Abstract

This study investigates the differential effects of extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from bovine follicular fluid (FF) on bovine oocytes cryotolerance, focusing on EVs from small (3–5 mm) and large (> 9 mm) follicles, with the aim of optimizing vitrification protocols. FF-EVs were isolated and characterized for size and concentration. Oocytes were in vitro matured with FF-EVs prior to vitrification. Post-warming assessment included spindle morphology, DNA integrity, embryo development, total cell count, and apoptotic index of resulting blastocysts. EVs uptake by cumulus-oocyte complexes was confirmed via confocal microscopy. While percentages of oocytes at the metaphase II stage were similar across groups, vitrification significantly reduced normal spindle configurations, except in oocytes supplemented with large FF-EVs (VIT Large), which resembled fresh oocytes. DNA fragmentation was significantly lower in the VIT Large group, whereas vitrification alone increased fragmentation. Blastocyst, expansion and hatching rates were higher in VIT Large, which also preserved inner cell mass quality similar to fresh counterparts. These findings suggest that FF-EVs from large follicles mitigate vitrification-induced damage, improving oocyte cryopreservation outcomes and embryo quality. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that FF-EVs can improve the cryotolerance of bovine oocytes, establishing a novel approach for enhancing oocyte vitrification outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Female gametes preservation is crucial for advancing reproductive biology, animal breeding, and conservation efforts. Among cryopreservation methods, oocyte vitrification has emerged as a pivotal technique in germplasm preservation and assisted reproductive technologies. It enables efficient storage and utilization of female gametes. This facilitates applications in fertilization and the provision of cytoplasts for nuclear transfer in somatic cell reprogramming. However, the outcomes of oocyte vitrification remain suboptimal due to cryoinjury-induced damage. Vitrified oocytes exhibit reduced survival rates, and the production of viable bovine embryos from vitrified oocytes is still lower compared to fresh oocytes1,2,3.

Oocyte vitrification have been reported to induce cryoinjury alterations at various levels including prematurely release of intracellular Ca+2, chromosome abnormality, disruption of microtubules and actin microfilaments or oxidative stress that leads to mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum damage1. To overcome this issues many approaches have been explored. These include optimizing cryoprotectant solutions4mathematical modeling to reduce cryoprotectants (CPA) toxicity5, lipid modulation to, reduce lipid content6the use of microtubules stabilizers to prevent microtubule depolymerization7,8 and the use of antioxidant treatments to mitigate oxidative stress during the vitrification process9,10. Despite the advancements in oocyte vitrification, these approaches have shown only partial success. Although they improve certain aspects of vitrification outcomes by mitigating specific cryoinjury effects, they fail to make vitrified oocytes fully comparable to fresh counterparts (reviewed in1,3. Therefore, there is a need for new strategies capable of acting at multiple levels to improve oocyte survival and developmental potential of vitrified/warmed oocytes.

Over the past few years, extracellular vesicles (EVs) have gained attention as a novel tool to improve the outcomes of assisted reproduction techniques11,12,13. EVs are lipid bilayer-enclosed particles released from cells that cannot replicate14. Which play a critical role in intercellular communication by transporting bioactive molecules as metabolites, proteins and nucleic acids15. Additionally, EVs can exert a bystander effect by mediating the transfer of stress-adaptive molecules, enabling cells to withstand adverse conditions16,17,18.

Follicular fluid-derived EVs (FF-EVs) have been isolated in several species, including equine19,20,21, bovine17,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, porcine32,33, human34,35, caprine36, buffalo37 and feline38. The addition of FF-EVs to the in vitro maturation (IVM) media has shown promising results in equine, improving maturation rates in compacted cumulus-oocytes complexes (COCs)19, inducing cumulus cell expansion20 and increasing fertilization rates following intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)21. Similarly, in the bovine species, FF-EVs supplementation during IVM resulted in increased cumulus expansion17,20,23, higher cleavage and blastocysts rates17,25 and better-quality blastocysts39. However, little is known about the effect of FF-EVs on oocyte cryotolerance. In the domestic cat, immature COCs briefly co-incubated with FF-EVs prior to vitrification and/or vitrified/warmed in the presence of FF-EVs showed improved meiotic resumption of vitrified oocytes38. Nevertheless, it remains unknown whether FF-EVs can protect oocytes from other species against vitrification induced cryoinjury, either at immature or mature stages.

Furthermore, the cargo of these EVs varies significantly depending on various factors, such as oocyte growth status22, metabolic status27,29, estrous cycle stage28,31, season30,37 and follicular size24,25,36. Regarding follicular size, several studies have shown that microRNAs (miRNAs) in FF-EVs derived from follicles of different sizes exhibit different expression profiles24,36. In the bovine species, pathway analysis revealed that small follicles derived FF-EVs contain miRNAs predicted to influence cellular development and proliferation, cell death and survival and cell cycle regulation pathways, while FF-EVs derived from large follicles contain miRNAs predicted to influence inflammatory responses pathways24. Functional studies in cattle have reported that FF-EVs from small follicles resulted in greater cumulus expansion23, enhanced granulosa cell proliferation26 and higher blastocyst rates25. In contrast, FF-EVs from large follicles demonstrate comparatively moderate effects, inducing limited cumulus expansion23 and granulosa cell proliferation26. Furthermore, FF-EVs from preovulatory follicles failed to increase blastocyst rates25. However, all these studies have been conducted under non-stress or optimal conditions. To date, no research has directly compared if FF-EVs from various follicular sizes can mitigate or overcome cellular damage caused by stressors such as those encountered during oocyte vitrification. While FF-EVs from small follicles have consistently demonstrated superior functional outcomes under optimal conditions, the potential role of the distinct molecular cargo present in large follicle-derived EVs remains unexplored under adverse or suboptimal conditions and may contribute to protective or adaptive responses. A better understanding of this could help elucidate the role of follicular fluid from different follicle sizes in oocyte cryoprotection and to determine whether FF-EVs can be used as a medium supplement to improve oocyte survival and developmental competence after vitrification.

Herein, the aim of this study was to evaluate, for the first time, the impact of adding FF-EVs from small or large follicles to the IVM medium on the cryotolerance of bovine oocytes. With that purpose, EVs were isolated from FF of small (3–5 mm) and large (> 9 mm) follicles using size exclusion chromatography (SEC). Then, EVs were characterized, and their uptake by COCs was confirmed. Bovine COCs were then matured in medium supplemented with EVs derived from either small or large follicles. After 21 h of maturation, oocytes were vitrified and warmed. The impact of EVs supplementation on vitrified/warmed oocytes was assessed by analyzing oocyte spindle morphology, oocyte DNA fragmentation, embryo developmental rates, blastocysts cell count and apoptosis.

Results

Characterization of FF-EVs from large and small follicles

Vesicle size and concentration were assessed using nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA). Small-EVs showed a significantly higher concentration with significantly smaller size compared to Large-EVs (Table 1). The size and morphology of EVs were further characterized by cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM), revealing their characteristic spherical shape and lipid bilayer structure (Fig. 1).

Flow cytometry analyses confirmed the presence of functional and intact membrane EVs in both Small-EVs and Large-EVs. Specifically, 84.5 ± 0.03% and 86.0 ± 0.02% of EVs were CFSE-positive in Small-EVs and Large-EVs, respectively. Additionally, the tetraspanins CD81, CD9, and CD63 were detected in Small-EVs, with EVs populations (%) of CD81 (12.3 ± 0.03), CD9 (8.6 ± 0.01), and CD63 (41.0 ± 0.06), and their respective signal intensities (Arbitrary Units, AU): CD81 (1,584.8 ± 16.1), CD9 (1,088.4 ± 8.5), and CD63 (1,584.8 ± 20.2). Similarly, in Large-EVs, the percentage of EVs displaying positive immunoreactivity was 12.0 ± 0.03% for CD81, 9.0 ± 0.02% for CD9, and 39.0 ± 0.08% for CD63, with corresponding signal intensities (AU) of CD81 (1,605.2 ± 25.5), CD9 (1098.6 ± 23.3), and CD63 (1,144.6 ± 37.4). These findings further validate the effectiveness of the isolation protocol.

FF-EVs uptake by COCs

The ability of EVs to be internalized and mediate an effect on COCs was validated by their uptake. Following 9 h and 21 h of co-incubation with labeled EVs, FF-EVs positive signal was confirmed within the transzonal projections, perivitelline space and in the cumulus cells (CCs) surrounding the oocyte by confocal laser-scanning microscopy as shown in Fig. 2.

Confocal images of COCs and oocytes co-incubated with PKH26 labeled EVs for 9 and 21 h during IVM (A) Negative control COCs showed no fluorescence signal in either the CCs or the oocyte. (B) After 9 h of co-incubation, labeled EVs were detected in the transzonal projections and the perivitelline space. Labeled EVs were also present in the CCs (data not shown). (C) After 21 h of co-incubation, labeled EVs were observed in the surrounding CCs. Scale bar: 30 μm. BF: Bright Field; PKH26: EVs labeled with PKH26.

Spindle configurations in IVM bovine oocytes vitrified/warmed after IVM with or without FF-EVs from small or large follicles

Results on the impact of IVM medium supplementation with FF-EVs of small or large follicles on spindle configuration are summarized in Table 2. No differences were observed in percentages of oocytes reaching the metaphase II (MII) stage among the experimental groups. Percentages of vitrified oocytes exhibiting a normal MII spindle were significantly lower than those observed in fresh non-vitrified oocytes, except for the group VIT Large that showed similar percentages than non-vitrified groups.

Analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in the percentages of oocytes showing dispersed microtubules or chromosomes across experimental groups (P > 0.05). Percentages of microtubule and chromosome decondensation remained similar within fresh or vitrified groups, though oocytes supplemented with Small-EVs prior to vitrification displayed the highest percentage of decondensed microtubules. Additionally, the addition of EVs from both small and large follicles to the IVM medium in vitrified oocytes reduced the percentages of absent microtubules to levels comparable to those in the non-vitrified groups.

Percentages of TUNEL-positive oocytes observed in IVM bovine oocytes vitrified/warmed after IVM with or without FF-EVs from small or large follicles

As shown in Fig. 3, supplementation with FF-EVs from large follicles during IVM prior to vitrification significantly reduced the percentage of oocytes with fragmented DNA compared to the other vitrified groups. Moreover, the VIT Large group exhibited DNA fragmentation levels similar to those of fresh non-vitrified groups. In contrast, a significant increase in the percentage of TUNEL + oocytes was observed in the VIT group compared to the non-vitrified groups. Additionally, VIT Small oocytes showed significantly higher percentages of DNA fragmentation compared to Control and Small groups.

TUNEL detection of fragmented oocyte DNA. (A) Effects of EV supplementation during IVM on bovine oocytes on percentages of TUNEL-positive oocytes. Percentages of TUNEL-positive oocytes were quantified manually. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. a, b,c Values with different letters differ significantly (P < 0.05). Treatment groups: Control (n = 36): oocytes in vitro matured in standard IVM medium; Small (n = 33): oocytes in vitro matured in IVM medium supplemented with EVs from small follicles; Large (n = 42): oocytes in vitro matured in IVM medium supplemented with EVs from large follicles; VIT (n = 31), VIT Small (n = 53), and VIT Large (n = 28) underwent identical IVM conditions as their non-vitrified counterparts but were vitrified/warmed at 21 h of IVM and allowed to recover for 3 additional hours post-warming; (B) Representative images of IVM bovine oocytes stained with TUNEL (i1,i2); green) and DAPI ((ii1,ii2); blue). (i1,ii1): TUNEL-positive oocyte indicating DNA fragmentation; (i2,ii2): TUNEL-negative oocyte indicating absence of DNA fragmentation. Merge images are shown in (iii1,iii2). Scale bar: 10 μm.

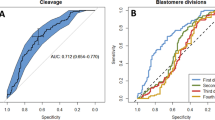

Embryo development in IVM bovine oocytes vitrified/warmed after IVM with or without FF-EVs from small or large follicles

Table 3 compares the effects of IVM of bovine oocytes with EVs derived from FF of small or large follicles prior to vitrification at the MII stage on early in vitro embryo development. No significant differences were found between groups in cleavage rates. However, on Days 7 and 8 pi, both vitrification alone and vitrification following supplementation with small follicle-derived EVs resulted in significantly lower blastocyst rates than their fresh counterparts. In contrast, oocytes vitrified after IVM with EVs from large follicles yielded blastocyst rates similar to those of fresh controls.

When D8 embryos were classified as non-expanded, expanded and hatched blastocysts, percentages of non-expanded blastocysts did not differ significantly among treatment groups. However, the VIT and Small VIT groups exhibited significantly lower expansion and hatching rates compared to fresh controls, whereas Large VIT maintained rates similar to fresh counterparts.

Differential cell count and apoptosis of blastocysts derived from vitrified/warmed IVM bovine oocytes after EV supplementation during maturation

Table 4 summarizes total cell number (TCN), inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE) cell number, as well as apoptotic rates (AR) recorded in D8 blastocysts derived from oocytes matured with or without FF-EVs prior to vitrification. Representative images of differential cell staining of blastocysts are displayed in Fig. 4. TCN showed no differences among treatment groups. While ICM numbers were significantly reduced in vitrified groups compared to fresh groups, VIT Large preserved ICM numbers better than other vitrified groups (35.1 ± 4.0), approaching values seen in fresh non-vitrified groups. The TE cell numbers varied across the experimental groups, with the highest values observed in the Large group (109.4 ± 22.6) and the lowest in the VIT Small group (57.6 ± 6). No statistically significant differences were found between the vitrified groups, nor when compared to their fresh counterparts. No significant differences in apoptotic rates were observed among any of the experimental groups.

Representative images of D8 blastocysts derived from oocytes IVM with the presence or absence of EVs derived from small or large follicles. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI are displayed in blue (A), ICM stained with anti-SOX2 antibody is displayed in red (B) and Caspase-positive cells stained with anti-active caspase-3 antibody are displayed in green (C). An overlay is provided in (D). Scale bar: 48 μm.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated, for the first time, the effects of FF-EVs on the vitrification outcomes and cryotolerance of bovine oocytes. Our findings demonstrate that EVs supplementation during in vitro maturation prior to vitrification/warming modulates key cellular and developmental parameters, including spindle morphology, chromosomal organization, DNA integrity, and both embryo development and quality.

NTA results showed that EVs derived from small follicles exhibited a higher particle concentration per mL compared to those from large follicles, consistent with previous studies24,26. In contrast, the distinct size profiles observed between small and large follicle-derived EVs in our study differ from those reported in other studies, as similar analysis found no significant differences in EVs size between groups23,24,26. These differences may be due to the EV isolation methods employed, which are known to influence the size distribution of EVs populations40.

The ability of CCs and oocytes to internalize FF-EVs was confirmed by their presence after co-incubation within CCs, transzonal projections and the perivitelline space. Similar uptake patterns have been reported in studies involving FF-EVs in bovine oocytes in vitro maturation, where fluorescently labeled EVs were within CCs and their transzonal projections after 9 h of exposure25. In the referenced study, vesicle uptake was associated with partial modulation of genes related to metabolism and development, as well as changes in miRNA expression and global DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation. These findings confirm efficient vesicle internalization, either through granulosa cells or by direct passage across the zona pellucida into the perivitelline space, potentially transferring bioactive molecules to the oocyte41.

The absence of significant differences in spindle morphology, chromosomal organization, and DNA integrity suggests that EVs do not substantially influence oocyte maturation under our specific in vitro conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess spindle morphology after in vitro maturation with EVs in the bovine species. This finding aligns with recent research in bovine models, De Ávila et al.28 reported no differences in maturation rates in bovine oocytes supplemented with FF-EVs. Similarly, in feline species, no significant effects of FF-EVs on the in vitro maturation of fresh cat oocytes have been reported38, although vitrified oocytes reached the MII stage only in FF-EVs treated groups. Interestingly, studies in porcine species have yielded mixed results. While Kang et al.42 found no effect on maturation rates, No et al.33 reported that EVs supplementation enhanced maturation rates only at specific concentrations, with no effect observed at lower or higher doses. In equine oocytes, the use of a two-stage maturation protocol for compact COCs resulted in a higher proportion of MII oocytes compared to both a single-step protocol and control oocytes19. These observations suggest that the effects of EVs on oocyte maturation may be species-specific and dependent on factors such as EVs concentration and culture conditions, which could explain the lack of significant effects observed in our study.

Vitrification is known to induce abnormal spindle configurations, chromosome misalignments and DNA fragmentation1. In the present study, vitrification impaired spindle morphology, compromised chromosomal stability and increased DNA fragmentation pot-warming. However, supplementation with EVs derived from large follicles preserved spindle integrity and reduced DNA fragmentation post-vitrification compared to both non-supplemented controls and oocytes treated with small follicle-derived EVs. EVs are known to carry bioactive molecules, including metabolites, proteins and nucleic acids15 which may enhance oocyte resilience against cryopreservation-induced stress. In the domestic cat, gene ontology (GO) terms for biological processes showed that enriched proteins in FF-EVs can play roles in the regulation of stress response, oxidative stress response and meiotic spindle organization38. Given that oxidative stress is a major contributor to vitrification-induced damage, the protective effects of EVs may be partially attributed to antioxidant properties. Similar protective effects have been reported with the use of antioxidant molecules prior to vitrification, such as glutathione ethyl ester (GSH-OEt)10 and microtubule-stabilizing agents like paclitaxel7 that alleviate spindle misalignments, as well as antioxidants like melatonin, which has been reported to reduce DNA fragmentation43. However, further studies are needed to determine whether EVs exert their protective effects through antioxidant mechanisms. Conversely, supplementation with EVs from small follicles was associated with higher rates of chromosomal decondensation following vitrification. Further research should be performed to elucidate whether specific components within these EVs might predispose oocytes to chromosomal instability.

The beneficial effects of large follicle-derived EVs on vitrified oocytes extended beyond maturation, positively influencing embryonic development. Oocytes supplemented with large follicle-derived EVs prior to vitrification exhibited blastocyst formation and hatching rates comparable to non-vitrified controls. This finding suggests that EVs-mediated protection during IVM translates into enhanced developmental potential. In contrast, EVs derived from small follicles did not confer similar benefits. Although cleavage rates did not differ significantly, blastocyst formation on D7 and D8 and expansion and hatching rates were significantly lower compared to non-vitrified controls. These results highlight a follicle size-dependent effect of EVs on oocyte developmental competence following vitrification. Previous studies have reported that FF-EVs provide protective effects against stress conditions in oocytes, resulting in blastocyst rates comparable to those of non-stressed oocytes. For instance, Rodrigues et al.17 demonstrated a reduced negative impact of heat shock treatment (41 °C for 14 h) during in vitro maturation when oocytes were treated with EVs derived from 2 to 8 mm follicles, achieving blastocysts rates comparable to control oocytes. Interestingly, in the present study, neither small nor large FF-EVs improved the developmental rates of non-vitrified oocytes. Although the differences were not statistically significant, blastocyst rates in EV-treated oocytes were lower than those in the control group in fresh conditions, with a more pronounced effect between the control and the Large group on D8. This trend toward a reduction in blastocyst rates has also been observed in studies using high concentrations of antioxidants44. Our findings diverge from previous reports where EVs from small and medium follicles enhanced blastocyst rates17,25. A potential reason for this inconsistency is the difference in EVs isolation methods. While our study employed SEC columns, the aforementioned studies used ultracentrifugation. This hypothesis is supported by Asaadi et al.39, who compared the effects of FF-EVs isolated via SEC and ultracentrifugation, finding a significant improvement in blastocyst rates only when EVs were isolated using ultracentrifugation. Additionally, conditions of EVs storage -including temperature, duration, and the composition of the storage buffer- can markedly influence their stability and biological activity, potentially contributing to the variability observed between studies45.

Differential staining of blastocysts provided further insights into embryo quality. EVs supplementation from large follicles prior to vitrification preserved cell numbers at levels comparable to fresh controls, maintaining embryo quality similar to non-vitrified oocytes. Conversely, oocytes treated with small follicle-derived EVs exhibited a reduction in ICM numbers in vitrified oocyte-derived blastocysts, suggesting a negative impact on embryo quality. In contrast, an increase in TCN, ICM, and TE was reported when oocytes were treated with FF-EVs in both SEC and ultracentrifugation groups39.

Differences found in this study likely reflect variations in the molecular cargo of EVs from small versus large follicles. Several studies have reported differential expression profiles between follicle size-derived EVs. For instance, in bovine and mouse species, EVs from small follicles significantly upregulated PTSG2, PTX3, and TNFAIP6 genes, promoting cumulus expansion, whereas EVs from large follicles failed to induce PTX3 and TNFAIP6 expression and reduced PTSG2 levels in COCs23. Similarly, in bovine, 25 miRNAs were differentially expressed between small and large follicular fluid-derived EVs, with small follicle EVs involved in cellular development, proliferation, and survival, while large follicle EVs were linked to inflammatory responses24. Granulosa cell proliferative activity was also found to be greater in response to EVs isolated from small follicles26. Additionally, treatment with EVs from small follicles increased the expression of the epigenetic modifier DNMT3A and upregulated genes associated with embryo development such as ASCL6, CDH1, REST, and FADS2, indicating a modulatory effect on transcription during oocyte maturation and embryo culture25. In goats36, identified 94 miRNAs differentially expressed in large versus small follicle-derived EVs. Small EVs targeted insulin signaling and progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation, while large EVs enriched the PI3K-AKT, MAPK, and FoxO pathways, which play key roles in granulosa cell proliferation, follicular growth26,46 and the regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis47,48.

Furthermore, the discrepancies observed between studies are likely influenced by differences in EVs isolation methods and variations in experimental conditions. However, differences in EVs content may also arise from multiple factors related to the animals from which the follicular fluid is derived. Beyond follicle size, several key factors have been identified as determinants of EVs composition as age49,50,51,52, estrous cycle phase28,31, metabolic status27,29, diseases34, and environmental factors30,37 among others.

Moreover, EVs derived from in vitro cultured bovine oviduct epithelial cells (BOECs) have proven to improve cryotolerance of bovine embryos by protecting the paracellular sealing and balancing the transcellular movement of H2O and ions across to the blastocoelic cavity helping the re-expansion of the blastocysts53. Additionally, studies on sperm cryopreservation reported that exposure to epididymal EVs enhances immature sperm function and sustains the vitality of cryopreserved spermatozoa in the domestic cat54. Similarly, cat and dog oviductal EVs improved post-thaw motility in the red wolf and prevented premature acrosome exocytosis in both red wolf and cheetah sperm when co-incubated during thawing55. In domestic species, exosomes isolated from seminal plasma and supplemented in extenders for sperm cryopreservation significantly improved bull sperm cryotolerance by supporting mitochondrial membrane potential and protecting the cytoplasmic membrane56. Similarly, in equine, the addition of mesenchymal stem cell-derived EVs to semen extenders enhanced semen cryopreservation outcomes, increasing sperm motility, progressive motility, and viability57.

Although our findings suggest a protective role of EVs against cryoinjury, further studies aimed at identifying and characterizing the molecular cargo of EVs, such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, are necessary to elucidate the mechanisms underlying their functional effects during oocyte vitrification.

Conclusions

This study provides the first evidence that FF-EVs can optimize oocyte vitrification outcomes, focusing on EVs from small (3–5 mm) versus large (> 9 mm) follicles. Results showed that EVs derived from the follicular fluid of large follicles significantly enhanced bovine oocyte cryotolerance by improving spindle morphology, reducing DNA fragmentation, and supporting embryo development to rates and quality comparable with non-vitrified oocytes. These findings elucidate novel insights into the role of EVs in reproductive cryobiology and present a promising approach to improving oocyte vitrification outcomes. Future research should explore the molecular mechanisms underlying the protective effects observed with FF-EVs, focusing on their bioactive cargo, such as proteins, RNAs, and lipids, and how these components interact with cellular pathways to enhance cryotolerance in oocytes.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and suppliers

Except where otherwise specified, all chemicals and reagents were supplied from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck, MA, USA).

Experimental design

Study 1. Isolation and characterization of FF-EVs. FF was collected from bovine antral follicles of different sizes (small: 3–5 mm; large: >9 mm)23 and processed for EVs isolation using SEC columns. The EVs were characterized by NTA, Cryo-EM, and flow cytometry (FC) to confirm their size, morphology, and marker expression.

Study 2. Uptake of EVs by COCs. To evaluate the uptake of EVs by COCs during IVM, EVs derived from large and small follicles were mixed, labeled with PKH26, and added to the IVM medium at a final concentration of 16 × 10⁹ particles/mL. A negative control was prepared by labeling Phosphate-Buffered Saline without calcium and magnesium (PBS−). Stained samples were co-incubated with COCs during IVM in 4 replicates of 10 COCs. After 9–21 h, oocytes were washed to remove non-internalized EVs and fixed. Confocal laser-scanning microscopy was used to confirm EVs uptake and assess their localization.

Study 3. Effects of EVs supplementation during IVM on bovine oocytes cryotolerance. COCs were matured in vitro under three conditions: (1) Control: no supplementation, (2) Small: supplementation of IVM medium with 16 × 10⁹ particles/mL of EVs derived from FF from small follicles, and (3) Large: supplementation of IVM medium with 16 × 10⁹ particles/mL of EVs derived from FF from large follicles. For each experimental group, half of the oocytes were vitrified (VIT) after 21 h of IVM followed by 3 additional hours of IVM after warming. Non-vitrified oocytes served as fresh controls. At the end of the IVM, all oocytes were evaluated for spindle morphology (4 replicates; 18–30 oocytes/replicate) using immunofluorescence and DNA integrity using TUNEL Kit (4 replicates; 7–14 oocytes/replicate). The EVs concentration used in this study was selected based on Rodrigues et al.17, where it effectively mitigated heat shock-induced effects in bovine oocyte developmental competence.

Study 4. Effects of EVs supplementation during IVM on the developmental potential of vitrified/warmed bovine oocytes. Oocytes IVM under the three experimental conditions (Control, Small, and Large) were subjected to in vitro fertilization (IVF). Both VIT and fresh oocytes were included in each group. Presumptive zygotes were cultured to the blastocyst stage in 25 µL droplets placed in 30 mm petri dishes, covered with 3.5 mL of mineral oil. Developmental outcomes were assessed by recording cleavage at 48 h post-insemination (pi) and developmental rates on Day 7 (D7) and 8 (D8) pi (4 replicates; 31–45 oocytes/replicate). Blastocyst quality was further evaluated through differential cell counts of the inner cell mass and trophectoderm, as well as apoptotic rates, using immunofluorescence markers (4 replicates; 2–4 blastocysts/replicate).

To confirm that the vehicle used for EVs did not influence the outcomes, a PBS − control group (consisting of 2.5% v/v PBS supplementation) was included. Data from these controls are provided in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4.

FF collection

Ovaries from cyclic females aged 12 to 24 months were collected from a local slaughterhouse and transported the laboratory in saline (0.9% w/v NaCl) maintained at 35–37 °C within 1 h. FF was aspirated from antral follicles measuring 3–5 mm in diameter (small) and > 9 mm in diameter (large)23 for EVs isolation, or 3–8 mm for oocyte collection, using an 18-gauge needle.

FF-EVs isolation

FF was collected from 10 animals per lot from nine different lots. FF from each lot was pooled, and 5 mL of each pooled sample was subsequently used for EVs isolation. Immediately after collection, FF was processed as previously described by Leal et al.58 with minor modifications. Briefly, FF was centrifuged at 300 x g for 7 min to remove cellular debris and other large particles. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 30 min at 4 °C to further remove debris and large vesicles. Following that, the supernatant was filtered with a 0.22-µm filter.

Then, the filtered supernatant was subsequently subjected to EVs isolation by Pure EVs SEC columns, according to manufacturer’s instructions (Hansa BioMed Life Sciences, Estonia; Cat. nº HBM-PEV-10). SEC columns were washed with 30mL PBS − and then FF samples were loaded onto the top of the SEC column. When the sample was completely within the column, 11 mL PBS − were loaded. After discarding the first 3 mL, the following 2.0 mL of EVs-rich fractions were collected.

To concentrate the EVs sample, 10 K molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) Pierce protein concentrators (ThermoFisher, MA, USA; Cat. nº 88527) were used. The sample was centrifuged four times at 2,000 x g for 15 min at 4 °C until a final volume of 200 µL was achieved. FF-EVs were preserved in PBS − at −20 °C. All experiments were performed in less that 3 months.

EVs characterization

Following the Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV) guidelines14, EVs from FF were characterized using NTA, cryo-EM, and Flow cytometry (FC). FC was performed as previously described by Barranco et al.59, while NTA and cryo-EM followed the methodology described by Cañón-Beltrán et al.60 with minor modifications.

NTA

Analysis of concentration and size distribution of EVs was performed using a NanoSight NS300 system equipped with a CMOS video camera and particle-tracking software NTA 3.4 Build 3.4.4 (NanoSight Ltd., Minton Park, UK). Two microliters of EVs solution were diluted in 958 µL of filtered PBS−. The NTA measurement conditions were detection threshold 5, camera level 12, temperature 22.7 °C and measurement time 60s. Three recordings were performed for each sample.

Cryo-EM

The morphology of EVs were examined by cryo-EM. For this, 3 µL of each EVs-enriched sample was placed onto 400 copper mesh Lacey Carbon TEM perforated carbon film grids (ed Pella, Inc. USA) that had been glow-discharged. Then, the samples were blotted to form a thin film and plunged into liquid ethane-N2(l) using a Leica EM GP cryoworkstation (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The grids were subsequently transferred to a 626 Gatan cryoholder and kept at −179 °C throughout analysis. EVs Samples were visualized using a Jeol JEM 2011 TEM (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) set to an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Images were captured on a Gatan Rio 16 CMOS camera using the Digital Micrograph 2 software suite (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA).

Flow cytometry

The analysis was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the International Society of Extracellular Vesicles (MIFlowCyt-EV)14, using the high-sensitivity flow cytometer CytoFLEX S (Beckman Coulter), equipped with violet (405 nm), blue (488 nm), yellow (561 nm), and red (638 nm) lasers. The cytometer was operated in low-flow mode (10 µL/min), with a minimum acquisition of 10,000 events per sample. Distilled water, filtered through a 0.1-µm filter, was used as the sheath fluid. To maintain optimal performance, continuous washing with 0.1-µm-filtered distilled water was performed every 2–3 EVs samples, as recommended by60. The optical configuration was optimized to use side scatter (SSC) detection from the 405-nm laser (v-SSC). Both forward scatter (FSC) and v-SSC were set to logarithmic scales, and fluorescence channels were also adjusted to logarithmic gains. The EV detection region was initially delineated using recombinant exosomes tagged with GFP (1 × 10⁶ EVs/mL; SAE0193, Merck) and analyzed in the vSSC/FSC channels. GFP fluorescence provided the reference signal, and the vSSC and FSC thresholds were optimized according to the approach described by Barranco et al.59. In brief, the region was defined based on the distribution of GFP, with the fluorescence threshold set at 800. The gating parameters were fine-tuned to include over 90% of the total events within a defined area of the vSSC/FSC dot plot, which was subsequently designated as the EV analysis gate. For the examination of EVs, events falling within this region—regardless of their fluorescence—were included, ensuring comprehensive analysis of the EV population. EVs samples were diluted in 0.1-µm-filtered PBS to a final concentration of 1–2 × 10⁶ EVs/mL and incubated with CellTrace CFSE (0.1 µM, Thermo Fisher) and tetraspanin antibodies (1:50), including anti-CD63-FITC (130-118-076, Miltenyi Biotec), anti-CD9-PEVio615 (130-118-811, Miltenyi Biotec) and anti-CD81-PEVio770 (130-107-922, Miltenyi Biotec). Considering the technical specifications of the CytoFLEX, FITC was excited by the 488 nm laser, and fluorescence was captured in the B1 channel (filter 525/25 nm). PEVio615 was excited by the 561 nm laser, and fluorescence was captured on the R2 channel (filter 615/20 nm). Lastly, PEVio770 was excited by the 405 nm laser, and fluorescence was captured in the B3 channel (filter 450/50 nm). A 0.1-µm-filtered PBS was employed to prepare working solutions to reduce background noise. The incubation was performed for 30 min at 37 °C, after which 200 µL of 0.1-µm-filtered PBS was added to stop the reaction. Prior to incubation, working solutions of CFSE and antibodies were centrifuged three times (17,000 × g, 10 min each) to pellet any residual particles. Fluorescence controls were carried out to verify the specificity of the CFSE and CD9, CD63, and CD81 antibodies, using separate buffers for each. To validate the specificity and accuracy of the staining protocol, several controls were implemented. These included 0.1-µm-filtered PBS, unstained EV samples, and a negative control consisting of antibody mixes incubated in the absence of EVs, as well as a CFSE-only control processed without EVs to rule out dye aggregation or background fluorescence. All controls were processed under the same incubation conditions and acquired using identical CytoFLEX settings. These negative controls confirmed the absence of background signal and non-specific binding, and served as a reference to define fluorescence thresholds for the detection of labeled EVs. Moreover, they demonstrated that both CFSE and all three antibodies consistently and specifically bound to EVs, generating clear and reproducible fluorescence signals at the working concentration. The inclusion of anti-CD63-FITC, anti-CD9-PEVio615 and anti-CD81-PEVio770 was particularly useful for confirming the presence of canonical tetraspanins on EV membranes, reinforcing the reliability of the detection strategy. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using the CytoFLEX S cytometer and CytoExpert software.

EVs staining and uptake by cumulus-oocyte complexes

EVs lipid membranes were labeled with PKH26 (Cat. nº MINI26) as previously described by Leal et al.58, with some modifications. Briefly, 25 µL of the EVs suspension in PBS − were mixed with 125 µL of diluent C (Cell mixture) and for the negative control, 25 µL of PBS − without EVs were also mixed with 125 µL of diluent C. Next, the dye was diluted in diluent C (1:250), and each sample (EVs and negative control) was then placed into 125 µL of the dye mix and incubated for 5 min at room temperature (RT) (final concentration of dye is 5 × 10−6 mol/L). To stop the labelling reaction 250 µL of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS − was added per sample for 1 min. Labeled EVs and labeled PBS − for negative control were washed four times (three 15 min centrifugations at 2.000 g and one for 20 min) with 9 mL PBS − in 10 K MWCO Pierce protein concentrators.

Labeled EVs were diluted in IVM medium up to a final concentration of 16 × 109 particles/mL, equivalent amount of labeled PBS − was used for the negative control. Groups of 10 oocytes (4 replicates) were IVM in 50 µL droplets of this medium covered with 3.5-4 mL of NidOil (Nicadon International AB, Göthenburg, Sweden; Cat. nº NO-100) for 9–21 h at 38.5 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified air atmosphere25. Oocytes were then collected and washed three times in PBS to remove not internalized EVs, followed by fixation in 2% (w/v) paraformaldehyde-PBS (PFA-PBS) for 20 min at 38.5 °C. After washing in PBS oocytes were placed in a 3 µL droplet of Vectashield (Vysis Inc., Downers Grove, USA; Cat. nº H-1000-10) on poly L-lysine-treated coverslips with a self- adhesive reinforcement ring and gently flattened with a coverslip. Preparations were sealed with clear nail varnish and analyzed under a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP5, Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

Oocyte in vitro maturation

IVM was performed as previously described61 with minor modifications. Briefly, COCs with at least three compact layers of cumulus cells (CCs) and a homogeneous cytoplasm were washed (x3) in modified Dulbecco’s PBS (PBS supplemented with 0.036 mg/mL sodium pyruvate, 0.05 mg/mL gentamicin, and 0.5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, BSA). Then, groups of 20 oocytes were transferred to 100 µL of maturation medium (TCM-199 (Cat. nº M4530) supplemented with 10% (v/v) exosome depleted fetal bovine serum (FBS-EVs; Exo‑FBS™; System Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA, USA; Cat. nº EXO‑FBS‑250 A‑1), 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor, and 50 mg/mL gentamicin) covered with 3.5-4 mL of NidOil for 24 h at 38.5 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified air atmosphere.

Oocyte vitrification and warming

Oocytes IVM for 21 h were vitrified/warmed as previously described by García-Martínez et al.5. First, oocytes were denuded by gently pipetting in PBS until only corona radiata was present. Then, oocytes were transferred to equilibration solution (ES) consisting of holding media (HM; Hepes-buffered TCM 199 (Cat. nº M7528) with 20% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS)) containing 7.5% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide (Me2SO) and 7.5% (v/v) ethylene glycol (EG) for 2:30 min. Oocytes were then transferred to the vitrification solution (VS), HM containing 15% (v/v) Me2SO, 15% (v/v) EG, and 0.5 M sucrose for 30–40 s. After that, within 20–30 s, up to five oocytes were loaded onto a Cryotop® and almost all the solution was removed to leave only a thin layer covering the oocytes. Oocytes were immediately plunged into liquid nitrogen.

Warming was performed by quickly immersing the tip of the Cryotop® in warming solution (WS) 1 containing HM supplemented with 1 M sucrose. After 1 min, oocytes were transferred into WS2 containing HM supplemented with 0.5 M sucrose for 3 min and then to HM for 5 min. All the vitrification/warming steps were performed at 38.5 °C. Oocytes were then transferred back into the maturation medium and allowed to mature for 3 additional hours at 38.5 °C in humidified air containing 5% CO2.

In vitro fertilization and embryo culture

After 24 h of IVM, frozen/thawed semen from a proven-fertility bull provided by CENSYRA (Centro de Selección y Reproducción Animal), a certified artificial insemination center in Asturias, Spain, was processed for IVF using BoviPure® density gradient centrifugation (Nicadon International AB, Gothenburg, Sweden; Cat. nº BP-100, BD-100 and BW-100). The sperm were centrifuged at 300 x g for 10 min on a gradient consisting of 1 mL of 40% and 1 mL of 80% BoviPure, resuspended in 3 mL of Boviwash and pelleted by centrifugation at 300 x g for 5 min. Spermatozoa were counted in a Neubauer chamber and diluted in IVF media to a final concentration of 1 × 106 spermatozoa/mL. 100µL droplets of diluted sperm were prepared under 3.5-4 mL of NidOil and 20 oocytes/droplet were co-incubated at 38.5 °C, 5% CO2, and high humidity for 18–20 h. The IVF medium consisted of Tyrode’s medium supplemented with 25 mM sodium bicarbonate, 22 mM sodium lactate, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 6 mg/mL fatty acid-free BSA and 1 mg/mL heparin-sodium salt.

Following fertilization, presumptive zygotes were pipetted and gently denuded in PBS. Groups of 25 presumptive zygotes were transferred to 25 µL droplets of BO-IVC™ (IVF Bioscience, United Kingdom; Cat. nº 71005) covered with 3.5 mL of NidOil under a humidified atmosphere at 38.5 °C with 5% CO2 and 5% O2. Yields were recorded at 48 h (cleavage stage) and Days 7 and 8 (blastocysts stage) post-insemination (pi). D8 embryos were classified in terms of the degree of blastocoel expansion into three groups: non-expanded (early and non-expanded blastocysts), expanded and hatched (hatching and hatched blastocysts) blastocysts.

Spindle configuration

After 24 h of IVM, oocytes from four replicates (18–30 oocytes per replicate and group) were completely denuded of CCs by gentle pipetting prior to immunostaining for tubulin and chromatin detection5. Denuded oocytes were fixed in 2% (w/v) PFA-PBS for 20 min at 38.5 °C. Permeabilization and blocking were performed in 2.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS with 3% (w/v) BSA for 30 min at 38.5 °C. After washing in PBS, oocytes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with mouse anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (TU-01, Invitrogen, CA, USA; Cat. nº 13-8000) diluted 1:250. Oocytes were then incubated with anti-mouse IgG antibody Alexa Fluor™ 488 (Molecular Probes, Paisley, UK; Cat. nº A-11001) 1:5000 dilution for 1 h at 38.5 °C. and washed (x3) in 0.005% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS at 38.5 °C for 20 min. Groups up to 30 oocytes were mounted on poly L-lysine-treated coverslips with a self- adhesive reinforcement ring with 3 µL of Vectashield containing 125 ng/mL 40,60-diamidino-2-phenylindole hydrochloride (DAPI) (Vysis Inc., Downers Grove, USA; Cat. nº H-1200-10) and gently flattened with a coverslip. Preparations were sealed with clear nail varnish and immediately examined under an epifluorescence microscope (Axioscop 40FL; Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) to visualize tubulin (Alexa Fluor™ 488; excitation 488 nm; emission 525 nm) and chromatin (DAPI; excitation 405 nm; emission 460 nm).

The criteria used to classify chromosome and microtubule distributions have been described elsewhere5. In brief, the meiotic spindle was considered as normal when exhibited a symmetric barrel-shape structure composed of well-organized microtubules extending from pole to pole with chromosomes compactly aligned along the equatorial plate, forming a distinct and cohesive metaphase arrangement. In contrast, spindle was considered abnormal when microtubules displayed disorganization, partial or complete decondensation, or the absence of microtubule structures. Chromosome abnormalities were identified when chromosomes appeared scattered, improperly aligned, or exhibited reduced condensation. Detailed images of these normal and abnormal patterns are shown in Fig. 5.

Representative confocal laser-scanning photographs of spindle microtubule and chromosome configurations in IVM bovine oocytes after vitrification/warming. (A, B) Normal shaped Metaphase II (MII) spindle with microtubules forming a clear meiotic spindle with compact chromosomes (C) Abnormal spindle morphology showing decondensed microtubules and partly disorganized chromosomes. (D) Abnormal spindle structure with decondensed/disorganized microtubules and disorganized chromosomes. (E) Abnormal spindle structure with disorganized microtubules and decondensed chromosomes (F) Chromosomes with an aberrant, less condensed appearance. Note the absence of microtubules. Green, tubulin (with anti-α-tubulin antibody and Alexa FluorTM 488); blue, chromosomes (DAPI). Scale bar: 5 μm.

TUNEL detection of fragmented oocyte DNA

Oocyte DNA fragmentation was assessed using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick-end labeling (TUNEL; Cat. nº 11684795910) kit after 24 h of IVM62. Briefly, oocytes were completely denuded of cumulus cells by gentle pipetting and fixed in 2% (w/v) PFA-PBS for 20 min at 38.5 °C. Permeabilization was conducted in 2.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min at 38.5 °C. Subsequently, oocytes were washed in PBS and incubated in the TUNEL reaction cocktail at 38.5 °C for 1 h in a dark humidified chamber. Oocytes exposed to DNase I (50 mL of RQ1 RNase-free Dnase (50 U/mL)) for 15 min at RT served as positive controls, while oocytes incubated in the absence of the terminal TdT enzyme served as negative controls. Positive and negative controls were included in each assay. After washing in PBS, oocytes were mounted on poly L-lysine-treated coverslips fitted with a self-adhesive reinforcement ring with 3 µL of Vectashield containing 125 ng/mL of DAPI and flattened with a coverslip. Preparations were sealed with clear nail varnish and stored at 4 °C in the dark until their observation within the following 2 days. An epifluorescence microscope was used to localize the nuclei (DAPI; excitation 405 nm; emission 460 nm) and detect DNA fragmentation (fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated TUNEL label; excitation 488 nm; emission 517 nm). Nuclei were categorized as either intact (TUNEL [-]; blue stain) or fragmented (TUNEL [+]; green stain) DNA. The percentage of TUNEL positive oocytes was calculated as the ratio between TUNEL [+] oocytes and the total number of oocytes analyzed in each group.

Differential cell count and apoptosis staining of blastocysts

D8 non-expanded, expanded, and hatched bovine blastocysts were immunostained for differential cell counts and apoptosis analysis61. All steps were performed at 38.5 °C unless otherwise indicated. First, blastocysts were fixed in 2% (v/v) PFA-PBS for 15 min followed by permeabilization in 0.01% Triton X-100 in PBS supplemented with 5% normal donkey serum (PBS-NDS) for 1 h at RT.

Then, the embryos were washed in PBS and incubated at 4 °C overnight with the primary antibodies mouse anti-SOX2 primary antibody (1:100; Invitrogen, CA, USA; Cat. nº MA1-014) and rabbit anti-caspase 3 primary antibody (1:250; Cell Signaling Technologies, CA, USA; Cat. nº CST9664S,) inside a humidified chamber. After that, the embryos were incubated with the secondary antibody goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor™ 568 (1:500; ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA; Cat. nº A-11004) and a goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor™ 488 antibody (1:500; ThermoFisher, Waltham MA, USA; Cat. nº A-11001) for 1 h in a humidified chamber. Following both antibody incubations, embryos were washed (x3) in 0.005% Triton X-100 in PBS-NDS for 20 min. Embryos were mounted on coverslips fitted with a self-adhesive reinforcement ring with 3 µL of Vectashield containing 125 ng/mL of DAPI and flattened with a coverslip. The preparation was sealed with clear nail varnish and stored at 4 °C in dark before observation within the following 2 days in an epifluorescence microscope to examine the ICM (SOX2-Alexa Fluor™ 568; excitation 561 nm; emission 603 nm), cell nucleus (DAPI; excitation 405 nm; emission 460 nm) and DNA fragmentation (caspase 3- Alexa Fluor™ 488; excitation 488 nm; emission 525 nm). The AR was calculated as the ratio of caspase-positive cells/total cell number (TCN).

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests and graphs were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA) and R software V 4.1.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). The Saphiro-Wilk test and the Levene Test were used to check normality of the data and homogeneity of variance, respectively. When required, data were linearly transformed into √x or arcsin √x prior to running statistical tests. Concentration and size of the EVs were analyzed by an unpaired t-test. Spindle morphology and TUNEL analysis results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA while, embryo development, cell count and apoptosis rates were analyzed by two-ways ANOVA. Secondly, Tukey test for spindle morphology and TUNEL analysis and Fisher’s LSD test for embryo development, cell count and apoptosis rates were conducted for pairwise comparisons. Results are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Mogas, T., García-Martínez, T. & Martínez‐Rodero, I. Methodological approaches in vitrification: enhancing viability of bovine oocytes and in vitro‐produced embryos. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 59, e14623. https://doi.org/10.1111/rda.14623 (2024).

Mogas, T. Update on the vitrification of bovine oocytes and in vitro-produced embryos. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 31, 105. https://doi.org/10.1071/rd18345 (2019).

Dujíčková, L., Makarevich, A. V., Olexiková, L., Kubovičová, E. & Strejček, F. Methodological approaches for vitrification of bovine oocytes. Zygote 29, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0967199420000465 (2021).

Somfai, T. et al. Optimization of cryoprotectant treatment for the vitrification of immature cumulus-enclosed Porcine oocytes: comparison of sugars, combinations of permeating cryoprotectants and equilibration regimens. J. Reprod. Dev. 61, 571–579. https://doi.org/10.1262/jrd.2015-089 (2015).

García-Martínez, T. et al. Impact of equilibration duration combined with temperature on the outcome of bovine oocyte vitrification. Theriogenology 184, 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.02.024 (2022).

Leal, G. R. et al. Lipid modulation during IVM increases the metabolism and improves the cryosurvival of Cat oocytes. Theriogenology 214, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2023.10.001 (2024).

Girka, E., Gatenby, L., Gutierrez, E. J. & Bondioli, K. R. The effects of microtubule stabilizing and recovery agents on vitrified bovine oocytes. Theriogenology 182, 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.01.031 (2022).

Morató, R. et al. Effects of pre-treating in vitro‐matured bovine oocytes with the cytoskeleton stabilizing agent taxol prior to vitrification. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 75, 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrd.20725 (2008).

Cao, B. et al. Oxidative stress and oocyte cryopreservation: recent advances in mitigation strategies involving antioxidants. Cells 11, 3573. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11223573 (2022).

García-Martínez, T. et al. Glutathione Ethyl ester protects in vitro-maturing bovine oocytes against oxidative stress induced by subsequent vitrification/warming. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207547 (2020).

Ávila, A. C. F. C. M. D. et al. Extracellular vesicles and its advances in female reproduction. Anim. Reprod. 16, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.21451/1984-3143-ar2018-00101 (2019).

Gualtieri, R. et al. In vitro culture of mammalian embryos: is there room for improvement? Cells 13, 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13120996 (2024).

Xue, Y., Zheng, H., Xiong, Y. & Li, K. Extracellular vesicles affecting embryo development in vitro: a potential culture medium supplement. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1366992. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1366992 (2024).

Welsh, J. A. et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): from basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 13, e12404. https://doi.org/10.1002/jev2.12404 (2024).

Van Niel, G. et al. Challenges and directions in studying cell–cell communication by extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-022-00460-3 (2022).

Saeed-Zidane, M. et al. Cellular and exosome mediated molecular defense mechanism in bovine granulosa cells exposed to oxidative stress. PLoS ONE. 12, e0187569. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187569 (2017).

Rodrigues, T. A. et al. Follicular fluid exosomes act on the bovine oocyte to improve oocyte competence to support development and survival to heat shock. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 31, 888–897. https://doi.org/10.1071/rd18450 (2019).

Gebremedhn, S. et al. Extracellular vesicles shuttle protective messages against heat stress in bovine granulosa cells. Sci. Rep. 10, 15824. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72706-z (2020).

Gabryś, J. et al. Extracellular vesicles from follicular fluid May improve the nuclear maturation rate of in vitro matured mare oocytes. Theriogenology 188, 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.05.022 (2022).

Gabryś, J. et al. Follicular fluid-derived extracellular vesicles influence on in vitro maturation of equine oocyte: impact on cumulus cell viability, expansion and transcriptome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 3262. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25063262 (2024).

Gabryś, J. et al. Investigating the impact of extracellular vesicle addition during IVM on the fertilization rate of equine oocytes following ICSI. Reprod. Biol. 24, 100967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repbio.2024.100967 (2024).

Sohel, M. M. H. et al. Exosomal and non-exosomal transport of extra-cellular MicroRNAs in follicular fluid: implications for bovine oocyte developmental competence. PLoS ONE. 8, e78505. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078505 (2013).

Hung, W. T., Hong, X., Christenson, L. K. & McGinnis, L. K. Extracellular vesicles from bovine follicular fluid support cumulus expansion. Biol. Reprod. 93, 117. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.115.132977 (2015).

Navakanitworakul, R. et al. Characterization and small RNA content of extracellular vesicles in follicular fluid of developing bovine antral follicles. Sci. Rep. 6, 25486. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25486 (2016).

Da Silveira, J. C. et al. Supplementation with small-extracellular vesicles from ovarian follicular fluid during in vitro production modulates bovine embryo development. PLoS ONE. 12, e0179451. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179451 (2017).

Hung, W. T. et al. Stage-specific follicular extracellular vesicle uptake and regulation of bovine granulosa cell proliferation. Biol. Reprod. 97, 644–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolre/iox106 (2017).

Hailay, T. et al. Extracellular vesicle-coupled MiRNA profiles in follicular fluid of cows with divergent post-calving metabolic status. Sci. Rep. 9, 12851. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49029-9 (2019).

De Ávila, A. C. F. C. M. et al. Estrous cycle impacts MicroRNA content in extracellular vesicles that modulate bovine cumulus cell transcripts during in vitro maturation. Biol. Reprod. 102, 362–375. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolre/ioz177 (2020).

Bastos, N. M. et al. High body energy reserve influences extracellular vesicles MiRNA contents within the ovarian follicle. PLoS One. 18, e0280195. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280195 (2023).

Gad, A. et al. Extracellular vesicle-microRNAs mediated response of bovine ovaries to seasonal environmental changes. J. Ovarian Res. 16, 101. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-023-01181-7 (2023).

da Silva Rosa, P. M. et al. Corpus luteum presence in the bovine ovary increase intrafollicular progesterone concentration: consequences in follicular cells gene expression and follicular fluid small extracellular vesicles MiRNA contents. J. Ovarian Res. 17, 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-024-01387-3 (2024).

Kim, E., Ra, K., Lee, M. S. & Kim, G. A. Porcine follicular fluid-derived exosome: the pivotal material for Porcine oocyte maturation in lipid antioxidant activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9807. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24129807 (2023).

No, J. et al. Vitro maturation using Porcine follicular fluid-derived exosomes as an alternative to the conventional method. Theriogenology 230, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2024.08.030 (2024).

Xin, X. et al. Exploring LncRNA expression in follicular fluid exosomes of patients with obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome based on high-throughput sequencing technology. J. Ovarian Res. 17, 220. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-024-01552-8 (2024).

Nepsha, O. S. et al. Changes in the transcription of proliferation- and apoptosis-related genes in embryos in women of different ages under the influence of extracellular vesicles from donor follicular fluid in vitro. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 176, 658–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10517-024-06087-y (2024).

Ding, Q. et al. Comparison of MicroRNA profiles in extracellular vesicles from small and large goat follicular fluid. Anim. (Basel). 11, 3190. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11113190 (2021).

Capra, E. et al. Variations of follicular fluid extracellular vesicles MiRNAs content in relation to development stage and season in Buffalo. Sci. Rep. 12, 14886. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18438-8 (2022).

De Ferraz, A. M. M. Follicular extracellular vesicles enhance meiotic resumption of domestic Cat vitrified oocytes. Sci. Rep. 10, 8619. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65497-w (2020).

Asaadi, A. et al. Extracellular vesicles from follicular and ampullary fluid isolated by density gradient ultracentrifugation improve bovine embryo development and quality. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22020578 (2021).

Tian, Y. et al. Quality and efficiency assessment of six extracellular vesicle isolation methods by nano-flow cytometry. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 9, 1697028. https://doi.org/10.1080/20013078.2019.1697028 (2020).

Macaulay, A. D. et al. The gametic synapse: RNA transfer to the bovine oocyte. Biol. Reprod. 91, 90, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.114.119867 (2014).

Kang, H. et al. Follicular fluid-derived extracellular vesicles improve in vitro maturation and embryonic development of Porcine oocytes. Korean J. Vet. Res. 63, e40. https://doi.org/10.14405/kjvr.20230044 (2023).

Zhao, X. et al. Melatonin inhibits apoptosis and improves the developmental potential of vitrified bovine oocytes. J. Pineal Res. 60, 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12290 (2016).

Solati, A. et al. The effect of antioxidants on increased oocyte competence in IVM: a review. RDM 7, 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1097/RD9.0000000000000063 (2023).

Ahmadian, S. et al. Different storage and freezing protocols for extracellular vesicles: a systematic review. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 15, 453. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-024-04005-7 (2024).

Yuan, C. et al. Follicular fluid exosomes: important modulator in proliferation and steroid synthesis of Porcine granulosa cells. FASEB J. 35, e21610. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202100030rr (2021).

Grosbois, J. & Demeestere, I. Dynamics of PI3K and Hippo signaling pathways during in vitro human follicle activation. Hum. Reprod. 33, 1705–1714. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey250 (2018).

Lu, X. et al. Stimulation of ovarian follicle growth after AMPK Inhibition. Reproduction 153, 683–694. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep-16-0577 (2017).

Battaglia, R. et al. Ovarian aging increases small extracellular vesicle CD81 + release in human follicular fluid and influences MiRNA profiles. Aging 12, 12324–12341. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.103441 (2020).

Da Silveira, J. C., Veeramachaneni, D. N. R., Winger, Q. A., Carnevale, E. M. & Bouma, G. J. Cell-secreted vesicles in equine ovarian follicular fluid contain MiRNAs and proteins: a possible new form of cell communication within the ovarian follicle. Biol. Reprod. 86, 3, (71), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.111.093252 (2012).

Diez-Fraile, A. et al. Age-associated differential MicroRNA levels in human follicular fluid reveal pathways potentially determining fertility and success of in vitro fertilization. Hum. Fertil. 17, 90–98. https://doi.org/10.3109/14647273.2014.897006 (2014).

Gu, Y. et al. Metabolomic profiling of exosomes reveals age-related changes in ovarian follicular fluid. Eur. J. Med. Res. 29, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01586-6 (2024).

Sidrat, T. et al. Extracellular vesicles improve embryo cryotolerance by maintaining the tight junction integrity during Blastocoel re-expansion. Reproduction 163, 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep-21-0320 (2022).

Rowlison, T., Ottinger, M. A. & Comizzoli, P. Exposure to epididymal extracellular vesicles enhances immature sperm function and sustains vitality of cryopreserved spermatozoa in the domestic Cat model. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 2061–2071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-021-02214-0 (2021).

De Ferraz, A. M. M., Nagashima, M., Noonan, J. B., Crosier, M. J., Songsasen, N. & A. E. & Oviductal extracellular vesicles improve post-thaw sperm function in red wolves and cheetahs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3733. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21103733 (2020).

Kowalczyk, A. & Kordan, W. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the use of exosomes in the regulation of the mitochondrial membrane potential of frozen/thawed spermatozoa. PLoS ONE. 19, e0303479. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303479 (2024).

Sawicki, S. et al. Extracellular vesicles obtained from equine mesenchymal stem cells isolated from adipose tissue improve selected parameters of stallion semen after cryopreservation. Ann. Anim. Sci. 25, 189–200. https://doi.org/10.2478/aoas-2024-0073 (2025).

Leal, C. L. V. et al. Extracellular vesicles from oviductal and uterine fluids supplementation in sequential in vitro culture improves bovine embryo quality. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 13, 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-022-00763-7 (2022).

Barranco, I. et al. Immunophenotype profile by flow cytometry reveals different subtypes of extracellular vesicles in Porcine seminal plasma. Cell. Commun. Signal. 22, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-024-01485-1 (2024).

Cañón-Beltrán, K. et al. Isolation, characterization, and MicroRNA analysis of extracellular vesicles from bovine oviduct and uterine fluids. Methods Mol. Biol. 2273, 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-1246-0_16 (2021).

Martínez-Rodero, I. et al. silico-designed vitrification protocols: an approach to improve survival of in vitro produced-bovine embryos. Reproduction 167, e240036. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep-24-0036 (2024).

Vendrell-Flotats, M. et al. Vitro maturation with leukemia inhibitory factor prior to the vitrification of bovine oocytes improves their embryo developmental potential and gene expression in oocytes and embryos. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7067. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-024-01485-1 (2020).

Funding

This study was supported by research: Projects PID2020-116531RB-I00 to TM, PID2021-126988OB-I00 to AJS and PID2023-149027OB-I00 to DR, and the predoctoral scholarship PRE2021-098675 to Ms. Diaz-Muñoz funded by MCIN/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033/; Project No. 2021 SGR 00900 and predoctoral scholarship DI00002 to Ms Gago funded by the Generalitat de Catalunya. Ms Yulia N. Cajas was funded by Margarita Salas contract from European Union NextGenerationEU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization. J.D.-M., K.C.-B., Y.N.C., D.R., and T.M.; Formal analysis J.D.-M., K.C.-B., and Y.N.C.; Funding acquisition. A.J.S., and T.M.; Investigation. J.D.-M., S.G., and M.I.-C.; Methodology. J.D.-M., K.C.-B., and Y.N.C.; Project administration. T.M.; Resources. D.R., A.J.S., and T.M.; Supervision. T.M., and D.R.; Validation. T.M., and D.R.; Writing – original draft. J.D.-M., K.C.-B., and Y.N.C., S.G., and M.I.-C; Writing – review & editing. A.J.S., D.R., and T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Diaz-Muñoz, J., Cañón-Beltrán, K., Cajas, Y.N. et al. Enhancing developmental potential of vitrified in vitro matured bovine oocytes using extracellular vesicles from large follicles. Sci Rep 15, 33243 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17981-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17981-4