Abstract

Data on clinical utility of IGRAs in BCG-vaccinated populations is limited. This cross-sectional study evaluated diagnostic performance of ELISPOT and ELISA-based IGRAs and compared them with conventional Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) for detecting Mtb infection in adult Pakistani population. Subjects (n = 325, age 18–64 years) recruited included active TB cases (n = 150), non-TB other pulmonary diseases patients (n = 50) and healthy individuals (n = 125). Two different IGRAs, X-DOT-TB (ELISPOT-based) and QFT-Plus (ELISA-based) were used to screen Mtb infection. Samples from 112/150 (74.7%) active TB patients, 10/50 (20.0%) non-TB other pulmonary diseases cases and 16/125 (12.8%) healthy individuals were X-DOT-TB positive, while 52.7% (29/55) active TB patients, 20.0% (4/20) non-TB other pulmonary diseases cases and 22.6% (12/53) healthy individuals tested by QFT-Plus had positive results. Sensitivity of X-DOT-TB and QFT-Plus was 79.5% (95%CI 77.4–81.5), and 55.7% (95%CI 52.9–58.5), respectively, significantly higher than TST 35.8% (95%CI 34.4–37.1, p < 0.05). Specificity of X-DOT-TB was 85.1% (95%CI 83.2–87.0), that of QFT-Plus was 78.1% (95%CI 75.3–80.9), comparable with TST specificity of 82.2% (95%CI 80.3-84.1, p > 0.05). IGRAs, particularly X-DOT-TB assay found to have greater sensitivity for detecting Mtb infection than TST. Our study suggests that IGRAs can be used as an adjunct diagnostic tool for detection of Mtb infection in BCG-vaccinated populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death due to infectious diseases around the globe and a threat to human health. Pakistan has the fifth-highest TB burden in the world, with a reported incidence rate of 264 per 100,000 people in 20221. Early diagnosis of TB is critical for curbing its spread and effectively reducing the disease burden.

Exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of TB leads to a spectrum of clinical conditions ranging from latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) to active tuberculosis disease. Early, rapid and correct diagnosis of Mtb infection is important not only to provide immediate treatment but also to break its transmission to other people2. Diagnosis of TB usually relies on analyzing clinical symptoms and using different diagnostic techniques such as radiology, histopathology, Mtb culture and molecular analysis3. Although considerable advances have been made in diagnostic methods for TB, the reliable and early detection of Mtb infection still has serious limitations. Clinicians mostly rely on immunoassays to establish evidence of Mtb exposure and infection.

The Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) has been used worldwide as a primary approach for Mtb infection screening. TST measure a delayed type of hypersensitivity response to a purified protein derivative (PPD) of Mtb. TST lacks specificity due to cross-reactions with non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) and/or Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination, which may lead to false positive results, a serious limitation in countries such as Pakistan, where BCG vaccination is mandatory4. Other limitations of the TST include the boosting phenomenon and the requirement for a follow-up patient visit5.

Serum-based interferon gamma (IFN-γ) release assays (IGRAs) have been established for the detection of Mtb infection. IGRAs measure the release of IFN-γ produced by T-cells stimulated in response to the Mtb-specific proteins, Early Secretory Antigenic Target 6 (ESAT-6) and Culture Filtrate Protein 10 (CFP 10). These antigens are absent in BCG strains and NTM6,7. The specificity of immunogens for the disease under consideration reduces the chance of false-positive results. Compared to the TST, IGRAs are more specific, and faster. They are ex vivo tests, which reduce the potential risk of adverse events. However, neither the TST nor the IGRAs can differentiate between TB infection and active TB disease5.

T-SPOT.TB (Oxford Immunotec, UK), QuantiFeron TB Gold plus (QIAGEN GmbH, Germany) and X.DOT-TB (TB Healthcare, China) are commercially available IGRA kits for immunodiagnosis of Mtb infection. T-SPOT.TB and X.DOT-TB use ESAT-6 and CFP-10 as antigenic targets while QuantiFeron TB Gold plus (QFT-Plus) uses a cocktail of ESAT-6, CFP-10 and multiple synthetic peptide chains. Commercially available IGRA kits differ in the technique used for the detection of IFN-γ, being based either on Enzyme Linked ImmunoSorbent Assays (ELISA) or Enzyme-Linked Immunospot (ELISPOT) techniques. T-SPOT.TB and X.DOT-TB kits are based on ELISPOT and detect IFN-γ release from Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMC) samples whereas QFT-Plus is based on ELISA and detects IFN-γ release in whole blood samples3. The diagnostic performance of IGRA kits may be affected by differences in assay format and needs to be explored in target populations.

The diagnostic efficiency of IGRA in Mtb-infected cases is still in question based on single and multicenter study data8,9. Various studies from low endemic countries around the world have already signified the role of IGRA in detecting TB infection, but there is limited data available on the efficiency of IGRA for the immunodetection of Mtb infection, particularly in high TB burden countries8,10. Most of the data regarding the detection of Mtb infection comes from high-income, low TB burden countries where BCG vaccination is not mandatory11. However, studies from low- and middle-income countries with a high TB burden are limited. It is important that the efficiency of IGRA for the diagnosis of Mtb infection is evaluated in high TB burden countries like Pakistan. A few studies assessing the efficiency of IGRAs have been published in Pakistan12,13, but none to date have compared the diagnostic performance of different IGRAs with conventional TST.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of IGRAs in the detection of Mtb infection (by evaluating the sensitivities and specificities of TST and IGRAs) in our setting where TB is endemic and most of the population is BCG vaccinated. Since there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of latent TB infection, we used active TB patients (Mtb culture-positive), patients with non-TB other pulmonary diseases (Mtb culture-negative), and low-risk healthy individuals as the reference groups in this study.

Materials and methods

Study design and study subjects

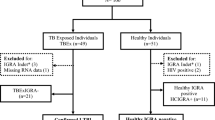

For this cross-sectional study, total 325 subjects were recruited for three study groups: active tuberculosis (ATB) patients (n = 150), non-TB other pulmonary diseases (NTBOPD) patients (n = 50) and healthy individuals (n = 125). For all study groups, subjects that were 18 to 64 years of age from both genders were recruited.

The study was carried out between May 2019 to June 2021, after taking ethical approval from Institutional Review Board, Dow University of Health Sciences (DUHS), Karachi, Pakistan (IRB-1364/DUHS/Approval/2019/), and all methods were performed in accordance with the applicable guidelines and regulations. Study participants were briefed about the study and their informed consent was taken.

All study subjects underwent chest radiographic examination for preliminary TB screening. Different microbiological [Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) Smearing and Mtb Culturing] and molecular (GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay) tests were performed for the confirmation of M. tuberculosis (Mtb) infection in active TB and non-TB other pulmonary diseases patients. In healthy individuals these tests were not performed. Study participants were allocated to these groups based on the following criteria (Fig. 1).

-

Active TB patients (n = 150): This group included newly diagnosed pulmonary TB patients who had not started anti-TB treatment. Patients were diagnosed by physicians based on clinical symptoms, in combination with positive radiological, microbiological (AFB smearing and Mtb culturing), or molecular (GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay) findings consistent with active TB. AFB negative subjects with other evidence of active TB such as positive culture or GeneXpert results were also included based on the physician’s diagnosis.

-

Non-TB other pulmonary diseases patients (n = 50): This group included patients with other pulmonary diseases excluding TB (such as asthma, lung cancer, pneumonia and others). Subjects recruited to this group had Chest X-Ray non-consistent with TB, negative microbiological (AFB smearing and Mtb culturing) and molecular results for active TB.

-

Healthy individuals (n = 125): This group included healthy BCG-vaccinated adults who were apparently free from TB symptoms, had no close or minimum contact with TB patients (at low risk for developing TB) and had negative Chest X-ray reports for TB after radiological examination.

Active TB cases (Mtb culture-positive) served as the positive control, whereas healthy subjects and patients with non-TB other pulmonary diseases were considered the negative control for the detection of Mtb infection in the study.

Sample collection and processing

Blood samples (10 ml) were collected from all the study subjects for Interferon Gamma Release Assays (IGRAs). Sputum samples were collected from patient groups and assessed for Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) microscopy and culturing. All study participants were subjected to radiological examination (Chest X-ray), Tuberculin skin test (TST) and IGRAs for the detection of Mtb infection.

Tuberculin skin test (TST)

TST was administered to all study participants by the Mantoux method. Purified Protein Derivative (PPD) (0.1 ml, equivalent to five tuberculin units) was administered intradermally on the forearm. A circle was drawn around the administered area using a marker pen. The diameter of induration (skin response) was measured in millimeters (mm) using a ruler after 48–72 h. TST was performed and read by trained and experienced staff. Skin indurations with diameters of 0–5 mm and > 5 mm were considered as negative and positive respectively.

Interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs)

Two different IGRA methods (ELISA and ELISPOT) were used to detect Mtb infection. The ELISPOT assay was performed using the X-DOT-TB™ kit (TB Healthcare, China), while the ELISA was carried out using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Germany). Both assays were performed according to the respective manufacturer’s instructions.

Evaluation of diagnostic performance of IGRAs and TST

Parameters used for the evaluation of the diagnostic performance of IGRAs and TST were sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (LR+), negative likelihood ratio (LR−), diagnostic accuracy and diagnostic odds ratio. Mtb culturing was used as the “gold standard” to evaluate the sensitivity of IGRAs and the TST in active TB patients. The sensitivity of both IGRAs and the TST was calculated from Mtb culture-positive active TB patients. Specificity of both IGRAs and TST was calculated from control groups of non-TB other pulmonary diseases patients and healthy individuals.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) version 20.0. Distribution of continuous data was checked by Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous data based on normality are presented as either median [Interquartile range (IQR)] or mean ± S.D. Frequencies and percentages are reported for categorical variables. Baseline characteristics of study participants (for categorical variables) were compared by chi-square or fisher exact test.

The diagnostic performance of the immunological assays (TST, X-DOT-TB and QFT-Plus) were compared by McNemar chi-square test. Concordance between the immunological assays (TST, X-DOT-TB and QFT-Plus) was examined using proportion agreement and kappa (k) coefficient. k coefficient values were interpreted as k > 0.75 indicated excellent agreement; k = 0.4–0.75 good agreement; and k < 0.4 poor agreement.

Binary logistic regressions (univariate and multivariate) were used to evaluate the factors associated with positive X-DOT-TB IGRA results. Results of logistic regression were presented as crude odds ratios and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). P-values which were < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

Demographics of the study population

A total of 325 subjects including 150 active TB patients, 50 non-TB other pulmonary diseases cases and 125 healthy individuals were enrolled in the study. Demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. Briefly, the majority of study participants were 18–30 years of age (47.4%), male (55.1%), lived in Karachi district east (44.0%) and were employed (54.2%). A BCG scar was present in 86.2% of the study participants. The median age of active TB patients, non-TB other pulmonary diseases cases and healthy individuals were 34.5 (IQR 23–50), 27 (IQR 24–37) and 44 (IQR 30–51) years, respectively. Significant differences in age, BMI and the proportion of BCG vaccinated participants were observed between TB patients and other groups (p < 0.001). Compared to other groups, most of the active TB patients were underweight (40.7%), smokers (20.7%) and had household TB contacts (32.0%). The majority of healthy individuals were BCG vaccinated (96.8%) and had BCG scar (96.0%) and no history of TB contacts (94.4%).

Clinical characteristics

The most common presenting symptoms in active TB patients were cough (92.0%), fever (73.3%), weight loss (72.0%) and shortness of breath (64.7%). Non-TB other pulmonary diseases patients presented with shortness of breath (100.0%), cough (90.0%) and body pain (58.0%). The most prevalent underlying co-morbidity in active TB patients was diabetes, followed by hyper and hypotension (Table 2). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was the most prevalent respiratory condition among non-TB other pulmonary diseases cases. Of the 50 patients in the non-TB group, 12 had COPD and 8 had pleural effusion.

Immunological findings

Mtb infection was detected using three immunoassays, namely the Tuberculin skin test (TST) and two IGRA assays (X-DOT-TB and QFT-Plus). These methods were compared with each other to evaluate their diagnostic performance and the concordance among the three tests.

Tuberculin skin test (TST) results

TST was performed on 325 participants from three study groups (ATB = 150, Non-TB other pulmonary diseases = 50 and Healthy individuals = 125). Three subjects were lost at follow-up. TST results were positive (> 5 mm induration) in 52 (35.3%) active TB patients, 16 (32.0%) non-TB other pulmonary diseases cases and 15 (12.0%) healthy individuals (Table 3).

X-DOT-TB assay results

X-DOT-TB which is an ELISPOT based IGRA kit used for detection of Mtb infection, was performed in total 325 subjects (ATB = 150, NTBOPD patients = 50, Healthy individuals = 125). X-DOT-TB results were positive in 112 (74.7%) active TB patients, 10 (20.0%) non-TB other pulmonary diseases cases and 16 (12.8%) healthy individuals (Table 4).

QFT-Plus assay results

QFT-Plus which is an ELISA based IGRA kit used for detection of Mtb infection, was performed in 128 subjects (ATB = 55, NTBOPD patients = 20, Healthy individuals = 53). QFT-Plus results were positive in 29 (52.7%) active TB patients, 4 (20.0%) non-TB other pulmonary diseases cases and 12 (22.6%) healthy individuals (Table 5).

Comparison of sensitivity and specificity of IGRAs (X-DOT-TB and QFT-Plus) and TST

Of the 139 active TB patients (with 11 missing culture results), 137 (98%) were found culture positive for M. tuberculosis. All non-TB other pulmonary diseases patients were culture negative and all healthy individuals had normal Chest X-Rays.

The sensitivity and specificity of all three immunological assays were evaluated. Diagnostic sensitivity was calculated from active TB group using Mtb culturing as gold standard. Among the 137 Mtb culture positive cases, 109 were detected positively by both Mtb culturing and X-DOT-TB assay, and 49 were positive by both Mtb culturing and TST. In addition, among 52 cases tested, 29 were found positive in both Mtb culturing and QFT-Plus assay.

The sensitivity of the three assays, based on culture-confirmed cases, was 79.5% (109/137; 95% CI: 77.4–81.5) for X-DOT-TB, 55.7% (29/52; 95% CI: 52.9–58.5) for QFT-Plus, and 35.8% (49/137; 95% CI: 34.4–37.1) for the TST.

Of the 175 controls (including 125 healthy individuals and 50 non-TB other pulmonary diseases patients), 149 and 144 were detected positively by X-DOT-TB and TST, respectively. Of the 73 controls (including 53 healthy individuals and 20 non-TB other pulmonary diseases patients), 57 were detected positively by QFT-Plus.

The overall diagnostic specificity for X-DOT-TB, QFT-Plus and TST was 85.1% (149/175; 95% CI 83.2–87.0), 78.1 (57/73; 75.3–80.9) and 82.2% (144/175; 95% CI 80.3-84.08) respectively.

The diagnostic sensitivity of both IGRA assays i.e. X-DOT-TB and QFT-Plus was found to be significantly higher than TST (p < 0.001 and p = 0.029 respectively, McNemar chi-square test), furthermore QFT-Plus had a significantly lower sensitivity than X-DOT-TB (p = 0.027). No significant differences were found between the specificities of X-DOT-TB and TST (p = 0.487), QFT-Plus and TST (p = 0.607) and X-DOT-TB and QFT-Plus (p = 0.549) (Fig. 2).

Comparison of sensitivity and overall specificity of X-DOT-TB, QFT-Plus and TST. *Significant difference between sensitivity of X-DOT-TB and TST, p- value < 0.001. ** Significant difference between sensitivity of QFT-Plus and TST, p- value = 0.029. *** Significant difference between sensitivity of QFT-Plus and X-DOT-TB, p-value = 0.027. # No significant difference was found between specificity of the assays (p > 0.05). TST: Tuberculin skin test.

A comparative evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of all the three assays is presented in Table 6.

Diagnostic performance of IGRAs (X-DOT-TB and QFT-Plus) and TST

The diagnostic performance of all three assays (X-DOT-TB, QFT-Plus, and TST) was evaluated. The positive predictive value (PPV) of X-DOT-TB was found to be 81.1% and indicates that the probability of positively detecting Mtb infected patients was 81.1% for the assay. The negative predictive value (NPV) was found to be 79.6%, indicating that there was a 79.6% probability that individuals with a negative test result were disease-free. The positive likelihood ratio of X-DOT-TB when performed on Mtb-positive patients to have a positive result was 6.4 and the negative likelihood ratio of a disease positive individual to test negative was 0.24. The Diagnostic Accuracy of X-DOT-TB was 79.1% and the Diagnostic odds ratio was 26.6.

The PPV, NPV, LR+ and diagnostic accuracy of the QFT-Plus assay were found to be 64.5%, 70.3%, 2.2 and 56.6% respectively, and the PPV, NPV, LR+ and diagnostic accuracy of TST were found to be 60.4%, 60.2%, 1.94 and 36.6% respectively.

When compared with each other, X-DOT-TB showed the highest diagnostic performance, followed by QFT-Plus and TST. QFT-plus gave better diagnostic performance than TST. A comparative evaluation of the diagnostic performance of the three assays is presented in Table 7.

Concordance between IGRAs (X-DOT-TB and QFT-Plus) and TST

For further comparison of X-DOT-TB, QFT-Plus and TST the concordance between these assays was measured by kappa (k) coefficient. Good agreement (k = 0.46) was resulted between QFT-Plus and X-DOT-TB, while poor agreement (k = 0.314) and (k = 0.23) was found between X-DOT-TB and TST and QFT-Plus and TST, respectively. The concordance of all three immunological assays is presented in Table 8.

Factors associated with positive X-DOT-TB assay results

The association between baseline characteristics of study participants and positive X-DOT-TB assay results was evaluated using binary logistic regression analysis (Table 9). Multivariate logistic regression showed that subjects > 50 years of age (aOR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.0-3.9, p = 0.046), those who were underweight (aOR = 3.9, 95% CI 1.4–10.8, p = 0.007) and individuals with known exposure to TB contacts (aOR = 1.8, 95% CI 1.0-3.3, p = 0.041) were significantly more likely to test positive for Mtb infection. In contrast, subjects of urdu-speaking ethnic background had a significantly lower risk of testing positive compared to other ethnic groups (aOR = 0.44, 95% CI 0.24–0.81, p = 0.008).

Discussion

Tuberculosis is one of the deadliest infectious diseases around the world and needs rapid detection in order to prevent its spread and to be treated appropriately. After exposure to the Mtb pathogen, the host immune response is activated to prevent the disease by destroying the pathogen or by establishing the state of latency. Some infected individuals are asymptomatic, exhibiting latent tuberculosis and showing no abnormalities in chest X-rays and negative microbiological culture. Mtb-infection in such individuals can only be detected using immunodiagnostic tests: Tuberculin skin test (TST) and interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs). If Mtb infection progresses, it may develop into active tuberculosis (ATB), typically presenting with mild to severe clinical symptoms, often abnormal chest X-rays, and positive microbiological, molecular and immunodiagnostic assays14.

TST is a widely used immunodiagnostic assay for the detection of Mtb infection because it is an easy technique, provides early results and is cost effective. However it is reported that its specificity is compromised in individuals with BCG vaccination and in those who have non-tuberculous mycobacterium infection15,16. Emerging global data on the diagnostic efficiency of IGRAs in different populations and comparisons with other available diagnostic tools indicate their diagnostic utility. However, more data generated in high TB burden countries is needed to draw conclusions. This study was designed to compare the diagnostic performance of IGRAs (X-DOT-TB and QFT-Plus) with TST in the Pakistani population to generate data from a high TB burden country where the majority of the population are vaccinated with BCG. The sensitivity of X-DOT-TB, QFT-Plus and TST was found to be 79.5%, 55.7% and 35.8% respectively. The diagnostic sensitivity of both IGRA assays i.e. X-DOT-TB and QFT-Plus was found to be significantly higher than TST (p < 0.05). There has only been one other study conducted in Pakistan to date which compared the sensitivity of the QuantiFERON TB-Gold (QFT-G) assay with the TST, reporting the sensitivity of the two assays as 80% and 28% respectively12, thereby highlighting the higher sensitivity of IGRA-based assay. Our study also demonstrated higher sensitivities for both IGRA assays compared to TST. Furthermore, similar studies conducted in high TB burden countries like Brazil, India and China where BCG vaccination is mandatory have reported that IGRAs have higher sensitivity as compared to TST17,18,19. In contrast, studies from low TB burden countries such as Egypt and the United Kingdom have reported much higher sensitivities for TST in the range of 83–95%20,21.

When compared, the overall diagnostic specificity for X-DOT-TB, QFT-Plus and TST were found to be 85.1%, 78.1% and 82.2% respectively. We did not find a significant difference in the specificity of IGRAs and TST. Our results are in agreement with a previous study conducted in the BCG-vaccinated Indian population, which reported the specificity of TST to be around 75.5%18. However, reports from low TB burden settings like Poland show a smaller difference in the comparative sensitivity of the IGRA-based QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) assay and the TST (65.1% and 55.8%, respectively), and higher specificities of 87.7% and 71.7% respectively22. This suggests that the performance of IGRAs and TST differs from population to population. It has been reported that BCG vaccination effects the specificity of TST results, with a specificity of up to 97% being found in unvaccinated populations, whereas in BCG vaccinated populations the specificity was found to be 60%23. However, it has also been reported that BCG vaccination when administered between birth and age one does not affect TST results after the age of 10 years24,25. High false negative TST results were explained that it might be because development of latent TB infection requires 6–8 weeks post exposure to Mtb26. Although the specificity of TST and IGRAs was found to be comparable in our study, other diagnostic parameters of TST, such as PPV and NPV, were much lower compared to both IGRAs. Additionally, there was poor agreement between X-DOT-TB and TST and QFT-Plus and TST with kappa indexes of 0.31 and 0.23 respectively. These results are in agreement with other studies27,28. While the TST is more cost effective, IGRAs have been reported to show better diagnostic performance than the TST for detecting Mtb infection, particularly in BCG-vaccinated populations17,18,19.

Our study also compared the diagnostic performance of the two different IGRA methods, namely ELISPOT and ELISA, performed using the commercially-available ELISPOT-based X-DOT-TB and IGRA-based QFT-Plus kits, respectively. QFT-Plus is an advanced version of QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) ELISA and was introduced in 2017, while X-DOT-TB is a Chinese Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) approved kit for immunodiagnosis of Mtb infection, also introduced in 2017.

The sensitivity of the two immunoassays was found to be significantly different, with QFT-Plus ELISA showing significantly lower sensitivity than X-DOT-TB assay (55.7% for QFT-Plus and 79.5% for X-DOT-TB, p = 0.027). However, the specificity (85.1% for X-DOT-TB and 78.1% for QFT-Plus) was comparable and good agreement was found between the assays.

It has been reported that the sensitivity of the QFT-GIT assay is strongly affected by immunosuppressed conditions, whereas these conditions have only a slight effect on the sensitivity of the ELISPOT-based T-SPOT-TB kit29,30. Multiple studies have been conducted to compare the two IGRA methods in different high and low TB burden countries. A comparative study conducted in China reported the sensitivity and specificity of 85.2% and 63.4% respectively for T-SPOT-TB (ELISPOT method) and 84.8% and 60.5% respectively for QFT-GIT (ELISA method)8. Data from low TB burden country, Singapore showed T-SPOT-TB (ELISPOT assay) has better diagnostic performance compared to QFT-IT (ELISA assay)31, whereas data from Germany (another low TB burden country) showed only a slight difference in diagnostic performance between the two methods11.

A limitation of our study was the small sample size for the QFT-Plus assay, as it was performed only in 128 individuals. Additionally, children, immunocompromised, and high-risk background individuals were not included in the study.

This is the largest reported study to date in Pakistan that directly compares the two IGRA methods with TST to evaluate their performance in the detection of Mtb infection. The data generated from this study will potentially help in drawing a conclusion to the ongoing global debate about the clinical utility of IGRAs for the detection of Mtb infection.

Further studies are needed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of IGRAs for detecting Mtb infection in different age groups. This study should further be carried out in children and young adults. Furthermore, studies in extra pulmonary TB patients, immunosuppressed patients such as those with HIV, and patients with multiple comorbidities need to be conducted. Data regarding immunodiagnostic tools including IGRA and TST is insufficient from Pakistan; more studies are required for recommendation to be consolidated.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Schwalb, A., Samad, Z., Yaqoob, A., Fatima, R. & Houben, R. M. G. J. Subnational tuberculosis burden estimation for Pakistan. PLOS Glob Public Health. e0003653. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003653 (2024).

Rangaka, M. X. et al. Predictive value of interferon-γ release assays for incident active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 12 (1), 45–55 (2012).

Dai, Y. et al. Evaluation of interferon-gamma release assays for the diagnosis of tuberculosis: an updated meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31 (11), 3127–3137 (2012).

Onur, H., Hatipoğlu, S., Arıca, V., Hatipoğlu, N. & Arıca, S. G. Comparison of quantiferon test with tuberculin skin test for the detection of tuberculosis infection in children. Inflammation 35 (4), 1518–1524 (2012).

Pai, M. & Menzies, D. The New IGRA and the Old TST: Making Good Use of Disagreement. 529–531 (American Thoracic Society, 2007).

Yi, L. et al. Evaluation of QuantiFERON-TB gold plus for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in Japan. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 30617 (2016).

Ravn, P. et al. Prospective evaluation of a whole-blood test using Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10 for diagnosis of active tuberculosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 12 (4), 491–496 (2005).

Du, F. et al. Prospective comparison of QFT-GIT and T-SPOT. TB assays for diagnosis of active tuberculosis. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 1–9 (2018).

Kang, W-L. et al. Interferon-gamma release assay is not appropriate for the diagnosis of active tuberculosis in high-burden tuberculosis settings: a retrospective multicenter investigation. Chin. Med. J. 131 (3), 268 (2018).

Sharma, S. K., Vashishtha, R., Chauhan, L., Sreenivas, V. & Seth, D. Comparison of TST and IGRA in diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in a high TB-burden setting. PloS One. 12 (1), e0169539 (2017).

Detjen, A. et al. Interferon-γ release assays improve the diagnosis of tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in children in a country with a low incidence of tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45 (3), 322–328 (2007).

Khalil, K. F., Ambreen, A. & Butt, T. Comparison of sensitivity of QuantiFERON-TB gold test and tuberculin skin test in active pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 23 (9), 633–636 (2013).

Masood, K. I. et al. Testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection using the QuantiFERON-TB GOLD assay in patients with comorbid conditions in a tertiary care endemic setting. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 6(1), 1–8 (2020).

World Health Organization, World Health Organization Staff. Global tuberculosis report 2013. (World health organization, 2013).

Lienhardt, C. et al. Evaluation of the prognostic value of IFN-γ release assay and tuberculin skin test in household contacts of infectious tuberculosis cases in Senegal. PloS One. 5 (5), e10508 (2010).

Çaǧlayan, V. et al. Comparison of tuberculin skin testing and QuantiFERON-TB Gold-In tube test in health care workers (2011).

Ferreira, T. F., Matsuoka, P. F. S., AMd, S. & Caldas AdJM. Diagnosis of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: tuberculin test versus interferon-gamma release. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 48, 724–730 (2015).

Syed Ahamed Kabeer, B., Raman, B., Thomas, A., Perumal, V. & Raja, A. Role of QuantiFERON-TB gold, interferon gamma inducible protein-10 and tuberculin skin test in active tuberculosis diagnosis. PLoS One. 5 (2), e9051 (2010).

Zhou, J., Kong, C., Shi, Y., Zhang, Z. & Yuan, Z. Comparison of the interferon-gamma release assay with the traditional methods for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children. Medicine 93(15) (2014).

Abdel-Samea, S. A., Ismail, Y. M., Fayed, S. M. A. & Mohammad, A. A. Comparative study between using quantiferon and tuberculin skin test in diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Egypt. J. Chest Dis. Tuberculosis. 62 (1), 137–143 (2013).

Kampmann, B. et al. Interferon-γ release assays do not identify more children with active tuberculosis than the tuberculin skin test. Eur. Respir. J. 33 (6), 1374–1382 (2009).

Wlodarczyk, M. et al. Interferon-gamma assay in combination with tuberculin skin test are insufficient for the diagnosis of culture-negative pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS One. 9 (9), e107208 (2014).

Metcalfe, J. Z. et al. Interferon-γ release assays for active pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis in adults in low-and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 204 (suppl_4), S1120–S9 (2011).

Menzies, D., Pai, M. & Comstock, G. Meta-analysis: new tests for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: areas of uncertainty and recommendations for research. Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (5), 340–354 (2007).

O’Garra, A. et al. The immune response in tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31, 475–527 (2013).

Lee, S. W. et al. Time interval to conversion of interferon-γ release assay after exposure to tuberculosis. Eur. Respir. J. 37 (6), 1447–1452 (2011).

Venkatappa, T. K. et al. Comparing QuantiFERON-TB gold plus with other tests to diagnose Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 57 (11), e00985–e00919 (2019).

Xia, H. et al. Diagnostic values of the QuantiFERON-TB gold In-tube assay carried out in China for diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS One. 10 (4), e0121021 (2015).

Hong, S. I., Lee, Y-M., Park, K-H. & Kim, S-H. Is the sensitivity of the QuantiFERON-TB gold in-tube test lower than that of T-SPOT. TB in patients with miliary tuberculosis? Clin. Infect. Dis. 59 (1), 142 (2014).

Bae, W. et al. Comparison of the sensitivity of QuantiFERON-TB gold In-Tube and T-SPOT. TB according to patient age. PLoS One. 11 (6), e0156917 (2016).

Chee, C. B. et al. Comparison of sensitivities of two commercial gamma interferon release assays for pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46 (6), 1935–1940 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Chinese Academy of Sciences and Dow University of Health Sciences (DUHS) for their support and assistance in conducting this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the International Partnership Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant number 153311KYSB20170001 to Lijun Bi). The funding body had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

UI: Sampling, Data curation, Methodology, Result compilation, Data analysis, Writing-original draft. SK: Investigation, Data curation, Data analysis, Writing – review & editing. MSB: Patients induction, Review & editing. JF: Conceptualization, Project Management, Contribution of materials, Data analysis, Review and editing of manuscript. LB: Conceptualization, Funding, Contribution of materials. SA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was carried out after taking ethical approval from Institutional Review Board, Dow University of Health Sciences (DUHS), Karachi, Pakistan (IRB-1364/DUHS/Approval/2019/), and all methods were performed in accordance with the applicable guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ishrat, U., Khan, S., Baig, M.S. et al. Comparison of interferon gamma release assays and tuberculin skin test performance for diagnosing Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in the Pakistani population. Sci Rep 15, 35788 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16605-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16605-1