Abstract

Pleomorphic adenoma (PA), the most common benign salivary gland tumor, harbors unpredictable risks of recurrence and malignant transformation into carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (CXPA), posing significant clinical challenges. To better delineate the tumor transformation trajectory, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing of normal salivary gland, primary PA, recurrent PA (rPA), and CXPA. Cell trajectory reconstruction, differential expression gene identification, and key gene network analysis were integrated to characterize molecular transitions and intercellular crosstalk driving PA recurrence and malignant transformation. Immunohistochemistry was used to validate key findings. GALNT13 + myoepithelial cells were identified as CXPA-specific malignant progenitors, delineating early malignant conversion. Concurrently, MIF + myoepithelial cells exhibited enhanced tissue-destructive capabilities. Fibroblasts enforced fibrotic restraint in primary PA and drove extracellular matrix degradation in CXPA. The tumor microenvironment exhibited stage-specific adaptations, with CXPA favoring pro-inflammatory MIF-CD74/CD44 signaling and rPA adopting immunosuppressive traits. Stromal reprogramming and immune-editing dynamics collectively orchestrated microenvironmental adaptation, linking cellular heterogeneity to clinical aggressiveness. This study provides the first comprehensive molecular atlas of PA-to-CXPA transformation, revealing malignant specialization of the myoepithelial subpopulation, fibroblast-mediated stromal reprogramming, and immune-editing driven microenvironmental adaptation. These findings provide a framework for precision stratification of the malignant potential of PA, while positioning microenvironmental intervention as a cornerstone of future clinical strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pleomorphic adenoma (PA), the most common benign neoplasm of the salivary glands, particularly the parotid gland, presents a paradox in clinical management1,2,3. Although histologically defined as a benign tumor, PA is notorious for its unpredictable recurrence or malignant transformation trajectory, with a postoperative recurrence rate as high as 45%, and 0–23% of recurrent cases progressing to carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (CXPA)4,5,6,7. CXPA, a rare but aggressive malignancy, arises through complex etiopathogenetic pathways involving accumulated genetic alterations (e.g., HRAS/TP53 mutations), myoepithelial dedifferentiation, and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling8,9,10. The critical barrier to precise clinical management is the lack of validated biomarkers capable of predicting these events. Current biomarkers fail to stratify recurrence or malignant risk11,12,13. Besides, the cellular origins underlying these processes remain poorly characterized, constituting a critical knowledge gap in our mechanistic understanding. Most fundamentally, intratumor heterogeneity, which refers to distinct cellular subpopulations and their interactions within the tumor malignant transformation, remains poorly understood14,15,16,17.

The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized cancer biology by resolving cellular diversity, clonal evolution, and microenvironmental crosstalk with unprecedented resolution18,19. Recent research has identified stem-like populations and immune evasion mechanisms in salivary gland carcinomas, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma20. Conversely, the “benign” label assigned to PA has relegated it to the periphery of such investigations, creating a critical knowledge gap. Notably, emerging evidence suggests that genomic instability and microenvironmental reprogramming may occur even in histologically benign tumors21,22. Recent work reveals that CXPA develops via divergent pathways, including stromal reprogramming and immune evasion, even in histologically benign precursors23. A prior scRNA-seq study identified specific epithelial cell populations that may play a pivotal role in the origin and progression of PA24. However, genetic and functional heterogeneity at single-cell resolution has never been explored in relation to its recurrence and malignant transformation, and therefore, necessitating an inquiry into the biological behavior of such borderline tumors.

This study aims to address the cellular and microenvironmental mechanisms driving PA recurrence and malignant transformation into CXPA. By constructing the first single-cell atlas of PA-to-CXPA transformation encompassing normal salivary glands, primary PA (pPA), recurrent PA (rPA), and CXPA, we identify previously unrecognized cellular subpopulations and stromal-immune interactions that orchestrate the tumor swamp driving biological aggression in PA.

Our central discovery reveals that the myoepithelial cell plasticity and stemness underpin PA aggression, whereas fibroblast polarization and immune-editing processes sculpt permissive niches for PA transformation. Notably, this work depicts PA as a molecularly complex entity, thereby facilitating a more profound comprehension and establishing a foundational framework for deciphering the molecular mechanisms underlying the malignant transformation of PA.

Results

Single-cell atlas of recurrence and malignancy in pleomorphic adenoma

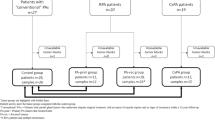

We collected three normal salivary gland tissues (two PG and one LG) and seven tumor tissues (including three pPA, two rPA, and two CXPA samples) for single-cell RNA sequencing, obtaining a total of 91,545 cells (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a). The two cases of CXPA in our cohort were myoepithelial carcinomas. Tumors were graded as low- (n = 1) or intermediate-grade (n = 1), with minimal capsular invasion observed in both cases (Supplementary Table S2). UMAP dimensionality reduction analysis classified the cells into seven main types: epithelial cells, myeloid cells, fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells, NK/T cells, B cells, and endothelial cells (Fig. 1b). The cellular composition of each tumor type showed that pPA exhibited abundant stromal components; rPA was characterized by immune activation; and CXPA consisted mainly of tumor epithelial cells (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1c). Epithelial cells were enriched for KRT7/KRT8; Myeloid cells expressed C1QA/C1QB; Fibroblasts were defined by COL1A1 and DCN; Mural cells were marked by ACTA2 and RGS5; NK/T cells expressed CD3D and NKG7; Endothelial cells characterized with FLT1/PECAM1; B cells expressed signal IGKC and CD79A (Fig. 1d). CNV analysis showed that CXPA samples exhibited significant CNV, particularly on chromosomes 7, 8, 9, 18, 19, and 22, suggesting a high degree of genomic instability in the tumor cells (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1b, d).

Single-cell transcriptomic profiling of the multicellular ecosystem of pleomorphic adenoma. (a) Workflow showing the collection and processing of 10 fresh patient samples for scRNA-seq. (b) UMAP plot of 91,545 single cells from scRNA-seq labeled by cell type with different colors. (c) The proportion of different cell populations identified in different tissue type. (d) FeaturePlot showing the expression patterns of key marker genes across different cell subpopulations. (e) Heatmap showing chromosomal copy number variation level in all cell populations, blue indicates deletion and red indicates amplification.

Epithelial subpopulation characteristics and myoepithelial cell heterogeneity analysis

Further analysis of the tumor epithelium revealed a significant upregulation of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) molecule in CXPA samples compared to pPA, while the S100A family proteins were significantly upregulated in rPA (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2j). Epithelial cells (n = 38,541) were further subdivided into various subpopulations (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Trajectory inference indicated that chondroid epithelial and myoepithelial cells are derived from basal cells during tumor progression, suggesting that basal cells may serve as the origin of PA tumor development (Supplementary Fig. 2e). Notably, we observed a gradual increase in the proportion of myoepithelial cells in primary, recurrent, and malignant tissues, prompting further investigation into their specific characteristics (Fig. 2c). Myoepithelial cells were further stratified into three subpopulations (Fig. 2d). GALNT13 + myoepithelial cells exhibited the most prominent CNV, and were exclusively found in CXPA samples (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2d). Notably, it revealed that intermediate-grade CXPA case showed significantly higher proportions of GALNT13 + myoepithelial cells than low-grade tumor (Supplementary Fig. 2k), suggesting a molecular basis for its association with aggressive behavior. In contrast, PLCG2 + myoepithelial cells were predominant in pPA, while TAFA2 + myoepithelial cells were exclusively accumulated in rPA (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2f, h). An external bulk-RNA dataset containing invasive malignant pleomorphic adenoma (IMPA) and corresponding normal tissues confirmed the high abundance of the GALNT13 + myoepithelial subpopulation in CXPA (Fig. 2f). GSVA analysis indicated that GALNT13 + myoepithelial cells were highly activated in the cell cycle, stemness, and E2F pathways, while PLCG2 + myoepithelial cells upregulated apoptosis, TNF, and IL-6-related pathways. TAFA2 + myoepithelial cells upregulated proliferation-related and WNT pathways (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 2i). mIHC staining validated the spatial distribution of myoepithelial cells in different tumor types (Fig. 2h). These findings highlight the complex heterogeneity of myoepithelial cells and their potential functional roles in tumors.

Subclustering of epithelial cells. (a) The heatmap displays the most significantly differentially expressed genes in epithelial cells across different groups. (b) UMAP plot of 38,541 single cells from epithelial cells used for subclustering. (c) The proportions of identified epithelial cell populations in each tissue type. (d) UMAP plot of 7453 single cells from myoepithelial cells used for subclustering. (e) Rain cloud plot showing the CNV scores across different myoepithelial subsets. (f) The paired boxplot displays the differences in GSVA scores of myoepithelial subsets’ characteristics between Normol and IMPA in the external bulk dataset. (g) Heatmap showing GSVA scores for various signaling pathways across different myoepithelial subsets. (h) Representative images of multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC) showing the expression of CK14 (red) and MYLK (green) in PA sections; scale bar = 100 μm.

Developmental trajectory, metabolic features, and key gene network analysis of myoepithelial cells

We further analyzed the characteristics of myoepithelial cells in different PA groups. Through single-cell pseudotime analysis, we constructed the developmental trajectory of myoepithelial cells and identified two distinct differentiation paths representing the transformation from pPA to rPA and from pPA to CXPA (Fig. 3a). At the transcriptional regulation level, we used the pyscenic algorithm to identify the specific transcription factors for myoepithelial cells in each group. This includes pPA with KLF13, NFIC, and MXD4 activity; rPA with MZF1, ZNF429, and BACH2 activation; and CXPA with SOX10, ZBTB2, and MYBL1 enrichment (Fig. 3b).

Subclustering of epithelial cells. (a) Pseudotime trajectory of myoepithelial subsets, divided into three states with group distributions (Top). Heatmap of differential gene expression in malignant and primary cells, with a bar plot showing enriched pathways associated with recurrence (Bottom). (b) Heatmap of the expression regulation by transcription factors, as estimated using SCENIC. (c) Heatmap of the estimated transcription factors module kit using SCENIC. (d) CytoTRACE values showing the distribution of differentiation states for each myoepithelial cell type. (e) Venn diagram showing the number of pseudotime genes with upregulation or downregulation (a cutoff of ≥ 1.2-fold change; orange), marker genes of different myoepithelial cell type(blue), module genes from hdWGCNA (pink), and DEGs in GSE179895(green). The overlapping genes were identified. (f) CytoTRACE values showing the corelation of MIF, TGFBR3 and FN1 with each myoepithelial cell type. (g) Volcano plots showing differential gene expression in MIF- vs MIF + myoepithelial cell (MEC) (left) and TGFBR3- vs TGFBR3 + MEC (right). (h)Hallmark gene set enrichment analysis of upregulated genes in MIF + myoepithelial cells. (i) Representative images of mIHC showing the expression of MYLK (green), CK14 (red), and MIF (pink) in PA sections; scale bar = 100 μm.

The CSI matrix was partitioned into three modules through regulatory submodules analysis. The most active myoepithelial subpopulations within these modules were found to be represented by GALNT13 + , TAFA2 + , and PLCG2 + , respectively (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Stemness analysis showed that GALNT13 + myoepithelial cells exhibited the strongest tumor stemness, which is consistent with their malignant tumor origin (Fig. 3d).

Next, we attempted to identify distinct characteristic molecules, particularly in myoepithelial cells representing primary, recurrent, and malignant PA tumors. The employment of the hdWGCNA algorithm facilitated the identification of seven gene modules associated with clinical grouping features. M1, M2, and M4 modules were most strongly associated with the clinical features of primary, recurrent, and malignant tumors. The enriched pathways for genes in each module are displayed in the figure (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c, d, e, f).

Following this, we integrated characteristic marker genes of myoepithelial cells, differentially expressed genes from external bulk RNA data, pseudotime feature genes, and hdWGCNA module genes. One gene was identified in CXPA samples, 27 genes in rPA, and 10 genes in pPA. Genes at the central positions in the protein interaction network were selected as representatives in myoepithelial cells, including MIF for CXPA, TGFBR3 for rPA, and FN1 for pPA. Notably, MIF was closely linked to cell stemness (Fig. 3e, f and Supplementary Fig. 3g, h, i).

We compared the differentially expressed genes between MIF + and MIF- myoepithelial cells, and between TGFBR3 + and TGFBR3- epithelial cells. It is noteworthy that genes upregulated in MIF + cells were associated with pathways such as cell stemness, EMT, and MYC, further emphasizing the crucial role of MIF in CXPA (Fig. 3g, h). mIHC staining validated the differential expression of MIF, TGFBR3, FN1, PLCG2, and LAMA3 in myoepithelial subpopulations across different tumor types (Fig. 3i and Supplementary Fig. 3j-m).

Heterogeneity of fibroblasts and their functional analysis in the tumor microenvironment

Next, we will explore the heterogeneity of fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment, particularly their distribution and function across different tumor groups. Upregulated genes in CXPA fibroblasts were associated with extracellular matrix remodeling (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4a). A further categorization was undertaken of the 38,541 fibroblasts, which yielded three primary subpopulations (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4d). The proportion of each subpopulation varied significantly across different tumor types (Supplementary Fig. 4b). COMP + fibroblasts were predominant in pPA samples, while SFRP4 + fibroblasts were more prevalent in CXPA (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Enrichment analysis revealed that the COMP + fibroblast subpopulation was significantly associated with the TGFβ and IL17 pathways, whereas the SFRP4 + subpopulation was linked to the PI3K-Akt and ECM-receptor interaction pathways (Fig. 4c, d).

Subclustering of fibroblast cells. (a) Significantly differentially expressed genes of fibroblast subsets across different tissue types. (b) UMAP plot of 38,541 single cells from fibroblasts used for subclustering. (c) A heatmap of marker genes for each fibroblast type. (d) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for fibroblast subsets. (e) Pseudotime and CytoTRACE analysis of fibroblast subsets. (Top-left) CytoTRACE analysis showing the predicted cellular differentiation trajectory. (Bottom-left) Pseudotime analysis depicting the progression of cells along the pseudotime axis. (Top-right) CytoTRACE scores across different fibroblast subsets. (Bottom-right) Boxplot comparing CytoTRACE scores among COMP + , LAMA2 + , and SFRP4 + fibroblast subsets. (f) Pseudotime projections of transcriptional changes in gene expression of fibroblast subsets, showing upregulated and downregulated genes based on the manifold. (g) Enrichment analysis showing the upregulation signaling pathways in the development of fibroblast subsets transition.

Pseudotime analysis and CytoTRACE scores indicated that fibroblasts may undergo dynamic changes in the tumor microenvironment, with COMP + fibroblasts at the differentiation initiation stage (Fig. 4e). During fibroblast development, the expression of SOD3 and COMP decreased, while LAMA2 and POSTN were gradually upregulated (Fig. 4f). Enrichment analysis of dynamic molecular changes revealed upregulation of the PI3K-Akt and Hippo signaling pathways during fibroblast transition (Fig. 4g). Additionally, we analyzed the transcription factor states of different fibroblast subpopulations. The results showed that the SFRP4 + fibroblast subpopulation exhibited high activation of FOXC2, GATA3, and ONECUT3, while the COMP + fibroblast subpopulation showed high activation of NR4A2, EGR1, and PAX1 (Supplementary Fig. 4f.).

Composition and functional characteristics of NK/T cell and myeloid cell subpopulations

In the NK/T cell subpopulation (n = 1,766), cells were further subdivided into NK cells, CD4 + Treg cells, CD8 + Tem cells, CD8 + Teff cells, and IL7R + DNT cells based on UMAP dimensionality reduction and the expression of cell marker genes (Fig. 5a, e). The distribution of these subpopulations varied significantly across different tumor types. In CXPA samples, NK cells were the most abundant, while IL7R + DNT cells were most prevalent in rPA. CD4 + Treg cells and CD8 + Teff cells were relatively enriched in pPA (Fig. 5b, d). We explored the transcription factor profiles of different NK/T cell subpopulations. Transcription factors such as ZNF835 and SOX21 are highly activated in NK cells, while other transcription factors like RARA and ZNF354C are highly activated in IL7R + DNT cells (Fig. 5f). GSEA analysis revealed distinct functional characteristics for each subpopulation. IL7R + DNT cells showed downregulation in immune response pathways, CD4 + Treg cells were involved in adaptive immune functions, and NK cells and CD8 + Teff cells exhibited enhanced cytotoxic function against tumor cells (Fig. 5g).

Subclustering of NK/T cell and myeloid cell. (a) UMAP plot of 1766 single cells from NK/T cells used for subclustering. (b) The proportions of identified NK/T cell populations in each tissue types. (c) Heatmap showing the ORs of NK/T cell clusters occurring in each tissue types. (d) UMAP plots showing the density of cells across different tissue types. (e) Dotplot of markers used for NK/T cell type identification. (f) Heatmap of differentially expressed transcription factors of NK/T cell subsets. (g) GSEA showing the enriched signaling pathway signatures in NK/T cell subsets. (h) UMAP plot of 18,939 single cells from myeloid cells used for subclustering. (i) Dotplot of markers used for myeloid cell type identification. (j) GSEA showing the enriched signaling pathway signatures in myeloid cell subsets.

The myeloid cell subpopulation (n = 18,939) was further subdivided into seven subgroups, including IL1B + macrophages, C1QC + macrophages, SPP1 + macrophages, FOLR2 + macrophages, CDC2 cells, SLC9A9 + macrophages, and MKI67 + macrophages, based on UMAP and characteristic gene expression (Fig. 5h, i). Proportional analysis across different tumor types showed that IL1B + macrophages were significantly enriched in pPA samples, suggesting a potential association with the tumor inflammatory microenvironment. rPA samples enriched for SLC9A9 + macrophages, while CXPA had the highest proportion of MKI67 + macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Pseudotime analysis revealed the dynamic evolution of MKI67 + macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 5c). GSEA analysis further showed that the macrophage subpopulations exhibited differentiated features in functional pathways related to immune response, metabolic regulation, and cell migration (Fig. 5j).

Changes in the intercellular communication network and identification of key ligand-receptor pairs

Cellular communication analysis was performed to compare the intercellular interaction patterns across pPA, rPA, and CXPA. The results showed that the number and strength of interactions in rPA samples were significantly higher than in pPA and CXPA, indicating a more complex intercellular communication network in rPA (Fig. 6a). The most significant differential interactions between groups were primarily observed between epithelial cells and myeloid cells, as well as between fibroblasts and other cell types (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Specifically, compared to pPA, rPA exhibited upregulation of interactions between myeloid cells and TFF3 + mucous cells (Fig. 6b). In contrast, compared to pPA, CXPA showed enhanced interactions between endothelial cells and basal cells (Supplementary Fig. 6b).

Intercellular communication displayed between tumor cell subsets. (a) Bar plots showing that pPA, rPA, and CXPA with different numbers and strengths of interaction based on CellChat. (b) Differences in the strength of interactions between tumor cell subsets, comparing rPA versus pPA, showing generally stronger interactions in rPA group. (c) Differences in the strength of input and output signals for each cell type in the different tumor groups. (d) Communication analysis showing the interactions between different cell types with myoepithelial cells as the input.

Further analysis of the strongest input and output signals for each cell type in the different groups revealed that in pPA, myeloid cells received the strongest input signals, and fibroblasts had the strongest output signals. In rPA, myeloid cells again received the strongest input signals, while chondrocyte-like epithelial cells had the strongest output signals. In CXPA, endothelial cells had the strongest input signals, and basal cells exhibited the strongest output signals (Fig. 6c). Analysis of differential ligand-receptor pairs showed that in CXPA samples, the MIF-(CD74 + CD44) signaling pathway between myoepithelial and myeloid cells was significantly active, which could be closely related to tumor microenvironment remodeling and immune modulation. Additionally, the FGF7-FGFR2 signaling pathway was active between fibroblasts and myoepithelial cells (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 6c).

Discussion

It is interesting to note that conventional histopathological classifications and molecular profiling are almost exclusively confined to benign PA. Whilst malignant transformation is recognized, there is a lack of research integrating benign and malignant backgrounds to map transformation trajectories, and little is known about its mechanisms. This study delineates the relatively comprehensive cellular and microenvironmental single-cell atlas spanning the entire transformation of PA, from primary lesions (pPA) to tumor recurrence (rPA) and malignant transformation (CXPA). By integrating scRNA-seq data from normal salivary glands, pPA, rPA, and CXPA, we uncover three pivotal mechanisms governing PA pathogenesis, including malignant specialization of the myoepithelial subpopulation, fibroblast-mediated stromal reprogramming, and immune-editing driven microenvironmental adaptation. Our data reveal that a subset of PAs harbors genomic instability signatures, which may create permissive conditions for malignant transformation. However, it is imperative that further functional studies be conducted in order to ascertain whether this instability is a driver or passenger event associated with tumor swamp.

While myoepithelial cells traditionally act as ‘gatekeepers’ by maintaining basement membrane integrity and secreting anti-invasive factors, their neoplastic transformation in CXPA correlated with pro-metastatic reprogramming25,26. Our study identified a malignancy-associated MIF + subpopulation within CXPA tumors, characterized by elevated MIF expression in myoepithelial cells. This subpopulation spatially colocalized with myeloid cells (p < 0.01), suggesting a phenotypic shift toward immune modulation.

The genomic landscape of PA epithelial cells revealed unexpected chromosomal instability. Our single-cell atlas further identified GALNT13 as a key marker defining a distinct pre-malignant myoepithelial subpopulation enriched in CXPA, with elevated expression quantitatively correlated with cell stemness (Fig. 2g). While PLAG1/HMGA2 rearrangements represented the molecular drivers of primary PA and were detectable in > 80% of benign tumors14,24,27,28, our identification of exclusively enriched GALNT13 + myoepithelial cells in CXPA highlights a novel genomic driver of malignancy. GALNT13-mediated aberrant glycosylation may disrupt cell polarity and cell‒cell adhesion to facilitate invasion29, while its coactivation with E2F likely drives cell cycle dysregulation suggesting a dual role in genomic instability and stem-like maintenance30,31. This finding aligns with the oncogenic cooperativity observed with mucin-like protein MUCL1 in breast and gastric cancers22,32,33. Collectively, it is hypothesized that GALNT13 + myoepithelial cells represent an acquired molecular phenotype driving PA transformation independently of PLAG1/HMGA2 status. This suggests their involvement in malignant transformation of PA, and their functional role in PA pathogenesis should be investigated. Future studies should test whether GALNT13 knockdown alters malignant phenotypes in vitro.

Trajectory analysis traced malignant myoepithelial lineages (GALNT13 +) to basal cell origins, mirroring developmental hierarchies in normal glands34. The exclusivity of GALNT13 + cells in CXPA, validated by external bulk RNA datasets, identifies them as malignant “switching” nodes, warranting investigation of their role in metastatic dissemination35.

Notably, while GALNT13⁺ cells demarcated the malignant transition state, a subset co-expressing MIF orchestrated stemness and immune-editing programs. MIF + myoepithelial cells, associated with CXPA and characterized by properties of cell stemness, EMT, and MYC, were identified by developmental trajectory, metabolic features, and key gene network analysis, respectively. Increasing studies have confirmed that MIF functions as a pivotal oncogene to promote proliferation and metastasis in various adenogenous malignancies, including breast cancer36, pancreatic cancer37, ovarian cancer38, gastric adenocarcinoma39, and lung adenocarcinoma40. It indicates that MIF + myoepithelial cells correlate with CXPA development, implicating MIF signaling as a biologically relevant pathway for further mechanistic exploration. However, further studies are needed to investigate the synergistic effects of other factors acting on MIF + myoepithelial cells in PA tumor microenvironment.

Fibroblast heterogeneity emerged as a critical determinant of PA development. COMP + fibroblasts dominated primary PA, engaging TGF-β/IL-17 pathways to promote fibrotic encapsulation—a phenomenon previously associated with indolent tumor behavior and a potential barrier against early dissemination34,41. In contrast, CXPA-enriched SFRP4 + fibroblasts activated PI3K-Akt and ECM-receptor pathways, facilitating stromal degradation and invasive outgrowth42. Notably, SFRP4 + fibroblasts exhibited FOXC2/GATA3 activation implying their role in therapy evasion43. Conversely, NR4A2/EGR1-driven COMP + fibroblasts may maintain tumor dormancy, offering a rationale for targeting fibroblast subtypes to prevent recurrence44. Pseudotime analysis revealed a differentiation trajectory from COMP + fibroblasts to LAMA2 + fibroblasts marked by Hippo pathway activation, suggesting mechanical stress via YAP/TAZ signaling drives stromal stiffening45, which is consistent with the calcification propensity in advanced PA46. The transcriptional shift from SOD3 to POSTN further highlights oxidative stress as a microenvironmental catalyst for malignant transformation47. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) drive tumor progression through ECM remodeling, paracrine signaling, and immune modulation, while simultaneously establishing physical/biochemical barriers, activating drug-resistance pathways, and inducing stem-like properties to confer therapeutic resistance48,49,50. Therefore, future research should comprehensively investigate the heterogeneity of CAFs in borderline tumors and identify their specific therapeutic targets.

CXPA displayed heightened NK cell cytotoxicity and CD8 + Teff activity, reflecting immune-editing “elimination-escape” dynamics, according to scRNA-seq data51. However, the dominance of MKI67 + macrophages and MIF-CD74/CD44 signaling in CXPA suggests a paradoxical pro-tumorigenic inflammation. This dual role of MIF in PI3K-AKT-mediated stemness and NF-κB-driven cytokine storms52 may create a self-reinforcing loop, enable immune evasion while fueling malignancy. Current literature confirms that PI3K-AKT activation is a recurrent feature in CXPA, driven by HER2 amplification, PTEN loss, and cancer stem cells (CSC) signaling53,54. While direct CXPA-specific trials are limited, mechanistic and preclinical evidence strongly supports the therapeutic relevance of this pathway55. Validation of PI3K-AKT activation as response predictors requires in vivo/vitro models to test target efficacy. Furthermore, immunosuppression characterized by IL7R + DNT cell hyporesponsiveness and SLC9A9 + macrophage expansion prevailed in rPA56. IL7R + DNT cells (CD4⁻CD8⁻ double-negative T cells) play a crucial role in immune regulation. Upon activation, these cells secrete inhibitory factors, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, which in turn downregulate the co-stimulatory molecules CD80/CD86 on dendritic cells. The dysfunction of these cells directly leads to immune suppression57. Concurrently, the expression of SLC9A9 (solute carrier family 9 member A9) in tumor-associated macrophages is closely associated with the immunosuppressive microenvironment58, thereby enhancing immune escape and promoting the recurrence of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma59. This immune “cold” microenvironment aligns with recurrence patterns in other cancers60, emphasizing the necessity for checkpoint inhibitors in rPA management. Our single-cell analysis revealed CD4 + Tregs predominate in PA, which is consistent with their established role in maintaining immune tolerance in benign tumors, and may also represent an active immunosuppressive mechanism that inhibits anti-tumor immunity61. These findings established immune microenvironment evolution as a hallmark of PA progression, with stage-specific therapeutic implications.

CellChat analysis uncovered stage-specific communication networks. The present study has demonstrated that enhanced epithelial‒myeloid interactions in rPA attributed to TFF3 + mucous cell‒macrophage crosstalk may propagate IL-1β/COX-2 signals to sustain chronic inflammation62. Correspondingly, endothelial-basal cell crosstalk via FGF7-FGFR2 in CXPA mirrors the mechanism of breast cancer metastasis63, suggesting stromal participation in angiogenesis. The MIF-(CD74/CD44) axis in CXPA myoepithelial cells may be hijacked as an immune checkpoint, and in glioblastoma, tumor cells utilize myeloid receptors to gain a survival advantage64. Altered ligand-receptor signaling in the PA microenvironment mirrors patterns observed in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma65,66. MIF + myoepithelial cells activate CD44 + macrophages, inducing PD-L1/IDO1 immunosuppressive phenotypes identical to PDAC stroma67. In PA, such pathways collectively establish an immunosuppressive niche that facilitates immune escape. GALNT13 + cell-derived IL-6 induces STAT3 phosphorylation in adjacent tumor cells, expanding CSCs as demonstrated in glioblastoma68. This suggests conserved stromal instructiveness underpins CSC expansion in PA transformation. While our single-cell atlas reveals analogous communication networks in PA, their functional impacts on immune evasion and stemness require direct experimental validation.

Further analysis of the strongest input and output signals for each cell type in the different groups revealed that in pPA, myeloid cells received the strongest input signals, consistent with their role as inflammatory sensors that respond to microenvironmental cues69. Concurrently, fibroblasts showed the strongest output signals, reflecting their known function in extracellular matrix remodeling and tumor-stroma crosstalk48. This pattern shifted in rPA, where sustained myeloid input signaling suggested persistent inflammatory stimulation70, while chondrocyte-like epithelial cells emerged as output signals, indicating activation of developmental programs associated with tumor plasticity71. Most strikingly, in CXPA we observed endothelial cells becoming the primary signal receivers, marking the angiogenic switch characteristic of malignant transformation72, while basal cells exhibited the strongest outgoing signals, consistent with their putative role as tumor-initiating cells driving aggressive behavior73.

In order to achieve the transition from fundamental research to clinical translation in PA, it is imperative to prioritize the establishment of patient-derived xenografts (PDX) model libraries for PA and CXPA. Furthermore, there is a requirement to combine genome sequencing data with drug sensitivity data to identify the key pathways driving malignant transformation. Concurrently, combined radiotherapy sensitivity testing and novel drug delivery systems, have the potential to overcome current therapeutic vulnerabilities74,75,76.

This study pioneers a novel framework to redefine the transformation of PA as a phased evolution from genomic instability to microenvironmental coordination. The atlas deciphers the hierarchical interplay of myoepithelial plasticity, stromal reprogramming, and immune editing during PA transformation. The identification of GALNT13 + and MIF + subpopulations reveals hitherto unrecognized molecular heterogeneity in CXPA. The correlation of these genes with stemness (GALNT13) and immune modulation (MIF) provides a framework for investigating aspects of malignant transformation. The hypotheses that GALNT13 may alter receptor glycosylation to promote invasion and that MIF facilitates immunosuppression through macrophage polarization must be tested using genetic manipulation in vitro before considering clinical translation.

However, there are limitations to this study. First, although single-cell sequencing provides high-resolution insights, small cohorts may limit the generalizability of the findings, necessitating validation in larger multi-center cohorts. Second, while pseudotime and functional analysis implicate GALNT13 + cells as tumor-initiating drivers, their definitive role requires functional validation in organoid models with GALNT13 knockout to assess invasion/metastasis phenotypes. This would also help to test the potential of GALNT13-targeted therapies. Third, the spatial resolution of fibroblast‒epithelial cell interactions remain unresolved, and the advent of spatial transcriptomic technologies may provide a glimpse into it. In addition, both CXPA cases in our scRNA-seq cohort shared similar histological subtypes (invasive myoepithelial carcinoma) and capsular invasion extent (≤ 1.5 mm), precluding comparative analysis of cellular and CNV heterogeneity across distinct pathological phenotypes. While we observed GALNT13 + myoepithelial expansion in both cases, the absence of histopathological diversity limited our ability to correlate molecular features with aggressiveness gradients. Furthermore, the CXPA and PA samples were derived from different individuals. Further studies with large sample and diversified CXPA subtypes are required to validate these findings against histological and clinical parameters, and to establish molecular-phenotypic correlations. Moreover, while GALNT13 and MIF are biologically compelling, their utility as biomarkers or targets requires in vivo confirmation in PDX trials. Thus, it is recommended that future research endeavors seek to validate the tumor-initiating capacity of GALNT13 + cells via patient-derived organoids and assess combinatorial targeting of MIF with immune checkpoint inhibitors77.

Materials and methods

Tumor specimen collection

Tumor specimens were collected from patients in the Department of Head and Neck Oncology, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University. The specimens included 1 labial gland tissue (LG), 1 parotid gland tissue (PG), 2 rPA, and 2 CXPA tissues. (Supplementary Table S2) Additionally, 1 PG tissue and 3 pPA were obtained from Hospital of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University (HRA003970). These tissue categories were systematically selected to establish multiple comparison groups that comprehensively cover the spectrum of PA-to-CXPA transformation characteristics, from benign neoplasia to malignant progression. The diagnosis for each case was confirmed by an experienced pathologist. All included CXPA cases met the WHO classification diagnostic criteria (5th edition, 2022)78, characterized by: (1) malignant cytological features arising in association with benign PA components, (2) demonstrable transition zones between benign and malignant areas, and (3) exclusion of other primary salivary malignancies. Representative histopathological features including infiltrative growth patterns and cytological atypia were documented for each case. None of the patients had received radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or any other anti-tumor treatments prior to surgery. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University (Document number: WCHSIRB-D-2022-213), and all research adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Tissue processing

Tissue specimens were kept on ice immediately after collection and then washed with PBS to remove residual blood and preservation solution. A uniform enzymatic digestion protocol was applied to all tissue types, using a mixture of 1 mg/ml neutral protease, 1 mg/ml collagenase types I, II, and IV, and DNase I. The tissues were finely minced with scissors and incubated at 37 °C with agitation at 160 rpm for approximately 30 min. Following digestion, the suspension was passed through a 40 μm cell strainer and centrifuged. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 3 ml of red blood cell lysis buffer and incubated at 4 °C for 5 min, followed by a second centrifugation. A 10 μl aliquot of the final cell suspension was stained with trypan blue and examined microscopically to assess cell viability and dissociation quality. Only samples with viability > 90% and minimal cell clumping were selected for single-cell library preparation. The digestion efficiency was approximately 70%.

Single-cell library preparation and sequencing

Single-cell suspensions with > 90% viability were loaded into the Chromium Single Cell Controller (10 × Genomics, v3.1) to generate gel bead-in-emulsion droplets, following the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting droplets underwent reverse transcription, cDNA amplification, and library preparation. Library quality was assessed before sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, generating 150 bp paired-end reads. Raw gene expression matrices were obtained by aligning reads to the human reference genome (hg38) using CellRanger (10 × Genomics).

Preprocessing of scRNA-seq data

Expression matrices from all samples were processed using the Seurat package (version 4.3.0) to generate Seurat objects. To ensure data quality, we excluded low-quality cells based on the following criteria: fewer than 200 detected genes (likely empty droplets), more than 5,000 genes (to remove potential doublets), or mitochondrial gene content exceeding 20% (indicating possible cellular stress or degradation). These thresholds are commonly applied in single-cell analysis workflows and help minimize technical artifacts. After filtering, a total of 91,545 high-quality cells were retained for downstream analysis.

Integration, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and cell annotation

To address batch effects across different patients, we employed Harmony (version 1.1.0) for batch correction. Initially, expression matrices were normalized using the NormalizeData function in the Seurat package (version 4.3.0). The FindVariableFeatures function was then applied to identify the top 2000 variable genes for principal component analysis (PCA). Data scaling was performed using the ScaleData function, and the first 50 principal components of the expression matrix were analysed with the RunPCA function. The first 25 principal components were selected for clustering based on the elbow plot and the proportion of variance explained, which ensured the inclusion of key biological signals while minimizing technical noise. Clustering was performed using FindNeighbors and FindClusters, and the results were visualized using two-dimensional uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP). Marker genes for each cell subgroup were identified using the FindAllMarkersMAESTRO function in the MAESTRO package (version 1.5.1). Manual annotation was independently performed by two researchers based on marker gene expression, and cross-referenced with the CellMarker 2.0 and PanglaoDB databases to reduce subjectivity.

Cell stemness analysis

The CytoTRACE scores for epithelial cells were calculated using the R package CytoTRACE (version 0.3.3). These scores, ranging from 0 to 1, reflect the relative differentiation status of individual cells, with higher scores indicating greater stemness and lower levels of differentiation. In this study, CytoTRACE results were used to identify progenitor-like epithelial subpopulations and to support trajectory analysis during tumor progression.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis were performed for upregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) within each cell subtype using the enrichGO and enrichKEGG functions of the clusterProfiler package (version 4.9.0)53. Statistical significance was assessed using the hypergeometric test to evaluate gene set overrepresentation, and p values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction, with adjusted p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

InferCNV and clonality analysis

Copy number variation (CNV) inference was performed using the inferCNV R package (version 1.12.0). The analysis input included the raw gene expression matrix and corresponding cell annotations, with epithelial cells from normal labial and parotid glands designated as the reference population. The analysis parameters were set as follows: cutoff = 0.1; denoise = TRUE to reduce technical noise; and HMM = TRUE to enable hidden Markov model–based CNV state prediction. CNV region visualization was performed using the ComplexHeatmap package (version 2.20.0). Expression values were log2-transformed, and colors were mapped to the range [−0.5, 0.5] to highlight relative expression changes associated with CNV gains and losses.

Gene set variation analysis (GSVA)

The GSVA package (version 1.44.5) was utilized to estimate pathway activity for individual cells based on scRNA-seq data. The pathways used in the enrichment analysis, specifically the Hallmark gene sets, were sourced from the MSigDB database. Pathway activity scores were then compared across cell subtypes to reveal functional differences and identify transcriptionally distinct cellular states.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

The “gseKEGG” function from the clusterProfiler package (version 4.9.0) was used to identify functional pathway states. This analysis revealed key pathway activations related to immune regulation, metabolism, cell cycle, and stress responses, enabling the characterization of distinct functional states within these cell populations.

Intercellular communication analysis

CellChat (version 1.4.0) was applied to explore potential cell–cell interactions within the PA tumor microenvironment (TME), using default parameters and the ligand-receptor pair database. Our analysis focused on interactions involving myoepithelial cells, fibroblasts, and immune populations. Notably, we identified the MIF–CD74/CD44 axis between myoepithelial and myeloid cells in CXPA, and the FGF7–FGFR2 pathway between fibroblasts and epithelial cells, both of which were implicated in microenvironmental remodeling and malignant progression.

PySCENIC analysis

The PySCENIC workflow (version 0.9.1) with default parameters was employed to identify gene regulatory networks (GRNs) and the activity of transcription factors (TFs). Distinct regulon activity patterns were observed across tumor stages. Specifically, KLF13 and NFIC were enriched in primary PA, SOX10 and MYBL1f. in recurrent PA, and MZF1 and BACH2 in CXPA, reflecting dynamic shifts in transcriptional regulation during malignant progression.

Pseudotime trajectory analysis

The Monocle R package (version 2.24.0) was employed to reconstruct the developmental trajectories of PA cells based on transcriptional dynamics. To complement this approach, the VECTOR algorithm was applied to infer the global directionality of cell state transitions in an unsupervised manner using UMAP embeddings. Specifically, the UMAP space was treated as a spatial grid, where each region was segmented and analyzed to identify directional flow based on connectivity patterns among neighboring pixels. By combining Monocle and VECTOR, we were able to cross-validate the inferred trajectories from both gene expression and geometric perspectives, enhancing the robustness of our lineage reconstruction.

Weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA)

WGCNA was used to characterize co-expression patterns within the dataset. We applied the hdWGCNA package (version 0.4.02) to construct gene co-expression networks, focusing specifically on myoepithelial cells using the scWGCNA workflow. The top 3,000 highly variable genes were selected for analysis. A signed adjacency matrix was generated with a soft-thresholding power of 6 to identify gene modules. Hierarchical clustering was then performed based on both gene dendrogram structure and module eigengene similarity.

Gene interaction network analysis

Functional interaction networks and gene association data were extracted from the STRING database. These interaction networks were then analyzed using the igraph package (version 1.3.4) to evaluate topological properties and node centrality. We applied edge betweenness and random walk algorithms to identify central genes within the network. Notably, key hub genes such as MIF, TGFBR3, and FN1 were identified, each corresponding to malignant, recurrent, and primary tumor features, respectively—highlighting their potential biological relevance in tumor progression.

Regulation submodule analysis based on connectivity specificity index (CSI) matrix

In this study, we utilized the CSI method to identify and analyze regulatory submodules, which quantify the relationships between transcription factors (TFs) and their target genes. We began by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficients (PCCs) of activity scores between pairs of regulatory factors. These values were derived from the RAS matrix, which was used to capture co-activity patterns. The CSI between any two transcription factors, A and B, was then defined by calculating the proportion of other regulatory factors with stronger correlations to A than to B. To identify regulatory submodules, hierarchical clustering based on Euclidean distance was applied to the resulting CSI matrix. Submodules showing the most significant inter-group differences were selected for further analysis.

Multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC)

Samples of pPA, rPA and CXPA tissues were collected at the West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at room temperature, followed by paraffin embedding, sectioning (4 μm), deparaffinization, and rehydration, according to standard protocols. Then, PA paraffin sections were subjected to four-color multiplex immunofluorescence staining using a commercial kit (AiFang Biological, Cat# AFIHC024) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were acquired using a fluorescence slide scanner. Image acquisition was done by selecting 5 non-overlapping fields per slide at 40 × magnification. Immunofluorescence quantification was performed using ImageJ v1.53 to calculate the co-localization cells percentage. All primary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:200, including MYLK (21642-1-AP, Proteintech), CK14 (10143-1-AP, Proteintech), MIF (A22623, ABclonal), TGFBR3 (bs-1910R, Bioss), FN1 (ET1702-25, Huabio), PLCG2 (27173-1-AP, Proteintech), and LAMA3 (83210-2-RR, Proteintech).

Statistics

Statistical analyses and data visualizations were generated using R software (version 4.1.3). The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for differential expression analysis, and the hypergeometric test with Benjamini–Hochberg correction was applied for GO and KEGG enrichment analyses. Pearson correlation was used in regulatory network analyses such as CSI. Statistical analyses of fluorescence quantification were performed via GraphPad Prism, version 9.3.1 using ANOVA. A significance level of adjusted p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Data availability

The single-cell sequencing datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the GEO datasets (accession number GSE294254) and GSA-Human (accession number HRA003970).

Abbreviations

- PA:

-

Pleomorphic adenoma

- CXPA:

-

Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma

- scRNA-seq:

-

Single-cell RNA sequencing

- TME:

-

Tumor microenvironment

- LG:

-

Labial gland tissue

- PG:

-

Parotid gland tissue

- pPA:

-

Primary pleomorphic adenoma

- rPA:

-

Recurrent pleomorphic adenoma

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- UMAP:

-

Uniform manifold approximation and projection

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- CNV:

-

Copy number variation

- GSVA:

-

Gene set variation analysis

- GSEA:

-

Gene set enrichment analysis

- GRN:

-

Gene regulatory networks

- WGCNA:

-

Weighted correlation network analysis

- CSI:

-

Connectivity specificity index

- mIHC:

-

Multiplex immunohistochemistry

- IMPA:

-

Invasive malignant pleomorphic adenoma

- MEC:

-

Myoepithelial cell

- CAF:

-

Cancer-associated fibroblast

- CSC:

-

Cancer stem cell

- MIF:

-

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- DNT:

-

Double-negative T cell

- SLC9A9:

-

Solute carrier family 9 member A9

References

Vrinceanu, D. et al. Parotid gland tumors: Molecular diagnostic approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25137350 (2024).

Piwowarczyk, K., Bartkowiak, E., Kosikowski, P., Chou, J. T. & Wierzbicka, M. Salivary gland pleomorphic adenomas presenting with extremely varied clinical courses. A single institution case-control study. Front. Oncol. 10, 600707 (2021).

Geiger, J. L. et al. Management of salivary gland malignancy: ASCO guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 1909–1941. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.00449 (2021).

Hernandez-Prera, J. C. et al. Pleomorphic adenoma: The great mimicker of malignancy. Histopathology 79, 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.14322 (2021).

Key, S. et al. Molecular factors in carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 134, 1042–1053. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.30993 (2024).

Wada, T. et al. Diagnostic performance and inter-operator variability of apparent diffusion coefficient analysis for differentiating pleomorphic adenoma and carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: Comparing one-point measurement and whole-tumor measurement including radiomics approach. Jpn. J. Radiol. 38, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-019-00908-1 (2020).

Witt, R. L. et al. Etiology and management of recurrent parotid pleomorphic adenoma. Laryngoscope 125, 888–893. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24964 (2015).

Altemani, A. et al. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (CXPA): Immunoprofile of the cells involved in carcinomatous progression. Histopathology 46, 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02157.x (2005).

Di Palma, S. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, with particular emphasis on early lesions. Head Neck Pathol. 7(Suppl 1), S68-76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-013-0454-z (2013).

Chen, W. et al. Extracellular matrix remodelling and stiffening contributes to tumorigenesis of salivary carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma–A study based on patient-derived organoids. Cell Biosci. 13, 122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-023-01071-x (2023).

Ma, S. et al. Some pleomorphic adenomas of the breast share PLAG1 rearrangements with the analogous tumour of the salivary glands. Histopathology 79, 1030–1039. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.14461 (2021).

Kim, H. et al. SLUG is a key regulator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pleomorphic adenoma. Lab. Invest. 102, 631–640. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-022-00739-1 (2022).

Egal, E. et al. Analysis of amplified genes in samples of pleomorphic adenoma and carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma by CGH-array technique. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 152, S51–S51 (2019).

Persson, F. et al. High-resolution genomic profiling of adenomas and carcinomas of the salivary glands reveals amplification, rearrangement, and fusion of HMGA2. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 48, 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.20619 (2009).

El-Naggar, A. K. et al. Molecular genetic alterations in carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma: A putative progression model?. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 27, 162–168 (2000).

Gerlinger, M. et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 883–892. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1113205 (2012).

Lewis, J. E., Olsen, K. D. & Sebo, T. J. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: Pathologic analysis of 73 cases. Hum. Pathol. 32, 596–604. https://doi.org/10.1053/hupa.2001.25000 (2001).

Aran, D. Single-Cell RNA sequencing for studying human cancers. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data. Sci. 6, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biodatasci-020722-091857 (2023).

Tirosh, I. et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 352, 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad0501 (2016).

Santos, A. A. D. et al. Immunohistochemical comparative analysis of tumor stem cell biomarkers in pleomorphic adenoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma of salivary glands. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. 135, 396–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2022.09.038 (2023).

Boutry, J. et al. The evolution and ecology of benign tumors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Rev. Cancer 1877, 188643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188643 (2022).

Stenman, G. et al. Chromosome translocations, gene fusions, and their molecular consequences in pleomorphic salivary gland adenomas. Biomedicines https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10081970 (2022).

Levyn, H. et al. Risk of Carcinoma in Pleomorphic Adenomas of the Parotid. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 149, 1034–1041. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2023.3212 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis uncovers the origin and intratumoral heterogeneity of parotid pleomorphic adenoma. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 15, 38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-023-00243-2 (2023).

Adriance, M. C., Inman, J. L., Petersen, O. W. & Bissell, M. J. Myoepithelial cells: good fences make good neighbors. Breast Cancer Res. 7, 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr1286 (2005).

de Lima-Souza, R. A. et al. Insights into the molecular alterations of PLAG1 and HMGA2 associated with malignant phenotype acquisition in pleomorphic adenoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 204, 104494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2024.104494 (2024).

Bahrami, A., Dalton, J. D., Krane, J. F. & Fletcher, C. D. A subset of cutaneous and soft tissue mixed tumors are genetically linked to their salivary gland counterpart. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 51, 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.20938 (2012).

Afshari, M. K. et al. The transcriptomic and gene fusion landscape of pleomorphic salivary gland adenomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 64, e70023. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.70023 (2025).

Pinho, S. S. & Reis, C. A. Glycosylation in cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 540–555. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3982 (2015).

Nahle, Z. et al. Direct coupling of the cell cycle and cell death machinery by E2F. Nat. Cell. Biol. 4, 859–864. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb868 (2002).

Hernando, E. et al. Rb inactivation promotes genomic instability by uncoupling cell cycle progression from mitotic control. Nature 430, 797–802. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02820 (2004).

Andreasen, S., von Holstein, S. L., Homoe, P. & Heegaard, S. Recurrent rearrangements of the PLAG1 and HMGA2 genes in lacrimal gland pleomorphic adenoma and carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. Acta. Ophthalmol. 96, e768–e771. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.13667 (2018).

Conley, S. J. et al. HER2 drives Mucin-like 1 to control proliferation in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 35, 4225–4234. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2015.487 (2016).

Oyelakin, A. et al. Transcriptomic and single-cell analysis of the murine parotid gland. J. Dent. Res. 98, 1539–1547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034519882355 (2019).

Fan, J., Zhang, Q., Huang, T., Li, H. & Fang, G. Identification of the CD8(+) T-cell exhaustion signature of hepatocellular carcinoma for the prediction of prognosis and immune microenvironment by integrated analysis of bulk- and single-cell RNA sequencing data. Transl. Cancer Res. 13, 5856–5872. https://doi.org/10.21037/tcr-24-650 (2024).

Yan, L. et al. Breast cancer stem cells secrete MIF to mediate tumor metabolic reprogramming that drives immune evasion. Cancer Res. 84, 1270–1285. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-2390 (2024).

Costa-Silva, B. et al. Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nat. Cell. Biol. 17, 816–826. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb3169 (2015).

Carvalho, R. F. et al. Single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing reveal ligands and receptors associated with worse overall survival in serous ovarian cancer. Cell. Commun. Signal 20, 176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-022-00991-4 (2022).

He, X. X. et al. Increased epithelial and serum expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in gastric cancer: potential role of MIF in gastric carcinogenesis. Gut 55, 797–802. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2005.078113 (2006).

Winner, M. et al. A novel, macrophage migration inhibitory factor suicide substrate inhibits motility and growth of lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 68, 7253–7257. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6227 (2008).

Lamouille, S., Xu, J. & Derynck, R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3758 (2014).

Nieto, M. A., Huang, R. Y., Jackson, R. A. & Thiery, J. P. Emt: 2016. Cell 166, 21–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.028 (2016).

Rhim, A. D. et al. Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 25, 735–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.021 (2014).

Di Martino, J. S. et al. A tumor-derived type III collagen-rich ECM niche regulates tumor cell dormancy. Nat. Cancer 3, 90–107. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-021-00291-9 (2022).

Panciera, T., Azzolin, L., Cordenonsi, M. & Piccolo, S. Mechanobiology of YAP and TAZ in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 758–770. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm.2017.87 (2017).

Nakamura, T. et al. A case of pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland with marked calcification. Japan. J. Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 48(5), 276–279 (2002).

Liang, X. et al. Oxidative stress is involved in immunosuppression and macrophage regulation in glioblastoma. Clin Immunol 258, 109802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2023.109802 (2024).

Kalluri, R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 16, 582–598. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2016.73 (2016).

Ringuette Goulet, C. et al. Exosomes induce fibroblast differentiation into cancer-associated fibroblasts through TGFbeta signaling. Mol. Cancer Res. 16, 1196–1204. https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0784 (2018).

Ben Hamouda, S. & Essafi-Benkhadir, K. Interplay between signaling pathways and tumor microenvironment components: A paradoxical role in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24065600 (2023).

Dunn, G. P., Old, L. J. & Schreiber, R. D. The three Es of cancer immunoediting. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22, 329–360. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104803 (2004).

Winner, M., Koong, A. C., Rendon, B. E., Zundel, W. & Mitchell, R. A. Amplification of tumor hypoxic responses by macrophage migration inhibitory factor-dependent hypoxia-inducible factor stabilization. Cancer Res. 67, 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3292 (2007).

Xia, L. et al. Human epithelial growth factor receptor 2 in human salivary carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: a potential therapeutic target. Cancer Manag. Res. 10, 6571–6579. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S182652 (2018).

Uro-Coste, E. et al. Malignant transformation in pleomorphic adenoma: The impact of DNA methylation profiling and pathogenic mutations. Mod. Pathol. 38, 100786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.modpat.2025.100786 (2025).

Glaviano, A. et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol. Cancer 22, 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-023-01827-6 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Transcriptome landscape of double negative T cells by single-cell RNA sequencing. J. Autoimmun. 121, 102653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2021.102653 (2021).

Gao, J. F. et al. Regulation of antigen-expressing dendritic cells by double negative regulatory T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 2699–2708. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.201141428 (2011).

Hao, N. B. et al. Macrophages in tumor microenvironments and the progression of tumors. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 948098. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/948098 (2012).

Weed, D. T. et al. The tumor immune microenvironment architecture correlates with risk of recurrence in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 83, 3886–3900. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-0379 (2023).

Sharma, P., Hu-Lieskovan, S., Wargo, J. A. & Ribas, A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell 168, 707–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017 (2017).

Wai, K. C. et al. The tumor microenvironment of benign and malignant salivary gland tumors. Head Neck 46, 1625–1636. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.27716 (2024).

Jung, Y. J., Isaacs, J. S., Lee, S., Trepel, J. & Neckers, L. IL-1beta-mediated up-regulation of HIF-1alpha via an NFkappaB/COX-2 pathway identifies HIF-1 as a critical link between inflammation and oncogenesis. FASEB J. 17, 2115–2117. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.03-0329fje (2003).

Mieczkowski, K. et al. FGF7/FGFR2-JunB signalling counteracts the effect of progesterone in luminal breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 16, 2823–2842. https://doi.org/10.1002/1878-0261.13274 (2022).

Chen, Z. & Hambardzumyan, D. Macrophage-tumor cell intertwine drives the transition into a mesenchymal-like cellular state of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 39, 743–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2021.05.003 (2021).

Mandal, R. et al. The head and neck cancer immune landscape and its immunotherapeutic implications. JCI Insight 1, e89829. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.89829 (2016).

Zhang, S. et al. Single cell transcriptomic analyses implicate an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer liver metastasis. Nat. Commun. 14, 5123. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40727-7 (2023).

Daunke, T. et al. Expression and role of the immune checkpoint regulator PD-L1 in the tumor-stroma interplay of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Front. Immunol. 14, 1157397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1157397 (2023).

Fu, W., Hou, X., Dong, L. & Hou, W. Roles of STAT3 in the pathogenesis and treatment of glioblastoma. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 11, 1098482. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2023.1098482 (2023).

Stegelmeier, A. A. et al. Myeloid cells during viral infections and inflammation. Viruses https://doi.org/10.3390/v11020168 (2019).

Gabrilovich, D. I. & Nagaraj, S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 162–174. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2506 (2009).

Qin, S. et al. Emerging role of tumor cell plasticity in modifying therapeutic response. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 5, 228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-00313-5 (2020).

Hanahan, D. & Folkman, J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 86, 353–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7 (1996).

Zhang, D. et al. Stem cell and neurogenic gene-expression profiles link prostate basal cells to aggressive prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 7, 10798. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10798 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Ethaselen synergizes with oxaliplatin in tumor growth inhibition by inducing ROS production and inhibiting TrxR1 activity in gastric cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 40, 260. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-021-02052-z (2021).

Turner, N. & Grose, R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: From development to cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2780 (2010).

Chen, A. M., Garcia, J., Bucci, M. K., Quivey, J. M. & Eisele, D. W. Recurrent pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland: Long-term outcome of patients treated with radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 66, 1031–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.036 (2006).

Yoon, Y. J. et al. Salivary gland organoid culture maintains distinct glandular properties of murine and human major salivary glands. Nat. Commun. 13, 3291. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30934-z (2022).

Skalova, A., Hyrcza, M. D. & Leivo, I. Update from the 5th Edition of the world health organization classification of head and neck tumors: Salivary glands. Head Neck Pathol. 16, 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-022-01420-1 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the authors who contributed to this topic.

Funding

Research and Develop Program of West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University (LCYJ2023-DL-1). Sichuan Provincial Natural Science Foundation Youth Fund (2024NSFSC1590). Chengdu Science and Technology Project Technology Innovation Research and Development Project (2024-YF05-00437-SN).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L. and C.W. conceptualized the study. Y.L. wrote the original manuscript. G.Z. analyzed the data and generated figures and descriptions. Z.L. and Q.H. curated the data and compiled and edited data figures and descriptions. C.L., C.W., and Z.D. were responsible for reviewing and editing the manuscript. C.L. and Z.D. obtained funding for the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Li, Z., Zhao, G. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals cellular evolution underlying pleomorphic adenoma recurrence and malignant transformation. Sci Rep 15, 35870 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19764-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19764-3