Abstract

Breast cancer is characterized by the unchecked proliferation of breast cells. Variations in the metabolism of steroid hormones can influence the risk of this disease by modifying the concentration and the potency of these hormones. The enzyme AKR1C4, primarily found in the liver, is crucial for regulating these hormone levels in the bloodstream. This research examined the relationship between a polymorphic variant (rs17134592) of the AKR1C4 gene and the susceptibility to breast cancer among the Bangladeshi population. A case-control study was conducted with 310 breast cancer patients and 310 healthy individuals from Bangladesh. DNA was extracted using an organic process, followed by genotyping through the PCR-RFLP technique. To validate the accuracy of genotyping results, a subset of PCR products was randomly selected and confirmed using Sanger sequencing. Statistical assessments were conducted to analyze the association of polymorphism, while molecular dynamics simulation and diverse computational methods were employed to predict the structural and functional impacts of the SNP. The results indicate that rs17134592 in the AKR1C4 gene is linked with a heightened risk for breast cancer (p < 0.0001, OR = 3.39, 95% CI = 1.80 to 6.50 for the GG genotype in additive model 2). The recessive model (GG vs. CC + CG) also showed an enhanced risk of susceptibility to breast malignancy (p < 0.0001, OR = 3.25, 95% CI = 1.78 to 6.08). In the subgroup of post-menopausal women, the risk of developing breast cancer was significantly higher for carriers of the GG genotype, with relative risks of 4.02 and 3.92, in the additive model 2 and recessive model, respectively. However, no significant correlations were observed between these genotypes and tumor grade or size in breast cancer patients. Computational analysis suggested that the L311V mutation (rs17134592) could potentially reduce the stability of the protein. Additionally, molecular dynamics simulations indicated that the L311V mutation introduces notable conformational instability to the AKR1C4 enzyme, potentially impacting its biological functionality and catalytic efficiency. In conclusion, the genetic variant rs17134592 has been identified as significantly correlated with the prevalence of breast cancer in the Bangladeshi population. Computational studies suggest that the L311V mutation in the AKR1C4 gene, corresponding to rs17134592, results in marked conformational instability and changes in enzyme functionality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer, the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women globally, primarily originates from duct-lining cells, with some arising from lobular linings or other tissues1,2,3. According to the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) 2022, breast cancer is the most common cancer among women, accounting for 23.8% of newly diagnosed female cancer cases worldwide (https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/900-world-fact-sheet.pdf). In Bangladesh, the 2022 GLOBOCAN report recorded 12,989 new breast cancer cases and 6,162 deaths, ranking it fourth in incidence and sixth in cancer-related mortality in the country (https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/50-bangladesh-fact-sheet.pdf). Early identification of breast cancer risk factors is crucial for screening and improving outcomes through timely treatment. Higher incidences in developed countries are linked to factors like early menarche, late first childbirth, nulliparity, obesity, alcohol consumption, sedentary lifestyle, and reduced breastfeeding4. In addition to these, dietary factors and trace elements also contribute to breast cancer risk. Elements like selenium, zinc, and copper affect oxidative stress and DNA damage5, while dietary patterns influence hormone metabolism and inflammation6. The polymorphism of proteins influencing these factors can significantly affect susceptibility7. Identifying genetic markers can lead to personalized therapies tailored to genetic risk profiles8.

Many research highlighted the critical role of genetics in different diseases9,10 and as breast cancer, with 5–10% of cases attributed to hereditary factors11. Key genes like BRCA1 and BRCA2 significantly increase breast cancer risk12, along with other genes such as PALB2, TP53, PTEN, CDH1, CHEK2, and ATM, contributing to varying susceptibilities13,14. These genes often exhibit an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Gene alterations in MYC, ERBB2, FGFR1, GATA315, and AKR1C416 also play pivotal roles in early cancer progression, with AKR1C4 associated with increased mammographic percent density, a significant breast cancer risk factor17. The Aldo-keto reductase (AKR) superfamily is divided into 15 families, with human AKRs primarily found in AKR1, AKR6, and AKR7. The AKR1 family includes 6 subfamilies (AKR1A to AKR1G), with the AKR1C subfamily containing 25 enzymes, four of which are from human (AKR1C1 to AKR1C4)18,19,20,21.

The AKR1C4 enzyme, encoded by the AKR1C4 gene on chromosome 10 between positions p15 and p14, spans approximately 20 kb and comprises nine exons. The predominant AKR1C4 transcript measures about 1.3 kb, and the protein has a molecular weight of roughly 37 kDa, with 323 amino acids and the characteristic (α/β)8 barrel structure typical of the AKR1C family22,23. Human AKR1C1–AKR1C4 enzymes are versatile hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (HSDs) with functions including 3α-, 17β-, and 20α-HSD, based on enzyme type and conditions20,24. Specifically, AKR1C4 primarily functions as a 3α-HSD with some 3β-HSD activity20. Figure 1 presents that in the liver, AKR1C4 collaborates with 3-oxo-5α-steroid-4-dehydrogenase (5α-reductase) to convert 5α-dihydrosteroids into 5α-tetrahydrosteroids, essential for the second phase of steroid hormone metabolism with a Δ4-3-ketosteroid structure, thereby regulating steroid hormone levels25,26,27. As a specific example, in both the classical and alternative pathway, AKR1C4 converts 5α-dihydrotestosterone (5α-DHT) into 5α-androstane-3α,17β-diol (3α-diol), and 5α-androstane-3β,17β-diol (3β-diol) which undergo glucuronidation and sulfation for excretion28,29,30,31,32. Notably, 3β-diol serves as an estrogen receptor β (ERβ) ligand, inducing anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects33,34. Furthermore, in the backdoor pathway, AKR1C4 and 5α-reductase catalyze the conversion of progesterone (P) to 5α-pregnane-3,20-dione (5αP) and the subsequent reduction of 5αP to 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one (allopregnanolone), which is further transformed to 3α-diol by AKR1C3 for the excretion35,36,37. These activities highlight AKR1C4’s critical role in detoxifying excess steroid hormones in the liver32,38.

Steroid hormone metabolism pathways involving AKR1C4. This schematic illustrates the involvement of AKR1C4 in key steroid hormone metabolism pathways, including the backdoor pathway, classical pathway, and alternative pathway. AKR1C4 plays a crucial role in converting 5α-pregnane-3,20-dione to 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one in the backdoor pathway while also contributing to the conversion of 5α-dihydrotestosterone to 5α-androstane-3α,17β-diol in the classical and alternative pathways. These metabolic processes influence the balance of active androgens and estrogens, which are key regulators of breast tissue homeostasis and have implications for breast cancer development.

So far mentioned above, AKR1C4 plays a crucial role in inactivating 5α-DHT, a molecule linked to cell proliferation39, and converts it into 3α-diol and 3β-diol28,29,30,31,32, and 3β-diol has antiproliferative and apoptotic effects in estrogen-sensitive tissues like breast tissue through ERβ receptor interaction34,40. Additionally, AKR1C4 reduces 5αP35,36,37, a metabolite that selectively upregulates estrogen receptor expression in estrogen-sensitive tissues, promoting cancer development, particularly in breast tissue41. Given its role in metabolizing these steroids that affect cell proliferation and cancer progression, understanding the impact of SNPs on AKR1C4’s function is vital for its potential as a cancer marker.

Multiple SNPs in the AKR1C4 gene, found in coding and non-coding regions, are associated with various diseases and physiological traits in individuals of European descent, including metabolite ratios42, triglyceride levels43,44,45,46, and hemoglobin levels47, as revealed by molecular epidemiology studies37,48. GWAS identified specific variants near AKR1C4, such as rs79717793 and rs7475279, that affect testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin levels49. The rs17134592 (C931G) variant leads to a leucine to valine shift at position 311 (L311V), reducing enzymatic activity by 66–80% and catalytic efficiency50. Moreover, women with the low-activity Val allele of AKR1C4 experience greater increases in mammographic percent density after estrogen-progestin therapy than those with the Leu allele, indicating a heightened breast cancer risk16.

This research aims to evaluate the C931G (rs17134592) variant as a potential risk factor by comparing healthy females and breast cancer patients in Bangladesh. Additionally, it seeks to identify any structural and functional changes in the AKR1C4 enzyme linked to this polymorphism (rs17134592) using computational techniques such as molecular dynamics simulation and molecular docking.

Materials and methods

Study participants

This study was conducted as a population-based case-control investigation, in which individuals diagnosed with breast cancer were identified as cases, and healthy individuals with no prior history of breast cancer or other chronic conditions served as controls. The research included 620 participants, equally divided into 310 breast cancer patients (cases) and 310 age-similar healthy individuals (controls). The ethical review committee of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology approved the study at the University of Dhaka (Ref. No. BMBDU-ERC/EC/23/014). In addition, we confirm that all methods used in this study were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations. Patients were enrolled at the National Institute of Cancer Research & Hospital (NICRH) in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where diagnoses were confirmed through various methods, including mammograms, breast ultrasounds, biopsies, and breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); all participants in this group were female. Controls were sourced from the National Institute of Ear, Nose, and Throat (NIENT) in Dhaka, Bangladesh, comprising females without any cancer history.

Participants were informed about the nature of the study and experimental procedures. Informed written consent was obtained from all the study subjects before the samples were collected. All participants received a comprehensive explanation of the research and its procedures before providing their written consent to participate. Data collection involved detailed sociodemographic information such as age, body measurements, household income, place of residence, educational background, medical history, details regarding menstrual and reproductive aspects, and familial cancer incidence collected via a standardized questionnaire. Additionally, cases were required to provide extensive information about their breast cancer diagnosis, including the grade and size of tumors, age at diagnosis, prescribed treatments, total white blood cell (WBC) count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and the status of key biomarkers like progesterone receptor (PR), estrogen receptor (ER), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).

Sample collection

Trained phlebotomists extracted five milliliters (5 mL) of venous blood from each participant using a single-use syringe, adhering to all sterile techniques. This blood was subsequently placed into vacutainer tubes that contained ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Following this, plasma was isolated by centrifuging at 3,000 rpm for 15 min. The plasma and cellular components were preserved at -20 °C for subsequent analysis.

Genotyping of rs17134592

DNA was isolated from cellular fractions using the organic extraction method. To identify the genotypes of rs17134592, polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) analysis was performed. The following is a detailed description of the procedure:

A 15µL reaction mixture for PCR was prepared in a PCR tube, which included 7.5µL of GoTaqG2 Green Master Mix (Promega Corporation), 5.05µL of nuclease-free water, 0.45 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 0.5µL of both forward and reverse primers, and 1.00µL of the isolated DNA. The sequences of the forward and reverse primers were F: 5′-GACCCTGTGTAGTTTGTGTGA-3′ and R: 5′-AGCAGGAGGGGAGGGATTT-3′, respectively. The primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table S1, and the conditions for the PCR reaction are also listed in Supplementary Table S2.

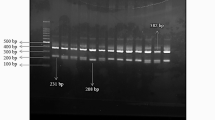

The BtsIMutI restriction enzyme was used to digest a 402 bp PCR product in a 15µL reaction incubated for 16 h at 55 °C. This produced two fragments, 245 bp, and 157 bp when the mutant G allele was present. No cleavage occurred in wild-type homozygous C/C genotype cases, leaving intact 402 bp fragments. Three distinct bands were observed for the heterozygous C/G genotype: 402 bp, 245 bp, and 157 bp. Conversely, the mutant-type homozygous G/G genotype yielded only two bands, 245 bp, and 157 bp, as shown in Fig. 2. These bands were subsequently stained with ethidium bromide, separated, and visualized on a 2% agarose gel electrophoresis using ultraviolet light.

Representative restriction enzyme-digested products of rs17134592 (C931G) on 2% agarose gel. The presence of only 402 bp on the (from left) 3rd, 5th, 6th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 12th ,14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th wells indicates the existence of the homozygous wild-type C/C genotype. The 402 bp, 245 bp, and 157 bp on lanes 2nd, 4th, 11th, and 13th indicate the existence of heterozygous mutant C/G genotype. In comparison, 245 bp and 157 bp on lane 7th indicate the homozygous mutant G/G genotype. The first lane (from left) contains a 100 bp DNA ladder.

Sequencing of PCR products

To validate the genotyping results obtained through the PCR-RFLP method, 10% of the PCR products were selected randomly from both case and control groups for sequencing. The sequencing was performed using the Sanger sequencing method, specifically employing Barcode-tagged Sequencing (BTSeq) technology. The resulting chromatograms were analyzed with Geneious Prime software (version 2022.2) to ensure the accuracy of the genotyping.

Statistical analyses

The required sample size for this study was estimated using the G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7)51,52, considering a Type I error rate (α) of 5% and a statistical power (1-β) of 80%. Based on this calculation, a minimum of 308 participants was required for both the case and control groups. To enhance the robustness of the analysis, we ultimately included 310 individuals in each group. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.1.2) and IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25). Quantitative variables, such as age, total WBC count, ESR, and body mass index (BMI), were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). In contrast, categorical variables were presented as percentages. The Shapiro-Wilk test assessed whether the quantitative variables followed a normal distribution. As age, BMI, total WBC count, and ESR values did not follow a normal distribution, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the mean ± SD values between cases and controls for each variable. Associations among categorical variables were analyzed using the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to determine risk levels. A p-value < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant for all tests. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) analysis was performed using the “SHEsisPlus” web-based platform (http://shesisplus.bio-x.cn/SHEsis.html)53,54.

In-silico analysis

Various in silico analysis tools were utilized following the methodologies outlined in our previously published research55,56,57. For example, the functional impact of the SNP on the protein was predicted using Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT)58 (https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/) and Polymorphism Phenotyping v2 (PolyPhen-2)59 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/). Tools such as PredictSNP60 https://loschmidt.chemi.muni.cz/predictsnp/), SNAP61, and PhD-SNP62 (https://snps.biofold.org/phd-snp/phd-snp.html), along with MAPP63 (http://mendel.stanford.edu/SidowLab/downloads/MAPP/index.html), were employed to assess the association of SNP with diseases. Additionally, the stability of the protein affected by this polymorphism was evaluated using MUpro64 (https://mupro.proteomics.ics.uci.edu/) and Impact of Nonsynonymous Mutations on Protein Stability – Multi Dimension (INPS-MD)65 (https://inpsmd.biocomp.unibo.it/inpsSuite/). The HOPE database (https://www3.cmbi.umcn.nl/hope/) was employed to analyze various alterations in protein structure resulting from amino acid substitutions66. Utilizing SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/)67, a 3D model of the mutated protein was constructed, employing the 2FVL template from PDB (https://www.rcsb.org/)68. SWISS-MODEL was selected for this study due to its well-established reliability in template-based homology modeling, mainly when high-quality structural templates are available. SWISS-MODEL also offers detailed quality assessment metrics such as GMQE and QMEAN scores. These provide essential confidence evaluation when interpreting model reliability — features directly relevant to studying polymorphism-induced structural changes. The constructed model was subjected to validation using Swiss-Model assessment, PROSA (https://prosa.services.came.sbg.ac.at/prosa.php)69, and ERRAT (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/)70.

Molecular Docking analysis

To investigate the impact of the L311V polymorphism on the binding interactions of AKR1C4 with NADPH, molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina71, followed by 2D interaction analysis in Discovery Studio Visualizer (version 24.1.0.23298). Docking simulations were conducted for wild-type (Leu311) and mutant (Val311) AKR1C4 proteins, with grid parameters optimized to encompass the active site cavity. The exhaustiveness parameter was set to 16 to enhance docking accuracy. The top-ranked NADPH binding poses were analyzed, and 2D interaction diagrams were generated to visualize key ligand-protein interactions. Hydrogen bonding patterns, hydrophobic contacts, and electrostatic forces were compared between wild-type and mutant AKR1C4-ligand (NADPH) complexes to assess structural differences in ligand binding.

Molecular dynamics simulations

The ligand-protein complexes were subjected to a 100 nanoseconds molecular dynamics simulation using the GROningen machine for chemical simulation (GROMACS) (version 2020.6)72. The CHARMM36m force field was applied for the simulation, with a water box generated around the protein surface, positioned 1 nm away at each corner, employing the TIP3 water model. To maintain system neutrality, appropriate ions were added. After energy minimization, isothermal isochoric (NVT) equilibration, and isobaric (NPT) equilibration of the system, a simulation of 100 nanoseconds duration was executed under periodic boundary conditions, utilizing a temporal integration step of 2 fs. The trajectory data was analyzed with a snapshot interval of 100 picoseconds, employing the rmsd, rmsf, gyrate, sasa, and H-bond packages integrated within GROMACS to evaluate root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration (Rg), and solvent accessible surface area (SASA). Plots illustrating the outcomes of these analyses were generated using the ggplot2 program within RStudio. All molecular dynamic simulations were conducted at the Bioinformatics Division of the National Institute of Biotechnology, utilizing high-performance simulation stations running the Ubuntu 20.04.4 LTS operating system.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the patients

Among the 310 patients included in this study, 79.03% had no previous family history of cancer. Most of the patients (82.90%) were housewives by profession. The majority of the patients (70.65%) resided in the rural areas of Bangladesh, which is reflected by their family income. 78.39% of the patients had family income lower than 20,000 BDT, and 11.29% had no formal education, with 24.84% and 40.65% having primary and secondary education, respectively. The demographic characteristics are shown in Fig. 3.

Demographic characteristics of the breast cancer patients enrolled in the study. Panel (a) presents the family history of cancer among the patients, panel (b) depicts their residential areas, panel (c) illustrates the patients’ occupations, panel (d) outlines the patients’ monthly family income range, and panel (e) details the educational levels of the patients.

Baseline characteristics of the study subjects

Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of the study subjects, including age, BMI, menstrual status, age at menarche, and number of pregnancies. The findings reveal significant differences in age at menarche and BMI between breast cancer patients and healthy controls. In contrast, no significant differences were observed in age, BMI groups, menstrual status, and number of pregnancies.

Clinicopathological data of breast cancer patients

As shown in Table 2, 72.58% of patients were diagnosed with cancer after the age of 40 years. The majority (96.13%) of cases were classified as invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), with only 12 (3.87%) cases of invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) reported. Regarding hormone receptor status, all patients tested positive for ER and PR, while 52.26% were HER2 positive. Additionally, 63.87% of patients exhibited tumor sizes ranging from 2 to 5 cm, and 59.35% had tumors classified as grade 2 (G2).

Genotypic distribution of AKR1C4 rs17134592 polymorphism and the risk of developing breast cancer

Table 3 illustrates the association and frequencies of various genotypes of rs17134592 with breast cancer risk, analyzed using different genetic models and presented through OR with 95% CI and significance levels. Among the study participants, control subjects exhibited genotype frequencies of 59.68% for homozygous wild type (CC), 35.48% for heterozygous (CG), and 4.84% for homozygous mutant (GG). In contrast, in breast cancer patients, the frequencies were 51.62% for homozygous wild type (CC), 34.19% for heterozygous (CG), and 14.19% for homozygous mutant (GG), indicating a higher prevalence of the homozygous mutant genotype among patients. The mutant allele G exhibited a frequency of 22.58% in controls and 31.29% in breast cancer patients.

In the additive model 1 (CG vs. CC), the frequency of the heterozygous genotype (CG) was 37.29% in controls and 39.85% in cases, showing no statistically significant association with breast cancer risk (p = 0.54; OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.79 to 1.56). In contrast, the additive model 2 (GG vs. CC) revealed a statistically significant association with breast cancer susceptibility (p < 0.0001; OR = 3.39, 95% CI = 1.80 to 6.50). In the dominant model (CG + GG vs. CC), the combined frequency of heterozygous and homozygous mutant genotypes (CG + GG) was 48.39% in cases and 40.32% in controls, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.05; OR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.91). Conversely, the recessive model (GG vs. CC + CG) demonstrated a strong and statistically significant association with breast cancer risk (p < 0.0001), with the homozygous mutant genotype (GG) being significantly more frequent in cases (14.19%) compared to controls (4.84%), resulting in an OR = 3.25 (95% CI = 1.78 to 6.08). Finally, in the allelic model (G vs. C), the mutant G allele was significantly enriched in cases (31.29%) compared to controls (22.58%), demonstrating a significant association with breast cancer risk (p = 0.0007; OR = 1.56, 95% CI = 1.21 to 2.01).

In Fig. 4, the genotypic distribution of rs17134592 is shown.

Genotypic distribution of rs17134592 in study subjects. The CC genotype was the most frequently observed in both groups, with a frequency of 59.68% in controls and 51.62% in breast cancer patients. The CG genotype was found in 35.48% of controls and 34.19% of cases. The GG genotype was the least frequent in both groups, but appeared at a higher proportion in cases (14.19%) compared to controls (4.84%), indicating a possible association between the GG genotype and breast cancer risk.

Confirmation of RFLP genotyping results by sequencing

To confirm the accuracy of PCR-RFLP genotyping, selected PCR products for rs17134592 were sequenced using the Sanger method (BTSeq), which successfully validated the CC, CG, and GG genotypes. As shown in Fig. 5, the CC genotype displayed a single peak for cytosine (C) at the polymorphic site, the CG genotype showed overlapping peaks for both cytosine (C) and guanine (G), and the GG genotype exhibited a single peak for guanine (G). This 100% concordance between sequencing and PCR-RFLP results supports the reliability of the genotyping approach used in this study.

Sequencing chromatograms confirming genotypes at rs17134592. Representative Sanger sequencing chromatograms demonstrate the three genotypes observed for rs17134592 in the AKR1C4 gene. The CC genotype shows a single peak for cytosine (C) at the polymorphic site, the CG genotype exhibits overlapping peaks for cytosine (C) and guanine (G), and the GG genotype presents a single peak for guanine (G).

Distribution of AKR1C4 rs17134592 (C931G) genotypes in the study subjects according to menopausal status

Table 4 presents the genotypic distribution of rs17134592 polymorphism and its association with breast cancer risk, stratified by menopausal status. In this study, participants were categorized into pre-menopausal and post-menopausal groups to analyze the risk of breast cancer development. Among post-menopausal women, a significant association was found between the rs17134592 polymorphism and increased breast cancer risk. Specifically, carriers of the GG genotype (in the additive model 2) exhibited a 4.02-fold higher risk of breast cancer compared to those with the CC genotype (OR = 4.02, 95% CI = 1.77 to 8.62, p = 0.0004). Similarly, the recessive model showed that carriers of the GG genotype had a 3.92-fold higher risk compared to those with the CC + CG genotypes (OR = 3.92, 95% CI = 1.80 to 8.35, p = 0.0006). Conversely, no significant association between genotype and breast cancer risk was observed in pre-menopausal women.

Association of the rs17134592 (C931G) with tumor grade and tumor size in breast cancer patients

In the patient group, associations of the rs17134592 (C931G) polymorphism with tumor size and grade were analyzed. The results are presented in Tables 5 and 6. Both tables showed that the alternate allele (G) was not significantly associated with either tumor size or grade.

Assessment of constancy in genotype frequency

Table 7 presents the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) test results, assessing the constancy of genotype frequency in study subjects. The control group was in HWE (χ² = 0.038, p = 0.98), indicating that genotype distribution followed expected population proportions. Conversely, the case group deviated significantly from HWE (χ² = 13.50, p = 0.0012), suggesting a potential association between the rs17134592 polymorphism and breast cancer risk. When both groups were analyzed, the genotype distribution also showed significant deviation from HWE (χ² = 8.58, p = 0.0034), primarily influenced by the case group.

Total WBC count and ESR in study subjects

Breast cancer patients exhibited significantly higher (p-value < 0.0001) total WBC counts compared to the control group, with a mean ± SD count of 10,328 ± 1653 cells/mm³ versus 8333 ± 1010 cells/mm³ in controls. The comparative data between the two groups is illustrated in Fig. 6.

Box-and-whisker plot comparing total WBC counts between breast cancer patients (Case) and healthy controls (Control). The breast cancer group showed significantly higher WBC counts (p < 0.0001), with individual dots representing values beyond the 10th (lower limit) to 90th (upper limit) percentile range.

Additionally, the ESR was markedly elevated in breast cancer patients, with a mean ± SD of 43.37 ± 17.20 mm in the first hour, compared to 18.09 ± 5.83 mm in healthy controls. These findings are shown in Fig. 7.

In-silico analysis of the effects of rs17134592 on the AKR1C4 protein

Determination of the functional consequences of rs17134592 (L311V)

Various computational tools were employed to evaluate the impact of the L311V mutation on protein functionality. All assessments indicated that the L311V mutation is either tolerated or neutral. Notably, MUpro and INPS-MD suggested a reduction in protein stability due to this mutation. These findings are summarized in Table 8, and the detailed scores from different web-based tools are available in Supplementary Table S3.

Furthermore, the HOPE server analyzed various properties affected by amino acid substitution. The mutation (L311V) introduced an amino acid that differed in size but not in charge or hydrophobicity. This change in amino acid structure reduced interactions and disrupted hydrogen bonding. Key results from the HOPE analysis are summarized in Supplementary Table S4.

Homology modeling

The three-dimensional configuration of the human AKR1C4 protein was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The FASTA sequence of AKR1C4 was utilized to construct the 3D structure of its mutant variant L311V, using PDB-ID 2FVL as a template. The resultant models were evaluated using tools such as the SWISS-MODEL structure assessment tool, ProSA-web, and ERRAT, all of which confirmed the high quality of the models. The evaluation scores from these tools are detailed in Supplementary Table S5.

Protein–ligand Docking analysis

The binding affinity between the native and mutant forms of the protein-ligand complex varies. In particular, the interaction of the wild-type AKR1C4 protein with its ligand, NADPH, shows a binding energy of -11.1 kcal/mol. When paired with NADPH, this energy decreases to -7.2 kcal/mol in the mutant Val311 AKR1C4 variant.

The 2D interaction plots for wild-type (Leu311) and mutant (Val311) AKR1C4-NADPH complexes are presented in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively. These visualizations provide a comparative assessment of ligand-protein interactions, demonstrating how the L311V mutation alters binding interactions within the active site. In the wild-type AKR1C4-NADPH complex (Fig. 8), NADPH forms multiple conventional hydrogen bonds with key residues, including Lys270, Asn280, Glu279, Gln222, Tyr55, Asn167, Ser217, and Arg276, contributing to ligand stabilization. Additionally, Pi-alkyl and Pi-Pi stacking interactions further enhance the binding affinity by reinforcing hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions within the active site.

2D interaction plot of wild-type (Leu311) AKR1C4 complexed with NADPH. The diagram illustrates the molecular interactions between NADPH and the wild-type AKR1C4 (Leu311) within the active site. Key conventional hydrogen bonds are formed with Lys270, Asn280, Glu279, Gln222, Tyr55, Asn167, Ser217, and Arg276, stabilizing the ligand within the binding pocket. Additional Pi-alkyl and Pi-Pi stacking interactions further enhance ligand binding.

In contrast, the mutant (Val311) AKR1C4-NADPH complex (Fig. 9) exhibits notable alterations in hydrogen bonding patterns and electrostatic interactions. The substitution of Leu311 with Val appears to shift the ligand’s hydrogen bonding network, introducing new interactions with Thr221, Leu219, His117, Tyr23, and Tyr24 while maintaining some existing contacts with Lys270, Arg276, and Tyr55. However, the number of hydrogen bonds is reduced, particularly at Lys270, where two conventional hydrogen bonds are lost. Additionally, the mutant complex exhibits fewer Pi-alkyl and Pi-Pi interactions, which may suggest a weakened binding affinity or altered ligand orientation compared to the wild-type complex. Notably, the mutant complex also introduces unfavorable donor-donor and acceptor-acceptor interactions, particularly involving Ser217, Arg276, and Asp50, which may contribute to steric hindrance and reduced ligand stability.

2D interaction plot of mutant (Val311) AKR1C4 complexed with NADPH. The L311V mutation alters NADPH binding by introducing new interactions with Thr221, Leu219, His117, Tyr23, and Tyr24, while retaining Lys270, Arg276, and Tyr55. The hydrogen bond count is reduced, particularly at Lys270, and fewer Pi-alkyl and Pi-Pi interactions suggest weakened ligand binding. Additionally, unfavorable donor-donor and acceptor-acceptor interactions involving Ser217, Arg276, and Asp50 may contribute to steric hindrance and reduced ligand stability.

Molecular dynamics simulation

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the wild-type AKR1C4 and the mutant (L311V) AKR1C4

The RMSD value of the wild (blue line) AKR1C4 (complexed with ligand, NADPH) was < 0.2 nm from ~ 50 ns to ~ 75 ns, whereas the mutant (red line) AKR1C4 (complexed with ligand, NADPH), showed > 0.2 nm (Fig. 10). A major conformational change occurred before 50 ns for wild AKR1C4 and mutant AKR1C4. After 50 ns, the mutant AKR1C4 showed higher RMSD values.

Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of wild AKR1C4 and mutant (L311V) AKR1C4

In the case of the mutant (L311V) (red line) AKR1C4 (complexed with ligand, NADPH), from the ~ 100th amino acid to the ~ 200th amino acid, five significant peaks of RMSF were observed, whereas wild (blue line) AKR1C4 (complexed with ligand, NADPH) had lower mobility in that region. From the 200th amino acid to the 250th amino acid region, a significant peak was observed in the mutant AKR1C4, which was not detected in the wild AKR1C4 (Fig. 11).

The radius of gyration (Rg) of the wild AKR1C4 and the mutant (L311V) AKR1C4

The Rg value of mutant (redline) AKR1C4 (complexed with ligand, NADPH) significantly increased from 30 ns to 60 ns during the simulation (Fig. 12).

Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of the wild (red Line) AKR1C4 and the mutant (L311V) (blue line) AKR1C4

SASA values of the wild (blue-line) AKR1C4 (complexed with the ligand, NADPH) and the mutant (red-line) AKR1C4 (complexed with the ligand, NADPH) non-significantly differed throughout the simulation (Fig. 13).

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide, with rising incidences in emerging economies despite lower rates in developed ones. Although its etiology is not fully understood, it arises from both genetic predispositions and environmental factors. Key risk factors include early menarche, late menopause, age at first childbirth, infertility, and family history73. Additionally, exposure to ionizing radiation and carcinogenic chemicals increases breast cancer risk5,74. Normal mammary cells, which respond to steroid hormones, typically balance cell growth and death during menstrual cycles, pregnancy, and lactation. However, cancerous changes disrupt this balance, leading to sustained increases in cell populations and tumor development, influenced by fluctuations in estradiol and progesterone levels75.

AKR1C4, a crucial liver enzyme, metabolizes steroids by converting 5α-DHT into 3α-diol and 3β-diol, which are then glucuronidated and sulfated for excretion28,29,30,31,32. Notably, 3β-diol acts as an ERβ ligand, triggering anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects in specific tissues33,34. AKR1C4 also converts the progesterone derivative, 5α-pregnane-3,20-dione (5αP), to allopregnanolone, which is further metabolized to androsterone and 3α-diol by AKR1C3 for excretion35,36,37. A genetic variant in AKR1C4, rs17134592 (C931G), results in a leucine to valine substitution at position 311 (L311V), reducing enzyme activity. This reduction could impair the clearance of 5α-DHT, testosterone, and 5αP, potentially elevating the risk of tissue proliferation39. High testosterone levels may increase 17β-estradiol production through aromatase activity, stimulating breast tissue growth76. Moreover, excessive 5αP could promote cell proliferation in breast tissues by enhancing mitotic activity and reducing apoptosis and cell detachment77.

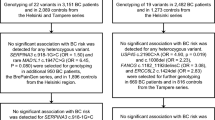

Given the enzyme’s role in steroid metabolism affecting cell proliferation and cancer progression, this study investigated the relationship between the rs17134592 polymorphism in the AKR1C4 gene and breast cancer susceptibility in the Bangladeshi population. While specific other polymorphisms have been associated with cancer susceptibility in East Asian and European populations, data from South Asian populations remain scarce. Our study addresses this gap by evaluating the rs17134592 polymorphism in a Bangladeshi cohort, providing novel insights into the genetic epidemiology specific to this population. We utilized in silico techniques and molecular dynamics simulations to assess the impact of this genetic variation on the AKR1C4 protein. In American females, those with the low-activity Val alleles showed a significant increase in mammographic breast density after combined estrogen-progestin therapy compared to carriers of the Leu allele, suggesting a higher breast cancer risk16. Apart from that study, the rs17134592 variant has not been extensively examined for its direct correlation with the onset of breast cancer. Consequently, this investigation may represent the inaugural study to assess the direct association between rs17134592 in the AKR1C4 gene and breast cancer across the entire population.

In this research, the genotypic variations of the AKR1C4 gene, specifically at the rs17134592 locus, were examined across a cohort of 300 individuals, divided evenly between 310 healthy subjects and 310 breast cancer (BC) patients. Despite similarities in age, menstrual status, and number of pregnancies, these groups differed significantly in age at menarche and BMI (Table 1). The analysis revealed a statistically significant association between the rs17134592 genetic variant and increased breast cancer risk among the Bangladeshi cohort. Significant differences in the genotypes and allele frequencies of the AKR1C4 rs17134592 (C931G) were observed between the two groups, with a higher prevalence of the G allele in the breast cancer group (Table 3). The study identified a markedly increased risk of breast cancer associated with the GG genotype compared to the CC genotype in both the additive model 2 and recessive model, with odds ratios (OR) of 3.39 and 3.25, respectively. Additionally, carriers of the G allele exhibited a 1.56-fold increased risk of developing breast cancer (Table 3).

In our study, we observed a significant association between the rs17134592 polymorphism and increased breast cancer risk in post-menopausal women, with the GG genotype in both the additive model 2 and recessive model, showing respective risks of 4.02 and 3.92 times higher than the CC genotype (Table 4). After menopause, ovarian estrogen production sharply decreases, resulting in increased peripheral androgen-to-estrogen conversion through aromatase activity16. AKR1C4 typically contributes to controlling androgen availability, converting active androgens to less active metabolites25,28,29. However, the L311V polymorphism could compromise this metabolic capacity50, potentially leading to increased androgenic substrates available for peripheral aromatization into estrogens. This could elevate local estrogen concentrations within breast tissue, thereby exacerbating estrogen-related carcinogenic pathways, specifically in post-menopausal women.

However, no significant correlations were found between tumor grade or size and breast cancer risk (Tables 5 and 6). One possible biological explanation is that this genetic variant might influence the initial carcinogenic processes rather than tumor progression or differentiation. Additionally, our study’s moderate sample size may have limited statistical power to identify subtle genotype-phenotype correlations with clinical parameters such as tumor size and grade. Furthermore, tumor progression is inherently complex, influenced by numerous genetic and environmental factors beyond a single genetic variant, potentially obscuring any direct association between rs17134592 and these tumor characteristics.

Furthermore, the observed Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) deviation in the case group suggests a potential association between rs17134592 and breast cancer susceptibility, rather than a random occurrence. This deviation may arise due to selection pressure, population stratification, or an overrepresentation of risk-associated genotypes in affected individuals. In contrast, the control group remained in HWE, reinforcing the reliability of the dataset and minimizing concerns regarding genotyping errors or sampling bias. The significant deviation in the combined dataset further indicates that rs17134592 may influence disease predisposition, potentially altering gene expression or enzyme function in a way that contributes to breast cancer risk. However, factors such as genetic drift or population substructure cannot be entirely ruled out. These findings highlight the necessity for further replication in more extensive, independent cohorts and functional studies to elucidate the precise role of this polymorphism in breast cancer development.

Consistent with the findings of Alam et al. (2024)4, our study demonstrated that breast cancer patients exhibited increased levels of both WBC counts and ESR, indicating enhanced immune activity and systemic inflammation. The elevated WBC levels likely result from the body’s response to tumor-induced stress and malignancy, reflecting an attempt to combat the progression of cancer cells78. Meanwhile, the rise in ESR points to the accumulation of inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines and acute-phase proteins, which are prevalent within the tumor microenvironment (TME)79. These immune and inflammatory interactions within the TME foster cancer cell survival, promote angiogenesis, and facilitate metastasis, further driving disease progression80.

The AKR1C4 gene, known for its involvement in steroid hormone metabolism, may also be impacted by trace element status, particularly since steroid hormone metabolism and detoxification processes rely heavily on metalloenzymes and redox balance, which are modulated by zinc and copper levels. Disruption of this delicate balance could influence the enzymatic activity of AKR1C4, potentially altering hormone profiles and influencing breast cancer risk5. In addition to zinc and copper, elevated lead (Pb) levels have been identified as a potential risk factor for ovarian cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers, highlighting the broader importance of environmental metal exposure in cancer development. While the relationship between lead exposure and AKR1C4 polymorphisms in breast cancer remains unexplored, these findings highlight the need to investigate environmental-genetic interactions in breast cancer risk6.

The evaluation of the L311V mutation in the AKR1C4 protein, using computational tools like MUpro and INPS-MD, suggested it is biochemically tolerated but leads to decreased protein stability. The HOPE server analysis further revealed that changes in amino acid properties disrupted interactions and hydrogen bonds. Notably, the mutation reduced the protein’s binding affinity for the ligand NADPH, indicating a potential impact on its biological function. From the 2D interaction diagram, it is found that L311V mutation weakens NADPH binding by reducing hydrogen bonds and Pi-alkyl/Pi-Pi interactions. While the wild-type complex forms strong Lys270 hydrogen bonds, the mutant introduces new interactions (Thr221, Leu219, His117, Tyr23, Tyr24) but loses key Lys270 bonds. Additionally, unfavorable interactions with Ser217, Arg276, and Asp50 may cause steric hindrance, further destabilizing ligand binding. These changes suggest a potential impact on AKR1C4 structure and function, affecting its catalytic efficacy.

Furthermore, molecular dynamics simulations of the AKR1C4 enzyme, in both its wild-type and L311V mutant forms with NADPH, revealed distinct dynamic and structural changes due to the mutation. The wild-type complex showed lower RMSD values, indicating more stable conformational behavior than the L311V mutant, which had higher RMSD, suggesting significant structural disruptions. Differences in RMSF values between the forms indicate altered flexibility, potentially affecting enzyme function. Despite similar solvent accessibility (SASA) across both forms, the radius of gyration data suggested a less compact and destabilized structure in the mutant. These in silico and molecular dynamics simulation findings are consistent with the results reported by T. Kume et al.50, who concluded that the L311V variation impacted the enzymatic activity of AKR1C4, leading to a significant decrease in catalytic efficiency.

Our study faced several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings and guiding future research. Firstly, the sample size was relatively small. Additionally, key hormonal measurements—such as 5α-DHT, 3α-diol, 3β-diol, 5αP, and allopregnanolone—were not conducted due to the lack of fresh blood sample. Also, mammographic percent density (MPD) data was unavailable from the medical center records. Considering the complexity of genetic influences, analyzing a single variant appears inadequate for definitive conclusions. Despite the novel insights provided by this study, our study primarily utilized computational in-silico approaches, such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations, to predict the structural and functional effects of the AKR1C4 polymorphism (rs17134592). While valuable, these computational methods cannot fully replicate the complexity of in vivo enzyme kinetics, including dynamic interactions within biological systems, enzyme-substrate affinities, or environmental influences.

Future research should aim to include larger sample sizes, diverse populations, more genetic variants, and the measurement of specific hormones in plasma. Population coverage analyses were not performed as this study specifically targeted a homogenous Bangladeshi population. However, future studies aiming to generalize findings beyond this specific demographic should consider incorporating population coverage analyses to understand broader applicability. It should also ensure the collection of MPD data. Additionally, future studies should combine AKR1C4 genotyping with trace element profiling from diet, environment, and blood biomarkers to assess whether trace element imbalances modify the effect of AKR1C4 polymorphisms on breast cancer risk, particularly in populations with distinct dietary and environmental exposures. Moreover, future functional studies involving cellular or animal models would be crucial to validate our computational predictions and provide deeper biological insights into the role of AKR1C4 variants in breast cancer pathogenesis. These enhancements will help clarify the gene’s role in breast cancer and its underlying biological mechanisms.

In conclusion, we found an association between AKR1C4 gene polymorphism (rs17134592) and breast malignancy in Bangladeshi individuals. The frequency of the G allele was notably greater in breast cancer individuals compared to control subjects. Thus, the GG genotype would be considered a risk factor, and CC genotypes would be a molecular marker of reducing breast cancer. In silico analyses and molecular dynamics simulations suggested that the L311V mutation results in considerable conformational instability to the AKR1C4 enzyme, which may affect its biological function and efficiency in catalytic processes. Overall, the genotyping of the AKR1C4 (rs17134592) gene would be a biomarker of early breast cancer diagnosis.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this manuscript [and its supplementary material files]. The sequencing data was deposited in GenBank BankIt of NCBI with submission ID 2941334. (Web link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/WebSub/)

References

Sarkar, S. et al. Cancer development, progression, and therapy: an epigenetic overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 (10), 21087–21113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141021087 (Oct 21 2013).

Omran, M. H. et al. Strong correlation of MTHFR gene polymorphisms with breast cancer and its prognostic clinical factors among Egyptian females. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 22 (2), 617–626. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.2.617 (Feb 1 2021).

Lei, S. et al. Global patterns of breast cancer incidence and mortality: A population-based cancer registry data analysis from 2000 to 2020. Cancer Commun. (Lond). 41 (11), 1183–1194. https://doi.org/10.1002/cac2.12207 (Nov 2021).

Alam, N. F. et al. Genetic association and computational analysis of MTHFR gene polymorphisms rs1801131 and rs1801133 with breast cancer in the Bangladeshi population. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 24232. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75656-y (Oct 16 2024).

Matuszczak, M. et al. Antioxidant Properties of Zinc and Copper-Blood Zinc-to Copper-Ratio as a Marker of Cancer Risk BRCA1 Mutation Carriers, Antioxidants (Basel), vol. 13, no. 7, Jul 14 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13070841

Kiljanczyk, A. et al. Blood Lead Level as Marker of Increased Risk of Ovarian Cancer in BRCA1 Carriers, Nutrients, vol. 16, no. 9, Apr 30 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16091370

Nabil, I. K. et al. Vitamin D deficiency and the vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene polymorphism rs2228570 (FokI) are associated with an increased susceptibility to hypertension among the Bangladeshi population. PLoS One. 19 (3), e0297138. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297138 (2024).

Saba, A. A. et al. Single nucleotide variants rs7975232 and rs2228570 within vitamin D receptor gene confers protection against severity of COVID-19 infection in Bangladeshi population. Gene Rep. 36 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genrep.2024.101981 (2024).

Tamanna, S. et al. Exploring the associations of maternal and neonatal eNOS gene variant rs2070744 with nitric oxide levels, oxidative stress and adverse outcomes in preeclampsia: A study in the Bangladeshi population. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12291-024-01264-2 (2024).

Nila, N. N. et al. The IKAROS transcription factor gene IKZF1 as a critical regulator in the pathogenesis of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: insights from a Bangladeshi population. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12291-024-01218-8 (2024).

Apostolou, P. & Fostira, F. Hereditary breast cancer: the era of new susceptibility genes, Biomed Res Int, vol. p. 747318, 2013, (2013). https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/747318

Lee, A., Moon, B. I. & Kim, T. H. BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variant breast cancer: treatment and prevention strategies. Ann. Lab. Med. 40 (2), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2020.40.2.114 (Mar 2020).

Harbeck, N. et al. Breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0111-2 (p. 66, Sep 23 2019).

Taylor, A. et al. Consensus for genes to be included on cancer panel tests offered by UK genetics services: guidelines of the UK cancer genetics group. J. Med. Genet. 55 (6), 372–377. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-105188 (Jun 2018).

Nik-Zainal, S. et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature, 534, 7605, pp. 47–54, Jun 2 2016, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17676

Lord, S. J. et al. Polymorphisms in genes involved in Estrogen and progesterone metabolism and mammographic density changes in women randomized to postmenopausal hormone therapy: results from a pilot study. Breast Cancer Res. 7 (3), R336–R344. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr999 (2005).

Oza, A. M. & Boyd, N. F. Mammographic parenchymal patterns: a marker of breast cancer risk. Epidemiol. Rev. 15 (1), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036105 (1993).

Penning, T. M. & Drury, J. E. Human aldo-keto reductases: Function, gene regulation, and single nucleotide polymorphisms, Arch Biochem Biophys, vol. 464, no. 2, pp. 241 – 50, Aug 15 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2007.04.024

Penning, T. M. & Byrns, M. C. Steroid hormone transforming aldo-keto reductases and cancer. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1155, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03700.x (Feb 2009).

Penning, T. M. et al. Human 3alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoforms (AKR1C1-AKR1C4) of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily: functional plasticity and tissue distribution reveals roles in the inactivation and formation of male and female sex hormones. Biochem. J. 351 (Oct 1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1042/0264-6021:3510067 (2000). no. Pt 1.

Hyndman, D., Bauman, D. R., Heredia, V. V. & Penning, T. M. The aldo-keto reductase superfamily homepage. Chem. Biol. Interact. 143–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00193-x (2003). 621 – 31, Feb 1.

Khanna, M., Qin, K. N., Wang, R. W. & Cheng, K. C. Substrate specificity, gene structure, and tissue-specific distribution of multiple human 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases. J. Biol. Chem. 270 (34), 20162–20168. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.270.34.20162 (Aug 25 1995).

Jez, J. M., Bennett, M. J., Schlegel, B. P., Lewis, M. & Penning, T. M. Comparative anatomy of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily, Biochem J, vol. 326 (Pt 3), no. Pt 3, pp. 625 – 36, Sep 15 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1042/bj3260625

Schlegel, B. P., Jez, J. M. & Penning, T. M. Mutagenesis of 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase reveals a push-pull mechanism for proton transfer in aldo-keto reductases, Biochemistry, vol. 37, no. 10, pp. 3538-48, Mar 10 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1021/bi9723055

Talalay, P. Enzymatic mechanisms in steroid metabolism, Physiol Rev, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 362 – 89, Jul (1957). https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1957.37.3.362

Penning, T. M., Smithgall, T. E., Askonas, L. J. & Sharp, R. B. Rat liver 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, Steroids, vol. 47, no. 4–5, pp. 221 – 47, Apr-May 1986. https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-128x(86)90094-2

Hung, C. F. & Penning, T. M. Members of the nuclear factor 1 transcription factor family regulate rat 3alpha-hydroxysteroid/dihydrodiol dehydrogenase (3alpha-HSD/DD AKR1C9) gene expression: a member of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily. Mol. Endocrinol. 13 (10), 1704–1717. https://doi.org/10.1210/mend.13.10.0363 (Oct 1999).

Jin, Y. & Penning, T. M. Steroid 5alpha-reductases and 3alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases: key enzymes in androgen metabolism. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 15 (1), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1053/beem.2001.0120 (Mar 2001).

Van Doorn, E. J., Burns, B., Wood, D., Bird, C. E. & Clark, A. F. In vivo metabolism of 3H-dihydrotestosterone and 3H-androstanediol in adult male rats. J. Steroid Biochem. 6, 11–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4731(75)90213-7 (pp. 1549–54, Nov-Dec 1975).

Saartok, T., Dahlberg, E. & Gustafsson, J. A. Relative binding affinity of anabolic-androgenic steroids: comparison of the binding to the androgen receptors in skeletal muscle and in prostate, as well as to sex hormone-binding globulin, Endocrinology, vol. 114, no. 6, pp. 2100-6, Jun (1984). https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-114-6-2100

Mauvais-Jarvis, P. & Baulieu, E. E. Studies on testosterone metabolism. IV. Urinary 5-alpha- and beta-androstanediols and testosterone glucuronide from testosterone and dehydrolsoandrosterone sulfate in normal people and hirsute women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 25 (9), 1167–1178. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-25-9-1167 (Sep 1965).

Habrioux, G., Desfosses, B., Condom, R., Faure, B. & Jayle, M. Simultaneous radioimmunoassay of 5alpha-androstane-3alpha, 17beta-diol and 5alpha-androstane-3beta, 17beta-diol unconjugated and conjugated in human serum, Steroids, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 61–71, Jul-Aug (1978). https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-128x(78)90100-9

Weihua, Z. et al. A role for Estrogen receptor beta in the regulation of growth of the ventral prostate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 98 (11), 6330–6335. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.111150898 (May 22 2001).

Weihua, Z., Lathe, R., Warner, M. & Gustafsson, J. A. An endocrine pathway in the prostate, erbeta, AR, 5alpha-androstane-3beta,17beta-diol, and CYP7B1, regulates prostate growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 99 (21), 13589–13594. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.162477299 (Oct 15 2002).

Wiebe, J. et al. The 4-Pregnene and 5α-Pregnane progesterone metabolites formed in nontumorous and tumorous breast tissue have opposite effects on breast cell proliferation and adhesion. Cancer Research, 60, pp. 936 – 43, 02/01 2000.

Higaki, Y. et al. Selective and potent inhibitors of human 20alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (AKR1C1) that metabolizes neurosteroids derived from progesterone, Chem Biol Interact, vol. 143–144, pp. 503 – 13, Feb 1 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00206-5

Auchus, R. J. The backdoor pathway to dihydrotestosterone. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 15 (9), 432–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2004.09.004 (Nov 2004).

Deyashiki, Y. et al. Molecular cloning of two human liver 3 alpha-hydroxysteroid/dihydrodiol dehydrogenase isoenzymes that are identical with chlordecone reductase and bile-acid binder, Biochem J, vol. 299 (Pt 2), no. Pt 2, pp. 545 – 52, Apr 15 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1042/bj2990545

Rizner, T. L. & Penning, T. M. Role of aldo-keto reductase family 1 (AKR1) enzymes in human steroid metabolism, Steroids, vol. 79, pp. 49–63, Jan (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2013.10.012

Nilsson, S., Koehler, K. F. & Gustafsson, J. A. Development of subtype-selective oestrogen receptor-based therapeutics, Nat Rev Drug Discov, vol. 10, no. 10, pp. 778 – 92, Sep 16 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3551

Pawlak, K. J. & Wiebe, J. P. Regulation of Estrogen receptor (ER) levels in MCF-7 cells by progesterone metabolites. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 107, 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.05.030 (pp. 172–9, Nov-Dec 2007).

Shin, S. Y. et al. An atlas of genetic influences on human blood metabolites. Nat. Genet. 46 (6), 543–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2982 (Jun 2014).

Willer, C. J. et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat. Genet. 45 (11), 1274–1283. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2797 (Nov 2013).

Spracklen, C. N. et al. Association analyses of East Asian individuals and trans-ancestry analyses with European individuals reveal new loci associated with cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26 (9), 1770–1784. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddx062 (May 1 2017).

Hoffmann, T. J. et al. A large electronic-health-record-based genome-wide study of serum lipids. Nat. Genet. 50 (3), 401–413. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0064-5 (Mar 2018).

Ripatti, P. et al. Polygenic Hyperlipidemias and Coronary Artery Disease Risk, Circ Genom Precis Med, vol. 13, no. 2, p. e002725, Apr (2020). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGEN.119.002725

Oskarsson, G. R. et al. Predicted loss and gain of function mutations in ACO1 are associated with erythropoiesis, Commun Biol, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 189, Apr 23 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-0921-5

Auchus, R. J. Non-traditional metabolic pathways of adrenal steroids. Reviews Endocr. Metabolic Disorders. 10 (1), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-008-9095-z (2008).

Ruth, K. S. et al. Using human genetics to understand the disease impacts of testosterone in men and women. Nat. Med. 26 (2), 252–258. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0751-5 (Feb 2020).

Kume, T. et al. Characterization of a novel variant (S145C/L311V) of 3alpha-hydroxysteroid/dihydrodiol dehydrogenase in human liver, (in eng), Pharmacogenetics, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 763 – 71, Dec (1999).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences, Behav Res Methods, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 175 – 91, May (2007). https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A. G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods. 41 (4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 (Nov 2009).

Shi, Y. Y. & He, L. SHEsis, a powerful software platform for analyses of linkage disequilibrium, haplotype construction, and genetic association at polymorphism loci, Cell Res, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 97 – 8, Feb (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cr.7290272

Shen, J. et al. SHEsisPlus, a toolset for genetic studies on polyploid species. Sci. Rep. 6, 24095. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24095 (Apr 6 2016).

Nila, N. N. et al. Investigating the structural and functional consequences of germline single nucleotide polymorphisms located in the genes of the alternative lengthening of telomere (ALT) pathway, Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 12, p. e33110, Jun 30 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33110

Tanshee, R. R., Mahmud, Z., Nabi, A. & Sayem, M. A comprehensive in Silico investigation into the pathogenic SNPs in the RTEL1 gene and their biological consequences. PLoS One. 19 (9), e0309713. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0309713 (2024).

Ahmed, H. U., Paul, A., Mahmud, Z., Rahman, T. & Hosen, M. I. Comprehensive characterization of the single nucleotide polymorphisms located in the isocitrate dehydrogenase isoform 1 and 2 genes using in Silico approach. Gene Rep. 24 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genrep.2021.101259 (2021).

Sim, N. L. et al. SIFT web server: predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins, Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 40, no. Web Server issue, pp. W452-7, Jul (2012). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks539

Adzhubei, I., Jordan, D. M. & Sunyaev, S. R. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2, Curr Protoc Hum Genet, vol. Chapter 7, p. Unit7 20, Jan (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76

Bendl, J. et al. PredictSNP: robust and accurate consensus classifier for prediction of disease-related mutations, PLoS Comput Biol, vol. 10, no. 1, p. e1003440, Jan (2014). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003440

Johnson, A. D. et al. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap, Bioinformatics, vol. 24, no. 24, pp. 2938-9, Dec 15 2008. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564

Capriotti, E. & Fariselli, P. PhD-SNPg: a webserver and lightweight tool for scoring single nucleotide variants, Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 45, no. W1, pp. W247-W252, Jul 3 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx369

Stone, E. A. & Sidow, A. Physicochemical constraint violation by missense substitutions mediates impairment of protein function and disease severity, Genome Res, vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 978 – 86, Jul (2005). https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.3804205

Cheng, J., Randall, A. & Baldi, P. Prediction of protein stability changes for single-site mutations using support vector machines, Proteins, vol. 62, no. 4, pp. 1125-32, Mar 1 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.20810

Savojardo, C., Fariselli, P., Martelli, P. L. & Casadio, R. INPS-MD: a web server to predict stability of protein variants from sequence and structure, Bioinformatics, vol. 32, no. 16, pp. 2542-4, Aug 15 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw192

Venselaar, H., Te Beek, T. A., Kuipers, R. K., Hekkelman, M. L. & Vriend, G. Protein structure analysis of mutations causing inheritable diseases. An e-Science approach with life scientist friendly interfaces. BMC Bioinform. 11, 548. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-11-548 (Nov 8 2010).

Waterhouse, A. et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes, Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 46, no. W1, pp. W296-W303, Jul 2 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky427

Berman, H. M. The protein data bank: a historical perspective. Acta Crystallogr. A. 64, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108767307035623 (Jan 2008). no. Pt 1.

Wiederstein, M. & Sippl, M. J. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins, Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 35, no. Web Server issue, pp. W407-10, Jul (2007). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm290

Al-Khayyat, M. Z. & Al-Dabbagh, A. G. In Silico prediction and Docking of tertiary structure of luxi, an inducer synthase of vibrio fischeri, (in eng). Rep Biochem. Mol. Biol, 4, 2, pp. 66–75, Apr 2016.

Eberhardt, J., Santos-Martins, D., Tillack, A. F. & Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new Docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J Chem. Inf. Model, 61, 8, pp. 3891–3898, Aug 23 2021, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1-2, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001 (2015).

Dumitrescu, R. G. & Cotarla, I. Understanding breast cancer risk -- where do we stand in 2005? J Cell. Mol. Med, 9, 1, pp. 208 – 21, Jan-Mar 2005, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00350.x

DeBruin, L. S. & Josephy, P. D. Perspectives on the chemical etiology of breast cancer, Environ Health Perspect, vol. 110 Suppl 1, no. Suppl 1, pp. 119 – 28, Feb (2002). https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.02110s1119

Wiebe, J. P. Progesterone metabolites in breast cancer, Endocr Relat Cancer, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 717 – 38, Sep (2006). https://doi.org/10.1677/erc.1.01010

Wang, L. et al. Estrogen-induced circRNA, circPGR, functions as a ceRNA to promote estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cell growth by regulating cell cycle-related genes, Theranostics, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 1732–1752, (2021). https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.45302

Wiebe, J. P., Beausoleil, M., Zhang, G. & Cialacu, V. Opposing actions of the progesterone metabolites, 5alpha-dihydroprogesterone (5alphaP) and 3alpha-dihydroprogesterone (3alphaHP) on mitosis, apoptosis, and expression of Bcl-2, Bax and p21 in human breast cell lines, J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, vol. 118, no. 1–2, pp. 125 – 32, Jan (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.11.005

Akinsipe, T. et al. Cellular interactions in tumor microenvironment during breast cancer progression: new frontiers and implications for novel therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 15, 1302587. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1302587 (2024).

Kartikasari, A. E. R., Huertas, C. S., Mitchell, A. & Plebanski, M. Tumor-Induced inflammatory cytokines and the emerging diagnostic devices for cancer detection and prognosis. Front. Oncol. 11, 692142. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.692142 (2021).

Salemme, V., Centonze, G., Cavallo, F., Defilippi, P. & Conti, L. The crosstalk between tumor cells and the immune microenvironment in breast cancer: implications for immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 11, 610303. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.610303 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: ZHH, ZM; Study design: ZHH, ZM; Sample collection and processing: MAS, FA, ZM; Data curation and analysis: MAS, FA, ZM, ST, AAS, RS, ZHH; Result interpretation: MAS, FA, ZM, ST, AAS, RS, TH, ZHH; Supervision: ZHH, ZM; Writing original draft: MAS, ZM, FA, ZHH; Review and editing: ZM, TH, ZHH.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethical Review Committee of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, approved the study at the University of Dhaka (Ref. No. BMBDU-ERC/EC/23/014). In addition, we confirm that all methods used in this study were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed written consent was taken from all the study subjects before collecting samples.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shaon, M.A., Ansari, F., Mahmud, Z. et al. Genetic and computational analysis of AKR1C4 gene rs17134592 polymorphism in breast cancer among the Bangladeshi population. Sci Rep 15, 27526 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13411-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13411-7