Abstract

Cellular senescence (CS) plays an important role in cancer development and treatment. However, the heterogeneity of CS among different types of cancer and its impacts on patient prognosis and therapy response remain to be fully elucidated. This study performed a comprehensive pan-cancer analysis on the CS landscape of 33 cancer types and 29 normal tissues. The molecular subgroups of CS were identified based on the expression of CS-related genes. Multi-platform data including prognosis, microbiota, immune microenvironment, multi-omics, and drug sensitivity were used to investigate the associations with the CS subgroups. Additionally, 12 single-cell datasets and 19 immunotherapy cohorts were collected to evaluate the CS subgroups. We characterized five pan-cancer CS subgroups with distinct biological features, named Inflamm-aging, DNA Damage Response, Autophagy, Immunologically Quiet, and Metabolic Disorder. The CS subgroups showed cancer-type and tissue-type specific distribution, and revealed significant associations with cancer prognosis, intratumoral microbiota, immunophenotypic features, and multi-omic alterations. The immunophenotypic features of the CS subgroups were verified by immunohistochemistry staining in tissue microarrays. Single-cell analyses indicated the CS heterogeneity among cancer types at the single-cell level. Furthermore, we developed a machine-learning model integrating CS-related cancer driver genes to infer the CS subgroups, and verified its prediction capability for immunotherapy response and prognosis in independent cohorts. Finally, potential therapeutic agents and targets were identified in the CS subgroups, which might have therapeutic implications for patients. Overall, this study provided a CS-derived classification scheme to expand the existing understanding of CS heterogeneity. The CS subgroups can reveal distinct CS states among cancer types and may contribute to improving personalized therapeutic strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is often recognized as an age-associated disease. The incidence of most cancers rises with age, and cancer is the leading cause of death in the elderly population1. With the extension of average life span, cancer has become an important public health problem that seriously threatens the health of elderly population and causes a huge socioeconomic burden to society2. Cellular senescence (CS), a common hallmark of cancer and aging, is defined as a state of irreversible cell cycle arrest with certain phenotypic changes, including alterations in the chromatin and secretome3. The accumulation of senescent cells in the tumor microenvironment has a dual effect on the cancer development4. CS can prevent the expansion of precancerous cells due to the activation of proliferation arrest5. Increased pro-inflammatory molecules secreted by senescent cells, known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), can promote immunosurveillance to inhibit tumorigenesis in premalignant lesions6. However, when senescent cells persist, their SASP forms an inflammatory microenvironment to facilitate senescence escape and malignant transformation, which contributes to cancer progression, adverse effects of treatment, and increased risk of relapse7,8,9. Dual functions of senescent cells have great inspirations for anti-tumor approaches. In recent years, CS has emerged as a therapeutic target for senotherapeutics that induce the selective cell death or suppress the detrimental extracellular effects of senescent cells10. Moreover, senescent cancer cells can also be used to develop efficient and protective anti-tumor immune responses11. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the role of CS in different types of cancer in order to improve therapeutic regimens and clinical outcomes.

Since CS can be triggered by various endogenous and exogenous stressors, such as telomere attrition, DNA damage, oncogene activation, epigenetic dysregulation, inflammation, and oxidative stress, there is a high degree of heterogeneity in the CS states of the tumor microenvironment6,12. Accumulating evidences indicate that CS is a dynamic process that involves multiple biological pathways from cell cycle exit to late senescence stage, further increasing its complexity13,14. Therefore, the CS states of various cancer types should be considered to contain more heterogeneous phenotypes with distinct molecular and functional features15. However, the exploration of CS heterogeneity is confronted with challenges due to the lack of universal and specific biomarkers for CS16. Presently, transcriptome profile analyses provided new insights into the gene signatures of senescent cells, which contributed to the characterization of CS17,18,19. In addition, recent studies calculated the CS scores to evaluate CS levels and clinical relevance at the pan-cancer level20,21,22. However, the heterogeneous features of CS phenotypes among different types of cancer and their impacts on patient prognosis and therapy response remain unclear and require further investigation.

In this study, we performed a comprehensive pan-cancer analysis on the CS landscape of 33 cancer types and 29 normal tissues. Based on literature-derived CS-related genes, we characterized five molecular subgroups of CS with heterogeneous biological features, cancer-type and tissue-type specificity. There were significant differences in cancer prognosis, intratumoral microbiota, immunophenotypic features, and multi-omic alterations among the CS subgroups. Single-cell analyses indicated the feasibility of applying CS-derived classification scheme to assess the CS heterogeneity at single-cell resolution. Furthermore, we identified cancer driver genes associated with the CS subgroups, and developed a machine-learning model to infer the CS subgroups and predict therapy response and prognosis in immunotherapy cohorts. Finally, potential therapeutic agents and targets were identified for each CS subgroup, which may contribute to precise cancer treatment.

Materials and methods

Clinical and molecular data resources

The multi-omic data of 33 cancer types (9712 samples) in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, including somatic mutation, copy number variation, RNA sequencing, DNA methylation, protein expression, and clinicopathological information were downloaded using the R package ‘TCGAbiolinks’ (v2.14.1) and the UCSC Xena (http://xena.ucsc.edu/public/). Genetic data of 29 normal tissues (9784 samples) were retrieved from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database (https://gtexportal.org/). Expression profiles and clinical information of independent studies were obtained through the accession numbers of the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/), and other publicly available resources. Alignment and quantification of raw data from the ENA database was performed using the Kalisto software23.

The 12 single-cell transcriptome datasets of 8 cancer types (271031 cells) included non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC, GSE117570, 11011 cells; GSE189357, 106793 cells), brain metastases from NSCLC (NSCLC-BM, GSE143423, 12193 cells), brain metastases from breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA-BM, GSE143423, 3629 cells), colorectal cancer (CRC, GSE146771, 15179 cells), ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV, GSE118828, 3066 cells), glioblastoma (GBM, GSE102130, 4058 cells; GSE131928-10X, 16201 cells; GSE131928-Smartseq2, 7930 cells), prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD, GSE141445, 33441 cells), skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM, GSE72056, 4645 cells), and basal cell carcinoma (BCC, GSE123813, 52885 cells)24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32.

The 19 immunotherapy cohorts contained a total of 1308 samples with 9 cancer types, including BRCA (Birkbak2018, GSE103668), NSCLC (Cho2020, GSE126045; Kim2020, GSE135222), CRC (Parikh2021, GSE179351; Pentheroudakis2014, GSE53127; Verstraete2015, GSE60331), GBM (Urup2017, GSE79671), leukemia (Ioannou2020, GSE148476; Loughran2015, GSE42664), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA, Ende2021, GSE165252), SKCM (Ascierto2017, GSE79691; Gide2019, PRJEB23709; Hugo2016, GSE78220; Riaz2017, GSE91061; Ulloa-Montoya2013, GSE35640; Zappasodi2021, GSE165278), bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA, Mariathasan2018, IMvigor210; Rose2021, GSE176307), and kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC, Braun2020, PMID32472114)33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50.

CS-related gene signature identification and clustering

We first collected the gene sets of replicative CS across 164 cell lines (totally 1259 genes)17, and identified 525 positive CS-related genes. We then performed consensus clustering analysis on the expression matrix of 525 gene signatures, as implemented in the R package ‘ConsensusClusterPlus’51. The cophenetic correlation coefficients were used to measure cluster stability, and accordingly a factorization rank of 5 was selected to achieve sufficiently stable clustering assignment (Fig. S1A). The HALLMARK signatures and C6 oncogenic signatures were obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB, https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb) to evaluate the association between the CS subgroups and cancer-related functional pathways. Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) algorithm was used to score these signatures through the R package ‘GSVA’52.

Immune microenvironment feature evaluation

Estimation of STromal and Immune cells in MAlignant Tumor tissues using Expression data (ESTIMATE) algorithm was used to quantify the proportions of immune cells (immune score) and stromal cells (stromal score) across cancer types53. The expression signatures of 28 immune cell types reported by Charoentong et al. were assessed by single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) to estimate the enrichment scores of immune cells using the R package ‘GSVA’54. The abundances of immune cell types were also measured by the R package ‘MCP-counter’ and CIBERSORT with the leukocyte signature matrix (LM22)55,56. DNA methylation-based MethylCIBERSOR method was used to evaluate the immune infiltration levels in various cancer types57.

The list of 78 immunomodulatory genes was received from a previous immunophenotypic study58. We used the R package ‘ChAMP’ to locate DNA methylation probes on genes, and evaluated the Spearman’s correlation coefficients between gene expression and DNA methylation of immunomodulators. Results were then filtered to preserve the probe sets with similar signed correlation, thereby reducing noise and increasing robustness. We also compared the copy number amplification and deletion frequencies of immunomodulatory genes between each CS subgroup samples and all samples. Cytolytic activity (CYT) score was calculated from the mean expression of granzyme A (GZMA) and perforin (PRF1). We further analyzed the Spearman’s correlation coefficients of ESTIMATE immune scores with CYT and PD-L1 expression at the pan-cancer level.

Multi-omic analysis of molecular alterations

To estimate the genomic instability in cancer samples of CS subgroups, we first identified the most frequent aberrations in somatic mutations, cancer driver genes, and copy number variations (CNVs). The list of 568 cancer driver genes were received from previous study59. CNV referred to the amplification or deletion of DNA fragments. The CNV frequencies of genes in TCGA pan-cancer datasets were evaluated using GISTIC v2.0. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), the small insertions and deletions were detected using Strelka v2.9. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) was calculated based on non-synonymous mutations through R package ‘maftools’. Transcription factor activity was analyzed using R package ‘decoupleR’.

Next, we analyzed the differentially expressed genes between each CS subgroup to distinguish candidate driver genes associated with CS. The Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P value < 0.01 was considered significant. Genome-scale CRISPR knockout screens was applied to assess the importance of CS-related cancer driver genes for tumor growth. The correlations between gene expression and DNA methylation, and copy number amplification/deletion of CS-related cancer driver genes were evaluated as previously described. We started with the UniProt canonical isoform sequences, and searched the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to obtain existing experimental structures60. We then performed homology modeling to revert experimental structures to wild-type sequences, and calculated protein folding energy (ΔΔGfold) for each variant using the FoldX force field61.

Single-cell and spatial transcriptome analysis

The expression matrix of single-cell data was imported into R package ‘Seurat’ (v4.4.0). The ‘NormalizeData’ function was applied to normalize raw counts, ‘CellCycleScoring’ function was applied to reduce cell cycle heterogeneity, and ‘FindVariableFeatures’ function was applied to screen highly variable genes for subsequent analysis. Harmony algorithm was used for multi-sample integration. Principal component analysis (PCA) was then performed to reduce data dimension, thereby decreasing the possibility of overfitting. Afterwards, we selected Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) algorithm for data visualization, and combined the ‘FindMarkers’ function and R package ‘SingleR’ to manually annotate cell clusters based on known markers. The CopyKAT method was used to estimate copy number profiles and distinguish cancer cells from normal cells62.

The initial processing steps for spatial transcriptome data were similar to typical single-cell sequencing. After data quality control, normalization, and PCA dimensionality reduction in the R package ‘Seurat’, we used the ‘SpatialDimPlot’ function to visualize the UMAP results. The ‘FindSpatiallyVariables’ function was performed to identify featured genes related to different spatial patterns. Cell clusters were then annotated using established markers. Spatial correlations among cells of the CS subgroups were analyzed by the R package ‘SPOTLight’. Cell-cell communication analysis was conducted using R package ‘CellChat’ to evaluate changes in the interaction intensity and signal activity between cell populations. SCENIC analysis was used to reconstruct gene regulatory network and identify important transcription factors in cells of the CS subgroups63.

Machine-learning model establishment

To establish a machine-learning model for predicting CS subgroups from CS-related cancer driver genes, we first utilized the combination of genetic algorithm and artificial neural network (GA-ANN) to select informative genes with significant importance64. The TCGA datasets were randomly divided into the training and testing sets using a ratio of 8:2. Next, four machine-learning algorithms were applied to build the model on the training set, including extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost, R package ‘XGBoost’), multi-logistic (R package ‘nnet’), support vector machine (SVM, R package ‘e1071’), and random forest (R package ‘randomForest’). The area under curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate the prediction performance of the model through R package ‘pROC’. Furthermore, we estimated the capability of the model for predicting patient immunotherapy responses and survival outcomes.

Cancer cell line and drug sensitivity analyses

Clinical annotations and expression profiles of human cancer cell lines (CCLs) were obtained from the Broad Institute Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) project (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ccle/)65. Drug sensitivity data of CCLs were download from the Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP, https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ctrp.v2.1/) and PRISM Repurposing dataset (https://depmap.org/portal/prism/). The AUC of dose-response curve was used to measure the drug sensitivity66. The CERES scores of genome-scale CRISPR knockout screens for 18,333 genes across 739 CCLs were achieved from the Cancer Dependency Map (DepMap) portal (https://depmap.org/portal/). The CERES scores were applied to estimate the gene-dependency levels from CRISPR essentiality screens. A lower CERES score indicated that the gene had greater importance for the cell growth and survival of CCLs.

Multiplex immunohistochemistry staining

Multi-organ tissue microarrays containing 61 pairs of 20 cancer types and adjacent tissues (n = 70) were obtained from Shanghai Zhuoli biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). According to the manufacturer’s instructions, multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC) staining assays were conducted using the Opal mIHC kit (PerkinElmer, NEL811001KT). Anti-CD45 (CST, 13917, 1/400), anti-MYC (Abcam, ab32072, 1/200), anti-FABP4 (Abcam, ab92501, 1/200), and anti-PD-L1 (CST, 13684, 1/200) were used as primary antibodies. Briefly, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue slides were baked at 65 °C for 1 h, dewaxed with xylene, and rehydrated by a graded series of ethanol (100%, 95%, and 70%). EDTA buffer was used for antigen retrieval, and 5% bovine serum albumin was used for blocking. The slides were incubated with the primary antibody for 1 h, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 10 min, and then incubated with Opal fluorophore solution for 10 min. We next repeated the same protocol to stain the rest primary antibodies, and finally applied DAPI for 5 min and covered the slides with antifade mounting medium. The tissue slides was visualized by Vectra 3 quantitative pathology imaging system (Akoya Biosciences), and further analyzed using inForm v2.4.2.

Flow cytometry analysis

Animal experimental protocols were approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Sichuan University (No. 20230307031). All methods were performed in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Guidelines of Sichuan University, and reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. Female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Nanjing Junke Bioengineering Co., Ltd. (China) and placed in an environment free of specific pathogens. After euthanizing mice by cervical dislocation, lung and liver tissues of mice aged 6–8 weeks or 20–22 months were digested in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco) containing 1 mg/mL collagenase I (Gibco), 0.5 mg/mL collagenase IV (Gibco), and 40 U/mL DNase I (Sigma) at 37 °C for 40–60 min, and the cell suspensions were filtered and resuspended. Cells were blocked with Fc receptor blocking (BioLegend, 101320), and then incubated with Live/Dead staining dye (Invitrogen, L34976) and surface antibodies at 4 °C for 30 min. Antibodies included FITC/PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD45, PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD3, PE/BV510 anti-CD8, APC anti-CD4, BV421 anti-CD62L, BV510 anti-CD44, PE-Cy7 anti-CD69, BV421 anti-PD-1, BV421 anti-CD11b, APC anti-CD11c, PE anti-Ly6G, FITC anti-F4/80, and PE-Cy7 anti-MHC II (all from BioLegend or BD Biosciences). Cells were analyzed using NovoCyte flow cytometer (ACEA), and data analysis was performed on Novoexpress v1.6.2.

Lung tumor model and multiplex immunoassay

The murine Lewis lung cancer (LLC) cells from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM medium and incubated in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. To build the orthotopic lung adenocarcinoma models, a mixture of 25 µL LLC cell suspensions (1 × 106 cells) and 25 µL Matrigel (Corning, 354248) were injected into the left lung of young (6–8 weeks) or old (20–22 months) female C57BL/6 mice. The bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected after inoculation for 14 days. Multiplex immunoassays were performed on 23 cytokines in BALF using the Bio-plex suspension array system based on the manufacturer’s instructions, including interleukin (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-13, and IL-17 A), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), chemokine (CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL11, and CXCL1), and colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF and GM-CSF).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted on R v4.2.3 or GraphPad Prism v8.0.2. The t-test was used to compare two groups of continuous variables with normal distribution, while Wilcoxon rank-sum test was selected for non-normally distributed data. The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to detect the statistical differences more than two groups, and Fisher’s exact test was conducted to estimate the differences between two categorical variables. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to measure the correlation between two variables. For survival analysis, the Kaplan-Meier curve and log-rank test were used to compare overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) results. Meanwhile, the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were evaluated by univariate Cox regression analysis using R package ‘survival’. The statistical significance corresponding to P values was as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns (no statistical significance), P ≥ 0.05.

Results

Characterization of the CS subgroups at the pan-cancer level

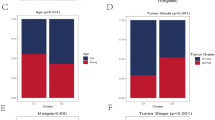

A graphic abstract of this study was presented in Fig. 1. To characterize the intratumoral CS states in 9712 bulk samples from 33 cancer types in the TCGA database, we collected 525 up-regulated genes from the previously reported gene sets of replicative CS17. We performed consensus clustering analysis to identify modules of CS-related genes (Fig. 2A, top panel), and then used five representative signatures that robustly reproduced modules to cluster all cancer types (Fig. 2A, middle panel). According to the distribution of signature scores (Fig. 2A, bottom panel), we revealed five main clusters “CS subgroups”, referred to as C1–C5. These CS subgroups showed distinct expression patterns of functional pathways based on the dominant features of their cancer samples (Figs. 2B and S1B). The CS subgroups spanned diverse cancer types and anatomical locations, while individual cancer types had great differences in the distribution of CS subgroups (Figs. 2C,D and S1C). Moreover, we categorized 9784 samples from 29 normal tissues in the GTEx database. The consistent preference of subgroup distribution indicated that cancer and tissue type may be crucial determinants of the CS states (Fig. 2E). We also integrated CS-related genes to define CS scores (Fig. 2F). The CS scores had positive associations with apoptosis and inflammation signals, and negative associations with DNA repair and cell cycle signals, which were in accord with the understanding of senescence (Fig. S1D–F). However, compared with CS scores, the CS subgroups can better reflect the cancer/tissue-type specificity and molecular heterogeneity of the CS states. For example, the CS scores of lung cancer and brain cancer were similar, while their dominant CS subgroups were obviously different. Meanwhile, the CS scores of lung and brain tissues were different. In summary, the proposed five subgroups can reveal the distinct biological features of CS (Fig. 2G).

Pan-cancer characterization of the CS subgroups in the tumor microenvironment. (A) Identification of gene expression signature modules and classification of the CS subgroups. Top panel: consensus clustering analysis based on CS-related gene expression signatures (rows and columns), which indicated five modules of shared correlations. Middle panel: representative signatures from each module (columns) were used to cluster cancer samples (rows). Bottom panel: distribution of signature scores among the five CS subgroups C1–C5 (rows), with dotted lines representing the median. (B) Differential expression of signaling pathways among the CS subgroups. (C) Circle heatmap showing the distribution of the CS subgroups in each cancer type. The subgroup proportion, cancer types, and tissue types were displayed from the outer to the inner side. (D) Distribution of cancer types in the CS subgroups. Bar charts reflected the proportion of each cancer type within each CS subgroup. (E) Distribution of the CS subgroups in different types of cancer and tissue. (F) Average CS scores of different cancer types (top panel) and tissue types (bottom panel). (G) Schematic description of differential features among the CS subgroups.

C1 (Inflamm-aging), the largest subgroup, had elevated expression of inflammatory response, IL-6/JAK/STAT3, T cell receptor (TCR), and B cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathways (Fig. 2B). Meanwhile, C1 showed the highest gene expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-2, IL-6, TGF-β, and IFN-γ (Fig. 2G). C1 was enriched in breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), mesothelioma (MESO), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), and kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) (Figs. 2C and S1C).

C2 (DNA Damage Response) was defined by increased expression of DNA repair and mismatch repair signaling pathways, along with cell cycle related genes (MYC, E2F), which exhibited moderate inflammatory response compared to C1. C2 was found in most genital system cancers, including uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS), endometrial carcinoma (UCEC), ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV), cervical cancer (CESC), and testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT). Bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA), colon (COAD) and rectal adenocarcinoma (READ) were also rich in C2.

C3 (Autophagy) displayed prominent autophagic and apoptotic signatures, as well as low to moderate inflammatory response. C3 was particularly dominant in thyroid carcinoma (THCA), adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), and kidney chromophobe (KICH).

C4 (Immunologically Quiet) was characterized by the weakest inflammatory response relative to other subgroups, with lowest TCR, BCR and inflammatory cytokine signals. C4 was comprised mostly of nervous system malignancies, including lower grade glioma (LGG), glioblastoma (GBM), pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PCPG).

C5 (Metabolic Disorder) was the smallest group of mixed tumors, which predominated in hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), acute myeloid leukemia (LAML), and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). C5 showed a stronger metabolic activity, with enhanced signals of oxidative phosphorylation, xenobiotic glucuronidation, adipogenesis, bile acid metabolism, and fatty acid metabolism.

Altogether, these five categories representing senescence features were different from traditional classifications, which can systematically delineate the CS landscape and provide more informative subgroups for cancers and tissues.

Impact of CS subgroup heterogeneity on cancer prognosis and microbiota

To explore the association between the CS subgroup heterogeneity and prognosis, the prognostic value of the CS subgroups was evaluated in pan-cancer and each cancer type (Supplementary data 1). Pan-cancer analysis demonstrated that OS rates varied significantly among five CS subgroups (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the CS subgroups were significantly associated with clinical outcomes in several cancer types, such as LGG, GBM, STAD, and LUSC (Fig. 3B). We then assessed the impact of immune cell infiltration on OS in each CS subgroup. The majority of infiltrating immune cells exhibited dual prognostic effects (Fig. 3C). For example, high monocyte infiltration was associated with poor OS in C1, C4, and C5, while better OS in C2 and C3 (Fig. 3D). We next found that the hallmark cancer-related functional pathways had significant effects on patient prognosis of the CS subgroups (Fig. 3E). Most cancer-related pathways were negatively associated with OS, while several pathways played dual roles in OS. For example, patients with highly KRAS signaling up displayed worse prognosis in C1, C2, and C4, but had improved prognosis in C3 and C5 (Fig. S2A). The crosstalk between the CS subgroups and cancer-related functional pathways also significantly influenced the prognosis of different cancer types (Figs. 3F and S2B). Moreover, we showed the association between OS and the metabolism signatures in each CS subgroup (Fig. S2C).

Impact of CS subgroup heterogeneity on clinical outcome and microbial distribution. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival (OS) among the five CS subgroups. (B) Significance of hazard ratio (HR) for the association of the CS subgroups with disease-free survival (DSS), OS, and progression-free interval (PFI) in each cancer type. (C) Forest plot showing the HRs that reflected the association between the OS and immune cell types in each CS subgroup. (D) Kaplan-Meier curves of OS among the CS subgroups stratified by the levels of monocyte infiltration. (E) HRs representing the association between OS and GSVA scores of the hallmark signatures in each CS subgroup. (F) HRs of the association between OS and GSVA scores of inflammatory response and KRAS signaling up pathways in each cancer type. (G) Expression of microbial genes at the phylum level among the CS subgroups. (H) Significantly up-regulated and down-regulated microbial genes at the genus level among the CS subgroups.

The intratumoral microbiota is an intrinsic component of the tumor microenvironment and involved in cancer progression, immune surveillance, and chemotherapy resistance67. Here, we analyzed the expression of microbial genes within tumors, and the distribution of intratumoral microbiota at the phylum and genus level varied among the CS subgroups (Fig. 3G,H). The C1 subgroup had higher levels of some microbiota compared to other subgroups, such as Cyanobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Chlorobi. Finally, we explored the impact of the interplay between the CS subgroups and microbiota on prognosis (Fig. S2D). Several microbiota were significantly associated with survival in specific CS subgroups, such as Firmicutes and Thermotogae (Fig. S2E). The correlation between microbial phyla and hallmark pathways was analyzed to show their functional implications (Fig. S2F). Collectively, these results suggested that the CS subgroup heterogeneity can effect cancer prognosis, which may be combined with infiltrating immune cells, cancer-related functional pathways, and intratumoral microbiota as feasible prognostic predictors.

Distinct immune microenvironments among the CS subgroups

To investigate the effect of senescence on tumor immunity, we first used ESTIMATE algorithm to evaluate the immune and stromal scores of cancer types and CS subgroups, and observed increased immune infiltration in C1 while reduced immune infiltration in C4 (Fig. 4A). Next, we performed ssGSEA on the expression signatures reported from Charoentong et al., MCP-counter, and CIBERSORT methods54,55,56 to reveal the composition and abundance of immune cells in these CS subgroups (Fig. 4A). The ssGSEA scores indicated that from C1 to C4, most types of immune cells showed a decreasing trend from immune-enriched to immune-depleted, such as CD8+ effector memory T (Tem), CD8+/CD4+ central memory T (Tcm), natural killer T, memory B, and activated dendritic cells (Fig. 4B). The elevated immune score in C5 was probably due to the interference from hematological and lymphatic cancers (Fig. 4C). The expression levels of PRF1 and CD69, which reflected the cytolytic and proliferative capacity, also decreased progressively from C1 to C4 (Fig. 4D). In addition, C1 showed higher gene expression of co-stimulators (CD28, ICOS, HLA-DRA, and CD40LG), cytotoxicity (GNLY, FASLG, and CCR6), and phagocytosis (CD163 and MRC1) than other subgroups (Fig. S3). Overall, the infiltration abundance and activity of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment were associated with the CS subgroups.

Immune microenvironment characteristics of the pan-cancer CS subgroups. (A) Heatmaps of immune gene signature scores for pan-cancer datasets in the CS subgroups. Top panel: immune scores and stromal scores evaluated by the ESTIMATE algorithm. Middle and bottom panel: profiles of infiltrating immune cell types from the Charoentong et al., MCP-counter or CIBERSOTR method. (B) The ssGSEA scores for infiltration abundances of 28 immune cell types among the CS subgroups through the Charoentong et al. method. (C) Pan-cancer immune infiltration scores using the DNA methylation-based MethylCIBERSOR method. (D) Expression of PRF1 and CD69 in the CS subgroups. (E) Expression and regulation of immunomodulators in the CS subgroups. From left to right: mRNA expression (median normalized expression levels); expression versus methylation (Spearman’s correlation between mRNA expression and DNA methylation β-value); amplification frequency (difference in copy number amplification fraction of an immunomodulatory gene between subgroup samples and all samples); and deletion frequency (difference in copy number deletion fraction). (F) Spearman’s correlation of immune scores (ESTIMATE) with cytolytic activity (CYT) score (x-axis) and PD-L1 expression (y-axis) in different cancer types. The gray dotted lines represented the P value of 0.01. Spearman’s correlation between immune scores and PD-L1 protein expression in LUAD, SKCM, and STAD. (G) Cancer types sorted by PD-L1 expression at transcriptional level (top panel) and protein level (bottom panel). (H) PD-L1 expression for each cancer type classified by the CS subgroups.

Immunomodulators are essential for cancer immunotherapy with various agonists and antagonists being applied to improve patient prognosis58. We found that the expression of immunomodulatory genes varied among the CS subgroups (Fig. 4E). Most of them were highly expressed in C1, including immune stimulators (e.g., CD28, CD80, ICOSLG, ITGB2) and inhibitors (e.g., PD-L1/CD274, CTLA4, BTLA, TIGIT). By comparison, IL12A, IL13, IFNA2, TLR4, and EDNRB were highly expressed in C4, and C5 had the highest expression of ARG1. DNA methylation of many immunomodulatory genes (e.g., PDCD1LG2, BTLA, CD27, LAG3) was negatively correlated with gene expression, indicating epigenetic silencing. In addition, C1 and C2 showed higher amplification and deletion frequencies of immunomodulatory genes, while C4 had fewer alterations. These significant differences in copy numbers of immunomodulatory genes may reflect a more direct regulation of the microenvironment by tumor cells. Cytolytic activity (CYT) score is an immune biomarker calculated from the mean of GZMA and PRF1 expression, which can represent the cytotoxicity of tumor-infiltrating T cells and predict response to immunotherapy68. Correlations of immune scores with CYT score and PD-L1 expression were both positive in multiple cancer types, such as LUAD, SKCM, and STAD (Fig. 4F). We then investigated important immunomodulators and found that PD-L1 expression was elevated in the C1 subgroup of most cancer types (Fig. 4G,H). PD-L1 is both an inhibitory marker and a potential indicator of T cell engagement, therefore its high expression may coexist with immune infiltration69. Therefore, the C1 subgroup of these cancers might be more sensitive to immunotherapy due to enhanced PD-L1 expression and adequate T-cell cytotoxicity.

To validate the immune infiltration levels and immunophenotypic features of the CS subgroups, we performed mIHC staining against CD45 (a common leukocyte antigen), MYC (a cell cycle related regulator), FABP4 (a protein involved in fatty acid metabolism), and PD-L1 in pan-cancer tissue microarrays. The expression of CD45, MYC, and FABP4 was relatively elevated in the C1, C2, and C5 cancers, respectively (Figs. 5A and S4A). The C1 and C2 exhibited stronger immune infiltration and PD-L1 expression, C3 and C5 showed low to moderate levels, while C4 was the weakest. These results were consistent with the previous bioinformatics analysis. Afterwards, we used flow cytometry to analyze the lung and liver tissues from young and old mice (Figs. 5B and S4B, C). Compared with the young group, increased infiltration of CD8+ T, CD8+ Tem, CD8+ Tcm, CD4+ Tem, activated T (CD69+ T), PD-1+ T, and neutrophils was observed in the lungs of old mice, indicating an activated inflammatory response (Fig. 5C,D). The infiltration of CD8+/CD4+ T, CD8+ Tem, CD4+ Tcm, activated CD8+ T, and dendritic cells was decreased in the liver of old mice than young mice (Fig. 5C,D). Moreover, we established the orthotopic LUAD models to detect multiplex cytokines in BALF (Fig. 5E). The immunoassays showed that the levels of SASP-related inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IFN-γ, TNF-α) were higher in the BALF of old mice with LUAD, exhibiting a C1 phenotype (Fig. 5F). These findings further confirmed the distinct impacts of senescence on the immune microenvironment of different cancers and tissues. In summary, our results revealed the differences in immune infiltration and immunophenotypic features among the CS subgroups at the pan-cancer level, which may have implications for the development of targets and strategies for immunotherapy.

Association of the CS subgroups with immune infiltration levels and immunophenotypic features. (A) Multiplex immunohistochemistry staining of CD45 (red), MYC (cyan), PD-L1 (pink), FABP4 (yellow), and DAPI (blue) in tissue microarrays of cancer patients. Scale bars represented 200 μm. (B–D) The lung and liver tissues from young (6–8 weeks) or old (20–22 months) C57BL/6 mice were used for flow cytometry analysis (n = 6 mice per group). Data were presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Unpaired t-test. (B) Representative scatterplots of CD8+/CD4+ naive T (Tnaive, CD44− CD62L+), effector memory T (Tem, CD44+ CD62L−), and central memory T (Tcm, CD44+ CD62L+) cells from CD45+ CD3+ CD8+/CD4+ cells. (C) The proportions of CD8+/CD4+ T, Tnaive, Tem, Tcm, CD69+ T, and PD-1+ T cells in CD45+ cells. (D) The proportions of neutrophils (CD45+ CD11c− CD11b+ Ly6G+), macrophages (CD45+ CD11c− CD11b+ F4/80+), conventional dendritic cells (CD45+ CD11c+ MHCII+), and alveolar macrophages (CD45+ CD11c+ CD11b− F4/80+) in CD45+ cells. (E) Establishement of orthotopic LUAD models in young (6–8 weeks) or old (20–22 months) C57BL/6 mice. (F) Comprision of cytokine levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of young and old mice with LUAD (n = 3 mice per group). Multiple t-tests adjusted by Holm-Sidak method.

Featured multi-omic alterations among the CS subgroups

Genomic instability and epigenetic alterations are shared hallmarks in cancer and aging. To explore the molecular alterations related to senescence in multiple cancers, we compared the genomic variation, gene expression, DNA methylation, and protein structure among the CS subgroups. We first investigate the mutational status of somatic mutations, cancer driver genes, and copy number amplification or deletion, which showed that genomic aberrations were more common in C1 and C2 (Fig. 6A). We then identified five mutational signatures in the pan-cancer datasets (Fig. S5A), which corresponded to the COSMIC mutational signatures70 (Fig. S5B). These CS subgroups showed different patterns of mutational signatures (Fig. S5C). Moreover, C1 and C2 displayed a higher SNP, mutation load, CNV burden, and genomic instability (Figs. 6B,C and S5D,E). We observed significant heterogeneity in the regulatory patterns of transcription factors among the CS subgroups (Fig. 6D). For instance, inflammation-related transcription factors (ANKRD1, EGR1, and STAT1) were up-regulated in C1, while proliferation-related transcription factors (E2F2 and MYBL2) were enriched in C2.

Multi-omic molecular alterations in the pan-cancer CS subgroups. (A) Heatmaps showing common alterations in somatic mutations, cancer driver genes, and copy number amplification or deletion in pan-cancer samples according to the CS subgroups. (B) Circular plots displaying the differences in single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and copy number variation (CNV) among the CS subgroups. (C) Tumor mutation burden (TMB), CNV burden, homologous recombination (HR), loss of heterozygosity (LOH), base excision repair (BER), and nucleotide excision repair (NER) levels in the CS subgroups. (D) Expression of transcription factors in the CS subgroups. (E) Heatmap of alteration frequencies in CS-related cancer driver genes. Color bars showed the proportions of alteration types for each gene (right panel) or cancer subtype (top panel). (F) Expression and regulation of cancer driver genes in the CS subgroups. From left to right: malignant degree (importance for tumor growth); mRNA expression (median normalized expression levels); expression vs. methylation (correlation between mRNA expression and DNA methylation β-value); amplification frequency (difference in copy number amplification fraction of a driver gene between subgroup samples and all samples); and deletion frequency (difference in copy number deletion fraction). (G) Histogram of CNV frequencies of driver genes in each cancer type. (H) Correlations of transcriptional expression with CNV and DNA methylation for driver genes in different cancer types. (I) Protein structures of driver genes common to the C1 and C2 subgroups. PEG3 and FAM153B mutations were clustered in protein functional domains. Color spheres represented mutations classified by mutation frequency. (J) Structure-based calculations of the effect of driver gene mutations on protein folding energy (ΔΔGfold).

We further identified the 10 most prominent cancer driver genes associated with each CS subgroup, and examined these gene alterations in various tumor subtypes (Figs. 6E and S5F). Interestingly, human papilloma virus (HPV)-negative HNSC detected more altered CS-related cancer driver genes than HPV-positive HNSC. Compared to other subtypes, CS-related oncogenic alterations were more common in Luminal A BRCA, isocitrate dehydrogenase wild-type (IDHwt) GBM, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated STAD, and chromosomal instability (CIN) gastrointestinal tumors (ESCA, COAD, and READ). Besides genomic aberrations, differential expression analysis was conducted to estimate alterations in the gene expression patterns of driver genes. Through genome-scale CRISPR knockout screens, we observed that some of these driver genes were important oncogene for tumor growth, such as PDGFRA in C1 and USP6 in C2 (Fig. 6F). Meanwhile, the majority of driver genes showed high expression levels in their respective CS subgroup. DNA methylation of several driver genes (e.g., ELF3, PLAG1, MAP2, KEL) was negatively correlated with gene expression, suggesting epigenetic silencing. Moreover, C1 and C2 exhibited more frequent amplification and deletion of driver genes, consistent with their greater genomic instability. We also evaluated the effects of CNV and DNA methylation on the expression of driver genes in each cancer type. The amplification or deletion of driver genes varied among different types of cancer (Fig. 6G). Additionally, the expression of driver genes was significantly associated with CNV (e.g., KLF5, TOP2A) or DNA methylation (e.g., ELF3, NBEA) in certain cancers (Fig. 6H), suggesting that the regulation of CS-related cancer driver genes might be specific among cancer types.

Considering the genomic instability of driver genes in the C1 and C2 subgroups, we further performed protein structural analysis and modeling to predict the potential functional consequences of common driver gene alterations in the two subgroups, including ABCB1, CDH11, CR1, FAM153B, MAP2, PEG3, PTPRD, and ZNF208. These mutations of the two subgroups were found at different domain interfaces of protein structures (Fig. 6I). ABCB1, FAM153B, and ZNF208 mutations in C1 showed higher protein folding energy, which were predicted to destabilize protein structure (Fig. 6J). In contrast, MAP2 and PTPRD mutations were considered more stable in C1, and might affect function by restricting the conformational change of proteins. Therefore, these driver genes in the C1 and C2 subgroups had different protein mutation domains and structural stability. Taken together, our results revealed the multi-omic profiles of CS-related cancer driver genes, indicating distinct multi-omic alterations related to differential CS states.

The CS States of cancer cells varied among different cancer types

To explore the CS heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment at single-cell resolution, we analyzed 12 single-cell datasets from various cancer types (Fig. S6A; Supplementary data 2). After data processing, we identified cell types and clustered them into major cell lineages (Fig. 7A–K). The dominant CS subgroups in cancer cells were heterogenous among different cancer types, while C1 was prominently distributed in stromal cells (mainly fibroblasts) of most cancer types (Fig. 7A). Specially, most cancer cells and stromal cells in GBM were classified into the C4 subgroup (Fig. 7F–H). However, by further comparing primary lesions and brain metastases of NSCLC, we observed that cancer cells were still mainly C3, and the proportion of C4 in stromal cells was relatively higher in brain metastases than primary lesions (Fig. 7B,C). These results indicated that the CS subgroup distribution in cancer cells may be cancer-type specific, depending on the type of cancer. These findings were consistent with previous results from bulk transcriptome analyses.

Single-cell transcriptome analysis of the CS subgroups in the tumor microenvironment. (A) Heatmaps showing the proportions of CS subgroups in different cell types from 11 single-cell datasets, labeled with cancer types and accession numbers in the GEO database. (B–K) Single-cell analysis of brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC-BM, GSE143423), NSCLC (GSE117570), brain metastases from breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA-BM, GSE143423), colorectal cancer (CRC, GSE146771), glioblastoma (GBM, GSE102130, GSE131928-10X, GSE131928-Smartseq2), ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV, GSE118828), prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD, GSE141445), and skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM, GSE72056) datasets. Top left or right panel: UMAP plots of cell clusters colored by the cell types or CS subgroups. Bottom left panel: distribution of CS subgroups in different cell types. Bottom right panel: distribution of cell types in each CS subgroup.

To investigate the spatial distribution and correlation of the CS subgroups in the tumor microenvironment, we further analyzed the NSCLC dataset (GSE189357) containing single-cell and spatial transcriptome profiles (Fig. 8A,B). In the spatial transcriptomic maps of tissue domains, we noticed that the C1 subgroup cells infiltrated markedly around the tumor (Figs. 8C and S6B). Meanwhile, the C1 subgroup cells had close colocalization and interaction with other subgroups (Fig. 8D). Enrichment analysis showed different up-regulated signaling pathways among the CS subgroups (Fig. S6C). We further examine the cell-cell communication in each CS subgroup. Compared to other subgroups, the strength of incoming and outgoing interactions was enhanced in malignant cells of C1 (Fig. S6D). Moreover, multiple ligand-receptor pairs were significantly up-regulated from malignant cells to themselves, as well as during the communication between malignant cells and stromal/immune cells in C1 (Figs. 8E and S6E). We next focused on the signals of immune checkpoints, inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, angiogenic factors, and antigen-presenting molecules, and found that C1 exhibited the strongest signals during cell-cell communication, indicating that the C1 subgroup cells played key roles in the tumor microenvironment (Figs. 8F and S6F). Moreover, each CS subgroup had its own transcription factors with significant regulatory intensities (Fig. S6G). Transcription factors such as PPARG, NR1H3, SAP30, RUNX1, and MEF2C played central roles in C1 (Fig. 8G). Above findings indicated the potential interactions between cell types in each CS subgroup, which would help to further investigate the communication patterns of the CS subgroups and their integrative roles in cancer progression and treatment response.

Single-cell and spatial transcriptome analysis of the CS subgroups in lung cancer. (A) Single-cell UMAP plots of cell types and CS subgroups in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC, GSE189357). (B) Distribution of CS subgroups (top panel) and expression of marker genes (bottom panel) in each cell type. (C) Spatial transcriptome visualization of cell types and CS subgroups in tissue domains (TD) of NSCLC (GSE189357). Representative images were displayed, and other TD images were provided in the supplementary materials. (D) Spatial correlations among cells classified by the CS subgroups in each TD. (E) Significant differentially expressed ligand-receptor pairs in the communication among cell types, with malignant cells used as signal targets. Red color indicated enhanced intercellular communication in the C1 subgroup compared to other subgroups. (F) Expression of ligand-receptor pairs in cell-cell communication among the CS subgroups. (G) Significant transcription factors of the C1 and C3 subgroups based on SCENIC analysis.

CS-related machine-learning model for predicting immunotherapy response

The above changes in immunity and angiogenesis in the tumor microenvironment inspired us to explore the association between the CS subgroups and immunotherapy response. In the single-cell dataset of BCC patients treated with anti-PD-1 (GSE123813), we examined the differential distribution of CS subgroups between pre- and post-treatment patients (Fig. 9A,B). The proportion of the C1 subgroup in responders was higher than that of non-responders. Compared with pre-treatment baseline, the proportion of the C1 subgroup in responders obviously increased after immunotherapy (Fig. 9C). Considering the specific expression of CS-related cancer driver genes in different CS subgroups, we further developed a machine-learning (ML) model integrating CS-related cancer driver genes (referred to as ML-CS) to infer the CS subgroups. Firstly, the GA-ANN was used to assess the importance of CS-related cancer driver genes (Fig. 9D). The top 35 CS-related cancer driver genes were included in subsequent modeling (Fig. 9E). The dataset of each cancer type was randomly divided into the training (80%) and testing (20%) sets. We next applied XGBoost, multi-logistic, SVM, and random forest algorithms to build ML-CS in the training set. Finally, ML-CS based on XGBoost achieved better performance in predicting the CS subgroups in both the training and testing sets (multi-class AUC = 0.9123; Fig. 9F).

Evaluation of CS-based machine learning models for predicting immunotherapy response. (A) Single-cell visualization of cell clusters in basal cell carcinoma (BCC) patients receiving anti-PD-1 immunotherapy (GSE123813). (B) Ratios of cell proportion before and after immunotherapy (top panel) and distribution of CS subgroups in each cell type (bottom panel). (C) Differences in the proportion of CS subgroups between responders and non-responders before and after immunotherapy. (D) The genetic algorithm-artificial neural network (GA-ANN) was used for feature selection. (E) The order of importance of CS-related cancer driver genes calculated using GA-ANN. (F) Comparison of multi-class AUCs estimated by four machine-learning models in the training and testing sets. (G–J) Application of CS-based machine-learning models in 19 immunotherapy cohorts. Top panel: expression of PD-1, PD-L1 and CTLA-4 in the CS subgroups. Bottom panel: (i) proportion of responders in each CS subgroup; (ii) proportion of CS subgroups in responders and non-responders before and after immunotherapy; (iii) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of CS subgroups.

To gain insights into the prediction capability of ML-CS for immunotherapy response, we retrieved 19 immunotherapy cohorts and utilized ML-CS to classify patients into different CS subgroups. The results demonstrated that the expression levels of PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 showed a decreasing trend from C1 to C5 in many types of cancer (Fig. 9G–J). Meanwhile, the percentage of responders to immunotherapy varied among the CS subgroups, which was highest in C1 and decreased progressively from C1 to C5 in different cancers, such as BRCA (Birkbak2018), NSCLC (Kim2020), ESCA (Ende2021), melanoma (Hugo2016), BLCA (Mariathasan2018), and KIRC (Braun2020). Similarly, compared with pre-treatment baseline, the proportion of the C1 subgroup increased in post- and on-treatment responders (Verstraete2015, Ende2021, Riaz2017, and Gide2019). We next evaluated the survival outcomes of patients and observed significant differences in OS and PFS among the CS subgroups. The subgroups containing more responders, especially C1, showed longer OS and PFS than the non-responder subgroups, namely C4 and C5 (Fig. 9J). It should be noted that the C5 subgroup of leukemia patients (Loughran2015 and Ioannou2020) had the highest percentage of responders. The C2 subgroup of GBM patients (Urup2017) was associated with higher response rates. Altogether, ML-CS may serve as a promising tool for predicting response and prognosis of patients receiving immunotherapy. However, given the known ethnic disparities in cancer genomics and immunotherapy response, ML-CS trained on TCGA cohorts (most samples from North America or Europe) still needs further validation in more diverse cohorts to address potential bias.

Identification of potential therapeutic agents and targets for the CS subgroups

The expression profiles and drug sensitivity data of CCLs from the CTRP and PRISM datasets were used to build prediction model of drug response. Totally 162 duplicate compounds were excluded, and 1767 compounds were used for subsequent analysis (Fig. 10A). According to the drug sensitivity data from CTRP and PRISM, we utilized two methods to identify candidate agents with higher drug sensitivity in each CS subgroup (Fig. 10B,C). Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to identify the compounds with negative correlation coefficients. Differential drug response analysis was performed to determine the compounds with lower AUC values. These analyses identified 21 CTRP-derived compounds (e.g., canertinib, paclitaxel, navitoclax, daporinad, ouabain) and 25 PRISM-derived compounds (e.g., filanesib, cabazitaxel, idasanutlin, mevastatin, romidepsin), which shown significant negative correlations and lower AUC values in specific CS subgroups (Fig. 10D,E). Afterwards, we performed correlation analysis between CERES scores and CS-related cancer driver gene scores to identify potential CS-dependent therapeutic targets. The five most significant genes were identified in each CS subgroup (Fig. 10F). Notably, the CERES scores of genes were greater than zero in most CCLs (e.g., ALB in C1, CDKN1A in C3), indicating that these genes might not be essential. The remaining genes in C1 (DNM1, HSD11B2, MMP11, and RXRA), C2 (DHPS, NDUFB6, PPM1D, SOD2, and YARS2), C3 (ATM and PKN2), C4 (CACNA1G, GLS2, PIK3R3, and PRKCZ), and C5 (ATM, PKN2, and PSMB7) were considered potential therapeutic targets, and inhibiting the function of these genes might obtain favorable therapeutic effects.

Identification of candidate therapeutic agents and targets among the CS subgroups. (A) Venn diagram showing the included compounds from the CTRP and PRISM datasets. (B) Strategy diagram for identifying candidate agents with higher drug sensitivity in each CS subgroup. (C) Single-cell clustering of pan-cancer data based on drug sensitivity from the CTRP and PRISM datasets. (D) Spearman’s correlation analysis of CTRP-derived and PRISM-derived compounds among the CS subgroups. (E) Differential drug response analysis of CTRP-derived and PRISM-derived compounds among the CS subgroups. Lower AUC values indicated greater drug sensitivity. (F) Volcano plots (left panel) and scatter plots (right panel) of Spearman’s correlation coefficients and significance between CS-related cancer driver gene scores and CERES scores of drug targets in the CS subgroups. Color dots indicated targets with significant negative correlations (P < 0.05).

Discussion

CS is one of the fundamental hallmarks of cancer and aging, and has become a promising therapeutic target for cancer and other age-associated diseases3,10. Therefore, investigating the CS landscape in the tumor microenvironment of the same or different cancer types is crucial to optimize therapeutic strategies7. However, the comprehensive characterization of CS heterogeneity across cancer types has not been clarified. To address this, we extensively evaluated the molecular features of 33 cancer types and 29 normal tissues, and identified five CS subgroups characterized by a dominance of inflammatory response, DNA damage repair, autophagy, immune depletion or metabolic activity. The CS-derived classification scheme showed the potential for predicting prognosis, displaying microbial distribution, characterizing immune microenvironment, revealing multi-omic features, distinguishing single-cell CS heterogeneity, predicting immunotherapy response, and identifying therapeutic agents and targets. Therefore, our study indicated that the CS subgroups had implications for understanding the CS states of the tumor microenvironment, and may play a critical role in predicting treatment outcomes.

According to diverse molecular triggers, several phenotypes of CS have been identified at the cellular level, such as telomere shortening, oncogene activation, genotoxic and oxidative stress induced senescence71. Our study utilized unsupervised analysis to identify five CS subgroups with distinct gene expression patterns, representing a CS-derived classification scheme at the pan-cancer level. These five CS subgroups were stable and reproducible across multiple cancer types, indicating the intrinsic connection between the biological processes described by CS-related genes in cancers. Compared with defining CS scores to measure senescence levels20,21,22, the CS subgroups can better decipher the heterogeneous CS patterns and associated molecular features in the tumor microenvironment, and provide inspiration for investigating the potential genomic, transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms mediating CS process. Additionally, the distribution of the CS subgroups revealed preference for different types of cancer and tissue. Through single-cell assessment, we further observed that the CS subgroups have cancer-type specific distribution in cancer cells. These findings may help explain the CS heterogeneity among cancer types.

The present CS subgroups reflected or extended multiple senescence features identified in previous studies72. Inflamm-aging refers to a sterile chronic low-grade inflammatory state that arises from the combined effects of molecular, cellular, and organismal deficiencies during aging73. Factors secreted by senescent cells, known as the SASP, promote inflamm-aging74. The C1 subgroup was enriched with SASP-related inflammatory signatures (e.g., IL-6, IFN-γ, TNF-α), exhibiting an inflamed immunophenotype with abundant immune cell infiltration and higher immunomodulatory gene expression75. By comparison, the C4 subgroup with reduced inflammatory response and lymphocyte infiltration reflected an immunosuppressive phenotype76. The substantial accumulation of DNA damage is another distinguishing feature of CS, mainly activating the DNA damage response in the form of double-strand DNA breaks77. The C2 subgroup showed intermediate inflammatory response second to C1, consistent with the statement that DNA damage response is an essential driver for SASP and inflammation through the cGAS-STING pathway78. In addition, the C3 subgroup characterized by autophagic signatures conferred a favorable prognosis. Previous studies also found that the stimulation of autophagy extended lifespan and decreased tumorigenesis in mice79,80. The C5 subgroup was metabolically active and had a high degree of lymphocytic infiltration. The possible explanation for this result was that hematological and lymphatic cancers were rich in C5. Overall, the molecular subgroups of CS that highlighted different senescence features represented distinct immune patterns and had associations with patient prognosis.

The multi-omic alterations in the CS subgroups were evaluated in this study. Somatic mutations, cancer driver gene mutations, and copy number variations were more frequent in C1 and C2, indicating the potential impact of genomic instability on the CS landscape through generating neoantigens. Moreover, we identified significant cancer driver genes associated with each CS subgroup, some of which have been reported to be involved in aging and cancer progression. For example, BCL2 protein over-expresses in senescent cells and promotes cell resistance to apoptotic stimuli, while BCL2 inhibitor can eliminate senescent cells and inhibit cancer development81. Through protein structure-based analysis, we discovered the differences in driver mutation domains and structural stability between C1 and C2, which may contribute to revealing the mechanisms of mutations altering the protein function. Importantly, CS-related cancer driver genes had clinical implications for survival outcome and immunotherapy response. The CS-derived machine-learning model had good prediction performance compared with traditional immune checkpoints (e.g., PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4). Compared with the C4 subgroup, the C1 subgroup had a higher percentage of responders to immunotherapy and exhibited superior OS and PFS. The findings confirmed previous studies suggesting that immunotherapy response was associated with high tumor mutation burden, high neoantigen load, and increased T cell infiltration82,83,84. Therefore, the CS subgroups and related cancer driver genes may have good application prospects in efficacy prediction and strategy optimization of immunotherapy.

Apart from providing above information, the CS subgroups can also be used to guide targeted therapy for precise oncology. Potential therapeutic targets (e.g., MMP11 for C1, SOD2 for C2, ATM for C3 and C5) were identified for the CS subgroups. As an important member of the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family, MMP11 is highly expressed in various cancers such as NSCLC, BRCA, PAAD, and ESCA85. It has been reported that MMP11 promotes the tumorigenesis, proliferation and malignant development of cancer cells86. SOD2 encodes the manganese superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), which is involved in cancer cell proliferation and invasion by activating the signaling pathways regulating angiogenesis87. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase aberrations are the most common DNA damage and repair defects across cancer types. The synthetic lethal target corresponding to ATM is ataxia telangiectasia and RAD3-related (ATR) enzyme, and several ATR inhibitors have entered clinical trials and achieved considerable initial therapeutic effects88. Candidate agents were also recognized for each CS subgroup, such as canertinib (pan-ERBB inhibitor) for C1, paclitaxel (microtubule stabilizer) for C2, and navitoclax (BCL-2 inhibitor) for C3. Our study provided new insights into targeted therapy for the CS subgroup, however, their correlation with patient survival requires further clinical validation in independent cohorts.

However, several limitations should be noted in this study. Firstly, our analyses were limited by restriction to genetic data from published studies. The sample size of the C5 subgroup was relatively limited, predominantly comprising hematological malignancies, which may impact the generalizability of the conclusions. The characteristics of C5 subgroup may stem from the microenvironment specific to hematological malignancies, which may not be applicable for solid tumors. Functional validation is required in future research to verify CS subgroup signatures and strengthen mechanistic claims. In addition, there are inherent potential biases in retrospective analyses, such as selection bias in sample inclusion. The results should be verified by multiple prospective trials to reduce potential biases, and extended accordingly when other omic data are available. Moreover, we applied and compared several common algorithms when establishing prediction models. More novel and effective methods deserve further exploration to promote the novelty and advancement of the research framework. Although our model showed potential practicability and generalizability in present datasets, it still requires testing and improvement in large-scale cohorts. In practical application, potential confounders that affect immunotherapy response (e.g., TMB, PD-L1 expression) should be addressed to enhance the performance of ML-CS. Lastly, functional experiments are needed to strengthen the mechanistic insights and clinical relevance of the identified therapeutic targets.

In conclusion, this study delineated the pan-cancer CS landscape and identified five well-characterized CS subgroups to expand the existing understanding of CS heterogeneity. The CS subgroups showed cancer-type and tissue-type specific distribution, and revealed significant associations with patient prognosis, intratumoral microbiota, immunophenotypic features, and multi-omic alterations. Single-cell assessment of the CS subgroups confirmed the CS heterogeneity among cancer types at the single-cell level. In addition, we developed a machine-learning model that integrated CS-related cancer driver genes, which may become a beneficial tool for predicting immunotherapy response and prognosis. Furthermore, potential therapeutic agents and targets related to the CS subgroups may have implications for improving treatment efficacy. Altogether, the CS subgroups provide important insights into the CS heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment and may promote the optimization of personalized therapeutic strategies.

Data availability

The publicly available datasets used in this study included GSE117570, GSE189357, GSE143423, GSE146771, GSE118828, GSE102130, GSE131928, GSE141445, GSE72056, GSE123813, GSE103668, GSE126045, GSE135222, GSE179351, GSE53127, GSE60331, GSE79671, GSE148476, GSE42664, GSE165252, GSE79691, PRJEB2370, GSE78220, GSE91061, GSE35640, GSE165278, IMvigor210, GSE176307, and PMID32472114. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74 (1), 12–49 (2024).

Fane, M. & Weeraratna, A. T. How the ageing microenvironment influences tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 20 (2), 89–106 (2020).

López-Otín, C., Pietrocola, F., Roiz-Valle, D., Galluzzi, L. & Kroemer, G. Meta-hallmarks of aging and cancer. Cell. Metab. 35 (1), 12–35 (2023).

Yasuda, T., Baba, H. & Ishimoto, T. Cellular senescence in the tumor microenvironment and context-specific cancer treatment strategies. FEBS J. 290 (5), 1290–1302 (2023).

Zarneshan, S. N., Fakhri, S., Bachtel, G. & Bishayee, A. Exploiting pivotal mechanisms behind the senescence-like cell cycle arrest in cancer. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 135, 1–19 (2023).

Di Micco, R., Krizhanovsky, V., Baker, D. & d’Adda Di Fagagna, F. Cellular senescence in ageing: From mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 (2), 75–95 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. The impact of the senescent microenvironment on tumorigenesis: Insights for cancer therapy. Aging Cell. 23 (5), e14182 (2024).

Demaria, M. et al. Cellular senescence promotes adverse effects of chemotherapy and cancer relapse. Cancer Discov. 7 (2), 165–176 (2017).

Lau, L., Porciuncula, A., Yu, A., Iwakura, Y. & David, G. Uncoupling the Senescence-Associated secretory phenotype from cell cycle exit via Interleukin-1 inactivation unveils its protumorigenic role. Mol. Cell. Biol. 39 (12), e00586–e00518 (2019).

Zhang, L., Pitcher, L. E., Prahalad, V., Niedernhofer, L. J. & Robbins, P. D. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: Senolytics and senomorphics. FEBS J. 290 (5), 1362–1383 (2023).

Marin, I. et al. Cellular senescence is Immunogenic and promotes antitumor immunity. Cancer Discov. 13 (2), 410–431 (2023).

Kirschner, K., Rattanavirotkul, N., Quince, M. F. & Chandra, T. Functional heterogeneity in senescence. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 48 (3), 765–773 (2020).

Herranz, N. & Gil, J. Mechanisms and functions of cellular senescence. J. Clin. Invest. 128 (4), 1238–1246 (2018).

Hernandez-Segura, A. et al. Unmasking transcriptional heterogeneity in senescent cells. Curr. Biol. 27 (17), 2652–2660e4 (2017).

Junaid, M., Lee, A., Kim, J., Park, T. J. & Lim, S. B. Transcriptional heterogeneity of cellular senescence in cancer. Mol. Cells. 45 (9), 610–619 (2022).

Ou, H. L. et al. Cellular senescence in cancer: From mechanisms to detection. Mol. Oncol. 15 (10), 2634–2671 (2021).

Avelar, R. A. et al. A multidimensional systems biology analysis of cellular senescence in aging and disease. Genome Biol. 21 (1), 91 (2020).

Tao, W., Yu, Z. & Han, J. J. Single-cell senescence identification reveals senescence heterogeneity, trajectory, and modulators. Cell. Metab. 36 (5), 1126–1143e5 (2024).

Casella, G. et al. Transcriptome signature of cellular senescence. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 (14), 7294–7305 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Comprehensive assessment of cellular senescence in the tumor microenvironment. Brief. Bioinform. 23 (3), bbac118 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Comprehensive pan-cancer analysis identifies cellular senescence as a new therapeutic target for cancer: Multi-omics analysis and single-cell sequencing validation. Am. J. Cancer Res. 12 (9), 4103–4119 (2022).

Xu, Q. & Feng, X. Exploring the role of cellular senescence in cancer prognosis across multiple tumor types. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15, 1378356 (2024).

Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P. & Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 34 (5), 525–527 (2016).

Song, Q. et al. Dissecting intratumoral myeloid cell plasticity by single cell RNA-seq. Cancer Med. 8 (6), 3072–3085 (2019).

Zhu, J. et al. Delineating the dynamic evolution from preneoplasia to invasive lung adenocarcinoma by integrating single-cell RNA sequencing and Spatial transcriptomics. Exp. Mol. Med. 54 (11), 2060–2076 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Single-Cell analyses inform mechanisms of Myeloid-Targeted therapies in colon cancer. Cell 181 (2), 442–459e29 (2020).

Shih, A. J. et al. Identification of grade and origin specific cell populations in serous epithelial ovarian cancer by single cell RNA-seq. PLoS One. 13 (11), e0206785 (2018).

Filbin, M. G. et al. Developmental and oncogenic programs in H3K27M gliomas dissected by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 360 (6386), 331–335 (2018).

Neftel, C. et al. An integrative model of cellular States, Plasticity, and genetics for glioblastoma. Cell 178 (4), 835–849e21 (2019).

Chen, S. et al. Single-cell analysis reveals transcriptomic remodellings in distinct cell types that contribute to human prostate cancer progression. Nat. Cell. Biol. 23 (1), 87–98 (2021).

Tirosh, I. et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 352 (6282), 189–196 (2016).

Yost, K. E. et al. Clonal replacement of tumor-specific T cells following PD-1 Blockade. Nat. Med. 25 (8), 1251–1259 (2019).

Birkbak, N. J. et al. Overexpression of BLM promotes DNA damage and increased sensitivity to platinum salts in triple-negative breast and serous ovarian cancers. Ann. Oncol. 29 (4), 903–909 (2018).

Cho, J. W. et al. Genome-wide identification of differentially methylated promoters and enhancers associated with response to anti-PD-1 therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 52 (9), 1550–1563 (2020).

Kim, J. Y., Choi, J. K. & Jung, H. Genome-wide methylation patterns predict clinical benefit of immunotherapy in lung cancer. Clin. Epigenetics. 12 (1), 119 (2020).

Parikh, A. R. et al. Radiation therapy enhances immunotherapy response in microsatellite stable colorectal and pancreatic adenocarcinoma in a phase II trial. Nat. Cancer. 2 (11), 1124–1135 (2021).

Pentheroudakis, G. et al. A study of gene expression markers for predictive significance for bevacizumab benefit in patients with metastatic colon cancer: A translational research study of the Hellenic cooperative oncology group (HeCOG). BMC Cancer. 14, 111 (2014).

Verstraete, M. et al. Combining bevacizumab and chemoradiation in rectal cancer. Translational results of the axebeam trial. Br. J. Cancer. 112 (8), 1314–1325 (2015).

Urup, T. et al. Transcriptional changes induced by bevacizumab combination therapy in responding and non-responding recurrent glioblastoma patients. BMC Cancer. 17 (1), 278 (2017).

Loughran, T. P. Jr et al. Immunosuppressive therapy of LGL leukemia: Prospective multicenter phase II study by the Eastern cooperative oncology group (E5998). Leukemia 29 (4), 886–894 (2015).

van den Ende, T. et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy combined with Atezolizumab for resectable esophageal adenocarcinoma: A Single-arm phase II feasibility trial (PERFECT). Clin. Cancer Res. 27 (12), 3351–3359 (2021).

Ascierto, M. L. et al. Transcriptional mechanisms of resistance to Anti-PD-1 therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 23 (12), 3168–3180 (2017).

Gide, T. N. et al. Distinct immune cell populations define response to Anti-PD-1 monotherapy and Anti-PD-1/Anti-CTLA-4 combined therapy. Cancer Cell. 35 (2), 238–255e6 (2019).

Hugo, W. et al. Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to Anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell 165 (1), 35–44 (2016).

Riaz, N. et al. Tumor and microenvironment evolution during immunotherapy with nivolumab. Cell 171 (4), 934–949e16 (2017).

Ulloa-Montoya, F. et al. Predictive gene signature in MAGE-A3 antigen-specific cancer immunotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 31 (19), 2388–2395 (2013).

Zappasodi, R. et al. CTLA-4 Blockade drives loss of Treg stability in glycolysis-low tumours. Nature 591 (7851), 652–658 (2021).

Mariathasan, S. et al. TGFβ attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 Blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature 554 (7693), 544–548 (2018).

Rose, T. L. et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 alterations and response to immune checkpoint Inhibition in metastatic urothelial cancer: A real world experience. Br. J. Cancer. 125 (9), 1251–1260 (2021).

Braun, D. A. et al. Interplay of somatic alterations and immune infiltration modulates response to PD-1 Blockade in advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Med. 26 (6), 909–918 (2020).

Wilkerson, M. D. & Hayes, D. N. ConsensusClusterPlus: A class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics 26 (12), 1572–1573 (2010).

Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 14, 7 (2013).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612 (2013).

Charoentong, P. et al. Pan-cancer Immunogenomic analyses reveal genotype-immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint Blockade. Cell. Rep. 18 (1), 248–262 (2017).

Becht, E. et al. Estimating the population abundance of tissue-infiltrating immune and stromal cell populations using gene expression. Genome Biol. 17 (1), 218 (2016).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods. 12 (5), 453–457 (2015).

Chakravarthy, A. et al. Pan-cancer deconvolution of tumour composition using DNA methylation. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 3220 (2018).

Thorsson, V. et al. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity 48 (4), 812–830e14 (2018).

Martínez-Jiménez, F. et al. A compendium of mutational cancer driver genes. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 20 (10), 555–572 (2020).

Berman, H. M. et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 235–242 (2000).

Van Durme, J. et al. A graphical interface for the FoldX forcefield. Bioinformatics 27 (12), 1711–1712 (2011).

Gao, R. et al. Delineating copy number and clonal substructure in human tumors from single-cell transcriptomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 39 (5), 599–608 (2021).

Aibar, S. et al. SCENIC: Single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering. Nat. Methods. 14 (11), 1083–1086 (2017).

Leung, F. F., Lam, H. K., Ling, S. H. & Tam, P. S. Tuning of the structure and parameters of a neural network using an improved genetic algorithm. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 14 (1), 79–88 (2003).

Ghandi, M. et al. Next-generation characterization of the cancer cell line encyclopedia. Nature 569 (7757), 503–508 (2019).

Yang, C. et al. Prognosis and personalized treatment prediction in TP53-mutant hepatocellular carcinoma: An in Silico strategy towards precision oncology. Brief. Bioinform. 22 (3), bbaa164 (2021).

Galeano Niño, J. L. et al. Effect of the intratumoral microbiota on Spatial and cellular heterogeneity in cancer. Nature 611 (7937), 810–817 (2022).

Rooney, M. S., Shukla, S. A., Wu, C. J., Getz, G. & Hacohen, N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell 160 (1–2), 48–61 (2015).

Sun, D. et al. Classification of tumor immune microenvironment according to programmed Death-Ligand 1 expression and immune infiltration predicts response to immunotherapy plus chemotherapy in advanced patients with NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 18 (7), 869–881 (2023).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500 (7463), 415–421 (2013).

Muñoz-Espín, D. & Serrano, M. Cellular senescence: From physiology to pathology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 (7), 482–496 (2014).

Hernandez-Segura, A., Nehme, J. & Demaria, M. Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends Cell. Biol. 28 (6), 436–453 (2018).

Franceschi, C. & Campisi, J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 69 (Suppl 1), S4–S9 (2014).

Li, X. et al. Inflammation and aging: Signaling pathways and intervention therapies. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 8 (1), 239 (2023).

Hegde, P. S., Karanikas, V. & Evers, S. The Where, the When, and the how of immune monitoring for cancer immunotherapies in the era of checkpoint Inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 22 (8), 1865–1874 (2016).

Nduom, E. K., Weller, M. & Heimberger, A. B. Immunosuppressive mechanisms in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 17 (Suppl 7), vii9–vii14 (2015).

Ovadya, Y. et al. Impaired immune surveillance accelerates accumulation of senescent cells and aging. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 5435 (2018).

Dou, Z. et al. Cytoplasmic chromatin triggers inflammation in senescence and cancer. Nature 550 (7676), 402–406 (2017).

Pyo, J. O. et al. Overexpression of Atg5 in mice activates autophagy and extends lifespan. Nat. Commun. 4, 2300 (2013).

Fernández, Á. F. et al. Disruption of the Beclin 1-BCL2 autophagy regulatory complex promotes longevity in mice. Nature 558 (7708), 136–140 (2018).

Basu, A. The interplay between apoptosis and cellular senescence: Bcl-2 family proteins as targets for cancer therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 230, 107943 (2022).