Abstract

Patient flow management heavily relies on effective communication or transactions of situation awareness (SA) amongst hospital staff to minimize patients’ length of stay. Modelling SA transactions quantitatively could help identify inefficiencies and test potential solutions. This paper presents quantitative modelling of distributed situation awareness (DSA) with discrete event simulation (DES) and agent-based modelling (ABM) to capture and assess the transactions and distribution of SA for intrahospital transportation in patient flow management. The quantitative model was built on a qualitative DSA combined network for intrahospital transportation, observations, and historical data, followed by validation with t-tests by comparing transport time and number of patients transported between model outputs and historical data. Further, the model was used to test two proposed interventions for eliminating SA deficiencies revealed by prior qualitative DSA research: (1) updating the charge nurse before picking up patients, and (2) updating the X-ray unit before arriving. T-tests on the simulation results of 1500 replications revealed that the first intervention yielded significant reductions in mean transport time and cancelation rate, while the second intervention yielded a significant increase in transport time compared to the historical operational data. To our knowledge, this work is the first quantitative modelling research on DSA that is being assessed against operational data. The findings affirm that DSA is a promising framework for analyzing communication and coordination in complex systems and assessing system-level SA quantitatively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The literature continues to call for advances in theoretical and methodological foundations of situation awareness (SA) for studying and assessing sociotechnical systems1,2,3,4. Some approaches to study SA focus on individual level5 or team level6 that emphasize on psychological processes of individual or groups of human agents in “knowing what is going on”1,7,8,9,10. These theories are invaluable for understanding and supporting how to develop or acquire individual and team SA but they tend to consider machine or technology as some external artifacts rather than integral part of system level operations. Artman and Garbis11 first discussed SA at a system level, advocating that the entire system could represent the unit of analysis in which SA is distributed across human and non-human agents. Taking this systems perspective, Stanton12 formulated the Distributed Situation Awareness (DSA) theory that considers SA as an emergent property of the collaboration between all human and non-human agents in a sociotechnical system13. The DSA theory represents system level SA in terms of a network of information or SA exchange between human and machine agents for a set of tasks14.

DSA appears to be an effective theory for studying and assessing SA from a systems perspective as complex systems cannot be fully understood by studying parts in isolation because complex operations also rely on the interactions amongst human and non-human agents that must be analyzed collectively15. DSA research has presented descriptive models of different domains to illustrate that system-level SA can be meaningfully characterized by distribution and transactions of SA amongst agents12,13,16. Besides the description of system operations, Griffin et al. Griffin et al.17 employed qualitative DSA models to identify inefficient SA transactions for the Kegworth accident involving a Boeing 737–400. The model highlighted erroneous exchange of SA between the pilot and the engine instrumentation system about the engine fire to take proper actions. However, the existing research omits design implications from the description of DSA beyond identifying inefficiencies. DSA presents further opportunities, specifically in terms of testing and evaluating current and proposed systems designs for improving system-level SA that ideally would translate to system performance.

Quantitative DSA research

While abundant in qualitative evidence, DSA research lacks quantitative studies affirming the merits of the theoretical perspective and modelling techniques for improving DSA in system design and operation. To date, the literature appears to contain only two studies employing quantitative methods to study DSA. In the first study, Stanton18 employed Social Network Analysis (SNA)19,20 to characterize SA distribution and transactions between agents for the task of returning the submarine to a periscope level. In particular, SNA provided three metrics: closeness, which is the shortest path from one agent to every other agent in the network; betweenness, which is the frequency of an agent intercepting the path between two other agents; and emission and reception degrees, which are the number of ties emanating from and going to each agent in the network. The emission and reception metrics revealed that the Officer for Tactical System communicated over 40 times about close contact objects with the Sound Control Controller but less than eight times with the rest of the staff, thereby indicating the relative amount of SA transactions between agents. Further, the SNA indicated high betweenness for the Officer of the Watch, which served as a bridge to transmit SA from Warship Electronic Chart Display and Information System to Engineering Officers. The closeness metric was equally high for the Captain and Officer of the Watch, which meant both have to communicate with every member of the team. In summary, the SNA is an effective technique for modelling SA distribution and transaction between agents beyond the three-part qualitative modelling method proposed by Stanton et al.12. The emission and reception, betweenness, and closeness metrics in SNA provide quantitative characterizations and thus performance indicators of SA distributions across agents. However, the literature does not contain any studies on the correlation of SNA metrics with other DSA and performance indicators.

In the second study, Kitchin and Baber21 used agent-based modelling (ABM) to simulate 100 runs of hypothetical three-agent teams, assigned to detect vehicle passing through a tollbooth and report vehicle in legal violation based on vehicle shape, color, speeds, and zone. ABM simulated two types of agent interactions: (1) distributed reporting, in which agent X observes, agent Y decides, and then agent X acts to store the information (i.e., store the violation communicated by agent Y) while agent Z observes other possible violation; or (2) shared reporting, in which agent X observes and orients, agent Y decides, and then agents X and Z act to store the violation according to decision of agent Y. ABM results indicated that distributed reporting was both faster and more accurate than shared reporting of vehicles in violation. ABM could capture task characteristics, which can be altered for testing hypothetical interventions. However, this study was not based on any real-world operational data of complex systems and thus could only indicate feasibility of ABM for modelling and evaluating DSA.

Quantitative research has yet to deliver an assessment methodology of DSA or evaluation of any interventions in any real-world applications. DSA has only been studied quantitatively in a hypothetical and small scaled operation to demonstrate feasibility for comparing process designs. To attest any real-world merits of DSA for design, DSA modelling methodology must be developed and evaluated with real-world operational data and performance statistics to illustrate existence of DSA and assess the potential success of a design or intervention22. Thus, DSA requires advances in methodological research on building quantitative models at the same level of representativeness as the qualitative DSA research counterparts.

Overview of this research

This article advances quantitative DSA research by employing discrete event simulation (DES)23 and agent-based modelling (ABM)24 to model DSA and interventions for patient flow management of intrahospital transportation in level 1 trauma center. This research is built on the work of Alhaider et al.25 on a qualitative DSA model, which identified deficiencies and proposed interventions for the intrahospital transportation in same trauma center. This study employed DES and ABM for translating the qualitative model to quantify the impacts of the DSA deficiencies and potential benefits of the DSA interventions. This work thus connects qualitative and quantitative DSA research methods and provides a method for formal measurement and evaluation of DSA interventions for improving systems design in communication and coordination.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. The next section provides a background on modeling and simulation techniques in hospital settings followed by the quantitative modelling process. Then, the statistics testing of the simulation model and interventions testing are presented. The last section discusses the contribution of this research, and the benefits of incorporating simulation and modelling for quantifying impacts of potential interventions to improve SA distribution and transactions.

Background on hospital modeling and simulation

Simulation modeling has become an essential tool for analyzing hospital systems, providing evidence-based insights to improve patient flow, resource allocation, workforce scheduling, and operational efficiency. Various modeling techniques have been employed to study processes ranging from admission and discharge planning26,27,28, to triage and service coordination29,30,31, to diagnostic and therapeutic workflows involving shared equipment and staffing32,33,34. Simulation has also supported decisions regarding staff deployment under uncertainty35,36,37 and the performance of communication-based interventions38,39.These models differ in their methodological foundations but share a common aim of improving hospital function under resource constraints, dynamic patient demand, and variability in human performance.

DES is the most widely adopted method due to its capability to model hospital workflows in time-sequenced events involving queuing, scheduling, and resource assignment. Discrete event simulation (DES) models the system at discrete instances in time when the system state changes (e.g., arrived patient departs for a hospital unit for a procedure), allowing the user to test real-world and hypothetical operations and examine operational changes40. McGuire29 and Samaha et al.30 modeled ED patient flow to evaluate how triage processes and fast-track units affect throughput. Zeng et al.32 applied DES to radiology departments, showing that scanner availability and staff shifts directly impact service times. In the surgical context, VanBerkel and Blake41 simulated perioperative systems, illustrating how PACU delays create upstream bottlenecks in the OR. TariVerdi et al.26 used DES for a surge-response simulation across multiple hospital units, explicitly modeling bed capacity and nursing staff availability. Their findings revealed the importance of synchronized discharge and transport processes for alleviating congestion. DES has also supported evaluations of patient admission strategies during epidemic preparedness and the integration of smart logistics in hospital transport28.

Despite these contributions, DES typically models staff as fixed resources and does not capture the dynamic decision-making or communication between actors. Most implementations assume ideal or instant communication, limiting their ability to account for delays stemming from miscommunication or mismatches in situational awareness.

Agent-based modelling (ABM) complements DES by representing human actors as autonomous decision-makers who interact and adapt based on local conditions. ABM generates outcomes by simulating interactive behaviors with other agents and the environment24,42,43. Liu and Wu35 simulated accountability frameworks and showed how physician behavior and workload redistribution affected care quality and coordination. Majid et al.38 showed that ABM captured role flexibility and human variability more effectively than DES in complex workflows. ABM has also been used in hybrid settings to simulate personalized care planning and staff adaptation under variable patient conditions. However, ABM often abstracts operational details and may be challenging to validate without rich behavioral data. Hybrid simulation models integrate the precision of DES with the adaptability of ABM, offering a broader lens on both system dynamics and human behavior. Gunal and Pidd31 and Jacobson et al.44 developed multi-department hybrid models that track patients across EDs, inpatient wards, and outpatient clinics. These models were able to highlight systemic inefficiencies that arise from uncoordinated local policies. Vázquez-Serrano et al.45 also emphasized hybrid modeling as an emerging standard for capturing operational and behavioral dimensions concurrently. Still, most hybrid models continue to assume ideal communication and do not explicitly model breakdowns in knowledge sharing or awareness transfer.

While many simulation models have advanced understanding of hospital operations, several methods fall short when addressing dynamic coordination and human-system interaction. Methods such as queuing models27,46,47, Markov processes48,49,50, and Monte Carlo simulations51,52 have been widely used to evaluate patient wait times, resource allocation, and flow dynamics. However, these methods often rely on simplifying assumptions about steady-state conditions, independent arrivals, or homogeneous service times, which limit their adaptability to environments with dynamic arrivals, constrained spaces, and variable priority levels45,53. Small structural changes in the system often require substantial reworking of the models or reliance on approximation methods. Moreover, these models generally do not capture operational coordination, such as communication lags or real-time human decision-making.

Even more flexible approaches like agent-based modeling35,38,51,54,55 and system dynamics (SD)56,57 tend to abstract away resource and process-level granularity, and seldom account for the informational quality or breakdowns in distributed awareness. As a result, existing models offer limited support for evaluating coordination-sensitive processes such as intrahospital transport, where delays frequently stem from misaligned information rather than purely physical constraints. This gap highlights the need for integrated simulation frameworks that explicitly model both physical flows and the quality of information transactions among human and system agents. Other approaches include Petri nets have also been used to have to simulate patient flow and resource utilization, offering formal precision in capturing system dynamics and discrete event behaviors58,59. However, most hospital simulation models focus on material flows (patients, beds, equipment) and underrepresent the critical role of informational coordination.

While simulation studies have addressed numerous hospital processes, some operational domains remain particularly vulnerable to coordination breakdowns and are less comprehensively modeled. One such domain is intrahospital patient transport, which involves complex, time-sensitive movements of patients between care units, diagnostic services, and procedural areas. In this context, delays frequently result from asynchronous readiness, limited transport resources, and communication gaps between departments. Meephu et al.60 and Ermling61 both used DES to evaluate prioritization and scheduling strategies, showing that transport staff allocation, patient readiness timing, and task bundling significantly affect wait times and resource use. Vinicius et al.62 integrated DES with real-time scheduling to improve transport responsiveness and reduce idle time. However, these models assumed perfect information flow, overlooking the role of communication lags or awareness mismatches between units. As a result, they could not capture the informational coordination failures that frequently underline intrahospital transportation inefficiencies.

Across all model types, simulation studies have primarily emphasized the coordination of physical resources (e.g., patients, staff, equipment, and beds) while largely overlooking the quality of information exchange and communication handoffs. Yet, in time-sensitive processes like intrahospital patient transport, delays frequently arise from breakdowns in communication and misaligned situational awareness rather than physical constraints. Despite their known operational impact, knowledge transactions and awareness failures are rarely modeled explicitly in hospital simulations.

To address this gap, the present study integrates the DSA framework into a hybrid DES-ABM simulation of patient transport. Unlike prior models that treat communication as idealized or implicit, this approach explicitly simulates stochastic information handoffs and awareness breakdowns among agents. By linking communication success to measurable outcomes such as delay and cancellation, the model offers a novel way to assess coordination performance and inform hospital system design from a cognitive perspective.

Method

This study employed DES and ABM to simulate the current and hypothetical operations of interhospital transportation at a level 1 trauma center for studying and assessing SA distribution and transactions quantitatively. In this study, the DES model simulates all the tasks within the interhospital transportation as a series of discrete events while ABM complements DES by simulating various cognitive states (i.e., SA) and actions of the agents. Taken together, the integration of DES and ABM effectively can represent events as outcome of actions taken (i.e., task elements) by particular human agents (i.e., social elements) possessing specific SA (i.e., knowledge elements) that would comprehensively cover the three elements specified in the DSA theory. Portions of the methods and conceptual framework build upon the author’s earlier work63,64,65 with permission and appropriate adaptation for the present study.

The model in this study adopts a pragmatic approach to represent DSA, treating effective communication between agents—particularly the success or failure of critical message-passing—as a proxy for system-level SA. While formal definitions of DSA emphasize shared understanding, coordination, and the ability to anticipate events, our simulation does not directly track the cognitive state of each agent or their shared knowledge base. Instead, we infer that improved DSA is functionally reflected in better operational outcomes, such as reduced delays and cancellations. This proxy approach aligns with the limitations of our data and the operational focus of the study.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board (#17-383).

Modelling steps

This DSA simulation model focused on the processes of transporting patients and equipment between multiple locations, including the critical knowledge or SA communicated between agents as adapted from prior DSA modeling efforts63,64. The simulation model was developed with three major steps: (1) building a conceptual model, identifying processes and SA distribution and transactions; (2) collecting quantitative data through observations, interviews, and queries on a database; and (3) using DES and ABM to develop a quantitative model evaluating patient flow and DSA interventions.

Selection of processes and services

The services and process flows modeled in this simulation were selected based on their direct relevance to intrahospital transportation operations, as defined and overseen by the Carilion Transfer and Communication Center (CTaC; the hospital’s command and control center for patient flow). Inclusion criteria required that each process: (1) be actively coordinated by CTaC and the intrahospital transportation team in the hospital, (2) generate observable data within the patient flow management system (i.e., TeleTracking™), and (3) involve observable and measurable tasks and SA transactions between agents. Processes outside the transportation team’s purview (e.g., triage, discharge planning) were excluded, as they fall outside the operational responsibilities of the transportation team. This focused scope allowed for accurate measurement of transport-related performance and evaluation of DSA within CTaC’s operational boundaries.

Conceptual model development

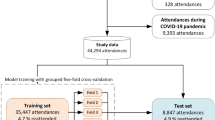

The conceptual model was derived from the qualitative DSA model of intrahospital transportation (i.e., combined network for clinical transportation) in Alhaider et al.25, as shown in Fig. 1, and further refined with additional interviews and observations. The intrahospital transportation team consists of dispatchers, team leaders, and transporters. The combined network in Fig. 1 captures the three elements of DSA (i.e., social, task, and knowledge) of intrahospital transportation when initially managed by CTaC. The network identified unnecessary task loops (dotted line) due to missing or inaccurate SA transactions when transporters arrive to pick up patients but are unprepared because ward nurses fail to provide the SA on patient needs, condition, and/or (hand-off) readiness. The operational data affirming this deficiency were captured by TeleTracking, which records patient transport services (i.e., time. location, completed jobs, cancelation/delay cause; refer to Alhaider et al.66. The analysis of SA interactions was informed by the Event Analysis of Systemic Teamwork (EAST) framework12,67, which has been widely used to model distributed cognition/SA in complex sociotechnical system. Observational data were analyzed to map agent interactions, knowledge requirements, and communication links, following procedures used in previous studies68,69,70.

Combined network illustrating DSA for the clinical transportation (i.e., intrahospital transportation) function. Black circles denote task and white circles denote knowledge. Acronyms beside circles denote agents, plain text is associated with task and italic text is associated with knowledge. The red dotted arrow indicates a task loop for rescheduling transports due to deficient SA transactions, specifically leaving information necessary for preparing a transport, the red circled SA/knowledge elements Alhaider et al.25.

To verify and refine the qualitative model (Fig. 1) for completeness of intrahospital transportation functions and accuracy, interviews involved CTaC intrahospital dispatchers, intrahospital transportation team leaders in the hospital, and clinical transporters, followed by eighteen hours of observation on the intrahospital dispatchers in CTaC and seventeen hours on transporters in the hospital. Figure 2 presents the conceptual model of processes (depicted by the small grey boxes), types of agents and communication between them (depicted by colored circles and arrows connecting them, respectively), and the SA of each agent (depicted by the dotted box inside each process)64.

Conceptual model for intrahospital transportation for picking up patients (one-way and round trip) and equipment at Carilion Clinic. Each solid box indicates a process accomplished to transport patients. Circles in each process refer agents involved and the arrow indicate the communication form (i.e., on-way or two-way) between agents. Dotted triangles in each process show the knowledge utilized in different colors referring to agents holding that knowledge. Large, dotted boxes resemble two major processes captured in TeleTracking named dispatch period (red colored) and patient period (burgundy colored).

The conceptual model depicts clinical/intrahospital transportation at the Carilion Clinic from transport request to patient drop-off at room/exams/discharge. First, the nurse placing the transport request (Np) starts the process of “created request (arrival)” (top left of Fig. 2) entering relevant SA about the transport request (i.e., patient or equipment information) into TeleTracking (TT). The transport request stays pending until a clinical transporter (CT) becomes available to pick up the request. For equipment, the CT obtains the information from TT (i.e., burgundy colored text in the dotted box) to determine where to go and what equipment is required. Then, the CT travels to the origin of the transport request to pick up the equipment from the technician (Tech) and proceed to the drop-off destination and inform the charge nurse at drop-off (Ncd) upon arrival.

For patient transport request, the CT obtains the SA on the transport from TT (denoted as burgundy colored text in the dotted box) to determine what are the necessary equipment (e.g., wheelchair, monitor, stretcher) and destination before traveling to the patient’s origin. Then, the CT travels to the patient and the process afterwards depends on the purpose of the transport:

-

1.

For medical service from the patient room in a one-way trip, the CT seeks SA from the department information systems (DISs) for the floor (i.e., white board, computer monitor, nurse at desk) to locate the Ncp. If available for hand-off, the Ncp communicates relevant SA on patient vitals and needs to CT, who ensures patient is ready for the transport. Then, the CT proceeds to preparing the patient for transport (that often involves disconnecting and connecting the patient to different medical equipment). The CT formally picks up the patent and calls the Virtual Care Center (VCC), the department which monitors patients, to confirm a successful pick up. The CT then transports the patient and transmits SA to the Ncd regarding patient arrival at destination, patient health conditions provided by the Ncp, and patient vitals from the Pm during the transport. Finally, the CT connects the patient to their medical equipment at destination and marks the transport as completed in TT.

-

2.

For discharge from the patient room in a one-way trip, the CT informs nurse at desk DISs (i.e., nurse at desk) without any involvement of the Ncp. The CT ensures completion of discharge paperwork, prepares the patient, and formally picks up patient. Then, the CT proceeds with the patient to the lobby/gate for drop-offs and marks the job completed in TT. The CT does not call VCC for pick up confirmation because discharge patients are not virtually monitored.

-

3.

For transport to and/or from a medical procedure or service (e.g., X-ray, Computed Tomography Scan) in a two-way trip, the CT starts hand-off with the Ncp to gather SA on patient and formally picks up the patient. The CT does not call the VCC for confirmation of pickup because post-service patients are not virtually monitored. For most of these patients, the CT connects the patient to a portable monitor (Pm) for monitoring patient vitals during the trip. Then, CT transports the patient to the destination or hospital unit performing the procedure and transmit SA to the nurse at exam (Nex) regarding patient arrival and vitals. The CT waits for Nex to indicate the completion of the procedure and prepares the patient for the return trip. Finally, the CT transports the patient back to origin of the transport and transmits SA to the Ncd regarding patient arrival, changes in patient vitals or conditions during the trip or procedure to Ncd. The CT also connects the patient to the medical equipment in the room and then marks the job as completed in TT.

Simulation model development

In this study, DSA is operationalized through the success or failure of information transactions, specifically whether critical cues reach the appropriate agent at the right time. This approach serves as a pragmatic proxy for system-level DSA, focusing on measurable outcomes in the intrahospital transportation process, such as delay and cancellations, which reflect the effectiveness of SA transactions. The model emphasizes dyadic communication protocols (e.g., nurse-transporter hand-offs) due to their critical role in the transportation workflow, as captured by TeleTracking data and observations. While this approach does not directly measure the distribution of shared knowledge elements across all agents or allow compensatory SA sharing, it aligns with the study’s objective to quantify the impact of SA transactions on operational performance in a complex sociotechnical system.

Data collection

To translate the conceptual model into a simulation model, operational data were extracted from a hospital historical database via TeleTracking while SA transaction and accuracy data were collected by observations as described in previous data collection protocols64.

Transport time data from TeleTracking patient flow management system

The TeleTracking data provided the following seven types of operational data on intrahospital transportation from February 2020 to September 2021:

-

1.

Transport request origin and destination (transport count): Every transport request was defined by origin and destination location. The data showed the count of trips from origins of transports from TeleTracking and their destinations. These values were used to assign percentages on the destinations for each origin (in creating job requests/arrival rates as described in subsequent sections).

-

2.

Transport request time stamps: The transport request time stamps were used to compute arrival rates of every type of transport requests as defined by the origin and destination (Fig. 2 depicted a job request as “create request”).

-

3.

CT worker names: The names of CT assigned for every transport job were used to estimate the number of transport workers in different shifts. The simulation model included twelve two-hour shifts per day. The number of workers per shift was estimated by number of distinct workers names during those hours.

-

4.

Patient transport time: Patient transport time is the duration of transporting patients to a unit as represented by the dispatch period and patient period. Dispatch period is the duration between the time when CT accepts the request and picks up the patient whereas, patient period is the duration from patient pick-up to job completion. Patient transport time is the summation of the dispatch period and patient period.

-

5.

Equipment transport time: Equipment transport time is the duration for transporting some equipment to a unit. Equipment pick-up period is the duration between the time when CT accepts the request and picks up equipment. Equipment drop-off period is the duration from equipment pick-up to transport completion. Equipment transport time is the summation of the Equipment pick-up period and Equipment drop-off period.

-

6.

6. Transport status: The transport status indicates whether a transport (grouped by the origins) was completed, delayed, and canceled. For delayed and canceled (i.e., deficient) transports, the CT also entered a pre-scripted reason (Table 1).

Table 1 Definitions of deficiency reasons.

The proportions of transport status and pre-scripted reasons for deficient transport were computed for the simulation based on transport data of patients and equipment across different origins and destinations. The transport data were used to compute discrete probability (or multinomial) distributions for assigning status to the transport job requests in the simulation (Table 2).

Transport requests in TeleTracking system may be canceled due to various operational constraints as shown in Table 1. Each canceled request is logged with a specific status and deficiency reason. If re-requested, the transport is assigned a new trip ID and treated as a separate event. In this study, canceled and repeated requests were not merged but analyzed individually to reflect their distinct impacts on resource use and workflow, consistent with how they are recorded and managed in practice.

-

7.

Delay time. The delay time shows the duration for every pre-scripted reason of deficient transport that would be added to the normal transport time (i.e., the transport time of a non-deficient transport).

In this simulation, destination capacity is indirectly incorporated through the workflow defined by Carilion Clinic’s TeleTracking system. A transport request is only generated once the destination confirms availability and readiness to accept the patient. This reflects actual hospital operations, where only the receiving unit can authorize transport, and sending units, such as ward nurses, cannot initiate requests on their own. As a result, bottlenecks caused by downstream capacity constraints are naturally reflected in transport delays or cancellations recorded in the data.

SA data from observations

The TeleTracking patient flow management system does not capture any data on the sub-processes carried out during the dispatch and patient periods in which SA elements were being transacted between agents to minimize the risk of delays and cancelations. To simulate SA distribution during the dispatch and patient periods, clinical transport staff were observed and followed during the daytime shift (10 am–4 pm) at Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital for approximately 150 h over four months to collect data on the SA transactions. The observations covered 318 transports from the time of the request until drop-off and recorded on the DSA observation sheet (Fig. 3).

The DSA observation sheet recorded which agents held and transacted the SA necessary for efficient transports and which sub-processes might have deficient SA distribution. The fields on the necessary SA and process name can be pre-filled based on the conceptual model. If SA (e.g., patient vitals, nurse information) is not applicable for a sub-process of the transport, SA ratings are omitted. Note that an “agent” may be an information system. In the sheet, delay or cancelation, related to SA or not (e.g., broken bed, emergency with other patients, complications in patient health), was further detailed with (1) what deficiency reasons (Table 1) could be associated with SA and (2) where in the transport process could the reason occur. The DSA observation sheet thus helps identify which SA transactions fail and the failure percentages with respect to particular reasons of delay or cancelation.

Data distribution fitting

RISK® modelling and analysis software application was used to identify statistical distribution for the quantitative data from TeleTracking and observations. The distribution fitting process began by generating histograms for visual comparison of candidate distributions and their parameters (mean, standard deviation, upper limit). Goodness-of-fit tests then evaluated the optimal distribution match, followed by visual verification comparing fitted distributions with the empirical histogram. Table 3 presents an example of the fitted distributions for completion time of the processes and sub-process for transport requests from the 8th floor in hospital. (Note that “create request” and “await assignment” time were based on TeleTracking data rather than records from the DSA observation sheet.)

TeleTracking data on the transport status were also fitted into distributions and Table 4 presents an example of all the fitted transport status of completed transports, delayed, and canceled for the simulation model of the 8th floor in the hospital.

The DSA observation sheet further identified SA-related transport deficiencies. Table 5 shows the proportion of the reasons for delays and cancelations attributable to deficient SA and the corresponding multinomial distribution.

Simulating current operations

The conceptual model (Fig. 2) was converted into a simulation by first building a DES of the major processes followed by ABM within several of these major processes.

Process modelling with discrete event simulation

The clinical transportation simulation started with arrival of the request from each origin and ended at patient/equipment drop-off. The processes and agents were modelled with five simulation objects, which are self-contained modelling constructs defined by distributions and parameters based on TeleTracking and observation data64:

-

1.

Arrival (source) is an object generating transport requests at specific arrival rates by the nurse placing requests (Np). Arrival rate was modelled separately for each origin.

-

2.

Process (server) is an object representing a process in the conceptual model with properties of completion time according fitted distributions from data, resources requirements, and other conditions for completing the process. There is a one simulation process object for every sub-process in the conceptual model.

-

3.

Complete (sink) is an object for terminating the transport request as defined by either cancelation or completion.

-

4.

Agent (entity) is an object defining a moveable resource unit in the modelled system (i.e., clinical transporter, patient, and transport request). Each entity in the population is tracked separately.

-

5.

Travel path (path) is an object representing a pathway between two sub-processes with a specified distribution of process time.

Using these five object types, six types of routes prescribing different sequence of sub-processes were simulated:

-

1.

One-way floor pick-up simulates the one-way patient pick-up from patient wards to another hospital units performing medical procedures.

-

2.

Round-trip floor pick-up simulates the round-trip patient pick-up from patient wards to CT-Scan or X-ray.

-

3.

Tests pick-up simulates the patient pick-up from hospital units performing medical procedures to a patient ward.

-

4.

Lobby pick-up simulates patient pick-up from the hospital lobby.

-

5.

Discharge simulates the patient pick-up from inpatient wards to discharge.

-

6.

Equipment pick-up simulates the equipment pick-up and transport from one location to another.

Figure 4 presents an example of simulating one-way patient pick-up from the 8th floor inpatient ward to a hospital unit performing medical procedures using Simio simulation software. Part 1 includes an arrival object to generate transport requests based on the arrival rate distribution. Part 2 involves assigning the transport request to an available clinical transporter in their shifts. Transporters would then check transport requirements and pick up equipment and perform hand-off with the nurse based on the fitted distributions in Table 3. The handoff may lead to cancelation or preparation of the patient for transport. Patient preparation may also lead to cancelation or continuing the transport that involves calling the virtual care unit to confirm pick up status. Process times for hands off, prepare patients, and call virtual care are based on the fitted distributions in Table 3. In Part 3, the transporter formally picks up the patient for transport and then drops off patient at destination with process time based on the fitted distributions in Table 3. Finally, Part 4 is an artificial simulation object (sink) to denote job completion.

Simplified processes modelling for one-way patient pick-up from ward. Model is divided into four parts for explaining the validation process in the next section. Part 1: Transport request generation (arrival). Part 2: Assignment to clinical transporter (CT), equipment pick-up, and nurse hand-off, with process times, prepare patient, and call VCC from Table 3. Part 3: Patient transport and drop-off. Part 4: Job completion (sink).

SA modelling with agent-based modelling

To model SA transactions and their operational impact, agent-based objects (e.g., transporters, nurses) were embedded with a state variable of SA and SA-dependent decision making for performing several sub-processes to complete a job request. In Simio, a state variable can be used to represent the utilized knowledge of the object according to some user-defined logic or statistical distribution for the clinical transportation at Carilion Clinic, the simulation model defined ten knowledge state variables (Table 6).

After defining the states, SA transactions were simulated with (Simio) “add-on steps” that define the logic for transacting SA from one agent to another agent for a change in the SA state variable. Table 7 outlines four generic add-on steps within an object to model SA transactions. These steps are built into a process object that requires a transporter to decide on how to continue with the transport.

Figure 5 shows the connection between the add-on steps in Simio. The state variables are first assigned numerical values with percentage to differentiate deficient from non-deficient transports for every origin based on multinomial distributions (e.g., Tables 4 and 5). Then, a decide step follows to direct agent either to a set node step for proceeding to the next sub-process; or to another decide step for directing the agent to encounter a delay step and then proceed to the next sub-process, or to a set node step for job cancelation. These add-on steps define how the agent objects proceed with sub-processes with and without delays and cancelations. For example, Fig. 6 shows the Simio add-on steps for simulating the “hand-off” process in one-way transports from the 8th floor to show portions of delays and cancelations due to deficient SA about equipment, nurse, and patient. Table 5 specifies that 55% and 5% of equipment-, 35% and 30% of nurse-, and 40% and 25% of patient-related delays and cancelations were due to deficient SA, respectively. Alhaider64 described the exact implementation in Simio.

A simplified construct of a built-in add-on steps to distribute SA for a process. Steps include: (1) Assign (set SA status, e.g., deficient or non-deficient), (2) Decide (evaluate SA adequacy), (3) Set Node (direct to proceed or delay/cancel), and (4) Delay (add time for deficient SA, per Table 5).

The add-on steps for modelling deficiency associated with handoff sub-process. Yellow steps indicate a delay, and green steps indicate a proceed to the next sub-process. Boxes one through seven represent distinct stages of the add-on process, included for clarity and are described in Alhaider64.

Full simulation model

Combing the DES and ABM in the Simio software, the full simulation model included six separate types of routes highlighted in different colors in Fig. 7. The model consisted of 28 patient origins, 29 equipment origins, 12 destinations, and more than 200 simulation objects.

The simulation model for the clinical transportation function in Simio. The simulation model shows the arrival of requests in the back, followed by the transporters picking up the transport requests. The simulation is divided into seven different process paths; each path follows different process times and processes sequence.

Simulating interventions

The full simulation model was modified (after verification and validation) to test two interventions derived from deficiencies highlighted in the DSA combined network model to enhance communication and coordination (i.e., SA transactions):

-

A.

Update charge nurse: Design procedure or behavioral rules for the transporters (CT) to update the charge nurse (Ncp) on the estimated time of arrival (ETA) and the patient being picked-up when the transporters accept the transport request. The DSA network model from Alhaider et al.25 showed a deficiency related to missing/poor SA on patient preparedness, condition, and needs. The Ncp needs to be aware of the incoming transport to ensure patients are ready and equipment needed is available before the transporter arrives, thereby minimizing cancelations and delays.

-

B.

Update X-ray unit: Design procedure or behavioral rules for the transporters to update the X-ray unit on ETA prior to arrival. Observations revealed that the transporters encounter delays upon arrival at the X-ray unit due to lack of awareness of the patient arrival time. The X-ray unit often does not have staff available to open the examination room for the patient and begin examination immediately upon the patient arrival.

Updating the charge nurse

The intervention of updating the charge nurse would require the transporter assigned to the request to call and inform the inpatient floor/ward nurse about ETA, name of patient to be picked up, and transport destination of the patient, thereby distributing these SA elements to the nurse for timely preparation of the patient for “hand-off”. To incorporate this intervention into the Simio model, a new simulation object representing the calling process (i.e., short phone call) with a minimum of 10 s and a maximum of 20 s was inserted before “hand-off” object (refer to blue box in Fig. 8). The time range was an estimation based on mock calls performed by the transporters during observations. This inpatient floor intervention process was simulated only for one-way transports from 6th floors to seven destinations. This inpatient floor (i.e., origin) was chosen because the number of transport requests exceeded one thousand.

To reflect the change in SA of the nurse as a result of the call by the transporter, new add-on steps were embedded in the “hand-off” process (i.e., the simulation object immediately after the calling process). Figure 9 shows two generic add-on steps for this intervention: assign (Contact Nurse) step and decide (Reached Nurse?) step. The assign step portioned transports into either good or deficient SA, so the following decide step would apply the logic that charge nurse with good SA would lead to transport proceeding without delay or/and cancelation but charge nurse with deficient SA would lead to transport proceeding with a delay or/and cancelation. As a phone call cannot guarantee perfect SA transmission, we simulated that the transport would lead to 50%, 75%, and 100% of transport without delay or cancelation after the phone for sensitivity analysis.

Figure 10 presents an extension to hand-off process in Fig. 6 by incorporating new add-on steps denoted in blue ovals. Alhaider64 described the exact implementation in Simio.

Add-on steps for intervention to update the ward nurse for nurse related deficiency. The blue boxes refer to where the intervention was implemented for SA-related delay and cancelation. Boxes one through five represent distinct stages of the add-on process, included for clarity and are described in Alhaider64.

Updating the X-ray unit

The intervention to update the X-ray unit would require the transporter assigned to the request to call the X-ray staff regarding ETA and name of patient, thereby distributing these SA elements to improve timely preparation of the X-ray room. To incorporate this intervention into the Simio model, a new simulation object representing the calling was added after “Pick-up patient”. The estimated duration for this intervention process (i.e., short phone call) followed a uniform distribution with a minimum of 20 s and a maximum of 25 s based on mock calls. This inpatient floor intervention process was simulated only for round-trip transports from fourteen floors to the X-ray unit. The intervention modelling in Simio followed the same method described for the intervention to update the charge nurse.

Results

Model verification and validation

The simulation model was verified with the three steps prescribed by Banks23 by visually inspecting the animation of the model, running the model to ensure the output parameters are reported, and ensuring outputs are consistent with expectation. After the verification, validation was performed with statistical comparisons between simulation outputs against the historical operational data concerning transport request/arrival and completion (Part 1 and 4 of the simulation model in Fig. 4, respectively). Table 8 presents the metrics on transport arrivals and completions for comparisons.

A series of one sample t-tests were performed to compare metrics between the simulation outputs and TeleTracking operational data (i.e., real-world historical output). To keep article length reasonable, Table 9 presents a subset validation results for the average transport time of one-way transport requests from the 6th floor to seven destinations. Refer to Alhaider64 for the full set of results that include all the metrics in Table 8. All t-test comparisons included simulation outputs from 100 replications between February 2020 – August 2021 (same as the historical dataset in TT). All results showed no significant difference in the number of transports generated from different departments, average completion time for transport jobs, and number of cancelations by origins at the alpha value of 0.0571. Given that the simulation included add-on steps mimicking SA transactions between agents, these results also indicate that DES and ABM can jointly model DSA. Further, the simulation model would be suitable to assess proposed interventions for eliminating deficiency associated with SA.

As an illustrative example of the model validation process, a Q–Q plot was generated for a representative transport route (from the 6th Floor to Fluoroscopy), as shown in Fig. 11. This sample comparison helps visualize how well the simulated data reproduce the overall distributional shape of actual transport times, including variability and tail behavior.

Intervention evaluation

A series of one sample t-tests compared metrics between the simulation outputs of 1500 replications and historical operational data for transport from the sixth floor to various test exam or treatment locations. The intervention was deemed effective if the t-tests could reveal significantly better average transport time and cancelation rate for all inpatient floor destinations at the alpha value of 0.05.

Updating the ward nurse

Table 10 presents the simulation outputs and t-test results on the intervention to update charge nurse for perfect transports from the sixth floor, showing statistically significant reduction in time per transport, cancelation, and total transport time on average across all destinations. However, some destinations experienced longer transport time when only 50% and 75% of the transport are free of delays and cancelations. When 50% of the transport proceeds without delays and cancelations, the overall reduction is only 0.34 (95% CI 0.32, 0.37) minute reduction per transport but 55 fewer cancelations during the period; for 75% of the transports without delays and cancelations, the reduction is 0.60 (95% CI 0.58, 0.63) minute per transport and 86 fewer cancelations; and for improvement on 100% of the transports without delays and cancelations, the reduction is 0.85 (95% CI 0.83, 0.89) minute per transport and 112 fewer cancelations. The cancelation numbers would translate to a reduction of 2% for 50%, 3% for 75%, and 4% for 100% of the transports without delays and cancelations. The accumulated difference in transport times from the 6th floor to all destinations were 213 min, 412 min, and 566 min for 50%, 75% and 100% of the transports without delays and cancelations, respectively.

Updating X-ray unit

Table 11 presents the summary statistics and t-test results regarding the intervention to update X-ray unit about ETA and patient information for all the origins. The results revealed a statistically significant increase in time per transport across all destinations. When the intervention improved SA only led to 50% of the transports without delays and cancelations, the increment was 0.42 (95% CI 0.38, 0.47) minute per transport; for 75% of the transports without delays and cancelations, the increment was 0.41 (95% CI 0.36, 0.46) minute; and for 100% of the transports without delays and cancelations, the increment was 0.40 (95% CI 0.36, 0.45) minute.

Discussion

This DSA research is the first to translate a qualitative DSA model into a simulation model with real-world operational data of intrahospital transportation, contributing to the literature in three distinct ways.

Modelling and simulation of DSA

The first contribution is the methodological advances for modelling DSA using DES and ABM with real-world operations data. This research is also interdisciplinary, applying operations research techniques for validating a human factors theory. Specifically, this article presents a methodology to develop a simulation model of the task (when), social (who), and knowledge (what) elements prescribed in the DSA theory for a real-world intrahospital transport operation, and the simulation results to provide validating evidence based on the non-significant t-test comparisons between the simulation outputs and the historical data. Prior quantitative DSA models in the literature lack details on SA distribution and transactions that correspond to real-world system performance. Stanton18 used SNA to quantify SA distribution and transactions between agents to provide quantitative characterizations of SA distributions across agents; however, the study did not correlate SNA metrics to any system performance indicators. Kitchin and Baber21 used ABM to investigate two types of agent interactions to distribute SA for a hypothetical monitoring task but lacked the representativeness of complex, real-world operations. The successful translation of the combined network in the Alhaider et al.25 study into a validated simulation model shows that our methodology of employing DES and ABM to model DSA complements existing qualitative model research.

The modelling approach in utilizing DES and ABM to jointly model processes/activities and SA distributed amongst agents is particularly unique for the healthcare domain. On one hand, the healthcare literature contains ample DES studies on patient flow management or other hospital processes72,73,74,75 but these simulation models neglect knowledge or SA of the workers that affect the effectiveness and efficiency of the processes. On the other hand, the DSA literature contains an ABM study on distributing SA for a hypothetical traffic monitoring task21 but lacks any investigation into the use of DES for modelling operations affected by SA distributed amongst agents. In summary, the methodology of employing DES and ABM to study DSA represents a novel and significant advancement to the literature, and the simulation results highlight the merits of evaluating DSA of a real-world system.

Assessment of DSA interventions to improve patient flow

The second contribution is the advance in assessing interventions for improving DSA. The simulation of intrahospital transportation was able to assess the two interventions of updating the charge nurse and the X-ray unit that were derived from the qualitative combined network model in Alhaider et al.25. The simulation results indicated that only the intervention to update the charge nurse would yield significant improvement in transport time and cancelation rate, whereas the intervention to update the X-ray unit would likely increase in the transport time. Even though the qualitative combined network model suggested two interventions that might have been equally effective, the simulation refuted the effectiveness for the intervention of updating the X-ray unit. These results illustrated the utility of quantitative methods in assessing DSA interventions based on findings from qualitative methods prior to implementation.

Examination into the underlying data distributions for the simulation suggests a likely explanation for the contrast in performance impact between the two interventions. The underlying operations data presents a major difference in base rates of the delays and cancelations that could be affected by SA between the two types of patient transport. On one hand, patient transports from the 6th floors to various test units in the model had 40% delay and 15% cancelation (Alhaider64 revealed similar findings for two other floors). On the other hand, the percentage of delays for round-trip to and from the X-ray unit is 6.44% and only 10% of those delays are associated with SA. Consequently, the additional work of updating the charge nurse versus the X-ray unit yielded different performance impacts. While the explanation is not entirely surprising, the simulation method proved invaluable for evaluating DSA interventions derived from qualitative DSA model.

Quantitative evidence supporting DSA modelling for patient flow management

The third contribution is the empirical evidence demonstrating the value of modeling DSA using quantitative methods for the real-world application of patient flow management. This study provided a foundation on how to simulate DSA embedded in intrahospital transportation and new protocols for improving SA and transport time. The simulation results affirm the practical recommendation to the level 1 trauma center on facilitating communication between the intrahospital transportation team and charge nurses regarding arrival of transport services for more reliable patient pick-ups. The charge nurse often places a transport request to be scheduled for several hours later, and the patients mostly do not get picked up on the exact time. The recommended intervention to update the charge nurse would support timely preparation even for their busy work nature. The evidence could compel other medical centers to adopt the DSA modelling methodology to assess and improve their patient flow management.

Cost-effectiveness of the DSA simulation model

Although developing a detailed simulation model requires initial investment of time and resources, the potential return for healthcare systems is substantial. By identifying inefficiencies and bottlenecks in intrahospital transport operations, the model supports data-informed decisions on staffing, scheduling, and workflow optimization, leading to improved patient throughput and more efficient use of personnel. In high-volume or capacity-constrained settings, these improvements can yield measurable cost savings and increased productivity. The model also enables strategic scenario testing, allowing evaluation of proposed interventions prior to implementation. In environments lacking robust transport tracking infrastructure, this approach provides a structured framework for future data collection and performance benchmarking. While benefits are more immediately realized in data-rich settings, the underlying logic and operational insights offer value for broader system improvement even in data-limited contexts.

Summary of research contributions and practical implications

The outcome of this study provided a quantitative DSA model that can assess SA distribution and transactions. A major contribution of this study is the integration of simulation and modelling techniques in the DSA methodology that can (1) translate the conceptual DSA network into a quantitative model, and (2) assess alternative communication protocols for SA distribution. Prior utilization of DSA framework in the literature does not assess performance as a function of DSA, despite the use of some quantitative methods to describe the systems level SA. This study, to our knowledge, is the first to quantitively test different interventions for eliminating system inefficiency based on DSA models. The assessment of SA distribution and transactions can help identify the best alternative of communication designs for improving SA and patient flow. For the level 1 trauma center, this specific study provides specific recommendations on communication design for the intrahospital transportation staff, potentially improving their SA transactions and thereby improving patient transport accuracy, waiting/delay time, and cancelation.

While prior simulation studies of intrahospital transportation have focused primarily on operational efficiency through scheduling or optimization frameworks, the present study builds on this foundation by introducing a cognitive-systems-based approach that explicitly models communication quality and distributed awareness as operational variables. This adds a new perspective to intrahospital transportation simulation by connecting delays to informational breakdowns, not just physical constraint, and supports a more comprehensive evaluation of coordination-sensitive hospital processes.

Proxy measures for DSA

The simulation model developed in this study uses downstream performance indicators, such as transport delays and cancellations, as proxies for evaluating improvements in DSA. Instead of measuring SA as a cognitive or internal state, the model focuses on whether critical information cues are transmitted to the appropriate agents in a timely manner. This transactional framing enables quantification of information flow efficacy as a pragmatic surrogate for system-level DSA. While the model does not capture real-time distribution of knowledge across agents due to limitations in the TeleTracking data, which primarily records operational outcomes, it offers a novel perspective for modeling DSA in complex healthcare systems. This approach represents an initial step toward operationalizing SA through observable system performance. Future work could enhance this framework by incorporating knowledge-tracking mechanisms or richer observational data to directly assess the distribution of SA.

Future work

The DSA modelling methodology presented in this article cannot capture any complex temporal and social dynamics in the system. That is, task, knowledge, and social elements evolve over time especially when these elements encounter abnormal events. For example, the social interactions and decision-making might go beyond the involvement of the nurses and transporters when patients face serious health conditions, which can change drastically in a short amount of time. Future research should include extended observations to understand unique system dynamics in these abnormal conditions and how agents adaptively distribute their SA for employing ABM or other techniques to model such dynamics. In addition, the quantitative and qualitative DSA modelling processes in this study were tedious, involving adaptation of many tools and software applications. A single DSA modelling tool that can capture the task, knowledge, and social elements of a system and then translate them easily into a DES and ABM simulation environment would help alleviate a lot of mechanical work for greater focus on intellectual endeavors and practical benefits.

Limitations

While the model and findings offer useful insights, several limitations should be acknowledged to clarify the scope, interpretability, and generalizability of the results.

Model scope and assumptions

The model was developed based on observed processes and transport transactions in a single healthcare facility. The selection of included services and flow pathways was based specifically on activities directly associated with internal patient transport that could be consistently defined in terms of time, quantity, and quality. As such, peripheral but related processes—such as initial or secondary triage, discharge gating, or room readiness—were excluded. These choices allowed us to focus on what the hospital defines as “transport” but may omit other process interactions that affect real-world delays. Additionally, the simulation used static staffing levels and assumed fixed transport protocols, without dynamic adjustment for real-time occupancy or variable shift patterns. While capacity constraints were respected at the level of transport approval (i.e., no transfer request is approved unless the receiving unit has space), the impact of downstream bottlenecks on emergent queuing or task reprioritization was not modeled explicitly.

Communication and SA representation

This study uses delays and cancellations as proxy indicators for DSA outcomes. Although this allows for quantifiable analysis of information transactions, the model does not track knowledge elements or agent-specific awareness states over time. Compensatory awareness, where one agent’s understanding may mitigate another’s gap, is not modeled. The framework assumes binary success or failure of communication events, limiting its representation of the nuanced, layered nature of real-world SA and coordination.

Data collection constraints

The model is built on retrospective data from a hospital’s TeleTracking™ system, which captures detailed process timestamps and deficiency reasons but lacks information on patient priority, clinical acuity, and agent-specific decision-making. Consequently, urgent versus routine transport requests could not be differentiated, and some workflow complexity may be underrepresented. Repeated or canceled transports are treated as distinct events, which may obscure inefficiencies rooted in systemic or procedural causes. Additionally, the absence of real-time observational data introduces potential classification bias in transport status or communication events.

Generalizability and adaptability

While the model is grounded in detailed, real-world data and supports meaningful what-if analysis, it is not directly generalizable to other facilities without adaptation. Variations in hospital staffing (e.g., nurse and transporter roles), transport systems (e.g., TeleTracking vs. other platforms), and department layouts may affect how the model performs. For example, the model reflects Carilion Clinic’s specific transport protocols and TeleTracking system, which may differ in other hospitals. Further, adaptation of the framework to other settings would require tailored data collection, stakeholder input, and adjustment to match specific hospital workflows.

Conclusion

This article advances DSA research by developing a methodology for translating qualitative DSA network models into quantitative models built on combining discrete event simulation and agent-based modelling. The method was applied to develop a DSA simulation model containing more than 200 simulation objects to reflect a real-world intrahospital transportation from 28 patient origins to 12 destinations in a level 1 trauma center. This DSA simulation model was validated by comparing simulation outputs against historical data for seven types of intrahospital transportation. Further, the simulation was used to evaluate two DSA interventions for improving patient flow, highlighting how quantitative methods are critical to assess findings and recommendations from qualitative research. The novel DSA modelling methodology applied to a real-world patient flow management system advances the understanding of system-level SA as it emerges from agent interactions. While the model evaluates SA-dependent performance rather than internal awareness states, its use of operational proxies (e.g., delays and cancelations) offers actionable insights for optimizing communication and healthcare workflows.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article and additional data can be obtain from https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/items/4c9df8bc-3d37-4cb7-b6ae-73b0b4658022.

References

Endsley, M. Situation awareness analysis and measurement, chapter theoretical underpinnings of situation awareness. Crit. Rev. 3–33 (2000).

Salmon, P., Stanton, N., Walker, G. & Green, D. Situation awareness measurement: A review of applicability for C4i environments. Appl. Ergon. 37, 225–238 (2006).

Stanton, N. A., Salmon, P. M., Walker, G. H. & Jenkins, D. P. Is situation awareness all in the mind?. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 11, 29–40 (2010).

Endsley, M. R. Situation awareness misconceptions and misunderstandings. J. Cogn. Eng. Decis. Mak. 9, 4–32 (2015).

Endsley, M. R. Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 37, 32–64 (1995).

Salas, E., Prince, C., Baker, D. P. & Shrestha, L. Situation awareness in team performance: Implications for measurement and training. Hum. Factors 37, 123–136 (1995).

Banbury, S. & Tremblay, S. A cognitive approach to situation awareness: Theory and application. (2004).

Lau, N. & Boring, R. Situation awareness in sociotechnical systems. in Human Factors in Practice (eds. Cuevas, H., Velázquez, J. & Dattel, A.) 55–70 (Routledge, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315587370-6.

Zhang, T. et al. Physiological measurements of situation awareness: A systematic review. Hum. Factors 65, 737–758 (2023).

Smith, K. & Hancock, P. A. Situation awareness is adaptive, externally directed consciousness. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 37, 137–148 (1995).

Artman, H. & Garbis, C. Situation awareness as distributed cognition. in Proceedings of ECCE vol. 98 6 (Citeseer, 1998).

Stanton, N. et al. Distributed situation awareness in dynamic systems: Theoretical development and application of an ergonomics methodology. Ergonomics 49, 1288–1311 (2006).

Salmon, P. M. et al. Representing situation awareness in collaborative systems: A case study in the energy distribution domain. Ergonomics 51, 367–384 (2008).

Stanton, N. A., Salmon, P. M., Walker, G. H., Salas, E. & Hancock, P. A. State-of-science: Situation awareness in individuals, teams and systems. Ergonomics 60, 449–466 (2017).

Ottino, J. M. Complex systems. AIChE J. 49, 292–299 (2003).

Macquet, A.-C. & Stanton, N. A. Do the coach and athlete have the same “picture” of the situation? Distributed situation awareness in an elite sport context. Appl. Ergon. 45, 724–733 (2014).

Griffin, T. G. C., Young, M. S. & Stanton, N. A. Investigating accident causation through information network modelling. Ergonomics 53, 198–210 (2010).

Stanton, N. A. Representing distributed cognition in complex systems: How a submarine returns to periscope depth. Ergonomics 57, 403–418 (2014).

Freeman, L. C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1, 215–239 (1978).

Tichy, N. M., Tushman, M. L. & Fombrun, C. Social network analysis for organizations. Acad. Manage. Rev. 4, 507–519 (1979).

Kitchin, J. & Baber, C. A comparison of shared and distributed situation awareness in teams through the use of agent-based modelling. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 17, 8–41 (2016).

de Bruin, T. & Rosemann, M. Understanding the main phases of developing a maturity assessment model. 11 (2005).

Banks, J. Handbook of Simulation: Principles, Methodology, Advances, Applications, and Practice (John Wiley & Sons, 1998).

Bonabeau, E. Agent-based modeling: Methods and techniques for simulating human systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 7280–7287 (2002).

Alhaider, A. A., Lau, N., Davenport, P. B. & Morris, M. K. Distributed situation awareness: A health-system approach to assessing and designing patient flow management. Ergonomics 63, 682–709 (2020).

TariVerdi, M., Miller-Hooks, E., Kirsch, T. & Levin, S. A resource-constrained, multi-unit hospital model for operational strategies evaluation under routine and surge demand scenarios. IISE Trans. Healthc. Syst. Eng. 9, 103–119 (2019).

Sobolev, B. G., Sanchez, V. & Vasilakis, C. Systematic review of the use of computer simulation modeling of patient flow in surgical care. J. Med. Syst. 35, 1–16 (2011).

Garcia-Vicuña, D., Esparza, L. & Mallor, F. Hospital preparedness during epidemics using simulation: The case of COVID-19. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 30, 213–249 (2022).

McGuire, F. Using simulation to reduce length of stay in emergency departments. in Proceedings of Winter Simulation Conference 861–867 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1109/WSC.1994.717446.

Samaha, S., Armel, & Starks, D. The use of simulation to reduce the length of stay in an emergency department. in Proceedings of the 2003 Winter Simulation Conference, 2003. vol. 2 1907–1911 (2003).

Gunal, M. M. & Pidd, M. Interconnected des models of emergency, outpatient, and inpatient departments of a hospital. in 2007 Winter Simulation Conference 1461–1466 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1109/WSC.2007.4419757.

Zeng, Z., Ma, X., Hu, Y., Li, J. & Bryant, D. A simulation study to improve quality of care in the emergency department of a community hospital. J. Emerg. Nurs. 38, 322–328 (2012).

Kádár, B., Pfeiffer, A. & Monostori, L. Discrete event simulation for supporting production planning and scheduling decisions in digital factories. Proc. 37th CIRP Int. Semin. Manuf. Syst. 444–448 (2004).

Rohleder, T. R., Lewkonia, P., Bischak, D. P., Duffy, P. & Hendijani, R. Using simulation modeling to improve patient flow at an outpatient orthopedic clinic. Health Care Manag. Sci. 14, 135–145 (2011).

Liu, P. & Wu, S. An agent-based simulation model to study accountable care organizations. Health Care Manag. Sci. 19, 89–101 (2016).

Baru, R. A. A decision support simulation model for bed management in healthcare. (Missouri University of Science and Technology, United States—Missouri, 2015).

Hamrock, E., Paige, K., Parks, J., Scheulen, J. & Levin, S. Discrete event simulation for healthcare organizations: A tool for decision making. J. Healthc. Manag. 58, 110 (2013).

Majid, M. A., Fakhreldin, M. & Zuhairi, K. Z. Comparing discrete event and agent based simulation in modelling human behaviour at airport check-in counter. in Human-Computer Interaction. Theory, Design, Development and Practice (ed. Kurosu, M.) 510–522 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39510-4_47.

He, L., Chalil Madathil, S., Oberoi, A., Servis, G. & Khasawneh, M. T. A systematic review of research design and modeling techniques in inpatient bed management. Comput. Ind. Eng. 127, 451–466 (2019).

Allen, M. et al. What is Discrete Event Simulation, and Why Use It? (NIHR Journals Library, 2015).

VanBerkel, P. T. & Blake, J. T. A comprehensive simulation for wait time reduction and capacity planning applied in general surgery. Health Care Manag. Sci. 10, 373–385 (2007).

Frank, A. B. Agent-Based Modeling in Intelligence Analysis. (George Mason University, United States—Virginia, 2012).

Law, A. M. Simulation Modeling and Analysis (McGraw-Hill Education, Dubuque, 2013).

Jacobson, S. H., Hall, S. N. & Swisher, J. R. Discrete-event simulation of health care systems. in Patient flow: Reducing delay in healthcare delivery 211–252 (Springer, 2006).

Vázquez-Serrano, J. I., Peimbert-García, R. E. & Cárdenas-Barrón, L. E. Discrete-event simulation modeling in healthcare: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 18, 12262 (2021).

Cayirli, T. & Veral, E. Outpatient scheduling in health care: A review of literature. Prod. Oper. Manag. 12, 519–549 (2009).

Green, L. Queueing analysis in healthcare. in Patient Flow: Reducing Delay in Healthcare Delivery 281–307 (Springer, 2006).

Standfield, L., Comans, T. & Scuffham, P. Markov modeling and discrete event simulation in health care: A systematic comparison. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 30, 165–172 (2014).

Zehrouni, A. et al. Hospital flood emergency management planning using Markov models and discrete-event simulation. Oper. Res. Health Care 30, 100310 (2021).

Bhattacharjee, P. & Ray, P. K. Patient flow modelling and performance analysis of healthcare delivery processes in hospitals: A review and reflections. Comput. Ind. Eng. 78, 299–312 (2014).

Cabrera, E., Taboada, M., Iglesias, M. L., Epelde, F. & Luque, E. Optimization of healthcare emergency departments by agent-based simulation. Procedia Comput. Sci. Complete 4, 1880–1889 (2011).

Rema, V. & Sikdar, K. Optimizing patient waiting time in the outpatient department of a multi-specialty Indian hospital: The role of technology adoption and queue-based monte Carlo simulation. SN Comput. Sci. 2, 1–9 (2021).

Paul, S. A., Reddy, M. C. & DeFlitch, C. J. A systematic review of simulation studies investigating emergency department overcrowding. SIMULATION 86, 559–571 (2010).

Yousefi, M. & Ferreira, R. P. M. An agent-based simulation combined with group decision-making technique for improving the performance of an emergency department. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 50, e5955 (2017).

Tracy, M., Cerdá, M. & Keyes, K. M. Agent-based modeling in public health: Current applications and future directions. Annu. Rev. Public Health 39, 77–94 (2018).

Lane, D., Monefeldt, C. & Rosenhead, J. Looking in the wrong place for healthcare improvements: A system dynamics study of an accident and emergency department. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 51, 518–531 (2000).

Grösser, S. Modeling the health insurance system of Germany: A system dynamics approach. Proc. 23rd Int. Conf. Syst. Dyn. Soc. (2005).

Ganiyu, R. A., Olabiyisi, S. O., Badmus, T. A. & Akingbade, O. Y. Development of a timed coloured petri nets model for health centre patient care flow processes. IJECS 4, 9 (2015).

Jørgensen, J. B., Lassen, K. B. & van der Aalst, W. M. P. From task descriptions via colored Petri nets towards an implementation of a new electronic patient record workflow system. Int. J. Softw. Tools Technol. Transf. 10, 15–28 (2008).

Meephu, E., Arwatchananukul, S. & Aunsri, N. Enhancement of Intra-hospital patient transfer in medical center hospital using discrete event system simulation. PLoS ONE 18, e0282592 (2023).

Ermling, C. The effect of transport scheduling strategies on the planning of patient transport.

Vinicius, T. et al. Real-time management of intra-hospital patient transport requests: An empirical study. Fac. Sci. Adm. Univ. Laval (2023).

Alhaider, A. A., Lau, N., Davenport, P. B., Morris, M. K. & Tuck, C. Distributed situation awareness in patient flow management: An admission case study. Proc. Human Fact. Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 62, 563–567 (2018).

Alhaider, A. A. Distributed Situation Awareness Framework to Assess and Design Complex Systems (Virginia Tech, 2023).

Alhaider, A. A., Lau, N., Davenport, P. B. & Morris, M. K. Command and control for managing patient flow. Proc. Int. Symp. Hum. Factors Ergon. Health Care 8, 273–274 (2019).

Alhaider, A. A., Lau, N., Davenport, P. B. & Morris, M. K. Quantitative evidence supporting distributed situation awareness model of patient flow management. Proc. Int. Symp. Hum. Factors Ergon. Health Care 9, 238–241 (2020).

Stanton, N. A., Baber, C. & Harris, D. Modelling Command and Control: Event Analysis of Systemic Teamwork (Ashgate, 2008).

Roberts, A. P. J. & Stanton, N. A. Macrocognition in submarine command and control: A comparison of three simulated operational scenarios. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 7, 92–105 (2018).