Abstract

The passive transfer model of myasthenia gravis (PTMG) reflects the effector phase of the human condition and is induced in female rats using monoclonal antibodies. The current guideline recommends administration of monoclonal antibodies (mAb) such as mAb35 via intraperitoneal (I.P.) or intravenous (I.V.) injection, offering rapid absorption, but posing challenges such as injection placement and, in the case of I.P., animal discomfort. In this study, we investigated the suitability of subcutaneous (S.C.) administration as an alternative to I.P. in the rat PTMG model. Female rats were injected with 20 pmol mAb35 /100 g body weight (BW), either I.P. or S.C. and euthanized 48 h post-immunization, or S.C. with 20 or 40 pmol mAb35 /100 g BW and euthanized 48- or 72-hours post-immunization. Control animals received 0.5 mg/kg IgG1 isotype control S.C. or I.P. Muscle weakness, weight loss and clinical manifestations were assessed daily. Additionally, decrement-inducing curare dose and AChR content in the tibialis anterior (TA) were determined using electromyography and radioimmunoassay (RIA) respectively. S.C. mAb35 administration induced body weight loss and MG symptoms comparable to I.P. administration. However, I.P. injection presented a risk of misplacement, making it potentially a less reliable administration method. While MG characteristics were observed regardless of mAb35 dose and route, variability of clinical parameters and TA AChR content differed between approaches. S.C. induction of disease was verified using a different batch of mAb35 with a dose of 40 pmol/100 g BW S.C administered. We demonstrated that S.C. injection offers a consistent induction of PTMG, establishing it as a refined, effective alternative to I.P. administration by reducing procedural invasiveness and improving consistency in symptom onset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) with antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) is characterized by chronic, fatigable skeletal muscle weakness as a result of the loss of AChR at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). Its pathophysiology has been extensively studied, making MG a well characterized autoimmune disorder. Over the past decades, pre-clinical models have broadened our understanding of the underlying multi-faceted immune response of MG and advanced research to test novel therapeutic strategies.

The passive transfer myasthenia gravis (PTMG) model is induced by the parenteral administration of antibodies that target proteins expressed at the NMJ with the majority of these antibodies directed at the acetylcholine receptor (AChR)1. The source of these antibodies can be directly from MG patients or from animals that have been immunized with the antigen to develop the active immunization MG model, experimental autoimmune MG (EAMG). The passive antibody transfer model of MG was first described by dr. Toyka and collaborators in mice2,3. Since then, the PTMG model – in both mice and rats – has been used to demonstrate the pathogenic effect of anti-AChR autoantibodies (or other autoantigens of the NMJ) present in MG sera. The effector functions of MG patient autoantibodies are now well characterized, but the PTMG model remains important for testing MG treatments that counteract pathogenic effects of AChR antibodies. Several antibodies from EAMG animals, including mAb35, mAb3 and mAb198, have been cloned using hybridoma technology and are currently used for the development of the PTMG4,5,6. The consistent and reproducible clinical response in rats facilitates high model sensitivity and reduces the need for large sample sizes. Binding of the antibodies results in antigenic modulation and internalization of the receptor, and activation of the complement system, leading to the characteristic symptoms of muscle weakness of MG within 48 h after immunization7. The PTMG model is suitable to test novel therapeutic interventions targeting, for example, antibody turnover, competitor/blocking antibodies and complement inhibitors8,9,10,11,12,13.

Current guidelines recommend intraperitoneal (I.P.) or intravenous (I.V.) injection due to the rapid absorption, allowing a relatively quick onset of action1,14. Additional benefits of I.P. injection include a reduced risk of local inflammation and ability to inject larger volumes. For I.V. administration, the additional advantages are the precise control of pharmacokinetics and the possibility to use a lower dose due to the direct access to the circulation. While these methods have their advantages, other factors should be considered for selecting the appropriate route of administration. The intraperitoneal cavity contains several organs such as the liver, stomach and intestines as well as fat tissue. Together with the lack of visual confirmation of the correct needle placement, accidental puncture or damage to these organs are not uncommon and may lead to variable or unexpected outcomes and sometimes complications with acute discomfort as a result15,16. I.V. injections can be technically challenging as well and incorrect insertion or manipulation can cause vascular damage. Training and expertise are particularly important for a successful injection using both techniques. However, despite proper training and expertise, failures rates between 1 and 25% have been reported in the case of I.P. injections14,17,18,19.

A suitable alternative route is subcutaneous administration (S.C.). It is a robust technique that allows visual confirmation of correct administration, and presents less technical challenges, making it more accessible and reproducible. Another rationale for preferring the S.C. route over I.P. is the potential for localized, non-uniform antibody distribution following I.P. injection. Specifically, the diaphragm and adjacent abdominal muscles may be disproportionately exposed to autoantibodies by partial diffusion directly to the NMJ. In contrast, S.C. administration has a slower, but consistent and predictable absorption rate. This could lead to an overrepresentation of functional deficits in these muscles, thereby skewing disease severity. Furthermore, due to the lack of risk to damage organs, discomfort in S.C. injections is generally considered lower compared to I.P.

Although S.C. PTMG induction has been used20,21, no direct comparison has yet been made to assess whether S.C. administration can produce disease phenotype comparable in severity, onset and reproducibility to those achieved via I.P. administration. In this study we analysed S.C. administration as an alternative method to induce PTMG in rats, aiming to reduce procedural invasiveness and improving consistency in symptom onset. To this aim, we compared the S.C. route of administration to the standard PTMG by I.P. as described in the guidelines1. To account for potential variations in disease onset, we tested different mAb35 doses and variations in the disease timeline.

Results

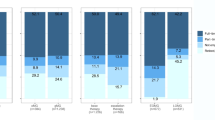

Subcutaneous administration of mAb35 induced dose and time-dependent development of PTMG

Typically, moderate to severe symptoms of MG develop in Lewis rats 48 h after I.P. injection of 20 pmol/100 g BW of mAb35. We hypothesized that a similar disease induction would also be possible with S.C. administration of the same dose. However, we also considered the possibility of a delayed or reduced uptake of mAb35, so we included two additional experimental groups: one experimental group of rats was injected S.C. with the same dose of 20 pmol/100 g BW and with a predefined endpoint of 72 h, and another group was injected S.C. with 40 pmol/100 g BW while maintaining the default endpoint of 48 h. We first investigated mAb35 levels in the circulation after S.C. or I.P. injection in serum samples taken 24 h post-immunization and at the endpoint. As expected, in all experimental PTMG groups, there was a significant uptake of mAb35 compared to the non-MG control group (Fig. 1A, B). In the I.P. administered group, there was one animal without detectable mAb35 in its blood. In combination with a clear lack of any clinical or pathological manifestations (data shown below), it was apparent that that this animal was misinjected. The data of this animal were excluded from statistical analyses but included in the graphs. While mAb35 levels were still somewhat variable at 24 h post-injection (Fig. 1A), mAb levels stabilized consistently by the predefined endpoint of the experiment, either at 48–72 h (Fig. 1B). When comparing 20 pmol/100 g BW I.P. and S.C., no substantial differences of mAb35 levels were found at any timepoint; however the group treated with 40 pmol/100 g BW had significantly higher serum levels of mAb35 compared to the other groups at 48 h.

Administration of mAb35 lead to a reduction in BW in all animals regardless of administration route at time of euthanasia (Fig. 1C). At 24 h post-immunization, a significant reduction in BW was found in animals receiving 40 ρmol mAb35/100 g BW compared to non-MG (P = 0.016), but not in other groups (Fig. 1C, D, Supplementary Fig. S1). At 48 h post-immunization, all experimental groups significantly differed from the control animals (Fig. 1C, E). The relative weight loss for PTMG animals reached 6.5–10.3% from baseline whereas non-MG animals maintained stable BW throughout the experiment (Fig. 1C, E), with a slight increase over time which could be due to daily variation or a result of local inflammation.

In line with the BW loss, the clinical score worsened over time, showing more frequently symptoms before exercise already at 24 h after immunization in the group S.C. injected with 40 ρmol/100 g BW (P = 0.077) (Fig. 1F). Clear symptoms of disease before testing were observed 48 h after injection regardless of the dose or injection method (Fig. 1G). No significant differences in disease severity were observed at any timepoint between experimental groups receiving different mAb35 doses S.C.

Two unexpected disease developments from the 20 ρmol/100 g BW S.C. 72-hour group were observed 48 h after immunization. One animal showed an overnight improvement from clear clinical signs before exercise to only exhibiting signs after exercise. The second animal was euthanized earlier due to humane endpoint (Fig. 1G). This animal was categorized with a disease score of 3 for further statistical analysis.

Progression of body weight and symptoms upon PTMG induction. mAb35 levels in serum at (A) 24 h and (B) at endpoint. (C) Overview of mean BW for each treatment group throughout the experiment. Error bars represent SEM. Daily BW measurements per experimental group at (D) 24 h and (E) at endpoint. Animals were clinically scored once per day for MG symptoms; (F) 24 h and (G) at endpoint. The grey circled data point is the misinjected animal in the mAb35 I.P. 20 ρmol 48 h group and has been excluded from statistical analysis. One way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test was performed for statistical analysis. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001 vs. non-MG S.C.+ I.P.

Grip strength is dose and administration route dependent

A reduction in grip strength was observed in all mAb35-treated animals within 24 h after administration (Fig. 2A). Animals receiving the higher dose (40 ρmol/100 g BW) of mAb35 S.C. had the greatest reduction in force compared to control (non-MG) animals at 24 h (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A). Some I.P. injected animals were similarly weak but, due to variability within the group, the mean loss of force was lower (P < 0.0001). At 48 h post-immunization, forelimb strength loss reached 86.5% ± 2.7 in the 40 ρmol/100 g BW S.C. animals, followed by a 55.4% ± 9.3 reduction in the 20 ρmol/100 g BW S.C. and 64.1% ± 17.8 for the 20 ρmol/100 g BW I.P. (Fig. 2B). Cohen’s effect size was calculated based on differences in rack grabbing strength to non-MG animals at endpoint, with the largest effect size observed in the 40 ρmol/100 g BW group (Cohen’s d = 0.98; Supplementary Table T3). Animals that were injected S.C. with 20 ρmol mAb35/100 g BW seemed to stabilize 48 h post-immunization, with no significant strength loss at 72 h (Fig. 2C). Although not statistically significant, a dose-dependent trend was visible at time of euthanasia.

Subsequently, muscle strength was assessed by the hand climbing task. The percentage of animals that completed the hand climbing started to decline 24 h after disease induction (Fig. 2D). All animals receiving 40 ρmol mAb35/100 g BW S.C. were unable to complete the task at 24 h. As the experiment continued, animals receiving the lower mAb35 dose S.C. also failed to complete the task. With the exception of 2 animals (20 ρmol/100 g BW S.C. and I.P. group), none of the mAb35 injected animals were able to complete the task at 48 h post-immunization and at time of euthanasia.

The effect of mAb35 injection route on muscle strength. Forelimb grip strength of treatment groups at (A) 24 h and (B) at endpoint and (C) overview of mean rack grabbing force during the experiment per treatment group at all time points from baseline to 72 h post-immunization. One symbol represents the average of five tasks. Errors bars represent SEM. (D) Proportion of animals that completed the hand climbing task at baseline, t = 2, 24, 48 and 72 h post-immunization. The grey circled data point is the misinjected animal and has been excluded from statistical analysis. One way ANOVA with Bonferroni test was performed for statistical analysis.***P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001 vs. non-MG S.C. + I.P.

Functional muscle AChR is reduced in mAb35 injected animals

The average decrement-inducing curare dose for non-MG animals was 11.3 µg ± 3.0 (Fig. 3A). With the exception of two animals, none of the mAb35 injected animals required curare (Fig. 3A). Subsequently, the total AChR content in the TA was determined by RIA. An average reduction of muscle AChR content was observed across all experimental groups. However, only the group that received 40 pmol/100 g BW mAb35 S.C. showed statistically significant differences with a reduction of 34.1% compared to non-MG animals (P = 0.002) (Fig. 3B).

Decrement-inducing curare dose and muscle AChR content quantification. (A) The intraperitoneally infused curare dose during EMG. The amount of curare was determined by infusion speed and total time to achieve minimally 10% decrement. The curare dose corresponds to the number of functional AChR in the endplates. (B) Total AChR content in the TA was analysed by protein extraction followed by RIA. The amount of AChR was normalized to tissue weight and non-MG S.C. + I.P. values. The grey circled data point is the misinjected animal and has been excluded from statistical analysis. One way ANOVA with Bonferroni test was performed for statistical analysis. **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001 vs. non-MG S.C. + I.P.

Validation study

To support the robustness of the adapted PTMG induction method, a second experiment was conducted with a new preparation of mAb35, using 40 ρmol/100 g BW for the experimental group (PTMG) and saline for the control animals (non-MG). PTMG animals showed a significant reduction (P = 0.013) in BW 48 h post-immunization, but not before (Fig. 4A). Mean BW loss for PTMG animals at time of euthanasia was 9.4% ±1.2 (Fig. 4B). Clear signs of disease appeared at 24 h post-immunization in PTMG animals (P = 0.012), while non-MG animals did not show any signs of muscle weakness throughout the experiment (Fig. 4C-E). Similar to the comparative study, the severity of disease reached a score of 1.4 ± 0.3 (P = 0.012) and 2.8 ± 0.13 (P < 0.0001) at 24 h and 48 h respectively (Fig. 4C, E).

Signs of muscle weakness as quantified by the rack grabbing task started approximately at 12–24 h post-immunization and were maintained through the whole experiment (Fig. 4F-H). At time of euthanasia, PTMG animals had lost 55.1% ± 6.6 force (P < 0.001), whereas non-MG animals gained strength (0.5% ± 4.0) (Fig. 4H). A large Cohen’s effect size (d = 0.82) was observed based on rack grabbing data at endpoint. Post-mortem analysis of AChR-content in the TA was in line with rack grabbing data, showing significantly lower AChR content in PTMG animals, with a 35% reduction (P < 0.0001) compared to non-MG, animals (Fig. 4I).

Validation of PTMG disease development using a different mAb35 batch. (A) Overview of mean body weight progression throughout the experiment. Error bars represent SEM. (B) Body weight measurements at endpoint (48 h). Clinical score at (C) 24 h, (D) 36 h and (E) endpoint. (F) Overview of mean grip strength by rack grabbing. (G) Grip strength at 36 h and (H) endpoint. (I) Total AChR content in the TA normalized to tissue weight and non-MG values. For statistical analysis a T-test was used. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001 vs. non-MG.

Discussion

This study provides evidence that S.C. immunization is a reliable method for inducing PTMG in rats. Administering mAb35 via S.C. injection led to BW loss and MG symptoms comparable to those observed with I.P. administration. We also showed that I.P. injections carry a risk of misplacement, making them potentially a less reliable administration method.

We hypothesized, based on general knowledge and previous drug studies with mAbs, that S.C. administration of mAb35 would have a slower absorption rate than I.P. administration22,23. To address any potential delay in disease onset due to absorption differences, we considered extending the duration of the experiment or increasing the dose. We expected the remaining circulating antibodies to reflect the amount of antibody bound to the NMJ. However, mAb35 serum concentrations and disease severity were similar between the different administration methods. To measure antibody absorption rate more accurately, blood samples would need to be collected more frequently within the first 24 h after immunization. One observable difference was that higher doses reduced inter-animal variability, likely because increased mAb35 availability accelerated NMJ degradation, leading to a higher and more uniform risk of neurotransmission failure and muscle weakness.

In line with previous experiments, we observed a reduction of only ~ 35% in AChR levels, as measured by RIA, yet clear disease symptoms were still evident in the animals24. We further validated our findings using a different preparation of mAb35. Despite differences in production and purification, S.C. administration still induced PTMG effectively with a similar disease severity. Given the small sample size in our pilot, the a priori estimated effect size was larger than the post hoc effect sizes in both the comparative and validation study. Nonetheless, the effect size remained large in both experiments, emphasizing robustness of the administration method. These results demonstrate that subcutaneous (S.C.) induction of PTMG is effective, and that the dose of mAb35 can be adjusted to suit the experimental purpose—particularly for studies requiring animals with a milder phenotype over a longer experimental period—provided that the group size is sufficient to account for variability. Since purification methods for antibodies vary between laboratories, we recommend testing the functionality of any new batch of mAb35 not only by protein level, but also functionally in immunoassays (ELISA or RIA for torpedo AChR) and ideally also in vivo.

We observed more variability in the I.P. injected group. I.P. administration is widely used in laboratory animal experiments due to the ability to inject larger volumes and ensure rapid absorption, however failures in injections have been reported at a range between 1 and 25%14,17,18,25. The accuracy of the failure rate might be compromised by the inability to visually confirm the injection, and misplaced injections can significantly affect experimental outcomes. In our study, one I.P. injected animal did not develop MG symptoms, likely due to a misinjection, creating an outlier. Due to the small group size, this outlier affected the statistical analysis and could have accounted for a reduced significance in the results. A key consequence of I.P. injection failures is the substantial increase in variability, requiring more animals to test a hypothesis compared to S.C. administration. This also raises the risk of false positive results in drug studies if any misinjection would occur in a drug-treated PTMG group. If not accounted for in power size calculations, misinjections in the PTMG model could falsely suggest therapeutic effects. We therefore recommend accounting for the potential misinjection rate in the power analysis when using I.P. administration, and suggest measuring antibody concentrations either by ELISA or by RIA to verify the efficacy of disease induction or alternatively using a suitable tracer to verify accurate delivery.

The study has several limitations including the lack of verification of the method using different mAbs, sexes and species. We used the female Lewis rat PTMG model as it is robust, reproducible and technically accessible, and because it has been widely used in previous studies, allowing for better comparison of outcomes across experiments. However, incorporating both sexes in future studies would enhance translational relevance of the model, as it would better reflect clinical heterogeneity. Additionally, given the advantage of using genetic and transgenic mouse lines, validating the PTMG model in mice would expand its applicability in MG. Another valuable extension of this work would be to use S.C. injections to induce PTMG in Lewis rats using patient anti-AChR antibodies. This would assess the polyclonal influence of the antibodies and help determine whether S.C. administration can elicit an immune response towards the human IgG. Such a PTMG model with human MG antibodies could be useful for testing therapeutic competitor antibodies such as described in the PTMG model in rhesus monkeys9,10.

The current study makes use of a novel non-standardized method for assessing muscle strength. While the rack grabbing task, as established in the guidelines, is a validated and quantifiable test providing continuous outcome measures, it showed limited sensitivity to changes in strength pre- and post-exercise. We replaced the post-exercise with a test that combines rack grabbing and hand climbing to capture a different aspect of muscle weakness in MG. Although the effectiveness of the modified test has yet to be validated in future studies, our data shows that it offers several potential advantages. Unlike standard rack grabbing, the combined task assesses whole-body strength and fatiguability, an often-underappreciated aspect of neuromuscular impairment in animal models. Its simplicity and minimal equipment requirements make it an accessible and practical task. However, it should be noted that this method remains semi-quantitative and is more susceptible to observer bias compared to the standardized rack grabbing test. Future studies should directly compare both approaches to determine their relative sensitivity and reproducibility for detecting disease-related muscle weakness.

We demonstrated that, given this variability and the lower likelihood of causing discomfort, S.C. administration is an effective, refined and reliable approach to induce PTMG in rats compared to I.P. administration. Regardless of the dose, mAb35 consistently induced BW loss, MG symptoms and muscle weakness. Importantly, these findings were validated with a different preparation of mAb35, highlighting reproducibility of the model. Despite MG’s well-characterized pathophysiology, the PTMG model remains relevant in this field of research and it is especially useful for investigating new therapeutic agents, such as complement inhibitor therapies, which is a growing area in autoimmune diseases and an essential step before heading to clinical trials in humans. Selecting subcutaneous over intraperitoneal administration not only aligns with ethical standards but also enhances reliability and reproducibility, ultimately facilitating the translation of preclinical findings to clinical applications.

Methods

Animals

Female LEW/Crl rats (n = 44) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany). We performed two studies; (1) 32 animals for the comparative study, where different mAb35 doses and disease course times were tested and (2) 12 animals for the follow-up validation study where the optimal dose and disease time course was confirmed.

Rats were housed in a reversed 12 h light-dark cycle, had ad libitum access to water and food and were fed a standard laboratory diet. Animals had a 2-week acclimatization period upon arrival at the Maastricht University animal facility. Subsequently, at 10–11 weeks of age, animals were trained for 3 consecutive days for the muscle strength tests. Animals were then distributed into different experimental groups with a similar average weight and these groups were used for induction of PTMG with mAb35 or served as non-MG isotype controls. Animals were euthanized by increasing isoflurane to 5% followed by cervical dislocation 48–72 h post-immunization, depending on the experimental group (Table 1). All experiments were conducted with approval of the Committee of Animal Welfare of Maastricht University, according to the Dutch laws and regulations (86/609/EU) under the following license AVD10700202216263, and in adherence to the 3Rs principle. All authors complied with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Monoclonal antibody 35 production, validation and quantification

Monoclonal 35 hybridoma cells (HB-8857) were purchased from ATCC and grown in suspension. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were obtained from serum-free cell culture supernatants. Presence of mAb35 in the medium was tested by dot blot using F(ab’)2 fragment goat anti-rat IgG Fcy fragment specific (1:5000, 2338144 Jackson Laboratory) and polyclonal rat IgG (10 mg/ml, I8015, Sigma) was used as standard curve for semi-quantitative analysis (Supplementary Fig. S2). Afterwards, supernatant was collected by centrifuging at 900 g for 10 min at room temperature (RT) and stored at 4 °C.

MAb35-containing supernatant was filtered using medium flow filter paper (1001-047 Whatman™), 0.45 μm sterile syringe filters (Millex) and dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Purity of the produced mAb35 batch was validated using the TGX Stain-Free™ FastCast™ Acrylamide Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Antibody concentration was determined by RIA using AChR extracted from rat tibialis anterior (TA) muscle. Radioactivity was measured in a gamma-counter and expressed in moles of 125I-α-bungarotoxin-binding sites precipitated per milliliter (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Disease inducing dose determination

The disease-inducing dose was previously determined by dose-response studies performed at CER Groupe, Belgium. Four animals were S.C. injected with either ~ 27 ρmol/100 g BW (0.04 mg/kg) or ~ 53 ρmol/100 g BW (0.08 mg/kg) mAb35 (Supplementary Table T1). Weight, welfare and symptom development by clinical scoring and grip strength at different time points (48–72 h after immunization). A dose of ~ 27 ρmol/100 g BW resulted in no symptoms 48 h post-immunization, while a dose of ~ 53 ρmol/100 g BW led to severe symptoms (Supplementary Table T1). To induce MG symptoms within 48 h and not exceed disease score 2, a mAb35 dose of 40 ρmol/100 g BW (0.06 mg/kg) was selected.

Experimental design and induction of passive transfer myasthenia gravis

Animals were distributed in 6 experimental groups in the comparative study based on dosage of mAb35 or IgG1 anti-β-Gal-rIgG isotype control (mabg1-ctlrt, Invivogen), injection method and time point of euthanasia (Table 1A). For logistical reasons the animals were equally distributed over 5 batches, with all experimental groups represented in each batch, that started the experiment subsequently, following the same timeline. For animals receiving S.C. injections, the primary site was the nape. However, if the volume would exceed the maximum injection volume of 1 ml it was evenly distributed over the nape and the flank using a cloth to restrain the animal. Injections were performed by one experimenter.

Animals underwent body weight measurements, grip strength test (rack grabbing and hand climbing) and disease and welfare scoring starting before immunization and continuing once a day after immunization until euthanasia. At time of euthanasia, electromyography (EMG) was performed, when required with curare infusion, blood sampling and post-mortem muscle collection was performed. All assessments were performed blinded.

In the validation study, PTMG was induced by injecting 40 ρmol mAb35/100 g BW (0.06 mg/kg) S.C. and control animals (non-MG) received a S.C. saline injection (Table 1B). Disease development was assessed at baseline and at 12, 24, 36 and 48 h after immunization. All animals underwent EMG, blood sampling and post-mortem muscle collection 48–72 h post-immunization.

Blood processing

Blood sampling from the saphenous vein took place at baseline (before disease induction) and 24 h post-immunization. At the end of the experiment, the maximum amount of blood was collected from the vena cava. To obtain plasma, blood was processed within 45 min after sampling by centrifuging for 15 min at 900 g at RT. Blood for serum was left for clotting for at least 30 min before centrifuging 10 min at 22,000 g. All samples were snap frozen on dry ice and stored at − 80 °C.

MAb35 in serum

MAb35 was determined in serum samples at 24 h post-immunization and at endpoint by ELISA8,11,26,27. Plates were coated with 10 µg/ml of purified AChR from Torpedo californica followed by blocking with 5% BSA in PBS for 1.5 h. Diluted serum samples in PBS (1:800) incubated 1.5 h on a shaker at RT. The secondary antibody goat anti-rat IgG HRP (Alpha Diagnostic 1:4000) was added for 1 h at RT. The tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (53-00-01, KPL) color development was stopped with HCl when blue color had developed. Three washes of 5 min in 0.05% Tween in PBS were performed after blocking, addition of the samples and after the incubation of the primary and secondary antibodies.

Clinical evaluation of rats

Disease assessment

Disease severity was daily assessed by general welfare scoring, body weight, disease specific scoring and motor function (Supplementary Table T2). The frequency of assessment was increased to twice a day if symptoms reached a welfare score of 7. Disease specific MG score was as follows: 0 = no disease symptoms before exercise; 1 = no clinical signs observed before testing, appearance of weakness after exercise due to fatigue; 2 = clinical signs present before testing, i.e. hunched posture, weak grip, or head down; 3 = severe clinical manifestation and (no ability to grip, hindlimb paralysis, respiratory distress/apnea, immobility) and strong weight loss of 15% or more from the maximum body weight recorded, leading to humane endpoint; and 4 = moribund1. Humane endpoint was defined by > 15% loss of body weight from the maximum recorded weight of that animal, not followed by recovery within a day and a combination of welfare score exceeding a score of 7 (Supplementary Table T2). Animals reaching humane endpoint were euthanized within 12 h of observation.

Muscle strength

Rats’ muscle strength was assessed using a grip meter to evaluate forelimb strength and the hand climbing task for overall strength and fatigability. These two tasks were combined into a single assessment, representing a modification of the guidelines1. While held by the base of the tail, the animal was placed with forelimbs on the grip meter GS3 (Panlab Harvard Apparatus, Barcelona, Spain) and pulled backwards 5 times following the axis of the sensor. Peak-force generation was recorded automatically. The average of 5 measurements was used for analysis. Subsequently, the animal was exercised with the hand climbing task. The experimenter held the rat by the base of the tail and allowed the rat to climb onto the dorsal side of the same hand while maintaining a 90° elbow angle. The experimenter’s arm and hand position remained fixed throughout the task to prevent interference with the animal’s movement. The exercise was repeated 5 times with 30 s resting intervals, lasting one attempt a maximum of 1 min. The number of successful climbs within the allotted time were noted. Animals that were able to climb all 5 times were categorized as successfully achieving the task. Correspondingly, not being able to climb up the hand led to categorization of failed.

Electromyography, curare infusion and organ collection

Rats received S.C. 0.05 mg/kg buprenorphine 1–4 h before the start of the terminal experiment. Animals were subsequently anesthetized by inhalation of 3–4% isoflurane and maintained under anesthesia at 1.5–3% isoflurane. EMG was performed as described using the Viking IV EMG system (Nicolet Biomedicals, Madison, WI)24,28. In short, using monopolar needle electrodes the nervus fibularis was repeatedly stimulated every 30 s for 8 times supramaximal (3 Hz, 0.2 ms per stimulus) and response was recorded on the TA muscle. When animals did not show decrement (the amplitude between the first and fourth CMAP reduced by > 10% for 3 consecutive recordings) within the first 10 min after inducing anesthesia, the animal underwent endotracheal intubation. The trachea was exposed and cut midway to be able to introduce the endotracheal tube. Using a mechanical ventilator (VentElite, Harvard Apparatus) attached to the isoflurane dispenser, the animal was mechanical ventilated and kept under anesthesia. Subsequently, a curare solution of 20 µg/mLl (T2379, Sigma-Aldrich) was infused I.P. using a Terfusion syringe infusion pump (model STC-521; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) at a rate of 0.33 µg curare/min. During the procedure, the animal’s body temperature was monitored using a rectal thermometer and kept between 36 and 38 °C using an infrared heating lamp (DISA, Copenhagen, Denmark) with adjustable power and a heating plate. The time and corresponding curare dose at which a decrement was observed directly correlated to the amount of functional AChR at the NMJ. The isoflurane concentration was then increased to 5% and blood was extracted from the vena cava. Animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation and TA muscles were collected snap frozen on dry ice for RIA. Tissue was stored at -80 °C until further use.

Radioimmunoassay for AChR content in tibialis anterior

The AChR concentrations of isolated TA muscles were measured as described before with the following modifications29. Three aliquots of 200 µl of muscle extract were prepared and incubated overnight at 4 °C with 125I-α-BT (Perkin Elmer, The US) and rat anti-torpedo AChR antibodies. Immune complexes were precipitated using 100 µl polyclonal goat anti-rat Ig (Eurogentec, Belgium). The measured radioactivity of 125I-α-BT correlates to the amount of AChR present, which was normalized to tissue weight and non-MG values.

Statistical methods

Power analysis was conducted using G*Power Version 3.1.9.6. The effect size (d = 2.6) which was a priori estimated using the reduction in rack grabbing strength observed between PTMG and non-MG animals in a pilot study, assuming a power of 80% and a significance level of α = 0.05 (two sided). Group sizes were calculated using d = 2.6 and Bonferroni-corrected α = 0.017, since we used multiple groups. To account for potential dropouts or technical errors (e.g., failed antibody delivery or data acquisition issues), a slightly increased sample size was chosen for the experimental groups (Table 1).

GraphPad Prism 10 was used to perform statistical analyses. Control groups were pooled after testing for insignificance using a t-test. Comparison between normally distributed values of non-MG groups versus experimental (PTMG) groups was performed using one way ANOVA. A Bonferroni test was applied to correct for multiple comparisons. For analyses excluding control groups, a one-way ANOVA comparing the average of all groups against each other was used with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Due to outlier status, one animal from the 20 pmol/100 g BW I.P. was removed from statistical analysis. For illustrative purposes this datapoint was kept in the figures. Statistical significance in the validation study was determined using a t-test. A two-tailed probability value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. We calculated Cohen’s effect size post hoc based on endpoint rack grabbing data (Supplementary Table T3).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MG:

-

Myasthenia gravis

- AChR-MG:

-

Acetylcholine receptor myasthenia gravis

- NMJ:

-

Neuromuscular junction

- PTMG:

-

Passive transfer myasthenia gravis

- I.P.:

-

Intraperitoneal

- I.V.:

-

Intravenous

- S.C.:

-

Subcutaneous

- mAb:

-

Monoclonal antibody

- EMG:

-

Electromyography

- TA:

-

Tibialis anterior

- BW:

-

Body weight

References

Kusner, L. L. et al. Guidelines for pre-clinical assessment of the acetylcholine receptor-specific passive transfer myasthenia Gravis model—Recommendations for methods and experimental designs. Exp. Neurol. 270, 3–10 (2015).

Toyka, K. V. et al. Myasthenia Gravis. N. Engl. J. Med. 296, 125–131 (1977).

Toyka, K. V., Brachman, D. B., Pestronk, A. & Kao, I. Myasthenia gravis: passive transfer from man to mouse. Science 190, 397–399 (1979).

Lennon, V. A. & Lambert, E. H. Myasthenia Gravis induced by monoclonal antibodies to acetylcholine receptors. Nature 285, 238–240 (1980).

Tzartos, S. J., Rand, D. E., Einarson, B. L. & Lindstrom, J. M. Mapping of surface structures of electrophorus acetylcholine receptor using monoclonal antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 8635–8645 (1981).

Tzartos, S. J., Kokla, A., Walgrave, S. L. & Conti-Tronconi, B. M. Localization of the main Immunogenic region of human muscle acetylcholine receptor to residues 67–76 of the alpha subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 85, 2899–2903 (1988).

Mané-Damas, M. et al. Novel treatment strategies for acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive myasthenia Gravis and related disorders. Autoimmun. Rev. 21, 103104 (2022).

Kusner, L. L. et al. Investigational RNAi therapeutic targeting C5 is efficacious in Pre-clinical models of myasthenia Gravis. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 13, 484–492 (2019).

Losen, M. et al. Hinge-deleted IgG4 blocker therapy for acetylcholine receptor myasthenia Gravis in rhesus monkeys. Sci. Rep. 7, 992 (2017).

van der Kolfschoten, N. Anti-Inflammatory activity of human IgG4 antibodies by dynamic fab arm exchange. Science. 317, 1554–1557 (2007).

Soltys, J. et al. Novel complement inhibitor limits severity of experimentally myasthenia Gravis. Ann. Neurol. 65, 67–75 (2009).

Song, J. et al. A targeted complement inhibitor crig/fh protects against experimental autoimmune myasthenia Gravis in rats via immune modulation. Front. Immunol. 13 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Anti-C5 antibody treatment ameliorates weakness in experimentally acquired myasthenia Gravis. J. Immunol. 179, 8562–8567 (2007).

Nebendahl, K. Chapter 24—Routes of administration. In The Laboratory Rat (ed Krinke, G. J.) 463–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012426400-7.50063-7 (Academic, 2000).

Turner, P. V., Brabb, T., Pekow, C. & Vasbinder, M. A. Administration of substances to laboratory animals: routes of administration and factors to consider. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 50, 600–613 (2011).

Steward, J. P., Ornellas, E. P., Beernink, K. D. & Northway, W. H. Errors in the technique of intraperitoneal injection of mice. Appl. Microbiol. 16, 1418–1419 (1968).

Arioli, V. & Rossi, E. Errors related to different techniques of intraperitoneal injection in mice. Appl. Microbiol. 19, 704–705 (1970).

Gaines Das, R. & North, D. Implications of experimental technique for analysis and interpretation of data from animal experiments: outliers and increased variability resulting from failure of intraperitoneal injection procedures. Lab. Anim. 41, 312–320 (2007).

Dörr, W. & Weber-Frisch, M. Short-term immobilization of mice by methohexitone. Lab. Anim. 33, 35–40 (1999).

Olesen, G. Development, characterization, and in vivo validation of a humanized C6 monoclonal antibody that inhibits the membrane attack complex. J. Innate Immun. 15, 16–36 (2023).

Lekova, E. et al. Discovery of functionally distinct anti-C7 monoclonal antibodies and stratification of anti-nicotinic achr positive myasthenia Gravis patients. Front. Immunol. 13 (2022).

Barrett, J. S., Wagner, J. G., Fisher, S. J. & Wahl, R. L. Effect of intraperitoneal injection volume and antibody protein dose on the pharmacokinetics of intraperitoneally administered IgG2a kappa murine monoclonal antibody in the rat. Cancer Res. 51, 3434–3444 (1991).

Goldenberg, D. M. et al. Properties and structure-function relationships of veltuzumab (hA20), a humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. Blood 113, 1062–1070 (2009).

Losen, M. et al. Increased expression of Rapsyn in muscles prevents acetylcholine receptor loss in experimental autoimmune myasthenia Gravis. Brain 128, 2327–2337 (2005).

Reimer, J. N., Schuster, C. J., Knight, C. G., Pang, D. S. J. & Leung, V. S. Y. Intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital has the potential to elicit pain in adult rats (Rattus norvegicus). PLoS One. 15, e0238123 (2020).

Quinn, A., Harrison, R., Jehanli, A. M. T., Lunt, G. G. & Walsh, S. An ELISA for the detection of anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies using biotinylated α-bungarotoxin. J. Immunol. Methods. 107, 197–203 (1988).

You, A. et al. Development of a refined experimental mouse model of myasthenia Gravis with anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Front. Immunol. 16 (2025).

Gomez, A. M. et al. Silencing of Dok-7 in adult rat muscle increases susceptibility to passive transfer myasthenia Gravis. Am. J. Pathol. 186, 2559–2568 (2016).

Losen, M. et al. Standardization of the experimental autoimmune myasthenia Gravis (EAMG) model by immunization of rats with torpedo Californica acetylcholine receptors — Recommendations for methods and experimental designs. Exp. Neurol. 270, 18–28 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BA, AKS and MMD performed behavioral experiments and collected in vivo data. ML assisted in data collection and provided technical support. LLK and PMS were responsible for execution of serum assays. BA performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to initial study design and commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arets, B., Mané-Damas, M., Schöttler, A. et al. Refinement of the rat acetylcholine receptor-specific passive transfer myasthenia gravis model using subcutaneous injections: an update to the guidelines. Sci Rep 15, 33062 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15187-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15187-2