Abstract

The development of efficient microcrystalline silicon (µc-Si) thin-film solar cells offers a promising route to reduce photovoltaic costs. This work presents, for the first time, a comprehensive numerical model to optimize ZnMgO/µc-Si-based solar cells by analyzing its performance metrics. The model incorporates horizontal and vertical grain boundaries (GBs) in the absorber with Gaussian-distributed donor- and acceptor-like trap states. Key parameters studied are Mg concentration, thickness, and doping in the ZnMgO emitter, as well as GB-induced recombination in the µc-Si absorber. Results show that increasing Mg concentration up to 20% significantly enhances performance, while higher concentrations yield negligible improvement. GB recombination critically affects performance: smaller grain size, which increases GB density, causes exponential degradation, and GB trap densities above 1011 cm− 2 lead to a sharp decline in metrics. The ZnMgO emitter exhibits optimal performance at ~ 100 nm thickness and ~ 5 × 1016 cm− 3 doping. A maximum efficiency of ~ 14.3% is achieved with 20% Mg, 100 nm thickness, 5 × 1016 cm− 3 doping in ZnMgO, and an absorber containing 10 GBs with trap density of 1011 cm− 2. The model is validated against previously reported results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thin-film technology offers the potential to lightweight, cost-effective silicon solar cells on flexible substrates1,2. Beyond lowering material usage and fabrication costs, zinc oxide (ZnO)-based thin-film heterojunction solar cells offer additional advantages such as improved optical transparency, tunable band alignment, and enhanced carrier collection due to the wide-bandgap ZnO window layer3. Their compatibility with low-temperature deposition techniques makes them suitable for flexible substrates and large-area fabrication3. These features position ZnO-based thin-film heterojunctions as a promising pathway toward high-efficiency, lightweight, and scalable photovoltaic technologies. Significant research has been conducted on silicon-based thin-film solar cells4,5,6,7. However, their limited efficiency highlights the need for further advancements. One of the techniques to improve the efficiency of solar cells is light management, such as surface texturing5,8,9,10. However, texturing in thin-film silicon solar cells is challenging due to their extremely thin structure. This problem can be mitigated by using transparent conducting oxide (TCO) as the emitter layer in the solar cell. Indium tin oxide (ITO) is sometimes used as a TCO layer11. However, the scarcity of indium makes it a costly material. Heterojunction solar cells with a wide-bandgap emitter layer, such as the zinc oxide (ZnO), on a crystalline silicon (c-Si) absorber, have gained significant attention from researchers due to the numerous advantages they offer. The deposition of ZnO thin-film is cost-effective, and it possesses excellent electrical and optical properties, while being a non-toxic material12.

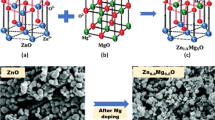

Several research works on ZnO/c-Si heterojunction solar cells have already been published in the literature13,14,15,16,17. However, all these studies were conducted on conventional bulk silicon wafers and thus do not address the unique characteristics of thin-film technologies. In contrast, there are very few studies on thin-film solar cells with ZnO as the emitter layer18,19. For example, Pietruszka et al.18 fabricated ZnO/c-Si thin-film solar cells using a 50 μm thick silicon absorber and achieved a maximum efficiency of 9.1%. However, a solar cell with 50 μm thick absorber layer cannot be classified as thin-film device and, thus, lacks the advantages of lightweight design, flexibility, and reduced material costs. Moreover, the growth of c-Si is quite complex and expensive, which increases the overall cost of ZnO/c-Si solar cells. On the other hand, high-quality microcrystalline silicon (µc-Si) films can be deposited at low temperatures using PECVD technique20,21. Furthermore, Knusten et al.19 conducted band-offset engineering on magnesium-doped zinc oxide (ZnMgO)-based silicon solar cells to predict higher efficiency by varying the Mg concentration. However, the study again focusses on bulk nature of the device. Therefore, the development of ZnMgO/µc-Si thin-film solar cell becomes important and has the potential to revolutionize the photovoltaic market.

In this work, a two-dimensional device simulation model has been developed, for the first time to the best of the author’s knowledge, to investigate the performance of ZnMgO/µc-Si thin-film solar cells, considering ZnMgO as the emitter and µc-Si as the absorber layer. The model accounts for grain boundary (GB) recombination by incorporating multiple horizontal- and vertical-like GBs in the absorber layer and multiple vertical-like GBs in the emitter layer. The performance of the solar cell has been analyzed in terms of short-circuit current density (JSC), open-circuit voltage (VOC), fill factor (FF), and efficiency, by varying key parameters, including magnesium (Mg) concentration, doping level, and thickness of the ZnMgO layer, as well as the number of grains and grain boundary (GB) trap density in the absorber layer. An optimized design of the device is proposed by tuning above mentioned parameters of both the emitter and absorber layers. The developed model has been validated against the published results from the literature ensuring accuracy and reliability. This work makes the following key contributions:

First comprehensive 2D model: Developed, for the first time, a numerical device model of ZnMgO/µc-Si thin-film solar cells considering both horizontal and vertical grain boundaries (GBs) with Gaussian-distributed donor- and acceptor-like traps.

-

Emitter optimization: Demonstrated that a ZnMgO emitter with ~ 20% Mg concentration, ~ 100 nm thickness, and ~ 5 × 1016 cm-3 doping level provides optimal device performance.

-

Grain boundary impact: Established that increasing GB density (smaller grain size) exponentially deteriorates device performance, while GB trap densities above 1011 cm-2 cause a sharp decline in the efficiency.

-

Performance enhancement: Showed that Mg incorporation in ZnMgO up to 20% significantly improves the device performance.

-

Validated model: Verified the developed model by benchmarking results against reported data in the literature, ensuring accuracy and reliability.

-

High efficiency achieved: Proposed an optimized structure delivering a maximum efficiency of ~ 14.3% with realistic device parameters.

Structural design and meshing

Figure 1 displays two-dimensional structure of ZnMgO/µc-Si thin-film solar cell studied in this work. The heterojunction consists of n-type ZnMgO acting as emitter layer and a p-type microcrystalline silicon (p-µc-Si) serving as an absorber layer. The ZnMgO layer thickness is optimized to one-quarter of the optical wavelength at 700 nm, allowing it to act as both an anti-reflective coating and the emitter layer. Aluminum is utilized for the selective-area front contact and the full-area rear contact. The wavelength-dependent refractive indices for ZnMgO and µc-Si are obtained from existing literature22,23. The device is assumed to be illuminated from the top surface. Width of the device is considered as 1 μm throughout the analysis. In Fig. 1, the X-axis and Z-axis represent the device width and thickness, respectively. In this study, two-dimensional simulations were performed using Silvaco TCAD software.

Simulation models and material parameters

Device models are crucial for ensuring that simulation studies closely reflect experimental investigations. Consequently, selecting accurate models is vital. To effectively evaluate device performance, the following models have been incorporated into this simulation.

Drift-diffusion model

The current densities in the continuity equations can be approximated using the drift-diffusion model by applying the Einstein relations24:

and,

where, \(\:{J}_{n}\left({J}_{p}\right)\) is current density of electrons (holes), µn (µp) is mobility of electrons (holes), \(\:{E}_{n}\:\left({E}_{p}\right)\) is effective electric field due to electrons (holes), \(\:{D}_{n}[=(kT/q\left){\mu\:}_{n}\right]\left({D}_{p}\right[=(kT/q\left){\mu\:}_{p}\right])\) is diffusion coefficient of electrons (holes), \(\:n\:\left(p\right)\) is non-equilibrium concentration of electrons (holes), and \(\:\nabla\:n\:\left(\nabla\:p\right)\) is concentration gradient of electrons (holes), respectively.

Field-dependent mobility models

Carrier mobilities vary with the electric field E and do not remain constant across its entire range. To account for this dependence, field-dependent mobility models have been employed in the simulations. The mobility of electrons and holes as functions of E are described by Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively24:

where, \(\:{\mu\:}_{n}\) (\(\:{\mu\:}_{p}\)) is mobility, \(\:E\) is the electric field, \(\:{V}_{satn}\) (\(\:{V}_{satp}\)) is saturation velocity, \(\:{\beta\:}_{n}\) (\(\:{\beta\:}_{p}\)) is constant of electrons (holes), respectively, and \(\:{\mu\:}_{n0}={\mu\:}_{n}{\left({T}_{L}/300\right)}^{-{T}_{{\mu\:}_{n}}}\), and \(\:{\mu\:}_{p0}={\mu\:}_{p}{\left({T}_{L}/300\right)}^{-{T}_{{\mu\:}_{p}}}\). Here, \(\:{T}_{{\mu\:}_{n}}\left({T}_{{\mu\:}_{p}}\right)\) is constant and equal to 1.5.

Carrier recombination model

Grain boundary (GB) recombination is a major factor limiting the efficiency of µc-Si-based thin-film solar cells. Thus, accurate modeling of this phenomenon is essential for understanding and enhancing device performance. Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) recombination is expected to dominate in µc-Si layer and at the ZnO/µc-Si interface of the device25. Therefore, SRH model is used to investigate GB and interface recombination in this study. The SRH model for GB recombination in µc-Si layer can be expressed as25:

where, \(\:{R}_{GB}\) is GB recombination rate, ni (Ei) is intrinsic carrier concentration (intrinsic energy level), \(\:{E}_{T}\), \(\:k\), and TL are trap energy level, Boltzmann constant, and lattice temperature, respectively, \(\:n\) (\(\:p\)) is non-equilibrium concentration of electrons (holes), and \(\:{\tau\:}_{n}^{eff}\) (\(\:{\tau\:}_{p}^{eff}\)) is the effective carrier lifetime of electrons (holes), which can be expressed mathematically as25:

where, \(\:{\tau\:}_{n}^{eff}\left({\tau\:}_{p}^{eff}\right)\) is effect lifetime of electrons (holes), \(\:{\tau\:}_{n}\left({\tau\:}_{p}\right)\) and \(\:{\tau\:}_{n}^{gb}\)(\(\:{\tau\:}_{p}^{gb}\)) are electrons (holes) lifetime at grain and GBs, respectively, in µc-Si layer of the device. Moreover, the structural characteristics of an interface and GB is same. Therefore, the model employed for GB can also be apply for interface recombination. Thus, GB recombination model discussed in Eqs. (5) and (6) have also been applied for interface recombination. It is worth noting that the GBs in non-crystalline silicon, µc-Si in particular, contain a high density of trap states distributed within the bandgap, with their positions being largely random. Consequently, their energy distribution within the bandgap is modelled using a Gaussian profile. Here, the peaks of the Gaussian-distributed trap densities are positioned at the mid-gap to account for maximum recombination.

Optical model

In the device under consideration, ZnO layer functions as the emitter, making its transmission and reflection properties critical. These properties primarily depend on the refractive index and thickness of the ZnO layer. Notably, the refractive index of ZnO closely matches the optimal value for antireflection coating when the underlying absorber layer is made of silicon26. The transfer matrix method (TMM) solver is utilized to calculate the beam propagation and transmission characteristics of the layer. The transmission coefficient of the ZnO layer is calculated to by the following relation26:

where, \({T_{ZnO}}\)is transmission coefficient of the ZnO layer, nAir, \({n_{Si}}\), and nAl are wavelength-dependent refractive indices of air, silicon, and aluminum, respectively, and \({H_{11}}{\text{,}}\,{\text{ }}{H_{12}},\,\,{H_{21}},\,\,{\text{and}}\,\,{H_{22}}\) are elements of the characteristic matrix \({M_T}\), related in terms of ZnO thickness, refractive index, and absorption coefficient26. Moreover, reflectance of ZnO layer in terms of its refractive index and thickness can be written as26:

where, \({R_{ZnO}}\)is reflectance of the ZnO layer, \({r_1}={{({n_{air}} - {n_{ZnO}})} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{({n_{air}} - {n_{ZnO}})} {({n_{air}}+{n_{ZnO}})}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {({n_{air}}+{n_{ZnO}})}}\), \({r_2}={{({n_{ZnO}} - {n_{Si}})} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{({n_{ZnO}} - {n_{Si}})} {({n_{ZnO}}+{n_{Si}})}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {({n_{ZnO}}+{n_{Si}})}}\), and \(\theta ={{(2\pi \times {n_{ZnO}} \times {t_{ZnO}})} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{(2\pi \times {n_{ZnO}} \times {t_{ZnO}})} \lambda }} \right. \kern-0pt} \lambda }\). Here, \({n_{ZnO}}\) (\({t_{ZnO}}\)) is refractive index (thickness) of the ZnO layer.

Material parameters are crucial for simulations, as they influence the performance of electronic and optoelectronic devices. Their accuracy is essential for reliable modeling and optimization. Therefore, some important parameters of ZnO and µc-Si used in the simulation are listed in Table 1. A flowchart illustrating the model development process is given in Fig. 2.

Model validation

Validating the developed device simulation model against available reported data is essential to ensure its consistency before analysis. To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first study on ZnMgO/µc-Si-based thin-film solar cells with ZnMgO used as the emitter layer and a thin film of µc-Si as absorber layer. Therefore, the developed model has been validated, as shown in Fig. 3a, against a related study reported in19, where the performance of a ZnMgO/c-Si bulk solar cell was analysed. It is worth mentioning that, for validating the developed model, we considered a solar cell with 0.175 μm thick ZnMgO (Mg = 20%) emitter and a 300 μm thick crystalline silicon (c-Si) absorber, as reported in19. This choice was made because, to the best of our knowledge, no prior study has investigated a solar cell configuration employing a ZnO emitter with a µc-Si absorber. Some key material parameters from19, such as bandgap, thickness, electron affinity, carrier lifetime, and carrier.

(a) Comparison of the device efficiencies obtained from the developed model with the reported results in19 for 0% and 20% Mg concentrations. It is important to note that ZnO/Si bulk solar cell, as reported in19 has been used for valildation of the developed model, as no ZnO/µc-Si thin film solar cell is reported so far to the best of our knowledge. The percentage error between the reported and simulated results are given in circular callouts (b) Variations of bandgap and electron affinity of ZnMgO layer for different values of Mg concentration as reported in19.

mobilities of each layer of the cell, along with the best-fit trap density at the ZnMgO/µc-Si interface used in the simulation, are listed in Table 2. It may be mention here that Mg concentration-dependent electron affinity and bandgap of ZnO, as reported in literature19 and shown in Fig. 3b, has been used in the simulation to investigate device performance. The percentage error between the simulated and reported values for 0% Mg concentration19, is indicated with circular callouts in Fig. 3a.

Result and discussion

This section analyzes the solar cell performance parameter such as short-circuit current density (JSC), open-circuit voltage (VOC), fill-factor (FF), and efficiency by varying the Mg content, thickness, and doping concentration of the ZnMgO layer, along with the absorber layer characteristics grain number and GB trap density. Figure 3b, taken from the literature19, shows the variations of bandgap and electron affinity of the ZnMgO layer as a function of Mg concentration. It should be mentioned here that the Mg concentration is limited to 28% because it becomes insoluble in ZnO when exceeded beyond this value19.

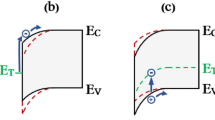

Effect of varying Mg concentration

From Fig. 3b, it is evident that changing Mg concentration changes electron affinity of the ZnMgO layer and thus the band offset at ZnMgO/µc-Si heterointerface. Therefore, the solar cell performance has been investigated by varying Mg concentration for different values of ZnMgO doping level. Figure 4a,b show the variations of JSC (VOC) and FF (Efficiency), respectively, in relation with Mg concentration for different values of ZnMgO doping concentration. It is found from Fig. 4a that JSC increases gradually as the Mg concentration rises from 0% to 20%, but saturates beyond this level. This behaviour is attributed to the significant reduction in the valence band notch at the ZnMgO/µc-Si interface within this range of Mg concentration, which facilitates enhanced hole transport across the junction. INSET-1 and INSET-2 of Fig. 5 illustrate the corresponding reduction in the valence band notch and enhanced net hole flow across the interface with increased Mg concentrations. It may be noted that INSET-2 of Fig. 5 shows only three Mg concentrations (0%, 8%, and 20%) for clarity, as including more would reduce the visual comprehensibility. The JSC saturates because the valence band notch at the interface found to be reducing insignificantly beyond 20% Mg concentration, as can be seen from INSET-1 of Fig. 5. Moreover, Fig. 4a shows that VOC is nearly independent of Mg concentration up to 20%. However, a slight decrease in VOC is observed when Mg concentration varied from 20% to 24% and it saturates beyond 24% Mg concentration. It can be observed from Fig. 4b that FF rapidly increases as the Mg concentration increases from 0% to 20%. This due to the fact that increasing Mg concentration reduces the notch, resulting in reduce in series resistance of the device. However, the FF remains nearly constant when Mg concentration increased beyond 20%, as there is no significant reduction in the notch when Mg concentration increased beyond 20%. Since the device efficiency is related to the product of JSC, VOC, and FF, it increases gradually with Mg concentration from 0% to 20%, but shows a slight decline for Mg concentration between 20% and 24% and becomes constant beyond 24% Mg concentration, as observed in Fig. 4b.

Effect of varying ZnMgO thickness

Optimization of ZnMgO, acting as emitter layer, is crucial for improved device performance. Therefore, this subsection discusses the effect of varying ZnMgO thickness on the performance metrics of the cell. Figure 6a,b show the variations of JSC (VOC) and FF (efficiency), respectively, as a function of ZnMgO thickness for Mg concentration of 20%. It has been found that JSC increases non-linearly as ZnMgO thickness increased from 20 to 100 nm, reaches its maximum value for ZnMgO thickness of 100 nm. This is because the best combination of absorbance and resistivity is found for ZnMgO thickness near about 100 nm27. Further increase in ZnMgO thickness from 100 to 160 nm leads to slowly decrease in JSC as the absorbance starts decreasing slowly. Increasing the ZnMgO thickness beyond 160 nm causes a sharp decrease in JSC, as the absorbance drops rapidly in this thickness range. However, VOC is found to be independent for entire range of ZnMgO thickness. This is because the ZnMgO layer does not significantly contribute to the junction formation where carrier recombination occurs. Such variation of VOC with the thickness of window layer has also been reported in33. Now, Fig. 6b shows that FF initially increases with the increase in ZnMgO thickness from 20 to 80 nm, remains constant between 80 nm and 180 nm, and decrease beyond 180 nm. The conversion efficiency is found to be following the nature of JSC variation.

Effect of varying ZnMgO doping concentration

This subsection discusses investigation of the device performance by varying ZnMgO doping concentration by considering other parameters constant. Figure 7a,b show the variation of device parameters as a function of ZnMgO doping concentration for 20% Mg concentration. It can be seen from Fig. 7a that JSC steeply increases when ZnMgO doping level is varied from 1016 to 5 × 1016 cm− 3.

This is because increasing doping level increases conductivity and thus reduces resistivity of the ZnMgO layer, resulting in enhanced carrier collection. However, the rate of increase become slow for the doping range between 5 × 1016 to 1017 cm− 3. Increasing the doping concentration further from 1017 to 5 × 1018 cm− 3 leads JSC to decrease slowly. This is because auger recombination, which is generally dominant at a high doping concentration starts neutralizing the effect of enhanced carrier collection due to increase in doping level. JSC is observed to be dropping rapidly for doping level greater than 5 × 1018 cm− 3, as auger recombination becomes dominant over the effect of enhanced carrier collection. On the other hand, VOC is found to be decreasing non-linearly as ZnMgO doping concentration increased from 1014 to 1019 cm− 3. This attributes to the fact that increasing ZnMgO doping increases its Fermi level closer to the conduction band, which reduce the effective built-in potential across the junction, leading to decrease in VOC. Furthermore, it is found from Fig. 7b that FF increasing rapidly when ZnMgO doping concentration is increased from 1016 to 5 × 1016 cm− 3. This is because of reduced series resistivity of the cell. Moreover, FF is found to be decreasing slowly for doping range from 5 × 1016 to 1018 cm− 3 but beyond 1018 cm− 3, the rate of decrease becomes steeper due to enhanced auger recombination. The figure also shows that efficiency rapidly increases for ZnMgO doping concentration from 1016 to 5 × 1016 cm− 3 and decreases slowly when the doping concentration is increased beyond the value of 5 × 1016 cm− 3. This behaviour attributes the combined effect of JSC, VOC, and FF.

Grain boundary effects

Since the absorber layer, which contains multiple grain boundaries (GBs), is the primary region for generating electron-hole pairs that contribute to the device current, it is essential to investigate the impact of GB recombination on the device performance. In this subsection, number of grains in the absorber layer has been varied to analyze the device performance. It has been found from experimental data that GB size of µc-Si ranges from 3 nm to 100 nm30. Therefore, by considering 1 μm width of the device, size of the grain along the X-axis would range approximately from 10 to 100. Figure 8a,b show the variations of JSC (VOC) and FF (efficiency) as a function of number of grains in the absorber layer for Mg concentration of 20% of the ZnMgO layer. It can be observed from Fig. 8a that JSC (VOC) exponentially decreases from 20.64 mA/cm2 (0.815 V) to 16.48 mA/cm2 (0.71 V) mA/cm2 when the number of grains in the absorber layer is varied from 10 to 100. Moreover, FF (efficiency) is found to be exponentially decreasing from 84.78% (14.3%) to 71.7% (8.4%) as number of grains in the absorber layer is varied from 10 to 100, as shown in Fig. 8b. Such decrement in JSC, VOC, FF, and efficiency with the increase in number of grains is because increasing the number of grains increases number of grain boundaries, consequently increase effective carrier recombination in the absorber layer leading poor device performance. Now, the solar cell performance has been investigated by varying GB trap density for 20% Mg concentration of ZnMgO layer, as shown in Fig. 9a,b. The variation of JSC (VOC), and FF (efficiency) as a function of GB trap density is shown in Fig. 9a, respectively. It is found from Fig. 9a,b that effect of GB trap density from 1010 cm −2 to 1011 cm-2 on JSC, VOC, FF, and efficiency has insignificant impact. This is because net carrier recombination is dominated by the bulk recombination in the absorber for this range of GB trap density. However, as the GB trap density increased beyond 1011 cm-2, JSC, VOC, FF, and efficiency are found to be decreasing sharply, as GB recombination becomes the dominant mechanism31,32,33,34. It may be noted that experimentally reported values of GB trap densities in silicon range from 1011 cm−2 to 1012 cm-235,36. Therefore, the range of GB trap densities considered in our study fully encompasses the experimentally reported values. The optimized parameters corresponding to the maximum device efficiency is summarized in Table 3.

Conclusion

This work presented, for the first time, a comprehensive two-dimensional numerical model for ZnMgO/µc-Si thin-film solar cells, incorporating the effects of Mg concentration, ZnMgO thickness and doping, as well as GB recombination in the µc-Si absorber. The study investigates device performance by varying the Mg concentration, thickness, and doping density of the ZnMgO emitter, along with the number of grains and GB trap density in the absorber layer. The results demonstrate that device performance improves significantly with Mg incorporation up to 20%, beyond which the effect saturates. Optimal emitter performance is achieved at a thickness of ~ 100 nm and a doping level of ~ 5 × 1016 cm-3. It was further shown that GB recombination critically limits efficiency, with device performance sharply deteriorating once GB trap density exceeds 1011 cm-2. The developed model predicts a maximum efficiency of ~ 14.3% for an optimized ZnMgO/µc-Si configuration and exhibits good agreement with reported experimental trends, underscoring its reliability. These findings highlight the potential of ZnMgO/µc-Si heterojunctions for low-cost, high-performance thin-film photovoltaics and emphasize the necessity of interface and GB passivation through some chemical and field passivation for further efficiency enhancement. It is important to note that fabricating ZnMgO/µc-Si thin-film solar cells involve key challenges, including precise control of ZnMgO composition for proper band alignment, uniform layer thickness to prevent local performance variations, and effective passivation of grain boundaries in the µc-Si absorber to reduce recombination. Addressing these factors makes the simulation model more realistic.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Meier, J. et al. From R&D to mass production of micromorph thin film silicon PV. Energy Procedia. 15, 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2012.02.021 (2012).

Sekimoto, T. et al. Progress of sanyo’s R&D on thin film silicon solar module. Proc. 26th Eur. Photovolt. Sol Energy Conf. 92, 001147–001150. https://doi.org/10.1109/pvsc.2010.5614744 (2010).

Mondal, P. Interface band alignment engineering of ZnO/Si heterojunction solar cells with high open circuit voltage. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 35 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-024-13191-2 (2024).

Boccard, M. et al. High-Stable-Efficiency tandem Thin-Film silicon solar cell with Low-Refractive-Index Silicon-Oxide interlayer. IEEE J. Photovolt. 4, 1368–1373. https://doi.org/10.1109/jphotov.2014.2357495 (2014).

Sai, H., Matsui, T., Matsubara, K., Kondo, M. & Yoshida, I. 11.0%-Efficient Thin-Film microcrystalline silicon solar cells with honeycomb textured substrates. IEEE J. Photovolt. 4, 1349–1353. https://doi.org/10.1109/jphotov.2014.2355037 (2014).

Rassekh, M., Shirmohammadi, R., Ghasempour, R., Astaraei, F. R. & Shayesteh, S. F. Effect of plasmonic aluminum nanoparticles shapes on optical absorption enhancement in silicon thin-film solar cells. Phys. Lett. A. 408, 127509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2021.127509 (2021).

Sai, H. et al. Effect of front TCO layer on properties of Substrate-Type Thin-Film microcrystalline silicon solar cells. IEEE J. Photovolt. 5, 1528–1533. https://doi.org/10.1109/jphotov.2015.2478030 (2015).

Abe, Y., Kagei, T., Sichanugrist, P. & Konagai, M. Development of Double-Textured ZNO:B substrates for improving microcrystalline silicon solar cell performance. IEEE J. Photovolt. 4, 1374–1379. https://doi.org/10.1109/jphotov.2014.2358085 (2014).

Feng, N. N. N. et al. Duan, N. X. Design of highly efficient Light-Trapping structures for Thin-Film crystalline silicon solar cells. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 54, 1926–1933. https://doi.org/10.1109/ted.2007.900976 (2007).

Meier, M. et al. Fabrication of Light-Scattering multiscale textures by Nanoimprinting for the application to Thin-Film silicon solar cells. IEEE J. Photovolt. 4, 772–777. https://doi.org/10.1109/jphotov.2014.2311233 (2014).

Kobayashi, H., Kogetsu, Y., Ishida, T. & Nakato, Y. Increases in photovoltage of indium Tin oxide/silicon oxide/mat-textured n-silicon junction solar cells by silicon preoxidation and annealing processes. J. Appl. Phys. 74, 4756–4761. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.354346 (1993).

Chen, L., Chen, X., Liu, Y., Zhao, Y. & Zhang, X. Research on ZnO/Si heterojunction solar cells. J. Semicond. 38, 054005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-4926/38/5/054005 (2017).

Pietruszka, R. et al. Improved efficiency of n-ZnO/p-Si based photovoltaic cells by band offset engineering. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 147, 164–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2015.12.018 (2015).

Chabane, L., Zebbar, N., Kechouane, M., Trari, M. & Aida & Al-doped and in-doped ZnO thin films in heterojunctions with silicon. Thin Solid Films. 605, 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2015.10.063 (2015).

Untila, G. G., Kost, T. N. & Chebotareva, A. B. Bifacial 8.3%/5.4% front/rear efficiency ZnO:Al/n-Si heterojunction solar cell produced by spray pyrolysis. Sol. Energy. 127, 184–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2016.01.028 (2016).

Soylu, M. & Savas, O. Electrical and optical properties of ZnO/Si heterojunctions as a function of the Mg Dopant content. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 29, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2013.09.008 (2013).

Chaabouni, F., Abaab, M. & Rezig, B. Characterization of n-ZnO/p-Si films grown by Magnetron sputtering. Superlattices Microstruct. 39, 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spmi.2005.08.070 (2005).

Pietruszka, R. et al. 9.1% efficient zinc oxide/silicon solar cells on a 50 µm Thick Si absorber. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 12, 766–774. https://doi.org/10.3762/bjnano.12.60 (2021).

Knutsen, K. E., Schifano, R., Marstein, E. S., Svensson, B. G. & Kuznetsov, A. Yu. Prediction of high efficiency ZnMgO/Si solar cells suppressing carrier recombination by conduction band engineering. Phys. Status Solidi (A). 210, 585–588. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssa.201228527 (2012).

Aissa, B., Abdallah, A. A. & Garcia, J. L. Low-temperature PECVD deposition of highly conductive n-type microcrystalline silicon thin films for optoelectronic applications. 2022 IEEE 49th Photovoltaics Specialists Conference (PVSC) 689, 0052–0057. https://doi.org/10.1109/pvsc48317.2022.9938628 (2022).

Nardes, A. M., Andrade, M. D., Fonseca, J., Dirani, A. T., Muccillo, N. S. & Muccillo & Low-temperature PECVD deposition of highly conductive microcrystalline silicon thin films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 14, 407–411. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1023917205077 (2003).

Zeman, M., Van Swaaij, R. C. M. M., Metselaar, J. W. & Schropp, R. E. I. Optical modeling of a-Si:H solar cells with rough interfaces: effect of back contact and interface roughness. J. Appl. Phys. 88, 6436–6443. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1324690 (2000).

Dewan, R., Jovanov, V., Hamraz, S. & Knipp, D. Analyzing periodic and random textured silicon thin film solar cells by rigorous coupled wave analysis. Sci. Rep. 4 https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06029 (2014).

Sze, S. M. & Ng, K. K. Physics of Semiconductor Devices, 3rd ed (Wiley, 2008).

Shockley, W. & Read, W. T. Statistics of the recombinations of holes and electrons. Phys. Rev. 87, 835–842. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrev.87.835 (1952).

Li, H. E. & Majewski, L. Vertical-Cavity Surface-Emitting Laser devices. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-05263-1 (2003).

Askari, S. S. A., Kumar, M. & Das, M. K. Numerical study on the interface properties of a ZnO/c-Si heterojunction solar cell. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 33, 115003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6641/aadf71 (2018).

Kiess, H., Augelli, V. & Murri, R. Carrier lifetime from transient photoconductivity measurements on microcrystalline silicon films. Thin Solid Films. 141, 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-6090(86)90347-0 (1986).

ReynoldsS. Carrier mobility, band Tails and defects in microcrystalline silicon. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 253, 012002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/253/1/012002 (2010).

Cerqueira, M. F., Ferreira, J. A., Andritschky, M. & Costa, M. F. M. Structural characterization of µc-Si:H films produced by R.F. Magnetron sputtering. Microelectron. Eng. 43–44, 627–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-9317(98)00236-6 (1998).

Imam, M., Ahmed, T. & Askari, S. S. A. Investigation of interface and grain boundary recombination in mc/pc-Si solar cells for flexible substrate. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 49, 995–1005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-023-07932-4 (2023).

Imam, M., Askari, S. S. A. & Das, M. K. Development of theoretical model for effective carrier lifetime in polycrystalline semiconductors. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 70, 5249–5256. https://doi.org/10.1109/ted.2023.3300654 (2023).

Manoua, M., Jannane, T., El-Hami, K. & Liba, A. Investigation of N-ZnO/P-GaAs heterojunction solar cell using two-dimensional numerical simulation. JOM 75, 3601–3611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-023-05963-8 (2023).

Imam, M., Askari, S. S. A. & Das, M. K. Effect of grain boundary orientation on the recombination in polycrystalline materials: a theoretical and simulation study. Appl. Phys. A 128 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-022-06027-5 (2022).

Dimitriadis, C. A. Grain boundary trap distribution in polycrystalline silicon thin-film transistors. J. Appl. Phys. 73, 4086–4088. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.352836 (1993).

Ikeda, H. Evaluation of grain boundary trap States in polycrystalline–silicon thin-film transistors by mobility and capacitance measurements. J. Appl. Phys. 91, 4637–4645. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1454202 (2002).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal University Jaipur.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Muzaffar Imam contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing of the original draft, and visualization. Md. Akram Ahmad was involved in methodology, formal analysis, and visualization. Paramjit Kaur contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, and visualization. Mukul Kumar Das provided software support, formal analysis, resources, supervision, and critical review and editing of the manuscript. Syed Sadique Anwer Askari contributed to formal analysis, validation, supervision, and review and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Imam, M., Ahmad, M.A., Kaur, P. et al. Investigation of ZnMgO/µc-Si thin-film solar cell using two-dimensional numerical simulation. Sci Rep 15, 39859 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23415-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23415-y