Abstract

The onset of turbulence in microsystems remains a fundamental scientific and engineering challenge due to the dominance of viscous forces at small confined scales. This study, therefore, experimentally demonstrates the concept of Turbulence-On-a-Chip by generating and characterizing turbulent-like flow regimes in microconfined environments under high-pressure transcritical conditions, without the addition of any external force or passive strategy. A custom-built microfluidic test rig is developed to operate with CO\(_2\) at supercritical pressures and controlled temperature differences. Flow behavior is analyzed through external flow visualization and 2D time-resolved \(\mu\)PIV, revealing distinct laminar and turbulent-like regimes for the conditions evaluated. Laminar-like cases exhibit organized flow patterns and parabolic velocity profiles, while turbulent-like cases display irregular speckle patterns, particle migration, and optical distortions, indicative of flow destabilization through density-gradient effects. Complementary, direct numerical simulations provide deeper insight into the multiscale flow fluctuations, supporting the experimental results. These findings establish a new framework for microconfined turbulence generation, with ground-breaking implications for microfluidic mass transport and energy transfer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decades, technological advancements have enabled the study of microscale phenomena and components with high precision. Microfluidics, in particular, has been established as a promising field due to its unique characteristics, such as high surface-to-volume ratios, flow controllability, and optimal scale for interacting with microscale elements. These features, coupled with the efficient use of materials and new manufacturing capabilities, have led to the development of numerous applications in a wide range of fields, including chemistry1, biology2, and biomedicine3. As a result, microfluidic systems have gained significant attention and have become an area of intense research. However, microfluidic applications related to energy transfer and propulsion, like for example micro heat engines and exchangers4, have long been a critical challenge in what some researchers refer to as “lab-on-a-chip and energy — the microfluidic frontier”5. The principal limitation is related to the small characteristic hydraulic diameters (\(D_h \sim 1-1000 \mu \text {m}\)) and bulk flow velocities (\(U_b \sim 1 \text {m/s}\)) of typical microfluidic devices. As a result, the Reynolds numbers obtained in microfluidics are in the order of \(Re_b = U_b D_h/\nu _b \sim 0.1-100\), where typical values of bulk kinematic viscosity at atmospheric pressure correspond to \(\nu _b \sim 10^{-6} - 10^{-4} \text {m}^{2}\text {/s}\). These low Reynolds values promote the presence of laminar flow for wall-bounded systems, which is directly linked to low efficiencies in fluid dispersion and energy transfer compared to turbulent flows.

Numerous approaches have been explored in microfluidics to enhance flow transport and homogenization. For instance, an important body of research has focused on manipulating laminar flows6 using strategies such as serpentine-like microchannel geometries. These designs do not alter the molecular diffusion coefficient, which is governed by intrinsic fluid properties, but instead enhance fluid exchange by modifying the flow field to induce secondary vortices, chaotic advection, or stretching and folding of fluid elements. Such mechanisms increase the interfacial area between streams, accelerating the homogenization process. While these designs may appear more complex, the fabrication process (often based on soft lithography) remains largely unaffected by channel geometry. Nevertheless, the resulting improvements in transfer rates are not always significant. Another approach significantly explored tries to achieve enhanced chaotic homogenization through electrokinetic forcing7,8. A different brute force strategy is to extraordinarily increase the volumetric flow rate to reach incipient turbulent flow conditions9,10,11. Although interesting for some applications, like high throughput liquid-liquid extraction and formation of emulsions12, this approach presents two main disadvantages: (i) there is no intrinsic mechanism to trigger flow destabilization, and (ii) the volumetric flow rates required are notably high in contradiction to the small rates typically sought in microfluidic applications. Finally, an interesting idea recently proposed to achieve turbulent regimes in microdevices is the utilization of flexible microfluidics13. At present, this promising technology has been demonstrated for devices in the millimeter-scale range and, consequently, further research is needed to reach microscale sizes.

This experimental work, instead, considers a drastically different approach to directly develop turbulent flow in microfluidic systems employing high-pressure transcritical fluids. As (computationally) explored by Monteiro & Jofre14, leveraging the hybrid thermophysical properties of supercritical fluids may have the potential to trigger sustained turbulent flow in microfluidic devices. As depicted in Fig. 1a , this strategy takes advantage of the rapid and smooth transition of supercritical fluids across the pseudo-boiling line, also known as the Widom line. This line is characterized by a peak of isobaric heat capacity at the pseudo-boiling temperature \(T_{pb}\) for the corresponding pressure P, delineating a boundary between supercritical liquid-like and gas-like fluid characteristics. By operating across this region, fluid properties can be adjusted to exhibit liquid-like densities (\(\rho \sim 10^3 \text {kg/m}^{3}\)) while maintaining gas-like viscosities (\(\mu \sim 10^{-5} \text {Pa}\cdot \text {s}\)). As a result, the kinematic viscosity increases by several orders of magnitude, raising Reynolds numbers to \(Re_b \sim 10^3\) as illustrated in Fig. 1b , making inertial forces overcome viscosity effects and resulting, thus, in turbulent flow at microconfined conditions. In this regard, the use of supercritical fluids is a mature field in thermo-fluid engineering as they are utilized in a wide range of applications, such as liquid rocket engines, gas turbines, and supercritical water-cooled reactors15,16. However, operating under high-pressure transcritical conditions to achieve turbulent regimes in microfluidic-based energy applications is a virtually uncharted area of research. In connection with this strategy, Zhang et al.17 explored transport intensification for antisolvent processes by operating at high pressures in free-shear coflow configurations at isothermal conditions. Nonetheless, the overall strategy is significantly different to the one studied in this work as: (i) jet flows are inherently unstable, and consequently, the laminar-to-turbulent transition occurs in the range \(Re_b \approx 30 - 2000\)18; (ii) coflows require complex microfluidic configurations; and (iii) isothermal conditions are not generally suitable for energy-related applications.

Supercritical CO\(_2\) fluid flow behavior in the vicinity of the critical point. (a) Thermophysical fluid properties of CO\(_2\) at critical pressure \(P_c = 7.38\) MPa as a function of reduced temperature \(T/T_c\) (critical temperature \(T_c = 304.13 \text {K}\)). Fluid properties are normalized with reference values obtained from the NIST database19, corresponding to critical density \(\rho _c = 467.60 \text {kg/m}^3\), critical viscosity \(\mu _c = 2.40\times 10^{-5} \text {Pa . s}\), critical thermal conductivity \(\kappa _c = 5.48\times 10^{-2} \text {W/(m . K)}\), and isobaric heat capacity at atmospheric boiling point \({c_P}_{\text {atm, bp}} = 850.85 \text {J/(kg . K)}\). The vertical-dashed black line denotes the critical temperature point (\(T/T_c\) = 1). Note that \(c_P/{c_P}_{\text {atm, bp}}\) extends beyond the plot range as it becomes asymptotically infinite at the critical point. (b) Colormap of Reynolds number Re at high-pressure transcritical conditions for \(D_h = 186.68 \mu \text {m}\) and \(U_b = 1 \text {m/s}\) as a function of reduced pressure and temperature. The yellow dashed curve denotes the pseudo-boiling line, where \(c_P\) values reach their maximum value for each pressure as a function of temperature. The thermodynamic state of cases B (turquoise circle), C (violet square), and D (green triangle) at the outlet (\(P_b/P_c\), \(T_o/T_c\)) are represented by colored symbols.

The principal objective of this work is, thus, to experimentally demonstrate the feasibility of achieving sustained microconfined turbulence by means of utilizing high-pressure transcritical fluids, which is a novel concept coined as Turbulence-On-a-Chip. To this end, as described in the Methods section, a new experimental test rig has been designed and mounted to work with microfluidic systems utilizing CO\(_2\) at supercritical pressures under temperature differences across the pseudo-boiling region. In detail, external flow visualizations coupled with 2D time-resolved microparticle image velocimetry (2D TR \(\mu\)PIV) measurements are utilized to experimentally demonstrate the appearance of turbulent flow behavior. External flow visualization warrants the detection of general flow circulation, while 2D TR \(\mu\)PIV is leveraged to obtain high-resolved spatio-temporal measurements of the flow dynamics. However, both methods require direct optical access to the flow, restricting the application to fully transparent microfluidic devices. In this regard, this study uses an off-the-shelf glass microchannel to ensure the measurement feasibility while maintaining the integrity of the high-pressure microsystem. In order to complement the experimental findings, direct numerical simulation (DNS) analyses are performed under the same thermophysical conditions, allowing an explicit comparison between experimental observations and computational predictions. These simulations provide deeper insight into the regions where experimental data acquisition is challenging due to optical constraints. Further details on the experimental setup, flow physics modeling, and computational framework utilized are provided in the Methods section.

Results

This section presents the findings obtained in this study. The experimental results include external flow visualizations, \(\mu\)PIV measurements using microparticles, and flow characterization with fluorescent dye, providing insights into the observed flow regimes. The computational analysis consists of DNS replicating the experimental conditions, offering complementary representations of velocity, temperature, and density fields. Together, these results provide a comprehensive understanding of the microconfined flow behavior under high-pressure transcritical conditions.

Experimental results

Microconfined supercritical turbulence is experimentally investigated under the conditions defined in Table 1. All cases are conducted at a fixed hydraulic diameter \(D_h = 186.68 \mu \text {m}\) and bulk velocity \(U_b = 1 \text {m/s}\), using CO\(_2\) with \(10\%\) ethanol in volume, and maintaining a cold-bottom wall temperature of \(T_{cw}/T_c = 0.98\). The system bulk pressure \(P_b/P_c\) is maintained and controlled across each experiment, while the microchannel top wall is heated to a temperature \(T_{hw}\) above the critical CO\(_2\) temperature. More information about the equipment and procedure utilized for the experiments is explained in the Methods section. Case A represents a standard flow at atmospheric pressure conditions (\(P_b / P_c \ll 1\)), which serves as a reference case. On the other hand, case B is a high-pressure transcritical fluid reference case in which \(P_b / P_c > 1\) and \(T_{hw} / T_c > 1\). Cases C and D are derived from case B, with increased pressure for C and reduced hot-top wall temperature for D, allowing the system to be studied under different working conditions close to the pseudo-boiling line. In addition, Table 1 also shows the experimentally settled inlet \(T_i\) and measured outlet \(T_o\) temperature at steady-state conditions with the fluid phase state determined at the microchannel outlet. Furthermore, dimensionless numbers are evaluated at the corresponding bulk pressure and median fluid temperature \(T_{m} = (T_i + T_o)/2\), using the NIST database19 to determine the values of the necessary properties. The resultant dimensionless numbers indicate that: (i) gravitational effects are negligible due to the high Froude numbers obtained (\(Fr_b \approx 23\)); (ii) acoustic/compressibility effects are not important as Mach numbers are of order \(M\!a_b \sim 10^{-3}\); and (iii) the Brinkman number, which characterizes the ratio of heat produced by viscous dissipation and heat transported by molecular conduction, remains in the same order of magnitude across all cases. However, a significant variation in the bulk Reynolds number is reported, increasing from \(Re_b \approx 170\) for case A to \(Re_b \gtrsim 2000\) for the high-pressure cases. This Reynolds number increment is attributed to density-viscosity decoupling for supercritical fluids operating across the pseudo-boiling region20. Such changes suggest a potential transformation in flow behavior, which is the primary focus of this investigation.

This study employs multiple techniques to characterize the flow regime under the experimental conditions determined. In particular, Fig. 2 presents close-in images captured with an external CMOS camera, providing a close view of the experimental section under steady-state operating conditions. The materials within the pictures are labeled according to the representation in Fig. 9, in which the chip holder is a stainless-steel gray frame, housing the glass microfluidic chip. Inside the holder window, the microchannel is visible and embedded in the glass chip following a serpentine-like pattern marked in yellow. Moreover, a copper heat conductor is attached to the opposite face of the chip, serving as a heat source. The working fluid flows left to right as indicated by the red arrow, and key differences between cases are outlined in green/magenta. In cases A and D, Figs. 2a and 2d , the microchannel remains optically clear, with no observable transformations or variations in the fluid. In contrast, a distinct “white region” emerges centered in the microchannel for case B (Fig. 2b ) and at the mid-to-end section for case C (Fig. 2c ). This white region corresponds to the critical opalescence zone and emerges while supercritical CO\(_2\) undergoes a second-order phase transition across the pseudo-boiling line near the critical point21. This transition zone encompasses the cluster formation region, where CO\(_2\) molecules show particular dynamics, aggregating and behaving diffusively at the liquid-like zones while presenting ballistic conduct at the gas-like regions22. Such transformations promote density variations, which are maximum at the opalescent zone23, making the refractive index behave non-linearly at the transcritical transition24. Particularly, as computationally explored by Monteiro & Jofre14, this localized density variation induces a baroclinic-type torque that promotes flow destabilization, enabling the appearance of turbulent flow regimes at lower Reynolds numbers than expected for standard operating flow conditions. The location and intensity of the opalescence zone in the experiment are function of pressure and temperature, following the pseudo-boiling line. In case B, the opalescence region is centered within the microchannel, exhibiting an intense white color. At the same time, as pressure increases for case C, the onset of opalescence is delayed, and the white intensity diminishes. However, no visible “white region” is observed for case D conditions, which suggests that the applied heat flux is not powerful enough to trigger the CO\(_2\) transcritical transformation.

External flow visualization of the microchannel under the different experimental conditions studied. (a–d) CMOS camera images corresponding to cases A, B, C, and D, respectively. The material of the components and the flow direction are labeled for clarity. In addition, differences between cases are marked with green/magenta rectangles.

As discussed in a previous study20, a 2D TR \(\mu\)PIV system is utilized to capture the flow behavior within a selected microchannel section with fine spatial and temporal resolution. The experimental configuration remains consistent with Table 1, except for adding \(\mu\)PIV tracer particles in the ethanol part of the flow. Specifically, \(\mu\)PIV measurements rely on detecting fluorescent microparticles introduced into the working fluid, acting as passive flow tracers. In addition, to ensure the particles accurately follow the fluid motion, the Stokes number, which computes the ratio between the particle relaxation time to the characteristic fluid time defined as \(St_b = \rho _p d_p^{2} U_b / (18 D_h \mu _{b})\) with \(\rho _p\) and \(d_p\) the particle density and diameter, respectively, must satisfy \(St_b \lesssim 1\). In the present study, tracer particles with a diameter \(d_p = 1 \mu \text {m}\) and density \(\rho _p = 1050 \text {kg/m}^3\) have been suspended in the ethanol fluid, resulting in a particle number density of \(n_p \sim 10^{14} \text {prt/m}^3\). Under these conditions, the Stokes number remains \(St_b \ll 0.1\) for all cases studied, ensuring tracing accuracy errors below \(1\%\)25. Finally, the measuring plane was positioned at \(z \approx 30 \mu \text {m}\) from the bottom wall, optimizing the signal-to-noise ratio for reliable image acquisition for all the cases, based on the optical system capability at the supercritical opalescent region for cases B and C.

Raw and post-processed \(\mu\)PIV results for cases A and D. (a, c) Representative instantaneous \(\mu\)PIV raw images for cases A and D, respectively, and (b, d) corresponding time-averaged velocity fields obtained via cross-correlation at \(z/D_h \approx 0.16\). Results are obtained by averaging a \(64 \times 64\) pixel interrogation window with \(50\%\) overlap over 200 images (100 pairs). The magenta curves correspond to the normalized time-averaged streamwise velocity profiles, while the yellow lines indicate the upper and lower boundaries of the microchannel corresponding to the lateral walls.

Figure 3 displays the \(\mu\)PIV results for cases A and D. The optically transparent behavior of the fluid at the measuring region, shown in Fig. 2, allows for standard system operation and reliable data acquisition. As a result, the \(\mu\)PIV system resolves tracer particles within \(4\times 4\) pixels26, appearing as small rounded dots against a dark background. As illustrated in Figs. 3b and 3d , data processing confirms a laminar-like regime, where the velocity exhibits a smooth distribution with a parabolic-like profile. The images have been obtained with a temporal resolution of \(\Delta t = 4 \mu \text {s}\) and processed using the cross-correlation method provided by the MicroVec software27. Cross-correlation was performed with an interrogation window of \(64\times 64\) pixels and \(50\%\) overlap over a total of 100 image pairs, resulting in a final spatial resolution of \(17.6 \mu \text {m}\times 17.6 \mu \text {m}\). The “large particles” observed in Fig. 3c correspond to out-of-focus particles, which appear enlarged due to image blurring during post-processing.

Differently, as depicted in Figs. 4a and 4c , \(\mu\)PIV measurements for cases B and C revealed the emergence of highly irregular speckle patterns. Speckle patterns are a well-documented optical phenomenon commonly observed in atmospheric measurements due to density variations, which affect light propagation through the medium28,29. Similarly, in this work, density fluctuations within the transcritical opalescent region modify the local refractive index, leading to deviations in the laser beam and microparticle reflection path, producing the observed speckle patterns at the camera plane. Since speckle patterns result from scattering by refractive index gradients, their dynamic, irregular appearance in these measurements reflects the intense, multiscale density and temperature fluctuations characteristic of the turbulent-like flow regime in the microchannel. Furthermore, as shown in Figs. 4b and 4d , the results also reveal particle agglomeration in the vicinity of walls, which can be linked to turbophoretic effects. Turbophoresis is a phenomenon in wall-bounded turbulent flows wherein particles migrate from regions of higher turbulence intensity (center) to lower-intensity (walls) ones due to differences in turbulent dispersion rates30,31. Due to the no-slip boundary condition, the turbulence intensity vanishes near the microchannel walls, creating a sharp turbulence gradient that drives the particles toward the walls. Once accumulated, these particles experience longer residence times at the near-wall region, resulting in a non-uniform particle distribution32,33. This effect is directly observed in the experiments, where the accumulation of particles at near-wall regions is identified as the appearance of quasi-static halos on the images, directly affecting the microchannel visualization. The observed halos result from light diffraction effects of out-of-focus particles, caused by the Z-plane difference between the particles and the \(\mu\)PIV focal plane34,35. Additional attempts with higher particle concentrations to achieve a more uniform particle distribution exacerbated the turbophoretic effects, leading to severe clogging of the microchannel and, in extreme cases, the rupture of the chip by an abrupt overpressure. Consequently, instantaneous velocity measurements utilizing cross-correlation could not be reliably applied due to: (i) inadequate particle detection within the opalescent region, where visualization is constrained by optical limitations; (ii) light distortion caused by density variations, resulting in irregular speckle patterns of the focused particles, reducing measurement reliability; and (iii) non-uniform particle distribution and progressive particle deposition on the microchannel walls due to turbophoresis, obstructing the visualization of tracer particles in motion. All the observed effects suggest the presence of a microconfined turbulent-like flow regime under the experimental conditions of cases B and C.

\(\mu\)PIV raw images showing irregular speckle patterns and turbophoretic effects for cases B and C. (a, c) Speckle patterns (green circles) observed in the recorded images, where distinct optical irregularities replace the normal appearance of individual tracer particles. (b, d) Turbophoretic effects manifested by halos corresponding to quasi-static particles accumulating in the vicinity of the microchannel walls.

Analogous to the discussion above, Fig. 5 presents \(\mu\)PIV observations of the experimental cases replacing microparticles by a fluorescent dye with similar fluorescent characteristics. The experimental configuration and \(\mu\)PIV setup remain unchanged, however, tracer microparticles have been replaced for a Rhodamine B fluorescent dye with a final concentration of \(C = 2 \mu \text {M}\); it is important to highlight, as discussed by Ross et al.36, that Rhodamine B fluorescence decreases with increasing temperature, making it an effective temperature probe but also introducing spatial fluorescence variability unrelated to concentration alone. The images illustrate notable flow differences between cases, following similar trends to the ones previously outlined. For cases A and D (Figs. 5a and 5d), the results depict a uniform fluorescence formation spanning the microchannel domain. Conversely, for cases B and C (Figs. 5b and 5c), the images exhibit significant optical disturbances, revealing a disordered media. As previously discussed, these distortions result from density/temperature fluctuations in a turbulent flow across the opalescent region, which introduce variations in the local refractive index. Consequently, the observed disturbances, together with the highly irregular speckle patterns, turbophoretic effects, and external flow visualizations, support the evidence of a turbulent-like flow regime in a microconfined environment for cases B and C.

\(\mu\)PIV raw images of the experimental cases employing Rhodamine B dye. (a–d) Flow visualization for cases A, B, C, and D, respectively, using Rhodamine B dye instead of microparticles. Cases A and D exhibit a uniformly illuminated field, indicating a uniform flow. In contrast, cases B and C display regions with significant optical disturbances.

Instantaneous DNS snapshots for the laminar-like cases corresponding to cases (a) A and (b) D. The left panels display the instantaneous normalized streamwise velocity \(u/U_b\) on an \(x/D_h - z/D_h\) slice at \(y/D_h = 0.67\). The right panels show the instantaneous normalized vertical velocity component \(v/U_b\) on a \(y/D_h - z/D_h\) slice at \(x/D_h = 6.5\). The magenta curves correspond to the normalized time-averaged streamwise velocity profiles. The results exhibit smooth velocity distributions characteristic of laminar-like flow.

Instantaneous DNS snapshots for the turbulent-like cases corresponding to cases (a) B and (b) C. The left panels present the instantaneous normalized streamwise velocity \(u/U_b\), and normalized temperature \(T/T_c\), on a \(x/D_h - z/D_h\) slice at \(y/D_h = 0.67\). The right panels display the instantaneous normalized vertical velocity component \(v/U_b\), and normalized density \(\rho /\rho _c\), on a \(y/D_h - z/D_h\) slice at \(x/D_h = 6.5\). The magenta curves correspond to the normalized time-averaged streamwise velocity profiles. The results indicate a turbulent-like flow regime characterized by disordered velocity fields, with \(v/U_b\) reaching magnitudes comparable to \(U_b\). Significant variations in temperature and density are also observed, where supercritical liquid-like and gas-like regions are distinguishable in the density field as \(\rho /\rho _c > 1\) and \(\rho /\rho _c < 1\), respectively.

Computational results

In parallel, DNS computations have been performed along with the experimental measurements to analyze the observed flow phenomena. These simulations provide deeper insight into the flow behavior, particularly in regions where data acquisition is limited by resolution and/or accessibility. The experimental cases have been reproduced computationally using the in-house flow solver REHA37,38, maintaining equivalent parameters to the experiments. Further details on the DNS configuration and solver details can be found in the Methods section. In this regard, Fig. 6 presents instantaneous DNS snapshots of normalized streamwise and wall-normal velocity components, \(u/U_b\) and \(v/U_b\), respectively, for cases A and D. The results display a laminar-like regime characterized by smooth and organized distribution of the flow fields with a parabolic streamwise velocity profile. Moreover, the wall-normal velocity components are several orders of magnitude smaller than the bulk velocity, typical of laminar flows. These findings coincide with the experimental \(\mu\)PIV measurements presented in Fig 3, where a laminar flow was determined. Instead, the results for cases B and C depicted in Fig. 7 show a turbulent-like flow regime, revealing chaotic multiscale structures with significant velocity and thermophysical fluctuations. In addition, wall-normal velocity magnitudes are only one order of magnitude smaller than the bulk velocity, indicative of strong cross-stream flow transport. Furthermore, the instantaneous density and temperature fields display irregular distributions, consistent with turbulence-induced thermo-fluid variations. Such variations would explain the experimentally obtained irregular speckles and turbophoretic effects (Fig. 4) and dye patterns (Fig. 5), as they are typical phenomena in high-density gradient turbulent flows.

To further support these findings, Fig. 8 presents, as a representative example of the turbulent-like cases, the power spectral density of streamwise velocity fluctuations (\(S_{u''u''}\), Fig. 8a) and temperature fluctuations (\(S_{T''T''}\), Fig. 8b) for case B, evaluated at the microchannel centerline. The velocity spectrum exhibits the characteristic energy cascade of turbulent flows, including a relatively short inertial subrange consistent with the classical \(-5/3\) slope39. Similarly, the temperature spectrum shows an energy cascade spanning from integral to dissipation scales. However, the inertial subrange is characterized by a gentler slope, close to \(-1\), in agreement with the observations of Grant et al.40.

Additionally, the DNS results facilitate the calculation of essential parameters utilized to characterize the flow regime. In particular, Table 2 displays representative bulk values of the root-mean-square Favre-averaged fluctuations of the velocity components normalized by bulk velocity \(u''_{rms_b}/U_b\), \(v''_{rms_b}/U_b\), \(w''_{rms_b}/U_b\), and temperature normalized by the temperature difference between top-hot and cold-bottom walls \(T''_{rms_b}/\Delta T_w\), with \(\Delta T_w = T_{hw} - T_{cw}\). For a generic variable \(\phi\), the Reynolds-averaged mean \(\overline{\phi }\) and its fluctuations \(\phi '\) are defined as \(\phi = \overline{\phi } + \phi '\) with \(\overline{\phi '} = 0\). Similarly, the Favre-averaged mean \(\widetilde{\phi }\) and its fluctuation \(\phi ''\) are defined as \(\phi = \widetilde{\phi } + \phi ''\), with \(\widetilde{\phi } = \overline{\rho \phi } / \overline{\rho }\). While the Reynolds approach is typically used for isothermal flows, the Favre approach is useful for removing the density fluctuation effects from the statistics of temperature-variable flows. The results indicate that velocity and temperature fluctuations are negligible or remain at low-magnitude orders for cases A and D, which is characteristic of laminar-like flows. Differently, cases B and C exhibit generalized higher fluctuations, with velocity fluctuations approaching the bulk velocity magnitude for the streamwise direction. Moreover, the normalized temperature fluctuations increase to approximately 2 and 2.5 for cases B and C, respectively, highlighting rapid thermal variations typically associated with turbulent-like flow regimes. Furthermore, Table 2 also presents the Nusselt numbers computed for the different walls, with \(Nu_{hw}\) for the hot-top wall, \(Nu_{cwo}\) for the cold-opposite wall, and \(Nu_{cwl}\) for the cold-lateral wall. The Nusselt number is a crucial parameter in thermal energy applications, as it quantifies the convection heat transfer relative to conduction. Given the significant influence of temperature on thermophysical properties, the Nusselt number is calculated in the form41

with the bar indicating local mean values. For cases A and D, \(Nu_w\) remains within the expected range for laminar-like flows, with values roughly between 1 and 1542. In contrast, for case B, \(Nu_w\) is increased \(2\times\) with respect to the laminar-like cases, whereas it is up to \(5\times\) larger for case C. These results are attributed to the higher fluctuations from the turbulent flow, which lead to more rapid homogenization of scalar quantities15,43. Similarly, comparing values obtained for the turbulent-like cases, higher values of fluctuations and Nusselt numbers have been reported for case C, indicating a more intense turbulent-like regime. This statement is supported by the DNS snapshots of Fig. 7, where more intense chaotic multiscale flow is perceptible for case C.

Discussion

These experiments demonstrate the feasibility of achieving microconfined turbulent-like flows under microfluidic conditions by employing high-pressure transcritical fluids. The flow regimes were characterized through a combination of in situ visualizations and quantitative 2D time-resolved \(\mu\)PIV measurements across multiple experimental cases. Under low pressure conditions, the flow exhibits laminar-like behavior, with velocity fields consistent with a parabolic profile and no observable density-induced optical distortions. In contrast, at high-pressure transcritical conditions, the flow becomes inherently unstable. Notably, despite operating at Reynolds numbers typically associated with laminar flow in confined geometries, the microsystem transitions to a turbulent-like regime, driven by strong thermophysical property gradients and the emergence of baroclinic torque. This regime is accompanied by highly irregular speckle patterns, turbophoretic particle migration, and complex dye structures, all of which coincide with elevated velocity fluctuations. As shown in Fig. S1 of section Visualization of instantaneous speckle patterns of the Supplementary Material, the speckle patterns fluctuate in both time and space. In detail, although the speckle patterns are caused by variations in the refractive index, their spatio-temporal dynamics directly correlate with the onset of chaotic, turbulent-like behavior. Finally, when the wall-to-wall temperature gradient is reduced, the baroclinic torque remains insufficient to destabilize the flow, and the system reverts to a laminar-like regime with patterns similar to those observed under low-pressure conditions.

To further examine the observed flow regimes, DNS results have been employed to complement the experimental findings. The simulations confirm the presence of a laminar-like flow regime in cases A and D, exhibiting parabolic-like velocity profiles aligned with the experimental ones. Moreover, low-velocity fluctuations and reduced Nusselt numbers are consistent with values of laminar-like regimes. In contrast, the DNS results of cases B and C reveal a turbulent-like regime characterized by chaotic behavior of the velocity and thermophysical fields, with observable multiscale chaotic structures and large fluctuations arising. Density fluctuations induce optical distortions in the measurements by altering the local refractive index, deviating the coherent laser light path, and resulting in the appearance of irregular speckle patterns. Furthermore, the resultant fluctuation magnitudes and Nusselt values are closer to the ones considered for turbulent-like flow regimes. Finally, DNS enables the comparison between the turbulent-like cases, with case C exhibiting higher velocity and temperature fluctuations as well as larger Nusselt numbers than case B, suggesting a more intense turbulent-like regime.

Future research should focus on refining these results by integrating alternative measurement techniques, optical and non-optical, to overcome the challenges associated with measuring high-pressure transcritical fluid flows. Additionally, the development of computational algorithms tailored for analyzing complex flow patterns, such as those encountered in speckle and dye-based visualizations, could provide deeper insights into the hidden dynamics. Furthermore, exploring different working conditions and geometric configurations could provide broader insights into the universality and optimization of the observed phenomena. Finally, it is important to highlight that, while the present study focuses on CO\(_2\) near its critical point, the underlying mechanisms responsible for the observed turbulent-like behavior (namely, strong thermophysical property gradients and baroclinic vorticity generation) could, in principle, be extended to other working fluids and geometries.

Methods

This section provides a detailed description of the experimental microfluidic setup, the flow physics modeling approach, and the computational framework utilized in this study.

Experimental microfluidic setup

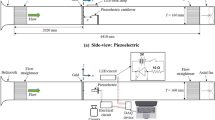

Experiments were conducted using a Micronit glass microreactor chip with the microchannel etched on it. The microchannel features a slotted cross-section with \(Y = 250 \mu \text {m}\) width and \(Z = 140 \mu \text {m}\) height, resulting in a hydraulic diameter of \(D_h = 186.68 \mu \text {m}\). It also extends a total length of \(L = 500 \text {mm}\) over the chip, arranged in a serpentine-like configuration. This microchannel was selected because it is designed to withstand high pressure while providing optimal optical access for \(\mu\)PIV data collection. To ensure stable and leak-proof operation under the required conditions, the microchannel was mounted in a Micronit Fluid Connect 4515 (FC4515) chip holder using the supplied fittings with stainless steel pipes of \(\text {OD} = 1/16 \text {in}\) and \(\text {ID} = 0.25 \text {mm}\). Despite its functionality, enhancements on the fittings were necessary to improve assembly reliability for high-pressure and high-temperature conditions. The fluid delivery system consisted of two Teledyne ISCO SyriXus 260x syringe pumps (A and B) and one Teledyne ISCO ReaXus MX-Class reciprocating pump. Pump A was connected to the microchannel inlet and configured for constant flow rate operation. Pump B was placed at the outlet and used to control the system pressure, operating in constant pressure. Additionally, the reciprocating pump was connected between Pump A and the microchannel via a T-junction and injected the fluorescent solutions into the system at a constant flow rate. Furthermore, the flow within the system was managed by two-way electrical solenoid valves HP13 from HPcontrol, rated to handle pressures up to \(150 \text {bar}\) and located at the inlet and outlet ports of the syringe pumps. These solenoids controlled the flow through the inlets and outlets of the Teledyne ISCO Syrixus 260x pumps, enabling either manual or automated operation via digital signals. In addition, to ensure the correct temperature at the top/hot wall of the microchannel, a heater system was attached to the top surface of the glass chip. This system is based on a \(20 \text {W}\) Peltier module with a hole through, a temperature controller, a heat conductor, and a heat sink. The Peltier was driven by a Wavelength Electronics PTC5K-CH PI temperature controller, calibrated for high responsiveness and stability to maintain a consistent heat flux. The heat conductor part corresponded to a small copper part mounted between the Peltier hot side and the chip top wall, serving as a heat source for the chip. The cold part of the Peltier module was maintained at room temperature with a passive aluminum heat sink. To minimize reflection and stray light interference during laser-based imaging, a small hole was drilled through the copper conductor, aligned with the optical axis of the microscope. Matching holes were also introduced in the Peltier module and the top aluminum heat sink to allow the laser beam to pass cleanly through the heater assembly. Moreover, the complete microchannel assembly (FC4515 + heater) rested on top of a second aluminum heat sink in direct contact with the chip bottom wall, ensuring the correct microchannel bottom/cold wall temperature. For the second heat sink, a microscope plate holder was redesigned and custom-manufactured to fit in the microscope stage, leaving enough space for the objectives and extracting the heat efficiently. A complete recreation of the system described is presented in Fig. 9.

Schematic of the experimental setup. Representation of the assembly used for the high-pressure transcritical flow experiments. The setup includes two high-pressure syringe pumps, A and B, and a reciprocating pump for fluid circulation. The \(\mu\)PIV system consists of an inverted microscope, a CCD camera, a laser, a synchronizer, and a computer. Pressure and temperature measurement points are indicated at the inlet and outlet of the microchannel, represented as I & O, respectively. Additionally, an external CMOS camera is used for flow visualization. A detailed cross-section of the microscope plate assembly is shown at the top-right corner, depicting the microscope objective lens, the microchannel, and the heating system, which consists of a Peltier module, a copper heat transmitter, and two aluminum heat sinks to ensure thermal stability.

The experimental measurements were then carried out as follows. First, the setup was fully assembled and checked to ensure the system was leak-free. Then, the \(\mu\)PIV measurement plane was carefully placed in the microchannel, and the hot-wall temperature setpoint was established. Next, the system was pressurized using the reciprocating pump, delivering plain ethanol to syringe pump B until the desired pressure (\(P_b/P_c\)) was reached. During this step, pump B operated in constant pressure mode, which adjusted the pump volume to control the system pressure. Once the target pressure was stabilized, the reciprocating pump was stopped, and its reservoir was replaced with the desired fluorescent-ethanol mixture. At this point, pump A, which was pre-filled with liquid CO\(_2\) at inlet conditions (\(P_b/P_c\) and \(T_i/T_c\)), was activated in constant flow mode, delivering \(90\%\) of the total flow corresponding to \(U_b = 1 \text {m/s}\) at the microchannel. Simultaneously, the reciprocating pump was set to deliver the remaining \(10\%\) of the flow rate with the required fluid-particle solution into the system. Once the system reached a steady-state working condition with the pumps, the temperature controller was turned on, heating the microchannel top wall to the required temperature (\(T_{hw}/T_c\)). After a few minutes, the top-hot wall temperature stabilized, and the CO\(_2\) entered the pseudo-boiling regime, visually confirmed by the appearance of the opalescent zone. At this point, simultaneous measurements of velocity, pressure, and temperature (Raspberry Pi data logger) were initiated.

External flow visualization of the microchannel was captured with a Canon EOS 550D camera equipped with an EFS 18-55 mm objective. To acquire the images presented in Fig. 2, the microchannel was assembled out of the microscope stage without the bottom heat sink to get optical access to the microchip. However, the remaining characteristics and system configuration were kept the same for the experiment development. The flow in the microchannel was captured and processed using a 2D TR \(\mu\)PIV system provided by MicroVec. The experimental setup consisted of: (i) a Nikon Eclipse Ti2-U inverted microscope equipped with epifluorescent filters, (ii) a MicroVec LPS-2000 laser, (iii) an Imperx Bobcat B2340 CCD camera, (iv) a signal synchronizer, and (v) a computer running MicroVec software. The microscope was equipped with a 20\(\times\) magnification extra-large working distance (ELWD) objective and an epifluorescent filter cube. Moreover, the laser was a Nd:YAG laser emitting light pulses of \(8 - 12 \text {ns}\) and wavelength of \(\lambda _E = 532 \text {nm}\) at \(30\%\) of the maximum energy (\(120 \text {mJ})\). Furthermore, the camera was a high-speed camera equipped with a \(4 \text {MP}\) sensor (\(2352 \text {pixels} \times 1768 \text {pixels}\)) with a pixel size \(\text {PS} = 5.5 \mu \text {m}\), capable of taking images with a time difference of \(dt = 1 \mu \text {s}\) working in PIV mode. The synchronizer interconnected the \(\mu\)PIV components, the laser, the CCD camera, and the custom-made data logger system to generate a synchronized trigger signal for the entire system. The system was driven by MicroVec software, which also provided the PIV post-process algorithm based on cross-correlation. The configuration resulted in a system qualified for taking measurements on a rectangular area of \(646.8 \mu \text {m} \times 486.2 \mu \text {m}\), with one pixel corresponding to \(0.275 \mu \text {m} \times 0.275 \mu \text {m}\), and a temporal resolution of \(\Delta t = 1 \mu \text {s}\). For the measurements, the window size was chosen to be \(64 \text {pixels} \times 64 \text {pixels}\) with an overlap of \(50\%\), according to the estimated velocity, resulting in a final spatial resolution of \(17.6 \mu \text {m} \times 17.6 \mu \text {m}\).

The microparticles employed were polystyrene spheres with diameter \(d_p = 1 \mu \text {m}\) and density \(\rho _p = 1050 \text {kg/m}^3\), coated in “firefli fluorescent red” fluorophore. These microparticles are manufactured by Thermo Fisher Scientific and presented in an aqueous solution at \(1\%\) of solid. In addition, to introduce them into the system, particles were diluted in ethanol to a concentration of \(0.033\%\), obtaining a final particle number density of \(n_p \sim 10^{14} \text {prt/m}^3\). Moreover, the dye used corresponds to Rhodamine B base, presented in powder, and manufactured by Sigma Aldrich. Similarly, Rhodamine B powder was diluted in ethanol to a concentration of \(2 \mu \text {M}\). The fluorescent characteristics of the substances were similar and matched the fluorescent filters introduced to the microscope, which allowed them to be recorded. The excitation peak for the microparticles and the dye was at wavelength \(\lambda _{Ex} = 542 \text {nm}\). In contrast, the emission peak for the microparticles was found at wavelength \(\lambda _{Em} = 545 \text {nm}\), while the one for the dye was at \(\lambda _{Em} = 612 \text {nm}\). Once the ethanol + particles solutions were obtained, they were introduced at the inlet port of the reciprocating pump.

To complement the velocity field measurements, the experimental setup included multiple pressure and temperature sensors to monitor conditions at various points of interest. Each pump had its measuring instruments, including pressure sensors, utilized to drive the pump mode and set the system configuration pressure and flow rate. Moreover, additional pressure and temperature measuring points were settled at the direct inlet and outlet of the microchannel, referred to as I&O in Fig. 9. These measurement points permitted the monitoring of the fluid properties at the closest point possible from the \(\mu\)PIV measuring point without direct intervention in the microchannel flow. Furthermore, it helped adjust the system working conditions to match them with the desired ones. Pressure measurements were taken by RS Pro piezoresistive pressure transducers, which have a range of \(0-250 \text {bar}\) and a tolerance of \(\pm 0.625 \text {bar}\). On the other hand, RS Pro K-type thermocouples were used for temperature sensing, which can measure temperatures up to \(+250^{\circ }\)C with a tolerance of \(\pm 1.5^{\circ }\text {C}\). In addition, the hot and cold wall temperatures were monitored and measured using the same thermocouples. These sensors were placed at the copper heat conductor module (hot side) and at the bottom aluminum heat sink (cold side) to ensure accurate measurements. All sensors were integrated with a Raspberry Pi 4b system built with Digilent MCC DAQ HAT boards, constructing a proficient and programmable data logger. Such construction provided real-time monitoring and allowed for synchronized \(\mu\)PIV measurements when connecting the synchronizer as a trigger signal. Thermocouples were connected to an MCC134 DAQ HAT, a specific board prepared to measure 4 thermocouples simultaneously with a 24-bit resolution. Moreover, the pressure transducers were captured via MCC128 DAQ HAT, a voltage measurement board offering up to 8 channels with a 16-bit resolution.

Flow physics modeling

The motion of high-pressure transcritical fluids is described by the conservation of mass, momentum, and total energy, which in dimensionless form are written as

where superscript \(\star\) denotes normalized quantities, t is the time, \(\textbf{u}\) is the velocity vector, \(\rho\) is the density, P is the pressure, \(\varvec{\tau } = \mu ( \nabla \textbf{u} + \nabla ^{\intercal } \textbf{u} ) - ( 2\mu /3 )( \nabla \cdot \textbf{u} ) \textbf{I}\) is the viscous stress tensor with \(\mu\) the dynamic viscosity and \(\textbf{I}\) the identity matrix, \(\hat{\textbf{e}}_g = (0, -1, 0)\) is the gravity unit vector, \(E = e + |\textbf{u}|^{2}/2\) and e are the total and internal energy, respectively, \(\textbf{q} = - \kappa \nabla T\) is the Fourier heat flux, \(\kappa\) is the thermal conductivity, and T is the temperature. The dimensionless equations are based on the following set of inertial scalings44,45

with subscript b indicating bulk quantities, \(\textbf{x}\) the position vector, \(D_h\) the hydraulic diameter, and \(U_b\) the time-averaged streamwise velocity. The resulting set of scaled equations includes three dimensionless numbers: (i) bulk Reynolds number \(Re_{b}=\rho _{b}U_{b}D_{h}/\mu _{b}\) characterizing the ratio between inertial and viscous forces; (ii) bulk Froude number \(Fr_b = U_{b} / \sqrt{g D_h}\), where g is gravity, relating the ratio between inertial and gravitational forces; and (iii) bulk Brinkman number \(Br_{b} = \mu _{b} U_{b}^{2}/( \kappa _{b} T_{b} )\), relating heat produced by viscous dissipation and heat transported by molecular conduction. The Brinkman number can also be expressed as \(Br_{b} = Pr_{b} Ec_{b}\) containing the bulk Prandtl number \(Pr_{b}=\mu _{b} {c_{P}}_{b} / \kappa _{b}\), where \(c_{P}\) is the isobaric heat capacity, quantifying the ratio between momentum and thermal diffusivity, and the bulk Eckert number \(Ec_{b} = U_{b}^{2}/({c_{P}}_{b} T_{b})\) accounting for the ratio between advective mass transfer and heat dissipation potential. In addition, for the flow cases considered in this work, the bulk Knudsen number \(K\!n_{b} = \Lambda /H \sim \mathcal{O}(10^{-6}) \ll 0.01\), where the molecular mean free path can be estimated as \(\Lambda = (k_B T_b)/(\sqrt{2} \pi P_b d_{\text {CO}_2}^2)\)46 with \(k_B = 1.380649 \times 10^{-23} \text {J/K}\) the Boltzmann constant and \(d_{\text {CO}_2} = 3.3 \times 10^{-10} \text {m}\) the particle hard-shell diameter for CO\(_2\), and consequently it can be assumed that the continuous fluid hypothesis holds true.

Moreover, the thermodynamic space of solutions for the state variables pressure P, temperature T, and density \(\rho\) of a monocomponent fluid is described by an equation of state. One popular choice for systems at high pressures is the Peng-Robinson47 equation of state. In general form, it can be expressed in terms of the compressibility factor Z, which in dimensionless form is written as

where \(\hat{\gamma } \approx Z (c_{P} / c_{V}) [(Z + T (\partial Z / \partial T)_\rho )/(Z+T(\partial Z / \partial T)_P)]\) is an approximated real-gas heat capacity ratio48 with \(c_{V}\) the isochoric heat capacity. As can be noted, the dimensionless bulk Mach number \(M\!a_b = U_b / c_b\) appears, where \(c_b\) is the bulk speed of sound, which represents the ratio of flow velocity to speed of sound. In addition, real-gas equations of state need to be supplemented with high-pressure thermodynamic variables (e.g., internal energy, heat capacities) based on departure functions49 calculated as a difference between two states. In particular, their usefulness is to transform thermodynamic variables from ideal-gas conditions (low pressure - only temperature dependent) to supercritical conditions (high pressure). The ideal-gas parts are calculated employing the NASA 7-coefficient polynomial50, while the analytical departure expressions to high pressures are derived from the Peng-Robinson equation of state as detailed, for example, in Jofre & Urzay15.

Finally, the high pressures involved in the analyses conducted in this work prevent the use of simple relations for the calculation of dynamic viscosity \(\mu\) and thermal conductivity \(\kappa\). In this regard, standard methods for computing these coefficients for Newtonian fluids are based on the correlation expressions proposed by Chung et al.51,52. These correlation expressions are mainly function of critical temperature \(T_c\) and density \(\rho _c\), molecular weight W, acentric factor \(\omega\), association factor \(\kappa _a\), dipole moment \(\mathcal {M}\), and the NASA 7-coefficient polynomial50; further details can be found in dedicated works, like for example Jofre & Urzay15 and Poling et al.53.

Computational framework

The equations of fluid motion previously introduced are discretely evolved in time utilizing the in-house flow solver RHEA37,38. A standard semi-discretization procedure is adopted whereby the equations are first discretized in space and then integrated in time. In particular, spatial operators are treated using second-order central-differencing schemes, and time-advancement is carried out with an explicit third-order strong-stability preserving (SSP) Runge-Kutta approach54 coupled with an artificial compressibility method (ACM)55. The convective terms are expanded according to the Kennedy-Gruber-Pirozzoli (KGP) splitting56 method, which has been recently extended to high-pressure transcritical fluids57. The method implicitly preserves the kinetic energy of the convection term and is locally conservative for mass, momentum, and total energy. This numerical scheme provides stable computations without resorting to artificial dissipation or stabilization techniques. Detailed validation of the thermophysical model and flow solver against highly recognized experimental databases, such as NIST19, can be found in previous works14,58,59.

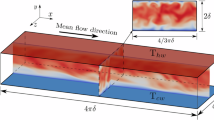

Figure 10 shows the computational domain utilized in this study to generate the simulated data with similar experimental dimensions and conditions. The domain consists of a duct with a rectangular cross-section designed to examine various thermodynamic conditions and flow regimes while preserving microfluidic characteristic dimensions and bulk velocity. The duct has dimensions based on the hydraulic diameter of \(D_h = 186.68 \mu \text {m}\) and measures \(13 D_h \times 1.34 D_h \times 0.75 D_h\) in the streamwise (x) and wall-normal (y, z) directions. The streamwise flow is directed from left to right with a bulk velocity of \(U_b = 1 \text {m/s}\), regulated by a body force through a proportional feedback loop with a gain of \(k_p = 0.1\), ensuring the deviation from the target value remains below \(0.5\%\) in all cases. Periodic boundary conditions are applied in the streamwise direction to represent a long microduct relative to the y and z directions, while no-slip conditions are imposed on the horizontal (x-y planes) and vertical (x-z planes) boundaries. The fluid used in all the cases is CO\(_2\), corresponding to the one used in the experiment, which is widely utilized in propulsion and energy-related applications60. The fluid system is analyzed at atmospheric (subcritical-superheated steam) and high-pressure (supercritical) bulk pressures, with values of \(P_b/P_c = 0.1\), 1.05, and 1.20. The system is confined between isothermal walls, with two different temperatures: the top hot wall (hw, red) and the lateral and opposite cold walls (cwl and cwo, respectively, blue). The temperatures at the cold and hot walls are set as \(T_{cwl}/T_c = T_{cwo}/T_c = 0.98\), and \(T_{hw}/T_c = 1.05\) or 1.10, based on each particular case studied. The domain is discretized with a uniform grid of \(192\times 96\times 96\) points.

Representation of the computational domain utilized for the DNS simulations. The schematic illustrates the domain dimensions and highlights the thermal boundary conditions, with the top wall at temperature \(T_{hw}\), the lateral walls at \(T_{cwl}\), and the opposite wall at temperature \(T_{cwo}\).

As shown in Table 3, the resolution, defined by the first grid point \(y^+\) and grid sizes \(\Delta x^{+}, \Delta z^{+}\), is adequate to resolve the relevant flow scales for the four cases. In detail, the wall distance of the first grid point away from the hot, cold lateral, and cold opposite boundaries is around \(y^+ \approx 1\) for all cases, where the superscript \(^+\) indicates wall units. Wall units utilize the friction velocity \(u_\tau = \sqrt{\tau _w/\rho _w}\) and viscous length \(l_\tau = \nu _w/u_\tau\) as velocity and spatial scales for nondimensionalization, with subscript w indicating quantities evaluated at the wall, \(\nu _w=\mu _w/\rho _w\) the kinematic viscosity and \(\tau _w = \mu _w (\partial \widetilde{u}/\partial y)|_w\) the mean wall shear stress. In addition, the cell sizes in terms of \(\Delta x^{+}\) and \(\Delta z^{+}\) follow the recommendations proposed by Monteiro & Jofre61. For the temporal time stepping, a CFL number of 0.3 was selected. The simulation strategy started from a parabolic-like velocity profile with random fluctuations62, which was advanced in time to reach steady-state conditions after approximately 5 flow-through-time (FTT) units; based on the bulk velocity \(U_{b}\) and the length of the duct \(L_x/D_h = 13\), a FTT is defined as \(t_{\text {FTT}} = L_x/U_{b} \approx 2.45\times 10^{-3} \text {s}\). After the transient period, the flow was considered hydrodynamically and thermally developed, and therefore, flow statistics were collected for roughly 15 FTTs to ensure sufficient temporal convergence.

Data availability

The experimental and computational data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Moreover, the computational data used in this paper was generated by the open-source in-house flow solver RHEA, which is accessible at: https://gitlab.com/ProjectRHEA/flowsolverrhea.

References

Chen, J. et al. Replicating shear-mediated self-assembly of spider silk through microfluidics. Nat. Commun. 15, 38225234. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-44733-1 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. NOVAsort for error-free droplet microfluidics. Nat. Commun. 15, 9444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52932-z (2024).

Jeon, E. et al. Biporous silica nanostructure-induced nanovortex in microfluidics for nucleic acid enrichment, isolation, and PCR-free detection. Nat. Commun. 15, 38355558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45467-w (2024).

Karami, N. et al. Experimental characterization of the thermodynamic cycle of a self-oscillating fluidic heat engine (sofhe) for thermal energy harvesting. Energy Convers. Manage. 258, 115548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2022.115548 (2022).

Sinton, D. Energy: The microfluidic frontier. Lab Chip 14, 3127–3134. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4lc00267a (2014).

Hardt, S. & Schönfeld, F. Microfluidic Technologies for Miniaturized Analysis Systems (Springer US, 2007), 1st edn.

Wang, G. R., Yang, F. & Zhao, W. Microelectrokinetic turbulence in microfluidics at low Reynolds number. Phys. Rev. E. 93, 013106. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.93.013106 (2016).

Nan, K. et al. Large-scale flow in micro electrokinetic turbulent mixer. Micromachines 11, 813. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi11090813 (2020).

Sharp, K. V. & Adrian, R. J. Transition from laminar to turbulent flow in liquid filled microtubes. Exp. Fluids 36, 741–747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-003-0753-3 (2004).

Wibel, W. & Ehrhard, P. Experiments on the laminar/turbulent transition of liquid flows in rectangular microchannels. Heat Transf. Eng. 30, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/01457630802293449 (2010).

You, J. B. et al. PDMS-based turbulent microfluidic mixer. Lab Chip 15, 1727. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5LC00070J (2015).

Camargo, C. L. et al. Turbulence in microfluidics: cleanroom-free, fast, solventless, and bondless fabrication and application in high throughput liquid-liquid extraction. Anal. Chim. Acta 940, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2016.08.052 (2016).

Fallahi, H., Zhang, J., Phan, H.-P. & Nguyen, N.-T. Flexible microfluidics: fundamentals, recent developments, and applications. Micromachines 10, 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi10120830 (2019).

Monteiro, C. & Jofre, L. Flow regime analysis of high-pressure transcritical fluids in microducts. Int. J. Heat Mass Trans. 224, 125295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2024.125295 (2024).

Jofre, L. & Urzay, J. Transcritical diffuse-interface hydrodynamics of propellants in high-pressure combustors of chemical propulsion systems. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 82, 100877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2020.100877 (2021).

Yoo, J. Y. The turbulent flows of supercritical fluids with heat transfer. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 45, 495–525. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-120710-101234 (2013).

Zhang, F., Marre, S. & Erriguible, A. Mixing intensification under turbulent conditions in a high pressure microreactor. J. Chem. Eng. 382, 122859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.122859 (2020).

Lemanov, V. V., Terekhov, V. I., Sharov, K. A. & Shumeiko, A. A. An experimental study of submerged jets at low Reynolds numbers. Tech. Phys. Lett. 39, 421–423. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063785013050064 (2013).

Linstrom, P. NIST chemistry webbook, NIST standard reference database 69, https://doi.org/10.18434/T4D303 (1997).

Hurtán, E., Monteiro, C., Jofre, M., Casals-Terré, J. & Jofre, L. Data-informed characterization of spatio-temporal scales in experiments of microconfined high-pressure transcritical turbulence. Exp. Therm Fluid Sci. 159, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2024.111282 (2024).

White, J. A. & Maccabee, B. S. Temperature Dependence of Critical Opalescence in Carbon Dioxide. Ann. Phys 26, 287. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.26.1468 (1971).

Majumdar, A. et al. Direct observation of ultrafast cluster dynamics in supercritical carbon dioxide using X-ray Photon Correlation Spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 15, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54782-1 (2024).

Mareev, E. et al. Anomalous behavior of nonlinear refractive indexes of CO\(_2\) and Xe in supercritical states. Opt. Express 26, 18911. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.26.013229 (2018).

Mareev, E. I., Aleshkevich, V. A., Potemkin, F. V., Minaev, N. V. & Gordienko, V. M. Molecular Refraction and Nonlinear Refractive index of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide under Clustering Conditions. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 13, 1214–1219. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1990793119070261 (2019).

Tropea, C., John, F. & Yarin, A. Springer Handbook of Experimental Fluid Mechanics (Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2007).

Prasad, A. K., Adrian, R. J., Landreth, C. C. & Offutt, P. W. Experiments in Fluids Effect of resolution on the speed and accuracy of particle image velocimetry interrogation. Exp. Fluids 13, 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00218156 (1992).

Kähler, C.J. et al. Main results of the 4th International PIV Challenge. Exp. Fluids 57, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-016-2173-1 (2016).

Wang, M., Mani, A. & Gordeyev, S. Physics and computation of aero-optics. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 44, 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-120710-101152 (2011).

Jumper, E. J. & Gordeyev, S. Physics and measurement of aero-optical effects: past and present. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 49, 419–441. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-010816-060315 (2017).

Rizk, M. A. & Elghobashi, S. E. On the effect of particle image intensity and image preprocessing on the depth of correlation in micro-PIV. Phys. Fluids 28, 806–817. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.865048 (1985).

Brandt, L. & Coletti, F. Particle-Laden Turbulence: Progress and Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-030121- (2021).

Johnson, P. L., Bassenne, M. & Moin, P. Turbophoresis of small inertial particles: Theoretical considerations and application to wall-modelled large-eddy simulations. J. Fluid Mech. 883, https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2019.865 (2019).

Marchioli, C. & Soldati, A. Mechanisms for particle transfer and segregation in a turbulent boundary layer. J. Fluid Mech. 468, 283–315. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112002001738 (2002).

Barnkob, R., Kähler, C. J. & Rossi, M. General defocusing particle tracking. Lab Chip 15, 3556–3560. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5lc00562k (2015).

Wu, M., Roberts, J. W. & Buckley, M. Temperature Dependence of Critical Opalescence in Carbon Dioxide. Exp. Fluids 38, 461–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-004-0925-9 (2005).

Ross, D., Gaitan, M. & Locascio, L. E. Temperature measurement in microfluidic systems using a temperature-dependent fluorescent dy. Anal. Chem. 73, 4117–23. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac010370l (2001).

Jofre, L., Abdellatif, A. & Oyarzun, G. RHEA - an open-source Reproducible Hybrid-architecture flow solver Engineered for Academia. J. Open Source Softw. 8, 4637, https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.04637 (2023).

Abdellatif, A., Grau, J., Torres, R. & Jofre, L. OpenACC Acceleration of Parallel Direct Numerical Simulation of Turbulent Flows. J. Appl. Comput. Mech 11, 425–438, https://doi.org/10.22055/jacm.2024.47026.4646 (2025).

Pope, S.B. Turbulent Flows (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (UK), 2000), 1st edn.

Grant, H. L., Hughes, B. A., Vogel, V. W. & Moilliet, A. The spectrum of temperature fluctuations in turbulent flow. J. Fluid Mech. 34, 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112068001990 (1968).

Nemati, H., Patel, A., Boersma, B. J. & Pecnik, R. The effect of thermal boundary conditions on forced convection heat transfer to fluids at supercritical pressure. J. Fluid Mech. 800, 531–556. https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2016.411 (2016).

White, F. Heat Transfer (Addison-Wesley, 1984).

Barea, G., Masclans, N. & Jofre, L. Multiscale flow topologies in microconfined high-pressure transcritical fluid turbulence. Phys. Rev. Fluids 8, 054608. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevFluids.8.054608 (2023).

Jofre, L., del Rosario, Z. R. & Iaccarino, G. Data-driven dimensional analysis of heat transfer in irradiated particle-laden turbulent flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 125, 103198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2019.103198 (2020).

Jofre, L., Bernades, M. & Capuano, F. Dimensionality reduction of non-buoyant microconfined high-pressure transcritical fluid turbulence. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 102, 109169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2023.109169 (2023).

Dahms, R. N. & Oefelein, J. C. On the transition between two-phase and single-phase interface dynamics in multicomponent fluids at supercritical pressures. Phys. Fluids 25, 092103 (2013).

Peng, D. Y. & Robinson, D. B. A new two-constant equation of state. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 15, 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1021/i160057a011 (1976).

Firoozabadi, A. Thermodynamics and Applications in Hydrocarbon Energy Production (McGraw-Hill Education, New York (USA), 2016), 1st edn.

Reynolds, W. C. & Colonna, P. Thermodynamics: Fundamentals and Engineering Applications (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (UK), 2019), 1st edn.

Burcat, A. & Ruscic, B. Third millennium ideal gas and condensed phase thermochemical database for combustion with updates from active thermochemical tables. Tech. Rep., Argonne National Laboratory (2005). DOI: publications.anl.gov/anlpubs/2005/07/53802.pdf.

Chung, T. H., Lee, L. L. & Starling, K. E. Applications of kinetic gas theories and multiparameter correlation for prediction of dilute gas viscosity and thermal conductivity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fund. 23, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1021/i100013a002 (1984).

Chung, T. H., Ajlan, M., Lee, L. L. & Starling, K. E. Generalized multiparameter correlation for nonpolar and polar fluid transport properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fund. 27, 671–679. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie00076a024 (1988).

Poling, B.E., Prausnitz, J.M. & O’Connell, J.P. Properties of Gases and Liquids (McGraw Hill, New York (USA), 2001), 5th edn.

Gottlieb, S., Shu, C.-W. & Tadmor, E. Strong stability-preserving high-order time discretization methods. SIAM Review 43, 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1137/S003614450036757X (2001).

Abdellatif, A., Ventosa-Molina, J., Grau, J., Torres, R. & Jofre, L. Artificial compressibility method for high-pressure transcritical fluids at low Mach numbers. Comput. Fluids 270, 106163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2023.106163 (2023).

Coppola, G., Capuano, F., Pirozzoli, S. & de Luca, L. Numerically stable formulations of convective terms for turbulent compressible flows. J. Comput. Phys. 382, 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2019.01.007 (2019).

Bernades, M., Jofre, L. & Capuano, F. Kinetic-energy- and pressure-equilibrium-preserving schemes for real-gas turbulence in the transcritical regime. J. Comput. Physics 493, 112477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2023.112477 (2023).

Bernades, M., Capuano, F. & Jofre, L. Microconfined high-pressure transcritical fluids turbulence. Phys. Fluids 35, 015163. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0135388 (2023).

Abdellatif, A. & Jofre, L. Empirical heat transfer correlations of high-pressure transcritical fluids at low Reynolds numbers. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 231, 125837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2024.125837 (2024).

Khalesi, J. & Sarunac, N. Numerical analysis of flow and conjugate heat transfer for supercritical CO2 and liquid sodium in square microchannels. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 132, 1187–1199 (2019).

Monteiro, C. & Jofre, L. Resolution standards for direct numerical simulation of wall turbulence in high-pressure transcritical fluids. Phys, Fluids 36, 125184. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0244472 (2024).

Nelson, K.S. & Fringer, O.B. Reducing spin-up time for simulations of turbulent channel flow. Phys. Fluids 29, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4993489 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the European Union (ERC, SCRAMBLE, 101040379). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Formació de Professorat Universitari scholarship (FPU-UPC 2023) of Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya · BarcelonaTech (UPC) (Catalonia), and the SGR program (2021-SGR-01045) of Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalonia).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Enrique Hurtán: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft; Reda El Mansy: Conceptualization, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft; Marc Jofre: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing; Josep Farré-Llados: Investigation; Jasmina Casals-Terré: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing; Lluís Jofre: Conceptualization, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hurtán, E., El Mansy, R., Jofre, M. et al. Supercritical miniaturization of turbulence in microsystems. Sci Rep 15, 36494 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20583-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20583-9