Abstract

The timely and precise identification of diseases in plants is essential for efficient disease control and safeguarding of crops. Manual identification of diseases requires expert knowledge in the field, and finding people with domain knowledge is challenging. To overcome the challenge, computer vision-based machine learning techniques have been proposed by the researchers in recent years. Most of these solutions with the standard convolutional neural network (CNN) approaches use uniform background laboratory setup leaf images to identify the diseases. However, only a few works considered real-field images in their work. Therefore, there is a need for a robust CNN architecture that can identify the diseases in plants in both laboratory and real-field conditioned images. In this paper, we have proposed an Inception-Enhanced Vision Transformer (IEViT) architecture to identify diseases in plants. The proposed IEViT architecture extracts local as well as global features, which improves feature learning. The use of multiple filters with different kernel sizes efficiently uses computing resources to extract relevant features without the need for deeper networks. The robustness of the proposed architecture is established by hyper-parameter tuning and comparison with state-of-the-art. In the experiment, we consider five datasets with both laboratory-conditioned and real-field conditioned images. From the experimental results, we see that the proposed model outperforms state-of-the-art deep learning models with fewer parameters. The proposed model achieves an accuracy rate of 99.23% for the apple leaf dataset, 99.70% for the rice dataset, 97.02% for the ibean dataset, 76.51% for the cassava leaf dataset, and 99.41% for the plantvillage dataset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global demand for food production is met with some challenges in the form of plant disease, which makes a significant threat to production of crops1. Plant diseases are fueled by changing climatic conditions such as temperature. Hence, accurately and timely identifying these diseases is crucial to prevent their spread2. Traditional identification relies on visual inspection, which is labor-intensive, lacks precision, and is prone to human error3. Researchers have proposed several machine learning (ML)-based approaches to identify diseases in plants from the leaf images and broadly classify them into traditional ML-based approaches and deep learning (DL)-based approaches. The traditional ML-based approach includes algorithms such as K-nearest neighbour (KNN), support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), and decision tree (DT)4. The performance accuracy in this algorithm heavily depends on the extracted features from the images. Finding the set of features from the extracted features that gives optimum results is an important challenge in this approach.

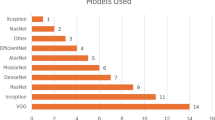

CNNs have shown remarkable success in image analysis tasks, making them well-suited for the identification of visual symptoms associated with plant diseases. Their ability to automatically learn hierarchical features from images contributes to highly accurate disease classification. Several deep learning architectures such as, VGG165, VGG195, InceptionV36, ResNet507, MobileNet8, and EfficientNet9 are used in the identification of diseases. Despite their strengths, DL architectures fail to model global relationships effectively; deeper architectures widen receptive fields but risk losing low-level features in the process10. In recent times, deep learning with self-attention has been used in this field and gives prominent results. Despite the development of architecture and achieving high accuracy, it is still far from being implemented in real field conditions due to various reasons: (a) The number of parameters used in the state-of-the-art deep learning models is large and requires high computing devices to train the model. (b) Real-field images for the agricultural crops are unavailable. Designing a lightweight convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture that can effectively identify diseases in plants is an important area in research. In this view, Dosovitskiy et al.11 introduced the vision transformer (ViT) architecture in image processing and computer vision tasks. This architecture has achieved significant performance in classification with less memory and fewer parameters. Singh et al.12 used MobileViT architecture in the identification of plant leaf diseases with fewer parameter as compared to standard CNN models. However, a limited number of labelled images may often leads to class imbalance, which affects in models performances. A low-cost real time plant disease detection model named as PMVT, used by Li et al.13. They have replaced the convolution block with \(7\times 7\) convolution and also integrated CBAM in standard ViT. In comparison with CNN, the ViT architecture heavily relies on model regularization and data augmentation while training on smaller datasets. The main reason is that the ViT architecture mainly focuses on extracting global features and long-distance features, whereas the CNN architecture focuses on local features. However, the combination of the CNN with the ViT architecture will enhance the feature extraction as the model will extract both local as well as global features. Further, hybridization of both CNN and ViT may increase the performance of the model. In this point of view, a novel lightweight Inception-Enhanced Vision Transformer (IEViT) architecture is proposed to identify the diseases in plants. The model combines features extracted from both Inception CNN and ViT architecture. This model begins with two inception blocks, where we use a parallel convolution filter to extract local features, followed by a stacked transformer block.

Contribution and organization of the paper

The main contributions of the proposed architecture are as follows

-

An Inception-Enhanced Vision Transformer (IEViT) architecture is proposed to identify the diseases in plants with wide and different conditioned images.

-

To extract the local features, two inception blocks with parallel convolution are used, which use different filter sizes to extract the features.

-

The model is lightweight and uses only 0.90M parameters, which is much less as compared to state-of-the-art deep learning models and can be feasible to implement in agriculture. The proposed model is implemented in different datasets, and the performances are compared with different state-of-the-art deep learning models. The proposed model outperforms several deep learning-based architectures.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. “Related work” provides a brief discussion of several existing works. Section “Materials and methods” provides the details about the proposed models. Results and performance are discussed in Sect. “Experimental results and analysis”. Finally, the paper concludes in Sect. “Conclusion” with future scope.

Related work

The performance of CNN in computer vision is impressive, and researchers have explored and designed several deep-learning models to identify diseases in plants. In this section, we have explored and summarized different deep-learning models used in plant disease detection. Mohanty et al.14 used two different deep learning architectures, AlexNet and GoogleNet, to identify the diseases in plants. In this paper, the authors used a large-scale plant dataset consisting of 54306 images of 38 different categories. Three different types of images were used, namely color, greyscale, and segmented images and recorded a maximum accuracy of 99.35%. Later, Ferentinos et al.15 used five different deep learning architectures to classify 58 distinct plant diseases and achieved an accuracy of 99.48% using VGG architecture.

Thakur et al.16 proposed a lightweight VGG-ICNN model for the identification of plant diseases in multiple plant disease datasets. In this paper, the authors used 4 convolution layers of VGG16 and three blocks of Inception v7. In their paper, the authors recorded an average accuracy rate of 99.16%. Later, a lightweight DenseNet (LWDN) proposed in17 to identify the diseases in plants achieved an accuracy rate of 99.36% in the plantvillage dataset14.

Too et al.18 suggested a fine-tuned deep learning architecture to identify different diseases in plants. Using DenseNet architecture18, they have recorded maximum accuracy. Further, Atila et al.19 used EfficientNet architecture to identify the diseases in plants, and they have compared the performances of the model with several state-of-art deep learning models and showed that EfficientNet architectures outperform other models. Moreover, Sangeetha et al.20 proposed an improved agro deep learning in the identification of panama wilts diseases in banana leaves. This technique used the arrangement of colour and shape changes in banana leaves to forecast the disease’s intensity and its effects and achieved an accuracy rate of 91.56%.

CNN, with self-attention, has also gained much attention and is widely used in the identification of plant diseases. Zeng et al.21 proposed a self-attention-based CNN (SACNN) model to identify different crop diseases. The SACNN model consists of the base network to extract global features and self-attention to extract the local features. In their work, different levels of noise were added in the images to evaluate the model performance and show SACNN outperform state-of-art deep learning models. Chen et al.22 proposed a lightweight attention-based deep learning architecture to identify the diseases in rice plants. The authors used the MobileNet-V2 pre-trained on ImageNet as the backbone network, and to improve the learning capability for minute lesion information, they incorporated an attention mechanism. The attention mechanism helps the network understand the significance of spatial points and inter-channel relationships for input features.

Moreover, Qian et al.23 proposed a deep CNN architecture to identify 4 different maize diseases. In this work, the authors divided the CNN architecture into three stages. Stage 1 extracts the image features and encodes them into a feature tokens matrix. Stage 2 is the core computation using multi-head self-attention, and finally, stage 3 is the classification stage. Deep attention dense CNN used by Pandey et al.24 to identify different plant diseases. Mixed sigmoid attention learning merging with basic dense learning used in this work as in dense learning features at higher layer considering all lower layer features that provide efficient training process. Further, attention learning strengthens the learning ability of the dense block. The authors achieved an accuracy rate of 97.55% on a real-time dataset consisting of 17 plant species. Later, Bhujel et al.25 proposed a lightweight self-attention CNN to identify different tomato leaf diseases. The model is proposed based on residual architecture and used 20 convolution layers, and after the 16th layer, they used an attention block.

Mohamed Zarboubi et al.26 proposed a CustomBottleneck-VGGNet to identify the different tomato leaf diseases. In this proposed approach author has used two layers of VGG16 followed by custom bottle neck layer with \(1\times 1\) and \(3\times 3\) convolutions . They have also included CBR (Convolution-Batch Norm-ReLU) and CBS (Convolution-BatchNorm-SiLU) layer. Author recorded an accuracy rate of 99.12% with 1.4M parameters.

Moreover, Ghost enlightened transformer (GET) architecture suggested by Lu et al.27 to identify grape diseases and pests. The performances of GeT suppress other deep learning models, achieve an accuracy rate of 98.14%, and are also faster and lighter. To enhance the feature extraction in ViT architecture, Yu et al.28 used inception convolution in ViT architecture to identify the diseases in plants. Four different datasets were used in this work, and the experimental results outperformed those of other deep learning models. Furthermore, A combination of CNN and ViT was used in the work29 to identify different diseases in plants. Three different datasets were used to evaluate the performances and show that fusion of attention with CNN blocks compensates the speed of the architecture. Mobile device compatible, PMVT a light weight transformer based architecture used in13 to identify the diseases in plant. In this paper, the author replaces the convolution block in MobileViT with an inverted residual structure and also incorporates CBAM into the ViT encoder. Multiple datasets were used to evaluate the performances of the model, and it achieved 1.6% higher performance than MobileNetV3 and 2.3% in Squeezenet.

Bellout et al.30 investigate 5 different YOLO model namely YOLOv5, YOLOX, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, and YOLO-NAS in identification of tomato leaf diseases. PlantDoc and PlantVillage dataset were used to investigate the result and achieved an accuracy of 93.1% using YOLOv5 model. A light weight IoT integrated DL based approach termed as LT-YOLOv10n, proposed by Abdelaaziz Bellout et al.31 to identify real-time tomato leaf disease detection. Author has incorporated CBAM and C3F layer in YOLOv10 architecture and developed a mobile-based application for the identification of diseases. The images from the public roboflow universe dataset, along with images from the PlantVillage dataset, were used to train the model and achieved an accuracy rate of 98.7%. Table 1 summarizes the articles discussed in the related section.

Materials and methods

In this paper, we aim to design a lightweight deep learning architecture to identify diseases in plants and that can also be easily deployable in agriculture. In particular, we design a fusion of Inception block and ViT transformer architecture termed as IEViT to classify the diseases in plants.

Inception block

Inception block in architecture first used in GoogleNet architecture by Szegedy et al.6. Increasing the layers in the DL architecture may result in overfitting in the model. In inception, it uses multiple filters of different sizes on the same layer. The outputs of all the convolution layers are concatenated together and forwarded to the next layer. The use of multiple filter sizes extracts better features, which increases the performance of the model. In this paper, we have used two inception blocks termed as InceptionA and InceptionB block. The normal convolution used in the inception block was replaced with depthwise separable convolution. The use of depthwise separable convolution reduces the number of parameters in the model. The parameter used in depthwise separable convolution is calculated as

We write the computation cost in standard convolution as

where \(D_F\) is the input image dimension, \(D_K\) is the kernel dimension, M is the number of channels and N is the number of kernel/filters. The inceptionA block consists of \(1\times 1\) convolution, \(1\times 1\) convolution followed by one \(3\times 3\) depthwise separable convolution, \(1\times 1\) convolution followed by two \(3\times 3\) depthwise separable convolution and \(3\times 3\) maxpooling followed by \(1\times 1\) convolution as shown in figure. Similarly, in inceptionB block also we have used \(3\times 3\) average pooling and \(7\times 7\) depthwise separable convolution as shown in Fig. 1.

Inverted bottleneck block (MV2)

The inverted residual structure was first used in MobileNet architecture39 and adopted in IEViT architecture, which undergoes feature enhancement and feature reduction in convolution. The block diagram of MV2 is shown in Fig. 2, and it is seen that MV2 uses three separate convolutions. At first, \(1\times 1\) point-wise convolution is used to expand low-dimension to high-dimensional feature maps. Next, \(3\times 3\) depth-wise separable convolution is used, followed by an activation function to achieve spatial filtering of the higher-dimensional data. Finally, \(1\times 1\) point-wise convolution is used to project back to the low-dimensional subspace. The initial and final feature map is added using a residual connection.

We denote X as the input tensor to the inverted bottleneck block, \(C_\text {in}\) represents the number of input channels, and \(C_{out}\) represents the number of output channels. The first step involves expanding the number of channels by using a \(1\times 1\) convolution followed by a non-linear activation function. Let t denote the expansion factor. The output of this layer is expressed as

Later, depthwise separable convolution is applied of kernel size \(K\times K\) is applied with a depth multiplier \(\alpha\) on each input channel. The output of this depthwise convolution layer is expressed as

Following the depthwise convolution, a \(1\times 1\) pointwise convolution is applied to combine information across channels to reduce the output channel to \(C_{out}\). The output is expressed as

Finally, a residual connection is added between the input and output of the block. The output is expressed as

Vision transformer block

With the success of transformer architecture in the natural language field, Dosovitskiy et al.11 used transformer architecture in image recognition task and showed that it achieves the same performance accuracy as CNN. The ViT transformer architecture consists of a multi-head attention (MHA)40 layer and a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) as shown in Fig. 3. Instead of dividing the image into a number of patches followed by a linear projection of patches, we pass the input image through the convolutional layer to extract the local features. The local features are divided into a number of patches, and the patches are forwarded to the transformer block. In transformer architecture, MHA and MLP are the main components, which are preceded by one normalization layer and followed by residual connection.

The self-attention mechanism calculates attention scores that represent the importance of each patch in the image. These attention scores are used to compute a weighted sum of the values (representations) of all patches, producing an attention output. Let’s denote the input to the self-attention mechanism as X, where X has dimensions \(N\times d\), with N being the number of tokens in the sequence and d being the dimensionality of the token embeddings. The self-attention mechanism computes attention scores as follows:

-

Query, key, and value matrices: Three matrices \(W^Q,W^K\) and \(W^V\), are learned parameters mapping the input X to query, key, and value spaces, respectively. These matrices have dimensions \(d\times d\).

-

Query, key, and value projections: Compute query \(Q=X.W^Q\), key \(K=X.W^K\) and value \(V=X.W^V\)

-

Scaled Dot-Product Attention: Compute the scaled dot-product attention scores

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Attention}(Q,K) = \texttt {softmax}\left( \frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d}}\right) \end{aligned}$$(7) -

Attention Output: Compute the attention output \(A = \text {Attention}(Q,K).V\)

The attention output A has dimensions \(N\times d\), representing the weighted sum of values.

The ViT architecture consists of a feed forward neural network as MLP separated by a nonlinear activation function. The activation function used is Swish. The output is represented as

where W is the learnable weight matrices and b is the bias.

Inception enhanced vision transformer architecture

The main objective of this work is to hybridize the Inception block with ViT architecture to identify the diseases in the plants. The inception block used in the architecture extracts the local features, and the ViT architecture extracts the global feature information. The inception-enhanced ViT architecture consists of a Convolution block, an InceptionA block, followed by an InceptionB block, an Inverted bottleneck Block (MV2), Vision Transformer block (ViT), and Global Average Pooling.

The architecture of Inception-enhanced ViT is shown in Fig. 4. The first layer is the input layer, which takes the RGB images of size \(256\times 256\times 3\) as input. The next layer used is a convolutional layer with filter size \(3\times 3\). The output generated in this layer is of size \(128\times 128\times 16\). The output of the convolution layer is forwarded to the InceptionA block, followed by the InceptionB block for multilevel feature extraction. InceptionA uses filter size of \(1\times 1\),\(3\times 3\) depthwise convolution, and \(3\times 3\) max-pooling layer as shown in Fig. 1. The InceptionB block consist of \(1\times 1\),\(7\times 7\) depthwise convolution, and \(3\times 3\) avg-pooling layer as shown in Fig. 1. The output generated after the InceptionB block is of size \(128\times 128\times 192\). The output of each layer is concatenated together and forwarded as the input of the next layer. Next, a number of MV2 blocks is used, which enhances the feature reduction as well as reduces the number of computations. The output features of the MV2 block are then divided into a number of patches of size \(n\times n\) (n = 2, 4, 8) and passed through the transformer block for global feature extraction. Non-overlapping patch embedding technique is used in this work, where the input feature map is divided into a number of patches determined by the patch size. The output of the transformer block is then passed through a convolution layer and a global average pooling layer, which converts the output of the convolution layer into a 1D vector. Finally, a dense layer is used with a softmax activation function and output neuron, which is equal to the number of classes in the dataset. A brief description of the parameter used along with the output size of each layer is shown in Table 2. For an instance of 5 classes, the required parameter is 904,693, which varies with regard to the number of output classes in the dataset. The size of the required parameter is 3.72MB. The activation function used in the convolution block is ReLu, and in MV2 and transformer block is Swish.

Experimental results and analysis

Dataset

Five open-source publicly available dataset is used to evaluate the performance of the proposed model. The dataset used are Apple leaf image dataset41, rice disease dataset34, ibean dataset36, PlantVillage dataset14, and Cassava dataset42. The images in the dataset are of different categories, such as laboratory-conditioned images, field images, images with multiple leaves and images with complex backgrounds. The images used in this work is resized into \(224\times 224\). The purpose of using multiple dataset is to evaluate the robustness of the proposed model.

Apple leaf image dataset41 is the first dataset that is used in this work, which is a freely available dataset and consists of 1820 images. Table 3 gives a brief dataset description along with number of classes. Figure 5 shows the sample images from the dataset.

Sample images from Apple Leaf Dataset41.

The second dataset used is the rice leaf diseases dataset34, which consists of 5932 images of four categories of rice diseases. The images in this dataset were captured in a real field. Figure 6 shows the sample images of the dataset, and Table 3 shows the description of the dataset.

Sample images from Rice Leaf dataset34.

The third dataset used is ibean dataset36, which consists of three classes of images. The images in this dataset were captured in real-time field conditioned, and multiple leaves were present in single images. Table 4 and Fig. 7 show the dataset description and sample images from the dataset.

Sample images from ibean dataset36.

The fourth dataset used is the cassava dataset42, which consists of one healthy and four disease-class images. The images in the dataset were captured with complex backgrounds. Figure 8 shows the sample images, and Table 4 shows the detailed dataset description.

Sample images from Cassava dataset42.

The images in the fifth dataset are from the plantvillage dataset14. PlantVillage dataset consists of 54305 images and 38 different categories of diseases. In this work, we have considered only 7 categories of potato and corn images. Figure 9 contains the sample images, and Table 5 summarizes the detailed dataset information.

Sample images from PlantVillage dataset14.

Evaluation matrics

Performance evaluation matrices determine how effectively the proposed model classifies the images. In this paper, we have used several performance matrices such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, False Positive Rate (FPR), False Negative Rate (FNR), f1-score, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC). The proportion of accurately predicted images to all images is called accuracy.

Precision is defined as the proportion of true predictions to the total number of positive predictions of the model.

Sensitivity is defined as the proportion of positive classes classified as positive to the total number of positive classes.

FPR is the ratio of false predictions with negative values.

FNR is the ratio of false negative values with positive values.

F1-score is defined as the harmonic mean of precision and recall.

where TP is true positive, which is defined as the correctly predicted positive along with the original class as positive. FP indicates false positive, which is defined as images supposed to be positive but predicted negatively. TN is true negative, indicating images are negative and predicted as negative. FN is false negative, indicating images are negative but predicted as positive.

Results and discussion

In this section, we evaluate the performance of the proposed architecture to identify diseases in plants without specifying the disease class. We consider the following five different publicly available plant disease datasets: apple leaf dataset41, rice leaf dataset34, ibean dataset36, cassava dataset42 and plantvillage dataset14. We set the learning rate of the proposed model as 0.001, the batch size as 32, and the training epoch as 100. Firstly, the performance of the model is evaluated in terms of accuracy and loss. Table 6 presents the training and validation accuracy, training and validation loss on five datasets with 100 epochs. Figures 10, 11, 12, 13 and, 14 shows the progression of accuracy and loss on each dataset using the Adam optimizer after 100 epochs. From the figures, we observe that the accuracy increases and the loss decreases with respect to epochs. From the accuracy and loss curve, we find that after a certain number of epochs, the accuracy and loss stabilize, thereby achieving optimum results.

Performance on Apple Leaf dataset41.

Performance on Rice dataset34.

Performance on Ibean leaf dataset36.

Performance on Cassava dataset42.

Performance on PlantVillage dataset14.

We have also investigated the model performance with other key performance matrices such as sensitivity, specificity, precision, FPR, FNR, f1-score, and mathews correlation coefficient (MCC). Table 7 summarizes the matrices on each dataset. Moreover, the performance of the proposed model on test images is shown in terms of the confusion matrix.

The confusion matrices of apple41, rice34, ibean 36, cassava42 and plantvillage datasets14 are drawn and shown in Figs. 15, 16 and 17. From the confusion matrix, it is observed that the proposed model has very few false positives and false negatives in all the datasets.

Confusion matrix of cassava dataset42.

Performance comparison with different optimizers

We evaluate and compare the performance of the proposed Inception-ViT architecture with several optimizers to find which optimizer provides the best performance. We select the following optimizers: SGD43, Adam44, RMSProp43, Adamax43, Adadelta43, and Ftrl45. From Table 9, we observe that Adam and RMSProp optimizer provide the highest performance accuracy. Moreover, we can conclude that the Adam optimizer outperforms others for all the datasets14,34,36,41,42.

Performance with the number of patches

Moreover, to show the effectiveness of patch sizes in the proposed Inception with ViT architecture for the identification of plant diseases, we provide a comparative analysis with different patch sizes. We consider the following patch sizes: \(2\times 2\), \(4\times 4\), \(8\times 8\), and \(16\times 16\). From Table 10, we can see that the patch size has less impact on the performance. However, using patch size \(8\times 8\) and \(4\times 4\) provides a superior performance as compared to patch size \(2\times 2\) and \(16\times 16\), respectively.

Comparison with state-of-art deep learning models

In order to verify the robustness of the proposed model, we have compared the performance of the proposed model with several state-of-the-art deep learning architectures. The performance comparison of the proposed model with different deep learning models has been summarized in Table 8 after 100 epochs. From Table 8, it is observed that the proposed Inception-enhanced Vision Transformer model outperforms the state-of-the-art deep learning architectures. Table 8 also compares the parameters required of the deep learning models, and it shows that the proposed deep learning model uses fewer parameters. Table 8 shows the size and Floating Point Operations per Second (FLOPs) required in each model, and it shows that the proposed model require fewer FLOPs as compared to standard DL models. The performance of the proposed model is also compared with the other deep learning models in Table 11. From Table 11, it is noted that the proposed model can successfully classify diseases in plants with higher performance accuracy as compared to the existing works. Hence, it is worthwhile to note that the proposed Inception-enhanced Vision Transformer outperforms state-of-the-art deep learning models.

Conclusion

In this paper, we propose an inception-enhanced Vision Transformer architecture to identify diseases in plant leaves. The fusion of inception in ViT architecture has the benefit of having both local and global feature extraction, which increases the performance of the model. In fact, the ViT blocks in the proposed model accelerate the training, and the attention model in ViT focuses on the meaningful regions in the input image. An investigation is performed with different patch sizes to achieve the optimal architecture. The results reveal that Inception-enhanced ViT with 4 patch size gives the best performance accuracy. The proposed inception-enhanced ViT architecture is experimented on five different datasets, which are unbalanced datasets, images in the dataset with complex backgrounds, and images with multiple leaves. The experimental result shows that the model performance achieves impressive results with an accuracy rate of 99.23%, 99.70%, 97.02%, 76.51%, and 99.41% on apple41, rice34, ibean36, cassava42, and plantvillage datasets14, respectively. The performance in the cassava dataset42 is lower than that of the other dataset. This is because the dataset is unbalanced and the presence of multiple leaves in a single image. Moreover, the images in the dataset are highly correlated with each other. In51, the authors recorded an accuracy rate of 52.87% and 46.24% using plain and deep residual convolutional neural networks in an imbalanced cassava dataset42. In comparison with this, our proposed model achieved a much higher performance accuracy rate in the imbalanced dataset. The number of parameters required in the proposed model is much less and can be easily deployable in small devices like smartphones. Furthermore, the likelihood of human error and disease transmission is decreased by quick and automatic identification. Moreover, the presence of agro experts in remote areas is very few; the proposed inception-enhanced Vision Transformer model provides significant benefits to the farmers to reduce crop yield loss and identify the diseases in plants in an easy manner. The future direction of this work can be extended to a real-time AI model by integrating IoT-enabled smart cameras for continuous, automated disease detection in farms. Additionally, federated learning can be employed, allowing the model to train across distributed farm data without sharing raw images.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in Kaggle repository at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/piantic/plantpathology-apple-datasethttps://www.kaggle.com/datasets/therealoise/bean-disease-datasethttps://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sinadunk23/behzad-safari-jalalhttps://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mohitsingh1804/plantvillage, https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/nirmalsankalana/cassava-leaf-disease-classification.

References

Islam, M. M. et al. Deepcrop: Deep learning-based crop disease prediction with web application. J. Agric. Food Res. 14, 100764 (2023).

Ullah, N. et al. An effective approach for plant leaf diseases classification based on a novel deepplantnet deep learning model. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1212747 (2023).

Pacal, I. et al. A systematic review of deep learning techniques for plant diseases. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57(11), 304 (2024).

Kamilaris, A. & Prenafeta-Boldú, F. X. Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Comput. Electron. Agric. 147, 70–90 (2018).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. Preprint at arXiv:1409.1556 (2014).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 2818–2826 (2016).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 770–778 (2016).

Howard, A.G., Zhu, M., Chen, B., Kalenichenko, D., Wang, W., Weyand, T., Andreetto, M. & Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.04861 (2017)

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. in International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 6105–6114 (2019). PMLR

Bayram, B., Kunduracioglu, I., Ince, S. & Pacal, I. A systematic review of deep learning in mri-based cerebral vascular occlusion-based brain diseases. Neuroscience 568, 76–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2025.01.020 (2025).

Dosovitskiy, A., Beyer, L., Kolesnikov, A., Weissenborn, D., Zhai, X., Unterthiner, T., Dehghani, M., Minderer, M., Heigold, G., Gelly, S., et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. Preprint at arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Singh, A. K., Rao, A., Chattopadhyay, P., Maurya, R. & Singh, L. Effective plant disease diagnosis using vision transformer trained with leafy-generative adversarial network-generated images. Expert Syst. Appl. 254, 124387 (2024).

Li, G., Wang, Y., Zhao, Q., Yuan, P. & Chang, B. Pmvt: A lightweight vision transformer for plant disease identification on mobile devices. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1256773 (2023).

Mohanty, S. P., Hughes, D. P. & Salathé, M. Using deep learning for image-based plant disease detection. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1419 (2016).

Ferentinos, K. P. Deep learning models for plant disease detection and diagnosis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 145, 311–318 (2018).

Thakur, P. S., Sheorey, T. & Ojha, A. VGG-ICNN: A lightweight CNN model for crop disease identification. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82(1), 497–520 (2023).

Dheeraj, A. & Chand, S. Lwdn: Lightweight densenet model for plant disease diagnosis. J. Plant Dis. Prot., 1–17 (2024).

Too, E. C., Yujian, L., Njuki, S. & Yingchun, L. A comparative study of fine-tuning deep learning models for plant disease identification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 161, 272–279 (2019).

Atila, Ü., Uçar, M., Akyol, K. & Uçar, E. Plant leaf disease classification using efficientnet deep learning model. Eco. Inform. 61, 101182 (2021).

Sangeetha, R., Logeshwaran, J., Rocher, J. & Lloret, J. An improved agro deep learning model for detection of panama wilts disease in banana leaves. AgriEngineering 5(2), 660–679 (2023).

Zeng, W. & Li, M. Crop leaf disease recognition based on self-attention convolutional neural network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 172, 105341 (2020).

Chen, J., Zhang, D., Zeb, A. & Nanehkaran, Y. A. Identification of rice plant diseases using lightweight attention networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 169, 114514 (2021).

Qian, X., Zhang, C., Chen, L. & Li, K. Deep learning-based identification of maize leaf diseases is improved by an attention mechanism: Self-attention. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 864486 (2022).

Pandey, A. & Jain, K. A robust deep attention dense convolutional neural network for plant leaf disease identification and classification from smart phone captured real world images. Eco. Inform. 70, 101725 (2022).

Bhujel, A., Kim, N.-E., Arulmozhi, E., Basak, J. K. & Kim, H.-T. A lightweight attention-based convolutional neural networks for tomato leaf disease classification. Agriculture 12(2), 228 (2022).

Zarboubi, M., Bellout, A., Chabaa, S. & Dliou, A. Custombottleneck-vggnet: Advanced tomato leaf disease identification for sustainable agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 232, 110066 (2025).

Lu, X. et al. A hybrid model of ghost-convolution enlightened transformer for effective diagnosis of grape leaf disease and pest. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 34(5), 1755–1767 (2022).

Yu, S., Xie, L. & Huang, Q. Inception convolutional vision transformers for plant disease identification. Internet of Things 21, 100650 (2023).

Borhani, Y., Khoramdel, J. & Najafi, E. A deep learning based approach for automated plant disease classification using vision transformer. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 11554 (2022).

Bellout, A., Zarboubi, M., Dliou, A., Latif, R. & Saddik, A. Advanced yolo models for real-time detection of tomato leaf diseases. Math. Model. Comput. 11(4), 1198–1210 (2024).

Bellout, A. et al. Lt-yolov10n: A lightweight iot-integrated deep learning model for real-time tomato leaf disease detection and management. Internet of Things 33, 101663 (2025).

Geetharamani, G. & Pandian, A. Identification of plant leaf diseases using a nine-layer deep convolutional neural network. Comput. Electr. Eng. 76, 323–338 (2019).

Chen, J., Chen, J., Zhang, D., Sun, Y. & Nanehkaran, Y. A. Using deep transfer learning for image-based plant disease identification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 173, 105393 (2020).

Sethy, P. K., Barpanda, N. K., Rath, A. K. & Behera, S. K. Deep feature based rice leaf disease identification using support vector machine. Comput. Electron. Agric. 175, 105527 (2020).

Lee, S. H., Chan, C. S., Mayo, S. J. & Remagnino, P. How deep learning extracts and learns leaf features for plant classification. Pattern Recogn. 71, 1–13 (2017).

Bean Disease dataset https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/therealoise/bean-disease-dataset. Last accessed: 03-01-2024

Wheat Rust Dataset https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sinadunk23/behzad-safari-jalal. Last accessed: 07-01-2024

Singh, D., Jain, N., Jain, P., Kayal, P., Kumawat, S. & Batra, N. Plantdoc: A dataset for visual plant disease detection. In: Proceedings of the 7th ACM IKDD CoDS and 25th COMAD, pp. 249–253 (2020)

Sandler, M., Howard, A., Zhu, M., Zhmoginov, A. & Chen, L.-C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 4510–4520 (2018).

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A.N., Kaiser, Ł. & Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems30 (2017)

Plant Pathology Dataset and Apple Leaf data https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/piantic/plantpathology-apple-dataset. Accessed 03 Jan 2024.

Mwebaze, E., Gebru, T., Frome, A., Nsumba, S. & Tusubira, J. iCassava 2019 Fine-Grained Visual Categorization Challenge (2019).

Ruder, S. An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms. Preprint at arXiv:1609.04747 (2016).

Kingma, D.P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. Preprint at arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Ahn, K., Zhang, Z., Kook, Y. & Dai, Y. Understanding adam optimizer via online learning of updates: Adam is ftrl in disguise. Preprint at arXiv:2402.01567 (2024).

Waheed, A. et al. An optimized dense convolutional neural network model for disease recognition and classification in corn leaf. Comput. Electron. Agric. 175, 105456 (2020).

Fang, T., Chen, P., Zhang, J. & Wang, B. Crop leaf disease grade identification based on an improved convolutional neural network. J. Electron. Imaging 29(1), 013004–013004 (2020).

Kunduracioglu, I. Cnn models approaches for robust classification of apple diseases. Comput. Decis. Mak. Int. J. 1, 235–251 (2024).

Kunduracioglu, I. Utilizing resnet architectures for identification of tomato diseases. J. Intell. Decis. Mak. Inf. Sci. 1, 104–119 (2024).

Kunduracioglu, I. & Pacal, I. Advancements in deep learning for accurate classification of grape leaves and diagnosis of grape diseases. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 131(3), 1061–1080 (2024).

Oyewola, D. O., Dada, E. G., Misra, S. & Damaševičius, R. Detecting cassava mosaic disease using a deep residual convolutional neural network with distinct block processing. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 7, 352 (2021).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed equally

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan, S.M., Roy, K.S., Hazarika, R.A. et al. Multi-kernel inception-enhanced vision transformer for plant leaf disease recognition. Sci Rep 15, 30997 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16142-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16142-x