Abstract

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices allow real-time glucose readings leading to improved glycemic control. However, glucose predictions in the lower (hypoglycemia) and higher (hyperglycemia) extremes, referred as glycemic excursions, remain challenging due to their rarity. Moreover, limited access to sensitive patient data hampers the development of robust machine learning models even with advanced deep learning algorithms available. We propose to simultaneously provide accurate glucose predictions in the excursion regions while addressing data privacy concerns. To tackle excursion prediction, we propose a novel Hypo-Hyper (HH) loss function that penalizes errors based on the underlying glycemic range with a higher penalty at the extremes over the normal glucose range. On the other hand, to address privacy concerns, we propose FedGlu, a machine learning model trained in a federated learning (FL) framework. FL allows collaborative learning without sharing sensitive data by training models locally and sharing only model parameters across other patients. The HH loss combined within FedGlu addresses both the challenges at the same time. The HH loss function demonstrates a 46% improvement over mean-squared error (MSE) loss across 125 patients. Compared to local models, FedGlu improved glycemic excursion detection by 35% compared to local models. This improvement translates to enhanced performance in predicting both, hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, for 105 out of 125 patients. These results underscore the effectiveness of the proposed HH loss function in augmenting the predictive capabilities of glucose predictions. Moreover, implementing models within a federated learning framework not only ensures better predictive capabilities but also safeguards sensitive data concurrently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A peptide hormone known as insulin is produced by the beta cells in the pancreases. Insulin plays a crucial role in regulating the transport of glucose and facilitating its absorption by cells from the bloodstream for energy production. Any disruption in this process leads to a medical condition called Diabetes mellitus (DM), more commonly referred as diabetes. Globally, this chronic disease affects nearly 537 million lives with an additional 374 million classified as prediabetic, putting them at similar risks of developing complications1. Diabetes can lead to both, immediate and long-term health issues, including blindness, kidney failures, amputations, heart-related diseases, seizures and in severe cases, even death2,3,4. Diabetes is broadly categorized into type 1 and type 2. In type 2 diabetes, cells become resistant to insulin, hindering their ability to absorb glucose. Type 2 diabetes constitutes 95% of the diabetes population and is typically prevalent in older age-groups. On the other hand, Type 1 diabetes arises when the pancreas fails to produce sufficient insulin. Type 1 diabetes accounts for about 5% of the diabetes population and is mainly found in age groups 0–20 years of age. However, it requires a much more rigorous diabetes management to avoid the imminent consequences. The overarching goal of diabetes management is to maintain euglycemia (normal glucose levels) or increase time spent within the optimal range (time-in-range, TIR)2. Insulin therapy is the mainstay of diabetes management, requiring a delicate balance between short-term and long-term objectives5,6. While diabetes cannot be cured, proper insulin management allows patients with diabetes to keep optimal blood glucose levels and minimize the risk of further complications7.

The most widely used method for glucose monitoring involves the use of fingerstick technique, where a small blood sample is drawn by pricking the finger and analyzed using the glucometer8,9. This was revolutionized by Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) devices, that offer real-time glucose monitoring with automated readings. This has evidently led to increasing time spent by patients in TIR, a crucial metric in diabetes care10,11. CGM devices have proven to enhance glycemic control by reducing both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia excursions through real-time predictions12,13. While previous research for type 1 diabetes has primarily focused on predicting hypoglycemia events10,14,15,16,17,18,19, achieving glycemic goals requires maximizing glucose readings in TIR by avoiding both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia.

Efforts to develop machine learning (ML) models for glucose predicting using historical CGM readings have shown reasonable efficacy. These models typically rely on extensive training data, often gathered through large-scale clinical research studies or healthcare providers. The data is often stored in cloud-based servers and poses significant privacy risks, with concerns about data theft and user privacy20. Given the escalating concerns of data theft, user security and privacy, recently many countries have enforced regulations aiming to address these concerns and protection regulations to protect the interests of the people21,22,23. An alternative strategy is to develop individual models with personal data to enhance privacy, but this comes with the drawback of reduced prediction performance due to limited data. ML and deep learning models require substantial data for optimal performance.

Thus, to overcome the challenges in glycemic excursion prediction and privacy concerns, we propose a collaborative learning framework that addresses these concerns simultaneously. The major contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

A novel, HH loss function, for improved prediction performance in the glycemic excursion regions.

-

FedGlu, a personalized machine learning model trained in a federated learning framework for improving model performance and data privacy preservation simultaneously.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section II reviews the current literature and points out relevant papers. Section III describes the dataset in detail. It also explains the methods like HH loss function, and the federated learning used as part of the paper, different metrics used for evaluation and the different setup of experiments in the paper. Section IV compares the results derived for the different experiments with the HH loss function, comparison between central, local, and personalized federated models. Section V provides discussion and insights on the results, limitations, and future work for the paper. Lastly, Section VI concludes the paper.

State of the Art

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the existing literature on glucose prediction. While a comprehensive review may be out of the scope of this paper, we emphasize works that have focused on predicting glucose values with deep learning approaches, use of federated learning for healthcare applications and extending the global federated model through fine tuning for personalization.

CGM-based glucose prediction

The first attempt to predict future glucose levels using past values dates back to 1999 by Bremer and Gough24. Since then, researchers have continually advanced the literature to develop powerful and highly accurate models. Machine learning models for glucose prediction fall into two categories: (a) Classification tasks, (b) Regression task. Consistent with the theme of our paper, we focus on the regression tasks. Earlier approaches utilized conventional machine learning methods such as linear regression (LR), support vector regression (SVR), random forests (RF), boosting algorithms25,26,27,28 and time-series forecasting methods like autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA)29,30 for predicting glucose levels. In recent years, there has been a shift towards employing deep learning (DL) models, leveraging automated feature learning, robust pattern recognition, and abstraction through multiple layers.

Various DL architectures, including multi-layer perceptron (MLP)31,32, convolutional neural networks (CNN) and convolutional recurrent neural networks (CRNN)33,34, recurrent neural networks (RNN)35,36, short long-term memory networks (LSTM)37,38,39, dilated RNNs40,41 and bi-directional LSTMs42,43,44, have been proposed for glucose prediction.

Shuvo et al.45 introduced a deep multi-task learning approach using stacked LSTMs to predict personalized glucose concentration. The proposed approach includes a combination of stacked LSTMs to learn generalized features across patients, clustered hidden layers for phenotypical variability in the data and subject-specific hidden layers for optimally fine-tuning models for individual patient improvement. The authors demonstrate superior results compared to state-of-the-art ML and DL approaches on the OhioT1DM dataset.

A transformer based on an attention mechanism was recently proposed to forecast glucose levels and hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia events46. The proposed transformer network includes an encoder network to perform the regression and classification tasks under a unified framework, and a data augmentation step using a generative adversarial network (GAN) to compensate for the rare events of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. Results were demonstrated on two datasets, one including type 1 diabetes patients and the other on type 2 diabetes patients.

In pursuit of enhanced prediction performance, researchers have often grappled with the constraint of limited data for individual subjects or patients. A recently proposed approach addresses this challenge through multitask learning for advancing personalized glucose prediction47. This approach was evaluated against sequential transfer learning, revealing two key findings: (a) individual patient data alone may not suffice for training DL models and (b) a thoughtful strategy is crucial to leverage population data for improved individual models. The dataset that was used in this study was the OhioT1DM dataset.

While the literature commonly employs standard regression metrics like root-mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and Clark’s Error Grid Analysis (EGA) for clinical context, an often-overlooked aspect in the analysis of these metrics in glycemic excursion regions. For instance, RMSE in hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia ranges can be evaluated, Clark’s EGA can be applied to glucose readings falling in Zones C, D, and E. Mu et al.48 introduced a normalized mean-squared error (NMSE) loss function, demonstrating a substantial reduction in RMSE for the hypoglycemia range. However, comprehensive details regarding its superiority over MSE in detecting hypoglycemia are lacking, and its performance in hyperglycemia ranges is not addressed.

Data imbalance

There is a significant imbalance in glucose data distribution across the hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and normal ranges. Typically, only 2–10% of glucose readings fall into the hypoglycemia range, while about 30–40% fall in the hyperglycemia range. From a statistical perspective, this presents a classic case of an imbalanced regression problem. While numerous approaches have been developed to tackle the imbalanced data in the classification setting, very few works have been proposed to address the imbalance regression problem, like ours, in the literature49. Existing approaches for imbalanced regression can be broadly categorized into two types:

Sampling-based approaches

These methods attempt to either under sample the high-frequency values or oversample the low frequency (rare) values. However, determining the ‘notion or rarity’ in a regression problem is challenging compared to a classification task. Oversampling may lead to overfitting, whereas under sampling may result in sub-optimal performance because of loss of key information. Chawla et al.50 proposed an approach that generates synthetic samples by combining oversampling and under sampling of the training data for classification task.

Cost-sensitive approaches

Cost-sensitive approaches: These approaches introduce a penalizing scheme during training to enable the model to handle outlier values (low-frequency or rare values) enhancing its effectiveness in predicting within those ranges. The recent success of this approach51,52,53 motivates us to explore this approach further through our customized loss function.

Federated learning for healthcare

Federated learning (FL) has substantial disruptive potential in healthcare, a domain constrained by sensitive data and strict regulations such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the US. The reluctance of healthcare entities to share sensitive data has fueled the adoption of FL in various healthcare applications, like medical image processing54,55,56, IoT-based smart healthcare applications57, managing electronic health records (EHR)58, disease prediction59,60,61, predict hospitalizations and mortality62,63,64, natural language processing from clinical notes65,66,67, etc. A few researchers comprehensively reviewed federated learning in healthcare68,69,70,71.

In the diabetes literature, FL has recently gained traction. A recent study proposed a deep learning approach in the Diabetes Management Control System (DMCS)72, using 30 virtual subjects from the FDA approved UVA/Padova Type 1 diabetes simulator. Features such as past glucose values, carbohydrate intake, and insulin-on-board were used as input for the model for the diagnosis of diabetes. The findings clearly demonstrate the superior performance of the federated model over the local models.

Another study employed an FL-inspired Evolutionary Algorithm (EA) for classifying glucose values into different risk categories73 using data from 12 patients in the OhioT1DM dataset. The input features include previous CGM readings, carbohydrates, and insulin data. The results indicate improved performance over local models using an FL-based EA. However, the study’s limitation lies in its small sample size of only 12-patients and the absence of addressing real-time glucose-related risk-prediction and its clinical significance.

A decentralized privacy-protected federated learning approach was applied to predict diabetes-related complications using patient-related comorbid features extracted from International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes in real-world clinical datasets74. For this, a logistic regression model, 2-layer multi-perceptron model and 3-layer multi-perceptron models were proposed and compared against a centralized (population-level) model. The study addressed class imbalance using techniques like under-sampling, oversampling, and balancing. The results indicate that models developed through the federated learning framework can achieve promising performance that is comparable to the centralized models.

Personalized federated learning

Federated learning has its many unique challenges75,76,77, with one prominent issue being the variation in data distribution across clients in the network. This is characteristic of non-i.i.d. and imbalanced data78. This is particularly significant in healthcare applications where individual patients possess diverse demographics and health histories, necessitating adaptive solutions tailored to each participant79.

One of the pioneering works in federated learning with wearable healthcare data is FedHealth80, which introduces personalization through transfer learning. This is achieved by first training a conventional global model in a federated learning framework and later fine-tuning two fully connected layers (through transfer learning) to learn activities and tasks for specific users. The study utilizes publicly available human activity recognition data from accelerometry and gyroscope data across 30 users for multiple activity class prediction. The authors employ a CNN based deep learning model, comparing its performance against traditional machine learning methods like RF, SVM, and KNN. The results demonstrate a 4% average improvement in performance for personalized models compared to the global model.

Another noteworthy application of personalized federated learning was used for in-home health monitoring81. The authors introduce FedHome, a cloud-edge based federated learning framework, where a shared global model is initially learned from multiple network participants. Individual personalization is achieved using a generative convolutional autoencoder (GCAE), aiming to generate a class-balanced dataset tailored to individual client’s data. FedHome exhibits a notable improvement of over 10% in accuracy compared to a conventional global federated learning model.

A recent study on remote patient monitoring (RPM) introduced FedStack architecture, a personalized federated learning approach79. The study was based on the MHEALTH dataset with 10 patients82,83. A total of 21 features are extracted from three sensor data types (accelerometry, gyroscope and magnetometer) to classify 12 different natural activities. Three different model architectures (ANN, CNN, Bi-LSTM) are used in the study. FedStack architecture achieves personalization by aggregating heterogenous architectural models at the client level and demonstrates that the FedStack approach consistently outperforms both local and global models.

A recent work in personalized federated learning focused on in-hospital mortality prediction62. The study utilized a publicly available electronic health records (HER) database, comprising over 200,000 patients across 208 hospitals in the US. Features were extracted from patients’ HER and employed for a binary classification problem, with a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) adopted for modeling. The proposed POLA method involves the initial training of a global federated learning model, referred to as the teacher model. In the subsequent step, local adaptation is accomplished through a Genetic Algorithm (GA) approach. Comparative results highlight the superior performance of the POLA approach against the traditional FedAvg84 and two other state-of-the-art personalized federated learning architectures85,86.

For CGM based glucose prediction in T1D populations, a recent paper proposes an asynchronous and decentralized federated learning approach where future glucose trajectories are predicted from historical CGM values87. The proposed work also signifies a personalized model where individual patients can benefit and is tested with multiple publicly available datasets for adult T1D patients. Another recent approach focused on a privacy-preserving glycemic management for T1D use a federated reinforcement learning framework where the goal was to maximize the time-in-range (TIR) and reduce glycemic risk scores88. The study was conducted on data generated from 30 individuals using a UVA-Padova T1D simulator. Federated learning holds great potential in overcoming the challenges of privacy and delivering personalized predictions that can benefit individuals with T1D.

Methods and materials

This section describes the datasets used in this study, data processing steps and the experimental setup. Further, we describe the prediction model, and the different frameworks used in this study.

Clinical datasets and preprocessing

Ohio T1DM

The Ohio T1DM89 dataset was publicly released in two batches (2016 and 2018) with a total of 12 participants. During the 8-week study period, all 12 participants wore a Medtronic Enlite CGM for collecting glucose readings, a Medtronic 530G/630G insulin pump and an Empatica/Basis sensor for collecting physiological data collection. For our analysis, we only focus on the CGM data. The patient data was collected in free-living conditions.

TCH study

This is a proprietary data collected at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX. from a total of 113 T1D patients using Dexcom CGM devices. The data for each patient spans a period of 30–90 days. Additional information about this dataset is available in our previous publications25. Similar to the OhioT1DM dataset, the data for all patients was collected under free-living conditions.

Comprehensive details about these two datasets are provided in Table 1. Figure. 1 illustrates glycemic excursions across all patients, specifically hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia profiles. The dotted grey lines on the x-axis and y-axis represent the median hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia percentages respectively. It is evident that the prevalence of hyperglycemia (\(\:\stackrel{-}{x}=41.7\%and\:x\cong\:22.7\%\)) is considerably higher compared to hypoglycemia (\(\:\stackrel{-}{x}=2.3\%and\:x\cong\:1.7\%\)).

Data preprocessing

Based on the available literature90, data preprocessing involves two main steps: first, replacing ‘Low’ and ‘High’ glucose readings with 40 mg/dL and 400 mg/dL, respectively. Second, imputing missing glucose readings through linear interpolation when less than six consecutive readings are missing. This threshold is chosen based on the literature available on autocorrelation between glucose readings27,91. After interpolating missing values, consecutive sequences of glucose readings in the last two hours (24 readings) are taken as individual samples. This time-window is selected based on our previous works for glucose prediction12. Any samples with missing values at this stage are excluded from our analysis. All preprocessing steps have been taken following standard practices in the literature for analyzing CGM data92. For our analysis, we compare three different model types (Figure. 3), frameworks based on the data used for training and the training process:

HH loss

Our custom loss function is derived on the principle of Taguchi loss function93,94 and is based out of two primary needs: (a) enhancing penalties for errors in glycemic excursion regions, and (b) simultaneously balancing these penalties considering the uneven distribution of samples in the hypoglycemia, normal and hyperglycemia glucose ranges. For the first goal, we add a polynomial increasing penalty for glucose readings further they deviate from the normal range. To achieve the second objective i.e., to account for the disproportionate sample distribution in the hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and normal glucose ranges, we introduce a tuning parameter \(\:\alpha\:\). This parameter ensures that while reducing the errors in the glycemic excursion regions, the predictive performance for overall glucose readings is not compromised.

.

As outlined in Eq. (1), a penalty is applied, equivalent to the square of the distance of the glucose value and the mid-point of the glycemic excursion boundary, for values falling within the hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia ranges. We also provide a visual institution behind the HH loss function in Figure. 2. There is no additional penalty for errors in the normoglycemia but for different values of \(\:\alpha\:\) there is a significant additional penalty in the hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia regions forcing the model to perform better in these critical excursion regions. The value of \(\:\alpha\:\) is tunable to adjust for varying data distributions. For a more detailed derivation, please refer Appendix.

Federated learning

Federated Learning is a distributed learning framework that enables the training of machine learning models without transmitting sensitive user data to a central server. It relies on collaborative learning between participating users, where each user trains a shared model locally on its own training data through multiple rounds of optimization. Only the model characteristics such as model parameters, weights, gradients etc. are shared among users in the network. The sharing process can occur directly among the participating users or through a central server depending on the FL network topology. After receiving and aggregating the shared model characteristics from all users (e.g.: simple average, weighted averaging), the aggregated information is relayed back to users for further optimization by participants on their individual local data. This iterative communication process continues through multiple rounds until a stopping criterion (e.g.: convergence) is met. All user data remains stored locally, and only specific model characteristics are shared during this collaborative learning process. This approach reduces network and communication costs as model parameters are much smaller in size than actual training data. Additionally, it provides increased accessibility and comparable accuracy to conventional machine learning models. In addition to this, some level of privacy guarantees is ensured. The decentralized nature of federated learning allows patients and clinicians to benefit from more accurate and reliable models trained across a more extensive and diverse data pool.

A general formulation of the federated learning can be expressed as follows:

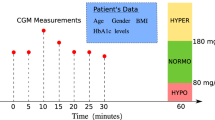

Glucose prediction specific problem formulation

In general, input for a data-driven algorithm for predicting future glucose levels primarily consists of historical glucose readings (\(\:g\)) and other features (physiological data, insulin, and carbohydrates intake etc.) if available. In our case where, we predict future glucose readings based on historical glucose readings observed. More specifically, we will learn patterns based on glucose readings observed in the past two hours to predict glucose readings 30 minutes in the future. This is so that individuals can take interventions to prevent glycemic excursions. Figure. 3 provides a graphical representation of the different learning paradigms that we use in our analysis.

Local model

Data is stored locally with the patient and not shared across other entities, such as a central server or other patients in the network. While this approach ensures full data privacy, the training data for training the model is limited to the individual patient and risks suboptimal performance. As shown in figure. 3, for local models, all the data storage and model training occurs locally and a central server has no role to play.

Central model

Unlike with the local model, in this setting, patient data from all individuals are shared at a central server, where a single joint model is trained on data from all individuals in the network. While the central model benefits from a large data pool of data for training, it has minimal privacy for individual patients, as their entire patient data corpus is shared with a central server. As shown (Figure. 3), all data and model training occur at the central server where individual patient data has been stored.

Federated (global) model

Federated model (or sometimes also called global model) combines advantages of both the local and central models by bringing together robust prediction capabilities of the central model along with the data privacy aspects of the local models. In this approach, data storage and model training occur locally on the patient’s device. During the training process, optimization of parameters locally for each individual patient over their own data and model weights/parameters are shared frequently with a central server for aggregation. These aggregated weights are then returned to individual patients and serve as initializers for further training. Actual data is never shared with other patients in the network or with a global server, maintaining privacy. This is known as model development in a federated-learning framework84. Models in this framework achieve better prediction performance through shared learning with other patients while preserving privacy. However, global models may not always be the most suitable for every entity (here, patient) in the network. To address this, we extend the global model via a fine-tuning step, by personalizing the global model for each individual patient with the custom HH loss function to achieve personalization for individual patients in the network.

FedGlu model

FedGlu is an extension of the federated model that personalizes model for individual patients. A simple workflow is presented in Figure. 4. The holistic mechanism of the FedGlu algorithm is presented in Figure. 3 where the central server initializes the global model with random weights and broadcasts it to each participating patient in the network. Each patient trains this globally shared model on its own data using the MSE loss function and once trained for a fixed number of epochs, send the trained weights to the central server for aggregation. The central server will receive updated model weights from each of the patients where the global model was trained using a patient’s own individual local data. This is one communication round within the federated learning step. The server aggregates model weights received from all patients, checks if convergence is reached and broadcasts the updated global model back to the patients for further training. This process continues until global model achieves convergence after which the central server sends the final global model to all the participating patients in the network. Once the patient has received the final global model, patients will fine-tune this global model one more time but this time using the HH loss function. This fine-tuning step is asynchronous and helps achieve the desired personalization leveraging data for training robust models across all patients as well as adjusting for unique local data distributions.

Model architecture

A multilayer perceptron model is used for analysis in this study. The input layer consists of glucose readings observed in the last 2 h. This input with dimensions \(\:24\:x\:1\) is fed into a dense layer of 512 neurons with a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function. The output feature map is passed through two hidden layers with 256 neurons and outputs a 64-neuron layer which, both activated with a ReLU activation. The final output layers get their input from the 3rd dense layer in the network and provide a single number prediction of the future glucose reading.

Validation approach

In line with our prior research12,14, we implement a 5-fold validation strategy with temporally partitioned splits. This strategy guarantees that training and testing splits are derived from non-overlapping time-windows, mitigating potential biases from temporal correlations that could lead to overly optimistic results. This methodology aligns with the BGLP Challenge, where the initial few days of data are utilized for training and the subsequent days constitute the hold-out test set. In our work, we extend the same across multiple splits to make it more robust.

Evaluation metrics

We illustrate the efficiency of our approach using standard metrics in glucose prediction: root mean squared error (RMSE) along with Clark’s Error Grid (Figure. 5)95 to evaluate clinical significance of the predictions. RMSE is defined as:

Clarke’s Error Grid Analysis (CEGA) is described in Figure. 5 and the definitions of each zone are provided in Table 2.

Model training/hyperparameter tuning

To provide robust estimates of our methodology and support the enlisted contributions with results, we consider the following experiments:

-

1.

Setup 1 – Advantage of HH loss function: The performance with the HH loss function is compared against the standard mean squared error (MSE) loss. We demonstrate the advantage in terms of standard regression metrics and the clinical significance for glucose predictions. We compare the HH loss function results across two separate datasets namely TCH study data and the OhioT1DM dataset. We use a central (population-level) model to obtain the results.

-

2.

Setup 2 – Usefulness of Personalized Federated Models: We compare the performance across the different model types: central model, local model, global federated model, and the personalized federated model. The comparison is made independently across both datasets. This setup will prove the robustness of ML models trained in a federated learning work against the central and local models.

Evaluation metrics

All models at central, local, and federated (global and personal) levels shared identical architecture and parameters. The learning rate was fixed at 0.001 with a constant batch-size of 500. The training was set to a maximum of 50 epochs, with early stopping for a patience of 10 epochs to avoid prevent redundant training and thereby reduce computational time. The global federated model is trained with TensorFlow-federated. The client-optimizer was set to ‘Adam’ with a learning rate of 0.001 and the serve-optimizer to ‘SGD’ with a learning rate of 1 to mimic the baseline federated model84. The number of communication rounds was set to 50, and a simple weighted-average proportional to the number of samples with each patient (node) in the network was used as the aggregating function. The global federated model is saved after observing the train loss (MSE) convergence. Individual patients (nodes) then fine-tune this saved global federated model on their individual local data with an ‘Adam’ optimizer and a learning rate of 0.001. This fine-tuning step is however done the custom HH loss function. For comparing results, the local-level and (personalized) federated-level models, with a specific \(\:\alpha\:\), is selected based on the training data where the combined RMSE (across hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia) is minimum. At the central level, a single \(\:\alpha\:\) which showed the maximum combined reduction across all patients, was considered.

Results

This section describes the datasets used in this study, data processing steps and the experimental setup. Further, we describe the prediction model and the different frameworks used in this study.

Advantage of HH loss function

In the first analysis, we assess how the HH loss function enhances prediction performance in the glycemic excursion regions while maintaining clinical significance for overall predictions based on two independent datasets. For this we consider a centralized (population-level) model development setting. Since a common model is trained across all the patients for the dataset, we choose a single\(\:{\prime\:}\alpha\:{\prime\:}\) value (\(\:\alpha\:=1\)) which showed the combined maximum improvement (reduction in RMSE) across hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia ranges on the training dataset.

TCH study dataset

Figure. 6 (left), gives a performance comparison between the HH loss and the baseline mean squared error (MSE) loss. The HH loss function exhibits a 52% reduction in root-mean-squared error (RMSE) for the hypoglycemia region compared to MSE, while showing similar performance in the hyperglycemia region. Although there is a slight dip in overall prediction performance (regarding RMSE values), the clinical impact evaluated through Clark’s EGA is negligible and on the contrary better with HH loss than MSE.

In our evaluation using Clark’s Error Grid (Table 3) to gauge the clinical relevance of the predictions, the HH loss exhibited superior performance, missing to detect an average of only 0.51% of excursions, compared to 2.07% with MSE - representing a substantial 75% reduction. This refers to Zone: D + E from CEGA, and predictions falling in this region are analogous to false negatives from the confusion matrix used to detect hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. Excursion detection is critically important as it allows patients to take intervention measures based on the prediction. Additionally, overall glucose predictions within the combined Region A + B improved from 97.94% to 99.39%. These findings underscore that, while the HH loss introduces a bias (increasing predictions in Zone: C) towards enhancing accuracy in excursion regions (hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia), it does not detrimentally affect the clinical accuracy of overall glucose predictions.

Ohio T1DM dataset

For the OhioT1DM dataset, Figure. 6 (right) a similar performance comparison, the HH loss exhibits an RMSE of 15.12 for the hypoglycemia region, which is 41% less than the MSE, whereas in the hyperglycemia region the RMSE remains relatively consistent. Similar to the performance observed with the TCH study data, there is a decline in overall prediction performance in terms of RMSE values. However, this performance drop is trivial when assessed for the clinical significance with CEGA. The CEGA provides evidence for this claim. The number of data points in the regions: D + E from reduces from 2.05% with MSE to 0.32% (84% reduction) with the HH loss – indicating an increase in the model’s ability to predict excursions. Concurrently, the percentage of data points in the regions: A + B increases from 97.89% to 99.59%, suggesting an improvement in overall predictions without compromise.

Model training in a federated learning framework

The predictive capabilities of models incorporating the HH loss function were extensively evaluated at the local, central, and federated levels. In Figure. 7, the magnitude of difference (measured in RMSE) in various glycemic excursion regions is presented. Table 4 compares different model types through Clarke’s Error grid analysis, while Table 5 outlines improvements in terms of the number of patients for RMSE and CEGA. Compared to local models, federated models exhibit an improvement of 16.67% (in RMSE) for predicting hypoglycemia and 18.91% (in RMSE) for predicting hyperglycemia simultaneous – both statistically significant using the paired t-test (\(\:p\ll\:0.01\)). For the TCH study data, federated models demonstrated improvements for 96 (out of 113) patients in hypoglycemia region and 110 (out of 111) patients in hyperglycemia regions over local models simultaneously. Regarding the OhioT1DM dataset, federated models improved by 9% (in RMSE) for predicting hypoglycemia and 33.29% (in RMSE) for predicting hyperglycemia. Although the improvement in hyperglycemia is statistically significant (\(\:p\ll\:0.01\)) but hypoglycemia (\(\:p=0.18\)) is not. For the OhioT1DM dataset, federated models improve for 9 (out of 12) patients in hypoglycemia region and 12/12 patients in hyperglycemia region, over the local models. Across the two datasets, there is an improvement of 12.37% (in RMSE) for predicting hypoglycemia and 29.05% (in RMSE) for prediction hyperglycemia – which are both statistically significant with (\(\:p\ll\:0.01\)).

When evaluated for clinical significance through Clark’s Error Grid, it is evident that HH loss function improves glycemic excursions (Region: D + E) prediction at all levels without compromising the clinical significance of overall predictions (Region: A + B) across both datasets. Comparing local and federated models, for the TCH study data, we see a 37% reduction (\(\:p\ll\:0.01\)) and for the OhioT1DM dataset, 31% reduction (\(\:p\ll\:0.01\)) in points falling in the Region: D + E (compared to MSE) which signifies an increase in the detection capability of glycemic excursions. When comparing local and federated models for predictions falling in the Region: C of CEGA, for the TCH study data, there is a 50% reduction whereas for the OhioT1DM dataset, there is a 20% reduction in which signifies fewer false predictions with the federated models. Table 4 also provides evidence that federated models when compared to local models through CEGA, are able to improve over local models for all regions of CEGA for almost all patients across the two datasets.

On the other hand, central models distinctly outperform federated models for both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia due to their advantage of a significantly larger training pool. This is evident in the evaluation with RMSE and CEGA. However, compared to the local models, federated models achieve a much closer performance to central models. Table 5 outlines the improvement with federated models against central and local models for each of TCH and OhioT1DM datasets.

Discussion

Based on the results, the main contributions of our work can be summarized as:

-

1.

Introduction of a novel HH loss function aimed at improving glucose predictions in the excursion regions while ensuring clinically significance.

-

2.

Model implementation with the HH loss function within a federated learning framework, balancing performance in the excursion region and privacy.

Insights and observations

Models with HH loss function can predict more accurately and clinically significantly in glycemic excursion regions at local, central, and federated levels. This performance may result in sub-optimal RMSE values in the overall glucose ranges. However, when compared for clinical significance, there is no reduction and on the contrary, it improves overall predictions in regions: A + B. A detailed evaluation with CEGA with different model types, including local, central, and federated models is presented in Table 6. A further expansion of CEGA zones for Table 6 is provided in Appendix 1.

In the proposed HH loss function, the parameter ‘\(\:{\alpha\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) plays a vital role in penalizing the errors and achieving balance across the three different glucose regions. This can be optimally chosen for the local and federated models as model training is done locally. However, in the case of the central model, we can choose a single value for the entire cohort of patients. This may be beneficial to the majority of patients but not all the patients. We further explore the impact of choosing different ‘\(\:{\alpha\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) values for the central model.

Also, when we compare model performance across the different model types, we see that federated model has varying level of differences compared to local and central models. We try to investigate further these improvements concerning the glycemic profiles of patients and who is likely to benefit the most.

Impact of ‘\(\:\varvec{\alpha\:}\)’ parameter

The parameter ‘\(\:{\alpha\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) can be tuned to achieve a well-balanced optimal prediction performance for hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia excursions regions simultaneously. A higher \(\:{{\prime\:}\alpha\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) value prioritizes performance in the hypoglycemia regions whereas a lower \(\:{\prime\:}{\alpha\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) emphasizes performance in the hyperglycemia region. Figure. 8 illustrates the average improvement (in RMSE) across patients in both glycemic excursion regions occurring co-occurring for various \(\:{\prime\:}{\alpha\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) values. The red curve, representing improvement in hypoglycemia values, shows an exponential increase compared to MSE as \(\:{\prime\:}\alpha\:{\prime\:}\) increases. In contrast, the blue curve indicating improvement in hyperglycemia values, exhibits a downward trend with increasing \(\:{{\prime\:}\alpha\:}^{{\prime\:}}\). However, the slope for hypoglycemia values is significantly steeper than hyperglycemia values. This is because of the high data imbalance that exists, especially for hypoglycemia values (median: 1.64%) as compared to hyperglycemia values (median: 43%). This also highlights the greater of accurately predicting hypoglycemia values compared to hyperglycemia values. The parameter \(\:{{\prime\:}\alpha\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) can be customized for local and federated models based on individual preferences and glycemic profiles to yield optimal results. Table 7 provides performance metrics (for central models) in terms of Clark’s EGA for different ‘\(\:{\alpha\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) values.

Federated models: who benefits the most?

We compare the performance improvements achieved with federated models against central and local models (with HH loss) across varying glycemic profiles of both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia regions. To categorize patients effectively, they are initially binned into groups of ten based on the percentage of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia values in their profile. For hypoglycemia, these intervals include (0, 0.22]%, (0.22, 0.5]%, and so forth, while for hyperglycemia, intervals are defined as (0, 7.81]%, (7.81, 19.31]%, and so on.

In the context of hypoglycemia prediction (Figure. 9), a notable trend emerges as the percentage of hypoglycemia values increases, the prediction performance of federated models, global models and local models converges. Patients with higher hypoglycemia values exhibit similar prediction performance across local, central, and federated models. However, for patients with extremely low instances of hypoglycemia, central models far outperform local and federated models. This is because training data for central models has multiple instances of hypoglycemia for the model to train whereas local and federated models do not have that advantage. The Spearman correlation coefficient (\(\:\rho\:\)) between mean improvement (in RMSE) with federated models and increasing hypoglycemia (interval) values, is statistically significant against both local (\(\:\rho\:=0.01\)) and central models (\(\:\rho\:=0.02\)). When compared for variance, it shows similar trend and is statistically significant across local (\(\:\rho\:=0.01\)) and central (\(\:\rho\:=0.01\)) models. It is also observed that, predictions performance with federated models is closer to the central models and also maintain a clear advantage over the local models for close to 50% of the patients.

In contrast, for hyperglycemia prediction (Figure. 9), no discernible patterns emerge across the different model types (federated model, global model, and local model) when compared to the hyperglycemia profile of patients. The Spearman correlation coefficient (\(\:\rho\:\)) for improvements with federated models over local (\(\:\rho\:=0.7\)) and central models (\(\:\rho\:=0.1\)) is not statistically significant. Furthermore, the performance disparity across these three model types (relative to hypoglycemia) is minimal for hyperglycemia prediction. A major contributing factor is a substantial difference in the number of hypoglycemia glucose values compared to hyperglycemia glucose values (the lowest bin for hyperglycemia is (0, 7.81]% and a median of 1.64%. In contrast, the highest bin for hypoglycemia is (4,63, 12.13]% and a median of 43%).

Beyond the presence of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia samples in the data, we evaluated the impact of different individual profile factors including gender, duration of diabetes and HbA1c values on the model performance. However, none of these factors showed any visual or statistical difference in performance between the central and federated models. This further corroborates the glycemic profiles of individuals representing the distribution of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia samples within a patient has the biggest impact on the performance of different model types.

Comparison with literature

We comprehensively compared between the HH loss function and a recent state-of-the-art NMSE (normalized mean squared error) that showed significant performance improvement in the hypoglycemia range. The comparison is made on standard evaluation metrics of RMSE and Clark’s EGA. Analyzing the TCH study data, HH loss improves performance against NMSE (Figure. 10 - left) by 29%. (\(\:p\ll\:0.01\)) in the hypoglycemia region and by 5% (\(\:p\ll\:0.01\)) in the hyperglycemia region. Similarly, for the OhioT1DM dataset (Figure. 10 - right), HH loss improves performance (in RMSE) in the hypoglycemia region by 21%. (\(\:p\ll\:0.01\)) and hyperglycemia region by 6% (\(\:p\ll\:0.01\)). Moreover, when compared using Clark’s EGA, models with the HH loss function fails to detect only 0.51% of glycemic excursions compared to 1.47% with NMSE (a 65% reduction). We also see an increase in points falling in Regions: A + B with the HH loss function compared to using either of MSE or NMSE (Table 8).

The OhioT1DM dataset, used in the BGLP challenge, is a standard dataset for comparing glucose prediction performance. While the BGLP challenge and other literature aim to show accurate predictions of overall glucose values, our work focuses explicitly on improved performance in the glycemic excursion regions (hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia), making comparisons challenging. Nevertheless, we attempt to show our work in the light of other notable studies based on CEGA, providing a standard and fair way to assess clinical significance.

Table 9 compares research achieving state-of-the-art performances using the OhioT1DM dataset. Remarkably, our simple MLP model, with several hundred times lower number of training parameters, outperforms or matches the top-performing models reported. Additionally, federated models, lacking access to the entire training data, show promising results compared to other state-of-the-art methods proposed in the literature.

Clinical applications

T1D requires rigorous management as hypoglycemia can lead to instantaneous life-threatening consequences while chronic hyperglycemia can result in a hybrid diabetes (both T1D and T2D), severely complicating diabetes management. Type 1 diabetes care prioritizes preventing impending hypoglycemia events while limiting chronic hyperglycemia. yet many individuals still miss > 70% time-in-range recommended targets. CGM provides short-horizon glucose predictions which are critical for diabetes care. Our framework is designed for future clinical integration in a way that preserves privacy and fits existing data flows. In a multi-site setting, FL models have demonstrated success at hospital scale in the EXAM study across 20 institutions, which improved external generalization without pooling protected data114. Multiple studies have suggested the utility of a federated learning framework by showing its technical compatibility with existing IT and clinical operations115. Specifically for diabetes workflows, CGM data are already integrated within EHRs where providers can access patient’s historical CGM trends116. In such settings, the use of model parameters over centralizing protected health information is of paramount importance. Individual patient participation in periodic federated rounds can be managed within current governance structures (model versioning, convergence checks), and outputs can be written to the EHR through standard interfaces. The tunable ‘\(\:\alpha\:\)’ parameter allows individual-level personalized priorities and glycemic targets to be achieved in practice. This positioning enables future integration without altering existing devices or centralizing patient data.

Limitations and future work

We introduce a bias towards glycemic excursion regions to enhance performance in the hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia regions. As a result, the prediction error for overall glucose does increase. However, we overcome this limitation by ensuring that clinical significance is not compromised. Additionally, when using HH loss, the federated models undergo a two-step construction process: (i) initial training with MSE loss function and (ii) subsequent fine-tuning with the HH loss at local levels. In future endeavors, we aim to implement a single step personalized federated model combining these two phases. This work uses the baseline federated learning framework to develop the proposed algorithm, FedGlu. There can be many challenges for its adoption in the real-world, like the unavailability of one or more entities in the network, a corrupt local entity or a corrupt central server which may compromise the privacy of the framework. However, this work aimed to lay the groundwork for using federated learning in glucose prediction algorithms that can benefit patients. The authors plan to improve the proposed FedGlu by adding privacy guarantees in subsequent works and also tackle the challenge of unavailability among participating entities for improved learning.

Conclusion

In this work, we proposed a novel HH loss function that simultaneously improves predictions in both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia regions without compromising overall predictions. This is critical as the HH loss function improves the glycemic excursion detection capabilities by an average of 78% across two datasets (a total of 125 patients) as compared to the standard MSE loss. The results were consistent with a proprietary dataset and publicly available OhioT1DM datasets. We also demonstrated the consistency of the HH loss function via FedGlu, a machine learning through a collaborative learning approach. FedGlu clearly outperforms the local models (35% improved glycemic excursion detection capabilities) while coming close to central model performances. These results prove the need to develop machine learnings models with strong predictive capabilities and ensure privacy for sensitive patient healthcare data.

Data availability

The TCH study data used and/or analyzed in the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sun, H. et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 183, 109119 (Jan 2022).

Battelino, T. et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care. 42, 8 (Aug 2019).

Beck, R. W. et al. Validation of time in range as an outcome measure for diabetes clinical trials. Diabetes Care. 42 (Mar), 3 (2019).

Group, D. R. Epidemiology of severe hypoglycemia in the diabetes control and complications trial. Am. J. Med. 90, 450–459 (1991).

Lund, S. S. et al. Effect of adjunct Metformin treatment in patients with type-1 diabetes and persistent inadequate glycaemic control. A randomized study. PLoS One, 3, e3363 (2008).

Moon, R. J., Bascombe, L. A. & Holt, R. I. The addition of Metformin in type 1 diabetes improves insulin sensitivity, diabetic control, body composition and patient well-being. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 9 (Jan), 1 (2007).

Larme, A. C. & Pugh, J. A. Attitudes of primary care providers toward diabetes: barriers to guideline implementation. Diabetes Care. 21 (Sep), 9 (1998).

Atkin, S. H., Dasmahapatra, A., Jaker, M. A., Chorost, M. I. & Reddy Fingerstick glucose determination in shock. Ann. Intern. Med. 114 (Jun 15), 12 (1991).

Pfützner, A. Advances in patient self-monitoring of blood glucose. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 10, 101–103 (2016).

Li, J. et al. Non-invasive monitoring of three glucose ranges based on ECG by using DBSCAN-CNN. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 25 (Sep), 9 (2021).

Mariani, H. S., Layden, B. T. & Aleppo, G. Continuous glucose monitoring: A perspective on its Past, Present, and future applications for diabetes management. Clin. Diabetes. 35 (Jan), 1 (2017).

Dave, D. et al. Improved Low-Glucose predictive alerts based on sustained hypoglycemia: model development and validation study. JMIR Diabet. 6, e26909 (Apr, 2021).

Rodbard, D. Continuous glucose monitoring: A review of recent studies demonstrating improved glycemic outcomes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 19, S25–S37 (Jun 2017).

Dave, D. et al. Detection of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia using noninvasive wearable sensors: ECG and accelerometry. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 18 (2), 351–362 (2024).

Gabbay, M. A. L. et al. P. C. Time in range: a new parameter to evaluate blood glucose control in patients with diabetes. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 12, 1 (2020).

Ling, S. H., San, P. P., Lam, H. K. & Nguyen, H. T. Hypoglycemia detection: multiple regression-based combinational neural logic approach. Soft. Comput. 21, 2 (Jan, 2017).

Ling, S. H., San, P. P. & Nguyen, H. T. Non-invasive hypoglycemia monitoring system using extreme learning machine for type 1 diabetes. ISA Trans. 64, 440–446 (Sep, 2016).

Ling, S. S. & Nguyen, H. T. Genetic-algorithm-based multiple regression with fuzzy inference system for detection of nocturnal hypoglycemic episodes. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 15 (2), 308–315 (Mar, 2011).

Lipponen, J. A. et al. Hypoglycemia Detection Based on Cardiac Repolarization Features (IEEE, 2011).

Cohen, I. G. & Mello, M. M. HIPAA and Protecting Health Information in the 21st Century. JAMA, 320, 3Jul 17 231–232. (2018).

McCall, B. What does the GDPR mean for the medical community? Lancet 391, 1249–1250 (2018).

Vayena, E., Blasimme, A. & Biomedical Big Data. New models of control over Access, use and governance. J. Bioeth. Inq. 14 (Dec), 4 (2017).

Vayena, E., Blasimme, A. & Cohen, I. G. Machine learning in medicine: addressing ethical challenges. PLoS Med., 15, (11), e1002689 (Nov, 2018).

Bremer, T. & Gough, D. A. Is blood glucose predictable from previous values? A solicitation for data. Diabetes 48 (3), 445–451 (1999).

Dave, D. et al. Feature-Based machine learning model for Real-Time hypoglycemia prediction. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 15 (Jul), 4 (2021).

Georga, E. I. et al. D. I. Multivariate prediction of subcutaneous glucose concentration in type 1 diabetes patients based on support vector regression. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 17 (Jan), 1 (2013).

Georga, E. I., Protopappas, V. C., Ardigo, D., Polyzos, D. & Fotiadis D. I. A glucose model based on support vector regression for the prediction of hypoglycemic events under free-living conditions. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 15 (Aug), 8 (2013).

Tabaei, B. P. & Herman, W. H. A multivariate logistic regression equation to screen for diabetes: development and validation. Diabetes Care. 25 (Nov), 1999–2003 (2002).

ElMoaqet, H., Tilbury, D. M. & Ramachandran, S. K. Multi-Step ahead predictions for critical levels in physiological time series. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 46 (Jul), 7 (2016).

Yang, J., Li, L., Shi, Y. & Xie, X. An ARIMA model with adaptive orders for predicting blood glucose concentrations andhypoglycemia. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 23 (3), 1251–1260 (May, 2019).

Alfian, G. et al. Blood glucose prediction model for type 1 diabetes based on artificial neural network with time-domain features. Biocybernetics Biomedical Eng. 40 (4), 1586–1599 (2020). Oct-Dec.

Perez-Gandia, C. et al. Artificial neural network algorithm for online glucose prediction from continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 12 (Jan), 1 (2010).

Gu, K., Dang, R. & Prioleau, T. Neural Physiological Model: A Simple Module for Blood Glucose Prediction (IEEE, 2020).

Li, K. et al. A deep learning framework for accurate glucose forecasting. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 24 (Feb), 2 (2020).

Dong, Y., Wen, R., Li, Z., Zhang, K. & Zhang, L. Clu-RNN: A New RNN Based Approach To Diabetic Blood Glucose Prediction (IEEE, 2019).

Li, K., Daniels, J., Liu, C., Herrero, P. & Georgiou, P. Convolutional recurrent neural networks for glucose prediction. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 24 (Feb), 2 (2020).

Aliberti, A. et al. A Multi-Patient Data-Driven approach to blood of glucose prediction. Ieee Access. 7, 69311–69325 (2019).

El Idrissi, T. & Idri, A. Deep Learning for Blood Glucose Prediction: Cnn Vs Lstm (Springer, 2020).

Tena, F., Garnica, O., Davila, J. L. & Hidalgo, J. I. Aug 1. An LSTM-based Neural Network Wearable System for Blood Glucose Prediction in People with Diabetes. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform, PP (2023).

Chen, J., Li, K., Herrero, P., Zhu, T. & Georgiou, P. Dilated Recurrent Neural Network for Short-time Prediction of Glucose Concentration. City, (2018).

Zhu, T., Li, K., Chen, J., Herrero, P. & Georgiou, P. Dilated recurrent neural networks for glucose forecasting in type 1 diabetes. J. Healthc. Inf. Res. 4 (Sep), 3 (2020).

Jaloli, M. & Cescon, M. Long-Term prediction of blood glucose levels in type 1 diabetes using a CNN-LSTM-Based deep neural network. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 17 (Nov), 6 (2023).

Lu, X. & Song, R. A Hybrid Deep Learning Model for the Blood Glucose Prediction (IEEE, 2022).

Song, W., Cai, W., Li, J., Jiang, F. & He, S. Predicting Blood Glucose Levels with EMD and LSTM Based CGM Data (IEEE, 2019).

Shuvo, M. M. H. & Islam, S. K. Deep multitask learning by stacked long Short-Term memory for predicting personalized blood glucose concentration. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. PP, 3 (Jan 2), 1612–1623 (2023).

Lee, S. M., Kim, D. Y. & Woo, J. Glucose transformer: forecasting glucose level and events of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. PP, 3 (Feb 2), 1600–1611 (2023).

Daniels, J., Herrero, P. & Georgiou, P. A multitask learning approach to personalized blood glucose prediction. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Inf. 26, 1 (2021).

Yang, M., Dave, D., Erraguntla, M., Cote, G. L. & Gutierrez-Osuna, R. Joint Hypoglycemia Prediction and Glucose Forecasting Via Deep multi-task Learning (IEEE, 2022).

Steininger, M., Kobs, K., Davidson, P., Krause, A. & Hotho, A. Density-based weighting for imbalanced regression. Mach. Learn. 110 (Aug), 8 (2021).

Chawla, N. V., Bowyer, K. W., Hall, L. O. & Kegelmeyer, W. P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 16, 321–357 (2002).

Aguiar, G., Krawczyk, B. & Cano, A. A survey on learning from imbalanced data streams: taxonomy, challenges, empirical study, and reproducible experimental framework. Mach. Learn. Jun 29, 1–79 (2023).

Branco, P., Torgo, L. & Ribeiro, R. P. SMOGN: a pre-processing Approach for Imbalanced Regression (PMLR, 2017).

Huang, W. & Zhang, T. Multi Domain Imbalanced Regression (.

Chen, H. Y. & Chao, W. L. On bridging generic and personalized federated learning for image classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.00778 (2021).

Silva, S. et al. Federated Learning in Distributed Medical Databases: Meta-analysis of large-scale Subcortical Brain Data (IEEE, 2019).

Yan, Z., Wicaksana, J., Wang, Z., Yang, X. & Cheng, K. T. Variation-aware federated learning with multi-source decentralized medical image data. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Inf. 25, 2615–2628 (2020).

Yuan, B., Ge, S. & Xing, W. A federated learning framework for healthcare iot devices. arXiv preprint arXiv:.05083 (2020). (2020). (2005).

Brisimi, T. S. et al. Federated learning of predictive models from federated electronic health records. Int. J. Med. Inf. 112, 59–67 (Apr, 2018).

Grama, M. et al. Robust aggregation for adaptive privacy preserving federated learning in healthcare. arXiv preprint arXiv:.08294 (2020). (2020). (2009).

Moshawrab, M., Adda, M., Bouzouane, A., Ibrahim, H. & Raad, A. Reviewing Federated Machine Learning and Its Use in Diseases Prediction. Sensors (Basel), 23, 4Feb 13 2112. (2023).

Nguyen, D. C., Ding, M., Pathirana, P. N. & Seneviratne, A. Blockchain and AI-Based solutions to combat coronavirus (COVID-19)-Like epidemics: A survey. IEEE Access. 9, 95730–95753 (2021).

Deng, T., Hamdan, H., Yaakob, R. & Kasmiran, K. A. Personalized federated learning for In-Hospital mortality prediction of Multi-Center ICU. Ieee Access. 11, 11652–11663 (2023).

Kerkouche, R., Acs, G., Castelluccia, C. & Genevès, P. Privacy-preserving and bandwidth-efficient federated learning: An application to in-hospital mortality prediction. City, (2021).

Vaid, A. et al. Federated learning of electronic health records to improve mortality prediction in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: machine learning approach. JMIR Med. Inform. 9 (1), e24207 (Jan, 2021).

Lincy, M. & Kowshalya, A. M. Early detection of type-2 diabetes using federated learning. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 12, 257–267 (2020).

Liu, D., Dligach, D. & Miller, T. Two-stage Federated Phenotyping and Patient Representation Learning (NIH Public Access, 2019).

Liu, D. & Miller, T. Federated pretraining and fine tuning of bert using clinical notes from multiple silos. arXiv preprint arXiv:.08562 (2020). (2020). (2002).

Antunes, R. S., da Costa, C. A., Küderle, A., Yari, I. A. & Eskofier, B. Federated learning for healthcare: systematic review and architecture proposal. Acm Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 13, 1–23 (Aug, 2022).

Nguyen, D. C. et al. Federated learning for smart healthcare: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR). 55 (3), 1–37 (2022).

Rieke, N. et al. The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 1 (2020).

Xu, J. et al. Federated learning for healthcare informatics. J. Healthc. Inf. Res. 5 (1), 1–19 (2021).

Astillo, P. V. et al. Federated intelligence of anomaly detection agent in IoTMD-enabled diabetes management control system. Future Generation Comput. Syst. 128, 395–405 (2022).

De Falco, I. et al. A Federated Learning-Inspired Evolutionary Algorithm: Application to Glucose Prediction. Sensors (Basel), 23, 6Mar 8 2957. (2023).

Islam, H. & Mosa, A. A Federated Mining Approach on Predicting diabetes-related Complications: Demonstration Using real-world Clinical Data (American Medical Informatics Association, 2021).

Li, T., Sahu, A. K., Talwalkar, A. & Smith, V. Federated learning: Challenges, Methods, and future directions. IEEE. Signal. Process. Mag. 37 (May), 3 (2020).

Mammen, P. M. Federated learning: Opportunities and challenges. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.05428 (2021).

Niknam, S., Dhillon, H. S. & Reed, J. H. Federated learning for wireless communications: Motivation, Opportunities, and challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 58 (Jun), 6 (2020).

Kairouz, P. et al. Advances and Open Problems in Federated Learning. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning, 14, 1–2 1-210. (2021).

Shaik, T. et al. FedStack: Personalized activity monitoring using stacked federated learning. Knowledge-Based Systems, 257Dec 5 109929. (2022).

Chen, Y. Q., Qin, X., Wang, J. D., Yu, C. H. & Gao, W. FedHealth: A federated transfer learning framework for wearable healthcare. IEEE. Intell. Syst. 35, 4 (2020). Jul-Aug.

Wu, Q., Chen, X., Zhou, Z., Zhang, J. & Fedhome Cloud-edge based personalized federated learning for in-home health monitoring. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 21, 2818–2832 (2020).

Banos, O. et al. mHealthDroid: a Novel Framework for Agile Development of Mobile Health Applications (Springer, 2014).

Banos, O. et al. Design, implementation and validation of a novel open framework for agile development of mobile health applications. Biomed. Eng. Online. 14 (Suppl 2), S6 (2015).

McMahan, B., Moore, E., Ramage, D., Hampson, S. & Arcas, B. A. y Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. PMLR, City, (2017).

Dinh, T., Tran, C., Nguyen, J. & N. and Personalized federated learning with Moreau envelopes. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 21394–21405 (2020).

Wang, K. et al. Federated evaluation of on-device personalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:.10252 (2019). (2019). (1910).

Piao, C. et al. Privacy preserved blood glucose level Cross-Prediction: an asynchronous decentralized federated learning approach. IEEE J. Biomedi. Health Info. (2025).

Rad, F. S. & Li, J. Privacy-Preserving glycemic management in type 1 diabetes: development and validation of a multiobjective federated reinforcement learning framework. JMIR Diabetes. 10, 1 (2025). e72874.

Marling, C. & Bunescu, R. The OhioT1DM Dataset for Blood Glucose Level Prediction: Update 2020 (NIH Public Access, 2020).

Wadwa, R. P., Laffel, L. M., Shah, V. N. & Garg, S. K. Accuracy of a Factory-Calibrated, Real-Time continuous glucose monitoring system during 10 days of use in youth and adults with diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 20 (6), 395–402 (Jun, 2018).

Jeon, J. et al. Predicting glycaemia in type 1 diabetes patients: experiments in feature engineering and data imputation. J. Healthc. Inf. Res. 4 (Mar), 1 (2020).

Jacobs, P. G. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning for improving glycemic control in diabetes: best practices, pitfalls, and opportunities. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 17, 19–41 (2023).

Morid, M. A., Sheng, O. R. L., Kawamoto, K. & Abdelrahman, S. Learning hidden patterns from patient multivariate time series data using convolutional neural networks: A case study of healthcare cost prediction. J. Biomed. Inform. 111, 103565 (2020).

Yu, L. et al. Spectrum prediction based on Taguchi method in deep learning with long short-term memory. IEEE Access. 6, 45923–45933 (2018).

Clarke, W. L., Cox, D., Gonder-Frederick, L. A., Carter, W. & Pohl, S. L. Evaluating clinical accuracy of systems for self-monitoring of blood glucose. Diabetes Care. 10, 5 (1987). Sep-Oct.

Contreras, I., Bertachi, A., Biagi, L., Vehí, J. & Oviedo, S. Using Grammatical Evolution to Generate Short-term Blood Glucose Prediction Models. City, (2018).

Zhu, T., Yao, X., Li, K., Herrero, P. & Georgiou, P. Blood glucose prediction for type 1 diabetes using generative adversarial networks. City, (2020).

Kriventsov, S., Lindsey, A. & Hayeri, A. The Diabits App for Smartphone-Assisted Predictive Monitoring of Glycemia in Patients With Diabetes: Retrospective Observational Study. JMIR Diabetes, 5, 3Sep 22 e18660. (2020).

Hameed, H. & Kleinberg, S. Comparing Machine Learning Techniques for Blood Glucose Forecasting Using free-living and Patient Generated Data (PMLR, 2020).

De Bois, M., Yacoubi, E., Ammi, M. & M. A. and Adversarial multi-source transfer learning in healthcare: application to glucose prediction for diabetic people. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 199, 105874 (Feb, 2021).

De Bois, M., Yacoubi, M. A. E. & Ammi, M. GLYFE: review and benchmark of personalized glucose predictive models in type 1 diabetes. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 60 (1), 1–17 (Jan, 2022).

Yang, T., Yu, X., Ma, N., Zhang, Y. F. & Li, H. R. Deep representation-based transfer learning for deep neural networks. Knowledge-Based Systems, 253Oct 11 109526. (2022).

De Falco, I. et al. An evolution-based Machine Learning Approach for Inducing Glucose Prediction Models (IEEE, 2022).

Zhu, T., Li, K., Herrero, P. & Georgiou, P. Personalized blood glucose prediction for type 1 diabetes using evidential deep learning and Meta-Learning. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 70 (Jan), 1 (2023).

Yang, G., Liu, S., Li, Y. & He, L. Short-term prediction method of blood glucose based on Temporal multi-head attention mechanism for diabetic patients. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 82, 104552 (2023).

Rubin-Falcone, H., Lee, J. & Wiens, J. Forecasting with sparse but informative variables: a case study in predicting blood glucose. City, (2023).

Shuvo, M. M. H., Titirsha, T., Gonzalez, G. L. & Islam, S. K. Enhancing personalized blood glucose prediction: deep learning insights from ablation study on wearable sensor data. IEEE Access (2024).

Moon, K., Kim, J., Yoo, S. & Cho, J. Personalized blood glucose prediction in type 1 diabetes using meta-learning with bidirectional long short term memory-transformer hybrid model. Sci. Rep. 15, 1 (2025).

Ghimire, S., Celik, T., Gerdes, M. & Omlin, C. W. Deep learning for blood glucose level prediction: how well do models generalize across different data sets? Plos One. 19, 9 (2024). e0310801.

Gallardo, C., García-Sáez, G., Subías, D., Rigla, M. & Hernando, M. E. Deep Transfer Learning for Glucose Prediction Adding Physical Activity Data in Type 1 Diabetes (IEEE, 2025).

Khamesian, S., Arefeen, A., Grando, M. A., Thompson, B. M. & Ghasemzadeh, H. Type 1 diabetes management using glimmer: Glucose level indicator model with modified error rate. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.14183 (2025).

Kalita, D. & Mirza, K. B. Multivariate glucose forecasting using deep multihead attention layers inside neural basis expansion networks. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Informatics (2025).

Shen, Y. & Kleinberg, S. Personalized blood glucose forecasting from limited CGM data using incrementally retrained LSTM. IEEE Trans. Biomedical Engineering (2024).

Dayan, I. et al. C.-S. Federated learning for predicting clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Nature medicine, 27, 10 1735–1743. (2021).

Abbas, S. R., Abbas, Z., Zahir, A. & Lee, S. W. Federated Learning in Smart Healthcare: a Comprehensive Review on privacy, security, and Predictive Analytics with IoT Integration (MDPI, 2024).

Aleppo, G. et al. Integration of continuous glucose monitoring data into an electronic health record system: single-center implementation. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 19, 426–430 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Darpit Dave: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing Kathan Vyas: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, visualization, data curation, writing – review and editing Jagadish Kumaran Jayagopal: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, visualization, data curation, writing – review and editing Madhav Erraguntla: Conceptualization, investigation, project administration, writing – review and editing Alfredo Garcia: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing – review and editing Mark Lawley: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, project administration, resources, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

For the data used in the current work, all data collection and methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. An informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardian(s) for collection of data. Necessary experimental and data collection protocols were approved by Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Darpit, D., Vyas, K., Jayagopal, J.K. et al. A personalized federated learning-based glucose prediction algorithm for high-risk glycemic excursion regions in type 1 diabetes. Sci Rep 15, 38376 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22316-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22316-4