Abstract

Sarcopenia, characterized by the loss of muscle mass and strength, is a multifactorial disorder, including metabolic disturbance. Plasma amino acids (AAs) regulate muscle protein synthesis and breakdown. This study evaluated plasma AA metabolites as potential biomarkers for sarcopenia using metabolomic analysis. We assessed 31 AA metabo lites in an age-matched discovery cohort (72 men, 36 women with sarcopenia; 72 and 36 controls) and a validation cohort (36 men, 46 women with sarcopenia; 128 and 112 controls). In discovery cohort, isoleucine (Ile), leucine (Leu), valine (Val), methionine (Met), phenylalanine (Phe), tryptophan (Trp), alpha-aminoadipic acid (alpha-AAA), glutamate (Glu), and methionine sulfoxide (MetO) were lower in men with sarcopenia, while Glu was lower in women (p < 0.05). Leu in men and Glu in both sexes were associated with skeletal muscle index. A regression model combining Leu and Glu in men and Glu in women yielded an AA score. Adding the AA score to hand grip strength improved the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve in men (0.646 to 0.767, p = 0.003; 0.563 to 0.767, p = 0.002) and in women (0.486 to 0.728, p < 0.001; 0.576 to 0.680, p = 0.018). Leu in men and Glu in both sexes, reflecting low muscle mass, are potential circulating biomarkers for sarcopenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sarcopenia, characterized by age-related loss of muscle mass and strength, is associated with a higher risk of adverse outcomes such as falls, functional decline, frailty, and increased mortality1,2,3. Having emerged as a significant public health concern worldwide, this condition imposes a substantial economic burden on healthcare systems4. To date, no specific drugs have been approved for sarcopenia treatment, and the therapeutic effects of exercise and nutritional supplementation are often limited, particularly after disease progression3. Consequently, the early detection of sarcopenia is crucial to effectively manage the condition and mitigate its impacts.

Currently, sarcopenia is diagnosed based on various assessments of muscle mass, strength, and physical performance1,2,3. These assessments predominantly reflect the status of skeletal muscle as a static indicator, often detecting the condition at an advanced stage. However, muscle is a dynamic metabolic organ, and alterations in energy metabolism play a significant role in the early stages of sarcopenia5. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) is a widely used, standard platform for quantification of circulating metabolites. This approach offers a comprehensive view of the organism’s phenotype as shaped by genetic and environmental factors6. Thus, metabolites may potentially be used as early diagnostic biomarkers for sarcopenia. We also acknowledge evidence that blood lipid-related metabolites7 and metabolites observed in four distinct metabolic pathways (purine metabolism, parathyroid hormone synthesis, secretion, and action, choline metabolism in cancer, and tuberculosis) relate to sarcopenia8.

Aside from their known role in dietary protein intake, circulating amino acids (AAs) are essential players in the regulation of muscle protein synthesis and degradation9,10. Therefore, disarrangements of protein–AA metabolism may become clinically evident with manifestations such as sarcopenia11. Numerous studies have reported associations between circulating AAs and sarcopenia in older adults, supporting the potential biomarker value of these metabolites7,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. However, most prior studies were single-cohort and cross-sectional with modest sample sizes, did not assess diagnostic performance against handgrip strength (HGS) nor the incremental value of AAs beyond HGS, and rarely provide external validation or sex-stratified analyses. Herein, we aim to explore the potential of plasma AA metabolites as biomarkers for sarcopenia and to evaluate their diagnostic performance—including incremental value beyond HGS—in sex-stratified models across two independent cohorts (> 500 participants), with external validation, using LC–MS/MS–based targeted metabolomics.

Results

Characteristics of study participants in the discovery cohort

Table 1 presents the main characteristics of the participants in the discovery cohort (72 men and 36 women with sarcopenia and 72 and 36 age-matched controls). There were no significant differences in age between the case and control groups (p = 0.989 and p = 0.935 in men and women, respectively). The weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) of the sarcopenia group were significantly lower than those in the control group (all p < 0.001). Muscle mass parameters in both sexes including lean mass, appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM), and skeletal muscle mass index (SMI), and handgrip strength (HGS) in the men of the sarcopenia group, were significantly lower than those in the control group (all p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in the chair stand test scores, drinking and exercise habits, or prevalence of diabetes between the sarcopenia and control groups (all p > 0.05). Smoking status differed significantly between men with sarcopenia and controls (p = 0.002). The prevalence of hypertension was significantly lower in women with sarcopenia than in the control group (p = 0.034).

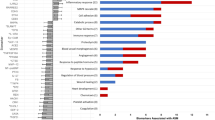

Association between AA metabolites in human plasma and sarcopenia in the discovery cohort

The plasma levels of all three branched-chain AAs (BCAAs; isoleucine [Ile], leucine [Leu], valine [Val]), three essential AAs (EAAs; methionine [Met], phenylalanine [Phe], tryptophan [Trp]), and three non-essential AAs (non-EAAs; α-aminoadipic acid [α-AAA], glutamate [Glu], and methionine sulfoxide [MetO]) were significantly lower in men with sarcopenia compared to controls (all p < 0.05; Table 2, Supplementary Table S1). In contrast, only Glu levels were significantly lower in women with sarcopenia compared to the controls (p = 0.042).

In men, Ile, Leu, Val, Met, Phe, Trp, α-AAA, Glu, and MetO were significantly associated with SMI (all p < 0.05; Table 3), and Ile, Leu, Val, and Trp were significantly associated with HGS (all p < 0.05). Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that the first two principal components accounted for a substantial amount of the variance, with key contributions from Leu, Phe, Trp, α-AAA, and Glu for SMI (Supplementary Fig. S1). For HGS, the PCA showed strong contributions from Leu and Trp (Supplementary Fig. S1). In women, Glu was significantly associated with SMI (p = 0.003).

In men, univariate analysis showed that Leu, Phe, Trp, α-AAA, and Glu levels were significantly associated with SMI (all p < 0.05; Table 4), and Leu and Trp levels were significantly associated with HGS (all p < 0.05; Table 4). Multivariate analysis revealed that Leu and Glu levels had significant independent associations with SMI, and Leu levels had significant associations with HGS. For the association of Leu with SMI in men, allowing non-linearity yielded only modest improvement over a linear model (natural splines vs. linear: p = 0.038 [degrees of freedom, df = 3]/0.035 [df = 4]; Δ Akaike Information Criterion [ΔAIC] ≈ 2.7–2.9; generalized additive model [GAM] smooth effective degrees of freedom [edf] = 2.37, p = 6.86 × 10⁻⁶; linear vs. GAM likelihood-ratio test [LRT], p = 0.048), while the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) favored the linear specification and the substantive inference was unchanged. For Glu with SMI in men, non-linear terms did not improve fit (natural splines vs. linear: p = 0.466/0.612; GAM smooth edf ≈ 1 with unchanged AIC). For Glu with SMI in women, results were similar (natural splines vs. linear: p = 0.838/0.952; AIC/BIC higher for splines; GAM smooth edf ≈ 1), supporting a linear dose–response. We therefore retained linear terms for Leu in men and for Glu in both sexes.

In men, increasing Leu levels per standard deviation (SD) significantly decreased the odds of low muscle strength with odds ratios (ORs) of 0.50 (95% confidence interval [95% CIs]: 0.33−0.75) (Table 5). Because smoking status differed significantly between sarcopenic and control men, we performed sensitivity analyses adding smoking status and tested for interaction (Supplementary Table S2). After adjustment for smoking, the association of Leu with low muscle strength persisted (OR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.33–0.75). The interaction with smoking status was not significant (p = 0.339). The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUROC) of Leu for low muscle strength in men was 0.702 (95% CI: 0.604–0.799). Furthermore, increasing Leu and Glu levels significantly decreased the odds of low muscle mass with ORs of 0.42 (95% CI: 0.28−0.63) and 0.59 (95% CI: 0.41−0.85), respectively. After adjustment for smoking (Supplementary Table S2), the associations of both Leu (OR: 0.43, 95% CI: 0.28–0.65) and Glu (OR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.37–0.81) with low muscle mass remained. Interactions with smoking status were not significant (p = 0.693 for Leu, p = 0.104 for Glu). The AUROC of Leu and Glu for low muscle mass in men was 0.714 (95% CI: 0.628–0.799) and 0.641 (95% CI: 0.550‒0.732), respectively.

In women, increasing Glu levels significantly decreased the odds of low muscle mass with ORs of 0.45 (95% CI: 0.27−0.78). Because the prevalence of hypertension differed significantly between sarcopenic and control women, we performed sensitivity analyses adding hypertension status and tested for interaction (Supplementary Table S2). After adjustment for hypertension, the association of Glu with low muscle mass persisted (OR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.28–0.84). The interaction with hypertension status was not significant (p = 0.106). The AUROC of Glu for low muscle mass in women was 0.708 (95% CI: 0.587–0.830).

Association between AA metabolites in human plasma and sarcopenia in the validation cohort

The main characteristics of the 68 men and 158 women in the validation cohort from the Asan Medical Center (AMC) (21 men and 46 women with sarcopenia and 47 and 112 age-matched controls, respectively) are presented in Supplementary Table S3. Muscle mass parameters (lean mass, ASM, and SMI) and HGS of the sarcopenia group were significantly lower than those of the control group (all, p < 0.05).

The men with sarcopenia group had significantly lower Leu levels than the control group (p < 0.001). Glu was numerically lower in sarcopenia in both sexes; the difference reached statistical significance in women (p = 0.007) but not in men (p = 0.222).

The predictive ability of the AA score for sarcopenia in both the discovery and validation cohorts

As a diagnostic regression equation for sarcopenia based on multivariate linear regression analysis of Leu and Glu with SMI in the discovery cohort, the AA score of men was calculated as follows: AA score of men = 7.216 + (0.207*log (Glu)SD) + (0.307 (*log(Leu)SD). The corresponding ROC curve of the AA score of men had an AUROC of 0.726 (95% CI: 0.642–0.809) in the discovery cohort men (Fig. 1). The addition of the AA score to low muscle strength (HGS < 28 kg) in men as a predictor of sarcopenia improved the AUROC by 18.8%, from 0.646 (95% CI: 0.575–0.717; HGS only) to 0.767 (95% CI: 0.690–0.845, p = 0.003; HGS + AA score). In the validation cohort men, the AUROC of the AA score was 0.759 (95% CI: 0.631–0.887). Despite the lack of statistical significance in the AUROC for low muscle strength (0.563 [95% CI: 0.470–0.656]), the addition of the AA score (AUROC: 0.767, 95% CI: 0.639–0.895; HGS + AA score) substantially improved the AUROC by 36.2% (p = 0.027) in the validation cohort.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the amino acid (AA) score of men and women to detect sarcopenia in the discovery cohort (men = 144 and women = 72) and validation cohort (men = 68 and women = 158). AA score of men = 7.216 + (0.207*log (Glu)SD) + (0.307 (*log(Leu)SD). AA score of women = 6.119 + (0.324*log (Glu)SD). AUROC, area under the ROC curve; Glu, Glutamic Acid; HGS, hand grip strength; Leu, Leucine; SD, standard deviation; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

As a diagnostic regression equation for sarcopenia based on univariate linear regression analysis of Glu with SMI in the discovery cohort, the AA score of women was calculated as follows: AA score of women = 6.119 + (0.324*log (Glu)SD). The corresponding ROC curve of the AA score of women had an AUROC of 0.708 (95% CI: 0.587–0.830) in the discovery cohort women (Fig. 1). Despite the lack of statistical significance in the AUROC for low muscle strength (HGS < 18 kg) in women (0.486 [95% CI: 0.396–0.576]), the addition of the AA score (AUROC: 0.728, 95% CI: 0.609–0.847; HGS + AA score) substantially improved the AUROC by 49.7% (p < 0.001) in the discovery cohort. In the validation cohort women, the AUROC of the AA score was 0.636 (95% CI: 0.537–0.735). The addition of the AA score to low muscle strength in women as a predictor of sarcopenia improved the AUROC by 17.9%, from 0.576 (95% CI: 0.501–0.651; HGS only) to 0.680 (95% CI: 0.583–0.776, p = 0.018; HGS + AA score) in the validation cohort.

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that men with sarcopenia had significantly lower circulating levels of all three BCAAs (Ile, Leu, and Val), three EAAs (Met, Phe, and Trp), and three non-EAAs (α-AAA, Glu, and MetO) than the controls, while women with sarcopenia had significantly lower Glu levels. All of these AAs were associated with sarcopenia parameters such as SMI and/or HGS. Specifically, in men, Leu and Glu levels were shown to be independently associated with SMI, while Leu levels alone were shown to be associated with HGS. Moreover, a one SD increase in Leu levels reduced the odds of low muscle strength and low muscle mass by 50% and 58%, respectively. Similarly, a one SD increase in Glu levels reduced the odds of low muscle mass by 41%. In women, Glu levels were shown to be independently associated with SMI. A one SD increase in Glu levels reduced the odds of low muscle mass by 55%. Furthermore, AUROC analysis showed that adding the AA score of men to HGS significantly improved the predictive performance of HGS for sarcopenia across two independent cohorts, with increases of 18.8% and 36.2% in the discovery and validation cohorts, respectively. Similarly, AUROC analysis showed that adding the AA score of women to HGS significantly improved the predictive performance of HGS for sarcopenia across two independent cohorts, with increases of 49.7% and 17.9% in the discovery and validation cohorts, respectively. These findings suggest that Leu and Glu in men, and Glu in women, could serve as potential clinical biomarkers for sarcopenia diagnosis. We extended prior association studies using > 500 participants by deriving an AA score linked to SMI, demonstrating additive diagnostic performance over HGS with significant AUROC gains, and externally validating these findings in an independent cohort, highlighting sex-specific biomarker patterns.

BCAAs are crucial for maintaining and increasing muscle mass as they are intricately involved in muscle protein synthesis, activation of satellite cells, and inhibition of proteolysis28. Our study showed that lower levels of circulating BCAAs were associated with a higher risk of sarcopenia in men, a result consistent with those of previous studies17,19,21,22,23,24,26,27. The correlation between low levels of some EAAs and age has been reported in both sexes and is purportedly associated with decreases in total energy and protein intake29. In addition, low EAA plasma levels were shown to be associated with a higher risk of sarcopenia in older adults13,17,19,25,26. Our results showing that low levels of Met, Phe, and Trp are associated with a higher risk of sarcopenia in men are consistent with these reports. In addition, Leu is known to be a potent stimulator of skeletal muscle protein synthesis via the activation of the mTOR complex-1 signaling pathway30. The significant independent association of Leu with both low muscle strength and low muscle mass observed in our study is consistent with that reported for Japanese individuals with type 2 diabetes22.

Our results also showed that low levels of some non-EAAs (α-AAA, Glu, and MetO) in men, and low levels of Glu in women, were associated with a higher risk of sarcopenia. In particular, our finding of low levels of α-AAA, the specific final oxidation product of lysine31, in men with sarcopenia was consistent with the result of previous study17. Furthermore, the low level of MetO, derived from Met oxidation32, may corroborate the low levels of Met. Glu is metabolized in resting muscles and provides the amino groups and ammonia necessary for Gln and Ala synthesis, which are released after protein intake and in the post-absorptive state33. In contrast to some previous studies that reported a positive association of Glu levels with sarcopenia13, our study found an inverse association of Glu levels with sarcopenia in both sexes, consistent with other reports22,23,34. The reasons for these opposing results are unclear but may be due to the small sample size (n = 27) and ethnic differences13.

Because sex is known to have a great impact on plasma metabolic profiling35, we aimed to detect plasma AA metabolites in both men and women. The results of the present study showed that men exhibited more AA metabolites with differences between the sarcopenia and control groups than women. PCA and multivariate analysis indicated Leu as a male-specific AA metabolite signature reflecting both low muscle strength and low muscle mass. In contrast, Glu, reflecting low muscle strength, was identified as a common AA metabolite signature for sarcopenia in both sexes.

AUROCs of single AA (0.64–0.71) and of AA score around (0.71–0.73) indicated modest predictive ability and were lower than those of phosphatidylinositol 32:1 as a lipid-related metabolite (0.94)7 and hypoxanthine (0.82)8 in single cohort studies (< 100 participants). To improve prediction ability for diagnosis of sarcopenia, the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) 20191 recommends SARC-CalF (adding calf circumference [CC] to Strength, Assistance in walking, Rising from a chair, Climbing stairs, Falls [SARC-F] questionnaires) and the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2) 20192 recommends Ishii test (adding age and CC to HGS). Despite significant geographical and ethnic differences, SARC-CalF improved AUROC over SARC-F alone by about + 0.10 and + 0.1836,37 and Ishii test improved AUROC over HGS alone by about + 0.0636. In this context, the incremental improvement from adding our AA score to HGS (+ 0.10 to + 0.24 across two independent cohorts and both sexes) was comparable to, or greater than those from SARC-CalF and Ishii test. This supports the pragmatic clinical value of a blood-based AA score as an adjunct to HGS rather than a stand-alone diagnostic.

Although smoking status differed significantly between sarcopenic and control men, adjusting for smoking did not materially alter the association of Leu with low muscle strength or the associations of both Leu and Glu with low muscle mass. We also found no evidence of effect modification by smoking status. Prior meta-analysis reported a positive association between sarcopenia and hypertension38. In our cohort, however, women with sarcopenia had a lower prevalence of hypertension than controls, likely reflecting lower BMI/adiposity among sarcopenic women. Consistent evidence links sarcopenia to lower BMI and diastolic pressure39 and shows that sarcopenic obesity strengthens the sarcopenia–hypertension association38. Importantly, adjusting for hypertension did not materially change the alter the association of Glu with low muscle mass, and no effect modification by hypertension was observed.

Our study’s strengths include the relatively large sample size of older populations with matched controls and the use of an independent validation cohort to assess the utility of AAs as biomarkers for sarcopenia in a clinical context. Both the AWGS 2019 algorithm1 and the EWGSOP 2019 algorithm2 emphasize low muscle strength as a possible/probable sarcopenia for confirmation of sarcopenia by additional documentation of low muscle mass/quantity. Demonstrating additive diagnostic performance over HGS with AA score supported the potential clinical utility of AAs as biomarkers.

However, there are some limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional design of the study prevents the inference of causal relationships between the identified metabolites and sarcopenia. Secondly, we assessed circulating AA metabolites at a single baseline time point and did not evaluate dynamic processes (absorption, synthesis, metabolism, degradation) for Leu and Glu, limiting causal inference. Prospective evidence indicates the association between baseline serum AA patterns with 4-year incident sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults27. Future studies are needed to determine whether our sex-specific AA score predicts incident sarcopenia over time and to evaluate AA kinetics (e.g., synthesis/degradation. Thirdly, although we exclude medications that could affect muscle mass and function, unknown drug-related effects cannot be ruled out40. Finally, participants were Korean, and the discovery cohort was recruited at a veterans’ hospital, where many participants were former service members with habitual walking-based exercise; consequently, chair-stand test scores did not differ significantly between cases and controls. These features may limit generalizability and may reflect preserved lower-leg strength; therefore, replication in diverse populations is warranted.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that Leu in men, reflecting low muscle strength, and Leu in men and Glu in both sexes, reflecting low muscle mass, are potential circulating biomarkers for sarcopenia. Further studies on AA metabolites are needed to confirm these results and provide more insights into the metabolomic changes relevant to the pathogenesis and diagnosis of sarcopenia.

Methods

Study participants

Two independent case-control studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Veterans Health Service Medical Center (IRB No. 2020-02-015) and AMC (IRB No. 2017 − 0553) and conducted in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment.

For the discovery cohort, participants aged ≥ 65 years who visited the Division of Endocrinology, Department of Internal Medicine, Veterans Health Service Medical Center (Seoul, Korea) to undergo comprehensive geriatric assessment between August 2020 and March 2021 were enrolled in the “Veterans Sarcopenia Study”41. Before the study, all participants completed medical history and SARC-F questionnaires, and underwent muscle mass measurements, muscle strength tests, and blood sampling.

The validation cohort included patients who visited AMC (Seoul, Korea) between May 2017 and March 2020 to undergo comprehensive assessment for musculoskeletal disorders. All participants completed questionnaires, including medical history, and underwent muscle mass measurements, muscle strength tests, and blood sampling before the study.

Assessment of sarcopenia

Body composition was evaluated using bioelectrical impedance analysis (InBody 570, Biospace Co., Seoul, Korea) for the discovery and validation cohorts. All measurements were performed in the morning after an overnight fast (≥ 8 h), with participants voiding within 30 min before assessment. To minimize fluid-balance variation, participants were instructed to avoid alcohol and vigorous exercise for 24 h and not consume large volumes of water for ≥ 2 h prior to measurement. ASM was calculated as the sum of the muscle mass in both arms and legs, and SMI was calculated by dividing ASM by height squared to ensure an objective comparison of muscle mass between participants. HGS was measured a representative of muscle strength using a digital hand dynamometer (T.K.K 5401, Takei, Tokyo, Japan) in the discovery and validation cohorts. Participants were instructed to exert maximum grip strength twice with each hand while standing with forearms fully extended in a sideways position away from the body at thigh level; the dominant hand was recorded. Low muscle mass was defined as SMI < 7.0 kg/m2 in men and < 5.7 kg/m2 in women, and low muscle strength was defined as HGS < 28.0 kg in men and HGS < 18.0 kg in women, according to the consensus of the AWGS 20191. Where conflicting results were obtained for SMI and HGS, the diagnosis of sarcopenia was determined based solely on SMI.

Participants with a life expectancy of less than 1 year due to malignancy, and those with chronic diseases (heart failure, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, chronic kidney disease) and those using medications (such as glucocorticoid, androgen deprivation therapy, testosterone, cytotoxic chemotherapy, or systemic antibiotics) that could affect muscle mass and function, were excluded. Participants with nutrition intake problem were excluded if, at screening, they had any of the following within the prior 7 days: nil per os, enteral tube feeding or total parenteral nutrition, or acute gastrointestinal conditions (e.g., severe vomiting/diarrhea). In the discovery cohort, blood samples were collected from 313 eligible participants in the Veterans Sarcopenia Study cohort after excluding ineligible participants41,42,43, and controls were matched in a 1:1 ratio for age, within a range of ± 2 years, for each case (Supplementary Fig. S2). In the validation cohort, controls were matched within a range of ± 2 years, for each case (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Sample preparation and quantitative analysis of AAs and bioamines in human plasma

Metabolite standards, internal standards, and derivatization reagents were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA) and CDN isotopes (Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada). All solvents, including water, were purchased from J. T. Baker Chemicals (Mumbai, India). To 50 µL of human plasma, 50 µL of internal standard solutions (10 µM 13C5-glutamine, 0.4 µM serotonine-d4, 0.6 µM dopamine-d4, and 2 µM tryptophan-d5) were added. Sample solutions were prepared by liquid-liquid extraction procedure known as the Bligh/Dyer method, with minor modifications44. Briefly, 400 µL of chloroform/methanol (1/2, v/v) was added to each sample solution and mixed well. The solution was centrifuged for 15 min at 18,407 g. After centrifugation, AAs and bioamines remained in the upper aqueous phase which was used for chemical derivatization with phenyl isothiocyanate. After the reaction, derivatized AAs were extracted with 100 µL of 5 mM ammonium acetate in MeOH and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. AAs and bioamines were analyzed with an LC-MS/MS equipped with a 1290 high-performance liquid chromatography device (HPLC; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Qtrap 5500 (ABSciex, Framingham, MA, USA). A total of 3 µL of each sample solution was injected into the LC-MS/MS system and ionized with a turbo spray ionization source. A Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 column (100 × 2 mm; Agilent Technologies) was used. As mobile phases A and B, 0.2% formic acid in H2O and 0.2% formic acid in acetonitrile were used, respectively. The separation gradient was as follows: hold at 0% B for 0.5 min, 0–95% B for 5 min, 95% B for 1 min, and 95–0% B for 0.5 min, then hold at 0% B for 2.5 min. The LC flow rate was 500 µL/min, and the column temperature was maintained at 50 °C. Multiple reaction monitoring was used in positive ion mode. Data analysis was performed using Analyst 1.7.2 software (ABSciex). Extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) corresponding to each metabolite were used for quantitation. The area under the curve of each EIC was normalized to that of the corresponding internal standard. The calibration curves ranged from 1 nM to 600 µM, with R2 > 0.98.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD, median [interquartile range, IQR], or number (%). Continuous variables were compared between groups using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, depending on the data distribution. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. The normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, with a p value < 0.05 indicating a non-normal distribution. Due to the skewness in the distribution of AA metabolite levels, log transformation was applied to normalize the data. We then assessed potential non-linearity of the log-transformed AAs using natural cubic splines (df = 3–4) and GAMs (restricted maximum likelihood [REML], smoothing basis k = 4). Non-linear specifications were compared with linear models using F-tests or LRTs and information criteria (AIC and BIC). Unless a non-linear term materially improved fit and altered inference, we retained the linear specification for parsimony and interpretability.

Linear regression analyses were conducted to explore the associations between AA metabolite levels and sarcopenia parameters (SMI and HGS). Given the potential high correlation among circulating AAs, PCA was performed on AA metabolites that showed significant differences in levels between sarcopenia cases and controls. This approach helps mitigate multicollinearity issues and enhances the robustness of subsequent regression models. Following PCA, the selected AA metabolites underwent multivariate regression analysis using backward elimination to refine the model. Thereafter, unadjusted logistic regression analyses were performed to generate ORs with 95% CI, thereby evaluating the relationship between AA levels and sarcopenia. We calculated the AA score, a diagnostic regression equation for sarcopenia, based on linear regression analysis with SMI or HGS in discovery cohort to evaluate the predictive potential of AA metabolites.

The predictive capability of clinical variables and AA levels in identifying sarcopenia was assessed using AUROC. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

Data generated/analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AAs:

-

Amino acids

- α-AAA:

-

α-aminoadipic acid

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criteria

- AMC:

-

Asan medical center

- ASM:

-

Appendicular skeletal muscle mass

- AUROC:

-

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- AWGS:

-

Asian working group for sarcopenia

- BCAAs:

-

Branched-chain amino acids

- BIC:

-

Bayesian information criteria

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CC:

-

Calf circumference

- df:

-

Degrees of freedom

- EAAs:

-

Essential amino acids

- edf:

-

Effective degrees of freedom

- EIC:

-

Extracted ion chromatograms

- EWGSOP:

-

European working group on sarcopenia in older people

- GAMs:

-

Generalized additive models

- Glu:

-

Glutamate

- HFS:

-

Hand grip strength

- HPLC:

-

High-performance liquid chromatography

- Ile:

-

Isoleucine

- LC–MS/MS:

-

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

- Leu:

-

Leucine

- LRTs:

-

Likelihood-ratio tests

- Met:

-

Methionine

- MetO:

-

Methionine sulfoxidel

- non-EAAs:

-

Non-essential amino acids

- ORs:

-

Odds ratios

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- Phe:

-

Phenylalanine

- REML:

-

Restricted maximum likelihood

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SARC-F:

-

Strength, assistance in walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, falls

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SMI:

-

Skeletal muscle mass index

- Trp:

-

Tryptophan

- Val:

-

Valine

- 95% CIs:

-

95% confidence intervals

References

Chen, L. K. et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 300–307e302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012 (2020).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 48, 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169 (2019).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J., Sayer, A. A. & Sarcopenia Lancet 393, 2636–2646. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31138-9 (2019).

Norman, K. & Otten, L. Financial impact of sarcopenia or low muscle mass - a short review. Clin. Nutr. 38, 1489–1495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.09.026 (2019).

Pugh, T. D. et al. A shift in energy metabolism anticipates the onset of sarcopenia in rhesus monkeys. Aging Cell. 12, 672–681. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12091 (2013).

Liu, J. C. et al. Multi-omics research in sarcopenia: current progress and future prospects. Ageing Res. Rev. 76, 101576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2022.101576 (2022).

Hsu, W. H. et al. Novel metabolic and lipidomic biomarkers of sarcopenia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 15, 2175–2186. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13567 (2024).

Han, P. et al. Metabolic signatures and risk of sarcopenia in suburb-dwelling older individuals by LC-MS-based untargeted metabonomics. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15, 1308841. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1308841 (2024).

Brook, M. S. et al. Skeletal muscle homeostasis and plasticity in youth and ageing: impact of nutrition and exercise. Acta Physiol. (Oxf). 216, 15–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.12532 (2016).

Dato, S. et al. Amino acids and amino acid sensing: implication for aging and diseases. Biogerontology 20, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-018-9770-8 (2019).

Pasini, E. et al. Protein-amino acid metabolism disarrangements: the hidden enemy of chronic age-related conditions. Nutrients 10, 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040391 (2018).

Ali, S. R., Nkembo, A. T., Tipparaju, S. M., Ashraf, M. & Xuan, W. Sarcopenia: recent advances for detection, progression, and metabolic alterations along with therapeutic targets. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 102, 697–708. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2024-0201 (2024).

Calvani, R. et al. A distinct pattern of Circulating amino acids characterizes older persons with physical frailty and sarcopenia: results from the BIOSPHERE study. Nutrients 10, 1691. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111691 (2018).

Calvani, R. et al. Amino acid profiles in older adults with frailty: secondary analysis from metabofrail and BIOSPHERE studies. Metabolites 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo13040542 (2023).

Dai, M., Lin, T., Yue, J. & Dai, L. Signatures and clinical significance of amino acid flux in sarcopenia: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 12, 725518. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.725518 (2021).

Duan, Y., Tao, K., Fang, Z. & Lu, Y. Possible-sarcopenic screening with disturbed plasma amino acid profile in the elderly. BMC Geriatr. 23, 427. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04137-0 (2023).

Lo, C. J. et al. Metabolic signatures of muscle mass loss in an elderly Taiwanese population. Aging (Albany NY). 13, 944–956. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.202209 (2020).

Lo, J. H., U, K. P., Yiu, T., Ong, M. T. & Lee, W. Y. Sarcopenia: current treatments and new regenerative therapeutic approaches. J. Orthop. Translat. 23, 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jot.2020.04.002 (2020).

Lu, Y. et al. Systemic and metabolic signature of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz001 (2020).

Luo, J., Li, J., Wang, W., Zhang, R. & Zhang, D. Identifying the shared metabolite biomarkers and potential intervention targets for multiple Sarcopenia-Related phenotypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252212310 (2024).

Lustgarten, M. S., Price, L. L., Chale, A., Phillips, E. M. & Fielding, R. A. Branched chain amino acids are associated with muscle mass in functionally limited older adults. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 69, 717–724. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glt152 (2014).

Nakajima, H. et al. Leucine and glutamic acid as a biomarker of sarcopenic risk in Japanese people with type 2 diabetes. Nutrients 15, 2400. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102400 (2023).

Opazo, R. et al. Sarcopenic metabolomic profile reflected a sarcopenic phenotype associated with amino acid and essential fatty acid changes. Metabolomics 17, 83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11306-021-01832-0 (2021).

Ottestad, I. et al. Reduced plasma concentration of branched-chain amino acids in sarcopenic older subjects: a cross-sectional study. Br. J. Nutr. 120, 445–453. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114518001307 (2018).

Toyoshima, K. et al. Increased plasma proline concentrations are associated with sarcopenia in the elderly. PLoS One. 12, e0185206. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185206 (2017).

Yamada, M. et al. Plasma amino acid concentrations are associated with muscle function in older Japanese women. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 22, 819–823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1014-8 (2018).

Yeung, S. S. Y., Zhu, Z. L. Y., Kwok, T. & Woo, J. Serum amino acids patterns and 4-year sarcopenia risk in community-dwelling Chinese older adults. Gerontology 68, 736–745. https://doi.org/10.1159/000518412 (2022).

Le Couteur, D. G. et al. Branched chain amino acids, aging and age-related health. Ageing Res. Rev. 64, 101198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2020.101198 (2020).

Kouchiwa, T. et al. Age-related changes in serum amino acids concentrations in healthy individuals. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 50, 861–870. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2011-0846 (2012).

Bajotto, G., Sato, Y., Kitaura, Y. & Shimomura, Y. Effect of branched-chain amino acid supplementation during unloading on regulatory components of protein synthesis in atrophied soleus muscles. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 111, 1815–1828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-010-1825-8 (2011).

Requena, J. R., Chao, C. C., Levine, R. L. & Stadtman, E. R. Glutamic and aminoadipic semialdehydes are the main carbonyl products of metal-catalyzed oxidation of proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 98, 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.98.1.69 (2001).

Aussel, L. & Ezraty, B. Methionine redox homeostasis in protein quality control. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 665492. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2021.665492 (2021).

Wagenmakers, A. J. Muscle amino acid metabolism at rest and during exercise: role in human physiology and metabolism. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 26, 287–314 (1998). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9696993

Meng, L. et al. Specific lysophosphatidylcholine and acylcarnitine related to sarcopenia and its components in older men. BMC Geriatr. 22, 249. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02953-4 (2022).

Krumsiek, J. et al. Gender-specific pathway differences in the human serum metabolome. Metabolomics 11, 1815–1833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11306-015-0829-0 (2015).

Guo, Q., Chen, Q. & Chen, K. Comparative analysis of SARC-F-EBM, Ishii test, and six other screening tools for sarcopenia in Chinese community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional diagnostic study. Sci. Rep. 14, 24679. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75975-0 (2024).

Vanitcharoenkul, E. et al. Evaluating SARC-F, SARC-CalF, and calf circumference as diagnostic tools for sarcopenia in Thai older adults: results from a nationwide study. BMC Geriatr. 24, 1043. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05637-3 (2024).

Quan, Y., Wang, C., Wang, L. & Li, G. Geriatric sarcopenia is associated with hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich). 25, 808–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.14714 (2023).

Meng, N. H. et al. Comparison of height- and weight-adjusted sarcopenia in a Taiwanese metropolitan older population. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 15, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12227 (2015).

De Spiegeleer, A. et al. The association between Statins and gait speed reserve in older adults: effects of concomitant medication. GeroScience https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-025-01682-x (2025).

Kim, Y. A. et al. Fatty acid amides as potential Circulating biomarkers for sarcopenia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 14, 1558–1568. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13244 (2023).

Seo, J. H. et al. Sphingolipid metabolites as potential Circulating biomarkers for sarcopenia in men. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 15, 2476–2486. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13582 (2024).

Seo, J. H. et al. Carnitine metabolite as a potential Circulating biomarker for sarcopenia in men. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul). 40, 93–102. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2024.2117 (2025).

Bligh, E. G. & Dyer, W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917. https://doi.org/10.1139/o59-099 (1959).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Asan Institute for Life Sciences Grant (grant number: 2023IP0041), by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project (grant number: RS-2024-00401153) and a grant of Korean ARPA-H Project (grant number: RS-2024-00507183) through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea, and grants of the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT; grant numbers: 2022R1C1C1002929 and RS-2024-00399341).Supporting source had no such involvement in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report or restrictions regarding the submission of the report for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JHS, J-MK, HJY, and SHL conceptualized and designed the study. JHS, J-MK, SJK, PWY, WK, SJB, HKK, HJY, and SHL contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. JHS, J-MK, HJY, and SHL conducted the statistical analysis and provided administrative, technical, or material support. JHS, J-MK, HJY, and SHL wrote and revised the manuscript. JHS, J-MK, HJY, and SHL supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seo, J.H., Koh, JM., Kim, S.J. et al. Amino acid metabolites as potential circulating biomarkers for sarcopenia. Sci Rep 15, 40708 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24223-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24223-0