Abstract

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death mediated by caspases and regulated through both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Many cancers evade apoptosis, resulting in uncontrolled cell survival and tumor progression. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), including XIAP, cIAP1, cIAP2, ML-IAP (also known as Livin), Survivin, NAIP, ILP-2, and BRUCE (also known as Apollon), play crucial roles in suppressing apoptosis and promoting cancer cell survival. Survivin, which is overexpressed in various malignancies, inhibits caspase activity, protects XIAP from proteasomal degradation, and suppresses the intrinsic apoptotic pathway by inhibiting caspase-9 activity. In this study, we investigated the protective role of Survivin on other IAPs, particularly NAIP and cIAP1, using bioinformatics approaches such as homology modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations. Experimental validation in MCF-7 breast cancer cells demonstrated that a novel anticancer peptide, P3, disrupts the interaction between Survivin and IAPs. At 25 µM, P3 significantly enhanced caspase-8 and -9 (initiator) and caspases-3 and -7 (executioner) activities, activating pathways. These effects were confirmed by flow cytometry and DAPI/PI staining, showing increased apoptosis without necrosis. Our findings indicate P3 as a promising peptide-based therapy to overcome apoptosis resistance in breast cancer by targeting Survivin-IAP complexes, providing a foundation for novel anticancer strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Apoptosis is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of programmed cell death, driven by a family of cysteine-dependent aspartate-directed proteases termed caspases1,2,3. Many cancers evade apoptosis, thereby promoting prolonged cell survival. Two mechanistically distinct pathways regulate apoptotic cell death: the extrinsic and intrinsic cascades. The extrinsic pathway is initiated when extracellular death ligands, such as Fas ligand (FasL) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), bind to their respective death receptors in the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily on the plasma membrane1,4,5. Ligand binding leads to the trimerization of receptors, which brings their intracellular death domains close together. This clustering facilitates the recruitment of adaptor proteins, such as Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD), which then attract procaspase-8 molecules to form the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC). Within the DISC, procaspase-8 becomes autocatalytically activated, triggering downstream caspase cascades. This process ultimately cleaves and activates executioner caspases, particularly caspase-3 and caspase-7, leading to a proteolytic cascade that results in apoptosis1,6. The intrinsic pathway of apoptosis is a crucial mechanism of programmed cell death, activated by intracellular stressors such as DNA damage, hypoxia, and the absence of survival signals4. A key feature of the intrinsic pathway is its reliance on mitochondria. Cytochrome c is released from the mitochondria into the cytosol, where it combines with 2′-deoxyadenosine 5′-triphosphate (dATP) and apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (Apaf-1) to form the apoptosome, a multi-protein complex. This complex activates caspase-9, which then cleaves and activates executioner caspases, caspase-3, and caspase-7. This cascade of proteolytic events ultimately leads to apoptosis1. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) family suppress both extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways, thereby promoting cell survival. Emerging therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring apoptosis in cancer cells7,8,9,10,11. The IAP family consists of negative regulators of apoptosis, characterized not by a common function but by the presence of at least one Baculovirus IAP Repeat (BIR) domain in their N-terminal region10,12.In humans, the IAP family comprises eight members: NAIP, cIAP1, cIAP2, XIAP, Survivin, Bruce/Apollon, ML-IAP (also known as Livin), and ILP-211,13,14,15. Cellular Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein 1 (cIAP1), which is encoded by the BIRC2 gene, is located on chromosome 11q22.2. It consists of approximately 618 amino acids, with an estimated molecular weight of about 69.9 kDa. cIAP1 contains three N-terminal baculoviral IAP repeat (BIR) domains, a ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain, a caspase recruitment domain (CARD), and a C-terminal RING finger domain, which provides E3 ubiquitin ligase activity16,17,18. cIAP1, along with TRAF2 and TRAF3, forms an anti-apoptotic protein complex that assembles upon the activation of death receptors, such as TNFR1. Within this complex, cIAP1 is recruited through adaptor proteins like TRAF2 to ubiquitinate receptor-interacting protein kinases (RIPs). This ubiquitination promotes pro-survival signaling through the MAPK cascade and the canonical NF-κB pathway while preventing RIP-mediated apoptosis and necroptosis14,18,19,20,21,22,23. cIAPs continuously ubiquitinate NF-κB–inducing kinase (NIK(, preventing its processing from p100 to p52. This process helps regulate the transition between canonical and non-canonical NF-kB signaling pathways. When cIAP1 and cIAP2 are lost, NIK accumulates, leading to increased production of p52/RelB target genes. These genes include various chemokines and cytokines such as TNF-α and GM-CSF24. Inhibition of cIAP1 increased the formation of the DISC and enhanced the activation of caspase-8, promoting extrinsic apoptosis. Increased expression of cIAP1 has been associated with resistance to apoptosis in various cancers, making it a compelling target for cancer therapy22,23. Neural Apoptosis Inhibitory Protein (NAIP), encoded by the NAIP (BIRC1), is located on chromosome 5q13. The NAIP gene spans 4,212 nucleotides and encodes a 1,403-amino-acid protein with an approximate molecular weight of 159.582 kDa25,26. Structurally, NAIP comprises three N-terminal BIR domains, a central nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD), and multiple C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) motifs27. NAIP plays a critical role in suppressing apoptosis and promoting cancer progression, with its overexpression reported in breast cancer28,29,30. In a clinical study, expression levels of NAIP and Survivin were quantified by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) in 117 primary breast carcinoma specimens and 10 normal breast tissue samples. NAIP transcripts were undetectable in normal breast tissues but were significantly overexpressed in all tumor samples. Furthermore, NAIP expression showed a significant positive correlation with Survivin expression. High NAIP expression was also significantly associated with larger tumor size (T2 or greater) and high nuclear grade (grade III), suggesting its potential utility as a molecular marker for aggressive breast cancer phenotypes. These data suggest that NAIP contributes to breast cancer pathogenesis and aggressiveness28. NAIP inhibits the activities of caspase-9, caspase-3, and caspase-7. It prevents both the autocleavage of pro-caspase-9 and the cleavage of pro-caspase-3 by caspase-9. Specifically, NAIP inhibits caspase-9 autoproteolysis at Asp-315 and reduces the rate of autoproteolysis at Asp-330. NAIP binds to caspase-9 primarily through its BIR3 domain, blocking caspase-9 activation. Functioning primarily within the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, NAIP acts as a key regulator by suppressing caspase activation and thereby inhibiting apoptosis25. Survivin plays a critical role in tumorigenesis due to its high expression levels across a wide range of malignancies31,32,33. Encoded by the BIRC5 gene on chromosome 17q25, Survivin is a 142-amino-acid protein with a molecular weight of approximately 16.5 kDa Wang & Greene34. Survivin functions in the inhibition of apoptosis, regulation of mitosis, promotion of treatment resistance, and maintenance of cancer stem cell viability35,36,37,38,39. Survivin is the smallest member of the IAP family. It is highly expressed in many types of cancer, including colorectal and breast cancer, but is rarely found in normal, mature tissues40,41,42. Survivin contains a single Baculovirus IAP Repeat (BIR) domain at its N-terminal region, followed by a zinc finger-like motif, and concludes with a C-terminal α-helical coiled-coil domain43. It can exist as both a monomer and a dimer. Survivin carries out two main functions by interacting with key proteins like Hsp90, SMAC/DIABLO, XIAP, and components of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC): Inhibiting apoptosis (programmed cell death) and regulating cell division. Both of these roles are crucial in cancer development44,45,46,47. Consequently, Survivin has garnered significant attention in cancer research and is considered clinically important. One of the main functions of Survivin is to inhibit caspase activity. Survivin forms a complex with XIAP as a monomer, which stabilizes XIAP and helps inhibit caspase-9. Specifically, Survivin protects XIAP from being marked for degradation by preventing its ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal breakdown. Survivin also inhibits apoptosis by blocking the activity of Smac/DIABLO, a mitochondrial protein that normally promotes intrinsic apoptosis. Smac/DIABLO works by binding to IAPs and disrupting their interaction with caspases. When Survivin binds to Smac/DIABLO, it prevents this interference, allowing IAPs like XIAP to continue suppressing apoptosis.XIAP is a key apoptosis inhibitor and contains three BIR domains. The BIR3 domain, in particular, binds directly to the N-terminus of caspase-9, preventing it from initiating apoptosis45. Several compounds targeting Survivin have been developed, including YM155, LY2181308, LQZ-7F, shepherdin, SUR-X, and SMAC mimetics (AVPI)22,23,45,46,48,49. These agents exert their anticancer effects primarily through two mechanisms: by inhibiting Survivin expression or by disrupting its interactions with key regulatory proteins, thereby impairing its function. Although these Survivin-targeting compounds have demonstrated potent anticancer activity in both in vitro and in vivo studies, none have yet been successfully translated into clinical application. This highlights the ongoing need for the development of novel therapeutics that can effectively target Survivin in cancer cells13,34,50. Based on our observations and previous studies, disrupting the interaction between Survivin and XIAP has been suggested as a promising therapeutic strategy for breast cancer. To explore this approach, we designed and synthesized a novel anticancer peptide, P3. P3 (sequence: RRR-LREMNWVDYFA) is derived from the Borealin protein, a component of the chromosomal passenger complex, and has the structural formula C85H130N28O21S1. It is specifically designed to target the Survivin–XIAP complex. Bioinformatics analyses and experimental assays revealed that P3, equipped with an N-terminal cell-penetrating sequence, effectively enters cancer cells.P3 competes with Borealin, thereby preventing CPC complex formation and inhibiting cell division. Additionally, by blocking the Survivin–CRM1 interaction, it disrupts nuclear–cytoplasmic transport. Furthermore, interference with the Survivin–XIAP interaction abolishes the protective role of Survivin, leading to proteasomal degradation of XIAP. Consequently, the anti-apoptotic activity of XIAP is diminished, ultimately triggering programmed cell death. Through this dual mechanism, suppressing mitotic progression and inducing apoptosis, P3 demonstrates clear advantages over conventional therapeutic agents and emerges as a promising candidate for cancer treatment.These findings, along with a significant increase in apoptosis, suggest that Survivin may protect other members of the IAP family from degradation51. It is plausible that Survivin, using the same binding domain as for XIAP, also interacts with other IAPs, thereby stabilizing against proteasomal degradation and enhancing their anti-apoptotic activity, similar to the Survivin–XIAP interaction. In this study, we investigated the protective role of Survivin on cIAP1 and NAIP based on the hypothesis that peptide P3 may also interfere with the Survivin–cIAP1 and Survivin–NAIP complexes, thereby activating apoptotic pathways and exerting its antitumor effect.We employed bioinformatics analyses, including homology modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations, to demonstrate that Survivin can bind to cIAP1 and NAIP through its linker region, similar to its interaction with XIAP. We further validated Survivin’s protective role toward these IAPs using multiple experimental approaches. This work highlights a potentially promising therapeutic strategy for breast cancer by inhibiting Survivin’s interactions with IAPs.

Results

Bioinformatics

Structural comparative analysis of the full-length cIAP1

Models predicted by I-TASSER and AlphaFold2, using UCSF ChimeraX, revealed that the I-TASSER model exhibited a more accurate fold for reconstructing the complete structure. Consequently, the I-TASSER predicted model 1 was selected for subsequent bioinformatics analyses (Fig. 1).

Structural comparative analysis of the full-length NAIP

Models generated by MODELLER and AlphaFold2, using UCSF ChimeraX, revealed that the MODELLER-predicted model exhibited a better fold in the gap regions. Consequently, the model with the lower DOPE score was selected for subsequent bioinformatics analyses (Fig. 2).

Docking

Molecular docking analysis demonstrated that both cIAP1 and NAIP proteins interact with the linker region of Survivin. Specifically, the full-length cIAP1 binds through its BIR1 and BIR2 domains, whereas the full-length NAIP binds via its BIR1, BIR3, and NACHT domains. Both proteins exhibit high-affinity interactions, as indicated by the top-ranked docking cluster (Cluster 0) (Fig. 3a–g). The domains and full-length proteins in Cluster 0, along with their approximate energy scores (kcal/mol), are as follows: BIR1: –751.9, BIR2: –848.8, BIR3: –749.2, CARD: –778.4, RING: –780.5, full-length cIAP1: –904.4, and full-length NAIP: –883.3, and the full-length structures of both proteins in complex with Survivin were selected as input for molecular dynamics simulations (Table 1a–g). These results suggest a conserved mode of interaction involving the Survivin linker domain. Notably, previous studies have reported XIAP binding to this region, further underscoring its functional importance51. Collectively, our findings indicate that the linker region of Survivin serves as a critical interface for interactions with IAP family members, thereby contributing to Survivin’s protective role in apoptosis regulation. The binding interactions were further analyzed and visualized using LigPlot + software (Fig. 4a–g).

Molecular docking analysis of Survivin with cIAP1 and NAIP proteins. (a) Docking of the BIR1 domain of cIAP1(green) with Survivin (pink). (b) Docking of the BIR2 domain of cIAP1 (green) with Survivin(pink). (c) Docking of the BIR3 domain of cIAP1(green) with Survivin(pink). (d) Docking of the CARD domain of cIAP1(green) with Survivin(pink). (e) Docking of the RING domain of cIAP1(green) with Survivin(pink). (f) Docking of full-length cIAP1 (green) with Survivin(pink). (g) Docking of full-length NAIP (blue) with Survivin(pink).

Molecular docking analysis of cIAP1 and NAIP with Survivin. Docking results indicate that cIAP1 and NAIP interact with the linker region of Survivin, similar to XIAP. Specifically, cIAP1 engages via its BIR1 and BIR2 domains, whereas NAIP interacts through the BIR1, BIR3, and NACHT domains. (a) Binding interactions of the BIR1 domain of cIAP1 with Survivin. (b) Binding interactions of the BIR2 domain of cIAP1 with Survivin. (c) Binding interactions of the BIR3 domain of cIAP1 with Survivin. (d) Binding interactions of the CARD domain of cIAP1 with Survivin. (e) Binding interactions of the RING domain of cIAP1 with Survivin. (f) Binding interactions of full-length cIAP1 with Survivin. (g) Binding interactions of full-length NAIP with Survivin.

MD analysis

System equilibration

The systems were equilibrated using NVT and NPT ensembles for 100 ps each, at 300 K and 1 bar, before the molecular dynamics simulations. Electrostatic interactions were calculated using the PME method (Fig. 5a–h).

Stabilization of MD simulation parameters. During the final stages, including energy minimization, potential energy, temperature, density, and pressure were adjusted and stabilized, ensuring the systems reached thermodynamic equilibrium. (a) cIAP1–Survivin potential energy; (b) NAIP–Survivin potential energy; (c) cIAP1–Survivin temperature; (d) NAIP–Survivin temperature; (e) cIAP1–Survivin density; (f) NAIP–Survivin density; (g) cIAP1–Survivin pressure; (h) NAIP–Survivin pressure.

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) analysis

RMSD analysis of the system’s backbones was performed relative to their crystal structures before simulations (RMSD Xtal) and revealed that both protein–protein complexes, Survivin–cIAP1 and Survivin–NAIP, exhibit similar fluctuation patterns. The RMSD profiles of these complexes closely resemble those of the individual cIAP1 and NAIP proteins (Fig. 6a–f). This indicates that the systems and their constituent proteins fluctuate in a coordinated manner throughout the simulation, reflecting structural stability. Therefore, the interactions between Survivin and both cIAP1 and NAIP remain stable throughout the molecular dynamics simulations.

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) analysis of Survivin–cIAP1 and Survivin–NAIP systems. RMSD values of the systems and protein backbones were calculated during molecular dynamics (MD) simulations at different time points. The RMSD plots show that both the cIAP1–Survivin and NAIP–Survivin systems exhibit fluctuation patterns similar to those of their crystal structures before simulation, as well as to the individual proteins. This indicates that the cIAP1–Survivin and NAIP-Survivin interactions remain stable throughout the simulations. (a) RMSD Xtal values of the cIAP1–Survivin system. (b) RMSD Xtal values of the NAIP–Survivin system. (c)RMSD values of the cIAP1–Survivin system. (d) RMSD values of the NAIP–Survivin system. (e) RMSD values of the cIAP1 protein. (f) RMSD values of the NAIP protein.

Radius of gyration (Rg)

The Rg analysis throughout the simulation indicates consistent structural compactness of the systems (Fig. 7 a, b). These results demonstrate stable conformational behavior and support the maintenance of proper structural folding upon the binding of Survivin to cIAP1 and NAIP.

Radius of gyration (Rg) analysis of Survivin–cIAP1 and Survivin–NAIP systems. The Rg plots of the systems remained stable throughout the 100 ns simulation. As shown in the plots, the binding of cIAP1 and NAIP to Survivin did not disrupt the folding of either protein, indicating a stable structure with consistent fluctuation ranges. (a) Rg of the cIAP1–Survivin system. (b) Rg of the NAIP–Survivin system.

gmx_MMPBSA analysis

Interaction energy calculations for the simulations were performed using gmx_MMPBSA tools. Input files were generated using both the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) and Generalized Born (GB) models. Subsequently, van der waals, electrostatic, desolvation, and total interaction energies were computed for each system. The interaction affinities of the protein–protein systems are summarized in Table 2. These findings further support the protective role of Survivin in stabilizing both cIAP1 and NAIP proteins upon complex formation.

Bioinformatic analyses indicated that our designed anticancer peptide (P3) binds with higher affinity than cIAP1, NAIP, and XIAP to the same Survivin region that mediates interaction with these IAPs. By competitively occupying this site, P3 can abolish Survivin’s protective effect on these IAPs, leading to their proteasomal degradation51.

Experimental

MTT assay

The MTT assay revealed a marked decrease in MCF-7 cell viability following P3 treatment. Cell viability was reduced to 50% at 40 µM after 24 h and 25 µM after 48 h, indicating a time-dependent enhancement of the biological effect of P3 (n = 3; mean ± SEM; two-tailed Student’s t-test; p < 0.01; Cohen’s d > 10)(Fig. 8; Table 3a, b). Accordingly, the IC50 concentrations (40 µM at 24h and 25 µM at 48 h) were selected for subsequent Caspase- 3 and -7 activity assays to evaluate apoptotic activation at biologically effective doses.

Caspase-3 and -7 activity assay

Caspase-3 and -7 activity was evaluated at two time points, 24 h and 48 h, to assess the apoptotic response induced by P3 At 24h, caspase-3 and -7 activation was minimal and statistically non-significant (p = 0.83; two-tailed Student’s t-test), indicating that apoptotic signaling had not yet been triggered. However, after 48 h, a marked and statistically significant increase in caspase-3 and -7 activity was detected, particularat 25 µM and 45 µM P3 concentrations (p = 4.4 × 10− 6 and p = 1.3 × 10− 4, respectively; ***p < 0.0001; two-tailed Student’s t-tests). Corresponding effect sizes (Cohen’s d > 13) indicate a very strong induction of apoptosis. These data strongly support the hypothesis that Survivin provides a protective role through modulation of cIAP1 and NAIP,and that blocking this pathway with P3 leads to caspase-mediated cell death. Data are shown in (Fig. 9a, b; Table 4a–d), where caspase-3 and -7 enzymatic activity and its statistical analysis are summarized as mean ± SEM from three and four independent replicates, respectively (n = 3 and4).

Caspase-3 and -7 activity assay. (a) Caspase-3 and -7 activity after 24 h treatment with 40 µM P3 and 48 h treatment with 25 µM P3. (b) Caspase-3 and -7 activity at 48 h across 15, 25, 35, and 45 µM P3 treatments. Error bars represent SEM from triplicate and quaternary wells, respectively.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001,****P < 0.00001, and ns, not significant.

Flow cytometry apoptosis analysis

Flow cytometric quantification was performed on MCF‑7 cells treated with P3 at concentrations of 25 µM and 45 µM for 48 h. Statistical analysis was based on three biological replicates, each measured in triplicate (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two‑tailed Student’s t‑tests were applied to compare treatment groups to the control, and effect sizes were estimated using Cohen’s d. At 25 µM, P3 treatment significantly increased both early and late apoptosis relative to control levels (Early: 18.7%, p = 0.0044, d = − 4.73; Late: 64.1%, p = 2.86 × 10− 5, d = − 17.4), corresponding to activation of caspases -3, -7, -8, and -9. Cells at this concentration exhibited minimal necrosis (1.36%, p = 0.0868, n.s.), suggesting efficient apoptotic execution. In contrast, at 45 µM, significant elevation was observed only in late apoptosis, 19.2% (p = 0.001, d = 5.53), and necrosis, 13.1% (p = 0.0043, d = 5.86), while early apoptosis was statistically unchanged (p = 0.462, d = 2.92). These results imply that excessive P3 concentrations compromise apoptotic efficiency, likely via P3 aggregation and proteasomal degradation, leading to membrane instability and necrosis. Overall, apoptosis rates reached 82.78% at 25 µM and 23.23% at 45 µM, indicating that 25 µM is the optimal effective concentration for specific caspase‑mediated apoptosis without unspecific cytotoxicity (Fig. 10a–e; Table 5a, b). Its N/P ratio P3 can cause aggregation and membrane disruption effects at 45 µM.

Apoptosis analysis by flow cytometry. (a) Control cells after 48 h incubation. (b) Cells treated with 25 µM P3 for 48 h. (c) Cells treated with 45 µM P3 for 48 h. At 25 µM P3, a significant increase in apoptosis was observed compared to both the control and 45 µM treatment. Q1: Necrosis; Q2: Late apoptosis; Q3: Early apoptosis; Q4: Live cells. (d) Bar plot showing apoptosis in cells treated with 25 µM P3 compared to the control. (e) Bar plot showing apoptosis in cells treated with 45 µM P3 compared to the control. Error bars represent SEM from triplicate wells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001, and ****P < 0.00001.

Based on the caspase-3 and -7 activity assays, along with the flow cytometry data, both of which demonstrated more substantial apoptotic effects at 25 µM, we chose this concentration for subsequent analyses.

Caspase-8 and -9 activity assay

After 48 h of treatment with 25 µM P3, the activities of Caspase-8 and Caspase-9 showed significant elevation compared with the untreated control.

For Caspase-8, activity increased in P3-treated cells (p = 2.68 × 10−7; **** p < 0.0001; two-tailed Student’s t-test; Cohen’s d = 12.10), indicating a robust activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. Similarly, Caspase-9 activity markedly increased in response to P3 treatmet (p = 7.68 × 10⁻9; *** p < 0.001; two-tailed student’s t-test; Cohen’s d = 20.70), confirming significant activation of the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. The p-values below 0.0001 for both caspases indicate highly significant effects of P3 on apoptotic signaling(Fig. 11a, b; Table 6a–d). These results strongly support our initial hypothesis that Survivin exerts a cytoprotective effect on cIAP1 and NAIP, and that interference by P3 with the Survivin–IAP interaction leads to reduced cIAP1 activity, triggering the extrinsic apoptotic pathway and DISC formation, while decreased NAIP activity promotes activation of the intrinsic apoptotic cascade. Together, the data demonstrate that P3 simultaneously activates both the extrinsic (Caspase-8) and intrinsic (Caspase-9) apoptotic pathways, ultimately leading to the activation of Caspases-3 and -7, which mediate an apoptotic response.

Caspase-8 and -9 activity assay. (a) Caspase-8 and (b) caspase-9 activities were significantly increased after 48 h of treatment with 25 µM P3, suggesting that inhibition of Survivin’s protective function decreases cIAP1 and NAIP activity, thereby promoting activation of both the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways. Error bars represent SEM from pentamerous wells. ***P < 0.0001.

DAPI/PI staining

Fluorescence imaging was used to assess the rate of cell apoptosis52,52,53,53. Treatment with P3 increased the proportion of non-viable cells compared to the control group; p-values were below 0.0001, indicating a significant increase in apoptosis and mitotic catastrophe (Fig. 12a–g). These findings suggest that P3 promotes apoptosis in MCF-7 cells by interfering with the protective role of Survivin on cIAP1 and NAIP and arrests the cell cycle by interfering with CPC formation.

AO/PI staining. (a–c) Control cells: DAPI (a), PI (b), merged (c); (d–f) Cells treated with 25 µM P3: DAPI (d), PI (e), merged (f). Live cells exhibited blue fluorescence, indicating viability, while apoptotic and non-viable cells emitted red fluorescence. Scale bar = 1000 µm. (g) Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from three independent replicates (n = 3). Error bars indicate SEM. Statistical comparison was performed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test, yielding an exact p-value of 0.00011.

Discussion

Inhibiting Survivin’s protective function over cIAP1 and NAIP represents a promising therapeutic strategy, particularly given its tumor-specific expression profile.In oncology, Survivin is overexpressed in cancers and is a key therapeutic target 32,37,38,42,51,54. Various approaches, including inhibitory peptides, vaccines, and RNA interference molecules (siRNAs), are being explored to downregulate Survivin activity in cancer cells45,46,55,”Survivin-Targeted Anticancer Vaccine Undergoes Investigation in Metastatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms,”56. Peptides offer distinct advantages over conventional chemotherapeutics, including enhanced tissue penetration, efficient cellular uptake, and reduced off-target toxicity. D-type peptides, composed of D-amino acid residues, are gaining increasing attention as drug candidates due to their superior stability compared to their L-amino acid counterparts57,58. Their versatility supports a wide range of therapeutic applications, including antitumor, antidiabetic, and antimicrobial effects59,60,61. In this study, we employed advanced bioinformatics and computational tools, LigPlot + , NCC-Finder, YASARA, ChimeraX, ClusPro, GROMACS, and gmx_MMPBSA, to investigate Survivin’s protective interactions with cIAP1 and NAIP.Molecular docking results showed that Survivin establishes interactions with cIAP1 and NAIP similar to XIAP. Moreover, compared to XIAP, Survivin binds more strongly to cIAP1, exhibiting higher binding energy and approximately 40 more binding occurrences. With NAIP, Survivin shows binding energy comparable to XIAP but forms about 22 more binding occurrences51. RMSD, RMSD Xtal, and Rg analyses of molecular dynamics simulations indicated that cIAP1 and NAIP bind stably with Survivin while preserving their native protein folding. Binding free energy calculations using gmx_MMPBSA indicated remarkably strong interactions, with energies of − 51.87 kJ/mol for cIAP1 and − 47.64 kJ/mol for NAIP. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations, interaction energy calculations, and RMSD analyses of protein–protein systems demonstrated that Survivin stabilizes these IAP family members. Confirming strong and favorable interactions at the same region targeted by our designed anti-cancer peptide (P3) to inhibit Survivin. Experimentally, we evaluated the effect of P3 on inhibiting Survivin’s protective function in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. In our previous study, MTT assays indicated IC50 values of 40 μM at 24 h and 25 μM at 48 h, confirming the cytotoxicity of P351. In this study, ELISA assays for caspase-3 and -7 activity showed that the anticancer effects of P3 are both time- and concentration-dependent. At 24 h, there was no significant increase in caspase activity (P ≥ 0.05). However, after 48 h, caspase activity significantly increased at concentrations of 25 and 45 µM, especially at 25 µM, where p-values below 0.0001 indicated higher efficacy. These results confirm that P3’s ability to activate apoptosis strengthens over time, with 25 µM being the optimal concentration. Flow cytometry further showed that 25 µM induced the highest apoptosis rate (82.78%), whereas 45 µM led to reduced apoptosis (23.23%) and increased necrosis. The statistical difference between these concentrations, supported by a statistically significant difference for 25 µM, indicates a concentration-dependent effect; the increased necrosis and reduced apoptosis at 45 µM may result from cytotoxic effects and decreased P3 stability, possibly due to non-specific P3 accumulation in the membrane and osmotic disturbances62. DAPI/PI staining confirmed that cells treated with 25 µM P3 were undergoing apoptosis. To further understand the apoptotic pathway, we measured the activities of caspase-8 and -9. Both showed significant increases after 48 h of treatment with 25 µM P3 (P < 0.0001), indicating strong statistical significance. Overall, comparisons across time points and concentrations show that 25 µM produces maximal caspase activation and apoptosis without necrosis.These findings support our hypothesis that Survivin protects cIAP1 and NAIP, and that P3 inhibits this pathway, triggering both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis. The significant activation of caspase-8 and -9 suggests that P3 induces apoptosis by disrupting Survivin’s protective interactions with NAIP and cIAP1, similar to XIAP.The depletion of these inhibitory proteins promotes the activation of initiator caspases, caspase-8 through the extrinsic apoptotic pathway, and Caspase-9 via the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. This activation subsequently triggers the cleavage and activation of executioner caspases, specifically Caspase-3 and Caspase-7, which drive the hallmark morphological and biochemical features of apoptosis observed in P3-treated cells. The strong correlation between increased Caspase-3 and Caspase-7 activities and the elevated apoptotic cell populations detected by flow cytometry supports the mechanism by which P3 induces apoptosis, primarily through targeted disruption of Survivin–IAP complexes.These experimental results closely aligned with the bioinformatics analysis of Survivin’s protective role. P3 induces apoptosis by reducing IAP activity. Its potential to inhibit tumor progression warrants further in vivo investigation. Compared with existing chemotherapeutics, P3 may offer advantages in specificity, although this requires additional validation. Our integrative strategy, combining computational modeling with experimental validation, enabled the rational targeting of Survivin’s interactions with cIAP1 and NAIP, while also reducing research costs and timelines. Given the inherent instability of peptides, the development of efficient delivery systems, such as nanoliposomes and scaffold-based formulations, could further enhance their stability and bioavailability63,64. Building on the promising computational and cellular results, future investigations should aim to substantiate the proposed mechanism by experimentally confirming the interaction between Survivin-P3 and Survivin–IAP complexes through biophysical and biochemical approaches, such as co-immunoprecipitation, pulldown assays, and surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Additionally, western blot analyses of IAP proteins and cleaved caspases would offer valuable protein-level evidence of pathway activation. Assessing the potential cytotoxicity of P3 in non-malignant cells would further clarify its therapeutic selectivity and safety profile.Additionally, the protective roles of Survivin on other IAP family members warrant further investigation, particularly in evaluating the combined effects of P3 with established Survivin inhibitors (e.g., SURX). Previous studies have shown that the Sur-X peptide induces cell death in colorectal cancer by inhibiting the Survivin–XIAP complex45. However, the P3 peptide represents a broader innovation.In this study, we propose and provide bioinformatic and experimental evidence suggesting that Survivin may protect, in addition to XIAP, other IAP family members such as cIAP1 and NAIP. By disrupting these interactions, P3 simultaneously inactivates multiple survival pathways.P3 exerts its effects through three key mechanisms: cell cycle arrest via inhibition of the CPC complex, interference with nuclear–cytoplasmic transport through Survivin–CRM1, and induction of proteasomal degradation of XIAP, cIAP1, and NAIP51. This multifaceted approach distinguishes P3 from Sur-X, elevating it to a comprehensive modulator of survival pathways and positioning it as a promising therapeutic candidate, particularly for breast cancer. In conclusion, our findings highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting Survivin–IAP interactions in cancer treatment.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatic methods

Structural analysis of survivin

The crystal structure of the Survivin protein (PDB ID: 2QFA; resolution: 1.40 Å) was obtained from the RCSB protein data bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). This structure was used as the representative model, and all subsequent structural analyses were performed based on this entry. Structural visualization and analysis were carried out using YASARA software version 22.5.22 (available at https://www.yasara.org/).

Structural analysis of cIAP1

A complete structure of the cIAP1 protein is not available in the RCSB protein data bank. Therefore, its domains were obtained separately using the following PDB entries: 3M1D (BIR1 domain, resolution: 2.00 Å), 7QGJ (BIR2 domain, resolution: 1.30 Å), 4HY5 (BIR3 domain, resolution: 1.75 Å), 2L9M (CARD domain, 20 conformers out of 256 calculated), and 6HPR (RING domain, resolution: 1.70 Å).To reconstruct the full-length structure of cIAP1, we employed I-TASSER (available at https://zhanggroup.org/I-TASSER/) and AlphaFold265 for domain assembly. The final models were then subjected to comparative structural analysis and validation using YASARA version 22.5.22. and UCSF Chimera version 1.17.3.

Structural analysis of NAIP

The crystal structure of the NAIP protein (PDB ID: 8FVU; resolution: 3.60 Å) was obtained from the RCSB protein data bank. Several regions of the structure, specifically amino acids 351–394, were found to have gaps. These missing segments were modeled using AlphaFold265 and MODELLER (https://salilab.org/modeller/)66. The resulting models were evaluated and compared using YASARA version 22.5.22. and UCSF Chimera version 1.17.3 (available at https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/) to ensure structural integrity and proper folding.

Molecular docking

Docking was conducted using the ClusPro server67,68 to investigate the interactions between cIAP1 and NAIP with Survivin. The docking was performed separately for each domain of cIAP1, which includes BIR1, BIR2, BIR3, RING, and CARD, with Survivin. Additionally, docking was conducted for the reconstructed full-length cIAP1 and Survivin, as well as for the modeled full-length NAIP protein and Survivin. The docking models from clusters ranked 0–3 were evaluated. Key amino acid residues involved in these interactions were identified and analyzed using the LigPlot + software (available at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/software/LIGPLOT/)51,69.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted to assess the binding stability of the full-length NAIP–Survivin and cIAP1–Survivin complexes using GROMACS version 2023 (available at https://manual.gromacs.org/documentation/2023/download.html). The simulations utilized the CHARMM27 force field along with the simple point charge (SPC) water model. Two independent simulations were performed at a temperature of 300 K and a pressure of 1 bar. To neutralize the systems, counterions (Na⁺ and Cl⁻) were added by replacing some water molecules. Initially, the systems underwent energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm to eliminate steric clashes and unfavorable interactions. This was followed by equilibration phases under the canonical (NVT) and isothermal–isobaric (NPT) ensembles, each lasting 100 picoseconds (ps). Production MD simulations were then conducted for a duration of 100 ns (ns). Trajectory analyses were performed to evaluate the stability of the systems, utilizing the root-mean-square deviation and radius of gyration as metrics51,70. Additionally, binding affinities were estimated using the gmx_MMPBSA tool version 1.6.2 (available at https://valdes-tresanco-ms.github.io/gmx_MMPBSA/dev/)71.

Experimental methods

Synthesis of anti-cancer peptide P3

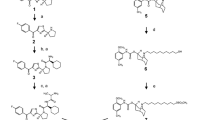

The anticancer peptide P3 was synthesized by Shine-Gene Molecular Biotech, Inc. in Shanghai, China, with a purity of over 98% and a molecular weight of 1912 g/mol(Fig. 13a, b). A 100 µM stock solution was prepared under sterile conditions in a laminar flow hood for use in subsequent in vitro experiments. Aliquots of the solution were stored at − 20 °C.

Cell culture

The human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 was obtained from the University of Tehran (Tehran, Iran). Cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO₂. For transfection experiments, MCF-7 cells at passage 2 and 80–90% confluency were seeded one day prior into 24-well and 6-well plates64.

Measurement of cell viability

MCF-7 cells were prepared in at least three independent biological replicates, each comprising three technical replicates (triplicate wells).MCF-7 cells (2 × 104 cells/mL) were seeded individually into 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h to allow cell attachment. Following adherence, the cells were incubated in serum-free medium for 6 h and then treated with the anticancer peptide P3 at ten different concentrations (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50 µM). The treatment was carried out in serum-free DMEM for 4 h to facilitate transfection. After transfection, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 and 48 h64. The antiproliferative effect of P3 was assessed using the MTT assay at both 24 and 48 h. Briefly, 20 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 4 h. The resulting formazan crystals were solubilized in 100 µL of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate(Sigma-Aldrich, USA) containing 15 mM hydrochloric acid (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader, with appropriate reference wavelengths51. A bar plot with statistical analysis was plotted using R software version 4.5.0 (https://www.r-project.org/).

Measurement of caspase-3 and caspase-7 activity

Caspase-3 and caspase-7 activities were measured using a DEVD-pNA colorimetric assay kit (Kiazist, Iran). This kit detects the release of p-nitroaniline (pNA) upon cleavage by active caspases.MCF-7 cells were independently prepared in at least three biological replicates, each consisting of three and quaternary technical replicates (triplicate and quaternary wells). The cells were seeded into 24-well plates until reaching approximately 70–80% confluency. For each well of a 24-well plate, 2.5 × 105 cells were seeded in 1 mL of culture medium. After 24 h of incubation to allow cell attachment, the cells were treated with P3 using the transfection experiment method51,64. P3 was used at a concentration of 40 µM for 24 h and at concentrations of 15, 25, 35, and 45 µM for 48 h. Untreated cells served as controls. After treatment, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma-Aldrich, USA), trypsinized, and resuspended in 500 µL of lysis buffer. For each sample, 50 µg of protein from the cell lysates was incubated with 5 µL of the DEVD-pNA substrate to detect caspase-3 and -7 activity. The samples were incubated at 37 °C for 3–24 h, and absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader72.

A bar plot with statistical analysis was plotted using R software version 4.5.0.

Apoptosis flow cytometry analysis

The apoptotic rates were determined using Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI) staining, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The Annexin V/PI Apoptosis Kit was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. MCF-7 cells were independently prepared in at least three biological replicates, each consisting of pentamerous technical replicates (pentamerous wells). The cells were seeded into 24-well plates until reaching approximately 70–80% confluency. For each well of a 24-well plate, 2.5 × 105 cells were seeded in 1 mL of culture medium. After 24 h of incubation to allow cell attachment, the cells were treated with P3 using the transfection experiment method64 at concentrations of 25 µM and 45 µM for 48 h; untreated cells served as controls. After treatment, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and resuspended in 1 × binding buffer. A 500 µL aliquot of this suspension was transferred to a 75 × 12 mm plastic test tube. Then, 5 µL of Annexin V–FITC and 10 µL of PI were added. Fluorescence was analyzed using a BD FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA). Calibration was performed with positive and negative control samples to ensure accurate detection of apoptosis. Data analysis was conducted using FlowJo software (version 7.6.1)73. A bar plot with statistical analysis was plotted using R software version 4.5.0.

Measurement of caspase-8 and caspase-9 activity

Since flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis and the assessment of caspase-3 and -7 activity did not clarify the apoptosis pathway, we next analyzed caspase-8 and -9 to further define the pathway and confirm our previous findings. These analyses were performed using the Caspase-8 and Caspase-9 Colorimetric assay kit (Invitrogen, USA).Caspase-8 and caspase-9 activities were measured using IETD-pNA and LEHD-pNA colorimetric substrates, respectively. These assays detect the release of p-nitroaniline (pNA) following cleavage by active caspases.MCF-7 cells were independently prepared in at least pentamerous biological replicates, each consisting of pentamerous technical replicates (pentamerous wells). The cells were seeded into 24-well plates until reaching approximately 70–80% confluency. For each well of a 6-well plate, 5 × 105 cells were seeded in 2 mL of culture medium. After 24 h of incubation to allow cell attachment, the cells were treated with P3 using the transfection experiment method64 at a concentration of 25 µM for 48 h; untreated cells served as controls. After treatment, cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized, and lysed. Fifty micrograms of protein from each lysate were incubated with 5 µL of the appropriate pNA substrate (IETD-pNA for caspase-8 and LEHD-pNA for caspase-9) to assess enzyme activity. Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 1–2 h, and absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader74. A bar plot with statistical analysis was plotted using R software version 4.5.0.

DAPI/PI staining

To further confirm the effect of P3 on apoptosis induction, DAPI/PI double staining was performed75. MCF-7 cells were independently prepared in at least three biological replicates, each consisting of three technical replicates (triplicate wells). The cells were seeded into 6-well plates until reaching approximately 70–80% confluency. For each well of a 6-well plate, 5 × 105 cells were seeded in 1 mL of culture medium. After 24 h of incubation to allow cell attachment, the cells were treated with 25 µM P3 using the transfection experiment method64. After 48 h of incubation, cells were washed with PBS and stained with DAPI (1 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 10 min. Following washes with PBS, cells were incubated with propidium iodide (PI, 5 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 15 min in the dark and washed with PBS. Fluorescence images were acquired using a Cytation imaging system. DAPI binds to the dsDNA of live cells, staining nuclei blue, whereas PI penetrates only cells with compromised plasma membranes, producing red fluorescence and thereby distinguishing dead cells75,76. A bar plot with statistical analysis was plotted using R software version 4.5.0.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dho, S. H., Cho, M., Woo, W., Jeong, S. & Kim, L. K. Caspases as master regulators of programmed cell death: Apoptosis, pyroptosis and beyond. Exp. Mol. Med. 57(6), 1121–1132. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-025-01470-9 (2025).

Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 35(4), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926230701320337 (2007).

Li, X. et al. G protein coupled receptor in apoptosis and apoptotic cell clearance. FASEB Bioadv. 6(9), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1096/fba.2024-00067 (2024).

Nössing, C. & Ryan, K. M. 50 years on and still very much alive: ‘Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics’. Br. J. Cancer 128(3), 426–431. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-02020-0 (2023).

Park, W. et al. Diversity and complexity of cell death: a historical review. Exp. Mol. Med. 55(8), 1573–1594. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-023-01078-x (2023).

Tummers, B. & Green, D. R. Caspase-8: regulating life and death. Immunol Rev 277(1), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12541 (2017).

Fulda, S. & Vucic, D. Targeting IAP proteins for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3627 (2012).

Hsu, P.-C., Tsai, C.-C., Lin, Y.-H. & Kuo, C.-Y. Therapeutic targeting of apoptosis, autophagic cell death, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis pathways in oral squamous cell carcinoma: molecular mechanisms and potential strategies. Biomedicines 13(7), 1745 (2025).

Kumar, S., Fairmichael, C., Longley, D. B. & Turkington, R. C. The Multiple Roles of the IAP Super-family in cancer. Pharmacol. Therap. 214, 107610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107610 (2020).

Silke, J. & Meier, P. Inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins-modulators of cell death and inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a008730 (2013).

Ye, Q., Zhuang, X.-Z., Li, J. & Zhou, X. Targeting the inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) to combat drug resistance in cancers [Review]. Front. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2025.1562167 (2025).

Cetraro, P., Plaza-Diaz, J., MacKenzie, A. & Abadía-Molina, F. A review of the current impact of inhibitors of apoptosis proteins and their repression in cancer. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14071671 (2022).

Cheung, C. H. A., Chang, Y. C., Lin, T. Y., Cheng, S. M. & Leung, E. Anti-apoptotic proteins in the autophagic world: an update on functions of XIAP, Survivin, and BRUCE. J. Biomed. Sci. 27(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-020-0627-5 (2020).

de Almagro, M. C. & Vucic, D. The inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins are critical regulators of signaling pathways and targets for anti-cancer therapy. Exp Oncol 34(3), 200–211 (2012).

Wang, D. et al. BIRC3 is a novel driver of therapeutic resistance in Glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 21710. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21710 (2016).

Gao, B. et al. USP36 inhibits apoptosis by deubiquitinating cIAP1 and survivin in colorectal cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2024.107463 (2024).

Schwalm, M. P. et al. A toolbox for the generation of chemical probes for baculovirus IAP repeat containing proteins. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 886537. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.886537 (2022).

Zadoroznyj, A. & Dubrez, L. Cytoplasmic and nuclear functions of cIAP1. Biomolecules https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12020322 (2022).

Bertrand, M. J. et al. cIAP1/2 are direct E3 ligases conjugating diverse types of ubiquitin chains to receptor interacting proteins kinases 1–4 (RIP1-4). PLoS ONE 6(9), e22356. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022356 (2011).

Chang, Y.-C. & Cheung, C. H. A. An Updated Review of Smac Mimetics, LCL161, Birinapant, and GDC-0152 in Cancer Treatment. Appl. Sci. 11(1), 335 (2021).

Darding, M. & Meier, P. IAPs: Guardians of RIPK1. Cell Death Differ. 19(1), 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2011.163 (2012).

Sun, H. et al. Design of small-molecule peptidic and nonpeptidic Smac mimetics. Acc. Chem. Res. 41(10), 1264–1277. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar8000553 (2008).

Sun, M., Song, L., Li, Y., Zhou, T. & Jope, R. S. Identification of an antiapoptotic protein complex at death receptors. Cell Death Differ. 15(12), 1887–1900. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2008.124 (2008).

Ventre, K. S. et al. cIAP1/2 Antagonism induces antigen-specific T cell-dependent immunity. J Immunol 210(7), 991–1003. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.2200646 (2023).

Davoodi, J., Ghahremani, M. H., Es-Haghi, A., Mohammad-Gholi, A. & Mackenzie, A. Neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein, NAIP, is an inhibitor of procaspase-9. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42(6), 958–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2010.02.008 (2010).

Davoodi, J., Lin, L., Kelly, J., Liston, P. & MacKenzie, A. E. Neuronal apoptosis-inhibitory protein does not interact with Smac and requires ATP to bind caspase-9 *. J. Biol. Chem. 279(39), 40622–40628. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M405963200 (2004).

Abadía-Molina, F. et al. Neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein (NAIP) localizes to the cytokinetic machinery during cell division. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 39981. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39981 (2017).

Choi, J. et al. Neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein is overexpressed in patients with unfavorable prognostic factors in breast cancer. J. Korean Med. Sci. 22(Suppl), S17–S23. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2007.22.S.S17 (2007).

Xu, W.-B. et al. Pan-cancer analysis of the intervertebral-disc-degeneration-related innate immunity gene NAIP. PLoS ONE 18(6), e0286647. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286647 (2023).

Yang, L., Zhao, W., Wei, P., Zuo, W. & Zhu, S. Tumor suppressor p53 induces miR-15a processing to inhibit neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein (NAIP) in the apoptotic response DNA damage in breast cancer cell. Am. J. Transl. Res. 9(2), 683–691 (2017).

Ayoub, A. M. et al. BIRC5 as a master regulator in HCC: Unraveling its role in tumor survival and therapeutic potential. Funct. Integr. Genomics 25(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10142-025-01615-z (2025).

Fang, X. L. et al. Overview of role of survivin in cancer: expression, regulation, functions, and its potential as a therapeutic target. J. Drug Target 32(3), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/1061186x.2024.2309563 (2024).

Kondapuram, S. K., Ramachandran, H. K., Arya, H. & Coumar, M. S. Targeting survivin for cancer therapy: Strategies, small molecule inhibitors and vaccine based therapeutics in development. Life Sci. 335, 122260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2023.122260 (2023).

Wang, Q. & Greene, M. I. Survivin as a therapeutic target for the treatment of human cancer. Cancers 16(9), 1705 (2024).

Garg, H., Suri, P., Gupta, J. C., Talwar, G. P. & Dubey, S. Survivin: a unique target for tumor therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 16, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-016-0326-1 (2016).

Meiners, A. et al. Specific inhibition of the Survivin–CRM1 interaction by peptide-modified molecular tweezers. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 1505. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21753-9 (2021).

Shojaei, F., Yazdani-Nafchi, F., Banitalebi-Dehkordi, M., Chehelgerdi, M. & Khorramian-Ghahfarokhi, M. Trace of survivin in cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 28(4), 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1097/cej.0000000000000453 (2019).

Veiga, G. L. D. et al. The role of Survivin as a biomarker and potential prognostic factor for breast cancer. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 65(6), 893–901. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.65.6.893 (2019).

Zafari, P., Rafiei, A., Esmaeili, S. A., Moonesi, M. & Taghadosi, M. Survivin a pivotal antiapoptotic protein in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Cell Physiol. 234(12), 21575–21587. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.28784 (2019).

Chuwa, A. H. & Mvunta, D. H. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of survivin in gynecological cancer. Oncol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.3389/or.2024.1444008 (2024).

Kim, P. J., Plescia, J., Clevers, H., Fearon, E. R. & Altieri, D. C. Survivin and molecular pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Lancet 362(9379), 205–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13910-4 (2003).

Wang, Q. & Greene, M. I. Survivin as a therapeutic target for the treatment of human cancer. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16091705 (2024).

Albadari, N. & Li, W. Survivin small molecules inhibitors: recent advances and challenges. Molecules 28(3), 1376 (2023).

Carmena, M., Wheelock, M., Funabiki, H. & Earnshaw, W. C. The chromosomal passenger complex (CPC): From easy rider to the godfather of mitosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13(12), 789–803. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3474 (2012).

Fang, W. et al. Sur-X, a novel peptide, kills colorectal cancer cells by targeting survivin-XIAP complex. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 39(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-020-01581-3 (2020).

Nozaki, I. et al. Borealin-derived peptides as survivin-targeting cancer imaging and therapeutic agents. Bioconjug. Chem. 33(11), 2149–2160. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.2c00398 (2022).

Wheatley, S. P., & McNeish, I. A. Survivin: A Protein with dual roles in mitosis and apoptosis. In International Review of Cytology 35–88, Vol. 247. (Academic Press, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7696(05)47002-3

Bai, L., Smith, D. C. & Wang, S. Small-molecule SMAC mimetics as new cancer therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther. 144(1), 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.05.007 (2014).

Werner, T. A. et al. Survivin and XIAP – two potential biological targets in follicular thyroid carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 11383. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11426-3 (2017).

Pavlyukov, M. S. et al. Survivin monomer plays an essential role in apoptosis regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 286(26), 23296–23307. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.237586 (2011).

Ahmadi, S. F., Arab, S. S. & Samadikhah, H. Computational and experimental discovery of peptide inhibitors targeting survivin for therapeutic potential in cancer. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 30599. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13110-3 (2025).

Yin, H. et al. The hybrid oncolytic peptide NTP-385 potently inhibits adherent cancer cells by targeting the nucleus. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 44, 201 (2023).

Yin, H. et al. Design, synthesis and anticancer evaluation of novel oncolytic peptide-chlorambucil conjugates. Bioorg. Chem. 138, 106674 (2023).

Dhani, S., Zhao, Y. & Zhivotovsky, B. A long way to go: caspase inhibitors in clinical use. Cell Death Dis. 12(10), 949. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-04240-3 (2021).

Groner, B. & Weiss, A. Targeting survivin in cancer: novel drug development approaches. BioDrugs 28(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-013-0058-x (2014).

Survivin-Targeted anticancer vaccine undergoes investigation in metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Oncology Live®, 24. https://www.onclive.com/view/survivin-targeted-anticancer-vaccine-undergoes-investigation-in-metastatic-neuroendocrine-neoplasms Vol. 24/No. 4, 2023.

Fu, X.-Y. et al. Three rounds of stability-guided optimization and systematical evaluation of oncolytic peptide LTX-315. J. Med. Chem. 67(5), 3885–3908. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c02232 (2024).

Liu, H., Chow, H. Y., Liu, J., Shi, P. & Li, X. Prior disulfide bond-mediated Ser/Thr ligation. Chem. Sci. 15(35), 14506–14512. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4SC04825C (2024).

Mougel, A. et al. Synergistic effect of combining sunitinib with a peptide-based vaccine in cancer treatment after microenvironment remodeling. Oncoimmunology 11(1), 2110218. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402x.2022.2110218 (2022).

Rossino, G. et al. Peptides as therapeutic agents: challenges and opportunities in the green transition era. Molecules https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28207165 (2023).

Vadevoo, S. M. P. et al. Peptides as multifunctional players in cancer therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 55(6), 1099–1109. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-023-01016-x (2023).

Gary, D. J., Min, J., Kim, Y., Park, K. & Won, Y. Y. The effect of N/P ratio on the in vitro and in vivo interaction properties of PEGylated poly[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate]-based siRNA complexes. Macromol. Biosci. 13(8), 1059–1071. https://doi.org/10.1002/mabi.201300046 (2013).

Pande, S. Liposomes for drug delivery: review of vesicular composition, factors affecting drug release and drug loading in liposomes. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 51(1), 428–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/21691401.2023.2247036 (2023).

Samadikhah, H. R., Majidi, A., Nikkhah, M. & Hosseinkhani, S. Preparation, characterization, and efficient transfection of cationic liposomes and nanomagnetic cationic liposomes. Int. J. Nanomed. 6, 2275–2283. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.S23074 (2011).

Mirdita, M. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 19(6), 679–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-022-01488-1 (2022).

Webb, B. & Sali, A. Protein Structure Modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol. Biol. 1654, 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7231-9_4 (2017).

Alekseenko, A., Ignatov, M., Jones, G., Sabitova, M. & Kozakov, D. Protein-protein and protein-peptide docking with ClusPro server. Methods Mol. Biol. 2165, 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0708-4_9 (2020).

Jones, G. et al. Elucidation of protein function using computational docking and hotspot analysis by ClusPro and FTMap. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 78(Pt 6), 690–697. https://doi.org/10.1107/s2059798322002741 (2022).

Laskowski, R. A. & Swindells, M. B. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 51(10), 2778–2786. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci200227u (2011).

Hollingsworth, S. A. & Dror, R. O. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron 99(6), 1129–1143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.08.011 (2018).

Valdés-Tresanco, M., Valdés-Tresanco, M., Valiente, P. & Moreno Frias, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A new tool to perform end-state free energy calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Computat. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00645 (2021).

Mahdizadeh, N., Khorshid Shabestari, M., Tafvizi, F. & Khodarahmi, P. Delivery of letrozole-encapsulated niosomes via a 3D bioprinting gelatin–alginate scaffold for potential breast cancer treatment. Cancer Nanotechnol. 15(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12645-024-00271-5 (2024).

Qian, J. et al. Development of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies against DKK1 peptide-HLA-A2 complex to treat human cancers. J. Immunother. Cancer https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2023-008145 (2024).

Mühlethaler-Mottet, A. et al. Individual caspase-10 isoforms play distinct and opposing roles in the initiation of death receptor-mediated tumour cell apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2(3), e125–e125. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2011.8 (2011).

Parry, R. A. et al. Exploring the cytotoxic effects of bioactive compounds from Alcea rosea against stem cell driven colon carcinogenesis. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 5892. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89714-6 (2025).

Figueroa, C. M. et al. Induction of cancer cell death by hyaluronic acid-mediated uptake of cytochrome C. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7439.1000316 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran, for this work.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Seyedeh Marzieh Taghavifar and Saba Sabbaghfarshi contributed equally to the design and execution of the experiments, data collection, and manuscript drafting. Dr. Hamidreza Samadikhah conceived the original idea, supervised the research process, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Dr. Saeed Hesami Tackallou contributed to data analysis and interpretation. Seyedeh Fatemeh Ahmadi assisted in literature review and preparation of visual materials. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taghavifar, S.M., Sabbaghfarshi, S., Samadikhah, H. et al. Restoring apoptosis in breast cancer via peptide mediated disruption of survivin IAP interaction. Sci Rep 15, 40947 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24772-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24772-4