Abstract

The development of high-performance photovoltaic materials is a major focus of renewable energy research. Among the most promising candidates are quaternary chalcogenides, renowned for their exceptional electronic and optical properties. In this paper, a conventional Cu2MnSnS4-based solar cell is proposed, and numerical analyses are performed using wxAMPS-1D software to optimize the electron transport layer (ETL) and hole transport layer (HTL). Results indicate that using SnS2 as ETL and CZTS as HTL significantly improves performance, achieving optimal interface energy alignment. Key parameters, including thickness, doping concentration, and defect density for each layer, along with the influence of temperature and contact barrier heights, are analyzed. Optimizing these parameters leads to an efficiency enhancement from an initial 19.43–27.71%, surpassing previously reported values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal chalcogenides have emerged as a promising choice in photovoltaic technology, offering a reliable alternative to conventional silicon-based solar technologies. These materials have unique properties that lead to improved photovoltaic conversion efficiency while reducing production costs. Moreover, they contribute to long-term sustainability due to their relative abundance in nature1. Prominent examples of metal chalcogenides are CdTe and CIGS, which have suitable bandgaps and high optical absorption properties, enabling them to achieve efficiencies of up to 22.3%2 and 23.35%2,3, respectively. However, the reliance on cadmium causes environmental and health concerns due to its high toxicity, while CIGS, despite offering higher efficiency, faces challenges related to high production costs, mainly due to the scarcity of indium (In) and gallium (Ga)1. Alternatively, Cu2ZnSnS4 (CZTS) offers a good efficiency of about 12.6%, along with its environmental sustainability2.

CZTS has a high absorption coefficient in the visible wavelength range, as well as a direct band gap of about 1.5 eV4,5,6. However, its performance is still lower than expected due to structural defects, especially CuZn antisite, where Cu atom replaces Zn, which is formed due to the similarity in size and crystal environment between Cu and Zn, as well as the manufacturing conditions. This defect creates a deep energy level inside the bandgap, which promotes non-radiative recombination and thus reduces the open-circuit voltage, Voc. To address this problem, researchers have proposed replacing zinc with other elements such as barium (Ba), manganese (Mn), strontium (Sr), and iron (Fe), as these elements provide better compatibility with the crystal lattice of CZTS7]– [8.

Cu2MnSnS4 (CMTS) emerges as a particularly advantageous candidate due to its non-toxicity, abundance, and direct optical band gap (1-1.63 eV) suitable for efficient solar absorption. Unlike CZTS, CMTS benefits from manganese’s larger ionic radius, which mitigates defects and enhances lattice regularity and stability9]– [10. Experimental studies have shown that the efficiency of solar cells based on CMTS achieved 0.19%11, 0.49%12, 0.83%13, 0.92%14, while the maximum reported efficiency reached 1.79%15. In contrast, a simulation study of a heterostructure solar cell based on CMTS, conducted using the SCAPS-1D simulator, examined the effect of various buffer layers on device performance and reported an efficiency of 20.26%16. In another study, solar cells were designed using CdS, CMTS, and SnS as the buffer, absorber, and back surface field (BSF) layers, respectively17. More recently, the highest reported numerical efficiency of 31.54% was achieved by employing ZrS2 as a buffer layer18. Despite these notable advancements in the performance of CMTS-based solar cells, the influence of the hole transport layer (HTL) and back contact has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

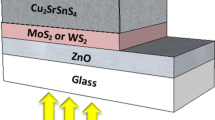

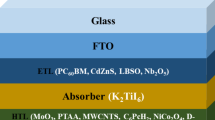

In the present work, the effect of WS2, TiO2, ZnO, SnS2, ZnS, CdS, and WO3 as electron transport layers and MoS2, CuO, SnS, CuSbS2, and CZTS as hole transport layers on the performance of CMTS-based solar cells was studied using the wxAMPS-1D simulator, where the structure (Al/ITO/SnS2/CMTS/CZTS/Mo) was selected as the cell with the highest efficiency obtained. Then, thickness, doping concentration, and defect density in each layer of the proposed device were optimized. Finally, the effect of temperature and front/back contact barrier heights were analyzed. The obtained results were compared with those reported in previous works. This study revealed that the combination of CMTS as absorber layer, SnS2 as ETL, and CZTS as HTL provides great potential in improving the performance. These results reflect the great importance of choosing the right materials in the design of solar cells to achieve improved performance.

Methods and modeling

Model development

The wxAMPS-1D simulator applies fundamental semiconductor equations under steady-state conditions, assuming idealized layer interfaces without extensive surface states or extrinsic defects beyond those explicitly defined.

The simulator primarily relies on semiconductor equations to describe the electronic and photonic behavior of solar cell structures. These equations include the Poisson equation, the continuity equation for free electrons, and the continuity equation for free holes19,20,21. Poisson’s equation is:

.

Where V denotes the electrostatic potential, εs is the dielectric constant, q is the electron charge, n and p are the electron (hole) carrier concentration, ND+ and NA− are the ionized donors (acceptors) density, pt and nt are the trapped electrons (holes) density. The equations of continuity for electrons and holes are:

.

Jn and Jp are the electron and hole current density, which can be expressed by the following equations:

.

Where Rn and Rp symbolize the electrons (holes) recombination rate, Gn and Gp are the electron (hole) generation rate, Efn and Efp are the quasi-Fermi level of electrons (holes), µn and µp are the electron (hole) mobility.

Various outputs can be extracted from wxAMPS-1D simulation, such as voltage and current characteristics under dark and illuminated conditions, quantum efficiency, generation-recombination features, electric field distribution, free and trapped carrier densities, and equilibrium energy band diagram. This is achieved by solving the coupled nonlinear tri-diagonal differential equations with appropriate boundary conditions19. A more comprehensive explanation of the model and the application of boundary conditions can be found in the previous work22.

The height of the front and back contact barriers plays a crucial role in solar cell devices. The contact barrier refers to the height of the electrical barrier between different layers within the solar cell. The barrier heights of the front and back contacts (\(\:{\phi\:}_{BF},\:{\phi\:}_{BB}\)) are determined by the following equations, respectively:

.

Where \(\:{\phi\:}_{WF}\) and \(\:{\phi\:}_{WB}\) represent the work functions of the front and back contacts, respectively. \(\:{\chi\:}_{SCF}\) and \(\:{\chi\:}_{SCB}\) denote the electron affinity of the semiconductor layers21,23.

System presentation

The purpose of this study is to identify suitable ETL and HTL for the CMTS absorber layer. The schematic representation of the considered solar cell is illustrated in Fig. 1. The primary cell has WS2 as ETL and SnS as HTL. The physical parameters of the ITO, WS2, CMTS, and SnS layers, as well as the device parameters utilized in the simulation, are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. In this work, all simulations were conducted under AM 1.5 solar spectrum conditions, with an irradiance of 1000 W/cm2 and an ambient temperature of 300 K. Throughout the simulation, the CMTS absorber layer exhibits a constant absorption coefficient of 105 cm− 116.

Determining the values of both CBO and VBO helps in analyzing the energy alignment between layers and facilitates an understanding of the effect of the contact interfaces on charge transport. The conduction band offset CBO at the ETL/absorber interface is defined as:

.

The valence band offset VBO at the absorber/HTL interface is defined as:

.

Where \(\:{{\upchi\:}}_{\text{a}\text{b}\text{s}\text{o}\text{r}\text{b}\text{e}\text{r}}\), \(\:{{\upchi\:}}_{\text{E}\text{T}\text{L}}\:\)and \(\:{{\upchi\:}}_{\text{H}\text{T}\text{L}}\) are the electron affinities of the absorber, ETL, and HTL respectively. \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{g}.\:\text{a}\text{b}\text{s}\text{o}\text{r}\text{b}\text{e}\text{r}}\) and \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{g}.\:\text{H}\text{T}\text{L}}\:\)are the band gaps of the absorber and HTL24.

These relationships provide a theoretical basis for evaluating the compatibility of the selected materials, which contributes to the interpretation of the results obtained from this study.

Results and discussions

Figure 2 illustrates the J-V characteristic of the proposed primary solar cell, which is composed of a CMTS absorber layer, SnS as HTL, and WS2 as ETL. The simulation results revealed that this configuration achieved an efficiency of 19.43%, with a fill factor FF of 74.30%, a short circuit current Jsc of 22.74 mA/cm², and an open circuit voltage Voc of 1.1504 V. Compared to reference9, which analysed a similar solar cell without an HTL and based on CdS as ETL, the recorded efficiency was found to be 16.5%, with a higher FF of 77.9% and a higher Jsc of 24.10 mA/cm², while the Voc was lower and estimated at 0.88 V.

It is noted that using SnS as HTL produced an enhancement in Voc of 0.88 V to 1.1504 V, which can be explained by the improved alignment of energy levels and reduced recombination at the CMTS/HTL interface by forming the valence bandgap offset VBO=-0.25 eV between the CMTS and the HTL, which facilitates hole transport to the back contact. In contrast, using WS2 instead of CdS as the ETL resulted in a lower FF, which may be due to the higher series resistance (Rs) as a consequence of the change in the conduction band gap CBO at the CMTS/WS2 interface (-0.35 eV) compared to the CMTS/CdS interface (-0.15 eV). Due to the higher CBO, the system may need a stronger internal electric field to drive electrons across the interface, which leads to increased ohmic losses during operation. In addition, the lower Jsc may be related to the optical properties of WS2 and its effect on light absorption and charge transfer efficiency at the interface with the absorber layer.

Impact of electron transport layer on device performance

The electron transport layer (ETL) plays a pivotal role in improving the performance of solar cells by enhancing charge transport and reducing electrical losses. The choice of material used as ETL affects the energy band alignment at the interface (ETL/absorber), which results in changes in the conduction band offset (CBO) between the two layers. This study aims to analyse the effect of CBO changes on the overall performance of the solar cell.

The effect of WS2, TiO2, ZnO, SnS2, ZnS, CdS, and WO3 materials used as ETLs on the device performance was studied. Table 3 presents the properties of the proposed ETLs. Figure 3 illustrates the energy band alignment of ETL materials relative to the CMTS absorber layer. Moreover, Table 4 represents valence and conduction band offsets (VBO and CBO) for various ETLs. The effect of different ETLs on the merit factors and J-V characteristic of the solar cell is shown in Fig. 4a and b, respectively.

The efficiency PCE, fill factor FF and current density Jsc showed a significant gradual improvement as the CBO barrier moved from negative to positive values, with the performance reaching its maximum at CBO = + 0.11 eV corresponding to the use of SnS2 as ETL, achieving an efficiency of 22.93%, FF of 85.94%, Jsc of 23.26 mA/cm2 and Voc of 1.1469 V. After that, with increasing CBO value, a decrease in the device performance was observed. This behaviour can be explained by the different carrier dynamics in these materials and their interface properties with the absorber7.

At negative values of CBO, the barrier between the ETL and the absorber layer takes a cliff-like configuration (Fig. 5a), which results in a lower conduction band energy of the ETL compared to the absorber. This energy level alignment limits efficient electron transport, leading to current loss across the interface instead of flowing in an organized manner toward the external circuit, causing a decrease in PCE, FF, and Jsc. As CBO increases towards positive values, the energy barrier gradually transforms into a spike-like configuration, where the conduction band energy of the ETL rises compared to the absorber layer. Initially, this gradient is moderate, allowing for smooth transfer of the photogenerated electrons from the absorber to the ETL, thereby enabling efficient carrier separation, which explains the gradual improvement in device performance up to CBO = + 0.11 eV (Fig. 5b). However, beyond this value, the spike-like barrier becomes sharper (Fig. 5c), which limits the flow of electrons across the interface and increases the series resistance (Rs), thus reducing the fill factor FF, which negatively affects PCE and Jsc.

Voc stability across ETL variations arises from minimal changes in the shunt resistance and consistent recombination characteristics at the interfaces37. A.R. Latrous et al. studied the effect of CBO changes on the performance of CZTS-based solar cells; the results obtained align with our findings38. As a result of its CBO = 0 eV, the efficiency rose to 22.68%; in this scenario, the ETLs’ conduction band energy level aligns with the absorber layers. Effective current transfer is ensured since the photogenerated electrons can pass through the absorber layer and reach the ETL without running into any energy barriers.

Evaluated the impact of various buffer layers on the overall performance of CMTS-based solar cells and verified that SnS2 shows favourable energy alignment with the CMTS absorber layer, attaining an efficiency of 20.26%, which is similar to our data16. In another investigation, the solar cell (Pt/ZnO: Al/ZnMgO/SnS2/CMTS/Mo/SLG) was proposed by A. Kowsar et al.10, which achieved an efficiency of 25.03%, FF = 85.49%, Jsc = 23.69 mA/cm2, and Voc = 1.236 V. The following factors contribute to this devices higher efficiency when compared to our study: (1) Platinums high work function as a front contact helps to lower energy barriers; (2) Mo/SLGs superior qualities, as described in the work39, can improve performance when used in place of Mo; and (3) the double-layer window helps to increase transfer efficiency.

Besides, the Voc obtained in our study (1.14 V) is found to be lower than that reported in the work10 (1.23 V). Although HTL improves the transport properties, the high VBO value (-0.25 eV corresponding to the use of SnS as HTL) could be the reason for this decrease. Therefore, in the next part of this study, the analysis of solar cell performance will be carried out by modifying the VBO value using different materials as HTLs.

Impact of hole transport layer on device performance

Based on the analysis of the effect of various materials on the performance of the solar cell, SnS2 was adopted as a suitable electron transport layer ETL for the proposed device. Similarly, the most suitable material will be selected as the hole transport layer HTL to ensure the best possible performance. HTL acts as an intermediate layer that facilitates the transport of holes from the absorber layer to the back contact. Table 5 provides a summary of the characteristics of the materials utilized as HTLs, and Fig. 6 illustrates how the energy bands of the HTLs correspond with the CMTS absorber layer. Table 6 provides the valence and conduction band offsets (VBO and CBO) for various HTLs.

Figure 7a illustrates the impact of modifying the hole transport layer (HTL) on the current-voltage (J-V) characteristics, while Table 7 presents the corresponding changes in the solar cell merit factors. When there is no hole transport layer, the lowest values are recorded: Voc is 0.9771 V, FF is 84.63%, Jsc is 23.20 mA/cm2, and PCE is 19.18%. Upon adding HTL, there was a significant improvement in FF, Voc, and PCE, while a slight change was recorded in Jsc. This is because the quantum efficiency (QE) is not significantly affected by the addition of HTL, as shown in Fig. 7b, due to its location on the back of the device42.

The Voc strongly depends on the valence band offset (VBO); a significantly positive VBO impedes hole transfer, increasing recombination, while a slightly negative or near-zero VBO enhances hole transport efficiency and Voc. Voc is affected by the barrier VBO as follows:

(1) VBO is significantly positive; it is difficult for holes to move from the absorber to the HTL, increasing the probability of their recombination with electrons, negatively impacting Voc.

(2) If VBO is close to zero or slightly negative, it is easier for holes to migrate from the absorber to the HTL, reducing the recombination at the interface, leading to an increase in Voc. When using CZTS as the HTL, the solar cell performance reached its highest value of 25.63%, with a VBO of + 0.05 eV. This positive VBO led to the formation of a spike-like configuration at the CMTS/CZTS interface (Evabsorber > EvHTL), as shown in Fig. 8a, which facilitated the transport of holes at the interface.

(3) VBO is too negative; holes may drift back to the absorber instead of moving to the HTL. This increases recombination and reduces Voc. This is the case when MoS2 is used as HTL with a VBO of -0.51 eV, which results in a cliff-like configuration (Evabsorber < EvHTL), as shown in Fig. 8b, resulting in a performance drop of 19.70%. Figure 9 confirms the relationship between the Voc and the recombination rate at the CMTS/HTL interface43,44. CZTS was selected as a suitable hole transport layer (see Table 7).

Optimization of thickness and doping concentration in different layers of the proposed device

Enhancing the solar cell layers thickness and doping concentration lowers costs by using less material and making sure that the least amount of doping is required to achieve high efficiency.

Variations in solar cell merit factors between absorber thicknesses of 0.5 and 4 μm and doping concentrations of NA between 1014 and 1017 cm− 3 are seen in Fig. 10. From Fig. 10a, it is noted that before approximately 2 μm, the PCE increases with increasing absorber thickness (CMTS). This is due to an enhancement in both Jsc and Voc as a result of enhanced photon absorption, which in turn leads to increased photogenerated charge generation. Meanwhile, the PCE decreases with increasing doping concentration due to a decrease in Jsc, as Fig. 10b shows. This may be due to the stimulation of recombination by increasing the charge carrier density, which reduces the possibility of collecting photogenerated electrons. In contrast, an improvement in Voc was recorded with increasing NA, as shown in Fig. 10c. This is due to the reduction in saturation current I0 resulting from the decrease in minority charge density (electrons). Concerning the fill factor, Fig. 10d indicates that FF decreases with increasing absorber thickness at low concentrations (Na < 5 × 1015 cm− 3) caused by the increase in series resistance Rs resulting from the decrease in charge carrier concentration. FF increases for Na > 5 × 1015 cm− 3 due to the improvement in electrical conductivity resulting from the decrease in series resistance (Rs). After 2 μm, the output parameters of the solar cell are almost unchanged due to reaching a balance between light absorption, electrical conductivity, and recombination rates.

For ETL, Fig. 11a and b illustrate solar cell performance variations as the layer thickness and doping concentration ND change between 0.02 and 0.1 μm, as well as between 1017 and 1020 cm− 3, respectively. At thicknesses below 0.04 μm, a slight decrease in Jsc and PCE is observed, possibly due to poor recombination inhibition and an insufficient electrical barrier for efficient charge extraction. The fill factor (FF) is slightly higher when the ETL thickness is raised to 0.06 μm, which is explained by a drop in the device’s series resistance (Rs). Insufficient covering of the absorber surface in extremely thin ETL layers frequently results in non-uniform contact regions, increased conduction resistance, and a higher likelihood of carrier recombination and crystal defects at the ETL/absorber interface. The ETL becomes more consistent and continuous as the thickness gets closer to its ideal value, which improves the quality of interfacial contact as well as charge separation and transport efficiency. A moderate gain in both FF and power conversion efficiency is a result of this structural change, which lowers internal voltage losses and makes it easier for electrons to be extracted towards the front electrode.

After 0.06 μm, solar cell performance stabilizes. Meanwhile, Voc remains almost constant at 1.246 V, indicating that the layer thickness has no effect on the energy barriers or recombination at the ETL/absorber interface. In contrast, simulation results show that increasing doping concentration in the ETL leads to a slight improvement in Jsc, FF, and PCE. This is because the increased doping causes the space charge region to expand toward the absorber layer, enhancing the electric field and thus improving charge separation21. However, Voc remains constant because the increased ND is accompanied by a slight increase in recombination, which balances the effect of the elevated internal potential.

Performance simulation was also conducted by varying the HTL thickness between 0.02 and 0.1 μm, as well as varying the doping concentration NA within the range of 5 × 1017 cm-3 to 5 × 1019 cm-3. The results presented in Fig. 11c and d demonstrate that the impact of these modifications was mostly determined by the amount of doping.

When doping levels are less than 5 × 1018 cm-3, increasing the layer thickness from 0.02 to 0.04 μm resulted in a significant improvement in the output parameters of the solar cell, while no further improvement was observed beyond 0.04 μm. This can be attributed to limited transport occurring at low doping levels due to the scarcity of carriers, making HTL thickness a critical factor in improving transport and reducing loss. At doping concentrations above 5 × 1018 cm-3, the HTL layer thickness had no significant effect on solar cell performance. This is because the good conductivity achieved under this doping condition enables it to operate efficiently regardless of its thickness. Furthermore, a continuous performance improvement was observed with increasing NA up to 5 × 1018 cm-3, after which the performance parameters stabilized. This can be attributed to the increase in free carrier density with higher doping levels, which improves electrical conductivity and reduces resistance. Beyond this, recombination effects may pose a barrier to any further enhancement in performance.

Optimal layer thickness and doping concentrations were selected based on balancing enhanced photocarrier generation with reduced recombination and electrical losses. Specifically, optimal parameters were identified as a CMTS thickness of 2 μm with a doping concentration of 5 × 10¹⁵ cm⁻³, while the ETL and HTL layers have thicknesses of 0.06 μm and 0.02 μm, with doping concentrations of 1 × 10¹⁷ cm⁻³ and 5 × 10¹⁸ cm⁻³, respectively.

Defect density effect

Structural and electronic defects represent key factors affecting the performance of solar cells. These defects can arise during manufacturing processes as a result of the irregularity of the crystalline structure, negatively impacting the conversion of light into electricity. In this section, the effect of defect density in the three layers of the proposed solar cell on its overall performance was analyzed. The defect properties are presented in Table 8, while the defect density was varied from 1010 cm− 3 to 1018 cm− 3 in each layer. The obtained results are presented in Fig. 12.

It was noted that with increasing defect density in the ETL, solar cell performance remained stable up to 1016 cm− 3, where electron transport remained efficient thanks to the high charge carrier concentration and thin layer thickness. After that, a slight decrease in performance was observed due to increased recombination at higher defect concentrations. While stability in solar cell performance was recorded with increasing defect density in the HTL, this may be due to the high doping concentration in this layer (1018 cm− 3), which ensures a sufficient number of free holes, reducing the effect of defects as recombination centers and maintaining charge transport efficiency.

On the other hand, the high density of defects in the CMTS absorber layer leads to a decrease in solar cell performance. The significant impact of these defects becomes apparent when the concentration exceeds 1012 cm− 3, which is the optimal value. After 1012 cm− 3, recombination rates increase, reducing the lifetime and diffusion length of charge carriers, and consequently, decreasing the short circuit current density Jsc due to the loss of an increasing number of electrons and holes before they are extracted. This also leads to a drop in the open circuit voltage Voc as a result of enhanced recombination, as Fig. 13a indicates, which negatively impacts the efficiency QE, as shown in Fig. 13b. In addition, these defects cause an increase in the series resistance Rs, leading to a decline in the fill factor FF and overall efficiency PCE. These outcomes are in excellent agreement with the Shockley–Read–Hall (SRH) model45 and show strong similarity to previous results reported in46.

Temperature effect.

It is important to simulate solar cells under different temperatures to evaluate their performance in various environmental conditions. Solar cells are significantly affected by temperature, with higher temperatures decreasing efficiency due to increased electrical resistance and voltage drop of the cells. Figure 14a shows the effect of temperature changes ranging from 280 to 400 K on the merit factors of the CMTS-based solar cell. A stability in the short circuit current density Jsc was observed with a constant value recorded reaching approximately 23.55 mA/cm², while a decrease in the fill factor FF, open circuit voltage Voc, and efficiency PCE occurred with increasing temperature.

The stability of Jsc is due to the fact that the photocarrier generation process is primarily based on light absorption, which is not significantly affected by thermal changes47. On the other hand, as shown in Fig. 14b, the increase in temperature causes the reverse saturation current I0 to increase due to the increased charge carrier recombination, which lowers Voc and has a detrimental effect on both FF and PCE48.

Front and back contact barrier effect

The back and front contact interfaces have a significant impact on optimizing charge separation and transport. This study analyses the effect of the front and back contact barrier heights on solar cell performance in the varying range from 0.2 to 1.6 eV and from 0.1 to 0.4 eV, respectively. The obtained results are shown in Fig. 15.

From Fig. 15a, it was observed that the solar cell efficiency increased from 8.9 to 25.63% as the back contact barrier increased between 0.2 and 1 eV. Then, it stabilized at 25.82% in the range 1 to 1.45 eV, and finally, at 1.6 eV, the efficiency increased once more to its maximum value of 27.05%.

This is due to the increase in both FF and Voc, following the same behavior as the PCE increase, as shown in Fig. 15b and c, respectively. Meanwhile, a slight change in Jsc was recorded, ranging between 23.31 A/cm2 and 23.56 mA/cm2 (Fig. 15d). The solar cell efficiency was improved by reducing the recombination rate at the absorber/metal interface by incorporating CZTS as HTL. This layer improved the energy band alignment at the back contact, reducing the barriers to hole transport toward the electrode. The short circuit current Jsc remained nearly constant because this barrier affects charge extraction, not charge generation. As long as the properties of the absorber and the front layers remain unchanged, the amount of light absorbed and the number of photogenerated charges remain nearly constant. F. Daoudi et al. reported a similar behaviour of the back contact barrier height effect on CZTS solar cells23.

Figure 15 also indicates that there was no significant effect on solar cell performance when the front contact barrier height was changed from 0.1 to 0.4 eV. This is a consequence of the effective electron transfer from the ETL to the front contact, as the barrier did not degrade electron extraction. Front contact recombination rates also did not change significantly, maintaining Voc constant. Furthermore, increasing the barrier exhibited no effect on the series resistance Rs, contributing to the stability of FF. The short-circuit current Jsc remained constant because light absorption and charge generation in the absorber layer remained unchanged. Since the PCE efficiency depends on the stability of FF, Voc and Jsc, it also remained constant, indicating that the adjustment in the front contact barrier height was not sharp enough to have a significant effect.

Optimized design of CMTS-based solar cell

A conventional CMTS-based solar cell was proposed as a preliminary design. Numerical analyses were then conducted to determine the optimal layers for ETL and HTL. The impact of various geometric and physical parameters on solar cell performance was then analyzed to determine the optimal design that achieves the highest photovoltaic conversion efficiency. Figure 16 shows a comparison of the J-V characteristics of conventional and optimized solar cells, while Table 9 presents the obtained results and compares them with previous studies.

The optimized results showed that the SnS2, CMTS, and CZTS layers had optimal thicknesses of 0.06, 2, and 0.02 μm, respectively, with doping concentrations of 1 × 1017, 5 × 1015, and 5 × 1018 cm− 3, as well as total defect densities of 1 × 1016, 1 × 1012, and 1 × 1017 cm− 3 for each layer. The best solar cell performance was achieved when the back contact barrier height was set at 1.6 eV. This performance improvement is attributed to the enhanced layer interface compatibility, as achieving an effective energy balance reduced recombination and improved charge transport across the interfaces.

Conclusion

This study aims to enhance the photovoltaic efficiency of Cu2MnSnS4-based solar cells by modelling their performance using wxAMPS-1D software. The Al/ITO/WS2/CMTS/SnS/Mo structure was adopted as a preliminary simulation design. Initially, the effect of using different materials as electron and hole transport layers on the solar cell performance was investigated. The results showed that using SnS2 as ETL and CZTS as HTL achieves the best performance, attributed to the good energy alignment between the energy levels of these materials and the CMTS absorber. After selecting the appropriate ETL and HTL, the power conversion efficiency (PCE) increased to 25.63%, compared to the initial solar cell structure, which recorded an efficiency of 19.43%. In the next stage of the study, a comprehensive analysis was conducted on the effect of thickness, doping concentration, and defect density in the various layers of the proposed Al/ITO/SnS2/CMTS/CZTS/Mo structure, as well as how the solar cells total efficiency is affected by temperature and the heights of both the front and back contact barriers. The optimized results showed that the SnS2, CMTS, and CZTS layers had optimal thicknesses of 0.06, 2, and 0.02 μm, respectively, with carrier concentrations of 1 × 1017, 5 × 1015, and 5 × 1018 cm− 3, as well as total defect densities of 1 × 1016, 1 × 1012, and 1 × 1017 cm− 3 for each layer. The highest performance of the solar cell was achieved with the back contact barrier set at 1.6 eV, resulting in an optimized PCE of 27.71%. These comprehensive simulation results form a solid foundation for advancing the development of efficient CMTS-based photovoltaic technologies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

16 October 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23124-6

References

Arif Dar, M. et al. Future photovoltaic applications of nanostructured metal chalcogenides. Comments Inorg. Chem. 1–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/02603594.2025.2464732 (2025).

Green, M. A. et al. Solar cell efficiency tables (version 59). Progress Photovoltaics. 30 (1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/pip.3506 (2022).

Motoshi, N. et al. Cd-Free Cu(In,Ga)(Se,S)2 thin-film solar cell with record efficiency of 23.35%. IEEE J. Photovolt. 9, 1863–1867. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOTOV.2019.2937218 (2019).

Illiyas, C. T. & Preetha, K. C. An investigation on structural, morphological, optical, and electrical properties of copper zinc Tin sulfide (CZTS) thin films prepared by SILAR method. Braz. J. Phys. 54(4), 127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13538-024-01495-x (2024).

Mekhaznia, N. & Zaidi, B. Detailed performance analysis of FTO/TiO2/FAPbI3/CZTS solar cells: computational study. Proc. SPIE 13401, International Conference on Automation and Intelligent Technology (ICAIT 2024), 134010R (2024). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3052232

Zaidi, B. et al. Junction configuration effects on the performance of In2S3/CZTS solar cells. J. Nano- Electron. Phys. 12(1), 01024https://doi.org/10.21272/jnep.12(1).01024 (2020).

Lie, S. et al. Comprehensive physicochemical and photovoltaic analysis of different Zn substitutes (Mn, mg, fe, ni, co, ba, Sr) in CZTS-inspired thin film solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. 10, 9137–9149. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2TA00225F (2022).

Mebrek, H., Zaidi, B., Al-Dmour, H. & Barkhordari, A. Performance evaluation of Cu2SrSnS4 based solar cell: effect of transition metal dichalcogenides buffer layer. Sci. Rep. 15, 6694. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91145-2 (2025).

Khattak, Y. H., Baig, F., Bernabé, M., Beg, S. & Salman, A. Baseline for the numerical analysis of high efficiency copper manganese Tin sulfide Cu2MnSnS4 based thin film solar cell. J. Nanoelectronics Optoelectron. 13, 1678–1684. https://doi.org/10.1166/jno.2018.2421 (2018).

Kowsar, A. et al. Enhanced photoconversion efficiency of Cu2MnSnS4 solar cells by Sn-/Zn-based oxides and chalcogenides buffer and electron transport layers. Sol. Energy 265, 112096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2023.112096 (2023).

Prabhakar, A. R. et al. Photovoltaic effect in Earth abundant solution processed Cu2MnSnS4 and Cu2MnSn(S,Se)4 thin films. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 157, 867–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2016.07.006 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Synthesis and characterization of earth-abundant Cu2MnSnS4 thin films using a non-toxic solution-based technique. Royal Soc. Chem. Adv. 5 https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA14595C (2015).

Donne, A. L., Marchionna, S., Acciarri, M., Cernuschi, F. & Binetti, S. Relevant efficiency enhancement of emerging Cu2MnSnS4 thin film solar cells by low temperature annealing. Sol. Energy. 149, 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2017.03.087 (2017).

Butrichi, F. et al. Wet synthesis of Cu2MnSnS4 thin films for photovoltaics: oxidation control and cds impact on device performances. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 272(13), 112924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2024.112924 (2024).

Yali, S. et al. A promising photovoltaic material Cu2MnSn(S,Se)4: film growth and its application in solar cell. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 219, 110788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2020.110788 (2021).

Pansuriya, T., Malani, R. & Kheraj, V. Investigations on the effect of buffer layer on CMTS based thin film solar cell using SCAPS 1-D. Opt. Mater. 126, 112150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2022.112150 (2022).

Isha, A. et al. High efficiency Cu2MnSnS4 thin film solar cells with SnS BSF and cds ETL layers: A numerical simulation. Heliyon 9(5), 15716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15716 (2023).

Chowdhury, T. A. SCAPS modeling of CMTS solar cell with ZrS2 buffer layer. Acta Phys. Pol., A. 145, 215–224. https://doi.org/10.12693/APhysPolA.145.215 (2024).

Muhammad, A. J., Salih, A. I. & Fadel, G. Numerical analysis of graded band gap CZT(S,Se) solar cells using AMPS-1D. Int. J. Electr. Eng. (IIJEE). 4 (10), 28–36 (2016).

Hadjab, M. et al. Hadj larbi, A. A numerical optimization study of cds and Mg0.125Zn0.875O buffer layers in CIGS-based solar cells using wxAMPS-1D package. Int. J. Model. Simul. 40, 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/02286203.2020.1857129 (2020).

Bencherif, H., Dehimi, L., Mahsar, N., Kouriche, E. & Pezzimenti, F. Modeling and optimization of CZTS kesterite solar cells using TiO2 as efficient electron transport layer. Mater. Sci. Engineering: B 276, 115574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2021.115574 (2022).

Kearney, K. & Rockett, A. Simulation of charge transport and recombination across functionalized Si(111) photoelectrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 163, 598–604. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.1331607jes (2016).

Daoudi, F. et al. Investigations on the optimization of contacts barrier height for the improved performance of zno/cds/czts solar cells. Energy Eng. 120, 1803–1815. https://doi.org/10.32604/ee.2023.028423 (2023).

Kabir, M. R. et al. A comprehensive SCAPS-1D simulation study on the photovoltaic properties and efficiency enhancement of CH3NH3PbCl3 perovskite solar cells. Eng. Res. Express 7, 015319. https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-8695/ada721 (2025).

Chandrama, G., Sanjay, K. S. & Alok, K. P. Numerical simulation of CuSbS2 solar cell with WS2 used as buffer layer and MoTe2 hole transport layer for high efficiency. Procedia Environmental Science, Engineering and Management 10(1) 213–220 (2023).

Abbas, K. & Bahrami, A. Investigating the Potential of WO3 and WS2 As Cd-Free Buffer Layers in Sb2Se3-Based Thin-Film Solar Cells: A Numerical Study with Scaps-1d Software. Available at SSRN (2024). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4700811

Mir Kazem, O., Mehran, M., Nafiseh, M. & Kim, D. H. Improve the performance of CZTSSe solar cells by applying a SnS BSF layer. Solid State Electron. 141, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sse.2017.12.004 (2018).

Atowar, A. Design and simulation of a high-performance Cd-free Cu2SnSe3 solar cells with SnS electron-blocking hole transport layer and TiO2 electron transport layer by SCAPS-1D. SN Appl. Sci. 3, 253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-021-04267-3 (2021).

Otmani, R., el Manouni, A. & Almaggoussi, A. Numerical simulation of CZTSe based solar cells using different back surface field layers: improvement and comparison. J. Electron. Mater., 50 doi: (2021).

Ranade, P. et al. Molybdenum as a gate electrode for deep Sub-Micron CMOS technology. MRS Proc. 611, 321. https://doi.org/10.1557/PROC-611-C3.2.1 (2011).

Merzouk, C. E. H., Bensmaine, S., Ghalmi, L. & Aissa, A. Comparative study by simulation Betweentwo structures cds/czts and zns/czts via SCAPS-1D software. Chalcogenide Lett. 21, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.15251/CL.2024.212.113 (2024).

Bendib, T. et al. Combined optical-electrical modeling of perovskite solar cell with an optimized design. Opt. Mater. 109, 110259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2020.110259 (2020).

Adamu, D., Tyagi, A. & Kar, K. Numerically investigating the AZO/Cu2O heterojunction solar cell using zno/cds buffer layer. Optik 228, 166228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2020.166228 (2020).

Alia, H. T. et al. A simulation study of perovskite based solar cells using CZTS as HTM with different electron transporting materials. J. Ovonic Res. 17, 437–445 (2021).

Huang, R. & Tang, J. Simulation studies on the electron transport layer based perovskite solar cell to achieve high photovoltaic efficiency. J. Phys: Conf. Ser. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2083/2/022011 (2021).

Bhavsar, K. & Lapsiwala, P. B. Numerical simulation of perovskite solar cell with different material as electron transport layer using SCAPS-1D software. Optoelectron. Optoelectronic Devices. 24, 341–347. https://doi.org/10.15407/spqeo24.03.341 (2021).

Dena, N. Q. A. & Qais, T. A. The influence of the conduction band engineering on the perovskite solar cell performance. Results Opt. 9, 100291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rio.2022.100291 (2022).

Latrous, A. R., Mahamdi, R., Touafek, N. & Pasquinelli, M. Conduction band offset effect on the Cu2ZnSnS4 solar cells performance. Annales de Chimie - Science des Matériaux, 45, 431–437 (2021). https://doi.org/10.18280/acsm.450601

Salomé, P., Malaquias, J., Fernandes, P. & da Cunha, A. F. Mo bilayer for thin film photovoltaics revisited. J. Phys. D 43, 345501. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/43/34/345501 (2010).

Li, Z. Q., Ni, M., Feng, X. D. & & Simulation of the Sb2Se3 solar cell with a hole transport layer. Mater. Res. Express. 7, 016416. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ab5fa7 (2020).

Teimouri, R. & Mohammadpour, R. Potential application of CuSbS2 as the hole transport material in perovskite solar cell: A simulation study. Superlattices Microstruct. 118, 116-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spmi.2018.03.079 (2018).

Azri, F., Meftah, A., Sengouga, N. & Meftah, A. Electron and hole transport layers optimization by numerical simulation of a perovskite solar cell. Sol. Energy 181, 372-378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.02.017 (2019).

Kumar, A. & Ranjan, P. Computational analysis of chalcogenides as an inorganic hole transport layer in perovskite solar cells. Opt. Quant. Electron. 53, 511 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-021-03186-2 (2021).

Khattak, Y. H., Baig, F., Toura, H., Beg, S. & Bernabé, M. S. CZTSe kesterite as an alternative hole transport layer for MASnI3 perovskite solar cells. J. Electron. Mater.48, 5723-5733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-019-07374-5 (2019).

Das, B., Aguilera, I., Rau, U. & Kirchartz, T. What is a deep defect? Combining Shockley-Read-Hall statistics with multiphonon recombination theory. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 024602. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.4.024602 (2020).

Bouri, N. et al. CH3NH3Pb1 – xCuxI3-based solar cell: numerical study and optimization with different inorganic hole transport layers. Chem. Phys. Impact. 10, 100873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chphi.2025.100873 (2025).

Ghosh, S., Yasmin, S., Ferdous, J. & Saha, B. Numerical analysis of a CZTS solar cell with MoS2 as a buffer layer and graphene as a transparent conducting oxide layer for enhanced cell performance. Micromachines 13(8), 1249. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13081249 (2022).

Bencherif, H., Dehimi, L., Pezzimenti, F. & Della Corte, F. G. Improving the efficiency of a-Si:H/c-Si thin heterojunction solar cells by using both antireflection coating engineering and diffraction grating. Optik 182, 682–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2019.01.032 (2019).

Tripathi, S., Kumar, S., Dwivedi, D. K. & B. & Numerical simulation of non-toxic In2S3/SnS2 buffer layer to enhance CZTS solar cells efficiency by optimizing device parameters. Optik 227, 166087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2020.166087 (2021).

Dakua, P. K. et al. De. Evaluating CZTS solar cell performance based on generation and recombination models for possible ETLs through numerical analysis. J. Electron. Mater. 53, 2015–2025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-024-10930-3 (2024).

Chowdhury, T. SCAPS modeling and performance analysis of AZO/SnS2/CZTS solar cells. Optik Continuum. 3, 1341–1368. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTCON.527415 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All Authors contributed equally and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional Information

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in Table 9. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahsar, N., Zaidi, B., Dehimi, L. et al. The performance of Cu2MnSnS4 based solar cells with CZTS as hole transport nanolayer. Sci Rep 15, 26774 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12766-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12766-1