Abstract

The proof-of-concept study for a hip and knee joint actuated exoskeleton developed for repetitive manual lifting and carrying tasks is investigated. Fifteen participants completed the study which involved two laboratory manual handling tasks of (1) lifting a box weighing 9.5 kg (repeated in three trials as a standalone task) and (2) lifting and carrying same box over a distance (repeated in three trials as a single combined task), with and without the use of the exoskeleton suit. Monopolar surface EMG sensors are utilized to capture participants muscular activity from two quadricep femoris muscles (i.e., the vastus medialis and rectus femoris) and a calf muscle (i.e., gastrocnemius) of the lower extremity. After each task repetition (trial), participants are asked to rate their perceived musculoskeletal effort on a scale of 0 to 100 (or 100%) where ‘100’ represents the highest possible participant effort. We determine the ‘onset’ of fatigue for each participant based on the trial at which fatigue was first experienced. The exoskeleton is found to reduce average muscular activity of the vastus medialis (30–60%), rectus femoris (30–38%), and gastrocnemius muscles (40–58%). Participants’ average rating of their lower-limb musculoskeletal effort when assisted by exoskeleton is found to be significantly less (26.9%) than their rating without the exoskeleton. However, subjective rating of fatigue differs significantly among the participants. These findings adds performance evaluation data for powered lower-extremity exoskeleton for strength augmentation in lifting and carrying works. Future studies should provide further insight into its potential use for prevention of cumulative trauma disorders of the lower-extremity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several industries (e.g., automotive, healthcare, logistics, rescue services sectors, etc.) engage in manual lifting and carrying activities1,2. These activities involve frequent squatting, lowering, knee bending, sitting/standing transition, and walking motions that put strain (and fatigue) on the lower limb musculature and lumbar spine (low back). Repeated strain and fatigue on the lower extremity muscles and joints are non-trivial and can lead to poor balance, fall, additional weight on the lumbar spine, and cumulative trauma disorders (i.e., musculoskeletal disorders) of the lower-extremities. These can result in long term mobility disabilities for affected workers or huge cost burden on employers3. Industries have long benefitted from conventional industrial ergonomic control measures (e.g., cranes, lifts, workplace modification, and training programs) to lower occupational injuries and increase productivity4,5. However, depending on the industry or work sector, these measures have not been sufficient as a significant amount of lifting and carrying activities are still performed6,7. In 2023, Malaysia reported 38,950 incidents of occupational injuries, up 13.8% from 34,216 cases in 2022. In 2022, the rate of occupational injuries per 1000 workers was 2.26 and in 2023, it was 2.46. These injuries are caused by a number of factors including load lifting and carrying activities. Workplace accidents have a big financial impact. The entire cost of work-related injuries in the United States in 2023 was $176.5 billion, which included administrative, medical, and wage and productivity losses. The cost per fatal injury was $1,460,000, and the cost of each injury that required medical consultation was $43,000. Indirect expenses can also add up, including administrative effort, training replacement employees, and lost productivity1.

Industrial exoskeletons are getting increasingly popular as supplements to conventional ergonomic control measures. They have promising advantages to benefit manural handling workers in areas where conventional ergonomic measures are insufficient or impractical. For example, unlike conventional measures, exoskeletons are wearable and can offer direct physical support to the user to relief musculoskeletal stress and strain, especially during physically demanding or repetitive jobs. Exoskeleton can enable workers to work over an extended period of time without experiencing fatigue thus improving productivity. Another important advantage of exoskeleton over conventional ergonomic solutions is flexibility. Exoskeletons are perfect for jobs that requires mobility because they move with the person, unlike stationary ergonomic solutions like cranes or elevators. Exoskeleton can also improve workers’ safety and security in restricted areas where conventional lifting equipment are impractical4.

By definition, an exoskeleton is a wearable robotic device that can augument human strength, endurance, and movement. It can increase mobility by moving in tandem with the user’s body, either passively or actively8,9. Many classifications of exoskeleton are possible. Depending on the supported body parts, they can be classified as lower-extremity, upper-body, or full-body exoskeleton. Based on function, they can be classified as assistive (for physically impaired persons), rehabilitation (for disabled persons), or augmentation exoskeleton for industrial use by able-bodied persons. This study covers the scope of lower-extremity augmentation exoskeleton for industrial use. These types of industrial exoskeletons can benefit able-bodied workers by decreasing lower body musculoskeletal strain on joints and muscles or by minimizing fatigue of the lower limb musculature7,8,9,10. Despite their potential benefits, the use of lower body exoskeleton in the industries are still not as widespread as compared to their upper-body counterpart. The lack of performance evaluation data and studies that showcase their overall benefit on the lower extremity hinders their potential use in the industries11,12,13,14. The literature is awash with studies (on upper-body and/or lower-body exoskeleton) that focuses on low back pain, which is a very common work related musculoskeletal disorder of the lumbar spine (often caused by lifting and carrying). However, an increasing number of studies have now shown that the impact of repeated load lifting and carrying activities—which can also involve repeated squatting and walking—on the lower extremity itself are non-trivial and can lead to musculoskeletal injuries of the knee and hip—e.g., knee osteoarthritis, hip osteoarthritis (OA), and meniscal knee damage15. Work related fall and swollen legs can also happen to workers due to fatigue and repeated overuse of lower limbs muscles1.

This study is thus motivated to evaluate the performance of a hip and knee joints actuated lower extremity exoskeleton robot for manual handling lifting and carrying task. The study seeks to understand numerically how much benefit (i.e., musculuskeletal effort/fatigue reduction) on the lower limb musculosketal system can be derived from the lower limb exoskeleton to add performance data for industrial application. To this end, the design of the exoskeleton is deliberately lightweight, approximately 10.78 kg without a bagpack, and the number of active and passive DoFs (12DoFs) are chosen to provide sufficient actuation (of the hip and knee joints) and to allow usability (ease of use) of the exoskeleton. We applied a control strategy that amplifies wearers’ effort (input joint torque) to move the exosketon in coupled human-robot motion. For details on the design and control strategy of the exoskeleton, the reader is directed to the ealier study reported here16.

Related works

This section presents some related works on lower extremity exoskeleton for activities involving lifting and carrying—which also involve squating and walking. For further study, the reader is directed to the review by13,17,18,19,20 that present a more comprehensive literature on lower extremity exoskeletons for industrial activities. There are a significant number of research that study the benefit of lower extremity exoskeleton to minimize lumbar spine injury or low back pain. In this context, it is important to mention that these studies are outside the scope of the current study which focuses on the impact of lifting and carrying activities on the lower body.

The RobotKnee LEE21 was one of the earliest device studied for the purpose of decreasing muscle activity of the quadricep femoris (hip-flexor/knee-extensor muscles) in task involving repetitive kneeling, squatting, and walking movements. The device applied torque across the knee to allow the user’s quadriceps muscles to relax, however design limitations hindered an effective evaluation of the device. For horizontal walking, the study by Lenzi et al.22 investigated the effect of a one leg powered hip augmentation exoskeleton (ALEX II) on 10 healthy participants, in load-free walking exercise. The exoskeleton is operated by a user-adaptable gait controller. The study found a significant reduction in muscle activity of several muscles including the gastrocnemius medialis (knee-flexor/ankle-planter-flexor) (45.0%), soleus (foot-planter-flexor) (15.1%), rectus femoris (hip-flexor/knee-extensor muscle) (22.3%), and semitendinosus (hip-extensor/knee-flexor muscle) (17.3%) in each last minutes of walking cycle. In contrast, the study by Sylos-Labini, et al.23 evaluating the effect of the MINDWALKER exoskeleton (weight 28 kg excl. batteries) on the lower-extremity musculatures of six healthy participants, in similar horizontal load-free walking exercise, found no significant changes in muscle activity of similar muscles and regions of the lower extremity including the quadricep muscles, the tibialis anterior (foot-dorsiflexor/inversion), medial gastrocnemius, and soleus muscles. Instead, they found activity of some muscles such as the biceps femoris (knee-flexor muscle) and semitendinosus (hip-extensor/knee-flexor muscle) to increase contrary to the expectation. Unlike ALEX II, the MINDWALKER was powered at the hip and knee joint and operated by a pre-defined trajectory-based controller to assist only walking motion. The conclusion from the study, however, suggest the possibility that users’ specific effect can impact performance of exoskeleton, for example, effect introduced if a user is not fully “relaxed,” needed to maintain the upper trunk posture by unintentionally modifying his/her step transitions, or disturbances caused by the intermittent contact between the exoskeleton and the subject. Study by24 presents the ankle exoskeleton’s improved design, which minimizes the mass of the struts and, consequently, the mass linked to the shin and foot. The main conclusions from the walking tests showed that walking with an exoskeleton reduced the activity of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles by up to 37% and 44%, respectively, as compared to regular walking.

For simple sagittal plane lifting and lowering tasks, the Robo-Mate Active Trunk LEE by Huysamen et al.25 was recently evaluated. Assistance were provided to the users at the hip via two series-elastic actuators. The study was motivated to investigate the effect of assistance on back muscles during the lifting and lowering task, however, they found slight reduction in muscle activity of the biceps femoris (a knee-flexor muscle) of the lower extremity by 5% (loads of 7.5 kg and 15 kg). In a similar lifting task (loads of 10 kg), the Hyundai H-WEX waist/hip-assisted LEE26, similarly motivated to study the effect of LEE on back muscle, found (moderate) reduction in muscle activity of the biceps femoris (a knee-flexor muscle) and gluteus maximus (hip-extensor muscle) of the lower extremity by 10–30%. The study did not find any significant effect on other muscles of the lower extremity including the rectus femoris (hip-flexor/knee-extensor muscle). Intuitively, assistance provided by LEE to the lower-extremity during a lifting task should enable several muscles of the lower extremity to relax particularly the hip flexor and knee extensor muscles (e.g., quadriceps, hamstring, or gastrocnemius) and thereby helping the user to benefit from assistance by the exoskeleton. However, there are still a number of open questions based on ongoing studies. The usability of the exoskeleton, comfort, flexibility of use, actuation power and the control strategies are important factors that can impact the performance of lower-extremity exoskeleton for industrial application. Also, a very important aspect but often not critically considered in many studies is the supported muscle-groups. Different tasks recruits specific muscle groups. Thus, to benefit from exoskeleton assistance for a specific task, the control effort and actuation mechanism should be deliberately directed to assist specific muscle groups for the specific task, otherwise the exoskeleton assistance can become counterproductive. For example, directing exoskeleton assistance to support the hip-extensor/knee-flexor muscles to reduce the strain on the lumbar spine in lifting task, or to assist hip-flexor/knee-extensor muscles to relax the quadriceps in repeated squatting activities in principle should result in the desired beneficial outcome.

Research hypothesis

We conduct this research with the hypothesis that the assistance (specifically on the hip and knee joint) provided by the lower extremity exoskeleton can minimize muscular activity, wearer’s musculoskeletal effort, and fatigue of lower limb musculature.

Materials and methods

Participants and ethics clearance

The University of Malaya Research Ethics Committee (UMREC) gave its clearance for this study. Prior to the trial, each participant provided written informed consent in compliance with the rules and ethics guidelines. The Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical principles are upheld by the University’s Guidelines for Clinical Trials. Participants were chosen at random from among various research facilities, production facilities, and workshops located around the university’s main campus. Initially, twenty healthy participants with no low-back pain history, no prior or current injuries/musculoskeletal disorders initially agreed to participate in the study. Five of the participants dropped out and were unable to perform the experiment since they could not fit properly into the exoskeleton. The participants who completed the study have ages 25–37 years, height 174–180 cm, and mean weight of 70–81 kg. Participants information is listed in Table 1.

Sample size determination

Sample size determination is crucial in experimental studies that require testing the effect of an intervention on sampled populations. The determination of sample size is influenced by the need for precision (for example, the need to attain 95% confidence interval for mean within \(\:\pm\:\delta\:\)units) or statistical power (for example, 0.80 or 0.90 statistical power (1 − β) for a hypothesis test). Validity and unbiasedness is not necessarily considered related to sample size27,28.

For a 2 × 2 crossover design AB|BA, the total sample size, n, required for a two-sided, α significance level test with 100(\(\:1\:-\:{\upbeta\:}\)) % statistical power and effect size \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{\text{A}}\:-{{\upmu\:}}_{\text{B}}\) is given as29

where \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{\text{A}}\) and \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{\text{B}}\) represent means for the direct effects of treatments A and B, respectively. This formula involves percentiles, \(\:{\text{z}}_{\:}\), from the standard normal distribution. The percentiles of interest for the two-sided hypothesis test with significance level \(\:{\upalpha\:}\) and statistical power (\(\:1\:-\:{\upbeta\:}\)) are \(\:{\text{z}}_{(1-{\upalpha\:}/2)}\:\)and \(\:{\text{z}}_{(1\:-\:{\upbeta\:})}\). For a one-sided hypothesis test, \(\:{\text{z}}_{(1-{\upalpha\:})}\) is used instead. The common choices for α are 0.05 and 0.01, and for \(\:{\upbeta\:}\) are 0.20 and 0.10, so the percentiles of interest are usually determined as:

Figure 1 shows an example of the 2.5th percentile and the 97.5th percentile on the normal distribution graph.

In (1), \(\:{{\upsigma\:}}^{2}\) denotes variance which is given as

where \(\:{W}_{AA}\) represent between-subject variance for treatment A (no Exo) and \(\:{W}_{BB}\) represent between-subject variance for treatment B (with Exo). \(\:{W}_{AB}\) represent between-subject covariance between treatments A and B; \(\:{\sigma\:}_{AA}\) represent within-subject variance for treatment A; and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{BB}\) represent within subject variance for treatment B.

Thus, to apply a 0.05 significance level test with 90% statistical power for detecting the effect size of \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{\text{A}}\:-{\:{\upmu\:}}_{\text{B}}\)= 1, from published results, if the investigator assumes that:

\(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{A}\text{A}}\:=\:{\text{W}}_{\text{B}\text{B}}\:=\:{\text{W}}_{\text{A}\text{B}}\:=\) x, and.

\(\:{{\upsigma\:}}_{\text{A}\text{A}}\:={\:{\upsigma\:}}_{\text{B}\text{B}}\:=\) 0.75.

The sample size is therefore n = 16 (from Eq. (1)).

Study design

Fifteen volunteers, not familiar with the investigated task, participated in this study after signing a consent form. A randomized counterbalanced crossover design was applied to analyse the exoskeleton conditions (with or without exoskeleton). This is to reduce the effects of fatigue that might occur from the first working phase (potential order-related effects)30. The recovery break period is also an important aspect to avoid these effects. All participants completed the procedure three times; in two different periods (with or without exoskeleton) as shown in Fig. 4. Participants rested for six minutes between one experimental condition and two minutes of recovery time in between tasks. To guarantee accurate evaluations of fatigue and usability, the duration and rest periods are specified. The participants had to perform the task at their preferred speed. A crossover repeated measurement design is motivated in this study to investigate the influence of the LEE on users’ lower extremity musculature. In the crossover design, each eligible participant in the study receive intervention in different modes (i.e., ‘without Exo’ and ‘with Exo’) during different time periods, and crossover from one mode (e.g., without Exo) to the other mode (e.g. with Exo) over the course of the trials31. In this way, each of the patients served as his own matched control, giving the possibility to eliminate users’ specific effects. Further, a “wash out” period of 6 mins is introduced between modes to eliminate any carry over effect (and bias) that may result from switching from one mode to the other32. The independent measure of the study is the intervention (LEE) presented in two modes: ‘without Exo’ and ‘with Exo’. In the ‘without Exo’ mode, the participants perform the task freely without wearing the exoskeleton, whereas, in the ‘with Exo’ mode, participants wear the exoskeleton and receive assistance from the device. The dependent measures are the mean and peak muscle activation, wearers perceived musculoskeletal effort (PME), and perception of fatigue (POF) experienced at the lower extremities.

Equipment

Lifted load

A box of load weighing 9.5 kg is used in the study. The weight conforms within the limit (0–25 kg) of acceptable weight exposure limits—considering the task’s duration, frequency, and severity—in the guidelines set out by NIOSH and ISO standards33.

Questionnaire

After each trial (i.e., with a total of 3 trials in a task), participants are given questionnaires to complete in order to gather quantitative feedback. The main feedback includes users’ rating of perceived musculoskeletal effort (PME) from the lower extremity musculature and ratings of Perceived onset of fatigue (POF) in each trial session34,35. Participants rating of PME are determined on a scale of 0 to 100, where ‘0’ represents ‘zero effort is contributed by participants while ‘100’ represents the highest possible (100%) participant effort is utilised. Participants’ perception of fatigue is determine on a scale of 0 to 1 where ‘0’ represents ‘no fatigue is felt in the trial’, while ‘1’ represents fatigue is experienced35. We then determine the ‘onset’ of fatigue for the task based on which trial or point during the task fatigue was first experienced by the participant on a scale of 0 to 3, where ‘0’ indicate “at no time was fatigue experienced for the task” and ‘3’ (100%) indicate onset of fatigue is perceived in the third trial of the task.

The robotic exoskeleton

The initial development of the powered lower-extremity exoskeleton is reported in36, where it was applied to assist prolong/repetitive walking movement. The current version is upgraded with additional degrees of freedom (DOF) to a 12-DOF exoskeleton with six link segments to support the lower extremity in lifting and carrying16 (Fig. 2). The total weight of the exoskeleton and that of the backpack are 10.78 kg and 1.89 kg respectively. Kinematically, each exoskeleton leg stands on six degrees of freedom: two degrees of freedom at the hip joint (one active and one passive), two degrees of freedom at the knee joint (one active and one passive), and two passive degrees of freedom at the ankle. The hip’s active DOF allows for flexion and extension movement on the sagittal plane, while its passive DOF allows for comfortable abduction and adduction on the frontal plane. The exoskeleton does not impede a user’s hip’s internal/external rotation on the transverse plane. In contrast, the knee’s active DOF is intended to promote flexion and extension movement on the sagittal plane, whilst its passive DOF permits a small amount of axial and lateral translation/rotation movement. The two passive joints in the ankle are designed to provide dorsiflexion and plantar-flexion movement on the sagittal plane and internal/external (abduction/adduction) rotation on the transverse plane. Additionally, the ankle module permits unrestricted frontal plane eversion and inversion movement.

All active DOFs are electrically powered by hollow shaft, back-drivable, bi-directional brushless DC (BLDC) motor types (Oriental Motor Inc.‘s BLH450KC-200 and BLH230KC-200). A torque of 34 Nm (power = 50 W and weight = 2.4 kg) and 17 Nm (power = 30 W and weight = 1.3 kg) are rated for the hip and knee joint actuation, respectively.

To enable different users to wear shoes of varying sizes, the exoskeleton’s foot module is made as a removable shoe. Additionally, it offers a way to direct the weight of the exoskeleton toward the ground. At the upper body, a backpack is firmly attached to the torso to host the data acquisition system (DAQ), electronics and communication unit (ECU). Other components of the exoskeleton suite include a torque sensor, ground reaction force (GRF) sensors and potentiometers for sensing.

Procedure

Before the experiment begins, volunteers receive instructions on how to operate the wearing LEE suit and how to utilize the power-down switch to turn the system off for safety in the event of an emergency or extreme pain. Regarding the familiarisation procedure, the live tutorial demonstration was given to the participant. This increased understanding and acceptance of the participants37. The volunteers were asked to familiarise themselves with the exoskeleton for three consecutive days, since all of them were not experienced in the use of the exoskeleton. 20 min were given to each participant to perform various task, such as simulating industrial lifting and carrying experiment until all of them acknowledged that they are familiar with the use of the exoskeleton. No detailed instructions were given during the familiarisation session. The experiments are divided into two tasks:

Task 1

The first challenge is a simulated industrial lifting task that requires an upright squat technique to raise a 9.5 kg box off the ground (Fig. 3). This is regarded as a single trial as it is repeated three times. Throughout the experiment, muscle activity data is recorded on specific muscles. Over several trials, the EMG peaks and the signal’s root mean square amplitude (RMSA) are estimated. Each participant completes three trials in total (Fig. 4), with a rest period of roughly two minutes in between to minimize muscular strain and potential confounders (body height or lower arm length, body mass index, and age)38. Two crossover periods—A for “w/o Exo” and B for “with Exo”—are used to complete the task (Fig. 4). There is a 6-min “washout” time (longer resting break) in between the cross-over periods (A and B). The questionnaire is also administered during this “washout” period, which also helps to reduce the impact of each intervention (such as the exoskeleton effect).

Task 2

A mock industrial lifting and carrying experiment is the second task. It involved squatting upright to raise the 9.5 kg weight (box) off the ground, walking a short distance on level ground (about 3 m), stooping again to lower the load to the ground, and then stepping back up to hoist another load. Both walking and squatting are used in this operation. As in Task 1 (Fig. 3), each participant is asked to complete three trials in two distinct periods (A: “w/o Exo” and B: “with Exo”) with a 6-min “washout” rest period in between. Two back-and-forth motions are regarded as one trial. Each participant’s questionnaires and EMG data are also recorded.

Surface electromyography

When a nerve stimulates a muscle, electromyography (EMG) detects the electrical activity or reaction of the muscle. Shimmer Sensing Technology’s EMG sensors are utilized to capture muscle activity data from two quadriceps femoris muscles, the vastus medialis (VM) and rectus femoris (RF), as well as one calf muscle, the medial gastrocnemius. All muscles are from the right leg. Figure 5 shows the setup of the EMG sensors. The EMG data were sampled at 1024 Hz. Monopolar surface EMG measurement procedure was used in this research to avoid the potential signal cancellations associated with bipolar method. The signal of EMG was acquired from the skin surface of the indicated area of the leg. The signal from the EMG goes to the signal acquisition and amplification unit for processing. Then the amplified signal goes to the PC for further processing. The preparation of the skin surface was adopted from39.

Data processing

The MATLAB software environment allows for offline EMG data processing, such as rectification, low pass filtering, linear envelope computation, normalization, and other data visualization. Raw EMG data is low-pass filtered by a third-order Butterworth filter (cut-off, 5 Hz) after linear envelopes are calculated from full-wave rectification of the band-passed EMG signals (third-order Butterworth filter, cut-off 20–512 Hz). After that, the EMG signals are divided into traces for every job. While the carrying task/activity is broken down into strides (heel-off to heel strike), the lifting task/activity (Task 1) is divided into lifting cycles (lowering and elevating). Appropriate intervals between traces are defined using the information from the in-sole ground reaction force sensor. For each trace and trial in both Task 1 and Task 2, the EMG signals’ Root Mean Square Amplitude (RMSA) and Peaks are calculated for each participant.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 23.0 is used for statistical analysis (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The impact of the independent factors/variables (at two levels, A—without Exo and B—with Exo) on each of the dependent measures was investigated using a repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a significance level of 0.05 for the EMG data. If necessary, a Bonferroni post-hoc multiple correction was used to compare any significant effects. The nonparametric Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test was used to evaluate the mean rank differences of participants’ perceptions (i.e., PME and POF) on the lower extremity with regard to the independent factors/variables because the questionnaire data were ordinal, ranked in the range of 0–10 for PME and 0–1 for perception of fatigue.

Results

Study of exoskeleton effect on muscular effort

Muscle activity

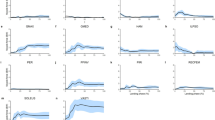

Figures 6 and 7 display the EMG signals obtained at the lower extremity’s right Vastus Medialis (VM), which is responsible for the knee extensor muscle; right Rectus Femoris (RF), which is responsible for the hip flexor and knee extensor muscle; and right Gastrocnemius (GA), which is responsible for the ankle flexor and knee flexor muscles, in both Task 1 and Task 2 studies. Mode A (i.e., without Exo, dark blue and green bars) and Mode B (i.e., with Exo, yellow and light blue bars) EMG RMSA/Peaks at the VM, RF, and GA are contrasted in the figures. Pi (i = 1,2,3, . 15) is the participants’ identifier. EMG Peaks correspond to the highest force produced by each muscle during a task movement cycle, whereas RMSA of the EMG signal represents the total effort expended during the task movement cycle. The findings indicate that when participants performed tasks without the assistance of an exoskeleton, their muscle activations increased. Figures 5 and 6 also provide the major effect comparison based on mean and standard error of mean for all participants (Pavg). The standard errors demonstrate the variability in the effect of exoskeleton help among subjects. Table 2 presents normalised EMG values and the statistical summary of the comparison of the effect of assistance between the ‘w/o Exo’ mode and the ‘with Exo’ mode for all participants. EMG signals are normalised to the peak muscle activation per muscle per participant (in a movement task cycle) to eliminate the disparity in strength amongst participants40.

VM RMSA decreased by 51.43% (p = 0.001), RF RMSA by 30.23% (p = 0.002), and GM RMSA by 40.63% (p = 0.004) for the lifting job (job 1) (Table 2) when comparing the helped to unassisted condition; VM peak decreased by 60.63% (p = 0.003), RF peak by 34.55% (p = 0.002), and GM peak by 40.74% (p = 0.018). The findings show that when aided by an exoskeleton, muscular activity/activation decreases. Under the aided scenario, the VM has the greatest obvious effect, while the RF has the least. Without assistance, VM showed the highest peak of activation during the lifting task based on computed mean from all the participants, followed by the RF muscle, whereas the least is seen on the GA.

When comparing the assisted condition (yellow and light blue bars) to the unassisted condition (dark blue and green bars) for the lifting and carrying task (Task 2) (Table 2), VM RMSA was reduced by 43.90% (p = 0.00003), RF RMSA by 37.78% (p = 0.003), and GM RMSA by 58.00% (p = 0.002); VM peak was reduced by 31.40% (p = 0.002), RF peaks by 31.30% (p = 0.0004), and GM peaks by 43.79% (p = 0.0002). The findings also show that exoskeleton support reduces average EMG RMSAs and muscle activity/activation peaks. The GA muscles show the greatest drop in muscular activity during Task 2, indicating that the exoskeleton assistance has the greatest impact on this muscle during the lifting/carrying task. Without assistance, GA and VM show strong activation peaks, whereas the RF shows the least.

EMG RMSA (dark blue and light blue bars) and Peaks (green and yellow bars) of the right vastus medialis (a), rectus femoris (b), and gastrocnemius muscles (c) for all 15 participants in the lifting task. Figure compares mean values attained in assisted mode (light blue and yellow bars) and unassisted mode (dark blue and green bars) of testing. Mean EMG RMSA and Peaks of all participants (Pavg) are shown on the right-hand side of each figure. Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean.

EMG RMSA (dark blue and light blue bars) and Peaks (green and yellow bars) of the right vastus medialis (a), rectus femoris (b), and gastrocnemius muscles (c) for all 15 participants in lifting and carrying task. Figure compares mean values attained in assisted mode (light blue and yellow bars) and unassisted mode (dark blue and green bars) of testing. Mean EMG RMSA and Peaks of all participants (Pavg) are shown on the right-hand side of each figure. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

A recurring action With dependent factors at three levels (EMG RMSA or Peaks at VM, RF, and GA) and independent factors at two levels (mode A, without Exo, and mode B, with Exo), ANOVA is utilized to ascertain the statistical significance of the effect of assistance on the fifteen participants. M (mean), MD (mean difference), SD (standard deviation from the mean), SE (standard error of the mean), and p (confidence level) are the statistical parameters that we specify. The null hypothesis regarding the influence of independent factors on dependent factors was rejected by the ANOVA at a 95% confidence level. With a 95% confidence interval for difference, a post hoc pairwise comparison using Bonferroni’s multiple adjustment for main effect shows a significant statistical difference between the types of help based on estimated marginal means. The EMG RMSA and EMG peaks for Task 1 show a significant statistical difference between the ‘w/o Exo’ and ‘with Exo’ groups (p = 0.00009). For Task 2, the difference in forms of assistance was found to be statistically significant for both EMG RMSA (p = 0.000006) and EMG peaks (p = 0.000005). Table 3 shows the overall pair-wise comparison (between modes) using Bonferroni’s adjustment.

The crossover design’s sequence effect (i.e., mode execution order—AB, BA) was not found to be significant in all movement tasks. A pairwise comparison with Bon-ferroni’s multiple adjustment revealed no statistical difference between the means of the sequences AB and BA for Task 1 (p = 0.807) and Task 2 (p = 0.526), implying that the order of execution had minimal carryover effect on the dependent factors or that the carryover effect had been significantly eliminated (see Table 4).

Participants’ feedback

Participants rating of PME

Participants’ perceived musculoskeletal effort (PME) is measured via questionnaires presented after each task. Figure 8 depicts participants’ subjective ratings, including the mean score and standard deviation of PME. Error bars represent standard deviations from the mean. The subjective evaluation is conducted in comparison to the effort experienced without exoskeleton help.

As shown in Fig. 8a, b, all participants reported using less effort to finish the lifting and lifting/carrying job when utilizing the supported mode (“with Exo”) as opposed to the none-assisted mode ( “w/o Exo”). Actual mean score of participants’ perceived musculoskeletal effort under the assisted mode is given by (M = 26.9%, SD = 12.2%) for the lifting task and (M = 27.3%, SD = 14.8%) for the lifting/carrying task. These scores represent a mean reduction in participants’ effort of approximately 73.1% and 72.7%, respectively (Table 5).

Participants perceived lower extremity musculoskeletal effort, PME (%), in (a) lifting task and (b) lifting/carrying task when assisted by exoskeleton. Subjective assessment is made in relation to effort experienced without exoskeleton assistance. Participant rating is based on the scale 0-100%. Mean musculoskeletal effort of all participants (Pavg) is shown on the right-hand side. Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean.

Participant rating of perceived onset of fatigue (POF)

In both tasks (lifting and lifting/carrying tasks), participants score of POF increase progressively from the first trial to the third trial of each task. Some participants however indicated no POF throughout the three trials of task repetition. For the lifting task, participants reported POF (on the hip/waist = 1, thigh = 1, and calf = 2) in the first trial without exoskeleton assistance. These rating increased in the second trial of task repetition (hip/waist = 6, thigh = 6, Calf = 5), as well as the third trial (hip/waist = 11, thigh = 10, Calf = 11). Table 6; Fig. 8 presents a summary of results. There is no report of subjective discomfort (i.e. pain, numbness, etc.) on any region of the lower extremity by participants with and without exoskeleton assistance. For the lifting and carrying task, participants’ score of POF at the hip/waist is (1st_trial = 0, 2nd_trial = 3, 3rd_trial = 9, n = 15), score of POF at the thigh region is (1st_trial = 0, 2nd_trial = 2, 3rd_trial = 10, n = 15), and POF score by participants at the calf region is (1st_trial = 0, 2nd_trial = 3, 3rd_trial = 9, n = 15). When task is performed with the help of exoskeleton assistance, reports of perception of fatigue were significantly minimal on the three regions of the body monitored. Participants reported POF only in the third trial of tasks repetition at the (hip/waist = 1, thigh = 1, calf = 0) for lifting, and at the (hip/waist = 1, thigh = 2, calf = 0) for lifting/carrying (Fig. 9).

Discussion

The current study was designed to verify the research hypothesis that muscular activity, perceived musculoskeletal effort, and onset of fatigue of the lower extremity can be minimised by providing exoskeleton assistance at the hip and knee. Findings from this study show that providing exoskeleton assistance at the hip and knee significantly decreased muscle activity of the quadricep muscles—the rectus femoris and vastus medialis—and gastrocnemius muscle in both lifting and lifting/carrying task.

The exoskeleton control strategy and actuation mechanism for this study (which is based on amplifying wearers input joint torque) enable assistive torque for hip and knee extension during upward standing from squat-lift and during walking movement; and for hip and knee flexion during downward squatting movement and walking.

The quadricep muscles are the primary movers of knee extension belonging to the hip-flexor/knee-extensor muscle group. Exoskeleton assistance in this context assist the quadricep to relax from bent knee to full extension (leg swing and hip flexion) during walking and from squatting to standing during lifting which gives the user a significant feeling of support on the lower limb with less effort required. This study found (30–60%) decrease in the muscle activity of the quadriceps muscles. The result is similar to study by KIM, et al.41 which found a decrease in muscle activity of the rectus femoris by (11–49%) using a knee actuated exoskeleton that assist knee flexion/extension movement; as well as the study by Lenzi, et al.22 which found about 22.3% decrease using a one leg powered hip exoskeleton (ALEX II) that assist hip movement during walking. However, study by Frost, et al.42 found (counter-assistive) increase in rectus femoris during squat (29–47%) and Free style lifting (38–83%) using a personal lift assistive device (PLAD). The exoskeleton use a series elastic elements to reduce lumbar moment during lifting and bending tasks which seems to have no signifiant benefit for activities of quadriceps muscles (Rectus Femoris). Also, study by Sylos-Labini, et al.23 using an actuated hip and knee joint exoskeleton and LEE26 using waist/hip actuated exoskeleton found no beneficial impact on muscle activity of the quadriceps. The outcome of the study seems to be significantly influenced by exoskeleton usability, flexibility and comfort for the wearer. See Table 7 for comparison of results.

The gastrocnemius muscle is a prominent calf muscle of the tricep surae. It is a powerful muscle belonging to the knee-flexor and foot/ankle plantar flexion muscle group. In this study, exoskeleton assistance support knee flexion minimizing activity of the gastrocnemius by (40–58%) during squatting which for example give the user the feeling like falling effortless during squatting. Study by KIM, et al.41 and Lenzi, et al.22 also found similar benefit for the activity of the gastrocnemius muscles with exoskeleton assistance by about (11–49%) and 45% respectively.

Feedback from users or their perceptions of exoskeleton assistance when performing the delegated task is crucial. In the study, exoskeleton assistance is found to corroborate with participants’ rating of musculoskeletal effort with some participants rating their effort to be very negligible when assisted by exoskeleton. Also compared to no assistance, exoskeleton assistance is seen to prolong participants onset of fatigue where only a few participants reported fatigue during the third trial. These feedback is very important moving forward with industrial application of exoskeleton.

Overall, activities of the lower extremity muscles and the impact of exoskeleton assistance on these muscles is still largely under-studied. A comprehensive understanding of the activities of different muscle groups of the lower extremity in relation to the strategy of exoskeleton assistance is important for industrial application of exoskeleton for manual lifting/carrying activities.

Economic of the research

The sector of the economy (e.g. logistics, manufacturing, health and construction) that relied on manual process stand to benefit from this research. The research can provide economic benefit in such as a way that it has the potential to reduce cumulative trauma disorders and musculoskeletal disorders typically experienced among workers performing repetitive task such as lifting and carrying. Such kind of disorders reduces the productivity of the workers, incur cost to the companies through healthcare services, compensation claims and lost of working days. Therefore, by reducing the muscular activity and fatigue or muscle activation, the exoskeleton can alleviate risk of injuries in the long-run, and consequently, reduces the company cost of healthcare services and compensation for workers. Workplace reduction of injuries by the use of exoskeletons can influence banking sector evaluation of corporate clients’ risk profiles especially for industries such as logistics, construction, and manufacturing. This means that low rate of injuries translate to low insurance premiums and few workers claims on compensation. The banks participating in partnership with insurance companies can benefit from more favorable actuarial models and reduced liability exposure likely leading to more competitive corporate banking packages.

This research demonstrated that participants perceived 73.1% lower physical effort during the use of exoskeleton and minimal fatigue even after repeated task trials. This finding indicate that employees can perform demanding tasks physically more effectively for long period while preserving physical well-being without compromise. In industries with high-demand where workers fatigue frequently contribute to reduction of output, the exoskeleton has the potential to significantly improve daily routine task and reduce the cost of mistakes or downtime which are typically caused by exhaustion or injuries. Therefore, enhancing labor productivity and efficiency of operations.

In societies where the aging population are increasing or where there are acute shortage of labor force, the exoskeletons can make older or physically less robust work-force of the population to continue to contribute in driving the economic sector in different roles especially in roles that are physically demanding. Therefore, preserving the labor force rate of participation in running the economic sectors and reducing the cost of workers re-training or replacement of injured workers. The industries that adopt technological measures for enhancing productivity such as exoskeletons are more likely to experience the retention of improved workforce, low level of absenteeism, and sustained operations. All of these factors typically affect cash flow and financial stability. For the banks that offer treasury services, lending of payroll or supply chain financing to these sectors, this translates into low risk and performing portfolios, more better.

From the viewpoint of macroeconomic, the massive acceptance and adoption of ergonomic exoskeletons has the potential to enhance national productivity and save cost of public health. Government can record a steady decline in disability as a result of sharp drop in workforce injuries. As such, reduces pressure on the healthcare systems. In addition, the study can support the growing of exoskeleton market, improving industrial diversification, encourage incease investment in research and development leading to creating new job opportunities especially in design, manufacturing and the maintenance of wearable devices. This makes the article not only relevant for occupational health but also impactful for economic development and technological advancement for competitiveness.

Limitations and future studies

A major limitation of this study is the number of muscles of the lower extremity that are monitored. Due to the convenience in the placement of EMG electrodes when users are wearing the exoskeleton suit, EMG data of only three muscles could be monitored with minimal interference either from the exoskeleton or the lifting/carrying activity itself. Our future work thus aim to enhance the study setup to allow more EMG signals to be recorded from many muscles of the lower extremity including the iliacus, psoas, rectus femoris, sartorius, pectineus glutes, hamstrings, and lower back.

For future work, the authors also aim to study the impact of this lower extremity exoskeleton on lower back to expand the scope of application of the exoskeleton in the industry.

Another important future work is to understand the relationship between the amount of torque assistance provided by the exoskeleton compared to the amount of reduction in muscle activity to enhance formulation of specifications for the industry. In line with this, the authors also aim to study the impact of different control strategies on a given muscle group of the lower extremity to forge a clear path for understanding, specifying and standardisation control strategies for the industry.

Conclusion

In this paper, the effect of a wearable lower extremity exoskeleton on the lower extremity musculature for lifting/carrying tasks have been investigated. The exoskeleton assistance is simultaneously provided on the hip and knee joint in a multi-joint actuation synergy during performance of the lifting and/or carrying task. Based on the current findings, the exoskeleton assistance impacted significantly on muscles of the quadriceps femoris and gastrocnemius as compared to most of the studies particularly on single joint hip assistance. Participant ratings of assistance from the exoskeleton (i.e., perceived musculoskeletal effort and perceived onset of fatigue) supports the possible use of exoskeleton to assist lifting and carrying jobs.

Data availability

The data is provided upon reasonable request. If someone wants to request the data from this study Dr. Sado Fatai should be contacted through abdfsado1@gmail.com.

References

Kim, I. J. Ergonomic assessment for work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a case study on office workers in two government organisations in the united Arab Emirates. Int. J. Ind. Syst. Eng. 47 (3), 334–353 (2024).

Holden, R. J., Cornet, V. P. & Valdez, R. S. Patient ergonomics: 10-year mapping review of patient-centered human factors. Appl. Ergon. 82, 102972 (2020).

Reiman, A., Kaivo-Oja, J., Parviainen, E., Takala, E. P. & Lauraeus, T. Human factors and ergonomics in manufacturing in the industry 4.0 context–A scoping review. Technol. Soc. 65, 101572 (2021).

Naranjo, J. E., Mora, C. A., Villagómez, D. F. B., Falconi, M. G. M. & Garcia, M. V. Wearable sensors in industrial ergonomics: enhancing safety and productivity in industry 4.0. Sens. (Basel Switzerland). 25 (5), 1526 (2025).

Аkulov, A., Zhelieznov, K., Zabolotny, О., Chabaniuk, E. & Shvets, A. Training simulators for crane operators and drivers. Eng. Today, 2, 1 (2023).

Golabchi, A. et al. A framework for evaluation and adoption of industrial exoskeletons. Appl. Ergon. 113, 104103 (2023).

Sun, L., Deng, A., Wang, H., Zhou, Y. & Song, Y. A soft exoskeleton for hip extension and flexion assistance based on reinforcement learning control. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 5435 (2025).

McFarland, T. & Fischer, S. Considerations for industrial use: a systematic review of the impact of active and passive upper limb exoskeletons on physical exposures. IISE Trans. Occup. Ergon. Hum. Factors. 7, 3–4 (2019).

Lee, H., Ferguson, P. W. & Rosen, J. Lower limb exoskeleton systems—overview. Wearable Robot. 207–229 (2020).

Wehner, M., Rempel, D. & Kazerooni, H. Lower extremity exoskeleton reduces back forces in lifting. In Dynamic Systems and Control Conference, vol. 48937, 49–56 (2009).

Vahedi, A. & Dianat, I. Industrial exoskeletons, challenges and suggestions in ergonomic studies. Iran. J. Ergon. 10 (2), 140–150 (2022).

Pinto-Fernandez, D. et al. Performance evaluation of lower limb exoskeletons: a systematic review. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 28 (7), 1573–1583 (2020).

Kuber, P. M., Alemi, M. M. & Rashedi, E. A Systematic Review on Lower-Limb Industrial Exoskeletons: Evaluation Methods, Evidence, and Future Directions, (in eng), Ann. Biomed. Eng. 51(8), 1665–1682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-023-03242-w (2023).

Pesenti, M., Antonietti, A., Gandolla, M. & Pedrocchi, A. Towards a functional performance validation standard for industrial low-back exoskeletons: state of the art review. Sensors. 21(3), 808 (2021). https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/21/3/808

Poochada, W., Chaiklieng, S. & Andajani, S. Musculoskeletal Disorders among Agricultural Workers of Various Cultivation Activities in Upper Northeastern Thailand, Safety. 8(3), 61 (2022). https://www.mdpi.com/2313-576X/8/3/61

Sado, F., Yap, H. J., Ghazilla, R. A. R. & Ahmad, N. Design and control of a wearable lower-body exoskeleton for squatting and walking assistance in manual handling works. Mechatronics. 63, 102272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechatronics.2019.102272 (2019).

Lee, H., Ferguson, P. W. & Rosen, J. Chapter 11 - Lower limb exoskeleton Systems—Overview. In Wearable Robotics (eds. Rosen, J. & Ferguson, P. W.) 207–229 (Academic, 2020).

Gull, M. A., Bai, S. & Bak, T. A review on design of upper limb exoskeletons. Robotics. 9(1), 16 (2020).

Karthik, V., Das, S., Nayak, S. & Pandey, A. Lower limb exoskeletons, Application-Centric classifications: A review. J. Field Robot. (2025).

Kuber, P. M., Alemi, M. M. & Rashedi, E. A systematic review on Lower-Limb industrial exoskeletons: evaluation methods, evidence, and future directions. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 51 (8), 1665–1682 (2023).

Pratt, J. E., Krupp, B. T., Morse, C. J. & Collins, S. H. The RoboKnee: an exoskeleton for enhancing strength and endurance during walking. In IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2004. Proceedings. ICRA’04. 2004, vol. 3, 2430–2435 (IEEE, 2004).

Lenzi, T., Carrozza, M. C. & Agrawal, S. K. Powered hip exoskeletons can reduce the user’s hip and ankle muscle activations during walking. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 21 (6), 938–948 (2013).

Sylos-Labini, F. et al. EMG patterns during assisted walking in the exoskeleton. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 423 (2014).

He, Y., Liu, J., Li, F., Cao, W. & Wu, X. Design and analysis of a lightweight lower extremity exoskeleton with novel compliant ankle joints. Technol. Health Care. 30 (4), 881–894 (2022).

Huysamen, K. et al. Assessment of an active industrial exoskeleton to aid dynamic lifting and Lowering manual handling tasks. Appl. Ergon. 68, 125–131 (2018).

Ko, H. K., Lee, S. W., Koo, D. H., Lee, I. & Hyun, D. J. Waist-assistive exoskeleton powered by a singular actuation mechanism for prevention of back-injury. Robot Auton. Syst. 107, 1–9 (2018).

Jones, B. & Kenward, M. G. Design and Analysis of cross-over Trials (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2014).

Li, C. S. & Davis, C. Des. Anal. Crossover Trials (2016).

Chow, S. C., Shao, J., Wang, H. & Lokhnygina, Y. Sample Size Calculations in Clinical Research (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2017).

McGibbon, C. A. et al. Evaluation of the Keeogo exoskeleton for assisting ambulatory activities in people with multiple sclerosis: an open-label, randomized, cross-over trial. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 15, 1–14 (2018).

Karunarathna, I., De Alvis, K., Gunasena, P. & Jayawardana, A. Designing and conducting clinical research: methodological approaches. J. Clin. Res. 1–13 (2024).

Coggon, D., Barker, D. & Rose, G. Epidemiology for the Uninitiated (Wiley, 2009).

Nur, N. M., Rahman, N. A. A., Majid, Z. A., Zulkefli, N. F. & Zuhudi, N. Z. M. Ergonomics risk factors in manual handling tasks: A vital piece of information. In Industrial Revolution in Knowledge Management and Technology, 1–8 (Springer, 2023).

Marzouk, M., McKeown, D. J., Borg, D. N., Headrick, J. & Kavanagh, J. J. Perceptions of fatigue and neuromuscular measures of performance fatigability during prolonged low-intensity elbow flexions. Exp. Physiol. 108 (3), 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1113/EP090981 (2023).

Hoffmann, N., Prokop, G. & Weidner, R. Methodologies for evaluating exoskeletons with industrial applications. Ergonomics. 65(2), 276–295 (2022).

Sado, F., Yap, H. J., Ghazilla, R. A. R. & Ahmad, N. Exoskeleton robot control for synchronous walking assistance in repetitive manual handling works based on dual unscented Kalman filter. PLoS One. 13 (7), e0200193 (2018).

Pacifico, I. et al. Evaluation of a spring-loaded upper-limb exoskeleton in cleaning activities. Appl. Ergon. 106, 103877 (2023).

Farris, D. J. et al. A systematic literature review of evidence for the use of assistive exoskeletons in defence and security use cases. Ergonomics. 66(1), 61–87 (2023).

Enoka, R. M. Physiological validation of the decomposition of surface EMG signals. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 46, 70–83 (2019).

Besomi, M. et al. Consensus for experimental design in electromyography (CEDE) project: checklist for reporting and critically appraising studies using EMG (CEDE-Check). J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 76, 102874 (2024).

Kim, W. S., Lee, H. D., Lim, D. H., Han, C. S. & Han, J. S. Development of a lower extremity exoskeleton system for walking assistance while load carrying. In Nature-Inspired Mobile Robotics, 35–42.

Frost, D. M., Abdoli, E. M. & Stevenson, J. M. PLAD (personal lift assistive device) stiffness affects the lumbar flexion/extension moment and the posterior chain EMG during symmetrical lifting tasks, (in eng). J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 19 (6), e403–e412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.12.002 (2009).

Luger, T., Seibt, R., Cobb, T. J., Rieger, M. A. & Steinhilber, B. Influence of a passive lower-limb exoskeleton during simulated industrial work tasks on physical load, upper body posture, postural control and discomfort. Appl. Ergon. 80, 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2019.05.018 (2019).

Luger, T. et al. A passive back exoskeleton supporting symmetric and asymmetric lifting in stoop and squat posture reduces trunk and hip extensor muscle activity and adjusts body posture—A laboratory study. Appl. Ergon. 97, 103530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2021.103530 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R178), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This study is supported via funding from Prince sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2024/R/1445).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.S., R.G., M.H.; Methodology: F.S., R.G., M.H., H.Y., W., N.A.; Software: H.C., L.G., F.S.; Validation: R.G., H.Y.; Formal analysis: All authors; writing-original draft: All authors; writing-review and editing: all authors; funding acquisition: L.G.; Supervision: R.G., H.Y.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the images in Figs. 1 and 2.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sado, F., Ghazilla, R.A.R., Hamza, M.F. et al. Ergonomic assessment of a multi-joint actuated lower extremity exoskeleton to assist dynamic lifting and carrying tasks. Sci Rep 15, 31868 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14747-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14747-w