Abstract

Breast density (BD) is one of the major risk factors for breast cancer (BC) and has the potential to be used as an early marker. Puberty is a critical period for carcinogenesis, and identifying events that modify BD during this stage could aid in understanding future BC risk. The consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) has been associated with BC; however, evidence of their effect on BD, particularly in adolescents, is lacking. To assess the association between the intake of UPFs during the peripubertal period and BD measured at 4 years after menarche onset, absolute fibroglandular volume (AFGV) and the percentage of fibroglandular volume (%FGV) were used. The Growth and Obesity Cohort Study is a longitudinal study of 550 girls recruited in 2006 at daycare centers in the southeastern area of Santiago, Chile. We measured the %FGV and AFGV via dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) 4 years after menarche. Girls had at least one 24-h dietary recall survey (R24H) during the peripubertal period. Simple and multiple linear regression models were used to evaluate the associations between UPF consumption (calories and grams, categorized in quartiles according to the sample distribution) and BD outcomes, adjusting for confounders such as birth weight, body mass index, tobacco use, physical activity, menstrual cycle stage, maternal education, age at menarche, total energy consumption, and maternal BD. Data from 330 girls revealed an average daily intake of 1849 kcal (41.67% from UPFs). No consistent associations were observed between UPF intake and %FGV and AFGV.]. Stratification by menstrual cycle phase revealed a significant increase in %FGV and AFGV for Q2 vs. Q1 UPF intake as a percentage of grams in the follicular stage [β: 0.12; 95% CI 0.01, 0.22 and β: 0.25; 95% CI 0.07, 0.43, respectively]. UPF consumption during puberty showed no consistent association with BD, except in girls whose UPF consumption was measured during the follicular phase. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and understand the effects of food processing on BD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer and leading cause of cancer-related death among women worldwide1. Breast density (BD) is a key risk factor for BC and holds promise as an early marker2,3,4. BD is a mammographic concept that corresponds to the proportion of epithelial and stromal tissue (fibroglandular tissue) in relation to adipose tissue3,5. Women with high BDs (> 75%) face a two- to fivef-old increased risk of BC compared with those with low BDs (< 5%)3,5,6,7.

Puberty is a period of rapid fibroglandular tissue expansion, heightened cell proliferation, and vulnerability to external stimuli, hormonal changes, and carcinogenesis8,9,10,11,12,13. Understanding the factors that influence BD during this window of susceptibility is crucial for improving future BC risk assessments8,11. BD is highest after puberty onset and declines thereafter8,14 and is potentially modifiable by environmental factors such as nutrition15,16,17. Therefore, understanding which events can modify breast density at young stages of life could help to better understand the future risk of breast cancer8,11.

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are products made from other foods after multiple physical, biological, and/or chemical processes18,19. They are profitable, highly palatable and ready-to-eat foods that contain industrial ingredients and additives20,21. In recent decades, their consumption has contributed between 25 and 50% of total daily energy intake, with an increasing trend every day19,22. UPFs have been linked to obesity, metabolic syndrome and chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, cardiovascular diseases and even cancer18,19,23. A recent study revealed that a higher intake of UPFs during adulthood was associated with an increase in BC18. The potential mechanisms could be an increase in insulin resistance, a known risk factor for BC19,24, or industrial processing, especially heat treatment, the addition of additives and contaminants in packaging, which are related to carcinogenesis, inflammation, dysbiosis and genotoxicity19,25,26,27,28. To our knowledge, no studies have assessed UPF consumption during puberty and its effect on BD. Thus, this study aims to investigate whether UPF intake during adolescence is associated with an increase in BD, taking into account body fatness. The study will be set in the Growth and Obesity Chilean Cohort Study (GOCS), a Chilean cohort study from Santiago. We collected routine dietary data during puberty and measured breast composition (percentages of fibroglandular volume (%FGV) and absolute fibroglandular volume (AFGV)) at 4 years after menarche onset.

Materials and methods

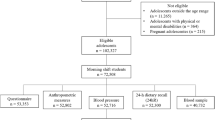

The present study is a longitudinal follow-up of the female participants enrolled in the “Chilean Growth and Obesity Study” (GOCs). GOCs is a longitudinal study that began in 2006 with the aim to evaluate growth, nutrition, and metabolic health in Chilean youth and included 1195 children between 2.6 and 4.0 years old. These children attended 54 nursery schools belonging to the National Nursery Schools Council Program (JUNJI) in the southeastern area of Santiago de Chile. JUNJI is a nationwide program that targets lower-middle- and low-income children. The participants were singletons who were born between 2002 and 2003 with birth weights of 2500–4500 g and no diagnosed physical or mental illnesses at the time of recruitment. Since 2006, children have attended the Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology (INTA) clinic for anthropometric evaluations. After 2011, assessments of sexual maturation (Tanner stages and menarche) were also introduced. In 2013, dietary evaluation via 24-h (24H) dietary recalls was initiated, and breast composition was measured 4 years after menarche via dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).

Among the 602 girls enrolled in 2006, for this study, we included 330 girls with complete breast density measurements (taken 4 years postmenarche) and 24H dietary recall data collected during the peripubertal period, defined as the phase from Tanner stage 2 to 1 year postmenarche.

Breast density assessment

BD was quantified via dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry(DXA). This method uses low-dose radiation (scan = 1.32 µSv), does not require breast compression29, is highly precise and has been validated for the measurement of BD in adolescents by Shepherd et al.30. This method was subsequently validated in the Chilean population at our institution, with a precision of 2.8% and an ICC greater than 0.917. DXA quantifies the absolute fibroglandular volume (AFGV; cm3) and percentage of fibroglandular volume (%FGV; defined as the sum of the AFGV divided by the total breast volume × 100). Measurements were performed at 4 years postmenarche (2016–2017) via Prodigy DXA system software (version 13.6, series 200,674; GE Healthcare). The left and right breasts were scanned, and we used the mean of both measurements. BD measurements were calculated via software developed by Sheperd et al.30. All measurements were performed by a trained DXA technician. More details of the procedure have been published elsewhere17.

Dietary assessment

Since 2012, dietary data have been collected at each visit via 24-h dietary recalls recorded in a specialized software program (SER-24H) developed by the Center of Research on Food Environment and Obesity Prevention (CIAPEC)31. The recalls were conducted by two trained dietitians via the USDA 5-Step Multiple-Pass Method29, which employs standardized questions and examples to help participants recall and describe their food intake from the previous day32. Additionally, the National Dietary Survey food atlas was used to assist subjects in estimating portion sizes and to enhance the reliability of dietary measurements33. This process enabled the estimation of food consumption in grams, which was subsequently analyzed for nutritional content. For this study, 24H dietary recalls from the peripubertal period (defined as Tanner stage 2 to 1 year postmenarche) were utilized.

Energy value and nutrient content were determined by mapping Chilean foods to the USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, following a harmonization process. A trained dietitian deconstructed Chilean mixed dishes that were not present in the USDA database for comparative purposes. For Chilean foods without a direct match, the closest nutrient profile in the USDA database was identified. To consider that a food met nutrient adequacy, a concordance rate between 80 and 120% of the reference value (± 20%) was required for each parameter analyzed34. Detailed information regarding the harmonization process has been published previously35,36.

The total energy intake (TE) was calculated as the average total energy intake (kcal/day) from all the 24H dietary reports. A crude method37 was used to identify physiologically implausible dietary recalls, excluding participants whose energy intakes fell outside the analysis range (< 500 kcal/day or > 3500 kcal/day).

The consumption of UPFs was estimated via the NOVA classification system, which categorizes foods on the basis of the degree and purpose of industrial processing. Foods and beverages were grouped into one of the following four categories: (1) unprocessed or minimally processed foods (e.g., fruits, vegetables, cereals, pasteurized milk, pure milk powder, yogurt, and fresh meat); (2) processed culinary ingredients (e.g., sugar, vegetable oils, salt, and butter); (3) processed foods (e.g., canned vegetables, bread, freshly made cheeses, fruits in syrup, and canned fish); and (4) UPFs (e.g., soft drinks, packaged sweet or savory snacks, confectionery, packaged bread and rolls, reconstituted meat products, and ready-to-eat/heat foods)38. UPF consumption was expressed as a proportion of total dietary intake, calculated both as the percentage of weight (grams/day) and the percentage of energy (kcal/day). The weight-based measure captured UPFs with low or zero calorie content, such as artificially sweetened beverages. The average proportion of UPF consumption across all dietary recalls was subsequently calculated for each participant in grams and calories. Finally, UPFs were categorized into quartiles on the basis of their distribution.

Covariates

Birth weight data were collected retrospectively from the clinics attended by the girls39. Anthropometric assessments were conducted every 6–12 months during follow-up to measure weight (Tanita 418 BC, with an accuracy of 0.1 kg) and height (Seca 222 measuring rod, with an accuracy of 1 mm) via standardized techniques performed by trained dietitians. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by height squared, and the Z score was estimated according to the growth curves provided by the World Health Organization (WHO)40.

Pubertal development was assessed via the Tanner scale by a trained dietician41, and the age of menarche onset was recorded every 6 months, either during clinical visits or via telephone. The stage of the menstrual cycle (follicular, luteal, or irregular cycles) at the time of DXA measurement was estimated on the basis of the date of the participant’s last menstrual period. Menstrual cycles shorter than 21 days or longer than 45 days were categorized as irregular.

To classify physical activity levels, the validated International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used42,43. Tobacco consumption was evaluated as “ever smoked” (yes/no), and oral contraceptive use (yes/no) was recorded at the time of BD measurement. Mothers reported their highest level of education in a questionnaire (> 12 years/ ≤ 12 years of formal education).

Statistical analysis

Independent, dependent, and confounding variables are presented as the means (SD), quartiles (Q), or percentages, as appropriate. For comparative analysis between response and confounding variables across quartiles of UPF intake, a nonparametric test was used to estimate the p value for trends across the quartiles.

Simple and multiple linear regression models were used to evaluate the associations between the proportion of UPFs in the diet (categorized in quartiles of grams/day and energy/day) and breast density (AFGV and %FGV). Since the distributions of AFGV and %FGV did not meet the assumption of normality (of the residuals) and homogeneity of variance, both variables were log-transformed prior to conducting the linear regression models. This transformation improved the symmetry of the distributions, reduced heteroscedasticity, and allowed for a more robust estimation of associations under the assumptions of linear modeling. For interpretation, results were back-transformed using (e(β)–1)*100, which reflects the approximate percentage change in the original scale of the outcome variable per unit increase in the predictor44,45. The models were adjusted for potential confounders including birth weight, BMI Z score, tobacco use, physical activity, menstrual cycle stage (follicular phase, luteal phase and irregular cycles), maternal education, age at menarche, age at DXA, and total energy intake (kcal/day). The selection of these variables was guided by existing literature, based on their known associations with both the exposure (UPF intake) and the outcome (breast density), while not being part of the causal pathway between them18,23,46,47,48,49. Adjustment for BMI Z-score was particularly important given its strong correlation with breast density; although BMI is also related to UPF intake and could be part of the pathway, our objective was to isolate the independent association between UPF and breast density. Similarly, total energy intake was included to control for overall dietary intake and better assess the specific impact of UPF consumption on the outcomes. Beta coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated, with the lowest quartile of consumption used as the reference category.

The results were further stratified according to the menstrual cycle phase (follicular or luteal phase) at the time of DXA assessment. This approach was taken based on the assumption that the menstrual cycle may act as an effect modifier in the relationship between UPF intake and breast density. Specifically, previous research has shown that breast tissue composition fluctuates across the menstrual cycle, with lower measurement sensitivity and higher variability observed during the luteal phase50,51,52.

Statistical analyses were performed via the STATA software program. All tests were two-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical review

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology (INTA), University of Chile (protocol approval number 020/2023), in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to the clinical evaluation, both participants and their parents or legal guardians received a detailed explanation of the breast DXA procedure, including positioning, radiation exposure, and potential risks, as described in Shepherd et al.30. Before the DXA scan, all participants and their parents agreed to conduct a pregnancy test to confirm the absence of pregnancy. All adolescent participants provided written assent, and their parents or legal guardians signed a written informed consent form authorizing their daughters’ participation, including the DXA scan and the associated procedures. All methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

We included 330 girls from the GOCS cohort whose breast density (AFGV and %FGV) was measured at 4 years postmenarche and whose prospective 24H dietary recall data were collected during the peripubertal period (from Tanner stage 2 to 1 year postmenarche). Girls excluded from the analysis were more likely to have a later age of menarche (12.2 years (SD = 1.2) vs. 11.8 years (SD = 0.9)), and their mothers were more likely to have 12 years or less of education (74.4% vs. 78.7%) (See supplementary material: Table S1).

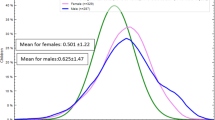

The mean age at the time of the DXA was 15.91 years (SD = 0.76), and 30.6% and 15.8% of the girls were classified as overweight or obese at 4 years postmenarche, respectively. A total of 53.64% of the girls were normal or low weight and had a fat percentage of 32.9% (SD = 6.65) 4 years postmenarche. The mean %FGV was 48.6% (SD = 15.6), the AFGV was 225.38 cm3 (SD = 108.23), and 70.34% of the girls were in the follicular stage of the menstrual cycle at the time of the DXA (See Table 1).

During the peripubertal period, the participants had an average of 3.4 (SD = 1.63) 24H dietary recalls, and 7.74% completed only one 24H dietary recall. The total energy intake was 1849.63 kcal (SD = 461.49), and 41.67% of the calories came from the NOVA 4 group (Table N°1). Girls in the highest quartile of calories consumed from NOVA 4 were more likely to have a higher total caloric intake. We did not observe any other associations with other covariates (See Table 2).

We next evaluated the associations between quartiles of UPF intake, measured as a percentage of calories and grams of the total diet, during the peripubertal period and the parameters of breast density (%FGV and AFGV). We found no association between quartiles of UPF intake (as a percentage of calories) and log-transformed %FGV in either the crude or adjusted models. Similarly, no associations were found between log-transformed %FGV and Q2, Q3, or Q4 of UPF intake (as a percentage of grams) compared with Q1 (See Table 3). Similar null associations were observed between the percentage of UPFs in calories and grams of total intake and log-transformed AFGV (See Table 4).

A stratified analysis was performed according to the stage of the menstrual cycle at the time of BD measurement, 17 girls had irregular cycles (5.2%) and were not included in this analysis In the adjusted model, girls in Q2 of UPF consumption (as a percentage of grams) had 12% increase in %FGV [Q2 vs. Q1: ß: 0.12; 95% CI 0.01, 0.22] and a 25% increase of AFGV [Q2 vs. Q1: ß: 0.25; 95% CI 0.07, 0.43] than those in Q1 during the follicular phase, however we did not observe differences comparing Q3 and Q4 against Q1. No significant associations were found between quartiles of UPF intake (as a percentage of calories) and log-transformed %FGV or AFGV. No significant associations were observed for participants in the luteal phase (See Table 5).

Discussion

To our knowledge, no previous study has assessed the association between UPF consumption and BD in adolescents. In our cohort, 42% of the total calories were derived from UPFs, a proportion similar to that reported in other studies53,54. However, we did not observe a consistent association between UPF intake, either in calories or grams, and %FGV or AFGV. An association was detected only when stratifying by menstrual cycle phase: girls who consumed a higher percentage of UPF grams (Q2 vs. Q1) during the peripubertal period had higher %FGV and AFGV in the follicular phase. This association, however, was not consistent across higher quartiles of UPF consumption (Q3 or Q4).

Our findings do not support those of Fiolet et al. (2018), who reported a positive association between UPF consumption and BC risk in the NutriNet-Santé cohort18. To our knowledge, no other studies have examined the relationship between UPFs, defined by the NOVA classification, and BD. However, some evidence links specific UPFs or dietary patterns high in UPFs with increased BD12,55,56,57,58,59,60. Studies in adult women have consistently shown positive associations between specific UPF intake and BD. For example, a British cohort in which data from birth were collected revealed that high total energy intake during adulthood was positively associated with BD measured at a mean age of 51.5 years (HR 0.12; 95% CI 0.01–0.23), but no association was observed for high energy intake at age 455. Similarly, a cross-sectional study in Quebec revealed that sugary drink consumption was positively associated with AFGV in both premenopausal women and all women (p trend < 0.05)56.

In contrast, studies in adolescents have yielded more contradictory results. The DISC06 cohort revealed an association between high carbohydrate and sucrose intake during adolescence and %FGV (mean = 17.2% (Q1) vs. 22.3% (Q4); p trend = 0.02)12. The NHS II study in the USA also revealed that higher intake of animal fats in adolescence was associated with increased premenopausal BD (mean = 43.1% (Q4) vs. 32.9% (Q1); p trend = 0.03)58. Our group previously reported that consuming more than 125 g of mixed dairy drinks during puberty increased the %FGV by 4.5% compared with those who did not (β: 4.5, 95% CI 0.9–8.1; p trend = 0.007)59. As mixed dairy beverages are usually high in sugar and/or sweeteners, a follow-up study by Yoon et al. (2022) did not observe any associations between sugary drink consumption and AFGV, %FGV, or total breast volume. They speculated that this null finding may reflect differential effects of sugar sources, as their study could not distinguish between sugars such as sucrose and fructose, which may have differential impacts on body development. Additionally, they did not include non-sugary drinks in their analysis60. In our study, we observed a positive association between the second quartile of the percentage of grams of UPF consumption and %FGV and AFGV during the follicular phase. A possible explanation for the lack of consistent associations in our study may be that we did not analyze the different sources of UPFs, which could have had a differential impact on this association.

Unlike previous studies, we accounted for the menstrual cycle in our analysis and found a small association when stratifying by cycle phase. This approach was based on evidence showing that breast cancer screening in premenopausal women tends to be less sensitive during the luteal phase61. Breast density is known to fluctuate across the menstrual cycle, with decreased measurement sensitivity and increased proliferative and apoptotic activity reported during the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase62. Several studies have described a marginal increase in breast density during the luteal phase, which appears to be driven primarily by a reduction in non-dense tissue rather than an increase in dense tissue52,61,62,63,64. Given these hormonal fluctuations, menstrual cycle phase could act as an effect modifier, and different associations might be expected when comparing the follicular and luteal phases51,52. In our study, we observed an increase in %FGV and AFGV associated with UPF intake (in grams) only when comparing Q2 vs. Q1 during the follicular phase, supporting the hypothesis that menstrual cycle may act as an effect modifier. However, no significant differences were observed when comparing Q3 or Q4 with Q1, suggesting the absence of a clear linear trend and raising the possibility that the observed association is marginal.

The lack of a significant association in the overall sample and the limited association observed in the stratified analysis could be due to underreporting in dietary recalls. The mean caloric intake during Tanner stage 2- to 1-year postmenarche was 1849 kcal/day, with UPF consumption accounting for 41.67% of total calories. A recent study by Neri et al. (2022), using dietary data from several countries, revealed that UPF intake in Chilean children and adolescents represented 27–44% of total calories, which aligns with our findings54. However, underreporting is common, with studies showing that young individuals underestimate energy intake by 20–21%65,66,67,68,69. Furthermore, individuals with obesity are more likely to underreport both total energy and UPF intake65,66,67. This could explain the nonsignificant downward trend in BMI Z scores as UPF consumption increased. Underreporting may result from inaccurate portion size estimation, failure to record daily dietary intake, or both68. However, to obtain a more precise assessment of usual intake, we conducted multiple 24-h dietary recalls67. On average, participants completed 3.4 24H recalls, with only 7.74% having just one. To further assist participants in accurately defining portion sizes and enhance the reliability of our estimates, we utilized the National Dietary Survey food atlas33.

Our study is not without limitations that may have influenced our results. As mentioned earlier, self-reported dietary data are prone to measurement errors, which may affect the accuracy of usual dietary intake. However, most participants completed more than one 24-h dietary recall, which provides a more representative picture of their typical diet and helps limit random variation in self-reports. Second, some ambiguity in food classification under the NOVA system cannot be ruled out. In this context, it is important to examine the specific sources of the foods classified as UPFs. Another limitation is the population sample, which consisted primarily of lower-middle- and low-income children, limiting the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Additionally, the relatively short period between exposure and the measured outcomes restricted our ability to assess long-term associations. Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. It is longitudinal, with detailed and repeated assessments of dietary intake. We used 24-h dietary records instead of food frequency questionnaires, reducing recall bias and providing a more accurate and representative estimate of UPF intake. Moreover, we gathered detailed anthropometric data, pubertal staging, and breast density (BD) measurements, all of which were collected by trained professionals via standardized methods.

In conclusion, while puberty and adolescence are recognized as critical windows for breast cancer risk, we did not find a significant association between UPF consumption during the peripubertal period and BD. A small effect was observed when the analysis was restricted to breast density measurements taken during the follicular phase, which warrants further investigation. Additional studies are needed to confirm these findings and better understand the effects of food processing on breast development.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

Ferlay, J. et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today (International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, 2020).

Ministerio de Salud, Gobierno de Chile. Guía de Práctica Clínica: Cáncer de Mama 174 (Minsal, Santiago, 2015).

McCormack, V. A. & dos Santos, S. I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 15(7), 1159–1169. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0101 (2006).

Eng, A. et al. Digital mammographic density and breast cancer risk: A case-control study of six alternative density assessment methods. Breast Cancer Res. 16(1), R45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-014-0045-0 (2014).

Boyd, N. F. et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. Cancer 109(3), 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22406 (2007).

Pettersson, A. et al. Mammographic density phenotypes and risk of breast cancer: A meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 106(1), 358. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djt358 (2014).

Chen, H. et al. Association of interactions between mammographic density phenotypes and established risk factors with breast cancer risk, by tumor subtype and menopausal status. Am. J. Epidemiol. 190(1), 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwaa102 (2021).

Boyd, N. F. et al. Breast tissue composition and susceptibility to breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 102(16), 1224–1237. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq229 (2010).

Binder, A. M. et al. Prepubertal and pubertal endocrine-disrupting chemical exposure and breast density among Chilean adolescents. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 27(10), 1491–1499. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0430 (2018).

Michels, K. B. et al. Association between indicators of systemic inflammation biomarkers during puberty with breast density and onset of menarche. Breast Cancer Res. 22(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-020-01296-5 (2020).

Houghton, L. C. et al. Pubertal timing and breast density in young women: A prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 21(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-019-1185-4 (2019).

Jung, S. et al. Intake of dietary carbohydrates in early adulthood and adolescence and breast density among young women. Cancer Causes Control. 29(5), 631–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-018-1043-0 (2018).

Boyd, N. F. et al. Breast tissue composition and other risk factors for breast cancer in young women: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Oncol. 10(6), 569–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70118-X (2009).

Pereira, A. et al. Determinants of volumetric breast density in Chilean premenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 162, 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4126-7 (2017).

Aitken, Z. et al. Screen-film mammographic density and breast cancer risk: A comparison of the volumetric standard mammogram form and the interactive threshold measurement methods. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 19, 418–428 (2010).

Tseng, M. & Byrne, C. Adiposity, adult weight gain and mammographic breast density in US Chinese women. Int. J. Cancer 128, 418–425 (2011).

Pereira, A. et al. Determinants of volumetric breast density in Chilean premenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 162, 343–352 (2017).

Fiolet, T. et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: Results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ 360, 322 (2018).

Monteiro, C. A., Moubarac, J. C., Cannon, G., Ng, S. W. & Popkin, B. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes. Rev. 14, 21–28 (2013).

Monteiro, C. A. et al. The un Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA Food Classification and the Trouble with Ultra-Processing Vol. 21, 5–17 (Public Health Nutrition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2018).

Romieu, I. et al. Consumption of industrial processed foods and risk of premenopausal breast cancer among Latin American women: The PRECAMA study. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 5, 1–9 (2022).

PAHO, OMS. Ultra-Processed Food and Drink Products in Latin America: Trends, Impact on Obesity, Policy Implications (Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health, Washington, DC, 2015).

Chang, K. et al. Ultra-processed food consumption, cancer risk and cancer mortality: A large-scale prospective analysis within the UK Biobank. EClinicalMedicine 56, 101840 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Nutr. J. 19, 86 (2020).

Nardocci, M. et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and obesity in Canada. Can. J. Public Health 110, 4–14 (2019).

Li, Y., Guo, L., He, K., Huang, C. & Tang, S. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice and human cancer: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Cancer 12, 3077–3088 (2021).

Marzbani, B. et al. Dietary patterns, nutrition, and risk of breast cancer: A case-control study in the west of Iran. Epidemiol. Health 41, e2019003 (2019).

Kain, J., Corvalán, C., Lera, L., Galván, M. & Uauy, R. Accelerated growth in early life and obesity in preschool chilean children. Obesity 17, 1603–1608 (2009).

Conway, J. M., Ingwersen, L. A., Vinyard, B. T. & Moshfegh, A. J. Effectiveness of the US department of agriculture 5-step multiple-pass method in assessing food intake in obese and nonobese women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 77, 1171–1178 (2003).

Shepherd, J. A. et al. Breast density assessment in adolescent girls using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry: A feasibility study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 17, 1709–1713 (2008).

Jensen, M. L., Corvalan, C., Reyes, M., Popkin, B. M. & Taillie, L. S. Snacking patterns among Chilean children and adolescents: Is there potential for improvement?. Public Health Nutr. 22, 2803–2812 (2019).

Moshfegh, A. J. et al. The US department of agriculture automated multiple-pass method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 88, 324–332 (2008).

Gattás, Z. V. Guía de la Composición Nutricional de Alimentos Naturales, de la Industria y Preparaciones Chilenas Habituales 2a edn. (Universidad de Chile, Chile, 2011).

Institute of Medicine; Food and Nutrition Board; Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes; Subcommittee on Interpretation and Uses of Dietary Reference Intakes; Subcommittee on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (National Academies Press, Washington, D.C, 2005).

Jensen, M. L., Corvalán, C., Reyes, M., Popkin, B. M. & Taillie, L. S. Snacking Patterns among Chilean Children and Adolescents: Is there Potential for Improvement? Vol. 22, 2803–2812 (Public Health Nutrition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2019).

Arroyo, A. M., Aguilar, C. C., Molina, X. P., Sanchez, X. C. & Fisberg, R. M. Dietary patterns of adolescents from the Chilean growth and obesity cohort study indicate poor dietary quality. Nutrients 12, 1–19 (2020).

Banna, J. C., McCrory, M. A., Fialkowski, M. K. & Boushey, C. Examining plausibility of self-reported energy intake data: Considerations for method selection. Front. Nutr. 4, 45. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2017.00045 (2017).

Monteiro, C. A. et al. Ultra-Processed Foods: What they are and how to Identify Them Vol. 22, 936–941 (Public Health Nutrition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2019).

Mueller, N. et al. Female offspring birth weight is associated with Body Mass Index, waist circumference and metabolic syndrome in Latin American women at 10-years postpartum. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 138, 90–98 (2018).

de Onis, M. et al. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ. 85, 660–667 (2007).

Pereira, A. et al. Breast bud detection: A validation study in the Chilean growth obesity cohort study. BMC Womens Health 14, 96 (2014).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-Country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35, 1381–1395 (2003).

Serón, P., Muñoz, S. & Lanas, F. Nivel de actividad física medida a través del cuestionario internacional de actividad física en población chilena. Rev. Med. Chil. 138, 1232 (2010).

Keene, O. N. The log transformation is special. Stat. Med. 14, 811–819 (1995).

Feng, C. et al. Log-transformation and its implications for data analysis. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 26, 105–109 (2014).

Jones, J. A. et al. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 115(3), 353–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2014.08.015 (2015).

Jacobs, I. et al. Br. J. Nutr. 128(11), 2278–2289. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114522000423 (2022).

Dorgan, J. F. et al. Height, adiposity and body fat distribution and breast density in young women. Breast Cancer Res. 14, R107 (2012).

Dorgan, J. F. et al. Menstrual and reproductive characteristics and breast density in young women. Cancer Causes Control 24, 1973–1983 (2013).

Morrow, M. et al. A prospective study of variability in mammographic density during the menstrual cycle. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 121(3), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-009-0496-9 (2010).

Pereira, A. et al. Breast composition during and after puberty: the Chilean growth and obesity cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 26, 45 (2024).

Hovhannisyan, G. et al. Differences in measured mammographic density in the menstrual cycle. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 18, 1993–1999 (2009).

Cediel, G. et al. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the Chilean diet. Public Health Nutr 21, 125–133 (2018).

Neri, D. et al. Ultraprocessed food consumption and dietary nutrient profiles associated with obesity: A multicountry study of children and adolescents. Obes. Rev. 23, e13387 (2022).

Mishra, G. D., dos Santos, S. I., McNaughton, S. A., Stephen, A. & Kuh, D. Energy intake and dietary patterns in childhood and throughout adulthood and mammographic density: Results from a British prospective cohort. Cancer Causes Control 22, 227–235 (2011).

Duchaine, C. S., Dumas, I. & Diorio, C. Consumption of sweet foods and mammographic breast density: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 14, 554 (2014).

Jung, S. et al. Dietary fat intake during adolescence and breast density among young women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 25, 918–926 (2016).

Bertrand, K. A., Burian, R. A., Eliassen, A. H., Willett, W. C. & Tamimi, R. M. Adolescent intake of animal fat and red meat in relation to premenopausal mammographic density. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 155, 385–393 (2016).

Gaskins, A. J. et al. Dairy intake in relation to breast and pubertal development in Chilean girls. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 105, 1166–1175 (2017).

Yoon, L., Corvalán, C., Pereira, A., Shepherd, J. & Michels, K. B. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and breast composition in a longitudinal study of Chilean girls. Breast Cancer Res. 24, 3 (2022).

Baines, C. J., Vidmar, M., McKeown-Eyssen, G. & Tibshirani, R. Impact of menstrual phase on false-negative mammograms in the Canadian national breast screening study. Cancer 80, 720–724 (1997).

Simpson, H. W., Cornelissen, G., Katinas, G. & Halberg, F. Meta-analysis of sequential luteal-cycle-associated changes in human breast tissue. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 63, 171–173 (2000).

Buist, D. S. M., Aiello, E. J., Miglioretti, D. L. & White, E. Mammographic breast density, dense area, and breast area differences by phase in the menstrual cycle. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev. 15, 2303–2306 (2006).

Ursin, G., Parisky, Y. R., Pike, M. C. & Spicer, D. V. Mammographic density changes during the menstrual cycle. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev. 10, 141–142 (2001).

Macdiarmid, J. & Blundell, J. Assessing dietary intake: Who, what and why of underreporting. Nutr Res Rev 11, 231–253 (1998).

Klesges, R. C., Eck, L. H. & Ray, J. W. Who underreports dietary intake in a dietary recall? Evidence from the second national health and nutrition examination survey. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 63, 438–444 (1995).

Vance, V. A., Woodruff, S. J., McCargar, L. J., Husted, J. & Hanning, R. M. Self-reported dietary energy intake of normal weight, overweight and obese adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 12, 222–227 (2009).

Bandini, L. G. et al. Comparison of high-calorie, low-nutrient-dense food consumption among obese and nonobese adolescents. Obes. Res. 7(5), 438–443 (1999).

Cunha, D. B., Da Costa, T. H. M., Da Veiga, G. V., Pereira, R. A. & Sichieri, R. Ultra-processed food consumption and adiposity trajectories in a Brazilian cohort of adolescents: ELANA study. Nutr. Diabetes 8(1), 28 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development from the Government of Chile (FONDECYT) grant 1230813; and the American Institute of Cancer Research (AIRC, grant No 961157).

Funding

National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development from the Government of Chile (FONDECYT) (1230813), American Institute of Cancer Research (961157).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Data Curation, Visualization M-L.G: Conceptualization, Investigation M.J: Resources, John Shepherd: Validation A.P: Conceptualization, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All clinical samples were collected with signed informed consent and ethics approval from.

Consent for publication

The content of this paper has not been submitted to any other scientific publications. All the authors have declared that no financial conflict of interest exists. All authors have approved the submission of this work for publication in Scientific Reports.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Devoto, A., Garmendia, M.L., Jacard, M. et al. Consumption of ultraprocessed foods and breast density in adolescence. Sci Rep 15, 39335 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23030-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23030-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Recreational physical activity and biomarkers of breast cancer risk in a cohort of adolescent girls

Breast Cancer Research (2026)