Abstract

Low-light (LL) stress imposes a major constraint on rice yield in densely planted and monsoonal environments, yet the mechanistic basis of shade tolerance remains insufficiently resolved. We investigated four rice genotypes under simulated LL conditions, including two LL-tolerant varieties (Purnendu and Swarnaprabha) and two LL-susceptible varieties (IR64 and IR8). Responses were systematically analysed from the flag leaf to the fourth leaf. Comprehensive evaluation included measurements of light interception, chlorophyll fluorescence, gas exchange, carbohydrate content, chloroplast ultrastructure, and the expression of fourteen photosynthesis-related genes. Our findings demonstrate that LL tolerance in rice cannot be explained by adaptation of a single leaf; rather, it results from a coordinated strategy involving integrated changes at morphological, physiological, biochemical, and gene expression levels throughout the entire canopy. Tolerant genotypes exhibited only 30–35% loss in photons from the flag leaf to the fourth leaf, whereas susceptible genotypes lost up to 75%. Architectural traits such as plant height, leaf area plasticity, and leaf angle accounted for 84% of the variation in radiation use efficiency, while tolerant genotypes sustained higher photosynthetic efficiency, carbohydrate reserves, and robust gene expression across all layers. These insights identify concrete trait targets for breeding LL-resilient rice varieties, supporting stable yield in dense and light-limited environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is the principal staple food and calorie source for more than half of the global population, supporting the daily nutrition of over 3.5 billion people1. Cultivated in diverse environments ranging from upland rainfed fields to irrigated lowlands, rice accounts for more than 90% of Asia’s caloric supply1. Despite major achievements in breeding, agronomy, and biotechnology, yield gains in rice have plateaued in recent years, especially in densely populated and resource-limited regions2. This stagnation raises urgent concerns about future food security, given the dual pressures of global population growth and declining per capita arable land. Climate change further compounds the challenge, as increasingly erratic weather patterns impose stresses that constrain productivity. Among these stresses, low-light (LL) stress is one of the least studied yet most critical constraints in monsoon-season rice production.

During the Kharif (monsoon) season, rice frequently experiences LL stress caused by persistent cloud cover, high humidity, and dense planting3,4. Studies show that incident light at the canopy top may decrease by 25–40%, while the lower canopy leaves may receive up to 90% less light due to pronounced self-shading5,6. This steep attenuation of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) across vertical canopy layers has severe implications for productivity. Light reduction slows photochemical reactions7, delays photosynthetic activation8, decreases activities of key enzymes9, and compromises stomatal regulation10. Collectively, these disruptions reduce net photosynthetic rate and yield. Importantly, the decline in efficiency is not uniform, while the flag leaf (uppermost) retains partial function, photosynthesis deteriorates sharply from the second to fourth leaf layers, creating a vertical gradient of light use inefficiency within the canopy11,12.

The structure of the rice canopy plays a decisive role in determining how much light penetrates and is effectively utilised. Traits such as leaf inclination angle, lamina size, leaf arrangement, and chloroplast organisation shape intra-canopy light environments13,14. Leaf area plasticity, the ability of leaves to adjust their size and expansion in response to variable light availability, also represents an important structural trait. By influencing how light is distributed across canopy layers, this plasticity may help balance energy capture between upper and lower leaves, although its role in rice low-light tolerance has not been clearly defined15,16. While flag leaves are sun-adapted and optimised for high irradiance, lower canopy leaves operate under sub-saturating and fluctuating light regimes. To cope, plants adopt strategies such as thinner leaves17, dynamic adjustment of light-harvesting capacity18,19, altered chlorophyll composition20, and modulation of redox enzymes21,22. These adaptive mechanisms help sustain photosynthesis but may vary significantly across genotypes. Despite recognition of these processes, most existing research has focused narrowly on single traits, often in controlled environments. This reductionist approach leaves major gaps in understanding how multiple adaptive mechanisms interact under field-simulated LL stress.

Another poorly understood aspect is the layer-specific contribution of leaves to whole-canopy photosynthesis and yield. Since canopy shading and self-shading are unevenly distributed, each leaf layer may contribute differently to carbon assimilation23. Nevertheless, comprehensive field-based assessments across canopy gradients remain scarce. Addressing this gap requires multi-scale approaches that integrate canopy architecture, physiological performance, ultrastructural features, and gene expression.

Recent technological advances make such integration feasible. High-throughput field phenotyping tools, including reflectance spectroscopy24,25, transmission electron microscopy26, chlorophyll fluorescence imaging27, gas exchange modelling28, and gene expression profiling29, enable simultaneous assessment of structural, biochemical, and molecular traits. However, no study has yet combined these complementary methods to establish a systematic link between canopy shading, leaf structure, photosynthetic efficiency, gene regulation, and yield performance under real LL stress conditions.

To address these gaps, the present study investigated canopy-wide responses to LL stress in rice using a multi-scale, field-based approach. Two LL-tolerant genotypes (Swarnaprabha, Purnendu) and two susceptible genotypes (IR64, IR8) were evaluated under simulated low-light conditions during two consecutive Kharif seasons. We measured light distribution across canopy layers, canopy architecture and reflectance, pigment profiles, chloroplast ultrastructure, photosystem II efficiency, gas exchange dynamics, carbohydrate accumulation, and the expression of 14 photosynthesis-related genes.

Results

Light attenuation across canopy layers

The attenuation of photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) across the vertical canopy gradient from the flag leaf (FL) to the fourth leaf (4L) demonstrates critical genotype-dependent differences in light distribution efficiency under both normal light (NL) and low light (LL) conditions (p < 0.001). These variations strongly influence intra-canopy photosynthesis and overall plant performance. Purnendu, a shade-tolerant genotype, exhibited minimal light attenuation, with PPFD decreasing from ~ 1100 μmol m⁻2 s⁻1 at the FL to ~ 720 μmol m⁻2 s⁻1 at the 4L, an average loss of only ~ 30–35% (P < 0.05). Notably, this efficiency was sustained even under LL and in late-afternoon conditions, indicating a structurally open canopy that reduces self-shading and enhances sub-canopy light penetration. Swarnaprabha showed a moderate decline, with PPFD dropping from ~ 1000 μmol m⁻2 s⁻1 (FL) to ~ 550–600 μmol m⁻2 s⁻1 (4L), corresponding to a ~ 40–45% loss (p < 0.01–0.001). In contrast, IR64 experienced a sharper decrease (~ 55–60%), from ~ 950 μmol m⁻2 s⁻1 at FL to ~ 400 μmol m⁻2 s⁻1 at 4L (P < 0.05). IR8 exhibited the steepest reduction in light penetration, with PPFD plummeting from ~ 900 to ~ 250–300 μmol m⁻2 s⁻1 (~ 65–75% loss), particularly under LL at 3:00 p.m. (p < 0.001). These patterns, visualized in Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2, highlight contrasting canopy architectures and light transmission profiles, with denser upper foliage in IR64 and IR8 leading to greater self-shading and compromised lower canopy photosynthesis.

Canopy structure and plant height under low light

Low-light (LL) treatment triggered distinct architectural changes among rice genotypes (Fig. 1a–c): under normal light, Purnendu showed the highest visible and near-infrared reflectance, while IR64 and IR8 had much lower values (Fig. 1b). All genotypes exhibited an 18–22% reduction in canopy reflectance under LL, but tolerant genotypes maintained 10–12% higher reflectance than susceptible ones (P < 0.05). LL also increased plant height in all genotypes (Fig. 1c), with tolerant lines (Purnendu, Swarnaprabha) growing 10–15% taller (P < 0.001) and reaching up to 165 cm and 140 cm, while susceptible IR64 and IR8 had smaller gains (8–10%, P < 0.01) and remained shorter overall. Thus, tolerant genotypes sustain higher reflectance and greater height under LL, supporting a more light-efficient canopy than susceptible lines.

Rice varieties under simulated low light (LL) and normal light (NL) during Kharif 2022 and 2023. (a) Schematic of rice plant showing flag leaf (FL), second (2L), third (3L), and fourth (4L) leaves, with inclination angles (α, β, γ) between leaves and culm. FL represents the top canopy exposed to canopy shading (CSh), while lower leaves experience self-shading (SSh). (b) Canopy reflectance and (c) plant height in LL-tolerant (Purnendu, Swarnaprabha) and LL-susceptible (IR64, IR8) varieties during the reproductive stage. Values are means ± SE (n = 10). Error bars denote SE; significance by t-test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns = not significant).

Plastic adjustments in leaf and canopy morphology under LL

Under LL, tolerant genotypes, Purnendu and Swarnaprabha, exhibited a significantly (P < 0.05) greater leaf area and higher leaf area plasticity than susceptible genotypes, IR64 and IR8, across all canopy positions (Fig. 2a, b). In tolerant lines, leaf area at the FL increased by 36% and at the 4L by 29% compared to NL (P < 0.001), while susceptible genotypes showed smaller increases of 26% at FL and 30% at 4L (P < 0.001). Similarly, leaf area plasticity in tolerant genotypes rose by 31% at FL and 32% at 4L (P < 0.001), whereas susceptible lines showed only 22% (FL) and 21% (4L) increases (P < 0.001). Across the canopy, tolerant genotypes consistently sustained 20–35% higher absolute leaf area and 25–40% higher plasticity than susceptible lines under LL, and the decline from FL to 4L was less pronounced in tolerant genotypes, demonstrating enhanced capacity for morphological adjustment at all leaf layers (P < 0.001). Further, under shade, tolerant genotypes maintained 22–28% more leaves per plant than susceptible genotypes (P < 0.001; Fig. 2c, d). Compared to normal light, LL caused a 14% reduction in leaf number in tolerant genotypes and a greater 17–18% reduction in susceptible ones. However, the tolerant plants are also taller (Fig. 1c) and produce more leaves than susceptible genotypes, which together facilitate greater light penetration and allow more PPFD to reach the lower (4L) canopy leaves in tolerant lines compared to susceptible ones. Under LL, specific leaf area increased by 32% in tolerant genotypes (from 340 to 450 cm2/g) and by 30% in susceptible genotypes (from 325 to 425 cm2/g) (P < 0.05 for tolerant, P < 0.01 for susceptible; Fig. 2e). Specific leaf weight decreased by 18% in tolerant lines (from 0.0065 to 0.0053 cm2/g) and by 22% in susceptible genotypes (from 0.0063 to 0.0049 cm2/g) (P < 0.05; Fig. 2f). Leaf inclination angle declined by 16% in tolerant genotypes (from 38° to 32°) and by 11% in susceptible genotypes (from 37° to 33°) at the flag leaf, with similarly greater reductions at lower canopy layers in tolerant lines (P < 0.001; Fig. 2g).

Leaf traits of rice varieties (Purnendu, Swarnaprabha, IR64, IR8) grown under normal light (NL) and simulated low light (LL) during the reproductive stage (Kharif 2022–2023). Traits measured include (a) leaf area, (b) leaf area plasticity, (c) representative leaf morphology, (d) Leaves/plant, (e) specific leaf area (SLA), (f) specific leaf weight (SLW), and (g) leaf inclination angle at 50% flowering. Measurements in (a) and (b) were taken for flag (FL), second (2L), third (3L), and fourth (4L) leaves. Data represent means ± SE (n = 6). Asterisks denote statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Radiation use efficiency and biomass accumulation under shade

Radiation use efficiency (RUE) and biomass accumulation considerably decreased under low light (LL) conditions across all genotypes, with the most pronounced (P < 0.05) loss observed in sensitive genotypes (Table 1). Under LL, RUE reached its peak in Purnendu (1.84 g MJ⁻1) and Swarnaprabha (1.64 g MJ⁻1), but IR64 and IR8 had significantly (P < 0.01) lower RUE values of 0.76 g MJ⁻1 and 0.88 g MJ⁻1, respectively (P < 0.05). The reduction in RUE from NL to LL was 9.4% for Purnendu, 10.9% for Swarnaprabha, 51.6% for IR64, and 41.7% for IR8. Similarly, Purnendu and Swarnaprabha maintained greater (P < 0.05) biomass, 349.47 g m⁻2 and 326.47 g m⁻2, respectively, but IR64 and IR8 suffered more significant (P < 0.05) reductions, decreasing to 106.47 g m⁻2 and 113.47 g m⁻2, respectively (P < 0.05).

Chlorophyll composition and chloroplast ultrastructure under low light

Low light significantly increased total chlorophyll content from the flag leaf (FL) to the fourth leaf (4L) in all genotypes (Fig. 3a; P < 0.05). Purnendu showed a 15% rise in the FL and 18% in the 4L (P < 0.01), Swarnaprabha 12% and 13% (P < 0.05), IR64 12% and 11% (P < 0.05), and IR8 10% and 12% (P < 0.01). The chlorophyll a/b ratio declined across the canopy (Fig. 3b), with Purnendu decreasing by 16%, 14%, 15%, and 16% from FL to 4L (P < 0.05), Swarnaprabha by 13% (FL) to 17% (4L; P < 0.01), and IR64/IR8 by 13–16% (P < 0.01). Overall, tolerant genotypes maintained 10–15% higher total chlorophyll and 8–12% lower a/b ratios than susceptible lines under low light (P < 0.01; Fig. 3a, b).

Chlorophyll content in rice varieties (Purnendu, Swarnaprabha, IR64, IR8) under normal light (NL) and simulated low light (LL) during the reproductive stage (Kharif 2022 and 2023). (a) Total chlorophyll (Chl a + b), (b) chlorophyll a/b ratio in flag (FL), second (2L), third (3L), and fourth (4L) leaves at 50% flowering. Data represent mean of six replicates across both seasons. Asterisks indicate significance by t-test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

At the ultrastructural level, tolerant genotypes exhibited a greater increase in the number of grana per chloroplast (35.9% in Purnendu and 26.2% in Swarnaprabha) compared to susceptible genotypes (19.2% in IR64 and 19.6% in IR8) (P < 0.05). The average number of thylakoids per granum rose by 54.8% and 59.9% in tolerant lines, markedly exceeding the 43.9% and 49.9% increases observed in susceptible genotypes (P < 0.05). In contrast, the number of starch grains per chloroplast was reduced to zero in all genotypes under low light, with no significant difference between tolerant and susceptible groups. The reduction in plastoglobuli per chloroplast was also significantly greater in tolerant genotypes (70.6% in Purnendu, 70.0% in Swarnaprabha) than in susceptible genotypes (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Canopy-level photochemical efficiency and electron transport under LL

Under LL, tolerant genotypes showed greater increases (P < 0.05) in Fv/Fm in the flag leaf (12.5% in Purnendu, 13.5% in Swarnaprabha) compared to IR64 (7.3%) and IR8 (4.4%), and this advantage persisted down to the fourth leaf, where Fv/Fm was largely (P < 0.05)maintained in tolerant lines but declined by 7.0% (IR64) and 9.3% (IR8) in susceptibles. Photochemical quenching (qP) decreased (P < 0.05) in the flag leaf by 22.2% (Purnendu), 20.8% (Swarnaprabha), 34.3% (IR64), and 37.1% (IR8), with even sharper declines in the fourth leaf: 71.0%, 55.3%, 75.0%, and 90.0%, respectively. ETR also dropped (P < 0.05) in the flag leaf by 35.6% (Purnendu), 27.7% (Swarnaprabha), 41.6% (IR64), and 45.5% (IR8). These results highlight that tolerant genotypes better sustain photochemical efficiency and electron transport from the flag leaf to the bottom leaf under shade (Table S1; Fig. 4).

The chloroplast ultrastructure was observed in the flag leaves of the rice varieties Purnendu (a, e), Swarnaprabha (b, f), IR64 (c, g), and IR8 (d, h) during the reproductive stage. (a–h) represent the chloroplasts in normal light (NL) and low light (LL) conditions, respectively. The differences were observed in the number of thylakoid membranes (Th), starch granules (Sg), and plastoglobulin (Pg) as indicated by arrowheads in NL and LL conditions.

Canopy wide gas exchange and photosynthetic efficiency under LL

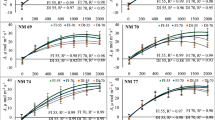

In LL conditions, stomatal conductance (gs) diminished (26%) (P < 0.05) from 0.61 to 0.45 mol H₂O m⁻2 s⁻1 in the flag leaf of Purnendu, from 0.59 to 0.44 (25%) in Swarnaprabha, from 0.54 to 0.39 (28%) in IR64, and from 0.51 to 0.35 (31%) in IR8, with comparable or higher decreases seen from FL to 4L across all genotypes (Fig. 5a). The photosynthetic rate (PN) exhibited a similar pattern, diminishing (P < 0.05) in the flag leaf from 24.8 to 17.0 μmol CO2 m⁻2 s⁻1 (31%) in Purnendu, from 26.1 to 18.2 (30%) in Swarnaprabha, from 23.3 to 14.5 (38%) in IR64, and from 22.8 to 14.1 (38%) in IR8, with successive reductions observed in the lower canopy leaves (Fig. 5b). Light response curves indicated significant (P < 0.05) decreases in maximum photosynthetic rate (Pmax) and apparent quantum yield (AQE) across all genotypes under LL conditions, with the most pronounced reductions noted in IR64 and IR8 (Fig. 6). Additionally, from the FL to the 4L under LL, tolerant genotypes maintained significantly higher stomatal conductance by 12–15% (P < 0.05), and photosynthetic rate, by 18–22% (P < 0.01), at every canopy position compared to susceptible genotypes.

Gas exchange traits in rice varieties (Purnendu, Swarnaprabha, IR64, IR8) under normal light (NL) and simulated low light (LL) during the reproductive stage (Kharif 2022 and 2023). (a) Stomatal conductance (gs), (b) photosynthetic rate (PN) of flag (FL), second (2L), third (3L), and fourth (4L) leaves at 50% flowering. Data are means of six replicates averaged over both seasons. Asterisks denote significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, by t-test).

Photosynthetic light response curves of rice varieties (Purnendu, Swarnaprabha, IR64, and IR8) under normal light (NL) and simulated low light (LL) during the reproductive stage (Kharif 2022 and 2023). (a–d) Net CO₂ assimilation (PN) was measured in flag leaves across a gradient of increasing photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD; 0–1600 µmol photons m⁻2 s⁻1) at a leaf temperature of 25 ± 1 °C and reference CO₂ concentration of ~ 400 µmol mol⁻1. LL-treated leaves were measured under their native light conditions, without pre-exposure to high light, to preserve in situ low-light physiological state. (e–h) Apparent quantum yield (initial slope of the light response curve) was derived from the linear range (0–200 µmol photons m⁻2 s⁻1). Data represent means ± SE (n = 5 plants per variety and treatment, averaged across two seasons). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between NL and LL within each genotype (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, by t-test).

Carbohydrate content and diurnal partitioning

Carbohydrate partitioning exhibited strong diurnal and canopy gradients (Fig. 7a–c). Total carbon content (TC) declined by ~ 20–25% under LL across all layers. Purnendu maintained higher TC (~ 34 mg g⁻1 at FL) compared to IR64 (~ 25 mg g⁻1) and IR8 (~ 15 mg g⁻1 at 4L) (p < 0.01). TSS increased throughout the day in tolerant genotypes by ~ 15–20%, peaking at ~ 12 mg g⁻1 in Swarnaprabha. In IR64/IR8, TSS remained lower (< 8 mg g⁻1) with flatter temporal profiles (p < 0.001). Starch levels remained constant in Purnendu but increased (~ 10–15%) in other genotypes late in the day, suggesting differences in sugar export efficiency.

Carbohydrate dynamics in rice leaves under shading stress (Purnendu, Swarnaprabha, IR64, IR8) during Kharif 2022 and 2023 under normal light (NL) and simulated low light (LL). (a) Total carbon content (TC) across flag (FL), second (2L), third (3L), and fourth (4L) leaves. (b) Total soluble sugars content (TSS) and (c) Leaf starch content in FL estimated at 6:00, 9:00, 11:00, and 17:30 h. Data are means ± SE (n = 6). Asterisks indicate significance by t-test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001); ns = not significant.

Expression of light-harvesting and calvin cycle genes

Under low light, all light-harvesting complex (LHC) genes, OsLhcb29.1, OsPSB27-H1, and OsPSII10, were upregulated significantly (P < 0.05) compared to normal light in all rice genotypes (Fig. 8). This upregulation was most pronounced in the tolerant genotypes: Purnendu showed more than twofold higher expression, and Swarnaprabha around 1.5-fold, while susceptible genotypes IR64 and IR8 exhibited much smaller increases, i.e., less than 1.2-fold. However, the expressions of Calvin cycle–associated genes, OsSBPase, OsRCAL, OsGAPA, OsGAPB, OsRbcS2, OsRbcS3, OsRbcS4, OsRbcL, OsFBPase, OsPRK, and OsTXF, were consistently and significantly (P < 0.01) downregulated under LL in all genotypes. Under low light, susceptible genotypes showed much stronger downregulation of Calvin cycle genes (fold change < 0.5, P < 0.05), while tolerant genotypes had milder decreases and higher LHC gene upregulation.

Relative expression of photosynthesis-related genes in flag leaves of rice varieties (Purnendu, Swarnaprabha, IR64, IR8) under low light (LL) compared to normal light (NL) during flowering, assessed by qRT-PCR. Genes include Photosystem II-related (OsLhcb29.1, OsPSB27-H1, OsPSII10) and Calvin cycle-associated (OsSBPase, OsRCAL, OsGAPA, OsGAPB, OsRbcS2, OsRbcS3, OsRbcS4, OsRbcL, OsFBPase, OsPRK, OsTXF). Actin was used as the internal control. Primer sequences are listed in Table S3. Data are means ± SE (n = 3). Asterisks denote significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Yield components and grain productivity under shade

Low-light stress sharply reduced yield components, with tolerant genotypes (Purnendu, Swarnaprabha) showing much smaller declines in panicle number (7–9%), spikelet fertility (15–17%), thousand-grain weight (11–12%), and grain yield (13–18%), compared to susceptible lines (IR64, IR8), which lost 32–33%, 41–49%, 31–42%, and 40–51% respectively (P < 0.05). These results highlight the superior yield stability of tolerant genotypes under low-light stress (Table S2).

Correlations and SEM-based ranking of traits linked to yield under low light

Strong positive correlations were found between lower canopy PPFD and structural traits—plant height, leaf angle, and leaf area plasticity (r = 0.96–0.99, P < 0.01). RUE also correlated closely with these traits and with grain yield (r = 0.96–0.99, P < 0.001), highlighting the benefits of open, plastic canopies. Chlorophyll content was positively associated with photosynthetic rate and Fv/Fm (r > 0.95, P < 0.05), and both Fv/Fm and ETR correlated with grain yield, RUE, and Pn (r > 0.90, P < 0.01). Collectively, these relationships emphasize the central role of canopy structure, photochemical efficiency, and physiological plasticity for yield stability under shade (Fig. 9, Supplementary Table S3). Further, structural equation modelling (SEM) clarified the hierarchy of trait contributions to yield under shade. Pn exerted the strongest direct effect on grain yield (β = 0.6–0.7), while ETR strongly supported Pn (β = 0.5–0.6). Upstream traits, including qP, Fv/Fm, and chlorophyll content, showed progressively lower indirect effects, and incident PPFD contributed least. The ranking of total effects reinforced that sustained carbon assimilation at the flag leaf is the central physiological driver of yield stability under low light (Supplementary Table S8).

Correlation plots of physiological and genetic traits under low light (LL) in rice during the reproductive stage. (a) Pearson’s correlation coefficients between leaf inclination angle (LIA), leaf area plasticity (LAP), photosynthesis (Pn), grain yield (GY), and radiation use efficiency (RUE) across leaf positions (FL, 2L, 3L, 4L). Values > 0.95, > 0.99, and > 0.999 denote significance at P < 0.05, < 0.01, and < 0.001, respectively. (b) Correlation (P-value) between photosynthetic rate and expression of associated genes (Table S7) in flag leaves. Significance levels: P ≤ 0.05 (95%), ≤ 0.01 (99%), and ≤ 0.001 (99.9%).

Discussion

Light limitation creates a unique set of physiological challenges for rice, impacting not only the surface leaves but extending deep within the canopy as shading intensifies. Our findings demonstrate that LL tolerance in rice cannot be explained by the adaptation of a single leaf; rather, it results from a concerted strategy involving integrated changes at the morphological, physiological, biochemical, and gene expression levels throughout the canopy from the flag leaf at the top to the fourth leaf at the bottom. Importantly, a three-way ANOVA revealed that both genotype and light treatment exert highly significant influences on these core architectural, physiological, and biochemical traits (Supplementary Table 4), emphasising the multifaceted nature of shade adaptation in rice.

Our data suggest that LL-tolerant rice genotypes maintain higher levels of PPFD throughout the canopy, from the flag leaf at the top to the fourth leaf at the bottom. In these tolerant lines, only a moderate reduction in PPFD occurs from the uppermost to the lowest leaf, whereas susceptible genotypes experience much steeper declines, leaving minimal light available to the lower canopy (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). This contrast is linked to a coordinated suite of foliar traits in tolerant genotypes, including increased plant height, progressively steeper leaf angles, and greater leaf area plasticity across canopy layers (Fig. 2). Such an arrangement facilitates deeper light penetration and more balanced internal light distribution, thereby sustaining photosynthetic activity and carbon assimilation in shaded leaves. Our observation that leaf angle and leaf area plasticity strongly influence internal light gradients is consistent with earlier reports. Mantilla-Perez and Salas Fernandez (2017)30 identified leaf angle as a key determinant of light interception efficiency, photosynthetic rate, and yield across cereals, and proposed ideotypes with steeper upper leaves and more horizontal lower leaves to optimise canopy photosynthesis. In contrast, susceptible genotypes exhibit a compact structure with less variation in leaf angle and reduced leaf area plasticity, restricting light penetration and lowering PPFD at the bottom leaves. These patterns are reinforced by strong positive correlations between lower-canopy PPFD and structural traits, including plant height, leaf inclination angle, and leaf area plasticity, with Pearson’s coefficients exceeding 0.95 (Fig. 9a, Supplementary Table 3). Our findings also align with models from maize31 and soybean32, where upright leaves and a vertical canopy structure promote light transmission, and with studies in shade-adapted forest species that use steep leaf angles to distribute light to deeper layers33,34. Extending these insights, our results show for the first time that some rice genotypes exhibit a stepwise increase in leaf angle from the top to the bottom of the canopy, a vertical pattern that may represent a novel trait for improving low-light tolerance in rice.

In addition to structural angles, the capacity to dynamically adjust photosynthetic surface area played a critical role. Despite LL stress, tolerant genotypes maintained larger leaf areas at 2L–4L and showed higher leaf area plasticity (LAP), i.e., ~ 30% under LL, suggesting a responsive allocation of foliar biomass to light-deprived zones. LAP was also significantly correlated with radiation use efficiency (RUE) and photosynthesis across canopy layers (Fig. 9a), indicating its role in supporting light capture efficiency and carbon gain. These findings align with earlier hypotheses in plant plasticity theory wherein spatial and developmental plasticity underlie shade adaptability and mirror trends seen in forest species that expand laminae to maximise light capture under chronic shade35,36. Furthermore, specific leaf area (SLA), another critical parameter, increased in tolerant genotypes under LL, reflecting thinner, optically permissive leaves that facilitate light transmission. This anatomical adjustment, together with elevated visible-NIR reflectance (by ~ 10–12%), suggests maintained mesophyll integrity and pigment profiles that enhance photon redistribution. Such spectral resilience has previously been linked to photosynthetic stability under diffuse radiation in crops like wheat and cassava37,38, supporting the interpretation that tolerant rice genotypes maintain not just light capture but intra-canopy optical economy.

Radiation use efficiency (RUE) emerged as a central trait distinguishing LL-tolerant and susceptible rice genotypes in our study. Tolerant genotypes maintained consistently higher RUE under shade (Table 1), demonstrating their superior ability to convert limited light into biomass and ultimately preserve yield39. This finding reinforces the idea that canopy optical properties, such as reflectance, are not just passive traits but active contributors to light use efficiency and yield stability under low-light stress40. Hyperspectral imaging (Fig. 1b) further supports this view: LL-tolerant genotypes exhibited stable visible and NIR reflectance, indicating that their mesophyll structure and pigment content remain intact even under stress. Such stability enhances internal light scattering, reduces photon loss, and helps explain why these genotypes experience less yield reduction compared to susceptible genotypes41. Taken together, these results highlight the critical role of whole-canopy optical and physiological adaptations in maintaining productivity in shaded environments.

Under shade conditions, LL-tolerant rice genotypes maintained higher total chlorophyll and a lower chlorophyll a/b ratio across all canopy layers (Fig. 3), helping them absorb light more efficiently in shade41. Further, they also had robust shade-adapted chloroplasts (Fig. 4), characterised by densely stacked grana and continuous thylakoid membranes, which makes it easier to capture light and transfer energy42. In contrast, susceptible genotypes exhibited lower chlorophyll content, higher chlorophyll a/b ratios, and chloroplasts less adapted to shade, characterised by fragmented lamellae, reduced starch granules, and enlarged plastoglobuli, features indicative of stress and compromised energy balance43. These differences in pigment composition and chloroplast structure are consistent with previous studies in rice44 and barley45, which have shown that well-formed grana and intact thylakoids under shade conditions support more efficient energy use and higher photosynthetic capacity.

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters revealed key differences in how rice genotypes respond to LL conditions. Our data show that LL-tolerant lines actively remodel PSII function, resulting in significantly higher Fv/Fm values from the flag leaf to the fourth leaf, especially in the most shaded lower strata (Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, susceptible genotypes displayed static or declining Fv/Fm profiles with canopy depth, indicating increased vulnerability to photoinhibition and impaired electron transport in LL environments46. These patterns were echoed in other fluorescence traits: tolerant genotypes sustained qP and ETR at the 2L–4L positions, while these parameters dropped sharply in susceptible genotypes beyond the flag leaf47. This coordination is consistent with observations from shade-adapted peanut species, where higher quantum yield and PSII efficiency support resilience to light gradients47. Besides, Fv/Fm and ETR showed strong positive correlations with PPFD and net photosynthetic rate at the lower canopy (Fig. 9a), highlighting the critical physiological linkage between internal light availability and photochemical performance. Together, our results emphasise that maintaining photochemical efficiency throughout the canopy is a central adaptive trait in LL-tolerant rice genotypes, while susceptible genotypes are characterised by limited regulatory plasticity and greater declines in photosynthetic capacity under shade. ETR values were estimated using widely accepted constants for absorptance and PSII:PSI partitioning, offering a consistent basis for robust genotype comparisons under low-light conditions. Additionally, consistent with these correlations, SEM-based scoring (Supplementary Table S8) revealed that Pn exerted the strongest contribution to yield under shade (β ≥ 0.6; score 6), supported by ETR (β = 0.5–0.6; score 5). Upstream traits such as qP, Fv/Fm, and chlorophyll content contributed at medium to low levels (scores 3–4), while PPFD ranked lowest (score 2). This hierarchy reinforces that sustained carbon assimilation at the flag leaf, underpinned by strong electron transport, is the central physiological determinant of yield stability under LL.

Additionally, our data emphasizes the importance of whole-plant photosynthetic adaptation under shade from FL to 4L. Purnendu and Swarnaprabha consistently maintained higher gs and Pn across all canopy layers under shade (Fig. 5). In contrast, susceptible genotypes IR64 and IR8 showed sharp declines in gs and Pn beyond the upper leaves, reflecting limited capacity for whole-canopy photosynthetic adjustment48,49,50. Light response curve analysis further supported these trends, with tolerant genotypes exhibiting lower light compensation points in the lower canopy, enabling continued carbon gain even under reduced irradiance50. Quantitatively, LL-tolerant genotypes experienced only a 17–20% reduction in Pn and lesser yield loss under LL, whereas susceptible genotypes suffered Pn reductions of over 45% and yield losses exceeding ≈ 40%. Further, correlation analysis demonstrated that Pn was strongly and positively linked to PPFD at the lower canopy layers, and both traits showed significant positive correlations with grain yield across all genotypes (Fig. 9b, Supplementary Table 3). These findings highlight that a robust, whole-canopy photosynthetic adaptation from FL to 4L not only improves internal light use but is also critical for minimising yield losses under low-light stress in rice51.

Adaptation to LL stress in plants goes beyond structural and physiological adjustments, relying heavily on flexible transcriptional control of the photosynthetic machinery. Qualitative RT-PCR profiling revealed that tolerant genotypes maintained more stable expression of Calvin cycle genes, including OsRbcL, OsRbcS2–S4, and OsGAPA, under LL, retaining transcript levels within 85–90% of normal-light conditions, whereas susceptible genotypes showed sharper declines. This controlled, rather than suppressive, adjustment of carbon fixation is consistent with reports that partial Calvin cycle downregulation helps balance ATP/NADPH supply without limiting carboxylation potential52,53. Notably, expression of Calvin cycle genes such as OsRbcS3 and OsGAPA showed strong positive correlations with both photosynthetic rate and apparent quantum efficiency across genotypes, supporting the idea that transcript retention is closely linked to sustained carbon assimilation under LL (Fig. 9b). In parallel, light-harvesting and PSII repair-associated genes OsLhcb1, OsPSB27-H1, and OsPSII10 were upregulated in tolerant genotypes under LL relative to susceptible genotypes. These genes are crucial for antenna complex stability, PSII repair, and chlorophyll-binding protein turnover, and their expression paralleled the maintenance of Fv/Fm and ETR seen in physiological measurements. Previous work in rice and Arabidopsis has demonstrated that induction of these genes under sub-saturating light preserves PSII integrity and prevents irreversible photodamage, supporting energy balance54. An additional axis of resilience was evident in the elevated expression of OsTXF, a thioredoxin-related gene involved in redox regulation of Calvin cycle enzymes; its higher expression in Swarnaprabha and Purnendu suggests enhanced redox flexibility and rapid reactivation of RuBisCO and FBPase under fluctuating light, a regulatory mechanism reported in other shade-tolerant crops55,56. This supports the hypothesis that redox-sensitive transcriptional networks are vital for metabolic responsiveness in shaded environments (Fig. 10).

Mechanistic model of shading stress in rice agro-systems. (a) Cloud cover reduces the red:far-red (R:FR) light ratio, triggering canopy shading (CSh) and self-shading (SSh). (b) Shading attenuates red light critical for photosynthesis across leaf layers (FL to 4L), especially under dense planting. (c) This creates vertical light gradients, leading to reduced stomatal conductance (gs), photosynthesis (PN), electron transport rate (ETR), and photochemical quenching (qP). Chlorophyll a/b ratio decreases, Fv/Fm increases, and Rubisco activase expression declines. (d) These changes lower apparent quantum yield (AQE), CO₂ availability, and energy regeneration, reducing PN, carbon gain, biomass, and grain yield.

Carbohydrate dynamics across the canopy play a pivotal role in shaping low-light tolerance among rice genotypes. Our data reveal distinct patterns of carbon management under LL conditions (Fig. 7). LL-tolerant genotypes, Purnendu and Swarnaprabha, exhibited higher total carbon content (TC) content in all canopy leaves compared to the susceptible genotypes IR64 and IR8, indicating a sustained capacity for carbon assimilation even under shade (Fig. 7a). Importantly, TC at every leaf layer showed a strong positive correlation with net photosynthetic rate (Pn), underscoring the link between canopy-wide carbon status and photosynthetic efficiency57. This suggests that the ability to maintain robust carbon reserves throughout the canopy is closely associated with efficient photosynthetic performance and is a key feature distinguishing LL-tolerant rice genotypes from susceptible ones under shading stress. Diurnal analysis of total soluble sugars content (TSS) in the flag leaf revealed that tolerant genotypes consistently accumulated more sugars across the day, particularly at midday and in the afternoon (Fig. 7b). Interestingly, we observed a reciprocal pattern between sugars and starch; when TSS levels peaked, starch content in the flag leaf decreased, and vice versa (Fig. 7c). This behaviour suggests an active mobilisation of starch to soluble sugars when energy demand is high, allowing tolerant genotypes to buffer photosynthetic output and maintain metabolic balance under stress58. In contrast, susceptible genotypes exhibited both reduced sugar accumulation and lower starch reserves by late afternoon, reflecting less efficient carbon storage and mobilisation under shade. Together, these patterns imply that dynamic sugar–starch turnover is a hallmark of LL-tolerant genotypes, supporting stable energy supply and contributing to better yield stability under low-light stress59.

Therefore, this study addresses important research gaps by presenting detailed evidence that low-light tolerance in rice results from a coordinated, multi-layered adaptation, encompassing vertical canopy architecture, physiological and biochemical resilience, and transcriptional plasticity across all leaf layers. While aspects of these mechanisms have been examined previously, our work provides an integrated perspective that connects adaptations across organisational levels. In rice, Burgess et al. (2017)60 demonstrated that genotypes with steeper leaf angles allowed greater light penetration into the lower canopy, thereby enhancing photosynthetic potential and quantum yield. Similarly, Jaikumar et al. (2021)61 reported in sorghum that erect-leaf forms maintained higher photosynthetic efficiency under self-shading than drooping forms, underscoring the central role of canopy architecture in sustaining carbon assimilation under shade. Consistent with these reports, our ANOVA analysis also revealed significant genotype-by-environment interactions, supporting the differential shade responses observed in this study (Supplementary Table 4).

Establishing precise trait thresholds and identifying candidate genes and physiological traits associated with yield stability under LL conditions enhances our understanding of intra-canopy stratification and its significance for shade adaptation. These results carry immediate practical value: the identified traits and markers give breeders clear targets for marker-assisted selection and guide the development of LL-tolerant rice varieties suited to dense planting and light-limited environments. Moreover, this integrated framework sets the stage for future research into crop resilience and adaptation under suboptimal light conditions.

Conclusion

This field study demonstrates that LL tolerance in rice arises from coordinated adjustments in canopy structure, photosynthetic efficiency, chloroplast organisation, carbohydrate dynamics, and gene regulation rather than any single trait. Across two Kharif seasons, shade-tolerant genotypes consistently maintained higher radiation use efficiency, sustained photosynthetic performance, and experienced smaller yield losses compared to susceptible lines. These findings emphasise the importance of considering canopy-wide, multi-scale traits in sustaining rice productivity under shade and provide breeders with practical targets for crop improvement. By identifying structural, physiological, and molecular features that support yield stability in light-limited environments, this work offers a valuable foundation for developing rice varieties better adapted to dense planting systems and climate-affected agroecosystems. At the same time, broader multi-environment and multi-genotype evaluations will be essential to refine these insights, strengthen their general applicability, and accelerate their use in breeding programs.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and simulation of low-light treatment

Field experiments were conducted during the Kharif seasons of 2022 and 2023 at the ICAR-Central Rice Research Institute (CRRI), Cuttack, Odisha, India (20.4625°N, 85.8830°E). Meteorological data for the study periods are provided in Supplementary Table S6. Two low-light-tolerant indica rice (Oryza sativa) varieties (Swarnaprabha and Purnendu) and two sensitive varieties (IR64 and IR8) were selected based on previous screening for yield stability under low light conditions62.

Seeds were sown in June, and 28–30-day-old seedlings were transplanted in July at 20 cm × 15 cm spacing. Fertilizers were applied at 80:40:40 kg ha⁻1 of N:P₂O₅:K₂O. Phosphorus, potassium, and half of the nitrogen were applied basally; the remaining nitrogen was applied at tillering and flowering stages. Standard agronomic and plant protection practices were followed.

Low light (LL) conditions were simulated using a 25 m × 6 m × 2 m cloche structure fitted with a 50% agro-shade net, installed 7 days after transplanting during the tillering stage (Supplementary Figs. S2, S3). Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) above and below the canopy was measured using a LI-1500 radiometer (LI-COR, USA) at 12:00 and 15:00 IST for both LL and normal light (NL) plots. Measurements were recorded at the flag leaf (FL), second (2L), third (3L), and fourth (4L) leaves from ten plants per genotype. PAR was expressed as photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD). Monthly PPFD averages were calculated to generate temporal profiles (Fig. 1b, c). Canopy spectral reflectance was measured using an ASD FieldSpec4 spectroradiometer (ASD Inc., USA) at 0.6 m above the canopy. The effects of shading were categorised as canopy shading (CSh, due to the net) and self-shading (SSh, by upper leaves on leaves of lower layers).

Estimation of radiation use efficiency

Radiation use efficiency (RUE) was estimated at the reproductive stage using methods described by Gautam et al.63. Incident and transmitted PAR were recorded, and intercepted radiation was calculated as the difference. RUE was computed as the total above-ground dry matter ratio to intercepted radiation over the growing period.

Foliar phenotypic traits and yield components

Leaf area from FL to 4L was measured using a portable leaf area meter (LI-3000C, LI-COR, USA). Specific leaf area (SLA) and specific leaf weight (SLW) were determined from ten randomly selected leaves. Leaf inclination angle (LIA) was measured between the lamina and sheath of 2L (α), 3L (β), and 4L (γ) using a protractor at 50% flowering. LIA was calculated as 180° minus the measured angle. Leaf area plasticity under LL was calculated using the formula from Sandhu et al.64:

Ten plants per plot were measured for plant height, panicle number, leaf number, and above-ground dry biomass. Spikelet fertility was calculated using six panicles per plant following Wang and Li65. Filled grains were sun-dried to 14% moisture to determine grain yield and 1000-grain weight.

Photosynthetic pigment analysis

Leaves (FL to 4L) were sampled at 50% flowering. Midribs were removed, and 25 mg of tissue was incubated in 10 mL of 80% chilled acetone at 4 °C in the dark for 48 h. Absorbance at 646.6, 663.6, and 750 nm was recorded using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (Evolution 201, Thermo Scientific). Chlorophyll a and b concentrations were calculated as mg g⁻1 fresh weight using the equations of Porra et al.66. Data from six biological replicates were averaged.

Chloroplast ultrastructure analysis

Ultrastructural changes were examined in FL samples collected at 50% flowering. Samples from three plants per treatment were processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) following Srivastava et al.67. Leaf segments were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, post-fixed in 1% OsO₄, dehydrated in graded ethanol (50–100%), and embedded in Spurr’s resin. Ultrathin Sects. (70 nm) were cut with a Leica RM2245 microtome and stained with 2% uranyl acetate and 1% lead acetate. Sections were observed under a JEOL JEM-1400 Plus TEM (JEOL Ltd., Japan) at 120 kV (× 10,000 magnification). Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, USA) was used to quantify starch granules, grana, thylakoids, and plastoglobuli.

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were measured using a LI-6400 portable photosynthesis system equipped with a fluorescence chamber head (LI-COR, USA). Before measurement, leaves were dark-adapted for 30 min to ensure accurate determination of basal fluorescence. Fluorescence responses were then recorded under an actinic light intensity of 1400 μmol photons m⁻2s⁻1 across four canopy positions, from the flag leaf (FL) to the fourth leaf (4L), to capture vertical variation in photosynthetic performance. Measurements were taken from six independent biological replicates per genotype. The following standard equations were applied for parameter estimation: the maximum quantum yield of PSII was calculated as Fv/Fm = (Fm–F₀)/Fm. The relative electron transport rate (ETR) was estimated using the widely adopted formula: ETR = 0.84 × 0.5 × PAR × ΦPSII68. Here, 0.84 represents an average leaf absorptance, and 0.5 assumes equal partitioning of absorbed quanta between PSII and PSI. While these constants are standard in chlorophyll fluorescence studies, it is acknowledged that absorptance and excitation partitioning may vary with genotype, canopy position, and environment. Thus, the ETR values presented here should be interpreted as relative estimates, suitable for comparing genotypic responses under low-light conditions. Photochemical quenching (qP) was calculated as qP = (F′m–F)/F′m69.

Gas exchange analysis

Gas exchange traits were measured at 50% flowering using a LI-6400XT system under PAR of 1500 μmol photons m⁻2 s⁻1 (NL) and 750 μmol photons m⁻2 s⁻1 (LL), CO₂ concentration of 400 μmol mol⁻1, RH of 76 ± 6%, and temperature of 25 ± 2.2 °C. Light response curves for FL were generated by adjusting irradiance from 10 to 1400 μmol photons m⁻2 s⁻1. Parameters including apparent quantum yield (AQY), light compensation point (LCP), and Amax were calculated using the method of Ye and Yu70.

Total carbon content

Total carbon content (TC) was analyzed in FL to 4L using a PrimacsSNC100 elemental analyzer (Skalar, Netherlands). Dried, powdered leaf samples (100 mg) were combusted at 900–1100 °C in oxygen and helium. CO₂ and N₂ were detected using NDIR and TCD sensors. Data were averaged across six biological replicates per season71.

Diurnal starch and soluble sugar accumulation

FL samples were collected at 06:00, 09:00, 11:00, and 17:30 h. Starch content was estimated using the Total Starch Assay Kit (Megazyme, K-TSTA-100A) following Panda et al.71.Total soluble sugars content (TSS) was measured using the anthrone method 72. Results were averaged across six biological replicates.

Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

Fourteen genes related to photosynthesis were selected for quantitative expression analysis. Flag leaves (50% flowering) and spikelets (10 days after flowering) were collected. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA), and cDNA was synthesized using the Takara 1st-Strand Synthesis Kit (Clontech, Japan). qRT-PCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems system using gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S7), designed in Primer-BLAST (NCBI). Actin was used as an internal control. Cycling conditions included: 95 °C for 3 min; 39 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 10 s. Expression levels were calculated using the 2^–ΔΔCt method62.

Statistical analysis

All data represent the mean of six biological replicates over two growing seasons. A two-sample Student’s t-test (unequal variance) was used for comparison between NL and LL treatments. Three-way ANOVA assessed the interaction between light condition, genotype, and leaf position (Supplementary Table S4). Linear regression models were generated using XLStat v23 to evaluate associations between LL treatments and foliar traits, RUE, pigment content, and grain yield with canopy-level photosynthesis. Phenotypic correlations were calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient73. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was conducted on Z-scaled flag-leaf traits to evaluate their contribution to grain yield under low light. Standardised path coefficients were estimated using Python v3.13.5, and total effects were derived as the sum of direct and indirect paths74.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request after acceptance of the manuscript.

References

Shi, J., An, G., Weber, A. P. & Zhang, D. Prospects for rice in 2050. Plant Cell Environ. 46(4), 1037–1045. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.14565 (2023).

Dhankher, O. P. & Foyer, C. H. Climate resilient crops for improving global food security and safety. Plant Cell Environ. 41(5), 877–884. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.13207 (2018).

Murchie, E. H. et al. Acclimation of rice photosynthesis to irradiance under field conditions. Plant Physiol. 130(4), 1999–2010. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.011098 (2002).

Praba, M. L., Vanangamudi, M. & Thandapani, V. Effect of low light on yield and physiological attributes of rice. Int. Rice Res. Notes 29, 71–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00343-021-0397-2 (2004).

Burgess, A. J., Retkute, R., Herman, T. & Murchie, E. H. Exploring relationships between canopy architecture, light distribution, and photosynthesis in contrasting rice genotypes using 3D canopy reconstruction. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 734. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00734 (2017).

Conocono, E. A., Egdane, J. A. & Setter, T. L. Estimation of canopy photosynthesis in rice by means of daily increases in leaf carbohydrate concentrations. Crop Sci. 38(4), 987–995. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1998.0011183X003800040018x (1998).

Kalaji, H. M., Carpentier, R., Allakhverdiev, S. I. & Bosa, K. Fluorescence parameters as early indicators of light stress in barley. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 112, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2012.03.009 (2012).

Acevedo-Siaca, L. G. et al. Variation in photosynthetic induction between rice accessions and its potential for improving productivity. New Phytol. 227(4), 1097–1108. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16454 (2020).

Mott, K. A. & Woodrow, I. E. Modelling the role of Rubisco activase in limiting non-steady-state photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 51((suppl_1)), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1093/jexbot/51.suppl_1.399 (2000).

Farquhar, G. D. & Sharkey, T. D. Stomatal conductance and photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 33(1), 317–345. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pp.33.060182.001533 (1982).

Laisk, A. et al. Photosystem II cycle and alternative electron flow in leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 47(7), 972–983. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01274.x (2006).

Durand, M. et al. Sunflecks in the upper canopy: Dynamics of light-use efficiency in sun and shade leaves of Fagus sylvatica. New Phytol. 235(4), 1365–1378. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18222 (2022).

Hoshikawa, K. The growing rice plant. An anatomical monograph 199–205 (Nosan Gyoson Bunka, 1989).

Pearcy, R. W. Sunflecks and photosynthesis in plant canopies. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 41(1), 421–453. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pp.41.060190.002225 (1990).

Zhuang, J. & Wang, Q. Within-canopy variation in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters can be well captured by vertical patterns of leaf biophysical and chemical traits. Physiol. Plant. 176(4), e14462. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.14462 (2024).

Li, R. et al. Plant architectural structure and leaf trait responses to environmental change: A meta-analysis. Plants 14(11), 1717. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14111717 (2025).

Pauli, D. et al. Investigation of the influence of leaf thickness on canopy reflectance and physiological traits in upland and pima cotton populations. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1405. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01405 (2017).

Galka, P. et al. Functional analyses of the plant photosystem I–light-harvesting complex II supercomplex reveal that light-harvesting complex II loosely bound to photosystem II is a very efficient antenna for photosystem I in state II. Plant Cell 24(7), 2963–2978. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.112.100339 (2012).

Li, L., Zhu, L., Li, X., Dong, S. & Qin, X. Structural insights and challenges in the supercomplexes formed by photosystem I in phototrophs. Plant Cell Environ. 48(7), 4938–4951. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.15542 (2025).

Wu, X. et al. Low light alters the photosynthesis process in cigar tobacco via modulation of the chlorophyll content, chlorophyll fluorescence, and gene expression. Agriculture 11(8), 755. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11080755 (2021).

Borbély, P. et al. Light intensity- and spectrum-dependent redox regulation of plant metabolism. Antioxidants 11(7), 1311. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11071311 (2022).

Cejudo, F. J., González, M. C. & Pérez-Ruiz, J. M. Redox regulation of chloroplast metabolism. Plant Physiol. 186(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiab074 (2021).

Tooley, E. G., Nippert, J. B., Bachle, S. & Keen, R. M. Intra-canopy leaf trait variation facilitates high leaf area index and compensatory growth in a clonal woody encroaching shrub. Tree Physiol. 42(11), 2186–2202. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpac077 (2022).

Das, B., Mahajan, G. R. & Singh, R. Hyperspectral remote sensing: Use in detecting abiotic stresses in agriculture. Advances in Crop Environment Interaction. 317–335 (2018).

Shao, Q. et al. Effects of shade treatments on photosynthetic characteristics, chloroplast ultrastructure, and physiology of Anoectochilus roxburghii. PLoS ONE 9(2), e85996. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085996 (2014).

Li, X., Zhu, S. D., Liu, Y. X., Xue, S. Y. & Li, W. W. Multivariate statistical analysis of low-light tolerance in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum Mill.) cultivars and their ultrastructural observations. J. Plant Growth Regul. 32(3), 646–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-013-9799-7 (2013).

Guohui, L. et al. Diagnosis of leaf chlorophyll content based on close-range multispectral fluorescence image correction. Comput. Electron. Agric. 231, 110040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.110040 (2025).

Jans, T. B. et al. Coupling modelling and experiments to analyse leaf photosynthesis under far-red light. Plant Cell Environ. 48(5), 3171–3184. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.13171 (2025).

Xiong, R. et al. The mechanism of carbon and nitrogen metabolism under low temperature and low light stress after heading in late indica rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 218, 109316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.109316 (2025).

Mantilla-Perez, M. B. & Salas Fernandez, M. G. Differential manipulation of leaf angle throughout the canopy: Current status and prospects. J. Exp. Bot. 68(21–22), 5699–5717. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erx378 (2017).

Tian, J. et al. Maize smart canopy architecture enhances yield at high densities. Nature 632(8025), 576–584. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07669-6 (2024).

Mantilla-Perez, M. B. et al. Toward “smart canopy” sorghum: Discovery of the genetic control of leaf angle across layers. Plant Physiol. 184(4), 1927–1940. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.20.00632 (2020).

Falster, D. S. & Westoby, M. Leaf size and angle vary widely across species: What consequences for light interception?. New Phytol. 158(3), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00765.x (2003).

Valladares, F. & Niinemets, Ü. Shade tolerance, a key plant feature of complex nature and consequences. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 39(1), 237–257. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173506 (2008).

Givnish, T. J. Adaptation to sun and shade: A whole-plant perspective. Funct. Plant Biol. 15(2), 63–92. https://doi.org/10.1071/PP9880063 (1988).

Poorter, L. & Rozendaal, D. M. Leaf size and leaf display of thirty-eight tropical tree species. Oecologia 158, 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-008-1131-x (2008).

Sims, D. A. & Gamon, J. A. Relationships between leaf pigment content and spectral reflectance across a wide range of species, leaf structures and developmental stages. Remote Sens. Environ. 81(2–3), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(02)00010-X (2002).

Fu, P. et al. Estimating photosynthetic traits from reflectance spectra: A synthesis of spectral indices, numerical inversion, and partial least square regression. Plant Cell Environ. 43(5), 1241–1258. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.13718 (2020).

Kumar, B. M., Kunhamu, T. K., Bhardwaj, A. & Santhoshkumar, A. V. Subcanopy light availability, crop yields, and managerial implications: A systematic review of the shaded cropping systems in the tropics. Agrofor. Syst. 98(8), 2785–2810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-024-00957-0 (2024).

Slattery, R. A. & Ort, D. R. Perspectives on improving light distribution and light use efficiency in crop canopies. Plant Physiol. 185(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/koaa088 (2021).

Tang, Y. et al. Active and low-cost hyperspectral imaging for the spectral analysis of a low-light environment. Sensors 23(3), 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23031437 (2023).

Lichtenthaler, H. K. & Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Measurement and characterization by UV–VIS spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 1, F4.3.1-F4.3.8. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142913.faf0403s01 (2001).

Lichtenthaler, H. K. et al. Photosynthetic activity, chloroplast ultrastructure, and leaf characteristics of high-light and low-light plants and of sun and shade leaves. Photosynth. Res. 2(2), 115–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00028882 (1981).

Gu, J. et al. Photosynthetic properties and potentials for improvement of photosynthesis in pale green leaf rice under high light conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1082. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00392376 (2017).

Wellburn, A. R., Robinson, D. C. & Wellburn, F. A. M. Chloroplast development in low-light-grown barley seedlings. Planta 154(3), 259–265. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1396929 (1982).

Naseer, M. A. et al. Chlorophyll fluorescence, physiology, and yield of winter wheat under different irrigation and shade durations during the grain-filling stage. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1396929. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1396929 (2024).

Zhong, X. M., Shi, Z. S., Li, F. H. & Huang, H. J. Photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence of infertile and fertile stalks of paired near-isogenic lines in maize (Zea mays L.) under shade conditions. Photosynthetica 52(4), 597–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-014-0062 (2014).

Panda, D. et al. Contribution of phytochrome A in the regulation of sink capacity, starch biosynthesis, grain quality, grain yield and related traits in rice. Plant Arch. 20(1), 1179–1194. https://doi.org/10.51470/plantarchives.2020.v20.s1.163 (2020).

Panda, D. Development of genetically engineered plant photoreceptors for generating crop plants with novel agronomic traits. Int. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 5, 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8260-1_6 (2014).

Panda, D. et al. The role of phytochrome-mediated gibberellic acid signaling in the modulation of seed germination under low light stress in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 28(3), 585–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-022-01167-7 (2022).

Ono, K. et al. Canopy-scale relationships between stomatal conductance and photosynthesis in irrigated rice. Glob. Change Biol. 19(7), 2209–2220. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12217 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Proteomic analysis of rice subjected to low light stress and overexpression of OsGAPB increases the stress tolerance. Rice 13(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-020-00384-y (2020).

Kohzuma, K. et al. The role of light–dark regulation of the chloroplast ATP synthase. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1248. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01248 (2017).

Hou, X., Fu, A., Garcia, V. J., Buchanan, B. B. & Luan, S. PSB27: A thylakoid protein enabling Arabidopsis to adapt to changing light intensity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112(5), 1613–1618. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1413693112 (2015).

Wang, F. et al. Genotypic-dependent alternation in D1 protein turnover and PSII repair cycle in psf mutant rice (Oryza sativa L.), as well as its relation to light-induced leaf senescence. Plant Growth Regul. 95(1), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-021-00693-4 (2021).

Lemaire, S. D. Redox regulation of the Calvin-Benson cycle: Something old, something new. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 470. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2013.00470 (2013).

Makino, A., Nakano, H. & Mae, T. Responses of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase, cytochrome f, and sucrose synthesis enzymes in rice leaves to leaf nitrogen and their relationships to photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 105(1), 173–179. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.105.1.173 (1994).

Matsuda, R., Ozawa, N. & Fujiwara, K. Leaf photosynthesis, plant growth, and carbohydrate accumulation of tomato under different photoperiods and diurnal temperature differences. Sci. Hortic. 170, 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2014.03.014 (2014).

Okamura, M., Hirose, T., Hashida, Y., Ohsugi, R. & Aoki, N. Suppression of starch accumulation in “sugar leaves” of rice affects plant productivity under field conditions. Plant Prod. Sci. 20(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/1343943X.2016.1259958 (2017).

Zheng, B. et al. Comparison of architecture among different cultivars of hybrid rice using a spatial light model based on 3D digitising. Funct. Plant Biol. 35(10), 900–910. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP08051 (2008).

Jaikumar, N. S. et al. Can improved canopy light transmission ameliorate loss of photosynthetic efficiency in the shade? An investigation of natural variation in Sorghum bicolor. J. Exp. Bot. 72(13), 4965–4980 (2021).

Sekhar, S. et al. Comparative transcriptome profiling of low light tolerant and sensitive rice varieties induced by low light stress at active tillering stage. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 5753. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erab176 (2019).

Gautam, P. et al. Inter-relationship between intercepted radiation and rice yield influenced by transplanting time, method, and variety. Int. J. Biometeorol. 63, 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42170-5 (2019).

Sandhu, N. et al. Rice root architectural plasticity traits and genetic regions controlling root adaptations to drought. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28699 (2016).

Wang, Y. & Li, J. The plant architecture of rice (Oryza sativa). Plant Mol. Biol. 59, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-005-0679-0 (2005).

Porra, R. J., Thompson, W. A. & Kriedemann, P. E. Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: Verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 975, 384–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-2728(89)80347-0 (1989).

Srivastava, R. K. et al. Cadmium alters mitochondrial membrane potential, inhibits electron transport chain activity and induces callose deposition in rice seedlings. J. Plant Growth Regul. 37, 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-017-9726-2 (2018).

Schreiber, U. & Armond, P. A. Heat-induced changes of chlorophyll fluorescence in isolated chloroplasts and related heat-damage at the pigment level. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 502(1), 138–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-2728(78)90138-X (1978).

Favas, P. J., Pratas, J., Gomes, M. E. P. & Cala, V. Selective chemical extraction of heavy metals in tailings and soils contaminated by mining activity: Environmental implications. J. Geochem. Explor. 111, 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gexplo.2011.04.009 (2011).

Ye, Z. P. & Yu, Q. A coupled model of stomatal conductance and photosynthesis for winter wheat. Photosynthetica 46, 637–640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-008-0110-0 (2008).

Panda, D. et al. Phytochrome A mediated modulation of photosynthesis, development and yield in rice (Oryza sativa L.) in fluctuating light environment. Environ. Exp. Bot. 206, 105183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2023.105183 (2023).

Yemm, E. W. & Willis, A. The estimation of carbohydrates in plant extracts by anthrone. Biochem. J. 57(3), 508–514. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj0570508 (1954).

Fatima, S., Rashid, M., Hameed, A., Fiaz, S. & Rebouh, N. Y. Development of rice mutants with enhanced resilience to drought and brown spot (Bipolaris oryzae) and their physiological and multivariate analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 25(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-025-07024-5 (2025).

Grace, J. B. et al. On the specification of structural equation models for ecological systems. Ecol. Monogr. 80(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1890/09-0464.1 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The financial support received from the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), New Delhi, for conducting the experiment, and the logistical support provided by the Director, ICAR-Central Rice Research Institute (CRRI), Cuttack, Odisha, are gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

No funding support for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization of research and writing (DP); Handling of data, Analysis and interpretation (SM); Anatomical sectioning of leaf using TEM (SB): Designing of the experiments (LB); Execution of field/lab experiments and data collection (SD, BM); Correction of the manuscript (LB), Critical suggestions (AK, DBN, AKC, RP, SKR, SS, SKP, MJB).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Panda, D., Mohanty, S., Das, S. et al. Shade tolerance is associated with foliar adaptations, improved radiation use efficiency, and photosynthetic rate in rice. Sci Rep 15, 40835 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24504-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24504-8