Abstract

Diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infections (ARIs) are the primary causes of morbidity and mortality in children under the age of five worldwide. However, there is a scarcity of up-to-date conclusive multi-country studies on the comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infection in under-five children in low- and middle-income countries. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the pooled magnitude and contributing factors of comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infection in low- and middle-income countries. A cross-sectional study design was employed with the most recent Demographic and Health Survey secondary data (DHS) from 2015 to 2024 in low- and middle-income countries. This secondary data was accessed from the DHS portal through an online request. The DHS is the global data collection initiative that provides detailed and high-quality data on population demographics, health, and nutrition in low- and middle-income countries. We used a weighted sample of 669,138 children aged 0–59 months. A multilevel mixed-effect binary logistic regression model was fitted to identify significant factors associated with comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI. The level of statistical significance was declared with a p-value < 0.05. This study found that 5.44% (95% CI: 5.38–5.49) of under-five children in low- and middle-income countries developed a comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infection. Maternal age, child age, wealth index, child sex, birth size, media exposure, vaccination status, health insurance, survey year, residence, country income level, and geographic region were significantly associated with the comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory infection. This study revealed that a sizable portion of under-five children developed a comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI in low- and middle-income countries. Both individual and community-level factors are significantly associated with the comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI. Therefore, the World Health Organization, with its partners, should inform respective countries executives and policymakers to focus on younger children, teenage mothers, media coverage, clean water provision, childhood vaccination, and extreme birth-weight babies. Moreover, low- and middle-income countries are encouraged to strengthen health insurance coverage, expand healthcare infrastructure, pursue sustainable economic growth, and foster intergovernmental collaboration to mitigate the comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infections (ARIs) are the primary causes of morbidity and mortality in children under the age of five worldwide1. Diarrheal disease is the third leading cause of death in this age group, with approximately 1.7 billion cases and around 443,832 deaths every year2. On the other hand, ARI is responsible for 42 million cases and results in 630,000 fatalities per annum in under five children3. These figures highlight the significant burden of co-occurrence of acute respiratory infections and diarrhea among under-five children and the need for comprehensive interventions to curb child mortality and morbidity.

The co-occurrence of many diseases is one of the leading causes of death for under-five children4. Comorbidity is defined as the concurrent occurrence of more than one disorder in the same person, either at the same time or in some causal sequence5. In low- and middle-income countries, diarrhea and ARI are the major causes of under-five mortality. The burden of concurrent diarrheal disease and ARI is substantial and merits further investigation. Beyond its association with childhood mortality, both diarrheal disease and ARI have been linked with many child health outcomes. In the first 2 years of a child, where the incidence of ARI and diarrheal disease is highest, it impedes the physical growth and development of the child, which may translate later into adult life6,7.

Prior research conducted in some countries revealed that socioeconomic, demographic, and environmental factors contribute to the co-occurrence of these diseases. Maternal and paternal educational level, age and sex of the child, family size, nutritional status of the child, access to safe water, improved sanitation facilities, access to media, and vaccination status of the child were commonly associated with comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI8,9,10,11,12,13,14. However, a multi-nation study that assesses the comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI is limited.

The comorbidity of diarrheal diseases and acute respiratory infections can significantly exacerbate health outcomes in children by elevating the risk of severe illness, extending recovery periods, increasing mortality rates, contributing to psychological stress, compromising immune function, and reducing access to appropriate treatment8,15. Beyond immediate mortality risk, comorbid diarrhea and ARI may contribute to long-term developmental impairments due to prolonged illness, nutritional deficits, and repeated immune challenges during critical growth periods16. Investigating such comorbidities offers valuable insights for clinicians and public health stakeholders into the interactions between multiple diseases and their cumulative burden on healthcare systems. Moreover, this approach supports the development of integrated interventions, which may be more effective than disease-specific strategies in addressing the complex health challenges faced by children.

Various interventions implemented globally to fulfill Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG-3), which focuses on reducing maternal and child mortality through enhancing access to improved sanitation and clean water, conducting widespread immunization campaigns, and promoting community-based education initiatives. Consequently, significant declines in cases of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infections have been observed in some regions. However, the prevalence of these conditions remains persistently high in certain countries17. Comorbidity of ARI & diarrhea may arise from distinct or interacting risk factors. Understanding comorbidity can reveal synergetic vulnerabilities/compound effects. Nonetheless, there is no conclusive and multi-continent study on the comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI among under-five children. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the pooled magnitude and contributing factors of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI among under-five children in 45 low- and middle-income countries. The findings from this study can inform policymakers about common risk factors for these conditions, thereby supporting the implementation of more effective strategies to improve child health outcomes in LMICs.

Methods

Data source

This study utilized data from 45 low- and middle-income countries that had the most recent Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted between 2015 and 2024. Countries were selected based on the availability of their latest DHS data during the data collection period, which took place from February 1 to 30, 2025. Because DHS data use standardized identifiers across countries, we were able to merge datasets from the 45 selected countries into a single, unified dataset. Weighting was applied to account for the complex sampling design of DHS data surveys. The sample weights correct the unequal probability selection of samples. Consequently, individual sample weights were calculated by dividing the DHS weighting variable (v005) by 1,000,000.

Sampling procedure

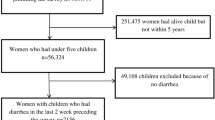

The DHS was a nationwide survey done in low- and middle-income nations with standardized, pretested, and validated questionnaires. The DHS surveys use a two-stage stratified cluster sampling technique. The first stage included randomly selecting all-encompassing clusters, or enumeration areas (EAs), from the sampling frame of the most recent publicly available national survey. Enumeration areas were the primary sampling unit of the survey cluster. In the second phase, systematic sampling was utilized to interview a subset of the target population’s houses, which included all of the households in each cluster. A weighted sample of 669,138 women-child pairs was included in the study. Missing values for the outcome variable were excluded from the study. The details of the DHS sampling procedure were found at https://dhsprogram.com.

Source and study population

The source populations were all under-five children residing in low- and middle-income countries. The study populations were all under-five children in the selected enumeration areas.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We only included countries that had the most recent DHS datasets from 2015 to 2024. We excluded countries lacking standard DHS data between 2015 and 2024.

Study variable

Outcome variable

The outcome variable for this study was the comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infection (ARI) among children under five years of age. This composite variable was derived by combining responses from the standardized DHS questionnaires concerning the presence of diarrhea and ARI. Children exhibiting both conditions were classified as having comorbidity and assigned a value of ‘1’; all other cases were coded as ‘0’. Diarrhea was determined based on maternal reports indicating whether the child had experienced diarrhea within the two weeks preceding the survey. Similarly, ARI prevalence was assessed through maternal responses indicating whether the child had suffered from a cough accompanied by rapid or short breathing during the same reference period18.

Independent variables

Both individual-level and community-level factors were reviewed from prior literature, and these include mother and partner education level, marital status, maternal age, child age, child sex, household head sex, number of under-five children, birth order, birth size, household wealth index, water source, vaccination status, source of cooking fuel, place of residence, country income level, geographic location of countries, survey year, and distance to health facility19,20. The details of each independent variable are available in supplementary Table 1.

Data management and model selection

After being extracted from the DHS portal, Stata version 17 was used to enter, code, clean, record, and analyze the data. DHS data are hierarchically structured from household to country level, by which children are nested within households, households are nested within communities, and communities are nested within countries. This clustering introduces within-cluster association that violates assumptions of independent observation by the ordinary logistic regression model. To account for this structure, a three-level multilevel multivariable logistic regression model was employed, comprising individual, community, and country-level factors. Random intercepts were included at each level to capture unobserved heterogeneity and adjust for the non-independence of observations within clusters. This approach provides more reliable estimates of associations between independent variables and the comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infection (ARI) among under-five children.

Model building and comparison

In the analysis, four models were fitted. The first model, known as the null model, contains only the outcome variables to test random variability and estimate the intra-cluster correlation coefficient (ICC). The second model included the individual-level variables. The third model contains only community-level variables. Finally, the fourth model combines both individual-level and community-level variables, combining the predictors from both the individual-level and community-level models to assess the combined influence of these variables on the outcome21. Due to the hierarchical nature of the model, models were compared based on deviance, Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC). A model with the lowest AIC, BIC, and deviance were selected as the best-fit model, which was model IV. In our multilevel logistic regression analysis, we addressed multicollinearity by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each predictor variable. The final model’s VIF has a mean value of 2.07. As a result, there was no multicollinearity issue in our analysis.

Both fixed-effect and random-effect analyses were done to see the effect of common predictors and variation across different hierarchies on the outcome.

Fixed effects, a measure of association that is utilized to estimate the association between the co-occurrence of diarrhea and ARI and each explanatory variable at both individual and community levels. The relationship between the dependent and independent variables was examined using multivariable analysis, with effect sizes presented as adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals. To account for the hierarchical structure of the data, the log-odds of comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infection were estimated using a three-level multilevel logistic regression model using the Stata syntax xtmelogit.

logit (πij) = log [πij/ (1 − πij)] = β0 + β1xij + β2xij …. +u0j + e0ij,

Where “πij” is the probability of comorbidity of diarrhea & ARI; (1-πij) is the probability of no comorbidity; βo is the log odds of the intercept; β1 and βn are the effect sizes of individual and community-level factors; and x1ij… xnij are independent variables of individuals and communities. The quantities uoj and eij are random errors at cluster levels and individual levels, respectively.

Random effects (a measure of variation)

Variation of the outcome variable or random effects was assessed using the proportional change in variance (PCV), intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), and median odds ratio (MOR)22,23.

The ICC shows the variation in the comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI due to community characteristics, which was calculated as ICC = σ2/(σ2 + π2/3), where σ2 is the variance of the cluster24. The higher the ICC, the more relevant the community characteristics are for understanding individual variation in comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI.

MOR is the median value of the odds ratio between the areas with the highest comorbidity and the area with the lowest comorbidity when randomly picking out under-five children from two clusters, which was calculated as MOR = 0.95√σ², where σ² is the variance of the cluster. In this study, MOR shows the extent to which the individual probability of comorbidity is determined by the residential area25.

Furthermore, the PCV illustrates how different factors account for variations in the prevalence of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI, which is computed as PCV = (Vnull - Vc)/Vnull, where Vc is the cluster-level variance and Vnull is the variance of the null model26.

Result

Socio-demographic, child, and environment-related factors of comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory infection in low- and middle-income countries

Our analysis included a total of 669,138 weighted under-five children. More than half (51.51%) of under-five children were males. More than half (58.96%) of children under five were below the average weight. One-fourth (25.21%) of mothers had no formal education. More than three-fourths (75.95%) of mothers were aged 30–34 years. More than half (56.75%) of children were aged 24–59 months. More than two-thirds (70.29%) of the households had media exposure. More than three-fourths (76.82%) of children were vaccinated. More than half (60.17%) of households had improved toilet facilities. More than two-thirds (69.71%) of households had no improved water source. More than one-third (41.47%) of households had basic access to a water source, and nearly one-third (31.04%) of households had a clean fuel source. One-third (33.57%) of households had difficulty in accessing health facilities. One-fourth of (26.59%) households had health insurance coverage. According to the World Bank, one-third (66.36%) of the 45 countries are classified as lower-middle-income economies. Among 45 low- and middle-income countries, more than half (55.29%) were sub-Saharan African countries. Comorbidity (3.49% vs. 1.95%), diarrhea (7.63% vs. 4.95%), and ARI (13.47% vs. 8.76%) were decreasing from 2015 to 2019 to 2020–2024, respectively. Table 1.

Prevalence of comorbidity of diarrhea and respiratory tract infection in low-and-middle income countries

According to this study finding, 5.44% (95% CI: 5.38–5.49), 12.57% (95% CI: 12.49–12.65), and 22.25% (95% CI: 22.15–22.35) of under-five children in low-and-middle-income countries had comorbidity, diarrhea, and acute respiratory tract infection. Afghanistan exhibited the highest prevalence of comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infection (47.46%) as well as sole diarrhea (25.81%), while Armenia reported the lowest prevalence for both conditions, at 1.41% and 3.81%, respectively. Similarly, Burundi reported the highest prevalence of acute respiratory tract infection at 41.74%, whereas Tajikistan recorded the lowest rate at 6.53%. Table 2.

Random effect analysis and model comparison

In the first model (null model), the ICC indicates that 18.16% of the total variability for comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI in under-five children was due to differences between clusters in enumeration areas, with the remaining 81.84% attributable to individual differences. In addition, the median odds ratio also revealed that comorbidity was heterogeneous among clusters. According to the final model, if children were chosen at random from two clusters in the enumeration areas, children in the higher cluster would have a 1.43 times higher chance of being comorbid for diarrhea and ARI as compared to children within lower clusters. Regarding PCV, about 80.82% of the variability in comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI was explained by the final model (model IV). Model IV was selected as the best-fitting model because it had the lowest deviance (30,051.41). Table 3.

Factors associated with comorbidity of diarrhea and lower respiratory tract infection

A multilevel, multivariable logistic regression analysis was done to identify factors significantly associated with comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI in 45 low- and middle-income countries. Accordingly, maternal age, child age, wealth index, child sex, birth size, media exposure, water source, vaccination status, health insurance, survey year, residence, country income level, and regional location of countries were significantly associated with comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI.

Children born to mothers aged less than 20 years had a 21% higher chance (AOR = 1.21, 95% CI (1.06–1.39)) of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI as compared to children born to mothers aged 20–34 years. Similarly, children from mothers aged above 35 years had a 23% lower chance (AOR = 0.77, 95% CI (0.70–0.84)) of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI. Children from the poor wealth quintile household had a 38% higher chance of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI (AOR = 1.38, 95% CI (1.25–1.53)) as compared to children from rich wealth quintile households. Male children had a 12% higher chance of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI (AOR = 1.12, 95% CI (1.05–1.20)) as compared to female children. Large- and small-birth-size-born children had a 38% (AOR = 1.38, 95% CI (1.27–1.49)) and 30% (AOR = 1.30, 95% CI (1.20–1.40)) higher chance of developing comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI, respectively, as compared to normal-weight-born children. Children from households with no media exposure had a 23% (AOR = 1.23, 95% CI (1.14–1.33)) lower chance of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI as compared to children from media-exposed households. Children who had no access to improved water sources had a 9% (AOR = 1.09, 95% CI (1.02–1.17)) higher chance of developing comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI as compared to children who had improved water access. Children aged less than 12 months and 12–23 months had a 25% (AOR = 1.25, 95% CI (1.14–1.36)) and 61% higher chance (AOR = 1.61, 95% CI (1.49–1.73)) of developing comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI as compared to children aged 24–59 months old. Children from households without health insurance coverage had a 60% (AOR = 1.60, 95% CI (1.42–1.80)) higher chance of developing a comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI as compared to children from health insurance-covered households. Children from low- and lower-middle-income countries had 2.24 times (AOR = 2.24, 95% CI 1.81–2.76) and 1.97 times (AOR = 1.97, 95% CI 1.61–2.40) higher chance of developing comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI, respectively, as compared to children from upper-middle-income countries. Children residing in South and Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa had 1.60 times (AOR = 1.60, 95% CI (1.49–1.72)), 1.63 times (AOR = 1.63, 95% CI (1.49–1.81)), and 1.35 times (AOR = 1.35, 95% CI (1.29–1.41)) higher chance of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI, respectively, as compared to children residing in Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Countries that conducted DHS surveys from 2015 to 2019 had a 32% higher chance (AOR = 1.32, 95% CI 1.22–1.42) of developing comorbidity as compared to countries that conducted them from 2020 to 2024. Table 4.

Discussion

This study was done in 45 low- and middle-income countries that had the most recent DHS data from 2015 to 2024, aiming to assess the pooled prevalence of comorbidity in diarrhea and ARI. Accordingly, the study revealed that the pooled prevalence of comorbidity, diarrhea, and ARI in low- and middle-income countries was 5.44%, 12.57%, and 22.25%, respectively. The co-occurrence of diarrhea and ARI poses amplified public health challenges, increasing morbidity rates and complicating treatment efficacy. This comorbidity also heightens clinical risks, such as dehydration, impaired respiratory function, and an increased likelihood of mortality due to compromised immune responses. This study highlights the need for integrated healthcare strategies. As a result, public health programmers could prioritize inter-sectorial and multi-country interventions like improved hygienic practices and quality air. Furthermore, resource allocation should be prioritized by policymakers toward regions exhibiting the highest burden of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI.

According to the multi-level, multi-variable analysis, male children had a higher chance of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI. This finding is supported by other studies done across the globe27,28,29,30. A plausible explanation could be the mother’s preference for revealing a compliant of male child31. As a result, they are able to notice changes in the health status of male children early and report to the healthcare provider accordingly. In addition, boys had a higher chance of exploratory behavior32, such as taking risks like playing in unsanitary environments, which increased their exposure to pathogens causing diarrhea and ARI.

Our finding confirmed that comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI is more common in children less than 2 years. This is in line with many prior studies33,34. This is due to the fact that younger children’s immunity is less developed, making them at increasing risk of infection35. In addition, children in this age depend on mothers; as a result, any unhygienic feeding exposes children to infection.

We found a significant association between the wealth status of the household and the comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI. This is in line with the study done in Bangladesh and Nepal36,37. The possible justification could be poor households have unmet nutritional needs and adopt inappropriate feeding practices that exacerbate the risk of infection37. In addition, poorer households had limited access to health care services due to out-of-pocket money that led them to delayed and inadequate care during their illness.

This study found that children born to mothers aged over 35 years exhibited a lower likelihood of developing comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infection, while those born to mothers younger than 20 years were at a higher chance of comorbidity, relative to the reference group of mothers aged 20–34 years. These findings are consistent with evidence reported in previous studies8,9,38. This might be due to older mothers having better experience in accessing healthcare, more stable socio-economic conditions, and greater awareness of child health needs; as a result, the child will have a lower risk for diarrhea and ARI. On the other hand, teenage mothers might have limited skill and knowledge in child care, poor access to health care due to financial constraints, and low-level education, which contributes to the comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI.

This study found a significant association between household access to mass media and lower odds of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI. This is supported by other studies39,40. This is due to the fact that mass media, especially radio and television broadcasts, help to spread awareness and reach distant places40. Through these channels, health information can be disseminated in the local language, and that larger population and community will acquire health information. Having access to this kind of information will enable parents of under-five children to seek the right medical attention, which will ultimately encourage health-seeking habits.

According to this study finding, children who have not received a vaccination had a higher chance of being exposed to comorbidity than children who have received a vaccination. This is congruent with other studies41,42. This is due to the fact that vaccination helps children develop immunity against infection, such as the pneumococcal vaccine, which lowers the risk of respiratory infection, and the rotavirus infection, which protects children from diarrheal disease. Therefore, strengthening vaccination programs is crucial to lessen diarrhea and ARI.

According to this study finding, children from households without health insurance had a higher chance of comorbidity as compared to children from non-insured households. This is congruent with other studies43,44. This is due to the fact that children from uninsured households had many barriers, including delayed care, timely medical management, unmet medical needs, and higher out-of-pocket costs. On the other hand, insured children often had better access to preventative care, timely medical management, and health education. As a result, the governments in the respective countries should take all responsibilities to strengthen health insurance coverage for the people.

Children residing in rural areas demonstrated a higher chance of experiencing comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infection compared to their urban counterparts. This is in line with other studies45. This discrepancy could be due to contextual factors between urban and rural areas. For instance, in rural areas, there is a lack of access to clean water and sanitary facilities, and the use of solid fuel might be increased46. In addition, rural communities lack sufficient health facilities with lesser quality that result in incomplete infectious disease control.

Both small-weight- and large-weight-born children had higher chance of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI as compared to children born with average weight. This is supported by a study in Brazil and Mozambique47,48. This is due to the fact that low-birth-weight children have lower immunity levels and underdeveloped organs, predisposing them to infection49. Conversely, a high birth weight may be associated with increased risk of delivery complications and potential metabolic disorders.

Countries that reported the DHS survey between 2020 and 2024 exhibited lower chance of comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infection among children compared to those that reported DHS data between 2015 and 2020. This observation is consistent with findings from previous research50. This might be due to improved public health intervention in many countries through WASH (Water, sanitation and hygiene) program, expanded vaccination program and integrated management of childhood illness46,51.

Children who had clean cooking source had lower chance of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI as compared to children with solid cooking source. Children living in households that use clean cooking fuels (such as electricity, LPG, or biogas) had significantly lower levels of indoor air pollution compared to those using solid fuels (like wood, charcoal, or dung). Solid fuel combustion releases harmful pollutants such as particulate matter (PM₂.₅), carbon monoxide, and volatile organic compounds, which impair respiratory health and increase susceptibility to infections52,53. Moreover, indoor air pollution weakens mucosal immunity, making children more vulnerable to both acute respiratory infections (ARI) and diarrheal diseases, especially in poorly ventilated homes. Clean cooking reduces this exposure, thereby lowering the odds of comorbidity.

Children residing in South and Southeast Asia, Central Asia, Oceania, and sub-Saharan Africa had higher odds of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI as compared to children residing in Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean54. This could be due to higher burden regions like Asia and Africa, limited access to health care, poor sanitation, inadequate nutrition, and higher prevalence of infectious disease. In contrast, Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean have a better health infrastructure, a higher standard of living, and more effective public health interventions, which reduce the risk of such morbidity.

As compared to children residing in upper middle-income countries, children residing in lower and lower middle-income countries had a higher odd of comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI. This is supported by other studies. This might be due to limited access to health care, poor sanitation, and malnutrition that leads to high exposure to infectious disease.

Strength and limitation

The strength of this study stemmed from its focus on several nations with varying geographic and economic backgrounds that may help programmers and policymakers to create effective multi-country initiatives. The cross-sectional study design made it impossible for the study’s findings to establish a causal link between the independent variables and the outcome. In addition, due to the DHS nature of the data, important proximal predictors like recent infection in the household, immune status of the child, and crowding may result in under/overestimation of the comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI. Therefore, we recommend future researchers conduct studies by incorporating proximal factors associated with ARI and diarrhea.

Conclusion

This study revealed that a sizable number of under-five children developed a comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI in low- and middle-income countries. Maternal age, child age, wealth index, child sex, birth size, media exposure, water source, vaccination status, health insurance, survey year, country income level, and regional location of countries were significantly associated with comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI. Therefore, the World Health Organization, with its partners, should inform respective countries executives and policymakers to focus on younger children, teenage mothers, media coverage, clean water provision, childhood vaccination, and extreme birth-weight babies. In addition, LMIC countries should work on health insurance coverage, building health facilities, standing to bring economic improvement in the long term, and working in collaboration with each other to reduce comorbidity of diarrhea and ARI.

Data availability

The most recent data from the Demographic and Health Survey were used in this study, and it is publically available online at (http://www.dhsprogram.com). The datasets used and/ or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARI:

-

Acute respiratory infection

- EA:

-

Enumeration area

- ICC:

-

Inter cluster correlation coefficient

- LR:

-

Logistic regression

- LMIC:

-

Lower and middle income countries

- MOR:

-

Median odds ratio

- SDG:

-

Sustainable development goal

- SSA:

-

Sub-Sahara Africa

- PCV:

-

Proportional change in variance

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Unicef. Levels and trends in child mortality report 2017. (2017).

WHO & Diarrheaol disease. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease (2024).

Sharrow, D. et al. Global, regional, and National trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2019 with scenario-based projections until 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Inter-agency group for child mortality Estimation. Lancet Global Health. 10 (2), e195–e206 (2022).

Apanga, P. A. & Kumbeni, M. T. Factors associated with diarrhoea and acute respiratory infection in children under-5 years old in ghana: an analysis of a National cross-sectional survey. BMC Pediatr. 21, 1–8 (2021).

Valderas, J. M., Starfield, B., Sibbald, B., Salisbury, C. & Roland, M. Defining comorbidity: implications for Understanding health and health services. Annals Family Med. 7 (4), 357–363 (2009).

WHO U. Ending Preventable Child Deaths from Pneumonia and Diarrhoea by 2025: the Integrated Global Action Plan for Pneumonia and Diarrhoea (GAPPD) (WHO, 2013).

Dewey, K. G. & Mayers, D. R. Early child growth: how do nutrition and infection interact? Maternal & child nutrition. 7, 129 – 42. (2011).

Mulatya, D. M. & Mutuku, F. W. Assessing comorbidity of diarrhea and acute respiratory infections in children under 5 years: evidence from kenya’s demographic health survey 2014. J. Prim. Care Community Health. 11, 2150132720925190 (2020).

Adedokun, S. T. Correlates of childhood morbidity in nigeria: evidence from ordinal analysis of cross-sectional data. Plos One. 15 (5), e0233259 (2020).

Manunâ, M. F. & Nkulu-wa-Ngoie, C. Factors associated with childs comorbid diarrhea and pneumonia in rural Democratic Republic of the congo. Afr. J. Med. Health Sci. 19 (5), 55–62 (2020).

Walker, C. L. F., Perin, J., Katz, J., Tielsch, J. M. & Black, R. E. Diarrhea as a risk factor for acute lower respiratory tract infections among young children in low income settings. J. Global Health. 3 (1), 010402 (2013).

Ullah, M. B. et al. Factors associated with diarrhea and acute respiratory infection in children under two years of age in rural Bangladesh. BMC Pediatr. 19, 1–11 (2019).

Li, R. et al. Diarrhea in under five year-old children in nepal: a Spatiotemporal analysis based on demographic and health survey data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17 (6), 2140 (2020).

Kandala, N-B., Emina, J. B., Nzita, P. D. K. & Cappuccio, F. P. Diarrhoea, acute respiratory infection, and fever among children in the Democratic Republic of congo. Soc. Sci. Med. 68 (9), 1728–1736 (2009).

Walker, C. L. F. et al. Does comorbidity increase the risk of mortality among children under 3 years of age? BMJ Open. 3 (8), e003457 (2013).

Mokomane, M., Kasvosve, I., Melo Ed, Pernica, J. M. & Goldfarb, D. M. The global problem of childhood diarrhoeal diseases: emerging strategies in prevention and management. Therapeutic Adv. Infect. Disease. 5 (1), 29–43 (2018).

WHO & Disability. https://www.who.int/health-topics/disability#tab=tab_1 (2025).

Kenya, D. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Ministry of Health, the National AIDS Control Council, the National Council for Population and Development, Kenya. (2014).

Ghebremeskel, G. G., Kahsay, M. T., Gulbet, M. E. & Mehretab, A. G. Determinants of maternal length of stay following childbirth in a rural health facility in Eritrea. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 23 (1), 613 (2023).

Campbell, O. M., Cegolon, L., Macleod, D. & Benova, L. Length of stay after childbirth in 92 countries and associated factors in 30 low-and middle-income countries: compilation of reported data and a cross-sectional analysis from nationally representative surveys. PLoS Med. 13 (3), e1001972 (2016).

Sommet, N. & Morselli, D. Keep calm and learn multilevel logistic modeling: A simplified three-step procedure using stata, R, mplus, and SPSS. Int. Rev. Social Psychol. 30, 203–218 (2017).

Penny, W. Holmes AJSpmTaofbi. Random Eff. Anal. 156, 165 (2007).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., Rothstein & HRJRsm A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random‐effects models for meta‐analysis. 1 (2), 97–111. (2010).

Rodriguez, G. & Elo, I. J. T. S. J. Intra-class correlation in random-effects models for binary data. 3 (1), 32–46. (2003).

Merlo, J. et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. 60 (4), 290–297. (2006).

Tesema, G. A., Mekonnen, T. H. & Teshale, A. B. J. P. Individual and community-level determinants, and spatial distribution of institutional delivery in ethiopia, 2016: Spatial and multilevel analysis. 15 (11), e0242242. (2020).

Sultana, M. et al. Prevalence, determinants and health care-seeking behavior of childhood acute respiratory tract infections in Bangladesh. PloS One. 14 (1), e0210433 (2019).

Anteneh, Z. A., Andargie, K. & Tarekegn, M. Prevalence and determinants of acute diarrhea among children younger than five years old in Jabithennan district. Northwest. Ethiopia 2014 BMC Public. Health. 17, 1–8 (2017).

Siziya, S., Muula, A. S. & Rudatsikira, E. Correlates of diarrhoea among children below the age of 5 years in Sudan. Afr. Health Sci. 13 (2), 376–383 (2013).

Hasan, R. et al. Incidence and etiology of acute lower respiratory tract infections in hospitalized children younger than 5 years in rural Thailand. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 33 (2), e45–e52 (2014).

Vlassoff, C. Gender differences in determinants and consequences of health and illness. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 25 (1), 47 (2007).

Sandseter, E. B. H. Early childhood education and care practitioners’ perceptions of children’s risky play; examining the influence of personality and gender. Early Child. Dev. Care. 184 (3), 434–449 (2014).

Mengistie, B., Berhane, Y. & Worku, A. Prevalence of diarrhea and associated risk factors among children under-five years of age in Eastern ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Open. J. Prev. Med. 3 (07), 446 (2013).

Sarker, A. R. et al. Prevalence and health care–seeking behavior for childhood diarrheal disease in Bangladesh. Global Pediatr. Health. 3, 2333794X16680901 (2016).

Kundu, S. et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with childhood diarrhoeal disease and acute respiratory infection in bangladesh: an analysis of a nationwide cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 12 (4), e051744 (2022).

Kamal, M. M., Hasan, M. M. & Davey, R. Determinants of childhood morbidity in bangladesh: evidence from the demographic and health survey 2011. BMJ Open. 5 (10), e007538 (2015).

Budhathoki, S. S., Bhattachan, M., Yadav, A. K., Upadhyaya, P. & Pokharel, P. K. Eco-social and behavioural determinants of diarrhoea in under-five children of nepal: a framework analysis of the existing literature. Trop. Med. Health. 44, 1–7 (2016).

Rahman, A. & Hossain, M. M. Prevalence and determinants of fever, ARI and diarrhea among children aged 6–59 months in Bangladesh. BMC Pediatr. 22 (1), 117 (2022).

Alam, Z., Higuchi, M., Sarker, M. A. B. & Hamajima, N. Mass media exposure and childhood diarrhea: a secondary analysis of the 2011 Bangladesh demographic and health survey. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 81 (1), 31 (2019).

Lakew, G. et al. Diarrhea and its associated factors among children aged under five years in madagascar, 2024: a multilevel logistic regression analysis. BMC Public. Health. 24 (1), 2910 (2024).

Owusu, D. N., Duah, H. O., Dwomoh, D. & Alhassan, Y. Prevalence and determinants of diarrhoea and acute respiratory infections among children aged under five years in West africa: evidence from demographic and health surveys. Int. Health. 16 (1), 97–106 (2024).

Fathmawati, F., Rauf, S. & Indraswari, B. W. Factors related with the incidence of acute respiratory infections in toddlers in sleman, yogyakarta, indonesia: evidence from the Sleman health and demographic surveillance system. PloS One. 16 (9), e0257881 (2021).

Aziz, N., Liu, T., Yang, S. & Zukiewicz-Sobczak, W. Causal relationship between health insurance and overall health status of children: insights from Pakistan. Front. Public. Health. 10, 934007 (2022).

Purnama, T. B., Wagatsuma, K. & Saito, R. Prevalence and risk factors of acute respiratory infection and diarrhea among children under 5 years old in low-middle wealth household, Indonesia. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 14 (01), 95–104 (2025).

Abuzerr, S. et al. Prevalence of diarrheal illness and healthcare-seeking behavior by age-group and sex among the population of Gaza strip: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health. 19, 1–10 (2019).

Merid, M. W. et al. Impact of access to improved water and sanitation on diarrhea reduction among rural under-five children in low and middle-income countries: a propensity score matched analysis. Trop. Med. Health. 51 (1), 36 (2023).

Lira, P. I., Ashworth, A. & Morris, S. S. Low birth weight and morbidity from diarrhea and respiratory infection in Northeast Brazil. J. Pediatr. 128 (4), 497–504 (1996).

Bauhofer, A. F. L. et al. Examining comorbidities in children with diarrhea across four provinces of mozambique: A cross-sectional study (2015 to 2019). Plos One. 18 (9), e0292093 (2023).

West, J. et al. Is small size at birth associated with early childhood morbidity in white British and Pakistani origin UK children aged 0–3? Findings from the born in Bradford cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 18, 1–10 (2018).

Troeger, C. et al. Estimates of global, regional, and National morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoeal diseases: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 17 (9), 909–948 (2017).

Kyu, H. H. et al. Global, regional, and National age-sex-specific burden of diarrhoeal diseases, their risk factors, and aetiologies, 1990–2021, for 204 countries and territories: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 25 (5), 519–536 (2025).

Islam, M. A. et al. Association of household fuel with acute respiratory infection (ARI) under-five years children in Bangladesh. Front. Public. Health. 10, 985445 (2022).

Geremew, A., Gebremedhin, S., Mulugeta, Y. & Yadeta, T. A. Place of food cooking is associated with acute respiratory infection among under-five children in ethiopia: multilevel analysis of 2005–2016 Ethiopian demographic health survey data. Trop. Med. Health. 48, 1–13 (2020).

Boutayeb, A. The impact of infectious diseases on the development of Africa. Handb. Dis. Burdens Qual. Life Meas. 1171. (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to the DHS program for granting us the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Berhan Tekeba; Chilot Kassa MekonnenData curation: Hailemicakel Kinde Abate; Alebache Ferede ZegeyeFormal analysis: Berhan Tekeba; Tewodros Getaneh AlemuInvestigation: Mulugeta Wassie; Deresse Abebe GebrehanaMethodology: Alebachew Ferede Zegeye; Tewodros Getaneh AlemuSoftware: Enyew Getaneh Mekonnen; Hailemicakel Kinde AbateSupervision: Alebachew Ferede Zegeye; Deresse Abebe GebrehanaValidation: Enyew Getaneh Mekonnen; Chilot Kassa MekonnenWriting original draft: Berhan Tekeba; Mulugeta WassieWriting review and editing: Berhan Tekeba and Tewodros Getaneh Alemu.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study is a secondary analysis of DHS data; thus, it does not require ethical approval. The data used in this study aggregated secondary data that is publicly available and does not contain any personal identifying information that can be related to study participants. The data was kept confidential in an anonymous manner. No patient was involved in developing the research question, outcome measure, or design of the study. The public was also not involved in the design, conduct, or choice of our outcome measures and recruitments for the study. The public and patients were not involved in the dissemination of the research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tekeba, B., Gebrehana, D.A., Mekonnen, E.G. et al. The comorbidities of diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infection and risk factors among under-five children in 45 low- and middle-income countries. Sci Rep 15, 30139 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15705-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15705-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Gut Prevotella stercorea associates with protection against infection in rural African children

Nature Communications (2025)