Abstract

Ambient air pollution and systemic inflammation are recognized as risk factors for cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome. However, the joint effect on middle-aged and elderly people in China remains unclear. This research aimed to explore the association between the long-term effects of air pollution/C-reactive protein (CRP) and early CKM syndrome. This cross-sectional cohort involved 9293 participants from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) in 2015 (Wave 3). The concentrations of air pollutants, including fine particulate matter (PM2.5), inhalable particles (PM10), sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone (O3) and carbonic oxide (CO), were obtained from the ChinaHighAirPollutants (CHAP), which contains estimates of the concentrations of these air pollutants in residences at the city level. CKM syndrome was diagnosed according to the American Heart Association (AHA) definition, and stages 1 and 2 were defined as early stages in this study. Generalized linear model (GLM) was employed to assess the relationship between air pollutants and CKM syndrome, while the interactions between CRP and air pollutants were also included to evaluate the modified impacts of CRP on the air pollution-CKM association. GLM results revealed that per-SD increases in the concentrations of PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, O3 and CO were corresponded to elevated CKM prevalence, with ORs (95% CI) of 1.209 (1.085–1.346), 1.263 (1.134–1.406), 1.227 (1.098–1.372), 1.182 (1.060–1.317), 1.135 (1.019–1.265) and 1.160 (1.041–1.292), respectively. Stronger correlations were seen among individuals aged ≤ 65 years, males, urban residents and non-smokers. Moreover, CRP was significantly linked to a greater risk of CKM (OR = 1.207, 95% CI 1.126–1.295). Higher concentrations of air pollutants progressively amplified the risk of CKM syndrome associated with elevated CRP. And the adverse effects of air pollutants were most prominent among individuals with moderate, rather than minimal or severe levels of inflammation. Prolonged exposure to air pollutants has been linked to a greater risk of early CKM syndrome, potentially mediated by inflammatory responses. Particularly, CRP modified the air pollutant–CKM relationship in a complex manner, whereas air pollutants showed a more evident modification of the CRP–CKM association. Considering the ageing population and the health burden posed by CKM, interventions should aim to improve air quality and alleviate systemic inflammatory conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome is defined by the American Heart Association (AHA), as a systemically progressive disease manifesting through multiorgan dysfunction or pathological interactions among metabolic disorders, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD)1. CKM syndrome significantly impacts patient prognosis, resulting in worse clinical outcomes and higher mortality rates than the individual risks of each condition alone2,3. Among the adult population in the USA, approximately one-fourth concurrently suffer from at least one condition, while the prevalence of complications related to CKM is more than 25% worldwide4. Notably, for individuals in the preclinical stages, the focus is usually on preventing the development of CVD events. Thus, the early stages of CKM syndrome should be taken seriously, as the incidence of CKM syndrome is currently increasing.

Air pollution is increasingly considered a significant global health concern with substantial evidence linking it to CKM-related diseases, such as hyperlipidaemia, metabolic syndrome (MetS), CKD, and CVD5,6,7,8,9,10. The possible reasons are that long-term exposure can amplify multifarious risk factors, such as increased blood pressure, insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, and circadian disorders11. However, epidemiologic evidence of the relationship between air pollutants and CKM syndrome has been reported mainly on the basis of fine particulate matter (PM2.5)12,13. To our knowledge, studies on the impact of long-term exposure to other air pollutants on CKM syndrome are especially rare in middle-aged and elderly populations from China.

Systemic inflammation is the connecting bridge between air pollution and various diseases and plays a crucial role in pathophysiological processes14. In particular, C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acute-phase protein with considerable predictive value in multiple diseases. And it could serve as a potential effect modifier, reflecting the ability of ambient particles to cause inflammatory reactions15. Moreover, CRP has been suggested to be an important factor in air pollution-induced health conditions, including respiratory diseases, metabolic-related diseases, and atrial fibrillation16,17,18,19. Although the specific patterns of the association between air pollution/CRP and CKM syndrome remain uncertain, a growing series of evidence has demonstrated that systemic inflammation most likely accelerates the relationship between air pollution and CKM syndrome.

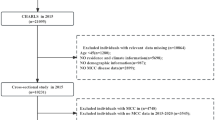

According to the staging framework of CKM syndrome, the AHA considers it highly important to test individuals in the early stages with excess or dysfunctional adiposity, critical metabolic risk factors (such as hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, diabetes and MetS), as well as moderate- to high-risk CKD. The purpose of this cross-sectional study based on the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) in 2015 (Wave 3), is to investigate the associations and interactions of ambient air pollutants/CRP with early CKM syndrome, and highlights that early CKM populations with high-risk factors should avoid further progression to CVD events. The detailed schematic diagram is presented in Fig. 1.

Methods

Population and data resources

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), is a nationally representative cohort study designed to collect comprehensive data on the health and economic status of residents aged at least 45 years. Participants were selected using a multistage stratified sampling approach across various provinces, ensuring diverse representations of the population. Further detailed information about the CHARLS can be accessed on the official website (http://charls.pku.edu.cn/)20. Blood lipid levels, fasting blood glucose, waist circumference, and other physical indices were assessed only during the CHARLS surveys conducted in 2011 (Wave 1) and 2015 (Wave 3), and the evaluation of air pollutants in China predominantly took place after 2013. Hence, this study concentrated on a national cross-sectional analysis using data from 2015 (Wave 3).

A total of 21,095 individuals from 28 provinces in China were initially enrolled in Wave 3. Among the total sample, 11,802 were excluded for a variety of reasons, such as age ≤ 45 years, CKM stage 3 or 4, and lack of necessary information. As detailed in Fig. S1, 9293 subjects were included in this research. Approval for the CHARLS study was obtained from the Peking University Biomedical Ethics Committee (approval number IRB00001052-11015). Furthermore, all participants were required to provide written informed consent, ensuring their understanding and voluntary involvement in the research.

Assessment of air pollution exposure

The annual data for air pollutants of PM2.5, inhalable particles (PM10), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), ozone (O3) and cabon monoxide (CO), were sourced from the ChinaHighAirPollutants (CHAP) database (https://weijing-rs.github.io/product.html), which provides high-grid spatial resolution (0.1°*0.1°) by artificial intelligence. In other words, high-resolution air pollution data were collected by integrating ground measurements with satellite-derived spatiotemporal observations and atmospheric reanalysis, and the Space–time Extra-trees (STET) model was subsequently employed to evaluate the daily concentrations. Detailed information regarding the air pollution estimation can be found in earlier research21,22,23,24,25. The residential air exposure of each participant was based on the city level due to privacy restrictions in CHARLS. To improve reliability, this study utilized a 3-year period of ambient air pollutant concentrations from 2013–2015 to reduce short-term fluctuations and noise, whereas one- (2015) and two-year (2014 and 2015) average concentrations were employed in the following sensitivity analysis26.

Definition, staging and data analysis of CKM syndrome

According to the framework of CKM syndrome as defined by the AHA, four distinct stages are classified on the basis of the presence of risk factors and clinical conditions. Stage 0 represents the absence of CKM-related risk factors. Stage 1 is characterized by excess or dysfunctional adiposity. Stage 2 involves the emergence of metabolic risk factors with hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and moderate- to high-risk CKD. Stage 3 represents individuals with subclinical CVD and CKM risk factors. Stage 4 represents clinical CVD, where individuals exhibit overt cardiovascular conditions alongside CKM risk factors. In particular, CVD was defined as individuals had ever suffered from heart disease or stroke27. In this study, stages 1 and 2 of the CKM syndrome were defined as early stages, representing a critical period of elevated cardiometabolic risk. These stages reflected the transition from excess or dysfunctional adiposity to the emergence of metabolic risk factors, preceding the onset of subclinical CVD28. Moreover, the available data about CKM staging criteria in CHARLS were detailed in Table S1, and specific definitions of various diseases were outlined in Table S2.

Covariates

To address potential confounding factors, several covariates were included to comprehensively assess the associations between air pollution exposure and the prevalence of early CKM syndrome. These covariates in the current study were selected on the basis of previous papers29,30. The covariates included age, sex, residence, education status, marital status, smoking status, drinking status, and cooking fuels used. Furthermore, various chronic diseases were recognized as potential confounding factors through a standardized questionnaire in which participants were asked, "Have you been diagnosed by the doctor with any of the conditions listed?" These listed chronic diseases included arthritis diseases, digestive diseases, lung diseases and liver diseases.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to summarize the data. Categorical data were expressed in terms of counts and percentages, whereas continuous data were presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs). Continuous and categorical data were compared between non-CKM and CKM participants via t tests and chi-square tests, respectively31. The relationships among various air pollutants were assessed by Pearson correlation coefficients.

For the cross-sectional analysis, a generalized linear model (GLM) with a logit link function (logistic regression) was utilized to examine the associations and interactions, and the effect estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were displayed as odds ratios (ORs) for CKM associated with per-SDs increase in air pollutants. Considering the potential confounding factors, three models were gradually adjusted: Model 1 controlled for age and sex, Model 2 was further adjusted for socioeconomic variables (education status, residence, and marital status) and health behaviours (drinking status, smoking status, and cooking fuel use), and Model 3 further included adjustments for chronic diseases (arthritis disease, digestive disease, lung disease, and liver disease). Moreover, McFadden’s pseudo R2 was also employed to evaluate the degree of model fit32. To investigate the impact of CRP on CKM and its moderating role in the relationship between air pollutants and CKM, we employed three analytical models based on fully adjusted parameters. Model 4 initially examined the relationship between the CRP and CKM without any air pollutants. We subsequently incorporated an additive term for the CRP alongside every air pollutant within the identical model (Model 5). Finally, Model 6 implemented the interaction term of CRP with an air pollutant, exploring the potential synergistic relationships between CRP and each air pollutant on CKM syndrome.

In fully adjusted models, restricted cubic splines (RCSs) with four knots were used to explore possible nonlinear associations between CKM risk and prolonged air exposure. Next, subgroup analyses were conducted based on various factors, such as age (≤ 65 years or > 65 years), sex (male or female), residence (rural or urban), and smoking status (nonsmoker or smoker). Additionally, a suite of comprehensive sensitivity analyses were conducted to ensure the credibility and dependability of the results. Firstly, GLMs and their interactive analysis were reconducted through the annual air pollutants in 2015 and the two-year average concentrations for 2014–2015. Secondly, we controlled for regional classifications (“East”, “Midland” and “West”) to address variations in economic development across different geographical areas. Thirdly, participants who had relocated between 2011 and 2015 were excluded from the analysis. Finally, the two-pollutant model was developed to address the potential weak to moderate collinearity between O3 and other air pollutants33.

R software (version 4.4.1) was utilized for all the data analyses. Two-tailed P < 0.05 was set as the statistically significant, while P < 0.10 was considered as statistical significance threshold for the interactions34.

Results

Descriptive analysis

This study involved total 9,293 participants with aging over 45 years, of which 8,448 participants were defined as early CKM patients. These participants were sourced from a diverse set of 437 communities across 123 cities at the county level, situated within 28 provinces of China. Figure 2 and S2 illustrated the geographical distribution of the 9,293 participants. The detailed flowchart of the participant inclusion process was exhibited in Fig. S1, and Table 1 presented the characteristics of the enrolled individuals. Among the study population, the mean age was 61.38 ± 9.28 years, and 58.23% were female. The average levels of CRP, eGFR, TG, HDL, FBG, SBP, DBP, WC and BMI were 2.81 mg/L, 88.77%, 149.68 mg/dL, 51.03 mg/dL, 105.39 mg/dL, 129.77 mmHg, 76.19 mmHg, 86.30 cm and 24.80 kg/m2, respectively. Moreover, significant disparities (P < 0.001) were identified between residence, smoking status, drinking status, lung disease, antidiabetes medicine, antihypertensive medicine and MetS.

The three-year average concentrations of the six air pollutants (PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, O3 and CO) were presented in Table 2. Their average concentrations were 53.67, 93.11, 30.18, 28.25, 84.54 and 1.14 μg/m3, respectively. Pearson correlation analyses revealed strong relationships among air pollutants with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.513 to 0.906 (Table S1). In addition, Fig. S2 showed the relevant concentrations of air pollutants in the cities of residence for this study participants.

Association between air pollutants and the prevalence of CKM syndrome

Figure 3 presented the associations between various air pollutants and the risk of early CKM. Prolonged exposure to these air pollutants was significantly linked to higher ORs of CKM in the three adjusted models. After all confounders were considering in Model 3, each SD increase in PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, O3 and CO was associated with increased ORs of 1.209 (95% CI 1.085–1.346), 1.263 (95% CI 1.134–1.406), 1.227 (95% CI 1.098–1.372), 1.182 (95% CI 1.060–1.317), 1.135 (95% CI 1.019–1.265) and 1.160 (95% CI 1.041–1.292) in early CKM syndrome patients, respectively. Furthermore, Table S3 showed the McFadden R2 values of the relationships of air pollutants with CKM syndrome were 0.163, 0.165, 0.164, 0.162, 0.161 and 0.161, respectively. These results revealed the model fit effects were acceptable. Our findings also indicated that PM10 was the most significant contributor to the increased risk of CKM, followed by SO2, PM2.5, NO2, CO and finally O3.

Associations between each air pollutant and the early CKM, per SD increment in air pollutants. Model 1: adjusted for age and sex; Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, residence, education status, marital status, smoking status, drinking status, and cooking fuel use; Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, residence, education status, marital status, smoking status, drinking status, cooking fuel use, arthritis disease, digestive disease, lung disease, and liver disease.

Exposure dose‒response relationships and subgroup analyses

RCS regression analysis results were depicted in Fig. S3. In addition to SO2 and CO, the relationships between the other air exposure concentrations and CKM exhibited apparent linear patterns across the curves (P for nonlinearity > 0.05). In particular, nonlinear exposure‒response curves for SO2, CO and CKM were shown in Fig. S3C and F. With increasing concentrations of SO2, the OR values consistently increased until they peaked at approximately 35.0 μg/m3. For CO, there was a V-shaped curve with a threshold at approximately 1.1 μg/m3, and the slope was steeper at CO concentrations after that.

Subgroup analyses were shown in Fig. S4. Male participants who were ≤ 65 years old were more susceptible to the negative influences of air pollution (although several P values were not statistically significant). In the residence-specific analyses, stronger air exposure–CKM correlation was observed in urban areas than in rural areas. Similarly, adverse influences were also observed in nonsmoking individuals (P < 0.05). Although the hazardous air pollutants differ across various populations, the larger ORs of pollutants for each increase in SD were PM10 or SO2.

Association between CRP with air pollution and early CKM syndrome

The CRP level was added to the GLMs, and prominent positive associations between CRP and the risk of CKM were identified. Table 3 showed that CRP alone was significantly related to CKM in Model 4, yielding an OR of 1.207 (95% CI 1.126–1.295). When air pollutants were introduced alongside CRP (Table 3 and Fig. S5), the effect evaluation of both the CRP level and air pollutants revealed little change (Model 5). Model 6 illustrated the interaction of CRP with each pollutant, demonstrating that enhanced ORs for each pollutant when CRP levels were considered. In addition to NO2, the synergistic relations of CRP and air pollutants on CKM syndrome were statistically significant (Pinteraction < 0.10). Moreover, we also observed stronger average associations between CRP and early CKM syndrome as pollutant concentrations increased in Fig. S6. While the correlations of ambient air pollution with CKM syndrome peaked around the 40th percentile of CRP, followed by a slight decrease (Fig. S7).

Sensitivity analysis

The replacement of different air pollutant exposure time frames (1 year and 2 years) also led to almost the same findings (Tables S5–S7). The interactions between air pollutants and CRP remained directionally consistent, although the interaction term for NO₂ didn’t reach statistical significance. After adjusting for regional categories, the sensitivity results of the association between air pollutant exposure and the risk of CKM didn’t substantially change (except for NO2, Tables S8 and S9). In addition, the results of sensitivity analyses involving study populations (excluding participants who had relocated between 2011 and 2015, Tables S10, S11), and the two-pollutant model based on O3 continued to support the robustness of the principal outcomes (Table S12). Only CO was no significant association in the two-pollutant model. Collectively, all the results of the sensitivity analyses demonstrated an approximately similar trend: the impact evaluations for air pollutants and CRP on early CKM syndrome increased when their interactions were also involved.

Discussion

According to cross-sectional research based on the CHARLS in 2015, this study first underscored that prolonged exposure to air pollutants was positively related to the increased prevalence of early CKM syndrome. PM10 was identified as the crucial pollutant associated with an increased prevalence of early CKM. Furthermore, study participants who were younger than 65 years, male, urban residents and non-smoking were more vulnerable to the harmful influences of air pollutants. Most notably, systemic inflammation could also promote the deleterious associations of pollutants on early CKM syndrome.

A substantial mass of previous papers have supported a relationship between air pollutants and diseases related to early CKM, such as hypertension, MetS, CKD, diabetes and obesity. As central features of early CKM syndrome, these conditions independently increase mortality risk and further exacerbate the burden when they coexist. For example, a systematic review based on 17 epidemiological studies (comprising of 6 short-term and 11 long-term exposure) investigated long-term exposure to NO2 and PM10, and short-term exposure to SO2 and PM2.5 was strongly positively related to hypertension35. Hou et al. conducted a cross-sectional analysis enrolled 39,089 individuals from Henan, China, and this study reported that 5 μg/m3 increases in PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations were associated with 42.4% and 22.87% greater risks of MetS in China, respectively34. In addition, another chronic disease cohort study from China recruiting 10,253 residents, also achieved the similarly increasing trend of MetS31. Recent evidence has also revealed a relationship between PM2.5 exposure and CKD. Over 2.4 million US veterans followed up for 8.5 years reported that a 10 µg/m3 increase in PM2.5 was linked to increased ORs of developing CKD36. Moreover, an observational cohort study of 29,602 patients in Seoul reported that PM2.5 and CO had a common hazard ratio (HR) of 1.17 among CKD patients37. In addition, several studies have shown that PM2.5, O3 and NO2 are positively associated with obesity, diabetes and dyslipidaemia38,39,40,41.

Systemic inflammation is considered a pathophysiological factor that mediates chronic diseases associated with air pollutant exposure42. To our knowledge, CRP as a potential effect modifier might accelerate disease progression through air pollutants. Initially, studies revealed that exposure to air pollution is linked to elevated systemic inflammatory response. A meta-analysis of 40 observational studies (including panel studies, cross-sectional studies, and cohort studies) revealed significant increases of 0.83% and 0.39% in CRP with a per 10 μg/m3 increase in short-term exposure to PM2.5 and PM10, respectively, whereas long-term exposure increased by 18.01% and 5.61%, respectively14. Simultaneously, a systematic review included 38 studies conducted among 210,438 participants revealed that each 10 μg/m3 increase to O3, NO2 and SO2 was associated with increases in the CRP level of 1.05%, 1.60% and 10.44%, respectively43. Additionally, previous study demonstrated that CRP could also accelerate the adverse effects of air pollution on MetS29. In our study, CRP levels were also measured, which could enhance the interaction between the long-term effects of all pollutants and early CKM syndrome. Though research on CRP and CKM syndrome is insufficient, the relationship between CKM syndrome and other inflammatory indices has been well established. For example, Cao et al. reported that advanced CKM stage individuals with an elevated systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) had a high risk of CVD mortality44. A study from China indicated that per 1000-unit increase in the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) was related with a 1.48-fold increase in the odds of CKM (95% CI 1.20–1.81)45. Collectively, these results were almost identical to our findings, further suggesting that air pollution and systemic inflammation will be strongly related to CKM syndrome.

Although the mechanism through which air pollution associated CKM syndrome remains ambiguous, several potentially pathological pathways associated with air pollution and CKM-related disorders have been proposed. First, exposure to air pollution causes oxidative stress, which may also elevate the circulation of activated inflammatory cytokines, consequently leading to damage to renal tissues, type 2 diabetes, elevated blood pressure and dyslipidaemia26,31,46,47. Our study similarly revealed a significant association with air pollutants/CRP and CKM syndrome, which is consistent with these hypotheses. Second, one explanation is that air pollutants induce the activation of pulmonary cellular responses and cause autonomic nervous system imbalance, resulting in high blood pressure and insulin resistance (IR) and further exacerbating damage to renal function48,49,50. Third, studies suggest that DNA methylation can be induced by exposure to PM2.5, which may cause endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, IR, and apoptosis, leading to glomerular injury and increasing the incidence of CVD51,52. Understanding the combined air pollution-CKM pathway is vital for developing early targeted interventions to halt disease progression and improve long-term patient outcomes.

More interestingly, subgroup analysis revealed the impact of air pollution on early CKM syndrome was more pronounced in males than in females. Individuals younger than 65 years may be more vulnerable to air pollutant exposure. A plausible explanation for this finding is that younger males, as the primary labourers in families, experience greater exposure to air pollution because of prolonged outdoor work in high-pollution conditions53. Moreover, this study revealed that the urban population in China was more vulnerable to the adverse impacts of ambient air pollution than rural counterparts. Urban settings always have high levels of air pollution, which originates from traffic, industrial processes and high-air-pollution areas (such as steel mills, galvanizing plants and fertilizer factories). Finally, nonsmokers were more sensitive to air pollutants because of a lack of other chronic injury factors, and the repeated inhalation of tobacco smoke was observed to stimulate pathological responses similar to those from air pollutants7.

There are some strengths in our study. First, we explored the association of prolonged exposure to air pollutants with early CKM syndrome. Compared with previous studies, this research contributes comprehensive epidemiological evidence on CKM syndrome in middle-aged and elderly people. Second, our study clarifies the complex relationships in which systemic inflammation can aggravate the impacts of air pollution on early CKM syndrome, suggesting that reducing systemic inflammation is an effective preventive strategy against air pollution-induced CKM. Third, the data and resolution of air pollutants estimated by CHAP are more accurate than those estimated by other methods because of satellite sensing and artificial intelligence. Fourth, a series of sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of our findings.

Conversely, several limitations should also be recognized. First, the evidence for the causal relationship between air pollutants/CRP and CKM is limited due to the cross-sectional study, and further longitudinal studies are necessary. Additionally, owing to the lack of specific participant addresses, air exposure was estimated at the city level, which may introduce misclassification bias. Moreover, while we adjusted for various confounders, some unmeasured or unknown factors, such as systemic diseases, traffic noise, or green space, could have influenced the results. Finally, although CRP is a valuable biomarker, it may not comprehensively reflect the complexity of inflammatory reactions. Joint analyses of CRP and additional inflammation markers (such as WBC, IL-6, TNF-α and fibrinogen) could offer a more complete understanding. In future studies, the inclusion of these markers may help clarify the role of inflammation in mediating the health relation of air pollution.

Conclusion

In summary, this study suggested that long-term exposure to ambient air pollutants was positively related to early CKM syndrome, and systemic inflammation could partially modify the harmful effects of air pollution, despite NO₂ showed a non-significant interaction. The interactions suggested that CRP exerted a relatively complex modification on the air pollutant − CKM relationship, whereas air pollutants presented a more direct influence on the CRP − CKM association. Moreover, individuals who are ≤ 65 years old, male, urban residents, or non-smokers might suffer greater adverse effects from air pollutants. These findings indicate that improved ambient air quality and decreased inflammation levels are meaningful for alleviating the burden of early CKM syndrome.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ndumele, C. E. et al. Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 148, 1606–1635. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001184 (2023).

Ndumele, C. E. et al. A Synopsis of the evidence for the science and clinical management of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome: A Scientific statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 148, 1636–1664. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001186 (2023).

Li, N. et al. Association between different stages of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome and the risk of all-cause mortality. Atherosclerosis 397, 118585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2024.118585 (2024).

Ostrominski, J. W. et al. Prevalence and overlap of cardiac, renal, and metabolic conditions in US Adults, 1999–2020. JAMA Cardiol. 8, 1050–1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2023.3241 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Association of long-term exposure to PM2.5 with blood lipids in the Chinese population: Findings from a longitudinal quasi-experiment. Environ. Int. 151, 106454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106454 (2021).

Li, S. et al. Long-term exposure to ambient PM2.5 and its components associated with diabetes: Evidence from a large population-based cohort from China. Diabetes Care 46, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-1585 (2022).

Ye, Z., Li, X., Han, Y., Wu, Y. & Fang, Y. Association of long-term exposure to PM2.5 with hypertension and diabetes among the middle-aged and elderly people in Chinese mainland: A spatial study. BMC Public Health 22, 569. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12984-6 (2022).

Hu, X. et al. The role of lifestyle in the association between long-term ambient air pollution exposure and cardiovascular disease: a national cohort study in China. BMC Med. 22, 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03316-z (2024).

Li, G. et al. Long-term exposure to ambient PM2.5 and increased risk of CKD prevalence in China. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32, 448. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2020040517 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Long-term effects of ambient PM2.5 constituents on metabolic syndrome in Chinese children and adolescents. Environ. Res. 220, 115238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.115238 (2023).

Rajagopalan, S., Al-Kindi, S. G. & Brook, R. D. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 2054–2070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.099 (2018).

Khraishah, H. & Rajagopalan, S. Inhaling poor health: The impact of air pollution on cardiovascular kidney metabolic syndrome. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc. J. 20, 47. https://doi.org/10.14797/mdcvj.1487 (2024).

Lu, F. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the adverse health effects of ambient PM2.5 and PM10 pollution in the Chinese population. Environ. Res. 136, 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2014.06.029 (2015).

Liu, Q. et al. Ambient particulate air pollution and circulating C-reactive protein level: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 222, 756–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2019.05.005 (2019).

Wang, A. et al. Cumulative exposure to high-sensitivity C-reactive protein predicts the risk of cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, 005610. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.005610 (2017).

Tang, L. et al. Effect of urban air pollution on CRP and coagulation: a study on inpatients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm. Med. 21, 296. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01650-z (2021).

Khafaie, M. A. et al. Systemic inflammation (C-reactive protein) in type 2 diabetic patients is associated with ambient air pollution in Pune City, India. Diabetes Care 36, 625–630. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0388 (2013).

Prunicki, M. et al. Immune biomarkers link air pollution exposure to blood pressure in adolescents. Environ. Health 19, 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-020-00662-2 (2020).

Gallo, E. et al. Daily exposure to air pollution particulate matter is associated with atrial fibrillation in high-risk patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 6017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176017 (2020).

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J. & Yang, G. Cohort profile: The China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys203 (2014).

Wei, J. et al. Estimating 1-km-resolution PM25 concentrations across China using the space-time random forest approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 231, 111221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111221 (2019).

Wei, J. et al. The ChinaHighPM10 dataset: generation, validation, and spatiotemporal variations from 2015 to 2019 across China. Environ. Int. 146, 106290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106290 (2021).

Wei, J. et al. Reconstructing 1-km-resolution high-quality PM2.5 data records from 2000 to 2018 in China: spatiotemporal variations and policy implications. Remote Sens. of Environ. 252, 112136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.112136 (2021).

Wei, J. et al. Full-coverage mapping and spatiotemporal variations of ground-level ozone (O3) pollution from 2013 to 2020 across China. Remote Sens. Environ. 270, 112775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2021.112775 (2022).

Wei, J. et al. Ground-level NO2 surveillance from space across china for high resolution using interpretable spatiotemporally weighted artificial intelligence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 9988–9998. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c03834 (2022).

Mao, S. et al. Is long-term PM1 exposure associated with blood lipids and dyslipidemias in a Chinese rural population?. Environ. Int. 138, 105637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105637 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Association of depressive symptoms with incident cardiovascular diseases in middle-aged and older chinese adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e1916591–e1916591. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16591 (2019).

Aggarwal, R., Ostrominski, J. W. & Vaduganathan, M. Prevalence of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stages in US adults, 2011–2020. JAMA 331, 1858–1860. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.6892 (2024).

Han, S. et al. Systemic inflammation accelerates the adverse effects of air pollution on metabolic syndrome: Findings from the China health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Environ. Res. 215, 114340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.114340 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Association between the triglyceride glucose-body mass index and future cardiovascular disease risk in a population with Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic syndrome stage 0–3: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 292. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02352-6 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Associations of long-term exposure to ambient air pollutants with metabolic syndrome: The Wuhan Chronic Disease Cohort Study (WCDCS). Environ. Res. 206, 112549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.112549 (2022).

Park, Y. et al. Spatial autocorrelation may bias the risk estimation: An application of eigenvector spatial filtering on the risk of air pollutant on asthma. Sci. Total Environ. 843, 157053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157053 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. Ambient particulate air pollution and daily mortality in 652 cities. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1817364 (2019).

Hou, J. et al. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollution attenuated the association of physical activity with metabolic syndrome in rural Chinese adults: A cross-sectional study. Environ. Int. 136, 105459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105459 (2020).

Cai, Y. et al. Associations of Short-Term and Long-Term Exposure to Ambient Air Pollutants With Hypertension. Hypertension 68, 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07218 (2016).

Bowe, B., Xie, Y., Yan, Y., Xian, H. & Al-Aly, Z. Diabetes minimally mediated the association between PM2.5 air pollution and kidney outcomes. Sci. Rep. 10, 4586. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61115-x (2020).

Jung, J. et al. Effects of air pollution on mortality of patients with chronic kidney disease: A large observational cohort study. Sci. Total Environ. 786, 147471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147471 (2021).

An, R., Ji, M., Yan, H. & Guan, C. Impact of ambient air pollution on obesity: a systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 42, 1112–1126. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0089-y (2018).

Yang, B.-Y. et al. Ambient air pollution and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 180, 108817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2019.108817 (2020).

Kim, H. J. et al. Combined effects of air pollution and changes in physical activity with cardiovascular disease in patients with Dyslipidemia. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 13, e035933. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.124.035933 (2024).

Smith, L. C. et al. Role of PPARγ in dyslipidemia and altered pulmonary functioning in mice following ozone exposure. Toxicol. Sci. 194, 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfad048 (2023).

Zhang, J., Wei, Y. & Fang, Z. Ozone pollution: A major health hazard worldwide. Front. Immunol. 10, 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02518 (2019).

Xu, Z. et al. Association between gaseous air pollutants and biomarkers of systemic inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 292, 118336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118336 (2022).

Cao, Y., Wang, W., Xie, S., Xu, Y. & Lin, Z. Joint association of the inflammatory marker and cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stages with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality: A national prospective study. BMC Public Health 25, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-21131-2 (2025).

Gao, C. et al. Association between systemic immune-inflammation index and cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome. Sci. Rep. 14, 19151. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69819-0 (2024).

Xu, X., Nie, S., Ding, H. & Hou, F. F. Environmental pollution and kidney diseases. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 14, 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2018.11 (2018).

Niu, Z. et al. Association between long-term exposure to ambient particulate matter and blood pressure, hypertension: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 33, 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2021.2022106 (2023).

Brook, R. D. et al. Insights into the mechanisms and mediators of the effects of air pollution exposure on blood pressure and vascular function in healthy humans. Hypertension 54, 659–667. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130237 (2009).

Rajagopalan, S. & Brook, R. D. Air pollution and Type 2 diabetes: Mechanistic insights. Diabetes 61, 3037–3045. https://doi.org/10.2337/db12-0190 (2012).

Tsai, D.-H. et al. Short-term increase in particulate matter blunts nocturnal blood pressure dipping and daytime urinary sodium excretion. Hypertension 60, 1061–1069. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.195370 (2012).

Wang, C. et al. Personal exposure to fine particulate matter and blood pressure: A role of angiotensin converting enzyme and its DNA methylation. Environ. Int. 94, 661–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.07.001 (2016).

Chen, R. et al. DNA hypomethylation and its mediation in the effects of fine particulate air pollution on cardiovascular biomarkers: A randomized crossover trial. Environ. Int. 94, 614–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.06.026 (2016).

Pan, X. et al. Long-term exposure to ambient PM2.5 constituents is associated with dyslipidemia in Chinese adults. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 263, 115384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115384 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate all the participants in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by Capital Health Research and Development of Special Fund (2024-1-1201).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xuanming Xu and Lian Tang: investigation, writing-original draft, methodology, writing-review and editing. Yutong Kang, Jing Liang and Wenqi Geng: writing-review, editing, investigation, and formal analysis. Yajie Wang: review, supervision, and funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, X., Tang, L., Kang, Y. et al. Association of air pollutions and systemic inflammation with early cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome among middle-aged and elderly adults: a cross-sectional study from CHARLS. Sci Rep 15, 39377 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24690-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24690-5