary thymic epithelial cells after cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone treatment. J. Immunol.183, 823–831. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0900225 (2009).

Sfikakis, P. P. G. G., Moulopoulos, L. A., Kouvatseas, G., Theofilopoulos, A. N. & Dimopoulos, M. A. Age-related thymic activity in adults following chemotherapy-induced lymphopenia. Eur. J. Clin. Invest.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2005.01499.x (2005).

Sun, D. P. W. L. et al. Investigating factors associated with thymic regeneration after chemotherapy in patients with lymphoma. . Front Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00654 (2016).

Hu, J. S. C. et al. T-cell homing therapy for reducing regulatory T cells and preserving effector T-cell function in large solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1365 (2018).

Franke, F. C. D. A. et al. Differentiation between rebound thymic hyperplasia and thymic relapse after chemotherapy in pediatric hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 70, https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.30421 (2023).

Kooshesh, K. A. F. B., Sykes, D. B., Gustafsson, K. & Scadden, D. T. Health consequences of thymus removal in adults. N. Engl. J. Med.389, 406–417. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2302892 (2023).

Loskog, A. G. V., Rossig, C., Pule, M., Dotti, G. & Brenner, M. K. Optimization of conditions for clinical scale expansion of cytotoxic T lymphocytes for immunotherapy. Leukemia 20, 1819–1828. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2404366 (2006).

Duell, J. D. M. et al. Frequency of regulatory T cells determines the outcome of the T-cell-engaging antibody blinatumomab in patients with B-precursor ALL. Leukemia31, 2181–2190. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2017.41 (2017).

Edelmann, S. L. B. T. Peripheral T cells re-enter the thymus and interfere with central tolerance induction. J. Immunol.186, 5612–5619. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1004010 (2011).

Junge, S. et al. Correlation between recent thymic emigrants and CD31+ (PECAM-1) CD4 + T cells in normal individuals during aging and in lymphopenic children. Eur. J. Immunol.37, 3270–3280. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.200636976 (2007).

Drozdov, D. et al. Dynamics of recent thymic emigrants in pediatric recipients of allogeneic hematopoetic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 57, 620–626. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-022-01594-w (2022).

McAvoy, D. et al. Predictors for recent thymic emigrant T cell reconstitution after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Transplantation Cell. Therapy. 30, S313–S314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtct.2023.12.432 (2024).

Justus, J. L. P. et al. Immune recovery and the role of recent thymic emigrated T lymphocytes after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cytotherapy 26, 980–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcyt.2024.04.073 (2024).

Drozdov, D., Luo, X., Marsh, R. A., Abraham, R. S. & Ebens, C. L. Relevance of recent thymic emigrants following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for pediatric patients with inborn errors of immunity. Transplantation Cell. Therapy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtct.2025.02.003 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), grant number R01 CA269231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.V. and H.K. share the first authorship as they made equal contributions to the work I.V. H.K and H.E.D-L. wrote the manuscript I.V. prepared Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5; Table 3, H.K prepared Figs. 1 and 6; Table 1, and 2. T.L. performed statistical analysis, to evaluate study outcomes and ensure data reliability. C.E., C.B., L.M.S., S.R., K.D provided clinical information, guided the interpretation of results, and assisted in identifying relevant correlations between imaging findings and clinical outcomes. H.D.L. supervised all image data reviews and analyses, communicated with the journal, managed responses to editorial and reviewer comments and ensured adherence to journal guidelines. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Laboratory results

In the laboratory analysis, the following parameters were evaluated to understand the impact of CAR T-cell therapy on the immune system and overall patient condition. Lymphocyte absolute count measures the absolute number of lymphocytes in the blood (cells/µL). Lymphocyte Percentage - the percentage of lymphocytes among the total white blood cells. It helps in understanding the proportion of lymphocytes in the immune system. Changes in this percentage can indicate shifts in immune system dynamics. Neutrophil absolute counts measure the absolute number of neutrophils in the blood (cells/µL). Neutrophil percentage reflect the relative number of neutrophils among the total number of white blood cells. Flow cytometry lymphocyte percentage describes the percentage of lymphocytes identified by flow cytometry, a technique used to analyze the physical and chemical characteristics of cells. It provides detailed insights into the types and states of lymphocytes present in the blood. Flow cytometry lymphocyte absolute count measures the absolute count of lymphocytes identified by flow cytometry (cells/µL). It provides a precise count of lymphocyte populations, which is essential for understanding the detailed immune status of the patient. Bone marrow blast percentage reflects the percentage of blast cells in the bone marrow. Blast cells are immature cells that can give rise to different types of blood cells. An increased percentage of blasts can be indicative of leukemia or other bone marrow disorders. Bone marrow lymphocyte count is the count of lymphocytes in the bone marrow. It helps in understanding the bone marrow’s contribution to the overall lymphocyte population and its health status. Ferritin is a blood protein that contains iron. It is used to understand the body’s iron stores and can also be an indicator of inflammation. High levels of ferritin can indicate inflammation, infection, or iron overload, while low levels can indicate iron deficiency.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vasyliv, I., Kim, H.G., Erickson, C. et al. Impact of CAR T cell therapy on thymus size in children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Rep 15, 30360 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12630-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12630-2