Abstract

Electric Vehicles (EVs) are increasingly recognized as a fundamental component of intelligent transportation systems within smart city frameworks. Therefore, several studies in recent decades have been trying to improve the performance of EVs to maximize the benefits from their connection to the network. Machine Learning (ML) and data-driven methods are used for analyzing EV charging behavior to maintain significant improvements in the prediction and scheduling fields. Although many of these studies have relied on historical charging data to predict the EVs’ State of Charge (SoC) and Charging Available Time (CAT), influential features have often been overlooked. These features are represented in real-time distance, road characteristics (road type, traffic pattern, and events data), and weather data. This study proposes a novel multistage approach, based on a Feedforward Deep Neural Network (FDNN) that combines historical charging data with these influential features to predict both SoC and CAT. The proposed approach outperforms existing literature with SMAPE scores of 0.00044, 0.00018 and 0.00014, 0.00012 for initial, required SoC and CAT predictions, respectively. Through comparative analyses with prior studies on the same dataset, this research highlights substantial improvements in predictive accuracy. It underscores the significance of integrating influential features for the precise prediction of EV charging behaviors within smart transportation systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change and global warming have driven the rising trend of EVs. With traditional vehicles contributing significantly to high exhaust rates and carbon emissions, the widespread adoption of EVs is crucial to combat this pollution. Moreover, EVs play a vital role in peak shaving by utilizing their discharging process during peak periods. This research aims to provide a comprehensive investigation of EVs’ impact on reducing pollution levels and their effectiveness in peak shaving. The methodology involves rigorous data collection, statistical analysis, and modeling techniques to evaluate the environmental benefits and grid stability enhancement provided by EV integration; however, it is difficult to deny the continuous development of EVs in several fields. The research has begun in this field due to the importance of replacing traditional vehicles with EVs, which shows a comparison between them1. Then, the connection of EVs to the network is studied to determine the challenges as a result of EV integration. These challenges that appear because of the process of charging EVs are represented in increasing power losses and the peak power consumed. Also, the voltage deviation increases with the EV implementation2.

Although EVs are essential, challenges persist, such as EV owners depending on charging stations due to the lack of home charging opportunities for all users. Over-reliance on charging at stations causes more pressure on the network during peak times. Additionally, the integration of huge-scale EVs will impose restrictions on the networks, and Instability in power networks due to uncoordinated EV charging behavior. This research employs a methodical approach involving data analysis, and simulation studies to address these hurdles effectively. To overcome the spatial constraints limiting the expansion of charging stations for EVs, a strategic approach is imperative. Smart scheduling emerges as a viable solution, necessitating an in-depth comprehension of charging behaviors2. Coordinated charging entails gathering essential data such as arrival and departure times, trip frequency, distances traveled, charger type, and battery SoC. These features are meticulously analyzed in this study to devise an efficient scheduling framework. The study optimizes the utilization of existing charging infrastructure, minimizes peak power demands, and ensures EV connection to the grid without the need for extensive expansion of charging facilities.

The rapid advancement in EV technologies has gained significant attention from researchers and policymakers worldwide. So, frequent studies have been implemented to explore various EV aspects, including EV charging, discharging, or a combination of both3,4,5,6,7,8,9, battery development10, and economic issues11. This section aims to elucidate an overview of the existing literature on these topics, as illustrated in Fig. 1. In the rest of this section, a sample of research those are mentioned in Fig. 1 have been discussed as a general background, and then followed by the summary of related charging behavior prediction works.

Background

Charging of EVs has emerged as a critical issue in EV topics, which directly impacts the network stability and infrastructure. Several researchers have delved into this topic, investigating different aspects of EV charging infrastructure and methods. Studies such as in3 demonstrate a schedule for coordinated EVs charging through actual data to maintain customer satisfaction using a genetic algorithm of shorthand a multi-objective function to a single one using weighting factors. To overcome the network limitations, the fluctuations of load have been diminished. The optimization results illustrate that the power consumed difference between peak and valley is decreased by 22% from the stochastic charging. However, the financial aspects of EV charging were not investigated in3.

An optimal strategy for EVs charging has been introduced in4, which is based on AI. It depends on fast charging to reduce the electrical network stress through the duck curve smoothing. In5 optimal parking lots sizing and allocation is implemented on 69-bus, 33-bus, and 9-bus networks. Also, EVs’ availability is discussed comparing with previous methods, but it requires assuming different values for EVs’ charging power to avoid the uncertainty data problem. This uncertainty arises from several assumptions, including each EV’s charging power (15 kW), annual failure rate, battery capacity of 50 kWh, and V2G dispatch time.

Also, one of the key areas of research in the field of EVs is discharging. Discharging studies focus on optimizing the use of stored energy in EV batteries, as reported in6. A scheduling approach for EV charging/discharging is suggested to minimize the operating cost and the peak/valley difference. EV owners have other factors besides the charging/discharging prices factor, such as arrival and departure time, which determine the availability of the charging period. So, the dynamic time-of-use price used in6 to ensure uncertainty is not enough for the availability of EVs to feed the load through the discharging process.

Generally, the discharging topic has been classified into vehicle-to-vehicle, vehicle-to grid, or vehicle-to home (V2V, V2G, or V2H) as in7,8,9. In7 a comprehensive survey of thirty studies is introduced and compared in terms of control structure and other various factors. V2G framework is proposed in8 to mitigate the network challenges in meeting charging demand during peak. The suggested method in9 achieves regulation effects such as reducing and shifting the peak period to the off-peak period. The environmental and economic issues have also been enhanced.

Battery Enhancement is another critical issue in the EV field. The performance, capacity, and lifespan of batteries significantly impact the overall efficiency and usability of EVs. Researchers are continuously working on developing new battery technologies, improving energy storage capabilities, and enhancing battery durability. These advancements aim to address the limitations of current battery technology, such as battery degradation over time, restricted driving range, and extended charging duration. A lithium-ion battery is used as a sample to evaluate the performance of the method proposed in10. This method showed promising results compared to previous research, which tested under different conditions, such as ageing, noise, and temperature impacts.

Economic considerations also play a significant role in the adoption of EVs. Researchers have examined the economic feasibility of EVs, considering factors such as purchase price, operating costs, and potential government incentives. These studies help policymakers design effective incentive programs to promote their adoption. The suggested hybrid system based on renewable energy in11 may reduce the cost of EV charging stations and the environmental impact.

Related works (AI-driven EVs behavior analysis)

Recently, AI models have been used more widely in different fields to support the transition toward EV adoption. This shift aims to preserve the environment; so the challenges that affect the spread of EVs must be faced. So, research is interested in studying and predicting the EVs’ charging behavior, battery SOC, and also the spread of EVs in the market12. Some important factors affect EVs’ charging scheduling, such as weather, traffic, and predetermined and sudden events. This factor could be taken into consideration during EV behavior prediction. In13 charging infrastructure status for the next day could be predicted by ML. Also, the network status and high-load prices adaptation could be implemented. EVs’ travel behavior has been simulated using a multi-layer ML approach in14, where an optimal bidding model for EV service providers was also proposed.

SoC estimation has been a key focus in previous studies, such as in15,16,17,18. In15 the remaining driving range is estimated from the SOC that was predicted using SVR. MAE and R2 are used to evaluate the prediction results that depend on the dataset of EV drivers for two weeks. SOC prediction based on EVs battery historical dataset is proposed in16, where Mileage and EVs battery voltage, current, and temperature are used to train the LightGBM model. These EV batteries’ data were also used as input data for the prediction models that were implemented in17,18. The model of the LSTM neural network model with MLP that was executed in17 was evaluated through one evaluation parameter of MSE. The same parameter MSE is used beside MAE, and RMSE to evaluate the three implemented models of SVM, KNN, and GPR in18. In[19 extreme ML is proposed for online prediction of the lithium batteries’ SOC.

A four-time series is produced in20 by a Python-based tool that produces BEV profiles. It is called emobpy, which is based on empirical mobility statistics and customizable assumptions. EV mobility is the first time series produced that depends on some factors, such as driver type, daily trip number, and departure and step time. Trip location, destination, duration, and distance per trip must also be available. This first time series is used with driving electricity consumption, the second time series, charging station availability, and the charging strategy as the emobpy input to get the grid electricity demand for the fourth time series.

A model based on physics and graph attention has been suggested in21 to enhance the prediction of EVs charging demand under the dynamic price situations, which was evaluated through the use of over 18 thousand EVs as a dataset. It is undeniable that studying and predicting the impact of EV charging on the grid to avoid potential grid problems. Therefore, the power consumption of EV charging stations has been predicted through three different models in22, for two different states. Also, the charging station operation cost could be obtained from these prediction results.

Table 1 summarizes the important parameters for the related previous works on EV Behavior prediction. Moreover, a comprehensive comparison table is provided, which contrasts our proposed approach with a set of recently published studies on EV charging behavior prediction. This table highlights key aspects such as the methodologies employed, datasets used, performance metrics, and external factors. The comparison clearly demonstrates the strengths of our multistage deep learning approach, particularly in its ability to integrate both historical and real-time data, including distance, road characteristics, and weather data. In contrast, our approach achieves superior predictive accuracy, as evidenced by the remarkably low SMAPE scores for SoC and CAT predictions. This comparison underscores the novelty and effectiveness of our method, positioning it as a significant advancement in the field of EV charging performance prediction.

Research gap and paper contribution

The proposed work covered some of the weak points of previous EV research. These points can be summarized as:-.

-

EVs charging scheduling depending on unrealistic data as outlined in5.

-

Not-applicable assumption for long parking period as reported in23.

-

Neglecting the departure time in the charging scheduling process23.

The results for EV parameters prediction have been enhanced using the proposed prediction models. Although previous studies have applied ML for predicting state of charge, session duration and energy consumption, they primarily focused on using Historical Charging Data (HCD). But sometimes additional features were also incorporated. Motivated by these approaches, this work investigates the use of additional input features to spot their impact on the prediction accuracy.

The key contributions of this work are as follows:

-

(1)

A novel approach is proposed for predicting EV charging behavior (SoC and CAT) that incorporates HCD, traffic, and weather data.

-

(2)

A novel implementation-based FDNN architecture is proposed for SoC and CAT estimation.

-

(3)

Performance evaluation indices, i.e. Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (SMAPE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and coefficient of determination (R2) are presented for comparison.

-

(4)

The empirical analysis demonstrates that the proposed work, which incorporates additional data, significantly enhances the prediction accuracy compared with previous studies, which relied solely on historical charging information.

Paper organization

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 provides a detailed clarification of the proposed methodology, starting with a general overview of the proposed approach, followed by a description of the FDNN structure, and concluding with a discussion of the four-stage implementation. This is followed by the results, which are outlined and evaluated in Sect. 3. Section 4 presents the results’ discussion and comparison, while the conclusion is illustrated in Sect. 5.

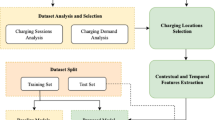

The methodology of the proposed prediction approach

The overall flowchart in Fig. 2 clarifies the implementation of the proposed FDNN prediction approach. The suggested prediction approach strategy utilizes a single FDNN. The goal of this network is to develop a prediction approach by accepting as input the normalized data of the selected BEV, including distance, road characteristics, and weather data.

The selected BEV model is the Tesla Model 3 (TM3). The nominal battery capacity (\(\:{N}_{Battery}=78.1\:kWh\)) is derived from manufacturer data24; all battery data are illustrated in Table 2. The EV charging scenarios have three main probabilities, which are charging at home, at stations, or in parking lots. The scenario of charging at home is the basis for the proposed work, where the charging period is the period between the arrival and departure times. TM3 can be charged according to manufacturing data by using a regular socket or a charging station. Charging time depends on the maximum EV’s capacity and the charging station features. EV charging differs by country; some countries use 1-phase connections to the network, while others use a 3-phase connection.

Table 3 illustrates the indications of the actual driving range under different conditions. The worst scenario represents the cold weather based at 10 °C, which requires heating. Hot weather of 35–40 °C, such as that in Egypt, is also considered among the worst scenarios. The mild weather is the greatest scenario based on 23 °C, which does not need A/C. A fixed speed of 110 km/h is assumed for the highway. The real range will depend on speed, driving mode, weather, and road type24.

The predictive scenarios studied

One of the most important parameters for EV charging scheduling is SoC. The proposed model is created to predict both the initial SoC (SoC-In) and required (SoC-Req). In addition to other parameters, arrival and departure times have been predicted, which are known as CAT. The following two scenarios illustrate the target for each prediction model, which is affected by the number of trips and the total distance for each EV.

First scenario (3 inputs & 2 outputs)

The first model is implemented using FDNN, which depends on three main input parameters to predict the values of SoC-In and SoC-Req. The three input parameters are the total distance for each EV trip number, weather temperature, and road type. The weather is classified as moderate or not, where the immoderate temperature represents the hot or cold weather. The road type may be city, highway, or combined road. Road type affects the speed, which also directly affects the energy consumption. So, the selected EV model data explain the differences in the total mileage according to the weather and road type, as previously mentioned in Table 3.

The initial SoC is predicted according to the total distance of trips on the previous day. However, the required SoC depends on the total distance of trips on the next day for each EV. The number of trips and distance of each trip have been stochastically distributed for all EVs according to the percentage in20. The road type and the weather condition represented in the ambient temperature are used as inputs with the total distance to enhance the model prediction results. Figure 3 illustrates the sequence of the proposed prediction model for the first scenario.

Second scenario (3 inputs & 4 outputs)

In this scenario, the predicted target is represented in the initial and required SoC, in addition to arrival and departure time. The same inputs of the first scenario are also used here to train the second model. The sequence of the second proposed model is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Detailed description of FDNN structure

An artificial neural network with more than one hidden layer of neurons between the input and output is referred to as a DNN25,26. ANN is a computational model capable of performing both ML and pattern recognition tasks27. DNNs are used to simulate complex nonlinear systems. Moreover, DNN computation is efficient because it involves solving basic algebraic equations. This feature enables DNNs to address issues promptly28,29,30.

The FDNN used in this study comprises an input layer with three neurons representing the features: distance, road characteristic, and weather data. Two fully connected hidden layers were implemented, consisting of 30 and 2 neurons, respectively, and activated using ReLU functions. The output layer includes two neurons corresponding to the predicted outputs: SoC and CAT, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

This multi-layered structure ensures non-linear feature extraction and robust learning capabilities, distinguishing it from simpler ML models. Unlike conventional ML models such as linear regression or single-layer perceptron’s, the FDNN architecture leverages multiple hidden layers and non-linear activation functions to capture complex relationships between diverse input features and output predictions. This enables superior generalization across heterogeneous input data. An FDNN can be considered a DNN under certain conditions. Specifically, the classification depends on the depth of the network. When the FDNN contains more than two hidden layers, it is classified as a DNN. The term “deep” reflects the increased depth of the network, which enables it to model complex data patterns and hierarchies. The distinction lies primarily in the depth of the architecture, not in the forward-pass structure of the network itself, as both shallow and deep networks can be feedforward in nature.

The premise behind the proposed FDNN prediction approach is that input features can quickly reveal their impact on the prediction accuracy. These input features include distance (Total distance for each EV’s trips), road characteristics, and weather data. Road characteristics are represented by road type, which could be city, highway, or combined roads, in addition to traffic patterns and events data. The weather data are represented by the ambient temperature, which could be mild or not mild (hot or cold). These data are fed into an FDNN for predicting charging behavior. The FDNN-based prediction approach is trained through these input data to predict EV parameters, which are the initial SoC (SoC-In), the required SoC (SoC-Req), and the charging available time.

Finally, the information produced can be utilized in decision-making processes for subsequent control operations, such as predicting the initial and required SoC and CAT. A FDNN consists of four main types of layers: input, hidden, softmax, and output layers. These layers are commonly used in data-driven prediction and diagnostic approaches. To confirm that all values lie within the range [0, 1], feature scaling is applied as follows, where (P) is the input vector: -

The following nonlinear transformation is used in the hidden layers to transform the input data into high-dimensional features. Here, \(\:x=(2,\dots\:,d)\), \(\:\bar{Y}\:\)is the hidden vector, \(\:\bar{y}\:\) is the bias vector, \(\:W\) is the weight matrix, and \(f\) is the activation function applied element-wise. The output of the final hidden layer is transformed using Eq. (2) without using the activation function given in Eq. (3).

The softmax function is used to determine the output value of each neuron, as in Eq. (4). Then the label with the highest output value is selected as the predicted label for the input data.

In the proposed work, the FDNN is used as a prediction framework. Its role is demonstrated through a comprehensive four-stage implementation, where each stage builds on the previous one to produce more reliable predictions, as outlined in the following sections.

FDNN prediction approach implementation

The proposed FDNN general structure is illustrated in Fig. 6, which consists of four stages:

-

1 st Stage: Dataset preparation.

-

2nd Stage: Input data preprocessing and normalization.

-

3rd Stage: Training of the feedforward deep neural network.

-

4th Stage: Performance metrics evaluation.

1 st stage: dataset preparation

The data taken from20 is used to generate a dataset for 1000 EVs. Also, we can produce data for any EVs sample size. These data are represented in the number of trips, trip distance, and trip duration time for each EV. Table 4 illustrates the percentage value of each EV’s trip number for both working and weekend days. These percentages are then applied to the 1000 EV dataset for the working-day scenario only, as it is considered more critical than the weekend case, as shown in Table 5.

After that, the number of trips is distributed for the whole number of EVs (N = 1000 EVs) randomly. The number of trips for working and weekend days are 2042, and 1450 respectively. The total number of trips is estimated using Eq. (5) for working days. The duration of each trip is distributed according to the trip distance of each EV. Then the distance and duration time are also randomly distributed according to Eq. (6).

where:

\(\:{{TT}_{N}}_{1}\)

Total No. of working days trips.

\(\:{t}_{n}\)

Trips No.

\(\:{{EV}_{n}}_{1}\%\)

Working days EVs No. for each number of trips as percentages.

\(\:N\)

Total EVs No.

\(\:{{T}_{N}}_{1}\)

Trips No. for working days at specific distances and times.

2nd stage: input data preprocessing and normalization

To generate a superior training environment, utilizing multiple datasets is highly effective. Six distinct cases for data input are employed using a combination of datasets and training models. The preprocessing of data involves cleaning and preparing the collected data by neglecting faulty data, outliers and inconsistencies, to enhance the model performance. In this work, we used standardization to convert the data to date-time objects to obtain the weather and road type for a particular charging record. This approach allows for the easy extraction of relevant information. Rather than determining the traffic level at a definite time, it considered the total traffic time through the day, enabling the model to identify the influence of traffic levels on charging performance. As well as performing normalization to confirm that the data are on a consistent format and scale, as given by Eq. (2).

The systematic approach used to integrate diverse data types ensures that the FDNN learns meaningful feature interactions rather than relying on simple concatenation. The process begins with a robust preprocessing pipeline, where continuous variables such as distance, road characteristics, and weather data are normalized to a uniform scale, and categorical variables like road types are encoded using methods such as embeddings. Embeddings, in particular, transform categorical data into dense numerical representations, enabling the model to capture complex relationships between categories, such as urban versus rural road characteristics. This fusion of data streams occurs at the input layer of the FDNN, where the architecture is designed to facilitate interaction among the preprocessed features. A detailed workflow diagram showcasing the preprocessing steps and a schematic representation of the FDNN’s structure are illustrated in Fig. 7, highlighting how the network processes and combines features to predict SoC and CAT.

3rd stage: training of FDNN for proposed prediction approach

The design of the FDNN structure requires careful identification of the type and number of layers, the number of neurons in each layer and the activation function used. In the proposed approach, a total of 1000 samples were considered for the FDNN design.70% (700 samples) were used for training, 15% (150 samples) were used for testing, and 15% (150 samples) were used for validation. Figure 8 illustrates how the data were split into training, validation, and test sets. Common architectures for prediction approach tasks include Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), such as LSTM networks.

Figure 9 shows the performance of the FDNN prediction model. From the regression plot shown in Fig. 9a, it is noticed that the regression value is equal to 1, indicating that the FDNN is accurately trained to identify the prediction values under study. The MSE is also very low, further demonstrating the model’s precision.

Moreover, Fig. 10 provides visual validation of the model’s performance, addressing the error metrics and model accuracy. Figure 10a provides the residual clustering plot, which illustrates the differences between predicted and actual values, with residuals tightly clustering around zero. This indicates minimal bias and suggests that the model accurately captures the relationships in the data without significant under-fitting or over-fitting. Figure 10b provides the scatter plot comparing predicted and actual values for both SoC and CAT. Points clustering closely along the ideal diagonal line signify high predictive accuracy. Separate plots for SoC and CAT further highlight the model’s ability to handle multiple output variables effectively. Figure 10c provides the predicted vs. actual value plots, showcasing the robustness of the model across diverse scenarios.

For SoC, the plot demonstrates consistency in accurately predicting battery states, which is crucial for EV efficiency. For CAT, the plot emphasizes reliable time estimations, which are critical for planning charging schedules. Together, these plots validate the model’s ability to generalize across varying input conditions. They provide strong evidence against over-fitting and substantiate the low error values reported, ensuring the reliability and practical applicability of the predictions in real-world scenarios. To address potential over-fitting, we employed cross-validation (5-fold cross-validation) and included regularization techniques such as dropout layers in the FDNN architecture to confirm that the low error metrics are consistent across different subsets of the data. The results confirm that the exceptionally low error values are due to the model’s high precision and not over-fitting.

4th stage: performance metrics evaluation

To evaluate the performance of predictions made by the FDNN model, various metrics are utilized, as discussed in10. In this study, five measures are defined, which are commonly used in related works to assess the SoC and CAT prediction results for the proposed FDNN model. Equations (9)–(13) outline the metrics used to evaluate this work, which are applied accordingly.

(i) Symmetric mean absolute percentage error (SMAPE):

(ii) Mean absolute error (MAE):

(iii) Mean Squared Error (MSE):

(iv) Root mean square error (RMSE):

(v) Coefficient of determination (R2):

In this context, \(\:{Y}_{a}\) is the real value while the predicted value is\(\:\:{Y}_{p}\), \(\tilde{a}\) is the mean of real values, and \(\:k\) denotes the groups of values in the dataset. Lower scores for RMSE, MAE, and SMAPE indicate accurate predictions, which occur when the predicted value \(\:{Y}_{p}\) is very close to the actual value\(\:\:{Y}_{a}\). The R2 value measures the goodness of fit for regression and typically ranges between 0 and 1. A score of 1 indicates perfect predictions, with higher values representing better performance30. The subsequent two sections present and analyze the results of the proposed approach, followed by a comparison with prior studies to demonstrate the approach’s effectiveness and contributions.

Results and evaluation metrics

The results have been evaluated using various metrics such as SMAPE, MAE, MSE, RMSE, and\(\:\:{\text{R}}^{2}\). Equation (9) to (13) outline the metrics used in this work, and these performance metrics will be evaluated accordingly. Table 6 illustrates the evaluation for the first and second proposed scenarios. The results of the first model are distinguished from the second model by a slight difference in accuracy due to several factors. In the first model, two parameters are deduced from three inputs, while in the second model, four parameters are deduced from the same three inputs. Therefore, to improve the results of the second model, more inputs can be added, or the outputs can be obtained separately by predicting the initial and required SoC as in the first scenario. Then, predict the other parameters of arrival and departure time.

Tables 7 and 8 show a sample of results, representing the predicted and targeted values. The initial and required SoC are the target outputs for the first scenario, while the second scenario has the target outputs of initial and required SoC, in addition to the charging available time. The weather and road conditions are illustrated in Tables 7 and 8 for each SoC value. The evaluation of the first scenario results is summarized in Fig. 11, while the evaluation of the second scenario results is summarized in Fig. 12.

Discussion and comparison

A systematic ablation study to evaluate the contribution of each input feature to the predictive accuracy of the model has been implemented. This process involved sequentially removing one input feature at a time and observing the resulting performance metrics, such as SMAPE, MAE, and RMSE, to determine how each feature impacts the overall prediction of the SoC and CAT. Table 9 summarizes the required SoC results of the second scenario, showing how the removal of individual features affects the model’s performance. Figure 13 illustrates a bar chart that shows normalized importance scores for each feature in terms of their contribution to SMAPE reduction.

The illustrated results in Table 9 and Fig. 13 show the effect of each feature, highlighting the importance of incorporating all contextual features to achieve robust prediction performance. The impact of these features can be formulated as follows:

-

Distance and road characteristics These factors had the most significant impact on predictive accuracy, particularly for the required SoC.

-

Weather and traffic patterns These factors were less influential individually but contributed to overall model performance when combined with other features, particularly for CAT.

-

Events data While events data had a smaller impact, it improved prediction accuracy in specific scenarios.

Additionally, scatter plots comparing predicted and actual values were used to visually validate the model’s performance as previously illustrated in Fig. 10, which validates model accuracy by showing how well predictions align with actual values. These Figures clearly indicate a consistent predictive ability across the test dataset. Also, to address potential over-fitting, we employed cross-validation and included regularization techniques such as dropout layers in the FDNN architecture. The results confirm that the exceptionally low error values are due to the model’s high precision, not over-fitting.

When comparing the proposed prediction approach across various metrics, considering the overall R2 and the SMAPE, it appears that predicting the SoC and CAT is particularly challenging. Moreover, across different scenarios, we observed that users’ self-predictions of their behavior often differed significantly from their actual performance, underscoring the need for predictive analytics. Compared to previous works, the results of this study outperformed all prior studies reporting similar evaluation metrics31,32,33,34,35.

Table 10 summarizes the results from these prior works in comparison to those achieved in this study. Specifically, for session duration, our results are more accurate than those in31. However, it is important to note that all previous work used a different dataset from the one used in this study, making direct comparisons potentially unsuitable. Nonetheless, when keeping the comparison within the same dataset, it is evident that the inclusion of additional road type and weather led to an enhancement in EVs’ charging performance prediction.

Finally, the FDNN’s novelty lies in its systematic data integration approach and specialized architecture, aspects that cannot be fully represented by comparing it to generic models. Highlighting its unique design and performance metrics adequately fulfills the study’s objectives. The research emphasizes the integration of diverse data types (e.g., distance, road characteristics, and weather data) and demonstrates its impact on prediction accuracy, rather than benchmarking against general models that may not be specialized for this context. Compared models may not be explicitly designed for the specific task of predicting both SoC and CAT, and adapting them could lead to suboptimal configurations or unfair evaluations. The effort to align existing models with the task might dilute the uniqueness of the proposed FDNN approach.

Conclusion

In the proposed work a framework is presented for predicting the most important EV charging behaviors related to scheduling, specifically EV state of charge and charging available time (arrival and departure times). Unlike previous studies, we incorporated additional features, such as distance, road, and weather data, in addition to HCD. FDNN was trained to predict charging behavior and examined how the hidden layers and the number of neurons in the final hidden layer impact the network’s performance. Furthermore, the limitations of our approach can be mitigated by employing careful feature selection and leveraging domain expertise to address these constraints effectively.

The first model was trained using three inputs to predict the initial and required SoC only. The results of this model were evaluated using accuracy and error metrics, showing promising outcomes. Specifically, the MSE was\(\:\:{1.8\text{*}10}^{-7}\), the MAE was 0.00013, and R² is unity. The second model also demonstrates promising results, consistent with the evaluation factors mentioned in previous works. The prediction performance of our models is superior to that reported in earlier studies. Furthermore, we have achieved significant improvements in predicting charging behavior using the HCD, which demonstrates the potential of incorporating distance, road characteristics, and weather data information into charging behavior prediction.

The future extension of this work can be considered as developing new models of ML methodologies with more features, such as an in-depth study of the factors affecting EVs’ performance. Consequently, the EV’s performance impacts on vehicle consumption and changes in initial and final SoC values. These factors include road angle, wind direction, and resistance. Furthermore, these methodologies could be applied to various types of EVs and compared to help users choose the most suitable type.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EVs:

-

Electric vehicles

- ML:

-

Machine Learning

- SoC:

-

State of Charge

- BEV:

-

Battery Electric vehicles

- DNN:

-

Deep Neural Network

- CAT:

-

Charging Available Time

- V2V:

-

Vehicle-to-Vehicle

- FDNN:

-

Feedforward Deep Neural Network

- MAE:

-

Mean Absolute Error

- V2H:

-

Vehicle-to-Home

- RMSE:

-

Root Mean Square Error

- V2G:

-

Vehicle-to-Grid

- SMAPE:

-

Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error

- MSE:

-

Mean Squared Error

- KNN:

-

K-Nearest Neighbours

- R2 :

-

Coefficient of Determination

- CNNs:

-

Convolutional Neural Networks

- RF:

-

Random Forest

- LSTM:

-

Long Short-Term Memory

- AI:

-

Artificial Intelligence

- SoC-In:

-

Initial State of Charge

- SVM:

-

Support Vector Machine

- HCD:

-

Historical Charging Data

- ANN:

-

Artificial Neural Network

- SL:

-

Session length

- RNNs:

-

Recurrent Neural Networks

- TM3:

-

Tesla Model 3

- SoC-Req:

-

Required State of Charge

References

Sanguesa, J. A., Sanz, V. T., Garrido, P., Martinez, F. J. & Barja, J. M. M. A review on electric vehicles: technologies and challenges. Smart Cities. 4(1), 372–404. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities4010022 (2021).

Mohamed, N. M. M., Sharaf, H. M., Ibrahim, D. K. & El’gharably, A. Proposed ranked strategy for technical and economical enhancement of EVs charging with high penetration level. IEEE Access. 10, 44738–44755. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3169342 (2022).

Tao, Y., Huang, M., Chen, Y. & Yang, L. Orderly charging strategy of battery electric vehicle driven by real-world driving data. Energy 193 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.116806 (2020).

Umar, J., Raul, J. A., Sara, A. & Yu-Fang, J. Artificial Intelligence-driven optimal charging strategy for electric vehicles and impacts on electric power grid. Electronics 14(7), 1471 (2025). https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14071471

Fathy, A. & Abdelaziz, A. Y. Competition over resource optimization algorithm for optimal allocating and sizing parking lots in radial distribution network. J. Clean. Prod. 264 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121397 (2020).

Wu, S. & Pang, A. Optimal scheduling strategy for orderly charging and discharging of electric vehicles based on spatio-temporal characteristics. J. Clean. Prod. 392 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136318 (2023).

Nimalsiri, N. et al. A survey of algorithms for distributed charging control of electric vehicles in smart grid. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 21(11), 4497–4515. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2019.2943620 (2020).

Liang, Z., Qian, T., Korkali, M., Glatt, R. & Hu, Q. A vehicle-to-grid planning framework incorporating electric vehicle user equilibrium and distribution network flexibility enhancement. Appl. Energy. 376 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124231 (2024). Part A.

Yao, Z., Wang, Z. & Ran, L. Smart charging and discharging of electric vehicles based on multi-objective robust optimization in smart cities. Appl. Energy. 343 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.121185 (2023).

Hannan, M. A. et al. Toward Enhanced State of Charge Estimation of Lithium-ion Batteries Using Optimized Machine Learning Techniques, Sci. Rep. 10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61464-7 (2020).

Faisal, S. et al. Reducing the ecological footprint and charging cost of electric vehicle charging station using renewable energy based power system. e-Prime - Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy. 7 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prime.2023.100398 (2024).

Afandizadeh, S. et al. Using machine learning methods to predict electric vehicles penetration in the automotive market. Sci. Rep. 13, 8345. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35366-3 (2023).

Hecht, C., Figgener, J. & Sauer, D. U. Predicting electric vehicle charging station availability using ensemble machine learning. Energies 14, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14237834 (2021).

Lin, J., Dong, P., Liu, M., Huang, X. & Deng, W. Research on demand response of electric vehicle agents based on multi-layer machine learning algorithm. IEEE Access. 8, 224224–224234. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3042235 (2020).

Eissa, M. A. & Chen, P. Machine Learning-based electric vehicle battery state of charge prediction and driving range Estimation for rural applications. IFAC-PapersOnLine 56(3), 355–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2023.12.050 (2023).

Jafari, S. & Byun, Y. Efficient state of charge Estimation in electric vehicles batteries based on the extra tree regressor: A data-driven approach. Heliyon 10(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25949 (2024).

Cao, H. et al. Research on the impact of lithium battery ageing cycles on a data-driven lithium battery model. World Wide Web. 28, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11280-024-01318-8 (2025).

Babu, D. O. P. Enhanced SOC Estimation of lithium ion batteries with realtime data using machine learning algorithms. Sci. Rep. 14, 16036. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66997-9 (2024).

Zhang, B. & Ren, G., Li-Ion Battery State of Charge Prediction for Electric Vehicles Based on Improved Regularized Extreme Learning Machine. World Electr. Veh. J., 14(8), 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj14080202 (2023).

Gaete-Morales, C., Kramer, H., Schill, W. P. & Zerrahn, A. An open tool for creating battery-electric vehicle time series from empirical data, emobpy. Sci. Data. 8 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00932-9 (2021).

Qu, H. et al. A physics-informed and attention-based graph learning approach for regional electric vehicle chargingdemand prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 25(10), 14284–14297. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2024.3401850 (2024).

Akshay, K. C. et al. Power consumption prediction for electric vehicle charging stations and forecasting income. Sci. Rep. 14, 6497. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56507-2 (2024).

Gnanavendan, S. et al. Challenges, Solutions and future trends in EV-technology: A Review. IEEE Access 12, 17242–17260. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3353378 (2024).

Tesla Model 3 Long Range Dual Motor. - Electric Vehicle Database. https://ev-database.org/car/1992/Tesla-Model-3-Long-Range-Dual-Motor.

Vidal, C. et al. Robust Xev battery state-of-charge estimator design using a feedforward deep neural network. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Practices Mobil. 2, 2872–2880. https://doi.org/10.4271/2020-01-1181 (2020).

Bramareswara Rao, S. N. V., Kumar, Y. P., Amir, M. & Muyeen, S. M. Fault detection and classification in hybrid energy-based multi-area grid-connected microgrid clusters using discrete wavelet transform with deep neural networks. Electr. Eng. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-024-02329-4 (2024).

Mhatre, M. S., Siddiqui, F., Dongre, M. & Thakur, P. M. A review paper on artificial neural network: a prediction technique. International J. Sci. Eng. Research 6. (2015). https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:212584638

Adedeji, B. P. & Kabir, G. A feedforward deep neural network for predicting the state-of-charge of lithium-ion battery in electric vehicles. Decis. Analytics J. 8, 100255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dajour.2023.100255 (2023).

El Fallah, S. et al. Advanced state of charge Estimation using deep neural network, gated recurrent unit, and long short-term memory models for lithium-Ion batteries under aging and temperature conditions. Appl. Sci. 14(15), 6648. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14156648 (2024).

Cervellieri, A. A. Feed-Forward Back-Propagation neural network approach for integration of electric vehicles into Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) to predict state of charge for Lithium-Ion batteries. Energies 17(23), 6107. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17236107 (2024).

Chandran, V. et al. State of charge Estimation of lithium-ion battery for electric vehicles using machine learning algorithms. World Electr. Veh. J. 12(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj12010038 (2021).

Shahriar, S., Al-Ali, A. R., Osman, A. H., Dhou, S. & Nijim, M. Prediction of EV charging behavior using machine learning. IEEE Access. 9, 11576–111586. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3103119 (2021).

Frendo, O., Gaertner, N. & Stuckenschmidt, H. Improving smart charging prioritization by predicting electric vehicle departure time. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 22(10), 6646–6653. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2020.2988648 (2021).

Almaghrebi, A., Aljuheshi, F., Rafaie, M., James, K. & Alahmad, M. Data-driven charging demand prediction at public charging stations using supervised machine learning regression methods. Energies 13(16), 4231. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13164231 (2020).

Chung, Y. W., Khaki, B., Li, T., Chu, C. & Gadh, R. Ensemble machine learning-based algorithm for electric vehicle user behavior prediction. Appl. Energy. 254 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.113732 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the department of Electrical Power & Machines Engineering, The Higher Institute of Engineering at El-Shorouk City, El-Shorouk Academy, Cairo, Egypt, for providing the necessary facilities to carry out the work.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.A., B.A.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation. A.Y.A.: Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. R.A.: Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelaziz, M.M., Abdelaziz, A.Y., El-Sehiemy, R.A. et al. Multistage prediction approach of EVs charging performance in smart transportation systems by deep learning technique. Sci Rep 15, 37669 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21625-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21625-y