Abstract

The development and refinement of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms have been an area of intense research in radiology and pathology, particularly for automated or computer-aided diagnosis. Whole Slide Imaging (WSI) has emerged as a promising tool for developing and utilizing such algorithms in diagnostic and experimental pathology. However, patch-wise analysis of WSIs often falls short of capturing the intricate cell-level interactions within local microenvironment. A robust alternative to address this limitation involves leveraging cell graph representations, thereby enabling a more detailed analysis of local cell interactions. These cell graphs encapsulate the local spatial arrangement of cells in histopathology images, a factor proven to have significant prognostic value. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) can effectively utilize these spatial feature representations and other features, demonstrating promising performance across classification tasks of varying complexities. It is also feasible to distill the knowledge acquired by deep neural networks to smaller student models through knowledge distillation (KD), achieving goals such as model compression and performance enhancement. Traditional approaches for constructing cell graphs generally rely on edge thresholds defined by sparsity/density or the assumption that nearby cells interact. However, such methods may fail to capture biologically meaningful interactions. Additionally, existing works in knowledge distillation primarily focus on distilling knowledge between neural networks. We designed cell graphs with biologically informed edge thresholds or criteria to address these limitations, moving beyond density/sparsity-based definitions. Furthermore, we demonstrated that student models do not need to be neural networks. Even non-neural models can learn from a neural network teacher. We evaluated our approach across varying dataset complexities, including the presence or absence of distribution shifts, varying degrees of imbalance, and different levels of graph complexity for training GNNs. We also investigated whether softened probabilities obtained from calibrated logits offered better guidance than raw logits. Our experiments revealed that the teacher’s guidance was effective when distribution shifts existed in the data. The teacher model demonstrated decent performance due to its higher complexity and ability to use cell graph structures and features. Its logits provided rich information and regularization to students, mitigating the risk of overfitting the training distribution. We also examined the differences in feature importance between student models trained with the teacher’s logits and their counterparts trained on hard labels. In particular, the student model demonstrated a stronger emphasis on morphological features in the Tuberculosis (TB) dataset than the models trained with hard labels. This emphasis aligns closely with the features that pathologists typically prioritize for diagnostic purposes. Future work could explore designing alternative teacher models, evaluating the proposed approach on larger datasets, and investigating causal knowledge distillation as a potential extension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cell graphs have emerged as a powerful tool for capturing the spatial and functional relationships within tissues. They encapsulate cellular and tissue-level architecture by representing cells as nodes and their interactions as edges. They are particularly valuable for bridging the gap between molecular details and their collective impact on larger biological processes, such as wound healing, tumor progression, and immune response1. The cell-graph technique seeks to uncover the structure-function relationship by modeling the structural organization of tissue using graph theory. For instance, in the context of breast cancer, cancer cells often cluster together to form dense regions of abnormal tissue. This clustering reflects the biological processes underlying tumor growth2, such as rapid cell division, altered adhesion properties, and disrupted tissue architecture. By analyzing the spatial distribution and interactions of these clustered cells, the cell-graph approach can provide insights into the functional state of the tissue, such as tumor aggressiveness. This study focuses on three primary cell graph-based datasets: Tuberculosis (TB), Placenta, and Breast Cancer Classification. TB is a highly contagious disease and a leading cause of ill health and mortality worldwide. According to the World Health Organization’s report on TB3, an estimated 1.25 million people succumbed to the disease in 2023. Pulmonary TB, primarily caused by an infectious bacterium, predominantly impacts the lungs through airborne transmission4. Granulomas in lung tissue are characteristic of both human and experimental pulmonary tuberculosis5,6. Identifying acid-fast bacilli (AFB) in stained samples is essential for diagnosing tuberculosis7.

Whole-slide imaging makes it easier to digitally examine these stained samples, allowing for high-resolution, in-depth tissue investigation. They preserve fine-grained cellular morphology and local tissue architecture that is often lost through downsampling. Traditional WSI analysis pipelines resort to patch-based processing or downsampling, fragmenting tissue structure and sacrificing essential contextual information8. In our approach, we construct cell graphs from whole slide images that integrate local morphological features with spatial context. A deep GNN is then applied to these graphs to learn complex cell interactions, translating the rich WSI content into structured, relational representations. The edge threshold for intercellular communication is crucial in constructing biologically meaningful cell graphs. Incorporating pathologist insights can help refine this threshold, ensuring the graph representation aligns with the underlying cellular interactions. We determined edge thresholds based on the biological rationale for the cell graphs we constructed and validated them through consultations with our domain expert. For the TB dataset cell graphs, nodes represent either acid-fast bacilli (AFB) or the nucleus of activated macrophages, and edge thresholds are based on the length of cords of the M.tb infected cells after 72 hours of infection9 and the fact that macrophages extend pseudopods to sense their environment10. The Placenta dataset represents diverse histological structures essential to placental biology, including various types of trophoblastic villi (TVilli, MIVilli, SVilli, AVilli), Sprouts, Chorion, Maternal cells, Fibrin, and Avascular regions. These structures capture key functional and structural aspects of the placenta. Cell graphs from this dataset reveal how these structures collectively contribute to placental function. Finally, cell graphs from the breast cancer dataset show the spatial arrangement and interactions between tumor cells, lymphocytes, and stromal cells. Edges in these cell graphs were constructed based on factors such as immune surveillance by lymphocytes and the clustering behavior of tumor cells facilitated by adhesion molecules11. They captured important patterns, such as tumor-immune interactions and interactions with stromal cells, essential for understanding disease progression and prognosis.

The cell-graph technique leverages image processing, feature extraction, and machine learning algorithms to establish a quantitative relationship between structure and function1. Our approach extends this by employing a GNN trained on these cell graphs to learn and model this relationship effectively. Within our proposed graph model, which we term as Cell Graph Jumping Knowledge Neural Network (CG-JKNN), we incorporate the concept of ’jumping knowledge’12 from GraphSAGE layers. This approach aggregates information from multiple network layers rather than relying solely on the final layer. We enhance the jumping knowledge with GATv2’s attention mechanism to refine this process further. This allows the model to focus on the most informative nodes dynamically.

An important question is whether the knowledge learned by complex deep learning models, such as GNNs in our work, can be effectively distilled into simpler, non-neural network-based models. The answer lies in knowledge distillation (KD), a process where the knowledge from a teacher model (in this case, a GNN) is distilled into student models, typically less complex. Knowledge distillation on graphs brings the advantages of KD into graph learning. This approach primarily serves two objectives: model compression and performance improvement. Model compression focuses on creating a smaller student model than the teacher model. After distillation, the student model achieves a performance comparable to that of the teacher while requiring fewer parameters. Performance improvement focuses on transferring knowledge from the teacher to the student model, aiming to enhance the student’s performance beyond that of a model trained without knowledge distillation13. The student model may be smaller, similar, or architecturally different from the teacher. The other main goals of KD are knowledge adaptation and knowledge expansion14. Knowledge adaptation focuses on helping student networks perform well on new, unseen target domains by using knowledge from teacher networks trained on similar source domains. Knowledge expansion aims to create student networks that are more capable and perform better than the teacher networks. In our work, we focus on model compression and performance improvement. Existing approaches to knowledge distillation mainly focus on neural network-based student models15,16,17 using their iterative learning capabilities to align with the teacher’s outputs. However, this work demonstrates that knowledge can be distilled to non-neural network-based models, such as tree-based ensemble models. The knowledge that can be distilled can be categorized into various forms, including response-based, intermediate, relation-based, and mutual information-based representations14. In this work, we focus on response-based knowledge distillation, using the logits generated by a deep GNN as targets to train tree-based ensemble regressor models. These student models are significantly less complex than the teacher. Our primary objective is to evaluate whether the teacher’s guidance through logits provides better insights into the student models than traditional hard labels. We will use the term “Guidance” throughout the paper, which refers to the teacher model’s ability to provide detailed class distinctions and enhance the student model’s performance and generalization through its logits. Literature suggests that students trained on logits are better equipped to mimic the behavior of the teacher model18. This approach enhances the student’s performance and enables it to be a partial proxy for interpreting the teacher’s decision-making process. In one of our ablation studies, we analyze the differences in feature importance between the student trained on logits and its counterpart trained on hard labels to identify any notable distinctions. To measure the efficacy of this distillation process, we employ a distillation quality metric that balances model complexity and performance. Furthermore, we extend our analysis to explore whether calibration (aligning the probabilities derived from logits with the true likelihood of events) improves the guidance provided by logits. Additionally, we evaluate the efficacy of our approach under varying dataset complexities, including the presence or absence of distribution shifts, imbalanced data, different feature sets, and different levels of training graph complexity. To broaden the applicability of our method, we also test it on datasets beyond cell graphs.

In this study, we addressed key questions to learn the efficacy of knowledge distillation in our proposed framework. Specifically, we sought to answer the following:

-

Do all student models benefit from knowledge distilled from the teacher GNN trained on cell graphs with local cell graph features and/or morphological features under varying dataset complexities such as the presence of distribution shifts?

-

Do the features selected by models trained on hard labels differ from those chosen by the students, and can these differences provide insights into the teacher’s guidance?

-

Can a student model achieve better performance when trained using the combined guidance of the teacher model and the best-performing student, compared to being taught solely by the teacher model?

-

Can calibration of teacher logits provide better guidance to student models?

The major contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

-

Inspired by Fukui et al.19, we proposed a knowledge distillation framework that uses the logits from a GNN model with jumping knowledge, which acts as the teacher, to train non-neural network models as student models. To our knowledge, this is the first work exploring a teacher trained on cell graphs to guide non-neural network-based student models.

-

We proposed a method to approximate the number of parameters/complexity of student models using the asymptotic equivalence between the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and leave-one-out cross-validation.

-

We evaluated the efficacy of knowledge distillation under diverse dataset conditions, including varying degrees of imbalance, distribution shifts, and varying graph complexities. We also tested our approach across various feature sets, including combinations of cell graph features and morphological features, individual feature sets (only cell graph features or morphological features), and non-cell graph features.

-

We explored the impact of post-calibrating logits to enhance the guidance provided by teacher models to student models. We proposed a modified distillation quality metric that effectively measures the quality of knowledge distilled, even in scenarios where the student model outperforms the teacher.

-

We conducted ablation studies to determine whether the best-performing student model, in combination with the teacher model, could improve guidance. Additionally, we analyzed how feature importance varied when guided by the teacher and explored the biological relevance of these features.

Section “Related works” discusses prior research in the domain. Section “Methods” describes this study’s proposed methodology and framework. Section “Results” presents the experimental results and evaluates the performance of our approach. Section “Discussion and major takeaways” analyzes the implications of our findings and summarizes the key takeaways of this study. Section “Limitations of our work” outlines the limitations of our approach. Section “Conclusion and future work” summarizes the contributions and identifies areas for future work.

Related works

Cell graphs and GNNs trained on cell graphs: applications in disease prediction and classification

Graph construction for modeling cellular interactions often assumes that neighboring cells are more likely to interact. To capture these interactions, methods such as Delaunay triangulation1,20,21 and K-nearest-neighbor (KNN)22,23,24,25 are widely employed. The Waxman model26 is another approach that uses an exponential decay function of Euclidean distance to define edges probabilistically. Numerous studies have utilized cell graphs to gain insights into the organization and behavior of cells within tissues. The pioneering work on cell graphs highlighted that the most effective cell-graph construction methods emerge from combining physics-driven and data-driven paradigms1. The study presented in27 used a computational method using cell-graph evolution to model glioma malignancy. It linked graph phases to cancer severity through connectivity analysis of cell graphs constructed from tissue photomicrographs. The authors in28 presented a computational method to model glioma malignancy using cell-graph topology from tissue images. Cell-graph edges were generated using the Waxman model. By analyzing graph metrics of cancerous cell clusters, the method achieved 85% accuracy at the cellular level and 100% accuracy at the tissue level. An augmented cell-graph (ACG) method for diagnosing malignant glioma from low-magnification tissue images was introduced in29. It represented cell clusters as nodes and their relationships as weighted edges. Tested on 646 brain biopsy samples, the approach achieved 97.53% sensitivity and specificities of 93.33% (inflamed) and 98.15% (healthy) at the tissue level. Gunduz-Demir30 introduced an object-graph-based approach for gland segmentation by leveraging the organizational properties of primitive objects. It achieved high segmentation accuracy when applied to colon tissue images and demonstrated robustness to artifacts and tissue variances. The authors in31 introduced a Cell Graph Transformer (CGT) for nuclei classification in histopathology images. A topology-aware pretraining method using a graph convolutional network (GCN) was proposed to learn a feature extractor to address challenges with noisy self-attention scores in complex cell graphs. The study in32 presented sigGCN, a multimodal deep learning model combining a graph convolutional network (GCN) and neural network to integrate gene interaction networks for cell classification. The method outperformed existing traditional approaches in both within-dataset and cross-dataset classifications. Graph neural network-based approach that leveraged cell graphs from multiplexed immunohistochemistry (mIHC) images to predict patient survival and digitally stage gastric cancer was proposed in33. Edges in the cell graph were established based on the Euclidean distance between cell pairs, connecting cells separated by less than 20 \(\mu\)m. It outperformed traditional staging systems, achieving high AUC scores (0.960 for binary and 0.771-0.904 for ternary classification). A novel cell-graph convolutional neural network for colorectal cancer (CRC) grading that models large histology images as graphs was proposed in23. It incorporated both nuclear appearance and spatial information. An edge was placed between two nuclei if they were at a fixed distance from each other. By introducing Adaptive GraphSage for multi-scale feature fusion and a sampling technique to address graph redundancy, CGC-Net effectively captured tissue micro-environment structures. A hierarchical Transformer Graph Neural Network, combining GNN and Transformer architectures, was introduced in24. The main aim was to achieve colorectal adenocarcinoma cancer (CRA) grading using the cell graph that was constructed using the KNN approach. It used a Masked Nuclei Patch (MNP) strategy to train a ResNet-50 to extract representative nuclei features. The transformer module captured long-distance dependencies, achieving state-of-the-art results on CRA grading tasks. The authors in34 proposed Feature-Driven Local Cell Graphs (FeDeG) for constructing cell graphs by integrating spatial proximity and nuclear attributes like shape, size, and texture. Graph-derived metrics extracted from FeDeGs were used with a linear discriminant classifier, achieving an AUC of 0.68. A Hierarchical Cell-to-Tissue (HACT) graph representation utilizing the cell graphs was proposed in35. The tissue structure and functionality were modeled using a novel hierarchical graph neural network (HACT-Net). Using the Breast Carcinoma Subtyping (BRACS) dataset, HACT-Net outperformed state-of-the-art methods and individual pathologists.

Knowledge distillation in graphs

With the demand for efficient models, KD is an ever-developing field. Among the various types of information that can be distilled, including logits, embeddings, and graph structures, we specifically use logits as the training labels for the student models. Many works have focused on transferring logits as a form of knowledge in knowledge distillation. The authors in36 systematically compared different knowledge sources–features, logits, and gradients in knowledge distillation by approximating the KL-divergence criterion. They analyzed their effectiveness in model compression and incremental learning and found that logits were generally more efficient. Recently, a refined knowledge distillation method that employed labeling information to refine teacher logit dynamically and to eliminate misleading information from the teacher was introduced in37. Distilling graph structure information involves transferring knowledge about the connectivity and relationships between nodes and edges38, which is crucial for modeling graph data. Additionally, some works distill learned node embeddings from the intermediate layers of teacher models to guide the student model’s learning.

In the context of knowledge distillation, various setups exist to transfer knowledge. There are teacher-free networks where the student model learns independently without a teacher. In teacher-to-student networks, the knowledge transfer can involve one or multiple teachers guiding the students. Additionally, distillation can be categorized as offline or online. Online distillation refers to a scheme where the teacher and student models are trained simultaneously in an end-to-end manner. In contrast, offline distillation involves a pre-trained teacher model that facilitates the student’s training without undergoing further updates. In our study, we utilize a teacher-to-student setup with two configurations: a single teacher guiding the student and a combination of the teacher and the best-performing student acting as teachers. Additionally, our approach falls under the category of offline distillation, as the teacher models are pre-trained and remain unchanged during the training of the student models.

Numerous works have been conducted to highlight the use of knowledge distillation in graphs. In39, the authors proposed a method for compressing a k-layered graph convolution network (GCN) by repeating a single GCN layer k times and distilling both the logits and final node embeddings. The authors in40 used two heterogeneous teacher models to distill their embeddings via a topological attribution map and logits. In41, the authors trained a teacher on offline graph snapshots with a self-attention mechanism to distill to a smaller, more efficient student model making predictions on online graph snapshots. A neighbor distillation method to distill local structure knowledge and to use peer node information to learn the local structure was proposed in42. The approach in43 used logit distillation and auxiliary representation distillation methods such as Locality Structure Preserving distillation (LSP)44. In45, the authors used adversarial training for KD by applying a discriminator to the embeddings and logits of the student and teacher models. The authors in46 proposed a method for fair distillation where a student model learned both the distilled logits and a proxy for bias from the teacher, which was removed during testing with the rationale that it contained most of the information on bias and its exclusion would result in fair predictions. An interesting logits-based KD method termed Decoupled Graph Knowledge Distillation (DGKD) was proposed in47. It reformulated the distillation loss into the components of target class (TCGD) and non-target class (NCGD). By decoupling the fixed weight between these losses and addressing their negative correlation, DGKD dynamically adjusted the weights for different data samples. This led to improved prediction accuracy for student MLP. The authors in48 proposed Knowledge Distillation for Graph Augmentation (KDGA) that mitigated the adverse effects of distribution shifts caused by graph augmentation. KDGA transferred knowledge from a GNN teacher trained on augmented graphs to a partially parameter-shared student tested on the original graph. This helped to improve performance across various GNN architectures and augmentation methods. In49, they transferred knowledge from two specialized teacher models, one focused on features and the other on structure, using a teacher-student distillation framework. The feature-level teacher guided the student on completing and leveraging node features, while the structure-level teacher focused on graph topology. However, these works primarily focused on distilling knowledge from a GNN to another GNN or other neural networks. In19, the authors proposed a distillation method that utilized information extracted from neural networks to train non-neural network models, such as support vector machines, random forests, and gradient-boosting decision trees. Their study was limited to a single image-based dataset and did not provide a detailed analysis of why specific student models failed to achieve the desired performance when trained with logits obtained from the teacher CNN. Moreover, they evaluated their approach using only two out of ten available classes for simplicity, which does not adequately demonstrate the efficacy of KD in a multiclass setting.

Problem statement

Currently used methods for building cell graphs typically use a single-edge threshold to represent every interaction between cells. These thresholds are often chosen based on factors such as achieving denser graphs. However, this approach overlooks the biological diversity of interactions, as different cell types exhibit distinct interaction patterns that a uniform edge threshold cannot adequately capture. A more biologically informed methodology for defining these thresholds is necessary to better reflect the underlying cellular relationships. In the context of knowledge distillation from GNNs, most existing works focus on transferring knowledge from GNNs to other neural networks. However, student models need not be limited to neural networks. They can include non-neural models. Furthermore, evaluating the efficacy of knowledge distillation in our specific setup requires a broader understanding of its behavior under varying dataset complexities, including scenarios with distribution shifts, multiple classes, and other challenges.

Methods

Datasets based on cell graphs and non-cell graphs

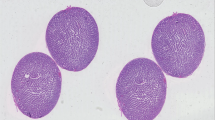

For this work, we utilized three cell graph-based datasets: one from our previous paper on tuberculosis (TB)50, another dataset from placenta histology51, and lastly, the TCGA Breast Cancer Cell Classification Dataset (BRCA-M2C)52. The TB dataset contained 44 whole slide images (WSIs) with an average size of 42,831 x 41,159 pixels at 40X magnification. The nodes were classified into acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and the nucleus of activated macrophages. The approach used to determine the cell locations and classify the cell types is detailed in our previous work50. We used 34 WSIs for training and validation, while 10 WSIs were reserved for the test set. The train and test WSIs used in this study differed from those proposed in50. The training set had 90878 nodes, the validation set had 22708 nodes, and the test set had 76316 nodes.

The placenta dataset consisted of two cell graphs constructed from two placenta histology WSIs, combined into a single graph with nine classes. We utilized the original 64-dimensional feature set provided with the dataset for our analysis. These features primarily focussed on the morphological characteristics of the cells. Our goal was to evaluate the efficacy of knowledge distillation with cell graph datasets where the cell graph features were not included in the training process. The process of feature extraction is described in51. Additionally, we followed the dataset’s original train, validation, and test split (considering only labeled nodes).

The BRCA-M2C dataset (Breast Cancer Dataset)52 provided dot annotations for multi-class cell classification in breast cancer images, including the annotated cells’ coordinates and corresponding labels. The cell extraction and labeling process can be found in52. These images were patches extracted from 1000x1000 pixels at the highest resolution and downsampled to 20x. All images were around 500x500 pixels. The cell classes included lymphocytes, breast cancer cells, and stromal cells. There were 80 image data (coordinates of the annotated cells along with their corresponding labels) under the training set, 10 image data under the validation set, and the test set consisted of 30 image data. We combined training and validation data while keeping the test data unchanged. This resulted in 19602 training nodes, 2178 validation set nodes, and 8858 test set nodes.

To determine the generalizability of our approach to non-cell graph-based datasets and in the absence of features extracted from cell graphs, we used three non-cell graph-based datasets: CoauthorCS, CoauthorPhysics and a synthetic dataset. These datasets consisted of a single graph. The CoauthorCS dataset consisted of 18,333 nodes and 163,788 edges, with nodes divided into 15 classes. A 6,805-dimensional feature vector represented each node. The training set had 12833 nodes, the validation set had 3666 nodes, and the test set had 1834 nodes. Similarly, the CoauthorPhysics dataset contained 34,493 nodes and 495,924 edges, with nodes categorized into five classes. Node features in this dataset were 8,415-dimensional vectors. The training set had 24145 nodes, the validation set had 6898 nodes, and the test set had 3450 nodes. These datasets were only used to evaluate the applicability of our approach to non-cell graph settings and were not included in ablation studies. We generated a synthetic dataset of 60,000 nodes using the preferential attachment mechanism of the Barabási-Albert model53. Seven topological features were extracted for this graph to represent its structural properties. The dataset training set contained 42,000 nodes, 12,000 nodes were present in the validation set, and 6,000 nodes were present in the test set, respectively.

Generally, datasets with a minority class proportion between 20% and 40% are considered to have mild imbalance, those with proportions from 1% to 20% are categorized as moderately imbalanced, and datasets with a minority class proportion of less than 1% are considered extremely imbalanced54. Based on this classification, TB and Breast cancer datasets had a mild imbalance. The Placenta, CoauthorCS, and Synthetic datasets demonstrated extreme class imbalance. The CoauthorPhysics dataset had a moderate imbalance.

Construction of cell graph

Edge construction in cell graphs estimates the biological likelihood that neighboring cells interact within the same structure. The edge threshold for intercellular communication is critical in cellular studies, and many investigations have aimed to determine the optimal distance for accurately modeling these interactions. Pathologists’ input provides valuable guidance to refine graph representations and ensure they accurately reflect the biological relationships between cells55. Many prior works have employed a single threshold value to map cell-cell interactions23,33, while some have experimented with varying edge thresholds, such as 60, 75, and 90 \(\mu\)m, to identify an appropriate threshold value56. In contrast, our approach uses distinct threshold values for each cell-cell pair,

In the TB dataset, nodes represent either AFBs or the nucleus of activated macrophages. Edge thresholds were based upon the length of cords of the M.tb infected cells after 72 hours of infection9 and the fact that macrophages can extend their pseudopods beyond their normal boundary (radius) to detect other cells farther away. We hypothesize that AFBs can interact with other AFBs within a distance of 150 \(\mu\)m, equivalent to 615 pixels at the magnification used in this study57. Likewise, activated macrophage nuclei may interact with both AFBs and each other if they are within 500 \(\mu\)m (2049 pixels)10. Our domain expert has thoroughly reviewed and validated these threshold values.

The adjacency matrix is computed as follows:

Distance denotes euclidean distance computing using the equation 1. The coordinates \((x_u,y_u)\) belongs to node ’u’ and the coordinates \((x_v,y_v)\) belons to node ’v’ in the image.

The distance threshold values are tabulated in the Table 1.

For the placenta dataset, the authors utilized the intersection of the K-nearest neighbors (KNN)58 and Delaunay triangulation59 graphs with a k-value of 5 to generate the cell graphs. In this graph, the nodes represented cells, and the edges depicted their interactions.

For the BRCA-M2C dataset, we constructed cell graphs where nodes represent cells and edges represent interactions based on the k-nearest neighbors (KNN)58 approach. Different k-values were used for each pair of cell types to reflect the biological significance of their interactions. The values used are tabulated in the Table 2. The adjacency matrix is calculated using the Eq. 2. The chosen k values were determined based on the cohesiveness of tumor cells and the solitary nature of stromal cells in tumors. Similarly, lymphocyte interactions were assigned moderate k values to reflect their intermediate proximity during immune surveillance, whether with tumor cells or among themselves. Figure 1 illustrates the cell graphs for various datasets.

Cell graphs of the TB and BRCA-M2C datasets were generated using the NetworkX library60 (version 3.4.2, https://networkx.org/). (A) Cell Graph generated for a TB image. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) cells are shown in red, and the nucleus of activated macrophages is depicted in blue. Black edges represent interactions. (B) Cell Graph generated for a normal lung tissue, i.e., not infected. (C) Cell Graph acquired from the Vanea et al.51, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). (D) Cell Graph generated from the BRCA-M2C dataset, where red nodes represent lymphocytes, blue nodes represent tumor cells, green nodes represent stromal cells, and gray edges denote their interactions, created using different k-values for specific cell interactions.

Are all these edges required?

While the cell graphs used in our study are generated by considering biological interactions, we acknowledge that they might not represent the optimal cell graphs. The edges in these graphs capture critical intercellular interactions. However, determining the optimal edges for such graphs remains an open research question. These interactions prove to be highly beneficial, particularly when the test set originates from a distribution different from the training set. Randomly removing edges from the cell graphs has been shown to hamper the teacher model’s performance. This, in turn, degrades the performance of the student models, as the quality of the teacher’s logits diminishes. The concept of optimal cell graphs with the right amount of connectivity to balance model complexity and performance remains an emerging area of research that requires further exploration.

Feature extraction

We tested the efficacy of our approach under different feature sets across datasets. We combined local cell graph features with morphological features for the TB dataset. For the Placenta dataset, we used only morphological features (along with inherent variations in cell appearance). For the BRCA-M2C dataset, we utilized only the local cell graph features. For the Coauthorship datasets, we did not extract additional features. Instead, we used the existing original features provided by the datasets.

TB dataset

In50, combining morphological and graph features resulted in the best results for CG-JKNN. Hence, we use this combination to train our models in this work. Table 3 denotes the extracted features; the description can be found in the paper that introduced it.

Placenta dataset

For the placenta dataset, we used the features defined in the original paper. Specifically, the node features are defined using the nucleus coordinates as node coordinates and the 64-dimensional embeddings from the penultimate layer of the cell classifier model. These features primarily encode morphological information about cells rather than cell graph structural information.

BRCA-M2C dataset

For the BRCA-M2C dataset, we extracted the local graph features from the cell graphs generated. The extracted features are listed in Table 4.

Distilling the knowledge from CG-JKNN (teacher) to tree-based ensembles (students)

Based on the CG-JKNN architecture, the teacher model is designed for node-level classification tasks. A graph is defined as \(G = (V, E)\), where V denotes the set of nodes, and each node v is associated with a d-dimensional feature vector \(x_v \in \mathbb {R}^d\). The edges E are represented by \(e_{u, v} = (u, v)\), indicating a connection between nodes u and v. The adjacency matrix \(A \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times n}\) encodes the graph structure.

The architecture of our teacher model and the flow of our proposed work are depicted in Fig. 2. To train the teacher GNN, we utilize cell graphs G constructed along with their associated node features \(x_v\). During the training phase, the model learns to classify each node by predicting its label based on the provided labeled graphs. During testing, the trained GNN receives unseen cell graphs G and their associated node features \(x_v\). The model predicts the test node labels, which are then compared against the true labels in the test set to evaluate performance.

Each node’s hidden features \(h_v^{(l)} \in \mathbb {R}^d\) in the l-th layer are initialized with the input features as \(h_v^{(0)} = x_v\). The GraphSAGE layers process node representations, employing a mean aggregation function as shown in Eq. 3 to gather information from neighboring nodes. In our previous work50, we experimented with both mean and max aggregators and found the mean aggregator to achieve superior performance consistently. This also aligned with prior studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of mean aggregation in node classification tasks61,62. Therefore, we selected the mean aggregator.

Here, \(h_{N(v)}^{(l)}\) represents the aggregated neighborhood representation, and \(h_u^{(l-1)}\) corresponds to the representation of neighboring node u from the previous layer. The node’s updated representation is computed using Eq. 4.

Here, W is the learnable weight matrix, and \(\sigma\) denotes the activation function (ReLU).

The “jumping knowledge representation learning” mechanism12 is incorporated to combine multi-layer node representations. This approach concatenates representations from all layers to form a comprehensive node representation (Eq. 5) instead of using only the final layer’s representation. The authors in12 explored three different aggregation mechanisms: concatenation, max-pooling, and an LSTM-based attention mechanism. Our network adopts the concatenation-based jumping knowledge mechanism for aggregating node representations.

After concatenation, the node representations are passed through a GATv2 layer63, which refines the representations using an attention mechanism. The attention coefficients \(\alpha _{vu}\) are computed as:

Finally, the node representations are updated as shown in Eq. 7, Later, the softmax function applied to obtain the class probabilities.

Here, \(\mathscr {N}(v)\) denotes the neighbors of node v, and \(\sigma\) is the activation function. We use a rectified linear unit (ReLU) as the activation function. Over-smoothing is a critical issue in GNNs. It arises when deep networks cause node features to converge, losing their distinctiveness. Existing approaches address this challenge using various strategies. Energetic Graph Neural Networks employ energy-based modeling64, while Graph DropConnect introduces graph-specific dropout65. Graph-coupled oscillator Networks use non-linear oscillators to modify GNN dynamics66, and residual connections improve the information flow in deep GNNs to counter over-smoothing67. For this study, we adopted the DropEdge technique68. It mitigates over-smoothing by randomly removing a proportion of edges during training. Using the edge index representation for graph connections, we experimented with various dropping rates.

Logits represent the unnormalized outputs of the model. It provides richer information compared to class probabilities. It has been shown in the literature that training the student model directly on the logits allows for more effective learning of the internal representations captured by the teacher18. This approach enables the student to mimic the teacher’s learned patterns better. Additionally, it helps avoid the information loss that typically occurs when logits are transformed into probabilities. Hence, we extract the logits before applying the softmax function for knowledge distillation and use them as labels to train the student regressor models.

In general, the KD loss69 is formulated to align the predictions of the student model with those of the teacher model by minimizing the divergence between their output distributions. This is typically achieved by leveraging the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence. While this approach is effective for neural network-based student models that undergo continuous updates during training, it is not directly applicable to our scenario. In our study, the student models are tree-based ensembles that do not rely on iterative gradient updates. As a result, we don’t utilize this loss function.

After training on the teacher’s logits as targets, the student models generate predictions, which are converted into probabilities using the softmax function. These probabilities are evaluated to calculate performance metrics such as accuracy and F1-score. We specifically chose non-linear models for students because the teacher logits, serving as labels, are inherently non-linear. For the student models to effectively learn from these logits, they must possess sufficient capacity (or complexity) to capture the underlying non-linear relationships embedded in the teacher’s predictions. We employ tree-based ensemble regressors as student models, as described in the Table 5. For brevity, we will often refer to these models by their specific names rather than repeatedly using the term ’regressor’ throughout the paper.

Estimating the complexity of tree-based ensemble models-an approximation and distillation quality score

Understanding the complexity of student models is essential to evaluating the quality of knowledge distilled from the teacher model. Black-box models, including various ensemble techniques, diverge from traditional likelihood-based frameworks and present challenges in directly assessing model complexity. This is mainly because the number of parameters in such models does not accurately represent their degrees of freedom. The concept of Generalized Degrees of Freedom (GDF), introduced by Ye70 and later applied to machine learning by Elder71, serves as a metric for assessing the complexity of models. For instance, in the case of a two-dimensional decision tree scenario, Elder71 has observed that combining multiple trees through bagging leads to an ensemble with a Generalized Degrees of Freedom (GDF) complexity that is lower than that of any single tree within the ensemble. In72, they employed GDF to estimate the number of parameters for the random forest model that was utilized to predict cell-type specific enhancer-promoter interactions by leveraging the information of protein-protein interactions between transcription factors.

Despite the utility of GDF in providing an estimate of model complexity, it has some challenges. Firstly, the sensitivity of GDF to perturbations in the data means that the degree to which GDF reacts can vary significantly depending on the specific modeling approach being used. This variability indicates that a GDF estimation method that works for one model type may not be suitable for another. In addition, the absence of a robust, universally applicable method for estimating GDF complicates its implementation across different data distributions and model architectures. These drawbacks highlight the complexity of accurately assessing model behavior in machine learning and the need for further research in developing more adaptable metrics like GDF73.

A standard metric for choosing models is the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)74, which illustrates the trade-off between model complexity and goodness of fit. Models with reduced AIC values indicate a better balance between the model complexity and goodness of fit. It is computed using the Eq. 8. \(M_{k}\) denotes the model with dimension k. \(L(M_{k})\) is the likelihood corresponding to the model \(M_{k}\)

However, one limitation of the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) is its unsuitability for non-parametric model selection75. Models such as Random Forest are non-parametric76. It is a common misconception that non-parametric models have no parameters. They can be thought of as having an infinite number of parameters. This characteristic suggests that the complexity of non-parametric models can grow to capture increasingly precise information within the data as the number of data rises76. Few papers have computed the AIC for models such as Random Forest in77. This study developed a machine-learning model to simulate the effect of masks on motor sound, utilizing noise level data in decibels from various operation frequencies of motors at the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC). Three group indicators were used to assess the learning performance: the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Hannan-Quinn Information Criterion (HQIC), the Schwartz-Bayesian Criterion (SBIC), and the Akaike Information Criterion with Small Sample Correction (AICc). However, based on the information provided, the specific method used to determine the number of parameters (‘k’) for the AIC score is unclear.

When models are estimated using maximum likelihood, the choice of model based on minimizing the cross-validation error leads to asymptotically equivalent decisions as selecting the model that minimizes the AIC78. Based on this, the authors in73 argued that it should be possible to extract a measurement from \(l_{CV}\) (which denotes the sum over K folds of the log-likelihood of the validation subset that estimates model complexity). The equation in 9 denotes the asymptotic equivalence between AIC and leave one out cross validation (LOOCV). Based on this, the number of parameters p can be estimated using the Eq. (11). \(l_m\) denotes the maximum log-likelihood of the original (non-cross-validated) model, and \(l_{CV}\) represents the sum over K folds of the log-likelihood of the validation fold.

In our work, we have employed tree-based ensemble regressors as student models. These are non-likelihood models. In73, the authors found the notion of applying GDFs to non-likelihood models to improve information-theoretic metrics of model fit (like AIC) was associated with the high cost of processing and produced inconsistent results. While cross-validation was a more direct method, it was less stable than GDFs. To determine the model complexity metric, they suggested repeated 10-fold cross-validation. Cross-validation is suitable for models that do not make likelihood assumptions since it can but need not, use the likelihood fit.

We build our methodology based on this idea. We utilize the sum of squared errors (SSE) to approximate the log-likelihood term. It suits our models that do not directly maximize the likelihood function. A higher maximum log-likelihood value indicates that the observed data is more probable under the model, which is interpreted as a better fit. A lower SSE suggests that the model’s predictions are closer to the actual observed values, which is also interpreted as a better fit.

Equation (12) shows the computation of model complexity with SSE. The \(SSE_{full}\) denotes the sum of squared errors on the training set, and \(SSE_{CV}\) denotes the SSE of the cross-validation. The logarithm helps to scale and normalize the SSE in relation to the number of observations ’n.’ In our experiments, we implemented a trial of 10-fold cross-validation recognizing the expensive computational demands of LOOCV. However, it does introduce some level of Monte-Carlo variability, resulting from not averaging all possible leave-one-out sets, as would be the case with LOOCV73. We observed slight variations in these estimates across different runs during our experiments. To ensure stable and reliable estimates, we recommend future researchers to conduct multiple runs, as suggested in73.

These terms capture the fit by indicating how close the model’s predictions are to the actual data points, with the logarithm helping to scale and normalize the SSE in relation to the number of observations. The supplementary files provide additional results on how model complexity changes under varying parameters. Henceforth, the term ’number of parameters’ for non-neural models in this study will denote the effective complexity,\(\hat{p}\).

Based on the complexity approximated, we compute the distillation quality metric, which measures the effectiveness of the distillation process. Inspired by79, we employ a slightly modified version of the distillation quality metric to evaluate the performance of various student models. Its computation is shown in equation 13. Instead of using accuracy, we use a weighted F1 score in our metric when dealing with imbalanced datasets.

\(\textrm{student}_c\) and \(\textrm{teacher}_c\) denote their respective complexities (in terms of parameters), and \(\textrm{student}_{f1}\) and \(\textrm{teacher}_{f1}\) denote their F1-scores (weighted). The approach of computing the number of parameters of our student models is described under section “Estimating the complexity of tree-based ensemble models-an approximation and distillation quality score”. The second term incorporates the max function to handle cases where the student outperforms the teacher. The authors in79 emphasize that the choice of the parameter \(\alpha\) is left to the designers, allowing them to prioritize either model size or accuracy according to their system’s requirements. For instance, a value of \(\alpha > 0.5\) would be appropriate if smaller model sizes are more critical. In our work, to balance the importance of model size and performance, we set \(\alpha = 0.5\), giving equal weight to these two factors. For balanced datasets, accuracy can be used instead of F1-scores to evaluate performance. In cases where the student outperforms the teacher, the ratio of student performance to teacher performance exceeds one. To address this, we have adjusted the score to ensure it remains non-negative. In our approach, a score of zero is achieved when the student model outperforms the teacher while maintaining a much smaller size than its teacher.

Ablation studies

We conducted three ablation studies, primarily focusing on cell graph data sets. The first study explored training with ensembled logits from the teacher and the best-performing student model. The second study aimed to analyze the differences in the importance of features when the models were trained using teacher logits compared to when they were trained using hard labels. The third study compares the effectiveness of transferring teacher knowledge via distillation into two types of student models: an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) and non-neural models.

Combining teacher and top student: ensemble model training

The goal of knowledge distillation from several teachers is to produce a good student who inherits the majority of the ensemble’s performance without raising the computational cost of inference. First, building highly predictive teacher ensembles is required to produce strong student models with distillation80. A few works focus on ensemble distillation on unlabeled datasets81,82,83. Since our study focuses on labeled data, we explicitly evaluate approaches relevant to labeled datasets for our distillation process, where the crucial problem is how to assign different weights to individual teachers within the ensemble81. In84, they proposed an ensemble model that unified three distinct knowledge distillation methods–feature-based, response-based, and relation-based on the CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 benchmarks. The distillation utilized a lightweight ResNet-20 student model with 0.27 million parameters and a ResNet-110 teacher model with 1.7 million parameters. The authors in85 trained an ensemble of various Multi-Task Deep Neural Networks (MT-DNNs (teachers)), achieving superior performance over any single model. Subsequently, they trained a single MT-DNN (student) through multi-task learning, effectively distilling knowledge from the ensemble of teachers. Wang et al.86 trained one segmentation teacher CNN on synthetic samples with accurately known ground truth fault labels and another classification teacher CNN on field samples with manually annotated labels. Following this, a classification student network was trained on samples created by aggregating the predictions from both teacher models through a voting mechanism. The authors in87 proposed MT-BERT, a novel approach to multi-teacher knowledge distillation focused on the compression of pre-trained language models. They devised a co-finetuning framework that simultaneously fine-tuned multiple teacher models employing a unified pooling and prediction module to align their output hidden states. This methodology enhanced the collaborative teaching of the student model. Chebotar and Waters88 discovered an effective ensemble of acoustic models comprising LSTM and CLDNN architectures developed with diverse training objectives, where the student model was a CLDNN. Initially, the research involved identifying the optimal fixed weights for merging the outputs of teacher models to maximize accuracy. The knowledge was later distilled into the student model using the soft labels generated by the ensemble. The authors in89 proposed a dynamic weighting approach for each teacher, demonstrating its effectiveness in logits-based and feature-based distillation through extensive experiments. They treated the process as a multi-objective optimization problem to find a more effective training direction.

For this ablation study, we consider both the CG-JKNN and the highest-performing student model as teacher models to investigate their combined impact on knowledge distillation. We adopt the methodology proposed in88, which involves identifying optimal fixed weights for merging the outputs of teacher models to maximize the F1 score on the validation set. Following this, we distill a student model from the ensemble output generated through this optimized combination. Equation (14) illustrates the method for aggregating outputs from the teacher GNN and LightGBM models. The detailed approach is shown in the algorithm 1.

\(L_{\text{ ensemble } }(x)\) is the ensembled output for a given input x. \(L_{g n n}(x)\) is the logit output from the GNN model for a given input x. \(L_{\text{ lightgbm } }(x)\) is the raw decision score output from the LightGBM model for a given input x. \(w_{\text{ gnn } }\) and \(w_{\text{ lightgbm } }\) are the weights applied to the outputs from the GNN and LightGBM models, respectively. It can be adapted to incorporate the outputs of other high-performing student models.

Feature importance: comparing students trained with and without teacher guidance

We aimed to analyze the differences in feature importance of student models trained on teacher logits and their counterpart trained on hard labels. Literature suggests that students trained on logits are better equipped to mimic the behavior of the teacher model18. Thus, this analysis can also serve as an approach to explore how a student model trained on logits may partially act as a proxy for interpreting the teacher’s decision-making process. For this experiment, we selected the student model that performed best on the held-out test set. To determine feature importance, we utilized the “feature importances” attribute of the model. Additionally, to assess how some of these important features contribute to predictions for each class and the direction of their impact, we employed SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) plots90. Our objective was not to compare these techniques but to leverage SHAP for a deeper understanding of how features influence model predictions. In future work, we plan to incorporate advanced techniques such as permutation-based methods (e.g., Boruta importance)91 and knockoff approaches92, as these methods provide a more robust and accurate assessment of a feature’s predictive abilities within a model93.

It is important to note that the student model can act as an interpretable approximation of the teacher by reflecting its emphasis on certain cell graph level or morphological features. However, it cannot leverage the graph structure and complex node relationships that the teacher model captures through message passing. Instead, the student operates solely on feature values and the logits provided by the teacher. It thus limits its ability to fully replicate the teacher’s reasoning process.

Comparing effectiveness of knowledge distillation into ANN vs. non-neural student models

In this ablation study, we selected an ANN as the neural student to ensure both model types rely solely on the features and implicit relational knowledge provided through the logits of the teacher GNN. This avoids the additional advantage of directly exploiting cell graph structures that a GNN would have and ensures that any observed differences in performance stem directly from the effectiveness of the distillation process.

We designed a shallow network with one hidden layer to maintain a smaller student model and its structure is illustrated in Fig. 3. The hyperparameters, such as hidden dimensions, alpha (which balances the two losses), and learning rate, were optimized using Optuna over 50 trials, selecting those that maximized the validation F1 score. We also constrained the hyperparameter search space to ensure that the ANN model parameters remained comparable to those of the non-neural student models.

Hinton et al.15 discovered that the effectiveness of the student model’s learning process is significantly enhanced when it is trained using both the soft target provided by the teacher model and the actual ground truth. This approach involves a combined loss function that integrates two key components: the traditional cross-entropy loss and a knowledge distillation-specific loss term.

The overall loss function for knowledge distillation can be expressed as shown in the equation 15.

Here, \(L_{C E}\left( p_s, y\right)\) represents the cross-entropy loss. The second component, \(\tau ^2 K L\left( p_s^\tau , p_t^\tau \right)\), is the knowledge distillation term. \(p_s^\tau\) and \(p_t^\tau\) denote the softened outputs of the student and teacher models, respectively, after applying the temperature scaling with parameter \(\tau\). KL stands for the Kullback-Leibler divergence, a measure of how one probability distribution diverges from a second, reference probability distribution. \(\alpha\) is a hyperparameter that controls the balance between the traditional cross-entropy loss and the knowledge distillation loss. In our work, we observed that logits before calibration already produced good results, and consequently, we set the temperature \(\tau\)=1.

Hinton et al.15 suggested using a weighted average between the distillation loss and the student loss by setting \(\beta =1-\alpha\), and in one of their experiments, they used \(\alpha =\beta =0.5\). Other works that utilize knowledge distillation treat this weight as a tunable parameter94,95,96. In our work, we treat the weight parameter \(\alpha\) as a hyperparameter. Additionally, we present results using a fixed \(\alpha\) value of 0.5.

Generalizability of knowledge distillation under various dataset complexities

To investigate whether all models benefit from knowledge distillation and assess the effectiveness of our approach across various dataset complexities, we conducted experiments on multiple datasets (cell graph and non-cell graph). These datasets presented challenges, such as distribution shifts, and structural complexities in training and testing graphs. Importantly, for Coauthorship datasets, we did not extract local graph features but instead utilized the original dataset features. This allowed us to test the efficacy of knowledge distillation in the absence of graph-specific features. The logits obtained from GNN trained on these coauthor networks could encapsulate rich information by reflecting relationships between node features (keywords) and the graph structure (Coauthorship network). For instance, if an author is involved in interdisciplinary work, their logits may encode soft probabilities across multiple fields, capturing the uncertainty or overlap between class labels.

Graph complexity

We hypothesize that for knowledge distillation to be effective when the teacher is a GNN learning from the graph, the graph must possess sufficient complexity. In such cases, the logits transferred from the GNN provide valuable information that student models can leverage.

According to the literature, graph complexity measures can be categorized into deterministic and probabilistic methods97. Deterministic approaches include Kolmogorov complexity, substructure counting, and generative models. Probabilistic methods involve entropy functions (such as Shannon’s entropy) applied to probability distributions over graph structures with intrinsic and extrinsic subcategories. In our work, we focus on graph energy, a concept originating from molecular and quantum chemistry, as a metric to evaluate how graph structural complexities affect knowledge transfer from a teacher GNN to student models98,99. It is computed using the Eq. (16).

Here \(b_k\) represents the edge weights if any, |A| denotes the number of edges in the graph, and \(\operatorname {SVD}(M)\) is a vector of singular values of the matrix M98.

Distribution shift in the data

The distribution shift100,101,102 can be broadly categorized into three types: Covariate shift, label shift, and concept shift. The feature distribution changes in the covariate shift case, while the label distribution does not. On the other hand, label shift happens when the distribution of the labels varies while the feature distribution remains the same. Concept shift, also called conceptual drift, arises when the actual relationship between the inputs and labels evolves, reflecting a change in the underlying concept the model is attempting to capture. There exist multiple ways to detect covariate shifts. We can compare summary statistics or employ dissimilarity measures like Earth mover’s distance. For statistical rigor, hypothesis tests such as the Kolmogorov-Smirnov or Chi-squared tests are used to determine significant distributional differences103.

For this work, we utilized Kernel Principal Components Analysis (Kernel PCA) for dimensionality reduction, selecting the number of components that captured above 95% of the dataset’s variance. Subsequent univariate Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, with Bonferroni correction104 applied to an alpha of 0.01, rigorously adjusted our significance levels to control the cumulative Type I error rate across multiple hypotheses. The mean of all significant KS statistics was computed to summarize the extent of covariate shift across the K dimensions. Moreover, for the computationally expensive TB and Placenta dataset, we subsampled 20,000 points to ensure the feasibility of the analysis while maintaining the representativeness of the original data. The mean KS statistic calculated may not fully reflect the entire degree of shift in the dataset. However, our primary goal was to demonstrate the presence of a shift.

To determine the covariate shift in non-cell graph-based datasets, we calculated the percentage of features with covariate shift by performing univariate KS tests directly on the scaled features. This was due to the high dimensionality of the dataset, as the large number of components required to achieve 95% variance capture would have made our initially proposed approach computationally expensive. For label shift detection, we employed the Chi-squared test105 to evaluate the consistency of class distributions between the different data subsets. This involved constructing a contingency table based on the frequency counts of each unique class in these subsets. After computing the Chi-squared statistic, we assessed the p-value to determine whether the observed distributional differences were statistically significant.

Can logit calibration enhance student guidance?

Neural networks produce poorly calibrated predictions that can be either overconfident or underconfident. GNNs can be miscalibrated too106. Calibration primarily aims to make predicted probabilities more reliable. In our study, we were particularly interested in investigating whether logit calibration could enhance the guidance provided to our student models. It is important to note that logit calibration does not impact the performance of the teacher model itself. Previous studies107,108 have demonstrated how calibration can impact models’ accuracy and other performance metrics. Additionally, the authors in109 introduced the concept of addressing mis-instruction through logit calibration. This work highlighted that enhancing target logits while preserving the relative proportions among non-target logits can significantly improve the utility of logits for knowledge distillation. These works primarily dealt with neural models as students. Wang et al.110 observed that GNNs tend to be underconfident, in contrast to the majority of multi-class classifiers, which are generally overconfident. This necessitated the use of various techniques to calibrate the logits. Guo et al.111 proposed temperature scaling to address the miscalibration issue found in modern neural networks. Kuleshov et al.112 introduced a straightforward calibration method based on isotonic regression. Another approach was ensemble-based temperature scaling113. Methods such as temperature scaling preserved accuracy by maintaining the per-node logit rankings unaltered114.

To achieve calibration, in this work, we employed isotonic regression and temperature scaling as post-hoc calibration methods. In traditional settings, isotonic regression is employed for binary classification tasks. To extend isotonic regression to multiclass scenarios, we adopt a one-vs-all strategy115,116. We measured the Brier score (Stratified) and negative log-likelihood before and after calibration, as they are proper scoring rules and provide a truthful measure of the accuracy of probabilistic predictions117. To learn the temperature T, it is considered best practice to use a validation set or perform cross-validation. We used 5-fold cross-validation (2 folds if the dataset is highly imbalanced) by splitting the training logits into train and validation folds. We learned two temperatures using the validation fold to optimize both the Brier score and the log loss. Our paper refers to the probabilities obtained after calibration using Eq. (17) as calibrated probabilities (calibrated probs). The overall score mentioned in the paper represents the mean of the scores calculated individually for each class.

where \(\hat{p}_i\) represents the calibrated probability for class \(i\), \(z_i\) is the logit for class \(i\) (pre-softmax output of the model), \(T > 0\) is the temperature parameter learned using a validation set or cross-validation, and \(C\) is the total number of classes.

Experimental setup and hyperparameters

We implemented the models using the PyTorch framework118 and ran them on one NVIDIA A100 GPU. The hyperparameters of the teacher model were chosen with the assistance of Optuna119, a Python library for hyperparameter optimization. We ran 50 trials to optimize the model hyperparameters, aiming to achieve the highest weighted F1 score on the validation set for imbalanced datasets. We used the cross-entropy loss function during training when the class imbalance was mild/moderate. We utilized a weighted cross-entropy loss function for scenarios with extreme class imbalance. The teacher model was run for 80 epochs. We used an Adam optimizer. The hyperparameters of the teacher model associated with each dataset are tabulated in Table 6. The features were scaled using the standard scaler. As performance metrics, we evaluated the accuracy and weighted F1 score. The temperatures used to calibrate the logits are also presented. The first temperature minimizes the stratified Brier score, The second temperature minimizes the log loss.

To maintain smaller student models, we set the number of estimators in the students to 6, with the maximum depth varying between 8 and 16 (such as 8,12,16, etc) and the number of leaf nodes fixed at 50. However, we allowed the number of leaf nodes to be 300 for our complex TB dataset. The learning rate of the boosters was set to 0.3, while all other parameters were kept at their default values. The specific depths of student models are detailed in the results section corresponding to each dataset. It is important to note that the student model performances reported are specific to the chosen hyperparameter configurations. We acknowledge that the results could vary with a more extensive hyperparameter search.

The edge homophily of the graphs used is shown in the Table 7. It is the ratio that measures the proportion of edges in a graph that connect nodes of the same class label. The equation to compute edge homophily is given in 18.

where: h denotes the edge heterophily score, \(|\mathscr {E}|\) is the total number of edges in the graph, (u, v) represents an edge between nodes u and v, \(y_u\) and \(y_v\) are the labels of nodes u and v.

As stated in120, a high edge homophily ratio indicates strong homophily where \(h \rightarrow 1\) while a low edge homophily ratio indicates strong heterophily where \(h \rightarrow 0\) .

Results

Covariate and label shift across datasets

Table 8 presents the Mean KS statistic, chi-squared statistics, and corresponding p-values for each dataset pair.

Based on the results, we observe a covariate shift in the test set of the TB dataset, as the test nodes are taken from separate graphs compared to the training and validation nodes. Additionally, the Chi-squared statistic indicates the presence of a label shift in the data. In the placenta dataset, we did not observe a large covariate shift between the validation and test sets, while a covariate shift is observed in other splits. This could be due to how the nodes were sourced. However, no label shift was detected in this dataset. This aligns with the findings in51, as the data splits were designed to ensure that tissue types have similar distributions across splits, and we adhered to the same splitting methodology. For the BRCA-M2C dataset, label shifts are observed across all subsets. As shown in Table 9, we did not observe label shift for non-cell graph datasets such as coauthor networks. In the Coauthorship networks, the percentage of features with covariate shift was nearly 0, indicating minimal distributional differences between the training and test datasets. The absence of substantial covariate shift in the coauthor networks was further supported by the performance of GNNs, where the test performance did not show a significant drop compared to the training performance. In contrast, a significant covariate shift was observed in the synthetic dataset generated by us, where 100% of the test features demonstrated a shift due to the Gaussian noise we introduced.

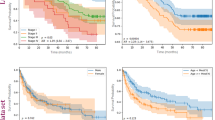

Performance of student models trained on TB dataset

For this dataset, the maximum depth for HistGradientBooster, XGBoost, Random Forest, and LightGBM was set to 12. For ExtraTrees, it was set to 16. As the dataset was complex, we set the maximum number of leaf nodes to 300. Table 10 represents the performance results of various models on the training, validation, and test datasets. We do see a drop in performance on the test set. This drop is attributed to covariate and label shift, as explained in detail under “Covariate and label shift across datasets”. Based on the comprehensive evaluation of various models, LightGBM achieved the best performance as a student model. HistGradientBooster emerged as the next best-performing model. Figure 5 displays the plot of the performance metrics for various models. We did not apply post-hoc calibration techniques, such as temperature scaling or isotonic regression, because the probabilities obtained from logits were reasonably well-calibrated. This is evident in Fig. 4, where the calibration curve is close to the diagonal. Moreover, in binary classification, the relationship between the predicted probability and the actual probability of the positive class is inherently more straightforward than in multi-class classification. Table 11 presents the distillation quality scores. The table shows that all student models exhibited performance gains, with each demonstrating a higher test F1 score than its counterpart trained on hard labels. Using teacher logits improves student performance by capturing important graph context. However, since the teacher directly leverages neighbor aggregation in the high homophily setting, students relying solely on node features may not fully match its performance. This is why we refer to these student models as partial proxies for the teacher. While the teacher-model architectures remain consistent with our prior work50, this paper (Table 10) presents an evaluation of these baselines on a slightly different dataset. Notably, all performance metrics are now computed globally across the entire dataset, unlike the batch-level average accuracy scores reported in50.

Performance of student models trained on placenta dataset

The dataset exhibited extreme class imbalance, so we employed a weighted cross-entropy loss while training the teacher model. The class weights were determined based on the recommendations provided in the paper51. These weights were applied to ensure fair treatment of minority classes during training. When training the student models using the logits from the teacher, we did not explicitly use these weights, as the logits already encapsulated the class imbalance information. However, we applied the same weights to maintain consistency and address the class imbalance to train the counterpart models that used hard labels.

For this dataset, the maximum depth for HistGradientBooster, Random Forest, and XGBoost was set to 12. For LightGBM and ExtraTrees, it was set to 16. Additionally, the maximum number of leaves was fixed at 50 for all models. The model performances are summarized in Table 12. As shown in their paper51, all scalable GNN architectures–GraphSAGE, ClusterGCN, GraphSAINT, ShaDow, and SIGN, performed within 2% mean accuracy of each other, with none surpassing 65% accuracy. This indicates that the challenges observed are not unique to our approach but are inherent to the highly imbalanced and complex nature of the dataset.

The calibration plots of logits for the teacher model, without using and using weighted cross-entropy loss, are shown in Fig. 6. We notice that the weighted cross-entropy rebalanced the teacher model’s focus. It improved the calibration for minority classes (Class 3 and Class 8) while causing a decrease in calibration for well-represented classes. Without the weighted cross-entropy loss, the teacher tended to favor majority classes, assigning more reliable probabilities while struggling to calibrate probabilities for the minority classes. Since our primary objective was to enhance generalization and ensure equal importance for all classes(critical for accurately representing placenta function), we employed the weighted cross-entropy loss during the teacher training. The calibration curves obtained after using weighted cross-entropy loss are shown in Fig. 7.

As highlighted in the paper121, the effect of temperature scaling in the presence of class imbalance has not been adequately explored. Our experiments found that using a temperature that minimized the log loss was not suitable. Instead, we relied on the temperature that minimized the stratified Brier score. Additionally, we observed that isotonic regression behaved unstably under extreme class imbalance. Specifically, Classes 3 and 8, being minority classes, exhibited disproportionately high scores. This observation aligns with the findings of122, where the authors noted that isotonic regression tends to perform unstably in highly imbalanced scenarios. We also found that calibration achieved using the temperature that minimized the stratified Brier score was superior to isotonic regression. This improvement was reflected in the performance of student models, as the temperature-scaled probabilities provided better guidance than the probabilities obtained from isotonic regression. The performance achieved with uncalibrated logits was higher than that obtained with calibrated logits after post-hoc calibration. We attribute this to the insufficient amount of data available per class, which is critical for the effectiveness of these calibration methods. This observation aligns with the findings of107, where the authors noted that post-hoc calibration methods require sufficient data per class to perform effectively. The stratified Brier scores are reported in Table 13. The temperature obtained through our temperature scaling process resulted in a worse stratified Brier score for the minority class 3. This highlights the limitation of standard temperature scaling in addressing class-specific miscalibration. We recommend an advanced temperature scaling approach designed to improve class-wise calibration which is necessary to address this issue effectively123. Contrary to expectations, using calibrated logits did not improve training set performance (eventhough the logits were specifically calibrated for this training set). We hypothesize that temperature scaling likely compressed the logits to an extent that it masked the tree model’s optimal decision splits. Given the dataset’s imbalance, the weighted F1 score is a more reliable metric to evaluate model performance. As observed from the plots, student models trained using teacher logits consistently outperform their counterparts trained on hard labels. Figure 8 presents a comparative analysis of the performance of the best-performing student models and their counterparts on the test set. Standard deviations are represented by the error bars.