Abstract

Hydroxyapatite (HA) nanoparticles synthesized from bio-waste sources like eggshells offer a sustainable and biocompatible alternative for bone regeneration. This study successfully synthesized nano-hydroxyapatite from chicken eggshell-derived calcium precursors and comprehensively characterized it. X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirmed the formation of a highly crystalline, phase-pure HA structure, while Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) revealed characteristic phosphate, hydroxyl, and carbonate bands, resembling biological apatite. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) showed spherical nanoparticles (~ 11.2 nm) with uniform distribution, enhancing bioactivity. Hemocompatibility assays demonstrated concentration-dependent hemolysis, with minimal RBC disruption (< 7%) at 12.5 mg/ml, mitigated further by protein corona formation. In vitro studies revealed excellent osteoblast (MC3T3-E1) adhesion and spreading on HA surfaces, indicating osteoconductivity. Additionally, HA nanoparticles exhibited dose-dependent free radical scavenging activity (up to 84.7% at 200 µg/ml) and significantly suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and IL-18) in LPS (Lipopolysaccharide)/ATP (Adenosine triphosphate)-stimulated macrophages, highlighting anti-inflammatory potential. These findings collectively underscore the suitability of eggshell-derived nano-HA for bone tissue engineering, combining eco-friendly synthesis, structural biomimicry, and multifunctional bioactivity to promote osteogenesis and mitigate inflammation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a lot of interest in developing environmentally friendly and sustainable methods for creating biomaterials, especially in the domains of materials science and biomedical engineering1. The main inorganic component of human bones and teeth is nano-hydroxyapatite (HA), a biocompatible material widely used in orthopedic implants, bone tissue engineering, and dentistry. Its remarkable bioactivity and compatibility with living tissues make it a very attractive material for regenerative medicine2. Historically, chemical reagents—effective but sometimes expensive and wasteful—have driven hydroxyapatite manufacture, raising environmental concerns1,2,3.

Composed mostly of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), eggshells a significant bio-waste product—provides a reasonably priced and eco-friendly substitute as a calcium source for the production of hydroxyapatite4. About 94% of eggshells are made of calcium carbonate, which is accompanied by trace minerals that are beneficial for bone formation, including magnesium and strontium. By recycling trash and creating useful biomaterials, this biogenic method solves environmental issues4,5,6.

Usually, calcium carbonate must be cleaned, calcined, and chemically treated to create nano-hydroxyapatite from eggshells7. Many methods including sol-gel, hydrothermal, and precipitation—have been used to accomplish this change. Renowned for its simplicity and efficacy, the precipitation technique creates nanoparticles with controlled size and shape by reacting calcium sources from eggshells with phosphate precursors8. High-temperature, high-pressure hydrothermal processes produce very crystalline materials with improved bioactivity and stability9,10,11. On the other hand, the sol-gel technique allows exact control over chemical composition and microstructure by means of conversion of a sol into a gel state during synthesis11. HA nanostructured films can be synthesized from chlorapatite targets using pulsed laser deposition (PLD) under dry or water vapor conditions, producing coatings with controlled grain size, roughness, and mechanical properties suitable for bone implant applications. This approach offers a simple and cost-effective method to obtain crystalline HA with enhanced bioactive characteristics and stability in simulated body fluid12.

The eggshell-derived method has several benefits over traditional HA synthesis, including better biocompatibility, lower production costs, and environmental sustainability13. The natural source of eggshell-derived HA makes it compatible with biological systems, which is essential for uses in bone repair and regeneration14. Research have shown that the physicochemical characteristics of eggshell-derived HA, including crystallinity, particle size, and bioactivity, are similar to those of HA produced by conventional chemical processes, making it a possible replacement for biomedical uses13,15,16,17. Hydroxyapatite–shrimp crust nanocomposite thin films, deposited on titanium substrates via electrophoretic deposition, have shown promising mechanical strength, bioactivity, and antibacterial properties for bone implant applications. Characterization confirmed their polycrystalline structure, low dissolution rate in simulated body fluid, and effective inhibition of E. coli growth18.

This creative approach follows the concepts of green chemistry and raises the possibility of creating fairly priced, eco-friendly bone replacements. One encouraging way to advance biomedical technologies and solve global issues in resource use and waste management is the use of eggshells as a precursor for the creation of nano-hydroxyapatite19.

HA has gained increasing attention as a key biomaterial in tissue engineering due to its remarkable biocompatibility, bioactivity, and chemical similarity to the mineral component of bone. HA provides a bone-like structure that supports cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, making it highly suitable for bone regeneration and repair. Its excellent osteoconductive properties facilitate the integration of implants with surrounding bone tissue20.

This project aims to create and enhance a new technique for manufacturing hydroxyapatite (HA)-based bio composites from easily accessible raw materials. Specifically, leftover eggshells were used as a sustainable calcium source to generate very pure, nanocrystalline HA powder. A variety of analytical tools XRD, SEM with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS), high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), and FTIR were used to characterize the manufactured HA. Emphasizing its possible uses in bone regeneration, the bioactive qualities of the resulting bioceramic composite were more investigated.

Materials and methods

Using chicken eggshells, a readily available biowaste material, and this work proposed a new approach for producing very porous and biocompatible HA ceramic scaffolds. The preparation method guaranteed efficient conversion of calcium carbonate from eggshells into HA by several stages. According to the Roudana et al.21 protocol, unprocessed eggshells were cleaned with deionized water, boiled for 30 min, and oven-dried for 30 min at 100 °C. They were calcined in a muffle furnace for two hours at 1200 °C after being ground into a fine powder using an electrical grinder. The reaction that follows shows how the high temperature treatment hastened the transformation of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) to calcium oxide (CaO) while generating carbon dioxide:

The calcined eggshell powder was then dissolved in distilled water as follows to promote the hydration of calcium oxide (CaO) into calcium hydroxide

While continuously monitoring the pH with a calibrated digital pH meter (± 0.01 accuracy), a 0.6 M orthophosphoric acid (H₃PO₄) solution was added dropwise to the Ca(OH)₂ suspension under constant magnetic stirring until the pH reached 8.5. To maintain the pH at this value, stirring was continued for an additional 10 min, during which small volumes of H₃PO₄ (to decrease pH) or Ca(OH)₂ slurry (to increase pH) were added as necessary. This controlled pH adjustment facilitated the precipitation of HA according to Eq. (3):

The mixture was left undisturbed at room temperature for 48 h to allow the precipitate time to stabilize and form HA. A white, crystalline HA powder was produced by oven-drying the resulting precipitate at 100 °C and then calcining in a muffle furnace for two hours at 1200 °C. Utilizing eggshell waste, this method provides a productive and eco-friendly method of producing HA, which could be utilized in biomedical implants and tissue engineering. The general process for making HA scaffolds from eggshells is depicted in Fig. 1.

Schematic of the process for turning chicken eggshells into HA scaffolds. raw eggshells, grinding them into powder, calcining calcium carbonate (CaCO₃CaCO₃) to calcium oxide (CaOCaO), hydrating calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂Ca(OH)₂), reacting with orthophosphoric acid to form hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO₄)6(OH)2Ca10(PO)6(OH)2), and finally drying and calcining to produce crystalline HA powder.

Hemocompatibility test

Fresh blood samples were taken from ten healthy donors and distributed into heparin-coated tubes based on the method of the national institute of health (NIH), food and drug administration (FDA), and as per the declaration and regulation of Helsinki of 1975 as a statement of ethical principles. Permission was obtained from the hospitals of the medical city in Baghdad, Iraq, and approved by the institutional ethical committee of the Department of Biotechnology, College of Applied Sciences, University of Technology, Baghdad, Iraq (ID: ASBD 2024-UOT-7 dated 14/09/2024. Study participants were informed about the value of the study before we collected any samples. Informed consent was obtained from the study participants.

Human blood has been collected and treated with 3.8% sodium citrate to prevent coagulation. After being separated by centrifugation, the red blood cells (RBCs) were rinsed five times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a pH of 7.4 in order to eliminate plasma and other substances. For the hemolysis test, a final suspension of 5% (v/v) RBCs in PBS was made. 200 µL of the RBC suspension was used to incubate HA nanoparticles at varying concentrations (12.5, 25, and 50 mg/ml). To evaluate the function of protein corona formation, experiments were carried out both with and without 2% blood plasma. After two hours of static incubation at room temperature, the samples were centrifuged. To measure the hemolytic effect, the absorbance of hemoglobin released into the supernatant was measured at 540 nm. Positive Control: A solution of 0.2 ml of the RBC suspension and 0.8 ml of deionized water that causes total hemolysis. The absence of hemolysis is represented by the negative control, which is a solution of 0.8 ml PBS and 0.2 ml of the RBC suspension. The percentage of hemolysis was determined using the following formula17:

The OD sample is the optical density of the test sample, the OD negative controlis the optical density of the negative control, and the OD positive control is the optical density of the positive control.

After that, the samples were subjected to further analyses by optical microscopy and fluorescent microscopy.

Antioxidant activity of the prepared HA nanoparticles

The antioxidant properties of the HA nanoparticles were measured using stable DPPH (2,2-diphemyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radicals, following a modified protocol based on the literature22. To assess radical scavenging efficiency, NPs were tested at concentrations ranging from 6.25 to 100 µg/ml. For every test, 50 µL of the nanoparticle sample was mixed with 450 µL of DPPH solution, and the final volume was adjusted to 1 ml with 100% ethanol. Ascorbic acid was utilized as the reference standard. The samples and the control were incubated in the dark at 25 °C for 30 min. Absorbance was quantified at 517 nm, and scavenging activity was calculated using the appropriate equation:

Regeneration of MC3T3-E1 cells by HA nanoparticles

To assess the impact of HA nanoparticles on MC3T3-E1 cells (Purchased from Sigma), we initially cultured the cells under standard conditions until reaching confluence. Afterward, they were exposed to HA nanoparticles at a concentration of 25 µg/ml. The treated cells were kept in incubation for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO₂. The cells were examined using SEM microscope before and after treatment23.

In-vivo model

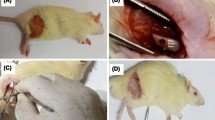

Male C57BL/6 mice weighing 20 g and aged 6–8 weeks were used as the animal model for acute peritonitis. The animals were divided into 3 groups, each group (5 animals. The first group was intraperitoneally injected with sterile PBS. The second group was injected intraperitoneally with LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) and ATP (Adenosine triphosphate) at a dose of 500 µg/kg. While the third, fourth, and fifth groups were injected with LPS + ATP at a dose of 500 µg/Kg with different doses of HA nanoparticles (6.25, 12.5, and 25 200 µg/Kg, respectively). Seven hours later, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation by skilled personnel, and 1 ml of blood was collected using cardiac puncture. ELISA was used to quantify the amount of IL-1β and IL-18. The institutional guidelines of the University of Technology, Baghdad, Iraq, were also fully complied with, which were approved by the institutional ethical committee, approval ID: ASBD 2024-UOT-7 dated 14/09/2024. Furthermore, this study is reported in accordance with the applicable ARRIVE guidelines.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (version 8), ImageJ, and Origin 2021 software. Data were analyzed via one-way ANOVA, with significance levels set at p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01, and *p ≤ 0.001. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD)17,21.

Results and discussion

The XRD pattern shown in Fig. 2 represents the crystalline structure of HA nanoparticles synthesized from eggshell-derived calcium precursors. The distinct and sharp peaks indicate the formation of a well-crystallized HA phase, corroborating the successful conversion of the calcium source into hydroxyapatite. The XRD pattern exhibits characteristic peaks that correspond to the standard hydroxyapatite phase, as defined by the Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS card number 09-0432)24,25. The major diffraction peaks observed at 2Ѳ values of approximately 25.9°, 31.8°, 32.2°, 32.9°, 39.8°, 46.7°, 49.5°, and 53.3° can be indexed to the (002), (211), (112), (300), (212), (004), (222), and (213) planes of the hexagonal HA crystal structure. The intense peak at 2Ѳ≈ 31.8°, corresponding to the (211) plane, indicates high crystallinity, a crucial factor for enhanced bioactivity and mechanical properties in biomedical applications. The high phase purity of the synthesized HA is confirmed by the absence of any additional peaks that would indicate other calcium phosphate phases, such as tricalcium phosphate (TCP) or calcium oxide26. Good crystallinity is indicated by the peaks’ comparatively narrow width, whereas nanoscale particle dimensions are indicated by their broadening at lower intensities. The Scherrer equation can be used to further calculate the particle size.

The produced material’s exceptional biocompatibility and suitability for biomedical applications, such as implant coatings and bone regeneration, are guaranteed by the phase purity. For load-bearing applications, high crystallinity helps the HA material’s mechanical strength and stability. The synthetic HA’s ability to support osteointegration and bioactivity in vivo is increased by its structural similarity to natural bone mineral. The use of eggshells as a calcium source probably introduces advantageous elements like magnesium and strontium, improving bone growth and biological performance, even though the XRD cannot directly identify trace elements.

FTIR analysis

The FTIR spectrum of HA NPs made from calcium precursors derived from eggshells is shown in Fig. 3. The successful synthesis of a phase-pure material is highlighted by the spectrum’s distinctive absorption bands, which validate the existence of functional groups linked to hydroxyapatite. Around 3570 cm⁻¹, a broad band is seen, which corresponds to the hydroxyl groups’ stretching vibration (v (O − H)). This validates the hydroxyl ion incorporation into the HA crystal lattice, a characteristic of the hydroxyapatite structure. The presence of the hydroxyl group in the material is further confirmed by another band around 630 cm⁻¹, which corresponds to the hydroxyl group’s librational mode (v (O − H⋅libration)). Strong and sharp bands in the range of 960–1100 cm⁻¹ are attributed to the stretching vibrations of the phosphate groups: The band at 962 cm⁻¹ represents the symmetric stretching vibration (v1 (PO43−)). The bands at 1035 cm⁻¹ and 1089 cm⁻¹ correspond to the asymmetric stretching vibrations (v3 (PO43−)). The presence of phosphate groups in the synthesized HA is further confirmed by bands near 560–600 cm⁻¹, specifically at 565 cm⁻¹ and 602 cm⁻¹, which are attributed to the bending vibrations (v4 (PO43−))27.

Weak bands that correspond to the asymmetric stretching vibrations (v3 (CO32−)) of carbonate ions are seen around 1400–1450 cm⁻¹. This indicates partial substitution of phosphate groups by carbonate, which is a common occurrence in biological hydroxyapatite and enhances bioactivity. A band near 870 cm⁻¹ represents the bending mode (v₂ (CO₃²⁻)) of carbonate ions.

A weak band at 1200–1250 cm⁻¹ can be attributed to the stretching vibrations (v (HPO₄²⁻)), indicating the presence of some dihydrogen phosphate species in the sample.

The formation of a calcium phosphate material with a hydroxyapatite structure is confirmed by the presence of hydroxyl, phosphate, and carbonate groups. The spectrum’s carbonate substitution indicates that the substance is more suited for biomedical applications because it resembles biological apatite. The phase purity of the synthesized hydroxyapatite is highlighted by the lack of notable bands that correspond to other calcium phosphate phases (such as tricalcium phosphate or calcium oxide). Since carbonate-substituted hydroxyapatite mimics the makeup of natural bone mineral and promotes cell attachment and proliferation in biomedical applications like bone tissue engineering, its incorporation suggests bioactivity27.

SEM and HRTEM investigation

The surface morphology, size, and distribution of the synthesized HA NPs are crucially revealed by the SEM image and particle size distribution graph shown in Fig. 4a and b. The synthesized HA nanoparticles have a spherical, slightly agglomerated structure and a comparatively uniform morphology, according to the SEM image. The magnification scale bar (100 nm) shows that the particles are well-defined and nanoscale in size. Because of the high surface energy and Van der Waals forces that promote particle aggregation, the agglomeration seen is common in nanomaterials. Because it increases surface area and bioactivity and facilitates better integration with biological tissues, this morphological feature is advantageous in biomedical applications, especially in bone regeneration28.

According to the particle size distribution histogram, which was produced by statistically analyzing the SEM image, the average size of the nanoparticles is 11.2 nm, as shown on the graph. The distribution exhibits a slightly skewed Gaussian curve, indicating that there are few outliers or larger aggregates and that the majority of particles fall within a small size range surrounding the mean. For many biomedical applications, the particles’ nanoscale size is essential because it guarantees a high surface-to-volume ratio, increased bioactivity, and better mechanical qualities.

The uniformity of the particle size distribution further proves the efficacy of the synthesis method employed. In HA-based applications, narrow size distributions help to ensure consistent characteristics like controlled ion release and predictable dissolution rates, which are vital for bone regeneration and healing. Uniformity and nanoscale size of the HA particles cause enhanced bioactivity and compatibility with bone tissue29,30. This makes the synthetic material perfect for bone grafts, dental uses, and orthopedic implants by improving osteointegration. The relatively uniform morphology and small particle size enable ease of processing into scaffolds, coatings, or composites for biomedical devices. The nanoparticles’ agglomeration tendency may aid in forming interconnected porous structures, further enhancing tissue ingrowth and nutrient exchange. The results confirm that the fabrication method effectively produces high-quality HA nanoparticles with desirable morphological and size characteristics, aligning with the requirements for regenerative medicine. The EDS analysis (Fig. 4c) shows that calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), and oxygen (O) are the main parts of the sample surface. The peaks at about 3.7 and 4.0 keV are for Ca, and the peaks at about 2.0 and 0.5 keV are for P and O, respectively. The atomic percentages we found are 48.68% Ca, 17.65% P, and 33.58% O. This gives us a Ca/P atomic ratio of about 2.76. This number is higher than the theoretical Ca/P ratio for stoichiometric hydroxyapatite (1.67), which means the material has a lot of calcium. Such a difference can happen if HA partially breaks down into CaO during synthesis, if other Ca-rich phases are added, or if phosphorus is lost more easily at high temperatures. The fact that there are only Ca, P, and O and no other elements that can be seen means.

The HRTEM image shown in Fig. 5 shows that the hydroxyapatite consists of an aggregation of nearly spherical to slightly irregular nanoparticles, with a noticeable degree of agglomeration. Using the 30 nm scale bar for reference, most particles appear to range between 10 and 30 nm in diameter. Variations in contrast between light and dark areas suggest the presence of overlapping crystalline domains and different particle orientations. The image also displays inter-particle voids and porosity, consistent with nanostructures produced through wet-chemical or precipitation synthesis methods. Many nanoparticles have well-defined edges, reflecting their crystalline nature31. While lattice fringes may be observed at higher magnifications, the primary features here are related to aggregation and morphology. Overall, these observations confirm the successful synthesis of nanostructured hydroxyapatite, with uniform particle size and shape well-suited for biomedical applications, drug delivery systems, and catalysis. The observed agglomeration is typical for nanomaterials due to their high surface energy, but the good uniformity of particle size indicates a controlled and homogeneous synthesis.

Biocompatibility of HA nanoparticles

The hemolytic effect of HA nanoparticles synthesized from eggshells was found to be concentration-dependent (Fig. 6). At a concentration of 12.5 mg/ml, minimal hemolysis was observed, demonstrating high biocompatibility and negligible disruption of RBC membranes. Increasing the concentration to 25 mg/ml resulted in a moderate rise in hemolysis, suggesting an enhanced interaction between nanoparticles and RBCs. Hemolysis significantly increased at the highest tested concentration of 50 mg/ml. This behavior could be explained by the higher density of the nanoparticles, which raises the possibility of interaction with RBC membranes and could result in chemical or mechanical disruption31,32.

Blood plasma reduced the hemolytic effects of HA nanoparticles at all tested concentrations. The formation of a protein corona around the nanoparticles, which probably lowers their direct interaction with RBC membranes, helps to explain this decline. This finding emphasizes the need for protein corona development in improving the biocompatibility of nanoparticles in physiological settings. The negative control, an RBC suspension in phosphate-buffered saline, showed no hemolysis, which confirmed the assay’s validity and the stability of RBCs in PBS. On the other hand, the positive control, which was RBCs in deionized water, produced total hemolysis as a benchmark for the maximum hemolytic activity31,33.

HA nanoparticles seemed to interact with RBC membranes only weakly at lower concentrations, therefore maintaining the structural integrity of the membranes. But as the concentration rose, the larger surface area of the nanoparticles probably enhanced their interaction with RBCs, causing structural instability and hemolysis. The protein corona’s shielding effect strengthens even more the idea that absorbed plasma proteins can lower the disruptive power of nanoparticles and improve their compatibility with biological systems. The concentration-dependent hemolytic activity seen in this work underlines the need of HA nanoparticle dosage optimization for biomedical uses17,34. Additional proof of the biocompatibility of HA nanoparticles in physiological settings is provided by the mitigating effect of the protein corona, which makes them attractive options for uses like drug delivery systems and bone regeneration treatments.

The proportion of hemolysis in human red blood cells caused by hydroxyapatite nanoparticles derived from eggshells at varying concentrations The percentage of hemolysis seen in each of the five treatment groups—which include positive and negative controls and HA nanoparticles made from eggshells at concentrations of 12.5 mg/ml, 25 mg/ml, and 50 mg/ml is depicted in the graph. The standard deviation (S.D.) of the data is shown by error bars, while each bar shows the mean hemolysis percentage (y-axis). The negative control group exhibited minimal hemolysis of 2.34 ± 0.37%, while the 12.5 mg/ml and 25 mg/ml HA groups showed moderate hemolysis values of 6.59 ± 0.42% and 8.57 ± 0.65%, respectively. The 50 mg/ml HA group demonstrated increased hemolysis at 10.97 ± 0.78%, whereas the positive control group exhibited significantly higher hemolysis at 83.86 ± 2.88%. Statistical analysis was performed with N = 3 for each group.

Fluorescence intensity assay

The results shown in Fig. 7 provide visual and quantitative evidence of fluorescence intensity across three experimental groups, with a focus on the effect of HA nanoparticles synthesized from eggshells at a concentration of 25 mg/ml (group B), compared to the positive (group A) and negative (group C) controls.

In group A (positive control), both the bright-field and fluorescence images show substantial fluorescence within the cells, as indicated by the vivid green fluorescence in the right panel. This suggests that the positive control is effective in inducing fluorescence in the sample, possibly through the known interactions of the control substance with the fluorescent marker. The fluorescence intensity in group A is quantified at 6343 ± 75.11, indicating a high degree of marker uptake or activation, which confirms that the experimental conditions are suitable for fluorescence detection.

As can be seen from the fluorescence image, the fluorescence intensity in Group B (HA nanoparticles made from eggshells at a concentration of 25 mg/ml) is marginally lower than that in the positive control but still noticeably high. Comparable to the positive control, the corresponding quantitative fluorescence measurement displays 6166 ± 54.60, indicating that the HA nanoparticles are also successful in their interaction with the fluorescent marker. This result shows that the HA nanoparticles made from eggshells at this concentration (25 mg/ml) continue to exhibit a notable level of fluorescence, suggesting that they are effectively interacting with the fluorescent molecules or cells in a way that is comparable to the positive control.

Group C (negative control), on the other hand, exhibits very little fluorescence in either the fluorescence or the bright-field images. In stark contrast to the fluorescence levels observed in groups A and B, the fluorescence intensity is measured at 257.1 ± 26.40. This weak fluorescence signal, which acts as a baseline to differentiate between specific interactions and non-specific fluorescence, verifies that the negative control neither causes fluorescence nor promotes marker uptake.

Groups A (positive control) and B (HA nanoparticles) showed higher fluorescence intensity than group C (negative control), indicating that the fluorescence in the experimental groups is specific and due to the fluorescent marker’s interactions with the cells or nanoparticles rather than background fluorescence. The fluorescence intensity similarities between groups A and B indicate that the HA nanoparticles made from eggshells at a concentration of 25 mg/ml are as good at promoting fluorescence as the positive control. According to the results, HA nanoparticles made from eggshells have the potential to be useful agents in fluorescence-based applications because of their advantageous size, surface characteristics, or biocompatibility. Since the fluorescence intensity of group B is similar to that of the positive control, these nanoparticles could be applied to a number of biomedical applications where fluorescence markers are used for imaging or tracking. Additionally, by ensuring that any observed fluorescence is due to particular interactions rather than random background effects, the sharp contrast with group C highlights the validity of the experimental design35,36.

Fluorescence Imaging and measurement of human red blood cell fluorescence intensity in HA nanoparticles (25 mg/ml) and controls. Three experimental groups are shown in the figure using bright-field and fluorescence images: (A) positive control, (B) eggshell-derived HA nanoparticles at a concentration of 25 mg/ml, and (C) negative control. While the right panels display fluorescence images, which show different fluorescence intensities among the groups, the left panels display bright-field images. While Group C (negative control) shows a noticeably weaker fluorescence signal, Group A (positive control) and Group B (HA nanoparticles) show high fluorescence intensity. With N = 10 for each group, the fluorescence intensity (y-axis) is quantified in the bar graph below as follows: 6343 ± 75.11 (A, positive control), 6166 ± 54.60 (B, HA nanoparticles at 25 mg/ml), and 257.1 ± 26.40 (C, negative control).

HA nanoparticles promote bone cell regeneration

The FE-SEM images shown here offer important information about how HA nanoparticles made from eggshells interact with MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells at a concentration of 25 µg/ml following a 24-hour culture period. The morphology and behavior of the cells after being exposed to this biomaterial are depicted in these high-resolution pictures. The general view of the cultured cells in Fig. 8A demonstrates how well the MC3T3-E1 cells have adhered to the HA nanoparticles. The visibility of the cells touching the nanoparticle surface suggests that the nanoparticles provide a suitable surface for cell adhesion. Understanding the HA nanoparticles’ osteoconductivity, which is crucial for their possible use in tissue engineering and bone regeneration, requires knowledge of this interaction.

Figure 8B shows a cluster of nanoparticles, marked by the red arrow that can be studied more closely. This enlarged perspective reveals the surface aggregation of the HA nanoparticles, a common feature of nanoparticle suspensions. These clusters could affect cell behaviour, maybe affecting their spread, differentiation, and proliferation. The fact that cells cling to these clusters of aggregated nanoparticles suggests, therefore, that the nanoparticles could encourage cell attachment instead of preventing it. Applications where promoting tissue growth depends on cell adhesion to the biomaterial make this particularly crucial. Typical cell attachment and spreading are seen in the MC3T3-E1 cell morphology, which helps to further support the bioactive character of the HA nanoparticles. This behavior shows promise for the application of these nanoparticles in bone tissue engineering, where successful implant integration and bone regeneration depend on efficient cell adhesion and material integration37.

FE-SEM images of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on eggshell-synthesized HA nanoparticles at 25 mg/ml for 24 h. The figure displays FE-SEM images of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured for 24 h on a substrate containing HA nanoparticles synthesized from eggshells at a concentration of 25 mg/ml. Panel (A) shows the general morphology of the cells adhering to the surface of the nanoparticles, with individual cells attached to the nanoparticles and the surrounding substrate. Panel (B) provides a magnified view of a cluster of nanoparticles (highlighted with a red arrow), illustrating the aggregation of nanoparticles and their interaction with the cultured cells. The image reveals that the cells have adhered to the nanoparticle surface, indicating the bioactivity of the HA nanoparticles in promoting cell attachment.

Antioxidant activity of HA nanoparticles

The scavenging activity of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles was evaluated across five experimental conditions, each representing different concentrations of HA nanoparticles and ascorbic acid as a positive control (Fig. 9). HA NPs at 25 µg/ml (A); this concentration of HA nanoparticles shows the lowest scavenging activity at approximately 14.76%. This indicates that at lower concentrations, HA nanoparticles have a limited effect on scavenging free radicals, potentially due to insufficient interaction between the nanoparticles and the free radicals at this concentration. HA nanoparticles at 50 µg/ml (B): An increase in scavenging activity to around 30.84% was observed, suggesting that higher concentrations of HA nanoparticles lead to a modest enhancement in free radical scavenging. This result aligns with expectations that increasing the dose would provide more active sites for scavenging. HA nanoparticles at 100 µg/ml (C): At this concentration, the scavenging activity rises significantly to approximately 65.90%. This suggests a clear dose-dependent response, where HA nanoparticles begin to show more pronounced antioxidant activity, likely due to greater nanoparticle availability and reactivity. HA nanoparticles at 200 µg/ml (D): Scavenging activity further increases to about 84.7%, showing a strong effect at higher nanoparticle concentrations. This reinforces the idea that increasing HA nanoparticles concentration improves their ability to neutralize free radicals, possibly because of a greater surface area and more reactive sites available, Ascorbic acid (E): The positive control, Ascorbic acid, demonstrates the highest scavenging activity at 92.08%, validating the effectiveness of this known antioxidant. This result also serves to compare the scavenging potential of HA nanoparticles with an established antioxidant agent38.

Scavenging activity of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (HA NPs). The bar graph shows the scavenging activity (%) of different concentrations of HA NPs and ascorbic acid (positive control). A: HA NPs at 25 µg/ml, B: HA NPs at 50 µg/ml, C: HA NPs at 100 µg/ml, D: HA NPs at 200 µg/ml, and E: Ascorbic acid (positive control). Data presented as mean ± standard deviation (N = 3).

Anti-Inflammatory effect of HA nanoparticles

The data presented in Fig. 10 illustrate the impact of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles on the IL-1β secretion levels in BMDMs (Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages) under different treatment conditions.

Control (A): The control group (untreated BMDMs) shows a very low baseline level of IL-1β, with a value of 2.583 pg/ml, which reflects the natural secretion of this cytokine in the absence of inflammatory stimuli. LPS + ATP Treatment (B): Treatment with LPS and ATP (known inflammasome activators) significantly increases the IL-1β secretion to 226.1 pg/ml. This sharp increase is consistent with the expected inflammatory response induced by these stimuli, triggering the activation of the inflammasome and promoting IL-1β release. HA NPs at 6.25 µg/ml (C): Treatment with HA NPs at a concentration of 6.25 µg/ml reduces the IL-1β secretion to 125.9 pg/ml, suggesting that HA NPs can partially mitigate the inflammatory response. While still elevated compared to the control, this reduction shows a dose-dependent response to HA NPs in modulating IL-1β production.

HA NPs at 12.5 µg/ml (D): At a higher concentration of 12.5 µg/ml, IL-1β levels decrease further to 104.0 pg/ml, indicating a more potent anti-inflammatory effect of HA NPs. This dose appears to have a more pronounced ability to suppress IL-1β secretion in LPS and ATP-treated BMDMs. HA NPs at 25 µg/ml (E): The highest concentration of HA NPs (25 µg/ml) leads to the most significant reduction in IL-1β levels, dropping to 70.87 pg/ml. This result indicates a strong anti-inflammatory effect at higher concentrations, suggesting that HA NPs may be effective in reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion in inflammatory conditions. The statistical significance (denoted by asterisks) confirms that the differences in IL-1β levels between the LPS + ATP group (B) and the HA NPs treatments (C, D, E) are significant, demonstrating the potential of HA NPs to modulate inflammation in macrophages.

Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (HA NPs) reduced the levels of IL-1β in BMDMs. The following conditions were used to treat BMDMs: (A) Untreated control BMDMs, (B) LPS + ATP-treated BMDMs, (C) LPS + ATP + HA NPs-treated BMDMs at 6.25 µg/ml, (D) LPS + ATP + HA NPs-treated BMDMs at 12.5 µg/ml, and (E) BMDMs-treated LPS + ATP + HA NPs at 25 µg/ml. The findings indicate that BMDMs treated with HA NPs had a dose-dependent decrease in IL-1β secretion, with the greatest reduction in IL-1β levels occurring at the highest concentration of HA NPs (25 µg/ml). Upper chart represented the experimental results after 7 h. While, lower chart represented the experimental results after 24 h. Asterisks denote statistical significance (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

The results in Fig. 11 demonstrate that HA NPs significantly change the production of IL-18 when bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) are stimulated with LPS and ATP. The low IL-18 levels (2.248 pg/ml) in the control group, which was not stimulated, validated the baseline inflammatory state. In contrast, LPS + ATP stimulation markedly increased the production of IL-18 to 195.7 pg/ml, indicating a strong inflammatory response. Remarkably, HA NPs reduced IL-18 levels in a dose-dependent manner. When compared to the LPS + ATP group, HA NPs reduced IL-18 to 140.4 pg/ml at the lowest concentration, with a statistically significant difference (*). There was a clear dose-response relationship because the highest concentration resulted in the most pronounced decrease in IL-18 levels (85.7 pg/ml, ***), while a mid-range concentration further decreased IL-18 levels to 113.5 pg/ml (**). These findings suggest that HA NPs have a potent anti-inflammatory effect by lowering IL-18 secretion in activated macrophages. The ability of HA NPs to alter the immune response highlights their potential as therapeutic agents for inflammatory conditions where IL-18 is essential. Further research is needed to identify the molecular mechanisms through which HA NPs regulate IL-18 production and assess their efficacy in inflammatory disease models in vivo39,40,41.

Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (HA NPs) reduce IL-18 levels in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) stimulated by LPS + ATP. (A) Control BMDMs without treatment (2.248 pg/ml). (B) LPS + ATP treatment of BMDMs (195.7 pg/ml). (C) BMDMs treated with 6.25 µg/ml (140.4 pg/ml) of LPS + ATP + HA NPs. (D) LPS + ATP + HA NPs were administered to BMDMs at a concentration of 12.5 µg/ml (113.5 pg/ml). (E) BMDMs treated with 25 µg/ml (85.70 pg/ml) of LPS + ATP + HA NPs. Asterisks denote statistical significance. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. Upper chart represented the experimental results after 7 h. While, lower chart represented the experimental results after 24 h.

Conclusion

By effectively creating hydroxyapatite (HA) nanoparticles from eggshell waste, this study offers a scalable and environmentally beneficial method for biomedical applications. The nanoparticles’ high crystallinity, phase purity, and nanoscale morphology (~ 11.2 nm), which resembles natural bone mineral, were confirmed by structural characterization (XRD, FTIR, and SEM). In addition to encouraging osteoblast (MC3T3-E1) adhesion and proliferation, which are critical for bone regeneration, the HA showed outstanding biocompatibility. Protein corona formation further improved biocompatibility, and concentration-dependent effects were found in hemocompatibility tests, with the highest level of safety occurring at ≤ 12.5 mg/ml. The nanoparticles demonstrated multifunctional bioactivity, including antioxidant and free radical scavenging effects that are dose-dependent (up to 84.7% at 200 µg/ml). The nanoparticles also demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects; induced macrophages’ significant suppression of IL-1β and IL-18 suggests immunomodulatory potential. Potential applications in drug delivery and bioimaging were made possible by fluorescence capability. These results establish HA derived from eggshells as a flexible biomaterial for anti-inflammatory and bone tissue engineering applications. To improve clinical translation, future studies should investigate functionalization, optimize dosages, and confirm effectiveness in in vivo models.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Mondal, S. et al. Hydroxyapatite: a journey from biomaterials to advanced functional materials. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., 103013. (2023).

Coelho, T. M. et al. Characterization of natural nanostructured hydroxyapatite obtained from the bones of Brazilian river fish. J. Appl. Phy. 100, 094312 (2016).

Damiri, F. et al. C., Nano-hydroxyapatite (nHAp) scaffolds for bone regeneration: preparation, characterization and biological applications. J drug delivery sci technol. 2024; 95: 105601. (2024).

Wu, S. C. et al. A hydrothermal synthesis of eggshell and fruit waste extract to produce nanosized hydroxyapatite. Ceram. Int. 39 (7), 8183–8188 (2013).

Sabir, A., Abbas, H., Aminy, A. Y. & Asmal, S. (Analysis of Duck eggshells as hydroxyapatite with heat treatment method.) EUREKA: Phys. Eng., (16–24 .). (2022).

HudaJabbarAbdulhussein, Promphet, N., Ummartyotin, S. & Ngeontae EnasMuhiHadi,EvanTSalim, AhmadSAzzahrani and Subash CBGopinath, Investigation and estimation of structural and dielectric properties of chromium-doped cobalt ferrites nanoparticles. Mater.Res.Express 11,115002. (2024).

Alhussary, B. N., Taqa, A., Taqa, A. A. A. & G., & Preparation and characterization of natural nano hydroxyapatite from eggshell and seashell and its effect on bone healing. J. Appl. Veterinary Sci. 5 (2), 25–32 (2020).

Peng, H., Wang, J., Lv, S., Wen, J. & Chen, J. F. Synthesis and characterization of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles prepared by a high-gravity precipitation method. Ceram. Int. 41 (10), 14340–14349 (2015).

Ruffini, A., Sprio, S., Preti, L. & Tampieri, A. Synthesis of Nanostructured Hydroxyapatite Via Controlled Hydrothermal Route10 (Biomaterial-supported Tissue Reconstruction or Regeneration, 2019).

HudaJabbarAbdulhussein, E. M. H., Promphet, N., Ummartyotin, S. & Ngeontae EvanTSalim, AhmadSAzzahrani and Subash CBGopinath, Investigation and estimation of structural and dielectric properties of chromium-doped cobalt ferrites nanoparticles. Mater.Res.Express 11,115002. (2024).

Chen, X., Li, H., Ma, Y. & Jiang, Y. Calcium phosphate-based nanomaterials: preparation, multifunction, and application for bone tissue engineering. Molecules 28 (12), 4790 (2023).

Ismail, R. A., Salim, E. T. & Hamoudi, W. K. Characterization of nanostructured hydroxyapatite prepared by nd: YAG laser deposition. Mater. Sci. Engineering: C. 33 (1), 47–52 (2013).

OBADA, D. O., Kuta, A. L. I. Y. U. A., Lisiyas, U. M., Ogenyi, A. & V. F., Aquatar, M. O., & ADAM, I Trends in the development of hydroxyapatite from natural sources for biomedical applications. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 257, 199–210 (2022).

Oladele, I. O. et al. Eggshell bio-derived hydroxyapatite particle-wool/polyester staple fibers hybrid reinforced epoxy bio-composites for biomedical services. Hybrid. Adv. 7, 100312 (2024).

Muthu, D. et al. Rapid synthesis of eggshell derived hydroxyapatite with nanoscale characteristics for biomedical applications. Ceram. Int. 48 (1), 1326–1339 (2022).

Huda, J., Enas, M. & Tahseen, H. Preparing and investigating the structural properties of porous ceramic Nano-Ferrite composites. J. Appl. Sci. Nanatechnol. 6 (3), 34–41 (2023).

Mohsin, M. H. et al. A novel facile synthesis of metal nitride@ metal oxide (BN/Gd2O3) nanocomposite and their antibacterial and anticancer activities. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 22749 (2023).

Ismail, R. A., Hamoudi, W. K. & Abbas, H. F. Electrophoretic deposition of hydroxyapatite-shrimp crusts nanocomposite thin films for bone implant studies. IET Nanobiotechnol. 12 (6), 714–721 (2018).

Pourmadadi, M. et al. Harnessing Bio-Waste for biomedical applications: A new horizon in sustainable healthcare. European J. Med. Chem. Reports, 100234. (2024).

Selvam, S. P., Ayyappan, S., Jamir, S. I., Sellappan, L. K. & Manoharan, S. Recent advancements of hydroxyapatite and polyethylene glycol (PEG) composites for tissue engineering applications–A comprehensive review. Eur. Polymer J. 215, 113226 (2024).

Roudana, M. A. et al. Thermal phase stability and properties of hydroxyapatite derived from bio-waste eggshells. J. Ceramic Process. Res. 18 (1), 69–72 (2017).

Abbas, Z. S. et al. Galangin/β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex as a drug-delivery system for improved solubility and biocompatibility in breast cancer treatment. Molecules 27 (14), 4521 (2022).

Nocchetti, M., Piccinini, M., Pietrella, D., Antognelli, C., Ricci, M., Di Michele,A., … Ambrogi, V. (2025). The Effect of Surface Functionalization of Magnesium Alloy on Degradability, Bioactivity, Cytotoxicity, and Antibiofilm Activity. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 16(1), 22.

Ghorai, S. K. et al. A judicious approach of exploiting polyurethane-urea based electrospun nanofibrous scaffold for stimulated bone tissue regeneration through functionally nobbled nanohydroxyapatite. Chem. Eng. J. 429, 132179 (2022).

Sundarabharathi, L., Ponnamma, D., Parangusan, H., Chinnaswamy, M. & Al-Maadeed, M. A. A. Effect of anions on the structural, morphological and dielectric properties of hydrothermally synthesized hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1–13 (2020).

Sakka, S., Bouaziz, J. & Ayed, F. B. Mechanical properties of biomaterials based on calcium phosphates and bioinert oxides for applications in biomedicine. Adv. Biomaterials Sci. Biomedical Appl., 23–50. (2013).

Mujahid, M., Sarfraz, S. & Amin, S. On the formation of hydroxyapatite nano crystals prepared using cationic surfactant. Mater. Res. 18 (3), 468–472 (2015).

Hosseini, B., Mirhadi, S. M., Mehrazin, M., Yazdanian, M. & Motamedi, M. R. K. Synthesis of nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite using eggshell and trimethyl phosphate. Trauma. Monthly. 22 (5), 6 (2017).

Zhou, X., Sun, J., Wo, K., Wei, H., Lei, H., Zhang, J., … Chen, L. (2022). nHA-loaded gelatin/alginate hydrogel with combined physical and bioactive features for maxillofacial bone repair. Carbohydrate Polymers, 298, 120127.

Mysore, T. H. M. et al. Apatite insights: from synthesis to biomedical applications. Eur. Polymer J., 112842. (2024).

Hassan, M. A., Mohsin, M. H. & Ismail, R. A. Preparation of high-responsivity strontium–doped cuo/si heterojunction photodetector by spray pyrolysis. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 34 (10), 912 (2023).

Han, Y., Wang, X., Dai, H. & Li, S. Nanosize and surface charge effects of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles on red blood cell suspensions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 4 (9), 4616–4622 (2012).

Ayub, M. et al. Eggshell-Mediated hematite nanoparticles: synthesis and their biomedical, mineralization, and biodegradation applications. Crystals 13 (12), 1699 (2023).

Sun, W. et al. Exploring the effect of hydroxyapatite nanoparticle shape on red blood cells and blood coagulation. Nanomedicine 19 (27), 2301–2314 (2024).

Al-Azawi, K. F., Hasoon, B. A., Ismail, R. A., Rasool, K. H., Jabir, M. S., Shaker,S. S., … Swelum, A. A. (2025). Pharmaceutical properties of novel 3-((diisopropylamino)methyl)-5-(4-((4-(dimethylamino) benzylidene) imino) phenyl)-1, 3, 4-oxadiazole-2(3 H)-thione. Scientific Reports, 15 (1), 15019.

Gouveia, M. E. T., Milhans, C., Gezek, M. & Camci-Unal, G. Eggshell-Based Unconventional Biomaterials for Medical Applications. (2024).

Wu, F. et al. Effect of the materials properties of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles on fibronectin deposition and conformation. Cryst. Growth. Des. 15 (5), 2452–2460 (2015).

Xiong, L., Wang, P., Hunter, M. N. & Kopittke, P. Bioavailability and movement of phosphorus applied as hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (HA-NPs) in soils. Environ. Sci. Nano. 5, 2888–2898 (2018).

Hamidivadigh, F. & Javadpour, J. The synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles using eggshells and two different phosphate sources. Eur. J. Eng. Technol. Res. 9 (2), 1–4 (2024).

Grandjean-Laquerriere, A., Laquerriere, P., Laurent-Maquin, D., Guenounou, M. & Phillips, T. M. The effect of the physical characteristics of hydroxyapatite particles on human monocytes IL-18 production in vitro. Biomaterials 25 (28), 5921–5927 (2004).

Lebre, F. et al. The shape and size of hydroxyapatite particles dictate inflammatory responses following implantation. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 2922 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors are appreciation the University of Technology- Iraq for their support.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2502).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mayyadah, Majid, and Huda writing Original draft, methodology, investigation, and Formal analysis. Mayyadah H. Mohsin, Huda J. Abdulhussein, Ghassan, and Majid : Main Concept, data interpretation, and supervision. Raid, Asmiet, Eisa, Nasir, and Nosiba: Writing review and editing, visualization, and Data curation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdulhussein, H.J., Mohsin, M.H., Jabir, M.S. et al. Eco-friendly synthesis of eggshell-derived nano-hydroxyapatite: physicochemical characterization, hemocompatibility, and bone regeneration potential. Sci Rep 15, 32832 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17486-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17486-0